Abstract

Background:

Systematic measure reviews can facilitate advances in implementation research and practice by locating reliable, valid, pragmatic measures; identifying promising measures needing refinement and testing; and highlighting measurement gaps. This review identifies and evaluates the psychometric and pragmatic properties of measures of readiness for implementation and its sub-constructs as delineated in the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: leadership engagement, available resources, and access to knowledge and information.

Methods:

The systematic review methodology is described fully elsewhere. The review, which focused on measures used in mental or behavioral health, proceeded in three phases. Phase I, data collection, involved search string generation, title and abstract screening, full text review, construct assignment, and cited citation searches. Phase II, data extraction, involved coding relevant psychometric and pragmatic information. Phase III, data analysis, involved two trained specialists independently rating each measure using Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scales (PAPERS). Frequencies and central tendencies summarized information availability and PAPERS ratings.

Results:

Searches identified 9 measures of readiness for implementation, 24 measures of leadership engagement, 17 measures of available resources, and 6 measures of access to knowledge and information. Information about internal consistency was available for most measures. Information about other psychometric properties was often not available. Ratings for internal consistency were “adequate” or “good.” Ratings for other psychometric properties were less than “adequate.” Information on pragmatic properties was most often available regarding cost, language readability, and brevity. Information was less often available regarding training burden and interpretation burden. Cost and language readability generally exhibited “good” or “excellent” ratings, interpretation burden generally exhibiting “minimal” ratings, and training burden and brevity exhibiting mixed ratings across measures.

Conclusion:

Measures of readiness for implementation and its sub-constructs used in mental health and behavioral health care are unevenly distributed, exhibit unknown or low psychometric quality, and demonstrate mixed pragmatic properties. This review identified a few promising measures, but targeted efforts are needed to systematically develop and test measures that are useful for both research and practice.

Plain language abstract:

Successful implementation of effective mental health or behavioral health treatments in service delivery settings depends in part on the readiness of the service providers and administrators to implement the treatment; the engagement of organizational leaders in the implementation effort; the resources available to support implementation, such as time, money, space, and training; and the accessibility of knowledge and information among service providers about the treatment and how it works. It is important that the methods for measuring these factors are dependable, accurate, and practical; otherwise, we cannot assess their presence or strength with confidence or know whether efforts to increase their presence or strength have worked. This systematic review of published studies sought to identify and evaluate the quality of questionnaires (referred to as measures) that assess readiness for implementation, leadership engagement, available resources, and access to knowledge and information. We identified 56 measures of these factors and rated their quality in terms of how dependable, accurate, and practical they are. Our findings indicate there is much work to be done to improve the quality of available measures; we offer several recommendations for doing so.

Keywords: Readiness, measurement evaluation, psychometric, pragmatic, reliability, validity

Introduction

Like many new scientific fields, implementation science faces a host of measurement issues, including reliance on single-use, adapted measures with unknown reliability and validity; skewed distribution of measures across theoretically important constructs; and inattention to practical measurement considerations (Martinez et al., 2014). Systematic measure reviews help new fields like implementation science address instrumentation issues by locating reliable, valid, pragmatic measures; identifying promising measures needing further refinement and evaluation, and highlighting measurement gaps for key constructs (Lewis et al., 2018).

Two systematic measure reviews (Gagnon et al., 2014; Weiner et al., 2008) have focused on organizational readiness for change, a construct in the inner setting domain of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Damschroder et al., 2009). Readiness for implementation, defined as “tangible and immediate indicators of organizational commitment to its decision to implement an intervention,” is considered a critical precursor to successful implementation (Damschroder et al., 2009; Gleeson, 2017; Kotter, 1996; Weiner, 2009). Although both reviews identified measures with some evidence of reliability and validity, their utility for guiding measure selection is limited in three respects. First, both only considered evidence available in the source article reporting the development or first use of a measure, neglecting evidence available about that measure’s psychometric properties in subsequent uses. Since a measure’s reliability and validity is to some extent sample-dependent, assessing all available evidence provides a fuller picture of the measure’s psychometric properties. Second, both employed a checklist appraisal approach that indicated simply whether or not evidence was available for specific psychometric properties. Although it is helpful to know evidence exists about the reliability and validity of a measure, it is more helpful to know the extent to which the measure is reliable or valid. Finally, neither review appraised the pragmatic quality of measures, that is, the extent to which they are relevant to practice or policy stakeholders and feasible to use in real-world settings (Glasgow, 2013; Glasgow & Riley, 2013; Stanick et al., 2019).

The aim of this review is to assess the reliability, validity, and practicality of measures of readiness for implementation and its CFIR-delineated sub-constructs: leadership engagement, available resources, and knowledge and information. The present review contributes to the literature by rating both the psychometric and pragmatic quality of measures using measure-focused evidence rating criteria (Lewis et al., 2018) and information from all published uses of a measure in mental health or behavioral health, not just the original or first use. Moreover, it facilitates head-to-head comparisons of measures of readiness for implementation and its sub-constructs, enabling researchers and practitioners to readily select measures with the most desirable profile of psychometric and pragmatic features.

Methods

Design overview

The general study protocol for this review is published elsewhere (Lewis et al., 2018). The review had three phases: data collection (Phase I), data extraction (Phase II), and data analysis (Phase III).

Phase I: data collection

Literature searches were conducted in PubMed and Embase bibliographic databases using search strings curated in consultation from PubMed support specialists and a library scientist. Consistent with our funding source and aim to identify and assess implementation-related measures in mental health and behavioral health, our search was built on four core levels: terms for implementation, terms for measurement, terms for evidence-based practice, and terms for behavioral health (Lewis et al., 2018). For the current study, we included a fifth level for each of the following CFIR constructs (Damschroder et al., 2009): (1) Readiness for Implementation, (2) Leadership Engagement, (3) Available Resources, and (4) Access to Knowledge and Information (Table 1). Searches were completed from April to May 2017; searches were updated through June 2019 to identify additional articles citing the original measure development studies. Two authors (C.D. and K.M.) independently screened titles, abstracts, and full-texts of articles using pre-specified criteria. Only empirical studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals containing one or more quantitative measures of these four constructs and used the measure in an evaluation of an implementation effort in a behavioral health context were included. Disagreement in screening decisions were resolved through discussion, with adjudication by a third author (B.W.) as needed.

Table 1.

Database search terms.

| Search term | Search string |

|---|---|

| PubMed | |

| Implementation | (Adopt[tiab] OR adopts[tiab] OR adopted[tiab] OR

adoption[tiab] NOT “adoption”[MeSH Terms] OR Implement[tiab]

OR implements[tiab] OR implementation[tiab] OR

implementation[ot] OR “health plan implementation”[MeSH

Terms] OR “quality improvement*”[tiab] OR “quality

improvement”[tiab] OR “quality improvement”[MeSH Terms] OR

diffused[tiab] OR diffusion[tiab] OR “diffusion of

innovation”[MeSH Terms] OR “health information

exchange”[MeSH Terms] OR “knowledge translation*”[tw] OR

“knowledge exchange*”[tw]) AND |

| Evidence-based practice | (“empirically supported treatment”[All Fields] OR “evidence

based practice*”[All Fields] OR “evidence based

treatment”[All Fields] OR “evidence-based practice”[MeSH

Terms] OR “evidence-based medicine”[MeSH Terms] OR

innovation[tw] OR guideline[pt] OR (guideline[tiab] OR

guideline’[tiab] OR guideline”[tiab] OR

guideline’pregnancy[tiab] OR guideline’s[tiab] OR

guideline1[tiab] OR guideline2015[tiab] OR

guidelinebased[tiab] OR guidelined[tiab] OR

guidelinedevelopment[tiab] OR guidelinei[tiab] OR

guidelineitem[tiab] OR guidelineon[tiab] OR guideliner[tiab]

OR guideliner’[tiab] OR guidelinerecommended[tiab] OR

guidelinerelated[tiab] OR guidelinertrade[tiab] OR

guidelines[tiab] OR guidelines’[tiab] OR

guidelines’quality[tiab] OR guidelines’s[tiab] OR

guidelines1[tiab] OR guidelines19[tiab] OR guidelines2[tiab]

OR guidelines20[tiab] OR guidelinesfemale[tiab] OR

guidelinesfor[tiab] OR guidelinesin[tiab] OR

guidelinesmay[tiab] OR guidelineson[tiab] OR

guideliness[tiab] OR guidelinesthat[tiab] OR

guidelinestrade[tiab] OR guidelineswiki[tiab]) OR

“guidelines as topic”[MeSH Terms] OR “best

practice*”[tw]) AND |

| Measure | (instrument[tw] OR (survey[tw] OR survey’[tw] OR survey’s[tw] OR survey100[tw] OR survey12[tw] OR survey1988[tw] OR survey226[tw] OR survey36[tw] OR surveyability[tw] OR surveyable[tw] OR surveyance[tw] OR surveyans[tw] OR surveyansin[tw] OR surveybetween[tw] OR surveyd[tw] OR surveydagger[tw] OR surveydata[tw] OR surveydelhi[tw] OR surveyed[tw] OR surveyedandtestedthe[tw] OR surveyedpopulation[tw] OR surveyees[tw] OR surveyelicited[tw] OR surveyer[tw] OR surveyes[tw] OR surveyeyed[tw] OR surveyform[tw] OR surveyfreq[tw] OR surveygizmo[tw] OR surveyin[tw] OR surveying[tw] OR surveying’[tw] OR surveyings[tw] OR surveylogistic[tw] OR surveymaster[tw] OR surveymeans[tw] OR surveymeter[tw] OR surveymonkey[tw] OR surveymonkey’s[tw] OR surveymonkeytrade[tw] OR surveyng[tw] OR surveyor[tw] OR surveyor’[tw] OR surveyor’s[tw] OR surveyors[tw] OR surveyors’[tw] OR surveyortrade[tw] OR surveypatients[tw] OR surveyphreg[tw] OR surveyplus[tw] OR surveyprocess[tw] OR surveyreg[tw] OR surveys[tw] OR surveys’[tw] OR surveys’food[tw] OR surveys’usefulness[tw] OR surveysclub[tw] OR surveyselect[tw] OR surveyset[tw] OR surveyset’[tw] OR surveyspot[tw] OR surveystrade[tw] OR surveysuite[tw] OR surveytaken[tw] OR surveythese[tw] OR surveytm[tw] OR surveytracker[tw] OR surveytrade[tw] OR surveyvas[tw] OR surveywas[tw] OR surveywiz[tw] OR surveyxact[tw]) OR (questionnaire[tw] OR questionnaire’[tw] OR questionnaire’07[tw] OR questionnaire’midwife[tw] OR questionnaire’s[tw] OR questionnaire1[tw] OR questionnaire11[tw] OR questionnaire12[tw] OR questionnaire2[tw] OR questionnaire25[tw] OR questionnaire3[tw] OR questionnaire30[tw] OR questionnaireand[tw] OR questionnairebased[tw] OR questionnairebefore[tw] OR questionnaireconsisted[tw] OR questionnairecopyright[tw] OR questionnaired[tw] OR questionnairedeveloped[tw] OR questionnaireepq[tw] OR questionnaireforpediatric[tw] OR questionnairegtr[tw] OR questionnairehas[tw] OR questionnaireitaq[tw] OR questionnairel02[tw] OR questionnairemcesqscale[tw] OR questionnairenurse[tw] OR questionnaireon[tw] OR questionnaireonline[tw] OR questionnairepf[tw] OR questionnairephq[tw] OR questionnairers[tw] OR questionnaires[tw] OR questionnaires’[tw] OR questionnaires”[tw] OR questionnairescan[tw] OR questionnairesdq11adolescent[tw] OR questionnairess[tw] OR questionnairetrade[tw] OR questionnaireure[tw] OR questionnairev[tw] OR questionnairewere[tw] OR questionnairex[tw] OR questionnairey[tw]) OR instruments[tw] OR “surveys and questionnaires”[MeSH Terms] OR “surveys and questionnaires”[MeSH Terms] OR measure[tiab] OR (measurement[tiab] OR measurement’[tiab] OR measurement’s[tiab] OR measurement1[tiab] OR measuremental[tiab] OR measurementd[tiab] OR measuremented[tiab] OR measurementexhaled[tiab] OR measurementf[tiab] OR measurementin[tiab] OR measuremention[tiab] OR measurementis[tiab] OR measurementkomputation[tiab] OR measurementl[tiab] OR measurementmanometry[tiab] |

| OR measurementmethods[tiab] OR measurementof[tiab] OR

measurementon[tiab] OR measurementpro[tiab] OR

measurementresults[tiab] OR measurements[tiab] OR

measurements’[tiab] OR measurements’s[tiab] OR

measurements0[tiab] OR measurements5[tiab] OR

measurementsa[tiab] OR measurementsare[tiab] OR

measurementscanbe[tiab] OR measurementscheme[tiab] OR

measurementsfor[tiab] OR measurementsgave[tiab] OR

measurementsin[tiab] OR measurementsindicate[tiab] OR

measurementsmoking[tiab] OR measurementsof[tiab] OR

measurementson[tiab] OR measurementsreveal[tiab] OR

measurementss[tiab] OR measurementswere[tiab] OR

measurementtime[tiab] OR measurementts[tiab] OR

measurementusing[tiab] OR measurementws[tiab]) OR

measures[tiab] OR inventory[tiab]) AND |

|

| Mental health | (“mental health”[tw] OR “behavioral health”[tw] OR

“behavioural health”[tw] OR “mental disorders”[MeSH Terms]

OR “psychiatry”[MeSH Terms] OR psychiatry[tw] OR

psychiatric[tw] OR “behavioral medicine”[MeSH Terms] OR

“mental health services”[MeSH Terms] OR (psychiatrist[tw] OR

psychiatrist’[tw] OR psychiatrist’s[tw] OR

psychiatristes[tw] OR psychiatristis[tw] OR

psychiatrists[tw] OR psychiatrists’[tw] OR

psychiatrists’awareness[tw] OR psychiatrists’opinion[tw] OR

psychiatrists’quality[tw] OR psychiatristsand[tw] OR

psychiatristsare[tw]) OR “hospitals, psychiatric”[MeSH

Terms] OR “psychiatric nursing”[MeSH Terms]) AND

“English”[Language] AND 1985[PDAT] :

3000[PDAT] AND |

| Readiness | (Readiness[TIAB] AND (Commitment[TIAB] OR Preparedness[TIAB]

OR Acceptance[TIAB] OR Willingness[TIAB]) AND (Change[TI] OR

Changing[TI] OR Organizational Innovation[MH:NOEXP] OR

Organizational Innovation*[TIAB] OR Organisational

Innovation*[TIAB] OR Organizational change*[TIAB] OR

Organisational change*[TIAB] OR Institutional change*[TIAB]

OR Institutional innovation*[TIAB]) OR “Stages of change”

[TIAB]) AND “Organization and Administration:” [SH:NOEXP] OR

Organizational Innovation[MH:NOEXP] OR Organisation*[TIAB]

OR Organization*[TIAB] OR

Institutional*[TIAB] OR |

| Leadership | “leadership engagement” OR “commitment of leader” OR

“involvement of leader” OR “accountability of leader” OR

supervisor[tw] OR leadership[tw] OR leader[tw] OR

“managerial patience” OR |

| Resources | “available resources” OR “resources dedicated to implement*”

OR “dedicated resources” OR |

| Access to knowledge | “access to knowledge” OR “access to infor*” OR “ease of access to resources” OR “basic knowledge” |

| Embase | |

| Readiness | (readiness:ab,ti AND (commitment:ab,ti OR preparedness:ab,ti

OR acceptance:ab,ti OR willingness:ab,ti) AND (change:ti OR

changing:ti OR “organizational innovation*”:ab,ti OR

“organisational innovation*”:ab,ti OR “organizational

change*”:ab,ti OR “organisational change*”:ab,ti OR

“institutional change*”:ab,ti OR “institutional

innovation*”:ab,ti)) OR “stages of change”:ab,ti AND

“organization and management”/de OR organisation*:ab,ti OR

qrganization*:ab,ti OR institutional*:ab,ti OR |

| Leadership | “leadership engagement” OR “commitment of leader” OR

“involvement of leader” OR “accountability of leader” OR

supervisor OR leadership OR leader OR “managerial

patience” OR |

| Resources | “available resources” OR “resources dedicated to implement*”

OR “dedicated resources” OR capacity OR

capability OR |

| Access to knowledge | “access to knowledge” OR “access to inform*” OR “ease of access to resources” OR “basic knowledge” |

Screened studies progressed to the fourth step: construct assignment. Measures often have scales or items that map to multiple CFIR constructs; therefore, a two-pronged approach was employed (Lewis et al., 2018). First, two authors (C.D. and K.M.) assigned measures to constructs based on the measure authors’ indications of the construct, or constructs, that the measure purportedly measures. However, descriptions (or labels) that authors provide for their measures often fail to capture the range of item content reflected in those measures. For example, an author could describe a measure as an assessment of readiness for implementation, yet the measures’ item content might also reflect CFIR constructs such as implementation climate or CFIR sub-constructs like available resources, or leadership engagement. To account for these additional content areas, an item-analysis approach was employed (Chaudoir et al., 2013). Two authors (C.D. and K.M.) reviewed each measure’s items and assigned the measure’s scales or items to a CFIR construct or sub-construct only if two or more items in the measure reflect that construct or sub-construct. These authors discussed discrepancies in construct assignments and engaged the principal investigator (C.C.L.) in those cases when they could not reach agreement.

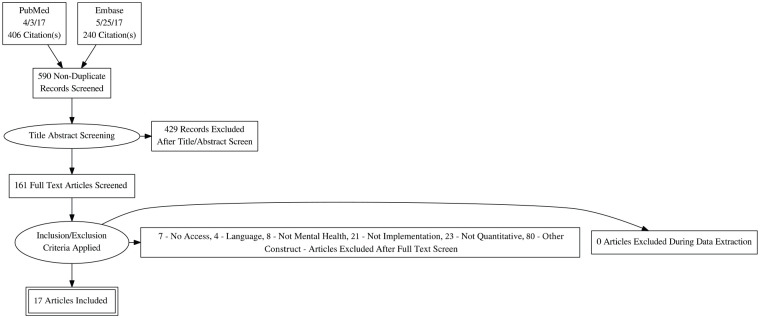

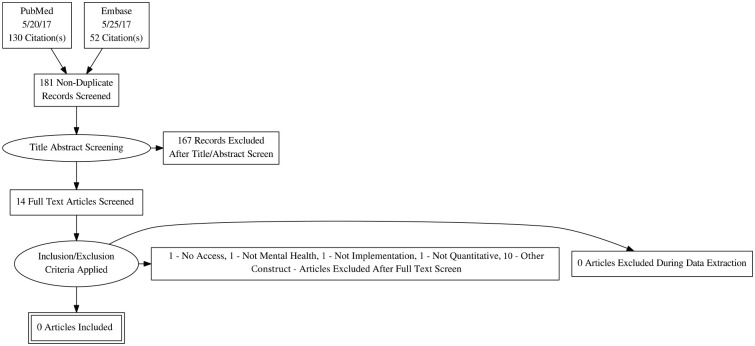

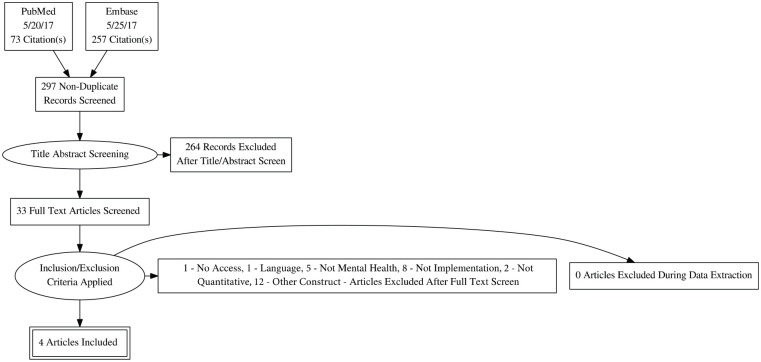

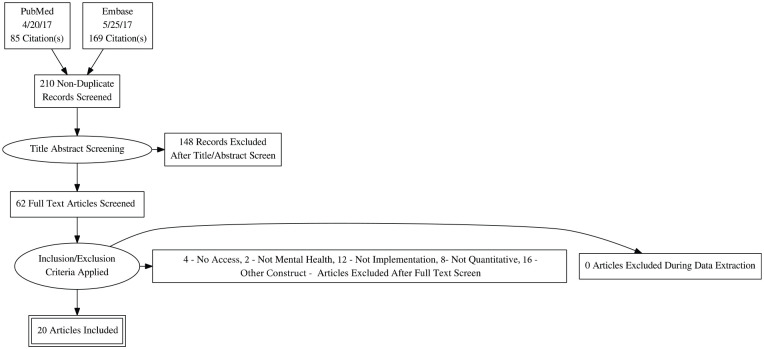

In the fifth and final step, articles citing the original measure development studies in PubMed and Embase were hand-searched to identify all empirical articles that used each measure in implementation research in mental or behavioral health care. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagrams for each construct can be found in Appendix 1 (Moher et al., 2009).

Phase II: data extraction

Once all relevant literature was retrieved, articles were compiled into “measure packets,” which included the measure itself (if available), the measure development article (or article with the first empirical use in mental or behavioral health care), and all additional empirical uses of the measure in mental or behavioral health care. Three authors (C.D., K.M., and E.A.N.) reviewed each article and extracted information relevant to 14 psychometric and pragmatic rating criteria referred to hereafter as the Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scales (PAPERS). The full rating system and criteria for PAPERS is published elsewhere (Lewis et al., 2018; Stanick et al., 2018, 2019). Data were extracted for full measures and their constituent scales.

Anticipating the peer-reviewed literature would contain little information about the pragmatic properties of measures, we conducted a supplemental Google search. To mitigate the influence of algorithmically personalized search results, at least two authors (E.A.N., H.H., or K.M.) completed a Google search using the following steps: (1) the author entered the measure name in quotations in the search field of Google.com (if no formal measure name was provided, then the Google search could not be completed); (2) the search was timed to last no longer than 2 min to reflect the amount of time an average person would spend looking for basic information online (Baker, 2017; Singer et al., 2012)—we tested different lengths of time searching and observed diminishing returns; and (3) only the first page of results was scanned for promising results to reflect the average person’s willingness to search online search engines for information (Diakopoulos, 2015; Hassan Awadallah et al., 2014). If a website relating to the measure was located, it was mined for novel pragmatic data.

PAPERS includes nine criteria for assessing psychometric properties: internal consistency, convergent validity, discriminant validity, known-groups validity, predictive validity, concurrent validity, structural validity, responsiveness, and norms. In addition, PAPERS includes five criteria for assessing pragmatic properties of measures: cost, language accessibility, assessor burden (training), assessor burden (interpretation), and length (Stanick et al., 2019).

Each PAPERS property was rated by two authors independently (C.D., E.A.N., or K.M.) by applying the following scale to extracted data: “poor” (–1), “none” (0), “minimal/emerging” (1), “adequate” (2), “good” (3), or “excellent” (4) (Stanick et al., 2019). Final ratings were determined from either a single score or “rolled up” median approach. If a measure was unidimensional or the measure packet contained only one rating for a PAPERS property (e.g., internal consistency), then this value was used as the final rating for that property. If a measure had multiple scales, the ratings for those scales for a given PAPERS property were “rolled up” by computing and assigning the median rating for that PAPERS property to the measure as its final rating. If a measure had five scales, each scale was rated for internal consistency and the median of those ratings was assigned to the whole measure as its final rating for internal consistency. Likewise, if a measure had multiple ratings for a PAPERS property across articles in the packet, those ratings were “rolled up” by computing and assigning the median rating to the measure as its final rating for that PAPERS property. If a measure was used in four different studies, the measure’s internal consistency was rated for each article and the median of those ratings was assigned to the measure as its final rating for internal consistency. If the computed median resulted in a non-integer rating, the non-integer rating was rounded down (e.g., a median rating of 2.5 was rounded down to a 2). This decision results in a conservative rating. The “rolled up” median approach—intended to offer potential users of a measure a single rating for each PAPERS property—offers a less negative assessment of a PAPERS property than the “worst counts” approach wherein a PAPERS property is assigned the lowest rating for that property when there are multiple ratings (Lewis et al., 2015; Terwee et al., 2012). To give potential users a sense of the variability of ratings that were “rolled up” into a median, the range of ratings (high and low) is reported for PAPERS properties where there are multiple ratings. Once these steps were applied, a total score was calculated for each measure by summing the final ratings. The maximum possible rating is 36; the minimum is −9.

Descriptive data were also extracted (Table 2). These variables included construct definition, number of scales in the measure, number of items in the measure, number of uses of the measure in mental or behavioral health care, country of origin, target setting, target respondent, target problem, and implementation outcome assessed (Proctor et al., 2011). Data were also collected on the number of articles contained in each packet, providing bibliometric data for each measure.

Table 2.

Description of measures and subscales.

| Readiness for

implementation (n = 9) |

Leadership

engagement (n = 24) |

Available

resources (n = 17) |

Access to

knowledge (n = 6) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Concept defined | ||||||||

| Yes | 8 | 89 | 18 | 75 | 15 | 88 | 5 | 83 |

| No | 1 | 11 | 6 | 25 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 17 |

| One-time use only | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 44 | 15 | 63 | 7 | 41 | 5 | 83 |

| No | 5 | 56 | 9 | 38 | 10 | 59 | 1 | 17 |

| Number of scales | ||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 21 | 3 | 18 | 1 | 17 |

| 2–5 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 38 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 33 |

| 6 or more | 8 | 89 | 10 | 42 | 12 | 71 | 3 | 50 |

| Number of itemsa | ||||||||

| 1–5 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| 6–10 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 13 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 17 |

| 11 or more | 7 | 78 | 18 | 75 | 14 | 82 | 3 | 50 |

| Country | ||||||||

| The United States | 9 | 100 | 20 | 83 | 15 | 88 | 5 | 83 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 4 | 17 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 17 |

| Settingb | ||||||||

| State mental health | 0 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 17 |

| Inpatient psychiatry | 1 | 11 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 24 | 1 | 17 |

| Outpatient community | 7 | 78 | 14 | 58 | 14 | 82 | 4 | 67 |

| School mental health | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Residential care | 2 | 22 | 6 | 25 | 8 | 47 | 1 | 17 |

| Other | 7 | 78 | 12 | 50 | 9 | 53 | 4 | 67 |

| Levelb | ||||||||

| Consumer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| Organization | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinic/site | 3 | 33 | 4 | 17 | 6 | 35 | 1 | 17 |

| Provider | 7 | 78 | 17 | 71 | 13 | 76 | 3 | 50 |

| System | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Team | 1 | 11 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Director | 6 | 67 | 7 | 29 | 11 | 65 | 3 | 50 |

| Supervisor | 6 | 67 | 11 | 46 | 7 | 41 | 2 | 33 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 5 | 21 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 17 |

| Populationb | ||||||||

| General mental health | 4 | 44 | 14 | 58 | 9 | 53 | 2 | 33 |

| Anxiety | 1 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression | 3 | 34 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 18 | 2 | 33 |

| Suicidal ideation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 1 | 12 | 3 | 13 | 4 | 24 | 2 | 33 |

| Substance use disorder | 6 | 67 | 10 | 42 | 8 | 47 | 2 | 33 |

| Behavioral disorder | 1 | 12 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 17 |

| Mania | 0 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Eating disorder | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grief | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tic disorder | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trauma | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 3 | 34 | 5 | 21 | 3 | 18 | 1 | 17 |

| Outcomes assessed | ||||||||

| Acceptability | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Appropriateness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adoption | 2 | 23 | 3 | 13 | 11 | 65 | 0 | 0 |

| Cost | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Feasibility | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fidelity | 1 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 17 |

| Penetration | 1 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Sustainability | 1 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

Some measures did not report total number of items.

Some measures were used in multiple settings, levels, populations, and outcomes.

Phase III: data analysis

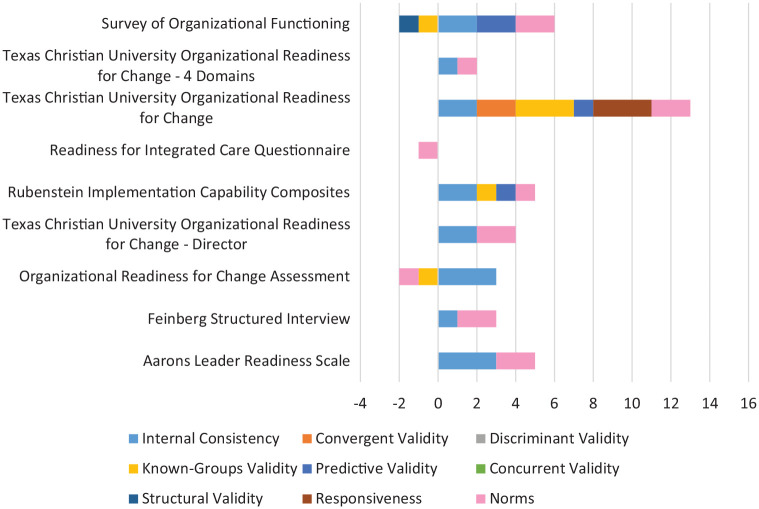

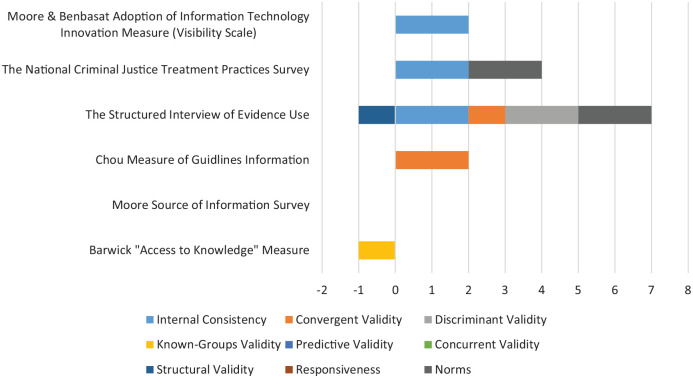

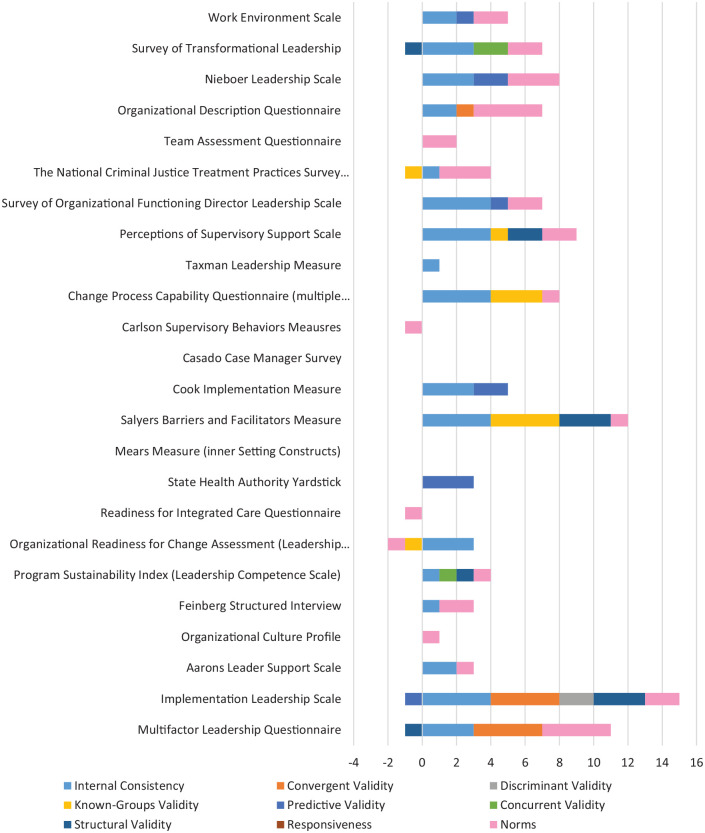

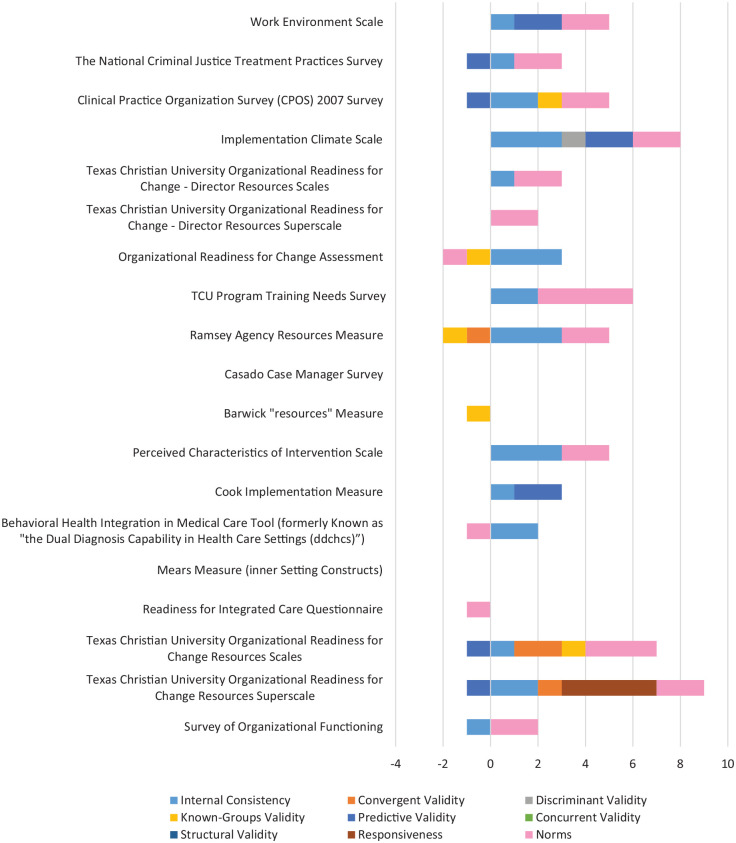

Tables 3 and 4 report the presence or absence of psychometric and pragmatic information for each measure, by focal construct (i.e., readiness for implementation and its sub-constructs, as delineated in CFIR). Table 5 summarizes the availability of psychometric and pragmatic information for each PAPERS property for the measures of each construct. Table 6 displays for each focal construct the median and range of ratings for each PAPERS property, summarizing the psychometric and pragmatic strength of the measures of each construct. Tables 7 and 8 report the median and range of ratings for each PAPERS property for each measure, by construct. Figures 1 to 4 contain bar charts to display visual head-to-head comparisons across all measures, by construct.

Table 3.

Availability of psychometric information for measures, by focal construct.

| Internal consistency | Convergent validity | Discriminant validity | Known-groups validity | Predictive validity | Concurrent validity | Structural validity | Responsiveness | Norms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readiness for implementation | |||||||||

| Aarons Leader Readiness Scale | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Feinberg Structured Interview | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Rubenstein Implementation Capability Composites | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—4 Domains | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Survey of Organizational Functioning | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Construct total (out of 9 measures) | 8 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Leadership engagement | |||||||||

| Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Implementation Leadership Scale | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Aarons Leader Support Scale | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Organizational Culture Profile | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Feinberg Structured Interview | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Program Sustainability Index | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire (Leadership Scale) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| State Health Authority Yardstick | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mears Measure (inner Setting Constructs) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salyers Barriers and Facilitators Measure (Agency Leader Support) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cook Implementation Measure (Managerial Relations and Leadership and Vision Scales) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Casado Case Manager Survey (Leadership Scale) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Carlson Supervisory Behaviors Measures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Change Process Capability Questionnaire (multiple items pertaining to leadership) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Taxman Leadership Measure | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Perceptions of Supervisory Support Scale | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Survey of Organizational Functioning (Director Leadership Scale) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Team Assessment Questionnaire (Team Leadership Scale) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Organizational Description Questionnaire | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Nieboer Leadership Scale | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Survey of Transformational Leadership | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Work Environment Scale | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Construct total (out of 24 measures) | 17 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 19 |

| Available resources | |||||||||

| Survey of Organizational Functioning (OTCE scales) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change Resources Superscale | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change Resources Scales | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire (Resource Utilization Scales) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mears Measure (Resources) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Behavioral Health Integration in Medical Care Tool (Staffing and Training Scales) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cook Implementation Measure (Time and Resources Scales) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Perceived Characteristics of Intervention Scale (Technical Support Scale) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Barwick “Resources” Measure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Casado Case Manager Survey | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ramsey Agency Resources Measure | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Program Training Needs Survey | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment (General Resources Scale) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director Resources Superscale | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director Resources Scales | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Implementation Climate Scale (Educational Support) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Clinical Practice Organization Survey (CPOS) 2007 Survey (Adequacy of Resources) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Physical, Training, Staffing, Funding) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Work Environment Scale (Physical Comfort Scale) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Construct total (out of 19 measures) | 14 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| Access to knowledge and information | |||||||||

| Barwick “Access to Knowledge” Measure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moore Source of Information Survey | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chou Measure of Guidelines Information | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The Structured Interview of Evidence Use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Sources of Information Scale) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Moore and Benbasat Adoption of Information Technology Innovation Measure (Visibility Scale) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Construct total (out of 6 measures) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

OCTE, Offices, Staffing, Training, Computer Access, and E-Communications Scales.

Table 4.

Availability of pragmatic information for measures, by focal construct.

| Cost | Reading | Training | Interpret | Length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readiness for implementation | |||||

| Aarons Leader Readiness Scale | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Feinberg Structured Interview | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Rubenstein Implementation Capability Composites | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—4 Domains | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Survey of Organizational Functioning | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Construct total (out of 9 measures) | 6 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 9 |

| Leadership engagement | |||||

| Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Implementation Leadership Scale | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Aarons Leader Support Scale | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Organizational Culture Profile | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Feinberg Structured Interview | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Program Sustainability Index (Leadership Competence Scale) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment (Leadership Scales) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire (Leadership Scale) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| State Health Authority Yardstick | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mears Measure (inner Setting Constructs) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salyers Barriers and Facilitators Measure (Agency Leader Support) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cook Implementation Measure (Managerial Relations and Leadership and Vision Scales) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Casado Case Manager Survey (Leadership Scale) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Carlson Supervisory Behaviors Measures | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Change Process Capability Questionnaire (multiple items pertaining to leadership) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Taxman Leadership Measure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Perceptions of Supervisory Support Scale | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Survey of Organizational Functioning (Director Leadership Scale) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Leadership Scale) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Team Assessment Questionnaire (Team Leadership Scale) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Organizational Description Questionnaire | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nieboer Leadership Scale | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Survey of Transformational Leadership | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Work Environment Scale | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Construct total (out of 24 measures) | 12 | 13 | 4 | 6 | 20 |

| Available resources | |||||

| Survey of Organizational Functioning (OTCE scales) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change Resources Superscale | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change Resources Scales | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire (Resource Utilization Scales) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mears Measure (Resources) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Behavioral Health Integration in Medical Care Tool (Staffing and Training Scales) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cook Implementation Measure (Time and Resources Scales) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Perceived Characteristics of Intervention Scale (Technical Support Scale) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Barwick “resources” Measure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Casado Case Manager Survey | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ramsey Agency Resources Measure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Program Training Needs Survey | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment (General Resources Scale) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director Resources Superscale | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director Resources Scales | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Implementation Climate Scale (Educational Support) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Clinical Practice Organization Survey (CPOS) 2007 Survey (Adequacy of Resources) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Physical, Training, Staffing, Funding) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Work Environment Scale (Physical Comfort Scale) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Construct total (out of 19 measures) | 14 | 13 | 1 | 6 | 15 |

| Access to knowledge and information | |||||

| Barwick “Access to Knowledge” Measure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moore Source of Information Survey | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chou Measure of Guidelines Information | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The Structured Interview of Evidence Use | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Sources of Information Scale) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moore and Benbasat Adoption of Information Technology Innovation Measure (Visibility Scale) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Construct total (out of 6 measures) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Table 5.

Psychometric and pragmatic information availability.

| Readiness for

implementation (n = 09) |

Leadership

engagement (n = 24) |

Available

resources (n = 19) |

Access to

knowledge (n = 06) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Internal consistency | 8 | 89 | 17 | 71 | 14 | 74 | 3 | 50 |

| Convergent validity | 1 | 11 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 16 | 2 | 33 |

| Discriminant validity | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| Known-groups validity | 4 | 44 | 5 | 21 | 6 | 32 | 1 | 17 |

| Predictive validity | 3 | 44 | 6 | 25 | 8 | 42 | 1 | 17 |

| Concurrent validity | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Structural validity | 1 | 11 | 6 | 25 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 17 |

| Responsiveness | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Norms | 9 | 100 | 19 | 79 | 15 | 79 | 2 | 33 |

| Cost | 6 | 66 | 12 | 50 | 14 | 74 | 2 | 33 |

| Language | 6 | 66 | 13 | 54 | 13 | 68 | 2 | 33 |

| Burden (training) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 17 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Burden (interpretation) | 4 | 44 | 6 | 25 | 6 | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| Brevity | 9 | 100 | 20 | 83 | 15 | 79 | 2 | 33 |

Table 6.

Summary statistics for instrument ratings.a

| Readiness for

implementation (n = 09) |

Leadership

engagement (n = 24) |

Available

resources (n = 19) |

Access to

knowledge (n = 06) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | |

| Internal consistency | 2 | 1,3 | 3 | 1,4 | 2 | −1,3 | 2 | – |

| Convergent validity | 2 | – | 4 | 3,4 | 1 | −1,2 | 1 | 1,2 |

| Discriminant validity | – | – | 2 | 2 | – | – | 2 | – |

| Known-groups validity | 1 | −1,2 | 1 | −1,4 | −1 | −1,3 | −1 | – |

| Predictive validity | 1 | 1,2 | 1 | −1,3 | 1 | −1,3 | −1 | – |

| Concurrent validity | – | – | 1 | 1,2 | – | – | – | – |

| Structural validity | −1 | – | 2 | −1,3 | 2 | – | −1 | – |

| Responsiveness | 2 | 2,3 | – | – | 4 | – | – | – |

| Norms | 2 | −1,2 | 2 | −1,4 | 2 | −1,4 | 2 | – |

| Cost | 4 | – | 4 | −1,4 | 4 | 2,4 | 2 | – |

| Language | 3 | 2,4 | 3 | 2,4 | 3 | 2,4 | 3 | 3,4 |

| Burden (training) | – | – | 3 | 2,4 | 2 | – | – | – |

| Burden (interpretation) | 1 | – | 1 | −1,1 | 1 | – | – | – |

| Brevity | 2 | 1,4 | 3 | 2,4 | 4 | 2,4 | 2 | 2,3 |

Median, excluding zeros where psychometric or pragmatic information not available.

Table 7.

Psychometric ratings for measures (median and range), by focal construct.

| Internal consistency | Convergent validity | Discriminant validity | Known-groups validity | Predictive validity | Concurrent validity | Structural validity | Responsiveness | Norms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readiness for implementation | |||||||||

| Aarons Leader Readiness Scale | 3 () |

2 () |

|||||||

| Feinberg Structured Interview | 1 () |

2 () |

|||||||

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment | 3 (3,3) |

−1 (–1,–1) |

−1 (–1,3) |

||||||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director | 2 (1,2) |

2 (2,2) |

|||||||

| Rubenstein Implementation Capability Composites | 2 () |

1 () |

1 () |

1 () |

|||||

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire | −1 () |

||||||||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change | 2 (1,3) |

2 (1,3) |

2 (1,3) |

1 (–1,2) |

3 () |

2 (–1,4) |

|||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—4 Domains | 1 (1,1) |

1 () |

2 () |

2 (1,2) |

|||||

| Survey of Organizational Functioning | 2 (1,3) |

−1 () |

2 (1,3) |

−1 (–1,2) |

2 (–1,4) |

||||

| Construct total (out of 9 measures) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Leadership engagement | |||||||||

| Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire | 3 (2,4) |

4 () |

−1 () |

4 () |

|||||

| Implementation Leadership Scale | 4 (4,4) |

4 () |

2 () |

−1 () |

3 (3,4) |

2 (–1,4) |

|||

| Aarons Leader Support Scale | 2 () |

1 () |

|||||||

| Organizational Culture Profile | 1 () |

||||||||

| Feinberg Structured Interview | 1 () |

2 () |

|||||||

| Program Sustainability Index (Leadership) | 3 () |

1 () |

2 () |

2 () |

|||||

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment | 3 (3,4) |

−1 () |

−1 (–1,1) |

||||||

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire (Leadership Scale) | −1 () |

||||||||

| State Health Authority Yardstick | 3 () |

||||||||

| Mears Measure (inner Setting Constructs) | |||||||||

| Salyers Barriers and Facilitators Measure (Agency Leader Support) | 4 () |

4 () |

3 () |

1 () |

|||||

| Cook Implementation Measure (Managerial Relations and Leadership and Vision Scales) | 3 () |

2 () |

|||||||

| Casado Case Manager Survey (Leadership Scale) | |||||||||

| Carlson Supervisory Behaviors Measures | |||||||||

| Change Process Capability Questionnaire (multiple items pertaining to leadership) | 4 () |

3 (3,4) |

1 (–1,3) |

||||||

| Taxman Leadership Measure | 1 () |

||||||||

| Perceptions of Supervisory Support Scale | 4 () |

1 () |

2 () |

2 () |

|||||

| Survey of Organizational Functioning (Director Leadership Scale) | 4 (4,4) |

1 () |

2 (2,4) |

||||||

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey | 1 () |

−1 () |

3 () |

||||||

| Team Assessment Questionnaire (Team Leadership Scale) | 2 () |

||||||||

| Organizational Description Questionnaire | 2 () |

3 () |

4 () |

||||||

| Nieboer Leadership Scale | 3 () |

2 () |

3 () |

||||||

| Survey of Transformational Leadership | 3 (3,3) |

2 () |

−1 () |

2 (2,2) |

|||||

| Work Environment Scale | 2 () |

1 () |

2 (–1,2) |

||||||

| Construct total (out of 24 measures) | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Available resources | |||||||||

| Survey of Organizational Functioning (OTCE scales) | −1 (–1,2) |

2 (–1,3) |

|||||||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change Resources Superscale | 2 (–1,3) |

1 () |

1 (1,2) |

4 () |

2 (–1,4) |

||||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change Resources Scales | 1 (–1,2) |

2 () |

1 (1,3) |

−1 (–1,2) |

3 (2,4) |

||||

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire (Resource Utilization Scales) | −1 () |

||||||||

| Mears Measure (Resources) | |||||||||

| Behavioral Health Integration in Medical Care Tool (Staffing and Training Scales) | 2 () |

−1 () |

|||||||

| Cook Implementation Measure (Time and Resources Scales) | 1 () |

2 () |

|||||||

| Perceived Characteristics of Intervention Scale (Technical Support Scale) | 3 (2,4) |

2 (2,4) |

|||||||

| Barwick “resources” Measure | −1 () |

||||||||

| Casado Case Manager Survey | |||||||||

| Ramsey Agency Resources Measure | 3 () |

−1 () |

−1 () |

3 () |

|||||

| Texas Christian University Program Training Needs Survey | 2 (2,2) |

3 () |

3 () |

4 () |

|||||

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment (General Resources Scale) | 3 () |

−1 (–1,–1) |

−1 (–1,1) |

||||||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director Resources Superscale | 2 () |

||||||||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director Resources Scales | 1 (–1,2) |

2 () |

|||||||

| Implementation Climate Scale (Educational Support) | 3 (3,3) |

2 () |

2 () |

2 (–1,4) |

|||||

| Clinical Practice Organization Survey (CPOS) 2007 Survey (Adequacy of Resources) | 2 () |

1 () |

−1 () |

2 () |

|||||

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Physical, Training, Staffing, Funding) | 1 (1,2) |

−1 (–1,2) |

2 (1,2) |

||||||

| Work Environment Scale (Physical Comfort Scale) | 1 () |

2 () |

2 (–1,2) |

||||||

| Construct total (out of 19 measures) | 2 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Access to knowledge and information | |||||||||

| Barwick “Access to Knowledge” Measure | −1 () |

||||||||

| Moore Source of Information Survey | |||||||||

| Chou Measure of Guidelines Information | 2 () |

−1 () |

|||||||

| The Structured Interview of Evidence Use | 2 () |

1 () |

2 () |

−1 () |

2 () |

||||

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Sources of Information Scale) | 2 () |

2 () |

|||||||

| Moore and Benbasat Adoption of Information Technology Innovation Measure (Visibility Scale) | 2 () |

||||||||

| Construct total (out of 6 measures) | 2 | 1 | 2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 2 | ||

Table 8.

Pragmatic ratings for measures, by focal construct.

| Cost | Reading | Training | Interpret | Length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readiness for implementation | |||||

| Aarons Leader Readiness Scale | 4 | ||||

| Feinberg Structured Interview | 2 | ||||

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Rubenstein Implementation Capability Composites | 4 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire | 2 | ||||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—4 Domains | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Survey of Organizational Functioning | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Construct total (out of 9 measures) | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Leadership engagement | |||||

| Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire | 2 | 2 | −1 | 2 | |

| Implementation Leadership Scale | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Aarons Leader Support Scale | |||||

| Organizational Culture Profile | 2 | ||||

| Feinberg Structured Interview | 2 | ||||

| Program Sustainability Index (Leadership Competence Scale) | 3 | 4 | |||

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment (Leadership Scales) | 4 | 3 | |||

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire (Leadership Scale) | |||||

| State Health Authority Yardstick | 1 | 4 | |||

| Mears Measure (inner Setting Constructs) | |||||

| Salyers Barriers and Facilitators Measure (Agency Leader Support) | 2 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Cook Implementation Measure (Managerial Relations and Leadership and Vision Scales) | 4 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Casado Case Manager Survey (Leadership Scale) | 4 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Carlson Supervisory Behaviors Measures | 2 | 3 | |||

| Change Process Capability Questionnaire (multiple items pertaining to leadership) | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Taxman Leadership Measure | 4 | ||||

| Perceptions of Supervisory Support Scale | 4 | 3 | |||

| Survey of Organizational Functioning (Director Leadership Scale) | 4 | 3 | 4 | ||

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Leadership Scale) | |||||

| Team Assessment Questionnaire (Team Leadership Scale) | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |

| Organizational Description Questionnaire | −1 | 4 | 4 | −1 | 3 |

| Nieboer Leadership Scale | 3 | ||||

| Survey of Transformational Leadership | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Work Environment Scale | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Construct total (out of 24 measures) | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Available resources | |||||

| Survey of Organizational Functioning (OTCE scales) | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change Resources Superscale | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change Resources Scales | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | |

| Readiness for Integrated Care Questionnaire (Resource Utilization Scales) | |||||

| Mears Measure (Resources) | |||||

| Behavioral Health Integration in Medical Care Tool (Staffing and Training Scales) | 4 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Cook Implementation Measure (Time and Resources Scales) | 4 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Perceived Characteristics of Intervention Scale (Technical Support Scale) | 4 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Barwick “resources” Measure | |||||

| Casado Case Manager Survey | 4 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Ramsey Agency Resources Measure | 4 | ||||

| Texas Christian University Program Training Needs Survey | 4 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment (General Resources Scale) | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director Resources Superscale | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change—Director Resources Scales | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Implementation Climate Scale (Educational Support) | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

| Clinical Practice Organization Survey (CPOS) 2007 Survey (Adequacy of Resources) | 4 | 3 | 4 | ||

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Physical, Training, Staffing, Funding) | |||||

| Work Environment Scale (Physical Comfort Scale) | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Construct total (out of 19 measures) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Access to knowledge and information | |||||

| Barwick “Access to Knowledge” Measure | |||||

| Moore Source of Information Survey | |||||

| Chou Measure of Guidelines Information | |||||

| The Structured Interview of Evidence Use | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||

| The National Criminal Justice Treatment Practices Survey (Sources of Information Scale) | |||||

| Moore and Benbasat Adoption of Information Technology Innovation Measure (Visibility Scale) | 2 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Construct total (out of 6 measures) | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||

Figure 1.

Head-to-head comparison of measures of readiness.

Figure 4.

Head-to-head comparison of measures of access to knowledge and information.

Figure 2.

Head-to-head comparison of measures of leadership engagement.

Figure 3.

Head-to-head comparison of measures of resource availability.

Results

Search results

Searches of electronic bibliographic databases yielded 9 measures of readiness for implementation used in mental or behavioral health care; 24 measures of leadership engagement, of which 10 were scales of measures of readiness for implementation or scales of measures of other constructs; 17 measures of available resources, of which all but 2 were scales of measures of readiness for implementation or scales of measures of other constructs; and 6 measures of access to knowledge, of which 2 were scales of measures of other constructs.

Table 2 describes measures used to assess readiness for implementation, leadership engagement, available resources, and access to knowledge and information in mental or behavioral health care. Most measures of readiness for implementation defined the construct of readiness (89%), possessed six or more scales (89%), and included 11 or more items (78%). Many were used more than once (56%). All originated in the United States (100%). Most were employed in the outpatient community setting (78%), with providers (78%), directors (67%), or supervisors (67%) as respondents. These measures were used most commonly to assess readiness to implement evidence-based practice (EBPs) in substance use disorder (67%) or general mental health (44%). Two measures were used to predict implementation outcomes: the Texas Christian University Organizational Readiness for Change, or TCU-ORC (adoption) (Henggeler et al., 2008), (fidelity) (Beidas et al., 2014; Henggeler et al., 2008; Lundgren et al., 2013), (penetration) (Beidas et al., 2012, 2014; Guerrero et al., 2014), and (sustainability) (Hunter et al., 2017), and the Texas Christian University Survey of Organizational Functioning, or TCU-SOF (adoption) (Becan et al., 2012).

Measures of leadership engagement, available resources, and access to knowledge and information in mental or behavioral health care reported descriptive patterns similar to those for measures of readiness for implementation. The exception to the pattern was that many to most measures of leadership engagement and access to knowledge and information were only used once (63% and 83%, respectively). Four measures of leadership engagement were used to predict implementation outcomes: the Cook Implementation Measure managerial relations scale and leadership and vision scale (adoption) (Cook et al., 2015); the TCU-SOF leadership scale (adoption) (Becan et al., 2012), the State Health Authority Yardstick (fidelity and penetration) (Finnerty et al., 2009); and the Implementation Leadership Scale (sustainability) (Hunter et al., 2017). Several measures of available resources were used to predict implementation outcomes: the TCU-SOF funding, physical plant, staffing, training development, resources, and internal support scales (adoption) (Henderson et al., 2008); the Clinical Practice Organization Survey financial insufficiency, space insufficiency, clinical provider insufficiency scales (adoption) (Chang et al., 2013); and the TCU-ORC training resources and resources superscale (adoption) (Henggeler et al., 2008; Herbeck et al., 2008), (fidelity) (Beidas et al., 2014), and (penetration) (Beidas et al., 2014). The Chou Measure of Guidelines Information (Chou et al., 2011) is the only access to knowledge and information measure that was used to predict an implementation outcome (fidelity).

Measure ratings

Readiness for implementation

Damschroder et al. (2009) define readiness for implementation as “tangible and immediate indicators of organizational commitment to its decision to implement an intervention.” Nine measures were used in mental or behavioral health care. Table 5 summarizes the psychometric and pragmatic evidence available for these measures. Evidence about internal consistency was available for eight measures, convergent validity for one measure, discriminant validity for no measures, known-groups validity for four measures, predictive validity for three measures, concurrent validity for no measures, structural validity for one measure, responsiveness for one measures, and norms for nine measures. Information for the pragmatic property of cost was available for six measures, language readability for six measures, assessor burden (training) for no measures, assessor burden (interpretation) for four measures, and brevity for nine measures.

Table 6 describes the median ratings and range of ratings for psychometric and pragmatic properties for those measures for which evidence or information was available (i.e., those with non-zero ratings on PAPERS criteria). For measures of readiness for implementation used in mental or behavioral health care, the median rating for internal consistency was “2—adequate,” for convergent validity “2—adequate,” for known-groups validity “1—minimal,” for predictive validity “1—minimal,” for structural validity “–1—poor,” for responsiveness “2—adequate,” and for norms “2—adequate.” Note the median rating of “–1—poor” for structural validity was based on the rating of just one measure: the Survey of Organizational Functioning (Broome et al., 2007).

The TCU-ORC (Lehman et al., 2002) had the highest overall psychometric rating among measures of readiness for implementation used in mental or behavioral health care (psychometric total score = 12; maximum possible score = 36), with ratings of “3—good” for responsiveness and “2—adequate” for internal consistency, convergent validity, known-groups validity, and norms. However, the TCU-ORC was not assessed for structural validity using either exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis; consequently, its internal structure remains untested beyond a principal components analysis despite its use in more than 89 studies in mental and behavioral health care. Its predictive validity rating is “1—minimal” despite 87 tests of association between individual scales and a variety of outcomes.

For the nine measures of readiness for implementation used in mental or behavioral health care, the median rating for the pragmatic property of cost was “4—excellent,” for language “3—good,” for assessor burden (interpretation) “1—minimal,” and for brevity “2—adequate.” All nine measures of readiness for implementation used in mental or behavioral health care are free, hence the high pragmatic rating for cost. The TCU-ORC, the measure with the highest overall psychometric rating, scored a 9 out of 20 possible points for pragmatic criteria, with a “4—excellent” for cost, a “3—good” for language readability, and a “1—minimal” for assessor burden (interpretation) and brevity. However, no information was available for assessor burden (training). The four superscale version of the TCU-ORC scores were somewhat higher with 10 out of 20 possible points, the additional point resulting from a rating of “4—excellent” for language readability.

Leadership engagement

Damschroder et al. (2009) regard leadership engagement as a sub-construct of readiness for implementation and define it as “commitment, involvement, and accountability of leaders and managers with the implementation.” Twenty-four measures were used in mental or behavioral health care. Table 5 summarizes the psychometric and pragmatic evidence available for these measures. Evidence about internal consistency was available for 17 measures, convergent validity for 3 measures, discriminant validity for 1 measure, known-groups validity for 5 measures, predictive validity for 6 measures, concurrent validity for 2 measures, structural validity for 6 measures, responsiveness for no measures, and norms for 19 measures. Information for the pragmatic property of cost was available for 12 measures, language readability for 13 measures, assessor burden (training) for 4 measures, assessor burden (interpretation) for 6 measures, and brevity for 20 measures.

For measures of leadership engagement used in mental or behavioral health care (Table 6), the median rating for internal consistency was “3—good,” for convergent validity “4—excellent,” for discriminant validity “2—adequate,” for known-groups validity “1—minimal,” for predictive validity “1—minimal,” for concurrent validity “1—minimal,” for structural validity “2—adequate,” and for norms “2—adequate.” Note the median rating of “2—adequate” for discriminant validity was based on the rating of just one measure: the Implementation Leadership Scale (Aarons et al., 2014).

The Implementation Leadership Scale (Aarons et al., 2014) had the highest overall rating among measures of leadership engagement used in mental and behavioral health care (psychometric total score = 14; maximum possible score = 36), with ratings of “4—excellent” for internal consistency and convergent validity, “3—good” for structural validity, and “2—adequate” for discriminant validity and norms. However, its predictive validity rating was “–1—poor” based on a single study in which implementation leadership was not significantly associated with the extent of sustainment of an evidence-based treatment to address adolescent substance use following the end of federally funded implementation support grants to 78 community-based organizations (Hunter et al., 2017).

For the 24 measures of leadership engagement used in mental or behavioral health care, the median rating for the pragmatic property of cost was “4—excellent,” for language readability “3—good,” for assessor burden (training) “3—good,” for assessor burden (interpretation) “1—minimal,” and for brevity “3—good.” The Implementation Leadership Scale, the measure with the highest overall psychometric rating, scored a 10 out of a possible 20 points for pragmatic criteria, with a “4—excellent” for cost, “3—good” for brevity, and a “2—adequate” for language readability. However, no information was available for assessor burden (training) and assessor burden (interpretation) was rated “1—minimal.” The Team Leadership Scale of the Team Assessment Questionnaire (Mahoney et al., 2012) received the highest score on pragmatic criteria (15 points out of a possible 20), with ratings of “4—excellent” for cost, assessor burden (training), and brevity, and “3—good” for language readability. No information was available on assessor burden (interpretation).

Available resources

Damschroder et al. (2009) regard available resources as a sub-construct of readiness for implementation and define it as “the level of resources for implementation and on-going operations including money, training, education, physical space, and time.” Nineteen measures were identified in mental and behavioral health care. Table 5 summarizes the psychometric and pragmatic evidence available for these measures. Evidence about internal consistency was available for 14 measures, convergent validity for 3 measures, discriminant validity for no measures, known-groups validity for 6 measures, predictive validity for 8 measures, concurrent validity for no measures, structural validity for 1 measure, responsiveness for 1 measure, and norms for 15 measures. Information for the pragmatic property of cost was available for 14 measures, language readability for 13 measures, assessor burden (training) for 1 measure, assessor burden (interpretation) for 6 measures, and brevity for 15 measures.

For measures of available resources used in mental or behavioral health care (Table 6), the median rating for internal consistency was “2—adequate,” for convergent validity “1—minimal,” for known-groups validity “–1—poor,” for predictive validity “1—minimal,” for structural validity “2—adequate,” for responsiveness “4—excellent,” and for norms “2—adequate.” Note the median rating of “1—minimal” for structural validity was based on the rating of just one measure: the Educational Support scale of the Implementation Climate Scale (Ehrhart et al., 2014). Likewise, the median rating of “4—excellent” for responsiveness was based on the rating of just one measure: the Resources superscale of the TCU-ORC (Lehman et al., 2002).

The Texas Christian University Program Training Needs Survey (Simpson, 2002) had the highest overall rating among measures of available resources used in mental or behavioral health care (psychometric total score = 12; maximum possible score = 36), with ratings of “4—excellent” for norms, “3—good” for known-groups and predictive validity, and “2—adequate” for internal consistency. However, the TCU-ORC Program Training Needs Survey has not been assessed for structural validity using either exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis; consequently, its internal structure remains untested.

For the 19 measures of available resources used in mental or behavioral health care, the median rating for the pragmatic property of cost was “4—excellent,” for language readability “3—good,” for assessor burden (training) “2—adequate,” for assessor burden (interpretation) “1—minimal,” and for brevity “4—excellent.” Note the median rating of “2—adequate” for assessor burden (training) was based on the rating of just one measure: the Work Environment Scale (Simpson, 2002). The TCU-ORC Program Training Needs Survey, the measure with the highest overall psychometric rating, scored a 9 out of a possible 20 points for pragmatic criteria. However, no information was available for assessor burden (training) or assessor burden (interpretation). Measures that received higher scores on PAPERS pragmatic criteria include the General Resources scale of the TCU-ORC and the Director Resources scale of the TCU-ORC Director Version, both of which scored 12 out of 20 possible points for pragmatic criteria.

Access to knowledge and information

Damschroder et al. (2009) regard access to knowledge and information as a sub-construct of readiness for implementation and define it as “easy access to digestible information and knowledge about the intervention and how to incorporate it into work tasks.” Six measures were identified in mental and behavioral health care. Table 5 describes the psychometric and pragmatic evidence available for these measures. Evidence about internal consistency was available for three measures, convergent validity for two measures, discriminant validity for one measure, known-groups validity for one measures, predictive validity for one measure, concurrent validity for no measures, structural validity for one measure, responsiveness for no measures, and norms for two measures. Information for the pragmatic property of cost was available for two measures, language readability for two measures, assessor burden (training) for no measures, assessor burden (interpretation) for no measures, and brevity for two measures.

For measures of access to knowledge and information used in mental or behavioral health care (Table 6), the median rating for internal consistency was “2—adequate,” for convergent validity “1—minimal,” for discriminant validity “2—adequate,” for known-groups validity “–1—poor,” for predictive validity “–1—poor,” for structural validity “1—poor,” and for norms “2—adequate.” Note that the median ratings for discriminant validity, known-groups validity, predictive validity, and structural validity are based on the ratings of a single measure, although not the same measure in all instances.

The Structured Interview of Evidence Use (Palinkas et al., 2016) had the highest overall rating among measures of access to knowledge and information used in mental or behavioral health care (psychometric total score = 6; maximum possible score = 36), with ratings of “2—adequate” for internal consistency, discriminant validity, and norms; and “1—minimal” for convergent validity. However, the measure was rated “–1—poor” for structural validity, indicating more work is needed to ascertain its internal structure.

Of the six measures of access to knowledge and information used in mental or behavioral health care, only two had information available on the PAPERS pragmatic criteria. The Structured Interview of Evidence Use, the measure with the highest overall psychometric rating, scored a 7 out of 20 possible points for pragmatic criteria, with a “3—good” for language readability and a “2—adequate” for cost and brevity. The Visibility Scale of the Moore and Benbasat Adoption of Information Technology Innovation measure scored somewhat higher with 9 out of 20 possible points, with a “4—excellent” for language readability, “3—good” for brevity, and a “2—adequate” for cost.

Discussion

The findings of this review indicate that measurement of organizational readiness for change in mental and behavioral health care, much like measurement in implementation science generally, is poor. Although the review identified fewer adapted, single-use measures than a comparable review of implementation outcomes (Lewis et al., 2015), a similarly uneven distribution of measures across readiness for change and it sub-constructs is apparent. For example, although many measures of leadership engagement have been developed or used in mental and behavioral health care, few measures of access to knowledge have been developed or used.

Consistent with previous reviews (Gagnon et al., 2014; Weiner et al., 2008), limited psychometric evidence was available for measures of readiness for implementation and its sub-constructs. Although evidence of internal consistency was available for most measures, evidence for other psychometric properties was often not available. Remarkably, evidence of structural validity was available for only 9 of the 58 measures included in the review. Good measurement practice dictates checking a measure’s dimensionality before checking its internal consistency (DeVellis, 2012). This apparently occurs infrequently. Also striking is the lack of evidence for two psychometric properties of importance to implementation scientists: predictive validity and responsiveness. Fewer than half of the measures have been tested for predictive validity; of these, few were tested for associations with implementation outcomes. Thus, the question of whether readiness for implementation matters remains open. Responsiveness, or sensitivity to change, is important for evaluating effectiveness of efforts to increase readiness for implementation or its sub-constructs. Yet, the responsiveness of measures developed or used in mental and behavioral health care is largely unknown; only 3 of 58 measures included in this review were tested for this psychometric property.

It is possible that poor reporting contributed to the limited and uneven availability of evidence regarding measures’ psychometric properties. Although many peer-reviewed journals require reporting of internal consistency, few require reporting of other psychometric properties. Inconsistent reporting was evident in this review, often making it difficult to rate the psychometric strength of measures even when the psychometric property was assessed. Although it is possible that researchers are assessing multiple psychometric properties of the measures they use and are simply not reporting these results, it is perhaps more probable that they are not employing rigorous, systematic measure development and testing processes.

Generally speaking, measures included in this review exhibited low psychometric quality. Although median ratings for internal consistency were “adequate” or “good,” median ratings for all other psychometric properties were less than “adequate.” The measures with the highest overall psychometric rating were the TCU-ORC (Lehman et al., 2002) for readiness for implementation, the Implementation Leadership Scale (Aarons et al., 2014) for leadership engagement, the Texas Christian University Program Training Needs Survey (Simpson, 2002) for available resources, and the Structured Interview of Evidence Use (Palinkas et al., 2016) for access to knowledge. None of these measures scored higher than 14 out of a maximum possible score of 36. The Implementation Leadership Scale is a relatively new measure that has not been used much in mental health or behavioral health care, yet exhibits “good” to “excellent” ratings for several psychometric properties and “adequate” ratings for others. With additional testing of its psychometric properties, and additional use in empirical studies, its overall psychometric rating would likely increase. Conversely, the TCU-ORC was used 89 times in mental health and behavioral health care yet has not improved in its psychometric properties with repeated use. Although some TCU-ORC scales consistently demonstrate “good” internal consistency (e.g., program needs, training needs, cohesion, and communication), other scales consistently demonstrate “minimal” or “poor” internal consistencies (e.g., training, equipment/computer access, internet/e-communication, growth, adaptability, and autonomy). In addition, some TCU-ORC scales demonstrate variable levels of internal consistency across studies (e.g., offices, efficacy, and change) for reasons that have not been explored. Moreover, the TCU-ORC has not been tested for structural validity with exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis, perhaps because its length (118 items across 18 scales) imposes daunting sample size needs for such validation. Although the TCU-ORC has exhibited statistically significant associations with implementation outcomes in some studies, it has not in others and no discernible pattern emerges across multiple studies. Despite 55 tests of association between individual TCU-ORC scales and various outcomes, the predictive validity rating of the measure remains “minimal.” Although the TCU-ORC exhibited the highest overall psychometric rating among the measures of readiness for implementation, more work is needed to improve the measure’s psychometric properties before further use of the measure.

This review is the first to systematically assess the pragmatic properties of readiness for implementation measures. Although information was generally available regarding measures’ cost, language readability, and brevity, information was less available regarding measures’ training burden and interpretation burden. Moreover, information was less available for measures of access to knowledge than for measures of readiness for implementation and its other sub-constructs. Median ratings varied considerably across pragmatic properties, with cost and language readability generally exhibiting “good” or “excellent” ratings, interpretation burden generally exhibiting “minimal” ratings, and training burden and brevity exhibiting mixed ratings across measures of readiness for implementation and its sub-constructs. Although the measures with the highest overall psychometric ratings were not the measures with the highest overall pragmatic ratings, it is possible for measures to be both psychometrically strong and pragmatic. For example, the Implementation Leadership Scale could increase its overall pragmatic rating by easing assessor burden through the development of a manual for self-trained administration or, better yet, automated administration, score calculation, and interpretation. Likewise, the actionability of the Implementation Leadership Scale could be enhanced by empirically establishing cut-off scores to guide decision-making (e.g., whether to move forward with implementation, or pause and take action to increase leadership engagement) (Zieky & Perie, 2006). The incorporation of pragmatic ratings into systematic measure reviews such as this one could lead to the salutary effect of prompting measure developers to attend to practical measurement considerations. This, in turn, would close the research-to-practice gap in measurement in implementation science.

Recommendations