Abstract

Background: Implementation scientists are identifying evidence-based implementation strategies that support the uptake of evidence-based practices and other clinical innovations. However, there is limited information regarding the development of training methods to educate implementation practitioners on the use of implementation strategies and help them sustain these competencies. Methods: To address this need, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a training program for one strategy, implementation facilitation (IF), that was designed to maximize applicability in diverse clinical settings. Trainees included implementation practitioners, clinical managers, and researchers. From May 2017 to July 2019, we sent trainees an electronic survey via email and asked them to complete the survey at three-time points: approximately 2 weeks before and 2 weeks and 6 months after each training. Participants ranked their knowledge of and confidence in applying IF skills using a 4-point Likert scale. We compared scores at baseline to post-training and at 6 months, as well as post-training to 6 months post-training (nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests). Results: Of the 102 participants (76 in-person, 26 virtual), there was an increase in perceived knowledge and confidence in applying IF skills across all learning objectives from pre- to post-training (95% response rate) and pre- to 6-month (35% response rate) follow-up. There was no significant difference in results between virtual and in-person trainees. When comparing post-training to 6 months (30% response rate), perceptions of knowledge increase remained unchanged, although participants reported reduced perceived confidence in applying IF skills for half of the learning objectives at 6 months. Conclusions: Findings indicated that we have developed a promising IF training program. Lack of differences in results between virtual and in-person participants indicated the training can be provided to a remote site without loss of knowledge/skills transfer but ongoing support may be needed to help sustain perceived confidence in applying these skills.

Plain Language Summary

While implementation scientists are documenting an increasing number of implementation strategies that support the uptake of evidence-based practices and other clinical innovations, little is known about how to transfer this knowledge to those who conduct implementation efforts in the frontline clinical practice settings. We developed, implemented, and conducted a preliminary evaluation of a training program for one strategy, implementation facilitation (IF). The training program targets facilitation practitioners, clinical managers, and researchers. This paper describes the development of the training program, the program components, and the results from an evaluation of IF knowledge and skills reported by a subset of people who participated in the training. Findings from the evaluation indicate that this training program significantly increased trainees' perceived knowledge of and confidence in applying IF skills. Further research is needed to examine whether ongoing mentoring helps trainees retain confidence in applying some IF skills over the longer term.

Keywords: Facilitation, implementation strategy implementation, training, coaching, evidence-based, knowledge transfer, implementation evaluation

Background

Complex evidence-based clinical innovations are challenging to implement, with many settings requiring implementation assistance to increase the likelihood of innovation uptake with fidelity. These efforts often require significant stakeholder engagement, support from multiple care specialties, and changes in provider attitudes, organizational processes, and clinical practice (Bauer et al., 2015; Kilbourne et al., 2004; Lindsay et al., 2015; Ritchie et al., 2020). Top-down mandates and bottom-up approaches alone are rarely sufficient to address these barriers to innovation uptake (Ferlie & Shortell, 2001; Greenhalgh et al., 2004; Parker et al., 2007, 2009; Ritchie et al., 2020).

With implementation science having emerged as an established field of scientific inquiry, researchers are identifying evidence-based implementation strategies that support the uptake of evidence-based practices (EBPs) and other clinical innovations (Bauer & Kirchner, 2020; Eccles & Mittman, 2006). Yet, little is known about how best to transfer the requisite knowledge and skills to those who can use them to effectively apply evidence-based implementation strategies in nonresearch initiatives.

There have been many calls to develop effective infrastructure to ensure that gains in advancing implementation science knowledge can be successfully transferred to clinical and operational healthcare leaders and frontline practitioners (Chambers et al., 2020; Kilbourne et al., 2019; Proctor et al., 2015). Proctor et al. (2015) engaged healthcare leaders, funders, and researchers to identify areas needed to support the sustainability of evidence-based healthcare innovations. Capacity development, or training of the healthcare workforce, was one of eleven domains identified for increased attention by these leaders. Specifically, they called upon foundations, universities, and professional associations to more effectively train practice leaders and frontline providers in evidence-based strategies that introduce, implement, and sustain advances in healthcare (Proctor et al., 2015). Thus, the field needs evaluated training methods to educate implementation practitioners on the use of evidence-based implementation strategies. Training will ensure a more rapid transfer of implementation science knowledge into the hands of those who can apply it more broadly, enhancing clinical and public health impact (Brownson et al., 2017). In this paper, we address these gaps in literature by describing the development, implementation, and preliminary evaluation of a training program focused on transferring knowledge and skills for one evidence-based strategy, IF.

Introduction to IF

Evidence supporting IF as an effective implementation strategy is expanding, and an increasing number of projects are using IF strategies to implement clinical innovations (Ayieko et al., 2011; Baskerville et al., 2001, 2012; Dickinson et al., 2014; Heidenreich et al., 2015; Kilbourne et al., 2014; Kirchner et al., 2014a, 2016; Mignogna et al., 2014; Nutting et al., 2009; Ritchie et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). IF is a multifaceted strategy involving a process of interactive problem-solving and support that occurs in a context of a recognized need for improvement and supportive interpersonal relationships (Powell et al., 2015). IF typically bundles an integrated set of activities and strategies to support the uptake of effective practices, including but not limited to: engaging stakeholders, identifying local change agents, goal-setting, action planning, staff training, problem-solving, providing technical support, audit/feedback, and marketing (Curran et al., 2008; Harvey et al., 2002; Nagykaldi et al., 2005; Stetler et al., 2006). The activities that facilitators apply, and when they apply them, depend upon the setting's context and recipients’ needs over the course of the implementation process (Harvey et al., 2002; Heron, 1977; Thompson et al., 2006). Facilitators require a high level of flexibility, communication, and interpersonal skills to apply these activities in a way that is responsive to a setting's needs over time (Cheater et al., 2005; Harvey et al., 2002).

Facilitation as an EBP

While the integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework guides our application of IF, multiple conceptual frameworks and planned action models accommodate the use of IF as a primary implementation strategy (Damschroder et al., 2009; Kilbourne et al., 2014). The i-PARIHS framework proposes that successful implementation of EBPs and other clinical innovations results from facilitation of implementation in partnership with recipients, considering characteristics of the innovation itself and the recipients’ inner and outer contexts. Successful implementation is defined as achievement of agreed-upon goals, uptake, and institutionalization of the innovation, engaged stakeholders who “own” the innovation, and minimization of variation related to context across implementation settings (Harvey & Kitson, 2015). Among i-PARIHS constructs, facilitation is the active ingredient, with facilitators supporting implementation by assessing and responding to characteristics of the recipients of the clinical innovation within the context of their own settings. A facilitator may be external or internal to an implementation setting and supports the implementation process through interactive problem solving with individuals at the site (Kirchner et al., 2014a). An increasing volume of literature supports IF as an evidence-based strategy for implementing EBPs and other clinical innovations (Kilbourne et al., 2014; Kirchner et al., 2014a; Nutting et al., 2009; Ritchie et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). Systematic reviews have found that primary care practices were almost three times more likely to adopt evidence-based guidelines through the use of facilitation (Baskerville et al., 2012); and multiple studies have shown IF to be an effective strategy for implementing new clinical programs and practices across diverse clinical settings, including but not limited to primary care, mental health, pediatric care, and hospital care settings (Ayieko et al., 2011; Dickinson et al., 2014; Heidenreich et al., 2015; Kilbourne et al., 2014; Kirchner et al., 2014a, 2016; Mignogna et al., 2014; Nutting et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2018).

The Need for IF Training Programs

An increase in empirical support for IF has resulted in a demand to ensure there is a skilled workforce with the core competencies required to successfully serve as IFs. Unfortunately, few individuals have the necessary training, skills, and knowledge to effectively apply IF and support evidence-based implementation.

Training programs and workshops are common ways to convey knowledge to participants about new professional competencies (Forsetlund et al., 2009). It is important to include an evaluation plan when developing these training programs and workshops to assess the impact of the training and identify which components are effective and which need improvement. Assessment of core knowledge, skill acquisition, and sustainment over time is a central component of the program evaluation (Valenstein-Mah et al., 2020). Training program evaluation should be multifactorial, include pre- and post-assessments, and assess learning and impact at later time points.

To address this gap, we developed, implemented, and evaluated an IF training program for IFs, researchers, and clinical leaders.

Methods

IF Training Program Development

Based on the early success of a Type III Hybrid IF study (Kirchner et al., 2014b), national clinical and operational leadership in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) expressed interest in using IF to support the implementation of VHA's Uniform Mental Health Services Handbook, which established clinical standards for VHA mental health treatment settings (Uniform Mental Health Services in VA Medical Centers and Clinics VHA Handbook 1160.01. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2008). These leaders wanted to build capacity at the national level for facilitating the implementation of this handbook by training and supporting the work of their technical assistance staff. Leaders understood the intricacy of the IF strategy, the value of the activities incorporated within it, and its flexibility to leverage complementary strategies/tools to support EBP implementation (particularly for complex clinical innovations).

In response to this request, we began collaborative discussions with these leaders to identify strategies to meet their goals, resource contributions, and future partnership activities. Literature and our own experiences suggested that our partners needed information on IF that was relevant, timely, and written in nonacademic language (Kirchner et al., 2014a; Ritchie et al., 2014). Subsequently, we developed an IF training manual to serve as source material for an IF training workshop and as a reference for those receiving ongoing IF mentoring (Ritchie et al., 2020). Because the IF strategy was developed, applied, and tested within the context of a clinical initiative (i.e., integrating mental health services into primary care settings), we were careful to use language in the manual that was nontechnical, straightforward, and appropriate for clinical practitioners rather than research terminology. To ensure its usefulness, IF experts reviewed drafts of the manual and provided feedback to inform revisions. Finally, we elicited and incorporated feedback from our national partners (the end-users of the training manual). Thus, the IF training manual's development was informed by research, theory, application, and stakeholders at multiple levels of the healthcare system. We revised the IF Training Manual in 2017 to reflect the current state of IF practice inside and outside VHA and informed by updated IF literature.

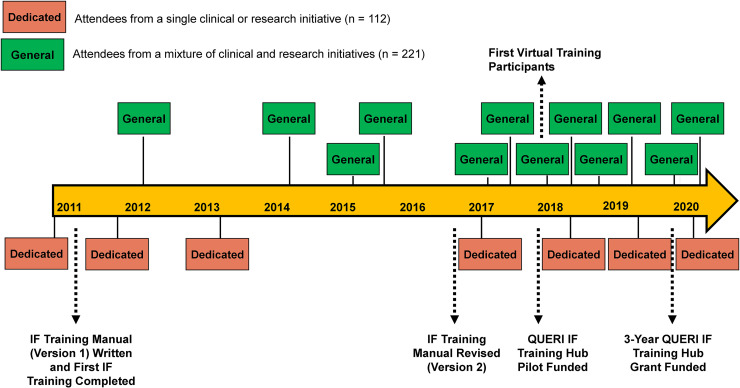

Following initial development, there was a substantial demand for training from clinical entities as well as from researchers both inside and outside of VHA (i.e., the Department of Defense and university-based researchers). To address this demand, we developed an ongoing IF training program to address IF training needs for specific high-priority VHA clinical initiatives. In addition to dedicated training focused on high priority initiatives, we conducted more “general” IF training comprised of clinical managers, researchers, and those wanting to train as implementation facilitators from a mixture of clinical and research initiatives. The average number of attendees for dedicated training was 16 and the average number of attendees for general training was 18 (see Figure 1). There was no formal marketing of the training program outside of communication from past participants of the training availability. In 2018, we trained our first group of participants using a hybrid virtual/in-person platform. One virtual site was limited to up to five participants associated with a single implementation initiative and paired with another group of in-person trainees, with in-person attendance limited to 15 participants. Subsequent training allowed an increase of up to 10 virtual participants while ensuring the total number in a training cohort did not exceed 25 (virtual and in-person combined).

Figure 1.

Development and delivery of implementation facilitation training program from 2011 to 2020.

Realizing the critical need for comprehensive transfer of implementation science knowledge, the national VHA QUERI program office released a competitive Call for Proposals to provide pilot funds to develop and evaluate Implementation Strategy Training Hubs. These pilot funds allowed our IF training program to engage with an education consultant for input on adult learning best practices and conduct and incorporate findings from an independent evaluation of the program (described below). In plate 2018, we applied for and received 3-year funding to become a formal QUERI Training Hub, focusing on IF.

Target Training Audience

Although we designed the content of the IF training program with the specific goal of training IFs, the target group was purposefully broad, reaching people from multiple professional disciplines (Proctor et al., 2013a). Training program participants included IFs, implementation initiative leaders, and researchers. We did not limit the number of initiatives that a single general IF Training Program addressed nor did we require participants to be working on the same initiative. However, the dedicated training were one exception (indicated in Figure 1), which focused on topics such as the implementation of team-based care in specialty mental health settings, integration of mental health services into primary care, and outcomes monitoring for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Continuing Education Credits

Since 2019, our training program has been approved for 14 h of Continuing Education Credit for the following disciplines: Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, American Nurses Credentialing Center, American College of Healthcare Executives, Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, Association of Social Work Boards, American Psychological Association, and National Board for Certified Counselors. See Figure 1 for a timeline of key events associated with the development of the IF training program.

Training Format

Training consisted of a two-day course comprised of a multifaceted curriculum of preparatory work, didactic sessions, interactive role-plays, and opportunities for ongoing mentorship. We typically provided training sessions quarterly based on training demand and faculty availability. Due to the depth and complexity of the training, we allowed participants to retake the course if they desired. Three IF experts, each with over 15 years of facilitation experience, served as faculty.

Prior to attending the training, we asked participants to review the IF Training Manual, develop a draft Implementation Planning Guide Template (Dollar et al., 2019) for their innovation, and watch a video, which included an overview of the i-PARIHS framework domains (innovation, context, and recipients), a description of IF, and a review of the literature supporting IF as an evidence-based implementation strategy. During the 2-day IF training, we reviewed information provided in the video through a reverse classroom experience in which participants described potential implementation barriers and facilitators in each of the i-PARIHS domains for their own projects.

Based on feedback following early training sessions, and consistent with prior research, we realized that interactive role plays and group exercises in applying IF skills were critical processes through which participants could practice what was taught during the didactic sessions (Forsetlund et al., 2009; Knowles et al., 2001; McWilliam, 2007; Steinert, 1993). Role plays are regularly used to teach participants new skills (Nestel & Tierney, 2007) and are increasingly being studied to understand their impact on learning. We provided a series of interactive roles play exercises throughout the IF training program, giving trainees opportunities to apply facilitation skills through scenarios based on common situations that program faculty had experienced when serving as facilitators. In these exercises, a trainee volunteered to interact with a member of the program faculty who acted out an experience they had with a stakeholder/recipient (playing the role of the stakeholder). The other program faculty engaged with the volunteer and other trainees to brainstorm ideas/suggestions for how to apply facilitation skills to effectively address the scenario.

While the formal training provided a baseline experience, the full acquisition of skills was accomplished through applying the knowledge learned in the training as a facilitator. These experiences presented challenging situations, even for expert facilitators. Thus, ongoing opportunities to present and discuss complex facilitation issues in real time were critical. Two resources provided participants an opportunity for feedback during their own facilitation activities. First, our IF faculty established monthly virtual office hours during which at least two of the faculty were available for consultation, and we emailed reminders of this opportunity 2 days prior to the monthly call. Participant attendance each month ranged from 3 to 10 (mean attendance 4). While this was a small average percentage monthly (2%), the training team felt it was important to be regularly available to past trainees for consultation during their implementation efforts. Secondly, we invited participants to attend our IF Learning Collaborative, which was established in 2014 as part of the overarching VHA Behavioral Health QUERI program. The IF Learning Collaborative met monthly and was composed of over 175 operational, programmatic, and clinical leaders as well as VHA and non-VHA researchers interested in applying and studying IF. The IF Learning Collaborative was led by creators and faculty from the IF Training Program and supported by a broader Leadership Team comprised of facilitation practitioners and researchers from VHA and non-VHA settings. The goal of the IF Learning Collaborative was to provide a platform for participants to share best practices in IF and work collaboratively to advance the science and practice of IF. It also provided opportunities for ongoing consultation from a broad collection of implementation facilitators and scientists. Subgroups of the IF Learning Collaborative have developed tools for standardized documentation of the dimensions of IF, recommendations for conducting IF in a virtual format, and identified core activities of IF (Dollar et al., 2020; Ritchie et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2019).

Learning Objectives

As part of the training program development process, we created learning objectives. Objectives of the training were to explain the key i-PARIHS domains involved in IF; compare and contrast the roles and activities of external facilitators, internal facilitators, site champions, and other stakeholders; identify activities in each phase of implementation (i.e., pre-implementation, implementation, sustainability); describe methods to overcome barriers or resistance to practice change; describe approaches to facilitate stakeholder engagement; explain the process for developing a local implementation plan, and describe best practices for virtual IF. The program content was designed to ensure learning objectives were achieved, and each section of the training mapped directly on to these objectives.

The training began with an overview of the i-PARIHS framework and evidence for IF (discussed in a reverse classroom experience, described above). This was followed by an interactive discussion to identify characteristics of an effective facilitator, with the goals of highlighting core facilitation competencies, distinctions between external/internal facilitators and clinical champions, and facilitation roles. The training then focused on activities and core competencies in the pre-implementation, implementation, and sustainability phases (described in Appendix A); best practices in applying virtual facilitation; and tools and processes for documenting IF activities. Table 1 provides an overview of the didactic sessions.

Table 1.

Overview of Didactic Sessions in 2-day IF Training Program.

| Sessions | Description |

|---|---|

| i-PARIHS framework & evidence for IF | Overview of the integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework, used to (a) help explain and predict why implementation is or is not successful; and (b) describe IF as the “active ingredient” for supporting implementation in i-PARIHS. |

| Core IF competencies | Explanation of the key competencies and abilities for those serving in IF roles. |

| Distinctions between external/internal facilitators & clinical champions | Comparison and contrast of these roles and responsibilities. |

| IF roles/activities in the pre-implementation phase | Focus on facilitator activities during this planning phase which is used to assess the site's needs, preferences, barriers, facilitators, and resources, leading to the creation of a tailored Implementation Plan. |

| IF roles/activities in the implementation phase | Focus on facilitator activities during the implementation phase including maintaining ongoing communication with site, reviewing implementation plan, monitoring progress and making modifications to the Implementation Plan, if necessary. |

| IF roles/activities in the sustainability phase | Focus on facilitator activities in this phase to empower sites to sustain the innovation by ensuring the innovation is fully integrated (institutionalized), has sound infrastructure, and has ongoing support from leadership. |

| Best practices in applying virtual facilitation | Description of best practices for applying IF through virtual platforms when meeting face-to-face is not an option; tips for optimizing virtual meetings and interactions. |

| Tools/processes for documenting IF activities | Focus on how to record and track IF activities in support of evaluating facilitator time/costs. |

Past Training and Attendees

From September 2011 to July 2020, the program trained a total of 333 participants, 276 face-to-face and 57 virtually within 19 individual training sessions. Of the 19 individual training sessions conducted, seven were dedicated to a single clinical or research initiative with an average attendance of 8.1 participants, and 12 general sessions with a mixture of clinical and/or research initiatives with an average attendance of 23.0 participants. Figure 2 provides a graphical illustration of the distribution of IF training participants across the country to date.

Figure 2.

Location of implementation facilitation training participants 2011–2020.

Evaluation

While we collected informal evaluation data since beginning the training in 2011 to continually identify and address areas for improvement, in 2017 we partnered with the VA South Central Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center to conduct an independent evaluation of our training program. The purpose of this evaluation was to (a) assess the training program's impact in terms of transferring knowledge of and confidence in applying IF skills, and (b) inform adaptations needed to the training program methods/content to meet learning objectives. Below, we describe the quantitative methods and analysis from this evaluation.

Evaluation Methods

From May 2017 to July 2019, 172 participants who attended 11 different types of training were asked to complete an electronic survey approximately 2 weeks before and 2 weeks and 6 months after each training (see Appendix B). Pre-training surveys collected participant demographic information (e.g., education, discipline) and assessed the following domains using rank items according to a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Not At All, 1 = Somewhat, 2 = Moderately, and 3 = Extremely): (a) familiarity with implementation science frameworks and strategies, and (b) knowledge of and confidence in applying IF skills in the following domains (consistent with IF training learning objectives): facilitating the adoption of clinical innovations; roles and activities of external and internal facilitators as well as site champions; activities for facilitators during pre-implementation, implementation, and sustainability phases; applying methods to overcome barriers; facilitating stakeholder engagement; developing local implementation plans; using virtual facilitation; and evaluating the IF strategy. The post-training survey re-evaluated the above domains and assessed participants’ perceptions of the training experience, including delivery of the material (e.g., level of interaction between participants and faculty) and logistics (e.g., meeting space and visuals). Because of the ordinal nature of the data and nonequidistance between categories, each question was evaluated separately and not as an aggregate score that we could potentially treat as continuous. We used nonparametric methods (Pett, 1997; Sullivan & Artino, 2013) (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests) to compare self-reported knowledge and confidence responses at baseline with values provided post-training and at 6 months. Using similar evaluation methods, we also compared self-reported knowledge and confidence assessments immediately post-training to those obtained at 6-months post-training.

Evaluation Results

One hundred and two participants completed the pre-training evaluation and either the post-training evaluation (n = 97, 95%) or the 6-month follow-up evaluation (n = 36, 35%). Thirty-one participants (31%) completed both post-training and 6-month evaluation. Seventy-six of the participants were trained in-person and 26 were trained virtually.

At baseline, the majority of participants (64%) reported having doctoral degrees. Our participants could serve multiple job duties (e.g., clinical and administrative roles). When asked about current job duties (which were nonexclusive categories), the majority (79%) reported research functions. Additional reported job duties included program evaluation (42%), education (42%), clinical responsibilities (37%), and administrative roles (32%). Prior to the training, 24% reported they were not at all familiar with implementation science frameworks, while 46% reported being somewhat familiar. Similarly, 27% reported being not at all familiar with the IF strategy, while 52% being somewhat familiar, 17% being moderately familiar, and only 5% being extremely familiar.

Post-training, 92% reported that the training met their expectations, and 97% reported they would be able to apply the knowledge gained. Indicating high satisfaction, over 98% reported that the materials were pertinent and useful, trainers were knowledgeable, participation was encouraged, and adequate time was allotted for content (Kirkpatrick, 1994, 1996). Wilcoxon signed-rank tests revealed a significant increase in participants’ perceived confidence and knowledge across all IF domains from pre-to-post training (Wilcoxon values and changes in each domain provided in Appendices C and D) and pre- to 6-month (see Tables 2 and 3); however, when comparing post-training perceptions to those at 6 months, we found that while increases in perceptions of knowledge remained unchanged, perceived confidence to apply facilitation skills in half (6/12) of the IF domains was shown to be significantly lower (p < .05) at 6 months than it was at post-training (Wilcoxon values and changes in each domain provided in Appendices E and F). These domains included facilitation activities in each of the three implementation phases, virtual facilitation, and overcoming barriers to change. When comparing pre-to-post changes in knowledge and confidence among the 26 trainees that participated virtually to those that participated in person, there were no significant differences at post-training nor at 6-month follow-up (p > .05).

Table 2.

IF Training Participant Self-Reported IF Strategy Domain Responses for Confidence From Pre-Training to 6-Months Post-Training.

| Confidence in IF domains (n = 36) | Event | Not at all n (%) | Somewhat n (%) | Moderately n (%) | Extremely n (%) | S (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors facilitating adoption of clinical innovations | Pre | 11 (31) | 16 (44) | 8 (22) | 1 (3) | 175.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 10 (28) | 18 (50) | 8 (22) | ||

| Role of activities of external facilitators | Pre | 12 (33) | 15 (42) | 7 (19) | 2 (6) | 198.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 2 (6) | 6 (17) | 16 (44) | 12 (33) | ||

| Role of activities of internal facilitators | Pre | 11 (31) | 17 (47) | 8 (22) | 0 (0) | 203.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 1 (3) | 9 (25) | 16 (44) | 10 (28) | ||

| Role and activities of site champions | Pre | 11 (31) | 16 (44) | 8 (22) | 0 (0) | 165.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 3 (8) | 9 (25) | 15 (42) | 9 (25) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the pre-implementation phase | Pre | 16 (44) | 12 (33) | 7 (19) | 1 (3) | 208.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 1 (3) | 8 (22) | 20 (56) | 7 (19) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the implementation phase | Pre | 15 (42) | 14 (39) | 6 (17) | 1 (3) | 189.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 2 (6) | 5 (14) | 22 (61) | 7 (19) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the sustainability phase | Pre | 19 (53) | 14 (39) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 232.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 2 (6) | 8 (22) | 22 (61) | 4 (11) | ||

| Virtual Implementation Facilitation | Pre | 22 (61) | 11 (31) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 203.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 4 (11) | 10 (28) | 18 (50) | 4 (11) | ||

| Methods to overcome barriers or resistance to practice change | Pre | 14 (39) | 15 (42) | 6 (17) | 1 (3) | 150.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 1 (3) | 12 (33) | 21 (58) | 2 (6) | ||

| Approaches to facilitate stakeholder engagement | Pre | 15 (42) | 14 (39) | 5 (14) | 2 (6) | 150.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 3 (8) | 8 (22) | 16 (44) | 9 (25) | ||

| Process for developing a local implementation plan | Pre | 13 (36) | 16 (44) | 7 (19) | 0 (0) | 162.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 1 (3) | 11 (31) | 17 (47) | 7 (19) | ||

| Evaluation of the implementation facilitation strategy | Pre | 12 (33) | 14 (39) | 8 (22) | 2 (6) | 151.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 2 (6) | 10 (28) | 19 (53) | 5 (14) |

Note: Number and percentage of responses regarding confidence per category for each implementation facilitation domain at pre- and 6-months post-training. Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistic (S) corresponds to the difference between the expected and the observed sum of signed ranks. P-value (p) is associated with Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Table 3.

IF Training Participant Self-Reported if Strategy Domain Responses for Knowledge From Pre-Training to 6-Months Post-Training.

| Knowledge in IF domains (n = 36) | Event | Not at all n (%) | Somewhat n (%) | Moderately n (%) | Extremely n (%) | S (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors facilitating adoption of clinical innovations | Pre | 4 (11) | 18 (50) | 12 (33) | 2 (6) | 105.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 7 (19) | 19 (53) | 10 (28) | ||

| Role of activities of external facilitators | Pre | 6 (17) | 18 (50) | 8 (22) | 4 (11) | 175.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 20 (56) | 14 (39) | ||

| Role of activities of internal facilitators | Pre | 6 (17) | 20 (56) | 9 (25) | 1 (3) | 217.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 22 (61) | 12 (33) | ||

| Role and activities of site champions | Pre | 3 (8) | 20 (56) | 13 (36) | 0 (0) | 171.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 5 (14) | 19 (53) | 12 (33) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the pre-implementation phase | Pre | 13 (36) | 17 (47) | 4 (11) | 1 (3) | 217.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 6 (17) | 19 (53) | 11 (31) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the implementation phase | Pre | 11 (31) | 20 (56) | 3 (8) | 2 (6) | 232.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 20 (56) | 12 (33) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the sustainability phase | Pre | 14 (39) | 18 (50) | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | 217.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 7 (19) | 22 (61) | 7 (19) | ||

| Virtual implementation facilitation | Pre | 22 (61) | 12 (33) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 265.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 9 (25) | 19 (53) | 8 (22) | ||

| Methods to overcome barriers or resistance to practice change | Pre | 8 (22) | 22 (61) | 5 (14) | 1 (3) | 189.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 8 (22) | 22 (61) | 6 (17) | ||

| Approaches to facilitate stakeholder engagement | Pre | 8 (22) | 20 (56) | 5 (14) | 3 (8) | 136.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 10 (28) | 17 (47) | 9 (25) | ||

| Process for developing a local implementation plan | Pre | 8 (22) | 22 (61) | 6 (17) | 0 (0) | 189.0 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 5 (14) | 24 (67) | 7 (19) | ||

| Evaluation of the implementation facilitation strategy | Pre | 11 (31) | 16 (44) | 8 (22) | 1 (3) | 162.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 9 (25) | 20 (56) | 7 (19) |

Note: Number and percentage of responses regarding knowledge per category for each implementation facilitation domain at pre- and post-training. Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistic (S) corresponds to the difference between the expected and the observed sum of signed ranks. P-value (p) is associated with Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Discussion

To answer the call for formal research training in implementation science, several universities (Gonzales et al., 2012) and funder-initiated (Jacob et al., 2020; Proctor et al., 2013b; Straus et al., 2011; Tabak et al., 2017) training programs were developed. We now face the challenge of educating our healthcare leaders, frontline providers, and implementation practitioners in implementation skills. A report of findings from a meeting on dissemination and training needs noted that few U.S.-based training programs focus on implementation practitioners or policymakers (Proctor & Chambers, 2016). We addressed this gap by the development, implementation, and evaluation of a highly partnered training program that meets healthcare leaders’ needs within a single large healthcare system (VHA) (Ritchie et al., 2014). However, it has developed into a robust program that continues to train IF practitioners, clinical and operational partners, and researchers inside and outside of the healthcare system for which it was originally developed.

Evaluation findings of the IF training program administered immediately before and after the training show that participants reported increased knowledge of and confidence in all targeted learning objectives, which were sustained 6 months post-training. Comparisons of knowledge and confidence change scores for virtual versus in-person participation show no significant differences, suggesting that there was no loss of knowledge/skill transfer when providing IF training on virtual platforms. While this is encouraging, virtual participation was limited to one site per training, highlighting a need to expand our capability to deliver training virtually and involve multiple sites simultaneously.

When comparing perceived facilitation knowledge immediately following the IF training to 6-month surveys, there were no significant differences in perceived knowledge provided in the IF training. Yet, we did see a significant decrease in confidence to apply half of these skills. While we enhanced participants’ access to consultation through office hours and the IF Learning Collaborative, these changes occurred during the time of data collection, so some 6-month survey respondents may have not utilized these resources. Data collection methods did not allow us to link attendance at office hours to 6-month survey responses, so we are unable to assess the support's influence. Further, we did not collect data on whether trainees had applied an IF strategy during the 6 months post-training, so some trainees may have lost confidence in their IF skills if they hadn't applied what they learned. For 6-month respondents who may have applied an IF strategy during the months following training, the early phases of implementing a new clinical initiative can be some of the most challenging. More studies are needed to address the transfer and retention of knowledge and skills during the implementation of a clinical initiative.

The spread of quality improvement and implementation strategies are not without challenges. Pandhi et al. (2019) faced several challenges when spreading a program to engage patients in quality improvement activities, with an inability to recruit participants primary among the challenges identified. Reasons for lack of participation included competing priorities, leadership changes, and overburdened providers and staff. Our training program has not encountered similar recruitment challenges, possibly because it was developed as a highly partnered program within a single healthcare system, VHA, meeting the needs of that system (Kirchner et al., 2014a). Thus, the IF training program was able to engage a large, established market base for the training from its inception. Subsequently, rather than initiating a formal marketing campaign, we have been able to rely on unsolicited demand for the training through informal channels (e.g., referrals by past trainees). We have also made subtle adaptations to the content and interactive exercises within the training to enhance its relevance to healthcare settings other than the initial healthcare system partner (VHA).

Pandhi et al. also identified a need for ongoing coaching to ensure uptake of the QI process (Pandhi et al., 2019). This is consistent with findings from the FIRE Study (Harvey et al., 2018; Seers et al., 2012) in which there were no significant differences in clinical guideline compliance between sites receiving one of two types of facilitation support compared to those receiving no facilitation. In a subsequent exploration of factors that contributed to the difficulty of implementing the clinical guideline, Harvey et al. (2018) also noted the need for ongoing support and mentoring for inexperienced facilitators. While our IF training program does not address a specific guideline implementation effort, on feedback forms our trainees noted the need for ongoing support to sustain their IF knowledge and skills. In response to this need, we established the monthly “Office Hours” calls available to all past trainees and encouraged them to engage with our IF Learning Collaborative. The degree to which these added elements of mentoring and support were sufficient or if, as suggested by FIRE investigators (Seers et al., 2012), role modeling at the local level may be necessary for uptake of facilitation skills, is unknown since our evaluation did not incorporate assessment of results from individual implementation projects as an outcome.

To further enhance the transfer of successful IF strategies from research to practice, there is also a need to develop tools to monitor the fidelity with which the IF strategy is applied following training. Through a scoping literature review and rigorous expert panel consensus, we identified a set of core IF activities that may be focused upon for IF fidelity monitoring (Smith et al., 2019). Based on these core activities, we developed prototype IF fidelity tools (Ritchie et al., 2017), which are currently in pilot testing. Once tested and refined, these IF fidelity tools will serve as another assessment to incorporate into our training program evaluation, and an additional resource that trainees may use to monitor and improve their fidelity to the IF strategy.

Limitations

While findings from the evaluation of our IF training program are promising, there are limitations. There are inherent limitations in the use of the self-report Likert-type surveys for detecting meaningful change. Future IF training evaluations should consider additional, validated objective measures. However, to date, there are no known validated, objective instruments for the evaluation of IFs’ knowledge and skills. Additional work to develop these tools is needed and currently in progress.

Although the 6-month survey response rate was low (35%) it is consistent with reported survey response rates when no incentive is provided (Van Mol, 2017). Yet, this may indicate a potential for selection bias if those most engaged in facilitation and applying the knowledge/skills gained at 6 months were those who differentially responded to the survey. Though this possibility may explain higher self-reported ratings of perceived IF knowledge/skills at 6 months, it would not explain the significant pre/post improvements in these scores immediately before and after receiving the training at baseline. If the possible response bias at 6 months was present, 6 month results may be a representation of outcomes among the most appropriate training candidates (i.e., those with a strong interest in IF with plans for applying the strategy). While the broad number of roles identified by the attendees indicated the breadth of participants’ jobs, the lack of designation of a primary role associated with training attendance decreased the ability to fully characterize the cohort at baseline or at 6-month follow-up.

Future Directions

As indicated by the limitations of the current evaluation, there are clear future directions for this work, focusing on three key areas: (1) incorporating education evaluation models, (2) addressing issues identified during our current evaluation, and (3) continuing expansion and enhancement of the training program.

Full evaluation of implementation practitioner training programs should incorporate rigorous education evaluation models, such as the one proposed by Kirkpatrick (1994, 1996). The Kirkpatrick model includes four levels of evaluation criteria. Level 1 measures the participants’ reaction to the training (e.g., satisfaction), which we were able to document in the currently limited evaluation described in this manuscript. Level 2 of the Kirkpatrick model, learning, analyzes whether participants understood the training reflected by an increase in knowledge, skills, and experiences. The IF training program evaluation only allows us to assess trainees’ perceived knowledge of and confidence in applying IF strategies. Future evaluations should expand this to incorporate questions of training content as well as the degree to which the knowledge gained in the IF training program was applied in an implementation effort. Level 3 of the Kirkpatrick model documents whether the participants utilize what they have learned in the training. We are currently developing an IF fidelity metric that can be used to assess how well trainees actually apply the strategy following training. The final level of the Kirkpatrick model is results and leads us to the ultimate question; did the IF training program have a significant contribution to a successful implementation of an innovation? This will be answered in future evaluations by documenting outcomes of specific innovation implementation efforts by our trainees.

Future evaluation of our training program also presents an opportunity to evaluate training adaptation and expanded virtual training formats and components targeting improved confidence in applying IF. Future work should seek to increase the number of virtual sites/attendees and develop processes to enhance interactive elements of the training through virtual platforms. As we begin to accommodate more participants in additional training cohorts, we will be better able to determine the ideal number of participants to have in a training cohort and how participant discipline, type of innovation under study, and attendance as a team supporting a single innovation versus as an individual impact perceived knowledge and skill acquisition. Finally, it is critical to identify factors associated with loss of perceived confidence applying implementation skills over time. Once identified, future efforts should evaluate the impact of new and/or expanded mechanisms/resources for keeping trainees engaged with faculty for ongoing consultation and mentoring following training.

We also identified modifications to the program format that could increase reach. Our training program has a reverse classroom experience in which the participants view pre-recorded content that is discussed during the actual training. Additional components of the training content could be converted to this type of format as a way for engagement in self-directed learning, allowing for briefer discussion during the actual training sessions and decreasing the training length. This format could be modified to an adaptive training program in which those who want an overview of IF could access information virtually and independently, allowing the actual IF training to be provided to those who anticipate serving as IF practitioners.

Finally, it is important to note that the IF training program was developed within settings that are well resourced compared to those less resourced (e.g., low- and middle-income countries), and barriers to implementation may differ (Ayoubian et al., 2020). To address the application of IF in these settings, additional emphasis on political and structural formative evaluation thorough documentation of recipient characteristics, and further potential adaptations of the innovation should be expanded in the IF training content.

Conclusions

Findings indicate that we have promising but preliminary results supporting our development and implementation of an effective IF training program. Trainees reported high levels of satisfaction with the program, perceived improvements in both knowledge of and confidence in applying IF skills, and, encouragingly, sustained perceived knowledge post-training. The ability to successfully apply implementation strategies is critical to develop a cadre of implementation practitioners poised to improve the implementation of EBPs and other clinical innovations. It is only through a well-trained workforce that we can apply implementation strategies to enhance the quality of care provided. Additional investigation through qualitative reports of the training experience and long-term outcomes are critical, as is the continued use of an iterative formative evaluation as the training continues to be adapted, refined, and improved upon based on participant feedback. Future studies will determine the degree to which this and other implementation strategy training programs ultimately enhance the uptake of diverse EBPs, building a pathway toward the future implementation of new and exciting healthcare innovations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lindsay Martin for her participation in the evaluation and assistance to improve the program, Dr. Samantha Connolly for providing her careful evaluation and critique, Barbara Johnson for lending her technical expertise in creating the figures for this manuscript, and Dr. Mona Ritchie for sharing her wisdom and providing guidance through the submission process.

Appendices

Appendix A

Table A1.

Three Phases of Implementation.

| Pre-implementation phase: This phase typically involves a facilitator’s initial engagement with site stakeholders over a period of weeks or months to gain a better understanding of their resources, priorities, and context, with the primary objective of assisting in the development of an implementation plan. |

| Implementation phase: Once the implementation plan has been developed, the implementation phase typically starts with a kick-off meeting where the implementation plan is carried out with ongoing, relatively frequent contact by the facilitator to monitor and support the plan’s execution and refinement. |

| Sustainment phase: During this phase, contact between site stakeholders is less frequent and eventually non-existent, with the objective being to turn a mature (hopefully successful) implementation effort over to the site with minimal further interaction with the facilitator. |

Appendix B

Table B1.

IF Training Survey; Confidence and Knowledge Items.

| Please rate your knowledge about the following: 0 = Not at all, 1 = Somewhat, 2 = Moderately, 3 = Extremely |

| Factors facilitating adoption of clinical innovations |

| Role and activities of external facilitators |

| Role and activities of internal facilitators |

| Role and activities of site champions |

| Activities for facilitators during the pre-implementation phase |

| Activities for facilitators during the implementation phase |

| Activities for facilitators during the sustainability phase |

| Virtual implementation facilitation |

| Methods to overcome barriers or resistance to practice change |

| Approaches to facilitate stakeholder engagement |

| Process for developing a local implementation plan |

| Evaluation of the implementation facilitation strategy |

| Please rate your confidence in your ability to apply each of the following in your setting: 0 = Not at all, 1 = Somewhat, 2 = Moderately, 3 = Extremely |

| Factors facilitating adoption of clinical innovations |

| Role and activities of external facilitators |

| Role and activities of internal facilitators |

| Role and activities of site champions |

| Activities for facilitators during the pre-implementation phase |

| Activities for facilitators during the implementation phase |

| Activities for facilitators during the sustainability phase |

| Virtual implementation facilitation |

| Methods to overcome barriers or resistance to practice change |

| Approaches to facilitate stakeholder engagement |

| Process for developing a local implementation plan |

| Evaluation of the implementation facilitation strategy |

Appendix C

Table C1.

IF Training Participant Self-Reported IF Strategy Domain Responses for Knowledge From Pre-Training to Post-Training.

| Knowledge in IF domains (n = 97) | Event | Not at all n (%) | Somewhat n (%) | Moderately n (%) | Extremely n (%) | S (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors facilitating adoption of clinical innovations | Pre | 20 (21) | 44 (45) | 29 (30) | 4 (4) | 1221.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 7 (7) | 64 (66) | 26 (27) | ||

| Role of activities of external facilitators | Pre | 23 (24) | 45 (46) | 24 (25) | 5 (5) | 1563.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 50 (52) | 45 (46) | ||

| Role of activities of internal facilitators | Pre | 23 (24) | 45 (46) | 26 (27) | 2 (2) | 1468.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 7 (7) | 53 (55) | 37 (38) | ||

| Role and activities of site champions | Pre | 14 (14) | 47 (48) | 35 (36) | 1 (1) | 1366.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 58 (60) | 35 (36) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the pre-implementation phase | Pre | 40 (41) | 37 (38) | 16 (16) | 3 (3) | 1914.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 52 (54) | 43 (44) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the implementation phase | Pre | 35 (36) | 42 (43) | 16 (16) | 4 (4) | 1809.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 58 (60) | 36 (37) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the sustainability phase | Pre | 42 (43) | 38 (39) | 17 (18) | 0 (0) | 1768.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 10 (10) | 58 (60) | 29 (30) | ||

| Virtual implementation facilitation | Pre | 54 (56) | 32 (33) | 9 (9) | 2 (2) | 1888.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 1 (1) | 14 (14) | 50 (52) | 32 (33) | ||

| Methods to overcome barriers or resistance to practice change | Pre | 26 (27) | 51 (53) | 18 (19) | 2 (2) | 1636.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 12 (12) | 57 (59) | 28 (29) | ||

| Approaches to facilitate stakeholder engagement | Pre | 29 (30) | 45 (46) | 19 (20) | 4 (4) | 1681.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 9 (9) | 52 (54) | 36 (37) | ||

| Process for developing a local implementation plan | Pre | 33 (34) | 41 (42) | 21 (22) | 2 (2) | 1743.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 13 (13) | 51 (53) | 33 (34) | ||

| Evaluation of the implementation facilitation strategy | Pre | 29 (30) | 42 (43) | 22 (23) | 4 (4) | 1118.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 2 (2) | 19 (20) | 51 (53) | 25 (26) |

Number and percentage of responses per category regarding knowledge for each implementation facilitation domain at pre- and post-training. Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistic (S) corresponds to the difference between the expected and the observed sum of signed ranks. P-value (p) is associated with Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Appendix D

Table D1.

IF Training Participant Self-Reported IF Strategy Domain Responses for Confidence From Pre-Training to Post-Training.

| Confidence in IF domains (n = 97) | Event | Not at all n (%) | Somewhat n (%) | Moderately n (%) | Extremely n (%) | S (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors facilitating adoption of clinical innovations | Pre | 33 (34) | 41 (42) | 20 (21) | 3 (3) | 1532.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 18 (19) | 55 (57) | 24 (25) | ||

| Role of activities of external facilitators | Pre | 36 (37) | 36 (37) | 20 (21) | 5 (5) | 1677.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 17 (18) | 41 (42) | 39 (40) | ||

| Role of activities of internal facilitators | Pre | 36 (37) | 37 (38) | 22 (23) | 2 (2) | 1572.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 19 (20) | 49 (51) | 29 (30) | ||

| Role and activities of site champions | Pre | 28 (29) | 42 (43) | 24 (25) | 2 (2) | 1435.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 17 (18) | 52 (54) | 28 (29) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the pre-implementation phase | Pre | 41 (42) | 34 (35) | 18 (19) | 4 (4) | 1801.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 12 (12) | 53 (55) | 32 (33) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the implementation phase | Pre | 41 (42) | 34 (35) | 17 (18) | 5 (5) | 1751.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 16 (16) | 49 (51) | 32 (33) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the sustainability phase | Pre | 47 (48) | 34 (35) | 15 (15) | 1 (1) | 1780.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 20 (21) | 52 (54) | 25 (26) | ||

| Virtual implementation facilitation | Pre | 53 (55) | 28 (29) | 12 (12) | 4 (4) | 1627.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 2 (2) | 22 (23) | 51 (53) | 22 (23) | ||

| Methods to overcome barriers or resistance to practice change | Pre | 30 (31) | 41 (42) | 21 (22) | 3 (3) | 1261.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 1 (1) | 26 (27) | 50 (52) | 20 (21) | ||

| Approaches to facilitate stakeholder engagement | Pre | 32 (33) | 43 (44) | 16 (16) | 6 (6) | 1470.0 (<.001) |

| Post | 1 (1) | 17 (18) | 55 (57) | 24 (25) | ||

| Process for developing a local implementation plan | Pre | 35 (36) | 40 (41) | 18 (19) | 4 (4) | 1585.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 0 (0) | 20 (21) | 52 (54) | 25 (26) | ||

| Evaluation of the implementation facilitation strategy | Pre | 31 (32) | 38 (39) | 23 (24) | 5 (5) | 1135.5 (<.001) |

| Post | 4 (4) | 19 (20) | 54 (56) | 19 (20) |

Number and percentage of responses regarding confidence per category for each implementation facilitation domain at pre- and post-training. Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistic (S) corresponds to the difference between the expected and the observed sum of signed ranks. P-value (p) is associated with Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Appendix E

Table E1.

IF Training Participant Self-Reported IF Strategy Domain Responses for Knowledge From Post-Training to 6 Months Post-Training.

| Knowledge in IF domains (n = 31) | Event | Not at all n (%) | Somewhat n (%) | Moderately n (%) | Extremely n (%) | S (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors facilitating adoption of clinical innovations | Post | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 23 (74) | 7 (23) | −6.0 (.45) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 5 (16) | 18 (58) | 8 (26) | ||

| Role of activities of external facilitators | Post | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 13 (42) | 17 (55) | −13.5 (.07) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 17 (55) | 12 (39) | ||

| Role of activities of internal facilitators | Post | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 20 (65) | 9 (29) | 3.0 (1.00) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 19 (61) | 10 (32) | ||

| Role and activities of site champions | Post | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 22 (71) | 8 (26) | −3.0 (1.00) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 4 (13) | 17 (55) | 10 (32) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the pre-implementation phase | Post | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 (58) | 13 (42) | −22.0 (.06) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 5 (16) | 16 (52) | 10 (32) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the implementation phase | Post | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20 (65) | 11 (35) | −13.0 (.38) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 18 (58) | 10 (32) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the sustainability phase | Post | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 23 (74) | 8 (26) | −24.5 (.09) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 6 (19) | 18 (58) | 7 (23) | ||

| Virtual implementation facilitation | Post | 0 (0) | 6 (19) | 17 (55) | 8 (26) | −10.5 (.63) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 7 (23) | 18 (58) | 6 (19) | ||

| Methods to overcome barriers or resistance to practice change | Post | 0 (0) | 6 (19) | 19 (61) | 6 (19) | −2.5 (.63) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 7 (23) | 19 (61) | 5 (16) | ||

| Approaches to facilitate stakeholder engagement | Post | 0 (0) | 5 (16) | 17 (55) | 9 (29) | −10.0 (.23) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 8 (26) | 16 (52) | 7 (23) | ||

| Process for developing a local implementation plan | Post | 0 (0) | 5 (16) | 18 (58) | 8 (26) | −2.5 (1.00) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 23 (74) | 5 (16) | ||

| Evaluation of the implementation facilitation strategy | Post | 0 (0) | 6 (19) | 20 (65) | 5 (16) | −2.5 (1.00) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 8 (26) | 17 (55) | 6 (19) |

Number and percentage of responses per category regarding knowledge for each implementation facilitation domain at post- and 6 months post-training. Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistic (S) corresponds to the difference between the expected and the observed sum of signed ranks. P-value (p) is associated with Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Appendix F

Table F1.

IF Training Participant Self-Reported IF Strategy Domain Responses for Confidence From Post-Training to 6 Months Post-Training.

| Confidence in IF domains (n = 31) | Event | Not at all n (%) | Somewhat n (%) | Moderately n (%) | Extremely n (%) | S (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors facilitating adoption of clinical innovations | Post | 0 (0) | 4 (13) | 18 (58) | 9 (29) | −25.5 (.27) |

| 6 months | 0 (0) | 8 (26) | 16 (52) | 7 (23) | ||

| Role of activities of external facilitators | Post | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 13 (42) | 15 (48) | −32.5 (.02) |

| 6 months | 2 (6) | 5 (16) | 13 (42) | 11 (35) | ||

| Role of activities of internal facilitators | Post | 0 (0) | 6 (19) | 17 (55) | 8 (26) | −9.0 (.61) |

| 6 months | 1 (3) | 8 (26) | 13 (42) | 9 (29) | ||

| Role and activities of site champions | Post | 0 (0) | 5 (16) | 18 (58) | 8 (26) | −30.0 (.10) |

| 6 months | 3 (10) | 7 (23) | 13 (42) | 8 (26) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the pre-implementation phase | Post | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 18 (58) | 11 (35) | −45.0 (.01) |

| 6 months | 1 (3) | 7 (23) | 17 (55) | 6 (19) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the implementation phase | Post | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 16 (52) | 12 (39) | −55.0 (.02) |

| 6 months | 2 (6) | 4 (13) | 19 (61) | 6 (19) | ||

| Activities for facilitators during the sustainability phase | Post | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 18 (58) | 10 (32) | −59.5 (<.001) |

| 6 months | 2 (6) | 6 (19) | 20 (65) | 3 (10) | ||

| Virtual implementation facilitation | Post | 1 (3) | 7 (23) | 16 (52) | 7 (23) | −38.5 (.01) |

| 6 months | 4 (13) | 8 (26) | 16 (52) | 3 (10) | ||

| Methods to overcome barriers or resistance to practice change | Post | 0 (0) | 7 (23) | 19 (61) | 5 (16) | −26.0 (.04) |

| 6 months | 1 (3) | 10 (32) | 18 (58) | 2 (6) | ||

| Approaches to facilitate stakeholder engagement | Post | 0 (0) | 5 (16) | 19 (61) | 7 (23) | −25.5 (.21) |

| 6 months | 3 (10) | 5 (16) | 16 (52) | 7 (23) | ||

| Process for developing a local implementation plan | Post | 0 (0) | 4 (13) | 20 (65) | 7 (23) | −28.0 (.12) |

| 6 months | 1 (3) | 8 (26) | 16 (52) | 6 (19) | ||

| Evaluation of the implementation facilitation strategy | Post | 0 (0) | 5 (16) | 21 (68) | 5 (16) | −22.5 (.24) |

| 6 months | 2 (6) | 7 (23) | 17 (55) | 5 (16) |

Number and percentage of responses per category regarding confidence for each implementation facilitation domain at post- and 6 months post-training. Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistic (S) corresponds to the difference between the expected and the observed sum of signed ranks. P-value (p) is associated with Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This study was supported by funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), QUE 15-289, QIS 18-200, and South Central Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center (A Virtual Center) Houston, TX, USA. The funding bodies had no involvement in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in writing the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- Ayieko P., Ntoburi S., Wagai J., Opondo C., Opiyo N., Migiro S., Wamae A., Mogoa W., Were F., Wasunna A., Fegan G., Irimu G., English M. (2011). A multifaceted intervention to implement guidelines and improve admission pediatric care in Kenyan district hospitals: A cluster randomized trial. PLOS Medicine, 8(4), e1001018. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoubian A., Nasiripour A. A., Tabibi S. J., Bahadori M. (2020). Evaluation of facilitators and barriers to implementing evidence-based practice in the health services: A systematic review. Galen Medical Journal, 9, e1645. 10.31661/gmj.v9i0.1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskerville N. B., Liddy C., Hogg W. (2012). Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Annals of Family Medicine, 10(1), 63–74. 10.1370/afm.1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskerville N., Hogg W., Lemelin J. (2001). Process evaluation of a tailored multifaceted approach to changing family physician practice patterns and improving preventive care. The Journal of Family Practice, 50(3), W242–W249. https://www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/60489/process-evaluation-tailored-multifaceted-approach-changing-family [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M. S., Kirchner J. (2020). Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Research, 283, 112376. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M. S., Miller C., Kim B., Lew R., Weaver K., Coldwell C., Henderson K., Holmes S., Seibert M. N., Stolzmann K., Elwy A. R., Kirchner J. (2015). Partnering with health system operations leadership to develop a controlled implementation trial. Implementation Science, 11(1), 22. 10.1186/s13012-016-0385-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson R. C., Colditz G. A., & Proctor E. K. (2017). Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice, 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oso/9780190683214.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers D., Pintello D., Juliano-Bult D. (2020). Capacity-building and training opportunities for implementation science in mental health. Psychiatry Research, 283, 112511. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheater F. M., Hearnshaw H., Baker R., Keane M. (2005). Can a facilitated programme promote effective multidisciplinary audit in secondary care teams? An exploratory trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42(7), 779–791. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran G. M., Mukherjee S., Allee E., Owen R. R. (2008). A process for developing an implementation intervention: QUERI Series. Implementation Science, 3(1), 17. 10.1186/1748-5908-3-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson W. P., Dickinson L. M., Nutting P. A., Emsermann C. B., Tutt B., Crabtree B. F., Fisher L., Harbrecht M., Gottsman A., West D. R. (2014). Practice facilitation to improve diabetes care in primary care: A report from the EPIC randomized clinical trial. Annals of Family Medicine, 12(1), 8–16. 10.1370/afm.1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollar K. M., Kirchner J. E., DePhilippis D., Ritchie M. J., McGee-Vincent P., Burden J. L., Resnick S. G. (2019). Steps for implementing measurement-based care: Implementation planning guide development and use in quality improvement. Psychological Services, 17(3), 247–261. 10.1037/ser0000368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollar K. M., Woodward E. N., Smith J. (2020, April). Updated Virtual Facilitation Guidance: Innovation, Challenges and Opportunities. Invited cyberseminar presentation to the VA QUERI Implementation Research Group.

- Eccles M. P., Mittman B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1(1), 1. 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie E. B., Shortell S. M. (2001). Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: A framework for change. The Milbank Quarterly, 79(2), 281–315. 10.1111/1468-0009.00206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsetlund L., Bjørndal A., Rashidian A., Jamtvedt G., O’Brien M., Wolf F., Davis D., Odgaard-Jensen J., & Oxman A. (2009). Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2009(2), CD003030. 10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales R., Handley M. A., Ackerman S., O’sullivan P. S. (2012). A framework for training health professionals in implementation and dissemination science. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 87(3), 271—278. 10.1097/acm.0b013e3182449d33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Robert G., Macfarlane F., Bate P., Kyriakidou O. (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 581–629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey G., Kitson A. (2015). Translating evidence into healthcare policy and practice: Single versus multi-faceted implementation strategies—Is there a simple answer to a complex question? International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 4(3), 123–126. PubMed. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey G., Loftus-Hills A., Rycroft-Malone J., Titchen A., Kitson A., McCormack B., Seers K. (2002). Getting evidence into practice: The role and function of facilitation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(6), 577–588. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02126.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey G., McCormack B., Kitson A., Lynch E., Titchen A. (2018). Designing and implementing two facilitation interventions within the ‘Facilitating Implementation of Research Evidence (FIRE)’ study: A qualitative analysis from an external facilitators’ perspective. Implementation Science, 13(1), 141. 10.1186/s13012-018-0812-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich P. A., Sahay A., Mittman B. S., Oliva N., Gholami P., Rumsfeld J. S., Massie B. M. (2015). Facilitation of a multihospital community of practice to increase enrollment in the hospital to home national quality improvement initiative. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 41(8), 361–369. 10.1016/s1553-7250(15)41047-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J. (1977). Dimensions of Facilitator Style / John Heron. Human Potential Research Project, University of Surrey.

- Jacob R. R., Gacad A., Padek M., Colditz G. A., Emmons K. M., Kerner J. F., Chambers D. A., Brownson R. C. (2020). Mentored training and its association with dissemination and implementation research output: A quasi-experimental evaluation. Implementation Science, 15(1), 30. 10.1186/s13012-020-00994-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne A. M., Almirall D., Eisenberg D., Waxmonsky J., Goodrich D. E., Fortney J. C., Kirchner J. E., Solberg L. I., Main D., Bauer M. S., Kyle J., Murphy S. A., Nord K. M., Thomas M. R. (2014). Protocol: Adaptive implementation of effective programs trial (ADEPT): Cluster randomized SMART trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation strategy to improve outcomes of a mood disorders program. Implementation Science: IS, 9, 132. 10.1186/s13012-014-0132-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne A. M., Goodrich D. E., Miake-Lye I., Braganza M. Z., Bowersox N. W. (2019). Quality enhancement research initiative implementation roadmap: Toward sustainability of evidence-based practices in a learning health system. Medical Care, 57(10 Suppl 3), S286–S293. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne A. M., Schulberg H. C., Post E. P., Rollman B. L., Belnap B. H., Pincus H. A. (2004). Translating evidence-based depression management services to community-based primary care practices. The Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 631–659. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00326.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner J. E., Kearney L. K., Ritchie M. J., Dollar K. M., Swensen A. B., Schohn M. (2014a). Research & services partnerships: Lessons learned through a national partnership between clinical leaders and researchers. Psychiatric Services, 65(5), 577–579. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner J. E., Ritchie M. J., Pitcock J. A., Parker L. E., Curran G. M., Fortney J. C. (2014b). Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29 Suppl 4, 904–912. 10.1007/s11606-014-3027-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner J. E., Woodward E. N., Smith J. L., Curran G. M., Kilbourne A. M., Owen R. R., Bauer M. S. (2016). Implementation science supports core clinical competencies: An overview and clinical example. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 18(6). 10.4088/PCC.16m02004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick D. (1994). Evaluating training programs: The four levels. Berrett-Koehler. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick D. (1996). Revisiting Kirkpatrick’s four-level-model. Training & Development, 1, 54–57. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A18063280/AONE?u=anon~406d5073&sid=googleScholar&xid=3ff222f8 [Google Scholar]

- Knowles C., Kinchington F., Erwin J., Peters B. (2001). A randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of combining video role play with traditional methods of delivering undergraduate medical education. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 77(5), 376. 10.1136/sti.77.5.376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay J. A., Kauth M. R., Hudson S., Martin L. A., Ramsey D. J., Daily L., Rader J. (2015). Implementation of video telehealth to improve access to evidence-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Telemedicine and E-Health, 21(6), 467–472. 10.1089/tmj.2014.0114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam C. L. (2007). Continuing education at the cutting edge: Promoting transformative knowledge translation. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 27(2), 72–79. 10.1002/chp.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignogna J., Hundt N. E., Kauth M. R., Kunik M. E., Sorocco K. H., Naik A. D., Stanley M. A., York K. M., Cully J. A. (2014). Implementing brief cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care: A pilot study. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4(2), 175–183. 10.1007/s13142-013-0248-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagykaldi Z., Mold J. W., Aspy C. B. (2005). Practice facilitators: A review of the literature. Family Medicine, 37(8), 581–588. https://www.stfm.org/familymedicine/vol37issue8/Nagykaldi581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestel D., Tierney T. (2007). Role-play for medical students learning about communication: Guidelines for maximizing benefits. BMC Medical Education, 7, 3. PubMed. 10.1186/1472-6920-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutting P. A., Miller W. L., Crabtree B. F., Jaen C. R., Stewart E. E., Stange K. C. (2009). Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Annals of Family Medicine, 7(3), 254–260. 10.1370/afm.1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandhi N., Jacobson N., Crowder M., Quanbeck A., Hass M., Davis S. (2019). Engaging patients in primary care quality improvement initiatives: Facilitators and barriers. American Journal of Medical Quality, 35(1), 52–62. 10.1177/1062860619842938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker L. E., de Pillis E., Altschuler A., Rubenstein L. V., Meredith L. S. (2007). Balancing participation and expertise: A comparison of locally and centrally managed health care quality improvement within primary care practices. Qualitative Health Research, 17(9), 1268–1279. 10.1177/1049732307307447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker L. E., Kirchner J. E., Bonner L. M., Fickel J. J., Ritchie M. J., Simons C. E., Yano E. M. (2009). Creating a quality-improvement dialogue: Utilizing knowledge from frontline staff, managers, and experts to foster health care quality improvement. Qualitative Health Research, 19(2), 229–242. 10.1177/1049732308329481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pett M. (1997). Nonparametric statistics for health care research: Statistics for small samples and unusual distributions. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Powell B. J., Waltz T. J., Chinman M. J., Damschroder L. J., Smith J. L., Matthieu M. M., Proctor E. K., Kirchner J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1), 21. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E. K., Chambers D. A. (2016). Training in dissemination and implementation research: A field-wide perspective. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 7(3), 624–635. 10.1007/s13142-016-0406-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E. K., Landsverk J., Baumann A. A., Mittman B. S., Aarons G. A., Brownson R. C., Glisson C., Chambers D. (2013a). The implementation research institute: Training mental health implementation researchers in the United States. Implementation Science, 8(1), 105. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E. K., Powell B. J., McMillen J. C. (2013b). Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Science, 8(1), 139. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Luke D., Calhoun A., McMillen C., Brownson R., McCrary S., Padek M. (2015). Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: Research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implementation Science, 10(1), 88. 10.1186/s13012-015-0274-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]