Abstract

Background

Integrated care programs that systematically and comprehensively address both behavioral and physical health may improve patient outcomes. However, there are few examples of such programs in addiction treatment settings. This article is a practical implementation report describing the implementation of an integrated care program into two opioid treatment programs (OTPs).

Method

Strategies used to implement integrated care into two OTPs included external facilitation, quality improvement (QI) processes, staff training, and an integrated organizational structure. Service, implementation, and client outcomes were examined using qualitative interviews with program staff (n = 16), program enrollment data, and client outcome data (n = 593) on mental health (MH), physical health, and functional indicators.

Results

Staff found the program to generally be acceptable and appropriate, but also noted that the new services added to already busy workflows and more staffing were needed to fully reach the program's potential. The program had a high level of penetration (∼60%–70%), enrolling over 1,200 clients. Staff noted difficulties in connecting clients with some services. Client general functioning and MH symptoms improved, and heavy smoking decreased. The organizational structure and QI activities provided a strong foundation for interactive problem-solving and adaptations that were needed during implementation.

Conclusions

This article highlights an example of the intersection of QI and implementation practice. Simplified QI processes, consistent post-implementation meetings, and change teams and champions facilitated implementation; however, ongoing training and support, especially related to data are needed. The OTP setting provided a strong foundation to build integrated care, but careful consideration of new workflows and changes in philosophy for staff is necessary.

Plain Language Summary: Providing medical and behavioral health treatment services in the same clinic using coordinated treatment teams, also known as integrated care, improves outcomes among those with chronic physical and behavioral health conditions. However, there are few practical examples of implementation of such programs in addiction treatment settings, which are promising, yet underutilized settings for integrated care programs. A multi-sectoral team used quality improvement (QI) and implementation strategies to implement integrated care into two opioid treatment programs (OTPs). The program enrolled over 1,200 clients and client general functioning and mental health (MH) symptoms improved, and heavy smoking decreased. Qualitative interviews provided important information about the barriers, facilitators, and context around implementation of this program. The OTP setting provided a strong foundation to build integrated care, but careful consideration of new workflows and changes in philosophy for staff, as well as ongoing training and supports for staff, are necessary. This project may help to advance the implementation of integrated care in OTPs by identifying barriers and facilitators to implementation, lessons learned, as well as providing a practical example of potentially useful QI and implementation strategies.

Keywords: integrated care, opioid treatment program, methadone maintenance, mental health, primary care, quality improvement, implementation practice

Introduction

For more than four decades, it has been recognized that individuals with co-occurring mental health (MH) and substance use disorders (SUDs) experience poor outcomes with high costs to the health care system (Minkoff & Covell, 2021). Individuals with SUDs frequently have co-occurring health care needs (Boyd et al., 2010; Irmiter et al., 2009; McCarty et al., 2010; Stoller et al., 2016). People with opioid use disorder (OUD) have elevated rates of hospital admissions and emergency department visits when compared to those without OUD (Masson et al., 2002; McCarty et al., 2010; White et al., 2005).

The United States (US) federal government, similar to governments internationally (Coates et al., 2021), has made considerable investment in the implementation of integrated care programs that address behavioral and physical health with the goal of improving patient outcomes and decreasing costs (Goldman et al., 2021). Fully integrated care is characterized as behavioral health and other health care professionals sharing the same sites, vision, and systems with all providers on the same team and having an in-depth understanding of each other's roles and expertise (SAMHSA-HRSA, 2013). Elements of integrated behavioral health care can include multidisciplinary teams, access to routine and urgent care, care coordination, seamless referral processes, systematic quality improvement (QI), and linkages with community and social services (Goldman et al., 2021). Individuals who use drugs are likely to experience many barriers when receiving physical health, MH, and SUD care in separate settings. Integrating care, especially within SUD treatment programs, may reduce disproportionate burdens of mental and physical health conditions among this population by making care more accessible (Berkman & Wechsberg, 2007; Brooner et al., 2013; Fareed et al., 2010; McLellan et al., 1993) and reducing the use of acute care (Gourevitch et al., 2007).

However, there are notable gaps in understanding the implementation of integrated care. Most programs and related research have focused on integrating MH or SUD treatment into primary care or specialty HIV/Hepatitis C care settings, or integrating physical or substance use care into MH settings (Coates et al., 2021; Goldman et al., 2021; Minkoff & Covell, 2021; Rich et al., 2018; Saunders et al., 2021; Zerden et al., 2021). A review of strategies to facilitate the implementation of integrated care for people with alcohol and drug problems identified only fourteen studies, the vast majority of which were not conducted in SUD treatment settings (Savic et al., 2017). Experts have suggested that, given the complexities of implementing integrated care, more attention to implementation methods and strategies is needed (Coates et al., 2021; Minkoff & Covell, 2021; Savic et al., 2017). Different settings (e.g., SUD vs. primary care) will have different workforce needs, workflows, and financing strategies (Goldman et al., 2021). Specific barriers, facilitators, and useful implementation strategies for integrated care in SUD treatment settings are not yet well documented.

Description of the Current Project

This article describes the implementation and evaluation of an integrated care program in opioid treatment programs (OTPs). OTPs are uniquely positioned to provide integrated care (Rich et al., 2018; Stoller et al., 2016), but are underutilized. For example, implementation should ideally occur in clinical settings where there is high client contact and appropriate clinical staff. OTPs are specially licensed to provide methadone, one of the most effective treatments available for OUD, under tight restrictions that require frequent—often daily—visits. For many, the OTP is a point-of-contact that provides opportunities for other health care interventions. Overall, 1,700 OTPs in the US are a critical part of the SUD treatment system, serving over 350,000 people per year (SAMHSA, 2021).

OTPs are mandated to have medical staffing (e.g., medical director and nurses) and infrastructure. However, OTP medical staff have historically had a narrow scope of work focused on medical assessments to ensure appropriate initiation of and response to methadone (Olsen & Mason, 2021). Integration of more expanded on-site medical and MH services into OTPs has been slow despite documented benefits (Fareed et al., 2010; Gourevitch et al., 2007; Olsen & Mason, 2021; Umbricht-Schneiter et al., 1994; Wright, 2019). In 2020, fewer than half of US OTPs (46%) provided MH services; testing for metabolic syndrome was provided by just 13% of OTPs and medical services by 18% (PEW, 2022; SAMHSA, 2021). Rather, OTPs tend to have care linkage arrangements with other facilities to address mental and physical health (Jones et al., 2019). Current regulations state only that “It is highly recommended, but not required, that OTPs provide basic primary care onsite” (“U.S. Code of Federal Regulations,” 2019).

The integrated care implementation project described in this article represents a multidisciplinary, multi-sectoral partnership between a community-based behavioral health provider, a state agency that oversees addiction treatment, academic partners, and an intermediary organization providing technical assistance (TA). In 2017, these partners received a Promoting Integration of Primary and Behavioral Health Care grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which made this project possible.

This article will highlight a practical example of the intersection of QI and implementation practice. Refined approaches for implementing QI that are tailored to under-resourced and overwhelmed addiction treatment programs are needed (O’Grady et al., 2020; O’Grady et al., 2021). QI practices can serve as important implementation and sustainability strategies (Koczwara et al., 2018; Minkoff & Covell, 2021; Powell et al., 2015) and have been utilized to improve quality and support implementation in SUD care (Ford et al., 2018; McCarty et al., 2007). Practical examples of this in real-world implementations are needed.

The goals of this article are to (i) describe the organizational infrastructure and strategies utilized to implement the integrated care program into two OTPs, (ii) provide an overview of the project's QI approach that guided implementation, (iii) present implementation, service, and clinical evaluation outcomes as well as contextual implementation factors, and (iv) highlight lessons learned. An implementation logic model (Figure 1) (Smith et al., 2020) is presented to organize the implementation description and show how the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al., 2009) was used to link implementation determinants to strategies utilized (Powell et al., 2015) and evaluation outcomes (Proctor et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

Logic Model Describing Implementation Determinants, Strategies, Mechanisms, and Outcomes.

Description of Integrated Care Program

The integrated care program, named “Together in Care”, built services into OTPs to provide whole-person care, including more fully addressing primary care and MH needs instead of referring these services out as is more typical. The program included medical and MH screening and services, care coordination, wellness programming, and supportive services. For example, the program integrated new physical health workflows for procedures and lab work at client admission to identify the risk for diabetes, severe smoking (using breath carbon monoxide [CO]), hypertension, obesity, hyperlipidemia, as well as guidelines to monitor and treat mild to moderate cases. Similarly, for MH, screenings were added for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression. In addition to screening, MH services for mild to moderate cases were provided by newly added licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs). Physical or MH cases that could not be stabilized in the OTP, including all cases of Hepatitis C or HIV/AIDS, were referred to co-located or nearby Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) or MH clinics with ongoing case coordination between the OTP and referral location. Workflows were developed to streamline these referral processes. Other wellness support services included new groups (e.g., smoking cessation, illness and management) and regular clinic-wide health promotion/education campaigns (e.g., healthy eating).

Staff was hired to support the new services (i.e., medical assistants, nurse practitioners, social workers, and peers). Trainings were provided to increase the staff's ability to provide integrated services and use evidence-based practices (e.g., trauma-informed care and motivational interviewing). Regular case conferences among interdisciplinary staff were held to support and better coordinate care. Peers and care managers provided care coordination and linked clients to social services (e.g., social security and housing).

Clients were enrolled in the integrated care program if they smoked cigarettes or had at least one physical or MH risk factor. “Together in Care” has been implemented into two OTPs, both in the Bronx, NY, with services starting in the first site in February 2018 and the second in January 2020. The third OTP in Brooklyn is currently in the implementation process. All OTPs are part of the same behavioral health organization—a well-established community-based nonprofit committed to improving the quality of life and well-being of underserved communities and offering bilingual (English/Spanish) and culturally competent services.

Organizational Structure of the “Together in Care” Implementation Team

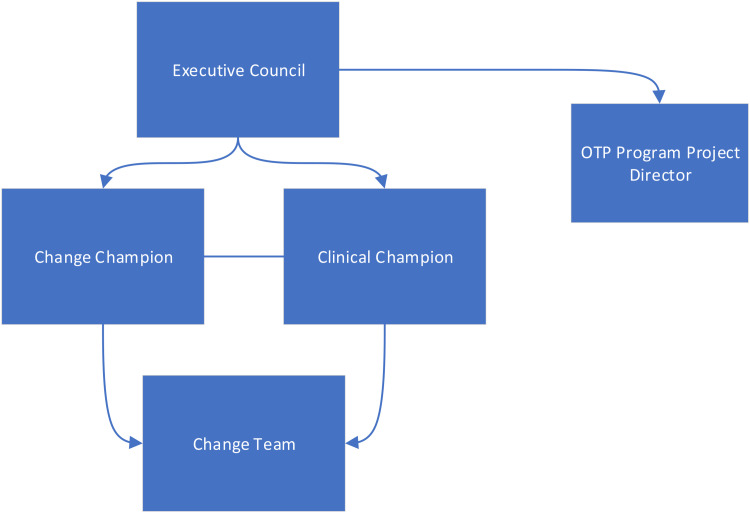

The organizational structure of the implementation team (Figure 2) was designed to meet the following goals: (i) rapidly implement integrated care into OTPs; (ii) develop capacity for continuous improvement of clinic functioning; and (iii) inform policy and practice at the organizational and state level. An executive council held quarterly meetings and provided oversight, guidance, and resources to the implementing clinics. The council included representatives from the behavioral health executive team, state agency leadership, TA organization, and academic partners.

Figure 2.

Organizational Structure of the Implementation Team.

A change team, meeting weekly or biweekly, comprised of six to seven staff from the OTP representing different roles (e.g., counselors and medical staff), were responsible for implementation and QI activities. Two champions led the change team: a change champion and a clinical champion. The change champion led QI by advocating for structured implementation processes (e.g., small rapid cycle tests), making changes as informed by clinic data, and communicating with organizational leadership about project needs. The clinical champion focused more on clinical care changes and identifying necessary modifications to infrastructure and workflow. A project director supported the change team's efforts. Leadership from the behavioral health organization provided guidance and regularly attended change team and operational meetings.

Logic Model Describing Implementation Determinants, Strategies, and Outcomes

We employ the implementation research logic model (Smith et al., 2020) to lay out our implementation approach and outcomes (Figure 1). In the model, determinants are factors that might prevent or enable implementation; we utilized the CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009) to organize determinants. Strategies are interventions used to increase adoption of the targeted innovation. We consulted the “Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change” (ERIC) list when considering strategies (Powell et al., 2015). Mechanisms are processes through which implementation strategies operate to affect implementation outcomes. Determinants, strategies, and mechanisms were identified prior to grant implementation during grant planning stakeholder meetings among the executive council.

QI Approach

We utilized QI methods, such as conducting small tests of change, as an implementation strategy. The academic team and TA organization developed a simplified version of rapid QI cycles, named the Enhancing Care model, which drew from classic QI guides and previous QI efforts in behavioral health settings (Ford et al., 2018; Langley et al., 1996). The Enhancing Care model (Figure 3) was designed to use language and procedures more familiar to staff working in behavioral health settings and assist them in conducting continuous QI utilizing a structured method. The Enhancing Care model emphasizes the use of data to inform and guide implementation efforts led by champions and a change team.

Figure 3.

The Enhancing Care Quality Improvement (QI) Model.

Academic partners worked closely with the State agency to develop the concept and model for OTP integrated care. Further, academic partners drew from previous and ongoing research and implementation projects to create and refine the Enhancing Care model. Academic partners guided the TA organization in creating training materials and approaches. The TA organization, with support from academic partners, provided training and coaching to the champions and change team on the Enhancing Care model using an external practice facilitation approach (Baskerville et al., 2012), including assisting at each change team meeting. The TA team also conducted a needs assessment and walkthrough of each clinic prior to implementation.

Evaluation Methods

Our evaluation approach, guided by our implementation logic model (Figure 1), aimed to glean early implementation learnings that could be used to inform the program as it rolled out. Proctor's framework (Proctor et al., 2011) identifies three distinct, but related, categories of outcomes for understanding implementation. We selected outcomes from each category that we felt were important to understanding early implementation and collected quantitative and qualitative data: Implementation (appropriateness, acceptability, penetration), Service (Efficiency), and Client (symptoms, functioning). We collected additional qualitative data as the project moved into the second site to understand the implementation context as informed by the CFIR. This was considered QI/evaluation and deemed nonhuman subjects’ research by the Partnership to End Addiction IRB; interviewed staff verbally consented to participate and clients signed consents.

Implementation and Service Outcomes

Interviews, all recorded, were conducted among seven program staff from the first OTP (e.g., counselors and medical staff) from October to November 2018, ∼8 months after the program start to understand early implementation and service outcomes (Medicine, 2006; Proctor et al., 2011): program appropriateness (program fits with existing practices and norms; program seems like a good match for client needs), program acceptability (i.e., meets staff approval, staff like it, it is appealing and welcome), and efficiency of client connection to services. Quantitative program data informed our penetration implementation outcome (Numerator: enrolled integrated care clients; Denominator: average clinic census).

Analysis

Semi-structured interviews were analyzed using rapid identification of themes from audio recordings (RITA) (Neal et al., 2014). RITA is a rapid evaluation method that allows for timely feedback to project partners with quick and efficient identification of themes in audio-recorded qualitative data without the need for transcription. RITA is best used when providing rapid feedback on core aspects of an evaluation rather than doing a comprehensive qualitative analysis of all available data. It involves six steps: (i) specifying key evaluation foci, (ii) identifying key themes and creating a codebook, (iii) creating a coding form, (iv) testing/refining coding form based on a subset of interviews, (v) coding, and (vi) analysis of codes. Key themes were identified deductively based on our identified theoretical frameworks. We coded both for the presence of a theme during a time segment and valence (positive, negative, or neutral). We analyzed codes to determine which were most or least often mentioned as well as the ratio of positive to neutral/negative valence codes for each theme. Coded time segments were 2 min long and two researchers independently coded each interview. During coding, we noted time stamps in which there were quotations that were particularly good illustrations of themes and selectively transcribed them. Coders held biweekly meetings to review coding, refine the codebook, and resolve any disagreements.

Client Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes were examined using the mandated SAMHSA National Outcome Measures (NOMS) (SAMHSA, 2017). Participants complete the NOMS at baseline and 6-month follow-up. For the purposes of this evaluation, we focused on functional, MH, and physical indicators from the NOMS, as well as demographics. Functional outcomes were self-reported overall health (How would you rate your overall health right now; 1 = excellent; 5 = poor) and quality of life (in the past 4 weeks, how would you rate your quality of life; 1 = very poor; 5 = very good). Medical indicators, collected by OTP medical staff, included blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), breath CO (for smoking) by exhalation through a CO monitor, and cholesterol via blood draw. Frequency of nonspecific psychological distress was assessed with the 6-item K6 (5-point rating; none of the time to all of the time) (Kessler et al., 2002). Additional MH screenings administered by OTP staff at baseline and 3-months follow-up include the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., 2006) for generalized anxiety disorder and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression (Kroenke et al., 2001).

Analysis

Dependent samples t-tests were used to examine differences between scores at baseline and follow-up with Bonferroni-corrected p-values (.005) to correct for multiple comparisons.

Implementation Context

The second set of semi-structured interviews were conducted among nine members of organizational leadership (e.g., grant project director, director of OTP services, chief medical officer, nursing director, behavioral health services director, and clinic directors) to understand the context surrounding implementation in the first two clinics, including usefulness of implementation strategies, as well as impacts of the clinic inner setting. These were different interviewees than those described in the implementation outcome section. Semi-structured interview guides were created to examine all elements of the CFIR model. However, for the purposes of this evaluation with a focus on early implementation context and implementation strategies, we analyzed the following CFIR constructs: Process (planning and engaging, executing, reflecting and evaluating), Characteristics of Individuals (self-efficacy, knowledge, and beliefs), and Inner Setting (structural characteristics, networks/communication, culture, and implementation climate). Interviews were conducted in December 2020 through February 2021. All interviews were recorded and selective quotes illustrative of themes were transcribed. We used the same RITA approach as described above for analysis.

Evaluation Results

Implementation Outcomes

Appropriateness and Acceptability

Table 1 shows the themes and results for the qualitative analysis of implementation outcomes. Of the three implementation themes, Appropriateness: Fit with Existing Practices/Norm, was the most discussed with more neutral/negative comments than positive. One challenge in this theme was that staff had more work than before the program was implemented. Staff were busier and sometimes overwhelmed with additional tasks. It was suggested that the setting should move toward a model that functioned more like a doctor's office, in terms of scheduling and structure, to better assist clients. In addition, providers indicated they would like to go beyond providing what they called “primary care light” but additional staffing and resources would be needed. On the positive side, participants felt good about how they were able to extend services.

Table 1.

Results of the Qualitative Analysis for Implementation and Services Outcomes Themes: Frequency of Positive and Neutral/Negative Mentions and Illustrative Quotes.

| Theme | Positive | Neutral/Negative | Total | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation outcomes | ||||

| Acceptability | 15 | 7 | 22 | “Methadone maintenance is quite dogmatic, there are certain rules and this (integrated program) put a whole new spin on things, it made the patients more 3-dimensional, we're not just talking about their chemical dependency, we're talking about their health…so it made it much more interesting to take care of patients, it helped me have more information.” (Participant 1.A) |

| Appropriateness: fit with existing practices/norms | 9 | 20 | 29 | “It's more work, but it's good work, because

it's more information that we weren't getting before

or we really wasn’t paying attention to, I believe,

so now we are more attentive to the information that

is getting collected…let's revisit the questionnaire

and the reassessments and has anything changed and

explaining that all to them.” (Participant

6.A) “With the implementation, it's like a continuation of what the services could look like, is kinds of like, you know, you have a little stem that has branched out a little more, most clinics maybe do a little bit of the things that we are doing, but we are just expanding on it to cover all of our bases.” (Participant 4.A) |

| Appropriateness: good match to client needs | 18 | 3 | 21 | “…but now here, I'll sit there, what are you taking, let's review your medications, is it working, let's adjust it, so I think that they'll get their immediate concerns met…those conditions, hey you need a refill on your medication, hey I noticed your blood pressure was 200 over 190…let me prescribe something to you, let me recheck you in 5 min, don't leave, so I think for the immediate needs its working well.” (Participant 8.A) |

| Service outcome | ||||

| Client service connection | 10 | 16 | 26 | “Sometimes I feel like appointments, this is more for the mental health piece, for the providers we have in place, whether it be upstairs or (other facility), they are a little far out, and sometimes they (clients) want the help now…so that's where it doesn't meet the needs as well as I would personally like…sometimes it's a month away or sometimes even further than that, their needs should be met a little sooner.” (Participant 4.A) |

Both the Acceptability and Appropriateness: Good Match to Client Needs themes were mentioned at similar rates and both were viewed as mostly positive. For Acceptability, staff felt they had more information to help their clients, saw the program as an opportunity to learn more and grow professionally, and felt it filled an important client need. However, they also felt more training would be useful for them to be able to perform the new duties that came along with the program as well as additional staff to support the new services.

For the Appropriateness: Good Match to Client Needs theme, most participants felt the program helped clients better manage physical and MH care needs. Several staff mentioned that housing was important to address as part of an integrated care program because being stably housed could have a big positive impact on client outcomes, but that it remained challenging connecting clients with housing during the course of the project.

Penetration

The integrated care program served 1,261 clients between February 2018 and December 2020 (884 in clinic 1 and 377 in clinic 2), representing 69% of clinic 1 OTP clients and 59% of clinic 2. Table 2 provides demographics of the clients served. When comparing integrated care client demographics to demographics of clients served in the clinic overall during the grant period, they were very similar (e.g., Hispanic/Latino: Clinic 1: all clients: 74%; Clinic 1 integrated care clients 73%; Clinic 2 all clients: 76%; Clinic 2 integrated care clients 77%) and were representative of the community where the clinics operate. This is a highly disenfranchised population with high medical and psychiatric morbidity and limited resources to address their whole-health needs. The group was overwhelmingly Latinx and/or Black/African American.

Table 2.

Description of Clients Reached by the Integrated Care Program (n = 1261).

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Clinic | |

| Clinic 1 | 884 (70%) |

| Clinic 2 | 377 (30%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 902 (72%) |

| Female | 352 (28%) |

| Transgender | 6 (<1%) |

| Education | |

| 11th grade or less | 624 (50%) |

| 12th grade/GED | 435 (35%) |

| Some college/college degree or higher | 194 (15%) |

| Age | |

| 16–25 years | 30 (2%) |

| 26–44 years | 469 (37%) |

| 45–64 years | 684 (55%) |

| 65 + years | 77 (6%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black non-Hispanic | 176 (14%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 934 (76%) |

| White non-Hispanic | 102 (8%) |

| Other non-Hispanic | 18 (2%) |

| Housing | |

| Homeless in past 30 days | 195 (16%) |

| Does not have stable place to live in community | 648 (51%) |

| Involved in the criminal justice system | 91 (8%) |

| Employment | |

| Full or part-time employment | 113 (9%) |

| Retired | 24 (2%) |

| Unemployed | 503 (87%) |

| Other | 21 (2%) |

| Substance use at baseline | |

| Used any illegal substance in past 30 days | 787 (63%) |

| Past 30 day daily or almost daily street opioid use | 306 (25%) |

| Past 30 day daily or almost daily prescription opioid use | 151 (12%) |

Service Outcome

The service outcome (Table 1), Efficiency of Connection to Services, had more neutral/negative than positive comments. For example, referrals outside of the OTP were still needed to address severe medical and MH issues that the clinic was not able to manage, and for MH, it was difficult to get a quick appointment.

Clinical Outcomes

Clients who stayed in the integrated care program for at least 6 months and completed a 6-month follow-up interview (n = 593) were included in the outcome analysis. We examined whether those who completed the follow-up differed from those in the baseline sample using chi-square analyses and found that clients who were women, over 65, not criminal justice involved, and not homeless were more likely to complete the follow-up. There were no differences in completion by clinic, employment status, education level, or race. Results (Table 3) suggest that functional and MH outcomes improved at follow-up, including overall health and quality of life, depression, general psychological distress, and anxiety. Breath CO also improved suggesting that heavy smoking decreased. There were no significant differences in other physical indicators (i.e., cholesterol, blood pressure, and BMI).

Table 3.

Client Outcomes for Functional, Mental Health (MH), and Physical Health.

| Variable (n) | Baseline Mean (SD) | 3-month follow-up Mean (SD) | p-Value | 6-Month Follow-Up Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional indicators | |||||

| Overall health (n = 574) | 3.34 (1.04) | 3.15 (1.04) | .000* | ||

| Quality of life (n = 573) | 3.51 (.87) | 3.70 (.87) | .000* | ||

| MH | |||||

| Distress (K6; n = 575) | 7.38 (6.13) | 5.88 (6.05) | .000* | ||

| Depression (PHQ-9; 411) | 8.12 (8.00) | 6.54 (6.36) | .000* | ||

| Anxiety (GAD-7; 412) | 7.48 (7.18) | 6.00 (6.00) | .000* | ||

| Physical health | |||||

| Breath CO (n = 390) | 14.52 (8.71) | 12.86 (9.83) | .002* | ||

| Total cholesterol (n = 185) | 171.82 (40.96) | 171.92 (39.53) | .963 | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (n = 577) | 128.08 (20.66) | 127.28 (18.88) | .319 | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure (n = 577) | 78.10 (10.81) | 78.39 (9.65) | .523 | ||

| BMI (n = 575) | 28.08 (7.04) | 28.23 (6.60) | .387 | ||

Notes: BMI = body mass index; CO = carbon monoxide

*Significant at Bonferroni-corrected p-value (.005).

Contextual Implementation Factors

Contextual implementation factors themes are presented in Table 4. The Process themes were frequently discussed, and included how the clinics planned for, executed, and evaluated implementation of the integrated care program. In Process: Planning and Engaging, which had a higher proportion of positive than neutral/negative comments, the change team was seen as a strong platform for how implementation was planned and executed, mainly because it brought together and engaged interdisciplinary team members and provided focused time and effort across the clinic. Neutral/negative comments in this theme indicated that more pre-implementation planning time and more efficient change team meetings were needed. Champions also indicated that they would like more training on QI techniques and leading a change team. For example, champions were unsure how to structure change team meetings and QI rapid change cycles, especially as the project moved from a focus on implementing new practices to doing ongoing tracking and monitoring of practices that had been newly implemented. The TA team provided additional support, especially the ongoing tracking and monitoring and identifying a target for change elements of the Enhancing Care model, but it was hard for change teams to make the transition and see the purpose of coming together regularly once the initial flurry of implementation was over.

Table 4.

Results of the Qualitative Analysis for Contextual Implementation Factors Themes: Frequency of Positive and Neutral/Negative Mentions and Illustrative Quotes.

| Theme | Positive | Neutral/Negative | Total | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process: Planning and engaging | 33 | 19 | 52 | “The change team meeting was really a critical foundation to pull in all the key providers into the same workspace, talking about what's working and what's not working and making those modifications. Having all of the providers and resources at the table made that easy.” (Participant 6.B) |

| Process: Executing and reflecting and evaluating | 30 | 43 | 73 |

“We were able to bring additional screening into the

OTP practice, you know, diabetes screening, lipids

screening, some more in depth mental health screening,

and then also the carbon monoxide testing also…and then

there was sort of a seamless transition if there were

really complex issues that needed to be managed by the

FQHC provider.” (Participant

1.B) “You plan something out, and it looks really good on paper, but you start doing it, and you start running into, okay, obstacles, it is very simple to sit there and say “this is how we want it”, because that's normally how it happens, but you put it on the floor and you start doing, then you can see how is it really going to work, and then you have to do the PDSA, let's change this.” (Participant 2.B) |

| Individuals: Self-efficacy, knowledge, and beliefs about integrated care | 38 | 19 | 57 | “To have one central location to be able to go to…there was so much that took place here and that this population needs. I would constantly hear from clients that they couldn't afford to get to the place that they needed to go to for primary care, they would constantly put themselves in situations like jumping the (subway) turnstile that could have gotten them arrested, or they didn't have the bus fare to go to their appointment, which they really really needed. To have one place and to take away that frustration for them was tremendous.” (Participant 8.B) |

| Inner setting: Structural characteristics | 22 | 22 | 44 | “We had to allot space for the counselors, for the social workers, the medical assistants, we had to make physical adjustments for that, there was one large room that we had to put cubicles in that became the (program) headquarters.” (Participant 1.B) |

| Inner setting: Networks/communication | 21 | 7 | 28 | “The administration “is bringing people together, all different departments, to get to know each other and learn about each other's practices, so that has been a big plus.” (Participant 3.B) |

| Inner setting: Culture | 9 | 5 | 14 | “They (leadership) were definitely central to carrying out this grant, it would be difficult to do without our leaders.” (Participant 5.B) |

| Inner setting: Implementation climate | 25 | 5 | 30 | “The agency has been moving toward integration for a while now, so that makes it easier because you are getting support from the top, that we're not working in silos, this is what we are doing, you are expected to do it. As they are working with it from the top, they are giving us policies and they are bringing us together.” (Participant 3.B) |

In the Process: Executing, Reflecting, and Evaluating theme, participants spoke positively of the workflows they were able to develop around additional screenings and services.

Peers hired for the program were viewed as strong contributors to the program in terms of support services and maintaining ongoing engagement with clients. Challenges in implementation noted in this theme, mentioned more frequently than positives, related to health monitoring that required greater complexity (e.g., lab work) and managing how to bill and be reimbursed for new services, particularly they noted that because they are licensed as a SUD program, they could only provide minimal medical care, so work that was done was not billable or reimbursed. Further, finding social workers and psychiatric nurse practitioners and psychiatrists who were interested in working in integrated care within an OTP was difficult.

Referrals to MH services outside of the OTP were also challenging because of the lack of providers or available appointments in the immediate area. In fact, several staff commented that they thought, because they were a behavioral health clinic, the MH services would be easy to implement, yet because of challenges in staffing and identifying what level of MH issue could and could not be serviced in the OTP, this was difficult.

Data collection and management to support QI and inform implementation practice was challenging. It was difficult to extract data from the EHR, some data had to be collected manually, and compiling and analyzing it was not a skill that clinic staff had or could dedicate time to. Despite these challenges, participants referred to an ongoing process of refining their workflows and using QI practices for implementation, such as using small tests of change as indicated by the Enhancing Care QI process. Implementing integrated care is multifaceted and sites could not realistically implement every new service simultaneously, challenging sites with deciding where and how to start. Site change teams used the Enhancing Care process early in implementation to identify which medical and MH screenings to implement first by assessing client need, their current practices, and perceived implementation ease. They developed new protocols and conducted small tests of change. For example, the change team identified the PHQ-9 depression screening as their first implementation target, brainstormed, and then chose a workflow to test (i.e., would be administered during intake), and tested this over 2 weeks. They collected data on the number of clients screened of those eligible and feedback from the intake counselor, assessed success, made some adjustments (i.e., changed from intake to first counseling session), retested, and collected more data over 2 weeks. The change team also used the Enhancing Care process to assess ongoing services important to the new integrated care program. For example, program data suggested low smoking cessation group attendance. They brainstormed reasons for this and ways to improve it. One solution was to test changing the time the group was offered; they found after 2 weeks that the change greatly increased attendance.

In the Individuals theme, there were a much greater proportion of positive comments. Most staff was bought into the idea of integrated care in the OTP and saw the benefit. However, some felt they needed more training or did not feel confident in taking on new roles or did not fully understand how much work it would be to integrate services.

In the Inner Setting themes, the structural characteristics of the organization and clinics as well as the implementation climate were most discussed. Structural Characteristics was evenly split between neutral/negative and positive comments; the array of services provided by the organization, was seen as a positive. In addition, the OTPs were in buildings that had co-located primary care (clinic 1) or both primary care and MH clinics (clinic 2). Though not strongly utilized by the OTP before this project, this co-location was built upon and seen as a positive because staff could more easily make referrals or tap into expertise within the same building. On the neutral/negative side, one of the clinic buildings was older with limited space, and was not seen as ideal for adding new services and staff, despite modifications made.

For Implementation Climate, which was overwhelmingly positive, integrated care was a priority and expected throughout the larger organization, making this new program easier to implement. In the Network and Communication theme, the integrated care program was seen as a catalyst for improving communication between teams that normally did not communicate and facilitated the broadening of professional networks within the clinics and organization. Improving communication did require some training and new practices, such as how to document and read the EHR, and new case conferencing practices. Culture was the least discussed, but was seen as positive because of the support of leadership for the program, which created a culture where integrated care and conducting QI activities was seen as a norm and value of the organization.

Lessons Learned

This article describes the implementation of an integrated care program into OTPs and provides lessons learned about facilitators and barriers that may be useful for other OTPs. It also highlights a practical example of the intersection of QI and implementation practice. We provide key lessons learned in Table 5.

Table 5.

Key Lessons Learned.

Quality improvement (QI)

|

| Implementation practice |

|

| Integrated care |

|

Notes: OTPs = opioid treat programs; SUD = substance use disorder; TA = technical assistance.

For patient clinical outcomes, client general functioning and MH symptoms improved, and heavy smoking decreased over the course of the program. While some of the medical indicators did not improve at 6-month follow-up, they remained stable, which is important because several were within healthy ranges at baseline (e.g., diastolic blood pressure). Other studies examining the provision of primary care within SUD treatment settings have shown that it is difficult to improve medical outcomes; longer follow-up periods may be needed to see greater improvements (Fareed et al., 2010).

Regarding implementation outcomes, staff found the program to generally be acceptable and appropriate, especially because it was a good match to client needs, but also noted that the new services added to already busy workflows and more staffing were needed to fully reach the program's potential. The program had a high level of penetration (∼60%–70%), but noted difficulties in connecting clients with some services, especially MH.

We also learned important context about implementation, including views of staff implementing the program, usefulness of implementation strategies, as well as impacts of the inner setting of the clinics. For example, the organizational structure and QI activities, including the champions and change team, provided a strong foundation for interactive problem-solving and adaptations that were needed. Staff was bought into the idea of integrated care and felt that communication among and between teams had improved and that the organizational culture and implementation climate were facilitators.

There have been recent calls to better align implementation science with improvement practice (Leeman et al., 2021; Nilsen et al., 2022). This article provides an example of how improvement practice (e.g., QI cycles) can support implementation. Implementation teams used the Enhancing Care QI process both to implement new workflows related to integrated care (e.g., new medical and MH screenings) as well as to improve existing services that were necessary for integrated care. However, staff felt that more clinical trainings and well as trainings on QI were needed. In particular, champions needed support around structuring change team meetings to focus on QI topics as well as how to structure QI rapid change cycles, especially as they transitioned to maintaining and monitoring newly implemented services. This may reflect the challenge of learning and building skill and infrastructure for both QI and integrated care at the same time. It may also have implications for challenges to the sustainability of continuous QI within integrated SUD programs. Future research should examine the best ways to balance developing knowledge, skill, and infrastructure around both QI and new integrated clinical services. It may be important to stagger learning and build in QI training boosters over time.

The main operational challenges were related to implementing complex medical procedures, billing, staffing, lack of space, and extracting and using EHR data. Data is critical to both QI processes and implementation practice, yet OTPs often do not have the capacity or infrastructure to manage, track, and analyze data in a systematic and ongoing way. This program shared some barriers and facilitators to integrating care previously described in the literature, such as staffing resources, EHR infrastructure, shared values among staff, staff engagement, flexible organizations, and building communication among providers (Coates et al., 2021; Goldman et al., 2021; Savic et al., 2017).

Limitations

While informative, this project was not a randomized controlled trial; clinical outcomes must be interpreted with caution because positive outcomes may be due to regression of the mean, missing data, or factors other than intervention effects. The COVID-19 pandemic hit New York City when the second clinic was only 2 months into implementation, and especially impacted the Bronx neighborhood in which the clinic resides, causing much disruption and limiting the project's ability to enroll clients and collect data. However, the organization's resiliency allowed for adjustments that sustained client care and maintained onsite services (e.g., development of new safety policies and protocols and more flexible methadone take-home schedules).

Our overall evaluation approach had several limitations due to the need to balance staff burden, available resources, and inform the project in practical ways as implementation was occurring in real time. First, most of our evaluation activities focused on early implementation and only on two sites within the same organization. We did not capture implementation issues that may have occurred later in implementation or long-term sustainability. Second, because we were focused on rapid, practical feedback to program partners and funders, we limited our qualitative data collection to 16 individuals spread across two different timepoints for two different purposes. As a result, we may not have a great deal of depth, but nonetheless gained important information on multiple topics that we may not have had should we have made more intensive efforts on a single topic. Further, we used mostly qualitative approaches to evaluate the QI aspect of the project because we felt this would yield the most useful information; therefore, we do not have structured, quantitative data on this topic. Finally, we examined a limited set of outcomes from the CFIR and Proctor frameworks; there are other important potential outcomes that were not assessed (e.g., feasibility, fidelity, and costs). Future research could expand to other outcomes.

Future Directions

Financial incentives to implement integrated care programs in OTPs, when compared to other clinical settings, as well as the costs of implementing and sustaining such programs along with QI practices in OTPs need to be better understood. This program had grant funding to support start-up, staffing, and a relatively intensive implementation strategy with an external TA provider, QI procedures, change teams, and champions. While these strategies appeared to support implementation, and align with strategies recently recommended for integrated care implementation (Minkoff & Covell, 2021), further refining and testing the implementation and QI approach, using randomized trials and adaptive designs that test less and more intensive strategies, would be informative (Kilbourne et al., 2013).

The OTPs in this program were able to provide some level of primary and MH care, but were not able to fully manage complex cases. However, previous research suggests that even brief health counseling and screening in OTP clinics can have positive impacts on client health (Fareed et al., 2010). Defining the levels of medical and MH care that can be provided in OTPs and creating clinical and implementation guidelines that would lead to the best client outcomes, along with the staffing and resources required, would inform future implementations in OTPs or other SUD treatment settings. Further, while OTP programs are often under a single license (e.g., from SUD regulatory body), determining whether integrated licenses (e.g., MH + SUD), such as those available in New York State, significantly improve implementation, service, and clinical outcomes could be studied.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) under grant 1H79SM080251. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of SAMHSA.

ORCID iDs: Megan A. O’Gradyhttps://orcid.org/0000-0002-1121-734X

References

- Baskerville N. B., Liddy C., Hogg W. (2012). Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. The Annals of Family Medicine, 10(1), 63. 10.1370/afm.1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman N. D., Wechsberg W. M. (2007). Access to treatment-related and support services in methadone treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32(1), 97–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd C., Leff B., Weiss C., Wolff J., Hamblin A., Martin L. (2010). Faces of Medicaid: Clarifying Multimorbidity Patterns to Improve Targeting and Delivery of Clinical Services for Medicaid Populations.

- Brooner R. K., Kidorf M. S., King V. L., Peirce J., Neufeld K., Stoller K., Kolodner K. (2013). Managing psychiatric comorbidity within versus outside of methadone treatment settings: A randomized and controlled evaluation. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 108(11), 1942–1951. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates D., Coppleson D., Travaglia J. (2021). Factors supporting the implementation of integrated care between physical and mental health services: An integrative review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 36(2), 245–258. 10.1080/13561820.2020.1862771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science [journal article]. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fareed A., Musselman D., Byrd-Sellers J., Vayalapalli S., Casarella J., Drexler K., Phillips L. S. (2010). Onsite Basic Health Screening and Brief Health Counseling of Chronic Medical Conditions for Veterans in Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Journal of addiction medicine, 4(3), 160–166. https://journals.lww.com/journaladdictionmedicine/Fulltext/2010/09000/Onsite_Basic_Health_Screening_and_Brief_Health.7.aspx. 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181b6f4e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J. H., Osborne E. L., Assefa M. T., McIlvaine A. M., King A. M., Campbell K., McGovern M. P. (2018). Using NIATx strategies to implement integrated services in routine care: A study protocol. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 431. 10.1186/s12913-018-3241-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M. L., Scharf D. M., Brown J. D., Scholle S. H., Pincus H. A. (2021). Structural Components of Integrated Behavioral Health Care: A Comparison of National Programs. Psychiatric Services, 73(5), 584–587. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourevitch M. N., Chatterji P., Deb N., Schoenbaum E. E., Turner B. J. (2007). On-site medical care in methadone maintenance: Associations with health care use and expenditures. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmiter C., Barry K. L., Cohen K., Blow F. C. (2009). Sixteen-year predictors of substance use disorder diagnoses for patients with mental health disorders. Substance Abuse, 30(1), 40–46. 10.1080/08897070802608770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. M., Byrd D. J., Clarke T. J., Campbell T. B., Ohuoha C., McCance-Katz E. F. (2019). Characteristics and current clinical practices of opioid treatment programs in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, 107616. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R., Andrews G., Colpe L., Hiripi E., Mroczek D., Normand S., Zaslavsky A. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. 10.1017/S0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne A. M., Abraham K. M., Goodrich D. E., Bowersox N. W., Almirall D., Lai Z., Nord K. M. (2013). Cluster randomized adaptive implementation trial comparing a standard versus enhanced implementation intervention to improve uptake of an effective re-engagement program for patients with serious mental illness. Implementation Science, 8(1), 136. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczwara B., Stover A. M., Davies L., Davis M. M., Fleisher L., Ramanadhan S., Schroeck F. R., Zullig L. L., Chambers D. A., Proctor E. (2018). Harnessing the synergy between improvement science and implementation science in cancer: A call to action. Journal of Oncology Practice, 14(6), 335–340. 10.1200/JOP.17.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley G. J., Nolan K. M., Nolan T. W., Norman C. L., Provost L. P. (1996). The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman J., Rohweder C., Lee M., Brenner A., Dwyer A., Ko L. K., O’Leary M. C., Ryan G., Vu T., Ramanadhan S. (2021). Aligning implementation science with improvement practice: A call to action. Implementation Science Communications, 2(1), 99. 10.1186/s43058-021-00201-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson C. L., Sorensen J. L., Batki S. L., Okin R., Delucchi K. L., Perlman D. C. (2002). Medical service use and financial charges among opioid users at a public hospital. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 66(1), 45–50. 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00182-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D., Gustafson D. H., Wisdom J. P., Ford J., Choi D., Molfenter T., Capoccia V., Cotter F. (2007). The network for the improvement of addiction treatment (NIATx): Enhancing access and retention. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(2-3), 138–145. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D., Perrin N. A., Green C. A., Polen M. R., Leo M. C., Lynch F. (2010). Methadone maintenance and the cost and utilization of health care among individuals dependent on opioids in a commercial health plan. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 111(3), 235–240. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A. T., Arndt I. O., Metzger D. S., Woody G. E., O'Brien C. P. (1993). The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. JAMA, 269(15), 1953–1959. 10.1001/jama.1993.03500150065028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicine I. o. (2006). Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions (Quality Chasm Series Issue. N. A. Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkoff K., Covell N. H. (2021). Recommendations for Integrated Systems and Services for People With Co-occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Conditions. Psychiatric Services, 73(6), 686–689. 10.1176/appi.ps.202000839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal J. W., Neal Z. P., VanDyke E., Kornbluh M. (2014). Expediting the analysis of qualitative data in evaluation: A procedure for the rapid identification of themes from audio recordings (RITA). American Journal of Evaluation, 36(1), 118–132. 10.1177/1098214014536601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P., Thor J., Bender M., Leeman J., Andersson-Gäre B., Sevdalis N. (2022). Bridging the Silos: A Comparative Analysis of Implementation Science and Improvement Science [Systematic Review]. Frontiers in Health Services, 1, 1–13, 10.3389/frhs.2021.817750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Grady M. A., Lincourt P., Gilmer E., Kwan M., Burke C., Lisio C., Neighbors C. J. (2020). How are substance use disorder treatment programs adjusting to value-based payment? A statewide qualitative study. Substance Abuse : Research and Treatment, 14, 1–10. 10.1177/1178221820924026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady M. A., Lincourt P., Greenfield B., Manseau M. W., Hussain S., Genece K. G., Neighbors C. J. (2021). A facilitation model for implementing quality improvement practices to enhance outpatient substance use disorder treatment outcomes: A stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial study protocol. Implementation Science, 16(1), 5. 10.1186/s13012-020-01076-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen Y., Mason A. (2021). Bringing primary care to opioid treatment programs. In Wakeman S. E., Rich J. D. (Eds.), Treating Opioid Use Disorder in General Medical Settings (pp. 173–188). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-030-80818-1_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PEW. (2022). Improved Opioid Treatment Programs Would Expand Access to Quality Care https://www.pewtrusts.org/fr/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2022/02/improved-opioid-treatment-programs-would-expand-access-to-quality-care

- Powell B. J., Waltz T. J., Chinman M. J., Damschroder L. J., Smith J. L., Matthieu M. M., Proctor E. K., Kirchner J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1), 21. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A., Griffey R., Hensley M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich K. M., Bia J., Altice F. L., Feinberg J. (2018). Integrated models of care for individuals with opioid use disorder: How do we prevent HIV and HCV? Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 15(3), 266–275. 10.1007/s11904-018-0396-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA (2017). SAMHSA's Performance Accountability and Reporting System (SPARS): NOMS Client-Level Measures for Discretionary Programs Providing Direct Services.

- SAMHSA. (2021). National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2020.

- SAMHSA-HRSA (2013). A Standard Framework for Levels of Integrated Healthcare.

- Saunders E. C., Moore S. K., Walsh O., Metcalf S. A., Budney A. J., Cavazos-Rehg P., Scherer E., Marsch L. A. (2021). “It’s way more than just writing a prescription”: A qualitative study of preferences for integrated versus non-integrated treatment models among individuals with opioid use disorder. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 16(1), 8. 10.1186/s13722-021-00213-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savic M., Best D., Manning V., Lubman D. I. (2017). 2017/04/07). Strategies to facilitate integrated care for people with alcohol and other drug problems: A systematic review. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 12(1), 19. 10.1186/s13011-017-0104-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. D., Li D. H., Rafferty M. R. (2020). The implementation research logic model: A method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implementation Science, 15(1), 84. 10.1186/s13012-020-01041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R. L., Kroenke K., Williams J. B. W., Löwe B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller K. B., Stephens M. C., Schorr A. (2016). Integrated Service Delivery Models for Opioid Treatment Programs in an Era of Increasing Opioid Addiction, Health Reform, and Parity.

- Umbricht-Schneiter A., Ginn D. H., Pabst K. M., Bigelow G. E. (1994). Providing medical care to methadone clinic patients: Referral vs on-site care. American Journal of Public Health, 84(2), 207–210. 10.2105/AJPH.84.2.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (2019). U.S. Code of Federal Regulations p.p. 11-18. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2018-title42-vol1/xml/CFR-2018-title42-vol1-part8.xml

- White A. G., Birnbaum H. G., Mareva M. N., Daher M., Vallow S., Schein J., Katz N. (2005). Direct costs of opioid abuse in an insured population in the United States. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, 11(6), 469–479. 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.6.469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright T. E. (2019). Integrating Reproductive Health Services Into Opioid Treatment Facilities: A Missed Opportunity to Prevent Opioid-exposed Pregnancies and Improve the Health of Women Who Use Drugs. Journal of addiction medicine, 13(6), 420–421. https://journals.lww.com/journaladdictionmedicine/Fulltext/2019/12000/Integrating_Reproductive_Health_Services_Into.2.aspx https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerden L. d. S., Cooper Z., Sanii H. (2021). The primary care behavioral health model (PCBH) and medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD): Integrated models for primary care. Social Work in Mental Health, 19(2), 186–195. 10.1080/15332985.2021.1896626 [DOI] [Google Scholar]