Abstract

In recent years direct ownership of physician practices by hospitals and health systems (that is, vertical integration) has become a prominent feature of the US health care system. One unexplored impact of vertical integration is the impact on referral patterns for common diagnostic tests and procedures and the associated spending. Using a 100 percent sample of 2013–16 Medicare fee-for-service claims data, we examined whether hospital and health system ownership of physician practices was associated with changes in site of care and Medicare reimbursement rates for ten common diagnostic imaging and laboratory services. After vertical integration, the monthly number of diagnostic imaging tests per 1,000 attributed beneficiaries performed in a hospital setting increased by 26.3 per 1,000, and the number performed in a nonhospital setting decreased by 24.8 per 1,000. Hospital-based laboratory tests increased by 44.5 per 1,000 attributed beneficiaries, and non-hospital-based laboratory tests decreased by 36.0 per 1,000. Average Medicare reimbursement rose by $6.38 for imaging tests and $0.57 for laboratory tests, which translates to $40.2 million and $32.9 million increases in Medicare spending, respectively, for the entire study period. This study highlights how the growing trend of vertical integration, combined with differences in Medicare payment between hospitals and nonhospital providers, leads to higher Medicare spending.

Vertical integration, or the direct ownership of physician practices by hospitals and health systems, has become a prominent feature of the US health care system, especially in recent years.1–6 This trend has not occurred without controversy. Proponents argue that the vertical integration of hospitals and physicians leads to efficiency gains via improved care coordination and simplified payments across different providers, along with other means. Yet many researchers, industry stake-holders, and regulators suspect that strategic motivations, such as greater contract leverage with insurers and differences in payment rates between different sites of care, are the driving force behind vertical integration.7 These contrasting—although not mutually exclusive—views of greater physician-hospital alignment have spurred a growing body of empirical studies and ongoing policy debates.

Recent studies have found increases in health care prices, spending, and treatment intensity after physicians and other providers become integrated with hospitals and health systems, with additional evidence supporting changes in referral patterns and choices of care settings.8–14 Conversely, improvements in care delivery quality or efficiency have proved difficult to detect.12,15–18 Two domains of health services less extensively studied within this strand of literature are diagnostic imaging and laboratory testing. The more limited attention paid to these areas is perhaps unsurprising because they are not therapeutic or typically high-stakes services (that is, associated with considerable morbidity or mortality risks). At the line-item level, imaging and laboratory services are also not particularly expensive when compared with other types of medical care (for example, chemotherapy or surgery), but these ancillary services are quite common. Just within the Medicare program, 194 million diagnostic images and and 679 million laboratory tests were performed in 2016 alone, representing $16.0 billion and $8.9 billion in spending, respectively (authors’ calculations). The high volumes— and hence spending—attached to these services have led some insurers and employers to seeks ways to lower their overall payments (for example, through price transparency tools and reference pricing).19

Consumer-focused initiatives have had mixed success in increasing the use of lower-price providers,20–25 in part because of the apparent influence of the referring physician.26 This latter element raises the immediate question of why a given physician would steer a patient toward a more expensive diagnostic provider, especially when the patient’s convenience is equivalent across provider options or even better with the lower-cost alternative.26 Many factors are possible for a given physician-patient interaction, but one potentially broad influence with growing contemporary importance is the physician’s employer. Independently practicing physicians may have little or no direct interest in the ultimate destination of an imaging or laboratory referral, but the same is not necessarily true of vertically integrated physicians. The hospital or health system owner of the practice has a clear financial stake in the care delivered by the employed physician, as well as any related ancillary services. In fact, Michael Chernew and colleagues’ 2019 study using claims data from a large commercial insurer found that patients treated by a vertically integrated orthopedic physician are more than twice as likely to be referred to hospital-based imaging for lower-limb magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans—and also pay more for them.26

A closely related but currently unanswered question is how vertical integration between hospitals and physicians affects where patients receive common diagnostic tests and associated spending for Medicare beneficiaries. Changes in where patients receive tests can take place through changes in referral patterns and reclassifications of facilities after changes in ownership. Reductions in the use of independent and nonhospital providers after vertical integration raises potential concerns about the ability of independent testing providers to enter the market or remain competitive.27 At the same time, recent work has found that differences in Medicare site-based payments contribute to the vertical integration of physicians.28

In this study we used the universe of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiary claims activity during the period 2013–16 and longitudinal analyses to empirically examine how site of care and Medicare payments for diagnostic tests are related to changes in vertical integration status across all US physicians who contract with Medicare. We examined the association between vertical integration of a patient’s primary care physician practice with hospitals or health systems and the sites of care for common diagnostic services and Medicare reimbursement rates. The findings document how vertical integration leads to changes in site of care for common tests and how, when combined with Medicare’s site-based payment differentials, these changes in procedure location lead to changes in Medicare payments. This finding offers new considerations for Medicare administrators and policy makers as they continue to navigate the difficult tension between incentivizing clinical integration and restraining the undesirable impacts of greater industry consolidation.

Study Data And Methods

DATA SOURCES

Our goal was to estimate the association between vertical integration of a Medicare beneficiary’s primary care practice group and outcomes related to referral patterns. Although existing work has examined the association between referrals and the integration status of the referring physician, the impact of the integration status of the physicians who provide a patient’s primary care has not been examined.6,8,9 To do so, we used several sources of administrative data to link physicians to physician groups, Medicare beneficiaries to physician groups, and physician groups to hospitals and health systems. A full description of the linkage procedure is in the appendix, and the steps are summarized below.29

We first used data from the Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty file to link individual providers to physician groups. For each individual National Provider Identifier, this data source identifies the group practice under which the provider is affiliated. Groups can comprise one or several physicians. We supplemented the Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty data with algorithms developed by the RAND Center of Excellence on Health System Performance. As described in the appendix,29 these data measure affiliation for academic and other physician groups that are not linked in the Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty data.

We then used data from a 100 percent sample of Medicare fee-for-service claims data to link Medicare beneficiaries to the physician groups where beneficiaries received their primary care services. Details of this linkage are also described in the appendix.29 Next, we used data from the Medicare Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System and IRS Form 990 tax forms to measure vertical integration between physician groups and hospitals or health systems. We defined vertical integration as ownership or management of a physician group by a hospital or health system. We did not consider looser affiliations such as open physician-hospital organizations, joint ventures, and independent practice associations.11,30

Finally, we used 2013–16 medical claims data from a 100 percent sample of Medicare beneficiaries to identify the site of care and Medicare reimbursement rates for five common diagnostic imaging (computed tomography and MRI scans) and five laboratory test procedures. The procedure codes used to identify these tests and the mean Medicare payment rates for hospital and nonhospital settings are in appendix exhibit 1.29 For each diagnostic imaging and laboratory test claim, we identified the number of procedures per 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries attributed to a physician group that were performed in hospital and nonhospital sites of care. Sites of care were identified using place-of-service codes (11, office; 19, off-campus outpatient hospital; 22, on-campus outpatient hospital; 49, independent clinic; and 81, independent laboratory). We also identified the total Medicare reimbursement amount, which consists of the amount paid by Medicare and by the patient in the form of cost sharing, summing to add up to total spending (that is, the claim’s “allowed amount”). Potential changes in Medicare reimbursement are driven by site-of-care differences in the Medicare facility fee schedule.

Our final sample included 818,546 individual health care providers affiliated with 88,127 physician groups. Our diagnostic test data included 29.5 million imaging and 341 million laboratory test procedures, which represent $8.7 billion and $4.9 billion in Medicare spending, respectively (appendix exhibits 4 and 5).29 For computational reasons, we grouped the claim-level data to the level of the physician group, procedure, year, and month.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We assessed the association between vertical integration of physician groups and the site-of-care and Medicare reimbursement endpoints using multivariable difference-in-differences regressions. Difference-in-differences regression analysis compares changes between a treatment group (in this case, providers that changed ownership status and moved from nonintegrated to integrated) with changes in a comparison group (in our case, providers that were never vertically integrated or were always vertically integrated).31 We further included fixed-effects controls for each physician group. Thus, our regression analyses measured the change in outcomes after integration, relative to the same physician group before integration and relative to groups that did not change integration status. To control for temporal differences, we included fixed-effects controls for calendar year and month and included procedure fixed effects to control for differences between specific tests.

To assess these associations from the perspective of the typical patient, we weighted the provider-specific observations by procedure volume. All regression models were estimated using linear regressions. We also included controls for calendar year and month to remove the impacts of time differences. Standard errors were clustered at the medical group and year level.32 All analyses were estimated using Stata, version 16. This project was approved by RAND’s Institutional Review Board.

SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

To test the validity of our results, we conducted several sensitivity tests. First, we used an event study approach to test for differences in trends in outcomes that occurred before vertical integration. Finding evidence of preintegration trends would suggest that factors other than vertical integration explain our observed differences. We also estimated models that tested the sensitivity of our included control variables by iteratively adding each control. To test the impact of weighting by provider volume, we estimated models that did not include volume weights. We also separately estimated results for each specific imaging and laboratory test procedure to examine whether our results were consistent across procedures.

LIMITATIONS

Our study was not without limitations. First, our analysis was limited to the Medicare fee-for-service population. Medicare fee-for-service prices are set administratively, whereas prices for commercial payers are set through complex negotiations. In addition, we considered the impacts for only ten common diagnostic tests. The same incentives exist for other downstream services for which physicians refer patients (for example, other diagnostic tests and surgical procedures); future research should consider the impacts of vertical integration on these procedures. We selected diagnostic imaging and laboratory tests to limit our analysis to procedures with little quality variation; other, more intensive services, have wider variations in quality. Other research has found that hospital consolidation does not appear to lead to improvements in quality outcomes.18 Future research should examine whether vertical integration affects the quality of patient care.

Also, we did not consider changes in ownership for testing centers or facilities. Some hospital-based lab or imaging centers might not be owned by a hospital, but there may be a financial arrangement between the center and the hospital. Future studies should consider the impact of these financial arrangements. Finally, physician groups facing difficult financial situations or with close relationships with hospitals or health systems may be both more likely to merge and also have different behaviors.

Study Results

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDY POPULATION

Exhibit 1 presents descriptive statistics for the study population. Our study sample included 29.5 million imaging procedures from 13.3 million unique Medicare beneficiaries and 341.4 million laboratory tests from 16.9 million Medicare beneficiaries. At the provider-procedure-month level that we used as the unit of analysis, there were 9.0 million observations for imaging tests and 17.6 million observations for laboratory tests. Among physician groups not vertically integrated with a hospital or health system, 67.9 percent of imaging tests were performed in hospital-based facilities, compared with 76.9 percent for vertically integrated physicians. For laboratory tests, the respective percentages were 53.6 percent and 61.2 percent. Mean per procedure payments were $291.0 and $307.4 for imaging tests performed by independent and integrated physicians, respectively, compared with $14.0 and $16.1 for laboratory tests among independent and integrated physicians, respectively.

Exhibit 1.

Characteristics of the study population, by type of procedure and the vertical integration status of physician group practices, 2013–16

| Independent physicians |

Integrated physicians |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Mean/number | SD | Mean/number | SD |

| IMAGING TESTS | ||||

| Hospital-based share (%) | 67.9 | 36.8 | 76.9 | 25.9 |

| Medicare spending amounta ($) | 291.0 | 158.6 | 307.4 | 154.4 |

| Number of observationsb | 8,472,312 | —c | 547,329 | —c |

| Number of patients | 10,273,507 | —c | 3,055,382 | —c |

| Number of procedures | 23,203,571 | —c | 6,294,305 | —c |

| LABORATORY TESTS | ||||

| Hospital-based share (%) | 53.6 | 39.6 | 61.2 | 35.1 |

| Medicare spending amounta ($) | 14.0 | 6.5 | 16.1 | 9.4 |

| Number of observationsb | 16,957,889 | —c | 655,996 | —c |

| Number of patients | 11,392,161 | —c | 5,473,899 | —c |

| Number of procedures | 283,544,892 | —c | 57,820,793 | —c |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare fee-for-service claims data, 2013–16. NOTES “Integrated physicians” are those whose practices have been acquired by a hospital or health system. SD is standard deviation.

Per procedure.

Number of observations at the year-month-procedurephysician group level.

Not applicable.

UNADJUSTED TRENDS IN INTEGRATION

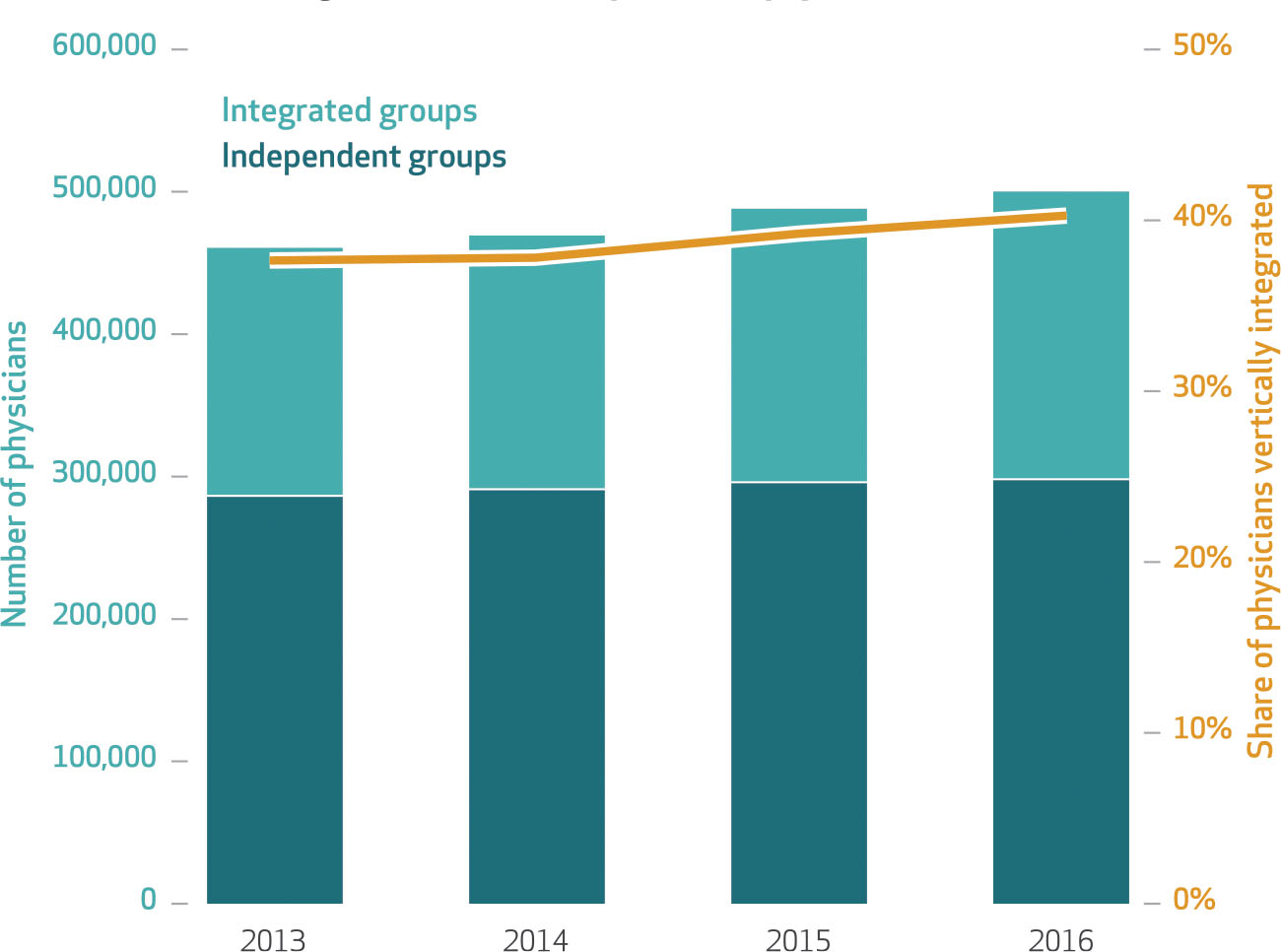

Consistent with previous studies, we observed increases in vertical integration of physician groups with hospitals and health systems during our study period (exhibit 2). During the 2013–16 period, the number of physicians who practiced in groups owned by a hospital or health system increased by 16.2 percent, from 173,410 in 2013 to 201,478 in 2016. The number of physicians practicing in a nonintegrated group increased as well, but a slower rate, from 287,271 in 2013 to 298,808 in 2016. After these two growth rates were combined, there was a 7.0 percent increase in the relative share of physicians working for a vertically integrated group.

EXHIBIT 2. Trends in vertical integration between hospitals and physicians, 2013–16.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare fee-for-service claims data. NOTE This figure shows annual trends in the number (left axis) and share (right axis) of physicians who work for an independent versus a vertically integrated physician group (that is, one that has been acquired by a hospital or health system).

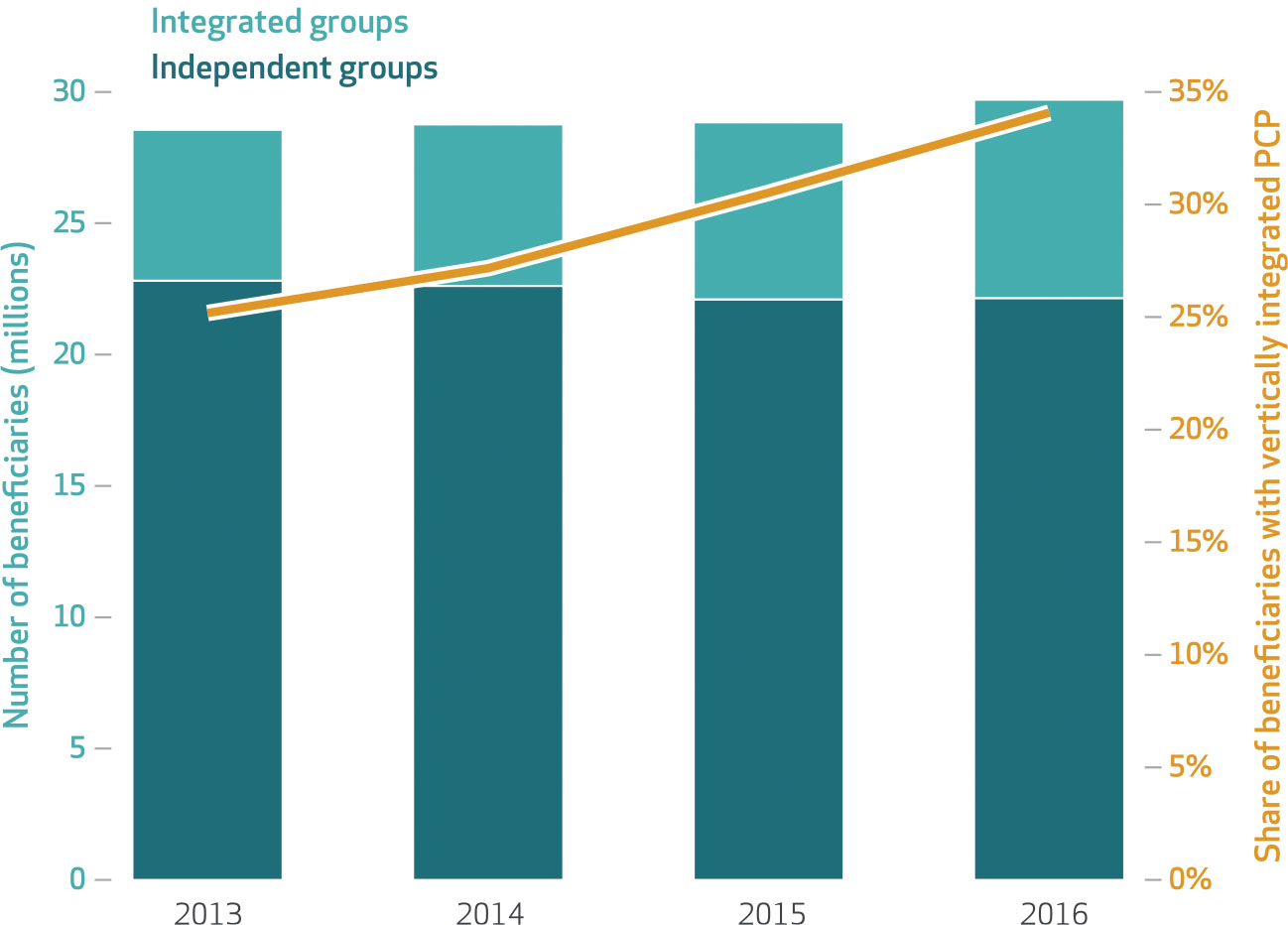

The number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who received primary care from a non–vertically integrated group decreased during the study period, from 22.8 million in 2013 to 22.2 million in 2016 (exhibit 3). Conversely, the number of beneficiaries who received primary care from a vertically integrated group increased by 1.8 million, from 5.8 million in 2013 to 7.6 million in 2016. Combining these two rates shows a 26 percent relative increase in the number of beneficiaries who receive primary care from a vertically integrated group. This rate is larger than the relative increase for physician groups, implying that physician groups that vertically integrated during this period are larger in size, as measured by the number of beneficiaries treated, than groups that did not integrate.

EXHIBIT 3. Trends in the number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with a vertically integrated primary care provider, 2013–16.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare fee-for-service claims data. NOTES This figure shows annual trends in the number (left axis) and share (right axis) of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who are attributed to an independent or a vertically integrated physician group (that is, one that has been acquired by a hospital or health system). PCP is primary care provider.

VERTICAL INTEGRATION AND SITE OF CARE

After vertical integration, the monthly number of imaging tests performed in hospital sites of care increased by 26.3 procedures per 1,000 attributed beneficiaries (exhibit 4). The number of procedures performed in nonhospital sites of care decreased by 24.8 procedures per 1,000 attributed beneficiaries. Thus, the total number of procedures performed increased slightly, by 1.5 procedures per 1,000 attributed beneficiaries. The number of laboratory tests performed in hospital settings increased by 44.5 per 1,000 attributed beneficiaries, and the number of tests performed in nonhospital settings decreased by 36.0 per 1,000 attributed beneficiaries. Thus, the total volume of laboratory tests increased by 8.5 per 1,000 attributed beneficiaries.

Exhibit 4.

Association of vertical integration of physician groups with site of care and with Medicare spending for diagnostic imaging and laboratory tests

| Change in response variable | Imaging tests | Laboratory tests |

|---|---|---|

| Number of procedures per 1,000 beneficiaries | 1.50** | 8.46*** |

| Number of hospital-based procedures per 1,000 beneficiaries | 26.30*** | 44.45*** |

| Number of non-hospital-based procedures per 1,000 beneficiaries | −24.80*** | −35.98*** |

| Medicare reimbursement after vertical integration ($) | 6.38*** | 0.57*** |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare fee-for-service claims data, 2013–16. NOTES Exhibit presents regression results that measure the association between vertical integration and the number of services per 1,000 attributed Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, the number that occur in a hospital site of care, the number that occur in a nonhospital site of care, and per test Medicare reimbursement amounts. The imaging tests column presents results for five imaging tests, and the laboratory tests column presents results for five laboratory tests. Regression models were estimated using linear regressions and include fixed-effects controls for year, month, procedure code, and physician group. Regression models were weighted by volume at the year-month-procedure-physician group level.

p < 0:05

p < 0:01

VERTICAL INTEGRATION AND REIMBURSEMENT RATES

Changes in site of care are reflected in Medicare reimbursement rates (exhibit 4). After vertical integration, there were per procedure increases of $6.38 for imaging tests and $0.57 for laboratory tests—relative increases of 2.0 percent and 3.8 percent, respectively. Across all services performed during the period examined and among our sample, these increases translated to increases of $40.2 million and $32.9 million in Medicare spending, respectively (appendix exhibits 4 and 5).29 After changes in procedure volume were accounted for, these increases in spending translated to increases of 4.3 percent and 4.5 percent in the studied imaging and laboratory tests, respectively.

SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

Overall, our sensitivity tests (that is, event studies) that measured trends in two of the primary outcomes—the number of services performed in hospital sites of care and Medicare reimbursement amounts—support our inferences from exhibit 4. For imaging tests, we did not observe preintegration trends for the number of services performed in a hospital site of care or Medicare spending changes before vertical integration (appendix exhibit 3).29 Instead, the increase in each outcome materialized immediately after vertical integration. For laboratory tests, we did not find preintegration trends for Medicare spending changes, but we did observe some increasing trends in hospital-based care, which accelerated after vertical integration.

In our other sensitivity tests, we found larger associations when estimating more parsimonious models that did not include fixed effects for physician groups (appendix exhibits 4 and 5).29 The more parsimonious models imply increases in Medicare spending of $105.1 million for imaging tests and $130.5 million for laboratory tests. Our results for the specific procedures were similar to the results that pooled procedures (appendix exhibits 6 and 7).29 Finally, we also obtained similar results when not weighting by physician group volume, where we observed spending increases of $90.1 million for imaging tests and $76.8 million for laboratory tests (appendix exhibits 8 and 9).29

Discussion

We found that during the 2013–16 period, vertical integration between physician group practices and hospitals or health systems was associated with increases both in hospital sites of care for common diagnostic imaging and laboratory tests and in Medicare reimbursement rates. The practice-level changes were sharp and materialized immediately after the ownership change. Contrary to claims of clinical efficiencies, we also observed increased rates of testing procedures.

Our results therefore support the empirical patterns and inferences from Chernew and colleagues26 and Caroline Carlin and colleagues9 with respect to vertical integration’s influence over where diagnostic tests ultimately take place. However, our contribution benefited from a longitudinal and comprehensive look at the full Medicare program over several more recent years. Carlin and colleagues’ study, for example, relied on an integration event from the previous decade and a narrow geographic scope (that is, Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota).9

Although the per procedure spending increases were somewhat modest, the procedures we studied are high volume. The shift toward hospital sites of care that we documented translates to increased Medicare fee-for-service spending of $73.1 million for the ten selected imaging and laboratory testing services during the four-year period.

Importantly, it is difficult to argue that the additional spending is related to better quality of care, as these specific services are likely to be highly standardized—and hence undifferentiated—across diagnostic providers. The increased payment is instead a reflection of pre-existing Medicare payment rates that reimburse hospitals more for these services than they reimburse competing providers (for example, stand-alone imaging centers and freestanding diagnostic laboratory companies). These findings also align with other related work. For example, Cory Capps and colleagues show that roughly half of the postintegration overall (commercial payer) physician price increase they observed was a by-product of exploitable and pre-existing payment rules.2 As a consequence, our results underscore the need for greater attention by policy makers to payment disparities across care delivery settings; the resulting perverse incentives engendered by those disparities; and potential corrective actions the Medicare program could take, such as site-neutral payment policies. Despite opposition from hospital groups, Medicare has moved to site-neutral payment polices for clinic visits.33

Hospitals and health systems have a strong financial interest in capturing the referral patterns of physicians, especially those they employ.1 These incentives and downstream outcomes can sometimes be at odds with patients’ best interests, however. For instance, a study by Laurence Baker and colleagues found evidence of strategic steering of hospital admissions after a physician practice had been bought.8 Importantly, the owning hospitals that drive these changes are often of lower quality and higher cost than their surrounding peers. Within our context, Medicare beneficiaries and US tax-payers bear a heavier cost burden for extremely common and largely uncomplicated services once vertical integration takes hold of a physician practice. Future studies should examine the impact of vertical integration’s changes in referral patterns on the resulting changes in horizontal market structure and competition between hospitals and independent testing providers.

Our study adds to the growing literature around the impacts of vertical integration. Our findings admittedly do not rule out potential positive impacts of vertical integration along other clinical dimensions, but they do highlight an example of where long-standing reimbursement practices likely require review and refinement in light of evolutions within the contemporary US health care marketplace. Beyond the consequences of vertical integration, researchers and policy makers have also taken an interest in the drivers of vertical integration. Attractive payment policies that change financial incentives and encourage greater consolidation, such as accountable care organizations and bundled payment, are thought to be an influential force.34–37 Our results echo the sentiments from prior studies and also encourage further research in these areas. Medicare administrators and industry regulators seem likely to face more, rather than less, vertical integration in the coming years. They will need a collage of evidence, including studies that examine other services, payers, and outcomes, to support the inevitable—and potentially contentious—decisions that are likely to follow.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through the RAND Center of Excellence on Health System Performance, which is funded through a cooperative agreement (No. 1U19HS024067–01 to Christopher Whaley, Xiaoxi Zhao, and Cheryl Damberg) with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Additional support was provided by the National Institute on Aging (Grant No. 1K01AG061274 to Whaley). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Denis Agniel, Sarah Edgington, and Mark Totten provided helpful data assistance.

Contributor Information

Christopher M. Whaley, RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California..

Xiaoxi Zhao, Department of Economics, Boston University, in Boston, Massachusetts..

Michael Richards, Baylor University, in Waco, Texas..

Cheryl L. Damberg, RAND Corporation in Santa Monica..

NOTES

- 1.Kocher R, Sahni NR. Hospitals’ race to employ physicians—the logic behind a money-losing proposition. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1790–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capps C, Dranove D, Ody C. The effect of hospital acquisitions of physician practices on prices and spending. J Health Econ. 2018;59:139–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neprash HT, Chernew ME, Hicks AL, Gibson T, McWilliams JM. Association of financial integration between physicians and hospitals with commercial health care prices. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1932–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikpay SS, Richards MR, Penson D. Hospital-physician consolidation accelerated in the past decade in cardiology, oncology. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1123–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards MR, Nikpay SS, Graves JA. The growing integration of physician practices: with a Medicaid side effect. Med Care. 2016;54(7):714–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brot-Goldberg ZC, de Vaan M. Intermediation and vertical integration in the market for surgeons. Berkeley (CA): University of California Berkeley; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Post B, Buchmueller T, Ryan AM. Vertical integration of hospitals and physicians: economic theory and empirical evidence on spending and quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2018; 75(4):399–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Kessler DP. The effect of hospital/physician integration on hospital choice. J Health Econ. 2016;50:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlin CS, Feldman R, Dowd B. The impact of hospital acquisition of physician practices on referral patterns. Health Econ. 2016;25(4):439–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch TG, Wendling BW, Wilson NE. How vertical integration affects the quantity and cost of care for Medicare beneficiaries. J Health Econ. 2017;52:19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Kessler DP. Vertical integration: hospital ownership of physician practices is associated with higher prices and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):756–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuellar AE, Gertler PJ. Strategic integration of hospitals and physicians. J Health Econ. 2006;25(1):1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konetzka RT, Stuart EA, Werner RM. The effect of integration of hospitals and post-acute care providers on Medicare payment and patient outcomes. J Health Econ. 2018;61:244–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson JC, Miller K. Total expenditures per patient in hospital-owned and physician-owned physician organizations in California. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1663–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns LR, Goldsmith JC, Sen A. Horizontal and vertical integration of physicians: a tale of two tails. Adv Health Care Manag. 2013;15:39–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlin CS, Dowd B, Feldman R. Changes in quality of health care delivery after vertical integration. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1043–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott KW, Orav EJ, Cutler DM, Jha AK. Changes in hospital-physician affiliations in U.S. hospitals and their effect on quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaulieu ND, Dafny LS, Landon BE, Dalton JB, Kuye I, McWilliams JM. Changes in quality of care after hospital mergers and acquisitions. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):51–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson JC, Brown TT, Whaley C. Reference pricing changes the “choice architecture” of health care for consumers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(3):524–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson JC, Whaley C, Brown TT. Association of reference pricing for diagnostic laboratory testing with changes in patient choices, prices, and total spending for diagnostic tests. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai S, Hatfield LA, Hicks AL, Chernew ME, Mehrotra A. Association between availability of a price transparency tool and outpatient spending. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1874–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desai S, Hatfield LA, Hicks AL, Sinaiko AD, Chernew ME, Cowling D, et al. Offering a price transparency tool did not reduce overall spending among California public employees and retirees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinaiko AD, Chien AT, Rosenthal MB. The role of states in improving price transparency in health care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):886–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whaley CM, Guo C, Brown TT. The moral hazard effects of consumer responses to targeted cost-sharing. J Health Econ. 2017;56:201–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whaley C, Brown T, Robinson J. Consumer responses to price transparency alone versus price transparency combined with reference pricing. Am J Health Econ. 2019;5(2):227–49. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chernew M, Cooper Z, Larsen-Hallock E, Morton FS. Are health care services shoppable? Evidence from the consumption of lower-limb MRI scans [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2018. Jul [last updated 2019 Jan; cited 2021 Mar 1]. (NBER Working Paper No. 24869). Available from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w24869 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richards MR, Seward J, Whaley CM. Treatment consolidation after vertical integration: evidence from outpatient procedure markets [Internet]. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation; 2020. Jul 6 [cited 2021 Mar 1]. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA621-1.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Post B, Norton EC, Hollenbeck B, Buchmueller T, Ryan AM. Hospital-physician integration and Medicare’s site-based outpatient payments. Health Serv Res. 2021; 56(1):7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 30.Robinson JC, Casalino LP. Vertical integration and organizational networks in health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 1996;15(1):7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimick JB, Ryan AM. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2401–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cameron AC, Miller DL. A practitioner’s guide to cluster-robust inference. J Hum Resour. 2015;50(2):317–72. [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Hospital Association v. Azar. 1:19-cv-03619 (DC Circuit). December 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheffler RM, Shortell SM, Wilensky GR. Accountable care organizations and antitrust: restructuring the health care market. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1493–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frech HE III, Whaley C, Handel BR, Bowers L, Simon CJ, Scheffler RM. Market power, transactions costs, and the entry of accountable care organizations in health care. Rev Ind Organ. 2015;47:167–93. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleiner SA, Ludwinski D, White WD. Antitrust and accountable care organizations: observations for the physician market. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(1):97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desai S, McWilliams JM. Consequences of the 340B Drug Pricing Program. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):539–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.