Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic health condition that affects the body’s ability to convert food into energy. People living with diabetes, as well as doctors and hospitals, struggle to handle the challenge. Among these challenges is that the field of diabetology is filled with bias. People living with diabetes will say that “diabetes does not define them,” yet they often refer to themselves as “diabetics.” Doctors are frequently “trained” to call people “diabetics,” and I am one of them.

Psychological consequences associated with diabetes and obesity bias and stigma have been previously reported. People with diabetes may experience stigma and may blame themselves for causing their condition. They may have restricted opportunities in life and being subject to negative stereotyping. Importantly, obesity stigma has been recognized as a barrier to comprehensive and effective type 2 diabetes management.

Electronic Health Records and the International Classification of Diseases are filled with diabetes-related bias. The word “diabetic” is frequently mentioned. Healthcare providers should recognize the person first, and not their medical condition.

Changing behavior takes time, especially as this is a collective phenomenon. This commentary proposes the steps needed to be taken to overcome the challenge of behavior change and offers a personal reflection on the subject.

Keywords: Bias, Diabetes, Stigma, Electronic health records, Electronic medical records, International classification of diseases

1. Background

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic health condition that affects the body’s ability to convert food into energy. More than 34 million adults in the United States have diabetes, and at least 20% of them do not know they have it.1 People with diabetes, as well as doctors and hospitals, struggle to address the challenge.2,3

The medical field of diabetology is filled with bias. I see a dozen patients a day who live and struggle with diabetes.4 I remember when one of my patients told me a few years ago: “Well, I am a diabetic. What do you want from me?” I responded: “You live with diabetes. And I am here to help you.” People living with diabetes say that “diabetes does not define me,” yet they often refer to themselves as “diabetics ”.5 Importantly, doctors are “trained” to label people as “diabetics” and I am one of them.

I was aware that I have been biased towards people who are disabled. And so I recently took the Implicit Association Test. This test measures the differential association of two or more target concepts with an attribute.6 My responses suggested a moderate automatic preference for abled persons over disabled persons. Just a few months ago, I gave a talk at a local community hospital about inpatient diabetes management. The talk was based on a slide Abbreviations: ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases deck and “talking points” that I had first presented more than six years ago. Frankly, I was surprised, and ashamed, to see the word “diabetic” mentioned on two slides. I thought I stopped using the word “diabetic” years ago. Moreover, one of my recent publications has the word “diabetic” in its title7 and I clearly remember consulting with the International Classification of Diseases before writing “Diabetic Ketoacidosis”.

2. Diabetes-related bias and stigma

Psychological consequences related to diabetes and obesity bias and stigma have been previously studied, however mental processes and cognitive biases that guide medical decision-making when treating patients with diabetes and obesity are not fully understood.8–14 Some people living with diabetes may experience negative feelings such as rejection, or blame due to the perceived stigmatization of having diabetes.15 Some people may position themselves or others with diabetes as “disobedient children, or as wicked or foolish adults”.14

Many persons with type 2 diabetes are obese and more than a third are discriminated against because of their weight.16 A cross-sectional study of 402 patients in Southern Brazil found that people with obesity may have been more vulnerable to therapeutic inertia related to the treatment of diabetes and obesity.8 Similarly, obesity stigma has been recognized as a barrier to comprehensive and effective type 2 diabetes management.13 Another group of researchers attempted to quantify and measure diabetes stigma and its associated psychosocial impact in 12,000 American patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes using an online survey.15 Authors found a “disturbingly high” percentage of people with diabetes who experience stigma (76% in people living with type 1 diabetes, and 52% in persons with type 2 diabetes), especially those who require intensive insulin therapy.15 A small qualitative study about perceptions of social stigma surrounding type 2 diabetes in Australia found that 84% of participants experience stigma and were feeling “blamed by others for causing their condition, having restricted opportunities in life and being subject to negative stereotyping”.11

3. Bias in the electronic health records and International Classification of Diseases

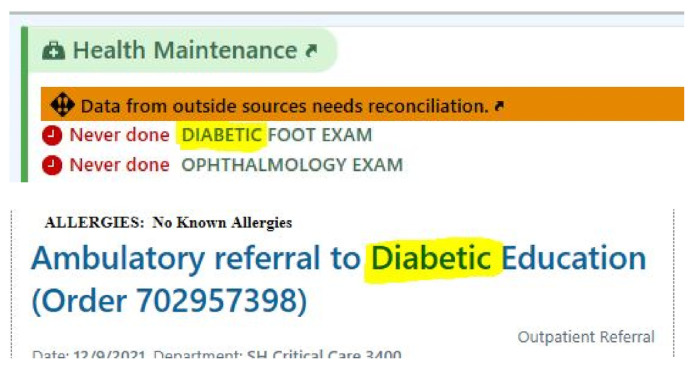

Electronic Health Records are filled with diabetesrelated bias (Fig. 1). The word “diabetic” is frequently used. Thousands of doctors, nurses and patients look at the screens of Electronic Health Records and may think “what’s on the screen is what is right.” Similarly, the word “diabetic” is found numerous times throughout the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (Fig. 2). A simple search of the word “diabetic” on the Center for Disease Control browser tool17 found 567 matches. Though it does attempt to redirect the reader from “diabetic hypoglycemia” to “Diabetes, hypoglycemia.” The World Health Organization owns and publishes the classification scheme. Who developed the ICD-10? It was developed by a Technical Advisory Panel: physician groups, clinical coders, and others.

Fig. 1.

Screenshot of the electronic health record.

Fig. 2.

Screenshot of the national center for health statistics ICD-10-CM Browser tool Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

4. Addressing implicit biases

It is important to put people first, not their disability. Weshould say “person with a disability,” rather than a “disabled person.” Similarly, in diabetology, doctors should recognize a human subject first, and not their medical condition. So why are so many health practitioners still using the word “diabetic”?

Our society has moved away from words such as “handicapped.” Similarly, doctors need to avoid labeling a person by disease. Instead of saying this is a “quadriplegic person,” we should say “this person has quadriplegia.” What can be done to change the culture associated with the word “diabetic” and inspire practitioners to recognize a person first?

5. Overcoming the challenge of behavior change

Changing behavior takes time, especially since this is a collective phenomenon.18 I am a diabetes expert and I lead a group of Endocrine Hospitalists at Johns Hopkins Medicine who manage thousands of people living with diabetes each year.4,19

Here, I outline the steps needed to overcome the challenge of culture change:

1. Raising self-awareness

We lead by example. While eliminating the word “diabetic” from our vocabulary may take time, making a conscious effort to say “a person living with diabetes” or “diabetes-related nephropathy” is quite doable. As for myself, I must revise all of my medical presentation slides and ensure that the word “diabetic” has been eliminated.

2. Strategy design and vision

As healthcare organizations (including Johns Hopkins Medicine) are working to inculcate concepts of diversity and inclusion in their organizational cultures,20 a simple proposal or a vision for why the word “diabetic” should be eliminated should be made.

3. Addressing Electronic Health Record bias

The designers of the Electronic Health Record should substitute the word “diabetic” with “diabetes- associated” or “diabetes-related.”

4. Addressing bias in the International Classification of Diseases

A letter, signed by leaders in the field of diabetes should be sent to the National Center for Health Statistics and World Health Organization, asking for a change. Participation in the Technical Expert Panel in the development of the next version of the International Classification of Diseases would be desireable.

5. Public support

Outreach to other leaders in the Johns Hopkins Health System (Chief Diversity Officers, Chief Medical Officers, Board members) asking for public support of the initiative to eliminate the word “diabetic,” even if this may be perceived as controversial.20

6. Educating and developing our staff and learners

I teach endocrinology fellows and internal medicine and pharmacy residents regularly. These future professionals are the ones who are going to lead the medical field in the next 30–40 years. Taking the time to explain the importance of inclusion and the primary recognition of a human soul (and not a person’s medical condition) may have life-long benefits.

5. Personal reflection

It is my role as an endocrinologist to “make this world a better place” for those who live with diabetes. As a leader, I must share my diversity, inclusion and health equity expertise with institutional leadership and beyond. As a healer, I have to find innovative models to engage all of the available resources so our healthcare system can achieve health equity for the most vulnerable populations, including those living with diabetes.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Funding source

None.

Conflict of interest

EMD Serono (consulting).

References

- 1.Control CfD, Prevention. National diabetes statistics report, 2020. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mandel SR, Langan S, Mathioudakis NN, et al. Retrospective study of inpatient diabetes management service, length of stay and 30-day readmission rate of patients with diabetes at a community hospital. J Commun Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9(2):64–73. doi: 10.1080/20009666.2019.1593782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Committee ADAPP. 16. Diabetes care in the hospital: standards of medical care in diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2021;45(Supplement_ 1):S244–S253. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zilbermint M. The endocrine hospitalist: enhancing the quality of diabetes care. J Diab Sci Technol. 2021 Jul;15(4):762–767. doi: 10.1177/19322968211007908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dickinson JK. Commentary: the effect of words on health and diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30(1):11–16. doi: 10.2337/ds15-0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(6):1464. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zilbermint M, Demidowich AP. Severe diabetic ketoacidosis after the second dose of mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine. J Diab Sci Technol. 2022 Jan;16(1):248–249. doi: 10.1177/19322968211043552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alessi J, de Oliveira GB, Erthal IN, et al. Diabetes and obesity bias: are we intensifying the pharmacological treatment in patients with and without obesity with equity? Diabetes Care. 2021;44(12):e206–e208. doi: 10.2337/dc21-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Puhl RM, Moss-Racusin CA, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Weight stigmatization and bias reduction: perspectives of overweight and obese adults. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(2):347–358. doi: 10.1093/her/cym052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity. 2009;17(5):941–964. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Browne JL, Ventura A, Mosely K, Speight J. ‘I call it the blame and shame disease’: a qualitative study about perceptions of social stigma surrounding type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open. 2013 Nov 18;3(11):e003384. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tak-Ying Shiu A, Kwan JJ, Wong RY. Social stigma as a barrier to diabetes self-management: implications for multilevel interventions. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(1):149–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Teixeira ME, Budd GM. Obesity stigma: a newly recognized barrier to comprehensive and effective type 2 diabetes management. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010 Oct;22(10):527–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Broom D, Whittaker A. Controlling diabetes, controlling diabetics: moral language in the management of diabetes type 2. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(11):2371–2382. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu NF, Brown AS, Folias AE, et al. Stigma in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Clin Diab. 2017;35(1):27–34. doi: 10.2337/cd16-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu YK, Berry DC. Impact of weight stigma on physiological and psychological health outcomes for overweight and obese adults: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(5):1030–1042. doi: 10.1111/jan.13511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Control CfD, Prevention. The national center for health statistics ICD-10-CM browser tool center for Disease Control and prevention. 2021. [Accessed 12/10/2021]. https://icd10cmtool.cdc.gov/

- 18. Hofstede G. Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Read Psychol Cult. 2011;2(1):2307. 0919.1014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Demidowich AP, Batty K, Love T, et al. Effects of a dedicated inpatient diabetes management service on glycemic control in a community hospital setting. J Diab Sci Technol. 2021 May;15(3):546–552. doi: 10.1177/1932296821993198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Mara J, Richter A. Global diversity and inclusion benchmarks: standards for organizations around the world. O’Mara and Associates; 2017. [Google Scholar]