Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

Background:

Telehealth was rapidly adopted early in the COVID-19 pandemic as a way to provide medical care while reducing risk of SARS-CoV2 transmission. Since then, telehealth utilization has evolved differentially according to subspecialty. This study assessed changes in neuro-ophthalmology during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

Telehealth utilization and opinions pre-COVID-19, early pandemic (spring 2020), and 1 year later (spring 2021) were surveyed among practicing neuro-ophthalmologists in and outside the United States using an online platform. Demographics, self-reported utilization, perceived benefits, barriers, and examination suitability were collected over a 2-week period in May 2021.

Results:

A total of 135 practicing neuro-ophthalmologists (81.5% United States, 47.4% females, median age 45–54 years) completed the survey. The proportion of participants using video visits remained elevated during COVID + 1 year (50.8%) compared with pre-COVID (6%, P < 0.0005, McNemar), although decreased compared with early COVID (67%, P < 0.0005). Video visits were the most commonly used methodology. The proportion of participants using remote testing (42.2% vs 46.2%), virtual second opinions (14.5% vs 11.9%, P = 0.45), and eConsults (13.5% vs 16.2%, P = 0.38) remained similar between early and COVID + 1 year (P = 0.25). The majority selected increased access to care, better continuity of care, and enhanced patient appointment efficiency as benefits, whereas reimbursement, liability, disruption of in-person clinic flow, limitations of video examinations, and patient technology use were barriers. Many participants deemed many neuro-ophthalmic examination elements unsuitable when collected during a live video session, although participants believed some examination components could be evaluated adequately through a review of ancillary testing or outside records.

Conclusions:

One year into the COVID-19 pandemic, neuro-ophthalmologists maintained telemedicine utilization at rates higher than prepandemic levels. Tele–neuro-ophthalmology remains a valuable tool in augmenting patient care.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated adoption of telehealth services previously limited by regulatory and financial barriers (1). In neuro-ophthalmology, telehealth utilization increased 17-fold during the first few months of the pandemic (2). A multicenter study found neuro-ophthalmology patient visits during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic to have shifted significantly toward telemedicine adoption (40% from 0%), with patients receiving telemedicine care more likely to be established with the provider (3).

The landscape that drove rapid uptake of telemedicine continues to shift. COVID-precipitated governmental lockdowns and medical care limitations have been replaced by local policies that aim to deliver safe medical care despite surges of new COVID variants. Simultaneously, governmental regulations expanding telemedicine usage have tightened (4) and reimbursement policies are forecasted to become more heterogeneous (5). Rates of telehealth utilization have shifted in a (sub)specialty dependent manner: in December 2020, a survey of all medical specialties found that neurology utilization of telehealth remained high (17% above baseline), whereas ophthalmology utilization had returned to prepandemic levels (6). Because neuro-ophthalmology intersects both specialties, this study aims to compare telehealth utilization by neuro-ophthalmologists during 3 periods (prepandemic, early COVID [defined as government-ordered shutdowns], and 1 year later) and to report perceptions of video telemedicine benefits, barriers, and utility after 1 year of use.

METHODS

This is a survey of neuro-ophthalmologists in independent clinical practice. Exclusion criteria were nonindependent practice (e.g., resident, fellow in training, or student) or inactive clinical practice (e.g., retirement). The population was sampled in a nonrandom fashion through an email sent to members of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society (NANOS), the largest organization in the world for the clinical subspecialty of neuro-ophthalmology, with 17% of members residing outside the United States. The study was deemed exempt by the Stanford Institutional Review Board. Participants were survey respondents who agreed to the parameters of the study and confirmed eligibility before proceeding with survey questions. No identifying information was collected.

Survey

Demographic questions included country of residence, state of residence for US participants, age category, sex, and board certification(s). Clinical practice questions included practice setting, proportion of income derived from clinical revenue, and electronic medical record (EMR) utilization; all of which were categorical (see Supplemental Digital Content, for full questions, http://links.lww.com/WNO/A616).

Participants were asked about use of synchronous (video visits) and asynchronous (remote interpretation of tests, second opinion reviews, eConsults, and others) telehealth utilization in their personal clinical practice before the COVID-19 pandemic (for US participants, before March 1, 2020), during the early COVID-19 pandemic (March–May 2020), and 1 year into the COVID-19 pandemic (March 1, 2021, through dates of the survey May 1–15, 2021). Participants who reported synchronous telemedicine (video visits) utilization were queried regarding benefits, while all participants were asked about barriers. All participants were asked to evaluate the suitability of physical examination or ancillary testing through video or performed separately by another provider to support medical decision-making.

The survey was implemented on a web-based platform (SurveyMonkey, San Mateo, CA) and distributed through email to members of NANOS using the organization's member listserv on May 1, 2021. Two additional reminders were sent. The survey was open from May 1 to 15, 2021.

Analysis

Responses to categorical survey questions are reported as proportions. Responses to numerical responses are reported as mean and 95% confidence interval. Responses to free text questions are reported qualitatively. Country of residence was collapsed to the United States and non-United States due to small numbers in most non-US countries. For US participants, states were grouped by US census regions (West, Midwest, South, and Northeast) for reporting purposes.

Change in utilization and availability for each telehealth modality was compared between pre-COVID and early COVID, pre-COVID and 1 year into COVID, and early COVID and 1 year into COVID using the McNemar test. P < 0.05 was the threshold for statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26 (IBM Inc, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Subjects

The survey invitation was delivered by email to 852 people (802 nontrainees). A total of 151 respondents agreed to participate. Ten respondents were not in current independent practice and 6 did not answer any questions beyond demographics. These were excluded from further analysis, leaving 135 participants (median age 45–54 years, 47% female) in the final analysis. The participants were mostly from the United States (81.5%), reflecting the membership distribution of the NANOS (84% United States), the organization through which the survey was distributed. We estimate that the US survey participants represent a 35% nonrandomized sample of the US-practicing neuro-ophthalmologists based on a recent report of 386 individuals in active neuro-ophthalmic clinical practice in the United States (7). Forty-eight percent of all survey participants reported completing the 2020 neuro-ophthalmology telehealth survey (22% did not recall, 13% did not participate, and 17% did not answer). A total of 208 respondents fully completed the 2020 survey with a similar distribution compared with 2021 survey respondents for geography, board certification, sex, and academic and government practice setting. In 2021, a smaller proportion of respondents were private solo/group-based and a greater proportion of respondents were private hospital-based compared with the 2020 survey (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Description of neuro-ophthalmologists in independent active clinical practice who participated in the survey

| Variable | Distribution (n = 135), n (%) |

| Country | |

| United States | 110 (81.5%) |

| Non-United States | 25 (18.5%) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Region (among US participants) | |

| West | 32 (29.1%) |

| Midwest | 31 (28.2%) |

| South | 24 (21.8%) |

| Northeast | 23 (20.9%) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Age (years) | |

| <35 | 11 (8.15%) |

| 35–44 | 44 (32.6%) |

| 45–54 | 29 (21.5%) |

| 55–64 | 30 (22.2%) |

| >65 | 21 (15.6%) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 64 (47.4%) |

| Male | 70 (51.9%) |

| Other | 0 |

| Missing | 1 |

| Board certification | |

| Ophthalmology | 85 (63.0%) |

| Neurology | 44 (32.6%) |

| Both | 5 (3.70%) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Practice setting | |

| Academic | 83 (61.5%) |

| Government | 8 (5.93%) |

| Private solo/group | 15 (11.1%) |

| Private hospital | 29 (21.5%) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Proportion of income derived from clinical revenue | |

| 0%–25% | 23 (17.0%) |

| 26%–50% | 16 (11.9%) |

| 51%–75% | 23 (17.0%) |

| >75% | 73 (54.1%) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Electronic medical record utilization | |

| Epic | 69 (43.7%) |

| Other (any EMR with n < 5) | 29 (21.4%) |

| Cerner | 7 (5.2%) |

| None | 7 (5.2%) |

| Missing | 23 (17.0%) |

EMR, electronic medical record.

Among included participants, ophthalmology background (63%) was more common than neurology (33%). Multiple practice environments were represented, with the majority (62%) in academic practice. Most participants (54%) derived more than 75% of their income from clinical revenue. Epic was the most commonly used EMR (66%), with 5% of participants reporting not using an EMR (see Supplemental Digital Content, Table 1, http://links.lww.com/WNO/A616).

All participants reported at least 1 change in practice operations during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2). Over 90% of participants' practices limited companions, enhanced cleaning, implemented personal protective equipment mandates for providers and patients, and added equipment changes (e.g., slit-lamp shields). Most participants offered some form of telehealth modality (73%) and decreased in person visit volume (53%). A minority implemented examination room changes (14%) (e.g., air filtration).

TABLE 2.

Changes to clinical practice due to COVID as reported by neuro-ophthalmologists in independent clinical practice

| Practice Modifications | Survey Participants Reporting Change, n (%) |

| Limits on patient companions | 131 (97.0%) |

| Enhanced cleaning protocols | 126 (93.3%) |

| PPE mandates for provider | 125 (92.6%) |

| PPE mandates for patients | 123 (91.1%) |

| Equipment changes (e.g., shields) | 123 (91.1%) |

| Decreased waiting room capacity | 114 (84.4%) |

| Offering telehealth (any modality) | 99 (73.3%) |

| Decreased in-person volume | 71 (52.6%) |

| Examination room changes (e.g., air filters) | 19 (14.1%) |

Participants were asked to select all that applied.

PPE, personal protective equipment.

Video Visits

Among participants who answered video visit utilization questions (n = 133), 70% reported video visit utilization during one of the surveyed periods. The most commonly used video telemedicine platforms were those integrated with their EMR (51%), Zoom (45%), or Doximity (22%) (see Supplemental Digital Content, Table 2, http://links.lww.com/WNO/A616). 10.4% reported lack of video visit availability during all periods, and 22% reported lack of provider interest in providing video visits during all 3 periods.

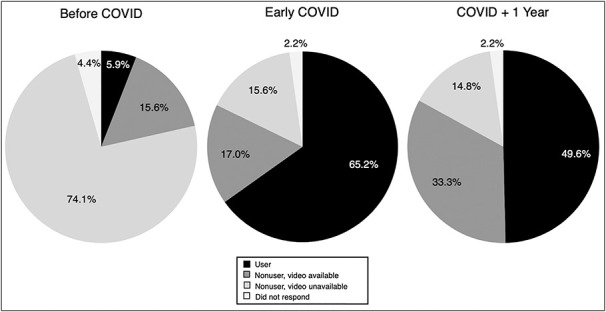

Video visit utilization increased in early COVID compared with pre-COVID (65% vs 6%, P < 0.0005, McNemar), in parallel with increased availability (82% from 21%) and increased interest (71% from 27%) (Fig. 1). Utilization declined slightly 1 year later (50%, P < 0.0005, McNemar vs pre-COVID and early COVID) in the setting of declining provider interest (56% from 71%) (Fig. 2) despite stable availability (82% early COVID and 83% COVID + 1 year). Utilization of video visits was higher in neurology-based respondents than ophthalmology-based respondents at all time points studied (P = 0.001 pre-COVID, P < 0.0005 early COVID, late COVID, Chi-square). Those participants performing video visits 1 year into COVID conducted a median of 2 video visits per week (range 0–50), which decreased, remained stable, or increased in 69%, 16.4%, and 13.4%, respectively, compared with early COVID. 82.1% planned to continue using video visits.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of practicing neuro-ophthalmologists' self-reported utilization of video visits before COVID, during early COVID, and 1 year into COVID. Each pie represents a period. Slice color indicates whether survey participants were using video visits during the period (black) or not (gray stratified by availability in their practice).

FIG. 2.

Utilization, availability, and provider desirability of telehealth modalities as reported by neuro-ophthalmologists in independent practice. For top 4 plots, each plot represents a distinct telemedicine modality. Each line shows the proportion of survey participants reporting utilization (solid), availability (dashed), and provider interest in (dotted) each telemedicine modality during each period. The bottom plot shows utilization only for 3 additional telemedicine modalities as reported by survey participants. Availability and provider interest were not surveyed for the modalities included on the bottom plot. Pre-COVID is before COVID-19 stay-at-home orders were enacted in each participant's place of practice (February 2020 in the United States). Early COVID is the month following stay-at-home orders in each participant's place of practice (March–April 2020 in the United States). One year COVID is 1 year after early COVID.

Most video users 1 year into COVID agreed with each proposed video visit benefit included in the survey (Fig. 3, upper). The benefits receiving the most support were increased access to care (95.5%), better continuity of care (94.0%), and enhanced patient appointment efficiency (88.1%). The benefits receiving the least support, decreases in overhead expenses and improved interprofessional communications (both 62.7%), were still perceived favorably by a substantial majority.

FIG. 3.

Perceived benefits and barriers to video telemedicine use selected by neuro-ophthalmologists in independent practice. Upper: Benefits reported by survey participants who offer video visits (n = 67) were asked to agree or disagree that each statement was a benefit. Lower: Barriers reported by survey participants (n = 119).

A total of 119 participants agreed with at least 1 proposed video visit barrier (Fig. 3, lower). The most commonly perceived barriers were limitations in types and quality of data collected (93.3%), patient technology barriers (93.3%), and difficulty with implementation (73.9%). A slim majority indicated institutional buy-in (52.9%) was not a barrier. There was no difference between current video users and nonusers in their perception of barriers except for reimbursement concerns, which was more commonly reported among video visit users (71.6% vs 52.3%, P = 0.001, Chi-square). Multiple participants noted video visits required significant time and effort invested by provider and staff that was not offset by patient utilization, workflow optimization, and/or medical utility.

Participants were queried about the suitability of video-based examination findings and previously collected data (e.g., through documentation by another provider or ancillary testing) to support medical decision-making. Most video-based examination findings were rated as sometimes or usually suitable by more than 50% of respondents. Confrontation visual fields (20.7%), ocular alignment (18.1%), and pupil examination (25.9%) had the highest proportion of “never suitable” responses. For review of previously collected data, visual field (15.5%), ocular alignment (16.4%), and pupil examination (18.1%) had the highest proportion of “never suitable” responses (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Practicing neuro-ophthalmologists’ opinions on suitability of data elements to support medical decision-making for care delivered through video visits, n = 116.

Remote Interpretation of Tests

Among participants responding to remote testing questions (n = 117), remote testing was performed by 32% before COVID, 43% during early COVID, and 46% 1 year into COVID. Forty-seven percent did not perform remote test interpretation across any period. Availability of remote testing increased over the 3 periods surveyed. The 54 participants performing remote test interpretations 1 year into COVID reported performing a median of 3 tests per week (range 0–100) which was increased for 20%, unchanged for 50%, and decreased for 24%. A majority performed interpretation of fundus photographs, OCT, and visual fields (see Supplemental Digital Content, Table 3, http://links.lww.com/WNO/A616). Most (81.5%) planned to continue performing remote test interpretations.

Virtual Second Opinions

Eight of the respondents (5.9%) reported performing virtual second opinions before COVID, significantly increasing to 16 (11.9%) during the early COVID period (P = 0.008, McNemar). Respondents performing virtual second opinions 1 year into COVID decreased slightly from early COVID levels to 13 (9.6%, P = 0.38, McNemar) (Fig. 1). Ninety-three (68.9%) did not perform virtual second opinions across any period. Seventy-one (52.6%) reported that virtual second opinions were unavailable to them during the study periods.

eConsults

Eight of the respondents (5.9%) reported performing eConsults before COVID, significantly increasing to 15 (11.1%) during the early COVID period (P = 0.016, McNemar). Respondents performing eConsults 1 year into COVID increased slightly from early COVID levels to 18 (13.3%, P = 0.25, McNemar), but at rates still significantly higher than pre-COVID levels (P = 0.002, McNemar) (Fig. 1). Ninety-three (68.9%) did not perform eConsults across any period. Sixty-five (48.1%) reported that eConsults were unavailable to them during the study periods. Sixty-five (48.1%) were not interested in performing eConsults in any of the 3 periods.

Telephone Visits

Twenty-four of the respondents (17.8%) indicated using telephone visits (as defined by the Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] codes 99441–99443) pre-COVID. This usage increased to 74 (54.8%) during the early COVID period and declined to 61 (45.2%) one year later.

Online Portal Communications

Fifty of the respondents (37.0%) indicated using online patient evaluation and management (as defined by the CPT codes 99421–99423) pre-COVID. This usage increased to 71 (52.6%) during the early COVID period and remained at similar levels (69, 51.1%) 1 year later.

Remote Interpretation of Patient Data

Twenty-four of the respondents (17.8%) indicated using remote interpretation of patient-submitted data (as defined by the CPT code G2010) pre-COVID. This usage increased to 45 (33.3%) during the early COVID period and remained at similar levels (43, 31.9%) 1 year later.

Comments on Tele–Neuro-Ophthalmology

Eleven (8.1%) provided additional comments. Five of the comments indicated negative views of using telehealth in neuro-ophthalmology (e.g., “I do not think telemedicine is ideal for neuro-ophthalmology”); of those negative comments, 2 were from respondents who did not use video telemedicine in any of the 3 periods, 2 used video telemedicine in the early COVID period but did not use it 1 year later, and 1 (20%) was from a respondent still currently using video telemedicine. Other comments reported challenges with adoption of eConsults over curbside consultation, limitations of remote clinical care, and struggles with institutional support.

CONCLUSIONS

This survey of practicing neuro-ophthalmologists characterized utilization and opinions regarding telehealth modalities 1 year into the COVID pandemic (before Delta and Omicron variant surges) compared with early COVID and before the pandemic. The results build on those from a previous survey of the same population during early COVID (2). Both surveys demonstrate rapid adoption of tele–neuro-ophthalmology during early COVID in parallel with, and likely facilitated by, increased availability. This survey reports slight decreases in telemedicine utilization and desirability 1 year into COVID compared with early COVID, although remaining above prepandemic levels. We also report perceived benefits and barriers to video visits and characterize neuro-ophthalmologists’ opinions regarding suitability of different telehealth data sources to support medical decision-making. Participant demographics were similar to the initial survey but with a lower response rate.

Neuro-ophthalmologists’ relative maintenance of telehealth utilization despite a collective reduction in telehealth use suggests that neuro-ophthalmic practice aligns more with neurology, which has continued telehealth utilization beyond the 1 year mark into the pandemic, than ophthalmology, which has essentially ceased telehealth (6). However, our data highlight broad heterogeneity among neuro-ophthalmologists, with 30% not performing video visits during any of the surveyed periods and varied video visit volumes between physicians. The persistence of extensive video visit use by nearly half of participants a year into the pandemic, even after in-person visits were allowed again, suggests the establishment of telehealth in neuro-ophthalmic care modalities.

In accordance with published expert opinions and our previous survey (2,8,9,10,11), many benefits and barriers were reported by video visit users. Positive responses to patient-centered benefits (access to care, continuity of care, and efficiency for the patient) support perceptions that telehealth lowers the barrier to entry for patients and facilitates follow-up appointments. Although provider accessibility increased in early COVID-19 and has sustained, patient technology barriers were reported by over 90% of survey participants. Suggested strategies to mitigate this include expansion of national broadband coverage, partnerships between underserved communities and internet service providers, increasing digital literacy, enforcing existing policies promoting internet access disparities, addressing language barriers and housing instability, and adopting a team-based care approach (12). Concerns regarding examination data limitations have previously been reported (2) and were affirmed again by 90% of participants. The survey further explored these concerns, asking about the suitability of different acquisition modalities (examination through video, referencing an in-person examination by another provider, and ancillary testing). As with utilization, suitability opinions were heterogeneously distributed. Notably, data collected outside the video visit were uniformly regarded as more suitable and that ancillary testing data had the highest reports of suitability. This suggests opportunities for strategies facilitating data collection for telehealth including home monitoring and virtual testing (13). Positive response to ancillary test suitability supports expansion of remote interpretation of testing. It is currently used by almost half of survey participants and has been shown to be safe and feasible (14).

Although most neuro-ophthalmologists who are using telehealth modalities plan to continue use, examination of reported barriers provides insights into what might affect sustainability. Reimbursement, which has been broadly available during the pandemic, may change by payer. Although it is recognized that telemedicine advances patient equity and access to care, US healthcare leaders remain uncertain about sustainability of telehealth should waivers cease and/or reimbursement decline (15).

The main limitations of this study relate to the survey methodology used (16). By collecting responses during the COVID-19 pandemic, recall bias was likely minimized. The nonrandomized sample with voluntary response likely biased toward overestimates of adoption given that those not interested likely had reduced rates of participation. Fifty-two percent of respondents from the current survey did not respond to the previous 2020 survey, which limits comparisons. Benefits and barriers not specifically queried were likely underestimated.

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

Conception and design: M. W. Ko, K. E. Lai, H. E. Moss; Acquisition of data: M. W. Ko, K. E. Lai, H. E. Moss; Analysis and interpretation of data: K. E. Lai H. E. Moss. Drafting the manuscript: M. W. Ko, K. E. Lai, H. E. Moss; Revising the manuscript for intellectual content: M. W. Ko, K. E. Lai, H. E. Moss. Final approval of the completed manuscript: M. W. Ko, K. E. Lai, H. E. Moss.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.jneuro-ophthalmology.com).

H. E. Moss and K. E. Lai contributed equally to this work.

Research to Prevent Blindness unrestricted grant to the Stanford Department of Ophthalmology, NIH P30 026877.

Contributor Information

Heather E. Moss, Email: hemoss@stanford.edu.

Kevin E. Lai, Email: kevin.e.lai@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B, Gellad ZF, Cho A, Philley D, Curtis S, Roman M, Poon EG, Ferranti J, Katz JN, Tcheng J. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss HE, Lai KE, Ko MW. Survey of telehealth adoption by neuro-ophthalmologists during the COVID-19 pandemic: benefits, barriers, and utility. J Neuroophthalmol. 2020;40:346–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss HE, Ko MW, Mackay DD, Chauhan D, Gutierrez KG, Villegas NC, Lai KE. The impact of COVID-19 on neuro-ophthalmology office visits and adoption of telehealth services. J Neuroophthalmol. 2021;41:362–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Telehealth Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs). Available at: https://edit.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-telehealth-frequently-asked-questions-faqs-31720.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Association of Family Physicians. Major Insurers Changing Telehealth Billing Requirement in 2022. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/journals/fpm/blogs/gettingpaid/entry/telehealth_pos_change.html. Accessed June 9, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehrotra A, Chernew C, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D, Schneider E. The Impact of COVID-19 on Outpatient Visits in 2020: Visits Remained Stable, Despite a Late Surge in Cases. Commonwealth Fund; [Internet]. 2021. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/feb/impact-covid-19-outpatient-visits-2020-visits-stable-despite-late-surge. Accessed June 9, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeBusk A, Subramanian PS, Scannell Bryan M, Moster ML, Calvert PC, Frohman LP. Mismatch in supply and demand for neuro-ophthalmic care. J Neuroophthalmol. 2022;42:62-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai KE, Ko MW, Rucker JC, Odel JG, Sun LD, Winges KM, Ghosh A, Bindiganavile SH, Bhat N, Wendt S, Scharf J, Dinkin MJ, Rasool N, Galetta SL, Lee AG. Tele-neuro-ophthalmology during the age of COVID-19. J Neuroophthalmol. 2020;40:292–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu YA, Ko MW, Moss HE. Telemedicine for neuro-ophthalmology: challenges and opportunities. Curr Opin Neurol. 2021;34:61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko MW, Busis NA. Tele-neuro-ophthalmology: vision for 20/20 and beyond. J Neuroophthalmol. 2020;40:378–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko MW, Lai KE, Mackay DD. Teleneuro-ophthalmology. Pract Neurol. 2020. [Magazine on the Internet]. Available at: https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2020-june/teleneuro-ophthalmology. Accessed March 30, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tierney AA, Kyalwazi MJ, Lockhart A. California Initiative for Health Equity & Action. Tackling the Digital Divide by Improving Internet and Telehealth Access for Low-Income Populations. Available at: tacklingthedigitaldivide.pdf(berkeley.edu). Accessed on January 7, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinod K, Sidoti PA. Glaucoma care during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021;32:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu TT, Kung FF, Lai KE, Ko MW, Brodsky MC, Bhatt MT, Chen JJ. Interprofessional electronic consultations for the diagnosis and management of neuro-ophthalmic conditions. J Neuroophthalmol. 2022. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyrda L, Drees J, Adams K. Becker's Hospital Review. Will Health Systems Sustain Telehealth If Pandemic Pay Rates, Coverage Drop? Available at: https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/telehealth/will-health-systems-sustain-telehealth-if-pandemic-pay-rates-coverage-drop.html Accessed January 8, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Draugalis JR, Coons SJ, Plaza CM. Best practices for survey research reports: a synopsis for authors and reviewers. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]