Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To investigate the in-depth pharma-cological mechanisms of celastrol in children neuro-blastoma treatment.

METHODS:

In the current study, we examined the effects of celastrol on children neuroblastoma cells viability and proliferation by cell counting kit-8 assay and colony formation assay. Annexin V-FTIC and PI staining were applied to determine cell apoptosis after celastrol treatment. ROS generation levels were examined by 2′, 7′-dichloroflfluorescin diacetate.

RESULTS:

We found that celastrol could suppress the proliferation of children neuroblastoma cells with few effects on normal cell lines in vitro. Further mechanisms studies have shown that celastrol inhibited cell cycle progression and induced cell apoptosis in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells. In addition, ROS production might involve in celastrol-mediated apoptotic cell death in children neuroblastoma cells by activating caspase death pathway.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our findings demonstrated that celastrol could promote ROS generation-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cell by activating caspase death pathway. These findings suggested that celastrol might be a potential novel anti-neuroblastoma agent with minor cytotoxicity.

Keywords: neuroblastoma, child, celastrol, apoptosis, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases

1. INTRODUCTION

Neuroblastoma is a common children malignancy which originating from the early developing embryonic sympathetic nervous system.1,2 It is one of the most commonly malignant tumor in children under twelve years old, which accounting for 16% of cancer-related deaths in children.3,4 Most of the neuroblastoma located in the adrenal medulla and along the sympathetic ganglia. Such as the chest, abdomen, neck and pelvis region.5

Surgery is the only radical treatment for localized neuroblastoma, however, it may lead to serious complications or even death for children.6,7 Despite the progression in multimodality therapy, the overall survival rate for children neuroblastoma is still poor. Thus, developing more effective and safe therapies are urgently needed for children neuroblastoma treatment.

Celastrol is a traditional Chinese herbal product, which is a pentacyclic triterpene monomer isolated from Leigongteng (Radix Tripterygii Wilfordii).8,⇓-10 Celastrol has shown great potential for treating obesity, inflammation and various malignancies, including breast cancer, prostate cancer, and lung cancer.11,12 As a novel anticancer agent, recent studies have shown that can induce specific cell death of cancers with few cytotoxicity in normal cells.13,14 However, there are few studies have focused on the potential anti-cancer effects of celastrol on children neuroblastoma cells. In the current study, the effects of celastrol on children neuroblastoma cells viability and proliferation were examined. Mechanically, ROS production may contribute to celastrol-mediated apoptotic cell death and tumor inhibition in children neuroblastoma. Our studies might provide novel insight into the anti‐neuroblastoma mechanisms of celastrol.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cell culture

Human neuroblastoma (SK-N-BE (2), SK-N-SH and SH-SY5Y) cell lines and human foreskin fibroblasts (CCD-1078SK, and BJ) cell lines were purchased from the RIKEN BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Japan). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) cells were kindly provided by prof. Cheng from University of Tianjin. Neuroblastoma cells were cultivated in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium and normal foreskin fibroblasts cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium. Streptomycin (0.2 mg/mL), Penicillin (80 U/mL), and FBS (10% v/v) were supplemented to the culture media. Cells were routinely cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Celastrol (purity ≥ 99%, HPLC-grade) was provided by Sigma and dissolved in 1 % dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

2.2. Cell viability assay

The cells were seeded into 96-well plates (5000 cells/well) with 3 replicates for each group at each time point. After 24 h incubation, 200 μL of medium containing 10% cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) (KeyGEN Biotech, Nanjing, China) was added to each well. The CCK-8 assay was applied to detect the cell viability following the manufacturer’s protocols.

2.3. Colony formation assay

The neuroblastoma cell lines QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y (600 cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates and treated with different concentration of celastrol. After incubated at 37 °C for 10 d, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution and stained with 1% crystal violet for 15 min. The colony numbers were counted by a light microscope. This experiment was performed in triplicate.

2.4. Cell-cycle analysis

For cell-cycle analysis, QDDQ-NMcells were seeded into 6-well plate at a density of 3 × 105 cells /well in DMEM culture medium. When cells were 75% confluent, they were pre-treated with different concentration of celastrol for 24 h. Then, cells were washed with PBS, and harvested by trypsinization and centrifuged for 10 min at 800 g. The cells were subsequently resuspended in 200 μL of staining solution containing 40 μg/mL RNase, 40 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI), 2 mg/mL sodium citrate, 0.2% Triton X-100, and distilled water. The cell cycle was examined by BD FACSCalibur™ (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) flow cytometry and the cells cycle distribution were analysed by Flowjo software (BD Bio sciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

2.5. Fluorescence microscopic study of apoptosis

After treatment with celastrol with or without NAC, the neuroblastoma cells were stained with Hoechst 33442 (Sigma, San Francisco, CA, USA) and visualized by a fluorescence microscopy to assess the morphological changes to the nuclei as a measure of apoptotic cell death.

Annexin V-FTIC and PI staining

Apoptosis was further verified by using Annexin VFITC/PI staining kit (Fuyuanbio, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In general, the neuroblastoma cells were washed by PBS and resuspended with 100 µL binding buffer. Then, 10 µL of Annexin V-FITC was added into 105 neuroblastoma cells (190 µL) and incubated for 15 min at 24 °C. Then, 100 µL of binding buffer were added for washing the cells before resuspending again. Finally, 15 µL of PI solution (10 µm) was added to the cells and subjected to the flow cytometry assay.

2.6. RT-PCR assay

RNA was extracted by TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, San Francisco, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA Synthesis Kit (TAKARA, Tokyo, Japan) were applied to synthesize the cDNAs from the total RNA samples extracted. The PCR assay was performed in 10 μL reaction solution (TAKARA, Tokyo, Japan) containing 15 nM of each primers and 2 μL cDNA templates. PCR assay was performed with a thermocycler (Biorad, San Jose, CA, USA). Finally, 2 μL of the PCR amplification products were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis.

2.7. Western blotting assay

Proteins expression was examined by Western blot assay. In general, the protein concentrations were examined by bicinchoninic acid disodium kit (BCA, San Jose, CA, USA). Then, the cell lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, San Francisco, CA, USA). The membranes were incubated with specific primary antibodies for 12 h at 4 °C, followed by incubation with related secondary antibodies. Proteins were visualized with chemiluminescence luminol reagents (Biorad, San Jose, CA, USA). The signal intensity of the protein band was analysed by Imagelab software.

2.8. Measurement of ROS generation

ROS generation levels were examined by 2′,7′-dichloroflfluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA; Sigma, San Francisco, CA, USA). 10 μM DCFH-DA was added into cells for 45 min after treatment with celastrol. Then, cells were washed with PBS for twice and fixed with formaldehyde for 20 min at 24℃. The cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) after washing with PBS. The green fluorescence indicated ROS productions in cells. For flow cytometry assay, cells were incubated with 15 μM DCFH-DA for 15 min after celastrol treatment. The fluorescence signal was examined by Accuri C6 FACS (BD Biosciences, San Francisco, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.9. Statistical analysis

SPSS 18.0 software (IBM, San Francisco, CA, USA) was applied to conduct the statistical analyses. For the comparison of two groups, Student's t test was used. For the comparison of more than two groups, one‐way analysis of variance were used. P-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Celastrol suppresses the proliferation of children neuroblastoma cell

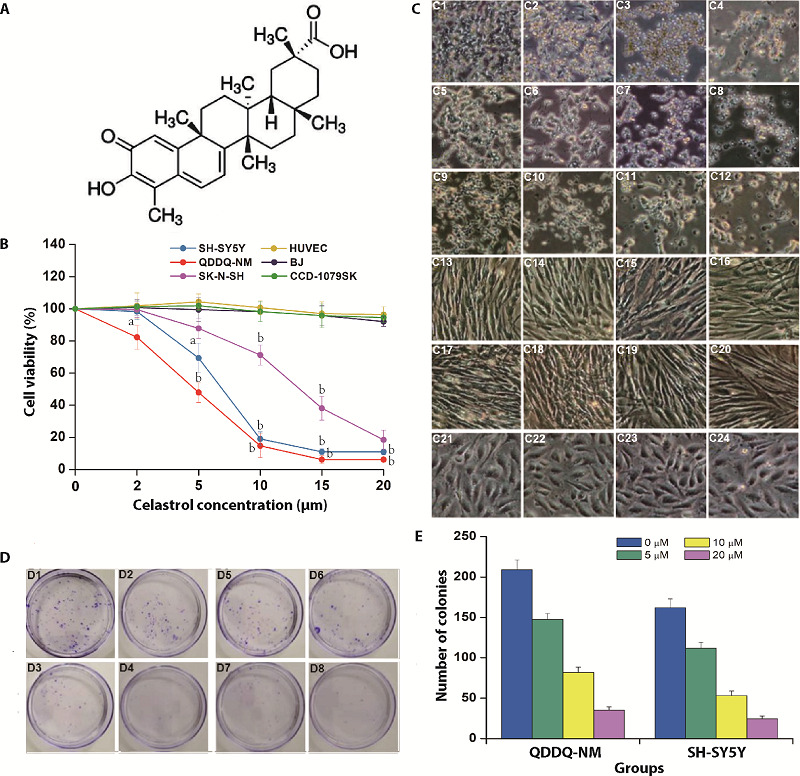

To explore the effects of celastrol on cell growth of children neuroblastoma, several neuroblastoma cell lines were applied in this study. QDDQ-NM, SH-SY5Y and SK-N-SH cells were derived from children mediastinum, bone and brain neuroblastoma, respectively. These cells were applied in our research and seeded in culture medium with different concentrations of celastrol for 1 day, then, CCK-8 assay was applied to exam the cells viability. Our results showed that celastrol remarkably suppressed all of these neuroblastoma cells’ viability dose-dependently (Figure 1B). In addition, 20 μM celastrol has few inhibition effects on three normal cell lines in our study (Figure 1B). Next, we observed the potential morphological changes of these cells after celastrol exposure. Our results indicated that celastrol could increase cells floating, reduce cells attachment and induce cells shrinkage (Figure 1C). Notably, SK-N-SH cell was less sensitive to celastrol exposure compared to SH-SY5Y and QDDQ-NM cells. Thus, SK-N-SH cell line was excluded in our following studies. Colony formation assay was applied to further verify the suppressive effects of celastrol on the QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells proliferation. Celastrol treatment significantly inhibited neuroblastoma cells colony formation dose-dependently (Figure 1D, 1E). In conclusion, above data indicated that celastrol might suppress the proliferation of neuroblastoma cells.

Figure 1. Celastrol inhibits cell viability and proliferation of neuroblastoma cells.

A: molecular structure of celastrol; B: QDDQ-NM, SK-N-SH and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell lines and three normal cell lines were incubated with different concentrations (0-20 µM) of celastrol, CCK-8 assay was applied to determine cells viability. aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01 versus 0 μM celastrol treatment group; C: C1-C4: QDDQ-NM cell lines were incubated with different concentrations (0-20 µM) of celastrol; C5-C8: SK-N-SH cells were incubated with different concentrations (0-20 µM) of celastrol; C9-C12: SH-SY5Y cells were incubated with different concentrations (0-20 µM) of celastrol; C13-C16: BJ cells were incubated with different concentrations (0-20 µM) of celastrol; C17-C20: CCD-1079SK cells were incubated with different concentrations (0-20 µM) of celastrol; C21-C24: HUVEC cells were incubated with different concentrations (0-20 µM) of celastrol, cell morphology changes were detected by optical microscope. Scale bar = 100 μm; D: colony formation results after celastrol treatment (0-20 µM) in QDDQ-NM (D1-D4) and SH-SY5Y cells (D5-D8). aP < 0.05; bP < 0.01; cP < 0.001 versus control group; E: number of colonies after different concentrations of celastrol treatment 0, 5, 10, 20 µM. CCK-8: cell counting kit-8.

3.2. Celastrol inhibits cell cycle progression and induces cell apoptosis in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells

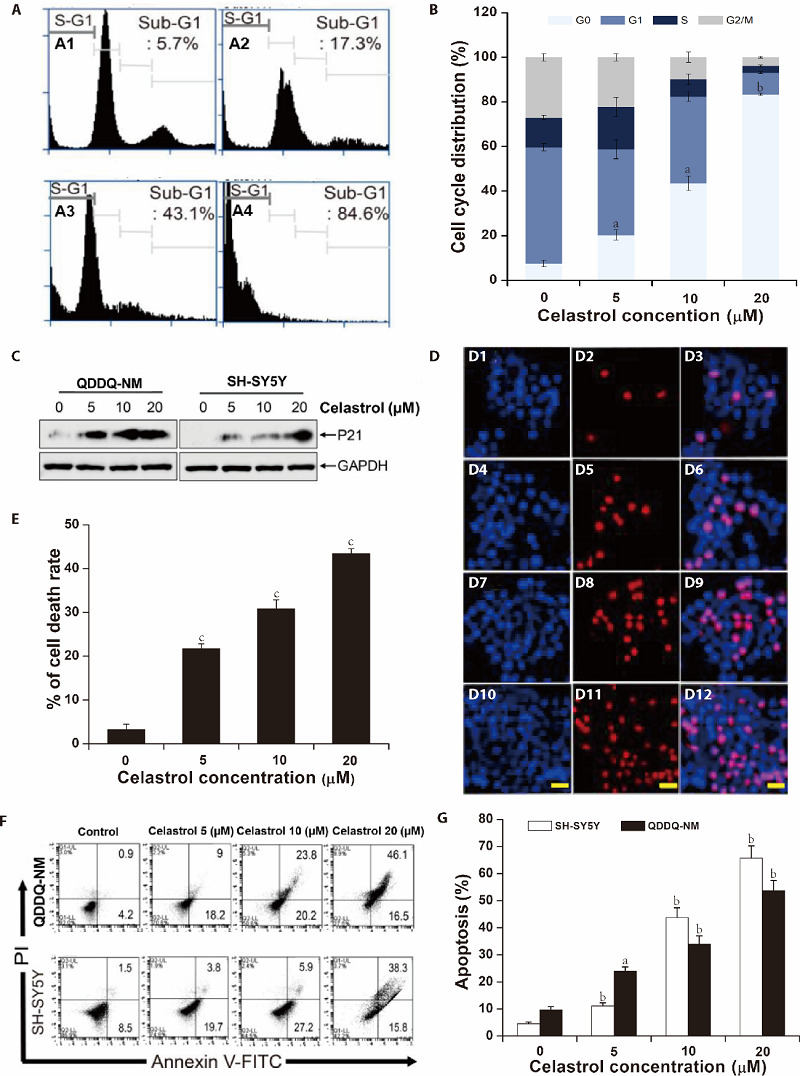

To explore the underlying mechanism by which celastrol inhibits neuroblastoma cells growth, flow cytometry assay we applied to detect the cells cycle distribution in QDDQ-NM cells after treatment with different con-centrations of celastrol for 1 day. As shown in Figure 2 A and B, celastrol remarkably increased the percentage of sub-G1 QDDQ-NM cells dose-dependently. Fur-thermore, the protein expression of P-21 (cell cycle inhibitor protein) in SH-SY5Y and QDDQ-NM cells were increased dose-dependently (Figure 2C). Above data indicated that celastrol suppressed cell cycle progression at sub-G1 phase, which further induced cell growth inhibition in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells.

Figure 2. Celastrol inhibits cell cycle progression and induces cell apoptosis in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells.

A: flow cytometry assay we applied to detect the cells cycle distribution in QDDQ-NM cells after treatment with different concentrations of celastrol (A1) 0 µM, (A2) 5 µM, (A3) 10 µM,(A4) 20 µM for 1 d; B: quantitative analysis of cell cycle distribution was shown after celastrol treatment; C: the protein expressions of P21 were detected by immunoblotting in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells after different concentrations of celastrol treatment; D: QDDQ-NM cells with Hoechst (bright blue) and PI (red) fluorescence signals were identified as apoptotic cells, (D1, D4, D7, D10) Hoechst stanning for 0, 5, 10, 20 µM celastrol treatment; (D2, D5, D8, D11) PI stanning for 0, 5, 10, 20 µM celastrol treatment; (D3, D6, D9, D12) Merged stanning for 0, 5, 10, 20 µM celastrol treatment; scale bar = 50 μm. E: the percentage of cell death rate after celastrol treatment. F, G: flow cytometry assay was applied to determine the apoptosis of QDDQ-NM (a) and SH-SY5Y (b) cells after celastrol treatment. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, cP < 0.001 compared to control.

Next, Hoechst/PI staining was used to confirm cells apoptosis in celastrol-pretreated QDDQ-NM cells. Our results showed that celastrol treatment significantly induced cell apoptosis in QDDQ-NM cells dose-dependently (Figure. 2D). The apoptotic cells in celastrol treatment groups were 21.1% (5 μM), 30.9% (10 μM), and 44.1% (20 μM), respectively (Figure 2E). In addition, flow cytometry assay also confirmed that celastrol induced cell apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells (Figure 2F, 2G).

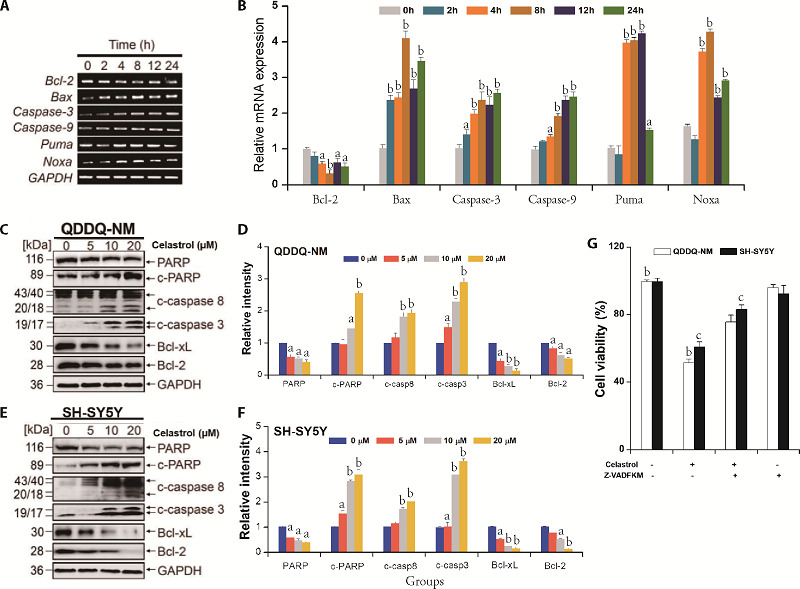

3.3. Caspase death Pathway was Involved in celastrol Induced Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y and QDDQ-NM cells

Western blotting and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay were applied for exploring the mechanisms underlying celastrol-mediated apoptotic cell death. Various apoptotic-related genes such as Caspase-3, Bax, Noxa, p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA), Bcl-2 and Caspase-9 were detected in QDDQ-NM cells after celastrol exposure (5 µM) for different time. Our data indicated that celastrol increased the mRNA expression of pro-apoptosis genes time-dependently (Figure 3A, 3B). The mRNA expression of Bcl-2, an anti-apoptosis gene, was down-regulated in QDDQ-NM cells after celastrol treatment. Western blotting results showed that celastrol treatment increased the protein expression of cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), caspase-8 and caspase-3 in SH-SY5Y and QDDQ-NM cells dose-dependently (Figure 3C-3F). The expression of anti-apoptosis protein including Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 were decreased after celastrol treatment (Figure 3C-3F). However, when Z-VAD-FKM (caspase inhibitor) was pre-treated in CCK-8 assay, celastrol-induced apoptosis was reversed in both SH-SY5Y and QDDQ-NM cells. Above results suggested that celastrol might induce apoptotic cell death in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells by activating caspase death pathway.

Figure 3. Celastrol facilitates apoptosis in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells by activating caspases pathway.

A: mRNA expressions of Caspase-9, Bcl-2, PUMA, Bax, Noxa, and Caspase-3 were examined via RT-PCR assay; B: quantitative analysis of RT-PCR results; C-F: Western blotting and quantification results of the expressions of anti-apoptosis and pro-apoptosis proteins in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells after celastrol treatment. G: cell viability of QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y were examined by CCK-8 assay after combined treatment with Z-VAD-FKM (caspase inhibitor) and celastrol. PUMA: p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis; RT-PCR: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; CCK-8: cell counting kit-8. aP < 0.05, aP < 0.01 versus control and cP < 0.01 versus celastrol treatment group.

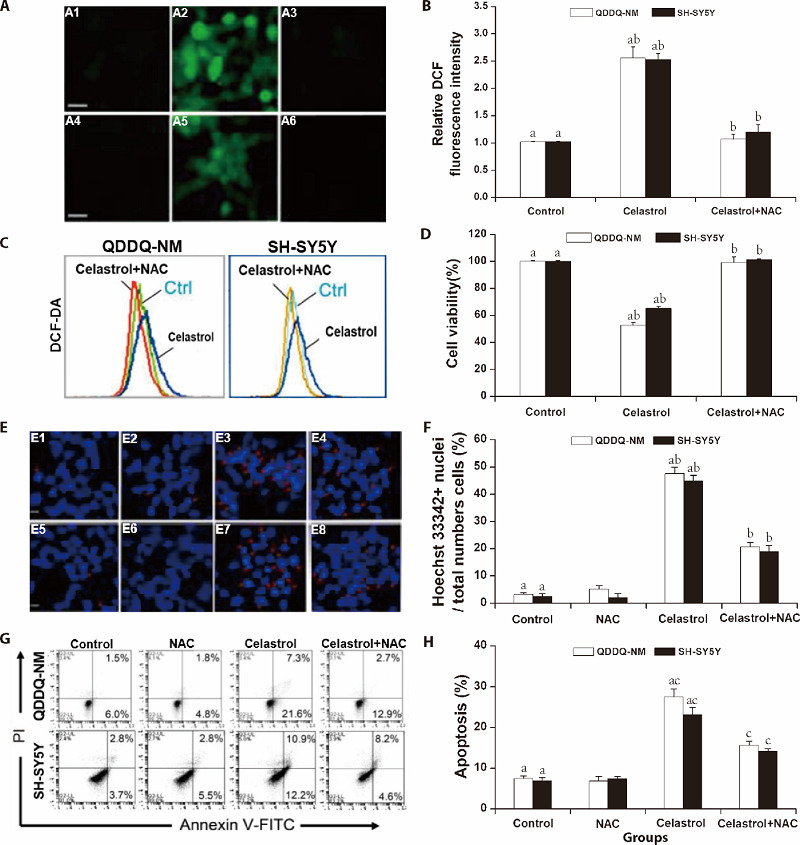

3.4. ROS Production Contributed to celastrol-mediated Apoptosis in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y Cells

Apoptosis can be induced by excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in cells. In this study, for investigating whether excessive ROS production led to celastrol-mediated apoptotic cell death in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells, 2 mM NAC (ROS inhibitor) were pre-treated in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells for 2 h and subsequently treated with celastrol for 1 d. ROS generation was detected by DCF-DA dye by a fluorescence microscopy as well as flow cytometry. Our results showed that celastrol (10 µM) remarkably increased ROS production in cells (Figure 4A-4C). However, NAC significantly reversed celastrol-mediated ROS production in both QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 4A-4C). Cell viability study also confirmed that NAC could reverse celastrol-mediated cell death in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. ROS production was involved in celastrol-mediated apoptosis.

A, B: ROS production was examined under fluorescence microscope by DCFH-DA staining and the relative DCF fluorescence intensities was quantified by Imagelab; A1-A3: QDDQ-NM cells for control group, celastrol group, celastrol with NAC group; A4-A6: SH-SY5Y cells for control group, celastrol group, celastrol with NAC group; C: flow cytometry assay was also applied to assess the effect of NAC on celastrol-mediated ROS production; D: the percentage of cell viability after celastrol treatment. aP < 0.01 compared to control, bP < 0.01 compared to celastrol-pretreated group. E, F: chromatin-condensed nuclei (red arrow) indicated cell apoptosis after staining with Hoechst 33442 dye. E1-E4: QDDQ-NM cells for control group, NAC group, celastrol group, celastrol with NAC group; E5-E8: SH-SY5Y cells for control group, NAC group, celastrol group, celastrol with NAC group. The images were detected by the fluorescence microscope. Scale bar = 50 μm. The proportion of Hoechst 33442+ cells were quantified by Imagelab. G, H: Annexin V and PI were used to stain the apoptosis cells by flow cytometry. The percentage of apoptosis cells of QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y were quantified by Imagelab. aP < 0.01, compared to untreated cells; bP < 0.01, cP < 0.05, compared to celastrol treatment cells. ROS: reactive oxygen species; DCFH-DA: 2, 7-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; DCF: 2′, 7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein; NAC: N-Acetyl-L-cysteine.

Next, we further explored the effects of combination treatment of celastrol with NAC by Annexin V/PI and Hoechst 33442 staining. Our results showed that celastrol exposure remarkably enhanced chromatin condensation in in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells, while pre-treated with NAC suppressed this phenomenon (Figure 4E, 4F). Furthermore, flow cytometry results indicated that celastrol could reduce Annexin V+ cells after pre-treated with NAC (Figure 4G, 4H). In summary, above data demonstrated that ROS production might involve in celastrol-mediated apoptotic cell death in children neuroblastoma cells.

4. DISCUSSION

Neuroblastoma is one of the most commonly malignant tumor in children under twelve years old, which accounting for 16% of cancer-related deaths in children. Despite the progression in multimodality therapy, the overall survival rate for children neuroblastoma is still poor. Thus, developing more effective and safe therapies are urgently needed for children neuroblastoma treatment.

Celastrol is a kind of diterpenoid epoxide isolated from the Chinese medical herb thunder god vine. This herb has been used for treating various kinds of inflammatory diseases and cancers in Traditional Chinese Medicine.15,16 Recently, celastrol has shown great potential for inducing apoptosis in various malignant tumors. For example, celastrol could stimulate the production of ROS and up-regulated the intracellular ROS level to induce apoptotic cell death of ovarian cancer cell.17 In addition, celastrol could directly bind to peroxiredoxin-2 (Prdx2) and suppresses its activity in gastric cancer cell. Suppression of Prdx2 further up-regulated intracellular ROS level and resulted in endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS), mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptotic cell death in gastric cancer cell.15 However, few studies have evaluated the effectiveness of celastrol in children neuroblastoma. In the current study, we found that celastrol could suppress the proliferation of children neuroblastoma cells with few inhibition effects on normal cell lines in vitro. Further mechanisms studies have shown that celastrol inhibited cell cycle progression and induced cell apoptosis in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells. Previous studies have shown that several intracellular proteases may contribute to the deliberate disassembly of the cells into apoptotic bodies during apoptotic cell death.18,⇓-20 In our study, we found that caspase death pathway was involved in celastrol-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y and QDDQ-NM cells. Celastrol treatment increased the protein expression of cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), caspase-8 and caspase-3 in SH-SY5Y and QDDQ-NM cells dose-dependently while the expression of anti-apoptosis protein including Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 were decreased after celastrol treatment. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive and short-lived molecules in cells.21 Intracellular ROS productions exist in equilibrium with various antioxidant defences. Excessive ROS generation may induce damage to nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, membranes, and organelles, which finally result in activation of cells death processes including apoptotic cell death.22,23 Herein, our studies showed that celastrol (10 µM) remarkably increased ROS production in neuroblastoma cells. However, NAC significantly reversed celastrol-mediated ROS production in both QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells. In addition, celastrol exposure remarkably enhanced chromatin condensation in in QDDQ-NM and SH-SY5Y cells, while pre-treated with NAC suppressed this phenomenon. Flow cytometry results also indicated that celastrol could reduce Annexin V+ cells after pre-treatment with NAC. These results demonstrated that ROS production might involve in celastrol-mediated apoptotic cell death in children neuroblastoma cells by activating caspase death pathway.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that celastrol could promote ROS generation-induced apoptosis in children neuroblastoma cell by activating caspases pathway. These findings suggested that celastrol might be a potential novel anti-neuroblastoma agent with minor cytotoxicity.

REFERENCES

- [1]. Polito L, Bortolotti M, Pedrazzi M, Mercatelli D, Battelli MG, Bolognesi A. . Apoptosis and necroptosis induced by stenodactylin in neuroblastoma cells can be completely prevented through caspase inhibition plus catalase or necrostatin-1. Phytomedicine 2016; 23: 32-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Naveen CR, Gaikwad S, Agrawal-Rajput R.. Berberine induces neuronal differentiation through inhibition of cancer stemness and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in neuroblastoma cells. Phytomedicine 2016; 23: 736-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Fukuyama K, Kakio S, Nakazawa Y, et al. Roasted coffee reduces beta-amyloid production by increasing proteasomal beta-secretase degradation in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2018; 62: e1800238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Alberto F, Mario L, Sara P, Settimio G, Antonella L.. Electro-magnetic information delivery as a new tool in translational medicine. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014; 7: 2550-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Unno K, Pervin M, Nakagawa A, et al. Blood-brain barrier permeability of green tea catechin metabolites and their neuritogenic activity in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2017; 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Franco-Luzon L, Garcia-Mulero S, Sanz-Pamplona R, et al. Genetic and immune changes associated with disease progression under the pressure of oncolytic therapy in a neuroblastoma outlier patient. Cancers (Basel) 2020; 12: 1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Szanto CL, Cornel AM, Vijver SV, Nierkens S.. Monitoring immune responses in neuroblastoma patients during therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2020; 12: 519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Shanmugam MK, Ahn KS, Lee JH, et al. Celastrol attenuates the invasion and migration and augments the anticancer effects of bortezomib in a xenograft mouse model of multiple myeloma. Front Pharmacol 2018; 9: 365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Hong M, Wang N, Tan HY, Tsao SW, Feng Y.. MicroRNAs and Chinese medicinal herbs: new possibilities in cancer therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2015; 7: 1643-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Luo Y, Feng Y, Song L, et al. A network pharmacology-based study on the anti-hepatoma effect of Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae. Chin Med 2019; 14: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Zhu F, Li C, Jin XP, et al. Celastrol may have an anti-atherosclerosis effect in a rabbit experimental carotid ather-osclerosis model. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014; 7: 1684-91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Lin FZ, Wang SC, Hsi YT, et al. Celastrol induces vincristine multidrug resistance oral cancer cell apoptosis by targeting JNK1/2 signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2019; 54: 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Liu X, Zhao P, Wang X, et al. Celastrol mediates autophagy and apoptosis via the ROS/JNK and Akt/mTOR signaling pathways in glioma cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2019; 38: 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Wagh PR, Desai P, Prabhu S, Wang J.. Nanotechnology-based celastrol formulations and their therapeutic applications. Front Pharmacol 2021; 12: 673209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Chen X, Zhao Y, Luo W, et al. Celastrol induces ROS-mediated apoptosis via directly targeting peroxiredoxin-2 in gastric cancer cells. Theranostics 2020; 10: 10290-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Hu XL, He QW, Long H, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of celastrol derivatives with improved cytotoxic selectivity and antitumor activities. J Nat Prod 2021; 84: 1954-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Niu W, Wang J, Wang Q, Shen J.. Celastrol loaded nanoparticles with ROS-response and ROS-inducer for the treatment of ovarian cancer. Front Chem 2020; 8: 574614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Puangpraphant S, Berhow MA, Vermillion K, Potts G, Gonzalez de Mejia E.. Dicaffeoylquinic acids in Yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis St. Hilaire) inhibit NF-kappa B nucleus translocation in macrophages and induce apoptosis by activating caspases-8 and -3 in human colon cancer cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2011; 55: 1509-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Hong M, Almutairi MM, Li S, Li J.. Wogonin inhibits cell cycle progression by activating the glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta in hepatocellular carcinoma. Phytomedicine 2020; 68: 153174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Agidigbi TS, Kim A,. Reactive oxygen species in osteoclast differentiation and possible pharmaceutical targets of ROS-mediated osteoclast diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Rohn TT, Kokoulina P, Eaton CR, Poon WW.. Caspase activation in transgenic mice with Alzheimer-like pathology: results from a pilot study utilizing the caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh. Int J Clin Exp Med 2009; 2: 300-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Hong M, Li J, Li S, Almutairi MM. . Resveratrol derivative, trans-3, 5, 4'-trimethoxystilbene, prevents the developing of ather-osclerotic lesions and attenuates cholesterol accumulation in macrophage foam cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2020: e1901115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Lamichhane S, Bastola T, Pariyar R,. et al. ROS production and ERK activity are involved in the effects of d-beta-hydroxybutyrate and metformin in a glucose deficient condition. Int J Mol Sci 2020: e1901115. 2017; 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]