Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to verify the prevalence of dietary supplements among CrossFit practitioners (CFPs), considering gender and training status. Still, we aimed to determine the type, reasons, and associated factors of dietary supplement utilization among CFPs.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional, exploratory, and descriptive study with the snowball sampling method. Data were collected through online questionnaires using the Google Forms® tool. We included CFPs aged 18–64 years, from Aug 1, 2020, to Sept 31, 2020. The questionnaire contained questions to assess the prevalence, type, and reasons for supplement use; also, we assessed information about sociodemographic variables and the prevalence of the main chronic morbidities. To analyze aspects of eating behavior and sleep-related parameters, we applied the three-factor eating questionnaire (TFEQ)-R21 and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index questionnaire (PSQI), respectively.

Results

We assessed one hundred twelve (n = 112; 57 men; 55 women) CFPs (28.9 ± 7.64 years old; body mass index (BMI), 25.5 ± 4.83 kg/m2). Eighty-seven (50 men; 37 women; 28.2 ± 6.66 years old; BMI, 25.4 ± 4.55 kg/m2) reported using dietary supplements. Whey protein was the most used supplement (n = 70), followed by creatine (n = 54). Cognitive restraint (a dimension of eating behavior) score was higher in supplement users than in non-users (51.7 ± 18.6 vs. 42.6 ± 20.5; p = 0.040). Sleep-related parameters did not differ between supplement users and non-users. The most associated factors to supplement use were sex (being man; OR, 7.99; p = 0.007), sleep quality (poor; OR, 5.27; p = 0.045), CrossFit level (as prescribed (RX); OR, 4.51; p = 0.031), and cognitive restraint (OR, 1.03; p = 0.029).

Conclusion

The CFPs, especially RX and Elite ones, showed a higher prevalence of supplement utilization. Anabolic-related supplements (i.e., whey protein and creatine) were the most used; moreover, several CFPs used supplements not supported by scientific evidence. Cognitive restraint score was higher in supplement users than in non-users. RX level, being men, and poor sleep quality were associated with supplement utilization. These data draw attention to the necessity of nutritional education for CrossFit coaches and athletes. Broader studies are necessary to confirm our findings.

Keywords: CrossFit®, Dietary supplementation, Three-factor eating questionnaire, Sleep quality

Introduction

High-intensity functional training regimens such as CrossFit® (CF) consist of training methods comprising several physical exercises including weightlifting, powerlifting, sprints, plyometrics, calisthenics, gymnastics, and running [1].

In the past few years, CF training has become very popular, once it can be practiced by people in all shapes and sizes, starting at any age, according to their official website [2]. CF workouts are challenging, but one of the reasons why CF is so popular is the use of scaling to create optimal conditions for various age groups, adaptive practitioners, or performance levels [3]. The “workouts of the day” (known as WODs) posted on CrossFit.com are designed for elite athletes with CF experience, who compete in national and international levels (i.e., in CrossFit Games). Almost all new CrossFit® practitioners (CFPs) will have to scale their workouts [4]. In this sense, if CFPs are able to perform the WODs as prescribed, they are placed in the RX category. If CPFs scale their WODs, they are placed in the Scale category [4].

Considering the high energy demand required to perform the high-intensity WODs, even when scaled, CFP commonly follow diets that promise performance improvement (i.e., Zone diet and paleo diet) or take pre- or post-exercise dietary supplements as ergogenic aids [5, 6]. According to the CF founders’ recommendations, high amounts of protein should be consumed, representing up to 30% of total energy intake. Likewise, the dietary intake of fat should cover 30% of the daily energy requirements (mainly as mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids). Carbohydrates’ contribution in the diet was initially recommended at a low level (about 40% of the daily energy requirements) [5, 6].

Interestingly, these recommendations do not have sufficient scientific support and differ from the latest recommendations proposed by the consensus widely followed by nutritionists and exercise professionals [7, 8]. Previous studies suggest that it is common to find inappropriate eating practices among CFPs, and most of them are characterized as low energy intake [9, 10]. Restrictive eating behaviors are common in sports that involve the necessity to control body mass or to lose weight [11, 12], tending to be associated with greater body image concern [13, 14].

Considering the high energy expenditure of athletes such as CFPs, dietary restraint can lead to low energy availability (LEA), resulting in poor exercise performance, besides worsening several health outcomes [15]. In CFPs, LEA may be expected, although little has been identified [9]. It is believed that a balanced diet is usually sufficient for athletes to obtain appropriate amounts of required nutrients [8, 16]; however, the use of dietary supplements is common among athletes who aim to minimize nutrient inadequacies in their diet, increase performance, improve body composition, or improve specific health outcomes [16]. The main exercise-specific reasons for supplement use include the belief that stress of intense training/competition (load) cannot be met by food only [16]. At the highest levels of competition, athletes already train intensely and are highly motivated, so marginal advantages obtained can be decisive for winning the competition [16].

On the other hand, supplement use may be frequent even for those who are not elite CF athletes (i.e., athletes following scale and RX prescriptions). The combination of higher energy expenditure generated by performing WODs associated with the desire to lose weight, to increase muscle mass, and to improve exercise performance or quality of life can encourage CFPs to start or increase the use of supplements [17, 18]. More recently, Brisebois et al. [18] verified that among CFPs, 82.2% consumed at least one supplement, being protein (51.2%), creatine (22.9%), and pre-workout/energy (20.7%) the most popular ones. Nevertheless, the greatest reasons for supplement intake comprised improving exercise recovery (52.6%), overall health (51.4%), and increasing muscle mass/strength (41.7%).

CFPs’ prevalence of use of supplements and its relationship with behavioral aspects are currently unclear. Recently, our group published a systematic review investigating nutritional interventions on CFPs’ performance [19]. Few studies have been found, showing that little is known about the topic [19]. Furthermore, few cross-sectional studies have investigated the relationship between nutrition and CF.

Therefore, we aimed to verify the prevalence of dietary supplements among CFPs, considering gender and training status. We also aimed to determine the type of dietary supplements used, reasons for their use, and associated factors of their utilization among CrossFit practitioners.

Methods

Study type, sample, and ethics

This is a cross-sectional, exploratory, and descriptive study. Data were collected through online questionnaires, using the Google Forms® tool. Inclusion criterion comprised CrossFit practice for at least 1 year. Diseases were not considered as exclusion criteria. In fact, the prevalence of the main chronic morbidities (type 1 and type 2 diabetes, systemic arterial hypertension, and dyslipidemias) was assessed. Participants were aged 18–64 years. The survey was made available online, via social media, and randomly dispersed to as many people as possible from August 1, 2020 to Sept 31, 2020. Snowball sampling method was applied to recruit additional participants. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, participants were asked to answer the questions without considering social isolation changes. Only one answer per participant was accepted.

The sample was composed exclusively of male and female CFPs of different levels (Scale, RX, or Elite). Practitioners should declare themselves as “Scale” when all or most of the workouts are performed with adaptation (in at least one movement or load), regardless of the total time or performance; as “RX” when all workouts are performed with no adaptation, as prescribed; and as “Elite” when all workouts are performed with no adaptation, and they compete at a high level. The explanation of the categories was previously provided so that participants could respond adequately.

Informed consent was obtained along with the questionnaire. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (4.165.399), and it was carried out in accordance with the procedures approved by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Questionnaire

The first questionnaire used in this investigation was applied according to Navarro et al. [20], containing questions to assess prevalence, type, and reasons for supplements use, besides information on sociodemographic variables.

Analysis of dietary supplements by group

According to Baltazar-Martins et al. [21], each supplement was individually notated and grouped according to the groups of the IOC consensus statement [7], as follows:

-

(i)

“Performance enhancement”, which included caffeine, beta-alanine, creatine, sodium bicarbonate, beet root juice (nitrate), carbohydrate drink, or gel

-

(ii)

“Immune health”, which included antioxidant supplements, vitamin D, vitamin E, probiotics, and vitamin C

-

(iii)

“Micronutrients”, which included iron supplements, magnesium, folic acid, calcium, zinc, selenium, multivitamin supplements, and electrolytes

-

(iv)

“Improve recovery and injury management”, which includes joint support supplements (glucosamine, chondroitin, collagen), recovery supplements (mixes of carbohydrate and protein powders labeled as a “recovery product”), omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and curcumin

-

(v)

“Body composition changes”, which includes protein powders (whey protein mixes, casein, calcium caseinate, plant-/meat-/egg-based protein powders)

-

(vi)

“Low level of evidence supplements”, which includes glutamine, single amino acids/branched chain amino acids (BCAA), beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate (HMB), l-carnitine, spirulina, royal jelly, citrulline, taurine, conjugated linoleic acid, co-enzyme Q10, and fat burners, among others

Participants were not given a list of supplements or group of supplements. They had to list all the supplements they used in a blank space. The researchers categorized them afterwards.

Eating behavior

To analyze aspects of eating behavior, we used the “three-factor eating questionnaire (TFEQ-R21)” [22], which was translated and validated to the Brazilian population [23]. TFEQ-21 evaluates three human eating behavior dimensions: emotional eating score (EEs), cognitive restraint score (CRs), and binge eating score (BEs). EEs includes six items that assess the propensity to overeat in response to negative emotions, such as anxiety, depression, and loneliness. CRs include six items that assess several factors involving food intake and concerns about body mass changes. BEs include nine items to provide analysis on the individual’s tendency to lean toward high food intake during a short period of time, generally triggered by some external stimuli.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means and standard deviation (mean ± SD) or frequency (%). We used an independent t test to determine the difference between continuous variables according to CFPs’ gender and supplementation status (users vs. no users). Likewise, we applied the analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the difference between continuous variables according to CFPs levels, followed by Bonferroni correction. Cohen estimated effect sizes for independent t test and by partial eta squared for ANOVA. Using the chi-squared test, we verified the relationship between categorical variables (i.e., gender, type of dietary supplements, CrossFit level and goals, diseases, smoking status, PSQI score, injury story). We applied Pearson’s coefficient correlation test to determine the correlation between continuous variables.

Moreover, we conducted a logistic regression considering supplement utilization as the dependent variable. The insertion of independent variables depends on (i) a p value below 0.020 in univariate analysis and (ii) biological plausibility. Nevertheless, in the multiple models, we considered collinearity and goodness of fit by R2 of McFadden and Akaike information criterion (AIC).

We executed all statistical analyses using Jamovi® 2.3.21 version. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

All answers to the questionnaire were carefully screened for coherence with their respective proposed questions. All subjects who answered the questionnaire were included in the present study. The sample consisted of 112 CFPs (57 males and 55 females). The mean age was 28.9 ± 7.64 (males: 28.1 ± 7.64; females: 29.7 ± 7.62) with no difference between genders (t = − 1.13; p = 0.259). Among males, 50 (87.7%) use supplements, while among females, 37 (67.3%) use supplements. The age did not differ between supplement status (t = 1.79; p = 0.076). Most of the participants were employed (n = 93; 47 males; 46 females) at the time of data collection.

Regarding CF levels, 20 subjects (17.9%; 8 males and 12 females) declared pertaining to the Scale category, 57 subjects (50.9%, 20 males and 37 females) declared pertaining to the RX category, and 35 subjects (31.3%; 29 males and 6 females) declared pertaining to the Elite category. According to these categories, the mean age was 31.2 ± 10.1 years (Scale), 29.2 ± 7.0 years (RX), and 27.1 ± 6.71 years (Elite), with no difference between groups (F(2,107) = 1.97; p = 0.144; ηp2 = 0.036). Athletes’ current use of supplements statement, CF levels, income, sleep pattern, eating behavior, and presence of diseases are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants and distribution of CF athletes who reported current use/no use of supplements

| Frequency % (n) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Supplement users | Non-supplement users | ||

| Use of supplements (n; %) | 77.7 (87) | 22.3 (25) | |

| Gender (n; %) | |||

| Male | 57.5 (50) | 28.0 (7) | 0.009 |

| Female | 42.5 (37) | 72.0 (18) | |

| Age (years) | 28.2 ± 6.6 | 31.3 ± 10.1 | 0.076 |

| Weight (kg) | 74.1 ± 17.3 | 76.8 ± 21.8 | 0.530 |

| Height (cm) | 170 ± 10.1 | 172 ± 12.3 | 0.517 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 ± 4.55 | 25.8 ± 5.79 | 0.732 |

| Type of supplements (n; %) | |||

| Performance enhancement | 34.9 (65) | - | |

| Micronutrients | 7 (13) | - | |

| Improve recovery | 7.5 (14) | - | |

| Body composition changes | 38.7 (72) | - | |

| Low-level evidence-based supplements | 11.8 (22) | - | |

| CrossFit levels (n; %) | |||

| Scale | 11.5 (10) | 40.0 (10) | 0.002 |

| RX | 51.7 (45) | 48.0 (12) | |

| Elite | 36.8 (32) | 12.0 (3) | |

| CrossFit practice goals (n; %) | |||

| Changes in body composition | 53 (67.9) | 16 (80) | 0.003 |

| Improve exercise performance | 24 (30.8) | 1 (5) | |

| Improve quality of life | 1 (1.3) | 3 (15) | |

| Reasons to supplementation (n; %) | |||

| Exercise performance | 47 (54) | - | |

| Augment muscle mass | 29 (33.3) | - | |

| Reduces body fat | 8 (9.2) | - | |

| Injury prevention | 3 (3.4) | - | |

| Month income (n; %) | |||

| < 1 salaries | 11.6 (13) | 0.89 (1) | 0.204 |

| 1–2 salaries | 14.24 (16) | 4.46 (5) | |

| 3–4 salaries | 23.21 (26) | 8.92 (10) | |

| 5–9 salaries | 18.75 (21) | 6.25 (7) | |

| ≥ 10 salaries | 9.82 (11) | 1.78 (2) | |

| Diseases (n; %) | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 0.9 (1) | 99.1 (111) | 0.061 |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | 0 | 0 | - |

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 0.9 (1) | 99.1 (111) | 0.590 |

| Dyslipidemias | 1.8 (2) | 98.2 (110) | 0.348 |

| Smoking (n; %) | 2.7 (3) | 97.3 (109) | 0.657 |

| Sleep-related parameters | |||

| Duration (h) | 7.15 ± 1.28 | 6.87 ± 1.58 | 0.373 |

| Efficiency (%) | 91.8 ± 10.7 | 88.1 ± 13.6 | 0.163 |

| PSQI score (n; %) | |||

| Good sleep quality (< 5) | 46 (54.11) | 15 (60) | 0.341 |

| Poor sleep quality (≥ 5) | 41 (45.88) | 10 (40) | |

| TFEQ-21 (scores) | |||

| Emotional eating | 33.2 ± 26.7 | 33.6 ± 24.3 | 0.953 |

| Binge eating | 32.2 ± 19.8 | 35.3 ± 17.5 | 0.486 |

| Cognitive restraint | 51.7 ± 18.6 | 42.6 ± 20.5 | 0.040 |

| Injury history (n; %) | |||

| Yes | 39 (44.8) | 4 (16.0) | 0.009 |

| No | 48 (55.2) | 21 (84) | |

Description of sociodemographic data. Chi-squared test. Salary (193.87 USD) in local currency was calculated considering the average exchange rate in the data collection period. N = 112. Significant data are displayed in bold

Use of dietary supplements

Out of all 112 CFPs, 87 (77.7%; 50 males; 37 females) currently reported using dietary supplements, while 25 (22.3%; 7 males; 18 females) did not use any dietary supplement. Examining by participant’s levels, we verified statistical differences between supplementation frequency (X2 = 12.7; p = 0.002). Among the RX and Elite participants, 45 (78.9%) and 32 (91.4%) use dietary supplements, respectively. However, no difference was found when data were analyzed according to their monthly income (X2 = 5.93; p = 204) (Table 1).

Considering the reasons why those 87 athletes started using dietary supplements, we found goals of increasing exercise performance (n = 47; 54%), increasing muscle mass (n = 29; 33.3%), reducing body fat (n = 8; 9.2%), and preventing injuries (n = 3; 3.4%). Difference was found when these data were analyzed according to participant’s levels (X2 = 37.3; p < 0.001). RX CFPs use supplements for muscle hypertrophy (n = 20; 44%) and performance enhancement (n = 19; 42.2%), whereas elite CFPs use them especially for performance enhancement (n = 25; 78.1%) (Table 1).

Concerning frequency, CFPs reported using supplements 5 or more times per week (n = 57; 33 males; 24 females), 2–5 times per week (n = 22; 10 males; 12 females), less than twice a week (n = 1; 1 female), and rarely (n = 7; 7 males) (X2 = 7.84; p = 0.050). Difference was found when data were analyzed according to CFPs’ levels (X2 = 13.5; p = 0.036). Four Scale CFPs, 14 RX CFPs, and 4 Elite CFPs reported using supplements 2–5 times per week. Five Scale CFPs, 27 RX CFPs, and 25 Elite CFPs reported using supplements 5 or more times per week (Table 2). Regarding supplement prescription, 69 CFPs’ (61.6%; 37 males; 32 females) reported using supplements without professional support, and 43 CFPs (38.4%; 20 males; 23 females) reported having nutritionist or sports physician counseling. No statistical difference was found (X2 = 1.18; p = 0.943) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of supplement utilization and professional support

| Male (n; %) | Female (n; %) | Scale (n; %) | RX (n; %) | Elite (n; %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (times per week) | |||||

| ≥ 5 times per week | 33 (66) | 24 (64.9) | 5 (50) | 27 (60) | 25 (78.1) |

| 2–5 times per week | 10 (32.4) | 12 (20) | 4 (40) | 14 (31.1) | 4 (12.5) |

| < 2 times per week | 0 (0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Rarely | 7 (14) | 0 | 0 (0) | 4 (8.9( | 3 (9.4) |

| p value | 0.050 | 0.036 | |||

| Professional support | |||||

| No professional support | 37 (64.9) | 32 (58.2) | 12 (60) | 36 (63.2) | 21 (60) |

| Nutritionist or sports physician counseling | 20 (35.1) | 23 (41.8) | 8 (40) | 21 (36.8) | 14 (40) |

| p value | 0.464 | 0.943 | |||

Chi-squared test was applied. n = 112. Significant data are displayed in bold

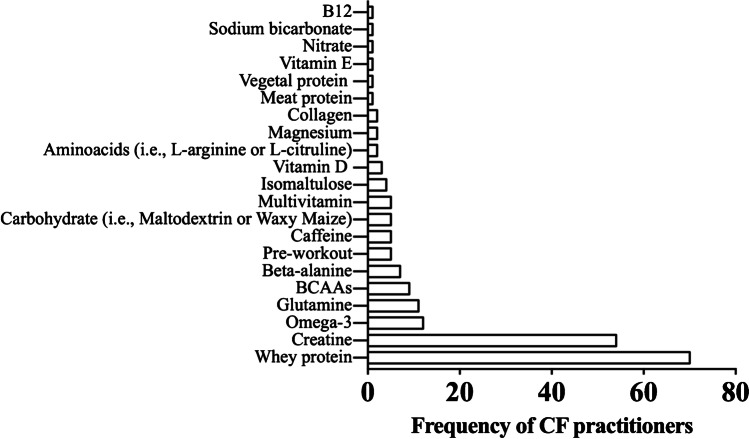

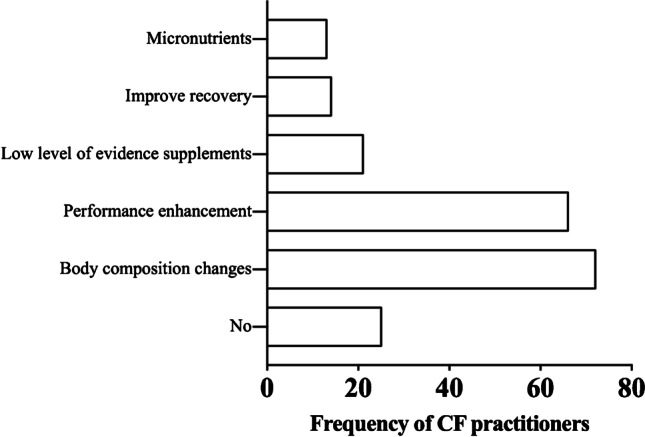

Screening for types of supplements was performed individually, due to the possibility of one individual using more than one supplement. We verified that seventy-two CFPs (38.7%) use “body composition changes” supplements. Sixty-six CFPs (35.5%) use “performance enhancement” substances. Twenty-one CFPs (11.3%) used “low levels of evidence” supplements. Fourteen CFPs (7.5%) use “improve recovery and injury management” supplements, and thirteen CFPs (7%) use micronutrients, with no difference between CFPs of different levels (Fig. 1.)

Fig. 1.

Frequency of CrossFit practitioners’ use of supplements according to the IOC classification (n = 112)

Whey protein was the most used supplement (n = 70), followed by creatine (n = 54), omega-3 (n = 12), glutamine (n = 11), BCAAs (n = 9), beta-alanine (n = 7), caffeine (n = 5), carbohydrate powder (n = 5), pre-workouts (n = 5), multivitamin (n = 5), isomaltulose (n = 4), vitamin D (n = 2), magnesium (n = 2), collagen (n = 2), meat protein (n = 1), vegetable protein (n = 1), vitamin E (n = 1), nitrate (n = 1), sodium bicarbonate (n = 1), and B-12 vitamin (n = 1). Nineteen CFPs reported the use of more than one performance-enhancing supplement. Two CFPs reported the use of more than one supplement with low levels of evidence (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of CrossFit practitioners according to the use of each specific type of supplement (n = 112)

CrossFit practice goals

Subjects reported practicing CF to improve body composition (n = 69; 70.4%; 29 males; 40 females), to improve performance (n = 25; 25.5%; 18 males; 7 females), and to improve quality of life (n = 4; 4.1%; 1 male; 3 females). Regarding supplement status, among supplement users, CF practice goals were 53 (67.9%), 24 (30.8%), and 1 (1.3%) to improve body composition, performance, and quality of life, respectively. Among non-supplement users, CF practice goals were 16 (80.0%), 1 (5.0%), and 3 (15%) to improve body composition, performance, and quality of life, respectively. The frequency of distributions was significantly different (X2 = 11.8; p = 0.003) (Table 1).

Injury history

Forty-three CFPs (38.4%; 25 males, 18 females) reported having had at least one injury during CF practice, and 69 CFPs (61.6%; 32 males; 37 females) reported never having had injuries during CF practice. Injuries did not differ between genders (X2 = 1.47; p = 0.226). According to supplement status, we found a higher frequency of injuries among supplement users (44.8%) compared to non-users (16%) (X2 = 6.82; p = 0.009) (Table 1).

Eating behavior

No difference between genders was found concerning TFEQ-R21 dimensions of EE (t = 1.328; p = 0.187; Cohen’s d = 0.25), BE (t = 0.527; p = 0.599; Cohen’s d = 0.10), and CR (t = 0.463; p = 0.644; Cohen’s d = 0.08). Moreover, no differences were found when data were analyzed according to CFPs’ levels (EE: F(2, 107) = 1.37, p = 0.258, ηp2 = 0.025; BE: F(2, 107) = 0.07, p = 0.932, ηp2 = 0.001; CR: F(2, 107) = 2.79, p = 0.066, ηp2 = 0.050). Correlation analysis showed positive correlation between EE and BE (r = 0.49; p < 0.001). However, among supplement users, we observed high levels of cognitive restraint (t = 2.083; p = 0.040; Cohen’s d = 0.48) compared to non-supplement users (Table 1).

Life habits and illness

On average, CFPs sleep 7.09 ± 1.35 h (6.90 ± 1.38 for men and 7.28 ± 1.30 for women) per night, without significant difference between genders (t = − 1.498; p = 0.137; Cohen’s d = 0.28; small). The average sleep efficiency was 91.0 ± 11.4% (91.2 ± 12.5 for men; 90.8 ± 10.5 for women) without significant difference between genders (t = 0.166; p = 0.868; Cohen’s d = 0.03; insignificant). Regarding supplement status, hours of sleep (t = 0.896; p = 0.373; Cohen’s d = 0.210 small) and sleep efficiency (t = 1.403; p = 0.163; Cohen’s d = 0.330 small) did not differ between the groups. Moreover, PSQI did not differ (X2 = 0.907; p = 0.341) between groups (Table 1).

Data analysis according to CFPs’ levels showed that Scale, RX, and Elite CFPs’ sleep durations were 6.45 ± 1.54, 7.41 ± 1.22, and 6.92 ± 1.29 h, respectively. Still, Scale, RX, and Elite CFPs’ sleep efficiency was 84.8 ± 15.3%, 92.7 ± 10.7%, and 91.9 ± 8.51% h, respectively. Differences were found between groups regarding sleep duration (F(2, 105) = 4.41; p = 0.014; ηp2 = 0.078) and sleep efficiency (F(2, 105) = 3.80; p = 0.025; ηp2 = 0.068). Scale CFPs sleep less than RX CFPs (mean = − 0.962; SE = 0.339; t = − 2.84 l; p = 0.015; Cohen’s d = 0.73), having lower sleep efficiency (mean = − 7.933; SE = 2.90; t = − 2.704; p = 0.022; Cohen’s d = 0.70). No significant differences were found between CFPs of different levels concerning sleep quality assessed through PSQI (X2 = 6.31; p = 0.177). Negative correlation was found between age, hours of sleep (r = − 0.209; p < 0.001), and sleep quality (r = − 0.197; p = 0.043).

One hundred and nine CFPs declared themselves as non-smokers (57 males; 52 females; X2 = 3.81; p = 0.537), 111 CFPs (56 males; 55 females; X2 = 0.974; p = 0.324) reported not having diagnosis of systemic arterial hypertension, 109 CFPs (57 males; 52 females; X2 = 2.15; p = 0.143) reported not having diagnosis of diabetes dyslipidemias (hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia), 111 CFPs (57 males; 54 females; X2 = 1.05; p = 0.306) reported not having diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and none reported having diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus (Table 1).

Socioeconomic status

Regarding monthly income, CFPs reported receiving less than 1 minimum wage (n = 14; 12.7%), between 1 and 2 minimum wages (n = 21; 19.1%), between 3 and 4 minimum wages (n = 36; 32.7%), between 5 and 9 minimum wages (n = 28; 25.5%), and more than ten minimum wages (n = 11; 10%). Analysis according to CFPs’ levels showed differences (X2 = 17.7; p = 0.024): 36 CPFs (10 Scale; 17 RX; 9 Elite) receive 581.61–775.48 USD and 28 CFPs (4 Scale; 18 RX; 6 Elite) receive 969.35–1.755,83 USD (Table 1).

Associated factors to dietary supplementation

We created a logistic regression with supplement use as the outcome (Table 3). We observed that AIC was 94.6, R2 by McFadden was 0.309, and X2 34.3, p < 0.001. To guarantee the quality of the model and tolerance between independent variables, we examined the variance inflation factor.

Table 3.

Logistic regression considering supplement utilization as the dependent variable

| Variables | Mean (OR) | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male vs. female | 7.99 | 1.77–35.98 | 0.007 |

| PSQI score (≥ 5 vs. < 5) | 5.27 | 1.035–26.83 | 0.045 |

| Injury history | 2.88 | 0.711–11.69 | 0.138 |

| CrossFit level | |||

| RX vs. Scale | 4.51 | 1.14–17.75 | 0.031 |

| Elite vs. Scale | 7.55 | 0.67–85.18 | 0.102 |

| CRs | 1.03 | 1.004–1.07 | 0.029 |

Logistic regression test was applied considering supplement utilization as the dependent variable. Logistic regression model was controlled by age, sleep efficiency, and income. n = 112. CR cognitive restraint score. Significant data are displayed in bold

We found that being male (OR, 7.99; p = 0.007), having poorer sleep quality (OR, 5.27; p = 0.045), pertaining to the RX level (OR, 4.51; p = 0.031), and having a higher CR score (OR, 1.03; p = 0.029) were factors positively associated with supplement use.

Discussion

The present study aimed to determine the prevalence of use of dietary supplements among CFPs of different levels. In addition, we aimed to determine whether the use of supplements was associated with aspects involving eating behavior or not, particularly concerning the dimension of dietary restraint, culminating in energy imbalance, and ultimately, worsening performance and health.

The frequency of use of supplements was 77.7% (n = 87), mainly represented by men 44.64% (n = 50). Body composition change supplements are the most used among CFPs (n = 72; 38.7%), represented by whey protein (n = 70) and other proteins (i.e., meat or vegetable proteins). Performance enhancement substances are the second most used (n = 65), especially creatine (n = 54) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Summary of the prevalence of use of supplements according to the categories of the IOC consensus statement and the main products used

The dietary supplement prevalence among sportspeople and athletes is higher when compared to the general population [24], especially male athletes [25]. While non-athletes believe that using supplements will confer benefits for health [26], athletes’ use relies mainly on performance improvement [16]. In the present study, several CFPs who use supplements (n = 47; 54%) reported exercise performance improvement. Moreover, the relationship between dietary supplements and training load is well described. Due to higher energy expenditure, athletes consume supplements which allow them to sustain the training load [16]. According to our findings, the most used supplement was whey protein (n = 72; 64.28%), which is used primarily to increase adaptations mediated by resistance exercise, despite the different effects on the body [27]. However, some CFPs may attribute performance improvement to whey protein, despite being used after training sessions to improve muscle recovery [28, 29]. Proteins and amino acids represent the most consumed ergogenic aids, with a frequency of 35–40% [21]. It seems that some people are using whey protein in an incorrect manner, believing it is an ergogenic aid. In this sense, our findings suggest that nutrition education, especially concerning supplement use, would be very important and necessary to CFPs.

The second most used supplement was creatine (n = 54; 48.21%). Creatine is an organic nitrogen compound found in muscle or available in the diet [30]. It is a classic supplement for those who aim to increase intramuscular stores of phosphocreatine, to improve ATP synthesis and high-intensity exercises performance [31–33]. Furthermore, creatine is able to increase lean body mass and strength of upper [32] and lower [31] limbs. According to Momaya, Fewal, and Estes [34], creatine is one of the most popular sports dietary supplements on the market, with more than $400 million in annual sales. The use of creatine varies according to the public. Some studies found prevalence of 14% among college student athletes [35], 34.1% among children and adolescents [36], and 27% in the military [37], with the purpose of enhancing sports performance.

Likewise, Brisebois et al. [18] assessed 2576 (48% male; 51.9% female) CFPs. The CF-related experience was 5.26 ± 3.07 years. Corroborating our findings, they found that protein (n = 1320, 51.2%) and creatine (n = 591, 22.9%) were the most utilized supplements. The foremost motivations for using supplements were to enhance recovery (n = 1355, 52.6%), improve overall health (n = 1324, 51.4%), and augment muscle mass/strength (n = 1074, 41.7%). Males choose supplementation specially to improve CF performance (50.2% vs. 31.2%, p < 0.001), to improve recovery (58.0% vs. 47.7%, p < 0.001), to boost energy levels (36.7% vs. 28.2%, p < 0.001), and to increase strength/muscle mass (51.1% vs. 33.1%, p < 0.001).

CF comprises several movements, often performed in a short period of time, characterized as high-intensity exercise, especially in Olympic weightlifting. In this sense, it is intuitive to believe that creatine supplementation can positively affect performance, despite the lack of studies conducted with CFPs [19]. In fact, 29 CFPs (33.3%) use supplements for muscle hypertrophy (whey protein and creatine), an outcome scientifically supported [7]. Fifty-seven CFPs (65.5%; 33 men; 24 women) reported using dietary supplements 5 or more times per week, a high frequency attributed to whey protein and creatine, which are generally used on a daily basis by athletes. In Brazil, the practice of CF has an intense appeal for changes in body composition, especially weight loss, while evidence on this and other topics is scarce [38].

Some athletes understand that avoiding injuries or illnesses reduces interruptions during preparation for competitions [39]. Although injuries [40] and rhabdomyolysis [41] were reported in CF, in the present study only 3.4% of CFPs reported using supplements to reduce the frequency of injuries. This probably means that they do not consider the use of supplements to be an important factor for reducing the risk of injuries, while a relationship between nutrition and injuries has been widely explored [42–44]. In this context, the necessity of nutrition education also applies to CFPs.

Recently, a systematic review including 165 studies showed that the primary users of supplements are soccer players and bodybuilders. The most used supplements were vitamins and minerals. The prevalence of supplement use varies widely, mainly due to the period of use. While some studies have assessed the use of supplements in the past few days, others do not clarify when these supplements were being used. In our study, CFPs were asked about their current use of supplements, according to 14 studies included in the meta-analysis [24].

Analysis of eating behavior dimensions, such as binge eating (BE), emotional eating (EE), and cognitive restraint (CR), showed no differences between genders or CFPs of different levels, although women commonly display greater EE than men [24]. Physical exercise may be able to suppress EE [45], possibly justifying this result. It is important to consider, however, that BE and EE were positively correlated (r = 0.496; p < 0.001; data not shown) in CFPs of the present study.

Interestingly, we found that those who use supplements have more significant CR than those who do not use supplements. CR appears to be a psycho-marker of weight loss [46, 47].

The use of supplements may be related to CR because several people prefer supplement consumption to food intake for weight loss. Also, dietary supplements may be selected to counteract potential nutrition deficiencies in weight loss programs. Nevertheless, there are no high-quality studies that showed the effect of supplements on weight loss [48]. Lower food intake directly relates to CR [49], which involves restrictive food practices. CR is defined as the cognitive effort exerted by an individual to eat less than they would like, with self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and self-reinforcement [50]. Intensification of this dimension could contribute to promote imbalances between energy intake and expenditure [51]; however, the relationship between supplements and CR is unclear. Supplements are commonly used to correct inadequacies in food intake [24]. Restrictive behaviors are exacerbated in the sports scenario, especially when body composition is crucial for performance. For CFPs, gymnastic movements are better performed when subjects are lighter. It is possible that, for this reason, the dietary restraint may be pronounced among them. We could speculate on the use of weight loss supplements and partial meal replacements, but we did not identify the use of these products in the present study. No previous studies have investigated these food behavior dimensions in CFPs. Therefore, it is not possible to compare our findings with other studies. CFPs were just asked if they followed some diet plan and used supplements.

Finally, analysis of sleep variables showed that Scale CFPs get fewer hours of sleep and have lower sleep efficiency than RX CFPs. We found that poorer sleep quality was an independent factor associated with supplement use. People who feel more fatigued due to worse sleep may believe that the supplement, especially stimulants, may favor better exercise performance. Studies that verified the effect of sleep on exercise performance are heterogeneous [52]. The impact of sleep on health parameters has been increasingly explored in the past few years [53]. Even though only subjective parameters are normally used to assess different aspects of sleep (i.e., PSQI), available evidence suggests a positive and bidirectional relationship between sleep and exercise performance [54]. Positive effects of exercise on sleep were previously demonstrated in other populations [55–57]. Nevertheless, the relationship between sleep and CF remains unexplored, as far as we are concerned. In this context, age is an important factor to be considered. In contrast to our findings of negative correlation between age, hours of sleep, and sleep quality, young athletes may have short sleep duration, low sleep quality, and delayed sleep onset, which may affect exercise performance [58]. Due to its diversity of exercise intensities and its dynamicity, CF may exert positive effects on sleep. Kirmizigil and Demiralp [59] showed that functional exercises, which share significant similarities with CF, may significantly improve sleep quality in women diagnosed with primary dysmenorrhea. The importance of sleep seems to be fundamental to athletes’ recovery and performance [52]. Interestingly, diverging from society’s belief, recent evidence showed that poor sleep quality is not an independent risk factor for physical training-related injuries in adult athletic populations [60].

Limitations of the study

This study brings out unreported information regarding CFPs’ practices. However, our data should be analyzed cautiously, due to some limitations, such as small sample size, cross-sectional design, snowball sampling method to collect data, and the sole use of questionnaires.

Conclusions

CrossFit practitioners reported prevalent (77.7%) use of dietary supplements, especially among RX and Elite athletes, 5 or more times per week. The main reasons for using dietary supplements included increasing exercise performance and increasing muscle mass. Whey protein was the most used supplement, followed by creatine. The most supplement use-related factors were being male, poor sleep quality, RX level, and cognitive restraint. However, CrossFit practitioners lack nutrition education regarding the appropriate use of dietary supplements. Given the exploratory and descriptive nature of the study, more research is necessary to elucidate aspects related to dietary supplements and CrossFit practitioners.

Acknowledgements

All the authors are grateful to the research participants and the Centro Universitário São Camilo.

Author contribution

MVLSQ and FPN generated the research question. MVLSQ, LC, RBC, and LSO planned the collection. MVLSQ, CGM, and ACOM performed the literature search. MVLSQ and ACOM tabulated the data. MVLSQ performed the analysis statistic. MVLSQ, CGM, and FPN interpreted the findings. MVLSQ, CGM, and FPN wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RVTS critically reviewed this and previous drafts. All the authors contributed and approved the final draft for submission.

Data availability

The data is available from the corresponding author and can be accessed upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee of Centro Universitário São Camilo approved this study. The committee’s statement number is 4,165,399.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Glassman G. Understanding CrossFit. CrossFit Journal. 2007;56:2. http://library.crossfit.com/free/pdf/CFJ_56-07_Understanding.pdf. Accessed 9 Feb 2023.

- 2.CrossFit. What is CrossFit? CrossFit Journal. 2002. http://journal.crossfit.com/2004/03/what-is-crossfit-mar-04-cfj.tpl. Accessed 9 Feb 2023.

- 3.CrossFit. Scaling CrossFit workouts. CrossFit Journal. 2015. https://journal.crossfit.com/article/cfj-scaling-crossfit-workouts. Accessed 9 Feb 2023.

- 4.CrossFit. Scaling: how less can be more. CrossFit Journal. 2009. http://journal.crossfit.com/2009/06/scaling-how-less-can-be-more.tpl. Accessed 9 Feb 2023.

- 5.CrossFit. What is CrossFit's diet recommendation? CrossFit Journal. 2002. https://www.crossfit.com/faq/nutrition. Accessed 9 Feb 2023.

- 6.Maxwell C, Ruth K, Friesen C. Sports nutrition knowledge, perceptions, resources, and advice given by certified CrossFit trainers. Sports (Basel). 2017;5:1–9. doi: 10.3390/sports5020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maughan RJ, Burke LM, Dvorak J, Larson-Meyer DE, Peeling P, Phillips SM, et al. IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28:104–125. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. American College of Sports Medicine Joint Position Statement. Nutrition and athletic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:543–68. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cadegiani FA, Kater CE, Gazola M. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of high-intensity functional training (HIFT) and overtraining syndrome: findings from the EROS study (The EROS-HIFT) J Sports Sci. 2019;37:1296–1307. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2018.1555912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gogojewicz A, Sliwicka E, Durkalec-Michalski K. Assessment of dietary intake and nutritional status in CrossFit-trained individuals: a descriptive study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pietrowsky R, Straub K. Body dissatisfaction and restrained eating in male juvenile and adult athletes. Eat Weight Disord. 2008;13:14–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03327780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James BL, Loken E, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. The weight-related eating questionnaire offers a concise alternative to the three-factor eating questionnaire for measuring eating behaviors related to weight loss. Appetite. 2017;116:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson F, Wardle J. Dietary restraint, body dissatisfaction, and psychological distress: a prospective analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:119–125. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Compeau A, Ambwani S. The effects of fat talk on body dissatisfaction and eating behavior: the moderating role of dietary restraint. Body Image. 2013;10:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen JK, Burke LM, Ackerman KE, Blauwet C, Constantini N, et al. IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:687–697. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garthe I, Maughan RJ. Athletes and supplements: prevalence and perspectives. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28:126–138. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pillitteri JL, Shiffman S, Rohay JM, Harkins AM, Burton SL, Wadden TA. Use of dietary supplements for weight loss in the United States: results of a national survey. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:790–796. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brisebois M, Kramer S, Lindsay KG, Wu CT, Kamla J. Dietary practices and supplement use among CrossFit(R) participants. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2022;19:316–335. doi: 10.1080/15502783.2022.2086016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dos Santos Quaresma MVL, Guazzelli Marques C, Nakamoto FP. Effects of diet interventions, dietary supplements, and performance-enhancing substances on the performance of CrossFit-trained individuals: a systematic review of clinical studies. Nutrition. 2021;82:110994. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2020.110994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aguilar-Navarro M, Munoz-Guerra J, Plata MDM. Del Coso [Validation of a questionnaire to study the prevalence of nutritional supplements used by elite Spanish athletes] J Nutr Hosp. 2018;35:1366–1371. doi: 10.20960/nh.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baltazar-Martins G, Brito de Souza D, Aguilar-Navarro M, Munoz-Guerra J, Plata MDM, Del Coso J. Prevalence and patterns of dietary supplement use in elite Spanish athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2019;16:30. doi: 10.1186/s12970-019-0296-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natacci LCFJM. The three factor eating questionnaire - R21: tradução para o português e aplicação em mulheres brasileiras. Rev Nutr. 2011;24:11. doi: 10.1590/S1415-52732011000300002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knapik JJ, Steelman RA, Hoedebecke SS, Austin KG, Farina EK, Lieberman HR. Prevalence of dietary supplement use by athletes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46:103–123. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0387-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguilar-Navarro M, Baltazar-Martins G, Brito de Souza D, Munoz-Guerra J, Del Mar Plata M, Del Coso J. Gender differences in prevalence and patterns of dietary supplement use in elite athletes. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2021;92:659–68. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2020.1764469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reinert A, Rohrmann S, Becker N, Linseisen J. Lifestyle and diet in people using dietary supplements: a German cohort study. Eur J Nutr. 2007;46:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s00394-007-0650-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasiakos SM, McLellan TM, Lieberman HR. The effects of protein supplements on muscle mass, strength, and aerobic and anaerobic power in healthy adults: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2015;45:111–131. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morton RW, Murphy KT, McKellar SR, Schoenfeld BJ, Henselmans M, Helms E, et al. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:376–384. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cintineo HP, Arent MA, Antonio J, Arent SM. Effects of protein supplementation on performance and recovery in resistance and endurance training. Front Nutr. 2018;5:83. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall M, Trojian TH. Creatine supplementation. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12:240–244. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31829cdff2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Creatine supplementation and lower limb strength performance: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Sports Med. 2015;45:1285–1294. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanhers C, Pereira B, Naughton G, Trousselard M, Lesage FX, Dutheil F. Creatine supplementation and upper limb strength performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47:163–173. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper R, Naclerio F, Allgrove J, Jimenez A. Creatine supplementation with specific view to exercise/sports performance: an update. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2012;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momaya A, Fawal M, Estes R. Performance-enhancing substances in sports: a review of the literature. Sports Med. 2015;45:517–531. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green GA, Uryasz FD, Petr TA, Bray CD. NCAA study of substance use and abuse habits of college student-athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2001;11:51–56. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans MW, Jr, Ndetan H, Perko M, Williams R, Walker C. Dietary supplement use by children and adolescents in the United States to enhance sport performance: results of the National Health Interview Survey. J Prim Prev. 2012;33:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Havenetidis K. The use of creatine supplements in the military. J R Army Med Corps. 2016;162:242–248. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2014-000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claudino JG, Gabbett TJ, Bourgeois F, Souza HS, Miranda RC, Mezencio B, et al. CrossFit overview: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. 2018;4:11. doi: 10.1186/s40798-018-0124-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heikkinen A, Alaranta A, Helenius I, Vasankari T. Use of dietary supplements in Olympic athletes is decreasing: a follow-up study between 2002 and 2009. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2011;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feito Y, Burrows EK, Tabb LP. A 4-year analysis of the incidence of injuries among CrossFit-trained participants. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6:2325967118803100. doi: 10.1177/2325967118803100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hopkins BS, Li D, Svet M, Kesavabhotla K, Dahdaleh NS. CrossFit and rhabdomyolysis: a case series of 11 patients presenting at a single academic institution. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22:758–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bongiovanni T, Genovesi F, Nemmer M, Carling C, Alberti G, Howatson G. Nutritional interventions for reducing the signs and symptoms of exercise-induced muscle damage and accelerate recovery in athletes: current knowledge, practical application and future perspectives. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2020;120:1965–1996. doi: 10.1007/s00421-020-04432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papadopoulou SK. Rehabilitation nutrition for injury recovery of athletes: the role of macronutrient intake. Nutrients. 2020;12:1–17. doi: 10.3390/nu12082449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Close GL, Sale C, Baar K, Bermon S. Nutrition for the prevention and treatment of injuries in track and field athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019;29:189–197. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Annesi JJ, Mareno N. Indirect effects of exercise on emotional eating through psychological predictors of weight loss in women. Appetite. 2015;95:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Urbanek JK, Metzgar CJ, Hsiao PY, Piehowski KE, Nickols-Richardson SM. Increase in cognitive eating restraint predicts weight loss and change in other anthropometric measurements in overweight/obese premenopausal women. Appetite. 2015;87:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.12.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bryant EJ, Caudwell P, Hopkins ME, King NA, Blundell JE. Psycho-markers of weight loss. The roles of TFEQ disinhibition and restraint in exercise-induced weight management. Appetite. 2012;58:234–41. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Batsis JA, Apolzan JW, Bagley PJ, Blunt HB, Divan V, Gill S, et al. A systematic review of dietary supplements and alternative therapies for weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021;29:1102–1113. doi: 10.1002/oby.23110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rennie KL, Siervo M, Jebb SA. Can self-reported dieting and dietary restraint identify underreporters of energy intake in dietary surveys? J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1667–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaumberg K, Anderson DA, Anderson LM, Reilly EE, Gorrell S. Dietary restraint: what's the harm? A review of the relationship between dietary restraint, weight trajectory and the development of eating pathology. Clin Obes. 2016;6:89–100. doi: 10.1111/cob.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stinson EJ, Graham AL, Thearle MS, Gluck ME, Krakoff J, Piaggi P. Cognitive dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger are associated with 24-h energy expenditure. Int J Obes (Lond) 2019;43:1456–1465. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0305-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fullagar HH, Skorski S, Duffield R, Hammes D, Coutts AJ, Meyer T. Sleep and athletic performance: the effects of sleep loss on exercise performance, and physiological and cognitive responses to exercise. Sports Med. 2015;45:161–186. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;9:151–161. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S134864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chennaoui M, Arnal PJ, Sauvet F, Leger D. Sleep and exercise: a reciprocal issue? Sleep Med Rev. 2015;20:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonnar D, Bartel K, Kakoschke N, Lang C. Sleep interventions designed to improve athletic performance and recovery: a systematic review of current approaches. Sports Med. 2018;48:683–703. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0832-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kovacevic A, Mavros Y, Heisz JJ, Fiatarone Singh MA. The effect of resistance exercise on sleep: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:52–68. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vanderlinden J, Boen F, van Uffelen JGZ. Effects of physical activity programs on sleep outcomes in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:11. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-0913-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fox JL, Scanlan AT, Stanton R, Sargent C. Insufficient sleep in young athletes? Causes, consequences, and potential treatments. Sports Med. 2020;50:461–470. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirmizigil B, Demiralp C. Effectiveness of functional exercises on pain and sleep quality in patients with primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;302:153–163. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dobrosielski DA, Sweeney L, Lisman PJ. The association between poor sleep and the incidence of sport and physical training-related injuries in adult athletic populations: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2021;51:777–793. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01416-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available from the corresponding author and can be accessed upon request.