Abstract

Aims:

To assess the impact of anxiety and depression in the risk of converting to glaucoma in a cohort of glaucoma suspects followed over time.

Methods:

The study included a retrospective cohort of subjects with diagnosis of glaucoma suspect at baseline, extracted from the Duke Glaucoma Registry. The presence of anxiety and depression was defined based on electronic health records (EHR) billing codes, medical history and problem list. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional-hazards models were used to obtain hazard ratios for the risk of converting to glaucoma over time. Multivariable models were adjusted for age, gender, race, intraocular pressure measurements over time, and disease severity at baseline.

Results:

A total of 3,259 glaucoma suspects followed for an average of 3.60 (2.05) years were included in our cohort, of which 911 (28%) were diagnosed with glaucoma during follow-up. Prevalence of anxiety and depression were 32% and 33%, respectively. Diagnoses of anxiety, or concomitant anxiety and depression were significantly associated with risk of converting to glaucoma over time, with adjusted HRs (95% CI) of 1.16 (1.01, 1.33), and 1.27 (1.07, 1.50), respectively.

Conclusion:

A history of anxiety or both anxiety and depression in glaucoma suspects was associated with developing glaucoma during follow-up.

Keywords: Glaucoma, Epidemiology, Public health

INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible vision loss worldwide,[1] and due to its chronic, progressive nature, often imposes a psychological burden on patients.[2,3] Upon a glaucoma diagnosis, patients often fear going blind and are overcome with negative emotions,[4] and furthermore have increased odds of inpatient hospitalization, higher annual cost of care, falls, and driving accidents.[5]

Numerous population-based studies have shown an association between glaucoma and psychiatric disorders, most often depression and anxiety.[6–12] Among studies of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) patients, the prevalence of depression and anxiety ranges from 13-30% and 6-25%, respectively.[12] In a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) sample, glaucoma was significantly associated with depression after adjustment for demographics,[13] and in a study of a large health system, glaucoma patients were 10.6 and 12.3 times more likely to have depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively.[12] In glaucoma patients, older age, unmarried status, and increased medical comorbidity were associated with depression, and younger age, female sex, and lower socioeconomic status were associated with anxiety.[10,14] Longer follow-up and worse disease severity have been shown to be associated with depression,[15] and in a longitudinal study, faster visual field progression was associated with the occurrence of depressive symptoms.[11]

While there is substantial evidence, the role of psychiatric disorders in glaucoma remains complicated. Although they may certainly be a consequence of visual loss and glaucoma diagnosis, they may also contribute to disease progression over time. To this end, it has been shown that depression decreases glaucoma medication adherence[16], which is known to be associated with faster visual field progression.[17] In addition, recent evidence has shown in non-human primates that intraocular pressure (IOP) increases with stress,[18] a finding that may have important ramifications in the relationship between anxiety and glaucoma.

In this study, we investigated a large cohort of glaucoma suspects to better understand the effect of anxiety and depression on progression to a diagnosis of glaucoma. The study cohort is curated from electronic health records (EHR), leveraging systemic data to observe clinical processes at a large scale. We hypothesized that the presence of anxiety and depression upon a glaucoma suspect diagnosis would be associated with an increased risk of developing glaucoma during follow-up.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients from the Duke Glaucoma Registry which consisted of adults at least 18 years of age with glaucoma or glaucoma suspect diagnoses who were evaluated at the Duke Eye Center or its satellite clinics from 2012 to 2019. The Duke University Institutional Review Board approved this study with a waiver of informed consent due to the retrospective nature of this work. All methods adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects and were conducted in accordance with regulations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Information on comprehensive ophthalmic examinations from baseline and follow-up visits were collected including patient diagnosis codes (ICD, International Classification of Diseases), procedures (CPT, Current Procedural Terminology), medical history, and problem list. IOP was measured using the Goldmann applanation tonometry (Haag-Streit, Konig, Switzerland) and the Tono-Pen (Reichert, Inc, Depew, NY). Standard automated perimetry (SAP) tests were acquired with the Humphrey Field Analyzer (HFA, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, CA) during the study period. Only 24-2 and 30-2 Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm or full threshold tests of the HFA with size III white stimulus were exported from the database. Visual fields were excluded if they had >33% fixation losses or >15% false-positive or false-negative errors.

Patients were included in the study if they had a glaucoma suspect diagnosis, based on ICD codes version 9 or 10 (online supplementary eTable 1), at baseline. We excluded patients if they had any ICD code indicative of diagnosis of glaucoma prior to the glaucoma suspect diagnosis. In addition, patients were excluded if they had procedures or diseases that could confound SAP results. These included: treatment with pan-photocoagulation according to CPT codes, any diagnosis of retinal detachment, retinal or choroidal tumors, disorders of the optical nerve and visual pathways, inflammations including endophthalmitis, uveitis, focal chorioretinitis, and iridocyclitis, amblyopia and venous or arterial retinal occlusion according to ICD codes (online supplementary eTable 1). Finally, to be included in the cohort, patients were required to have a baseline visual field and IOP measurement within one-year of the baseline suspect diagnosis and prior to any glaucoma diagnosis.

Glaucoma outcome

A diagnosis of glaucoma during follow-up was defined at the patient level based on ICD codes (online supplementary eTable 1). If a diagnosis of glaucoma did not occur during the study period, patients were considered censored. The follow-up stopped at the end of 2019, so all patients without a glaucoma diagnosis at the end of follow-up were censored at January 1, 2020. Since we are interested in a time-to-event analysis, we recorded the time from a baseline glaucoma suspect diagnosis until the first appearance of a diagnosis of glaucoma in the chart, in years from baseline.

Psychiatric measures

Patients were categorized into psychiatric diagnoses based on billing data, including ICD codes, medical history, and problem list based on validated algorithms for identifying anxiety,[19,20] and depression.[21] To be classified as having anxiety or depression, at least one of the indications had to be present in a patient’s EHR data in the five years prior to the baseline glaucoma suspect diagnosis (online supplementary eTable 2). Throughout the manuscript, we analyze three definitions of the psychiatric diagnoses, 1) anxiety vs. no anxiety, 2) depression vs. no depression, and 3) no psychiatric diagnoses, anxiety only, depression only, and both anxiety and depression. The first two are binary indicators, and the last is a mutually exclusive four level categorical variable.

Statistical analysis

We investigated the impact of diagnoses of anxiety, depression or both on the risk of developing glaucoma during follow-up. To assess the impact of baseline risk factors on an eventual diagnosis of glaucoma, standard time-to-event techniques were employed. In particular, we estimated hazard ratios (HR), which represent an instantaneous risk of an event occurring at a particular time in the follow-up period. Cumulative HR curves are presented using Kaplan-Meier curves, with confidence intervals (CI) calculated on the logarithmic scale using Greenwood’s formula and p-values obtained from the log-rank test.[22,23] Furthermore, both univariable and multivariable Cox regression models were used. Multivariable models were adjusted for potential confounding factors, including age, gender, race, IOP measurements over time and baseline disease severity, as measured by SAP mean deviation (MD). For the eye-specific variables IOP and MD, we averaged measurements from both eyes. Adjusted HRs were obtained from the multivariable models, with IOP encoded as a time-dependent covariate.[24] To allow meaningful comparison and interpretation of HRs, all continuous variables were standardized.

Summaries are presented across psychiatric groups at baseline. Continuous baseline variables are presented as mean and standard deviation and categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. In addition to baseline variables, we also presented summaries of IOP throughout follow-up and among patients ultimately diagnosed with glaucoma, and SAP MD at the time of event. IOP measures throughout follow-up were summarized as mean, peak, and fluctuation IOP. Fluctuation IOP was defined as the range of IOP across follow-up.[25] All analyses were performed using the R programming language (Version 3.5.1, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) within the Protected Analytics Computing Environment (PACE), a highly protected virtual network space developed by Duke University for analysis of identifiable protected health information. The type 1 error was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

The cohort consisted of 3,259 patients with diagnosis of glaucoma suspect at baseline and followed for an average of 3.60 (2.05) years. Table 1 presents clinical and demographic characteristics at baseline across psychiatric groups. Overall in our cohort, the mean (SD) age at baseline was 60.0 (14.2) years, 58% were female, and 57% self-identified themselves as Caucasian/white, while 34% self-identified as African American/Blacks. Of the 3,259 patients, 1,015 (32%) patients had anxiety and 1,057 (33%) had a diagnosis of depression. A total of 1,465 (46%) patients had either depression or anxiety, while 607 (19%) had both anxiety and depression.

Table 1:

Summary statistics for study cohort presented across mutually exclusive psychiatric diagnosis groups (None = no psychiatric diagnosis, Anxiety = anxiety only, Depression = depression only, Both = anxiety and depression). Summaries are mean and standard deviation (SD), unless otherwise noted. P-values represent hypothesis tests across psychiatric groups, with categorical variables tested using a Chi-square test, and continuous variables tested using ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis, depending on normality.

| Variable | None | Anxiety | Depression | Both | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1,794 (55%) | 408 (13%) | 450 (14%) | 607 (19%) | |

| Glaucoma Diagnosis (%) | 0.013a | ||||

| Censored | 1,318 (73%) | 295 (72%) | 330 (73%) | 405 (67%) | |

| Glaucoma | 476 (27%) | 113 (28%) | 120 (27%) | 202 (33%) | |

| Baseline Age (years) | 59.61 (14.56) | 61.2 (13.69) | 60.1 (14.01) | 60.32 (13.73) | 0.209b |

| Gender (%) | <0.001a | ||||

| Male | 866 (48%) | 174 (43%) | 157 (35%) | 177 (29%) | |

| Female | 928 (52%) | 234 (57%) | 293 (65%) | 430 (71%) | |

| Race (%) | <0.001a | ||||

| Caucasian/White | 981 (55%) | 242 (59%) | 264 (59%) | 385 (63%) | |

| African American/Black | 634 (35%) | 139 (34%) | 155 (34%) | 192 (32%) | |

| Asian | 117 (7%) | 13 (3%) | 16 (4%) | 8 (1%) | |

| Multiracial | 34 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 6 (1%) | 10 (2%) | |

| Other | 28 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 12 (2%) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | 0.081a | ||||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 1,762 (98%) | 403 (99%) | 435 (97%) | 598 (99%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 32 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 15 (3%) | 9 (1%) | |

| Baseline IOP (mm Hg) | 16.86 (4.36) | 16.94 (4.15) | 16.86 (3.98) | 16.81 (3.89) | 0.977b |

| Baseline MD (dB) | −2.96 (4.56) | −3.20 (5.41) | −3.69 (5.01) | −3.77 (5.27) | <0.001c |

| Total Follow-up (years) | 3.64 (2.03) | 3.61 (2.1) | 3.68 (2.04) | 3.43 (2.07) | 0.108c |

| IOP Visits | 0.039c | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.16 (3.8) | 4.76 (4.98) | 4.61 (3.83) | 4.34 (3.84) | |

| Median [Min, Max] | 3 [1, 37] | 3 [1, 42] | 4 [1, 24] | 3 [1, 37] | |

| Mean IOP (mmHg) | 16.69 (3.65) | 16.74 (3.45) | 16.57 (3.35) | 16.58 (3.30) | 0.817b |

| Peak IOP (mmHg) | 18.94 (5.24) | 19.44 (5.46) | 18.98 (4.75) | 18.8 (4.45) | 0.237b |

| Fluctuation IOP (mmHg) | 4.19 (4.77) | 4.92 (5.34) | 4.50 (4.64) | 4.20 (4.16) | 0.075c |

| Time-of-Event MD (dB) | −4.71 (4.94) | −4.98 (5.87) | −5.18 (5.47) | −5.19 (5.78) | 0.958c |

Chi-square

ANOVA

Kruskal-Wallis; IOP = intraocular pressure; MD = mean deviation; SAP = standard automated perimetry.

From the 3,259 patients, 911 subjects (28%) received a diagnosis of glaucoma during follow-up. There was an association between a glaucoma diagnosis and psychiatric diagnosis groups at baseline (P = 0.013). Of note, 33% of patients with both anxiety and depression would eventually receive a glaucoma diagnosis. This p-value should be interpreted with care, because it does not account for the time-to-event nature of the data. In addition to glaucoma event status, we found that female and Caucasian/white patients had an increased risk of having a psychiatric diagnosis at baseline (both P < 0.001). Furthermore, in our cohort there was a significant association between baseline MD and psychiatric group (P < 0.001), with worse levels of MD for patients with a psychiatric diagnosis.

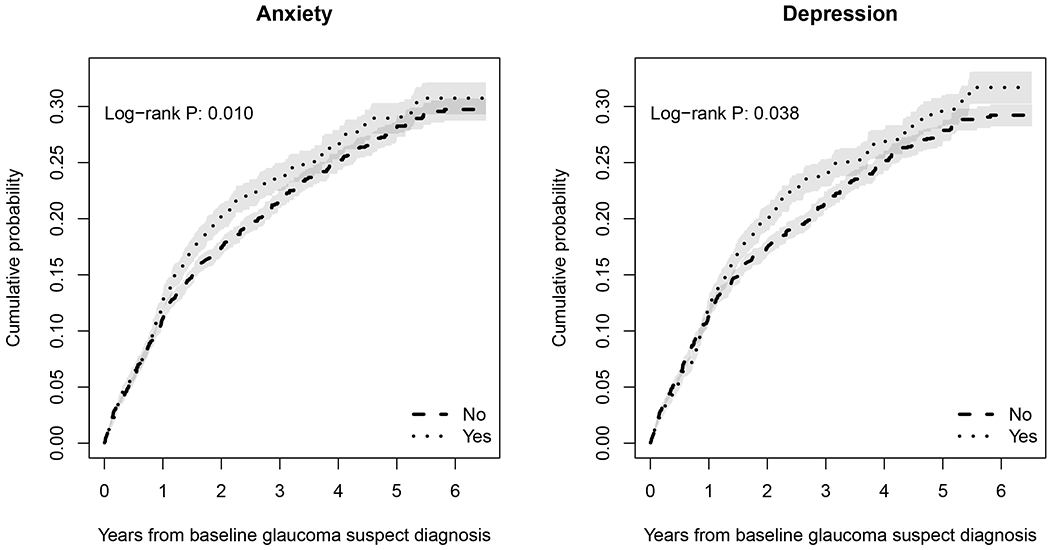

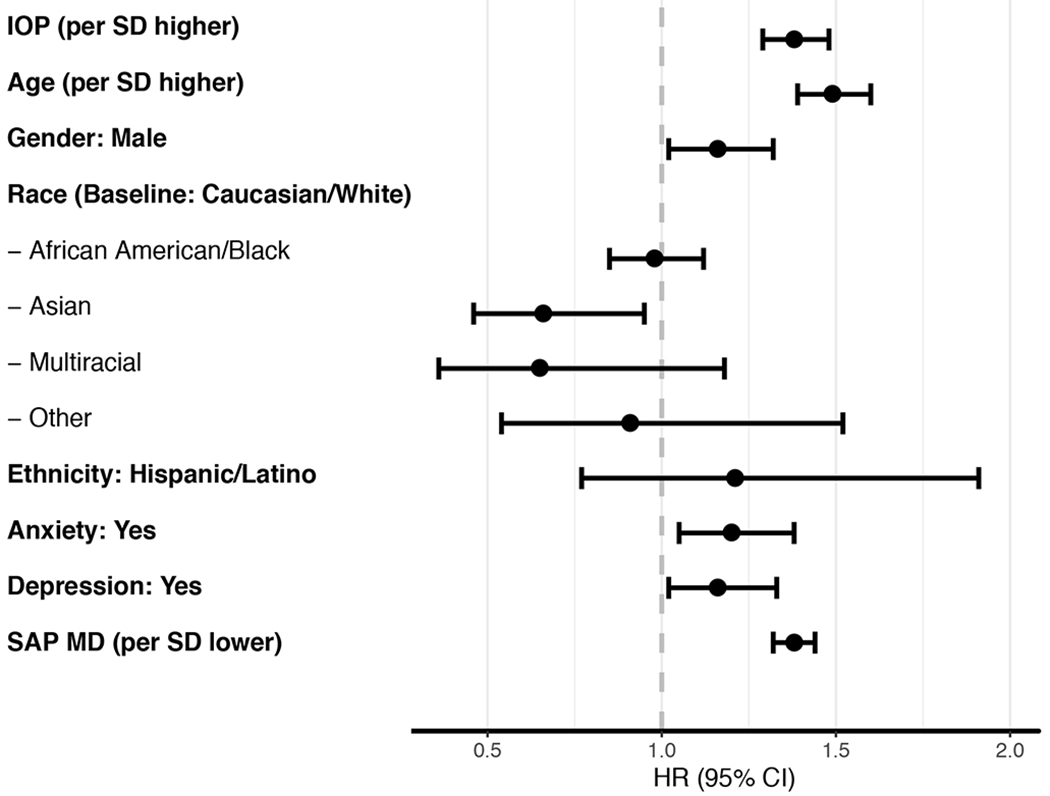

Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves for risk of developing glaucoma during follow-up for subjects with anxiety or depression. Table 2 shows univariable HRs for each putative factor for predicting risk of glaucoma over time. Glaucoma suspects with a diagnosis of anxiety at baseline carried a 20% increased risk of developing glaucoma (HR: 1.20; 95% CI: 1.04 – 1.37; P=0.010), while subjects diagnosed with depression had a 15% increased risk (HR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.01 – 1.32). Other factors significantly associated with development of glaucoma during follow-up in univariable models included older age, male gender, higher IOP and worse disease severity at baseline. Asian race was a protective factor. In Figure 2, these univariable HRs are presented as a forest plot.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier cumulative probability estimates for a diagnosis of glaucoma for patients with anxiety and depression.

Table 2:

Univariable Cox proportional hazards regressions for each risk factor individually. All hazard ratios (HR) for continuous risk factors are for a one standard deviation increase or decrease to put them on the same scale.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| IOP (per SD higher) | 1.38 (1.29, 1.48) | <0.001 |

| Age (per SD higher) | 1.47 (1.37, 1.57) | <0.001 |

| Gender: Male | 1.15 (1.01, 1.32) | 0.031 |

| Race (Baseline: Caucasian/White) | ||

| African American/Black | 0.99 (0.86, 1.14) | 0.892 |

| Asian | 0.64 (0.44, 0.92) | 0.017 |

| Multiracial | 0.64 (0.35, 1.16) | 0.142 |

| Other | 0.87 (0.52, 1.45) | 0.591 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic/Latino | 1.16 (0.74, 1.83) | 0.631 |

| Anxiety: Yes | 1.20 (1.04, 1.37) | 0.010 |

| Depression: Yes | 1.15 (1.01, 1.32) | 0.039 |

| Baseline SAP MD (per SD lower) | 1.36 (1.30, 1.42) | <0.001 |

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; IOP = intraocular pressure; MD = mean deviation; SAP = standard automated perimetry; SD = standard deviation.

Figure 2:

Forest plot of hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from models in Table 2.

Note: IOP = intraocular pressure; MD = mean deviation; SAP = standard automated perimetry; SD = standard deviation.

Table 3 shows results from multivariable models adjusting for age, gender, race, IOP measurements over time and SAP MD at baseline (i.e., the significant results from Table 2). We present three multivariable models that each contain different forms of the psychiatric disorders, 1) anxiety main effect only, 2) depression main effect only, and 3) a model with anxiety only, depression only, and both anxiety and depression. The effect of anxiety remained statistically significant in the multivariable model (Model 1), with HR (95% CI) of 1.16 (1.01, 1.33), while for depression it was no longer significant (Model 2). For patients with both anxiety and depression (Model 3), the effect was statistically significant, with HR (95% CI) of 1.27 (1.07, 1.50).

Table 3:

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regressions for significant variables from univariable analysis. As before, IOP is treated as a time-dependent covariate, to control for medication during follow-up. Models are presented with various forms of the psychiatric disorders. Each summary is a HR with 95% CI, where bold entries are significant.

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IOP (per SD higher) | 1.42 (1.33, 1.52) | 1.42 (1.33, 1.52) | 1.42 (1.33, 1.52) |

| Anxiety: Yes | 1.16 (1.01, 1.33) | --- | --- |

| Depression: Yes | --- | 1.14 (0.99, 1.31) | --- |

| Psychiatric Disorder (Baseline: None) | |||

| Anxiety: Only | --- | --- | 0.98 (0.80, 1.20) |

| Depression: Only | --- | --- | 0.96 (0.79, 1.18) |

| Both | --- | --- | 1.27 (1.07, 1.50) |

| Age (per SD higher) | 1.42 (1.33, 1.53) | 1.43 (1.33, 1.53) | 1.42 (1.33, 1.53) |

| Gender: Male | 1.14 (1.00, 1.30) | 1.14 (1.00, 1.30) | 1.14 (1.00, 1.31) |

| Race (Baseline: Caucasian/White) | --- | --- | --- |

| African American/Black | 1.09 (0.94, 1.26) | 1.09 (0.95, 1.26) | 1.09 (0.95, 1.26) |

| Asian | 0.90 (0.62, 1.30) | 0.90 (0.62, 1.30) | 0.91 (0.62, 1.31) |

| Multiracial | 0.73 (0.40, 1.33) | 0.74 (0.40, 1.34) | 0.74 (0.40, 1.35) |

| Other | 1.10 (0.66, 1.85) | 1.12 (0.66, 1.87) | 1.11 (0.66, 1.86) |

| Baseline SAP MD (per SD lower) | 1.34 (1.28, 1.41) | 1.34 (1.28, 1.41) | 1.34 (1.28, 1.41) |

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; IOP = intraocular pressure; MD = mean deviation; SAP = standard automated perimetry; SD = standard deviation.

Finally, we compare the prevalence of anxiety and depression in our cohort from baseline to time of event/censor, for both glaucoma and censored patients. Anxiety prevalence increases 13% among censored patients, while there is no change among patients ultimately diagnosed with glaucoma. Depression prevalence increased in both cohorts, by 10% in censored patients and 9% in patients ultimately diagnosed with glaucoma.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the presence of anxiety or concomitant depression increased the risk of developing glaucoma in a cohort of glaucoma suspects followed over time. Our findings suggest that approaches targeted at screening patients for coexisting psychiatric disorders may have a role in improving outcomes in glaucoma.

The overall prevalence of anxiety and depression in our cohort were relatively high, at 32% and 33%, respectively. For anxiety, this prevalence is on the upper end of values in the literature for glaucoma patients, most similar to a value of 30% reported in a cross-sectional study of Singaporean glaucoma patients.[26] In a similar EHR study that used ICD codes to define diagnoses, Zhang et al. reported a prevalence of 17% for anxiety and 22% for depression.[12] Our higher prevalence is likely due to the inclusion of the problem list and medical history for anxiety phenotyping, which is known to increase sensitivity.[21] Differences in prevalence of psychiatric conditions may also largely differ among populations and our numbers may reflect those of a population followed at a tertiary care clinic. Of note, our study uniquely assessed the prevalence of these conditions in a cohort of glaucoma suspect patients followed over time, while past work has largely been limited to examining their prevalence in samples that were already diagnosed with glaucoma. Finally, from baseline, the prevalence of depression in our cohort increased by 10% and 9% in patients who were censored and eventually diagnosed with glaucoma, respectively. While for anxiety, prevalence increased by 13% among censored patients, with no change observed in patients eventually diagnosed with glaucoma. The increase in depression prevalence is likely due to the known association between depression and older age among patients with glaucoma,[14] while the discordant changes in anxiety prevalence across censored and diagnosed patients is less clear, and needs to be studied further.

Our study indicates that a history of anxiety upon a glaucoma suspect diagnosis is significantly associated with a future diagnosis of glaucoma, with a multivariable adjusted HR (95% CI) of 1.16 (1.01, 1.33). While depression was associated with an increased risk of glaucoma in univariable models, 1.15 (1.01, 1.32), this association was no longer significant when controlling for baseline clinical measures. In multivariable models, the only significant association of depression occurred concomitantly with anxiety, 1.27 (1.07, 1.50).

Given that a diagnosis of anxiety or depression in our study occurred before an eventual diagnosis of glaucoma, our findings may suggest that anxiety is a predictive factor in developing glaucoma, not only a consequence of glaucoma. The reason why anxiety would be associated with worse outcomes in suspects is unclear. In our study, baseline IOP was not associated with a psychiatric diagnosis (Table 1, P = 0.977). However, when comparing IOP summaries during follow-up, fluctuation IOP was weakly associated with a psychiatric diagnosis (Table 1, P = 0.075), with anxiety patients having the largest fluctuation in IOP. Therefore, it is possible that the effect of anxiety may be explained through the impact of stress on IOP. Several studies have indicated that psychiatric stress is associated with elevation of IOP,[27–29] and this has been confirmed recently in a study of nonhuman primates.[18] More research is needed in this field, as these studies have looked primarily at acute stress which is likely different than stress attributed to chronic anxiety disorders. Nonetheless, the impact of stress on IOP is a likely biological pathway that may explain the significant association found in our study. To formally determine causation, however, would require a randomized clinical trial.

Although our study did not show a direct association of depression on a diagnosis of glaucoma in multivariable models, patients with concomitant anxiety and depression were significantly more likely to receive a diagnosis. In this context, an impact of depression could possibly be explained through medication adherence, which is known to decrease in depressed patients. In particular, Friedman et al. showed that patients with depression failed to take at least 75% of eyedrops.[16] Furthermore, it has been shown that depression is associated with worse glaucoma outcomes. In particular, Jampel et al. and Diniz-Filho et al. showed that depression is associated with worse vision-related quality of life and visual field progression, respectively.[2,11]

The relatively high prevalence of anxiety and depression and their significant relationship with risk of development of glaucoma found in our study suggest the need for an increased focus on understanding the coexistence of these conditions and their implications. In particular, our results support the suggestion of prior studies, including Zhang et al., that psychiatric assessment be routinely done in clinical care.[12] Also, they indicate the need for prospective studies specifically designed to elucidate the temporal relationship between these conditions.

Our study had limitations. While we utilized a large retrospective cohort, diagnoses were based on ICD codes extracted from EHR data. Such retrospective data may have missing values or be inaccurately coded. Coding was done by the attending physicians, without following prespecified guidelines other than general billing coding guidelines, and thus may differ from physician to physician. As such, many eyes classified as suspects at baseline may actually have had glaucomatous damage. Conversely, many eyes that were diagnosed as glaucoma during follow-up may have received such diagnosis based on factors not necessarily related to progression of structural and functional damage over time. Importantly, in patients who converted to glaucoma, the final SAP MD decreased to −4.71dB, indicating a significant worsening during follow-up. Of note, ICD-9 codes are not eye specific (i.e., are at the patient level) and therefore we cannot be sure which eye a diagnosis code corresponds to without a full chart review. To remedy this limitation, we required that patients included in our cohort (i.e., defined as a suspect at baseline) to not have any glaucoma diagnoses prior to the diagnosis of glaucoma suspect. By doing this we may be excluding eyes that are glaucoma suspects, where the patient’s other eye has glaucoma. But, we are guaranteeing to the best of our ability that our patients do not have one suspect eye and the other glaucomatous.

In addition, it is possible that patients may have been followed for psychiatric conditions outside of the Duke health care system and such information may not have been available in the EHR. Using medications and problem list, as performed in our study, has been shown to improve phenotyping in psychiatric disorders, however there is no substitute for a gold standard diagnostic test or patient-reported outcome survey.[30] Another consequence of using retrospective clinical data is that we do not have control over medical or surgical interventions during follow-up, which confounds inference. To account for the changing therapeutic routines, we used IOP as a proxy and treated IOP as a time-dependent covariate, which has been done before in glaucoma.[31,32] However, it should be noted that certain medications used to lower IOP, such as beta-blockers, may have an impact on mood disorders; although such an effect is likely to be small.[33]

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the presence of anxiety or anxiety and depression upon a glaucoma suspect diagnosis is associated with a future diagnosis of glaucoma after controlling for known risk factors. These findings suggest that approaches targeted at screening patients for coexisting psychiatric disorders may have a role in improving outcomes in glaucoma.

Supplementary Material

SYNOPSIS.

A history of anxiety or both anxiety and depression upon becoming a glaucoma suspect is associated with progression to a diagnosis of glaucoma, even after controlling for measures of disease severity.

Funding.

Supported by the National Science Foundation grants CCF-193496, DEB-1840223 (SM), DMS 17-13012 (SM), and ABI 16-61396 (SM), National Institute of Health grants R01 DK116187-01 (SM) and R21AG055777-01A (SM), Human Frontier Science Program RGP0051/2017 (SM), and National Eye Institute grant EY029885 (FAM). The sponsor or funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Competing Interests.

SIB, AAJ, SM, and TJS have nothing to disclose. FAM reports personal fees from Carl Zeiss Meditec, Heidelberg Engineering, Allergan, Reichert, Google, Aeri Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Biogen, Galimedix, Annexon, Stealth Biotherapeutic, Biozeus, and IDx; and a patent from nGoggle Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA 2014;311:1901–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jampel HD, Frick KD, Janz NK, et al. Depression and mood indicators in newly diagnosed glaucoma patients. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kong X, Yan M, Sun X, et al. Anxiety and depression are more prevalent in primary angle closure glaucoma than in primary open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2015;24:e57–e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odberg T, Jakobsen JE, Hultgren SJ, et al. The impact of glaucoma on the quality of life of patients in Norway: I. Results from a self-administered questionnaire. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2001. ;79:116–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prager AJ, Liebmann JM, Cioffi GA, et al. Self-reported function, health resource use, and total health care costs among Medicare beneficiaries with glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134:357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bramley T, Peeples P, Walt JG, et al. Impact of vision loss on costs and outcomes in medicare beneficiaries with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skalicky S, Goldberg I. Depression and quality of life in patients with glaucoma: a cross-sectional analysis using the Geriatric Depression Scale-15, assessment of function related to vision, and the Glaucoma Quality of Life-15. J Glaucoma 2008;17:546–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mabuchi F, Yoshimura K, Kashiwagi K, et al. High prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2008;17:552–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin H-C, Chien C-W, Hu C-C, et al. Comparison of comorbid conditions between open-angle glaucoma patients and a control cohort: a case-control study. Ophthalmology 2010;117:2088–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou C, Qian S, Wu P, et al. Anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with glaucoma: sociodemographic, clinical, and self-reported correlates. J Psychosom Res 2013;75:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diniz-Filho A, Abe RY, Cho HJ, et al. Fast visual field progression is associated with depressive symptoms in patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2016;123:754–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Olson DJ, Le P, et al. The association between glaucoma, anxiety, and depression in a large population. Am J Ophthalmol 2017;183:37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang SY, Singh K, Lin SC. Prevalence and predictors of depression among participants with glaucoma in a nationally representative population sample. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;154:436–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mabuchi F, Yoshimura K, Kashiwagi K, et al. Risk factors for anxiety and depression in patients with glaucoma. BrJ Ophthalmol 2012;96:821–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tastan S, Iyigun E, Bayer A, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in Turkish patients with glaucoma. Psychol Rep 2010;106:343–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman DS, Okeke CO, Jampel HD, et al. Risk factors for poor adherence to eyedrops in electronically monitored patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2009;116:1097–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman-Casey PA, Niziol LM, Gillespie BW, et al. The Association between Medication Adherence and Visual Field Progression in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study. Ophthalmology Published Online First: January 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jasien JV, Girkin CA, Downs JC. Effect of Anesthesia on Intraocular Pressure Measured With Continuous Wireless Telemetry in Nonhuman Primates. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci 2019;60:3830. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-27758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumenthal SR, Castro VM, Clements CC, et al. An Electronic Health Records Study of Long-Term Weight Gain Following Antidepressant Use. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:889. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marrie RA, Fisk JD, Yu BN, et al. Mental comorbidity and multiple sclerosis: validating administrative data to support population-based surveillance. BMC Neurol 2013;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trinh N-HT, Youn SJ, Sousa J, et al. Using electronic medical records to determine the diagnosis of clinical depression. Int J Med Inform 2011;80:533–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958;53:457–81. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bland JM, Altman DG. The logrank test. BMJ 2004;328:1073. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7447.1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.John D. Kalbfleish, Prentice RL The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asrani S, Zeimer R, Wilensky J, et al. Large Diurnal Fluctuations in Intraocular Pressure Are an Independent Risk Factor in Patients With Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2000;9:134–42. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200004000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim MC, Watnik MR, Imson KR, et al. Adherence to glaucoma medication: the effect of interventions and association with personality type. J Glaucoma 2013;22:439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grignolo FM, Bongioanni C, Carenini BB. Variations of intraocular pressure induced by psychological stress. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 1977;170:562–9.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/886797 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaluza G, Maurer H. Stress and intraocular pressure in open angle glaucoma. Psychol Health 1997;12:667–75. doi: 10.1080/08870449708407413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abe RY, Silva TC, Dantas I, et al. Can psychological stress elevate intraocular pressure in healthy individuals? Ophthalmol Glaucoma Published Online First: July 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2020.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro VM, Minnier J, Murphy SN, et al. Validation of Electronic Health Record Phenotyping of Bipolar Disorder Cases and Controls. Am J Psychiatry 2015;172:363–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bengtsson B, Leske MC, Hyman L, et al. Fluctuation of Intraocular Pressure and Glaucoma Progression in the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Ophthalmology 2007;114:205–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, et al. Predictors of Long-term Progression in the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Ophthalmology 2007;114:1965–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ko DT. β-Blocker Therapy and Symptoms of Depression, Fatigue, and Sexual Dysfunction. JAMA 2002;288:351. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.