Abstract

This paper serves to understand the influences of parents’ strategies on children’s e-commerce purchase influence via co-shopping and consumer socialization. As children are the original and perhaps most powerful online influencers understanding children’s influence is paramount to a successful e-commerce business. An exploratory qualitative study of 20 North American mothers with children between the ages 11–16 was conducted and data was analysed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Parents strategize children’s influence on e-commerce co-shopping through the techniques of promising, negotiating and educating and each approach has its own sub techniques such as wish lists, half and half purchasing and personal credit cards. This study shows the unique ways in which parents influence their children's e-commerce research and extends the findings on co-shopping from physical stores to the virtual arena. This study reveals valuable insights into how e-tailers can harness the influence of children on e-commerce purchases and mothers’ responses to them. This is the first study analyse parental strategies to children’s e-commerce purchases in the modern Internet arena.

Keywords: E-commerce, Children, Mothers, Co-shopping

Introduction

E-commerce, is the buying and selling of goods and services on the internet [20]. COVID-19 and the rise of the homebody economy have given greater prevalence to the possibility of e-commerce and co-shopping as businesses and consumers have increasingly gone digital,e-commerce’s share of global retail trade rose from 14% in 2019 to approximately 17% in 2020 [31]. Forty-three percent of children had made an online purchase, according to [29], p. 499, who also found that both parents and children accept that children's Internet usage for purchasing was primarily on an individual level rather than a family level because of security fears and a “lack of child interest in family related purchases.” However, these findings are outdated given the prolific changes that have occurred on the Internet, an e-commerce. An approximate 15–30% increase in consumers purchasing online has occurred [7]. In addition, the rise of COVID-19 and the homebody economy is forecasting global e-commerce sales of $6.4 trillion by 2024 [9]. With this increase in e-commerce shopping, co-shopping has grown to be a crucial element in the socialization of child consumers and how families make decisions. As children’s involvement in purchasing decisions is increasing, their voices are being increasingly heard by parents, governments, and researchers [13]. However, previous research on co-shopping was conducted in physical stores and does not apply to e-commerce. In addition, the studies on e-commerce co-shopping are outdated due to advances in Internet and mobile technology. This change presents the key motivation for this study as it creates a need for new research on children and parental co-shopping; children are the original “influencers” who have now moved to digital channels. A second motivation is that children have a significant influence on e-shopping, but studies in digital retailing only focus on individual decision making.

As e-commerce increasingly becomes more popular, understanding the influences of e-commerce shoppers is critical. However, given that the research into e-commerce co-shopping is practically non-existent, this study seeks to answer the following research question:

What strategies do mothers use in response to children’s e-commerce purchase influence?

Literature review

Co-shopping

Co-shopping, originally defined as “mothers shopping with children” ([14], p. 155), has evolved into shopping between any pair or group of people ([30], p. iii) broadened co-shopping into social shopping which is “a new phenomenon that allows more social interaction, participation, and satisfaction for customers while shopping online.” In addition, IGI Global defined co-shopping as “when individuals join consumption action, and such joint consumption action may not necessarily be contemporaneous as individuals can perform their respective parts at different times” (IGI [16]. Co-shopping may significantly affect business success as children have a significant influence on e-shopping, but studies in digital retailing only focus on individual decision making. This study focuses on co-shopping between parents and children in the e-commerce arena.

Grossbart et al. [14] identified four approaches to co-shopping with children: ignore or tolerate children, treat child co-shoppers as nuisances, capitalize on children as influencers, and to try to contribute to children’s socialization. An important highlight from this research is that parents can capitalize on children as influencers because they understand that they can learn from their children. In addition, while the fourth approach explicitly discusses contributing to children socialization, the other approaches also contribute to children’s’ socialization, as indirect methods. This is true even though mothers are not always intent on socialization every time they visit stores with children, and that co-shopping trips have simple singular causes. Companies that can understand co-shopping and its effects on consumer socialization are better poised to take advantage of co-shopping opportunities and the potentially strong effects of children as influencers.

To study the different types of co-shopping, Grossbart et. al. (1991) measured co-shopping frequency in terms of three different product categories such as groceries, children’s products, and general family needs. They found children’s influence differs depending on product category and that parents feel their children’s opinions should be included when purchasing automobiles, major appliances, furniture, groceries, vacations, life insurance, and general purchases. Many products in all these categories can be bought online, but e-commerce co-shopping has yet to be examined to see if previous research can be applied in a modern context.

Co-shopping and socialization

Consumer socialization is the process “by which young people acquire skills, knowledge, and attitudes to their functioning in the marketplace” ([33], p. 380). To acquire these many children are influenced through acts of co-shopping, typically with parental figures. “For most children, their exposure to the marketplace comes as soon as they can be accommodated as a passenger in a shopping cart at the grocery store” ([18], p. 192). This raises the question if the same theory applies to the e-commerce shopping cart? This question has not been addressed in the literature. As mothers and children co-shop, children are exposed to the marketplace and mothers are offered opportunities for delicate and explicit consumer socialization [14]. Co-shopping and socialization are highly interrelated, so these non-digital shopping studies provide a useful framework to explore how co-shopping affects the socialization of parents and children in digital shopping.

Consumer socialization theory “suggests that as children grow up and become consumers, their processing of cognitive and social stimuli depends on their age and family structure” ([15], p. 11). Therefore, the environment in which children learn to become consumers is heavily constituted by parents, friends, and mass media that act as socialization agents [15]. These socialization environments significantly affect how children grow up and their future purchasing behaviours.

As children are socialized as shoppers and subjected to the complexities of buying and spending at earlier ages than prior cohorts [12], their purchasing behaviours vary significantly as they age. Since children develop their own purchasing behaviours, it is probable that mothers who petition and consider children’s views on family purchases are more predisposed, to co-shop, to show children products, debate alternatives, and permit children to select among brands [14]. In addition, [6] found that while parents recounted often denying children’s demands, they also regularly asked children their preferences as they co-shopped.

Research originally adopted a unidirectional viewpoint by studying how parents socialize their children, but reverse socialization has grown in importance. Children have the potential to socialize their parents as “socialization is a lifelong process of preparing an individual to live within his or her own society” (Lumen, 2021). Reverse socialization relates to children’s ability to “influence their parents’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to consumption” ([32], p. 12). Shopping situations in which children influence parents is increasing as “87% [of parents] say their children influence purchase decisions” [23]. In Eksrtöm’s (2007, p. 207) study “interviews indicated that children had often introduced and made their parents aware of new trends (e.g., clothes) or relatively newly launched products (e.g., new spices, new types of pasta).” Most research focuses on children socialization in physical settings but given the drastic increase in e-commerce shopping, especially during the pandemic, there is need to examine children’s influence on parents and parents influence on children in e-commerce co-shopping.

Family decision making

The scholarship of how families make purchasing decisions has been significantly overhauled since the acceptance of children as influential figures. Children’s influential importance was continually dismissed as “most researchers in the area of family decision-making equated family decision-making with husband-wife decision-making [while excluding or ignoring] the roles of children” ([17], p. 413). However, the emphasis of children importance is seen by Keller and Ruus [19] who recognize that children learn from parents as well as teach them. Evolving societal structures and family compositions means that significant increases in the inclusion of children in family decision making are occurring as more children are being treated as equals within families and are being included more in family decisions.

Children are influential figures as each family member plays a different role in making purchase decisions. To begin to understand and utilize children’s’ influence potential, parents must recognize that children may have knowledge which their parents lack, and they may impart their understanding and knowledge and in turn so, sway their parents [12]. Children not only attempt to influence parents to get what they desire, but children’s influence affects family purchases. In a study of non-e-commerce shopping, John [18] suggests that children have the most influence in child relevant items, moderate influence in family activities, and the least influence in consumer durables and expensive items.

The extent at which children influence their parents, “seems reliant on at least two key factors, the child’s insistence, and the parent’s child-centeredness. “Examination of the flow of influence from the child to the parent shows that the child’s assertiveness is clearly related to the amount of input initiated at the child’s end of the communication channel” ([3], p. 70). Ekström [12] concluded that children contribute information for off-line purchases as well as installation and use. Past literature suggests that the influence of children’s input increases with age and has the potential to be extremely profitable for retailers [21].

In family decision making, knowledge sharing is critical as children sometime possess knowledge about purchasing and consumption that their parents lack [12]. Past literature focusses mainly on parents as primary communicators, but the inverse may also be true. There are now more cases of children influencing their parents,Cotte and Wood [10] found children expose their parents to new types of music while Ektröm (2007) found many children have exposed parents to different things that parents have admitted to liking somewhat. These studies illustrate the importance of family decision making to co-shopping experiences bringing into question how family decision making extends to e-commerce co-shopping.

Co-shopping in physical stores

Most co-shopping research has focused on physical stores. A study by Grossbart, et al. (1991) that focused on the influence of mothers on children looked at the frequency of co-shopping in terms of different categories and found that the three most notable promotional tactics for co-shopping are interactive merchandising, in-store promotions that appeal to mothers and children, and child-directed advertisements to foster in-store requests. These advertisements have the ability to increase sales and foster relationship building between consumers and products. However, these promotional tactics may “evoke negative reactions from mothers who think such methods undermine their own efforts to mediate marketing influence and communicate with children about consumption” (Grossbart, et. al., 1991, p. 161–162).

These promotional co-shopping efforts elicit child pester power purchasing requests. Pester power is when “children pose purchasing requests to their parents, pestering and unhappiness may result if those requests are denied” ([22], p. 561). Therefore, as children age and begin to understand the marketplace, debating turns out to be the most useful influence strategy [18]. While most parents strive for positive child development in marketplace transactions, there is potential for tension to result.

While literature touches on negative reactions to children pester power and purchase requests, further co-shopping research highlights children are much more likely to adhere to social norms than they are usually thought to do [13] as they do not like to be embarrassed. However ([13], p. 514) found despite tensions, “parents and children largely agreed that their co-shopping takes place in a relatively peaceful and for several even enjoyable manner.” While tensions can be undesirable, positive, and negative co-shopping experiences are necessary to contribute to children development and socialization.

However, little research has examined children's influence in an e-shopping environment and what research there is outdated given the prolific changes that have occurred on the Internet, and e-commerce.

Method

The qualitative method of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used as this approach “is committed to the examination of how people make sense of their lived experiences” ([26], p. 77). To do so, the personal experiences and individual perceptions of these experiences is explored [25].

It is suitable to develop theory in underdeveloped areas because it allows the researcher to go beyond the participants’ lived experience to create a theoretical explanation of the phenomenon. This is an advantageous approach for this study as IPA gives the “best opportunity to understand the innermost deliberation of the ‘lived experiences’ of research participants” ([1], p. 9).

IPA involves the researcher “making sense of the participant, who is making sense of X” ([27], p. 35). Therefore, the understanding of each mother on how their children affect their online purchasing is the central focus of this study. The following section discusses the methodological approach necessary to gaining an understanding about how children influence their parents’ e-commerce purchasing behaviours.

The participants, selection, and recruitment

The participants were 20 North American mothers ranging from 32 to 51 years in age. Historically, mothers have a great influence on family buying decisions and despite moves to more egalitarian shopping decisions it is felt that mothers are still the primary shoppers in a household. Twenty respondents are an adequate sample size as studies advise that theoretical saturation can be reached in qualitative research with samples of 10–12 participants [4]. Twenty respondents were adequate for data saturation to appear,this occurred when no new information was given by the final participants that altered the codes or themes [4]. Only mothers were chosen to ensure a homogenous sample as fathers have a different lived experience. They were each selected to have at least one child aged 11–16. This age range was selected to ensure that the children were young enough not to be allowed to make their own independent purchasing decisions online. To protect confidentiality, all names of participants and their children have been removed and replaced with pseudonyms. Each participant had sufficient financial resources to purchase a large variety of products online. A description of the participants is provided in Table 1. Interviews were conducted in January and February of 2022 during a later phase of the COVID pandemic.

Table 1.

Participant Details

| Participant | Age | Qualifying children with ages | Occupation | Marital status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lilly | 50 | 1-Age 14 | Foog service worker | Married |

| Taylor | 42 | 2-Age 15 & 12 | Educational Assistant | Married |

| Carmen | 41 | 1-Age 14 | Procurement buyer | Married |

| Mikayla | 44 | 1-Age 13 | Office assistant | Married |

| Madi | 42 | 1-Age 16 | Translator and Entrepreneur | Married |

| Brooke | 46 | 1-Age 14 | Lawyer | Married |

| Miranda | 44 | 1-Age 15 | Hair stylist and student | Married |

| Vanessa | 50 | 1-Age 16 | Office coordinator | Divorced |

| Raeden | 40 | 1-Age 12, 13, & 16 | Medical office assistant | Married |

| Kylah | 51 | 1-Age 14 | Sales representative | Married |

| Freda | 43 | 1-Age 12 | Stylist and beauty technician | Married |

| Michelle | XX* | 2-Age 11 & 15 | Food nutrition worker | Married |

| Mercedes | XX* | 2-Age 13 & 16 | Teacher | Married |

| Jean | XX* | 1-Age 14 | Business owner | Married |

| Janice | 32 | 1-Age 11 | Office manager | Married |

| Joann | 38 | 1-Age 15 | Entrepreneur hair stylist | Divorced |

| Kendall | 32 | 1-Age 14 | Entrepreneur, student, and lounge manager | Partnered |

| Brianna | XX* | 2-Age 11 &13 | Administrator | Partnered |

| Diane | 41 | 2-Age 11 & 16 | Administrative assistant | Married |

| Cheryl | XX* | 1-Age 13 | Educational assistant | Married |

*Indicates no comment on personal age

After receiving institutional ethics approval, participants were recruited through the researcher’s social media channels through snowball sampling. Interviews were conducted through Zoom because of the pandemic.

Interview format

Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with all participants. To begin, participants were asked if they could tell the researcher about themselves to gain an understanding into the demographic characteristics of each participant. Next, to have participants begin to think about the topic of shopping, they were asked if they prefer to shop in person or shop online, and to recall and classify how often they shop online. To narrow the focus of the interviews, participants were then asked to speak of instances in which they purchased something for their children online and how the purchase was influenced by their children. At the beginning of each interview, participants were encouraged to speak as much as they wanted in response to each question they were about to be asked. Interviews lasted an average of one hour.

Coding and analysis

The aim of coding was “to make an interpretative rendering that begins with coding and illuminates studied life” ([8], p. 43). Data analysis was guided by the strategies outlined by Smith et al. [26]. These included line-by-line analysis and coding of each participant’s responses and the identification of themes within and between participants. The initial findings were configured into an arrangement which permitted the analyzed data to be tracked precisely through the process, from the preliminary exploratory notes on the transcript, through advancing experiential reports to initial bunching and thematic development, into the final building of experiential themes [26].

The findings about how to understand co-shopping with children will be demonstrated through the different viewpoints of each participant. The findings of this study will be illustrated in the form of a framework which will describe the different strategies and the influencing factors that lead to different levels of control in the e-commerce environment. As each theme is intertwined, the findings will focus on the similarities between participant responses to help provide practical knowledge on the globally increasing market space that is e-commerce. Representative participant quotes will be used to provide evidence of the theme.

Findings

Children have significant influence on parents’ online purchasing decisions

A key finding was that children exhibit substantial influence over parents’ online purchasing decisions. Parents communicate with their children to make family purchasing decisions; they take their children’s opinions and preferences into account and usually make the final decision. This influence process usually starts with a request from the child for an online purchase. Parents note that purchase requests are triggered by a child’s exposure to a product or service through different social media channels. These include but are not limited to: Snapchat, TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram. These different social media channels which act as a new socialization agent. Living in the present-day Information Age, children are extremely susceptible to advertising influences and following trends. Mercedes explains the allure of social media for her son through stating:

That he comes across things on YouTube and that’s how he figures out what he wants.

Mothers favour Talking Out to negotiate online purchases with their children, as it allows for respectful conversation and tension mitigation between both parties. The child exerts some control as parents validate children voices and opinion, but the parents ultimately make the final purchasing decisions. With mutual respect between herself and her child, Lilly explains how her family makes these decisions:

So basically, we try and talk things out around here to come to a reasonable solution.

In some family structures, there is greater potential for tension to arise when children try to influence their parents’ online purchasing. However, like Gram and Grøhøj’s (2016) study, no mother indicated a significant disdain for co-shopping with her children. Mothers found Talking Out a useful way to mitigate tension when telling their children, “No.” Freda, highlights how she manages negative reactions:

If he does throw his hissy fit, then we kind of go our separate ways and then afterwards talk about it.

In summary, the mothers in this study acknowledge their child’s influence on online purchases. Participants use the approach of Talking Out with their children in response to purchase requests stemming from social media influences. However, parents adopt differing strategies to deal with the barrage of purchase requests they receive from their children.

Parents’ strategies for children’s influence: (from most parental control to least parental control)

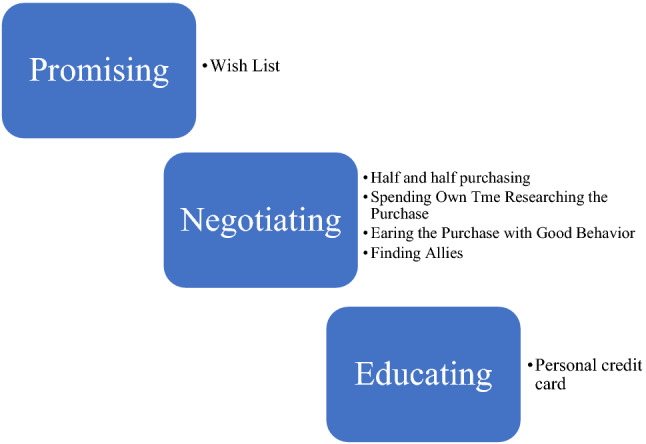

Parents adopt three strategies to deal with children’s purchase influence in e-commerce co-shopping. From the most parental control to the least parental control, these are: (a) promising, (b) negotiating, and (c) educating. These strategies and the accompanying techniques are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Parent’s Strategies for Children’s On-line Purchase Influence

Promising

To help manage potential conflict, promising is used by the mothers in this study. Promising involves deflecting; sometimes, parents hope that the request will be forgotten. This was highlighted by Miranda speaking about how she approaches certain situations with her children:

If you really really want that in a week from now, you know, I’ll consider it then, and then it usually goes away.

Promising is a conflict mitigation technique used by parents to prolong purchasing requests while managing children’s reactions. Through using promising as a deflection technique, parents are able to give themselves time to meet the purchase request but to also provide their children with hope. This is exemplified by Joan:

I told her that I had just got back from Hawaii, so I did not have an abundance of money to spend on football cleats in the off-season, but we will make it happen before she’s on the field again.

Promising, as deflection, can be further explained in terms of The Wish List technique. Amazon and other online retailers allow a favorites list or a wish list which facilitates promising deflection. The Wish List is a promising deflection technique that involves parents telling their children to add their purchase requests to their Wish List instead of responding with a definitive “no.” For those that choose promising deflection, telling children to add the request to their wish list is both a way to manage children’s expectations and a way to curate a list of children desires. Thus, digital retailing technology facilitates promising, as seen in the following statement by Janice:

I do think that I am more geared towards if you want something, then it gets added to the birthday list, or if the birthday’s passed, then the Christmas list.

E-tailers might want to expand their favorites/wish lists into categories like birthdays or other holidays for children and use technology to allow children to send “hints” to parents.

Promising is influenced by the price of the products and purchasing frequency. As current financial situations do not allow for expensive or frequent online purchasing, successful use of promising is vital in establishing ultimate control over children’s online purchases. Kendall, highlights how her current financial standing influences her choice to use The Wish List technique:

You don’t want to constantly be telling your kids you’re poor giving them that anxiety that we’re poor, but I’ll tell them that I don’t have the money right now or that these aren’t things that we need. If this is something that you want, we can put it on your list for your birthday or Christmas.

When using promising, the child perceives they have control, but control lies with the parent; numerous participants highlighted that their word is often final. This control is highlighted by Diane:

They don’t have access to any of the credit cards and if they need or want something, then they have to ask.

Therefore, through using the promising strategy, parents can plan for the future and how money will be spent by giving their children hope for the future. This gives children some degree of perceived control, in that they can curate their online wish lists. This strategy allows parents to avoid conflict while also maintaining control.

Negotiating

Negotiation is another strategic choice favored by both mothers and children. It was found that e-commerce purchasing situations arise where both mothers and children use negotiation to achieve their desires. From a parental point of view, negotiating with children is a useful technique that helps to illustrate acceptable and unacceptable purchases. Raeden, highlights her parental approach to using negotiation to reason with her child:

If you can give us the reasons why you believe you should have this, then we can talk about it.

Interestingly, negotiation is also a favored approach of children. Carmen illustrates this through stating:

He (son) likes to negotiate. ‘I’ll do this for you.’ If I can do this, and then he’ll throw it back on me when I want something and say, ‘I’m (son) saving for a car you know.’”

Negotiation techniques used by children when e-commerce co-shopping with their parents include the child spending their own money with half and half purchasing, the child spending their own time researching the purchase, earning their purchases with general “good” behavior and finding allies.

Half-and-half purchasing is favored by both mothers and children. This involves negotiation with one party offering to pay for half of the purchase in hopes that the other party will comply. Numerous participants mentioned successful use of this technique. For example, this success was exemplified by Mercedes:

Even when we bought the PlayStation 5, he paid for half of that because those things are impossible to find. So, he had been wanting one for a while, and we had said, if you can find one then yes, we’ll pay for half of it.”

In the child spending their own time researching the purchase the child will search online for the item. Negotiation involves the child finding the items online, at a specific price, (e.g., doing the work) and then the parent will pay. Taylor (42) highlighted that she is more willing to purchase products if their child comes to her with the research already conducted:

I mean she did the research; she did the homework. She sent me the link and I just had to put in my credit card.

The child can only do the searching/information work because the child can do it online; they cannot drive to the mall and compare prices that way This extends half-and-half purchasing to half-and-half in time, trouble, and information search.

Another strategic choice in negotiating is Earning Purchases. Instead of immediately granting or outright denying purchases, mothers will often tell their children that they can earn their requests. This can be in the form of a service exchange, having a positive attitude, or finding success in school. The key to finding success with this strategy is that children are not given an outright no and are instead given hope, similar to the deflection strategy of promising.

Raeden conceptualized this idea in the following:

It’s never a hard no. There’s been times where the no has changed, depending on what they’ve done school or housework wise or if they are willing to pay a portion of it.

Opposingly, Brianna speaks about her situational unwillingness to purchase things for her children:

It depends on what’s taken place in the days prior. If they’ve had the right attitude or not it depends on what they’re asking for. If it’s the fifth or third time that he is asking me for some different videogame or whatever, it’s kind of like, no you’re tapped for the month.

The potential for a successful negotiation is highly influenced by the price of the products. While negotiation oftentimes leads to success for both parties, there are situations where negotiation does fail. Failed negotiations highlight ultimate control from a parental point of view as certain mothers are unwilling to entertain a negotiation. As price is a factor that influences value, Vanessa highlighted when she is unwilling to entertain negotiation:

Just the other day there was a pair of pants that she really wanted, and I said not for that amount of money, no way.

Earning Purchases results in negotiation as children think they are able to gain purchases but are ultimately controlled by their parents requiring them to earn it. However, as parents give the opportunity to earn purchases and leave it up to their children to complete the earn, each party has influence over the other. Therefore, understanding how to influence situations of earning purchases is crucial to capitalizing on these purchasing instances.

Successful and unsuccessful negotiation have effects on relationships between mothers and children. In successful negotiation, children are given a voice in the situation and have some control over the outcome. In failed negotiation, parents exert control as children are shut down and given no voice or validation. However even if children are immediately shutdown, this study has shown that many are willing to risk straining relationships with their mothers as most are still inclined to continue negotiating by “leaving hints.” Leaving hints can be seen as modern-day pester power as when “children pose purchasing requests to their parents, pestering and unhappiness may result if those requests are denied” ([22], p. 561). Taylor, explained that when told no, her child will:

Hang on to it for a little while and keep throwing hints out here and there, or “please Mom, I really want this,” and I just ignore her.

The child when she wants more items will removes some items from her cart to negotiate with her mother; so she gets some of them. Mikayla, illustrates this:

We just sort of decide. What do you really need because usually her cart starts quite full, and then she kind of narrows it down to what she knows I will think is reasonable.”

Another negotiation strategy that was found to be used between mothers and children is that of Child Research Onus. Whether it is self-assumed, or a task given by parents, children are willing to research products themselves as it leads to greater purchase potential. Taylor highlighted that she is more willing to purchase products if their child comes to her with the research already conducted.

I mean she did the research; she did the homework. She sent me the link and I just had to put in my credit card.

Through creation of this purchasing ease, Taylor’s mother stated that within reason she has no issues buying her daughter products. Carmen however, is more inclined to validate the research:

He will research it, look into it, and come to me with ideas for where we can buy it, what’s the best price, and of course I validate it.”

Through this seeking of validation, Carmen and her son have been able to build a relationship based on trust. This trust influences Carmen’s willingness to purchase as she:

Knows that [she] can trust him because he does his research, and he doesn’t spend more than what [she’s] told him.

Through developing trusting relationships with their children, both Carmen and Taylor have developed control over their children. This trust is influenced through psychological reassurance as Carmen knows that her son will:

Read reviews on things too. He won’t ask if the reviews aren’t great.

Psychological reassurance relates to finding security in reviews, familiar websites, and reputable websites which ultimately lead to a greater willingness to purchase. The security found in reviews influences Carmen’s ability to trust her son and ultimately buy him purchases. Bordering on actual autonomy, both Carmen and Taylor are willing to give their children the freedom to research purchases, but still require the final say to press purchase. From a business perspective, understanding the foundation of trust between mothers and children is crucial as there is potential for further capitalization in e-commerce environments.

The last negotiating strategy is Finding Allies in father’s influence and sibling influence. Oftentimes, fathers have significant influence in children desires when it comes to videogames and products that are on sale. The e-commerce purchases of mothers are affected as a result. This is conceptualized by Carmen and Diane in the following respective statements:

They try not to work against me, but they have a plan of attack, so that they can get what they want, and in the end they both want the same thing.

My husband sends me these emails all the time and he goes they’re on sale, ask if the kids want anything.

It was also found that siblings also play a pivotal role in influencing children e-commerce desires. Based on the respect that younger siblings have for their older siblings, many children are influenced to ask for things if they feel that it will allow them to spend more time with their older siblings. Consequently, older siblings significantly influence what younger siblings want to and do not want to purchase. This was generalized as numerous participants talked about how they feel their younger children look up to their older siblings and alter their wants accordingly. Brianna illustrated this idea in the statement:

Especially if his big sister says, well that’s a stupid idea, he’s not going to want to buy it anymore.

Sibling influence not only affects child requests, but the willingness of mothers to grant purchase. In addition to influences from fathers, it was also found that mothers are more likely to grant purchases if they are reasonable and lead to spending more quality time with their siblings. This idea is seen by Freda in the following:

Him and his brother are two p’s in a pod and I’m going to say he definitely influences things that he would like.

The choice to use the Earning Purchases strategy is affected by purchase frequency. On one end, Jean speaks about her openness to purchasing things for her child:

I was 100% open to those purchases because he doesn’t ever ask for anything.

Educating

Parents are becoming more trusting to give their children the freedom to choose. This study has found the main approach mothers use educating their children on purchasing is granting personal credit cards. While it is a relatively new concept, VISA debits and giving children credit cards that are secondary to personal accounts, are becoming valid methods to educating children on purchasing. Brooke highlights her reasoning for giving her child a credit card at 15 in the following:

The rule is, we got her the credit card so that we could teach her the good habits of never buying anything unless you have the money in your account and you’re able to make the payment immediately. So, use the card for convenience, but never have a balance on it.

The education technique is used by mothers to have children consider perspectives other than their own. Oftentimes, children desires are influenced externally by social media and keeping up with trends. As a result, Kylah summarizes her approach to dealing with her children wanting to conform to society:

I sit there and try to put you know my two-cents in. Why wouldn’t you want something different? Why do you want to be like everyone you know?

However, while opinions are offered Kylah still allows her children to make final purchase decisions as she believes in her children spending their money on things that they will enjoy.

Children have the potential to educate their parents as education can also be viewed as a lifelong process of training an individual to exist within his or her own society. Brooke, a repetitive sales shopper, spoke about the lessons she has learned from her daughter on her own shopping techniques. Originally, Brooke’s viewpoint on sales is that a good deal could not be left at the store, but she is working to change this perspective as her child is helping her to see that purchases are:

Not 50% off if you’re paying 100% more than what you would have been paying.

Through the strategy, the parent is trying to give control to the child, but in a way so that the child will make purchases in the same way (same values) as the parent. Each of the three parental education approaches result in a mixture of parental control and child control. By giving children secondary credit cards to personal accounts, it is perceived that the child has control. However, children are being granted access to credit cards and VISA debits earlier as developing trusting foundations is becoming increasingly more desired. In addition to the freedom to choose, this study has shown a trend towards greater child autonomy as VISA debits give children actual autonomy in purchasing. Therefore, as this concept is relatively scant, there is great value in further research to understand what influences those with actual autonomy to purchase.

Limitations and future research

The selection and gatekeeper bias in the convenience and snowball sampling must be recognized [2] and this does not allow us to generalize the study’s results to a wider population. This qualitative study aimed for vertical (i.e. generation of theory) rather than horizontal (i.e. applicability to other users and situations) generalizability [5]. The timeframe of this study should also be acknowledged as a possible limitation, given the prevalence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings may be unique to the COVID period when e-commerce sales grew exponentially, alternatively they could be a microcosm of what the future of e-commerce co-shopping holds as e-commerce sales continue to grow.

The singular focus on English-speaking North American mothers adds a cultural bas to the results so future research can focus on the perspectives of both fathers and younger children across different cultural backgrounds. Finally, only mothers were interviewed and the child and father’s perspectives were not gathered. The gender bias this introduces in the results and the neglect of triadic relationships between children, mothers and fathers must be recognized. This reliance on single respondent data means the triad of family relationships was not investigated and inferences were based on the mother’s perception of them.

Concluding comments

Retailers are increasingly realizing the importance of children in e-commerce co-shopping decisions [11] and this study shed light on the ignored area of the process of decision making in e-commerce co-shopping between parents and children. It finds e-commerce influences co-shopping in unique ways compared to past research based upon co-shopping in physical stores. The digital world of e-shopping changes and facilitates children’s influence on their family’s purchases. E-commerce capitalizes on children as influencers and contributes to children’s socialization. E-commerce has given rise to “increased communications within families leading to more learning” ([10], p. 80) and more reverse socialization [32] occurs as children researching their own purchases gives them use the “power of expertise” ([28], p. 45.).

Overall, most participants spoke about how they feel their children are respectful of whatever answer they receive to their purchasing requests which is similar to previous literature by ([13], p. 514) that states despite tensions, “parents and children largely agreed that their co-shopping takes place in a relatively peaceful and for several even enjoyable manner.” As a result of the trend towards trusting children, numerous present-day relationships between mothers and children are found to be based more on trust rather than previous generational parenting style beliefs that “equated family decision-making with husband-wife decision-making [while excluding or ignoring] the roles of children” ([17], p. 413).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alase A. The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach. International Jounral of Education & Literacy Studies. 2017;5(2):9–19. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson, R. and J. Flint. (2001), “Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies”, Social Research Update, 33 https://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU33.html

- 3.Berey L, Pollay R. The influencing role of the child in family decision making. Journal of Marketing Research. 1968;5(1):70–72. doi: 10.1177/002224376800500109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boddy CR. Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research. 2016;19(4):426–432. doi: 10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2013), Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for Beginners. Sage.

- 6.Carruth B, Skinner J, Moran J, III, Coletta F. Preschoolers' food product choices at a stimulated point of purcahse and mothers' consumer practices. Journal of Nutrition Education. 2000;32(3):146–151. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(00)70542-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charm, T., Coggins, B., Robinson, K. and Wilkie, J. (2020, August 4), The great consumer shift: Ten charts that show how US shopping behavior is changing. Retrieved from McKinsey & Company: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/the-great-consumer-shift-ten-charts-that-show-how-us-shopping-behavior-is-changing

- 8.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppola, D. (2021, October 13), Global number of digital buyers 2014–2021. Retrieved from Statista: https://www.statista.com/statistics/251666/number-of-digital-buyers-worldwide/#:~:text=Global%20number%20of%20digital%20buyers%202014%2D2021&text=In%202021%2C%20over%202.14%20billion,global%20digital%20buyers%20in%202016.

- 10.Cotte J, Wood S. Families and innovative consumer behavior: A triadic analysis of sibling and parental influence. Journal of Consumer Research. 2004;31(1):78–96. doi: 10.1086/383425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deighton, K. (2022). “Hollister lets teens send their online carts to parents for checkout,” The Wall Street Journal, October 11, https://www.wsj.com/articles/hollister-lets-teens-send-their-online-carts-to-parents-for-checkout-11665482401

- 12.Ekström K. Parental consumer learning or 'keeping up with the children'. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. 2007;6(4):203–217. doi: 10.1002/cb.215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gram M, Grønhøj A. "Meet the good child." Childing' practices in family food co-shopping. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 2016;40(5):511–518. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossbart S, Carlson L, Walsh A. Consumer socialization and frequency of shopping with children. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 1991;19(3):155–163. doi: 10.1007/BF02726492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hota, M., and Bartsch, F. (2019). Consumer socialization in childhood and adolescence: Impact of psychological development and family structure. Journal of Business Research, Vol. 105 No. December, pp. 11–20.

- 16.IGI Global. (2021), What is Co-Shopping. Retrieved from IGI Global: https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/co-shopping/34184

- 17.R. L. Jenkins (1979). The Influence of Children in Family Decision-Making: Parents' Perceptions, in NA - Advances in Consumer Research Volume 06, eds. William L. Wilkie, Ann Abor, MI : Association for Consumer Research, pp. 413–418

- 18.John D. Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. Journal of Consumer Research. 1999;26(3):183–213. doi: 10.1086/209559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller M, Ruus R. Pre-schoolers, parents and supermarkets: Co-shopping as a social practice. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 2014;38(1):119–126. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan, A. (2016). Electronic commerce: A study on benefits and challenges in an emerging economy. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, Vol. 16 No.1.

- 21.Lackman C, Lanasa J. Family decision-making theory: An overview and assessment. Psychology & Marketing. 1993;10(2):81–93. doi: 10.1002/mar.4220100203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawlor M-A, Prothero A. Pester power - A battle of wills between children and their parents. Journal of Marketing Management. 2010;27(5/6):561–581. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Retail Federation. (2019, October 1). Consumer View Fall 2019. Retrieved from NRF: https://nrf.com/research/consumer-view-fall-2019

- 24.Palan, K. and Wilkes, R. (1997). Adolescent-Parent interaction in family decision making. Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 24 September, 159–169

- 25.Smith JA, Osborn M. Qualitative Psychology. SAGE Publishing Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative Phenomological Analysis Theory, Method and Research. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith JA, Flowers P, Michael L. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis Theory, Method and Research. SAGE Publishing Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thaichon, P. (2017). Consumer socialization process: The role of children's online shopping behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol 34, No. January, pp. 38–47.

- 29.Thomson E, Laing A. The net generation: Children and young people, the internet and online Shopping. Journal of Marketing Management. 2003;19(3/4):491–512. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Topaloglu, C. (2013). Shopping alone online vs. co-browsing: a physiological and perceptual comparison. Masters Theses, Retrieved from Scholars' Mine: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6375&context=masters_theses

- 31.UNCTAD. (2021, March 15). How COVID-19 triggered the digital and e-commerce turning point. Retrieved from UNCTAD: https://unctad.org/news/how-covid-19-triggered-digital-and-e-commerce-turning-point

- 32.Ward S. Consumer socialization. Journal of Consumer Research. 1974;1(2):1–14. doi: 10.1086/208584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward, Scott (1980). Consumer Socialization, in Perspectives in Consumer Behavior, Third Edition, Harold H. Kassarjian and Thomas S. Robertson, eds., Glenville, IL: Scott, Foresman and Company.