Summary

A parturient with VACTERL association (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, trachea‐oesophageal fistula, renal abnormalities and limb abnormalities) was listed for an elective caesarean section. She had a short neck with reduced cervical extension and flexion. Magnetic resonance imaging of her whole spine was performed which showed failure of cervical spine segmentation and cervical stenosis. Neuraxial blockade could have resulted in unpredictable spread of local anaesthetic due to the low volume of the spinal canal, and could have caused myelopathic changes within the spinal cord due to cerebrospinal fluid pressure changes. A general anaesthetic using a rapid sequence induction was also predicted to be challenging due to her fixed, unstable neck and severe cervical spine stenosis. After a multidisciplinary discussion Including neurosurgeons, we planned for awake tracheal intubation followed by general anaesthesia. However, before the date of her planned delivery, she required an urgent caesarean section due to severe preeclampsia. This was performed under general anaesthesia following uncomplicated awake tracheal intubation.

Keywords: anaesthesia, caesarean section, spinal stenosis, VACTERL association

Introduction

VACTERL association is a syndrome of congenital malformations. It occurs in 1 in 10,000 to 40,000 infants with male preponderance, making it an especially rare occurrence in the obstetric population. It is described by the presence of at least three of: vertebral defects; anal atresia; cardiac defects; tracheoesophageal fistula; renal abnormalities; and limb deformities, in the absence of other genetic diseases [1].

Although rare, neuraxial anaesthesia in patients with significant spinal stenosis can lead to progressive myelopathies due to the coning effect in addition to an unpredictable spread. Here, we report a case in which a patient with both VACTERL association and spinal stenosis required an urgent caesarean section.

Report

A nulliparous parturient with VACTERL association presented for antenatal management and was seen in both the obstetric and anaesthetic pre‐operative assessment clinics. She had undergone corrective surgery for congenital anal atresia at birth, so was not suitable for a vaginal delivery; elective caesarean section was therefore planned. In addition, she had a history of ventricular septal defect (VSD) which had been surgically repaired at 9 weeks of age, renal agenesis with normal renal function and talipes, which had been surgically corrected at age four. She did not have a tracheoesophageal fistula and she had a normal body mass index (BMI) at a height of 155 cm with a weight of 60 kg.

Her neurological examination was normal with no history of pain or radiculopathy. Airway examination identified good mouth opening and jaw protrusion with Mallampati class II. However, a short neck with no extension and limited flexion to 20 degrees was noted, highlighting a potentially difficult airway.

Due to her cardiac history, an antenatal echocardiogram was performed which showed a normal left ventricular size with septal wall hypokinesia and mild discoordination. The ejection fraction was approximately 55–60% and there was no evidence of residual VSD.

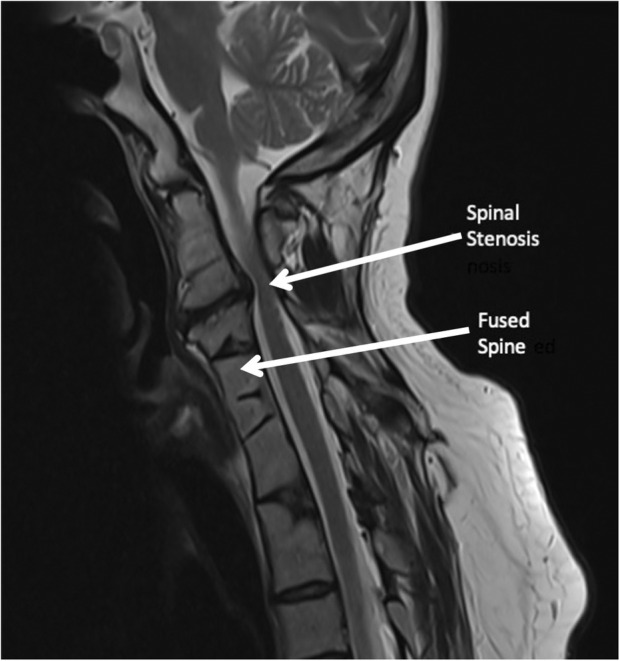

Regarding her congenital vertebral abnormalities, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her whole spine was undertaken, which showed previously undiagnosed failure of segmentation at multiple spinal vertebrae (C1–C3, C4–T1 and T1–T2), and a circumferential disc bulging at the C3–C4 interspace causing severe secondary spinal stenosis with increased signal, indicating early myelopathic changes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical and upper thoracic spine. Annotated are the fused vertebral bodies and significant spinal stenosis, which were previously undiagnosed.

Radiographs of her cervical spine were undertaken in flexion and extension, to inform the decision regarding positioning for laryngoscopy. These showed grade 1 retrolisthesis of C2 on C3, with C2 appearing to migrate anteriorly into grade 1 anterolisthesis on the flexion radiograph.

Following these investigations, a neurosurgeon was consulted; a high risk of progressive myelopathy in the case of dural puncture‐associated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage was noted. Though the risk of CSF leak due to dural puncture is rare, this needed to be balanced against the risk of general anaesthesia in an obstetric patient with a relatively fixed cervical spine and a potentially difficult airway. Following a discussion with the patient, we planned for an elective awake tracheal intubation with flexible bronchoscopy (ATI:FB).

At 35 + 2 weeks gestation, the patient presented to our labour ward with severe pre‐eclampsia, requiring delivery. An arterial canula was inserted and her blood pressure was controlled and optimised with intravenous magnesium and labetalol infusions. A remifentanil infusion for sedation was started using a target‐controlled infusion (TCI) pump programmed with the Minto pharmacokinetic model. The remifentanil infusion was titrated up from plasma site concentration (Cp) of 0.5 ng.ml−1 to a maximum Cp of 1.0 ng.ml−1. Xylometazoline 0/1% spray was used for nasal decongestion, followed by topicalisation with lidocaine 10%. Throughout the procedure the fetal heart was continuously monitored using a cardiotocograph. After successful ATI:FB, general anaesthesia was induced. A healthy baby was delivered by caesarean section, and the patient's trachea was extubated once she was fully awake. Her postoperative recovery was uneventful, and she was discharged from the hospital the next day.

Discussion

There are several case reports of the management parturients with VACTERL association, but our case was also complicated by severe cervical spine stenosis. Ramos et al described one such case of a patient with VACTERL association and severe lumbar scoliosis: the patient had an epidural for labour analgesia and an uneventful vaginal delivery [2]. The authors did not state if MRI of the spine was performed. Therefore, we do not know if their patient also had a spinal stenosis, as in our case.

There was a higher risk of complications from neuraxial anaesthesia in our case for several reasons: There was a risk of inadvertent CSF drainage after a spinal anaesthetic or accidental dural puncture during epidural placement, which could lead to CSF pressure changes and rapidly progressive myelopathy. Hara et al, reported two such cases wherein a low CSF pressure related to a post‐surgical drainage of CSF lead to progressive myelopathy with hyperreflexia of upper limb and hyperalgesia [3]. The presence of a spinal mass or any pathologic lesion that compresses the spinal cord or thecal sac may impair CSF flow. Loss of CSF below the spinal stenosis exacerbates pressure differences between the CSF spaces above and below the lesion, which can cause herniation of parenchymal structures. The term ‘spinal coning’ was coined by Krishnan et al, who described another case of paraplegia in a patient with neurofibroma after lumbar puncture [4]. In that case, the patient developed weakness of bilateral limb and loss of bladder function. The authors postulated that coning occurs due to the relative movement of spinal cord structures due to sudden changes in the pressure gradient above and below the stenosis. Hollis et al, found in a retrospective case analysis that in patients with complete spinal stenosis, a lumbar puncture led to neurological deterioration in seven out of the 50 cases (14%) [5]. To our knowledge, there are no similar studies in the obstetric population, however in our view, it is unlikely to be lower and therefore this level of risk is quite significant.

In chronic spinal stenosis, the narrow cross‐sectional area increases the risk of nerve compression or local anaesthetic neurotoxicity [6, 7, 8]. Neal et al noted that not just incidence but the severity of injury in these cases might be higher than general population [9]. Finally, the neuraxial blockade is known to be unpredictable in patients with kyphosis or complex anatomical abnormalities of the spine. Kavanagh et al describe a case of Klippel Feil syndrome with a fused cervical spine [10], noting an unpredictable spread of spinal anaesthesia despite using a combined spinal epidural (CSE), ultimately requiring conversion to general anaesthesia. In another case, Hilton et al, described a CSE and general anaesthesia for caesarean section in a parturient with VACTERL association, severe thoracic scoliosis and restrictive lung disease. The patient received a CSE for labour analgesia, but the authors decided against extending the block for caesarean section, due to her severe restrictive lung disease and unpredictable nature of epidural top ups in patients with complex anatomical abnormalities of spine [11].

Although these risks are rare, the complications could be catastrophic. When we discussed this with our patient as part of our detailed decision‐making process, our patient decided that although the incidence is rare, the risk was still unacceptable for her. We agreed that the best course of action would be awake intubation followed by general anaesthesia.

As mentioned earlier, our case was also complicated by severe pre‐eclampsia. We avoided using co‐phenylcaine (lidocaine 5% with phenylephrine 0.5%) for decongesting the nasal mucosa for fear of increasing blood pressure. We instead used 0.1% xylometazoline spray and a separate 10% lidocaine spray. Awake tracheal intubation allowed us to reduce the risk of spinal cord damage due to neck manipulation during laryngoscopy and avoid the airway‐related complications in an obvious difficult airway.

Our case highlights the importance of spinal MRI in patients with known congenital anatomical abnormalities of spine or associated syndromes. Whole spine MRI in patients with VACTERL association assists in ruling out cord tethering, cervicothoracic scoliosis or spinal stenosis. These findings have obvious implications both for airway management and neuraxial anaesthesia.

Our case report highlights the importance of multidisciplinary discussion, an individualised approach and shared decision‐making in managing pregnant patients at high risk for perioperative morbidity due to severe congenital anatomical abnormalities.

Acknowledgements

Published with the written consent of the patient. No external funding and no competing interests declared.

References

- 1. Solomon BD. Vacterl/Vater association. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2011; 6: 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ramos JA, Shettar SS, James CF. Neuraxial analgesia in a parturient with the VACTERL association undergoing labor and vaginal delivery. Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology 2018; 68: 205–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hara T, Nakajima M, Sugano H, Karagiozov K, Miyajima M, Arai H. Cerebrospinal fluid over‐drainage associated with upper cervical myelopathy: successful treatment using a gravitational add‐on valve in two cases. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery 2020; 19: 100586. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krishnan P, Roychowdhury S. Spinal coning after lumbar puncture in a patient with undiagnosed giant cervical neurofibroma. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 2013; 16: 440–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hollis PH, Malis LI, Zappulla RA. Neurological deterioration after lumbar puncture below complete spinal subarachnoid block. Journal of Neurosurgery 1986; 64: 253–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hebl JR, Horlocker TT, Kopp SL, Schroeder DR. Neuraxial blockade in patients with preexisting spinal stenosis, lumbar disk disease, or prior spine surgery: efficacy and neurologic complications. Anesthesia and Analgesia 2010; 111: 1511–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hewson DW, Bedforth NM, Hardman JG. Spinal cord injury arising in anaesthesia practice. Anaesthesia 2018; 73: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stevens E, Williams B, Kock N, Kitching M, Simpson MP. Cord injury after spinal anaesthesia in a patient with previously undiagnosed Klippel‐Feil syndrome. Anaesthesia Reports 2019; 11: 7–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neal JM, Barrington MJ, Brull R, et al. The second ASRA practice advisory on neurologic complications associated with regional anesthesia and pain medicine: executive summary 2015. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine 2015; 40: 401–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kavanagh T, Jee R, Kilpatrick N, Douglas J. Elective cesarean delivery in a parturient with Klippel‐Feil syndrome. International Journal Obstetric Anesthesia 2013; 22: 343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hilton G, Mihm F, Butwick A. Anesthetic management of a parturient with VACTERL association undergoing cesarean delivery. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia 2013; 60: 570–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]