Abstract

Objective:

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) frequently functions to regulate shame-based emotions and cognitions in the context of interpersonal stress. The present study sought to examine how sleep quality (SQ) may influence this process in a laboratory setting.

Methods:

Participants included 72 adults (Mage = 24.28; 36 with a lifetime history of NSSI) who completed a self-report measure of prior month SQ and engaged in a modified Trier Social Stress Task (TSST). State shame ratings were collected immediately prior to and following the TSST, as well as 5 minutes post-TSST, to allow for the measurement of shame reactivity and recovery.

Results:

No significant results emerged for NSSI history and SQ as statistical predictors of shame reactivity. However, NSSI history was significantly associated with heightened shame intensity during the recovery period of the task, and this was moderated by SQ. Simple slopes analyses revealed a conditional effect whereby poorer SQ (1 SD above the mean) was associated with greater intensity of shame during recovery, but only for those with a history of NSSI.

Conclusion:

Poor SQ may contribute to worrisome emotional responses to daytime stressors in those at risk for NSSI.

Keywords: Non-suicidal self-injury, self-harm, shame, emotion regulation, sleep, insomnia

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) can be defined as deliberate self-damage of one’s body tissue that is not socially sanctioned and in the absence of intent to die as a result (Klonksy, 2007). NSSI appears to be a transdiagnostic phenomenon, affecting individuals with mood and anxiety disorders, trauma-related disorders, obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders, and personality disorders (Bentley et al., 2015; Liu, 2021; Nock et al., 2006). Lifetime prevalence is currently estimated to be between 4% and 6%, with the highest rates among younger people (Klonksy, 2009; Liu, 2021). NSSI causes considerable distress and impairment, and is a robust predictor of a range of maladaptive outcomes, including suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Selby et al., 2015; Klonsky, May, & Glenn, 2013). Hence, better understanding of the factors that confer risk for NSSI is a significant public health concern.

Sleep disturbance is an understudied but potentially important risk factor for NSSI. One recent study with a large sample (N = 10,220) compared adolescents with sleep problems to those without sleep problems, and found that those with sleep problems (e.g., short sleep duration, sleep fragmentation, etc.) were significantly more likely to report incidents of NSSI (Hysing et al., 2015). Poor sleep in adolescence also appears to be a risk factor for NSSI in adulthood, as demonstrated by a longitudinal study that found that adolescents who displayed shorter sleep duration were at increased risk to report NSSI as adults 12 years later (Junker et al., 2014). The association between sleep and NSSI also appears to persist in adulthood. Ennis et al. (2017) found that higher incidence rates of NSSI were associated with greater symptoms of insomnia in adults with psychiatric disorders, and this finding has been corroborated by other studies examining aspects of sleep functioning and NSSI in adult samples (Khazaie et al., 2021). Hence, it is clear that sleep problems is reliably associated with NSSI. Yet, despite the linkage, it is not entirely clear how sleep disturbance influences NSSI.

Sleep has an important impact on next day emotion generation and capacity to regulate emotions. Emotion generation (i.e., reactivity) refers to the dynamic process by which one attends to and appraises environmental stimuli, which results in a rapid subjective and physiological response. Strategies to modulate or change emotional responses can broadly be referred to as emotion regulation. Emotion dysregulation occurs when there is persistent failure to implement these strategies, resulting in greater frequency, intensity, and delayed recovery (i.e., poor habituation) of aversive emotions (Gross & Jazaieri, 2014; Neacsiu et al., 2014). Several studies have demonstrated the role of sleep in daytime emotional generation and regulation, as well as the extent to which poor sleep contributes to daytime emotion dysregulation (see Fairholme et al., 2015; Kahn et al., 2013). Laboratory studies suggest that just a few nights of sleep disruption predict next day increase in negative affect and decrease in positive affect (Paterson et al., 2011; Talbot et al., 2010), and greater behavioral impulsivity in response to emotionally evocative stimuli (Anderson & Platten, 2011). Poor sleep is also associated with diminished connectivity between brain structures responsible for emotional control (Yoo et al., 2007), which indicates a negative influence on daytime capacity to regulate emotions. Moreover, according to a recent longitudinal study, poor sleep precedes daytime maladaptive cognitions associated with delayed recovery of aversive emotions, such as rumination (Mazzer et al., 2019).

The influence of sleep on emotional functioning is particularly relevant to NSSI, as NSSI frequently functions as a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy (Klonsky, 2007; Nock, 2009), especially in the context of shame. Indeed, recent research suggests that NSSI behaviors in part function as both a way to regulate the experience of shame specifically, as well as self-punishment in response to shame-based cognitions and affect (Mahtani, Melvin, & Hasking, 2018). Shame propensity has been directly linked with NSSI, independent of depression and anxiety (VanDerhei et al., 2014). Moreover, shame and related constructs (e.g. self-criticism) appears to differentiate individuals who actively engage in NSSI from those who recently stopped engaging in NSSI (Hack & Martin, 2018), as well as from individuals who engage in other self-damaging behaviors, such as substance abuse (St. Germain & Hooley, 2012). Similarly, in a daily diary study, it was determined that daily levels of self-dissatisfaction were significantly and consistently higher among those engaging in NSSI relative to those without such a history (Victor & Klonksy, 2014). Shame-related constructs are also associated with pain tolerance (Hooley et al., 2010) and willingness to endure pain (Hooley et al., 2014), and pain tolerance and endurance is highly related to NSSI (see Kirtley et al., 2016). Given the degree to which sleep is associated with daytime emotion generation and regulation, it is conceivable that poor sleep renders someone with NSSI tendencies more vulnerable to experiencing shame dysregulation (i.e., heightened reactivity and delayed recovery of shame) in stressful contexts, which could have implications for risk of future NSSI behaviors. However, to our knowledge, this line of inquiry has yet to be empirically explored.

The Present Study

To address this relative gap in literature, the present study involved a secondary analysis of data from a recently concluded study, and with a sample comprised of individuals with and without a lifetime history of NSSI. More specifically, in this sample, we used a laboratory paradigm to examine if sleep quality (SQ) influences the extent to which NSSI history is associated with shame responses. To do this, participants completed a self-report measure of prior month SQ, and then subsequently underwent an evaluative stress task similar to the Trier Social Stress Task (TSST), a widely used standardized laboratory stress task that reliably elicits shame and other self-conscious emotions (Frisch et al., 2015; Kirschbaum et al., 1993). To measure shame response to the task, participants completed state measures of self-conscious emotions immediately prior to (i.e., baseline shame) and after the task, as well as 5 minutes post-task. ‘Shame response’ refers to reactivity (i.e., initial shame reaction calculated by subtracting baseline shame ratings from shame ratings immediately post-stressor) and recovery (i.e., regulation of shame calculated by subtracting baseline shame ratings from shame ratings made five minutes post-stressor), where greater levels of one or both indicates excessive overall shame response. It was hypothesized that lifetime NSSI history would be associated with excessive shame responses to the task, and that this would be moderated by SQ. More specifically, we expected that poorer SQ would relate to especially heightened shame reactivity and delayed recovery of shame in those who report a lifetime history of NSSI.

Method

Participants

Participants included 72 adults (66% female), 36 of whom reported a lifetime history of NSSI. Lifetime history of NSSI was defined as a report of any instance of NSSI over the course of one’s life. Within the NSSI group, 23 participants (or 64% of the group) reported at least one instance of NSSI in the past year. Given recent studies indicating that number of lifetime NSSI events is indicator of NSSI severity, we examined the proportion of participants who reported at least 10 lifetime instances of NSSI (e.g., Ammerman et al., 2020). In our NSSI group, 20 participants (or 55% of the group) reported at least 10 instances of NSSI episodes in their lifetime. Because the sizes of the these NSSI subgroups are relatively small, analyses conducted and reported below only include the larger lifetime NSSI history group. For comparisons between the NSSI group and non-NSSI group on demographic, psychiatric, sleep components, and other relevant variables, see Table 1. To obtain a representative sample, participants were recruited across an array of settings. They were recruited from clinical settings, such as inpatient and outpatient mental health facilities. Recruitment efforts in the community included posting advertisements and flyers in community venues with high traffic, such as bus stations and coffee shops. We also recruited from eligible individuals from the undergraduate psychology pool at a university in the southwestern region of the United States. Across both groups, the racial/ethnic breakdown was 78% white/Caucasian, 9% Asian-American, 3% black/African-American, 2% Latinx, 1% Pacific Islander, and 7% either declined to answer or identified as multiracial. We intentionally recruited people between the ages of 18 and 45 with history of self-injurious thoughts (including suicidal and non-suicidal thoughts), as well as those without such a history. Those who reported conditions that could complicate data interpretation or lead to difficulty in study compliance were excluded, such as those with schizophrenia spectrum/psychotic disorders, ongoing mania, and certain developmental disabilities.

Table 1.

Comparison of groups by NSSI history on demographics and relevant study variables.

| NSSI Hx (n = 36) |

No NSSI Hx (n = 42) |

Comparison | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M (SD) | M (SD) | Chi square/t-test | Phi /Hedges g |

| Age | 24.02 (5.23) | 24.50 (7.52) | −.32 | .07 |

| Gender | 70% female | 60% female | 4.03 | .23 |

| Global SQ | 10.47 (3.72) | 8.19 (3.12) | 2.94** | .66 |

| Subjective SQ | 1.69 (.58) | 1.33 (.61) | 2.67** | .60 |

| Sleep Latency | 1.97 (.94) | 1.50 (1.06) | 2.08* | .46 |

| Sleep Duration | 1.05 (.92) | 1.09 (.88) | .19 | .04 |

| Sleep Efficiency | 1.31 (1.24) | 1.00 (1.12) | 1.13 | .25 |

| Sleep Disturbance | 1.44 (.65) | 1.24 (.48) | 1.16 | .36 |

| Sleep Medication | 1.31 (1.31) | .66 (1.09) | 2.35* | .52 |

| Daytime Impairment | 1.69 (.74) | 1.36 (.73) | 2.01* | .45 |

| Shame at baseline | 14.77 (4.29) | 13.09 (5.07) | 1.55 | .36 |

| Shame initial post-task | 25.55 (9.21) | 20.66 (8.77) | 2.40* | .35 |

| Shame during recovery | 21.47 (9.36) | 16.21 (7.44) | 2.74** | .54 |

| Internalizing Psychopathology | 119.22 (39.88) | 85.64 (27.16) | 4.39*** | .62 |

| Depression | 35.50 (11.63) | 23.42 (10.24) | 4.87*** | 1.09 |

| Anxiety | 22.31 (9.95) | 16.26 (6.52) | 3.21** | .72 |

| OCD | 25.69 (8.51) | 19.21 (6.49) | 3.80*** | .86 |

| Phobia | 12.42 (5.84) | 8.90 (2.70) | 3.49*** | .84 |

| Somatization | 23.31 (8.05) | 17.83 (4.63) | 3.74*** | .86 |

Note. Hx = history;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Materials

Sleep Quality.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse et al., 1989) was used to measure SQ. The PSQI is widely used as a self-report indicator of one’s overall sleep quality over the past month (i.e., global SQ). The PSQI includes subscales that correspond to validated markers of sleep functioning, including sleep duration, sleep disturbance, habitual sleep efficiency, subjective sleep quality, daytime dysfunction, and use of sleep medication. A global score is calculated by summing up scores on all subscales. Higher scores on the PSQI indicate poorer global SQ. Items include both Likert scale and numeric entry items, each corresponding to one of the seven components of SQ to be tallied. The PSQI has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Beck et al., 2004) and has been validated against objective markers of sleep functioning as well as other commonly used self-report measures of sleep (Buysse et al., 2008). Internal consistency for the PSQI in the present study was adequate (α = .62).

Self-conscious emotions.

To assess state self-conscious emotions, a 10-item scale was used similar to the one used by Dickerson et al. (2008). In this scale, one item from the PANAS (“ashamed”) was included, as well additional shame-related descriptors (e.g., “embarrassed,” “humiliated”). The scale also includes six items meant to assess self-conscious cognitions (i.e., terms used to describe the experience of shame), such as “foolish,” “exposed,” and “defeated.” Participants rated how they currently felt on each of the 10 items on this measure using a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (Very much so). Higher scores on this measure indicate higher intensity of felt shame in the moment. This scale has demonstrated good internal consistency (e.g., Grove et al., 2017). In the present study, internal consistency for this scale for each of the three times it was completed was good to excellent (α = .88, .95, and .96).

Internalizing psychopathology.

To assess for internalizing psychopathology, participants completed the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90R; Derogatis, 1983), a 90-item self-report survey assessing for a broad range of psychological problems. The measure yields scores for nine domains of psychopathology to be combined for overall global score of “distress.” However, research suggests a bifactor structure may be a better model fit (Urbán et al., 2014; Preti et al., 2019), one of which is a factor of internalizing psychopathology comprised of the following symptom domains: depression, anxiety, somatization, phobia, and OCD. This domain score of internalizing psychopathology was used in the present study. Items inquire about symptoms experienced over the past week (e.g., “How much were you bothered by feeling easily annoyed or irritated?”), using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely). The SCL-90R displays good psychometric properties (Akhavan et al., 2020), and internal consistency for the internalizing factor of this scale for the present study was excellent (α = .97).

Lifetime NSSI history.

The present study used select questions from the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Inventory (SITBI; Nock et al., 2007). Examining NSSI history in this manner, including as a single item measure, has been done extensively in prior literature (see Robinson & Wilson, 2020). Participants were asked if they “ever actually purposely hurt [themselves] without wanting to die.” Participants were also asked to estimate how many times (numeric entry) in their lifetime they had an episode of hurting themselves without wanting to die. Although the present study did not use the full version, the SITBI is generally a widely used interview to assess for suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviors, and has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Nock et al., 2007).

Procedure

Orientation and assessment (Lab Visit #1).

The current research is derived from secondary analysis of a larger study focusing on self-injurious thoughts and behaviors and sleep functioning. Individuals who successfully screened into the study presented to the research laboratory for two separate visits. At the first visit, participants were first consented before completing the self-report measures on the computer, such as the PSQI and SCL-90. They then completed select sections of the SITBI with a research associate. Approximately 85% of the interviews were administered by the first author, who is highly trained to administer, score, and interpret responses. The remaining interviews were administered by an intensively trained post-baccalaureate research assistant. Approximately 15% of the interviews were administered jointly by both researchers to ensure concordance of interpretation and scoring.

Laboratory stress task (Lab Visit #2).

Participants were asked to return to the research lab to complete the rest of the study procedures approximately three days later. All participants were guided through the entire task by a research assistant not affiliated with the stressor. To minimize potential influences on reactions to the laboratory task, the research assistant who completed the participant’s orientation session was not present for the second laboratory visit.

Participants completed a modified Trier Social Stress Task (TSST; Smith & Jordan, 2015) in an experimental chamber with two-way mirrors allowing for experimenter observation. Prior to the task, participants completed a vanilla baseline task, during which they spent 10 minutes rating various nature pictures. This is a standard approach to ensure that participants are at a relatively neutral level of emotional intensity prior to the stressor (Jennings et al., 1992). Once the baseline was completed, participants were asked to complete the self-conscious emotions rating scale on a laptop computer within the experimental chamber. Once the participant was finished, the lead researcher entered the experimental chamber to orient the participant to the upcoming task. Here, the lead researcher told the participant that they would soon be completing a series of tasks in front of two additional researchers (i.e., confederates) waiting just outside the chamber. Participants were told that the two researchers would observe them and use their performance to rate them on likeability and competence. The lead researcher then exited the chamber and the two confederates entered and sat directly in front of the participant. The confederates were trained to not verbally engage with the participant and to display a blank, neutral face at all times. After each task, the confederates would mark a number on a piece of paper attached to a clipboard to appear as if they were in fact rating the participant.

Once the confederates were situated in the experimental chamber, participants were guided through each of the subsequent tasks by pre-recorded audio instructions. The participants completed two tasks. The first task was designed as a role play, where the participant was asked to imagine that they had collided with another driver in a minor car accident. The other driver was a pre-recorded audio recording who was particularly hostile and antagonistic towards the participant. The task was designed such that the audio recorded driver spoke for 90 seconds while the participant sat and listened, and then the participant was given 90 seconds to respond. The audio recorded driver spoke for one last 90-second segment, to which the participant was then asked to respond for another 90 seconds. After each of the participant’s responses, the confederates made “ratings” on their rating sheet.

Participants then immediately began the second and final task, which involved mental arithmetic. Participants were told to count backwards from 2,142 by 7 as fast as they could without making a mistake. If a mistake was made, participants had to start back at the beginning. Participants were told that they had an undisclosed amount of time to finish before being told to stop. Participants were told that the “vast majority of participants” were able count all the way back to 0 before time expired and with minimal errors in the process. This was meant to prompt the participant to compare themselves with others and, inevitably fail to meet the normative standards. Each time the participant answered incorrectly, the confederates made a tally on their rating sheet. No participants were able to finish successfully. Once they were stopped by confederates, the confederates promptly left the chamber and the lead researcher immediately returned to have the participant complete the same self-conscious emotions scale they completed previously to indicate how they were feeling in that very moment. After 5 minutes sitting alone in the experimental chamber, the participant was asked to complete the same self-conscious emotion scale again to indicate how they felt in that very moment. Once finished, the participant was debriefed and compensated for their time.

Analytic Plan

Shame reactivity was calculated by subtracting each participant’s pre-task shame ratings from ratings made immediately post-task. Shame recovery was calculated by subtracting pre-task shame ratings from ratings made 5 minutes post-task. NSSI history is coded as 1= history of NSSI and 0 = no history of NSSI.

Zero order correlational analyses were first conducted to provide initial examination of hypothesized associations. To examine the potential moderating role of SQ on the link between NSSI history and shame response, two separate bias-corrected percentile bootstrap analyses were conducted using the SPSS PROCESS Macro (Hayes, 2018), a widely used tool to test a variety of moderator and mediator models. Effects were considered significant if the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (BCI) did not include 0. The first model included shame reactivity (first post-task scores minus pre-task score) as the dependent variable, with NSSI history as the independent variable and global SQ as the moderating variable. The second model included shame recovery (final post-task scores minus pre-task score) as the dependent variable. Given the extent that many forms of internalizing psychopathology (e.g., anxiety, depression, etc.) relate to sleep issues, NSSI, and problematic emotional responses to stressors (Fairholme et al., 2013; Liu, 2020), the internalizing domain from the SCL-90 was included as a covariate in both models to determine if the effects were independent of co-occurring psychopathology.

Results

Manipulation Check on Shame Induction

Means and standard deviations for scores on shame at baseline, immediately post-task and the during recovery are found in Table 1. Across all participants, paired sample t-tests revealed that shame intensity significantly increased from baseline to initial post-task scores (t[71] = 8.76, p < .001). During the recovery period, shame scores remained significantly higher relative to baseline ratings of shame (t[71] = 5.14, p < .001). Altogether, this suggests that the laboratory stress task was successful at eliciting a modest shame response among participants.

Descriptives and Correlations Between Study Variables

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations are depicted in Table 2. NSSI history was significantly correlated with global SQ, such that history of NSSI related to poorer SQ (higher scores on the PSQI indicate poorer sleep quality; r = .32, p = .004). There was no significant correlation between NSSI history and shame reactivity (r = .18, p = .11), but there was a significant correlation with shame recovery indicating that those with NSSI history were more likely to display longer delayed recovery of shame following the laboratory stress task (r = .23, p = .04). Similarly, SQ was not significantly correlated with shame reactivity (r = .16, p = .16), but significantly and positively associated with shame recovery (r = .26, p = .02).

Table 2.

Descriptives and correlation matrix between all relevant study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NSSI History | - | |||||||||||

| 2. Subjective SQ | .29** | - | ||||||||||

| 3. Sleep latency | .23* | .57*** | - | |||||||||

| 4. Sleep duration | −.02 | .54*** | .29** | - | ||||||||

| 5. Sleep efficiency | .13 | −.08 | .23* | −.27* | - | |||||||

| 6. Sleep disturbance | .18 | .51*** | .32** | .33** | .08 | - | ||||||

| 7. Medication | .26* | .38*** | .23* | .10 | .06 | .31** | - | |||||

| 8. Daytime impairment | .23* | .48*** | .27* | .21 | −.09 | .38*** | .22 | - | ||||

| 9. Global SQ | .32** | .76*** | .72*** | .37*** | .35** | .64*** | .62*** | .56*** | - | |||

| 10. Internalizing symptoms | .45*** | .35** | .32** | .05 | .11 | .38*** | .26* | .49*** | .46*** | - | ||

| 11. Shame reactivity | .18 | .18 | .11 | .09 | .08 | .25* | .05 | −.02 | .16 | .22 | - | |

| 12. Shame recovery | .23* | .25* | .26* | .14 | .09 | .24* | .08 | .09 | .26* | .27* | .84*** | - |

| Mean (SD) | - | 1.50 (.61) | 1.72 (1.03) | 1.08 (.89) | 1.14 (1.18) | 1.83 (.57) | .96 (1.23) | 1.51 (.75) | 9.24 (3.58) | 101.14 (27.41) | 9.08 (9.09) | 4.80 (8.14) |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Bootstrapping Analyses Testing SQ as Moderator for the effect of NSSI on Shame

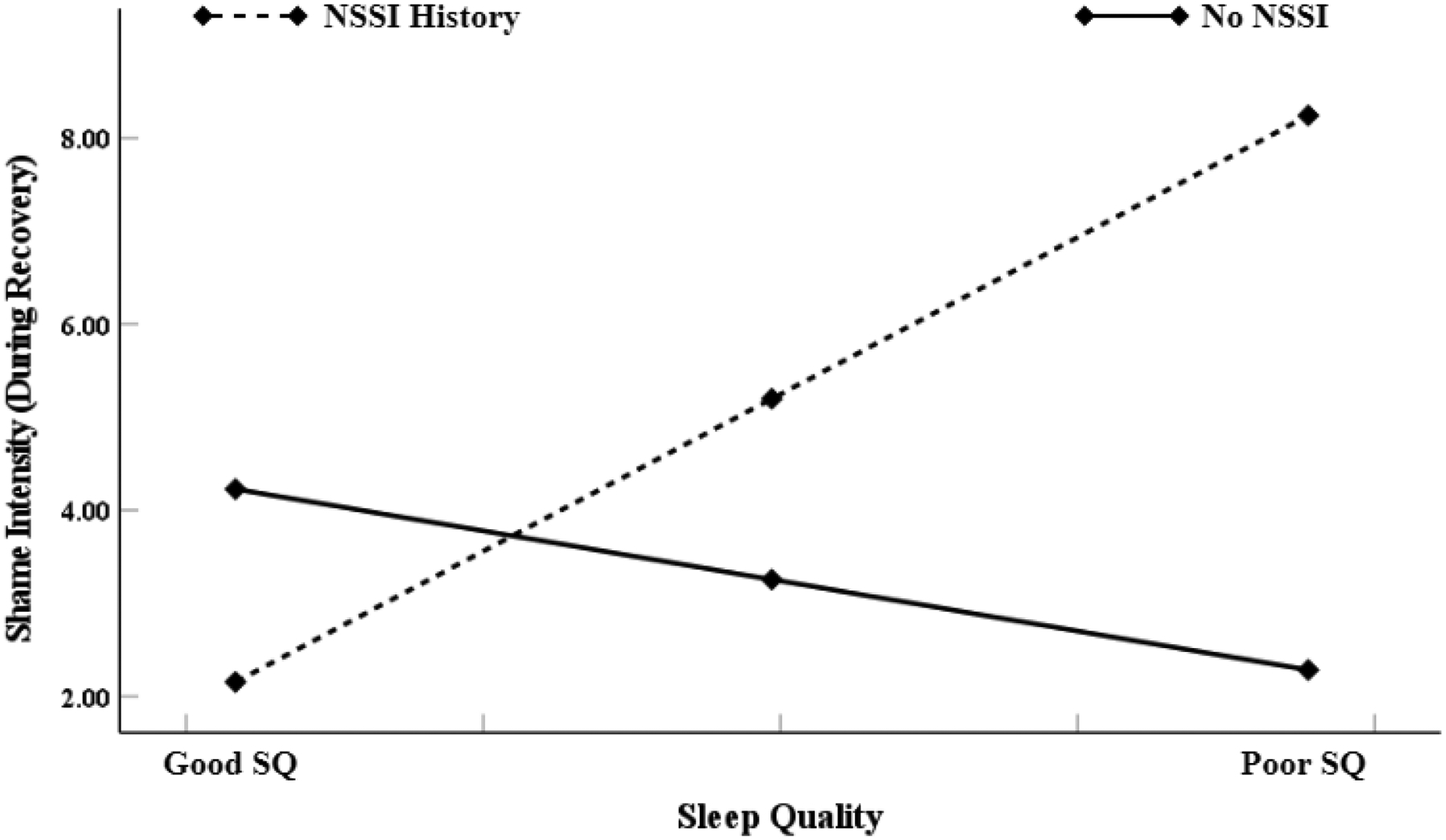

Table 3 presents the results of both models. For the first model (shame reactivity as the dependent variable), there was no significant effect for NSSI (B = 1.76, p = .44) or SQ (B = −.35, p = .44). There was also no significant effect for the NSSI × SQ (B = .95, p = .12). These results overall suggest that neither NSSI nor SQ had any significant impact on shame reactivity to the laboratory task. With respect to the second model (shame recovery as the dependent variable), there were no significant main effects for NSSI (B = 2.01, p = .32) or SQ (B = −.27, p = .51). However, there was a significant effect for NSSI × SQ (B = 1.11, p = .03). To clarify the interaction effect, a simple slope test was conducted to examine the relation between NSSI and shame recovery at low and high levels of SQ (as indicated by the total score of PSQI). As a reminder, higher scores on the PSQI are indicative of poorer SQ, whereas lower scores on the PSQI are indicative a better SQ. As such, for the purposes of the present research, healthier levels of SQ translates to 1 SD below the mean score, whereas poorer SQ translates to 1 SD above the mean score. Simple slope tests revealed no significant effect for NSSI on shame recovery when PSQI scores were at the mean (Bsimple = 1.94, t = .97, p = .33) or 1 SD below the mean (Bsimple = −2.07, t = −.76, p = .45). However, there was a significant effect for NSSI on shame recovery when PSQI score was 1 SD above the mean (Bsimple = 5.95, t = 2.14, p = .03). A deeper inspection of these results reveal that this effect only occurs in the NSSI group. That is, poorer sleep results in significantly greater delayed recovery of shame response but only for those with a history of NSSI (see Figure 1). Additionally, when examining the effect of SQ on shame recovery at different levels of NSSI history, there was a significant association between SQ and shame recovery for the NSSI group (Bsimple = .84, t = 2.30, p = .02,), but no significant effect emerged for the non-NSSI group (Bsimple = −.27, t = −.66, p = .51). The significant effects demonstrated above were significant independent of co-occurring internalizing symptoms.

Table 3.

Moderating effect of SQ on the relation between NSSI history and shame response

| b | BootLLCI | BootULCI | t | p | R 2 | F Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (DV: Shame Reactivity) | |||||||

| Predictors | .09 | 1.84 | |||||

| NSSI History | 1.76 | −2.85 | 6.37 | .76 | .45 | ||

| Global SQ | −.35 | −1.26 | .56 | −.77 | .44 | ||

| Internalizing Symptoms | .03 | −.03 | 1.00 | 1.05 | .30 | ||

| NSSI × SQ | .95 | −.26 | 2.152 | 1.59 | .12 | ||

| Model 2 (DV: Shame Recovery) | |||||||

| Predictors | .16 | 3.36* | |||||

| NSSI History | 2.01 | −1.99 | 5.99 | 1.00 | .32 | ||

| Global SQ | −.27 | −1.07 | .54 | −.67 | .51 | ||

| Internalizing Symptoms | .03 | −.03 | .08 | 1.07 | .29 | ||

| NSSI × SQ | 1.11 | .07 | 2.15 | 2.13 | .03 |

Note.

p < .05;

significant effect in bold for ease of interpretation.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the moderating role of SQ in the association between NSSI history and shame recovery (i.e., shame intensity during the recovery phase of the stress task). The moderating effect is graphed for two levels of SQ: (1) good SQ (1 SD below the mean of PSQI total score) and (2) poor SQ (1 SD above the mean of PSQI total score). Higher total score of PSQI indicates poorer SQ.

In alternative models without internalizing symptoms included as a covariate, the results were similar. That is, a model with shame reactivity as the dependent variable yielded insignificant results, F(1,72) = 2.09, R2 = .08, p = .11. When shame recovery was the dependent variable, the overall model was significant, F(1,72) = 4.09, R2 = .15, p = .009. There were no significant main effects for NSSI (B = 2.76, [BCI = −.97, 6.49], t = 1.47, p = .14) or SQ (B = −.15, [BCI = −.93, .62], t = −.40, p = .68), but there was a significant effect for NSSI × SQ (B = 1.12, [BCI = .07, 2.15], t = 2.14, p = .03). Simple slopes analyses showed a similar conditional effect, such that there was only a significant effect for NSSI on shame recovery when PSQI score was 1 SD above the mean (Bsimple = 6.75, t = 2.52, p = .01). Moreover, when examining the effect of SQ on shame recovery at different levels of NSSI history, SQ was significantly associated with shame recovery but only in the NSSI group (Bsimple = .96, t = 2.75, p = .007).

Discussion

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a transdiagnostic phenomenon associated with a host of serious outcomes, including suicide (Klonsky et al., 2013). Recent research suggests an association between sleep problems and NSSI behavior, such that poorer sleep across various domains of sleep functioning confers greater risk for NSSI (see Khazaie et al., 2021). However, the reasons for this relationship are unclear. People who engage in NSSI tend to also experience emotion dysregulation, especially shame (Mahtani et al., 2018; VanDerHei et al., 2014). In healthy individuals, there is a bidirectional association between emotion dysregulation and sleep (Kahn et al., 2013), particularly in the context of stressful events (Van Laethem et al., 2015). Hence, among those with NSSI tendencies, poor sleep may be especially influential in the degree to which stressful events contribute to emotion dysregulation (e.g., shame) and NSSI. As such, the purpose of the present study was to examine shame response to a widely used laboratory stress paradigm among those with and without a lifetime history of NSSI, and test self-report sleep quality (SQ) as a potential moderator for this association. It was hypothesized that NSSI history would be associated with greater shame reactivity (i.e., initial shame response to the stressor) and greater delay in recovery from initial shame response (i.e., slower return to emotional baseline), and that this effect would be especially heightened in the context of poor SQ.

Results revealed partial support for our hypotheses. That is, with respect to shame reactivity, no significant main effects emerged for NSSI or SQ. Further, there was no interactive effect for SQ on the relation between NSSI and shame reactivity. With respect to shame recovery, no significant main effects emerged for either NSSI or SQ. However, consistent with our hypotheses, SQ significantly moderated the association between NSSI and shame recovery, above and beyond ongoing internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, etc.). More specifically, simple slopes analyses revealed a conditional effect, whereby SQ was associated with greater delayed recovery of shame but only when PSQI scores were 1 SD above the mean (indicating poorer sleep) and only for the NSSI group. In other words, SQ appears to only pose risk for delayed recovery of shame response to a stressful event when sleep is particularly poor and if the individual has a history of NSSI. Hence, findings suggest that poor SQ could be a factor contributing to a worrisome stress response (i.e., delayed shame recovery) among those at risk for NSSI.

The fact that SQ moderated the effect of NSSI on shame recovery but not reactivity suggests the potential role of maladaptive cognitions associated with delayed recovery of emotions, especially rumination. This is further bolstered by the fact that in our sample, shame recovery (but not reactivity) was significantly correlated with sleep onset latency, a facet of sleep problems often characterized by rumination (see Clancy et al., 2020). Rumination involves dwelling or perseverating on a situation that induces aversive emotions, which intensifies and perpetuates rather than attenuates the emotional response (Selby & Joiner, 2009). Although data on rumination was not directly collected, it is certainly feasible that this process was demonstrated in the present study, given that shame recovery was measured after participants were asked to sit alone in the experimental chamber post-stressor for five minutes with minimal stimuli to distract. Prior work has shown rumination as a key factor associated with shame responses to a stressful task (e.g., Cândea & Szentágotai-Tătar, 2017). Perhaps more importantly, rumination is particularly relevant to both NSSI and sleep problems. Several longitudinal studies have demonstrated that rumination interacts with negative affect to predict future NSSI behavior (Nicolai, Wielgus, & Mezulis, 2006; Selby et al., 2013). Moreover, rumination is a form of pre-sleep cognitive arousal that underlies the link between daytime stress exposure and subsequent sleep disturbance (Li et al., 2019; Tousignant et al., 2019), and poor SQ in turn is predictive of next day rumination (Cox et al., 2018; Kalmbach et al., 2019). Additional research that directly measures rumination is necessary to fully determine the extent to which the moderating role of poor SQ on delayed recovery of shame in the NSSI population is explained by these kinds of cognitive-affective processes.

There are also interpersonal factors that could explain the present study’s findings. As mentioned above, the laboratory social stressor used in the present study reliably prompts participants to engage in negative self-evaluation, negative normative comparisons of self to others, and to perceive rejection by others. In real life, these kinds of experiences can confer risk for NSSI among those with a history of such behavior. For example, among adolescents with NSSI tendencies, negative peer and parental dynamics are highly predictive of future NSSI behavior (Esposito et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020). Studies involving retrospective reporting of interpersonal stressors suggest that conflict and arguments, as well as perceived rejection and criticism, are among the most common stressors associated with NSSI behaviors in adolescents (Nock et al., 2009) and adults (Turner et al., 2016). This was recently supported by a prospective EMA study involving 62 young adult women, which revealed that interpersonal stressors, such as rejection and criticism, were predictive of within-person increases in NSSI urges, and that this effect was mediated by internalizing negative affect (Victor et al., 2019). Importantly, these kinds of interpersonal stressors have also been shown to disrupt sleep at night (Gunn et al., 2014; Jian & Poon, 2021), and poor sleep has been shown to heighten next day vulnerability to adverse reactions to interpersonal conflict and perceived rejection in healthy populations (Gilbert et al., 2015; Gordon et al., 2014). Hence, although less research on this topic has been conducted on NSSI populations, our findings may provide initial indications for how sleep difficulties in the context of interpersonal stress confer risk for NSSI behaviors in those with NSSI tendencies.

If the current findings are replicated, future research should explore the underlying mechanisms by which poor SQ impacts shame recovery among people with a history of NSSI. For example, although findings are somewhat mixed, in general, NSSI has been associated with self-report and behavioral markers of deficits in executive functioning linked with emotion regulation, including attentional control (Dahlgren et al., 2018), decision-making in stressful situations (Allen et al., 2019; Schatten et al., 2015), cognitive flexibility (Mozafari et al., 2022), and negative emotional response inhibition (Burke et al., 2021). Moreover, recent neuroimaging studies have demonstrated an association between NSSI history and disrupted connectivity between the amygdala and the pre-frontal cortex, indicating that NSSI is associated with diminished capacity to adaptively modulate emotional responses (Schreiner et al., 2017). Importantly, among healthy individuals, just one or several nights of sleep disturbance is associated with impairment in the abovementioned markers of executive functioning (e.g., Yoo et al., 2007). In other words, for those who engage in NSSI, shame regulation may be especially compromised in the context of poor sleep. This is just one of many potential mechanisms worth exploring that could be informative for understanding sleep-related risk for NSSI.

There were a number of limitations to the current study. First, the sample size of the present study was small and underpowered to detect small effect sizes (Shieh, 2009). As such, it is possible that a study with a larger sample size could have detected the hypothesized interaction effect for NSSI and SQ on shame reactivity, similar to the findings for shame recovery. Additionally, the current study examined individuals with a history of NSSI using a single assessment item, which essentially collapses into one group those who are currently engaging in NSSI and those who previously but no longer engage in NSSI. Although doing so is common practice and still yields important information, it also true that there are reported differences between those who currently engage in NSSI versus those who no longer engage in NSSI on indicators of emotion dysregulation (Hack & Martin, 2018; Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp, 2015). Further, using a single item to assess lifetime history of NSSI leaves out important information regarding the onset, duration, frequency, and severity of NSSI history. It should also be noted that the reported NSSI sample was less severe relative to some prior studies, and it is possible that a sample reporting more frequent past NSSI would yield different findings. We also relied on self-report, which may be especially limiting to our measure of sleep, as there have been documented discrepancies between subjective and objective sleep measures (Rezaie et al., 2018). The present research was cross-sectional, and the experimental study design may not translate to everyday life. Finally, the results of the current study do not necessarily indicate that poor SQ among those with a history of NSSI actually leads to future NSSI behavior. Future research should examine how nightly sleep contributes to emotion dysregulation and NSSI behaviors among those who actively and more severely engage in NSSI by using novel longitudinal methods (e.g., ecological momentary assessment), as such an approach could indicate specifically for whom, when, why, and under which contexts poor sleep contributes to subsequent increase in daytime shame response and related NSSI behaviors.

The above notwithstanding, this is the first known study that provides preliminary evidence for poor sleep as a risk factor for delayed shame recovery in individuals with a history of NSSI – a population for whom shame may be particularly problematic. If the findings of the present study are replicated and extended by future longitudinal and clinically oriented research studies, there are implications worth considering. For instance, targeting sleep problems as an adjunctive treatment to other therapies for NSSI could indirectly treat problematic emotional responses to stressors and, perhaps by extension, significantly minimize the frequency of NSSI behavior. Indeed, sleep interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, have been shown to indirectly reduce risk for other similar problems, such as suicidal ideation (Trockel et al., 2015). Monitoring sleep could provide a minimally invasive cue for impending increase in risk for delayed shame response and NSSI, allowing for the possibility of preventative measures. Finally, given the results of the current study, it possible that cognitive-affective factors (e.g., rumination) and contextual factors (e.g., interpersonal problems) could be key clinical targets to simultaneously reduce NSSI and sleep problems in those at risk for both of these outcomes.

Funding

This work was supported by grant 1F31MH108349-01A1 from NIH NIMH, which was awarded to Dr. Jeremy Grove.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

None of the authors report a conflict of interest. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or any of its academic affiliates.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

References

- Akhavan Abiri F, & Shairi MR (2020). Validity and reliability of symptom checklist-90-revised (SCL-90-R) and brief symptom inventory-53 (BSI-53). Clinical Psychology and Personality, 17, 169–195. [Google Scholar]

- Allen KJ, & Hooley JM (2019). Negative Emotional Action Termination (NEAT): Support for a cognitive mechanism underlying negative urgency in nonsuicidal self-injury. Behavior Therapy, 50, 924–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman BA, Jacobucci R, Turner BJ, Dixon-Gordon KL, & McCloskey MS (2020). Quantifying the importance of lifetime frequency versus number of methods in conceptualizing nonsuicidal self-injury severity. Psychology of Violence, 10, 442. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, & Platten CR (2011). Sleep deprivation lowers inhibition and enhances impulsivity to negative stimuli. Behavioural Brain Research, 217, 463–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Cassiello-Robbins CF, Vittorio L, Sauer-Zavala S, & Barlow DH (2015). The association between nonsuicidal self-injury and the emotional disorders: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 72–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck SL, Schwartz AL, Towsley G, Dudley W, & Barsevick A (2004). Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 27, 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke TA, Allen KJ, Carpenter RW, Siegel DM, Kautz MM, Liu RT, & Alloy LB (2021). Emotional response inhibition to self-harm stimuli interacts with momentary negative affect to predict nonsuicidal self-injury urges. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 142–152, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Hall ML, Strollo PJ, Kamarck TW, Owens J, Lee L, … & Matthews KA (2008). Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 4, 563–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28, 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cândea DM, & Szentágotai-Tătar A (2017). Shame as a predictor of post-event rumination in social anxiety. Cognition and Emotion, 31, 1684–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy F, Prestwich A, Caperon L, Tsipa A, & O’Connor DB (2020). The association between worry and rumination with sleep in non-clinical populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 14, 427–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RC, Cole DA, Kramer EL, & Olatunji BO (2018). Prospective associations between sleep disturbance and repetitive negative thinking: The mediating roles of focusing and shifting attentional control. Behavior Therapy, 49, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino A, Covanti S, Rossi Monti M, & Starcevic V (2017). Reconsidering emotion dysregulation. Psychiatric Quarterly, 88, 807–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren MK, Hooley JM, Best SG, Sagar KA, Gonenc A, & Gruber SA (2018). Prefrontal cortex activation during cognitive interference in nonsuicidal self-injury. Psychiatry research: Neuroimaging, 277, 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR (1983). Symptom Checklist-90-Revised. Towson, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Mycek PJ, & Zaldivar F (2008). Negative social evaluation, but not mere social presence, elicits cortisol responses to a laboratory stressor task. Health Psychology, 27, 116–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C, Bacchini D, & Affuso G (2019). Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and its relationships with school bullying and peer rejection. Psychiatry Research, 274, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairholme CP, & Manber R (2015). Sleep, emotions, and emotion regulation: An overview. In Babson KA & Feldner MT (Eds.), Sleep and Affect: Assessment, Theory, and Clinical Implications (pp. 45–61). London: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Fairholme CP, Nosen EL, Nillni YI, Schumacher JA, Tull MT, & Coffey SF (2013). Sleep disturbance and emotion dysregulation as transdiagnostic processes in a comorbid sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51, 540–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch JU, Häusser JA, & Mojzisch A (2015). The Trier Social Stress Test as a paradigm to study how people respond to threat in social interactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LR, Pond RS Jr, Haak EA, DeWall CN, & Keller PS (2015). Sleep problems exacerbate the emotional consequences of interpersonal rejection. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AM, & Chen S (2014). The role of sleep in interpersonal conflict: Do sleepless nights mean worse fights?. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & Jazaieri H (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 387–401. [Google Scholar]

- Grove JL, Smith TW, Crowell SE, Williams PG, & Jordan KD (2017). Borderline personality features, interpersonal correlates, and blood pressure response to social stressors: Implications for cardiovascular risk. Personality and Individual Differences, 113, 38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn HE, Troxel WM, Hall MH, & Buysse DJ (2014). Interpersonal distress is associated with sleep and arousal in insomnia and good sleepers. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 76, 242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack J, & Martin G (2018). Expressed emotion, shame, and non-suicidal self-injury. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 890–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based perspective (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff ER, & Muehlenkamp JJ (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury in college students: The role of perfectionism and rumination. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39, 576–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Ho DT, Slater J, & Lockshin A (2010). Pain perception and nonsuicidal self-injury: A laboratory investigation. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 1, 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, & St. Germain SA (2014). Nonsuicidal self-injury, pain, and self-criticism: Does changing self-worth change pain endurance in people who engage in self-injury?. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hysing M, Sivertsen B, Stormark KM, & O’Connor RC (2015). Sleep problems and self-harm in adolescence. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 207, 306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JR, Kamarck T, Stewart C, Eddy M, & Johnson P (1992). Alternate cardiovascular baseline assessment techniques: Vanilla or resting baseline. Psychophysiology, 29, 742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, & Poon KT (2021). Stuck in companionless days, end up in sleepless nights: Relationships between ostracism, rumination, insomnia, and subjective well-being. Current Psychology, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Junker A, Bjørngaard JH, Gunnell D, & Bjerkeset O (2014). Sleep problems and hospitalization for self-harm: A 15-year follow-up of 9,000 Norwegian adolescents. The Young-HUNT Study. Sleep, 37, 579–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn M, Sheppes G, & Sadeh A (2013). Sleep and emotions: Bidirectional links and underlying mechanisms. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 89, 218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmbach DA, Abelson JL, Arnedt JT, Zhao Z, Schubert JR, & Sen S (2019). Insomnia symptoms and short sleep predict anxiety and worry in response to stress exposure: A prospective cohort study of medical interns. Sleep Medicine, 55, 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiekens G, Hasking P, Claes L, Mortier P, Auerbach RP, Boyes M, … & Bruffaerts R (2018). The DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury disorder among incoming college students: Prevalence and associations with 12-month mental disorders and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Depression and Anxiety, 35, 629–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirtley OJ, O’Carroll RE, & O’Connor RC (2016). Pain and self-harm: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203, 347–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, & Hellhammer DH (1993). The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology, 28, 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazaie H, Zakiei A, McCall WV, Noori K, Rostampour M, Sadeghi Bahmani D, & Brand S (2021). Relationship between sleep problems and self-injury: A systematic review. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 19, 689–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED (2007). Non-suicidal self-injury: An introduction. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED (2011). Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: Prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychological Medicine, 41, 1981–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May AM, & Glenn CR (2013). The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: Converging evidence from four samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gu S, Wang Z, Li H, Xu X, Zhu H, … & Huang JH (2019). Relationship between stressful life events and sleep quality: Rumination as a mediator and resilience as a moderator. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT (2021). The epidemiology of non-suicidal self-injury: Lifetime prevalence, sociodemographic and clinical correlates, and treatment use in a nationally representative sample of adults in England. Psychological Medicine, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahtani S, Melvin GA, & Hasking P (2018). Shame proneness, shame coping, and functions of nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) among emerging adults: A developmental analysis. Emerging Adulthood, 6, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzer K, Boersma K, & Linton SJ (2019). A longitudinal view of rumination, poor sleep and psychological distress in adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 686–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozafari N, Bagherian F, Zadeh Mohammadi A, & Heidari M (2022). Executive functions, behavioral activation/behavioral inhibition system, and emotion regulation in adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and normal counterparts. Journal of Research in Psychopathology, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Neacsiu AD, Bohus M, & Linehan MM (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy: An intervention for emotion dysregulation. In Gross JJ (Ed.), Handbook of Emotion Regulation, 2nd edition (pp. 491–507). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolai KA, Wielgus MD, & Mezulis A (2016). Identifying risk for self-harm: Rumination and negative affectivity in the prospective prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 46, 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK (2009). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current directions in Psychological Science, 18, 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, & Michel BD (2007). Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment, 19, 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE Jr, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, & Prinstein MJ (2006). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research, 144, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson JL, Dorrian J, Ferguson SA, Jay SM, Lamond N, Murphy PJ, … & Dawson D (2011). Changes in structural aspects of mood during 39–66 h of sleep loss using matched controls. Applied Ergonomics, 42, 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti A, Carta MG, & Petretto DR (2019). Factor structure models of the SCL-90-R: Replicability across community samples of adolescents. Psychiatry Research, 272, 491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radstaak M, Geurts SA, Beckers DG, Brosschot JF, & Kompier MA (2014). Work stressors, perseverative cognition and objective sleep quality: A longitudinal study among Dutch Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) pilots. Journal of Occupational Health, 56, 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaie L, Fobian AD, McCall WV, & Khazaie H (2018). Paradoxical insomnia and subjective–objective sleep discrepancy: A review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 40, 196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson K, & Wilson MS (2020). Open to interpretation? Inconsistent reporting of lifetime nonsuicidal self-injury across two common assessments. Psychological Assessment, 32, 726–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatten HT, Andover MS, & Armey MF (2015). The roles of social stress and decision-making in non-suicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Research, 229, 983–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner MW, Klimes-Dougan B, Mueller BA, Eberly LE, Reigstad KM, Carstedt PA, … & Cullen KR (2017). Multi-modal neuroimaging of adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury: Amygdala functional connectivity. Journal of Affective Disorders, 221, 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Franklin J, Carson-Wong A, & Rizvi SL (2013). Emotional cascades and self-injury: Investigating instability of rumination and negative emotion. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 1213–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Kranzler A, Fehling KB, & Panza E (2015). Nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: The path to diagnostic validity and final obstacles. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr (2009). Cascades of emotion: The emergence of borderline personality disorder from emotional and behavioral dysregulation. Review of General Psychology, 13, 219–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh G (2009). Detecting interaction effects in moderated multiple regression with continuous variables power and sample size considerations. Organizational Research Methods, 12, 510–528. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, & Jordan KD (2015). Interpersonal motives and social-evaluative threat: Effects of acceptance and status stressors on cardiovascular reactivity and salivary cortisol response. Psychophysiology, 52, 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Germain SAS, & Hooley JM (2012). Direct and indirect forms of non-suicidal self-injury: Evidence for a distinction. Psychiatry Research, 197, 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot LS, McGlinchey EL, Kaplan KA, Dahl RE, & Harvey AG (2010). Sleep deprivation in adolescents and adults: Changes in affect. Emotion, 10, 831–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taliaferro LA, & Muehlenkamp JJ (2015). Factors associated with current versus lifetime self-injury among high school and college students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 45, 84–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tousignant OH, Taylor ND, Suvak MK, & Fireman GD (2019). Effects of rumination and worry on sleep. Behavior Therapy, 50, 558–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trockel M, Karlin BE, Taylor CB, Brown GK, & Manber R (2015). Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on suicidal ideation in veterans. Sleep, 38, 259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Cobb RJ, Gratz KL, & Chapman AL (2016). The role of interpersonal conflict and perceived social support in nonsuicidal self-injury in daily life. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125, 588–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbán R, Kun B, Farkas J, Paksi B, Kökönyei G, Unoka Z, … & Demetrovics Z (2014). Bifactor structural model of symptom checklists: SCL-90-R and Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in a non-clinical community sample. Psychiatry Research, 216, 146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanDerhei S, Rojahn J, Stuewig J, & McKnight PE (2014). The effect of shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and internalizing tendencies on nonsuicidal self-injury. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44, 317–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Laethem M, Beckers DG, Kompier MA, Kecklund G, van den Bossche SN, & Geurts SA (2015). Bidirectional relations between work-related stress, sleep quality and perseverative cognition. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 79, 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor SE, & Klonsky ED (2014). Daily emotion in non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor SE, Scott LN, Stepp SD, & Goldstein TR (2019). I want you to want me: Interpersonal stress and affective experiences as within-person predictors of nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide urges in daily life. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49, 1157–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SS, Gujar N, Hu P, Jolesz FA, & Walker MP (2007). The human emotional brain without sleep—a prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Current Biology, 17, R877–R878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.