Abstract

Littered waste is one of the ubiquitous problems in urban environments. In this study, urban environmental pollution was evaluated for the first time using a new developed index. The findings indicated that cigarette butts with an average 58% are the largest share in the composition of littered waste. In addition, the numbers of littered wastes throughout the study area had a spatial variation. According to clean environment index (CEI), the entire study area was found to be in a moderate status. However, 40% of the study areas were classified in a dirty and extremely dirty status. Comparison of the studied urban land-uses showed that residential land use with CEI equal to 3.38 is interpreted in the clean status, while commercial land use with CEI equal to 15.05 can be classified in the dirty status. The application of CEI has a good capability to assess littered waste; this index can be employed to evaluate the pollution of urban sidewalks and other environments such as beaches.

Keywords: Littered waste, environmental status, waste management, clean environment index

Introduction

Littered wastes are ubiquitous in the urban environments and are recognized as an environmental and public concern all over the world (Pon and Becherucci, 2012). Urban litter, as a persistent problem with considerable effects on residents and the urban economy, can be defined as visible solid waste throwing out from the urban environment (Pon and Becherucci, 2012). In fact, any solid material which is directly or indirectly discarded, disposed of, or abandoned in urban environments or other environments such as beaches can be considered as litter (Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019). Litter are considered as important pollutants in the environment; however, the collection process of littered wastes is impossible. Littered waste can lead to some damages in local to global scales (Williams and Rangel-Buitrago, 2019) in terms of economic, health and biological aspects (Campbell et al., 2016; Gracia et al., 2018; Krelling et al., 2017; Portman and Brennan, 2017; Williams and Rangel-Buitrago, 2019). The high cost of collecting litter from the environment is known as one of its adverse economic effects; it is reported that annually $1.4 million and €18 million have been spent for beach clean-up in different countries such as the United States, the Netherlands and Belgium (Asensio-Montesinos et al., 2020). Furthermore, some littered wastes such as cigarette butts (CBs) in urban environments have toxic effects due to the presence of various pollutants; CBs can cause pollution of water sources by leaching pollutants such as nicotine (Green et al., 2014). Given that litter characterization is an important tool for identification of the health and economic effects, this information plays an important role in management policies (Chen et al., 2020). That is why over the recent years, several studies have been focused on the quantity and composition of littered waste in different environments, especially in the beaches (Asensio-Montesinos et al., 2020; Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019). To date, there is insufficient data on the composition and effects of littered wastes in urban environments. However, CBs, paper and plastic have been identified as the most common urban litter in several cities from the Northern Hemisphere (Pon and Becherucci, 2012). Furthermore, numerous problems have been reported as a consequence of litter in cities, including high incidence of injuries caused by street glass among the children (Al-Khatib, 2009; Rizviet al., 2006). The aim of this study was to assess the quantity of littered wastes and their spatial variation in urban environment. The additional aim of present study was to compare the different land-uses in the urban environment in terms of littered waste pollution based on the developed of an index which can even be employed for different land-uses in the cities such as beaches and different cities.

Method

Study area, project design and classification of litter

This study was conducted in Qazvin, one of the provinces located in the centre of Iran. Qazvin covers an area of 64.132 km2 with 19 neighbourhoods and a population of 402,748 according to the latest official statistics (Gholami et al., 2020). Urban litter surveys were conducted during the summer of 2020. Saturdays to Wednesdays as workdays in Iran were selected to survey in this study. A total of 20 locations were selected from the urban land-uses, including residential, commercial, administrative and recreational. The both sides of street and sidewalk in all sites were surveyed. The places to be studied, hereinafter referred to as L1–L20, are as follows: Velayat Street (L1), Felestin Street (L2), Navab Street (L3), Mirdamad Street (L4), Seyed Al-Shohada Boulevard (L5), Modares Boulevard (L6), Hakim Boulevard (L7), Maliat Street (L8), Soleimani Boulevard (L9), Khoramshahr Boulevard (L10), Dadgah Street (L11), Moalem Park (L12), Al-Ghadir Park (L13), Iran Boulevard (L14), Razmandegan Boulevard (L15), Azadegan Boulevard (L16), Nokhbegan Boulevard (L17), Mellat Park (L18), Khayyam Boulevard (L19) and Daneshamoz Park (L20).

The selection of these places was based on urban uses: residential, recreational, commercial, official and various uses. In addition, some sampling points were selected with an even distribution throughout the city. According to the previous studies on littered waste composition (Gholami et al., 2020; Pon and Becherucci, 2012, Verlis and Wilson, 2020), the littered wastes were classified into five groups: plastic, paper, cigarette waste, metals, and others. Each of these classifications included one or more types of litter, which totally included 19 types of littered wastes. For instance, tobacco waste included CBs and cigarette packs; however, paper included litter such as cardboards, paper pieces (ATM receipts and the like). In addition, items such as leaves, broken pieces of tree branches and broken parts of the sidewalk were not considered as littered waste (Pon and Becherucci, 2012).

Observation and analysis

In this visual survey study, urban litter were not collected or weighted (Pon and Becherucci, 2012), However, urban litter data were obtained using field litter counts (Dieng et al., 2011; Taffs and Cullen, 2005). The survey area defined in each location included the entire sidewalk and 1 m away from the street (1, Dieng et al., 2011; Gholami et al., 2020). The time of places survey was determined in spring and summer from 5 to 8 PM and in autumn and winter from 2 to 5 PM, because in these hours, observations could be done using natural light. Given that the street cleaning schedules can affect the urban littered wastes (Dieng et al., 2011; Torkashvand et al., 2021) and conducted in the last hours of the night in Qazvin, the evening hours were chosen as the best time for places survey in this study. These hours are in consistent with the time reported in the previous studies (Ariza et al., 2008; Micevska et al., 2006; Taffs and Cullen, 2005; Torkashvand et al., 2021).

In addition, an index was needed to interpret the status of the studied sites in terms of littered waste pollution. Clean-coast index (CCI) and environmental status (ES) are two widely used indexes in the study of littered wastes (Sawdey et al., 2011; Schulz et al., 2013; Simeonova et al., 2017). However, in CCI, only the number of wastes is considered. The principal and concept of the index is based on the number of wastes per square metre of the environment and in addition, the potential risk of different types of wastes is not considered. Furthermore, in the ES index, due to the difference between the composition of littered wastes, a quality coefficient (Wi) has been determined. However, the density of the wastes is not considered in this index. Therefore, it was necessary to define a new index considering the waste density and quality difference of waste types at the same time. Therefore, the obtained data were analysed using the defined index to measure and express the severity of pollution of urban sidewalks to littered wastes. To this end, at first the density of litter in the sidewalks was obtained by dividing the number of litter by the distance studied. Given the characteristic of CCI which is used to study the littered wastes in coasts (Ribic 1998; Sawdey et al., 2011; Simeonova et al., 2017) and calculated using the quantity of litter (Formula 1), as well as the ES index (Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019; Schulz et al., 2013), which focuses on the difference in the importance of litter (Formula 2), Formula 3 was used for the first time for calculating the clean environment index (CEI) as a littered wastes assessment index. This index considers both quantity and importance of different littered wastes.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where K is a constant coefficient equal to 20 (Williams and Rangel-Buitrago, 2019) and Wi refers to a coefficient that is determined according to the type of litter (See Table 1). Ni in CEI and Xi in ES refers to number of each litter type.

Table 1.

Corresponding weights of different litter.

| Litter category | Example of litter type | Corresponding weight |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Cigarette butt, tobacco | 2 |

| Plastic | Bags (e.g. shopping), drinks (bottles, containers and drums), food containers, bottles and containers, candy and biscuit wrap, nylons | 1.5 |

| Rubber | Balloons, ribbons, boots, tires and belts | 1.5 |

| Cloth | Cloth, textiles | 1 |

| Paper and cardboard | Newspapers, tetrapak (milk or juice), cigarette packets, paper pieces, ATM receipt | 1 |

| Wood | Ice lolly sticks | 1 |

| Metal | Bottle caps, drink cans, food cans, foil wrappers | 1 |

| Glass | Bottles | 1 |

| Sanitary waste | Baby diaper, sanitary napkin, condoms, facial tissue | 2 |

Wi for each littered waste is determined based on the potential for environmental contamination or decomposition into harmful substances (Gholami et al., 2020). For instance, CB is considered as a hazardous waste due to the leakage of various pollutants such as toxins and heavy metals (Torkashvand et al., 2021). Therefore, Wi for CB was considered to be 2. In addition, Wi coefficient for facial tissue due to potential to microbial contamination was considered to be 2. Of note, plastic litter due to their durability in the environment as well as decomposition into microplastics had a Wi equivalent of 1.5 (Gholami et al., 2020). Although the Wi for all categories of litter is defined in Table 1, but in the assessed urban environment in this study, 19 prevalent litter were observed, which are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Detailed results of observations (item/100 m).

| Cigarette butt | Cigarette pocket | Paper pieces | Paper | Juice packet | Other packets | Candy wrap | Biscuit wrap | Disposable dish | Disposable cup | Drinking straw | PET bottle | Plastic bottle caps | Nylons | Juice bottle | Metal bottle caps | Glass bottle | Wood | Facial tissue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 36.1 SD 4.6 | 0.9 SD 0.6 | 1.1 SD 0.6 | 0 | 0.1 SD 0.02 | 0 | 3.2 SD 0.9 | 1.3 SD 0.51 | 0 | 0.1 SD 0.03 | 0.1 SD 0.02 | 0 | 0.1 SD 0.4 | 0.8 SD 0.19 | 0 | 0.1 SD 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 SD 0.11 |

| L2 | 57.6 SD 2.3 | 0.36 SD 0.11 | 35.16 SD 4.6 | 0.66 SD 0.11 | 0 | 0.1 SD 0.02 | 8.5 SD 1.14 | 4.2 SD 1.24 | 0.83 SD 0.36 | 1.94 SD 0.42 | 0.4 SD 0.09 | 11 SD 1.98 | 0.35 SD 0.12 | 2.3 SD 0.92 | 0.38 SD 0.09 | 1.05 SD 0.15 | 0.11 SD 0.02 | 1.16 SD 0.45 | 3.77 SD 0.91 |

| L3 | 35.8 SD 6.1 | 4.6 SD 1.2 | 41.2 SD 7.3 | 0.9 SD 0.21 | 1.2 SD 0.05 | 0.8 SD 0.12 | 3.5 SD 1.62 | 22.1 SD 7.81 | 1.3 SD 0.43 | 0.6 SD 0.14 | 1.2 SD 0.51 | 2.3 SD 0.91 | 2.6 SD 0.81 | 8.1 SD 1.24 | 2.5 SD 0.72 | 0.4 SD 0.09 | 0.2 SD 0.08 | 3.7 SD 1.11 | 6.2 SD 2.43 |

| L4 | 19.2 SD 2.2 | 0.5 SD 0.13 | 0.1 SD 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.1 SD 0.29 | 0.3 SD 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 SD 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L5 | 32 SD 1.3 | 1.2 SD 0.51 | 0.3 SD 0.09 | 0.2 SD 0.08 | 0.31 SD 0.08 | 0 | 3.7 SD 1.91 | 1.1 SD 0.44 | 0 | 0.4 SD 0.19 | 0.1 SD 0.04 | 0 | 0.4 SD 0.03 | 0.5 SD 0.15 | 0 | 0.2 SD 0.06 | 0.1 SD 0.03 | 0 | 0.6 SD 0.09 |

| L6 | 67.2 SD 4.1 | 0.81 SD 0.26 | 21.8 SD 3.9 | 0.51 SD 0.14 | 0.24 SD 0.07 | 0.11 SD 0.05 | 7.2 SD 2.51 | 5.1 SD 1.29 | 0.71 SD 0.27 | 1.25 SD 0.82 | 0.05 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0.71 SD 0.13 | 3.17 SD 1.12 | 0.52 SD 0.16 | 1.32 SD 0.49 | 0 | 1.41 SD 0.86 | 3.35 SD 1.43 |

| L7 | 3.4 SD 4.6 | 0 | 0.69 SD 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L8 | 3.1 SD 0.7 | 0 | 0.71 SD 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L9 | 204 SD 9.2 | 3.35 SD 1.34 | 38.3 SD 6.7 | 2.41 SD 0.35 | 0.17 SD 0.08 | 0.11 SD 0.06 | 22.47 SD 7.25 | 5 SD 1.84 | 6.32 SD 2.05 | 2.94 SD 0.96 | 5.11 SD 2.08 | 0.64 SD 0.14 | 5.4 SD 1.31 | 5.7 SD 1.09 | 2.41 SD 0.81 | 0.47 SD 0.14 | 0.05 SD 0.01 | 3.58 SD 1.05 | 8.41 SD 2.19 |

| L10 | 60.62 SD 5.1 | 3.9 SD 1.81 | 28.5 SD 5.1 | 3.11 SD 0.29 | 0.48 SD 0.18 | 0.9 SD 0.12 | 22.2 SD 3.57 | 12.6 SD 4.16 | 0.54 SD 0.23 | 2.12 SD 0.92 | 0.47 SD 0.09 | 0.97 SD 0.31 | 1.81 SD 0.86 | 3.19 SD 1.06 | 1.11 SD 0.79 | 1.19 SD 0.44 | 0.11 SD 0.027 | 1.17 SD 0.14 | 4.31 SD 1.01 |

| L11 | 12.6 SD 4.62.9 | 0.5 SD 0.23 | 0.15 SD 0.08 | 0.5 SD 0.16 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 SD 0.24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| L12 | 24.2 SD 1.2 | 0.03 SD 0.01 | 0.61 SD 0.21 | 0.02 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0.11 SD 0.08 | 0.22 SD 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0.04 SD 0.01 | 0.25 SD 0.06 | 0.18 SD 0.03 | 0.1 SD 0.06 | 0.3 SD 0.04 | 0.1 SD 0.02 | 0.04 SD 0.02 | 0.37 SD 0.09 |

| L13 | 3.82 SD 0.9 | 0 | 0.56 SD 0.24 | 0.01 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 SD 0.12 | 0.03 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0.05 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 SD 0.01 | 0.1 SD 0.06 |

| L14 | 16.7 SD 1.1 | 0.1 SD 0.04 | 0 | 0.1 SD 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 SD 0.22 | 0.2 SD 0.08 | 0.2 SD 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 SD 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 SD 0.09 |

| L15 | 22.4 SD 1.8 | 0.1 SD 0.03 | 0 | 0.2 SD 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 1.6 SD 0.47 | 0.5 SD 0.13 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 SD 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 SD 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 SD 0.12 |

| L16 | 133.2 SD 7.2 | 3.69 SD 1.14 | 38.42 SD 6.7 | 2.39 SD 0.18 | 0.24 SD 0.11 | 0.6 SD 0.21 | 17.12 SD 3.49 | 6.17 SD 2.07 | 2.12 SD 0.97 | 3.27 SD 1.29 | 2.34 SD 1.04 | 0.83 SD 0.25 | 4.3 SD 2.12 | 5.49 SD 2.67 | 2.41 SD 1.01 | 0.62 SD 0.13 | 0.07 SD 0.02 | 3.12 SD 1.38 | 7.67 SD 2.51 |

| L17 | 79.9 SD 3.2 | 1.93 SD 0.72 | 32.11 SD 4.4 | 2.75 SD 0.33 | 0.39 SD 0.14 | 0.12 SD 0.07 | 10.11 SD 3.45 | 4.11 SD 1.94 | 1.92 SD 0.84 | 3.07 SD 1.31 | 1.72 SD 0.87 | 5.69 SD 2.32 | 3.12 SD 1.89 | 2.44 SD 0.91 | 2.72 SD 0.88 | 1.22 SD 0.26 | 0.06 SD 0.203 | 2.66 SD 1.06 | 4.65 SD 1.66 |

| L18 | 0.85 SD 0.12 | 0 | 0.2 SD 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 SD 0.11 | 0.01 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 SD 0.07 | 0.12 SD 0.08 |

| L19 | 92.8 SD 2.2 | 0.1 SD 0.05 | 36 SD 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.38 SD 0.16 | 0.2 SD 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 SD 0.26 | 0 | 0.5 SD 0.21 | 0.7 SD 0.34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 SD 0.22 | 1.71 SD 0.43 |

| L20 | 22.8 SD 3.4 | 0.02 SD 0.01 | 0.86 SD 0.13 | 0.07 SD 0.02 | 0.11 SD 0.04 | 0.01 SD 0.01 | 0.2 SD 0.08 | 0.02 SD 0.01 | 0 | 0.05 SD 0.03 | 0.36 SD 0.14 | 0.01 SD 0.01 | 0.11 SD 0.07 | 0.26 SD 0.08 | 0.07 SD 0.03 | 0.09 SD 0.05 | 0 | 0.07 SD 0.02 | 0.24 SD 0.13 |

| Ave. | 46.41 SD 4.8 | 1.10 SD 0.4 | 13.83 SD 1.9 | 0.69 SD 0.14 | 0.16 SD 0.08 | 0.14 SD 0.06 | 5.17 SD 1.21 | 3.14 SD 1.46 | 0.69 SD 0.34 | 0.78 SD 0.19 | 0.63 SD 0.21 | 1.07 SD 0.29 | 1.01 SD 0.36 | 1.65 SD 0.31 | 0.61 SD 0.24 | 0.34 SD 0.11 | 0.04 SD 0.01 | 0.90 SD 0.42 | 2.11 SD 0.98 |

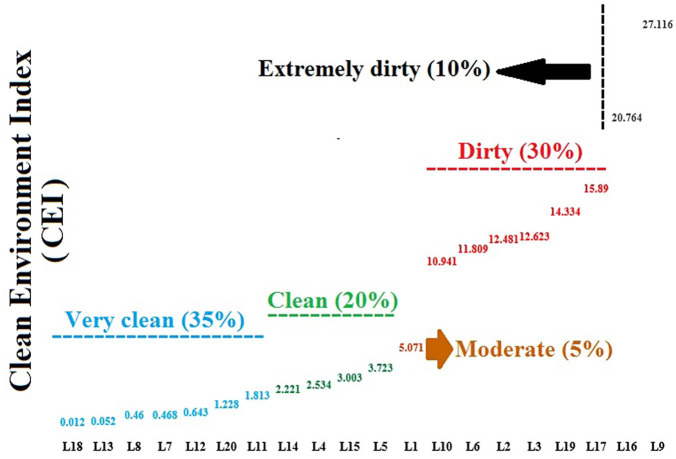

Based on this, the calculated CEI for the studied urban environments was interpreted as follows.

A: 0–2: very clean

B: 2–5: clean

C: 5–10: moderate

D: 10–20: dirty

E: 20< extremely dirty.

The classification for CEI was defined based on the classification presented in CCI into five groups. The CEI classification can be used to study and qualitatively express litter contamination in a variety of locations, including urban environments, beaches and public areas.

Results and discussion

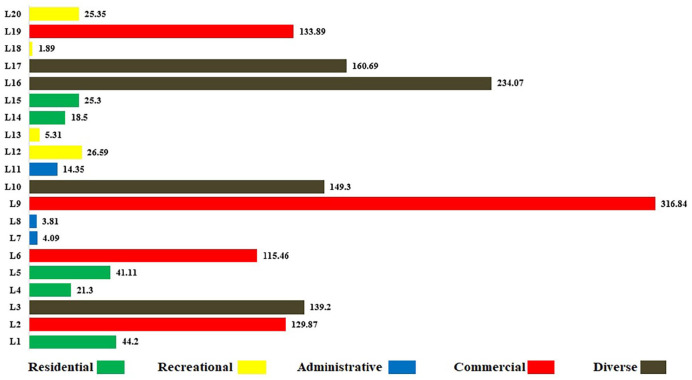

The results on the numbers of littered wastes in this study indicated an average of 80.55 items/100 m in the study areas (See Table 2). The results showed that the number of litter varied in different places. L18 with 1.89 items/100 m was found to be with the minimum littered waste, while L9 with 316.84 items/100 m was found to be places with the maximum observed littered waste among the studied places (Figure 1). The results obtained from the present study showed that CBs comprise the largest percentage of component in littered wastes. The results showed that CBs in all studied areas had the largest proportion compared to other composition of urban litter; its number range was between 0.85 and 133.2/100 m in different places (average: 44.41 CBs/100 m). On average, glass bottle, juice packet and other packets with 0.04, 0.16 and 0.14 items/100 m, respectively, formed the lowest litter proportion in all studied areas. The proportion of littered wastes in different locations is not the same. In addition, as shown in Table 2, some locations had not some type of litter; the spatial variation of urban littered wastes is observable in the studied city.

Figure 1.

Density of littered waste in studied locations (item/100 m).

The calculation of CEI for the whole city showed that the general status of the city is classified as moderate; L9 had the highest and L18 had the lowest CEI (see Figure 2). As a result, as shown in Figure 2, 35% of urban areas were classified in the very clean status, while 10% of urban sidewalks with CEI index higher than 20 were classified in the extremely dirty status.

Figure 2.

Calculated CEI for different locations.

Although several studies have been conducted to investigate the pollution of areas such as coasts and seas with litter (Asensio-Montesinos et al., 2020; Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019), there are few studies focusing on the status of littered wastes in urban environments. Over the recent years, due to the importance of CBs as one of the most prevalence wastes, studies have been conducted on this litter in cities (Green et al., 2014). In a similar study, an average of 14 items per square metre was observed in the city of Mar del Plata in Argentina; CB and paper were the most common wastes with 33% and 31%, respectively (Pon and Becherucci, 2012). Meanwhile, the shares of CBs and paper in Qazvin urban litter were found to be 57.62% and 17.7%, respectively, and the average littered waste observed in the city was 0.225 items per square metre. In Berlin, an average of 2.7 observed CBs per square metre in the study area with a significant spatial variation was reported (Green et al., 2014). In New Jersey, Cutter and colleagues observed 2321 CBs at 37 sites (Oigman-Pszczol and Creed, 2007). In other studies, in Madrid and San Diego, in addition to observing and counting CBs in the urban environment, the spatial variation of this litter was surveyed; the places around shopping centres and smoking areas, as well as places such as transportation stations had the highest density of this litter (Dieng et al., 2011; Taffs and Cullen, 2005).

The results obtained from the present research showed that similar to many beaches, the urban environment experiences the pollution due to the presence of littered wastes (Gholami et al., 2020). Therefore, urban environments similar to beaches have the pollution of littered waste. However, in most cases, temporal variation of litter in the beaches due to the difference in visitors of the beaches in different days was reported, while the results of our studies showed that littered wastes have considerable spatial variation in the urban environments. One of the important reasons behind the difference in the number and composition of observed litter in different places can be attributed to different land-uses (Gholami et al., 2020). Accordingly, as shown in Figure 1, the total number of littered wastes in different land-uses varied. The difference of average calculated CEI for different locations in each land-uses is shown in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, the recreational land-use had the best conditions (CEI = 0.483) and diverse land-use with calculated CEI of 16.43 had the worst conditions.

Table 3.

CEI of studied locations based on different land-uses.

| Land-use | Proportion | Average CEI | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential | 25% of studied areas | 3.38 | Clean |

| Administrative | 15% of studied areas | 0.913 | Very clean |

| Commercial | 20% of studied areas | 15.05 | Dirty |

| Recreational | 20% of studied areas | 0.483 | Very clean |

| Diverse | 20% of studied areas | 16.43 | Dirty |

As shown in Figure 1, the proportion of different littered wastes in Qazvin city locations varied, which is comparable to the results presented for the city Mar del Plata which showed that density of littered waste varies in different urban areas. The share of each waste in total littered waste composition is varied. Generally, throughout the study areas, CBs accounted for more than 30% of the total littered waste, while metals and wood accounted for less than 4% and 2% of the total number of urban waste, respectively (Pon and Becherucci, 2012). This difference in the proportion of the quantity of littered wastes is also evident in coastal litter (Asensio-Montesinos et al., 2020; Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019). It is important to note that, given the difference in the volume and weight of the litter, the proportion of the littered wastes does not follow the pattern of their number. For instance, in coastal area, it has been determined that although CBs are the most common type of litter; however, its volume and weight form a small proportion of total littered wastes. As shown in Figure 1, the number of littered wastes counted in the 20 locations and the proportion of different littered waste in these places vary. Therefore, it can be concluded that the distribution of littered wastes is not the same in different urban areas; a different spatial variation is observed in urban waste.

The indexes used in the study of littered waste are influenced by the quantity; the worse interpretation belonged to locations with increasing number of waste. In general, the influencing factors in changing the types of waste in different areas and at different times are listed as follows (Gholami et al., 2020; Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019; Torkashvand et al., 2021):

✓ The difference in land use that affects the local population

✓ Possible differences in the methods and quality of clean-up services

✓ Existence of point centres with the potential of the existence of a particular dump

✓ Structural differences in passages which can create a place for waste accumulation following limited access for cleaning up

✓ The width of the passages and its effect on the density of people per square metre

✓ The impact of business owner activity on cleaning the passages of your business area

✓ The effect of wind and rain currents on the transfer and aggregation of waste

✓ Material of roads and its ability to clean up by the municipal service system

This variation has been observed in other urban areas in the previous studies (Green et al., 2014; Marah and Novotny, 2011; Pon and Becherucci, 2012; Valiente et al., 2020). Pon and Becherucci reported that in four urban areas with different land-uses, the number of litter was different from each other (Pon and Becherucci, 2012). In addition, the results of other studies also reported the different spatial variation for litter such as CB in the urban environment. The most possible reason behind this is attributed to the existence of different urban land-uses in different areas (Gholami et al., 2020; Marah and Novotny, 2011; Valiente et al., 2020).

The results obtained from the present study showed that in recreational land-use, the number of urban littered wastes was the minimum compared to other land-uses. Commercial land-use had more littered wastes than other urban land-uses. Observations also showed that in some places, there was a higher density of litter in some sites. For instance, near ATMs, banks and commercial centres, littered paper had the maximum density. In addition, around cafes and fast food workshop, the number of littered disposable dish or cup and drinking straw was more than that of other areas. However, the highest density of CBs was observed around the places provide the such as stalls and supermarkets, as well as parks. However, the overall density of littered wastes was seen at the intersection of the city’s central commercial streets. According to the open literature, many studies have reported the high density of littered CBs around the public places including public transportation stations such as subways and buses which are in consistent with our study (Green et al., 2014; Marah and Novotny, 2011; Valiente et al., 2020). On the other hand, a very important factor in the number of urban litter in different areas is population density. Naturally, it is expected that increased population growth in the urban area leads to increased presence of people in the streets and accordingly increase and the amount of littered wastes. In case of commercial and busy urban land-uses, the increased number of visitors during the day increases the potential for waste disposal in these areas. An obvious example for the increased littered waste is increased CBs in urban areas (Ariza and Leatherman, 2012; Rath et al., 2012; Taffs and Cullen, 2005). The quality of clean-up services (Valiente et al., 2020) and the physical characteristics of the passages that affect access to littered waste for the urban cleaning (Green et al., 2014) are among the factors, affecting the density of urban littered wastes in the sidewalks. In Qazvin, the municipal services throughout the city are the same; however, the existence of tree pits and bushes in the passages and tables of surface runoff has made it difficult to access the littered waste in these places; these places cannot be properly cleaned (Torkashvand et al., 2021).

The use of CEI in this study showed that this index is very useful in the qualitative interpretation of urban environments in terms of pollution from littered wastes. Comparison of CEI with two widely used indices (ES and CCI) which often used to study the coastal environments shows that the effect of the number of littered waste and Wi in the calculation of CEI has led to different interpretation of the existing conditions. In experience of CCI and ES to study beaches, considering one of the aspects of number or Wi in calculating the index would lead to different interpretations of the pollution status (Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019).

The comparison between the indexes used in the study of waste is shown in Table 4. A major difference between CEI and other indexes is the difference in the littered waste in terms of potential for environmental damage.

Table 4.

A comparative status of litter based on different indexes.

| WAR (item/m2/day) | WAI | CCI | ES | CEI | CBPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 0.000001 Extremely low |

⩽1 Extremely low |

0–2 Very clean |

1 Good |

0–2 Very clean |

⩽1 Very low pollution |

| (2) | 0.00001 Very low |

1–2 Very low |

2–5 Clean |

2 Moderate |

2–5 Clean |

1.1–2.5 Low pollution |

| (3) | 0.0001 Low |

2–3 Low |

5–10 Moderate |

3 Unsatisfactory |

5–10 Moderate |

2.6–5 Pollution |

| (4) | 0.001 Moderate |

3–4 Moderate |

10–20 Dirty |

4 Bad |

10–20 Dirty |

5.1–7.5 Significant pollution |

| (5) | 0.01 High |

4–5 High |

20< Extremely dirty |

– | 20< Extremely dirty |

7.6–10 High pollution |

| (6) | 0.1 Very high |

5–6 Very high |

– | – | – | ⩾6 Sever pollution |

| (7) | 1 Extremely high |

⩾6 Extremely high |

– | – | – | – |

CBPI: cigarette butt pollution index; WAI: waste accumulation index; WAR: waste accumulation rate.

While most indexes only involve the quantity of waste for ranking the status, in CEI, by defining Wi, in addition to the quantity, the potential for damage caused by different litter to the environment is effective in classifying the situation. Another point is the number of ranks in each index, which can indicate the different situations from the best to the worst. In this respect, CEI, like CCI, has five classifications, while ES has four classifications. In addition, the waste accumulation index and waste accumulation rate have seven classifications (Loizia et al., 2021; Voukkali et al., 2021).

Due to the difference of littered wastes that is evident in Wi for each type of littered waste, the impact of different types of littered waste on the CEI index is different. Due to the potential for contamination in littered wastes such as facial tissue and CBs (Gholami et al., 2020; Torkashvand et al., 2021), the impact of such litter on the CEI index is greater than the other littered wastes. However, the number of littered wastes is recognized as an important factor in the CEI index and will increase the quantity led to increasing final calculated number in the index. For instance, in many coastal and urban areas, CBs have been identified as the most common littered waste (Gholami et al., 2020; Pon and Becherucci, 2012), which can have a greater impact compared with other litter on the index. In our study, CBs were the most important urban litter; it has the highest contribution on CEI calculation in the study areas for two reasons: high relative frequency among the types of littered wastes and also higher Wi due to pollution emission potential. The difference in the contribution of different litter in the CEI of some of the study sites based on sensitive analyses is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Contribution of different litter in the CEI (%).

| Location | CEI | Cigarette butt | Paper pieces | Candy wrap | Nylons | Facial tissue | Plastic bottle caps | Other litter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average of locations | 7.359 (moderate) | 69.39 | 11.00 | 3.84 | 1.95 | 3.24 | 1.15 | 9.43 |

| L1 | 5.071 (moderate) | 88.98 | 1.35 | 3.94 | 1.47 | 0.73 | 0.18 | 3.35 |

| L3 | 12.623 (dirty) | 37.81 | 21.75 | 1.84 | 6.41 | 6.54 | 2.05 | 23.6 |

| L9 | 27.116 (extremely dirty) | 75.23 | 7.06 | 4.14 | 1.57 | 3.10 | 1.49 | 7.41 |

| L13 | 0.0529 (very clean) | 82.52 | 6.04 | 7.56 | 0 | 2.16 | 0.81 | 0.91 |

| L15 | 3.003 (clean) | 93.24 | 0 | 3.33 | 0.62 | 0.83 | 0 | 1.98 |

Although CBs were the most important littered waste in the CEI index calculated for the studied city in terms of quantity as well as potential for environmental hazards, other wastes are also their important contribution. Plastic is one of the most important wastes and has been introduced as the most abundant waste in many studies (Asensio-Montesinos et al., 2019).

In this study, plastics accounted for approximately 14% of the total number of littered wastes observed. However, compared to the number parameter, plastic has a larger share of volume in many studies and plastic has been identified as an environmental threat (Terzi et al., 2020).

For this reason, Wi was considered equal to 1.5 for all types of plastics. Table 6 lists some of the reports on the number of discarded plastics.

Table 6.

The status of plastic littered waste in similar studies.

| Location | Remarks | Year | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia | • The littered pollution status of 26 beaches was

investigated • Plastic and polystyrene together accounted for 88% of total waste • The number of plastics in the studied areas varied from 0.08 to 11.2 items/100 m • An average of 0.56 items per metre for plastic and 0.33 items per metre for polystyrene were observed |

2019 | Rangel-Buitrago et al. (2019) |

| Turkey | • A long-term study on littered pollution index in

beaches • 79.6% of total littered waste was plastics • In terms of weight, plastic accounted for 38.5% of waste • The coastal areas of Black Sea in Turkey, Bulgaria and Romania showed that plastics comprise 50–95% of total littered waste |

2020 | Terzi et al. (2020) |

| Iran | • In terms of number, 14.13% of total littered wastes were

plastics • The number of littered plastics was higher in the busy commercial centres of the city • Candy warp was the largest number of plastics observed |

2021 | This study |

Discarded plastics in public environments such as beaches can be broken down into microplastics. These substances in the form of microfibers are a serious threat to marine environments and human following entrance to the food chain (Okuku et al., 2021). It is important to note that, in urban environments due to continuous and daily clean-up and also long time required for decomposition of plastic into microfiber fibres, this phenomenon is not observed in urban environment.

Conclusion

The CEI was first used to assess littered wastes in urban environments. The results showed that although the littered wastes had spatial variation, on average, glass bottles and packets were the least observed urban litter, while CBs and paper pieces were the most littered waste. Different land-uses had different status due to their effect on population density and the high potential littering sites; administrative land-uses with a CEI of 0.913 was classified in very clean condition, while commercial land use and diverse land use with CEI of 15.05 and 16.43, respectively, were considered in the dirty state. The highest calculated CEI (27.11) belonged to the L9 that is a commercial street.

Footnotes

Author contributions: The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support given by Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant Number 98-2-2-15471)

ORCID iDs: Mahdi Farzadkia  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7795-9461

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7795-9461

Javad Torkashvand  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5570-4601

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5570-4601

References

- Al-Khatib IA. (2009) Children’s perceptions and behaviour with respect to glass littering in developing countries: A case study in Palestine’s Nablus district. Waste Management 29: 1434–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariza E, Jiménez JA, Sardá R. (2008) Seasonal evolution of beach waste and litter during the bathing season on the Catalan coast. Waste Management 28: 2604–2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariza E, Leatherman SP. (2012) No-smoking policies and their outcomes on US beaches. Journal of Coastal Research 28: 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Asensio-Montesinos F, Anfuso G, Ramírez MO, et al. (2020) Beach litter composition and distribution on the Atlantic coast of Cádiz (SW Spain). Regional Studies in Marine Science 34: 101050. [Google Scholar]

- Asensio-Montesinos F, Anfuso G, Williams AT. (2019) Beach litter distribution along the western Mediterranean coast of Spain. Marine Pollution Bulletin 141: 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell ML, Slavin C, Grage A, et al. (2016) Human health impacts from litter on beaches and associated perceptions: A case study of ‘clean’ Tasmanian beaches. Ocean & Coastal Management 126: 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Wang S, Guo H, et al. (2020) A nationwide assessment of litter on China’s beaches using citizen science data. Environmental Pollution 258: 113756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieng H, Saifur RG, Ahmad AH, et al. (2011) Discarded cigarette butts attract females and kill the progeny of Aedes albopictus. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 27: 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholami M, Torkashvand J, Kalantari RR, et al. (2020) Study of littered wastes in different urban land-uses: An 6 environmental status assessment. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering 18: 915–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia A, Rangel-Buitrago N, Flórez P. (2018) Beach litter and woody-debris colonizers on the Atlantico department Caribbean coastline, Colombia. Marine Pollution Bulletin 128: 185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green ALR, Putschew A, Nehls T. (2014) Littered cigarette butts as a source of nicotine in urban waters. Journal of Hydrology 519: 3466–3474. [Google Scholar]

- Krelling AP, Williams AT, Turra A. (2017) Differences in perception and reaction of tourist groups to beach marine debris that can influence a loss of tourism revenue in coastal areas. Marine Policy 85: 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Loizia P, Voukkali I, Chatziparaskeva G, et al. (2021) Measuring the level of environmental performance on coastal environment before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study from Cyprus. Sustainability 13: 2485. [Google Scholar]

- Marah M, Novotny TE. (2011) Geographic patterns of cigarette butt waste in the urban environment. Tobacco Control 20: i42–i44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micevska T, Warne MSJ, Pablo F, et al. (2006) Variation in, and causes of, toxicity of cigarette butts to a cladoceran and microtox. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 50: 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuku E, Kiteresi L, Owato G, et al. (2021) The impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on marine litter pollution along the Kenyan Coast: A synthesis after 100 days following the first reported case in Kenya. Marine Pollution Bulletin 162: 111840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oigman-Pszczol SS, Creed JC. (2007) Quantification and classification of marine litter on beaches along Armação dos Búzios, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Journal of Coastal Research 23: 421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Pon JPS, Becherucci ME. (2012) Spatial and temporal variations of urban litter in Mar del Plata, the major coastal city of Argentina. Waste Management 32: 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portman ME, Brennan RE. (2017) Marine litter from beach-based sources: Case study of an Eastern Mediterranean coastal town. Waste Management 69: 535–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Buitrago N, Mendoza AV, Gracia A, et al. (2019) Litter impacts on cleanliness and environmental status of Atlantico department beaches, Colombian Caribbean coast. Ocean & Coastal Management 179: 104835. [Google Scholar]

- Rath JM, Rubenstein RA, Curry LE, et al. (2012) Cigarette litter: Smokers’ attitudes and behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9: 2189–2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribic CA. (1998) Use of indicator items to monitor marine debris on a New Jersey beach from 1991 to 1996. Marine Pollution Bulletin 36: 887–891. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi N, Luby S, Azam SI, et al. (2006) Distribution and circumstances of injuries in squatter settlements of Karachi, Pakistan. Accident Analysis & Prevention 38: 526–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawdey M, Lindsay RP, Novotny TE. (2011) Smoke-free college campuses: No ifs, ands or toxic butts. Tobacco Control 20: i21–i24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz M, Neumann D, Fleet DM, et al. (2013) A multi-criteria evaluation system for marine litter pollution based on statistical analyses of OSPAR beach litter monitoring time series. Marine Environmental Research 92: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeonova A, Chuturkova R, Yaneva V. (2017) Seasonal dynamics of marine litter along the Bulgarian Black Sea coast. Marine Pollution Bulletin 119: 110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taffs KH, Cullen MC. (2005) The distribution and abundance of beach debris on isolated beaches of northern New South Wales, Australia. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 12: 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Terzi Y, Erüz C, Özşeker K. (2020) Marine litter composition and sources on coasts of South-Eastern Black Sea: A long-term case study. Waste Management 105: 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torkashvand J, Godini K, Jafari AJ, et al. (2021) Assessment of littered cigarette butt in urban environment, using of new cigarette butt pollution index (CBPI). Science of the Total Environment 769: 144864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente R, Escobar F, Pearce J, et al. (2020) Estimating and mapping cigarette butt littering in urban environments: A GIS approach. Environmental Research 183: 109142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verlis KM, Wilson SP. (2020) Paradise trashed: Sources and solutions to marine litter in a small island developing state. Waste Management 103: 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voukkali I, Loizia P, Navarro Pedreño J, et al. (2021) Urban strategies evaluation for waste management in coastal areas in the framework of area metabolism. Waste Management & Research 39: 448–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AT, Rangel-Buitrago N. (2019) Marine litter: Solutions for a major environmental problem. Journal of Coastal Research 35: 648–663. [Google Scholar]