Abstract

Biological agents are widely used for the management of systemic rheumatic diseases (SRDs) and their therapeutic implications have been expanded beyond inflammatory arthropathies to more complicated autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, and systemic sclerosis. The aim of this study was to investigate treatment satisfaction and overall experience of SRDs’ patients receiving biologics as well as to explore patient’s perspectives on the quality of services provided by rheumatology departments and to determine factors related to the level of satisfaction. We performed a synchronous correlation study. Patients with SRDs answered an anonymous questionnaire assessing their satisfaction and how treatment with biologics has affected their quality of life and functionality. Sample consisted by 244 patients (65.2% women), with mean age of 50.4 years, and the most common diagnosis was rheumatoid arthritis (37.3%). Sixty one percent of patients received intravenous therapy and 39% subcutaneously. Overall, 80.5% of the patients reported a positive/very positive effect of their treatment on their life. The average total patient satisfaction from the unit was 79.8%. The presence of mental disease was significantly associated with less positive impact of the treatment on patients’ life, worse quality of life, and greater pain. In conclusion, patients with a broad spectrum of SRDs were generally satisfied and treatment with biologic regimens appeared to have a positive impact on several aspects of their life. The majority of patients were at least satisfied with all the characteristics of the unit staff and better quality of life was associated with greater satisfaction about the Unit and more positive affect of the treatment in patients’ life.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00296-023-05280-y.

Keywords: Patient satisfaction, Biologic therapy, Rheumatic diseases, Quality of life, Patient-reported outcomes, Physical function

Introduction

Systemic rheumatic diseases (SRDs) constitute a major cause of disability throughout the world with considerable financial and social consequences on all societies even in countries with well-developed health systems [1, 2]. On the top of physical impairment and loss of activity, SRDs have a considerable impact on the mental realm, as individuals are unable to overcome limitations in performing roles relating to family, social, and working life all of which exacerbate the occurrence of anxiety disorders and culminate in reduction of quality of life [3–7]. SRDs represent one of the main reasons for absenteeism and long-term dysfunction in the working population, i.e., in people aged 19–65 years [2, 6].

Over the last two decades, the management of SRDs has been revolutionized by the introduction of biological therapies [8–10]. The administration of these drugs has led to an unquestionable improvement in the overall management across the whole spectrum of subjects with SRDs including not only patients with inflammatory arthritis but also individuals suffering from systemic vasculitis [11], systemic sclerosis (SSc) [12], and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The clinical aspects of biological therapy have been extensively investigated in well-controlled clinical trials and observational studies [8, 9].

Besides detailed documentation of clinical efficacy, less attention has been paid in other aspects of treatment with targeted therapies in subjects with SRDs including patient satisfaction or disadvantage of the therapy. In fact, the route of administration, the duration of treatment, and the adverse effects particularly during COVID-19 pandemic coupled with patients’ beliefs about biologic drugs should be taken into account [13]. In addition, discrepancies between patients and physicians in their perceptions of disease activity status and success of treatment pose more difficulties in optimal management of SRDs, adherence to treatment, and improvement of quality of life in this population [14, 15].

The assessment of satisfaction in complicated conditions such as SRDs requires adequate data and information directly obtained by the patients through surveys and questionnaires covering a broad range of patient preferences, attitudes, and values including the impact of the therapies in daily, social, and professional life. In this regard, validated structured instruments may not be able to capture the several aspects across the whole spectrum of SRDs. Previous studies have addressed patients’ perceptions and satisfaction in persons with rheumatoid arthritis [16] and other inflammatory arthropathies [10, 17, 18] treated with subcutaneous biological drugs. However, the level of satisfaction of both intravenous and subcutaneous targeted therapies in individuals suffering not only from inflammatory arthropathies but also from more systemic autoimmune disorders, such as SLE, SSc, and systemic vasculitis, has not been evaluated.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to explore the treatment satisfaction and the underlying related factors, as well as the effect of biologics on quality of life and physical and mental function in individuals with SRDs on therapy with subcutaneous and intravenous biologic agents. Specific aspects of intravenous therapy regarding clinic facilities, and satisfaction from medical and nursing stuff for were also assessed.

Methods

Design

We conducted a descriptive study using a cross-sectional survey design. The survey was launched between September 2019 until March 2021 in territory centers hospitals namely Hippokration Hospital of Thessaloniki and University Hospital of Ioannina, whereas a small fraction of patients (11.47%) was recruited from other rheumatology centers.

Patients

Adult individuals suffering from SRDs requiring treatment with intravenous or subcutaneous biologic disease modifying drugs at the time of the survey as per physician decision were eligible for the study. All patients attending day-case unit for intravenous treatment and/or outpatient clinic were recruited in the study providing that they were on therapy with biologic agents for the underlying systemic autoimmune disease. The patients were asked to fill the questionnaire during their attendance in clinic or day-case unit and they returned it in the same visit/day.

Ethical consideration

All the participants provided written informed consent. The study received approval from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Ethics Committee and was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The distribution of the questionnaires to the patients was approved by the Scientific Boards and the Bioethics Committees of the Hospitals, the Medical Directors of the rheumatology clinics approved the cooperation request, and their completion and collection were anonymous. The letter accompanying the survey questionnaire to the participants described at length its intention and purposes, the consent of the researchers, and the commitment on the part of the researchers to maintain anonymity in the processing of the data. All questionnaires distributed were returned answered despite of the emergency conditions of the pandemic.

Assessments

Sociodemographic parameters and clinical characteristics were recorded. An anonymous questionnaire of 99 questions was distributed (see Supplement), which essentially consisted of 5 total domains: (1) demographics and clinical characteristics of the patient, (2) Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), (3) Questionnaire for the Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF), (4) Satisfaction and dissatisfaction questionnaire from the treatment with biological agents, and (5) Patient satisfaction questionnaire from the rheumatology unit.

All the necessary permits for the questionnaires were requested and received from the authors, while the questionnaires for Health Assessment (HAQ) and Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF), had already been translated and weighted in the Greek population [19, 20].

The recording of the subjective perception of physical dysfunction of the patients participating in the study was achieved through the HAQ Questionnaire. The HAQ is composed of 9 items investigating 2 domains: daily activities (Physical Dysfunction Scale) and the Visual Analogue Scale for Pain. Regarding the Scoring Procedure of the Disability Index for disability dimension: Range Score 0–3 (4-point scale for the disability items: DRESSNEW, RISENEW, EATNEW, WALKNEW, HYGNEW, REACHNEW, GRIPNEW, ACTIVNEW 0 = without any difficulty, 1 = with some difficulty, 2 = with much difficulty, and 3 = unable to do), where higher scores indicate greater dysfunction): (A) the highest score reported for any component question of the eight categories (DRESSNEW, RISENEW, EATNEW, WALKNEW, HYGNEW, REACHNEW, GRIPNEW, ACTIVNEW) determines the score for that category, (B) If either devices and/or help from another person are checked for a category (DRSGASST, RISEASST, EATASST, WALKASST, HYGASST, RCHASST, GRIPASST, and ACTVASST), then the score is set to “2”, but if the patient’s highest score for that subcategory is a two, it remains a two, and if a three, it remains a three, and (C) a global score is calculated by summing the scores for each of the categories and dividing by the number of categories answered [21, 22].

The questionnaire for patient satisfaction from the rheumatology clinic was designed by Barbosa L, Ramiro S and their collaborators. Satisfaction was measured using a visual proportional scale (0–100, where 0 dissatisfied, 100 completely satisfied), while further information was collected on rheumatology unit physical condition, waiting time, and satisfaction with the role of medical, nursing, and administrative staff (level of satisfaction with their friendliness, providing care, privacy in consultation, and clarity in the information provided) [23].

Satisfaction and discontent of patients with rheumatic diseases from their treatment with biological drugs were assessed using a questionnaire designed by Kotulska A, Kucharz E, and their colleagues. The researchers used the questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction in specific aspects of human activity: physical condition, emotional state, financial condition, professional performance, family and sexual life, and free time [10].

Regarding the last two questionnaires: their relevant permissions were obtained from the researchers, then translation-back translation was carried out of the questionnaires, and finally, the reliability indicators were checked.

Finally, the questionnaire was filled from ten patients at the beginning of the study in terms of a pilot study and some minor revisions were performed according to their comments. All WHO-BREF dimensions and patient satisfaction scores had a Cronbach’s a greater that 0.7 indicating good internal consistency reliability.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation) or as median (interquantile range). Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Spearman correlations coefficients (rho) were used to explore the association of two continuous variables. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check normality of the data. The satisfaction among physicians, nurses, and administration personnel was compared with paired t test. HAQ score was compared between patients with a mental disease and those without one with Mann–Whitney test. Multiple linear regression analyses, in a stepwise method (p < 0.05 for entry and p > 0.10 for removal), were used with dependent the variables presented patients’ satisfaction and positive affect of treatment in their life. The regression equation included terms for all patient’s characteristics as well as HAQ subscales. Adjusted regression coefficients (β) with standard errors (SE) were computed from the results of the linear regression analyses. Internal consistency of the satisfaction scores was evaluated via Cronbach’s alpha. All reported p values are two-tailed. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 and analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software (version 22.0).

Results

Characteristics of study population

Sample consisted of 244 patients (65.2% women), with mean age of 50.4 years (± 13.7 years). All the participants returned completed questionnaires. Demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The most common diagnosis was rheumatoid arthritis (37.3%), followed by Ankylosing spondylitis (18.9%). Median time from their diagnosis was 12 years (IQR: 5–20 years). Almost two-thirds of the patients (60.7%) were on intravenous biologic drugs, half of which (48.8%) received their treatment in a public hospital. Moreover, 10.8% of the participants were actively involved in a patient organization about their disease, 40.5% suffer from other physical disease, and 14.5% suffer from some mental disease.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics

| Ν (%) | |

|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 244 |

| Gender | |

| Men | 85 (34.8) |

| Women | 159 (65.2) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 50.4 (13.7) |

| Educational status | |

| None/primaryschool | 46 (18.9) |

| Middle/high school | 121 (49.6) |

| University/M.Sc./Ph.D. | 77 (31.6) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 91 (37,3) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 46 (18.9) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 45 (18.4) |

| Lupus | 29 (11.9) |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 14 (5,7) |

| Vasculitis | 10 (4.1) |

| Systemic sclerosis or systemic scleroderma | 8 (3.3) |

| Sjogren’s syndrome | 7 (2.9) |

| Years from diagnosis median (IQR) | 12 (5–20) |

| Number of treatments per month, median (IQR) | 1 (0.5–2) |

| Intravenous administration | 149 (61) |

| Subcutaneous administration | 95 (39) |

| Adjunctive therapy for rheumatic disease | 148 (60.9) |

| Involvement in patient associations | 26 (10.8) |

| Comorbidities | 96 (40.2) |

| Mental disease | 35 (14.5) |

| Depression | 25 (71,4%) |

| Unknown | 4 (11.4%) |

| Stress/anxiety disorder | 2 (5.7%) |

| Mixed depressive anxiety disorder | 2 (5.7%) |

| Drug-induced depression (3 days after taking medication) | 1 (2.9) |

| Compulsiveness | 1 (2.9) |

Impact of rheumatic disease

Forty-two percent of participants had low level of physical activity (IPAQ), in contrast to 30.5% who reported high level. Median total HAQ score was 1 (IQR 0.38–1.38). Mean pain score was 40.7% (± 29.7%) and mean health status was 40.2% (± 26.9%).

Medication satisfaction and perceived treatment efficacy

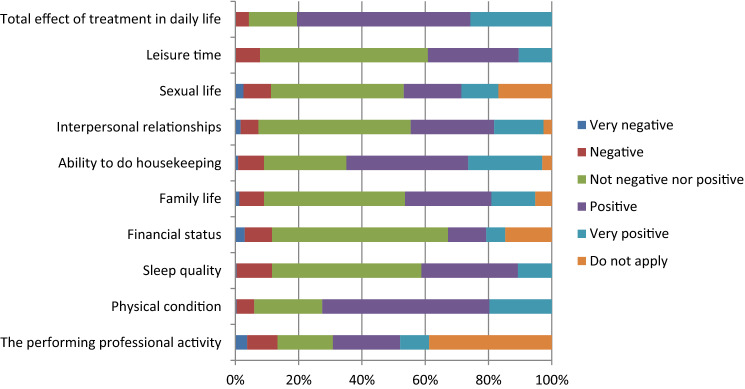

The perception of patients regarding the impact of biologic treatment on daily activities was very satisfactory (Fig. 1). More specifically, 52.8% of the patients reported positive effect in their physical condition, 30.5% in their sleep quality, and 38.5% in their ability to do housekeeping. In other aspects, such as financial status, family life, interpersonal relationships, sexual life, and leisure time, the majority of the patients did not mention any negative or positive effect. Overall, 80.5% of the patients stated that biologic treatment had a positive/very positive effect on their life, with > 80% admitting being satisfied or very satisfied regardless of the route of administration.

Fig. 1.

Effect of biological therapy on various aspects of patients’ life

Infrastructure facilities and rheumatology department satisfaction

Similarly satisfaction rates from the unit and the facilities provided by the hospital such as easy access from the hospital entrance to day-case unit, waiting time, and room size were high too, with the exception of area decoration (Supplementary Table 1). With regards to the rheumatology department itself, 61% of patients were aware of contact details and 81.8% reported efficiency of telephone contact in case of urgency and 91.4% easy access to the Rheumatology clinic in urgent situation. Mean overall satisfaction from the unit and the department was 79.8% (± 16.4%). Traveling to the hospital was difficult for 28.6% of the patients but otherwise requirements for biologic treatment, namely laboratory tests and blood sampling, waiting period for administration were characterized as unimportant issue by the majority of the participants.

Medical staff satisfaction

Patients’ satisfaction from physicians, nurses, and administration is presented in Supplementary Table 2. At least satisfied were most of the patients from the physician, nurse, and administration personnel. Mean physician score was 14.5 (SD = ± 4.5), mean nurse score was 14.7 (± 4.6), and mean administration score was 10.5 (± 4.2). Participants were significantly more satisfied from the physicians and the nurses compared to the administration personnel (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). Higher satisfaction from physicians, nurses, and administration was significantly associated with higher overall satisfaction. Also, satisfaction from physicians, nurses, and administration was significantly and positively associated among each other. On the contrary, the satisfaction from the physicians and the nurses was similar (p = 0.27). Acceptable internal consistency was found in all three scores, i.e., Cronbach’s a greater than 7.

Determinants of patients’ satisfaction

With regards to patient-reported outcomes, greater HAQ score was significantly associated with greater pain (rho = 0.61; p < 0.001) and lower treatment effect (rho = − 0.17; p = 0.006) as expected. HAQ score was not significantly associated with total satisfaction from the unit (rho = − 0.11; p = 0.112). On the other hand, there was no significant difference in the satisfaction of the participants with the method of administration of the drug, between the two methods of administration, as can be seen in Table 2. Moreover, satisfaction levels were compared between patients with inflammatory arthritis (RA + AS) and the others, and no significant differences were found.

Table 2.

Satisfaction of the participants with the method of administration of the drug, between the two methods of administration

| As part of your treatment you receive Biological Agents with | p Fisher's exact test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous administration | Subcutaneous administration | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Method of drug administration (Biological agent) | |||||

| Very negative | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 2.4 | 0,28 |

| Negative | 8 | 7.0 | 10 | 12.0 | |

| No effect | 105 | 92.1 | 71 | 85.5 | |

Significantly greater HAQ score had participants with a mental disease compared to those without a mental disease [median (IQR): 1.13 (0.75–1.63) vs 0.75 (0.25–1.38); p = 0.002]. Participants having a mental disease (depression, stress/anxiety disorder, and mixed depressive anxiety disorder) had significantly worse quality of life (QoL), compared to those without a mental disease (p < 0.001 for all QoL subscales). Also, participants with a mental disease were significantly more satisfied from the treatment they received (p = 0.017) and they had significantly greater pain according to VAS scale (p = 0.009)-Supplementary Tables 3A and 3B. In multiple regressions analysis, the presence of mental disease was significantly associated with less positive effect of the treatment in patients’ life (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression results in a stepwise method

| Dependent variable | Independent variables | β + | SE++ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect of treatment in daily life (scale 0–4) | Mental disease | No (reference) | |||

| Yes | − 0.054 | 0.017 | > 0.001 | ||

| Reach | − 0.018 | 0.007 | > 0.001 | ||

| Total satisfaction score about the unit (scale 0–100) | Are you actively involved in any organization about your disease? | No (reference) | |||

| Yes | − 0.078 | 0.024 | 0.001 | ||

| Walking | − 0.023 | 0.010 | 0.03 | ||

| Physician score (0–20) | Walking | − 0.039 | 0.015 | > 0.001 | |

| Are you actively involved in any organization about your disease? | No (reference) | ||||

| Yes | − 0.102 | 0.035 | > 0.001 | ||

| Age | − 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.02 | ||

| Nurse score (0–20) | Are you actively involved in any organization about your disease? | No (reference) | |||

| Yes | − 0.102 | 0.032 | > 0.001 | ||

| Walking | − 0.040 | 0.013 | > 0.001 | ||

| Administrative score (0–20) | Walking | − 0.064 | 0.020 | > 0.001 |

+ Regression coefficient; + + standard error

Moreover, greater Reach score thus greater dysfunction regarding their ability to reach—as analyzed in the survey tool section and refers to the patient’s ability to reach various objects—was significantly associated with less positive effect of the treatment in patients’ life (r = − 0.018, p > 0.001). Patients who were actively involved in an organization about their disease had significantly lower satisfaction regarding the unit (r = − 0.078, p = 0.001), the physicians (r = − 0.102, p > 0.001), and the nurses (r = − 0.102, p > 0.001). Also, greater dysfunction regarding their ability to walk was significantly associated with lower satisfaction regarding the unit (r = − 0.023, p = 0.03), the physician (p = − 0.039, p > 0.001), nurse ( r = − 0.040, p > 0.001), and administration personnel (r = − 0.064, p > 0.001). Furthermore, as age increased, the satisfaction from the physicians diminished significantly (r = − 0.002, p = 0.02).

Finally, when quality-of-life scores were correlated with patients’ satisfaction (Table 4), it was found that in most cases, there were significant positive correlations among them, indicating that better quality of life was associated with greater satisfaction and more positive effect of the treatment in patients’ life.

Table 4.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients between patients’ satisfaction scores and WHO-Bref scales

| Physician score (0–20) | Nurse score (0–20) | Administrative score (0–20) | Total effect of treatment in daily life (scale 0–4) | Total satisfaction score about the unit (scale 0–100) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall QoL/health facet | |||||

| Rho | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.13 |

| p | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | < 0.001 | 0.07 |

| Physical health and level of independence | |||||

| Rho | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.04 |

| p | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.27 | < 0.001 | 0.62 |

| Psychological health and spirituality | |||||

| Rho | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.16 |

| p | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.02 |

| Social relationships | |||||

| Rho | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| p | 0.001 | > 0.001 | 0.01 | > 0.001 | 0.03 |

| Environment | |||||

| Rho | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.18 |

| p | > 0.001 | > 0.001 | > 0.001 | 0.27 | 0.01 |

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate high rates of satisfaction among individuals with SRDs treated with biologic disease modifying drugs. It is worth noting that patient’s perception in the current survey covers different aspects of treatment with biologic agents ranging from disease outcomes, such as quality of life, daily activities, and emotional well-being to satisfaction from hospital services, medical and administrative staff, as well as rheumatology unit itself.

Due to the expanded use of biological drugs in the treatment of inflammatory rheumatic diseases, rheumatology departments have adapted to this reality, to ensure high levels of quality in the care delivered. The biological therapies are expensive drugs with some well-known risks that require close monitoring and rigorous evaluation of the risks and benefits. The quality of health services provided by multidisciplinary teams is important to ensure patient’s safety and compliance to therapy. Subsequently, patients’ perceptions about their treatment is of outmost importance for the implementation of strategies that can improve various domains of care delivery [23–25], especially for patients with SRDs whose illness lasts a life time [26].

In this respect, the current study revealed significant degree of satisfaction among SRDs persons with the average level of satisfaction reaching the 79.8%. Although the literature is sparse in this area, similar results have been reported by Barbosa et al. [23] and Hill et al. [26], while low satisfaction rates have been demonstrated in Greek rheumatoid arthritis patients with suboptimal disease control on conventional and biologic disease modifying drugs [27]. Our study further expands these findings by recruiting patients receiving both intravenous and subcutaneous biologic regimens across the whole range of SRDs, in contrast to previous ones including individuals with inflammatory arthropathies. We do acknowledge that biologic drugs are prescribed “off-label” in several SRDs, such as SLE, SSc, and some types of systemic vasculitides; however, this is the first study of this kind across the whole spectrum of SRDs treated with targeted therapies.

Our study confirms previous observations establishing a positive correlation between satisfaction and perceived treatment effectiveness and that there is an interrelated relationship between biological medication and satisfaction with treatment [28, 29]. The great majority of participants (> 80%) declared on the one hand their satisfaction with the treatment and, on the other hand, the positive effect of the biological treatment in areas of their lives. Thus, it is not surprising that better quality of life was associated with greater satisfaction and more positive effect of the treatment on patients' life as described in the previous reports [10, 17, 30]. Given that increased satisfaction rates are directly associated with patients’ treatment adherence and continuation as well as overall outcomes of the disease, the results of the study underline the need for close monitoring of patients perceptive about their treatment [31].

Psychiatric disorders are emerging comorbidities in SRDs and convey an unfavorable impact on patients’ treatment perceptive as previous data suggest that depression has a predominantly negative effect on satisfaction rates in rheumatology setting [32, 33]. Depression is associated with worse disease outcomes and this association has been attributed—among others—to bidirectional effect between pain and mood disorders, whereby depression exacerbates pain and vice versa [34, 35].

Although our findings for greater satisfaction rates in patients with mental disease may look at the first glance fundamentally counterintuitive, similar findings have been published by the large international SENSE study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [36]. It can be speculated that beneficial treatment effect on pain may be associated with improved mental status as, in our study, patients with psychiatric disease reported higher levels of pain. Such findings highlight the increasing demand for multidisciplinary approach as the management of comorbidities in this population in parallel with immunosuppressive regimens may enhance treatment satisfaction and thus clinical outcomes [32].

Besides treatment outcomes, the current research demonstrated high level of satisfaction regarding the friendliness and attention of the staff such as nurses coupled by reasonable waiting time in the clinic. The results of many studies have shown the importance of interpersonal element of care delivery in patient satisfaction [37–40]. At the same time, waiting time is one of the main reasons for patient satisfaction or dissatisfaction—although they are generally tolerant of delays when visiting their doctor in clinic [23, 26, 40, 41]. In addition, a variety of opinions were recorded regarding the structure (e.g., patient rooms) and health facilities in line with the results reported by Clark et al. [42].

Finally, it is worth mentioning that this research was essentially carried out in pandemic conditions due to COVID-19, with all the barriers entailed by this fact (impossibility of transportation, difficulty in accessing the Hospitals where the research was conducted, difficulty in approaching patients, etc.). However, and even though the number of patients was lower than initially estimated, this is the only survey recruited SRDs’ individuals on biologics across the entire spectrum of rheumatic diseases.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations such as non-interventional design which precludes the establishment of temporal relationships. Lack of control group as well as selection, recall, and reporting bias are also associated with the type of the study as patients were asked to report on satisfaction regarding their treating physicians and other care-givers. For example, the majority of patients were on intravenous therapy as the distribution, completion, and collection of questionnaires took place mainly rheumatology departments of two Tertiary Hospitals where patients receiving intravenous drugs attend on regular basis. However, our study provides real-world data in a large number of patients treated with biologics from a wide spectrum of SRDs and also explores several aspects of patients’ satisfaction such as level and access to service including medical and nursing staff behavior and professionalism.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current survey showed that patients receiving biologic regimens in the modern treatment era of SRDs are generally satisfied by the outcomes of the treatment as well as by the quality of service and facilities providing by rheumatology departments participating in the study. In addition, we demonstrated high satisfaction rates across a wide spectrum of domains beyond disease activity, such as daily activities and quality of life. Taking into account patients’ perceptions and beliefs about effectiveness of antirheumatic treatment in parallel with physicians, medical and communication skills may result in better overall outcomes for individuals with SRDs and constitute a further step toward patient-centered care.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: CE, DK, TD, and CP. Data curation: CE and TD. Formal analysis: CE and TD. Funding acquisition: NA. Investigation: CE, DK, TD, and CP. Methodology: CE and TD. Software: N/A. Validation: N/A. Visualization: CE and TD. Writing—original draft: CE and TD. Writing—review and editing: DK, TD, and CP.

Funding

Authors did not receieved any funding for this work.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data of this study are available upon request.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Ethical approval

The approval of the competent scientific councils of the two hospitals was obtained before site initiation, according to the local legislation.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained for all participants before any study procedures.

Consent to publication

Yes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Christos Ermeidis, Email: ermidischr@gmail.com.

Theodoros Dimitroulas, Email: dimitroul@hotmail.com.

Chryssa Pourzitaki, Email: chpour@gmail.com.

Paraskevi V. Voulgari, Email: pvoulgar@uoi.gr

Dimitrios Kouvelas, Email: kouvelas@auth.gr.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National and state medical expenditures and lost earnings attributable to arthritis and other rheumatic conditions—United States, 2003. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep (MMWR) 2007;56:4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Da Silva JAP, Woolf AD. Rheumatology in practice. London: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrianakos A, Trontzas P, Chistoyannis F, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in Greece: a cross-sectional population based epidemiological study. The ESORDIG Study. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1589–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Dyke MM, Parker JC, Smarr KL, et al. Anxiety in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthrit Rheum. 2004;51:408–412. doi: 10.1002/art.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borman P, Toy GG, Babaoğlu S, et al. A comparative evaluation of quality of life and life satisfaction in patients with psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:330–334. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0298-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zartaloudi A, Koutelekos I. Anxiety and quality of life in patients with rheumatic diseases. Hellenic J Nurs. 2017;56:305–314. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2677-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christopoulou E (2020) Quality of life, anxiety and self-esteem in patients with rheumatic diseases. Dissertation, Hellenic Open University. https://apothesis.eap.gr/bistream/repo/47696/1/110771. Accessed 1 Oct 2022

- 8.Nam JL, Takase-Minegishi K, Ramiro S, et al. Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1113–1136. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramiro S, Sepriano A, Chatzidionysiou K, et al. Safety of synthetic and biological DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1101–1136. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotulska A, Kucharz E, Wiland P, et al. Satisfaction and discontent of Polish patients with biological therapy of rheumatic diseases: results of a multi-center questionnaire study. Reumatologia. 2018;56:140–148. doi: 10.5114/reum.2018.76901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayan G, Esatoglu SN, Hatemi G, et al. Rituximab for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies-associated vasculitis: experience of a single center and systematic review of non-randomized studies. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:607–622. doi: 10.1007/s00296-018-3928-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bounia CA, Liossis SC. B cell depletion treatment in resistant systemic sclerosis interstitial lung disease. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2022;33:1–6. doi: 10.31138/mjr.33.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cea-Calvo L, Raya E, Marras C, et al. The beliefs of rheumatoid arthritis patients in their subcutaneous biological drug: strengths and areas of concern. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:1735–1740. doi: 10.1007/s00296-018-4097-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furst DE, Tran M, Sullivan E, et al. Misalignment between physicians and patient satisfaction with psoriaticarthritis disease control. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:2045–2054. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3578-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azevedo S, Parente H, Guimarães F, et al. Differences and determinants of physician's and patient's perception in global assessment of rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed) 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang N, Yang P, Liu S, et al. Satisfaction of patients and physicians with treatments for rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based survey in China. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1037–1047. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S232578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González CM, Carmona L, De Toro J, et al. Perceptions of patients with rheumatic diseases on the impact on daily life and satisfaction with their medications: RHEU-LIFE, a survey to patients treated with subcutaneous biological products. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1243–1252. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S137052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Toro J, Cea-Calvo L, Battle E, et al. Perceptions of patients with rheumatic diseases treated with subcutaneous biologicals on their level of information: RHEU-LIFE Survey. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed) 2019;15:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatzitheodorou D, Kabitsis C, Papadopoulos NG, et al. Assessing disability in patients with rheumatic diseases: translation, reliability and validity testing of a Greek version of the Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) Rheumatol Int. 2008;28:1091–1097. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0583-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ginieri-Coccossis TE, Antonopoulou V, Christodoulou GN. Translation and crosscultural adaptation of WHOQOL-100 in Greece. Psychiatry Today. 2001;32:1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.HAQ (Health Assessment Questionnaire): Scaling and Scoring Version 4.0: July2011. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/resources/assets/docs/haq_instructions_508.pdf. Accessed 1 Feb 2022

- 22.Ramey DR, Fries JF, Singh G. The Health Assessment Questionnaire 1992: status and review. Arthritis Care. 1992;5:119–129. doi: 10.1002/art.1790050303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbosa L, Ramiro S, Roque R, et al. Patients’ satisfaction with the Rheumatology Day Care Unit. Acta Reumatol Port. 2011;36:377–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Campen C, Sixma HJ, Kerssens JJ, et al. Assessing patients’ priorities and perceptions of the quality of health care: the development of the quote rheumatic-patients instrument. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:362–368. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S, et al. Patients’ experiences and satisfaction with health care: results of a questionnaire study of specific aspects of care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2022;11:335–339. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.4.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill J, Bird HA, Hopkins R, et al. Survey of satisfaction with care in a rheumatology outpatient clinic. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:195–197. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sidiropoulos P, Bounas A, Galanopoulos N, et al. Treatment satisfaction, patient preferences, and the impact of suboptimal disease control in rheumatoid arthritis patients in Greece: analysis of the Greek Cohort of SENSE study. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2022;33:14–34. doi: 10.31138/mjr.33.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barton JL. Patient preferences and satisfaction in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with biologic therapy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2009;3:335–344. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, De Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Patient preferences for treatment: report from a randomised comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis (Be St trial) Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1227–1232. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.068296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Mits S, Lenaerts J, Cruyssen BV, et al. A nationwide survey on patient’s versus physician’s evaluation of biological therapy in rheumatoid arthritis in relation to disease activity and route of administration: the be-raise study. PLoS One. 2016 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murage MJ, Tongbram V, Feldman SR, et al. Medication adherence and persistence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1484–1503. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S167508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahlich J, schaede U, sruamsiri r. shared decision-making and patient satisfaction in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: a new «preference fit» framework for treatment assessment. Rheumatol Ther. 2019;6:269–283. doi: 10.1007/s40744-019-0156-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schafer M, Albrecht K, Kekow J, et al. Factors associated with treatment satisfaction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: data from the biological register RABBIT. RMD Open. 2020;6:3. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Husted JA, Tom BD, Farewell VT, et al. Longitudinal study of the bidirectional association between pain and depressive symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:758–765. doi: 10.1002/acr.21602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Euesden J, Matcham F, Hotopf M, et al. The relationship between mental health, disease severity and genetic risk for depression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Psychosom Med. 2017;79:638–645. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor PC, Ancuta C, Nagy O, et al. Treatment satisfaction, patient preferences, and the impact of suboptimal disease control in a large international rheumatoid arthritis cohort: SENSE study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:359–373. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S289692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cleary PD, McNeil BJ. Patient satisfaction as an indicator of quality care. Inquiry. 1998;25:25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mittal B, Lassar WM. The role of personalization in service encounters. J Retail. 1996;72:95–109. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(96)90007-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brady MK, Cronin JJ. Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: a hierarchical approach. J Market. 2001;65:34–49. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.65.3.34.18334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haslock I. Quality of care and patient satisfaction. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:382–384. doi: 10.1093/RHEUMATOLOGY/35.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.FoulkesaAC ,Chinoyb H, Warrena RB (2012) High degree of patient satisfaction and exceptional feedback in a specialist combined dermatology and rheumatology clinic. The University of Manchester Research. https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/38004954/FULL_TEXT.PDF. Accessed 15 July 2022

- 42.Clark P, Lavielle P, Duarte C. Patient ratings of care at a rheumatology out-patient unit. Arch Med Res. 2004;35:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

All data of this study are available upon request.