Highlights

-

•

HERs distinguish between self and other in emotions.

-

•

Neural sources in frontal operculum and visual cortices.

-

•

Physiological reactivity also encodes perspective.

-

•

HERs uniquely contribute to the valence ratings of one's own emotion.

Keywords: Heartbeat evoked responses, Emotion, Self/other distinction, Interoception, Electroencephalography, Empathy

Abstract

Feeling happy, or judging whether someone else is feeling happy are two distinct facets of emotions that nevertheless rely on similar physiological and neural activity. Differentiating between these two states, also called Self/Other distinction, is an essential aspect of empathy, but how exactly is it implemented? In non-emotional cognition, the transient neural response evoked at each heartbeat, or heartbeat evoked response (HER), indexes the self and signals Self/Other distinction. Here, using electroencephalography (n = 32), we probe whether HERs’ role in Self/Other distinction extends also to emotion – a domain where brain-body interactions are particularly relevant. We asked participants to rate independently validated affective scenes, reporting either their own emotion (Self) or the emotion expressed by people in the scene (Other). During the visual cue indicating to adopt the Self or Other perspective, before the affective scene, HERs distinguished between the two conditions, in visual cortices as well as in the right frontal operculum. Physiological reactivity (facial electromyogram, skin conductance, heart rate) during affective scene co-varied as expected with valence and arousal ratings, but also with the Self- or Other- perspective adopted. Finally, HERs contributed to the subjective experience of valence in the Self condition, in addition to and independently from physiological reactivity. We thus show that HERs represent a trans-domain marker of Self/Other distinction, here specifically contributing to experienced valence. We propose that HERs represent a form of evidence related to the ‘I’ part of the judgement ‘To which extent do I feel happy’. The ‘I’ related evidence would be combined with the affective evidence collected during affective scene presentation, accounting at least partly for the difference between feeling an emotion and identifying it in someone else.

1. Introduction

Emotions can be shared across individuals – both you and I feel happy – or individualized – I feel sad while you appear to be afraid. Experiencing an emotion from a first person perspective, and observing emotions in others, share substantial physiological and neural similarities (Lee and Siegle, 2012; Ochsner et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2016). Still, under normal circumstances we do not ‘lose’ our sense of self. We are able to attribute which emotion belongs to us, and which emotion belongs to the person we observe – with a noticeable difference in the felt quality of the emotion, depending on whether the emotion is directly experienced or observed. The Self/Other distinction is recognized as an essential component in most empathy models to prevent emotional contagion and personal distress (Singer and Lamm, 2009), but surprisingly few studies directly investigated the Self/Other distinction in emotional feelings (e.g. Ochsner et al. 2004). The current consensus is based on contrasts between different studies (Lee and Siegle, 2012) or inferences from the pain literature (Lamm et al., 2016). How is Self/Other distinction in emotions implemented? Why do experienced emotions feel different from observed emotions?

Recently, a mechanism for self-specification and Self/Other distinction has been proposed in perception and cognition, based on the monitoring of cardiac signals (Azzalini et al., 2019). At each heartbeat, the brain transiently generates a neural response, also known as the heartbeat evoked response (HER) (Schandry et al., 1986). HERs change when bodily state changes, as during affective processing (for references see next paragraph). However, HERs also vary with cognitive parameters in the absence of bodily changes, for instance when paying attention to one's own heartbeats (Montoya et al., 1993; Petzschner et al., 2019). HERs have consistently been found to index the self (Babo-Rebelo et al., 2016, 2016; Park et al., 2016; Sel et al., 2017) and to label Self/Other distinction (Babo-Rebelo et al., 2019) in non-emotional paradigms. Here, we probe whether the same mechanism is at play for distinguishing between emotional feelings in oneself from those inferred in someone else– in other words, we probe whether HERs could index a general mechanism of Self/Other distinction, valid across perception, cognition and emotion. Indeed, while reciprocal influences between emotion and cognition have long been acknowledged, common building blocks across domains remain scarce – for instance, evidence accumulation, a central mechanism in perception and cognition, is only beginning to be acknowledged in the emotion literature (e.g. Givon et al. 2019, Grèzes et al. 2021, Mennella et al. 2020, Pichon et al. 2021, Roberts and Hutcherson 2019, Tipples 2018, Yang et al. 2020).

HERs, the potentially trans-domain mechanism we probe here, pertains to brain-body relationships. Bodily changes are constitutive of the very definition of emotions, which comprises a behavioural sequence, physiological reactivity and a subjective affective feeling (Barrett et al., 2007). HER amplitude changes during emotion recognition or experience (Couto et al., 2015; Di Bernardi Luft and Bhattacharya, 2015; Fukushima et al., 2011; Gentsch et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; MacKinnon et al., 2013; Marshall et al., 2017, 2018, 2020), which has been attributed to coinciding bodily changes. However cardiac parameters have only limited influence on HERs (Buot et al., 2021). Besides, HERs are involved in non-emotional paradigms such as perception at threshold, i.e. the non-emotional subjective feeling of whether a weak stimulus is present or not (Al et al., 2020; Park et al., 2014). HERs could thus constitute a landmark for subjective feelings, whether emotional or not, and reflect a form of evidence related to the “I” part (Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014) of the report “I feel happy” as well as of the report “I feel I have seen something”. The role of HERs is thus potentially distinct from the emotion-related physiological reactivity.

We tackled the issue of Self/Other distinction in emotional feelings in a paradigm where participants were presented affective social scenes, which they had to rate either according to the emotional experience they felt (Self condition), or the emotion expressed by people in the scene (Other condition) (Fig. 1A). At the beginning of each trial, a cue indicated the Self or Other condition. During cue, the only task of the participant was to actively prepare for either the Self or Other perspective; no affective information was being presented yet. The paradigm thus creates a time-window where perspective taking was isolated from affective reaction. Participants were then presented with an affective scene they could explore for five seconds, in the Self or Other perspective. Finally, participants rated either their own valence and arousal (Self condition), or the valence and arousal of the person(s) in the affective scene (Other). We measured the electroencephalogram (EEG), as well as the electrocardiogram (ECG), facial electromyogram (fEMG), and skin conductance response (SCR) during task, as well as the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) questionnaire (Davis, 1983), since individual differences in dispositional empathy might influence the difference between Self and Other conditions.

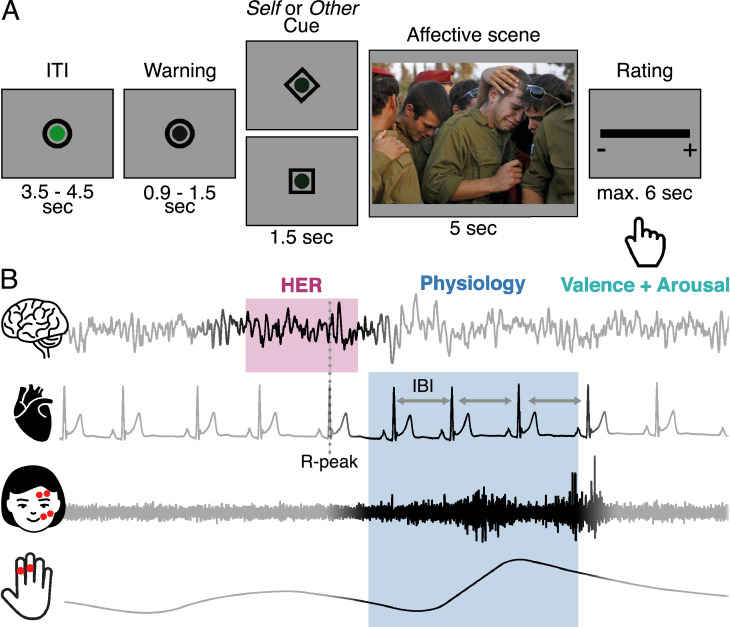

Fig. 1.

Experimental paradigm. (A) Time course of a trial. At each trial participants were shown a symbolic cue instructing them to rate the upcoming affective scene for either their own emotion (Self condition), or the emotion of the person(s) in the image (Other condition). After stimulus presentation, participants rated valence and arousal on two successively presented continuous scales (only one displayed, order counterbalanced between participants). (B) Data acquired and rationale for data analysis. We recorded the electroencephalogram (EEG), the electrocardiogram (ECG), facial electromyogram (fEMG) of the zygomatic and corrugator muscles and skin conductance phasic response (SCR), as well as participants’ ratings. We analysed Heartbeats Evoked Responses (HERs) during cue, physiological responses (Interbeat Interval, IBI, fEMG and SCR) during affective scene presentation, and valence and arousal ratings provided by the participant at the end of each trial, on two successive scales. EEG was corrupted with saccades during stimulus presentation, during which participants were free to explore the visual scene, analysis of HERs was restricted to the time window before the onset of the images.

The rationale for data analysis was organized as follows. First, based on previous literature on HERs in Self and Self/Other distinction (Babo-Rebelo et al., 2019; Babo-Rebelo et al., 2016; Park et al., 2016; Sel et al., 2017), we hypothesized that HERs would dissociate between the Self and Other condition during the cue, where participants prepared to adopt the Self or Other perspective, but before affective scene presentation. Second, during affective scene presentation, we verified that we observed the expected relationship between subjective ratings and physiological measures (fEMG, heart rate, SCR), and explored whether this relationship was modulated by the Self or Other perspective adopted. Finally, we targeted the qualitative difference between rating one's own emotion vs. someone else's emotion. Indeed, feeling happy, or seeing someone with a joyful facial expression, corresponds to different subjective experiences, even when ratings are numerically identical. We hypothesized that HERs might contribute differently to rating one's own emotion and to rating someone else's emotion. To test this hypothesis, we modelled the unique contributions of HERs before scene onset and physiological variability during affective scene to subjective ratings of valence and arousal. We could thus probe whether ratings for Self and ratings for Other are based on the same, or distinct, neural and bodily markers.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

34 right-handed participants with normal or corrected-to-normal vision completed the experiment after providing written informed consent. The sample size was chosen to be comparable to or larger than previous MEEG studies investigating the link between HERs and self-consciousness (Babo-Rebelo et al., 2019; Babo-Rebelo et al., 2016; Park et al., 2016; Sel et al., 2017). The ethics committee CPP Ile-de France III and INSERM approved all experimental procedures (protocol number C15–98). Participants received monetary compensation after the experiment. Two participants were excluded from data analysis: one for responding at chance level in catch trials, and another had a too high resting heart rate to ensure a sufficient number of trials (see trial selection). 32 participants were included in the final analysis (15 male, mean age (SD) = 24.72(4.89)).

2.2. Stimuli

2.2.1. Databases

Stimuli were naturalistic images selected, with permission, from EmoMadrid (http://www.uam.es/CEACO/EmoMadrid.htm), EmoPicS (Wessa et al., 2010), GAPED (Dan-Glauser and Scherer, 2011), IAPS (Lang et al., 2008) NAPS (Marchewka et al., 2014), and OASIS (Kurdi et al., 2017). Images depicted humans, with averted gaze, who were either alone or in a group (with congruent emotion expression). Expressed emotions were sadness in the negative valence range, or happiness in the positive valence range. As the majority of the selected images were either of neutral or positive valence, additional sad images were selected from websites offering license free images such as flickr.com, Wikimedia commons and pexels.com. As the 442 selected images stemmed from different databases, where typically only rated for Self or for Other are provided, or were not yet validated, we ran a separate ratings experiment.

2.2.2. Stimulus ratings for self and other in 210 participants

We obtained Self and Other ratings for each of the 442 images. A total of 210 participants were tested (101 participants (mean age (SD) = 27.6(88), 54 female, 90 right-handed, 9 left-handed and 2 ambi-dexterous) for the Self condition and 97 participants (mean age (SD) = 26.9(8.8), 50 female, 91 right handed, 5 left handed, 1 ambi-dexterous) for the Other condition). 11 participants were excluded from further analysis because they had missed more than 20 responses, and one participant was excluded because of incorrect use of the rating scale. All participants signed an informed consent and were paid for their participation.

All images were divided into subsets and rated by groups of participants (max. group size 20). Each image was projected on a large screen for four seconds, after which participants provided their continuous ratings of valence and arousal on a smartphone using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Each participant rated 176 or 177 images (depending on stimulus set). The number of ratings obtained per image (after outlier removal) was between 33 and 46, and the percentage of male ratings per image lied between 40 and 49%. For each image, an average valence and arousal rating and standard deviations of the ratings were calculated. Highly ambiguous images were excluded from further stimulus selection (mean ± 3SDs for one of four rating conditions (valence/arousal for Self/Other), nine images excluded). 433 images were available to build the final stimulus sets used for the experiment.

2.2.3. Stimulus sets for the EEG experiment

We wanted to match the naturalistic images used on several dimensions to avoid large differences in image content and properties between the Self and Other conditions. Images were matched on the following criteria: mean and SD of valence and arousal ratings, mean and SD of image luminance, and information about the person(s) depicted in the image (gender and skin colour).

The procedure for determining the sets of images ran as follows. All available images were split into six bins based on the valence rating in the Self condition. In a first round, 15 images were randomly drawn from each of these bins, and the draw was accepted if within-bin mean image properties were similar across the six bins of Self ratings, i.e. that across the six bins, images were matched within a difference of max. 25% from each other based on how ambiguous they were (standard deviations of valence and arousal), how arousing they were (mean of arousal rating), or their physical properties (mean and standard deviation of luminance), and the content of the images (average amount of females, males, white people, and people of colour depicted in each of the bins). We thus obtained a set of 90 images for the Self condition. To select the 90 images presented in the Other condition, the exact same procedure as described for the Self stimulus set was repeated on the remaining images. Once a stimulus set had been found for each of the conditions, they were compared against one another. This was again done in two stages. First, we compared the two conditions bin by bin to verify they match for mean and standard deviation of valence, arousal, and luminance. We considered the two conditions to be matched on valence, arousal and luminance if they differed by less than 25%. Secondly, for social parameters (amount of females, males, white people, and people of colour), we considered the two conditions to be matched if they differed by less than 35%. If at any point in the procedure one of the criteria was not met, a new draw was initiated, until a stimulus set of 180 images (90 images for Self and 90 images for Other) was obtained. A total of four stimulus sets were obtained this way, the use of which was counterbalanced between participants. For each set, the 180 images were split into six blocks of 30 images, with the distribution of valence ratings roughly matched across blocks. An overview of the characteristics of the different stimulus sets is available in the supplementary material.

2.3. Task

Participants were asked to rate either their own emotion (Self condition), or the emotion of the person(s) in an image (Other condition), as indicated by a symbolic cue at the beginning of each trial (Fig. 1A). Abstract visual cues were used to ensure no visual differences between the two conditions. The start of each trial was indicated by a change of the inner fixation dot in the centre of the screen (warning cue, 0.9–1.5 s). A symbolic cue (square/diamond, meaning counterbalanced between participant) was then presented (1.5 s), indicating the trial condition (Self/Other). The affective scene was presented, during which the participant was free to visually explore the scene. After four seconds, the fixation dot was superimposed on the stimulus and the participant had to bring their eyes back to fixation. After stimulus presentation, the participant rated successively the valence and the arousal (order counterbalanced between participants) of the affective scene on a continuous scale (recorded as values between 0 and 200) using a key pad and in accordance with the trial condition (Self/Other). Maximal response time was six seconds. The inter-trial interval varied between 3.5–4.5 s. Participants completed six blocks of the task, each block consisting of 30 (pre-assigned) stimuli, 15 rated for Self, 15 rated for Other, presented in a random order. To verify whether participants were attentive to the meaning of the condition cue, occasional catch trials (one or two per block, randomized) were used, where participants immediately after rating scale offset had to indicate the condition of the preceding trial (mean accuracy ± SD = 0.94 ± 0.08).

The task was presented with Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA, United States) using the Psychtoolbox (Brainard, 1997) on a 1920×1080 pixels screen, with a 70 cm average viewing distance. The maximal length or width of the images was restricted to 380 pixels, corresponding to a maximal visual angle of 12°.

2.4. Experimental procedure

After task instructions, participants performed a practice task, in which they were acquainted with the symbols by first performing five trials in the Self condition, followed by five trials in the Other condition, without constraints on rating time. This was followed by 10 trials in which the conditions pseudo-randomly alternated, and lastly by 10 trials of mixed conditions with restricted time to respond, similar as in the actual task. The images used for the practice were selected from the pool of images left after stimulus set selection, and were drawn from three valence bins to fully prepare participants for the types of images they would be exposed to. Once the participant indicated to fully understand the tas, the electrophysiological recordings were prepared; setting-up of the EEG cap, EOG, fEMG, SCR, and ECG (see physiological and EEG recordings). Once appropriate impedance and signal quality had been reached for each measure, the main task began. Each block of the task started with eyetracker calibration, followed by 30 consecutive trials of the task. After the task, participants were asked to perform a short, previously unannounced, memory task of the images, during which they indicated whether they had seen an image during the task or not (see self reference effect task). During this task, no physiological or EEG signals were recorded. Lastly, participants were asked to complete several questionnaires (see questionnaires).

2.5. Physiological and EEG recordings

Recordings were performed in an electrically shielded room using the Biosemi ActiveTwo recording system (Biosemi, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) with a sampling rate of 2048 Hz, a DC–400 Hz bandwidth, and the Actiview software. EEG data was recorded using 64 pin-type active electrodes mounted in a flexible headcap with CMS and DRL placed left and right from POz respectively. For the physiological recordings, flat type active electrodes were used. The ECG was recorded using five electrodes, two of which were placed on the left and right clavicles, two on the upper left and right shoulders, and an additional electrode used for offline re-referencing placed on the left lower abdomen. fEMG of the corrugator supercilii was recorded by placing one electrode above the brow, in line with the inner corner of the eye, and one electrode one centimetre lateral and superior to the first electrode. Activity of the zygomaticus major was recorded by placing one electrode in the centre of the midline between the corner of the mouth and the preauricular depression, and a second electrode one centimetre inferior and lateral towards the mouth (Fridlund and Cacioppo, 1986). Both muscles were recorded from the right side for practical reasons. The vertical Electro-oculogram (EOG) was recorded by placing one electrode above the brow, and one below the eye on the left side. Finally, the skin conductance response (SCR) was measured by placing two passive Nihon Kohden electrodes on the middle phalanx of the index and middle finger respectively, and passing a constant current through them (16 Hz at 1 μA, synchronized to the sampling frequency). Eye position was tracked using an Eyelink 1000 system (SR Research, Canada), using a monocular recording of the right eye, with a 35 mm lens at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz.

2.6. Questionnaires

Participants completed questionnaires to potentially exclude outliers on depression (Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al., 1961), anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger et al., 1983), alexithymia (Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) (Bagby et al., 1994), and interoception (Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness version (MAIA)). No participant fell outside the mean ± 3SDs.

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) (Davis, 1983) was acquired to test for any correlation between measures indicating Self/Other distinction and different facets of dispositional empathy (empathic concern, perspective taking, and personal distress). Previous work has shown that scores on empathic concern positively correlates with the amplitude of the HER in both an emotion recognition and a perceptual task (Fukushima et al., 2011).

2.7. Self-reference effect task

Typically, when information is related to the self, it can lead to more efficient processing evident in for example memory performance or perception, the so-called self-reference effect (for review see Sui and Humphreys 2015). To test for any self-reference effect in our task, participants completed an unannounced memory task at the end of the experiment. Participants were presented with all images from the task (180), plus an additional 60 new images. Participants self-paced through all images indicating whether or not they had seen them before. New images for this task were selected out of the remaining unused images that were neither present in the task nor the practice, divided into two bins (positive and negative valence), after which 30 images were randomly selected out of each bin. Note that another related effect, the emotional egocentricity bias, could have been measured; this effect refers to how one interprets the emotion of someone else given one's own current emotional state (Silani et al., 2013; Trilla et al., 2021; Von Mohr, Finotti, Ambroziak, and Tsakiris, 2020).

2.8. Data pre-processing

Offline pre-processing and analysis of physiological and neural signals was done using the Fieldtrip toolbox implemented in Matlab (Oostenveld et al., 2011) and additional custom-built Matlab code.

2.8.1. EEG pre-processing

Continuous EEG data was band-pass filtered between 0.5–45 Hz using a fourth order zero-phase forward and reverse Butterworth filter, and for each channel the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Channels exceeding ±3SDs of the mean AUC of all channels were repaired using a weighted average of the (unfiltered) neighbouring channels. Next, the data was re-referenced to a common average of all channels. Epochs contaminated by large movement or muscle artefacts were detected as segments exceeding a threshold of three standard deviations from the mean on band-pass filtered (110–140 Hz, fourth order zero-phase forward and reverse Butterworth filter), Hilbert transformed, and z-scored data.

Independent Component Analysis (ICA) implemented in the Fieldtrip Toolbox was used to attenuate artefacts in the data resulting from blinks and cardiac events, as described in Buot et al. (2021). For the blink correction, the re-referenced EEG and EOG data were band-pass filtered between 0.5–45 Hz using a fourth order zero-phase shift forward and reverse Butterworth filter, and epoched into ten second segments (excluding segments contaminated by artefacts). Data was then decomposed into independent components using the ft_componentanalysis fieldtrip function. Next, pairwise phase consistency (PPC) was computed between the frequency decompositions of the ICA components and the EOG data. Up to three components were iteratively removed if they exceeded more than three standard deviations from the mean PPC. For cardiac artefact correction, blink-corrected EEG and ECG data were band-pass filtered between 0.5–45 Hz using a 4th order zero-phase shift forward and reverse Butterworth filter, and epoched in [−200 to +200 ms] segments centred on the R-peaks. Artefact-free EEG data segments were then decomposed into independent components using the ft_componentanalysis fieldtrip function. PPC was computed between each independent component and the ECG signal in the 0–25 Hz range. Components that exceeded more than three standard deviations from the mean PPC were rejected. Depending on participants, between one and three components were removed from the EEG data using the ft_rejectcomponent function. For all further reported analyses, the ICA-corrected EEG data was band-pass filtered between 0.3–20 Hz using a 4th order zero-phase shift forward and reverse Butterworth filter, unless explicitly stated otherwise. As EEG was corrupted with saccades during stimulus presentation, during which participants were free to explore the visual scene, analysis of HERs was restricted to the time window before image onset.

2.8.2. Physiological data pre-processing

We first computed bipolar derivations between each of the four ECG electrodes with the left abdominal electrodes, and generated also four horizontal derivations by computing the difference between the four ECG electrodes placed around the neck. We detected R-peaks on the ECG lead II obtained by re-referencing the lower left abdomen with the right clavicle. The re-referenced data was band-pass filtered between 1 and 40 Hz (windowed-sinc FIR filter), except for five participants where initially noisy data were band-passed between 1 and 20 Hz. For each block, a template cardiac cycle was computed and convolved with the entire ECG time series. R-peaks were detected on the normalized (between 0 and 1) resulting convolution, as exceeding a threshold of 0.6. Interbeat intervals were calculated on the lead II derivation as the time distance between two subsequent detected R-peaks. fEMG data was offline re-referenced and band-pass filtered between 20 and 500 Hz (fourth order zero-phase forward and reverse Butterworth filter). Subsequently, the data was Hilbert transformed, low-pass filtered at 5 Hz to smooth the data, and cut into trials, after which the data was z-transformed (using the mean and standard deviation of the concatenated trial data). Each trial was baseline-corrected by subtracting the mean of 900 ms before cue onset.

SCR data was converted from nano- to microSiemens and preprocessed using the Ledalab toolbox v. 3.4.9 (www.ledalab.de) using the Continuous Decomposition Analysis (Benedek and Kaernbach, 2010). Continous data was z-scored and downsampled to 32 Hz before the phasic driver component of the SC was extracted.

2.9. Trial selection and heartbeat evoked response computation

After pre-processing, trials suitable to be included in the HER analysis were selected in the following manner. First, for each trial, we selected R peaks which occurred at least 225 ms after cue onset (to avoid contamination by the transient response to the cue), and at least 600 ms before affective scene presentation, so that the evoked response to the heartbeat can be measured without any overlapping response evoked by the affective scene. If multiple R-peaks were identified within this window of interest, only the R-peak closest to image onset was included in the analysis. Trials were only included if the selected R-peak had a minimal distance of 570 ms to the subsequent R-peak. The time-window to analyse HERs was from 270 ms post R-peak (after the end of the T-wave) to 570 ms post R peak (minimal distance to the next R peak). Trials were furthermore only included if no muscle noise was present during the entire cue window, and the participant had provided behavioural responses on both the valence and arousal scales. HERs were then computed for the Self and Other conditions for each participant, by making an R peak time-locked average using all trials that were selected as suitable for analysis. We initially acquired 90 trials in the Self condition and 90 trials in the Other condition. After artefact rejection, an average of 63.38 (SD = 10.49) trials remained in the Self condition, and an average of 65.25 (SD = 9.20) in the Other condition. Those two numbers did not differ significantly t(31) = −1.64, p = 0.11).

2.10. Source-level analysis

We reconstructed sources of the HERs during the significant Self/Other time window (426–436 ms after the R-peak). Source reconstruction was performed using the Brainstorm toolbox (brainstorm3, (Tadel et al., 2011)). For each participant the grand average electrode data for the Self and Other conditions were loaded. Then, for source analyses, a default anatomy (ICBM152) was used together with the Biosemi 64 10–10 layout. A 3-shell sphere was created for each participant, using no noise modelling, and sources were computed using default parameters (minimum norm imaging, current density map measure, constrained normal to cortex source model, depth weighting order 0.5 with maximal amount 10, noise covariance regularization of 0.1, regularization parameter signal-to-noise ratio of 3 and output mode inverse kernel only). Averages of the source models were then computed separately for the Self and Other conditions within the time window of interest (426–436 after the R-peak), and compared with a t-test. Scouts were created at an alpha level of 0.005 (uncorrected) and a minimum cluster size of 13.

2.11. Statistical analysis of physiological and EEG data

2.11.1. General

To quantify the level of evidence in support or against the null-hypothesis, we calculated the Bayes Factor (BF). The BF10 was calculated in Matlab based on formulas provided by Liang et al. (2008). In short, a Bayes Factor of 1 indicates equal support for H0 and H1, whereas values higher than 3 indicate support for H1 with values exceeding 10 providing strong evidence. Values smaller than 0.33 indicate moderate support for H0, with values smaller than 0.1 providing strong evidence for H0. Unless otherwise specified, all reported t-tests are two-sided.

To compare time-series (HERs in the Self and Other conditions, parameter estimates of general linear models against zero), we used the cluster-based permutation approach (Maris and Oostenveld, 2007) implemented in the Fieldtrip toolbox, which intrinsically corrects for multiple comparisons over time and electrodes. Briefly, two-tailed paired t-tests are used to compare each sample at each electrode between the two conditions. Candidate clusters are defined adjacent points in time and space exceeding a set statistical threshold and a given number of neighbouring electrodes. The statistical significance of the sum(t) observed in candidate clusters is determined using the Monte Carlo method. Condition labels are randomized 1000 times, and for each randomization the largest (resp. smallest) sum(t) of the observed clusters is used to generate the distribution of largest (resp. smallest) sum(t) under the null hypothesis. The Monte Carlo p value corresponds to the proportion of cluster statistics under the null distribution that exceed the original cluster-level test statistics. Because this method considers the largest and smallest sum(t), it intrinsically corrects for multiple comparisons across time samples and electrodes.

2.11.2. Comparison of HERs in the self and other conditions

To test for significance of the difference between the Self and Other condition in the HER, cluster-based permutations were run on the time-window of 270 to 570 milliseconds after the selected R-peak in the condition cue window, using the clustering procedure with a first level alpha of 0.01 and 3 neighbouring electrodes. HERs during image presentation were not analysed as this time period was contaminated by eye movements.

2.11.3. Permuted heartbeats analysis

Permuted heartbeats were used to determine whether effects observed in the HER were truly locked to the heartbeat and not caused by an overall difference between Self and Other conditions present during the cue window. For each participant, the original timings of the R-peaks used in the HER analysis with respect to the onset of the cue were reassigned randomly, such that the R-peak timing of trial i was reassigned to trial j. The same cluster-based permutation procedure was applied and the sum(t) value of the largest negative candidate cluster extracted. If no negative cluster was identified in the permuted data, a cluster value of 0 was assigned to the permutation. The whole procedure (R-peak timing re-assignment and sum(t) extraction) was repeated 100 times per participant. Finally, the cluster statistics of the observed negative cluster in the original HER analysis was compared to the distribution of permuted cluster statistics to derive the Monte-Carlo p.

2.11.4. Statistical modelling of skin conductance and facial EMG

To quantify the effect of Self/Other condition, valence, and arousal on physiological activity, we modelled each physiological time series (the trial-by-trial phasic driver skin conductance activity, trial-by-trial corrugator supercilii activity and trial-by-trial zygomatic major activity) for each participant separately with a general linear model (GLM) at each time point t, in the following manner:

where t represents time. β0(t) is the intercept, βcondition(t) represents the estimated contribution of the Self/Other condition (+1 −1), βvalence(t) and βarousal(t) are the estimated contribution of the z-scored valence and arousal ratings given by the participant, and βcondition*valence(t) and βcondition*arousal(t) are the estimated contribution of the interactions, obtained by multiplying the z-scored ratings with the condition predictor. Note that we do not split the data into “happy” and “sad” but use all ratings on the continuous valence scale. A separate model was run for each of the three physiological measures. The significance of each parameter estimate was estimated by testing the beta time series against zero, across participants. Significance was tested between 1 and 5 s after stimulus onset, using the clustering procedure with a two-tailed dependent samples t-test, a first level alpha of 0.05, and using 500 randomizations.

2.11.5. Interbeat interval analysis

To investigate changes in heart rate as a result of the task manipulations, for each participant the IBI was calculated for the following time points: IBI occurring around image onset (ImOn), and the subsequently four following IBIs (Im+1, Im+2, Im+3 and Im+4).

To quantify the effect of Self/Other condition, valence, and arousal on the IBI, we modelled the trial-by-trial changes in IBI for the five timepoints (ImOn, Im+1, Im+2, Im+3, Im+4) with a general linear model (GLM), identical to the one used for SCR and fEMG but with only five time points:

The 5-point betas resulting from each regressor were entered into a repeated-measures ANOVA with the factor time, to test for general changes in IBI during the image viewing. To test for any significant deviations from zero, a t-test was performed against zero at each time point and FDR corrected for time, separately for each regressor.

2.12. Modelling of valence and arousal ratings

We tested whether correlates of Self/Other distinction in the HER and in the SCR uniquely contribute to ratings of arousal and valence, in addition to the expected contribution of the physiological markers of emotion. Hence, separately in the Self and Other conditions, we modelled the trial-by-trial fluctuations of ratings of valence and arousal of each participant in the following way:

where Zygo (resp. Corr) corresponds to zygomatic (resp. corrugator) activity averaged in the time-window 1–5 s after image onset, IBIIm4 is the 4th IBI after image onset and co-varies with Valence ratings, and SCRSelf/Other (resp. HERSelf/Other) the mean SCR activity (resp. HER) in the time-window where it differs between Self and Other. We did not enter the perspective effect in facial muscle activity as it overlapped in time with the valence effect, that persisted throughout the entire window of interest (1–5 s).

Following the same logic, we modelled ratings of arousal as described below:

where Zygo (resp. Corr) corresponds to zygomatic (resp. corrugator) activity averaged in the time-window 1–5 s after image onset, SCRAr the mean SCR activity in the early time window where it covaries with arousal, and SCRSelf/Other (resp. HERSelf/Other) the mean SCR activity (resp. HER) in the time-window where it differs between Self and Other.

The models were ran separately for the Self and Other condition, and independently z-scored within each condition. To test for significance, the extracted beta values of each regressor were tested against zero using a two-tailed paired t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioural results

3.1.1. Valence and arousal ratings

We tested for any systematic differences between Self and Other trials in either mean or variance of valence and arousal ratings. Self trials were slightly but consistently judged as less pleasant than Other trials (mean Self valence ± SD = 96.45 ± 6.20, Other valence = 99.71 ± 6.73, t(31) = −3.25, p = 0.003, BF10 = 13.34), with similar variances (mean variance of Self valence ± SD = 46.75 ± 11.44, variance of Other valence = 48.86 ± 9.39, t(31) = −1.59, p = 0.120, BF10 = 0.58). Arousal ratings were similar for Self and Other (mean Self arousal ± SD = 100.52 ± 12.40, Other arousal = 100.73 ± 13.37), t(31) = −1.08, p = 0.290, BF10 = 0.32), but the variance of arousal ratings was larger in the Other vs. Self-condition (mean variance of Self arousal ratings ± SD = 37.61 ± 13.91, variance of Other arousal = 45.23 ± 13.28, t(31) = −4.20, p < 0.001, BF10 = 131.91).

Altogether, these small but robust differences in the mean of valence ratings and in the variance of arousal ratings indicate that participants complied with instructions and distinguished between the Self and Other conditions.

3.1.2. Self reference effect

After completion of the main task, participants performed a memory task, to test whether they would remember the images previously rated for either Self or Other differently. However condition influenced neither accuracy (mean accuracy Self ± SD = 0.89 ± 0.09, mean accuracy other ± SD = 0.89 ± 0.09, t(31) < 0.01, p = 1, BF10 = 0.19) nor reaction time (mean RT Self ± SD = 1.16 ± 0.25 s, mean RT Other ± SD = 1.17 ± 0.19 s, t(31) = −0.71, p = 0.48, BF10 = 0.24).

3.2. Heartbeat evoked responses during cue distinguish between self and other

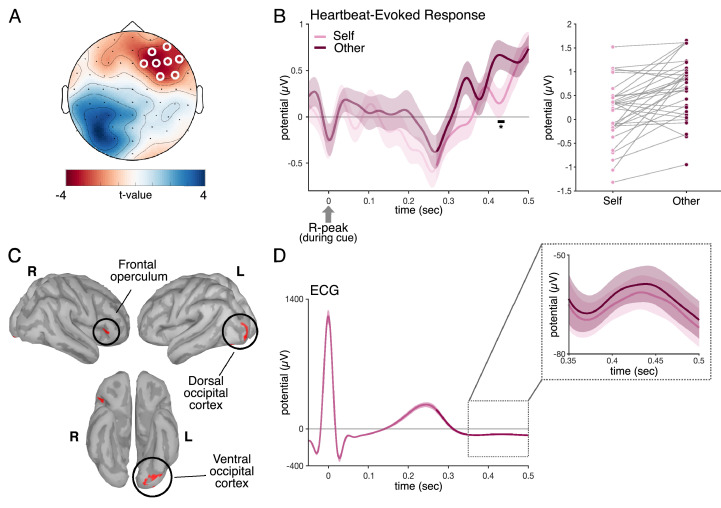

Our first central prediction was that there should be a significant difference in the amplitude of the HER between actively preparing to adopt the Self or Other perspective, prior to the onset of the affective scene. Our results confirmed the predicted difference between the two conditions (Fig. 2A, 2B), which occurred between 426 and 436 ms after the R-peak (cluster sum(t) = −498.576, Monte-Carlo p = 0.045) and was located in a right frontal cluster (eight electrodes in cluster: AF8, AF4, F2, F4, F6, F8, FC6, and FC4). The anatomical regions with the largest contribution to this difference (Fig. 2C) were located in the right frontal operculum (MNI(x,y,z) = 43, 23, 2), as well as in occipital regions (left dorsal occipital MNI(x,y,z) = −30, −101, −5; ventral occipital (MNI(x,y,z) = −39, −81, −14, MNI(x,y,z) = −22, −84, −16, MNI(x,y,z) = −20, −94, −20).

Fig. 2.

HERs during cue distinguish between Self and Other condition. (A) Topography of the cluster during which there was a significant HER difference between Self/Other condition, in the time window between 426 and 436 ms after R-peak during the cue window. (B) Timeseries of the HER in the Self and Other condition, averaged across electrodes depicted in (A) and across participants. Right panel shows individual averages for the Self and Other condition within the significant time window. (C) Brain regions mostly contributing to the Self/Other difference in the HER were localized to the frontal operculum, and dorsal and ventral occipital cortex (threshold at uncorrected p < 0.005 in a minimum of 13 adjacent vertices). (D) Time series of the Self/Other difference in the ECG. This control analysis revealed no significant differences in the ECG signal between the two conditions. Shaded areas represent the standard error of the mean.

We further controlled that the Self/Other difference in HER was not due to a Self/Other difference in heart rate or in electrocardiogram. We computed the interbeat interval between the heartbeat used to compute HER and the following one, but found no difference between Self and Other (mean IBI ± SD, Self: 0.85 ± 0.10 s, Other 0.84 ± 0.10 s, paired t-test t(31) = 0.6, p = 0.55, BF10 = 0.22, indicating moderate evidence for the null hypothesis). We also compared the ECG corresponding to the heartbeats used to compute HERs (Fig. 2D), but none of the eight ECG derivations showed any difference (no candidate cluster present in any of the derivations). Since neither heart rate nor ECG differ between Self and Other but HERs do, we can conclude that the HER difference between Self and Other is of neural origin rather than reflecting a difference in cardiac input (Buot et al., 2021). Finally, using a permuted heartbeat analysis we verified that the difference was truly locked to heartbeats (Monte Carlo p = 0.02).

Last, any Self/Other difference might be related to difference in dispositional empathy. In an exploratory analysis, we tested whether the Self/Other difference in the HER, averaged over time and electrodes, is related to sub-scores of dispositional empathy as measured in the IRI questionnaire, but found no significant link (robust correlation between the HER effect and the scores of perspective taking, empathic concern and personal distress, all r2 < 0.01, all pFDR > 0.87, FDR corrected for the three subscales).

3.3. Skin conductance response and facial EMG distinguish between self and other during scene presentation

We then probed whether physiological measures were also sensitive to perspective during image viewing. Indeed, while changes in physiological measures accompanying the presentation of affective images is well established (Bradley et al., 2001), whether physiological reactivity depends on the perspective from which the image is evaluated is not yet known. We analysed the time course of each of the measured physiological variables (skin conductance response, zygomatic activity, corrugator activity, and interbeat interval) in separate GLMs, to determine whether and when the categorical regressor Self/Other condition, the parametrical regressors valence rating and arousal rating, as well as interactions between condition and ratings account for physiological reactivity. As detailed below, we found that in addition to the expected co-fluctuations with valence and arousal ratings, the Self or Other perspective adopted was reflected in SCR, as well as in zygomatic, and corrugator activity.

3.3.1. Arousal ratings and self/other condition independently account for SCR fluctuations

As expected from the literature (Lang et al., 1993), we found that SCR scaled with arousal (Fig. 3A, Table 1), in a time-window centred around 3 s after stimulus onset. However, we additionally found that the SCR was sensitive to the Self vs. Other condition, in a later time window. The SCR displayed no interactions between the condition and either the valence or arousal rating of the participant (all candidate clusters Monte Carlo p > 0.188).

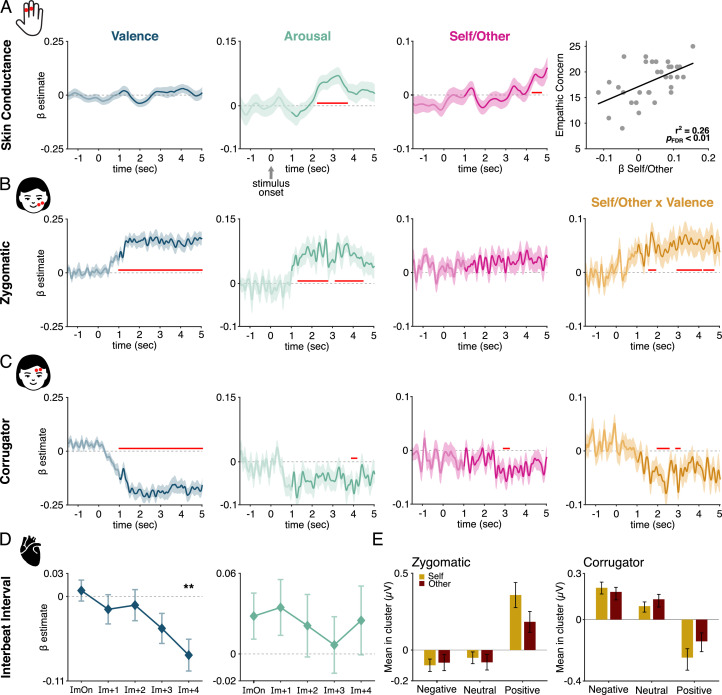

Fig. 3.

Modelling of trial-by-trial fluctuations in physiological reactivity with valence ratings, arousal ratings, Self/Other condition and interactions. (A) Skin conductance response. The first three panels show the time-course of the estimated model parameters (beta) for valence, arousal and Self/Other condition. Solid lines represent grand-average across participants and shaded areas correspond to standard error of the mean. Time-windows where those parameters significantly differed from zero are indicated in red (cluster-based permutation procedure correcting for multiple comparisons over time, Monte-Carlo p < 0.05). SCR fluctuations across trials were accounted for by arousal ratings, as expected, but also in a later time-window by the Self/Other condition. The Self/Other effect in SCR significantly accounted for 26% of variance in the Empathic Concern score measured with the IRI questionnaire. (B) Zygomatic activity was accounted for by both valence and arousal in a sustained manner throughout affective scene presentation, as well as by an interaction between Self/Other condition and valence which was significant in three transient time-windows. (C) Corrugator activity scaled negatively with valence (i.e., more contraction for negative valence) in a sustained manner, and briefly scaled negatively with arousal and Self/Other condition. Corrugator activity is also accounted for by the interaction between Self/Other condition and valence. (D) Interbeat intervals (IBIs) were measured from the IBI around Image Onset (ImOn) to the next subsequent ones (Im+1 to Im+4). IBIs were shorter for negative images, at the end of the affective scene presentations (repeated measure ANOVA, main effect of Time on the valence parameter estimate, IBIIm+4 t(1,31) = −3.69, pFDR = 0.004, BF10 = 37.05). (E) Zygomatic and corrugator activity binned for valence (negative, neutral, positive) separately for Self and Other shows that, particularly for positive valence, there are stronger contractions/relaxations when the Self perspective is adopted. Details on latencies of each cluster are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistics corresponding to Fig. 3. For each signal (Skin Conductance, Zygomatic, and Corrugator) we report the significant time-windows in seconds where the parameter estimates for arousal, valence etc.. differed significantly from zero. For each significant time-window, we report in parentheses the maxsum(t) and p-value. We use #1, #2 etc.… to indicate successive significant time-windows.

| Skin Conductance |

βarousal 2.219 – 3.656 s (147 0.004) βSelf/Other 4.250 – 4.688 s (39 0.040) |

| Zygomatic |

βvalence 1 – 5 s (38,743 0.002) βarousal#1 1.318 – 2.136 s (4453 0.01); #2 2.220 – 2.730 s (3753 0.014); #3 3.129 – 4.433 s (8582 0.004) βSelf/Other x valence#1 1.578 - 1.874 s (1904 0.032); #2 2.948 – 3.749 s (4162 0.018); #3 3.780 - 4.090 s (1568 0.04); #4 4.241 - 4.689 s (2282 0.024) |

| Corrugator |

βvalence 1 – 5 s (−47,309 0.002) βarousal 3.905 – 4.118 s (−1251 0.042) βSelf/Other 2.912 – 3.169 s (−1409 0.042) βSelf/Other x valence #1 1.977 - 2.511 s (−2826 0.006); #2 2.876 - 3.0469 s (−1346 0.029) |

Finally, as shown in Fig. 3A, we found that the Self/Other effect in SCR co-varied with Empathic Concern, as measured with the IRI questionnaire (robust correlation, r2 = 0.26, pFDR = 0.009, FDR corrected for the three subscales).

3.3.2. Zygomatic and corrugator activity scale with self/other condition depending on rated valence

Previous work has demonstrated that corrugator activity scales with negative valence, and zygomatic activity with positive valence (Dimberg and Karlsson, 1997; Lang et al., 1993). We reproduce those effects (Fig. 3B and 3C), that we find to be sustained throughout image presentation. We additionally found that both muscles varied with the arousal of the image, in line with previous findings (Fujimura et al., 2010).

We then tested whether facial EMG was also influenced by whether the image was rated for the Self or Other condition. In addition to a brief main effect of condition in the corrugator muscle, the activity in the both muscles (Fig. 3B and C, last column, and Table 1.) could be explained by an interaction between the condition and valence rating. Both zygomatic and corrugator activity were more tightly linked to valence ratings when the image was rated for Self rather than Other (Fig. 3E). To further verify that this effect was not due to the small difference in valence ratings between Self and Other conditions, we ran two separate models of zygomatic and corrugator activity in the Self and Other conditions, where valence ratings were z-scored independently in the Self and Other condition. We then tested whether the valence parameter estimate differed between Self and Other. We found a significant difference for zygomatic (one-tailed test; 2.74–3.80 s, maxum(t) = 4942, MonteCarlo p = 0.01 and 1.57–2.02 s, maxum(t) = 2220, MonteCarlo p = 0.04) and corrugator muscle activity (one-tailed test; 2.08–2.48 s, maxum(t) = −1759, MonteCarlo p = 0.03), with stronger contractions in the Self condition compared to Other.

Finally, the Self/Other condition effect in the corrugator and the interaction between valence and Self/Other condition in zygomatic and corrugator did not co-vary with any of the IRI subscores (all r2 < 0.03, all pFDR > 0.94, FDR corrected for the three subscales, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Robust correlations between the average beta value in the cluster for the SCR and corrugator condition effect, or the corrugator and zygomatic condition x valence interaction effect, with the subscales of the IRI questionnaire. P-values are FDR corrected based on the number of subscales (3 tests). **, pFDR<0.01.

| Corr. Self/Other | Corr. Self/Other x Valence | Zyg. Self/Other x Valence | SCR Self/Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perspective Taking | r2 = 0.01 pFDR = 0.70 |

r2 < 0.01 pFDR = 0.79 |

r2 < 0.01 pFDR = 0.96 |

r2 < 0.01 pFDR = 0.70 |

| Empathic Concern | r2 = 0.01 pFDR = 0.70 |

r2 = 0.01 pFDR = 0.79 |

r2 = 0.01 pFDR = 0.96 |

r2 = 0.26 pFDR = 0.009 ** |

| Personal Distress | r2 < 0.01 pFDR = 0.70 |

r2 < 0.01 pFDR = 0.79 |

r2 < 0.01 pFDR = 0.96 |

r2 = 0.02 pFDR = 0.69 |

3.3.3. IBI during image viewing co-varies with valence ratings, but not arousal nor self/other condition

We evaluated changes in IBI during image viewing based on the condition, rated valence and arousal, and their interactions. Consistent with previous literature (Bradley et al., 2001; Kreibig, 2010), we found that IBIs were modulated by valence, mostly at the end of scene presentation (Fig. 3D). In practice, we ran a GLM accounting for IBIs with the regressors Self/Other condition, valence, arousal and interaction between each rating and condition, for the 5 IBIs during scene presentation. Each parameter estimate was then submitted to a repeated measure ANOVA with Time as a factor with five levels. The only parameter estimate modulated by time was valence (F(4124) = 6.12, p = 0.002; all other parameter estimates: all F(4124) < 1.16, all p <0.32). This effect corresponded to a significant shortening of IBIs for positively rated images towards the end of the image viewing window (post-hoc t-tests against zero on the five IBIs, from IBI around image onset IBIImOn to the fourth IBI following image onset IBIIm+4, FDR corrected for number of tests (five): no effect at IBIImOn, IBIIm+1 nor IBIIm+2, all pFDR> 0.57, all BF10 > 0.21; trend at IBIIm+3: t(31) = −2.12, pFDR = 0.10, BF10 = 1.35; significant effect at IBIIm+4 t(31) = −3.69, pFDR = 0.004, BF10 = 37.05).

3.4. The self/other difference in physiological signals is independent from the self/other difference in HERs

We show that on the one hand, HERs before affective scene onset distinguish between Self and Other condition, and that on the other hand, both late SCR and facial EMG also covary with Self and Other. We further tested for correlations between those effects, but none were significant (robust correlations FDR corrected for the 4 tests; HER with SCR, r2 〈 0.01, pFDR = 0.94; HER with Self/Other effect in the corrugator or with the interaction between valence and Self/Other condition in corrugator and in zygomatic, all r2<0.04, all pFDR 〉 0.94). We then turned to the final question: do HERs and the different measures of physiological reactivity independently contribute to affective ratings?

3.5. Self/Other distinction in HERs accounts for valence rating in the self condition

Affective experience does feel qualitatively different depending on the Self or Other condition: feeling happy, and seeing someone else being happy can be rated similarly in terms of valence and arousal but nevertheless correspond to distinct experiences. We thus tested whether and how HERs might “colour” the affective experience differently in the Self and Other condition – in other words, whether HERs distinguishing between Self and Other during instructions, before any emotion is elicited, account for some of the variance in valence and arousal ratings, independently from physiological reactivity during scene presentation. Because we wanted to probe for qualitative, rather than quantitative differences in ratings between Self and Other, we ran separate models for Self and Other ratings, with ratings independently z-scored within each condition. This procedure additionally controlled for the small but systematic differences between Self and Other ratings.

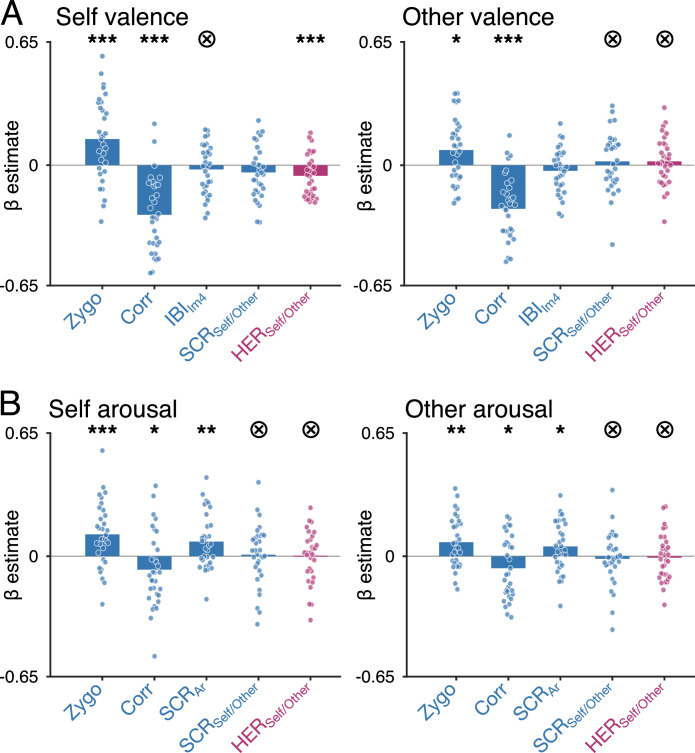

To test for a specific contribution of HERs to valence ratings, we modelled the valence ratings with the HER during cue. We also introduce in the model physiological reactivity during scene presentation (Zygomatic, Corrugator, 4th IBI co-varying with valence and SCR co-varying with Self/Other), to test whether HERs explain specific variance in the ratings that would not be accounted for by classical physiological markers. As shown in Fig. 4A, zygomatic and corrugator activity uniquely contributed for variance in valence ratings, in both the Self and Other condition. Crucially, HERs also significantly contributed to valence ratings in the Self condition, in addition to and independently from physiological reactivity. In the Other condition, Bayes statistics indicated that HERs did not contribute to valence ratings (see Table 3 for detailed statistics). The same rationale applied to arousal ratings (Fig. 4B) confirmed the link between SCR and arousal ratings, as well as the additional contribution of facial EMG. HERs did not contribute to arousal ratings, neither in Self nor Other condition.

Fig. 4.

HERs before affective scene presentation account for valence ratings in the Self condition. (A) Parameter estimates of models accounting for valence ratings, in the Self (left) and Other (right) conditions. HERs significantly contribute to valence ratings in the Self condition, but do not contribute to valence ratings in the Other condition. (B) Parameter estimates of models accounting for arousal ratings, in the Self (left) and Other (right) conditions. HERs do not significantly contribute to arousal ratings, neither in the Self nor in the Other condition.

***: p < 0.001, **: p < 0.01, *: p < 0.05, ⊗: BF10 < 0.33, indicating moderate evidence for the null hypothesis.

Table 3.

Statistics for each of the regressors used to model the ratings of Self and Other valence (left) and Self and Other arousal (right). Beta values of participants were tested against zero (two-tailed) per regressor, reported outcomes are t-value, p-value and BF10. ***: p < 0.001, **: p < 0.01, *: p < 0.05, ⊗: BF10 < 0.33.

| Self valence | Other valence | Self arousal | Other arousal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zygo | t(1,31) = 3.60 p = 0.001 *** BF10 = 30.12 |

t(1,31) = 2.66 p = 0.012 * BF10 = 3.70 |

Zygo | t(1,31) = 3.84 p < 10−3*** BF10 = 53.17 |

t(1,31) = 3.11 p = 0.004 ** BF10 = 9.76 |

| Corr | t(1,31) = −7.43 p < 10−3*** BF10 = 595,634 |

t(1,31) = −6.74 p < 10−3*** BF10 = 102,107 |

Corr | t(1,31) = −2.04 p = 0.05 * BF10 = 1.17 |

t(1,31) = −2.20 p = 0.04 * BF10 = 1.55 |

| IBIIm4 | t(1,31) = −0.95 p = 0.35 BF10 = 0.29 ⊗ |

t(1,31) = −1.44 p = 0.15 BF10 = 0.48 |

SCRArousal | t(1,31) = 3.06 p = 0.005 ** BF10 = 8.68 |

t(1,31) = 2.18 p = 0.04 * BF10 = 1.49 |

| SCRSelf/Other | t(1,31) = −1.57 p = 0.13 BF10 = 0.57 |

t(1,31) = 0.75 p = 0.46 BF10 = 0.25 ⊗ |

SCRSelf/Other | t(1,31) = 0.29 p = 0.77 BF10 = 0.20 ⊗ |

t(1,31) = −0.56 p = 0.58 BF10 = 0.22 ⊗ |

| HERSelf/Other | t(1,31) = −2.93 p = 0.006 ** BF10 = 6.46 |

t(1,31) = 0.91 p = 0.37 BF10 = 0.28 ⊗ |

HERSelf/Other | t(1,31) = −0.07 p = 0.94 BF10 = 0.19 ⊗ |

t(1,31) = −0.38 p = 0.71 BF10 = 0.20 ⊗ |

Together, these results show that classical physiological markers of valence and arousal, namely facial EMG and the arousal-covarying SCR, independently contribute to affective judgements irrespective of the condition in which an image is being rated. However, markers of Self/Other distinction, specifically the HER before affective scene onset, contribute to how images are rated in terms of experienced valence, in the Self condition only. This marker of Self/Other distinction thus appears to convey independent information which contributes to the quality of one's own affective experience.

4. Discussion

To understand the distinction between a felt emotion in first person perspective, and an emotion recognized in someone else, participants were prompted at each trial to rate social affective scenes according to their own emotional feeling, or to the emotional expression of people in the scene. They complied with instructions since the Self/Other perspective adopted led to small but consistent differences in affective ratings. Another objective marker of compliance with instructions is that physiological signals (SCR and facial EMG) during affective scene presentation were not only related to valence or arousal ratings, but also to the Self/Other perspective. As hypothesized, we found that preparing to rate an affective scene either from one's own perspective or from someone else's perspective led to differences in how the brain responds to heartbeats. The effect is not confounded by changes in heart rate nor in the electrocardiogram, effectively also ruling out differences in stroke volume (Buot et al., 2021), and is locked to heartbeats. Given prior evidence that Self specification and Self/Other distinction in non-emotional paradigms is related to heartbeat evoked responses (Babo-Rebelo et al., 2019; Babo-Rebelo et al., 2016, 2016; Park et al., 2016; Sel et al., 2017), our results suggest that HERs index a trans-domain mechanism for Self/Other distinction. In addition, the Self/Other discriminating HERs accounted for some of the variability of valence ratings, but only in the Self condition. They could thus account for the qualitative difference between experiencing an emotion in oneself vs. recognizing the emotion displayed by someone else.

4.1. Physiological measures distinguish between self and other

In addition to replicating classical findings showing that physiological signals are related to subjective ratings of valence and arousal (Bradley et al., 2001; Lang et al., 1993), we further reveal that facial muscle contractions and skin conductance response also indicate whether we are evaluating our own or someone else's emotions. Importantly, the modelling approach we used allows to rule out that Self/Other differences in physiological responses were due to a difference in the intensity of emotional ratings, thus refining previous results on emotional empathy (Drimalla et al., 2019; McRae et al., 2010) and pain empathy (Fusaro et al., 2016, 2019; Lamm et al., 2008).

We find that as expected SCR co-varies with arousal ratings, but further reveal that this effect is limited to the beginning of the SCR response. At later latencies, SCR co-varies with perspective, independently from arousal ratings. It should be noted that in the Self condition the judgement is always about one person (Self), while in the Other condition the judgement is sometimes on multiple people. This might have contributed to the Self/Other difference observed in the SCR. Because skin conductance is under descending sympathetic control of numerous subcortical and cortical regions (Beissner et al., 2013; Dawson et al., 2017), it is tempting to think that there are at least two distinct sets of brain regions controlling SCR, one related to arousal, independently from perspective, and another one related to Self- or Other- attribution, independently from arousal ratings. A larger Self/Other distinction in SCR co-varied with a larger score in empathic concern scale of the IRI, that assesses other-oriented feelings of sympathy (Davis, 1983). Altruistic helping behaviour requires appropriate Self/Other distinction: we need to be able to attribute feelings of distress to the other, rather than taking them on ourselves. The Self/Other effect in SCR might thus be related to a protective process, to avoid emotional contagion.

We also find that zygomatic and corrugator contractions co-vary with valence ratings more tightly in the Self condition, and that corrugator contractions additionally co-vary with the adopted perspective. Our results fit well with previous findings suggesting that facial mimicry, and facial expressions of emotions in general, are subject to contextual, top-down influences (Hess and Fischer, 2014). Theories on the role of facial expressions propose two main functions, namely signalling affiliations, or understanding of others through embodied simulations (Hess and Fischer, 2014; Wood et al., 2016). Although our design does not allow to draw conclusions about mimicry as an affiliative signal, our results seem at odds with the proposed role of facial mimicry in embodying emotions for understanding. In the Other condition, participants had the explicit instruction to try and understand how the person depicted in the image was feeling, yet the tightest link with valence ratings in facial muscles occurred when evaluating one's own emotions. Finally, since perspective influences physiological measures, our results place an upper limit on the numerous attempts at decoding affect from physiological measures in real life settings (Barrett et al., 2019).

4.2. Mapping the intersection between cognition and emotion: HERs as a trans-domain mechanism for self/other distinction

In affective sciences, Self/Other distinction is mostly put forward in the literature on empathy, where it is either part of the affective process (Walter, 2012) or a component in-between cognition and emotion (Decety and Lamm, 2006). While we do not directly probe empathy here, our results rather argue in favour of Self/Other distinction as an independent component, first because it can be activated before any affective feeling is elicited, and second because self-specifying or Self/Other differentiating HERs are also observed in non-emotional situations (Babo-Rebelo et al., 2019; Babo-Rebelo et al., 2016, 2016; Park et al., 2016; Sel et al., 2017). Our results thus contribute to map the mechanisms relevant to both emotions and cognition (Barrett et al., 2007). More generally, HERs have been proposed (Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014) to operationalize “the minimal self” (Blanke and Metzinger, 2009), i.e. the subject of experience which underlies the ‘I’ in experience and behaviour. The ‘I’ is characterized by a unified bodily centred viewpoint, and conveys an intrinsic ‘mineness’ to subjective experiences (Azzalini et al., 2019). It underlies all subjective experiences, whether perceptual, cognitive or affective (Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014). HERs appear to contribute to the minimal self, since in addition to Self/Other distinction in non-emotional paradigm, HERs contribute to subjective perception at threshold (Al et al., 2020; Al et al., 2021; Park et al., 2014), or in the cognitive domain, to choices based on subjective preferences (Azzalini et al., 2021).

While the mechanism grounding subjective experience to the minimal self – HERs – appear similar in perceptual, cognitive and affective paradigms, the regions where differential HERs are observed are task-dependent. They are observed in the default network during subjective visual perception (Park et al., 2014) and self-related thoughts during mind-wandering (Babo-Rebelo et al., 2016, 2016), whereas during bodily illusions (Park et al., 2016) or mental imagery with Self/Other perspective (Babo-Rebelo et al., 2019), they are observed in medial parietal regions. Here, we find that Self/Other differentiating HERs originate in both dorsal and ventral visual areas, as well as from the right frontal operculum, a region more lateral than the anterior agranular insula proper (Mesulam and Mufson, 1982), but to which it is connected in humans (Ghaziri et al., 2017). Intracranial EEG recordings in humans showed self-related HERs both in the anterior insula and in the frontal operculum (Babo-Rebelo et al., 2016; Park et al., 2018). It is notoriously difficult to draw any reverse inference from these regions, as they appear activated in many different paradigms. However, it is tempting to relate our findings to the hypothesis that the anterior insula / frontal operculum is activated when participants explicitly reflect upon themselves and their internal state (Namkung et al., 2017). The implication of visual areas might indicate that visual cortices are placed in different modes of processing depending on the perspective adopted to judge the emotional scene, effectively ‘colouring’ the perception of an upcoming affective scene differently depending on perspective, a point we further develop in the next section.

4.3. Neural markers of self/other distinction colour affective feelings

Providing the exact same rating value of happiness for myself, or for someone else, does not equate the quality of the subjective feeling: the happiness I feel is my own, it is directly experienced, while it is inferred in someone else. Interestingly, HERs as a marker of Self/Other distinction contribute to explaining some of the variance in subjective ratings of valence for Self only. As noted earlier, in the Self condition the judgement is always one person (Self), while in the Other condition the judgement is sometimes on multiple people. It seems unlikely that this is the source of the HER difference between Self and Other, since HERs are measured before scene presentation. Importantly, the HER difference was independent from the contribution of physiological responses to the ratings and persisted even when equating the mean and standard deviation of ratings for Self and for Other, suggesting indeed a qualitative difference. What is the nature of this contribution? They could contribute as ‘self evidence’ as in the minimal self hypothesis (Blanke and Metzinger, 2009; Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014), or they could represent the bodily signals upon which affective feelings are built, to use the formulation of the somatic marker hypothesis (Damasio, 1996).

Let us consider the nature of HER contributions. The fact that Self/Other discriminating HERs contribute to emotional ratings in the Self condition only could indicate that the brain integrates this specific signal together with physiological reactivity to generate the emotional feeling, as predicted by the somatic marker hypothesis (Craig, 2002; Damasio, 1996), even when those signals appear before affective scene onset. In other words, in this interpretation emotional processing would mistakenly integrate signals appearing too early. Besides, HERs do not covary with cardiac parameters, suggesting they reflect more a neural interpretation of cardiac inputs rather than information about bodily state. In the current experimental paradigm, interpreting HERs measured before affective scene onset in the framework of the somatic marker hypothesis is not parsimonious. Note that this interpretation is specific to this paradigm, where we measure HERs during perspective taking, before affective scene presentation. Another interpretation is that emotional processing - rightly- incorporates information about the perspective adopted, separately and independently from physiological reactivity, an interpretation which aligns well with the modelling results. We thus propose that HERs represent self-related evidence pertaining to the ‘I’ part of the judgement ‘To which extent do I feel happy’, which would be combined with the affective evidence collected after affective scene onset. The interpretation of the HER as evidence accumulation is in keeping with prior studies in the perceptual and cognitive domains. In an experiment on vision at threshold (Park et al., 2014), HERs before stimulus onset improved visual sensitivity, as if they were used as ‘I-related’ evidence to report ‘I have seen the grating’. In a preference-based choice task, where participants had to decide whether they preferred one movie over another, HERs before movie title onset interacted with movie valuation to yield more reliable choices (Azzalini et al., 2021).

5. Conclusion

A lot has been observed and written about brain-body interactions in emotions. Indeed, physiological reactivity is one of the components of the definition of an emotion, affective feeling and behaviour being the other two. Here, we demonstrate that the self- or other-perspective adopted modifies physiological reactivity during affective scene presentation. More crucially, we show that the response generated by the brain in response to heartbeats before affective scene onset indexes the perspective adopted, thus confirming the role of HERs in self-specification and Self/Other distinction previously observed in non-emotional paradigms. In addition, self-specifying HERs contribute to explain valenced feelings elicited in oneself by the affective scene. In other words, the self-specifying HERs appear related to the ‘I’ part of the judgement ‘To which extent do I feel happy’, and would be combined with the affective evidence proper collected after affective scene onset. This mechanism accounts for the qualitative, and fundamental, difference between felt affect and perceived affect.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tahnée Engelen: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Anne Buot: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. Julie Grèzes: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Catherine Tallon-Baudry: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant Agreement No. 670325, Advanced grant BRAVIUS) and senior fellowship of the Canadian Institute For Advance Research (CIFAR) program in Brain, Mind and Consciousness to C.T.-B. This research was also funded by Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR-17-EURE-0017, ANR-10- IDEX-0001–02). A CC-BY public copyright license has been applied by the authors to the present document and will be applied to all subsequent versions up to the Author Accepted Manuscript arising from this submission, in accordance with the grant's open access conditions.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.119867.

Contributor Information

Tahnée Engelen, Email: tahnee.engelen@yahoo.nl, tahnee.engelen@ens.fr.

Catherine Tallon-Baudry, Email: catherine.tallon-baudry@ens.psl.edu.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

The custom code and segmented data used for the main analyses in this article can be accessed online at https://osf.io/4eu9n/.

References

- Al E., Iliopoulos F., Forschack N., Nierhaus T., Grund M., Motyka P.…Villringer A. Heart-brain interactions shape somatosensory perception and evoked potentials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020;117(29):17448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012463117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al E., Iliopoulos F., Nikulin V.V., Villringer A. Heartbeat and somatosensory perception. Neuroimage. 2021;238(June) doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzalini D., Buot A., Palminteri S., Tallon-Baudry C. Responses to heartbeats in ventromedial prefrontal cortex contribute to subjective preference-based decisions. J. Neurosci. 2021;41(23):5102–5114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1932-20.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzalini D., Rebollo I., Tallon-Baudry C. Visceral signals shape brain dynamics and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019;23(6):488–509. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.03.007. (Regul. Ed.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babo-Rebelo M., Buot A., Tallon-Baudry C. Neural responses to heartbeats distinguish self from other during imagination. Neuroimage. 2019;191(January):10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babo-Rebelo M., Richter C.G., Tallon-Baudry C. Neural responses to heartbeats in the default network encode the self in spontaneous thoughts. J. Neurosci. 2016;36(30):7829–7840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0262-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babo-Rebelo M., Wolpert N., Adam C., Hasboun D., Tallon-Baudry C. Is the cardiac monitoring function related to the self in both the default network and right anterior insula? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biological Sci. 2016;(1708):371. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby R.M., Parker J.D.A., Taylor G.J. The twenty-item Toronto alexithymia scale-I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994;38(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L.F., Adolphs R., Marsella S., Martinez A.M., Pollak S.D. emotional expressions reconsidered: challenges to inferring emotion from human facial movements. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest. 2019;20(1):1–68. doi: 10.1177/1529100619832930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L.F., Mesquita B., Ochsner K.N., Gross J.J. The experience of emotion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007;58:373–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Ward C.H., Mendelson M., Mock J., Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissner F., Meissner K., Bär K.J., Napadow V. The autonomic brain: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis for central processing of autonomic function. J. Neurosci. 2013;33(25):10503–10511. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1103-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedek M., Kaernbach C. Decomposition of skin conductance data by means of nonnegative deconvolution. Psychophysiology. 2010;47(4):647–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanke O., Metzinger T. Full-body illusions and minimal phenomenal selfhood. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009;13(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.10.003. (Regul. Ed.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley M.M., Codispoti M., Cuthbert B.N., Lang P.J. Emotion and motivation I: defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion. 2001;1(3):276–298. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard D.H. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat. Vis. 1997;10(4):433–436. doi: 10.1163/156856897X00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buot A., Azzalini D., Chaumon M., Tallon-Baudry C. Does stroke volume influence heartbeat evoked responses? Biol. Psychol. 2021;165(December 2020) doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2021.108165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto B., Adolfi F., Velasquez M., Mesow M., Feinstein J., Canales-Johnson A.…Ibanez A. Heart evoked potential triggers brain responses to natural affective scenes: a preliminary study. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 2015;193:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig A.D. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3(August):655–666. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio A.R. The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1996;351(1346):1413–1420. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan-Glauser E.S., Scherer K.R. The Geneva affective picture database (GAPED): a new 730-picture database focusing on valence and normative significance. Behav. Res. Methods. 2011;43(2):468–477. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.H. A mulitdimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 1983;44(1):113–126. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M.E., Schell A.M., Filion D.L., Cacioppo G.G., Tassinary J.T., Berntson L.G. Handbook of Psychophysiology. Cambridge University Press; 2017. The electrodermal system; pp. 217–243. [Google Scholar]

- Decety J., Lamm C. Human empathy through the lens of social neuroscience. Sci. World J. 2006;6:1146–1163. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]