Abstract

Antidepressants are associated with traumatic injury and are widely used with other medications. It remains unknown how drug–drug–drug interactions (3DIs) between antidepressants and two other drugs may impact potential injury risks associated with antidepressants. We aimed to generate hypotheses regarding antidepressant 3DI signals associated with elevated injury rates. Using 2000–2020 Optum's de‐identified Clinformatics Data Mart, we performed a self‐controlled case series study for each drug triad consisting of an antidepressant + codispensed drug (base‐pair) with a candidate interacting medication (precipitant). We included persons aged greater than or equal to 16 years who (1) experienced an injury and (2) used a candidate precipitant, during base‐pair therapy. We compared injury rates during observation time exposed to the drug triad versus the base‐pair only, adjusting for time‐varying covariates. We calculated adjusted rate ratios (RRs) using conditional Poisson regression and accounted for multiple comparisons via semi‐Bayes shrinkage. Among 147,747 eligible antidepressant users with an injury, we studied 120,714 antidepressant triads, of which 334 (0.3%) were positively associated with elevated injury rates and thus considered potential 3DI signals. Adjusted RRs for signals ranged from 1.31 (1.04–1.65) for sertraline + levothyroxine with tramadol (vs. without tramadol) to 6.60 (3.23–13.46) for escitalopram + simvastatin with aripiprazole (vs. without aripiprazole). Nearly half of the signals (137, 41.0%) had adjusted RRs greater than or equal to 2, suggesting strong associations with injury. The identified signals may represent antidepressant 3DIs of potential clinical concern and warrant future etiologic studies to test these hypotheses.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

Antidepressants are associated with traumatic injury and are widely used together with other medications. The high rate of polypharmacy among antidepressant users raises the concern for potential drug interactions leading to unintentional traumatic injury. Although several studies have investigated pairwise antidepressant interactions associated with injury, higher‐order interactions involving more than two drugs (such as drug–drug–drug interactions [3DIs]) remain understudied.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

We aimed to generate hypotheses regarding potential antidepressant 3DI signals associated with elevated injury rates.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

Using real‐world data, we conducted high‐throughput pharmacoepidemiologic screening and identified 334 drug triads involving antidepressants that were associated with increased injury rates.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

The identified antidepressant triads suggest potential 3DIs with antidepressants that were of clinical concern. Researchers may use our findings to prioritize future etiologic studies of three‐way antidepressant interactions and injury.

INTRODUCTION

Over recent decades, antidepressants have become widely used in the United States for treating clinical depression and anxiety. From 2015 to 2016, antidepressants were the most commonly used prescription drugs among Americans aged 20–59, 1 and from 2015 to 2018, 13.2% of US adults reported using antidepressants in the past month. 2 Despite known benefits, antidepressants have the potential to adversely affect cognitive, psychomotor, and cardiac function, causing sedation, impaired balance, orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac arrhythmia—all of which potentially predispose users to accidents and resulting injuries. 3 Among older adults, antidepressant use has been linked to 1.3 times the risk of fall‐related injury, 4 1.7 times the risk of hip fracture, 5 and 1.8 times the risk of motor vehicle crash, 6 compared to nonuse.

Antidepressants are commonly used with other medications. In a sample of commercially insured antidepressant users, 68.1% were taking three or more additional medications at the time they began taking an antidepressant. 7 As other medications may have pharmacokinetic (e.g., by inhibiting antidepressants’ hepatic metabolism) or pharmacodynamic (e.g., by contributing to antidepressants’ central nervous system [CNS] effects) interactions with antidepressants, 8 , 9 they may heighten potential injury risks associated with antidepressants. In a recent pharmacoepidemiologic screening study, 256 antidepressant + co‐dispensed drug pairs had 1.1‐ to 3.1‐fold increased rates of unintentional traumatic injury, compared with antidepressant use alone 10 ; this study did not examine drug triads. Unintentional injury is a public health problem as it often causes morbidity and mortality and incurs substantial economic costs. 11 Recognizing the urgent need to reduce potentially preventable injuries arising from antidepressant drug interactions, the US Senate Special Committee on Aging and US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration recently highlighted the need for more research on identification of potentially harmful drug interactions. 12 Concerns regarding drug interactions have already informed clinical guidelines; for example, the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria strongly recommends clinicians avoid prescribing three or more CNS‐active drugs (including antidepressants) to prevent falls and fractures in older adults. 13

Despite increasing recognition of the potential dangers of antidepressant drug interactions, limited evidence exists on the health outcomes of drug–drug–drug interaction (3DIs) involving an antidepressant with two other drugs (i.e., triad). Current studies of triads have been limited to examinations of the associations between receipt of greater than or equal to three CNS medications (including antidepressants) and the risk of recurrent falls among older adults, without identifying specific antidepressant drug triads of clinical concern. 14 , 15 , 16 Given the high prevalence of polypharmacy in antidepressant users and the potential for severe consequences of unintentional injuries, it is critical to identify potentially harmful antidepressant drug triads so that patients and providers can strive to avoid the most risky combinations where possible. Limited resources often require researchers to prioritize drug triads of the highest clinical relevance. To assist with this prioritization, we conducted a high‐throughput pharmacoepidemiologic screening of real‐world data to generate hypotheses regarding antidepressant 3DI signals associated with elevated injury rates.

METHODS

Data source

Data came from Optum's de‐identified Clinformatics Data Mart from May 1, 2000, to February 29, 2020. This database contains billing records for inpatient stays, outpatient encounters, and dispensed prescriptions of greater than 71 million people enrolled in commercial or Medicare Advantage health insurance plans (Methods S1). The University of Pennsylvania's Office of Regulatory Affairs approved the study protocol (#831486).

Study design

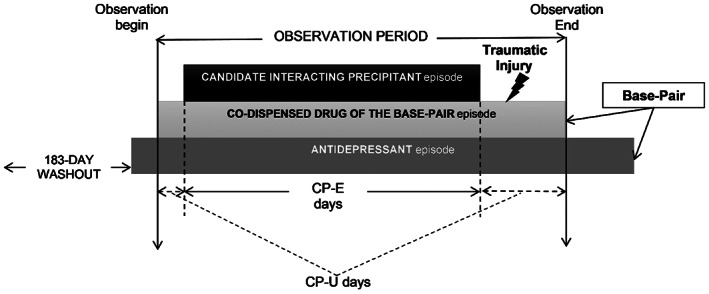

We performed a self‐controlled case series (SCCS) study for each unique drug triad consisting of an antidepressant + a co‐dispensed drug (base‐pair) with a candidate interacting medication (precipitant; Figure 1). The observation time consisted of days with base‐pair use and was classified as either exposed or unexposed based on whether a given individual also received candidate precipitant. Within each individual, the outcome rate during exposed person‐days was compared with unexposed person‐days, and an increased outcome rate signaled for potential 3DIs. This study design is well‐suited for 3DI screening as it controls for the effects of confounding variables that do not change over time, is highly computationally efficient, and has previously been used in high‐throughput pharmacoepidemiologic screening to identify drug interaction signals associated with injury. 10 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

FIGURE 1.

Example of an antidepressant + co‐dispensed drug base‐pair episode eligible for inclusion. For each eligible antidepressant initiator (defined as having a ≥ 183‐day washout period without antidepressant use before the first antidepressant dispensing), the observation period began on the first day with supplies of both the antidepressant and the co‐dispensed drug of the base‐pair. The study individual may have started the antidepressant first and then added on the co‐dispensed drug of the base‐pair (pictured), vice versa, or started both drugs simultaneously. Regardless, the observation period consisted exclusively of days with continuous base‐pair therapy. Days were categorized as candidate interacting precipitant exposed (CP‐E) or unexposed (CP‐U) based on whether the study individual had or did not have supply of a candidate interacting precipitant. The study individual was also required to experience a traumatic injury during the observation period. The comparison of interest was the rate of injury during CP‐E days versus CP‐U days. CP‐E, candidate interacting precipitant‐exposed; CP‐U, candidate interacting precipitant‐unexposed

Study sample

For each antidepressant triad (e.g., antidepressant + drug A as the base pair with drug B as the candidate precipitant), we first identified individuals aged greater than or equal to 16 years who initiated the antidepressant of interest without having received it in the prior 183 days. Among the antidepressant initiators, we limited the study sample to people who: (1) received the co‐dispensed drug of the base‐pair (drug A) while using the antidepressant, (2) experienced at least one outcome of interest (see Outcome) during base‐pair use (antidepressant + drug A), as the SCCS design requires outcome occurrence during the observation period, 21 and (3) received the candidate precipitant drug (drug B) concurrently with the base‐pair. As a concomitant medication taken with antidepressant could be classified as either drug A or drug B, we assembled a study sample for each scenario and examined the two triads separately: (1) antidepressant + drug A as the base‐pair with drug B as the candidate precipitant, and (2) antidepressant + drug B as the base‐pair and drug A as the candidate precipitant.

Follow‐up

We followed the study sample from the first day of base‐pair use until any of the following events occurred: (1) disenrollment from their healthcare plan, (2) discontinuation of base‐pair therapy, allowing a grace period of 20% days’ supply of the last dispensing, (3) switch from a solid to liquid dosage form of the antidepressant, or (4) study end (i.e., February 29, 2020).

Exposure

The exposure of interest was receipt of a candidate precipitant drug. To ensure the comprehensiveness of the screening, we considered all orally administered medications received by the individual during the base‐pair defined observation period as candidate precipitants. To mitigate reverse causation (i.e., the precipitant was prescribed to treat injury), the precipitant drugs’ dispensing date was pushed 1 day forward.

Outcome

The primary outcome was unintentional traumatic injury, operationalized as an inpatient hospitalization or emergency department visit due to an unintentional injury. We considered all types of unintentional injuries that were listed in the American College of Surgeons’ National Trauma Data Bank Data Standard (version March 2015), 22 except for burns, as they seem unlikely to have resulted from drug interactions. We further examined two injury subtypes as secondary outcomes: (1) typical hip fracture, defined as an unintentional traumatic injury with principal inpatient hospitalization diagnosis indicative of hip fracture; and (2) motor vehicle crash when the individual is driving, defined as an unintentional traumatic injury with external cause of injury codes indicative of a motor vehicle accident. We provide details of how these definitions were operationalized and their performance in Table S1.

Covariates

Because the SCCS design inherently controls for time‐invariant but not time‐varying confounders, we adjusted for the following time‐varying covariates: (1) antidepressant daily dose, dichotomized by the median, (2) follow‐up months since the first day of base‐pair use, dichotomized by one or greater than or equal to two, and (3) a binary indicator of ever having the outcome previously.

Statistics

For each antidepressant drug triad, we generated a conditional Poisson regression model to estimate rate ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and compared the injury rates during observation time exposed versus unexposed to the candidate precipitant drug (i.e., ), adjusting for the time‐varying covariates described in section Covariates. To ensure that our models were statistically stable, we only calculated RRs when there were greater than or equal to five individuals in the study sample and the variance of the parameter of interest was <10. To reduce the likelihood of false positive findings due to multiple testing, we adjusted RRs using semi‐Bayes shrinkage, which moved extreme values toward the overall average effect (Methods S1). Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 and STATA version 16.

RESULTS

A total of 147,747 people using an antidepressant were included in the analyses of injury (Table S2). Table 1 lists characteristics of people who received the most used antidepressants and experienced an unintentional traumatic injury. Among them, the median length of observation period ranged from 71.0 days for trazadone to 170.0 days for citalopram. Median age ranged from 59.7 years for people using bupropion to 81.2 years for mirtazapine. People using these antidepressants were predominantly women (62.3–71.8%) and White (67.1–73.5%). The largest samples were for sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram, consisting of 22,810, 20,397, and 19,028 individuals with an injury, respectively. In analyses of secondary outcomes, we included 7850 antidepressant users with a typical hip fracture (Table S3) and 806 with a motor vehicle crash (Table S4).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of users of most used antidepressants who experienced an unintentional traumatic injury

| Most used antidepressants | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline | Bupropion | Citalopram | Duloxetine | Escitalopram | Fluoxetine | ||

| Persons | Count | 6995 | 9580 | 20,397 | 12,553 | 19,028 | 11,082 |

| Days of observation period, per person | Median (Q1–Q3) | 87.0 (37.0–210.0) | 85.0 (37.0–195.0) | 170.0 (72.0–389.0) | 109.0 (42.0–277.0) | 144.0 (65.0–332.0) | 145.0 (65.0–345.0) |

| Age in years | Median (Q1–Q3) | 64.8 (51.4–75.2) | 59.7 (46.1–71.8) | 73.4 (60.9–82.1) | 68.9 (57.0–78.1) | 72.7 (57.3–82.3) | 67.1 (51.3–77.2) |

| Sex, count (%) | Female | 4820 (68.9) | 6240 (65.1) | 14,415 (70.7) | 8944 (71.2) | 13,236 (69.6) | 7880 (71.1) |

| Race, count (%) | White | 4696 (67.1) | 6925 (72.3) | 14,983 (73.5) | 8761 (69.8) | 13,604 (71.5) | 8011 (72.3) |

| African American | 885 (12.7) | 807 (8.4) | 1692 (8.3) | 1326 (10.6) | 1504 (7.9) | 917 (8.3) | |

| Hispanic | 520 (7.4) | 608 (6.3) | 1475 (7.2) | 992 (7.9) | 1623 (8.5) | 749 (6.8) | |

| Asian | 101 (1.4) | 101 (1.1) | 250 (1.2) | 149 (1.2) | 275 (1.4) | 139 (1.3) | |

| Unknown | 793 (11.3) | 1139 (11.9) | 1997 (9.8) | 1325 (10.6) | 2022 (10.6) | 1266 (11.4) | |

| Mirtazapine | Paroxetine | Sertraline | Trazodone | Venlafaxine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons | Count | 9897 | 8158 | 22,810 | 14,246 | 7166 |

| Days of observation period, per person | Median (Q1–Q3) | 76.0 (37.0–193.0) | 143.0 (64.0–334.0) | 152.0 (68.0–352.0) | 71.0 (37.0–179.0) | 134.0 (59.0–333.0) |

| Age in years | Median (Q1–Q3) | 81.2 (71.9–86.6) | 69.2 (53.5–79.5) | 73.7 (59.8–82.7) | 71.6 (58.8–81.6) | 62.9 (48.7–74.7) |

| Sex, count (%) | Female | 6595 (66.6) | 5672 (69.5) | 15,668 (68.7) | 8877 (62.3) | 5148 (71.8) |

| Race, count (%) | White | 6750 (68.2) | 5658 (69.4) | 16,377 (71.8) | 9591 (67.3) | 5262 (73.4) |

| African American | 1163 (11.8) | 686 (8.4) | 1927 (8.4) | 1671 (11.7) | 545 (7.6) | |

| Hispanic | 828 (8.4) | 679 (8.3) | 1758 (7.7) | 1161 (8.1) | 444 (6.2) | |

| Asian | 207 (2.1) | 109 (1.3) | 321 (1.4) | 232 (1.6) | 62 (0.9) | |

| Unknown | 949 (9.6) | 1026 (12.6) | 2427 (10.6) | 1591 (11.2) | 853 (11.9) | |

Abbreviation: Q, quartile.

Table 2 summarizes findings for unintentional traumatic injury after covariate adjustment and semi‐Bayes shrinkage. We examined 120,714 antidepressant drug triads, ranging from three triads that included fluvoxamine to 15,847 triads that included sertraline. A total of 334 (0.3%; Table S5) drug triads had statistically significant elevated RRs and were thus considered potential 3DI signals. Signals involved the 11 most widely used antidepressants—sertraline (80 signals, 0.5% of sertraline triads examined), citalopram (69 signals, 0.5% of citalopram triads examined), escitalopram (66 signals, 0.5% of escitalopram triads examined), trazodone (28 signals, 0.2% of trazodone triads examined), duloxetine (20 signals, 0.2% of duloxetine triads examined), paroxetine (20 signals, 0.3% of paroxetine triads examined), mirtazapine (19 signals, 0.2% of mirtazapine triads examined), fluoxetine (13 signals, 0.1% of fluoxetine triads examined), bupropion (7 signals, 0.1% of bupropion triads examined), venlafaxine (6 signals, 0.1% of venlafaxine triads examined), and amitriptyline (6 signals, 0.1% of amitriptyline triads examined). We identified no signals for other antidepressants. Table S6 summarizes RRs for typical hip fracture. Only one stable model was obtained for motor vehicle crash. We identified no signals for either of these secondary outcomes.

TABLE 2.

Summary data on rate ratios for unintentional traumatic injury after time‐varying covariate adjustment and semi‐Bayes shrinkage, by antidepressant

| Antidepressant a | Number of triads examined | Range of RRs, min – max | Number (%) of triads with statistically elevatedRRs b , c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline | 6979 | 0.31 – 2.36 | 6 (0.1) |

| Bupropion | 8062 | 0.28–2.07 | 7 (0.1) |

| Citalopram | 13,833 | 0.33–2.94 | 69 (0.5) |

| Desipramine | 5 | 0.39–0.54 | 0 |

| Desvenlafaxine | 620 | 0.49–2.23 | 0 |

| Doxepin | 1012 | 0.41–1.78 | 0 |

| Duloxetine | 13,258 | 0.32–2.63 | 20 (0.2) |

| Escitalopram | 14,562 | 0.39–6.60 | 66 (0.5) |

| Fluoxetine | 9324 | 0.38–2.74 | 13 (0.1) |

| Fluvoxamine | 3 | 0.25–0.32 | 0 (0.0) |

| Imipramine | 91 | 0.65–2.38 | 0 (0.0) |

| Mirtazapine | 8190 | 0.41–2.92 | 19 (0.2) |

| Nortriptyline | 2031 | 0.46–1.92 | 0 (0.0) |

| Paroxetine | 7100 | 0.33–2.31 | 20 (0.3) |

| Sertraline | 15,847 | 0.29–2.84 | 80 (0.5) |

| Trazodone | 12,262 | 0.38–2.51 | 28 (0.2) |

| Venlafaxine | 7262 | 0.41–2.16 | 6 (0.1) |

| Vilazodone | 72 | 0.88–2.31 | 0 |

| Vortioxetine | 201 | 0.60–1.67 | 0 |

Abbreviation: RR, rate ratio.

Brexpiprazole, clomipramine, and nefazodone were examined but did not have valid models and thus were excluded from this table.

After semi‐Bayes shrinkage.

Proportion was calculated for each antidepressant as the number of triads with statistically elevated RRs divided by the number of triads examined. For example, sertraline had 80 triads with statistically elevated RRs out of 15,847 triads examined, therefore the proportion was calculated as 80/15,847 = 0.5%.

Of the 334 3DI signals for injury, 137 (41.0%; Table 3) had adjusted RRs greater than or equal to 2, suggesting relatively strong associations between drug triads and elevated injury rates. The most common co‐dispensed drugs for these strong signals included cardiovascular with anti‐infective agents (n = 59, 18%), cardiovascular with CNS agents (44, 13%), CNS with CNS agents (8%), and renal/genitourinary with anti‐infective agents (8%). The strongest associations were identified for escitalopram + simvastatin with versus without aripiprazole (RR = 6.60, 95% CI: 3.23–13.46), escitalopram + olmesartan with versus without clonazepam (4.35, 2.09–9.07), and escitalopram + solifenacin with versus without sulfamethoxazole (2.99, 1.55–5.79).

TABLE 3.

Antidepressant drug–drug–drug interaction signals with semi‐Bayes shrunk adjusted rate ratios for unintentional traumatic injury greater than or equal to two, by antidepressant and therapeutic category of co‐dispensed drug

| Antidepressant | Therapeutic class of co‐dispensed drug of the base‐pair | Co‐dispensed drug of the base‐pair | Candidate interacting precipitant | RR, semi‐Bayes shrunk and adjusted a | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline | Cardiovascular | Losartan | Nitrofurantoin | 2.36 | 1.18–4.72 |

| Endocrine and metabolic | Levothyroxine | Tizanidine | 2.31 | 1.34–3.99 | |

| Levothyroxine | Celecoxib | 2.02 | 1.01–4.06 | ||

| Bupropion | Cardiovascular | Losartan | Zolpidem | 2.07 | 1.13–3.80 |

| Citalopram | Cardiovascular | Simvastatin | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.26 | 1.54–3.32 |

| Simvastatin | Trimethoprim | 2.21 | 1.50–3.25 | ||

| Atorvastatin | Cefuroxime | 2.44 | 1.29–4.62 | ||

| Isosorbide mononitrate | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.20 | 1.25–3.88 | ||

| Rosuvastatin | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.33 | 1.23–4.40 | ||

| Rosuvastatin | Trimethoprim | 2.33 | 1.23–4.40 | ||

| Isosorbide mononitrate | Trimethoprim | 2.11 | 1.20–3.69 | ||

| Atenolol | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.01 | 1.13–3.56 | ||

| Atenolol | Trimethoprim | 2.01 | 1.13–3.56 | ||

| Lisinopril | Losartan | 2.06 | 1.11–3.80 | ||

| Enalapril | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.19 | 1.04–4.63 | ||

| Enalapril | Trimethoprim | 2.17 | 1.03–4.55 | ||

| Central nervous system | Olanzapine | Lorazepam | 2.28 | 1.05–4.94 | |

| Gabapentin | Buspirone | 2.24 | 1.22–4.13 | ||

| Clonazepam | Tramadol | 2.10 | 1.24–3.57 | ||

| Donepezil | Trimethoprim | 2.09 | 1.35–3.24 | ||

| Donepezil | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.08 | 1.34–3.24 | ||

| Memantine | Azithromycin | 2.07 | 1.08–3.96 | ||

| Endocrine and metabolic | Norethindrone | Fluconazole | 2.94 | 1.43–6.06 | |

| Ethinyl estradiol | Fluconazole | 2.67 | 1.31–5.44 | ||

| Levothyroxine | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.38 | 1.73–3.29 | ||

| Levothyroxine | Trimethoprim | 2.20 | 1.60–3.04 | ||

| Levothyroxine | Tizanidine | 2.00 | 1.24–3.24 | ||

| Renal and genitourinary | Finasteride | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.36 | 1.16–4.82 | |

| Finasteride | Trimethoprim | 2.36 | 1.16–4.82 | ||

| Tamsulosin | Amoxicillin | 2.23 | 1.36–3.66 | ||

| Oxybutynin | Lisinopril | 2.19 | 1.25–3.84 | ||

| Duloxetine | Cardiovascular | Carvedilol | Nitrofurantoin | 2.15 | 1.12–4.12 |

| Losartan | Tamsulosin | 2.14 | 1.03–4.47 | ||

| Simvastatin | Donepezil | 2.10 | 1.12–3.91 | ||

| Central nervous system | Tizanidine | Dicyclomine | 2.63 | 1.31–5.27 | |

| Zolpidem | Meloxicam | 2.27 | 1.33–3.89 | ||

| Endocrine and metabolic | Allopurinol | Pregabalin | 2.58 | 1.19–5.60 | |

| Gastrointestinal | Pantoprazole | Mirabegron | 2.16 | 1.03–4.52 | |

| Hematological | Warfarin | Diazepam | 2.25 | 1.04–4.89 | |

| Escitalopram | Cardiovascular | Simvastatin | Aripiprazole | 6.60 | 3.23–13.46 |

| Olmesartan | Clonazepam | 4.35 | 2.09–9.07 | ||

| Benazepril | Trimethoprim | 2.89 | 1.35–6.16 | ||

| Rosuvastatin | Dexlansoprazole | 2.80 | 1.19–6.59 | ||

| Atenolol | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.76 | 1.49–5.13 | ||

| Atenolol | Trimethoprim | 2.76 | 1.49–5.13 | ||

| Simvastatin | Pregabalin | 2.49 | 1.16–5.35 | ||

| Pravastatin | Baclofen | 2.48 | 1.13–5.43 | ||

| Benazepril | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.44 | 1.14–5.25 | ||

| Terazosin | Alprazolam | 2.38 | 1.06–5.34 | ||

| Simvastatin | Clonazepam | 2.34 | 1.38–3.97 | ||

| Metoprolol | Naproxen | 2.15 | 1.32–3.52 | ||

| Diltiazem | Doxycycline | 2.14 | 1.14–4.02 | ||

| Atorvastatin | Carbidopa | 2.13 | 1.17–3.88 | ||

| Atorvastatin | Levodopa | 2.13 | 1.17–3.88 | ||

| Lisinopril | Divalproex | 2.03 | 1.05–3.92 | ||

| Central nervous system | Memantine | Divalproex | 2.36 | 1.28–4.36 | |

| Carbidopa | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.35 | 1.18–4.68 | ||

| Carbidopa | Trimethoprim | 2.35 | 1.18–4.68 | ||

| Levodopa | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.35 | 1.18–4.68 | ||

| Levodopa | Trimethoprim | 2.35 | 1.18–4.68 | ||

| Morphine | Ondansetron | 2.28 | 1.01–5.15 | ||

| Gabapentin | Loperamide | 2.23 | 1.04–4.79 | ||

| Ropinirole | Naproxen | 2.20 | 1.00–4.85 | ||

| Clonazepam | Aripiprazole | 2.18 | 1.08–4.41 | ||

| Risperidone | Tramadol | 2.08 | 1.02–4.25 | ||

| Memantine | Furosemide | 2.04 | 1.22–3.42 | ||

| Endocrine and metabolic | Levothyroxine | Aripiprazole | 2.94 | 1.63–5.29 | |

| Levothyroxine | Sumatriptan | 2.15 | 1.09–4.24 | ||

| Levothyroxine | Clonazepam | 2.14 | 1.41–3.24 | ||

| Allopurinol | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.13 | 1.07–4.23 | ||

| Allopurinol | Trimethoprim | 2.13 | 1.07–4.23 | ||

| Alendronate | Trimethoprim | 2.10 | 1.05–4.19 | ||

| Alendronate | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.07 | 1.03–4.15 | ||

| Gastrointestinal | Ranitidine | Alprazolam | 2.13 | 1.12–4.05 | |

| Hematological | Clopidogrel | Loperamide | 2.63 | 1.25–5.51 | |

| Renal and genitourinary | Solifenacin | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.99 | 1.55–5.79 | |

| Solifenacin | Trimethoprim | 2.84 | 1.46–5.51 | ||

| Oxybutynin | Codeine | 2.62 | 1.26–5.46 | ||

| Hydrochlorothiazide | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.46 | 1.61–3.77 | ||

| Hydrochlorothiazide | Trimethoprim | 2.37 | 1.55–3.64 | ||

| Fluoxetine | Cardiovascular | Pravastatin | Levofloxacin | 2.41 | 1.19–4.90 |

| Diltiazem | Gabapentin | 2.10 | 1.01–4.37 | ||

| Metoprolol | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.08 | 1.22–3.57 | ||

| Central nervous system | Alprazolam | Fluconazole | 2.48 | 1.23–4.99 | |

| Endocrine and metabolic | Metformin | Clonazepam | 2.74 | 1.40–5.36 | |

| Gastrointestinal | Esomeprazole | Cyclobenzaprine | 2.18 | 1.08–4.39 | |

| Renal and genitourinary | Triamterene | Oxycodone | 2.25 | 1.08–4.67 | |

| Spironolactone | Amoxicillin | 2.23 | 1.04–4.78 | ||

| Mirtazapine | Cardiovascular | Diltiazem | Amoxicillin | 2.92 | 1.55–5.50 |

| Diltiazem | Clavulanate | 2.51 | 1.23–5.12 | ||

| Pravastatin | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.22 | 1.08–4.55 | ||

| Metoprolol | Cefdinir | 2.02 | 1.03–3.97 | ||

| Digoxin | Tramadol | 2.00 | 1.08–3.70 | ||

| Endocrine and metabolic | Levothyroxine | Risperidone | 2.09 | 1.11–3.94 | |

| Paroxetine | Cardiovascular | Benazepril | Amoxicillin | 2.31 | 1.10–4.82 |

| Lovastatin | Tramadol | 2.22 | 1.06–4.67 | ||

| Losartan | Baclofen | 2.17 | 1.01–4.67 | ||

| Amlodipine | Meclizine | 2.05 | 1.01–4.19 | ||

| Endocrine and metabolic | Ethinyl estradiol | Cyclobenzaprine | 2.16 | 1.08–4.30 | |

| Sertraline | Cardiovascular | Atenolol | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.63 | 1.54–4.51 |

| Atenolol | Trimethoprim | 2.62 | 1.53–4.48 | ||

| Diltiazem | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.55 | 1.40–4.65 | ||

| Diltiazem | Trimethoprim | 2.44 | 1.34–4.42 | ||

| Lisinopril | Loperamide | 2.41 | 1.33–4.38 | ||

| Terazosin | Levofloxacin | 2.40 | 1.12–5.13 | ||

| Atorvastatin | Ropinirole | 2.14 | 1.11–4.15 | ||

| Diltiazem | Ondansetron | 2.01 | 1.10–3.69 | ||

| Central nervous system | Clonazepam | Loperamide | 2.41 | 1.06–5.48 | |

| Pregabalin | Doxycycline | 2.10 | 1.08–4.06 | ||

| Meloxicam | Gabapentin | 2.07 | 1.17–3.68 | ||

| Donepezil | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.04 | 1.24–3.34 | ||

| Endocrine and metabolic | Levonorgestrel | Cyclobenzaprine | 2.32 | 1.01–5.31 | |

| Levothyroxine | Megestrol | 2.11 | 1.15–3.88 | ||

| Levothyroxine | Metolazone | 2.05 | 1.03–4.08 | ||

| Allopurinol | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.02 | 1.08–3.77 | ||

| Hematological | Warfarin | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.34 | 1.31–4.17 | |

| Warfarin | Trimethoprim | 2.25 | 1.27–4.00 | ||

| Warfarin | Gabapentin | 2.06 | 1.24–3.43 | ||

| Clopidogrel | Quetiapine | 2.01 | 1.15–3.52 | ||

| Renal and genitourinary | Solifenacin | Trimethoprim | 2.84 | 1.36–5.96 | |

| Solifenacin | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.67 | 1.26–5.64 | ||

| Oxybutynin | Trimethoprim | 2.31 | 1.31–4.08 | ||

| Oxybutynin | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.29 | 1.29–4.07 | ||

| Trazodone | Cardiovascular | Isosorbide mononitrate | Gabapentin | 2.51 | 1.24–5.09 |

| Atorvastatin | Terbinafine | 2.41 | 1.12–5.17 | ||

| Pravastatin | Alprazolam | 2.33 | 1.25–4.34 | ||

| Atenolol | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.03 | 1.05–3.95 | ||

| Central nervous system | Tramadol | Gabapentin | 2.04 | 1.14–3.66 | |

| Quetiapine | Clonazepam | 2.03 | 1.07–3.86 | ||

| Meloxicam | Gabapentin | 2.00 | 1.18–3.39 | ||

| Endocrine and metabolic | Glimepiride | Meclizine | 2.15 | 1.01–4.59 | |

| Renal and genitourinary | Spironolactone | Ciprofloxacin | 2.30 | 1.26–4.22 | |

| Furosemide | Promethazine | 2.29 | 1.29–4.06 | ||

| Respiratory | Montelukast | Promethazine | 2.13 | 1.00–4.54 | |

| Venlafaxine | Cardiovascular | Simvastatin | Sulfamethoxazole | 2.11 | 1.12–3.97 |

| Simvastatin | Trimethoprim | 2.06 | 1.10–3.86 | ||

| Hematological | Clopidogrel | Methylprednisolone | 2.16 | 1.02–4.59 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RR, rate ratio.

Rate ratio was calculated as outcome rates during candidate interacting precipitant‐exposed days divided by outcome rates during candidate interacting precipitant–unexposed days (i.e., ), adjusting for the following time‐varying covariates: average daily dose of antidepressant, follow‐up month, and ever having a prior traumatic injury of interest.

DISCUSSION

We conducted high‐throughput pharmacoepidemiologic screening of real‐world data to identify potential antidepressant 3DIs of clinical concern. Among 120,714 antidepressant drug triads screened, 334 (0.3%) signaled for unintentional traumatic injury. Nearly half (137, 41.0%) of the signals had an adjusted RR greater than or equal to 2, suggesting relatively strong associations between these drug triads and elevated injury rates. In addition to unintentional traumatic injury, we also screened for associations with hip fracture and motor vehicle crash. No signals were ultimately identified, likely due to much smaller eligible samples for these outcomes.

Although not previously examined in etiologic studies, many of the 3DI signals identified in this study are biologically plausible. These signals can be classified into two categories based on their proposed mechanisms. The first and the most common mechanism is a pharmacodynamic interaction among the three drugs, wherein each drug is independently associated with risk of injury. For example, the co‐dispensed drug of the base‐pair and candidate precipitant drug often included CNS agents that may lead to additive sedative effects with antidepressants, 23 such as escitalopram + memantine (a CNS agent) with versus without divalproex (a CNS agent; RR = 2.36, 95% CI: 1.28–4.36). Other triads included antihypertensive agents that possibly worsen the orthostatic hypotension that may result from antidepressant use, 24 such as trazodone + furosemide (an antihypertensive agent) with versus without promethazine (2.29, 1.29–4.06). Finally, triads often included drugs with anticholinergic properties, such as escitalopram + oxybutynin (an anticholinergic agent) with versus without codeine (2.62, 1.26–5.46).

The second mechanistic category is a pairwise pharmacokinetic interaction within the base‐pair that is augmented by the pharmacodynamic interaction between antidepressant and precipitant drug. For example, the RR = 2.08 for the addition of tramadol to escitalopram + risperidone may be explained by the pharmacokinetic interaction between risperidone (a cytochrome P450 [CYP] 2D6 substrate) and escitalopram (a weak CYP2D6 inhibitor), 25 augmented by the pharmacodynamic interaction between tramadol and escitalopram. Escitalopram may increase risperidone's concentration by inhibiting its metabolism via CYP2D6, potentiating its CNS depressant effects. Tramadol not only may compound these CNS depression effects, but also may increase the risk of serotonin syndrome when combined with escitalopram 26 —both pharmacodynamic interaction pathways may lead to a traumatic injury. Another example is duloxetine + allopurinol with versus without pregabalin (2.58, 1.19–5.60). Pregabalin may worsen the CNS depression resulting from the theoretical pharmacokinetic interaction between duloxetine (a CYP1A2 substrate and CNS agent) and allopurinol (a weak CYP1A2 inhibitor). 27 CNS depression may lead to unintentional injury by causing somnolence, drowsiness, sedation, 28 and extrapyramidal side effects including tremors and involuntary muscle contraction. 29 Altogether, the above‐described biologically plausible signals bolster the validity of our screening approach and warrant increased clinical consideration to prevent potential injury.

Two identified signals with very strong associations (i.e., RR > 4) warrant a focused discussion. The near‐seven‐fold increased injury rate for escitalopram + simvastatin with versus without aripiprazole (6.6, 3.23–13.24) may be explained by a pharmacodynamic interaction between escitalopram and aripiprazole, as both have CNS depressant effects. However, if this were the only mechanistic pathway, one would expect all escitalopram triads with aripiprazole as the candidate precipitant and that had similar sample size as the escitalopram + simvastatin‐aripiprazole combination to be associated with increased injury rates, which we did not observe. For example, escitalopram + atorvastatin with versus without aripiprazole had an RR of 1.31 (0.61–2.79). Therefore, an additional or alternate but undetermined mechanism may be at play. The greater than four‐fold increased injury rate for escitalopram + olmesartan with versus without clonazepam (4.35, 2.09–9.07) may be explained by a pharmacodynamic interaction among the three drugs, as escitalopram and clonazepam have CNS depressant effects and olmesartan has hypotensive effects. Future etiologic research should assess whether this interaction result is likely to be additive or synergistic.

We also noticed that among the antidepressants screened, sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram had the largest number and proportion of drug triads signaled for increased injury rates. This pattern aligns with the findings of our previous screening on pairwise drug–drug interactions (DDIs), in which sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram were the three antidepressants with the most DDI signals for injury. 10 The reasons behind their higher number 3DI signals are unclear, as their pharmacokinetics are unlikely to differ from other antidepressants in a way that may contribute to more drug interactions. Notably, these three drugs also had larger sample sizes than any other antidepressants in the current study. Their larger number of 3DI signals may be partially explained by greater statistical power resulting from larger samples.

We also identified numerous signals with anti‐infectives as the candidate precipitant. Three potential explanations may underlie these signals. First, a pharmacokinetic interaction (e.g., altered hepatic metabolism) between the anti‐infective and the co‐dispensed drug in the base‐pair may be compounded by a CNS depressant effect of antidepressant. For example, the signal for fluoxetine + alprazolam with versus without fluconazole (2.48, 1.23–4.99) may be explained by fluconazole's inhibition of alprazolam's metabolism via CYP3A4, 30 in addition to fluoxetine's CNS depressant effects. Second is confounding by indication, as infection (instead of anti‐infectives) might be responsible for the increased injury rates. This is relevant because infection can cause confusion, delirium, and weakness especially in older adults, 31 predisposing patients to fall and resulting injury. Third is reverse causation, in which an injury results in anti‐infective treatment. The latter two explanations are threats to the validity of signals for triads including anti‐infectives. Future etiologic research on this subset of signals should strongly consider methodological approaches that mitigate these concerns.

This study has strengths including: a large sample size for the primary end point; use of the SCCS design, which addresses time‐invariant confounding and is extensively used in drug interaction screening research; and the focus on unintentional traumatic injury, a clinically relevant outcome with public health urgency.

Several limitations must also be considered. First is misclassification of drug use, given that data only document receipt, not consumption, of medications. Further, we lacked information on medications not covered by insurance, such as those purchased out of pocket or over the counter. Second is residual time‐varying confounding, including but not limited to confounding by indication for the candidate precipitant. For example, the signal for paroxetine + amlodipine with versus without meclizine (2.05, 1.01–4.19) may be explained by the fact that meclizine is typically prescribed to treat vertigo, which is a risk factor for falls leading to injury. To reduce confounding by indication, future etiologic studies should consider using a negative control precipitant drug as a qualitative or quantitative comparator, which was impractical in our high‐throughput screening study. Third is potential double‐counting of the same signal for drugs commonly prescribed as combination (e.g., trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole), because our screening was at the ingredient level. Last, given the high‐throughput nature of the screening approach, our study intended to generate rather than test hypotheses. Therefore, the identified 3DI signals should be confirmed by future etiologic studies before being used to guide clinical decisions.

In conclusion, we identified 334 antidepressant triads associated with elevated injury rates using real‐world data. Our findings represent antidepressant 3DIs of potential clinical concern and may inform future etiologic studies intended to test these hypotheses.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.C. and C.E.L. wrote the manuscript. C.C., C.E.L., S.H., and W.B.B. designed the research. C.C., S.H., C.M.B., W.B.B., S.D., S.P.C., J.R.H., K.F.B., and C.E.L. performed the research. C.M.B. and W.B.B. analyzed the data. C.M.B. and W.B.B. contributed analytic tools.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The US National Institutes of Health (R01AG060975, R01DA048001, R01AG064589, and R01AG025152) supported this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Leonard is an Executive Committee Member of and Dr. Hennessy directs the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Real‐World Effectiveness and Safety of Therapeutics. The Center receives funds from Pfizer and Sanofi to support pharmacoepidemiology education. Dr. Leonard recently received honoraria from the American College of Clinical Pharmacy Foundation, Health Canada, the University of Florida, the University of Massachusetts, the Scientific and Data Coordinating Center for the NIDDK‐funded Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study, and the Consortium for Medical Marijuana Clinical Outcomes Research. Dr. Leonard is a Special Government Employee of the US Food and Drug Administration and consults for their Reagan‐Udall Foundation (the opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as the position of the US Food and Drug Administration). Dr. Leonard receives travel support from John Wiley & Sons. Dr. Leonard's spouse is an employee of Merck; neither Dr. Leonard nor his spouse owns stock in the company. Dr. Horn is co‐author and publisher of The Top 100 Drug Interactions: A Guide to Patient Management and a consultant to Urovant Sciences and Seegnal US. Dr. Bilker serves on multiple data safety monitoring boards for Genentech. Dr. Dublin has research funding from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Hennessy has consulted for multiple pharmaceutical companies. All other authors declared no competing interests for this work.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

Chen C, Hennessy S, Brensinger CM, et al. Antidepressant drug–drug–drug interactions associated with unintentional traumatic injury: Screening for signals in real‐world data. Clin Transl Sci. 2023;16:326‐337. doi: 10.1111/cts.13452

REFERENCES

- 1. Martin CB, Hales CM, Gu Q, Ogden CL. Prescription drug use in the United States, 2015‐2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2019;334:1‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant use among adults: United States, 2015‐2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;377:1‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Darowski A, Chambers SA, Chambers DJ. Antidepressants and falls in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(5):381‐394. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200926050-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Macri JC, Iaboni A, Kirkham JG, et al. Association between antidepressants and fall‐related injuries among long‐term care residents. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(12):1326‐1336. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bakken MS, Engeland A, Engesæter LB, Ranhoff AH, Hunskaar S, Ruths S. Increased risk of hip fracture among older people using antidepressant drugs: data from the Norwegian prescription database and the Norwegian hip fracture registry. Age Ageing. 2013;42(4):514‐520. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meuleners LB, Duke J, Lee AH, Palamara P, Hildebrand J, Ng JQ. Psychoactive medications and crash involvement requiring hospitalization for older drivers: a population‐based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(9):1575‐1580. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03561.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller M, Pate V, Swanson SA, Azrael D, White A, Stürmer T. Antidepressant class, age, and the risk of deliberate self‐harm: a propensity score matched cohort study of SSRI and SNRI users in the USA. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(1):79‐88. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0120-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bleakley S. Antidepressant drug interactions: evidence and clinical significance. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. 2016;20(3):21‐27. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffelt C, Gross T. A review of significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with antidepressants and their management. Ment Health Clin. 2016;6(1):35‐41. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2016.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leonard CE, Brensinger CM, Acton EK, et al. Population‐based signals of antidepressant drug interactions associated with unintentional traumatic injury. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;110(2):409‐423. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peterson C, Miller GF, Barnett SBL, Florence C. Economic cost of injury ‐ United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(48):1655‐1659. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7048a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration . Multiple medications and vehicle crashes: Analysis of databases. https://trid.trb.org/view/863878. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- 13. By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society beers criteria® update expert panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674‐694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aspinall SL, Springer SP, Zhao X, et al. Central nervous system medication burden and risk of recurrent serious falls and hip fractures in veterans affairs nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(1):74‐80. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hanlon JT, Zhao X, Naples JG, et al. Central nervous system medication burden and serious falls in older nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(6):1183‐1189. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nace D, Aspinall S, Castle N, et al. Central nervous system medication burden & risk of serious falls in older nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(3):B21. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.12.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leonard CE, Brensinger CM, Pham Nguyen TP, et al. Screening to identify signals of opioid drug interactions leading to unintentional traumatic injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;130:110531. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dawwas GK, Hennessy S, Brensinger CM, et al. Signals of muscle relaxant drug interactions associated with unintentional traumatic injury: a population‐based screening study. CNS Drugs. 2022;36(4):389‐400. doi: 10.1007/s40263-022-00909-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen C, Hennessy S, Brensinger CM, et al. Skeletal muscle relaxant drug‐drug‐drug interactions and unintentional traumatic injury: screening to detect three‐way drug interaction signals. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(11):4773‐4783. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen C, Hennessy S, Brensinger CM, et al. Population‐based screening to detect benzodiazepine drug‐drug‐drug interaction signals associated with unintentional traumatic injury. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):15569. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-19551-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Whitaker HJ, Hocine MN, Farrington CP. The methodology of self‐controlled case series studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 2009;18(1):7‐26. doi: 10.1177/0962280208092342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. American College of Surgeons . National Trauma Data Standard: data dictionary. https://www.facs.org/media/mkxef10z/ntds_data_dictionary_2022.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- 23. Richelson E. Pharmacology of antidepressants. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(5):511‐527. doi: 10.4065/76.5.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rivasi G, Rafanelli M, Mossello E, Brignole M, Ungar A. Drug‐related orthostatic hypotension: beyond anti‐hypertensive medications. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(10):725‐738. doi: 10.1007/s40266-020-00796-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rao P, Bhagat N, Shah B, Bazegha M. Interaction between escitalopram and risperidone. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47(1):65. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nelson EM, Philbrick AM. Avoiding serotonin syndrome: the nature of the interaction between tramadol and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(12):1712‐1716. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. US Food and Drug Administration . Drug Development and Drug Interactions | Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers. https://www‐fda‐gov.proxy.library.upenn.edu/drugs/drug‐interactions‐labeling/drug‐development‐and‐drug‐interactions‐table‐substrates‐inhibitors‐and‐inducers. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- 28. Ray WA. Psychotropic drugs and injuries among the elderly: a review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;12(6):386‐396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Madhusoodanan S, Alexeenko L, Sanders R, Brenner R. Extrapyramidal symptoms associated with antidepressants‐‐a review of the literature and an analysis of spontaneous reports. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2010;22(3):148‐156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL, Harmatz JS, Ciraulo DA, Shader RI. Alprazolam pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and plasma levels: clinical implications. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54(Suppl):4‐14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. George J, Bleasdale S, Singleton SJ. Causes and prognosis of delirium in elderly patients admitted to a district general hospital. Age Ageing. 1997;26(6):423‐427. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.6.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.