Significance

DinI, LexA, UmuD, and λCI bind to RecA filaments sequentially and regulate the bacterial SOS response chronologically. Here, we find that, despite their different structures and oligomeric states, they all engage the same protein elements in the groove of RecA filaments. Due to the mutagenic effects of the bacterial SOS response, it has been targeted for suppression of the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Our structures explain five decades of research on bacterial SOS response and potentially will aid rational drug design to combat antimicrobial resistance.

Keywords: SOS response, RecA, LexA, UmuD, lambda repressor

Abstract

In response to DNA damage, bacterial RecA protein forms filaments with the assistance of DinI protein. The RecA filaments stimulate the autocleavage of LexA, the repressor of more than 50 SOS genes, and activate the SOS response. During the late phase of SOS response, the RecA filaments stimulate the autocleavage of UmuD and λ repressor CI, leading to mutagenic repair and lytic cycle, respectively. Here, we determined the cryo-electron microscopy structures of Escherichia coli RecA filaments in complex with DinI, LexA, UmuD, and λCI by helical reconstruction. The structures reveal that LexA and UmuD dimers bind in the filament groove and cleave in an intramolecular and an intermolecular manner, respectively, while λCI binds deeply in the filament groove as a monomer. Despite their distinct folds and oligomeric states, all RecA filament binders recognize the same conserved protein features in the filament groove. The SOS response in bacteria can lead to mutagenesis and antimicrobial resistance, and our study paves the way for rational drug design targeting the bacterial SOS response.

The SOS response is a global response to DNA damage in which the cell cycle is arrested and DNA repair and mutagenesis are induced (1–4). In bacteria, the LexA dimer acts as a transcriptional repressor for genes belonging to the SOS regulon by binding to a specific operator sequence in their promoter region. LexA protein is composed of two domains separated by a short flexible linker: an N-terminal DNA-binding domain (NTD) and a C-terminal catalytic/dimerization domain (CTD) with a Ser-Lys catalytic dyad (5, 6). After DNA damage, RecA binds the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), and in the presence of a nucleoside triphosphate converts to nucleoprotein filaments (7), which is bound and stabilized by DinI (8, 9). RecA filaments stimulate the autocleavage of LexA at A84-G85 peptide bond (10), leading to the derepression of over 50 genes (11–13).

The SOS response is precisely timed and synchronized according to the amount of damage and the time elapsed since the damage was detected. Error-free repair, i.e., homologous recombination and nucleotide excision repair, characterizes the early phase of SOS. If the damage can’t be repaired by error-free repair, RecA filaments further stimulate the autocleavage of UmuD at C24-G25 peptide bond, leading to the activation of error-prone repair (translesion synthesis) and mutagenesis (14–16). Since mutagenesis is a main driver of antimicrobial resistance development, RecA mediated LexA and UmuD cleavage could be targeted to tackle antimicrobial resistance (17–20).

The structures of RecA filaments and their complexes have been studied extensively by Egelman and coworkers using negative-staining electron microscopy (EM) (21–26). Their pioneering work showed that all RecA filament binders are bound within the deep groove of RecA filaments and provided a framework for understanding genetic and biochemical observations. However, due to the low resolution of negative-staining EM, the detailed interactions are missing, which hampers the rational drug design. In this work, we solved the cryo-EM structures of RecA filaments in complex with DinI, LexA, UmuD, and λCI at near-atomic resolutions. The structures show that the interactions involve the L2 loop and a patch of positively charged residues in the groove of RecA filaments, which potentially could be targeted for rational drug design.

Results and Discussion

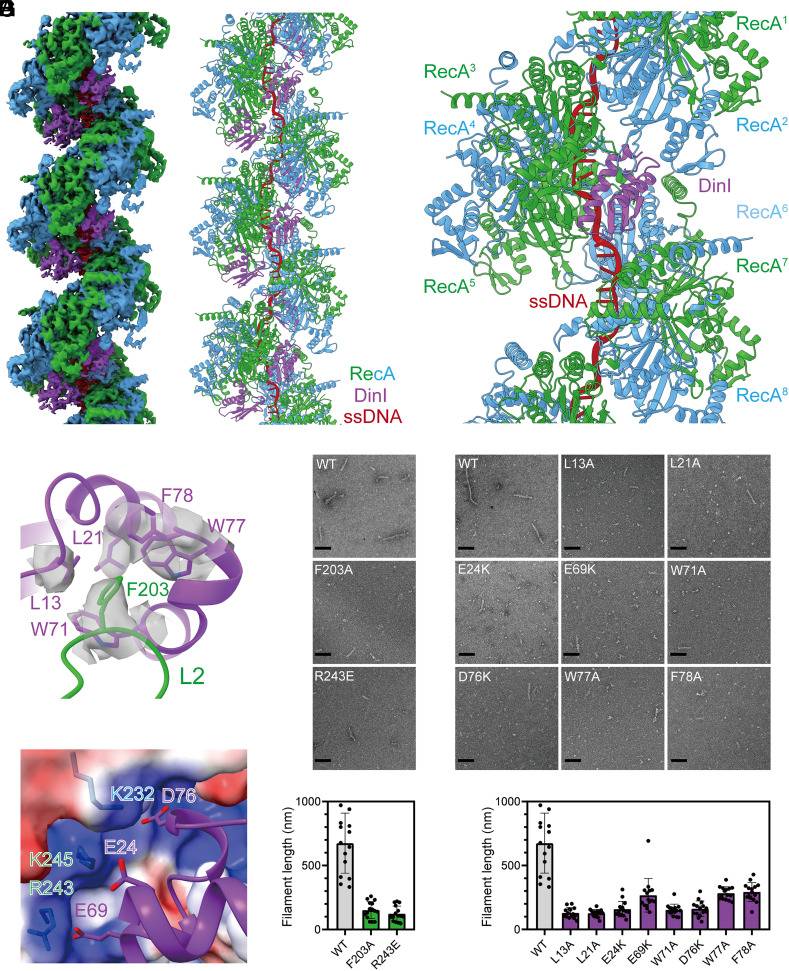

Structural Basis for DinI Mediated Stabilization of RecA Filaments.

First, the stabilization of RecA filaments by DinI was verified with negative-staining EM. As expected, RecA filaments formed with DinI are greater in number and significantly longer when compared with filaments observed in the absence of DinI (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). Then RecA was incubated with 27-nt oligo (dT) ssDNA, ATPγS, and DinI, and the cryo-EM structure of RecA-DinI was determined by helical reconstruction at a nominal resolution of 3.3 Å as determined by the gold standard Fourier shell correlation procedure (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3 and Table S1). The map shows helical filaments with ATPγS in RecA-RecA interfaces and ssDNA near filament axes (Fig. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 E and F). In addition, the map shows that DinI binds deeply in the groove of RecA filaments with two RecA protomers and one DinI molecule in each asymmetrical unit (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Two RecA protomers in the asymmetrical unit adopt similar conformations, with a Cα rmsd value of 0.67 Å. If a second DinI molecule was modeled into the asymmetrical unit, there would be a steric clash between DinI molecules, indicating that the stoichiometry is attributed to nearest neighbor exclusion. In the cryo-EM structure, each DinI molecule interacts with five continuous RecA protomers (RecA2 – RecA6) with a buried surface area of 983 Å2 (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Table S2), explaining the stabilization activity of DinI.

Fig. 1.

Structural basis for DinI mediated stabilization of RecA filaments. (A) The cryo-EM density map of RecA filaments in complex with DinI. Green and blue, RecA; purple, DinI; red, ssDNA. (B) The model of RecA filaments in complex with DinI. Colors as in A. (C) Each DinI molecule interacts with five continuous RecA protomers. Colors as in A. (D) L2 loop of RecA binds into a groove in DinI. Contact residues are shown as sticks. The map of contact residues is shown as transparent surfaces. Colors as in A. (E) Substitution of RecA residues decreases the length of RecA filaments in the presence of DinI. Representative EM photos and the statistics of filament lengths are shown in the Upper and Lower panels, respectively. The scale bar is 100 nm. Fifteen random fields were imaged, and the lengths of filaments longer than 40 nm were summed for each field. (F) Substitution of DinI residues decreases the length of RecA filaments in the presence of DinI. Representative EM photos and the statistics of filament lengths are shown in the Upper and Lower panels, respectively. The scale bar is 100 nm. Fifteen random fields were imaged, and the lengths of filaments longer than 40 nm were summed for each field. (G) A patch of negatively charged residues of DinI are positioned to make electrostatic interactions with a patch of positively charged residues in the groove of RecA filaments. Contact residues are shown as sticks. RecA surface is colored according to the electrostatic surface potential (blue, +5 kT; red, −5 kT). Other colors as in A.

RecA-DinI structure reveals the binding determinants for DinI. The most striking and novel feature of the structure is that the L2 loop of RecA3, previously implicated in DNA binding (27, 28), binds into a groove in DinI (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Specifically, L2 residue F203 inserts into a hydrophobic pocket formed by DinI residues L13, L21, W71, W77, and F78. Alanine substitution of L2 residue F203 does not affect RecA filament formation in the absence of DinI (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), but decreases the number and the length of RecA filaments in the presence of DinI (Fig. 1E), confirming that the cryo-EM structure is biologically relevant. Accordingly, alanine substitution of DinI residues L13, L21, W71, W77, and F78 jeopardizes its stabilization activity, as well (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, a patch of negatively charged residues of DinI (E24, E69, and D76) are positioned to make electrostatic interactions with a patch of positively charged residues (K232, R243, and K245) in the groove of RecA filaments (Fig. 1G). Consistently, charge reversal substitution of RecA residue R243 doesn’t affect filament formation in the absence of DinI (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), but decreases the number and the length of filaments in the presence of DinI (Fig. 1E). Moreover, charge reversal substitution of DinI residues E24, E69, and D76 affects its stabilization activity, as well (Fig. 1F).

RecA filaments formed with DinI are longer than the ssDNA (Fig. 1E). The longer filaments must be held together by protein–protein interactions between RecA oligomers rather than by the ssDNA itself. The RecA-DinI structure indicates that DinI stabilizes the longer filaments by spanning RecA-RecA interfaces rather than by increasing the RecA-RecA interface area. In fact, the RecA-RecA interface area in the structure of RecA-DinI (2,127 Å2) is similar to the structure of RecA alone (2,083 Å2) (27).

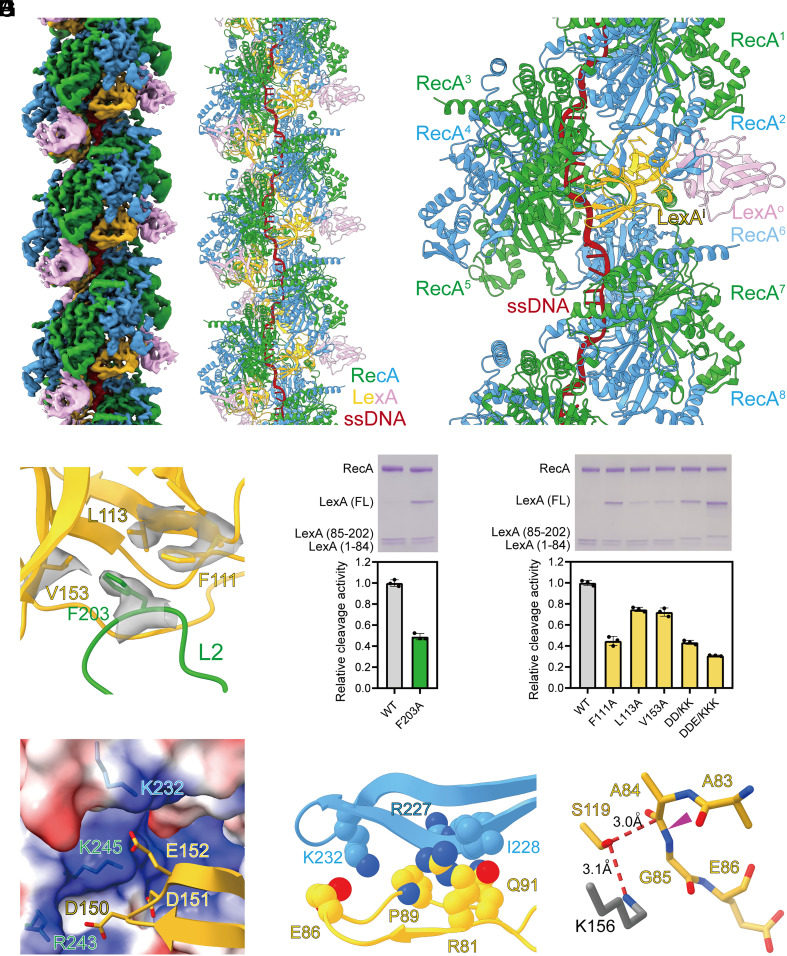

Structural Basis for RecA Mediated LexA Cleavage.

Initial attempts to determine the cryo-EM structure of the RecA filaments in the presence of full-length LexA by helical reconstruction failed to generate an interpretable map, which is consistent with the previous EM study (26). Then we turned to a NTD truncated LexA (residues 75 to 202), which underwent RecA mediated cleavage as well (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). To prevent cleavage during cryo-EM sample preparation, the general base, K156, of the Ser-Lys catalytic dyad was substituted with alanine. 3D classification shows that the sample is highly homogenous, so all particles were combined to generate the final reconstruction at 3.3 Å resolution (SI Appendix, Figs. S8 and S9 and Table S1). Surprisingly, the map shows that LexA dimer binds deeply in the groove of RecA filaments with two RecA protomers and one LexA dimer in each asymmetrical unit (Fig. 2 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). In the cryo-EM structure, each LexA dimer touches six continuous RecA protomers (RecA1 – RecA6) with a buried surface area of 1,540 Å2, among which the inside LexA protomer (LexAi) and the outside LexA protomer (LexAo) contribute 1,294 Å2 and 246 Å2, respectively (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Structural basis for RecA mediated LexA cleavage. (A) The cryo-EM density map of RecA filaments in complex with LexA. Green and blue, RecA; yellow and pink, LexA; red, ssDNA. (B) The model of RecA filaments in complex with LexA. Colors as in A. (C) Each LexA dimer touches six continuous RecA protomers. Colors as in A. (D) L2 loop of RecA binds into a groove in LexA. Contact residues are shown as sticks. The map of contact residues is shown as transparent surfaces. Colors as in A. (E) Substitution of RecA residues compromises RecA mediated LexA cleavage significantly. A representative gel photo and the statistics of cleavage activities are shown in the Upper and Lower panels, respectively. Error bars represent mean ± SD of n = 3 experiments; WT, wild type. (F) Substitution of LexA residues compromises RecA mediated LexA cleavage significantly. A representative gel photo and the statistics of cleavage activities are shown in the Upper and Lower panels, respectively. Error bars represent mean ± SD of n = 3 experiments; WT, wild type; DD/KK, D150K/D151K; DDE/KKK, D150K/D151K/E152K. (G) A patch of negatively charged residues of LexAi are positioned to make electrostatic interactions with a patch of positively charged residues in the groove of RecA filaments. Contact residues are shown as sticks. RecA surface is colored according to the electrostatic surface potential (blue, +5 kT; red, −5 kT). Other colors as in A. (H) The cleavage site region (CSR) of LexAi is stabilized by extensive van der Waals interactions with RecA. Contact residues are shown as spheres. Colors as in A. (I) The CSR of LexAi is primed for cleavage. The cleavage peptide bond is indicated by a purple triangle. The K156 of the Ser-Lys catalytic dyad is modeled as gray sticks. Other colors as in A.

Although the structure of LexA is dramatically different from DinI, their binding determinants are strikingly similar. The L2 loop of RecA3 binds into a groove in LexAi (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S11). In particular, L2 residue F203 inserts into a hydrophobic pocket formed by LexAi residues F111, L113, and V153. Alanine substitution of these interacting residues compromises RecA mediated LexA cleavage significantly (Fig. 2 E and F), confirming that the cryo-EM structure is biologically relevant. These interacting residues are conserved in RecA and LexA homologs (SI Appendix, Figs. S12 and S13), indicating that the hydrophobic interactions are also conserved in different bacteria.

Besides the hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions also contribute to the binding affinity of LexA. Specifically, a patch of negatively charged residues of LexAi (D150, D151, and E152) are positioned to make electrostatic interactions with the same patch of positively charged residues (K232, R243, and K245) in the groove of RecA filaments (Fig. 2G). Consistently, charge reversal substitution of two or three LexA residues in combination affects RecA mediated LexA cleavage substantially (Fig. 2F). Again, both the negatively charged cluster of LexA and the positively charged cluster of RecA are highly conserved (SI Appendix, Figs. S12 and S13), indicating that the electrostatic interactions are also conserved in different bacteria.

The cleavage site region (CSR) of LexAi is stabilized by extensive van der Waals interactions with RecA2 (Fig. 2H). For example, LexAi residues R81, E86, P89, and Q91 are positioned within 4.5 Å from RecA2 residues R227, I228, and K232. The C atom of A84 sits 3.0 Å from the Oγ of nucleophile S119, in the range of nucleophilic attack, indicating that the CSR of LexAi is primed for cleavage (Fig. 2I). In stark contrast, the CSR of LexAo is disordered due to the lack of protein–protein interaction (SI Appendix, Fig. S14).

RecA filaments formed with the NTD truncated LexA are significantly longer than the full-length LexA (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C and D). The longer filaments must be held together by protein–protein interactions between RecA oligomers. Our cryo-EM structure indicates that the NTD truncated LexA stabilizes the longer filaments by spanning RecA-RecA interfaces as DinI. If the crystal structure of full-length LexA was superimposed on our cryo-EM structure, there would be a steric clash between the NTD and CTD of neighboring LexA molecules (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Although the linker between the NTD and CTD is flexible, it is probably energetically unfavorable to avoid the steric clash. Therefore, the full-length LexA can’t bind to RecA filaments stoichiometrically or stabilize RecA filaments at the experimental concentration.

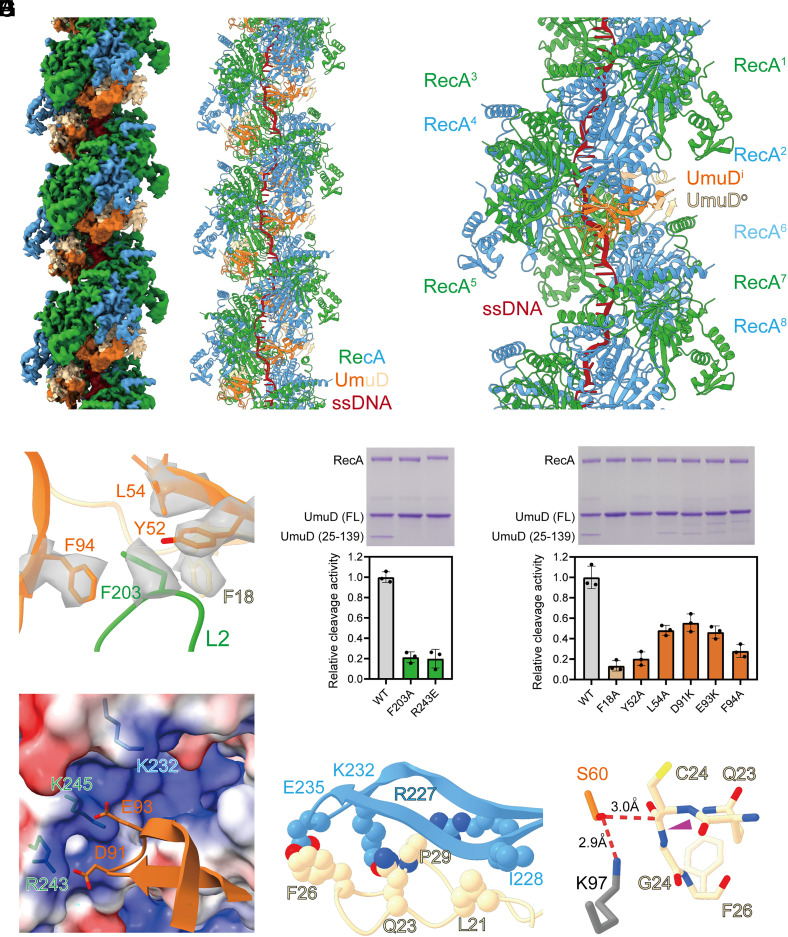

Structural Basis for RecA Mediated UmuD Cleavage.

Unlike LexA, UmuD only contains a catalytic/dimerization domain and cleaves intermolecularly (29–31). To define the molecular mechanism of RecA mediated UmuD cleavage, the cryo-EM structure of RecA filaments in complex with full-length UmuD was determined at 3.3 Å resolution by helical reconstruction (SI Appendix, Figs. S16–S18 and Table S1). To prevent cleavage during cryo-EM sample preparation, the general base, K97, of the Ser-Lys catalytic dyad was substituted with alanine. The map shows that UmuD dimer binds deeply in the groove of RecA filaments with two RecA protomers and one UmuD dimer in each asymmetrical unit (Fig. 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S19). The location and orientation of UmuD are similar to LexA (SI Appendix, Fig. S20). In the cryo-EM structure, each UmuD dimer contacts six continuous RecA protomers (RecA1 – RecA6) with a buried surface area of 1,567 Å2, among which the inside UmuD protomer (UmuDi) and the outside UmuD protomer (UmuDo) contribute 712 Å2 and 855 Å2, respectively (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Table S4).

Fig. 3.

Structural basis for RecA mediated UmuD cleavage. (A) The cryo-EM density map of RecA filaments in complex with UmuD. Green and blue, RecA; orange and tan, UmuD; red, ssDNA. (B) The model of RecA filaments in complex with UmuD. Colors as in A. (C) Each UmuD dimer contacts six continuous RecA protomers. Colors as in A. (D) L2 loop of RecA binds into a groove in UmuD. Contact residues are shown as sticks. The map of contact residues is shown as transparent surfaces. Colors as in A. (E) Substitution of RecA residues jeopardizes RecA mediated UmuD cleavage significantly. A representative gel photo and the statistics of cleavage activities are shown in the Upper and Lower panels, respectively. Error bars represent mean ± SD of n = 3 experiments; WT, wild type. (F) Substitution of UmuD residues jeopardizes RecA mediated UmuD cleavage significantly. A representative gel photo and the statistics of cleavage activities are shown in the Upper and Lower panels, respectively. Error bars represent mean ± SD of n = 3 experiments; WT, wild type. (G) A patch of negatively charged residues of UmuDi are positioned to make electrostatic interactions with a patch of positively charged residues in the groove of RecA filaments. Contact residues are shown as sticks. RecA surface is colored according to the electrostatic surface potential (blue, +5 kT; red, −5 kT). Other colors as in A. (H) The CSR of UmuDo is stabilized by extensive van der Waals interactions with RecA. Contact residues are shown as spheres. Colors as in A. (I) The CSR of UmuDo is primed for cleavage by UmuDi. The cleavage peptide bond is indicated by a purple triangle. The K97 of the Ser-Lys catalytic dyad is modeled as gray sticks. Other colors as in A.

Analogous to the structure of RecA-LexA, the L2 loop of RecA3 binds into a groove in UmuD, with L2 residue F203 inserting into a hydrophobic pocket formed by UmuDi residues Y52, L54, F94, and UmuDo residue F18 (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S21). Alanine substitution of these contact residues jeopardizes RecA mediated UmuD cleavage significantly (Fig. 3 E and F), confirming that the cryo-EM structure is biologically relevant. Further analogous to the structure of RecA-LexA, a patch of negatively charged residues of UmuDi (D91 and E93) are positioned to make electrostatic interactions with the same patch of positively charged residues (K232, R243, and K245) in the groove of RecA filaments (Fig. 3G). Consistently, charge reversal substitution of the inferred contact residues decreases RecA mediated UmuD cleavage substantially (Fig. 3 E and F).

The structure of RecA-UmuD unveils the molecular mechanism for the intermolecular cleavage by UmuD. In contrast to LexA, the CSR of UmuDi is disordered due to lack of protein–protein interaction, while the CSR of UmuDo is positioned similarly to the CSR of LexAi and stabilized by extensive van der Waals interactions with RecA2 (Fig. 3H). For instance, UmuDo residues L21, Q23, F26, and P29 are positioned within 4.5 Å from RecA2 residues R227, I228, K232, and E235. The C atom of C24 from UmuDo sits 3.0 Å from the Oγ of nucleophile S60 from UmuDi, in the range of nucleophilic attack, indicating that the CSR of UmuDo is primed for cleavage by UmuDi (Fig. 3I).

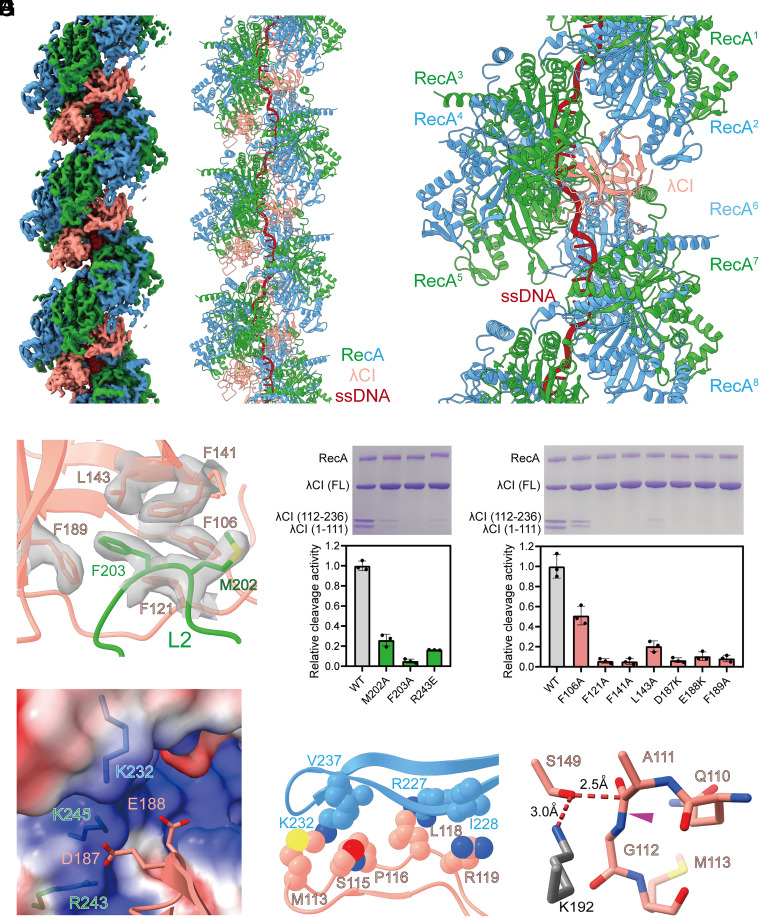

Structural Basis for RecA Mediated λCI Cleavage.

RecA filaments also stimulate the cleavage of repressor protein CI of λ phage at A111-G112 peptide bond, switching on its lytic cycle (32). To explore the extent to which the molecular mechanism of RecA mediated cleavage is conserved, we determined the cryo-EM structure of RecA filaments in complex with a NTD truncated λCI (residues 101 to 236), which has been used in a previous structural study (33) and underwent RecA mediated cleavage (SI Appendix, Fig. S22). To prevent cleavage during cryo-EM sample preparation, the general base, K192, of the Ser-Lys catalytic dyad was substituted with alanine. The structure was determined at a nominal resolution of 2.8 Å (SI Appendix, Figs. S23 and S24 and Table S1). Although λCI was dimer according to the gel filtration experiment (SI Appendix, Fig. S25) and the previous structural study (33, 34), the map shows that λCI monomer binds deeply in the groove of RecA filaments with two RecA protomers and one λCI molecule in each asymmetrical unit (Fig. 4 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S26), in accordance with the previous reports that λCI monomer is the preferred substrate for RecA (35, 36). The location of λCI is similar to LexAi and UmuDi, but the orientation of λCI is different (SI Appendix, Fig. S27). In the cryo-EM structure, each λCI molecule interacts with six RecA protomers (RecA2 – RecA6, and RecA8) with a buried surface area of 1,803 Å2 (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Table S5).

Fig. 4.

Structural basis for RecA mediated λCI cleavage. (A) The cryo-EM density map of RecA filaments in complex with λCI. Green and blue, RecA; salmon, λCI; red, ssDNA. (B) The model of RecA filaments in complex with λCI. Colors as in A. (C) Each λCI molecule interacts with six RecA protomers. Colors as in A. (D) L2 loop of RecA binds into a groove in λCI. Contact residues are shown as sticks. The map of contact residues is shown as transparent surfaces. Colors as in A. (E) Substitution of RecA residues decreases RecA mediated λCI cleavage significantly. A representative gel photo and the statistics of cleavage activities are shown in the Upper and Lower panels, respectively. Error bars represent mean ± SD of n = 3 experiments; WT, wild type. (F) Substitution of λCI residues decreases RecA mediated λCI cleavage significantly. A representative gel photo and the statistics of cleavage activities are shown in the Upper and Lower panels, respectively. Error bars represent mean ± SD of n = 3 experiments; WT, wild type. (G) A patch of negatively charged residues of λCI are positioned to make electrostatic interactions with a patch of positively charged residues in the groove of RecA filaments. Contact residues are shown as sticks. RecA surface is colored according to the electrostatic surface potential (blue, +5 kT; red, −5 kT). Other colors as in A. (H) The CSR of λCI is stabilized by extensive van der Waals interactions with RecA. Contact residues are shown as spheres. Colors as in A. (I) The CSR of λCI is in a cleavage competent conformation. The cleavage peptide bond is indicated by a purple triangle. The K192 of the Ser-Lys catalytic dyad is modeled as gray sticks. Other colors as in A.

Although the orientation of λCI is different from LexA and UmuD, their binding determinants are similar. The L2 loop of RecA3 binds into a groove in λCI, with L2 residues M202 and F203 inserting into a hydrophobic pocket formed by λCI residues F106, F121, F141, L143, and F189 (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Fig. S28). A patch of negatively charged residues of λCI (D187 and E188) are positioned to make electrostatic interactions with the same patch of positively charged residues (K232, R243, and K245) in the groove of RecA filaments (Fig. 4G). Substitution of these interacting residues compromises RecA mediated λCI cleavage significantly (Fig. 4 E and F), confirming that the cryo-EM structure is biologically relevant. In addition, the CSR of λCI makes significant van der Waals interactions with RecA2 (Fig. 4H), while the C atom of A111 is positioned 2.5 Å from the Oγ of nucleophile S149 (Fig. 4I), corroborating that the CSR of λCI is in a cleavage competent conformation.

To explore whether λCI dimer can bind to RecA filaments, the crystal structure of λCI dimer was superimposed on the cryo-EM structure of RecA-λCI. Steric clashes between RecA and the outside λCI protomer were observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S29), indicating that λCI dimer can’t bind to RecA filaments.

Our cryo-EM structures reveal the structural basis for the cleavage stimulation activity of RecA filaments (SI Appendix, Fig. S30). Both the L2 loop and the positively charged cluster are highly conserved features in the groove of the RecA filaments (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Only proteins who recognize these features by making hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions can bind into the groove, thereby avoiding the binding of irrelevant proteins. The CSRs are intrinsically flexible. The extensive van der Waals interactions with RecA stabilize the CSRs in a cleavage competent conformation, therefore stimulating their cleavage. Because all kinds of residues can make van der Waals interactions, the CSRs can be highly divergent (5).

The significance of RecA-LexA axis in the evolution of resistance under antibiotic stress and its value as therapeutic target have gained tremendous interest. Our cryo-EM structures provide a framework for designing drugs targeting the axis. Moreover, the workflow presented here can been utilized to study other RecA filament binders, such as RecX and AlpR (37–39).

Materials and Methods

RecA.

Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Inc.) was transformed with plasmid pET16b-RecA encoding N-heptahistidine-tagged RecA (1 to 335) under the control of the bacteriophage T7 gene 10 promoter. Single colonies of the resulting transformants were used to inoculate 1 l LB broth containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin, cultures were incubated at 37 °C with shaking until OD600 = 0.8, cultures were induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM, and cultures were incubated 16 h at 20 °C. Then, cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g; 15 min at 4 °C), resuspended in 25 mL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT), and lysed using a JN-02C cell disrupter (JNBIO, Inc.). After centrifugation (20,000 × g; 40 min at 4 °C), the supernatant was loaded onto a 1 mL column of Ni-NTA agarose (Smart-Lifesciences, Inc.) equilibrated with lysis buffer. The column was washed with 10 mL lysis buffer containing 0.02 M imidazole and eluted with 10 mL lysis buffer containing 0.3 M imidazole. The sample was further purified by anion-exchange chromatography on a HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare, Inc.). The flow through was applied to a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer A (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT). Fractions containing RecA were pooled and stored at −80 °C. Yield was ~1 mg/L, and purity was >95%. The same method was used to purify RecA mutants.

DinI.

DinI was prepared from E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Inc.) transformed with plasmid pET28a-DinI encoding DinI under the control of the bacteriophage T7 gene 10 promoter. Single colonies of the resulting transformants were used to inoculate 1 l LB broth containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin, cultures were incubated at 37 °C with shaking until OD600 = 0.8, cultures were induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM, and cultures were incubated 16 h at 20 °C. Then cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g; 10 min at 4 °C), resuspended in 20 mL buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol), and lysed using a JN-02C cell disrupter (JNBIO, Inc.). The lysate was centrifuged (20,000 × g; 45 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a 5 mL column of HiTrap Heparin HP (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer B and eluted with a 100 mL linear gradient of 0.075 to 1 M NaCl in buffer B. The sample was further purified by size exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer C (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 300 mM NaCl). Fractions containing DinI were pooled and stored at −80 °C. Yields were ~7.5 mg/L, and purities were >95%. The same method was used to purify DinI mutants.

LexA.

The NTD truncated LexA was prepared from E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Inc.) transformed with plasmid pET21a-LexA encoding C-hexahistidine-tagged LexA (L89P, K156A, and residues 75–202) under the control of the bacteriophage T7 gene 10 promoter. Single colonies of the resulting transformants were used to inoculate 1 l LB broth containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin, cultures were incubated at 37 °C with shaking until OD600 = 0.8, cultures were induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM, and cultures were incubated an additional 14 h at 18 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g; 10 min at 4 °C), resuspended in 20 mL buffer D (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.25 M NaCl, and 1 mM DTT), and lysed using a JN-02C cell disrupter (JNBIO, Inc.). The lysate was centrifuged (20,000 × g; 45 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a 1 mL column of Ni-NTA agarose (Smart-Lifesciences, Inc.) equilibrated with buffer D. The column was washed with 10 mL buffer D containing 0.02 M imidazole and eluted with 10 mL buffer D containing 0.3 M imidazole. The eluate was concentrated to 5 mL using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (10 kDa MWCO; Merck Millipore, Inc.) and applied to a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer E (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.2 M NaCl, and 1 mM DTT). Fractions containing LexA were pooled and stored at −80 °C. Yields were ~4 mg/L, and purities were >95%.

Full-length LexA was prepared from E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Inc.) transformed with plasmid pET28a-LexA encoding N-hexahistidine-tagged full-length LexA under the control of the bacteriophage T7 gene 10 promoter. Single colonies of the resulting transformants were used to inoculate 1 l LB broth containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin, cultures were incubated at 37 °C with shaking until OD600 = 0.8, cultures were induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM, and cultures were incubated an additional 14 h at 18 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g; 10 min at 4 °C), resuspended in 20 mL buffer F (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.3 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT), and lysed using a JN-02C cell disrupter (JNBIO, Inc.). The lysate was centrifuged (20,000 × g; 45 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a 1 mL column of Ni-NTA agarose (Smart-Lifesciences, Inc.) equilibrated with buffer E. The column was washed with 10 ml buffer F containing 0.02 M imidazole and eluted with 10 mL buffer F containing 0.3 M imidazole. The sample was further purified by anion-exchange chromatography on a HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare, Inc.). The flow through was applied to a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer F. Fractions containing full-length LexA were pooled and stored at −80 °C. Yield was ~6 mg/L, and purity was >95%. The same method was used to purify LexA mutants.

UmuD.

E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Inc.) was transformed with plasmid pET28a-UmuD encoding N-hexahistidine-tagged UmuD under the control of the bacteriophage T7 gene 10 promoter. Single colonies of the resulting transformants were used to inoculate 1 l LB broth containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin, cultures were incubated at 37 °C with shaking until OD600 = 0.8, cultures were induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM, and cultures were incubated an additional 14 h at 18 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g; 10 min at 4 °C), resuspended in 20 mL buffer D, and lysed using a JN-02C cell disrupter (JNBIO, Inc.). The lysate was centrifuged (20,000 × g; 45 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a 1 mL column of Ni-NTA agarose (Smart-Lifesciences, Inc.) equilibrated with buffer D. The column was washed with 10 mL buffer D containing 0.02 M imidazole and eluted with 10 mL buffer D containing 0.3 M imidazole. The eluate was concentrated to 5 mL using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (10 kDa MWCO; Merck Millipore, Inc.) and applied to a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer E. Fractions containing UmuD were pooled and stored at −80 °C. Yields were ~1.2 mg/L, and purities were >90%. The same method was used to purify UmuD mutants.

λCI.

The NTD truncated λCI was prepared from E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Inc.) transformed with plasmid pET21a-λCI encoding C-hexahistidine-tagged λCI (K192A, residues 101 to 236) under the control of the bacteriophage T7 gene 10 promoter. Single colonies of the resulting transformants were used to inoculate 1 l LB broth containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin, cultures were incubated at 37 °C with shaking until OD600 = 0.8, cultures were induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM, and cultures were incubated an additional 14 h at 18 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g; 10 min at 4 °C), resuspended in 20 mL buffer D, and lysed using a JN-02C cell disrupter (JNBIO, Inc.). The lysate was centrifuged (20,000 × g; 45 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a 1 mL column of Ni-NTA agarose (Smart-Lifesciences, Inc.) equilibrated with buffer D. The column was washed with 10 mL buffer D containing 0.02 M imidazole and eluted with 10 mL buffer D containing 0.3 M imidazole. The eluate was concentrated to 5 mL using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (10 kDa MWCO; Merck Millipore, Inc.) and applied to a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer E. Fractions containing λCI were pooled and stored at −80 °C. Yields were ~10 mg/L, and purities were >95%.

Full-length λCI was prepared from E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Inc.) transformed with plasmid pET24a-λCI encoding N-hexahistidine-tagged λCI under the control of the bacteriophage T7 gene 10 promoter. Single colonies of the resulting transformants were used to inoculate 1 l LB broth containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin, cultures were incubated at 37 °C with shaking until OD600 = 0.8, cultures were induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM, and cultures were incubated an additional 14 h at 18 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g; 10 min at 4 °C), resuspended in 20 mL buffer D, and lysed using a JN-02C cell disrupter (JNBIO, Inc.). The lysate was centrifuged (20,000 × g; 45 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a 1 mL column of Ni-NTA agarose (Smart-Lifesciences, Inc.) equilibrated with buffer D. The column was washed with 10 mL buffer D containing 0.02 M imidazole and eluted with 10 mL buffer D containing 0.3 M imidazole. The sample was further purified by anion-exchange chromatography on a HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare, Inc.). The flow through was applied to a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, Inc.) equilibrated in buffer E. Fractions containing full-length λCI were pooled and stored at −80 °C. Yield was ~10 mg/L, and purity was >95%. The same method was used to purify λCI mutants.

In Vitro Cleavage Assay.

The RecA mediated cleavage activity was analyzed by in vitro cleavage assay. The assay was performed in 25 μL of reaction mixtures containing 6 μM 27-nt oligo (dT) ssDNA, 2 μM RecA or RecA mutants, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM ATPγS. The mixtures were first incubated at 37 °C for 15 min to form RecA filament. For experiments with LexA, 2 μM LexA was added and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 20 min. For experiments with UmuD and λCI, 10 μM UmuD or λCI was added and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 45 min. The cleavage products were loaded onto 4 to 20% SDS-PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue and analyzed by ImageJ. Experiments were performed at least three times.

Negative-Staining EM Analysis.

Reaction mixtures contained (25 μL): 1 μM RecA, 3 μM 54-nt oligo (dT) ssDNA, 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 1 mM DTT, and 3 mM ATP. The mixtures were first incubated at 37 °C for 5 min, then 24 μM wild-type or mutant DinI was added and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 5 min. Carbon film grids (Zhongjingkeyi Technology, Inc.) were glow-discharged for 1 min at 25 mA before the application of 3 μL of complexes. The sample was stained with 3% uranyl acetate and imaged using a 120 kV Talos L120C (FEI, Inc.) equipped with a CMOS camera.

Assembly and Structural Determination of RecA-DinI.

Reaction mixture contained (40 μL): 14.4 μM RecA, 1.6 μM 27-nt oligo (dT) ssDNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 3 mM DTT, and 1 mM ATPγS. The mixture was first incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, then 50 μM DinI was added and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 1 h. UltrAuFoil grids (R 1.2/1.3; Quantifoil) were glow-discharged for 3 min at 20 mA before the application of 3 μL complex, then plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot (FEI, Inc.) with 95% chamber humidity at 10 °C.

The grids were imaged using a 300 kV Titan Krios equipped with a Falcon 4 direct electron detector (FEI, Inc.). Images were recorded with EPU in counting mode with a physical pixel size of 0.93 Å and a defocus range of 1.0 to 2.0 μm. Images were recorded with a 7 s exposure to give a total dose of 62 e/Å2. Subframes were aligned and summed using RELION’s own implementation of the UCSF MotionCor2 (40). The contrast transfer function was estimated for each summed image using CTFFIND4 (41). From the summed images, approximately 1,000 particles were manually picked and subjected to 2D classification in RELION (42). 2D averages of the best classes were used as templates for auto-picking in RELION. Picked particles were 3D auto-refined using a map of RecA filament (EMD-22524) (27) low-pass filtered to 40 Å resolution as a reference, then subjected to 3D classification focused in the filament groove without alignment. Focused 3D classification resulted in four classes, among which class 1 has a clear density for DinI. Particles in class 1 were 3D auto-refined and post-processed in RELION.

The cryo-EM structure of RecA filaments (PDB 7JY8) (27) and the NMR structure of DinI (PDB 1GHH) (43) were fitted into the cryo-EM density map using Chimera (44) and were adjusted in Coot (45). The coordinates were real-space refined with secondary structure restraints in Phenix (46).

Assembly and Structural Determination of RecA-LexA.

Reaction mixture contained (40 μL): 14.4 μM RecA, 1.6 μM 27-nt oligo (dT) ssDNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 3 mM DTT, and 1 mM ATPγS. The mixture was first incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, then 14.4 μM LexA was added and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 1 h. UltrAuFoil grids (R 1.2/1.3; Quantifoil) were glow-discharged for 3 min at 20 mA before the application of 3 μL complex, then plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot (FEI, Inc.) with 95% chamber humidity at 10 °C.

The grids were imaged using a 300 kV Titan Krios equipped with a Falcon 4 direct electron detector (FEI, Inc.). Images were recorded with EPU in counting mode with a physical pixel size of 1.19 Å and a defocus range of 1.0 to 2.0 μm. Images were recorded with a 9 s exposure to give a total dose of 52 e/Å2. Subframes were aligned and summed using RELION’s own implementation of the UCSF MotionCor2 (40). The contrast transfer function was estimated for each summed image using CTFFIND4 (41). From the summed images, approximately 1,000 particles were manually picked and subjected to 2D classification in RELION (42). 2D averages of the best classes were used as templates for auto-picking in RELION. Picked particles were 3D classified in RELION using a map of RecA filament (EMD-22524) (27) low-pass filtered to 40 Å resolution as a reference. Because all classes have a clear density for LexA, all particles were combined, 3D auto-refined, and post-processed in RELION.

The cryo-EM structure of RecA filaments (PDB 7JY8) (27) and the crystal structure of LexA (PDB 1JHE) (5) were fitted into the cryo-EM density map using Chimera (44) and were adjusted in Coot (45). The coordinates were real-space refined with secondary structure restraints in Phenix (46).

Assembly and Structural Determination of RecA-UmuD.

Reaction mixture contained (40 μL): 14.4 μM RecA, 1.6 μM 27-nt oligo (dT) ssDNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 3 mM DTT, and 1 mM ATPγS. The mixture was first incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, then 50 μM UmuD was added and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 1 h. UltrAuFoil grids (R 1.2/1.3; Quantifoil) were glow-discharged for 3 min at 20 mA before the application of 3 μL complex, then plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot (FEI, Inc.) with 95% chamber humidity at 10 °C.

The grids were imaged using a 300 kV Titan Krios equipped with a Falcon 4 direct electron detector (FEI, Inc.). Images were recorded with EPU in counting mode with a physical pixel size of 1.19 Å and a defocus range of 0.8 to 1.7 μm. Images were recorded with an 8 s exposure to give a total dose of 52 e/Å2. Subframes were aligned and summed using RELION’s own implementation of the UCSF MotionCor2 (40). The contrast transfer function was estimated for each summed image using CTFFIND4 (41). From the summed images, approximately 1,000 particles were manually picked and subjected to 2D classification in RELION (42). 2D averages of the best classes were used as templates for auto-picking in RELION. Picked particles were 3D classified in RELION using a map of RecA filament (EMD-22524) (27) low-pass filtered to 40 Å resolution as a reference. 3D classification resulted in four classes, among which only one class has a clear density for RecA filament. Particles in this class were 3D auto-refined, then subjected to 3D classification focused in the filament groove without alignment. Focused 3D classification resulted in four classes, among which class 1 has a clear density for UmuD. Particles in class 1 were 3D auto-refined and post-processed in RELION.

The cryo-EM structure of RecA filaments (PDB 7JY8) (27) and the crystal structure of UmuD (PDB 1UMU) (29) were fitted into the cryo-EM density map using Chimera (44) and were adjusted in Coot (45). The coordinates were real-space refined with secondary structure restraints in Phenix (46).

Assembly and Structural Determination of RecA-λCI.

Reaction mixture contained (40 μL): 14.4 μM RecA, 1.6 μM 27-nt oligo (dT) ssDNA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 3 mM DTT, and 1 mM ATPγS. The mixture was first incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, then 14.4 μM λCI was added and incubated at 37 °C for an additional 1 h. UltrAuFoil grids (R 1.2/1.3; Quantifoil) were glow-discharged for 3 min at 20 mA before the application of 3 μL complex, then plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot (FEI, Inc.) with 95% chamber humidity at 10 °C.

The grids were imaged using a 300 kV Titan Krios equipped with a Falcon 4 direct electron detector (FEI, Inc.). Images were recorded with EPU in counting mode with a physical pixel size of 1.19 Å and a defocus range of 0.8 to 1.7 μm. Images were recorded with an 8 s exposure to give a total dose of 50 e/Å2. Subframes were aligned and summed using RELION’s own implementation of the UCSF MotionCor2 (40). The contrast transfer function was estimated for each summed image using CTFFIND4 (41). From the summed images, approximately 1,000 particles were manually picked and subjected to 2D classification in RELION (42). 2D averages of the best classes were used as templates for auto-picking in RELION. Picked particles were 3D classified in RELION using a map of RecA filament (EMD-22524) (27) low-pass filtered to 40 Å resolution as a reference. 3D classification resulted in four classes, among which three classes have a clear density for λCI. Particles in these classes were combined, 3D auto-refined, and post-processed in RELION.

The cryo-EM structure of RecA filaments (PDB 7JY8) (27) and the crystal structure of λCI (PDB 2HNF) (47) were fitted into the cryo-EM density map using Chimera (44) and were adjusted in Coot (45). The coordinates were real-space refined with secondary structure restraints in Phenix (46).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Shenghai Chang at the Center of Cryo Electron Microscopy in Zhejiang University School of Medicine and Liangliang Kong at the cryo-EM center of the National Center for Protein Science Shanghai for help with cryo-EM data collection. We thank for the technical support by the Core Facilities, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. This work was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LR21C010002 to Y.F.) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970040 and 32270030 to Y. F.).

Author contributions

C.Z. and Y.F. designed research; B.G., L.L., L.S., and A.W. performed research; B.G., L.L., L.S., C.Z., and Y.F. analyzed data; and B.G., L.L., L.S., C.Z., and Y.F. wrote the paper.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Chun Zhou, Email: chunzhou@zju.edu.cn.

Yu Feng, Email: yufengjay@zju.edu.cn.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The accession numbers for the cryo-EM density maps reported in this paper are Electron Microscopy Data Bank: EMD-34151 (48), EMD-34152 (49), EMD-34153 (50), and EMD-34154 (51). The accession numbers for the atomic coordinates reported in this paper are Protein Data Bank: 7YWA (52), 8GMS (53), 8GMT (54), and 8GMU (55).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Little J. W., Mount D. W., The SOS regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Cell 29, 11–22 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker G. C., Mutagenesis and inducible responses to deoxyribonucleic acid damage in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 48, 60–93 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baharoglu Z., Mazel D., SOS, the formidable strategy of bacteria against aggressions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 1126–1145 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maslowska K. H., Makiela-Dzbenska K., Fijalkowska I. J., The SOS system: A complex and tightly regulated response to DNA damage. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 60, 368–384 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo Y., et al. , Crystal structure of LexA: A conformational switch for regulation of self-cleavage. Cell 106, 585–594 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang A. P., Pigli Y. Z., Rice P. A., Structure of the LexA-DNA complex and implications for SOS box measurement. Nature 466, 883–886 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell J. C., Plank J. L., Dombrowski C. C., Kowalczykowski S. C., Direct imaging of RecA nucleation and growth on single molecules of SSB-coated ssDNA. Nature 491, 274–278 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lusetti S. L., Drees J. C., Stohl E. A., Seifert H. S., Cox M. M., The DinI and RecX proteins are competing modulators of RecA function. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55073–55079 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lusetti S. L., Voloshin O. N., Inman R. B., Camerini-Otero R. D., Cox M. M., The DinI protein stabilizes RecA protein filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 30037–30046 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little J. W., Mechanism of specific LexA cleavage: Autodigestion and the role of RecA coprotease. Biochimie 73, 411–421 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quillardet P., Rouffaud M. A., Bouige P., DNA array analysis of gene expression in response to UV irradiation in Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 154, 559–572 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courcelle J., Khodursky A., Peter B., Brown P. O., Hanawalt P. C., Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 158, 41–64 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez De Henestrosa A. R., et al. , Identification of additional genes belonging to the LexA regulon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 1560–1572 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang Q., Karata K., Woodgate R., Cox M. M., Goodman M. F., The active form of DNA polymerase V is UmuD’(2)C-RecA-ATP. Nature 460, 359–363 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman M. F., McDonald J. P., Jaszczur M. M., Woodgate R., Insights into the complex levels of regulation imposed on Escherichia coli DNA polymerase V. DNA Repair (Amst) 44, 42–50 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaszczur M., et al. , Mutations for worse or better: Low-fidelity DNA synthesis by SOS DNA Polymerase V is a tightly regulated double-edged sword. Biochemistry 55, 2309–2318 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merrikh H., Kohli R. M., Targeting evolution to inhibit antibiotic resistance. FEBS J. 287, 4341–4353 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mo C. Y., et al. , Inhibitors of LexA autoproteolysis and the bacterial SOS response discovered by an academic-industry partnership. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 349–359 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alam M. K., Alhhazmi A., DeCoteau J. F., Luo Y., Geyer C. R., RecA inhibitors potentiate antibiotic activity and block evolution of antibiotic resistance. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 381–391 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yakimov A., et al. , Blocking the RecA activity and SOS-response in bacteria with a short alpha-helical peptide. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 9788–9796 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank E. G., et al. , Visualization of two binding sites for the Escherichia coli UmuD’(2)C complex (DNA pol V) on RecA-ssDNA filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 297, 585–597 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.VanLoock M. S., et al. , Complexes of RecA with LexA and RecX differentiate between active and inactive RecA nucleoprotein filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 333, 345–354 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.VanLoock M. S., et al. , ATP-mediated conformational changes in the RecA filament. Structure 11, 187–196 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galkin V. E., et al. , Cleavage of bacteriophage lambda cI repressor involves the RecA C-terminal domain. J. Mol. Biol. 385, 779–787 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galkin V. E., et al. , Two modes of binding of DinI to RecA filament provide a new insight into the regulation of SOS response by DinI protein. J. Mol. Biol. 408, 815–824 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu X., Egelman E. H., The LexA repressor binds within the deep helical groove of the activated RecA filament. J. Mol. Biol. 231, 29–40 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang H., Zhou C., Dhar A., Pavletich N. P., Mechanism of strand exchange from RecA-DNA synaptic and D-loop structures. Nature 586, 801–806 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z., Yang H., Pavletich N. P., Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA-ssDNA/dsDNA structures. Nature 453, 489–494 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peat T. S., et al. , Structure of the UmuD’ protein and its regulation in response to DNA damage. Nature 380, 727–730 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonald J. P., Frank E. G., Levine A. S., Woodgate R., Intermolecular cleavage by UmuD-like mutagenesis proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1478–1483 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald J. P., Peat T. S., Levine A. S., Woodgate R., Intermolecular cleavage by UmuD-like enzymes: Identification of residues required for cleavage and substrate specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 285, 2199–2209 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sauer R. T., Ross M. J., Ptashne M., Cleavage of the lambda and P22 repressors by recA protein. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 4458–4462 (1982). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell C. E., Frescura P., Hochschild A., Lewis M., Crystal structure of the lambda repressor C-terminal domain provides a model for cooperative operator binding. Cell 101, 801–811 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stayrook S., Jaru-Ampornpan P., Ni J., Hochschild A., Lewis M., Crystal structure of the lambda repressor and a model for pairwise cooperative operator binding. Nature 452, 1022–1025 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phizicky E. M., Roberts J. W., Kinetics of RecA protein-directed inactivation of repressors of phage lambda and phage P22. J. Mol. Biol. 139, 319–328 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen S., Knoll B. J., Little J. W., Mount D. W., Preferential cleavage of phage lambda repressor monomers by recA protease. Nature 294, 182–184 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stohl E. A., et al. , Escherichia coli RecX inhibits RecA recombinase and coprotease activities in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2278–2285 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drees J. C., Lusetti S. L., Chitteni-Pattu S., Inman R. B., Cox M. M., A RecA filament capping mechanism for RecX protein. Mol. Cell 15, 789–798 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McFarland K. A., et al. , A self-lysis pathway that enhances the virulence of a pathogenic bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 8433–8438 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng S. Q., et al. , MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rohou A., Grigorieff N., CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 192, 216–221 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheres S. H., RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 519–530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramirez B. E., Voloshin O. N., Camerini-Otero R. D., Bax A., Solution structure of DinI provides insight into its mode of RecA inactivation. Protein. Sci. 9, 2161–2169 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettersen E. F., et al. , UCSF Chimera–A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emsley P., Cowtan K., Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liebschner D., et al. , Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: Recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. D. Struct. Biol. 75, 861–877 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ndjonka D., Bell C. E., Structure of a hyper-cleavable monomeric fragment of phage lambda repressor containing the cleavage site region. J. Mol. Biol. 362, 479–489 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao B., Feng Y., Structure of DinI in complex with RecA filament. Electron Microscopy Data Bank https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-34151 Deposited 8 August 2022.

- 49.Gao B., Feng Y., Structure of LexA in complex with RecA filament. Electron Microscopy Data Bank https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-34152 Deposited 8 August 2022.

- 50.Gao B., Feng Y., Structure of UmuD in complex with RecA filament. Electron Microscopy Data Bank https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-34153 Deposited 8 August 2022.

- 51.Gao B., Feng Y., Structure of lambda repressor in complex with RecA filament. Electron Microscopy Data Bank https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-34154 Deposited 8 August 2022.

- 52.Gao B., Feng Y., Structure of DinI in complex with RecA filament. Electron Microscopy Data Bank https://www.rcsb.org/structure/7YWA Deposited 8 August 2022.

- 53.Gao B., Feng Y., Structure of LexA in complex with RecA filament. Protein Data Bank https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8GMS Deposited 8 August 2022.

- 54.Gao B., Feng Y., Structure of UmuD in complex with RecA filament. Protein Data Bank https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8GMT Deposited 8 August 2022.

- 55.Gao B., Feng Y., Structure of lambda repressor in complex with RecA filament. Protein Data Bank https://www.rcsb.org/structure/8GMU Deposited 8 August 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The accession numbers for the cryo-EM density maps reported in this paper are Electron Microscopy Data Bank: EMD-34151 (48), EMD-34152 (49), EMD-34153 (50), and EMD-34154 (51). The accession numbers for the atomic coordinates reported in this paper are Protein Data Bank: 7YWA (52), 8GMS (53), 8GMT (54), and 8GMU (55).