Abstract

A new series of 1-[ω-(bromophenoxy)alkyl]-uracil derivatives containing naphthalen-1-yl, naphthalen-2-yl, 1-bromonaphthalen-2-ylmethyl, benzyl, and anthracene-9-ylmethyl fragments in position 3 of uracil residue was synthesized. The antiviral properties of the synthesized compounds against human cytomegalovirus were studied. It was found that the compound containing a bridge consisting of five methylene groups exhibits a high anti-cytomegalovirus activity in vitro.

Keywords: uracil derivatives, synthesis, antiviral activity, human cytomegalovirus

INTRODUCTION

Viruses are the causative agents of many infectious diseases. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), one of the most common causes of human infections, infects T cells and alters their response. It is assumed that HCMV contributes to the development of arteriosclerosis [1] and immune aging [2], provokes inflammatory bowel diseases [3], and may contribute to the development of cancer due to its oncomodulatory effect [4, 5]. However, the main medical significance of HCMV is a congenital infection that causes hearing loss in newborns and in some cases leads to serious diseases: microcephaly, mental retardation, hepatosplenomegaly, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura [6]. In addition, congenital HCMV infection can lead to fetal loss and neonatal death [6, 7].

Currently, diseases caused by HCMV are treated with viral DNA polymerase inhibitors such as ganciclovir, cidofovir, and foscarnet, as well as their prodrugs valganciclovir and brincidofovir [8]. However, these drugs cause many side effects, including the toxic effects on the bone marrow (ganciclovir, valganciclovir, and cidofovir) and kidneys (foscarnet, cidofovir, and brincidofovir) [9, 10]. In addition, long-term therapy for HCMV infection can lead to the emergence of resistant HCMV variants [11]. Recently, letermovir and the nucleoside analogue maribavir, which have a different mechanism of action, have been approved as agents for the prevention of HCMV infection in patients with allogeneic stem cell transplantation [12, 13]. However, despite their low toxicity, their use also led to the emergence of letermovir- and maribavir-resistant HCMV variants [14]. For this reason, the search for new highly effective anti-HCMV agents is an important and relevant task.

Previously, we described a series of 1-[ω-(phenoxy)alkyl]-uracil derivatives that inhibited HCMV replication at concentrations comparable to those of ganciclovir [15]. The introduction of a (4-phenoxyphenyl)-acetamide fragment into position 3 of the pyrimidine ring led to an increase in virus-inhibiting properties [16]. 3-(3,5-Dimethylbenzyl) derivatives of 1-benzyl- and 1-(pyridylmethyl)uracil, showing dual activity against both HIV-1 and HCMV [17, 18], were described in the literature. We have recently discovered a series of uracil 1-cinnamyl derivatives containing benzyl and naphthalen-1-ylmethyl substituents at the nitrogen atom N3, which also exhibited activity against HIV-1 and HCMV [19]. In addition, a high anti-HCMV activity was shown for 1-[5-(4-bromophenoxy)pentyl]uracil derivatives, which had 3-(4-oxoquinazolin-3(4H)-yl)propyl [20] or 3-[(4-methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-7-yl)oxy]propyl substituent at the nitrogen atom N3 [21].

In view of above, we assumed that the presence of a bulky substituent at the nitrogen atom N3 of the pyrimidine ring gives compounds with a high activity against HCMV. Within the framework of this hypothesis, we synthesized a series of 1-[ω-(phenoxy)alkyl]uracil derivatives with a naphthalenylmethyl substituent in position 3 of the uracil residue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and Acros Organics and were used without prior purification.

General method for obtaining 3-arylmethyl-1-[ω-(bromophenoxy)alkyl]uracil derivatives 11–19 and 22–24. A suspension of 1-[ω-(4-bromophenoxy)alkyl]-uracil derivative 1–7 or 1-[5-(4-bromophenoxy)pentyl]quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (25) (1.416 mmol) and freshly calcined potassium carbonate (0.3 g, 2.171 mmol) was incubated in a DMF solution (10 mL) at 80°C for 1 h with stirring, cooled to room temperature, and supplemented with a solution of bromomethylnaphthalene (8–11), benzyl chloride (20), or 9-(chloromethyl)anthracene (21) (1.469 mmol) in DMF (5 mL). The obtained mixture was incubated at that temperature for 24 h with stirring and then evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was treated with water (80 mL). The mixture was extracted with 1,2-dichloroethane (4 × 20 mL), and the pooled extract was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with elution with ethyl acetate-1,2-dichloroethane (1 : 1). The product-containing fractions were pooled and evaporated in vacuo. The residue was crystallized from ethyl acetate–hexane (1 : 1) mixture. The target compounds 11–24 were obtained with yields of 74–89%.

1-[5-(4-Bromophenoxy)pentyl]quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (25). A suspension of quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (4.0 g, 24.67 mmol) and freshly calcined potassium carbonate (0.86 g, 6.222 mmol) was incubated in a DMF solution (50 mL) at 80°С for 1 h with stirring, supplemented with a solution of 1-bromo-4-[(5-bromopentyl)oxy]benzene (26) (1.99 g, 6.179 mmol) in DMF (20 mL), and the resulting mixture was incubated at that temperature for 24 h. The reaction mass was evaporated under reduced pressure, the residue was treated with water (100 mL) and extracted with 1,2-dichloroethane (4 × 50 mL), and the pooled extract was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was applied to a silica gel column and eluted with ethyl acetate, the product-containing fractions were pooled and evaporated in vacuo. The residue was crystallized from an isopropanol–hexane mixture (1 : 1). As a result, 1.7 g of a white fine crystalline product was obtained (yield 68%, m.p. 178–180°C, Rf 0.80 (ethyl acetate)).

1-(Naphthalen-1-ylmethyl)uracil (28). A solution of 2,4-bis(trimethylsilyloxy)pyrimidine obtained from uracil (1.5 g, 13.38 mmol) in anhydrous 1,2-dichloroethane (50 mL) was supplemented with 1-(bromomethyl)naphthalene (8) (2.85 g, 13.50 mmol). The obtained mixture was refluxed under protection from atmospheric moisture for 36 h. The reaction mass was cooled to room temperature, treated with isopropanol (10 mL), evaporated under reduced pressure to 2/3 volume, and diluted with hexane (20 mL). The formed precipitate was filtered off and recrystallized from a DMF–water (2 : 1) mixture. As a result, 2.26 g of a finely crystalline white product was obtained (yield 67%, m.p. 266–268°C (262–266°C lit.21), Rf 0.44 (ethyl acetate)).

3-[5-(4-Bromophenoxy)pentyl]-1-(naphthalen-1-ylmethyl)uracil (27). A suspension of 1-(naphthalen-1-ylmethyl)uracil (28) (0.5 g, 1.982 mmol) and freshly calcined potassium carbonate (0.5 g, 3.618 mmol) was incubated in a DMF solution (10 mL) at 80°C for 1 h with stirring, supplemented with a solution of 1-bromo-4-[(5-bromopentyl)oxy]benzene (26) (0.64 g, 1.987 mmol), and the resulting mixture was incubated at that temperature for 24 h with stirring. The reaction mass was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was treated with water (80 mL). The mixture was extracted with 1,2-dichloroethane (4 × 20 mL), and the pooled extract was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with elution with ethyl acetate–1,2-dichloroethane (1 : 1); the product-containing fractions were pooled and evaporated in vacuo. The residue was crystallized from ethyl acetate-hexane (1 : 1). As a result, 0.83 g of a finely crystalline white product was obtained (yield 85%, m.p. 92.5–93.5°C, Rf 0.65 (ethyl acetate–1,2-dichloroethane, 1 : 1)).

Antiviral Studies and Assessment of Cytostatic Activity

Compounds were tested against the following viruses: human cytomegalovirus (HCMV, strains AD-169 and Davis) and varicella zoster virus (VZV, strains OKA and YS). Antiviral studies were based on the inhibition of virus-induced cytopathic effect or plaque formation in human embryonic lung (HEL) cells as described earlier [21].

Cytostatic activity was also studied as described in [21].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

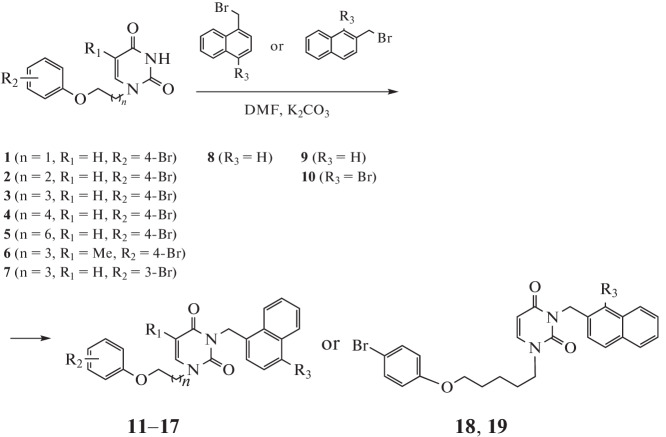

Obtaining the starting 1-[ω-(4-bromophenoxy)alkyl]uracil derivatives 1–6 was described earlier [15]. The synthesis of 1-[5-(3-bromophenoxy)uracil (7) was described by Paramonova et al. [21]. The target compounds of the naphthalenylmethyl series were obtained by alkylation of 1-[ω-(phenoxy)alkyl]uracil derivatives 1–7 with 1-(bromomethyl)naphthalene (8, R3 = H), 2-(bromomethyl)naphthalene (9, R3 = H), or 1-bromo-2-(bromomethyl)naphthalene (10, R3 = Br) under previously described conditions [18, 22]. In DMF solution in the presence of K2CO3, the corresponding 1-[ω-(phenoxy)alkyl]-3-(naphthalen-1-ylmethyl) (11–14) or 3-(naphthalen-2-ylmethyl) (15, 16) uracil derivatives were formed (Scheme 1), the yield of which was in the range of 74–89%.

Scheme 1.

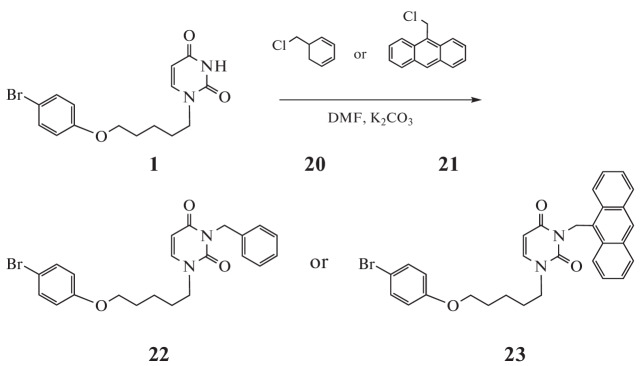

A number of analogues were synthesized to study the structure–antiviral activity dependence. In particular, 1-[5-(4-bromophenoxy)pentyl]-3-benzyl- (22) and -(anthracen-9-ylmethyl)uracil (23) derivatives were obtained by treating uracil 1 with benzyl chloride (20) or 9-(chloromethyl)anthracene (21) in DMF solution in the presence of K2CO3, the yield of which was 81 and 79%, respectively (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

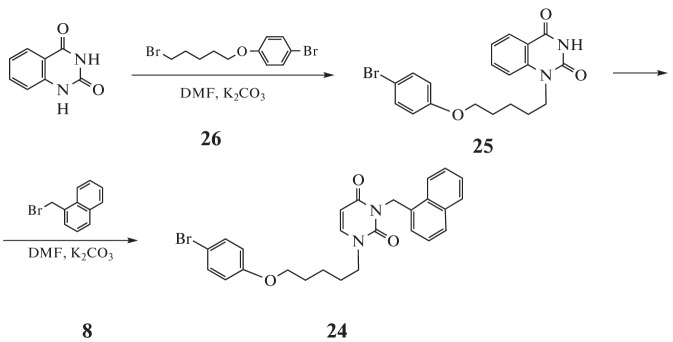

Another analogue was 1-[5-(4-bromophenoxy)pentyl]-3-(naphthalen-1-ylmethyl)quinazolin-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (24). The starting 1-[5-(4-bromophenoxy)pentyl]quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (25) was obtained by alkylation of a 4-fold molar excess of quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione 1-bromo-4-[(5-bromopentyl)oxy]benzene (26) in DMF solution in the presence of K2CO3. 1-Substituted quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione (25) as a result of treatment with 1-(bromomethyl)naphthalene (8) was converted into the target compound 24 with a 77% yield (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

In conclusion, an isomer of compound 14, 3-[5-(4-bromophenoxy)pentyl]-1-(naphthalen-1-ylmeth-yl)uracil (27), was obtained. Its synthesis included the step of obtaining 1-(naphthalen-1-ylmethyl)uracil (28) by condensation of 2,4-bis(trimethylsilyloxy)pyrimidine with 1-(bromomethyl)naphthalene (8) by boiling in an anhydrous 1,2-dichloroethane solution. Uracil 28 in DMF solution in the presence of K2CO3 was treated with 1-bromo-4-[(5-bromopentyl)oxy]benzene (26), which led to the target compound 27 with a 85% yield (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

The activity of the compounds was evaluated against herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, varicella zoster virus, vaccinia virus, respiratory syncytial virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, Coxsackie B4 virus, parainfluenza 3 virus, influenza A virus (subtypes H1N1 and H3N2), influenza B virus, reovirus-1, Sindbis virus, Punta Toro virus, as well as against HCMV(strains AD-169 and Davis).

The activity of compounds 11–19, 22–24, and 27 against HCMV was studied in HEL cells. The results of the study are presented in Table 1. It was found that compound 13 showed a significant anti-HCMV activity: it blocked virus replication at a concentration (EC50) of 2.19 µM (AD-169 and Davis strains), which significantly exceeded the effect of ganciclovir and was comparable to the effect of cidofovir. Compounds 11 and 12, which have a short bridge, were less effective inhibitors of HCMV replication. Their EC50 values were in the range of 8.94–10.94 µM. However, elongation of the bridge to six and especially to eight methylene groups led to an increase in cytotoxicity (compounds 14 and 15). The relocation of the bromine atom in the 4-bromophenoxy fragment from the para to meta position entailed a complete loss of antiviral activity (compound 16). The thymine analogue of compound 13 (compound 17) turned out to be more than an order of magnitude less active (EC50 44.72 and 48.9 µM for strains AD-169 and Davis, respectively). Naphthalen-2-yl analogue 18 and its 1-bromo derivative 19 did not show any inhibitory activity. Apparently, the spatial position of the naphthalene fragment plays an important role in the manifestation of antiviral properties. The substitution of the naphthalene fragment with a benzyl one gave compound 22 with fairly interesting properties, the EC50 values of which were 10.9 µM (AD-169 strain) and 15.3 µM (Davis strain). 3-(Anthracen-9-ylmethyl) derivative 23 was completely inactive. The substitution of the uracil residue with quinazolin-2,4(1H,3H)-dione also yielded an inactive compound (24). The regioisomer of compound 13, 3-[5-(4-bromophenoxy)pentyl]-1-(naphthalen-1-ylmethyl)uracil (compound 27), was more than one order of magnitude less active against HCMV.

Table 1.

Anti-HCMV properties of 3-arylmethyl-1-[ω-(bromophenoxy)alkyl]-uracil derivatives 11–19, 22–24, and 27

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | n | Antiviral activity, EC50, µMa | Cytotoxicity, µM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD-169 | Davis | cell morphology, МССb | cell growth, CС50с | |||||

| 11 | H | 4-Br | H | 1 | 9.78 | 10.94 | 100 | >100 |

| 12 | H | 4-Br | H | 2 | 8.94 | 8.94 | 100 | 10.82 |

| 13 | H | 4-Br | H | 3 | 2.19 | 2.19 | >100 | 75.7 |

| 14 | H | 4-Br | H | 4 | >4 | 8.94 | 20 | – |

| 15 | H | 4-Br | H | 6 | >0.8 | 1.79 | 4 | – |

| 16 | H | 3-Br | H | 3 | >20 | >100 | 20 | – |

| 17 | Me | 4-Br | H | 3 | 44.72 | 48.9 | 100 | – |

| 18 | – | – | H | 3 | >4 | >4 | 20 | – |

| 19 | – | – | Br | 3 | >20 | >20 | 100 | – |

| 22 | – | – | – | – | 10.9 | 15.3 | 100 | >100 |

| 23 | – | – | – | – | > 4 | > 4 | 20 | – |

| 24 | – | – | – | – | >100 | >100 | >100 | – |

| 27 | – | – | – | – | 36.57 | 44.72 | >100 | – |

| Ganciclovir | – | – | – | – | 3.15 | 9.21 | >350 | >350 |

| Cidofovir | – | – | – | – | 1.49 | 1.49 | >300 | >300 |

aEffective concentration required to reduce virus plaque formation by 50%.

bMinimum cytotoxic concentration that causes microscopically detectable changes in cell morphology.

cCytotoxic concentration required to reduce cell growth by 50%.

CONCLUSIONS

Thus, we have found a number of highly active anti-HCMV agents that inhibited HCMV replication at concentrations superior to the effect of ganciclovir and comparable to the effect of cidofovir. The results of this study will serve as a basis for creating a highly effective drug for the treatment of HCMV infections.

Abbreviations:

- HCMV

human cytomegalovirus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

FUNDING

The study was performed within the framework of the state assignment on the topic “Nucleic Bases Derivatives as Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Replication.” The biological part of the work was supported by KU Leuven.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. This article does not contain any studies involving animals or human participants performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Translated by M. Batrukova

REFERENCES

- 1.Rodríguez-Goncer I., Fernández-Ruiz M., Aguado J.M. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2020;18:113–125. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1707079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karrer U., Mekker A., Wanke K., Tchang V., Haeberli L. Exp. Gerontol. 2009;44:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jentzer A., Veyrard P., Roblin X., Saint-Sardos P., Rochereau N., Paul S., Bourlet T., Pozzetto B., Pillet S. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1078. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8071078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson A.K., Walker L.C., Cox B., Rollag H., Robinson B.A., Morrin H., Pearson J.F., Potter J.D., Paterson M., Surcel H.M., Pukkala E., Currie M.J. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2020;22:585–602. doi: 10.1007/s12094-019-02164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lv Y.L., Han F.F., An Z.L., Jia Y., Xuan L.L., Gong L.L., Zhang W., Ren L.L., Yang S., Liu H., Liu L.H. Intervirology. 2020;63:10–16. doi: 10.1159/000506683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plotkin S.A., Boppana S.B. Vaccine. 2019;37:7437–7442. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Permar S.R., Schleiss M.R., Plotkin S.A. J. Virol. 2018;92:e00030–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00771-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotton C.N. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2019;24:469–475. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sellar R.S., Peggs K.S. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012;12:1161–1172. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.693471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faure E., Galperine T., Cannesson O., Alain S., Gnemmi V., Goeminne C., Dewilde A., Béné J., Lasri M., Lessore de Sainte Foy C., Lionet A. Medicine. 2016;95:e5226. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan B.H. Options . Infect. Dis. 2014;6:256–270. doi: 10.1007/s40506-014-0021-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Helou G., Razonable R.R. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019;12:1481–1491. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S180908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papanicolaou G.A., Silveira F.P., Langston A.A., Pereira M.R., Avery R.K., Uknis M., Wijatyk A., Wu J., Boeckh M., Marty F.M., Villano S. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019;68:1255–1264. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piret J., Boivin G. Antiviral Res. 2019;163:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novikov M.S., Babkov D.A., Paramonova M.P., Khandazhinskaya A.L., Ozerov A.A., Chizhov A.O., Andrei G., Snoeck R., Balzarini J., Seley-Radtke K.L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:4151–4157. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babkov D.A., Khandazhinskaya A.L., Chizhov A.O., Andrei G., Snoeck R., Seley-Radtke K.L., Novikov M.S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:7035–7044. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maruyama T., Kozai S., Yamasaki T., Witvrouw M., Pannecouque C., Balzarini J., Snoeck R., Andrei G., De Clercq E. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2003;14:271–279. doi: 10.1177/095632020301400506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maruyama T., Demizu Y., Kozai S., Witvrouw M., Pannecouque C., Balzarini J., Snoecks R., Andrei G., De Clercq E. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2007;26:1553–1558. doi: 10.1080/15257770701545424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novikov M.S., Valuev-Elliston V.T., Babkov D.A., Paramonova M.P., Ivanov A.V., Gavryushov S.A., Khandazhinskaya A.L., Kochetkov S.N., Pannecouque C., Andrei G., Snoeck R., Balzarini J., Seley-Radtke K.L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:1150–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paramonova M.P., Khandazhinskaya A.L., Ozerov A.A., Kochetkov S.N., Snoeck R., Andrei G., Novikov M.S. Acta Nat. 2020;12:134–139. doi: 10.32607/actanaturae.10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paramonova M.P., Snoeck R., Andrei G., Khandazhinskaya A.L., Novikov M.S. Mendeleev Commun. 2020;30:602–603. doi: 10.1016/j.mencom.2020.09.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker B.R., Kelley J.L. J. Med. Chem. 1970;13:458–461. doi: 10.1021/jm00297a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]