Abstract

Metabolically labile prodrugs can experience stark differences in catabolism incurred by the chosen route of administration. This is especially true for phosph(on)ate prodrugs, in which successive promoiety removal transforms a lipophilic molecule into increasingly polar compounds. We previously described a phosphonate inhibitor of enolase (HEX) and its bis-pivaloyloxymethyl ester prodrug (POMHEX) capable of eliciting strong tumor regression in a murine model of enolase 1 (ENO1)-deleted glioblastoma following parenteral administration. Here, we characterize the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of these enolase inhibitors in vitro and in vivo after oral and parenteral administration. In support of the historical function of lipophilic prodrugs, the bis-POM prodrug significantly improves cell permeability of and rapid hydrolysis to the parent phosphonate, resulting in rapid intracellular loading of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro and in vivo. We observe the influence of intracellular trapping in vivo on divergent pharmacokinetic profiles of POMHEX and its metabolites after oral and parenteral administration. This is a clear demonstration of the tissue reservoir effect hypothesized to explain phosph(on)ate prodrug pharmacokinetics but has heretofore not been explicitly demonstrated.

Keywords: prodrugs, phosphonate, phosphate, glycolysis, cancer, mouse models

Phosph(on)ate-containing pharmacophores represent a clinically transformative subset of all FDA-approved drugs.1 Due to their dianionic character, phosphonate-containing drugs typically suffer from poor oral bioavailability and rapid renal clearance;2 prodrug modifications are consequently appended to improve their lipophilicity which, in turn, improves these properties.3,4 Prominent examples of phosphonate prodrugs include adefovir dipivoxil, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF).5 For such esterase-labile prodrugs, susceptibility to first-pass metabolism results in systemic circulation of anionic metabolite intermediate(s),6 which can enter cells via endocytosis.7−9 Because the historical purpose of phosphonate prodrugs has been to improve oral absorption of the parent phosphonate,10 few studies have evaluated differences in pharmacology and therapeutic activity between the orally and parenterally administered prodrug. Most studies compare the pharmacokinetic profile of the parent phosphonate following oral administration of the prodrug relative to that achieved by intravenous (IV) administration of the parent phosphonate, with the goal of identifying promoieties that maximize systemic drug exposure to the parent phosphonate.3,11

We previously reported the synthesis and antineoplastic activity of 1-hydroxy-2-oxopiperidin-3-yl)phosphonate (HEX), an enolase 2 (ENO2)-preferred inhibitor for the targeted treatment of cancers harboring ENO1-homozygous deletions, such as a subset of glioblastomas (GBMs).12,13 Against glioma cells in culture, HEX exhibited selective toxicity to ENO1–/– cells in the micromolar range (D423; 1.3 μM) compared to ENO1 isogenically (D423 ENO1) rescued or ENO1-wild-type (WT; LN319, > 300 μM) cell lines. Recognizing the poor cell permeability of HEX, we synthesized and evaluated the in vitro activity of a lipophilic a bis-pivaloyloxymethyl (POM) prodrug (POMHEX) with the primary intention of improving cell permeability, rather than the oral bioavailability.12,14 Both HEX and POMHEX were synthesized and evaluated as racemates. While we have previously shown that this family of phosphonate inhibitors preferentially binds ENO2 in the S configuration,15 HEX racemizes at physiological pH due to the low pKa of the Cα proton.

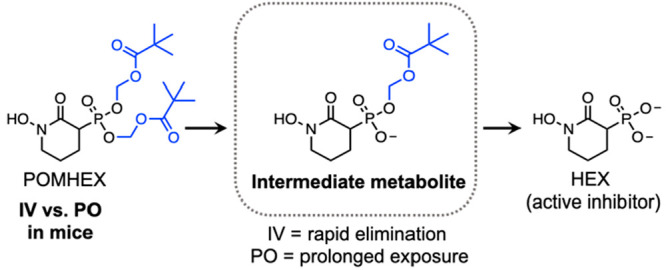

Here, we characterize the in vivo pharmacokinetics of HEX and POMHEX after parenteral and oral administration in mice. The marked divergence in pharmacokinetics between the parenteral and oral routes can be attributed to complex pharmacology of phosph(on)ate prodrugs, which are lipophilic when intact before being bioconverted to increasingly anionic metabolites. In contrast to metabolically inert drugs, this switch in physiochemical properties can result in intracellular trapping and the formation of tissue-specific drug reservoirs, which influences the half-life (t1/2) of the parent phosphonate due to slow systemic release over time.16 The influence of route of administration on the formation of tissue-specific drug reservoirs and t1/2 of the parent pharmacophore has been made for separate phosphate prodrugs—namely remdesivir (administered IV) and sofosbuvir (administered PO).17,18 Here we report the oral and parenteral pharmacokinetics for POMHEX; our data support the plausibility of the tissue reservoir hypothesis, which has been used to explain the long t1/2 of the parent pharmacophores observed for this class of compounds.

Results and Discussion

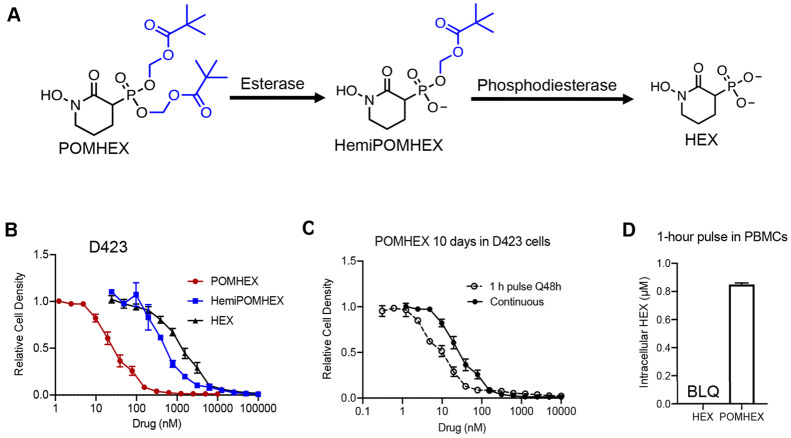

We previously showed that a subset of cancers harboring homozygous deletion of the glycolytic enzyme enolase 1 (ENO1) are exceptionally sensitive to pharmacological inhibition of the paralogous isoform, ENO2.12,13,19 HEX is substrate competitive with the enolase natural substrate, 2-phosphoglycerate, and displays approximately 4-fold specificity for ENO2 over ENO1 (Ki = 64 versus 232 nM). However, HEX is a dianion at physiological pH and is thus poorly cell permeable. We initially synthesized POMHEX, a bis-POM prodrug, to mask the phosphonate negative charge and improve the cellular permeability of HEX. Upon cellular entry, the POM esters are removed first by carboxylesterases and then phosphodiesterases to generate the active agent, HEX (Figure 1a).20,21 Owing to their divergent lipophilicities, POMHEX exhibits approximately 50-fold greater potency against ENO1–/– cells (D423) in culture compared to HEX (IC50 ∼ 0.03 vs 1.3 μM; Figure 1b). In concurrence, the intermediate mono-POM ester metabolite, HemiPOMHEX, exhibits ∼10-fold lower potency compared to POMHEX against ENO1–/– cells, with an IC50 of approximately 0.3 μM (Figure 1a). The ubiquity of plasma esterases makes esterase-labile prodrugs such as POMHEX susceptible to premature hydrolysis to HemiPOMHEX.11,22,23 As a consequence of transient in vivo exposure to POMHEX, we sought to examine the influence of pulsed versus continuous treatment on the in vitro potency of POMHEX (Figure 1c). Cells were pulsed with POMHEX for 1 h, every 48 h, for 10 days. During a pulse, cells were incubated in drug-containing media for 1 h; media was then removed, and cells were incubated in drug-free media for 48 h. This cycle was repeated for 10 days, resulting in a total of 5 drug pulses. The IC50 of POMHEX was similar across pulsed and continuous treatments (IC50 = 9.3 vs 28.9 nM, Figure 1c), indicating rapid, efficient cellular permeation and intracellular bioactivation of POMHEX despite short exposure.

Figure 1.

POMHEX is an esterase-labile prodrug that is susceptible to intracellular and plasma hydrolysis to an anionic intermediate, HemiPOMHEX, which can be further hydrolyzed to the active pharmacophore HEX. (B) Dose–response curves for ENO1-deleted the cells (D423) treated with either POMHEX (red, IC50 = 28.9 nM), HemiPOMHEX (blue, IC50 = 561 nM), or HEX (black, IC50 = 1342 nM). Increasing lipophilicity enables efficient cellular permeation and potency in vitro. Calculated IC50 values are the mean ± SD of N ≥ 16 for POMHEX and HEX and mean ± SD of N ≥ 2 for HemiPOMHEX. (C) Pulsed (open circle) or continuous treatment (black circle) with POMHEX results in similar the IC50 values in D423 cells (9.3 vs 28.9 nM). Values are mean ± SD of N ≥ 2 for pulsed and N ≥ 16 for continuous treatment. For pulsed treatment, cells were incubated with drug-containing media for 1 h, which was then replaced with drug-free media for 48 h. This cycle was repeated a total of 5 times during the 10-day treatment course. For continuous treatment, cells were incubated with drug-containing media for 10 days, without media replacement. (D) Intracellular concentrations of HEX in PBMCs after a 1-h pulse of HEX (100 μM) and POMHEX (600 nM). Despite being treated with 167-fold higher concentration of HEX, levels are below the limit of detection after 1 h (N = 5 per drug). Intracellular concentrations of HEX after POMHEX treatment are 0.85 ± 0.01 μM, indicating rapid prodrug bioactivation. BLQ = below limit of quantification.

We previously confirmed on-target effects of enolase inhibition, by examining the metabolomic profile of cells treated with POMHEX relative to controls after 72 h of treatment. Enolase-deficient cell lines displayed dose-dependent elevations in metabolites immediately upstream (3-phosphoglycerate) and decreases in metabolites downstream (lactate) of the enolase reaction.12 At lower concentrations of POMHEX, these effects were more acutely observed in ENO1–/– cells (D423) compared to ENO1+/- cells (D502 and U343). In contrast, no dose-dependent metabolic changes were observed in ENO1-WT cells (D423 ENO1, LN319). These metabolomic data support the relationship between ENO1-deletion status and sensitivity to POMHEX and corroborate previous observations made with pan-enolase inhibitors.13,24 Supportive of rapid prodrug removal on POMHEX, we found that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) pulsed for 1 h with POMHEX (600 nM) produced intracellular concentrations of HEX 0.85 ± 0.01 μM; in contrast, the direct administration of HEX (100 μM) failed to produce levels above detection threshold (Figure 1d). These data support efficient cell permeation endowed by the lipophilic bis-POM prodrug and on-target inhibition of enolase consistent with previous reports with esterase-labile phosph(on)ate prodrugs.25,26

In the field of antivirals, esterase-labile POM (or its isopropyloxycarbonyloxymethyl, POC, counterpart) prodrugs have typically been employed to improve the oral bioavailability of the parent phosph(on)ate nucleotide analogue by masking the negative charge—thereby improving lipophilicity.4,20,27 The majority of esterase-labile phosph(on)ate prodrugs evaluated in the clinic have been administered as oral agents.5,28,29 A series of McGuigan prodrugs (ProTides) of 3′deoxyadenosine, 5-fluorouracil, and gemcitabine, are currently being evaluated as IV therapies for solid tumors (NCT03829254, NCT03428958, NCT03146663). However, there have been no published studies comparing the in vivo PK or activity of an orally versus parenterally administered phosph(on)ate prodrug.

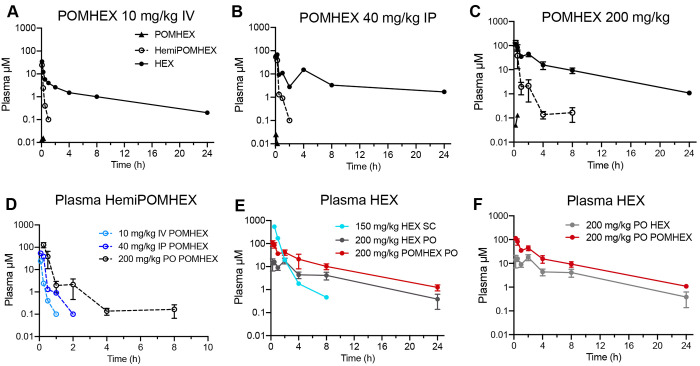

We evaluated the single dose PK of POMHEX and the parent HEX in mice following parenteral and oral administration. Parenteral administration of POMHEX (IV at 10 mg/kg or IP at 40 mg/kg) demonstrated similar decay kinetics of POMHEX, HemiPOMHEX, and HEX, as indicated by their similar tmax and t1/2 values (Figure 2a-c; Table 1). Expectedly, both IV and IP administration resulted in rapid plasma hydrolysis of POMHEX to HemiPOMHEX and HEX, which were both readily detected at 5 min. HemiPOMHEX exhibited a transient t1/2 of less than 30 min while the parent phosphonate HEX exhibited a t1/2 of approximately 7 h and a C24 of 0.20 μM (IV) and 1.7 μM (IP). Following IV administration of POMHEX at 10 mg/kg, HemiPOMHEX had a Cmax value 24.2 μM at a tmax of 0.08 h and an AUC0–24 of 2.96 μM*h. HEX had a Cmax value 34.7 μM at a tmax of 0.08 h and an AUC0–24 29.7 μM*h. Following IP administration of POMHEX at 40 mg/kg, HemiPOMHEX had a Cmax value of 54.1 μM at a tmax of 0.08 h and an AUC0–24 of 13.6 μM*h. HEX had Cmax value of 68.0 μM at a tmax value of 0.08 h and an AUC0–24 of 120 μM*h.

Figure 2.

In vivo pharmacokinetics of POMHEX and its metabolites in mice. Plasma PK profiles of POMHEX (black triangles), HemiPOMHEX (open circle), and HEX (black circle) after (A) 10 mg/kg IV, (B) 40 mg/kg IP, (C) 200 mg/kg PO. Data presented as the means of N ≥ 3. Irrespective of administration route, exposure to POMHEX is transient due to its esterase-labile nature. (D) Focused view comparing the plasma PK of HemiPOMHEX after oral (black), IV (light blue), and IP (blue) administration of POMHEX. (E) Plasma concentrations of HEX after direct SC administration at 150 mg/kg (aqua), direct oral administration at 200 mg/kg (gray), or after oral administration of POMHEX at 200 mg/kg (red). Oral administration of POMHEX improves the bioavailability of HEX compared to direct oral administration, but decay kinetics remain similar (see Table 1). (F) Focused view comparing plasma PK of HEX after oral administration of either 200 mg/kg POMHEX (red) or 200 mg/kg HEX (gray).

Table 1. Summary of In Vivo Pharmacokinetics of Metabolites in Mice after Administration of Either POMHEX or HEXa.

| route | AUC0–24 (μM·h) | Cmax (μM) | tmax (h) | t1/2 (h) | C8 (μM)a | C24 (μM)b | F%c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HemiPOMHEX | |||||||

| IV (10 mg/kg) | 2.96 | 24.2 | 0.08 | 0.17 | BLQ | BLQ | |

| IP (40 mg/kg) | 13.6 | 54.1 | 0.08 | 0.39 | BLQ | BLQ | |

| PO (200 mg/kg) | 45.0 | 129 | 0.25 | 1.15 | 0.16 | BLQ | |

| HEX (from POMHEX) | |||||||

| IV (10 mg/kg) | 29.7 | 34.7 | 0.08 | 6.88 | 1 | 0.20 | |

| IP (40 mg/kg) | 120 | 68.0 | 0.08 | 7.69 | 3.3 | 1.7 | |

| PO (200 mg/kg) | 301 | 114 | 0.25 | 5.22 | 9.3 | 1.1 | 52 |

| HEX (administered directly) | |||||||

| SC (150 mg/kg) | 437 | 540 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.46 | BLQ | |

| PO (200 mg/kg) | 86.6 | 18.1 | 2.0 | 5.34 | 4.13 | 0.38 | 15 |

C8 = plasma concentration at 8 h postdose.

C24 = plasma concentration at 24 h postdose. BLQ = below limit of quantification.

Relative to 150 mg/kg HEX SC.

Single dose oral administration of POMHEX (200 mg/kg) resulted in a markedly different plasma PK profile (Figure 2c). POMHEX was undetectable in plasma after 30 min, indicating extensive first-pass metabolism and plasma hydrolysis to its downstream metabolites. The PK behavior of HemiPOMHEX diverged significantly from that observed from parenteral administration, exhibiting an extended t1/2 of 1.15 h. The Cmax of HemiPOMHEX was 129 μM at a tmax of 0.25 h and an AUC0–24 of 45 μM*h. Compared to parenteral administration of POMHEX, in which HemiPOMHEX was undetectable after 1 h, oral administration of POMHEX resulted in a C8 value of HemiPOMHEX of 0.16 μM (Table 1). As a downstream metabolite, HEX exhibited a similar PK profile as that observed for parenterally administered POMHEX, with a t1/2 of approximately 5 h and a C24 of 1.1 μM. The discordant PK profile of HemiPOMHEX after IV/IP and oral administration can likely be explained by the formation of a hepatic drug reservoir upon first-pass metabolism, which has been observed for other the intermediate metabolites of other phosph(on)ate prodrugs following oral administration.29,30 High levels of carboxylesterases in hepatocytes result in rapid hydrolysis of esterase-labile promoieties on POMHEX or the alaninate ester on the McGuigan prodrugs sofosbuvir and fostmetpantotenate.11,17,29 In all cases, the resulting anionic intermediate metabolite is intracellularly trapped and forms a drug reservoir, which explains the slow hepatic release and prolonged systemic exposure of HemiPOMHEX that is not observed during parenteral administration (Figure 2d).16,31

The PK of HEX after parenteral (SC at 150 mg/kg) and oral (200 mg/kg) exhibited distinct decay kinetics (Figure 2e, Table 1). Following SC administration, a plasma Cmax value of 540 μM was observed at the earliest measured time point (tmax = 0.5 h) and fell below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) by 8 h postdose (0.46 μM). HEX exhibited a plasma t1/2 of 0.5 h after SC administration. It should be noted that HEX was quantified in plasma by integrating the positive spectral projections of 1H–31P HSQC NMR spectrum in the SC study due to the hazards associated with the derivatizing agent trimethylsilyl-diazomethane (TMS-DAM) required to detect HEX by reverse-phase ultra high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC).32 All other studies described herein quantified HEX by derivatization and UHPLC (see Methods). Due to the lower sensitivity of the NMR-based method, it is quite likely that the C24 of HEX is nonzero, especially considering the LLOQ using the UHPLC-based method is 0.1 μM. Consequently, the AUC0–24 is likely longer than the 437 μM*h calculated. Following oral administration, HEX exhibited a Cmax of 18.1 μM at a tmax of 2 h. The C24 of HEX was found to be 0.38 μM, resulting in an AUC0–24 of 86.6 μM*h. Based on these PK values, the calculated F% of HEX relative to SC administration is approximately 15%. The low F% of HEX can partly be attributed to rapid clearance, as we had observed across other preclinical species, and for phosphonate pharmacophores more generally.10,33,34 When POMHEX is orally administered, the F% of HEX improves to 52%, which supports the historical function of lipophilic ester promoieties for improving the bioavailability of the parent phosphonate.11,23

We also assessed the pharmacodynamics of HEX (500 mg/kg PO) and POMHEX (100 mg/kg PO) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) 1-h post oral administration (N = 5; Table 2). While levels of HEX were quantifiable (0.23 ± 0.05 μM) after oral administration of POMHEX, levels were below the limit of quantification after oral administration of HEX. This discordance can be explained by the intermediate lipophilicity of HemiPOMHEX, which is present after oral POMHEX administration, and the inefficient cellular permeability of plasmatic HEX in the latter case (Figure 2). These in vivo data recapitulate our observations in isolated PBMCs in vitro, supporting the inefficient permeability of the free phosphonate.

Table 2. In Vivo Pharmacodynamics of POMHEX and HEX in PBMCs after Oral Administration in Micea.

| 1-h

postdose (N = 5) |

||

|---|---|---|

| POMHEX (100 mg/kg) | HEX (500 mg/kg) | |

| HemiPOMHEX (μM) | ||

| PBMC | BLQ | — |

| plasma | 1.51 ± 0.67 | — |

| HEX (μM) | ||

| PBMC | 0.23 ± 0.05 | BLQ |

| plasma | 41.8 ± 10.3 | 82.9 ± 32.3 |

BLQ = below limit of quantification.

Historically, the primary function of phosph(on)ate prodrugs has been to improve oral bioavailability of the parent phosph(on)ate by enhancing lipophilicity.35−37 Our data support this function but also show that the fate of the intermediate metabolite should be considered after oral versus parenteral administration of the intact lipophilic prodrug. Parenterally administered POMHEX yielded 2.5–10-fold lower plasmatic concentrations of HEX (AUC0–24: 29.7–120 μM*h vs 301 μM*h), and 3–10-fold lower plasmatic concentrations of HemiPOMHEX (AUC0–24 2.96–13.5 μM*h vs 45.0 μM*h) compared to direct oral administration of HEX (Table 1). The extent to which intact POMHEX or the intermediate metabolite, HemiPOMHEX, may contribute to the therapeutic activity in ENO1–/– intracranial tumors in mice previously reported by our group is unclear. However, the high lipophilicities of both POMHEX and HemiPOMHEX results in improved cell and tissue permeabilities, which may suggest a nonzero therapeutic contribution despite transient plasmatic exposure. This rationale is supported by similar IC50 values observed after treating ENO1–/– cells with a 1-h pulse and 5-day incubation—indicating rapid cellular permeation and promoiety removal to the active HEX pharmacophore (Figure 1c).12 Additionally, PBMCs treated with a 1-h pulse of POMHEX at 600 nM resulted in intracellular concentrations of HEX at 0.85 ± 0.01 μM; in contrast, a 1-h pulse with HEX at 100 μM did not produce intracellular levels above detection threshold (Figure 1d). The observed ability for HemiPOMHEX to also produce detectable levels of HEX in PBMCs (0.23 ± 0.05 μM) 1-h after oral administration of POMHEX (100 mg/kg) also supports the influence of lipophilicity on efficient cell permeability, even with transient plasmatic exposure; in contrast, oral administration of HEX (500 mg/kg) did not yield detectable levels of HEX in PBMCs, despite producing approximately 2-fold higher levels of HEX in plasma (Table 2).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly compare the PK profiles of a phosphonate prodrug after oral and parenteral administration. Previous studies have evaluated the oral PK and oral bioavailability of phosphonate prodrugs relative to parenteral administration of the phosphonate pharmacophore.4,38,39 IV administration of lipophilic phosph(on)ate prodrugs is atypical, and currently the only FDA-approved drug for humans in this category is remdesivir.40 A series of nucleotide prodrugs are currently under clinical evaluation for the treatment of solid cancers.28,41,42 However, for both remdesivir and these investigational nucleotide prodrugs, comparisons of the oral versus IV PK have not been reported.

From our comparative route of administration study, our data support the influence of tissue (pro)drug reservoirs incurred by route of administration.16 This is most clearly demonstrated by the fate of the prodrug intermediate HemiPOMHEX after parenteral versus oral administration of POMHEX, in which intrahepatic levels of the latter likely explains the longer t1/2 (Figure 2d). There are few reports on the influence of the intermediate metabolites of phosph(on)ate prodrugs such as TDF and TAF on the overall therapeutic activity of these prodrugs.6,31 Our data on HemiPOMHEX support the ability for intermediate prodrug metabolites to permeate cells, even with transient exposure in vitro or in vivo (Table 2). By directly comparing the PK of POMHEX after parenteral and oral administration, our study demonstrates the influence of route of administration on the therapeutic efficacy of phosph(on)ate prodrugs, a pharmacokinetically complex class of molecules. These data can inform development strategies for other phosph(on)ate prodrugs in the future.

Methods

Synthesis

POMHEX, HemiPOMHEX, and HEX were synthesized according to previously published procedures.12

Cell-Based Evaluation of Enolase Inhibitor Activity

The in vitro activity of POMHEX, HemiPOMHEX, and HEX was evaluated according to previously published procedures.12,43 Briefly, cell culture experiments performed in the 3-cell line assay were conducted in 96-well plates. Plates were seeded at approximately 15% confluence (103 cells per well). Cancer cells were attached for 24 h and were treated with fresh medium containing prodrug inhibitor. Treatment with enolase inhibitor prodrug proceeded for 6 days unless otherwise noted. Plates were then washed with PBS and fixed with 10% formalin. Fixed plates were stained with 0.1% crystal violet and quantified by acetic acid extraction with spectrophotometric absorption at 595 nm in a plate reader. Cell densities were expressed relative to nondrug, medium-only wells. All experiments were conducted in DMEM medium with 4.5 g/L glucose, 110 mg/L pyruvate, and 584 mg/L glutamine (Cellgro/Corning no. 10-013-CV) with 10% FBS (Gibco/Life Technologies no. 16140-071) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco/Life Technologies no. 15140-122) and 0.1% amphotericin B (Gibco/Life Technologies no. 15290–018).

Intracellular Metabolism of POMHEX and HEX in Human PBMCs in Vitro

The intracellular metabolism of POMHEX and HEX was evaluated in PBMCs. PBMCs were incubated in suspension (approximately 1 × 107 cells per sample, N = 5) in 1 mL of media. Then, cells were pulsed for 1 h with either POMHEX (600 nM) or HEX (100 μM). Samples were then centrifuged at 2500g for 30 s to remove drug-containing media. Cells were lysed in 80% methanol (300 μL) for analysis by LC-MS/MS.

Drug Formulation for In Vivo Studies

For parenteral PK studies (IV/IP for POMHEX, SC for HEX), POMHEX was formulated in a 2% DMSO/PBS solution for a final dose of 10 mg/kg (IV) or 40 mg/kg (IP). HEX was dissolved in water and the pH was adjusted to 7 using sodium hydroxide. The final volume of drug-containing solutions was approximately 200 μL. For oral PK studies, POMHEX was formulated in 20% sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin in water solution and administered at 5 mL/kg for a final dose of 100 mg/kg; HEX was formulated in 0.5% methylcellulose solution and administered at 10 mL/kg for a final dose of 500 mg/kg.

Single-Dose Pharmacokinetics of POMHEX and HEX

For parenteral PK, female Foxn1nu/nu mice (N = 3 per group) were administered either POMHEX (10 mg/kg IV or 40 mg/kg IP) or HEX (150 mg/kg SC). For oral PK, female NSG mice (N = 5 per drug) were administered either POMHEX (100 mg/kg) or HEX (500 mg/kg) PO. At predetermined time points (POMHEX: 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 h postdose, HEX: 0.25 (PO only) 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 h postdose), mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and blood was collected via cardiac puncture. Blood (∼250 μL) was first collected in EDTA-coated tubes (Terumo, cat #: T-MQK) and then transferred to Eppendorf tubes (150 μL for plasma PK and 100 μL for PBMC isolation). For plasma PK, tubes were centrifuged at 2000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The plasma supernatant was isolated, snap frozen, and stored at −80 °C until PK analysis.

Intracellular Metabolism of POMHEX and HEX in PBMCs after Oral Treatment in Mice

Following the procedure described above, female NSG mice (N = 5 per drug) were administered either POMHEX (100 mg/kg) or HEX (500 mg/kg) PO. At 1-h postdose, blood samples were collected as described above. Whole blood (∼100 μL) was diluted with 1 volume of PBS and added to an equal volume of Ficoll-Paque solution. The solution was then centrifuged for 30 min at 500g. The PBMC layer was isolated, and cells were lysed using 80% methanol (300 μL) for analysis by LC-MS/MS.

Sample Preparation and Derivatization of Prodrug Metabolites for LC-MS/MS Analysis

The following procedure was used for preparation of both cell lysate and plasma samples. For POMHEX, 25 μL of sample including the analytical standards and quality controls (QCs) were mixed with 200 μL of MeCN. After vortex and centrifugation, 100 μL of the supernatant was mixed with 100 μL of water for LC-MS/MS analysis. For anionic metabolites HemiPOMHEX and HEX, derivatization was required for LC-MS/MS analysis: 50 μL of sample, which also contained standards and QCs, were diluted with 500 μL of 10 mM aqueous NH4HCO3 containing a benzylated HEX precursor12 (BnHEX; 0.015 μM, internal standard), loaded onto a Waters Oasis MAX SPE cartridge (30 mg) which was preconditioned with methanol (1 mL) and water (1 mL). The cartridge was washed with water (1 mL) and methanol (1 mL), and the analytes were derivatized on the cartridge with 200 μL of 2.0 M solution of trimethylsilyl-diazomethane in hexane (TMS-DAM, Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h to obtain TMS-derivatized HemiPOMHEX and HEX. The derivatized analytes in the cartridge was eluted with methanol (1 mL), evaporated to dryness at 40 °C under a stream of nitrogen, and reconstituted with 150 μL of 0.1% formic acid in water/MeCN (2:1) for LC-MS/MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS Analysis of POMHEX and Metabolites

Samples were analyzed on an Agilent 1290 infinity binary LC/HTC injector coupled with a Sciex 5500 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer operated on positive mode. The mass spec source conditions were set for all the analytes as the following: ion spray voltage (5500 V), curtain gas (35), collision gas (8), gas temperature (500 °C), ion source gas 1 (40), ion source gas 2 (60), DP (156), EP (10), CE (27), CXP (10). The LC mobile phase A was 0.1% acetic acid–water and B was 0.1% acetic acid/MeCN. The LC flow rate was 0.5 mL/min, and the injection volume was 2 μL. The column temperature was set to 40 °C. TMS-derivatized HEX was separated using a Phenomenex Luna C8 (3 μm, 2.0 × 50 mm) column (Torrance, CA). The multiple reaction monitoring transition was 238.1 > 207.0 (TMS-HEX) and 313.9 > 91.1 (TMS-BnHEX, IS), respectively. The LC gradient was 5% B (0–0.3 min), 5–95% B (0.3–1.5 min), 95% B (1.5–2 min), 95–22% (2–2.1 min), 22% B (2.1–2.3 min). Under these conditions, the retention time was 0.97 min (TMS-HEX), 1.30 min (TMS-HemiPOMHEX), and 1.26 min (TMS-BnHEX), respectively. The method was validated with an analytical range of 0.1–5 μM for both HemiPOMHEX and HEX in untreated Foxn1nu/nu mouse plasma. PK parameters were determined using Phoenix NonWinlin 7.0, and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

NMR Quantification of HEX in Plasma

Analysis of HEX in plasma was performed as previously described.33

Acknowledgments

We thank Kumar Kalurachchi for assistance with NMR studies. The MD Anderson Cancer Center NMR Core Facility is supported in part by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CA16672). Y.B. is supported by the CPRIT Research Training Grant (RP210028), the Dr. John J. Kopchick Fellowship, and the Schissler Foundation. This work was funded by research grants from the American Cancer Society (RSG-15-145-01-CDD; F.L.M.), National Comprehensive Cancer Network (YIA170032; F.L.M.), Andrew Sabin Family Foundation (F.L.M.), Dr. Marnie Rose Foundation (F.L.M.), Uncle Kory Foundation (F.L.M.), University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Research Grant (F.L.M.), and the NIH (R01 CA231509-01A1; S.W.M.).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsptsci.2c00216.

Author Contributions

N.S., N.H., K.A., and D.K.G. performed in vitro inhibitor efficacy studies. Y.-H.L., K.A., and Y.J. performed in vivo studies. Y.B., and Y.S. performed pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies. V.C.Y. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. V.C.Y. and F.L.M. conceived of the study. V.C.Y., S.W.M., J.R.M. and F.L.M. oversaw the study.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): F.L.M., V.C.Y., E.S.B., K.L.Y., and C.-D.P., are inventors on a patent describing compounds included in this work (WO/2020/154742). V.C.Y., C.-D.P., and F.L.M. are inventors on a patent describing methods of preparation for compounds included in this work (US 63/004,063). F.L.M., F.P., B.C., Y.-H.L., and N.S., are inventors on a patent describing the concept of targeting ENO1-deleted cancers with inhibitors of ENO2 (US 10,363,261). F.L.M. is an inventor on a separate patent describing the concept of targeting ENO1-deleted tumors with inhibitors of ENO2 (US 9,452,182 B2).

Supplementary Material

References

- Rautio J.; Meanwell N. A.; Di L.; Hageman M. J. The Expanding Role of Prodrugs in Contemporary Drug Design and Development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2018, 17 (8), 559–587. 10.1038/nrd.2018.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy S. A.; Hitchcock M. J. M.; Lee W. A.; Tellier P.; Cundy K. C.; Lacy S. A.; Hitchcock M. J. M.; Lee W. A.; Tellier P.; Cundy K. C. Effect of Oral Probenecid Coadministration on the Chronic Toxicity and Pharmacokinetics of Intravenous Cidofovir in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Toxicol. Sci. 1998, 44 (2), 97–106. 10.1006/toxs.1998.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starrett J. E. J. Jr.; Tortolani D. R.; Russell J.; Hitchcock M. J. M.; Whiterock V.; Martin J. C.; Mansuri M. M. Synthesis, Oral Bioavailability Determination, and in Vitro Evaluation of Prodrugs of the Antiviral Agent 9-[2-(Phosphonomethoxy)Ethyl]Adenine (PMEA). J. Med. Chem. 1994, 37 (12), 1857–1864. 10.1021/jm00038a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cundy K. C.; Sueoka C.; Lynch G. R.; Griffin L.; Lee W. A.; Shaw J.-P. Pharmacokinetics and Bioavailability of the Anti-Human Immunodeficiency Virus Nucleotide Analog 9-[(R)-2-(Phosphonomethoxy)Propyl]Adenine (PMPA) in Dogs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42 (3), 687–690. 10.1128/AAC.42.3.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradere U.; Garnier-Amblard E. C.; Coats S. J.; Amblard F.; Schinazi R. F. Synthesis of Nucleoside Phosphate and Phosphonate Prodrugs. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (18), 9154–9218. 10.1021/cr5002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks K. M; Ibrahim M. E; Castillo-Mancilla J. R; MaWhinney S.; Alexander K.; Tilden S.; Kerr B. J.; Ellison L.; McHugh C.; Bushman L. R; Kiser J. J; Hosek S.; Huhn G. D; Anderson P. L Pharmacokinetics of Tenofovir Monoester and Association with Intracellular Tenofovir Diphosphate Following Single-Dose Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74 (8), 2352–2359. 10.1093/jac/dkz187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsanska L.; Cihlar T.; Votruba I.; Holy A. Transport of Adefovir (PMEA) in Human T-Lymphoblastoid Cells. Collect. Czechoslov. Commun. 1997, 62, 821–828. 10.1135/cccc19970821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palu G.; Stefanelli S.; Rassu M.; Parolin C.; Balzarini J.; De Clercq E. Cellular Uptake of Phosphonylmethoxyalkylpurine Derivatives. Antiviral Res. 1991, 16 (1), 115–119. 10.1016/0166-3542(91)90063-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneva E.; Crooker K.; Park S. H.; Su J. T.; Ott A.; Cheshenko N.; Szleifer I.; Kiser P. F.; Frank B.; Mesquita P. M. M.; Herold B. C. Differential Mechanisms of Tenofovir and Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Cellular Transport and Implications for Topical Preexposure Prophylaxis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60 (3), 1667–1675. 10.1128/AAC.02793-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby S. A.; Dowd C. S. Phosphoryl Prodrugs: Characteristics to Improve Drug Development. Med. Chem. Res. 2022, 31 (2), 207–216. 10.1007/s00044-021-02766-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naesens L.; Bischofberger N.; Augustijns P.; Annaert P.; Van den Mooter G.; Arimilli M. N.; Kim C. U.; De Clercq E. Antiretroviral Efficacy and Pharmacokinetics of Oral Bis(Isopropyloxycarbonyloxymethyl)-9-(2-Phosphonylmethoxypropyl)Adenine in Mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42 (7), 1568–1573. 10.1128/AAC.42.7.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.-H.; Satani N.; Hammoudi N.; Yan V. C.; Barekatain Y.; Khadka S.; Ackroyd J. J.; Georgiou D. K.; Pham C.-D.; Arthur K.; Maxwell D.; Peng Z.; Leonard P. G.; Czako B.; Pisaneschi F.; Mandal P.; Sun Y.; Zielinski R.; Pando S. C.; Wang X.; Tran T.; Xu Q.; Wu Q.; Jiang Y.; Kang Z.; Asara J. M.; Priebe W.; Bornmann W.; Marszalek J. R.; DePinho R. A.; Muller F. L. An Enolase Inhibitor for the Targeted Treatment of ENO1-Deleted Cancers. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 1413–1426. 10.1038/s42255-020-00313-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller F. L.; Colla S.; Aquilanti E.; Manzo V. E.; Genovese G.; Lee J.; Eisenson D.; Narurkar R.; Deng P.; Nezi L.; Lee M. A.; Hu B.; Hu J.; Sahin E.; Ong D.; Fletcher-Sananikone E.; Ho D.; Kwong L.; Brennan C.; Wang Y. A.; Chin L.; DePinho R. A. Passenger Deletions Generate Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in Cancer. Nature 2012, 488, 337–342. 10.1038/nature11331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan V. C.; Pham C.-D.; Ballato E. S.; Yang K. L.; Arthur K.; Khadka S.; Barekatain Y.; Shrestha P.; Tran T.; Poral A. H.; Washington M.; Raghavan S.; Czako B.; Pisaneschi F.; Lin Y.-H.; Satani N.; Hammoudi N.; Ackroyd J. J.; Georgiou D. K.; Millward S. W.; Muller F. L. Prodrugs of a 1-Hydroxy-2-Oxopiperidin-3-Yl Phosphonate Enolase Inhibitor for the Treatment of ENO1-Deleted Cancers. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65 (20), 13813–13832. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisaneschi F.; Lin Y.-H.; Leonard P. G.; Satani N.; Yan V. C.; Hammoudi N.; Raghavan S.; Link T. M.; Georgiou D. K.; Czako B.; Muller F. L. The 3S Enantiomer Drives Enolase Inhibitory Activity in SF2312 and Its Analogues. Molecules 2019, 24 (13), 2510. 10.3390/molecules24132510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang R.; Barth A.; Wong H.; Marik J.; Shen J.; Lade J.; Grove K.; Durk M. R.; Parrott N.; Rudewicz P. J.; Zhao S.; Wang T.; Yan Z.; Zhang D. Design and Measurement of Drug Tissue Concentration Asymmetry and Tissue Exposure-Effect (Tissue PK-PD) Evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65 (13), 8713–8734. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babusis D.; Curry M. P.; Kirby B.; Park Y.; Murakami E.; Wang T.; Mathias A.; Afdhal N.; McHutchison J. G.; Ray A. S. Sofosbuvir and Ribavirin Liver Pharmacokinetics in Patients Infected with Hepatitis C Virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62 (5), 1–11. 10.1128/AAC.02587-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humeniuk R.; Mathias A.; Cao H.; Osinusi A.; Shen G.; Chng E.; Ling J.; Vu A.; German P. Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Remdesivir, An Antiviral for Treatment of COVID-19, in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 10.1111/cts.12840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller F. L.; Aquilanti E. A.; DePinho R. A. Collateral Lethality: A New Therapeutic Strategy in Oncology. Trends in Cancer 2015, 1 (3), 161–173. 10.1016/j.trecan.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J. P.; Sueoka C. M.; Oliyai R.; Lee W. A.; Arimilli M. N.; Kim C. U.; Cundy K. C.; Shaw J. P.; Sueoka C. M.; Oliyai R.; Lee W. A.; Arimilli M. N.; Kim C. U.; Cundy K. C. Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics of Novel Oral Prodrugs of 9-[(R)-2- (Phosphonomethoxy) Propyl]Adenine (PMPA) in Dogs. Pharmaceutical Research 1997, 14, 1824–1829. 10.1023/a:1012108719462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gelder J.; Deferme S.; Naesens L.; De Clercq E.; van den Mooter G.; Kinget R.; Augustijns P. Intestinal Absorption Enhancement of the Ester Prodrug Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate through Modulation of the Biochemical Barrier by Defined Ester Mixtures. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002, 30 (8), 924–930. 10.1124/dmd.30.8.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahar F. G.; Ohura K.; Ogihara T.; Imai T. Species Difference of Esterase Expression and Hydrolase Activity in Plasma. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101 (10), 3979–3988. 10.1002/jps.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J. P.; Louie M.; Krishnamurthy V.; Arimilli M. N.; Jones R. J.; Bidgood A.; Lee W. A.; Cundy K. C.; Shaw J. P.; Louie M.; Krishnamurthy V.; Arimilli M. N.; Jones R. J.; Bidgood A.; Lee W. A.; Cundy K. C. Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of Selected Prodrugs of PMEA in Rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1997, 25 (3), 362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard P. G; Satani N.; Maxwell D.; Lin Y.-H.; Hammoudi N.; Peng Z.; Pisaneschi F.; Link T. M; Lee G. R; Sun D.; Prasad B. A B.; Di Francesco M. E.; Czako B.; Asara J. M; Wang Y A.; Bornmann W.; DePinho R. A; Muller F. L SF2312 Is a Natural Phosphonate Inhibitor of Enolase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12 (12), 1053–1058. 10.1038/nchembio.2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. A.; He G.-X.; Eisenberg E.; Cihlar T.; Swaminathan S.; Mulato A.; Cundy K. C. Selective Intracellular Activation of a Novel Prodrug of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor Tenofovir Leads to Preferential Distribution and Accumulation in Lymphatic Tissue. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49 (5), 1898–1906. 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1898-1906.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackman R. L.; Hui H. C.; Perron M.; Murakami E.; Palmiotti C.; Lee G.; Stray K.; Zhang L.; Goyal B.; Chun K.; Byun D.; Siegel D.; Simonovich S.; Du Pont V.; Pitts J.; Babusis D.; Vijjapurapu A.; Lu X.; Kim C.; Zhao X.; Chan J.; Ma B.; Lye D.; Vandersteen A.; Wortman S.; Barrett K. T.; Toteva M.; Jordan R.; Subramanian R.; Bilello J. P.; Cihlar T. Prodrugs of a 1′-CN-4-Aza-7,9-Dideazaadenosine C-Nucleoside Leading to the Discovery of Remdesivir (GS-5734) as a Potent Inhibitor of Respiratory Syncytial Virus with Efficacy in the African Green Monkey Model of RSV. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64 (8), 5001–5017. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimilli M.; Kim C.; Dougherty J; Mulato A; Oliyai R; Shaw J.; Cundy K.; Bischofberger N Synthesis, in Vitro Biological Evaluation and Oral Bioavailability of 9-[2-(Phosphonomethoxy)Propyl]Adenine (PMPA) Prodrugs. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1997, 8 (6), 557–564. 10.1177/095632029700800610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton P. J.; Kadri H.; Miccoli A.; Mehellou Y. Nucleoside Phosphate and Phosphonate Prodrug Clinical Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (23), 10400–10410. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaum D.; Beconi M. G.; Monteagudo E.; Di Marco A.; Quinton M. S.; Lyons K. A.; Vaino A.; Harper S. Fosmetpantotenate (RE-024), a Phosphopantothenate Replacement Therapy for Pantothenate Kinase-Associated Neurodegeneration: Mechanism of Action and Efficacy in Nonclinical Models. PLoS One 2018, 13 (3), e0192028. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning J.; Cornpropst M.; Flach S. D.; Berrey M. M.; Symonds W. T. Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of GS-9851, a Nucleotide Analog Polymerase Inhibitor for Hepatitis c Virus, Following Single Ascending Doses in Healthy Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57 (3), 1201–1208. 10.1128/AAC.01262-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks K. M; Castillo-Mancilla J. R; Blum J.; Huntley R.; MaWhinney S.; Alexander K.; Kerr B. J.; Ellison L.; Bushman L. R; MacBrayne C. E; Anderson P. L; Kiser J. J Increased Tenofovir Monoester Concentrations in Patients Receiving Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate with Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74 (8), 2360–2364. 10.1093/jac/dkz184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barekatain Y.; Khadka S.; Harris K.; Delacerda J.; Yan V. C.; Chen K.-C.; Pham C.-D.; Uddin M. N.; Avritcher R.; Eisenberg E. J.; Kalluri R.; Millward S. W.; Muller F. L.; Barekatain Y.; Khadka S.; Harris K.; Delacerda J.; Yan V. C.; Chen K.-C.; Pham C.-D.; Uddin M. N.; Avritcher R.; Eisenberg E. J.; Kalluri R.; Millward S. W.; Muller F. L.. Quantification of Phosphonate Drugs by 1H-31P HSQC Shows That Rats Are Better Models of Primate Drug Exposure than Mice. bioRxiv, Feb. 1, 2022, 2022.01.30.478340. 10.1101/2022.01.30.478340. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Barekatain Y.; Khadka S.; Harris K.; Delacerda J.; Yan V. C.; Chen K.-C.; Pham C.-D.; Uddin M. N.; Avritcher R.; Eisenberg E. J.; Kalluri R.; Millward S. W.; Muller F. L. Quantification of Phosphonate Drugs by 1H-31P HSQC Shows That Rats Are Better Models of Primate Drug Exposure than Mice. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94 (28), 10045–10053. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c00553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks S. G.; Barditch-Crovo P.; Lietman P. S.; Hwang F.; Cundy K. C.; Rooney J. F.; Hellmann N. S.; Safrin S.; Kahn J. O. Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Antiretroviral Activity of Intravenous 9- [2-(R)-(Phosphonomethoxy)Propyl]Adenine, a Novel Anti-Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Therapy, in HIV-Infected Adults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42 (9), 2380–2384. 10.1128/AAC.42.9.2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks S. G.; Barditch-Crovo P.; Lietman P. S.; Hwang F.; Cundy K. C.; Rooney J. F.; Hellmann N. S.; Safrin S.; Kahn J. O. Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Antiretroviral Activity of Intravenous 9- [2-(R)-(Phosphonomethoxy)Propyl]Adenine, a Novel Anti-Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Therapy, in HIV-Infected Adults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42 (9), 2380–2384. 10.1128/AAC.42.9.2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barditch-Crovo P.; Deeks S. G.; Collier A.; Safrin S.; Coakley D. F.; Miller M.; Kearney B. P.; Coleman R. L.; Lamy P. D.; Kahn J. O.; McGowan I.; Lietman P. S. Phase I/II Trial of the Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Antiretroviral Activity of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Adults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45 (10), 2733–2739. 10.1128/AAC.45.10.2733-2739.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz M.; Zolopa A.; Squires K.; Ruane P.; Coakley D.; Kearney B.; Zhong L.; Wulfsohn M.; Miller M. D.; Lee W. A. Phase I/II Study of the Pharmacokinetics, Safety and Antiretroviral Activity of Tenofovir Alafenamide, a New Prodrug of the Hiv Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor Tenofovir, in HIV-Infected Adults. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69 (5), 1362–1369. 10.1093/jac/dkt532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzaria S.; Pelicano H.; Johnson R.; Maury G.; Imbach J.-L.; Aubertin A.-M.; Obert G.; Gosselin G. Synthesis, in Vitro Antiviral Evaluation, and Stability Studies of Bis(S-Acyl-2-Thioethyl) Ester Derivatives of 9-[2-(Phosphonomethoxy)Ethyl]Adenine (PMEA) as Potential PMEA Prodrugs with Improved Oral Bioavailability. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 4958–4965. 10.1021/jm960289o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribut N.; D’Erasmo M.; Dasari M.; Giesler K. E.; Iskandar S.; Sharma S. K.; Bartsch P. W.; Raghuram A.; Bushnev A.; Hwang S. S.; Burton S. L.; Derdeyn C. A.; Basson A. E.; Liotta D. C.; Miller E. J. ω-Functionalized Lipid Prodrugs of HIV NtRTI Tenofovir with Enhanced Pharmacokinetic Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64 (17), 12917–12937. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration . VEKLURY® (Remdesivir); 2020, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214787Orig1s010Lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Blagden S. P.; Rizzuto I.; Suppiah P.; O’Shea D.; Patel M.; Spiers L.; Sukumaran A.; Bharwani N.; Rockall A.; Gabra H.; El-Bahrawy M.; Wasan H.; Leonard R.; Habib N.; Ghazaly E. Anti-Tumour Activity of a First-in-Class Agent NUC-1031 in Patients with Advanced Cancer: Results of a Phase I Study. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119 (7), 815–822. 10.1038/s41416-018-0244-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenzer H.; De Zan E.; Elshani M.; van Stiphout R.; Kudsy M.; Morris J.; Ferrari V.; Um I. H.; Chettle J.; Kazmi F.; Campo L.; Easton A.; Nijman S.; Serpi M.; Symeonides S.; Plummer R.; Harrison D. J.; Bond G.; Blagden S. P. The Novel Nucleoside Analogue ProTide NUC-7738 Overcomes Cancer Resistance Mechanisms in Vitro and in a First-in-Human Phase i Clinical Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27 (23), 6500–6513. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan V. C.; Pham C.-D.; Arthur K.; Yang K. L.; Muller F. L. Aliphatic Amines Are Viable Pro-Drug Moieties in Phosphonoamidate Drugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30 (24), 127656. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.