Abstract

Setting

On March 17, 2020, a state of public health emergency was declared in Alberta under the Public Health Act in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Congregate and communal living sites were environments with a high risk of exposure to and transmission of COVID-19. Consequently, provincial efforts to prevent and manage COVID-19 were required and prioritized.

Intervention

During the first 9 months of the pandemic, vaccines were unavailable and alternate strategies were used to prevent and manage COVID-19 (e.g., physical distancing, masking, symptom screening, testing, isolating cases). Alberta Health Services worked with local, provincial, and First Nations and Inuit Health Branch stakeholders to deliver interventions to support congregate and communal living sites. Interventions included resources and site visits to support prevention and preparedness, and the creation of a coordinated response line to serve as a single point of contact to access information and services in the event of an outbreak (e.g., guidance, testing, personal protective equipment, reporting).

Outcomes

Data from an internal monitoring dashboard informed intervention uptake and use. Online survey results found high levels of awareness, acceptability, appropriateness, and use of the interventions among congregate and communal living site administrators (n = 550). Recommendations were developed from reported experiences, challenges, and facilitators, and processes were improved.

Implications

Provincially coordinated prevention, preparedness, and outbreak management interventions supported congregate and communal living sites. Efforts to further develop adaptive system-level approaches for prevention and preparedness, in addition to communication and information sharing in complex rapidly changing contexts, could benefit future public health emergencies.

Keywords: Health promotion, Program evaluation, Implementation science, Population health

Résumé

Lieu

Le 17 mars 2020, un état d’urgence sanitaire a été déclaré en Alberta en vertu de la Loi sur la santé publique pour riposter à la pandémie de COVID-19. Les habitations collectives étaient des environnements qui présentaient un risque élevé d’exposition à la COVID-19 et de transmission du virus. Des efforts provinciaux pour prévenir et gérer la COVID-19 ont donc été nécessaires et se sont vu accorder la priorité.

Intervention

Comme des vaccins n’étaient pas disponibles au cours des neuf premiers mois de la pandémie, d’autres stratégies ont été utilisées pour prévenir et gérer la COVID-19 (p. ex. distanciation physique, port du masque, dépistage des symptômes, tests, isolation des cas). Les Services de santé de l’Alberta ont travaillé avec les acteurs locaux et provinciaux et les fonctionnaires de la Direction générale de la santé des Premières nations et des Inuits pour mener des interventions à l’appui des habitations collectives. Ces interventions ont compris des ressources et des visites sur place pour appuyer la prévention et la préparation, et la création d’une ligne d’intervention coordonnée qui a servi de guichet unique d’accès à l’information et aux services en cas d’éclosion (p. ex. conseils, tests, équipement de protection individuelle, déclaration des cas).

Résultats

Les données d’un tableau de bord interne ont permis d’en savoir plus sur la popularité et l’utilisation de ces interventions. Les résultats d’un sondage en ligne ont fait état de niveaux élevés de connaissance, d’acceptabilité, de pertinence et d’utilisation des interventions chez les administrateurs d’habitations collectives (n = 550). Des recommandations ont été élaborées à partir des expériences signalées et des éléments positifs et négatifs, et les processus ont été améliorés.

Conséquences

Des interventions de prévention, de préparation et de gestion des éclosions coordonnées à l’échelle provinciale ont soutenu les habitations collectives. Il pourrait être utile pour les futures urgences sanitaires de développer ces approches d’adaptation systémiques pour la prévention et la préparation, en plus des communications et de l’échange d’informations dans des contextes en évolution rapide.

Mots-clés: Promotion de la santé, évaluation de programme, science de la mise en œuvre, santé des populations

Introduction

On March 17, 2020, a public health emergency was declared in Alberta under the Public Health Act in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Government of Alberta (GoA), 2021). As vaccines were unavailable until December 2020, public health measures to mitigate transmission and prevent outbreaks were required (Ng et al., 2020; Jefferies et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Congregate and communal living sites (CCLS; e.g., long-term care (LTC) facility, supportive living facilities, shelters, group homes) were at greater risk for experiencing outbreaks due to the large number of people within the physical environment, the close person-to-person proximity, and the type of interactions among people (Tobolowsky et al., 2020). Due to the advanced age and pre-existing health conditions of clients, CCLS included people with the greatest risk of severe outcomes and death (Jenq et al., 2020; Potvin, 2020; Roxby et al., 2020). As a result, the prevention and management of COVID-19 in CCLS were required and prioritized. Initially infection prevention and control strategies were identified as the most effective way to reduce the spread of disease (Hsu & Lane, 2020). Additional strategies included active surveillance for early case detection among asymptomatic clients (Robert, 2020), isolation of suspected and confirmed COVID-19 cases, case investigation, contact tracing, and quarantine measures to suppress or mitigate the potential for and extent of outbreaks (Jefferies et al., 2020; Robert, 2020).

During the project period, Alberta Health (AH), Alberta Health Services (AHS), and CCLS operators had distinct roles in supporting the health and wellness of clients, visitors, and staff within sites. The GoA and AH (i.e., Premier, Minister of Health, Deputy Minister, Chief Medical Officer of Health (CMOH), and Department) were accountable for setting policy, legislation, and standards; allocating funding; defining notifiable disease guidelines; and ensuring compliance with government policies (GoA, 2020a). AHS was, and remains, the fully integrated provincial health system undertaking the delivery of health services following GoA policies and mandates to serve nearly 4.4 million people living in Alberta (AHS, 2021; Veitch, 2018). AHS includes a centralized provincial organization with five coordinated Health Zones supporting CCLS across the province (Veitch, 2018). CCLS were responsible for providing direct care and support to clients in accordance with the various provincial public health and ministerial orders, which they are legally required to follow and in consideration of COVID-19 guidelines (GoA, 2022).

This paper focused on the first 6 months (March 11 to September 11, 2020) of the COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta. As of September 11, 2020, 15,492 cases of COVID-19 had been reported, 13,847 of these cases had recovered, 1343 remained active, and 252 people had died (GoA, 2020b). During this time, AH, AHS, and CCLS stakeholders worked together to develop and implement interventions to decrease COVID-19 transmission and outbreaks in CCLS. The purposes of this project were to:

describe three COVID-19 AHS-led interventions including the prevention and preparedness online resources (PPR), coordinated early identification and reporting (CEIR), and outbreak management (OBM) supporting CCLS; and

explore the implementation outcomes of CCLS administrators and operators whom these interventions were intended to support and consider the implications.

Prior to COVID-19, provincial guidance manuals and OBM supports were available for CCLS with ten or more residents for influenza-like illness (ILI) and gastro-intestinal (GI) infections. Guidance documents and standard operational procedures helped CCLS staff identify ILI and GI cases according to symptoms, define triggers for outbreaks, understand isolation protocols, and provide information on outbreak reporting. In the past, facilities were responsible for monitoring residents’ symptoms and testing. Facilities with two or more residents with similar ILI or GI symptoms would phone a regional AHS contact to report the potential outbreak. Typically, if the symptoms were GI-related, Safe Health Environments (SHE), which includes Zone Environmental Public Health, Provincial Strategies, and administrative staff, was contacted to support the site with outbreak protocols; and if ILI-related, Communicable Disease Control (CDC) was notified. AHS Provincial Population and Public Health (PPPH) CDC, SHE, and MOHs were contacted for notifiable diseases, either directly by existing lab notification processes or through providers at point of care. However, there may have been regional variations across the province.

Interventions

Following a CMOH order for CCLS to report all suspected, probable, or confirmed cases, leadership and stakeholders determined a standardized, triaged, and coordinated system supporting CCLS was needed, rather than expecting staff to navigate and access multiple separate AHS services for public health prevention, preparedness, and outbreak management. Three interventions were developed to coordinate the PPR, CEIR, and OBM AHS COVID-19 services for CCLS to:

accommodate the high volume of inquiries needing a timely response;

provide initial OBM support, including practices, policies, and resources developed from the most current knowledge of COVID-19, provincial regulations (e.g., public health orders), and services responding to emerging needs and requests; and

coordinate services and resources offered by AHS, AH, and other organizations (e.g., laboratory services, personal protective equipment [PPE]).

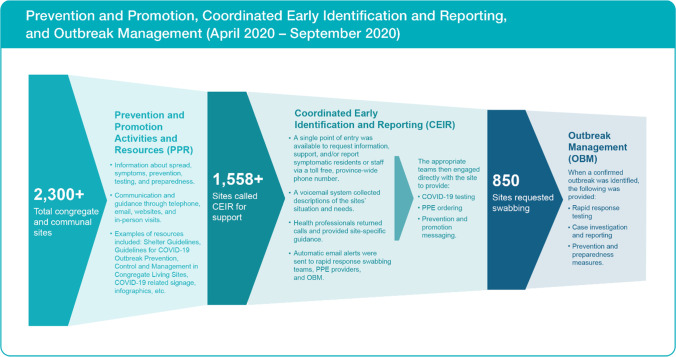

Together, the interventions provided information and services in a timely and coordinated manner to support CCLS and reduce the number of cases and outbreaks. Frequent communication and input from CCLS stakeholders, content experts, and government stakeholders were used to adapt and improve interventions. See Fig. 1 for a description of the PPR, CEIR, and OBM interventions and the uptake over the first 6 months.

Fig. 1.

AHS COVID-19 response process for congregate and communal sites with number of sites served from April to September 2020

Prevention and preparedness resources

PPR was an online collection of resources for CCLS to prevent, prepare for, respond to, and manage COVID-19 cases among their clients, residents, staff, and visitors.

Coordinated early identification and reporting

CEIR was a rapid response system for CCLS with a single-entry point coordinating the intake for multiple COVID-19 services from various AHS departments. The CEIR responded to common queries from CCLS regarding infection prevention/control measures, client/resident isolation, staff health and fitness for work, symptomatic resident, client, or employee reporting, specimen collection requests, PPE orders, and Epidemiological Investigation Number assignment and look-up. A voicemail system collected information on the situation and needs of CCLS. At this time in the pandemic, calls from sites located in South and Central Zones requiring additional support were referred to a regional support.

Outbreak management

OBM provided tailored COVID-19 outbreak prevention, preparedness, and management services. OBM focused on prompt identification of COVID-19-like or ILI symptoms, isolation, and rapid COVID-19 testing of symptomatic clients and staff to limit transmission. Regular communication occurred between members of AHS teams and sites experiencing an outbreak to support containment measures. Under the authority of the AHS Zone MOHs (regional MOHs responsible for a specific geographic area), the provincial outbreak response team included staff from CDC and SHE (i.e., public health inspectors), and redeployed AHS staff.

Evaluation design

The primary focus of this pragmatic process evaluation was to examine the implementation of the PPR, CEIR, and OBM interventions. This project was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta, the AHS-Health Evidence and Innovations, and the Covenant Health Research Centre.

Site participants

CCLS included operators, administrators, or other contacts from LTC facilities; designated supportive living facilities; licensed supportive living; seniors’ lodges; treatment services (e.g., detoxification services); addictions and mental health supportive living; emergency adult shelters; women/family shelters; youth shelters; short-term supportive or transitional accommodations; and child, youth, and adult group homes.

Dashboard

A dashboard allowed monitoring of the number and types of calls and needs of callers. The CEIR dashboard provided real-time data on users, issue types, and responsiveness of AHS staff to calls. These data were used to plan staffing, understand trends, monitor response times, and adapt in real time.

Survey

An invitation to participate in a 46-item online survey evaluating the support provided for the prevention, preparedness, responsiveness, and management of COVID-19 was sent to CCLS identified through an environmental scan of seniors’ facilities, SHE databases, and CEIR users. The online survey was open from August 19 to September 11, 2020. The survey included a combination of Likert scale items, and closed- and open-ended questions designed to assess reach, uptake, acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of the interventions (Proctor et al., 2011; Weiner, et al., 2017). Site-level characteristics of CCLS were identified including type of CCLS, AHS Zone, client age categories, number of client categories, and number of clients or staff with symptoms of COVID-19 or positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests (see Table 1 for a list of the descriptive response categories).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the congregate and communal living sites

| CCLS survey respondent (frequency (percent)) | Alberta population (frequency (percent))* | |

|---|---|---|

| AHS Health Zone | ||

|

Edmonton Calgary Central North South |

154 (30.3%) 139 (26.6%) 98 (19.3%) 79 (15.5%) 39 (7.7%) |

1,336,411 (31.6%) 1,597,750 (37.8%) 487,459 (11.5%) 498,172 (11.8%) 308,113 (7.3%) |

| Total | 509 | 4,228,125 (100.0%) |

| Size of sites | ||

|

Large (›50 clients) Medium (11–50 clients) Small (1–10 clients) |

234 (47.6%) 139 (28.3%) 119 (24.2%) |

|

| Age categories of clients | ||

|

Older adults Adults and older adults Adults Adults and children/youth Children/youth All ages |

254 (50.2%) 94 (18.6%) 74 (14.6%) 16 (3.2%) 43 (8.5%) 25 (4.9%) |

|

| Types of CCLS** | ||

| Designated supportive living facility | 126 (24.5%) | |

| Licensed supportive living | 107 (20.8%) | |

| Seniors lodge | 105 (20.4%) | |

| Long-term care | 96 (18.7%) | |

| Adult group home | 63 (12.3%) | |

| Residential services for children and youth | 43 (8.4%) | |

| Addictions and mental health supportive living | 35 (6.8%) | |

| Women’s/family shelter | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Treatment services | 28 (5.5%) | |

| Emergency adult shelter | 16 (3.1%) | |

| Short-term supportive/transitional housing | 15 (2.9%) | |

| Youth shelter | 7 (1.4%) | |

Note: *The population of Albertans served by each AHS Zone (GoA, 2014). **CCLS were able to select more than one descriptor of the facility (n = 514)

Descriptive statistics of the quantitative responses assessed the frequency and percentage of CCLS characteristics, implementation and client measures, and intervention barriers and facilitators. A series of Pearson’s chi-square analyses were conducted to test differences in the intervention reach and uptake rates by CCLS type. Statistically significant Pearson’s chi-square analyses were followed with residual analyses to identify the cells making the greatest contribution to the significant results. Adjusted residual scores ± 2.00 were identified as constructs of interest (Sharpe, 2015). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24. Content analysis of the qualitative responses was conducted by members of the research team for data reduction and sense-making (Patton, 2002, p.453). Codes, categories, themes, and patterns were confirmed with the whole research team. Evaluators consulted with program area representatives to review and discuss the meaning and relevance of the quotes, codes, themes, and patterns to understand the data, interpret findings, and make recommendations.

Outcomes

CEIR dashboard data

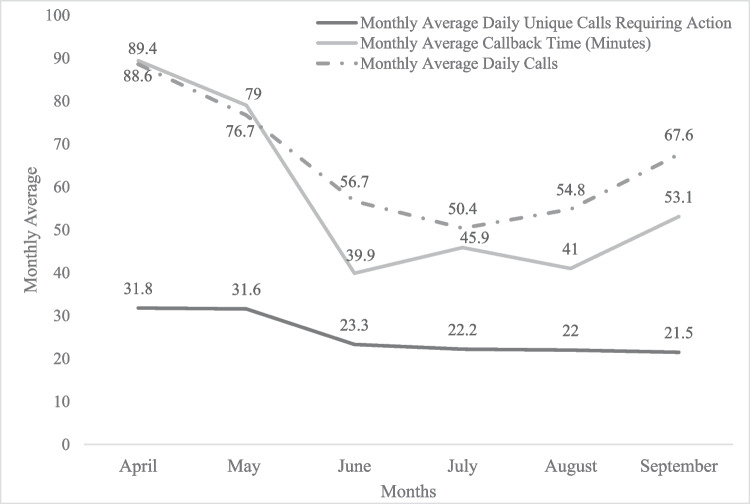

Data were available from April 11 to September 11, 2020, and reported 9856 total calls, with an average of 64 calls each day (range = 14 to 166 calls) to CEIR. Of these, 4975 were resolved immediately and 4881 required further action and referrals (e.g., specimen collection, PPE, OBM) with 157 of these calls being redirected (e.g., school administrators, MOH). The daily average voicemail callback time was 62.5 min (daily average range = 9.7 to 185.9 min). Calls from 1401 unique sites required further action (e.g., 773 of these sites needed specimen collection assistance, 149 needed PPE, 81 were reporting insufficient staff). According to the dashboard data, most of the calls were from group homes (n = 456), supportive living (n = 283), and LTC facilities (n = 244). See Fig. 2 for monthly average number of calls and callback times.

Fig. 2.

Monthly average calls, unique calls requiring action, and callback times

Survey results

The survey reached 2108 unique email addresses and 550 surveys were completed. Twenty-eight of the respondents did not meet the survey criteria; consequently, 522 surveys were included in the analysis (25% response rate). The response rate varied by question.

Descriptive characteristics

Most CCLS were in the Edmonton and Calgary AHS Health Zones, which was consistent with the population distribution. Most respondents represented large CCLS with more than 50 clients. The most common site types represented in the survey data were designated seniors’ living facilities, licensed seniors’ living facilities, seniors’ lodges, and LTC facilities. CCLS clients served by the respondent sites were primarily older adults, adults, or a combination of adults and older adults. Complete descriptive characteristics of the CCLS respondents and sites are presented in Table 1.

Intervention implementation dimensions

Reach

The interventions (PPR and CEIR) reached most respondents; awareness of the various resources among sites was generally high (see Table 2). The reach of the interventions was not significantly different according to CCLS type, apart from the ahs.ca/covid website (website: χ2 (5, 514) = 12.07, p = 0.03). The website reached a greater proportion of adult group home providers than expected (95.9%, adjusted residual = 2.30) and fewer than expected youth shelter providers (57.1%, adjusted residual = − 2.03).

Table 2.

The reach and uptake of the AHS COVID-19 interventions among congregate and communal living site respondents

| Reach of resources (frequency (percent)) | Uptake of resources (frequency (percent)) | Proportion of CCLS that accessed resources out of those aware of resources (uptake/reach) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEIR (1–844) | 389 (74.5%) | 349 (66.9%) | 89.7% | |

| PP resources | Guidelinesa | 429 (82.2%) | 389 (74.5%) | 90.7% |

| PP resources | Signage | 408 (78.2%) | 384 (73.6%) | 94.1% |

| PP resources | Instructional videos | 311 (59.6%) | 218 (41.8%) | 70.1% |

| PP resources | AHS COVID-19 website | 396 (75.9%) | ||

| OM | Phone consult with AHSb | 392 (75.1%) | ||

| OM | Email with AHSc | 344 (65.9%) | ||

| OM | In-person supportd | 303 (58.0%) | ||

| None | 7 (1.3%) | |||

Note. N = 522; aOutbreak Prevention and Management Guidelines (e.g., shelter, CCS); bphone consult with AHS (e.g., Seniors Health, Public Health, Public Health Inspector, Medical Officer of Health, Communicable Disease Control nurse, or other AHS contact); cemailing with AHS (e.g., Seniors Health, Public Health, Public Health Inspector, Medical Officer of Health, Communicable Disease Control nurse, or other AHS contact); din-person support from AHS (e.g., consultation during visits or inspections)

Uptake

Most CCLS utilized CEIR, PPR (except the videos), and OBM interventions (see Table 2). The uptake of most PPR and CEIR interventions was not significantly different according to CCLS type, except for the instructional videos (instructional videos: χ2 (5, 514) = 16.76, p = 0.005). The instructional videos were adopted more than expected by adult group home providers (57.78%, adjusted residual = 2.20) and adult/family shelters (63.27%, adjusted residual = 3.11), and less than expected by LTC, seniors’ living facilities, and seniors’ lodges (38.63%, adjusted residual = − 2.24). Most CCLS that were aware of the CEIR and PPR used them (see Table 2). CEIR was commonly accessed to report a symptomatic person (n = 263), request specimen collection (n = 132), and receive client isolation information (n = 71). The qualitative data identified barriers to the early adoption of CEIR, including uncertainty of CEIR eligibility and the types of support available. The OBM intervention was only provided to CCLS with symptomatic client or employee; 327 respondents (83.2%) met this criterion. Specimen collection was needed for 332 of the respondent sites, and 96 respondents reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. Overall, 82 respondent sites with positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests reported receiving support from OBM.

Implementation outcomes

PPR

According to the qualitative data, PPR were considered acceptable and appropriate by most respondents. Recommendations for improvement included further consultation with users, greater message consistency, more information for non-health-centric CCLS (e.g., group homes, shelters), and additional mental health supports.

CEIR

Most respondent CEIR users agreed that the supports provided were communicated clearly (81.1%) and they knew how to action the recommendations they received (80.5%). Approximately a third (37.8%) of the respondents needed to call CEIR back to follow up on their request to resolve issues with specimen collection or receiving test results, reconcile conflicting information on how to proceed, follow up on non-returned calls, provide additional information on their outbreak, clarify the next steps in the OBM process, or follow up on missing PPE. Most respondents (73.3%) agreed CEIR should be the single point of contact for initiating the prevention and OBM processes going forward. The qualitative data indicated CEIR was acceptable and appropriate. Although initially voicemail callback times were lengthy, participants reported an improvement over time, which aligns with the surveillance dashboard analytics (see Fig. 2). Alternative modes for service delivery were suggested, including having a live person answer calls rather than voicemail, as well as offering an online method for communication.

OBM

Respondents reported OBM interventions (i.e., rapid response testing, case investigations and reporting, and prevention and preparedness) as acceptable, clearly communicated support (80.5%), and respondents knew how to implement the recommendations (85.7%). The qualitative data identified the OBM intervention as feasible. Implementation of the isolation requirements in settings with clients with unique health or behavioural challenges was noted as being difficult.

The qualitative data revealed numerous crosscutting factors facilitating the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of the interventions. Providing clear communication, impactful support, timely information sharing, and client-centred approaches facilitated the acceptability and appropriateness of the interventions. Supporting the development of client-centred supports for groups facing unique challenges to complying with guidelines could improve implementation feasibility. See Table 3 for additional qualitative findings.

Table 3.

Factors that have or could have facilitated the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of intervention implementation according to congregate and communal living site respondents

| Implementation outcome | Theme | Factors that have or could have facilitated intervention implementation and quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | Impactful support |

Support CCLS employees with health and non-health backgrounds to improve their intervention implementation self-efficacy. “Thanks to everyone for their professionalism and willingness to share their expertise.” “The response line and all the team responded quickly, very knowledgeable, provided step by step instructions.” |

| Acceptability/appropriateness | Clear communication |

Provide clear, consistent, accurate information on the implementation and opportunities for two-way communication to clarify any questions or CCLS nuances. Consider assigning a navigator to each site for all pandemic-related support (e.g., updates to interventions, identify the appropriate departments or practitioners). “Having someone … check to make sure we are following the guidelines properly.” “There is no single team of people locally who support the facility and so I am always struggling to find anyone to follow up with or ask questions to.” |

| Appropriateness/acceptability | Timely connections and information sharing |

Provide timely callbacks to CCLS for queries, test results, and scheduling. Explore other modes of two-way communication to improve the timeliness and ease for CCLS (e.g., online chat). Market interventions intentionally and early: include the purpose of the intervention and who is eligible to use it. “Sometimes we did not get a callback in a timely manner, but that is understandable giving their case load.” “We should have found out about it sooner.” “Results of swabbing should be communicated back to the site quicker to determine clear off of investigation or move to outbreak status.” |

| Appropriateness/feasibility | Client-centred interventions |

Provide mental health support for clients and staff. Support CCLS working with clients that are unable and/or unwilling to follow pandemic guidelines and protocols. “Residents miss the normalcy of life and cannot comprehend what is going on. They are deteriorating … They are mourning the loss of what life used to be like.” “There are significant limits in grouping all congregate care settings in one set of rules. Seniors are very different than young mothers.” |

| Feasibility | Enable understanding and learning |

Provide resources, education, and training that includes the rationale for “why” the guideline/intervention was necessary, provides information about “what it is like to experience an outbreak?”, and “how to adapt if necessary?” for frontline staff and management. Connect similar types of sites to improve learning through vicarious experiences. “Although [we] have not had an official outbreak of COVID, it was helpful to learn from staff that had worked at facilities that had outbreaks to better prepare our settings and mind sets for what to expect and alleviating some of the fear of the unknown or the fear of ‘you don't know what you don’t know.’” “Training videos for assuring staff [that] we have everything in place. Training on what it is like to go through a COVID outbreak.” “We were well prepared to implement recommendations prior to being told to implement them so it was fairly smooth.” |

Implications

In the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, AHS public health provided the following three interventions: PPR, CEIR, and OBM (see Fig. 1). These interventions reached the intended audience, uptake of the interventions was high, and the respondents described the implementation as acceptable, appropriate, and feasible. Findings and recommendations for improvement were shared with operational leads.

Users’ understanding, capability, and motivation to adopt interventions may be bolstered by explicitly and directly communicating the effectiveness and eliminating unnecessary complexity using simple actionable steps (Dearing & Singhal, 2020). From the users’ perspective, an overarching issue was the need for adaptations or resources to fit unique CCLS features. The tension between the importance of having universally applicable resources but also context-sensitive tailored resources was reported. Qualitative data indicated that the characteristics of the CCLS (e.g., location, size, type, role), the staff (e.g., role, FTE), and the clients (e.g., abilities, health status) influenced the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of implementation. Additionally, mandatory updates associated with changes to CMOH orders impacted the intervention operations and content, which created confusion at times when changes were underway. Offering clear, current, action-oriented resources including a living document with an appended list and description of changes in practice or policy, modules or guides for context or situation-specific adaptations, and additional individualized implementation advice from a health professional may help CCLS.

The complexity of providing current information and services to a high volume of CCLS from a large provincial health authority required a coordinated and integrated response. Additionally, inter-organizational collaboration among AHS, AH, provincial, and First Nations and Inuit Health Branch stakeholders was needed to enable clear communication, rapid decision-making, and consistent messaging to inform the interventions. For example, CEIR provided CCLS with a single point of contact to initiate support from AHS for COVID-19 information and services that were consistent with the provincial mandates and needs of the CCLS. Inter-organizational communication was needed to provide AHS with the most current information to keep the interventions updated. Following this evaluation, CEIR was expanded to provide a single point of contact for school and daycare support. Intra- and inter-organizational collaboration, coordination, and communication were key to providing timely accurate support to CCLS.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study included several strengths and limitations. Strengths included the use of multiple data sources (i.e., surveys and public health surveillance/monitoring dashboards), a taxonomy of implementation outcomes guiding the survey development and analysis (Proctor, et al., 2011), inter-researcher reliability checks, and validity checks with operational leads. The following are some study limitations. The survey was anonymous; therefore, participant validity checks were not possible and a non-respondent bias may exist. A perceived or potential conflict of interest may have existed as researchers were AHS employees. To mitigate these limitations, evaluators were from different departments and respondents were provided an informed consent for transparency of who was accessing and using the data, and for what purposes. Additionally, this evaluation reflects data and experiences up to September 2020. The pandemic continued beyond this period and this study does not capture the full pandemic experience.

Conclusion

Evaluation findings demonstrated the value of a coordinated and integrated approach to supporting diverse sites across a large geographical area. These interventions could be considered for other infectious diseases (i.e., influenza, norovirus); however, additional research is required to determine the effectiveness, appropriateness, feasibility, and sustainability prior to scale and/or spread of this intervention in non-pandemic situations. This work was an example of how a centralized public health organization can be “agile and nurture close-knit collaborations among public health professionals, government policy-makers, and the scientific community” (Denis et al., 2020).

Implications for policy and practice

What are the innovations in this policy or program?

- This innovative intervention for CCLS provided:

- a provincial, centralized system to receive tailored guidance and support, and for reporting suspected, confirmed, or probable cases of COVID-19;

- a call centre information line for guidance and infection prevention and control strategies at the facility level rather than at the individual level;

- a centrally coordinated system to quickly disseminate the rapidly changing infection prevention guidelines and CMOH orders;

- reports of staffing issues and shortages;

- support for shelters, group homes, and smaller facilities with novel services;

- PPE use guidance and ordering; and

- an approach to triage CDC staff skills in times of high case counts and outbreaks.

What are the burning research questions for this innovation?

- Additional research is required to:

- identify the role of a centralized system for disease reporting and support provision to CCLS in non-pandemic situations. Expanding the interventions to non-pandemic situations would require trained staff to provide infection prevention and control strategies for a variety of illnesses. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the volume of cases made the centralization of these services efficient and effective. In non-pandemic situations, the reduced volume and complexity of cases may limit the feasibility; and

- assess the impact of these interventions on the spread of COVID-19 in CCLS.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all those who contributed to the AHS COVID-19 response and would like to acknowledge the following individuals and teams who were integral to the success of the provincial public health integrated outbreak prevention, preparedness, management, and response interventions. The initial implementation of the interventions could not have succeeded without the exceptional work of Ammneh Azeim, Michael Cleghorn, Carolyn Grolman, Kass Rafih, Gurpreet Rai, Dr. Kathryn Koliaska, Mark Fehr, and David Brown; and the Public Health surveillance dashboard developed by Kerri Fournier. Additionally, we would like to share our gratitude for the guidance and support provided by Dr. David Strong. Finally, thank you to all of IT, Health Link 811, CEIR, Safe Healthy Environments, Communicable Disease Control OBM team members, and Provincial Seniors Health and Continuing Care who worked persistently to support and respond to requests from the congregate and communal living sites over the past years.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Loitz. Analyses were performed by Loitz, Johansen, Johnston, and Strain. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Loitz, Johansen, and Johnston. All authors reviewed, edited, and commented on the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

Data availability

Data for quality improvement are not publicly available. Government of Alberta provides the provincial statistics for COVID-19 case counts and aggregated characteristics of COVID-19 cases here: https://www.alberta.ca/stats/covid-19-alberta-statistics.htm#highlights.

Code availability

N/A

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Alberta, Health Research Ethics Board (Pro00102042), Alberta Health Services-Systems Innovation and Programs, and Covenant Health-Research Centre.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained through the actions of completing and submitting the online survey. Data acquired from public health dashboards only included anonymous aggregated monitoring health system data.

Conflict of interest

The authors were employed by Alberta Health Services.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alberta Health Services. (2021). About AHS. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/about/about.aspx. Accessed 1 May 2022.

- Dearing JW, Singhal A. New directions for diffusion of innovations research: Dissemination, implementation, and positive deviance. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hbe2.216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denis, J. L., Potvin, L., Rochon, J., Fournier, P., & Gauvin, L. (2020). On redesigning public health in Québec: Lessons learned from the pandemic. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 10.17269/s41997-020-00419-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Government of Alberta. (2014). Distribution of population covered by Alberta Health Services Geographic Zone Service Location. https://open.alberta.ca/opendata/distribution-of-population-covered-by-alberta-health-services-geographic-zone-service-location. Accessed 25 March 2022.

- Government of Alberta. (2020a). Alberta Public Health Disease Management Guidelines: Coronavirus-COVID-19. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/a86d7a85-ce89-4e1c-9ec6-d1179674988f/resource/591976c9-0c1e-4e14-b5e9-144add73c89e/download/covid-19-guideline-2020a-04-28.pdf. Accessed 2 April 2022.

- Government of Alberta. (2020b). COVID-19 Alberta Statistics. https://www.alberta.ca/stats/covid-19-alberta-statistics.htm. Accessed 12 Sept 2020.

- Government of Alberta. (2021). Public Health Act (Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000 Chapter P-37). https://www.qp.alberta.ca/1266.cfm?page=P37.cfm&leg_type=Acts&isbncln=9780779817092. Accessed 2 Apr 2022.

- Government of Alberta. (2022). COVID-19 orders and legislation. https://www.alberta.ca/covid-19-orders-and-legislation.aspx. Accessed 29 June 2022.

- Hsu, A. T., & Lane, N. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on residents of Canada’s long-term care homes: Ongoing challenges and policy response. International Long Term Care Policy Network. https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/LTCcovid-country-reports_Canada_Hsu-et-al_updated-April-14-2020.pdf. Accessed 25 March 2022.

- Jefferies S, French N, Gilkison C, Graham G, Hope V, Marshall J, et al. COVID-19 in New Zealand and the impact of the national response: A descriptive epidemiological study. Lancet Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30225-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenq GY, Mills JP, Malani PN. Preventing COVID-19 in assisted living facilities: A balancing act. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, Y., Li, Z., Chua, Y. X., Chaw, W. L., Zhao, Z., Er, B., Pung, R., Chiew, C. J., Lye, D. C., Heng, D., & Lee, V. J. (2020). Evaluation of the effectiveness of surveillance and containment measures for the first 100 patients with COVID-19 in Singapore - January 2-February 29, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 10.15585/MMWR.MM6911E1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3. Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin, L. (2020). Public health saves lives: Sad lessons from COVID-19. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 10.17269/s41997-020-00344-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert A. Lessons from New Zealand’s COVID-19 outbreak response. Lancet Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxby, A. C., Greninger, A. L., Hatfield, K. M., Lynch, J. B., Dellit, T. H., James, A., Taylor, J., Page, L. C., Kimball, A., Arons, M., Munanga, A., Stone, N., Jernigan, J. A., Reddy, S. C., Lewis, J., Cohen, S. A., Jerome, K. R., Duchin, J. S., & Neme, S. (2020). Outbreak investigation of COVID-19 among residents and staff of an independent and assisted living community for older adults in Seattle, Washington. JAMA Internal Medicine. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sharpe D. Chi-square test is statistically significant: Now what? Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. 2015 doi: 10.7275/tbfa-x148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobolowsky, F. A., Gonzales, E., Self, J. L., Rao, C. Y., Keating, R., Marx, G. E., McMichael, T. M., Lukoff, M. D., Duchin, J. S., Huster, K., Rauch, J., McLendon, H., Hanson, M., Nichols, D., Pogosjans, S., Fagalde, M., Lenahan, J., Maier, E., Whitney, H., … Kay, M. (2020). COVID-19 outbreak among three affiliated homeless service sites. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6917e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Veitch D. One province, one healthcare system: A decade of healthcare transformation in Alberta. Healthcare Management Forum. 2018 doi: 10.1177/0840470418794272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. J., Lewis, C. C., Stanick, C., Powell, B. J., Dorsey, C. N., Clary, A. S., Boynton, M. H., & Halko, H. (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N., Shi, T., Zhong, H., & Guo, Y. (2020). COVID-19 prevention and control public health strategies in Shanghai, China. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001202 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data for quality improvement are not publicly available. Government of Alberta provides the provincial statistics for COVID-19 case counts and aggregated characteristics of COVID-19 cases here: https://www.alberta.ca/stats/covid-19-alberta-statistics.htm#highlights.

N/A