Abstract

目前研究力学因素对细胞行为的影响很大程度上依赖于离体实验,基于此本文研制了一种具有较大均匀应变区域的培养室,其中含有以直线电机为动力,频率高达20 Hz的细胞拉伸加载装置,可对细胞施加力学作用。本文以应变均匀为目标,基底厚度为变量,利用有限元技术对传统培养室的基板底部进行优化,最后构建了切面为“M”型结构的新型培养室三维模型,并采用三维数字图像相关法(3D-DIC)检测应变场和位移场的分布,以验证数值模拟结果。实验结果表明,新型细胞培养室增大了应变加载的准确性和均匀区域,较优化前提高了49.13%~52.45%。另外,利用该新型培养室初步研究了在同一应变、不同加载时间下舌鳞癌细胞的形态变化。综上,本文构建的新型细胞培养室结合了以往技术的优点,可传递均匀精准的应变,以便用于广泛的细胞机械生物学研究。

Keywords: 加载装置, 贴壁细胞, 应变均匀, 新型培养室, 优化仿真

Abstract

Based on the current study of the influence of mechanical factors on cell behavior which relies heavily on experiments in vivo, a culture chamber with a large uniform strain area containing a linear motor-powered, up-to-20-Hz cell stretch loading device was developed to exert mechanical effects on cells. In this paper, using the strain uniformity as the target and the substrate thickness as the variable, the substrate bottom of the conventional incubation chamber is optimized by using finite element technique, and finally a new three-dimensional model of the incubation chamber with “M” type structure in the section is constructed, and the distribution of strain and displacement fields are detected by 3D-DIC to verify the numerical simulation results. The experimental results showed that the new cell culture chamber increased the accuracy and homogeneous area of strain loading by 49.13% to 52.45% compared with that before optimization. In addition, the morphological changes of tongue squamous carcinoma cells under the same strain and different loading times were initially studied using this novel culture chamber. In conclusion, the novel cell culture chamber constructed in this paper combines the advantages of previous techniques to deliver uniform and accurate strains for a wide range of cell mechanobiology studies.

Keywords: Loading device, Adherent cells, Strain uniformity, New culture chamber, Optimization simulation

引言

人体内细胞会受到各种力学激励,并在不同的时间和空间尺度上对力学激励做出反应[1-4]。目前,已有一些研究证明了力学激励是如何影响骨吸收和形成[5-6]、器官形态发生[7]、骨骼肌分化以及中枢神经系统发育的[8-9]。由于体内环境的复杂性,多数研究依赖于使用体外系统来研究细胞对机械刺激的反应,其目的是在更可控的细胞培养系统中构建能产生机械转导所需的条件[10-14]。上述系统组成主要包括驱动、传递、培养室等部分[15-18],其中接种细胞的培养室成为近些年的重点研究课题。细胞培养室的材料多为硅胶,透明度高、拉伸延展性好。将细胞接种在单一的硅胶膜上,或接种在具有定位孔的硅胶小室里,可为细胞提供适宜的生存环境。目前国内外实验室常用的细胞培养室中,硅胶膜的形状主要为圆形或矩形[19-22],厚度均匀,尺寸各有不同。此类细胞培养系统,由于体外加载装置中培养室与夹具连接,因此实际上机械力并没有直接施加到细胞本身,而是通过硅胶膜将机械刺激传递至细胞,一旦硅胶膜变形不均匀就会导致实验中应变场量化误差较大,从而无法获得准确的应变条件[23-24]。

因此,本文研制了具有较大均匀应变区域的细胞培养室,搭载自行设计的细胞拉伸加载装置,预期可以将单轴表面应变传递给弹性基底膜上的贴壁细胞。本文采用三维数字图像相关法(three dimensional-digital image correlation,3D-DIC)检测培养室中应变场和位移场的分布,以验证该新型培养室的有效性和实用性。这种培养室结合了以往技术的优点,制造简单,应变均匀性好,可为贴壁细胞的生物力学研究及相关研究人员提供更便利和客观的实验基础。

1. 模型与方法

1.1. 细胞拉伸加载装置

本文所设计的细胞单轴拉伸装置共分为四个部分:电机驱动模块、移动滑块与导轨、细胞培养硅胶小室和3D-DIC实时应变测量系统。如图1所示,在电机控制软件LinMot-Talk 6.9(NTI AG,瑞士)中可对直线电机的运动参数进行设置,电机的最大行程为780 mm,最大速度可达到5.9 m/s,最大频率为20 Hz。装置中的硅胶小室为实验室自行制作。拉伸与固定平台材料选用316不锈白钢,预防腐蚀的发生。实验应变测量选用XTDIC三维全场应变测量分析系统(XTDIC-CONST-SD,新拓三维技术(深圳)有限公司,中国),配备两台高精度摄像头,实现三维环境的应变场和位移场的测量。

图 1.

Cell uniaxial stretching device

细胞单轴拉伸装置

1.2. 培养室有限元优化设计

为了提高培养室基板加载的应变均匀性,本文使用有限元分析软件Abaqus 6.14(SIMULIA,法国)中托斯卡(Tosca)非参数形状优化方法改变培养室中基底膜的结构[25-26]。该方法的原理是在迭代循环中对指定零件表面的节点进行移动,重置既定区域的表面节点位置,直至此区域的目标数值为常数,以减小局部应力集中同时提高应变应力均匀化。优化过程遵循有限元分析步骤[27],分为前处理与后处理,持续的优化迭代可实现目标变量,优化问题中数学模型定义计算如式(1)所示:

|

1 |

其中,ψi为设计响应,U(x)是设计变量x的函数,ψi*是设计响应的约束值,Φmin是目标函数的最小值,N为设计响应的数量,Wi为每个设计响应ψi的权重值,通常情况下,默认权重值为1.0。φiref为一个参考值,形状优化下由优化模块自动计算得到。Ki(x)是设计变量x的函数,Ki*为恒大的值,如制造约束值。

选择硅胶小室基板为设计响应区域,基板的下表面为优化区域,变量为弹性应变,目标函数的参考数值是预定的应变数值。如图2所示,上表面保持不变,下表面节点作为优化节点,位移矢量代表优化前后节点变化的距离和方向,一旦设计响应(此时为应变)大于参考值,节点沿Y的负方向增长,否则节点沿Y的正方向增长,共经历10次循环迭代。

图 2.

Design node update strategy

设计节点更新策略

1.3. 3D-DIC技术

3D-DIC是一种非接触式全场应变测量的工具,进行三维数字图像实验前应先对标定板进行标定[28],目的是确定试件在三维空间中的位置与坐标,为全场应变测量打下基础。如图3所示,左、右相机标定的照片中绿色十字线代表相机中心线,作用是校准双目镜头,保证其拍到相同的区域,注意尽量让标定板上的中心点与中心线交点重合,可以增强空间定位的准确性。其次制造散斑点的过程尤为重要,为了准确跟踪标记,标记字段必须具有非重复性和高对比度模式。使用无反光效果的哑光黑喷漆均匀喷涂在硅胶小室弹性基底膜的上表面,散斑图像中要保证黑斑的清晰性,否则标记样品的识别会出现聚集化、网格移位等问题。

图 3.

3D-DIC calibration and speckle

3D-DIC标定与散斑

1.4. 舌鳞癌细胞加载实验

利用该体外贴壁细胞应变加载装置,对硅橡胶小室内的舌鳞癌细胞SCC15加载拉伸力,诱导0.5%机械应变刺激,频率为0.1 Hz,连续加载8 h;加载结束后,将小室从培养箱内取出,用磷酸缓冲盐溶液(phosphate buffer saline,PBS)漂洗两次并吸净小室内液体后,用4%多聚甲醛4 ℃固定15 min。使用0.5%结晶紫于室温染色30 min并用PBS漂洗去除浮色。置于正置荧光显微镜下采集细胞图像。本实验所用舌鳞癌细胞SCC15来源为天津市口腔功能重建重点实验室传代保存。

2. 结果

2.1. 传统小室与新型培养室数值计算结果对比

本研究通过有限元数值模拟得出传统小室与新型培养室应变场的分布,采用面积占比法来描述应变的均匀性。经本研究优化后的培养室结构及培养室基板底部“M”型结构的剖面如图4所示,其中红色和蓝色虚线框内分别是小室径向和轴向断面的基板结构,不同应变下硅胶小室弹性基底膜的厚度变化趋势类同,即从弹性基底膜中央向室壁的厚度逐渐减小,靠近内腔壁增大。如图5所示,分别是传统小室与新型培养室应变1%~10%的分布云图及有效应变区域,其中规定数值为膜中心应变值的±5%以内是有效的。传统小室的仿真结果表现出了应变的非均匀性,仅基板中央能达到理想的应变值,上下壁和与加载桩连接的部分均无法达到预期的应变值。重点关注有效应变区域,可见经过优化的新型培养室有效应变区域远高于传统小室,表明优化结果能够提高应变的均匀性,曲线图显示了优化前后有效均匀面积占比,优化后较优化前提高了49.13%~52.45%,模拟结果充分说明了新型培养室结构的可行性与准确性。

图 4.

Structure of new culture chamber and the "M" profile

新型培养室结构及“M”型剖面

图 5.

Comparison of strain simulation results between traditional chamber and new culture chamber

传统小室与新型培养室应变仿真结果对比

2.2. 新型培养室模具制造成型

将有限元优化设计得出的基板形状导入到三维计算机辅助设计软件SolidWorks 2016(SolidWorks Inc.,美国)中修饰并设计新型培养室模具。经过多次实验验证,三维打印的树脂模具材料偏软,易出现加载桩断裂、模具掉漆等情况,无法满足脱模的要求。因此优化后的硅胶小室模具选用Q235普通碳素结构钢材料,以数控机加工的方式制作,并经表面打磨喷漆处理达到镜面效果,保证脱模后的硅胶小室基板透明光滑。如图6所示,为了脱模方便对模具进行了改进,四个加载桩设计为可拆卸,起模时可将加载柱优先拆解下来,简化了脱模步骤,同时减小了对硅胶小室的污染。

图 6.

Mold and new culture chambers

模具与新型培养室

2.3. 3D-DIC实验结果

选择1%、5%和10%三组应变数值验证传统小室与新型培养室的数值模拟结果。如图7所示,三组应变下,3D-DIC测量的位移场与应变场的分布与数值模拟结果很好地吻合,达到了相互验证的目的,同时新型培养室的加载实验结果也显示了应变的均匀性,相较于传统小室有了明显的提高,验证了新结构的合理性。

图 7.

Comparison of experimental 3D-DIC results with finite element simulation results for substrates at 1%, 5% and 10% strain

1%、5%和10%应变下基板的3D-DIC实验与有限元仿真结果对比

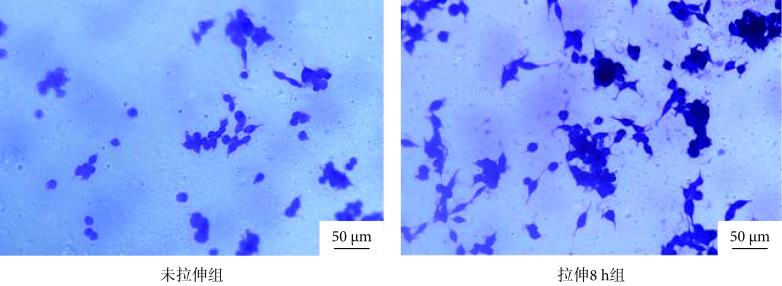

2.4. 舌鳞癌细胞加载实验结果

舌鳞癌细胞加载实验结果如图8所示,未拉伸组细胞呈短梭形,细胞伪足较短;而拉伸8 h后,多数细胞呈长梭形排布,细胞伪足伸长。可见贴壁细胞在加载装置的拉伸形态发生明显的变化。

图 8.

Results of stretch loading of adherent cells

贴壁细胞拉伸加载结果

3. 讨论

本文研制了一种具有较大均匀应变区域的新型培养室,对传统小室的结构进行了优化仿真,结果表明新型培养室有效应变面积得到显著提升,同时利用3D-DIC测量了优化前后小室的应变场与位移场分布,进一步验证了仿真的结果,同时确认了新型培养室的高均匀性,实物的制作也证明了该结构可以运用到相关实验中。

从有限元仿真的角度看来,若对硅胶小室设置指定的应变值,仿真中施加相应的位移,则基板中央的应变值应与指定的应变值一致,但实际仿真中发现并非如此,如表1所示为理论与实际位移数值的差异对比。据分析,造成这种情况的原因有多种,例如由于薄膜厚度的不同,当机械力施加于加载桩上时,传递到薄膜的应力损耗就不同;或者造成基板随着轴向拉伸的径向收缩不同等,以上原因均可能对实验结果造成影响。如表1所示,给出的参考值可为后续的仿真条件提供参考与借鉴。

表 1. Comparison of displacement errors between numerical simulation theory and practice.

数值模拟理论与实际位移误差对比

| 应变 | 理论位移/mm | 真实位移/mm | 相对误差 |

| 1% | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.89% |

| 2% | 1.10 | 0.99 | 1.80% |

| 3% | 1.65 | 1.50 | 2.70% |

| 4% | 2.20 | 2.03 | 3.69% |

| 5% | 2.75 | 2.55 | 4.63% |

| 6% | 3.30 | 3.08 | 5.60% |

| 7% | 3.85 | 3.58 | 4.51% |

| 8% | 4.40 | 4.15 | 7.55% |

| 9% | 4.95 | 4.65 | 8.45% |

| 10% | 5.50 | 5.15 | 9.36% |

在3D-DIC的实验中发现硅胶小室基板的喷漆情况会对实验结果产生较大影响。喷漆斑点的不均匀或不清晰会导致软件分析的网格跳跃性较大,出现严重偏移。个别散斑无法识别时,可以采用插值补洞算法补全形状中的散斑点。同时系统中左右相机的相对角度不宜过大,最好在10°以内,否则容易造成双目相机的非相似性成像。

本研究的目的是针对硅胶小室在拉伸中基板的应变不均匀性问题做出改进。据了解,Gilbert等[29]研究了薄膜在施加压力下的变形,但不包括加载桩,结果显示的非均匀应变场促使他们使用了更薄的膜。该研究表明,上述操作确实增加了细胞承受这种类型应变的区域,但是持续的增加或减小整体的厚度并不合理;基板过厚会导致显微镜下观察不清晰,过薄会引起拉伸中基板断裂属性发生变化。因此,本研究采用“M”型结构的基板,薄厚程度跟随应变的大小改变,后期的实验验证了这种优化的合理性。

在舌鳞癌细胞拉伸实验中发现,细胞经拉伸后形态由短梭形变成长梭形,同时细胞伪足伸长,长短轴比增加。由此可见,在力学激励下细胞形成了更活跃的侵袭足[30-31]。通过细胞实验证明了本装置起到了细胞力学加载的效果,这为细胞力学生物学研究提供了便利条件。同时,在细胞实验中发现,硅胶小室尚存在一些不足之处:基底膜存在一定程度的疏水性,这导致细胞的贴壁性略差。相对于常见的细胞培养装置,硅胶小室基底膜的透明度稍差一些,后期的研究将会对实验中出现的一些问题进行改进,以期提供更好的实验装置。

综上所述,本研究研制了一种应变均匀性更好的培养室,利用3D-DIC技术,可以多角度观测细胞的变形。创新优化的硅胶小室中“M”型的基板底部形状增大了细胞拉伸工况下的应变均匀面积,使得靠近内壁的细胞也能达到理想的应变数值,为后续研究人员分析细胞的应变情况提供更准确的数据。

重要声明

利益冲突声明:本文全体作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

作者贡献声明:王紫琪负责实验设计、数据整理、论文写作;张春秋负责创新点的提出和论文审核;高丽兰、吕林蔚、王鑫负责论文仿真、实验。

致谢:感谢南开大学医学院张军教授和学生孙晓倩对本文生物学实验的帮助。

Funding Statement

国家自然科学基金资助项目(12072235,11672208);天津市自然科学基金项目(21JCYBJC00910)

The National Natural Science Foundation of China; The Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin

References

- 1.Gladilin E, Gonzalez P, Eils R Dissecting the contribution of actin and vimentin intermediate filaments to mechanical phenotype of suspended cells using high-throughput deformability measurements and computational modeling. J Biomech. 2014;47(11):2598–2605. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamill O P, Martinac B Molecular basis of mechanotransduction in living cells. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(2):685–740. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seelbinder B, Scott A K, Nelson I, et al TENSCell: imaging of stretch-activated cells reveals divergent nuclear behavior and tension. Biophys J. 2020;118(11):2627–2640. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng J, Zou Q, Xue Y, et al Mechanical stretch promotes antioxidant responses and cardiomyogenic differentiation in P19 cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2021;15(5):453–462. doi: 10.1002/term.3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan R L, Turner C H Mechanotransduction and the functional response of bone to mechanical strain. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995;57(5):344–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00302070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao J, Fu S, Zeng Z, et al Cyclic stretch promotes osteogenesis-related gene expression in osteoblast-like cells through a cofilin-associated mechanism. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(1):218–224. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beloussov L V, Saveliev S V, Naumidi I I, et al Mechanical stresses in embryonic tissues: patterns, morphogenetic role, and involvement in regulatory feedback. Int Rev Cytol. 1994;150:1–34. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson D G, Carver W, Borg T K, et al Role of mechanical stimulation in the establishment and maintenance of muscle cell differentiation. Int Rev Cytol. 1994;150:69–94. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfister B J, Grasman J M, Loverde J R Exploiting biomechanics to direct the formation of nervous tissue. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2020;14(1):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown T D Techniques for mechanical stimulation of cells in vitro: a review. J Biomech. 2000;33(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J H, Liu C, You L, et al Boning up on Wolff's law: mechanical regulation of the cells that make and maintain bone. J Biomech. 2010;43(1):108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sears C, Kaunas R The many ways adherent cells respond to applied stretch. J Biomech. 2016;49(8):1347–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng L, Xue G, Liu Q, et al In-situ electromechanical testing and loading system for dynamic cell-biomaterial interaction study. Biomed Microdevices. 2020;22(3):56. doi: 10.1007/s10544-020-00514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai Z X, Shih P J, Yen J Y, et al Functional assistance for stress distribution in cell culture membrane under periodically stretching. J Biomech. 2021;125:110564. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Chunqiu, Qiu Lulu, Gao Lilan, et al A novel dual-frequency loading system for studying mechanobiology of load-bearing tissue. Mater Sci Eng C. 2016;69:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Dyke W S, Sun X, Richard A B, et al Novel mechanical bioreactor for concomitant fluid shear stress and substrate strain. J Biomech. 2012;45(7):1323–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bianchi F, George J H, Malboubi M, et al Engineering a uniaxial substrate-stretching device for simultaneous electrophysiological measurements and imaging of strained peripheral neurons. Med Eng Phys. 2019;67(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apa L, Carraro S, Pisu S, et al Development and validation of a device for in vitro uniaxial cell substrate deformation with real-time strain control. Meas Sci Technol. 2020;31:125702. doi: 10.1088/1361-6501/aba011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei Y, Masjedi S, Ferdous Z A study of extracellular matrix remodeling in aortic heart valves using a novel biaxial stretch bioreactor. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2017;75:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dermenoudis S, Missirlis Y Design of a novel rotating wall bioreactor for the in vitro simulation of the mechanical environment of the endothelial function. J Biomech. 2010;43(7):1426–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toume S, Gefen A, Weihs D Printable low-cost, sustained and dynamic cell stretching apparatus. J Biomech. 2016;49(8):1336–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsukamoto S, Asakawa T, Kimura S, et al Intranuclear strain in living cells subjected to substrate stretching: A combined experimental and computational study. J Biomech. 2021;119:110292. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morita Y, Watanabe S, Ju Y, et al In vitro experimental study for the determination of cellular axial strain threshold and preferential axial strain from cell orientation behavior in a non-uniform deformation field. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2013;67(3):1249–1259. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bieler F H, Ott C E, Thompson M S, et al Biaxial cell stimulation: A mechanical validation. J Biomech. 2009;42(11):1692–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu Xiaojun, Cao Yinfeng, Zhu Jihong, et al Shape optimization of SMA structures with respect to fatigue. Mater Design. 2020;189:108456. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Upadhyay B D, Sonigra S S, Daxini S D Numerical analysis perspective in structural shape optimization: A review post 2000. Adv Eng Softw. 2021;155:102992. doi: 10.1016/j.advengsoft.2021.102992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.郭新路, 刘蓉, 王永轩 仿骨小梁力学性能的多孔结构拓扑优化设计. 医用生物力学. 2018;33(5):402–409. doi: 10.16156/j.1004-7220.2018.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.邱璐璐, 宋阳, 李可, 等 数字图像相关技术在生物力学方面的研究进展. 生物医学工程与临床. 2017;21(6):676–681. doi: 10.13339/j.cnki.sglc.20171107.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert J A, Weinhold P S, Banes A J, et al Strain profiles for circular cell culture plates containing flexible surfaces employed to mechanically deform cells in vitro. J Biomech. 1994;27(9):1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albiges-Rizo C, Destaing O, Fourcade B, et al Actin machinery and mechanosensitivity in invadopodia, podosomes and focal adhesions. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(17):3037–3049. doi: 10.1242/jcs.052704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gasparski A N, Ozarkar S, Beningo K A Transient mechanical strain promotes the maturation of invadopodia and enhances cancer cell invasion in vitro. J Cell Sci. 2017;130(11):1965–1978. doi: 10.1242/jcs.199760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]