Abstract

Background:

A randomized controlled trial involving a high-risk, unvaccinated population that was conducted before the Omicron variant emerged found that nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was effective in preventing progression to severe COVID-19. Our objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir in preventing severe COVID-19 while Omicron and its subvariants predominate.

Methods:

We conducted a population-based cohort study in Ontario that included all residents who were older than 17 years of age and had a positive polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV-2 between Apr. 4 and Aug. 31, 2022. We compared patients treated with nirmatrelvir–ritonavir with patients who were not treated and measured the primary outcome of hospital admission from COVID-19 or all-cause death at 1–30 days, and a secondary outcome of all-cause death. We used weighted logistic regression to calculate weighted odds ratios (ORs) with confidence intervals (CIs) using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) to control for confounding.

Results:

The final cohort included 177 545 patients, 8876 (5.0%) who were treated with nirmatrelvir–ritonavir and 168 669 (95.0%) who were not treated. The groups were well balanced with respect to demographic and clinical characteristics after applying stabilized IPTW. We found that the occurrence of hospital admission or death was lower in the group given nirmatrelvir–ritonavir than in those who were not (2.1% v. 3.7%; weighted OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.47–0.67). For death alone, the weighted OR was 0.49 (95% CI 0.39–0.62). Our findings were similar across strata of age, drug–drug interactions, vaccination status and comorbidities. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 case of severe COVID-19 was 62 (95% CI 43–80), which varied across strata.

Interpretation:

Nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was associated with significantly reduced odds of hospital admission and death from COVID-19, which supports use to treat patients with mild COVID-19 who are at risk for severe disease.

Antiviral therapies to treat COVID-19 and prevent severe outcomes such as hospital admission and death are valuable tools in the global pandemic response. The Evaluation of protease inhibition for COVID-19 in high-risk patients (EPIC-HR) randomized controlled trial (RCT) of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir identified an 89% reduction in progression to severe COVID-19 in participants at high risk of severe disease who were treated, compared with placebo.1 However, the trial was conducted between July and December 2021, which was before the emergence of the Omicron variant that is less virulent than the progenitor virus,2 and excluded vaccinated people, as well as those taking medications with potential drug interactions.1 The Evaluation of protease inhibition for COVID-19 in standard-risk patients (EPIC-SR) trial recently reported nonsignificant findings in a press release.3

In real-world evaluations of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir while the Omicron variant and its subvariants were predominating, a significant protective effect was seen in adults 65 years of age and older in Israel.4 A retrospective cohort study involving patients with COVID-19 who attended designated outpatient clinics in Hong Kong between Feb. 16 and Mar. 31, 2022, identified a reduced risk of hospital admission in adults when given nirmatrelvir–ritonavir, albeit attenuated compared with the EPIC-HR trial.5 Studies that have stratified participants by vaccination status identified similar reductions in relative risk in vaccinated cohorts but with smaller reductions in absolute risk because of the lower baseline risk of hospital admission or death from COVID-19.4,6,7 Observational studies have risks of bias that include residual confounding and immortal time bias.8

In Ontario, nirmatrelvir–ritonavir became widely available and funded for all patients in the community by April 2022, with clinical criteria set by the government limiting access only to patients who were older, had comorbidities or were undervaccinated.9,10 The Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table provided clinical practice guidance to Ontario clinicians on the use of therapeutics for COVID-19 with stricter high-risk criteria based on patients who were most likely to benefit from the limited supplies of antiviral drug at the time.11 A large proportion of patients who received nirmatrelvir–ritonavir in Ontario would have been excluded from the EPIC-HR trial population (e.g., those previously vaccinated or receiving concomitant medications with significant drug–drug interactions). Observational data evaluating use of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir can inform future policy and guidelines. Our objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir on health outcomes, including hospital admission and death from COVID-19, while Omicron and its subvariants predominated.

Methods

Study population and setting

We conducted a population-based cohort study in Ontario (Canada’s most populous province) with a population of about 15 million in 2022. Ontario has publicly funded health insurance that covers most of the population. The cost of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was covered for all Ontarians regardless of their health insurance coverage. We assessed all people in Ontario between the ages of 18 and 110 years who had a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2 between Apr. 4, 2022, and Aug. 31, 2022, for study inclusion. We excluded those who were not Ontario residents, or had invalid identifiers such as date of birth or death before the test date. We also excluded patients who were admitted to hospital or those with nosocomial infections before or on the day of testing. The data were housed and analyzed at ICES using unique encoded identifiers. ICES is an independent, nonprofit research institute whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze health care and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement.

Study design

We used inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) from propensity scores to adjust for confounding in our observational study. We defined a propensity score as the probability of treatment assignment conditional on measured baseline covariates.12,13 Using the propensity score, IPTW weighted people who were treated by the inverse probability of not receiving nirmatrelvir–ritonavir and weighted those who were not treated with the inverse probability of receiving nirmatrelvir–ritonavir. This approach yielded a synthetic sample in which receipt of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was independent of measured baseline covariates. Using IPTW obtains unbiased estimates of average treatment effects (assuming no residual confounding).12 Owing to the low propensity for receiving nirmatrelvir–ritonavir for some covariates, we used stabilized weights, which reduced the variability of the estimated treatment effect.14 We selected the variables included in the IPTW a priori based on their clinically important risk of confounding. The most important predictors of severe COVID-19 in the literature include age, vaccination status and time from last vaccine dose, previous COVID-19, comorbidities and cumulative number of comorbidities.15,16 Therefore, we included age, sex, number of doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (0, 1, 2, or 3 or more), previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, time from last vaccine dose (14–89, 90–179, 180–269, or 270 or more d), individual comorbidities (including chronic respiratory disease, chronic heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, immune compromised, autoimmune disease, dementia, chronic kidney disease and advanced liver disease) (Appendix 1, Table S1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.221608/tab-related-content), long-term care residence, and high versus standard risk using the definition from the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, which is based on age, number of comorbidities and number of vaccine doses received.11

Data sources

We obtained prescription data for nirmatrelvir–ritonavir from the Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) database, which is more than 99% accurate in identifying the outpatient prescription medications dispensed.17 Nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was approved for use by Health Canada on Jan. 17, 2022. Shortly thereafter, limited supplies were available from select COVID-19 assessment centres in Ontario for use; however, these prescriptions were not captured in the ODB. Beginning Apr. 4, 2022, publicly funded access to nirmatrelvir–ritonavir from community pharmacies became available for any Ontario resident who met the province’s eligibility criteria (Appendix 1, Table S2). Dispensing through community pharmacies increased rapidly and reached about 85% of all nirmatrelvir–ritonavir prescriptions during the study period. Therefore, to reduce the risk of misclassification bias, we excluded anyone with a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 from 1 of 27 COVID-19 assessment centres that dispensed nirmatrelvir–ritonavir because their exposure status could not be determined using our data. We obtained SARS-CoV-2 test results from the COVID-19 Integrated Testing (C19INTGR) database, which contains all SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests (but not antigen test results). Eligibility for PCR testing changed in December 2021 and was limited to specific groups, including those eligible for therapeutics for COVID-19.

We obtained vaccination status from the COVAXON database, a central data repository for SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations in Ontario that is administered by the Ontario Ministry of Health.18 We obtained comorbidity data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) databases, as well as other validated disease-specific cohorts at ICES (Appendix 1, Table S1). We defined the index date for people exposed to nirmatrelvir–ritonavir as the date the drug was dispensed. A time-to-dispense (TTD) distribution was then created for the treated cohort that we defined as the time in days from testing positive to medication dispensing. To minimize immortal time bias, we then assigned a random index date to the untreated group based on the TTD distribution from those who were treated. For example, 37% of the treated group was dispensed nirmatrelvir–ritonavir on day 0; therefore, if the random uniform number generated for an unexposed person was between 0 and 0.37, we assigned a value of 0 for TTD and their index date was defined as their test date (Appendix 1, Figure S1). We excluded any patient who died or was admitted to hospital on or before their index date (dispense date for patients who were exposed and simulated index date for those not exposed).

We obtained data for drug–drug interactions from ODB. Based on the availability of data on medication prescriptions, we limited the analysis of drug–drug interactions to patients older than 70 years of age. We defined potential drug–drug interaction as any severity level 1 or 2 co-medications with an ODB claim with an overlap in days supplied and the dispense date of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir, where level 1 included any co-medications contraindicated with nirmatrelvir–ritonavir (i.e., nirmatrelvir–ritonavir should not be prescribed as stopping the co-medication is insufficient to mitigate drug–drug interaction) and level 2 included co-medications with clinically significant drug–drug interactions that require a mitigation strategy while on nirmatrelvir–ritonavir (i.e., holding co-medication, dose or interval adjustment, use of an alternative agent, management of adverse effects and additional monitoring) according to the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table guideline (Appendix 1, Table S3).19 We did not evaluate drug–drug interactions in patients who were younger than 70 years of age.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the composite of hospital admission because of COVID-19 or all-cause death that occurred 1–30 days after the index date. We ascertained hospital admissions from the Case and Contact Management database (Public Health Ontario). This information is provided by local public health units for public health purposes and defines hospital admissions related to COVID-19 for people who received treatment for COVID-19 while in hospital or if their length of stay was extended because of COVID-19. This database has similar rates of ascertainment of hospital admissions and death compared to other administrative data sources.20 We obtained data on death from either the Case and Contact Management database or the Registered Persons DataBase.

Statistical analysis

We compared the distributions of unweighted and weighted (using stabilized weights) covariates using standardized differences, with a value of less than 0.1 reflecting a clinically unimportant difference. We used IPTW-weighted logistic regression models for each of the 2 outcomes, with treatment as the only covariate, to ascertain the treatment effect. We have presented the estimated treatment effects as weighted odds ratios (ORs) with confidence intervals (CIs); we considered p values less than 0.05 to be statistically significant. Using the estimated probabilities of the outcomes for treated and untreated groups derived from the weighted logistic regression models, we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) with CIs. Preplanned stratified analyses included age (≥ 70 or < 70 yr), vaccination status (0, 1–2, or ≥ 3 doses), potential drug–drug interactions in those older than 70 years of age (level 1, level 2 or no drug–drug interactions identified), comorbidities (≥ 3 or < 3), long-term care residents, high or standard risk as defined by the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table and time (April to June 2022 or July to August 2022). We added time since last vaccination (14–179 or > 179 d) post hoc to the stratified analyses. We analyzed the data using SAS enterprise guide version 9.4.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Research Board at Public Health Ontario (2022–015.01).

Results

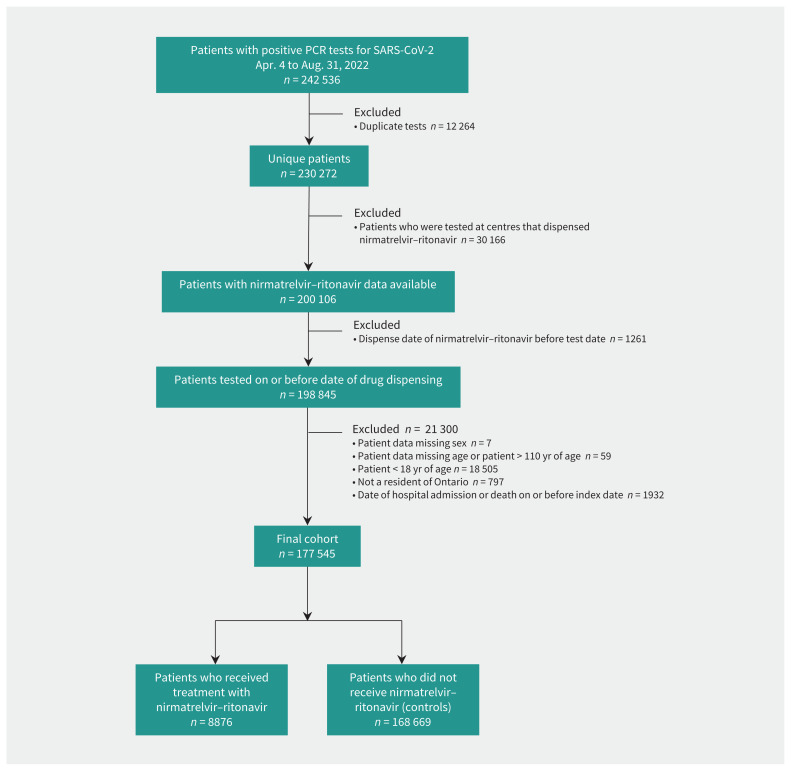

We identified 242 536 people who had a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR between Apr. 4, 2022, and Aug. 31, 2022. After we applied the study inclusion and exclusion criteria, there were 8876 people who received nirmatrelvir–ritonavir and 168 669 people who did not receive this treatment (Figure 1). Before weighting, the cohort who received nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was predominately 70 years of age or older (72.5%), had received 3 or more vaccine doses (84.8%), had fewer than 3 comorbidities (57.1%), were standard risk by Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table criteria (58.1%) and did not reside in long-term care (68.5%). For those 70 years of age or older, 66.7% had 1 or more potential drug–drug interactions (Appendix 1, Table S4). Before weighting, major between-group differences existed among almost all variables that we evaluated (Table 1). Recipients of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir were older, more likely to have 3 or more vaccine doses, had more comorbidities, were more likely to meet high-risk criteria and more likely to reside in long-term care. After weighting, all standardized differences were 0.03 or less, indicating no clinically important differences between any covariates (Appendix 1, Figure S2). After weighting, all standardized differences were 0.03 or less, indicating no clinically important differences between any covariates.

Figure 1:

Cohort creation flow chart. Note: PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

Table 1:

Baseline population characteristics of participants who received and did not receive nirmatrelvir–ritonavir before weighting with standardized differences

| Variable | Unweighted population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of patients* | Standardized difference | ||

| Received nirmatrelvir–ritonavir n = 8876 |

Did not receive nirmatrelvir–ritonavir n = 168 669 |

||

| Age, yr | |||

| Mean ± SD | 74.3 ± 16.3 | 52.4 ± 21.0 | 1.17 |

| Median (IQR) | 77 (67–86) | 50 (35–67) | |

| Sex, female | 5261 (59.3) | 106 899 (63.4) | 0.08 |

| No. of vaccine doses | |||

| 0 | 467 (5.3) | 10 434 (6.2) | 0.04 |

| 1 | 87 (1.0) | 1625 (1.0) | < 0.01 |

| 2 | 798 (9.0) | 28 704 (17.0) | 0.24 |

| ≥ 3 | 7524 (84.8) | 127 906 (75.8) | 0.23 |

| Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection | 412 (4.6) | 11 670 (6.9) | 0.10 |

| Time from last vaccine dose, d | |||

| 14–89 | 1453 (16.4) | 17 438 (10.3) | 0.18 |

| 90–179 | 3759 (42.4) | 72 705 (43.1) | 0.02 |

| 180–269 | 2405 (27.1) | 46 190 (27.4) | 0.01 |

| ≥ 270 | 1259 (14.2) | 32 336 (19.2) | 0.13 |

| Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table risk group11 | |||

| High risk | 3720 (41.9) | 25 499 (15.1) | 0.62 |

| Standard risk | 5156 (58.1) | 143 170 (84.9) | 0.62 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 3128 (35.2) | 40 813 (24.2) | 0.24 |

| Chronic heart disease | 2249 (25.3) | 18 910 (11.2) | 0.37 |

| Diabetes | 2996 (33.8) | 27 954 (16.8) | 0.40 |

| Immune compromised | 1412 (15.9) | 10 102 (6.0) | 0.32 |

| Hypertension | 6071 (68.4) | 54 549 (32.3) | 0.77 |

| Dementia | 2659 (30.0) | 15 714 (9.3) | 0.54 |

| Autoimmune disease | 1150 (13.0) | 8504 (5.0) | 0.28 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1108 (12.5) | 9867 (5.9) | 0.23 |

| Advanced liver disease | 209 (2.4) | 2110 (1.3) | 0.08 |

| Long-term care resident | 2795 (31.5) | 12 806 (7.6) | 0.63 |

Note: IQR = interquartile range, SD = standard deviation.

Unless specified otherwise.

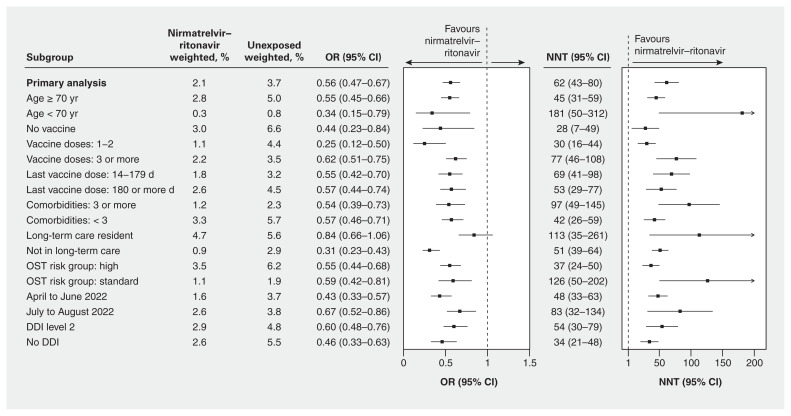

In the weighted primary analysis, we found that people who received nirmatrelvir–ritonavir and those who did not had a 2.1% and 3.7% risk of hospital admission or death, respectively. The weighted OR of hospital admission or death within 30 days was 0.56 (95% CI 0.47–0.67, p < 0.001) (Figure 2) and the weighted OR of death alone was 0.49 (95% CI 0.40–0.60, p < 0.001) (Appendix 1, Table S5). Results overall were similar in the stratified analyses by age, vaccine status, comorbidities, drug–drug interactions and risk status (Appendix 1, Figure S3). We observed a possible decrease in effectiveness over time with a weighted OR of 0.43 (95% CI 0.33–0.57) for hospital admission or death between April and June 2022 and a weighted OR of 0.67 (95% CI 0.52–0.86) in July and August 2022, with a similar trend for death alone (Appendix 1, Table S5).

Figure 2:

Forest plot of weighted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for hospital admission from COVID-19 or all-cause death and number needed to treat (NNT), at 30 days for the primary analysis and stratified analyses for patients who received nirmatrelvir–ritonavir compared with those who did not. Note: DDI = drug–drug interaction, OST = Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table.

We calculated that the NNT was 62 (95% CI 43–80) people treated with nirmatrelvir–ritonavir to prevent 1 hospital admission or death from COVID-19. There was substantial variability in absolute risk reductions by strata, with NNT ranging from 28 (95% CI 7–49) for unvaccinated people to 181 (95% CI 50–312) for those younger than 70 years of age (Figure 2; Appendix 1, Figure S3).

Interpretation

We found that the use of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir in Ontario between April and August 2022 was associated with a significant reduction in the odds of hospital admission from COVID-19 or all-cause death with a NNT of 62. Our findings were consistent across most strata of age, drug–drug interactions, vaccination status and comorbidities; however, the absolute risk reductions were substantially lower in younger patients and those at lower risk of severe COVID-19. The largest benefits were observed in patients who were under-vaccinated or unvaccinated and people 70 years of age or older.

As far as we are aware, the EPIC-HR study is the only published RCT on nirmatrelvir–ritonavir that reported a relative risk reduction of 89% and an absolute risk reduction of 6% (NNT = 17) for the prevention of severe COVID-19 illness. However, EPIC-HR was conducted before the Omicron variant emerged and it excluded patients who were vaccinated and those with drug–drug interactions.1 Unpublished results from the subsequent EPIC-SR trial involving patients at lower risk of COVID-19 showed a nonsignificant 57% relative reduction in hospital admissions and death in a vaccinated subgroup of patients.3 Our cohort was older and almost all vaccinated, with most having potential drug–drug interactions, which is a different patient population than in the EPIC-HR clinical trial.

After adjustment for substantial confounding and addressing potential immortal time bias through the study design, we observed a significant clinical benefit to use of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir, albeit less than with the EPIC-HR trial. This may be because of differences in the patient population, underlying immunity in the population, differences among circulating variants or study design.

A 2022 cohort study in Israel identified an adjusted hazard ratio for severe COVID-19 in patients 65 years of age or older of 0.27 (95% CI 0.15–0.49) in those who received nirmatrelvir–ritonavir but only 0.74 (95% CI 0.35–1.58) in those 40–64 years of age. Their findings were similar when further stratified by previous immunity to SARS-CoV-2. This study was also a real-world evaluation with similar patient characteristics to ours, although the Israeli cohort excluded patients with drug–drug interactions.4

Our study, in conjunction with previous clinical trials and observational research, supports the effectiveness of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir at reducing hospital admission from COVID-19 and all-cause death. Risk factors for severe disease include older age (the single most important risk factor), as well as obesity, the number of comorbidities and time from previous vaccination. Vaccination and immunity from previous infection are significantly protective.15 We observed potentially important differences in the absolute risk reductions that may have implications for cost-effectiveness evaluations. Differences between strata had overlapping CIs; we did not compare these statistically, and any observed differences should be interpreted with caution. Further stratification by different age groups and risk factors may be helpful in the future to evaluate the benefit in those younger than 70 years of age.

Two-thirds of our cohort who were 70 years of age or older had potentially clinically significant drug–drug interactions (Appendix 1, Table S3), which reflects the numerous medications that have important drug–drug interactions with ritonavir. Based on the data sources used in this study, we were unable to confirm whether patients were actually taking interacting medications concurrently or determine if any potential drug–drug interactions were appropriately mitigated at the time of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir prescribing, which may have affected our estimation of drug–drug interactions. Our results suggest that patients with COVID-19 and level 2 drug–drug interactions can be effectively treated with nirmatrelvir–ritonavir, and that prescribers and pharmacists are key in the evaluation for and mitigation of drug–drug interactions.

Limitations

Our cohort was limited to those with a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR and did not include those with positive test results by only rapid antigen tests, which may limit the generalizability of our findings.

Nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was publicly funded for all Ontario residents; however, ODB captures only about 85% of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir prescriptions. We excluded patients who were tested at any of the 27 COVID-19 assessment centres where nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was dispensed without an ODB claim to limit the risk of misclassification bias. Our database indicated that the medication was dispensed, but we could not assess adherence. During the study period, there was no use of molnupirivir as it was not approved by Health Canada at that time. There was some outpatient use of intravenous (IV) remdesivir, which we were unable to identify in our administrative data, but the number of patients in the untreated group who received IV remdesivir was likely to be low and would bias the study toward the null.

Observational cohort studies have a risk of immortal time bias, which we attempted to mitigate through imputing theoretical dispensing dates for the untreated group. By imputing index dates that mirror the treated groups’ distribution, we removed people who were not treated from the cohort who may have experienced the outcome before having the opportunity to receive nirmatrelvir–ritonavir. However, some residual bias is possible. As a result of excluding outcomes that occurred on the day of or before the index date, the number of hospital admissions from COVID-19 that contributed to the outcome was relatively small. However, we identified consistent results for the primary composite outcome and for all-cause death alone. There was significant confounding because nirmatrelvir–ritonavir is recommended for and limited to patients who were at higher risk of the outcome. Although the IPTW method successfully balanced the groups by all evaluated covariates, residual confounding is possible. Finally, the absolute risk reductions reported in this study should be interpreted cautiously as they may not reflect the true disease incidence in the population.

Conclusion

In this population-level evaluation of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir we observed a significant reduction in the odds of hospital admission from COVID-19 and all-cause death, which supports the ongoing use of this antiviral drug to treat patients with mild illness who are at risk of severe COVID-19. Although the relative effectiveness was similar across the strata and risk groups that we evaluated, we observed substantial variation in the absolute risk reduction, which suggests that use of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir in populations at lower risk of COVID-19 may have limited population health benefits with important implications for its cost-effectiveness evaluations. Ongoing evaluation to monitor effectiveness in the population with new circulating variants is critical to inform optimal use over time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank IQVIA Solutions Canada for use of their Drug Information File.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Tara Gomes has received a stipend from Indigenous Services Canada for their role on the Drugs and Therapeutics Advisory Committee. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors conceived the study and provided input on the design and analysis plan. Jun Wang performed the analysis. Kevin Schwartz drafted the manuscript. All of the authors provided input for the interpretation of the analysis, provided critical edits for the manuscript, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This project was funded by Public Health Ontario. Peter Daley has received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Janeway Foundation, the Memorial University Seed, Bridge and Multidisciplinary Fund and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Tara Gomes has received grants and contracts from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ontario College of Pharmacists.

Data sharing: The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. Although legal data-sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (e.g., health care organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access (available at https://www.ices.on.ca/DAS; email: das@ices.on.ca). The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, with the understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in the material are those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of CIHI.

References

- 1.Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al. EPIC-HR Investigators. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulloa AC, Buchan SA, Daneman N, et al. Estimates of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant severity in Ontario, Canada. JAMA 2022;327:1286–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfizer reports additional data on PAXLOVIDTM supporting upcoming new drug application submission to U.S. FDA [press release]. New York: Pfizer; 2022. June 14. Available: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-reports-additional-data-paxlovidtm-supporting (accessed 2022 Oct. 18). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbel R, Wolff Sagy Y, Hoshen M, et al. Nirmatrelvir use and severe COVID-19 outcomes during the Omicron surge. N Engl J Med 2022;387:790–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yip TCF, Lui GCY, Lai MSM, et al. Impact of the use of oral antiviral agents on the risk of hospitalization in community COVID-19 patients. Clin Infect Dis 2022. Aug. 29 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Najjar-Debbiny R, Gronich N, Weber G, et al. Effectiveness of Paxlovid in reducing severe COVID-19 and mortality in high-risk patients. Clin Infect Dis 2022. June 2 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganatra S, Dani SS, Ahmad J, et al. Oral nirmatrelvir and ritonavir in nonhospitalized vaccinated patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 2022. Aug. 20 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.COVID-19 testing and treatment. Government of Ontario; 2022, updated 2022 Dec. 29. Available: https://www.ontario.ca/page/covid-19-testing-and-treatment (accessed 2022 Oct. 13). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nirmatrelvir and ritonavir (Paxlovid) for mild to moderate COVID-19. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; updated 2022 Jan. 28. Available: https://www.cadth.ca/nirmatrelvir-and-ritonavir-paxlovid-mild-moderate-covid-19 (accessed 2022 Oct. 27). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komorowski AS, Tseng A, Vandersluis S, et al. Evidence-based recommendations on the use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) for adults in Ontario. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table; 3. 2022. Available: https://covid19-sciencetable.ca/sciencebrief/evidence-based-recommendations-on-the-use-of-nirmatrelvir-ritonavir-paxlovid-for-adults-in-ontario/download.pdf (accessed 2022 Oct. 27). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015;34:3661–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu S, Ross C, Raebel MA, et al. Use of stabilized inverse propensity scores as weights to directly estimate relative risk and its confidence intervals. Value Health 2010;13:273–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:656–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agrawal U, Bedston S, McCowan C, et al. Severe COVID-19 outcomes after full vaccination of primary schedule and initial boosters: pooled analysis of national prospective cohort studies of 30 million individuals in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Lancet 2022;400:1305–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Underlying medical conditions associated with higher risk for severe COVID-19: information for healthcare professionals. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; updated 2022 Dec. 5. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html (accessed 2022 Dec. 8). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy AR, O’Brien BJ, Sellors C, et al. Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2003; 10:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung H, He S, Nasreen S, et al. Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) Provincial Collaborative Network (PCN) Investigators. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 outcomes in Ontario, Canada: test negative design study. BMJ 2021;374:n1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ontario COVID-19 Drugs and Biologics Clinical Practice Guidelines Working Group, University of Waterloo School of Pharmacy. Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid): what prescribers and pharmacists need to know. Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table 2022;3. doi: 10.47326/ocsat.2022.03.58.3.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung H, Austin PC, Brown KA, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines over time prior to omicron emergence in Ontario, Canada: test-negative design study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022;9:ofac449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.