Abstract

Purpose

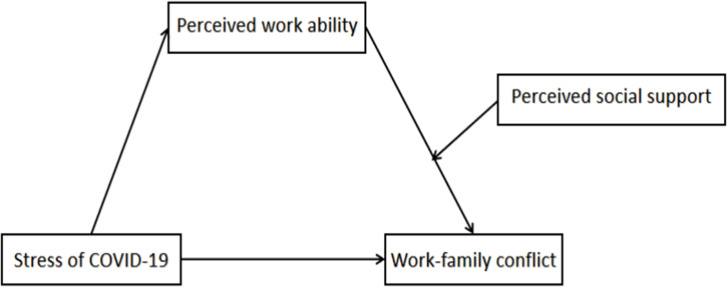

The current study examined the effect of stress of COVID-19 on work-family conflict, how perceived work ability may mediate this effect, and lastly how perceived social support may moderate the various indirect pathway during COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A total of 2558 Chinese adults were recruited from the first author’s university completed the questionnaire including stress of COVID-19 scale, work-family conflict, perceived social support and perceived work ability scale.

Results

The present study showed that stress of COVID-19 was positively associated with work-family conflict while negatively associated with perceived work ability, which in turn, was negatively associated with work-family conflict. Perceived social support magnified the effects of perceived work ability on work-family conflict.

Conclusion

Findings of this study shed light on a correlation between stress of COVID-19 and work-family conflict. Moreover, this study emphasizes the value of intervening individuals’ perceived work ability and increasing the ability of perceived social support in the context of COVID-19.

Keywords: stress of COVID-19, perceived work ability, perceived social support, work-family conflict

Introduction

Since 2020, the ongoing outbreak of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has swept the word. COVID-19 has forced a large portion of the global population to quickly transition to a new way of life;1,2 For instance, in order to limit the spread of outbreaks, the majority of the working population began to work from home3 to achieve flexibility, autonomy, and creativity.4 Meanwhile, work and private life are likely to be so highly intertwined due to the required home-based telework that the boundaries are blurred between the domains5–7 and the balance even may be upset between work and family, which in turn leads to work-family conflict.8

Work-family conflict is defined as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect”.9 The essence of work-family conflict is interaction between family and work, in that family can interfere with work and work can also interfere with family.9,10 Nowadays, work-family conflict as a common social phenomenon has an obvious impact on workers, families and organizations.11–13 The previous studies have shown that work-family conflict can lead to a variety of negative outcomes, such as depression, lower job engagement, low job and life satisfaction, job burnout and turnover intention.14–18 Given the potential harm, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic provided a unique opportunity to examine the roles of work ability and social support as antecedents for work-family conflict under a natural high stress social ecology.

Stress of COVID-19 and Work-Family Conflict

Stress refers to an adaptive process that tends to show a variety of reactions when the internal and external environment is unbalanced.19 Stressful life events have a significant influence on individuals’ psychological function and behavior and can be a catalyst for psychological behavioral problems including work-family conflict.20 According to the conflict theory, when any role experiences stress, time constraint and bad behavior outcome,9 it may affect the life quality of other roles5 and increase the risk of role conflict. The previous study has found that stress is positively associated with work-family conflict.21 It is worth noting that the outbreak and development of COVID-19 has become a global public health crisis and a major source of stress.22 Despite quite a few literature on work-family conflict and its underlying contributing factors like stress, however, little research has been done to examine this relation among Chinese adults who have been affected for their working from home by the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the analysis of literature, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Stress of COVID-19 is positively related to work-family conflict.

Perceived Work Ability as a Mediator

Perceived work ability, defined as individuals’ perception of the physical and mental demands at work and his or her ability to cope with these work demands.23 During this process, individuals will make a judgment about the ability to do the job with subjective feelings, and then respond accordingly. COVID-19 brings a host of problems, such as economic slowdown, individuals’ perceived stress and so on, that prompt individuals to re-examine their ability to work to gauge whether they are up to the challenge. Drawing from the cognitive models of stress and coping,24 cognitive evaluation plays a mediating role between stress and reaction. As an important factor in evaluating individuals’ own work ability,25 perceived work ability mediates the relationship between stress and work-family conflict and can be associated with stress.26,27 Perceived work ability can also subsequently affect various aspects of one’s life, including all walks of outcomes.28 Although not yet tested, it is reasonable to expect that perceived work ability as a mediator between stress of COVID-19 and work-family conflict. In the following section, previous research findings would be reviewed to support arguments.

First, according to the stress appraisal theory, when an individual is exposed to a stressor (such as COVID-19), he or she subjectively appraises the threat and stressfulness of the stressor and assess available resources to manage the stressor.29 Under the pressure of COVID-19, individuals have fewer resources to work, which in turn leads them to believe that they do not have enough capacity to cope with work. Second, low perceived work ability is more likely to develop a high level of work-family conflict. For individuals with low perceived work ability, there is an imbalance between work demand and work resources, with high work demand and low work resources.30 The boundary theory and conservation of resources theory holds that individuals have limited resources at a certain time. When they have fewer resources on one field (such as work field), they tend to use the resources allocated to another field originally (eg, family) for the purpose of resource preservation, which leads to the conflict between the two fields (ie, work and family).31–33 Thus, we posit the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: Perceived work ability is negatively related to stress of COVID-19 and work-family conflict.

Hypothesis 3: Perceived work ability mediates the effect of stress of COVID-19 on work-family conflict.

Perceived Social Support as a Moderator

Perceived social support is defined as individuals’ perception of having support or care from people with whom they live, such as families, friends, teachers, or other important people.34 Perceived social support is a theoretically broad and proximal resource,35 which has a protective effect on individuals’ mental health and can significantly predict individuals’ emotional and behavioral problems.36,37 Moreover, perceived social support is a protective resource and individuals with more perceived resources (eg, higher perceived social support) can induce them to experience lower work-family conflict.38

Although work ability may play an important role in the relationship between stress of COVID-19 and work-family conflict, not all individuals with low perceived work ability can experience work-family conflict. Perceived social support as an important protective resource factor may buffer the adverse outcomes of risk factors.39,40 Specifically, the “protective protective model” of human development points out that there are two hypotheses about the impact of two protective factors (such as perceived social support and perceived work ability) on outcome variables: the promotion hypothesis and the exclusion hypothesis. The promotion hypothesis refers to the mutual enhancement of the effects of two protective factors, which is a ‘icing on the cake’ effect on the outcome variables;41 The exclusion hypothesis refers to the weakening of the role of one protective factor on the other, and the impact on the outcome variable is a “beautiful beyond description” effect (Cohen et al, 2003). The buffer model of perceived social support holds that perceived social support can buffer the impact of negative factors (eg, work-family conflict) on physical and mental health.42,43 Furthermore, the protection-protection model argues that different protective factors interact in predicting individuals’ development, with one protective factor influencing the effect of the other on the outcome variable.44 In view of this, this study assumes that perceived social support has a significant regulatory effect on the intermediary path of ‘stress of COVID-19 → perceived work ability → work family conflict’, and only makes exploratory analysis on specific regulatory models (exclusion hypothesis vs promotion hypothesis) with making Hypothesis 4 as well.

Hypothesis 4: Perceived social support would moderate the association between perceived work ability and perceived social support.

The Present Study

Taken together, the current study first examined whether perceived work ability mediates the relation between stress of COVID-19 and work-family conflict (Figure 1). Secondly, we also examined whether perceived social support would moderate the association between perceived work ability and work-family conflict.

Figure 1.

The conceptual mediated moderation model.

Methods

Participants

The survey was approved by the ethics committee of the first author’s university and all participants provided informed consent. A total of 2679 Chinese adults participated from February 01–10, 2021 (ie, the second little wave of COVID-19 in Hebei, China). It coincided with the Chinese traditional festival (the Spring Festival), when the government adopted stricter controls to prevent the spread of the epidemic. Many enterprises, factories, schools, etc. adopted closed management and offline operations or teaching are directly suspended in areas with severe epidemic. In view of this, working from home has become a passive and necessary choice for many people, who may not have had to before. Participants (the students’ families, who are mainly their fathers, mothers, elder brothers and sisters or grandparents, have different occupational fields, genders and ages) took approximately 20 minutes to complete an online battery of questionnaires, which was disseminated in the following ways. Firstly, the web questionnaire was created on the questionnaire star website, and then the QR code images of the questionnaire were generated on the website. Finally, these QR code images were uploaded to WeChat, and the participants in the groups could answer the questionnaire by scanning the QR code. At the beginning of the questionnaire, participants were reminded of their informed consent along with the full confidentiality of survey data and freedom to withdraw at any time. The criteria for unqualified samples were less than 60 seconds to complete questionnaires with a total of 33 questions and regularity of answers, such as the same score in each item or a regular pattern of scores (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.). After removing invalid observations (ie, missing data or other errors), 2558 participants (54.1% female) were included in the final analyses and their occupations covered a wide range. The sample was composed of mostly between the ages from 40 to 49 (75.70%) and from all walks of life in China. See the participant demographics (Table 1) for details.

Table 1.

The Participant Demographics

| Occupation Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Employees of public organizations | 9.6 |

| Employees of medium or large private enterprises | 4.1 |

| Employees of small private enterprises | 10.9 |

| Individual businesses | 16.2 |

| Others (Teachers, doctors, nurses, etc) | 59.3 |

| Gender | Percentage |

| Male | 45.9 |

| Female | 54.1 |

| Region | Percentage |

| Urban | 16.5 |

| Sub-urban | 21.8 |

| Rural areas | 61.7 |

Research Instruments

Stress of COVID-19 Scale

The Coronavirus Stress Measure (CSM) was adapted from the 14-item perceived stress scale [PSS],45 to assess COVID-19 related to stress. The adapted CSM46,47 in the study included 5 items with scoring based on 5-point Likert scale, ranging between 1 = never and 5 = very often (e g, “How often have you been upset because of COVID-19 in the last month”), Cronbach’s alpha (α) = 0.90. In the Cronbach reliability analysis, high reliability requires the value of alpha coefficient to be higher than 0.8, along with good reliability just requiring α being 0.7–0.8.48 Furthermore, CFA showed that all the factor loadings ranged from 0.83 to 0.91, and the unidimensional model fitted the data well: χ2/df = 1.24, TLI = 0.989, CFI = 0.995, RMSEA = 0.069, SRMR = 0.021. AVE (mean variance extraction) and CR (combined reliability) were used to analyze the convergence validity. Generally, if AVE is greater than 0.5 and CR is greater than 0.7, the convergence validity is higher. For “Stress of COVID-19”, AVE = 0.65 and CR = 0.902 (1 factor with 5 items).

Perceived Work Ability Scale

The Perceived work ability Scale was adapted from the 14-item perceived work ability Index (WAI) questionnaire49 to assess the perceived work ability in COVID-19. The adapted perceived work ability scale in the study included 4 items (eg, “In the face of the epidemic, I am still able to meet the demands of my job”) with scoring based on 7-point Likert scale (1 = extremely uncharacteristic of me, 7 = extremely characteristic of me), the α of this study was 0.95. Furthermore, CFA showed that all the factor loadings ranged from 0.85 to 0.96, and the unidimensional model fitted the data well: χ2/df = 1.20, TLI = 0.995, CFI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.060, SRMR = 0.013. For “perceived work ability”, AVE = 0.827 and CR = 0.950 (1 factor with 4 items).

Perceived Social Support

The Chinese version50,51 of Perceived Social Support Scale52 was used to measure perceived social support. Perceived Social Support Scale consisted of 12 items (e g, “My friends really tries to help me”) and includes three dimensions: family support, friends’ support and other support. All items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), the α of this study was 0.96. Furthermore, CFA showed that all the factor loadings ranged from 0.71 to 0.93, and the three-factor model fitted the data well: χ2/df = 1.81, TLI = 0.969, CFI = 0.983, RMSEA = 0.078, SRMR = 0.033. For “perceived social support”, AVE = 0.723, 0.771, 0.770 and CR = 0.913, 0.931, 0.930 (3 factors with 12 items, each with 4).

Work-Family Conflict

The Chinese version of the Work-Family Conflict Scale53 was used to measure work-family conflict. The Chinese revised Work-Family Conflict Scale consisted of 10 items (e g, “The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life”) and included two dimensions: work-oriented family conflict and family-oriented work conflict. Individuals rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree), α = 0.92. Furthermore, CFA showed that all the factor loadings ranged from 0.85 to 0.96, and the two-factor model fitted the data well: χ2/df = 2.01, TLI = 0.976, CFI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.061, SRMR = 0.034. For “work-family conflict”, AVE = 0.584, 0.710 and CR = 0.874, 0.924 (2 factors with 10 items, each with 5).

Data Analysis

Tests of normality revealed that the study variables showed no significant deviation from normality (ie, Skewness < |3.0| and Kurtosis < |10.0|).54 Descriptive statistics were first calculated. PROCESS Models 4 and 14 macros for SPSS were used to test the mediation and moderated mediation models with 5000 random sample bootstrapping confidence intervals (CIs).55 All variables were standardized prior to being analyzed.

Result

Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables. Stress of COVID-19 was found to be negatively correlated with perceived work ability and perceived social support, while it was positively with work-family conflict. Perceived work ability was positively correlated with perceived social support. Perceived social support and perceived work ability were negatively correlated with work-family conflict.

Table 2.

Correlation Analysis

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stress of COVID-19 | 1.57 | 0.93 | 1 | |||

| 2. Perceived work ability | 4.86 | 1.14 | −0.20*** | 1 | ||

| 3. Perceived social support | 4.87 | 1.02 | −0.08*** | 0.43*** | 1 | |

| 4. Work-family conflict | 2.63 | 0.85 | 0.35*** | −0.27*** | −0.17*** | 1 |

Note: N = 2558. ***p < 0.001.

Testing for Mediation Effect

To test the mediating effect of perceived work ability (Figure 1), 4 linear regression models were run (Table 3) by Model 4 of the PROCESS macro.55 To see if there are differences between genders, we used gender as the control variable. Females tended to show lower perceived work ability (Models 2) compared to males. As Table 3 shows, Stress of COVID-19 was negatively related to perceived work ability (Model 2) and positively related to work-family conflict (Model 1, 3). Perceived work ability was negatively related to work-family conflict (Model 3). Accordingly, perceived work ability partial mediated the effect of stress of COVID-19 (indirect effect = 0.04, SE = 0.006, 95% CI = [0.030, 0.054]), accounting for 11.92% of the total effect. All findings supported our given Hypotheses 1–3.

Table 3.

Linear Regression Models

| Predictors | Model 1 (WFC) | Model 2 (PWA) | Model 3 (WFC) | Model 4 (WFC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |

| Gender | −0.04 [−0.11, 0.36] | −0.09* [−0.17, −0.02] | −0.06 [−0.13, 0.02] | −0.06 [−0.12, 0.02] |

| Stress of COVID-19 | 0.35*** [0.31, 0.38] | −0.20*** [−0.24, −0.16] | 0.30*** [0.27, 0.34] | 0.30*** [0.26, 0.33] |

| Perceived work ability | −0.21*** [−0.24, −0.17] | −0.18*** [−0.22, −0.14] | ||

| Perceived social support | −0.06** [−0.10, −0.02] | |||

| Perceived work ability × Perceived social support | −0.06*** [−0.09, −0.03] | |||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| F | 172.81*** | 55.84*** | 162.54*** | 103.81*** |

Note: Gender was dummy coded as 1 = male, 2 = female; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Abbreviations: WFC, Work-family conflict; PWA, Perceived work ability.

Analysis of Perceived Social Support as a Moderator

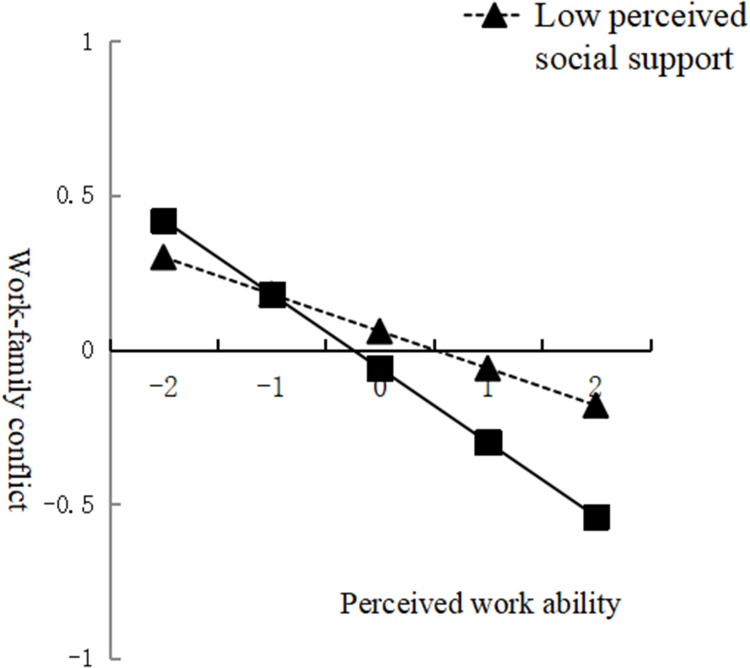

Model 4 (Table 3) examined the moderation effect of perceived social support between perceived work ability and work-family conflict (Figure 1). Results showed a significant, negative interaction between perceived work ability and perceived social support on work-family conflict (Model 4). The interaction effect is visually plotted in Figure 2. Simple slope tests revealed that perceived work ability had a significant negative effect on work-family conflict in high-level perceived social support and low-level perceived social support. The effect of perceived work ability on work-family conflict was weaker for college students with low levels of perceived social support (bsimple = −0.12, t = −4.41, p < 0.001) than for those with high levels of perceived social support (bsimple = −0.24, t = −9.16, p < 0.001). Results showed that the moderating pathways in Figure 1 were significant, suggesting perceived social support had a significant regulatory effect on the intermediary path of “stress of COVID-19 → perceived work ability → work family conflict”.

Figure 2.

Interaction graphs.

Discussion

While several empirical studies have shown the effect of stress on work-family conflict,56 the underlying mediating and moderating mechanisms remain less clear. Investigating the degree to which these underlying mechanisms of the work-family conflict of adults under the pressure of COVID-19 is vitally important. The present study examined and proposed a novel moderated mediation model to test how stress of COVID-19 generated work-family conflict, whether this relation was mediated by perceived work ability, and how perceived social support may moderate the relationship between perceived work ability and work-family conflict. Our results indicated that the impact of stress of COVID-19 on work-family conflict was significant and positive among Chinese adults, and this relation can be partially explained by reduced perceived work ability. That is, stress of COVID-19 decreased perceived work ability, which in turn, increased work-family conflict. Furthermore, the relation between perceived work ability and work-family conflict was moderated by perceived social support. These two relations became stronger for adults with higher levels of perceived social support.

Mediating Effect of Perceived Stress

Mediation results of this study suggested that low levels of perceived work ability were not only an outcome of stress of COVID-19 but also a partial catalyst for work-family conflict. These findings generally parallel prior literature57, and provide an outlook that stress of COVID-19 may be able to reduce individuals’ perceived work ability.58 The current COVID-19 is a rapidly evolving global challenge,59 it has caused severe disruptions in workplaces throughout the world and encouraged employees to work from home.60 However, employees may not have been well prepared for the unique challenges of home-based telework, considering that handful of them had experience with telework prior to COVID-19.7 This may result in employees not being equally rewarded for their efforts, which in turn leads to a decrease in perceived work ability.61 Furthermore, we found evidence that perceived work ability was negatively associated with work-family conflict. Low level of perceived work ability can cause individuals to believe that they do not have enough time and energy to complete work tasks,30 and can predispose them to use the resources originally allocated to the family, resulting in the conflict between family and work.33

It is also worth noting, however, that perceived work ability only partially mediated the association between stress of COVID-19 and work-family conflict. That is, stress of COVID-19 remained a significant, direct predictor of work-family conflict even upon controlling for perceived work ability. The remaining direct and positive association between stress of COVID-19 and work-family may suggest that COVID-19 related stress is uniquely salient risk factors that could significantly increase the prevalence of work-family conflict. There exist likely explanations for these findings. Under the stress of COVID-19, the global economy continues to slump and individuals face increased competition. Not only do they need to do their jobs well, but they also need to invest in improving their professional competitiveness.62 In addition to consuming a lot of resources at work, the stress of COVID-19 has also increased individuals’ resources at home and consumed a lot of their energy, such as children’s education. For families, stress of COVID-19 caused that more responsibility should be taken for children’s education with more time and energy. While the resource of individuals is limited,33 when more resources are needed in home and work areas, the result will be a conflict between work and home.

The Moderating Effect of Perceived Social Support

Our findings also suggest that perceived social support could moderate the relation between perceived work ability and work-family conflict. Both patterns were consistent with the risk buffer model63 and showed that the adverse effects of low perceived work ability on work-family conflict were weaker in adults with high perceived social support than in those with low perceived social support. Perceived social support may serve as a protective factor that mitigates the adverse effects of low levels of perceived work ability on work-family conflict. There is possible explanation for these findings. Individuals with low perceived work ability will think that they do not have enough time and energy to complete the work and tend to use the resources originally allocated to the family, leading to the conflict between work and family resources, and then the conflict between work and family.33 Perceived social support can provide individuals with more supportive resources, alleviate the conflict caused by resource insufficiency and imbalance, and then reduce work-family conflict. In other words, perceived social support, as a positive protective factor, will make individuals perceive more help and support from family and friends, buffer the resource allocation problem caused by low perceived work ability, and then reduce the work-family conflict. Thus, perceived social support, as a protective factor, may protect adults from the potential negative effects of low levels of perceived work ability.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are also some limitations of the present investigation that need to be noted. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits causal inference. Future research should employ experimental and longitudinal designs to better explain the causal direction. Second, like any study based solely on self-report for data collection, there may have been response biases and social desirability effects. The results should be replicated with other, more comprehensive or even representative samples in order to achieve even more generalizable conclusions. In addition, future research can also explore the mediating role and mechanism of other important variables between stress and work-family conflict. Third, the present study was conducted in Chinese adults’ samples, and the differences between Chinese and other cultures may be reflected in individuals’ different perceptions of the relationship between family and work, which potentially limits the generalizability and indicates that similar research should be conducted in samples of other countries.

Despite these limitations, the current study has several theoretical and practical contributions. From a theoretical perspective, this study further extends previous research by confirming the mediating role of perceived work ability and the moderating role of perceived social support. This will contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between stress of COVID-19 and work-family conflict. From a practical point of view, our research can provide some suggestions on how to reduce individual work-family conflict during the COVID-19. For example, measures should be taken to reduce the negative impact of COVID-19 stress on work, such as some economic policies, workload reduction, housekeeping training, etc. as well as increasing individuals’ level of perceived social support to promote the balance between work demand and work resources, thereby reducing work-family conflict.

Conclusion

In summary, although further research is needed, this study represents an important step in exploring how stress of COVID-19 may be related to work-family conflict among Chinese adults. The results show that perceived work ability serves one mechanism by which stress of COVID-19 is associated with work-family conflict. Interaction effects provide relevant implications showing that perceived social support may be coupled with perceived work ability to further mitigate the onset of work-family conflict. Future research can help the field design targeted interventions for tackling specific areas of concern, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as future issues to come.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and feedback on this article.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Anhui’s School-Enterprise Cooperation Project (2019xqsxzx94), Anhui’s Key Research Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (SK2020A0908), the Ministry of Education’s Construction Project of teaching and Research Team (19MY14419001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72164018), National Social Science Fund Project (BFA200065), and Jiangxi Social Science Foundation Project (21JY13).

Highlights

Stress of COVID-19, as a critical risk factor, was significantly and positively associated with work-family conflict as well as negatively associated with perceived work ability, which in turn, was negatively associated with work-family conflict. Perceived social support magnified the effects of perceived work ability on work-family conflict. Within the context of COVID-19, the potential utility of reducing work-family conflict by promoting perceived social support may reduce the psychopathological consequences of COVID-19.

Data Sharing Statement

The first author will make all raw data supporting their results freely accessible.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Jiangxi Normal University’s School of Psychology on October 9, 2020, in line with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol number is IRB-JXNU-PSY-2020029. Adolescents and their caregivers gave written informed permission for this research.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Peltz JS, Daks JS, Rogge RD (2020). Mediators of the association between covid-19-related stressors and parents' psychological flexibility and inflexibility: The roles of perceived sleep quality and energy. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitt JB, Breuer J, Wulf T. From cognitive overload to digital detox: psychological implications of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput Human Behav. 2021;124:106899. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mouratidis K, Papagiannakis A. COVID-19, internet, and mobility: the rise of telework, telehealth, e-learning, and e-shopping. Sustain Cities Soc. 2021;74:103182. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.103182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Putnam LL, Mumby DK. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Communication: Advances in Theory, Research, and Methods. Sage Publications; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen TD, Merlo K, Lawrence RC, et al. Boundary management and work-nonwork balance while working from home. Appl Psychol. 2020;70:1–25. doi: 10.1111/apps.12300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Labour Organization. Teleworking During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond: A Practical Guide. Publications of the International Labour Office; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerman K, Korunka C, Tement S. Work and home boundary violations during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of segmentation preferences and unfinished tasks. Appl Psychol. 2021;1–23. doi: 10.1111/apps.12335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gragnano A, Simbula S, Miglioretti M. Work-life balance: weighing the importance of work-family and work-health balance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):907–927. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Rev. 1985;10:76–88. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1985.4277352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tariq I, Asad MS, Majeed MA, et al. Work-family conflict, psychological empowerment, and turnover intentions among married female doctors. Bangla J Med Sci. 2021;20(4):855–863. doi: 10.3329/bjms.v20i4.54145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr JC, Boyar SL, Gregory BT. The moderating effect of work-family centrality on work-family conflict, organizational attitudes, and turnover behavior. J Manage. 2008;34(2):244–262. doi: 10.1177/0149206307309262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs JA, Gerson K. The Time Divide: Work, Family, and Gender Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu YX, Wang P, Huang C. Family, institutional patronage and work-family conflict: women’s employment status and subjective well-being in urban China. Sociol Stud. 2015;30(6):122–144. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alsam N, Imran R, Anwar M, et al. The impact of work family conflict on turnover intentions: an empirical evidence from Pakistan. World Appl Sci J. 2013;24(5):628–633. doi: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.24.05.13227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford MT, Heinen BA, Langkamer KL. Work and family satisfaction and conflict: a mete-analysis of cross-domain relations. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(1):57–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jawahar IM, Kisamore JL, Stone TH, et al. Differential effect of inter-role conflict on proactive individual’s experience of burnout. J Bus Psychol. 2012;27(2):243–254. doi: 10.1007/s10869-011-9234-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li ZS. Work family conflict and work engagement in special education teachers: emotional intelligence as a moderator. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2015;23(6):1106–1111. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2015.06.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Major VS, Klein KJ, Ehrhart MG. Work time, work interference with family, and psychological distress. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(3):427–436. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folkman S. Stress: appraisal and coping. Gellman MD, Rick Turner J, editors. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. New York: Springer New York; 2013:1913–1915. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Antecedent and outcomes of work-family conflict: testing a model of the work-family interface. J Appl Psychol. 1992;77(1):65–78. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel JS, Kotrba LM, Mitchelson JK, et al. Antecedents of work-family conflict: a mete-analytic review. J Organ Behav. 2011;32(5):689–725. doi: 10.1002/job.695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vannini P, Gagliardi GP, Kuppe M, et al. Stress, resilience, and coping strategies in a sample of community-dwelling older adults during COVID-19. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;138:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilmarinen J. Work ability- A comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35(1):1–5. doi: 10.2307/40967749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poel EV, Ketels M, Clays E. The association between occupational physical activity, psychosocial factors, and perceived work ability among nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(7):13125. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Håkansson C, Gard G, Lindegård A. Perceived work stress, overcommitment, balance in everyday life, individual factors, self-rated health and work ability among women and men in the public sector in Sweden – a longitudinal study. Archiv Public Health. 2020;78(1). doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00512-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vertanen-Greis H, Lyttyniemi EL, Uitti J, et al. Work ability of teachers associated with voice disorders, stress, and the indoor environment: a questionnaire study in Finland. J Voice. 2020;S0892199720303660. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomietto M, Paro E, Sartori R, et al. Work engagement and perceived work ability: an evidence-based model to enhance nurses’ well-being. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(9):1933–1942. doi: 10.1111/jan.13981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazarus RS. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. New York, NY: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernburg M, Vitzthum K, Groneberg DA, et al. Physicians’ occupational stress, depressive symptoms and work ability in relation to their working environment: a cross-sectional study of differences among medical residents with various specialties working in German hospitals. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011369. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashforth BE, Kreiner GE, Fugate M. All in a day’s work: boundaries and micro role transitions. Acad Manage Rev. 2000;25(3):427–491. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2000.3363315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matthews RA, Winkel DE, Wayne JH. A longitudinal examination of role overload and work-family conflict: the mediating role of interdomain transitions. J Organ Behav. 2013;35(1):72–91. doi: 10.1002/job.1855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carvalho S, Pimentel P, Maia D, et al. Características psicométricas da versão portuguesa da escala multidimensional de suporte social percebido (multidimensional scale of perceived social support - mspss). Psychologica. 2011;54:331–357. doi: 10.14195/1647-8606_54_13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.French KA, Dumani S, Allen TD, et al. A metal-analysis of work-family conflict and social support. Psychol Bull. 2018;144(3):284–314. doi: 10.1037/bul0000120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brissette I, Scheier MF, Carver CS. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):102–111. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye JJ. Perceived social support, enacted social support and depression in a sample of college students. Psychol Sci. 2006;29(5):1141–1143. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-6981.2006.05.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gan JH. Enhance perceived boundary control and reduce work family conflict-perspective of social support [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Wuhan: Central China Normal University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleiman EM, Riskind JH. Utilized social support and self-esteem mediate the relationship between perceived social support and suicide ideation. Crisis. 2013;34(1):1–8. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi ZF, Xie YT. Effect of problematic internet use on suicidal ideation among junior middle school students: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Dev Educ. 2019;35(5):581–588. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2019.05.09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (3rd ed). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aneshensel CS, Stone JD. Stress and depression: a test of the buffering model of social support. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(12):1392–1396. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290120028005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelatein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arslan G, Yildirim M, Tanhan A, et al. Coronavirus stress, optimism-pessimism, psychological inflexibility, and psychological health: psychometric properties of the coronavirus stress measure. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2020;1–17. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00337-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu Y, Ye B, Tan J. Stress of COVID-19, anxiety, economic insecurity, and mental health literacy: a structural equation modeling approach. Front Psychol. 2021;12:707079. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.707079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisinga R, Grotenhuis MT, Pelzer B. The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, cronbach, or spearman-brown? Int J Public Health. 2013;58(4):637–642. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuomi K, Ilmarinen J, Jahkola A, Katajarinne L, Tulkki A (1998). Work Ability Index (WAI). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang QJ. Perceived social support scale. Chin J Behav Med Sci. 2001;10(10):41–43. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan BB, Zheng X. Researches into relations among social-support, self-esteem and subjective well-being of college students. Psychol Dev Educ. 2006;22(3):60–64. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-4918.2006.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, et al. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199111)47:63.0.CO;2-L [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R. Development and validation of work family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):400–410. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J Educ Measure. 2013;51(3):335–337. doi: 10.1111/jedm.12050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin JF, Xu S, Wang YX. A comparison study of role overload, work-family conflict and depression between China and North America: the moderation effect of social support. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2014;46(8):1144–1160. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.01144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marklund S, Mienna CS, Wahlstrom J, et al. Work ability and productivity among dentists: associations with musculoskeletal pain, stress, and sleep. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2020;93(2):271–278. doi: 10.1007/s00420-019-01478-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jay K, Friborg MK, Sjogaard G, et al. The consequence of combined pain and stress on work ability in female laboratory technicians: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(12):15834–15842. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121215024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chattu VK, Adisesh A, Yaya S. Canada’s role in strengthening global health security during the covid-19 pandemic. Glob Health Res Policy. 2020;5. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00146-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mehta P. Work from home—Work engagement amid COVID-19 lockdown and employee happiness. J Public Affairs. 2021;21(4). doi: 10.1002/pa.2709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bethge M, Radoschewski FM. Adverse effects of effort-reward imbalance on work ability: longitudinal findings from the German sociomedical panel of employees. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(5):797–805. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0304-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao ZH, Zhao C. Why is it difficult to balance work and family? An analysis based on work-family boundary theory. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2014;46(4):552–568. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.00552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Masten AS Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]