Abstract

Objective.

To assess potential antagonist wear and survival probability of silica-infiltrated zirconia compared to glass-graded, glazed, and polished zirconia.

Methods.

Table top restorations made of 3Y-TZP (3Y), 5Y-PSZ (5Y), and lithium disilicate (LD) were bonded onto epoxy resin preparations. Each zirconia was divided into five groups according to the surface treatment: polishing; glaze; polishing-glaze, glass infiltration, and silica infiltration. The LD restorations received a glaze layer. Specimens were subjected to sliding fatigue wear using a steatite antagonist (1.25 ×106 cycles, 200 N). The presence of cracks, fractures, and/or debonding was checked every one/third of the total number of cycles was completed. Roughness, microstructural, Scanning electron microscopy, wear and residual stress analyses were conducted. Kaplan–Meier, Mantel–Cox (log-rank) and ANOVA tests were performed for statistical analyses.

Results.

The survival probability was different among the groups. Silica infiltration and polishing-glaze led to lower volume loss than glaze and glass-infiltration. Difference was observed for roughness among the zirconia and surface treatment, while lithium disilicate presented similar roughness compared to both glazed zirconia. Scanning electron microscopy revealed the removal of the surface treatment after sliding fatigue wear in all groups. Compressive stress was detected on 3Y surfaces, while tensile stress was observed on 5Y. Significance. 3Y and 5Y zirconia behaved similarly regarding antagonist wear, presenting higher antagonist wear than the glass ceramic. Silica-infiltrated and polished-glazed zirconia produced lower antagonist volume loss than glazed and glass-infiltrated zirconia. Silica-infiltrated 3Y and lithium disilicate restorations were the only groups to show survival probabilities lower than 85%.

Keywords: Ceramics, sliding contact, wear parameters, surface glass infiltration, 3Y-TZP, 5Y-TZP, lithium disilicate

1. Introduction

Yttria-stabilized Tetragonal Zirconia Polycrystals (Y-TZP) has become the material of choice for metal-free rehabilitations [1] due to its outstanding mechanical properties associated with a unique transformation toughening behavior [2]. Despite the best mechanical properties among dental ceramics, the first-generation zirconia, stabilized with 3% mol of yttria (3Y-TZP), has high opacity and requires a glass-ceramic veneering to reach more esthetical results [3]. But, because of lack of understanding in residual thermal stress states in porcelain-veneered zirconia systems [4–6], veneered zirconia restorations undergo chipping and delamination [7].

To overcome these issues, the second-generation zirconia was developed via crucial microstructural alterations, such as, decrease in alumina content and porosities by sintering at higher temperatures [8]. These modifications increased translucency, without jeopardizing the mechanical properties, which enabled their use as monoliths and long-span restorations in posterior areas [9–11].

Even greater translucency was achieved by the third-generation zirconia, in which the yttria content was increased to 4 mol% and 5 mol% partially stabilized zirconia (4Y-PSZ and 5Y-PSZ, respectively). The risen yttria amount allowed an increase in optically isotropic cubic phase, which led to an esthetical improvement [9]. The translucency achieved by 5Y-PSZ can be comparable or slightly below a lithium disilicate glass-ceramic [9, 12]. As a trade-off, cubic phase does not undergo phase transformation [13]. Owing to this absence of toughening mechanism, the mechanical properties of third-generation zirconia are not as high as its predecessors [8]. Hence, previous literature reports that the mechanical behavior of these zirconias can be comparable to a lithium disilicate glass-ceramic [12].

A glaze layer is traditionally applied on the cameo surface of monolithic ceramics restorations. Besides to ensuring high esthetic and natural appearance, the glaze layer prevents low temperature degradation (LTD) of zirconia [14]. However, previous studies have shown that glazed surfaces generated more pronounced wear on the antagonist than polished ones [15–17]. Furthermore, this layer can deteriorate with time in function, resulting in zirconia exposure [18]. This exposure of zirconia to the oral environment makes it susceptible to degradation and to crack nucleation [19]. In addition, a rough degraded surface has been directly linked to accelerated antagonist wear [20].

In this sense, the glass-graded zirconia was developed and have been extensively described for 3Y-TZP based systems [21–26]. The functional gradient benefits include better resistance to contact [22] and flexural damage [24] [27], as well as higher fatigue limit [28]. Moreover, the glass layer prevents LTD [29] and antagonist wear [25], and increases bondability to resin cement when applied on inner surface [30, 31]. The glass-graded structure has already been replicated on 5Y-PSZ, resulting in higher load-bearing capacity [32] and flexural strength [33] when compared to monolithic zirconia.

Campos et al. [34] proposed a zirconia surface modification through silica infiltration using a sol-gel technique. This method generates a silica-rich infiltrated layer of ~6 μm in depth [35]. The zirconium silicate formation (ZrSiO4) improved bond strength between zirconia and resin cement as well as structural reliability [34, 36] and stress distribution [37]. In addition, silica-based infiltration is another way to protect zirconia from oral environment exposure and to avoid LTD [38–40]. This method has been improved to be effectively applied in 40 min with the aid of a catalyst, without compromising the benefits of the technique [39]. However, the wear behavior of this modified surface and its effects on fatigue resistance of high cubic content zirconia are still unknown.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the survival probability and the wear potential to the antagonist of table top restorations prepared with silica-infiltrated second (3Y) and third (5Y) generation zirconias using sliding fatigue wear tests. Silica infiltration was compared to glass-graded, glazed, and polished zirconias to determine the best finishing protocols. A lithium disilicate group was also added for comparison since it is a high-strength glass-ceramic that is also indicated for table tops restorations. The tested hypotheses were that silica infiltration would lead to (1) less volume loss of the antagonist and (2) greater survival probability following sliding fatigue wear when compared to traditional glazed zirconia.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Specimen preparation

2.1.1. Specimen milling

Two hundred twenty table top preparations with a simplified occlusal reduction corresponding to a lower second molar [41] were milled from G10 fiber glass-reinforced epoxy resin (Protec, São Paulo, Brazil) as a dentin-analogous material [42]. The preparations were embedded in polyurethane cylinders (Axson Brasil, Sao Paulo, Brazil) 2 mm below the cement-enamel junction. One preparation was scanned (AutoScan-DS-EX; Tecnodrill, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil) and the obtained information was imported to a software (Exocad, exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) to design 1 mm-thick restorations. Then, these restorations were milled using a DM5 milling machine (Tecnodrill), as follows: 100 from 3Y-TZP (3Y) (VITA YZ HT, VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany), 100 from 5Y-PSZ (5Y) (KATANA Zirconia UTML, Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Aichi, Japan), and 20 from lithium disilicate (LD) (IPS e.max CAD HT, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein). The restorations were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with isopropyl for 10 min and left to dry. Zirconia restorations was divided into five groups, according to the surface treatment: silica infiltration, glass infiltration, polishing, glaze, and polishing followed by glaze. Lithium disilicate restorations received a glaze layer. The glass [22] and silica infiltration [39] processes were carried out on the pre-sintered zirconias. All samples were then sintered/crystallized following the manufactures recommendations (3Y: 1450°C for 2 h, 5Y: 1550°C for 2 h, LD: 850 °C for 10 min). A previously trained operator performed each of the finishing procedures described in the next section to ensure standardization.

2.1.2. Surface treatment procedures

To perform the silica infiltration, the silicic acid was obtained from hydrated sodium metasilicate (Na2SiO3.5H2O), following the same procedures described by [34]. Then, the pre-sintered zirconia restorations were placed in a plastic recipient filled with a sodium metasilicate solution [34]. The recipient containing the samples immersed in the sodium metasilicate solution was placed in an ultra-sonic bath (5 min) to ensure that the acid could infiltrate the specimens. The ammonium carbonate (100 g/L) was then added to the recipient as a catalyst. After 15 min, the sol had turned into gel, and the specimens were carefully removed from the recipient. The samples were placed in an oven at 100 °C for 20 min for water removal. he samples were subjected to this procedure twice. After the second drying, the restorations were sintered for 2 h at 1450/1550 °C (3Y and 5Y, respectively). In this technique, as the samples were immersed in the sol-gel, it infiltrated both top and cementation surfaces. Ramos et al. [39], whose steps were performed in our study, described the sol-gel method.

The preparation of glass-graded zirconia specimens followed a method described elsewhere [22, 33]. Zirconia restorations were pre-sintered at 1400°C for 1h in air, producing a somewhat porous template for glass infiltration. An in-house powdered feldspathic porcelain-like glass slurry with a 30 wt% solids loading was uniformly applied onto the top surface of the specimen with a brush using a standard enameling technique [43]. Glass infiltration and densification were carried out simultaneously for 2 h at 1450°C for 3Y, and at 1550°C for 5Y, with a heating/cool rate of 14°C/min.

Polishing procedures on the top surfaces were performed with the following sequence of decreasing grain abrasive instruments: Step 1 - Prepolishing (Suprinity Polishing Set, Vita Zahnfabrik, Germany) at speed of 7,000 to 12,000 rpm, followed by Step 2 - High-gloss at 4,000 to 8,000 rpm per 15 s each. The polishing instruments were mounted on a laboratory motor handpiece (MF Perfecta 9975, W&H, Laufen, Germany) and applied with light and steady pressure.

For glazing, the glaze powder (Vita Akzent, VITA Zahnfabrik, Germany) was mixed with a building liquid, and the resulting slurry was applied on the restorations top surfaces with a brush in the same way by one operator, in order to control the processing. The samples were fired in a vacuum furnace (Vita Vacumat 6000 MP) following the protocol recommended by the manufacturer (900°C/1min).

2.1.3. Cementation

G10 preparations were randomly divided into the 6 experimental groups. Their cementation surfaces were etched with 10% hydrofluoric acid (Condac porcelana, FGM Produtos Odontologicos Ltda, Joinville, Brazil) for 60 s, rinsed with air/water spray, and dried with oil-free air spray. A thin primer layer (Panavia V5 Tooth Primer, Kuraray) was applied with a micro brush and left to sit for 20 s. Then, a light air spray was applied.

Hydrofluoric acid (HF) was applied on the cementation surfaces of the restorations: 5%HF for 20 s on lithium disilicate glass-ceramic, and 2%HF for 10 s on silica infiltrated zirconia. The restorations were then rinsed with water/air spray and air-dried.

The cementation surfaces of the remaining groups were air-abraded with aluminum oxide (50 μm, Bio-Art, Sao Carlos, SP, Brazil) for 20 s (2.8 bar, 10 mm stand-off distance). Then, the samples were ultrasonically cleaned with isopropyl alcohol for 10 min and air-dried.

After that, all restorations were subjected to a MDP-based primer application (Clearfil Ceramic Primer Plus, Kuraray, Noritake). The primer was actively applied with a micro brush for 60 s and it was left to dry. In sequence, a resin cement (Panavia V5, Kuraray Noritake) was applied and the restorations were placed over the G10 preparations. A 750 g load was applied on the restorations and the cement excess was removed with a microbrush. Light polymerization was performed for 10 s each face (total of 50 s, VALO Corded, Ultradent, Utah, USA). The specimens were stored in distilled water at 37°C for 24 h to ensure hydration and complete resin cement polymerization prior to the sliding fatigue wear test.

2.2. Sliding fatigue wear and survival analysis

The specimens were subjected to sliding fatigue wear test in a mechanical machine (Biocylce V2, Biopdi, Sao Carlos, Brazil) using steatite spheres as indenters (r = 3 mm). Steatite was selected, as it allows test conditions standardization and a feasible results analysis [44]. One steatite sphere was used for each specimen (n = 220) and a screw held it in a mandrel with the same diameter (6 mm).The tests were performed in distilled water at room temperature, using a load of 200 N, frequency of 4 Hz, during 1.25 ×106 cycles. A complete cycle consisted of: indenter approaching and contact with the ceramic surface, loading to the prescribed load while sliding down the mesiobuccal cusp toward the central fossa (1 mm excursion) [16, 45], and unloading and lift-off. Sliding fatigue wear tests were interrupted every 416,666 cycles, and the specimens were inspected in a stereomicroscope (stereo Discovery.V12; Carl Zeiss) for damage assessments (cracks visible to the naked eye, cone cracks, fractures and debonding). If none of these were observed, the specimens were placed back to the fatigue machine and the test continued until the next 416,666 or until the test was complete. The water was renewed every stop. The number of cycles until failure was recorded and used for survival analysis

2.3. Wear analysis

To measure the volume loss and maximum wear depth of the antagonist, high-resolution (1 μm) tomography scanning of the antagonist wear crater was performed on a Lasers canner LAS-20 (SD Mechatronik, GMBH, Germany). The resulting information was exported as stereolithography files for wear measurements using a specific software (Geomagic Wrap 2017, 3D systems, South Carolina, USA). The original spherical topography was reconstructed by means of mesh editing, and the maximum wear depth and volume loss were obtained by comparing the same 3D models before and after reconstruction.

2.4. Roughness measurement

To determine the effect of the surface treatment and sliding fatigue wear on the topography and average roughness (Ra), five specimens of each group were analyzed in a contact profilometry (Mitutoyo SJ-410; Mitutoyo Corporation, Japan). The specimens were analyzed in two areas (worn and non-worn). Each specimen was subjected to three parallel readings and the mean among these readings was obtained per area. The average roughness parameter was measured according ISO4287/1997 (λc: 0.8 μm and λs: 2.5 μm).

2.5. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

A qualitative analysis of the restoration surface and sub-surface damage was performed with a scanning electron microscope (JSM-6360, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Sub-surface damage was investigated using a sectioning technique [46]. Specimens were embedded in epoxy resin and sectioned across the centerline of the wear scar along the sliding direction using a low-speed saw (Isomet 5000, Buehler, Illinois, USA). The cross-section surfaces were polished to 1 μm finishing prior to microscopic analysis. Representative failed restorations were selected and had their top surfaces analyzed in SEM for identification of fracture features and probable failure origin (Hitachi TM4000 II, Ibaraki, Japan).

2.6. Residual stress analysis

Three crystalline spectra of each zirconia specimen, on the worn and non-worn areas, were evaluated using a confocal type Raman spectroscopy equipment (LabRAM HR Evolution, Horiba, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil). The crystalline spectra were recorded between 140 and 500 cm−1 with an acquisition time of 30 s, 2 cycles and a slit size of 100 μm. Residual stresses were quantified according to the methodology described by Pezzoti and Porporati [47].

2.7. Statistical analysis

The number of cycles to failure data were used for the survival analysis by Kaplan–Meier followed by Mantel–Cox tests (log-rank test) for multiple pairwise comparisons (GraphPad Prism version 7, La Jolla, CA, USA). Volume loss, wear depth, and roughness data were analyzed for normality and equality of variances. The zirconia groups has their volume loss and wear depth data analyzed by two-way ANOVA (zirconia x surface treatment), and roughness was analyzed by three-way ANOVA (zirconia x surface treatment x sliding fatigue wear). Lithium disilicate data was compared to glazed zirconia groups. One-way ANOVA was used for wear depth and volume loss comparisons, and two-way ANOVA (ceramic x sliding fatigue wear) was used to analyze roughness. The respective pairwise multiple comparisons were performed with a Tukey’s or Dunnett’s tests. The significance level was set at 5% for all statistical tests.

3. Results

3.1. Survival probability

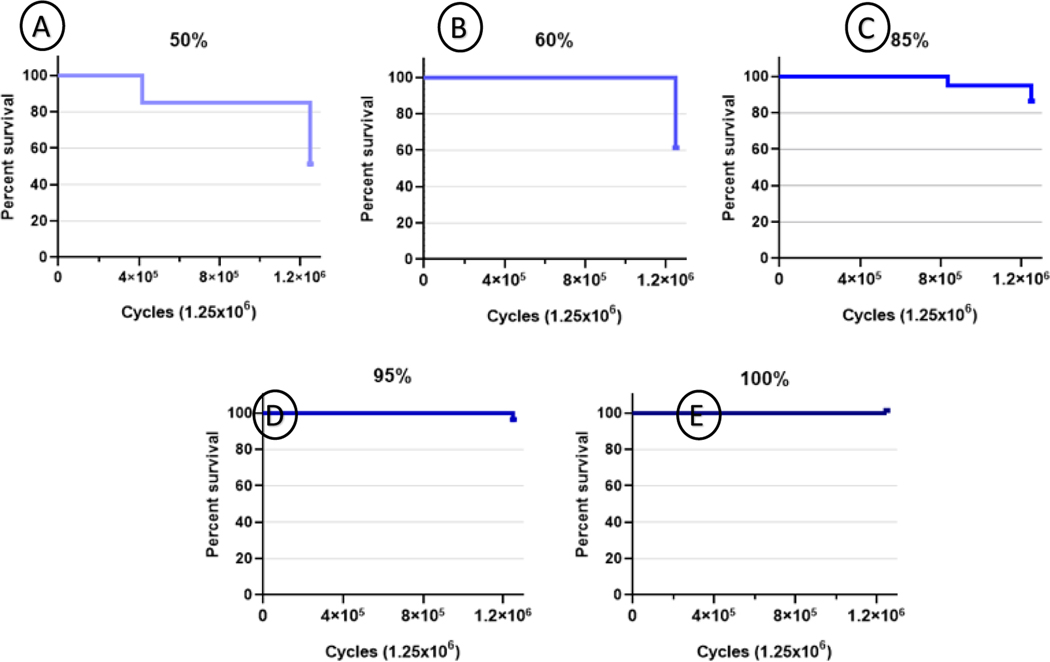

Survival probability curves according to Kaplan–Meier test are shown in Figure 1. Statistically significant differences among the experimental groups were detected by the Mantel–Cox statistic (Log-Rank test, X2 = 54.5, df = 10, p < 0.0001). The survival probabilities observed for each experimental group at 1.25 × 106 cycles are described in Table 1. Glass infiltrated, glazed, and polished-glazed 3Y samples survived the sliding fatigue wear protocol. Thus, no statistics could be computed for these groups. From the remaining groups, the highest survival probabilities were observed in polished 3Y, and polished, glazed, and polished-glazed 5Y, which reached 95%. Followed by glass-infiltrated and silica-infiltrated 5Y (85%). On the other hand, the lowest survival probabilities were observed for lithium disilicate (60%) and silica-infiltrated 3Y (50%). The predominant failure mode was edge-chipping, which were observed in 11 restorations: three from silica-infiltrated 5Y; two from silica-infiltrated 3Y, two from lithium disilicate; and one from each of the glazed, polished, polished-glazed, glass-infiltrated 5Y groups. Nine restorations presented cone cracks: six from lithium disilicate group; two from glass-infiltrated 5Y; and one from polished 3Y. Debonding was observed in eight restorations from silica-infiltrated 3Y group.

Fig. 1 –

Survival graphs of specimens according to the number of cycles (1.25×106). The groups regarding the survival rate: A) Silica-infiltrated 3Y (50%); B) Lithium disilicate (60%); C) Glass infiltrated and silica-infiltrated 5Y (85%); D) Polished 3Y, polished, glazed and polished-glazed 5Y (95%); E) Glass infiltrated, glazed and polished-glazed 3Y (100%).

Table 1 –

Number of survival restorations, survival probability, confidence interval (CI) and failure mode after 1.25×106 cycles, according to the ceramic and surface finishing.

| Groups | Survival restorations | Survival probability (%) (95% CI)* | Failure mode (number of restorations) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3Y silica infiltration | 10 | 50 (0.28 – 0.71)a | EC (2) D (8) |

| Lithium disilicate | 12 | 60 (0.38 – 0.81)a | EC (2) CC (6) |

| 5Y glass infiltration | 17 | 85 (0.69 – 1)ab | EC (1) CC (2) |

| 5Y silica infiltration | 17 | 85 (0.69 – 1)ab | EC (3) |

| 5Y polishing | 19 | 95 (0.85 – 1)b | EC (1) |

| 3Y polishing | 19 | 95 (0.85 – 1)b | CC (1) |

| 5Y glaze | 19 | 95 (0.85 – 1)b | EC (1) |

| 5Y polishing-glaze | 19 | 95 (0.85 – 1)b | EC (1) |

| 3Y glass infiltration | 20 | - | - |

| 3Y glaze | 20 | - | - |

| 3Y polishing-glaze | 20 | - | - |

Means that do not share a capital in the columns are significantly different. Values not calculated due to missing data (−). EC = edge chipping; D = debonding; CC= cone cracks.

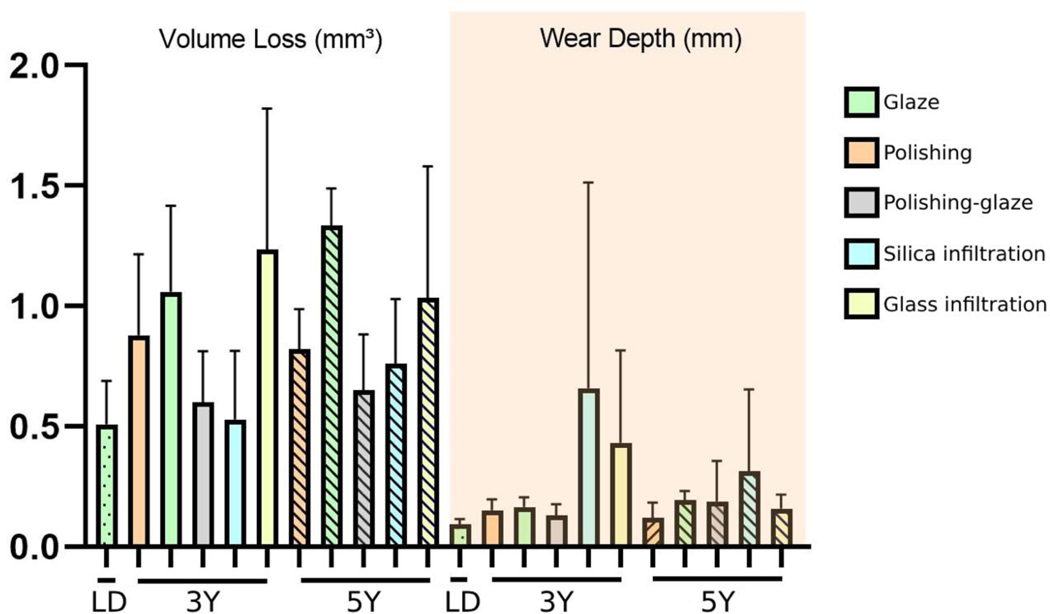

3.2. Wear analyses

The wear depth (mm) and volume loss (mm3) of the antagonist for each group are presented in Figure 2 as the mean and standard deviation. No statistical significance was detected in the wear depth analysis of zirconia groups for the tested factors (p > 0.05). Regarding volume loss, both 3Y and 5Y zirconias promoted similar results (p > 0.05). However, the volume loss (mm3) was significantly affected by the surface treatment (p = 0.001). Multiple comparisons showed that glaze and glass infiltration led to higher volume loss of the antagonist than silica infiltration and polishing-glaze. Polishing presented a statistically similar potential to antagonist wear as all the surface treatments. Glazed 3Y and 5Y promoted significantly higher wear depth and volume loss than lithium disilicate (p < 0.0001).

Fig. 2 –

Graph of averages and standard deviation of the antagonist volume loss (mm3) and wear depth (mm) according to the ceramic and surface finishing.

3.3. Surface roughness

The means and standard deviations of average roughness (μm) according to the ceramic, surface treatment and wear are described in Table 2. Among zirconia groups, all factors significantly affected roughness (p < 0.0001). 5Y zirconia (1.07a) showed higher roughness than 3Y zirconia (0.93b). Silica infiltration produced the roughest surfaces (1.23a), followed by polishing-glaze (1.04b), and glaze (1.03b). Polishing (0.90c) and glass infiltration (0.81c) led to the lowest values. The sliding fatigue wear significantly decreased roughness of all groups (1.52a to 0.49b). No difference in roughness was found among lithium disilicate and both glazed zirconia (p > 0.05). Similarly, the sliding fatigue wear also decreased their Ra values (1.51a to 0.72b).

Table 2 –

Means and standard deviation (SD) of average roughness (μm) and residual stress (GPa) according to the ceramic and surface finishing.

| Ceramic | Surface Finishing | Average Roughness (μm)±SD |

Residual Stress (GPa) ±SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-worn area | Worn area | |||

| 3Y | Glaze | 1.72 ± 0.18 | 0.33 ± 0.13 | −50 ± 3.2 |

| Polishing | 1.36 ± 0.41 | 0.46 ± 0.15 | −350 ± 5.3 | |

| Polishing-glaze | 1.51 ± 0.27 | 0.41 ± 0.13 | −44.4 ± 0.1 | |

| Silica infiltration | 1.88 ± 0.30 | 0.33 ± 0.16 | −44.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Glass infiltration | 0.94 ± 0.14 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | −233.33 ± 3.3 | |

|

| ||||

| 5Y | Glaze | 1.66 ± 0.43 | 0.41 ± 0.12 | 77.7 ± 3.2 |

| Polishing | 1.29 ± 0.29 | 0.50 ± 0.20 | 638.8 ± 10.5 | |

| Polishing-glaze | 1.61 ± 0.26 | 0.62 ± 0.18 | 77.7 ± 2.5 | |

| Silica infiltration | 1.97 ± 0.47 | 0.74 ± 0.20 | 77.7 ± 2.3 | |

| Glass infiltration | 1.24 ± 0.19 | 0.69 ± 0.16 | 172.2 ± 4.6 | |

|

| ||||

| LD | Glaze | 1.14 ± 0.32 | 1.39 ± 0.17 | - |

Legend: (−) indicates compression stress.

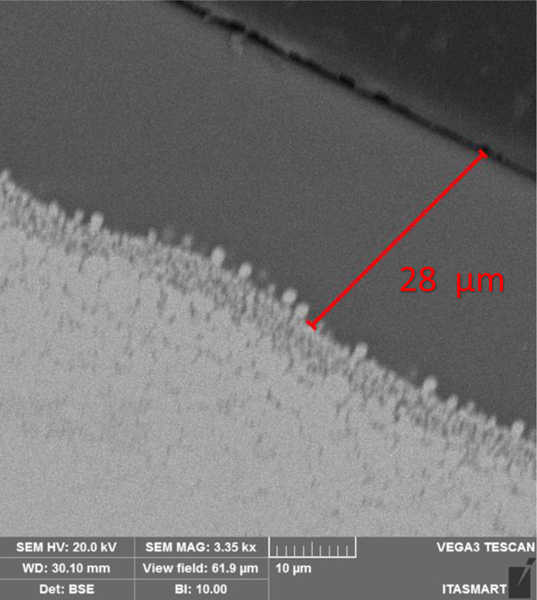

3.4. Scanning electron microscopy

Through the cross-section analysis the external glass and glaze layers thickness were assessed: glass-infiltrated 3Y and 5Y presented ~28 μm, while 3Y and 5Y glazed presented ~22 μm, as a representative sample shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3 –

Cross-section micrograph of representative specimen (glass-infiltrated 5Y) at 3.35k×: measurement of the external glass layer. The darker gray zones underneath the glass corresponds to the region where the glass infiltrated zirconia (white arrows).

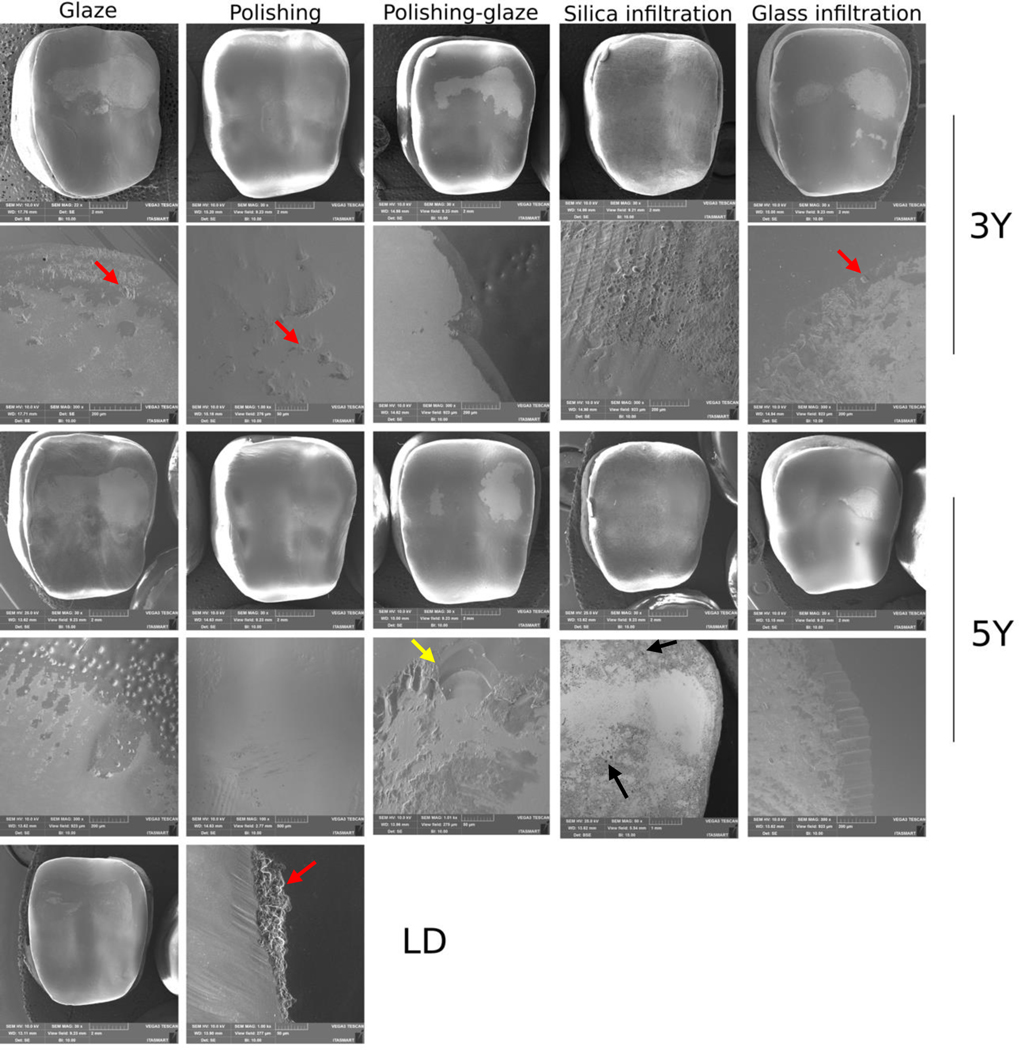

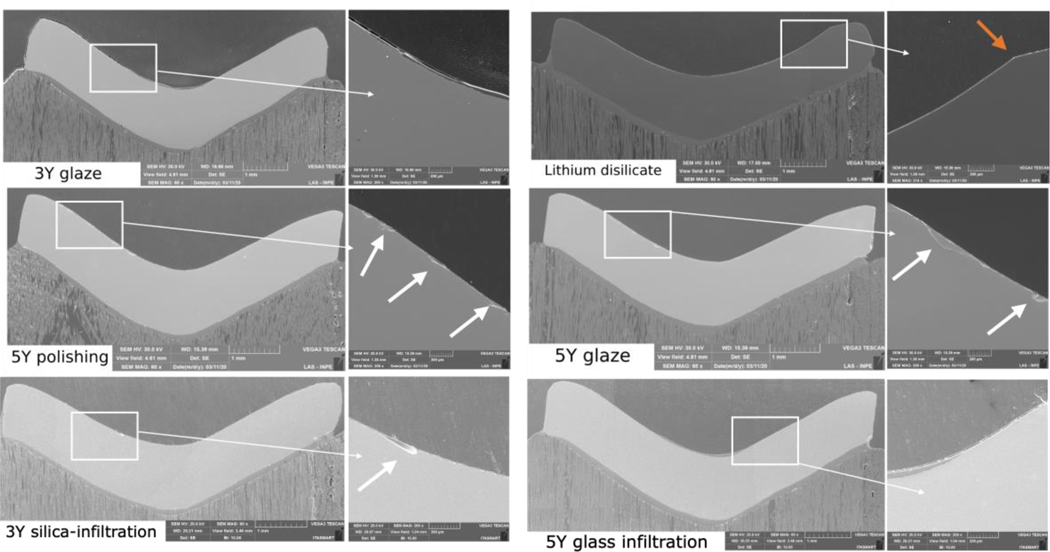

Figure 4 shows representative images of surface damage introduced by sliding fatigue wear. Different conditions were observed depending on the groups. The sliding fatigue wear removed the surface treatment regardless of the material. Higher magnification shows the boundary between worn and non-worn regions (white arrows), as well as the exposed zirconia.

Fig. 4 –

SEM micrographs of survived (1.25×106) restorations from each experimental group at different magnifications (22× - 1.00k×). The images reveal the different surface conditions and clearly depict the accentuated glaze and glass infiltration finishings removal, regardless of the ceramic, while the polished or silica-infiltrated specimens show less accentuated wear. At a higher magnification. the boundary between worn and non-worn areas are observed (white arrows). Numerous brittle chipping fractures (red arrows) and peeling cracks similar to fish scales (yellow arrow) are evidenced in some materials. Silica clusters are observed in the 5Y silica infiltrated image (black arrows).

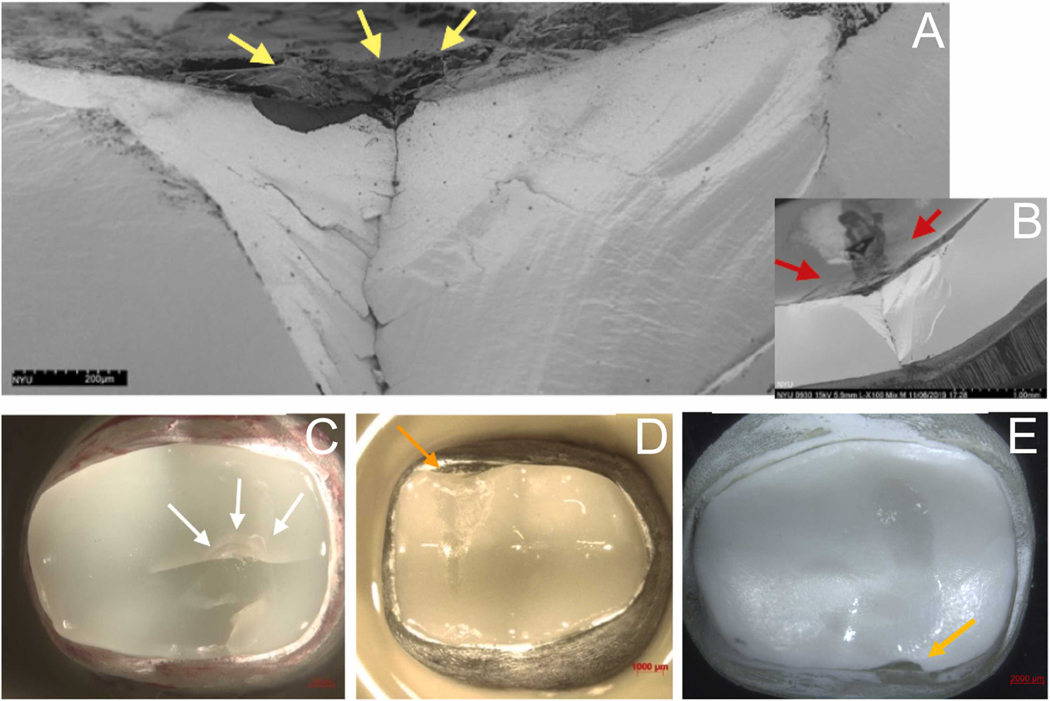

Surface and sub-surface analysis from cross-sectioned restorations showed different patterns. Representative images of the wear and damage features observed are shown in Figure 5. Similar features, i.e. no surface damage (in polished 3Y) or damage from the surface treatment removal (in glazed or glass-infiltrated 3Y), were observed among the samples. Besides that, additional small defects were observed on the surface of polished-glazed 3Y and 5Y, glass-infiltrated 5Y, and LD. Polished or glazed 5Y, and both silica infiltrated zirconia exhibited more prominent surface defects. All the restoration failure originated from the wear facet, as depicted in Figure 6.

Fig. 5 –

Cross-section micrographs of representative specimens at 60× and 200×. Different surface and subsurface features are observed according to the ceramic and finishing treatment. 5Y samples exhibited more surface damage than 3Y (white arrows). Lithium disilicate samples presented surface depression due to wear contact (orange arrow).

Fig. 6 –

SEM images of a failed glass-infiltrated 5Y specimen (A, B) and stereomicroscope images of representative failed restorations (C,D,E). Higher magnification (A) shows defects on the 5Y surface glass layer (yellow arrows). In B, the relationship between failure and occlusal wear scar (red arrows). which resulted in a cone crack failure. C shows cracks and a quasiplastic deformation at the load application area (white arrows) in a lithium disilicate restoration. Edge chipping fracture (orange arrows) in a glazed 5Y (D) and in a silica-infiltrated 3Y (E).

3.5. Residual stresses

The means and standard deviations of average residual stress (GPa) according to the experimental groups are described in Table 2. Compressive stresses were observed in 3Y, while tensile stresses were observed in 5Y.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the survival probability and potential wear to the antagonist of translucent zirconia (3Y and 5Y) table top restorations subjected to different surface treatment methods (polishing, glaze and infiltrations). Our results showed that silica infiltration led to one of the lowest volume loss of the steatite antagonist. However, the survival probabilities of silica-infiltrated samples were intermediate (5Y) to low (3Y) after the sliding fatigue wear protocol. These results made the first hypothesis to be accepted, while the second was rejected.

Silica infiltration and polishing-glazing produced the lowest volume loss values on the antagonist indenters. It is known that the glaze layer is removed during fatigue wear, which exposes a rough zirconia surface [18]. Roughness is directly related to the ceramic abrasiveness, since a rough surface increases the coefficient of friction and, as a result, it increases the wear rate [48, 49]. This explains the greater volume loss promoted by glaze or glass infiltration. Once debris were generated as the vitreous layer was removed, surface abrasiveness was increased [20]. SEM images (Fig. 4) confirm the surface treatment removal by sliding fatigue wear. Kaizer et al. [18] evaluated the wear rate of a glass-infiltrated zirconia prepared with the same method described in the present study. The authors observed the vitreous layer only up to 1,000 cycles. Beyond that, the glass was worn out, which agrees with our findings. On the other hand, if a polishing procedure is performed prior to glazing or glass infiltration, a smoother surface will be in contact with the antagonist when the glaze layer is removed, thus decreasing the wear rate [50]. In our study, the polishing and glazing combination led to one of the lowest antagonist volume loss (0.62 mm3). Therefore, the influence of the initial roughness one wear cannot be ruled out, as observed in a previous study [51]. The similarity in wear promoted by glazing (1.19 mm3), glass infiltration (1.13 mm3) and polishing (0.85 mm3) also demonstrates that.

Silica infiltration promotes silica clusters formation on the zirconia surface (Fig. 4 – orange arrows). Even though these clusters increased roughness (Table 2), they were softer than the steatite antagonist and quickly removed during fatigue wear, thus did not seem to interfere with the wear process. Furthermore, the silica infiltration method creates zirconium silicate within flaws and superficial porosities [35], which changes the defects shape, and makes them more resistant to removal during fatigue wear. Therefore, instead of faceted grains as in traditional zirconia, small spherical grains are observed in silica-infiltrated zirconia [36]. This might be related to the lower antagonist volume loss (0.64 mm3), since the microstructure predicts ceramic wear potential, as sharp edges of defects and porosities increase abrasiveness, as well as grain geometry [20]. In this case, ceramic microstructural features, rather than finishing, might be responsible for antagonist wear [20].

Some properties, such as hardness and elastic modulus, also influence the wear behavior [52, 53]. The elastic modulus of dental ceramics is associated with the surface stress concentration in response to the applied occlusal forces, which are lower in lower elastic modulus materials [54]. A previous study [55] observed a lower wear rate on the material with the lower elastic modulus, which corroborates with our findings, as the lithium disilicate (100 – 105 GPa) [56] led to lower volume loss on the antagonist than both zirconia (200 – 210 GPa) [8].

In general, 5Y showed more cracks and surface defects after sliding fatigue wear than 3Y, as shown in Fig. 5. This is due to the lower mechanical properties of 5Y-PSZ as compared to 3Y. The increase in yttria content allowed the increase in cubic phase to reduce the zirconia opacity. On the other hand, it also diminished strength and toughness, since the cubic phase does not undergo phase transformation [57]. Literature reports toughness of these material in a range of 3.5 – 4.5 MPa·m1/2 and 2.2 – 2.7 MPa·m1/2 for 3Y and 5Y, respectively [8]. Toughness is related to ceramics wear resistance and survival. The wear process in ceramic materials occurs from the cracks formation, with their subsequent propagation and eventual fracture [58] [59]. Thus, the ability of the ceramic material to resist crack propagation indicates its longevity. Our results showed that 5Y presented more failures than 3Y, as also reported in a previous study [60]. In this sense, eight lithium disilicate restorations failed. One should note that lithium disilicate toughness has been reported as 2.0 – 2.5 MPa·m1/2 [8]. A greater fatigue resistance and higher survival rates in zirconia crowns compared to glass-ceramic crowns were also previously reported [61–63].

The traditional glaze application, polishing, or combined did not cause deleterious effects on the restorations fatigue behavior, resulted in similar survival probabilities after sliding fatigue wear (Table 1), which was also observed by Zucuni et al. [64] and Zucuni et al. [65]. All glass-infiltrated 3Y samples survived the fatigue protocol, whereas glass-infiltrated 5Y had two failures. Besides the mechanical properties differences between 3Y and 5Y, these results are also related to the difference in graded layer thickness according to the zirconia microstructure. In spite of the similarity in the external glass layer thickness of ~28 μm (Fig. 3), glass infiltration in tetragonal zirconia promotes a graded layer of ~120 μm thickness [24], whereas in cubic zirconia, this layer is circa 50 μm [33]. Therefore, a thinner gradation layer may not be as effective in stress distribution as a thicker gradation layer.

Debonding was observed only for silica-infiltrated 3Y. Studies reported that this method improved the adhesion to resin cement [30, 34]. However, Ramos et al. [30] reported that the silica layer was not uniform on the zirconia surface. Thus, although the infiltration was performed by complete immersion, in our study, the cameo surface was facing upwards, while the inner surface was facing downwards. This may have affected the silica infiltration potential into the cementation surface. In this way, the adhesive interface performance was compromised, which caused 3Y debonding. This could have also damaged the load distribution capacity, since low and intermediate survival probabilities were observed for silica-infiltrated 3Y (50%) and 5Y (85%), respectively.

Dental ceramics usually present cracks in the area below the occlusal contact and/or at the cementation interface during fatigue. Crack propagation occurs as the load and number of cycles increases [66]. The image of the failed specimen suggests the failure initiated at the wear scar (Fig. 6). Sliding contacts also induce failures as partial cone cracks, arising from the occlusal contact and which propagate according to cyclic loadings [67]. A quasi plastic deformation on the contact area was observed (Fig. 6C), represented by the cracks induced by the sliding contact. Another failure due to sliding fatigue are cone cracks near the restoration edge, known as edge chipping [67], which was the most observed failure mode in this study (Fig. 6D) (Table 1). The edge chipping occurred as a result of the impact load at the cusp tip, previously to the sliding towards the central fossa.

Both zirconias showed residual stresses after sliding fatigue wear (Table 2). 3Y specimens, regardless of the surface finishing, presented compressive stresses as a result of their toughening mechanism, which prevents crack propagation and reduces fatigue failure susceptibility [2]. The grains reversion from the tetragonal to monoclinic was triggered by the contact with the indenter, which produced compressive stresses, as reported in a previous study [68]. On the other hand, 5Y zirconia does not present a toughening mechanism, which leads to a greater susceptibility to fatigue (Fig. 6). Thus, the tensile stresses observed on worn 5Y specimens, regardless the surface finishing, are a result of grains pullout [69], that occurred during the wear process. Both zirconia materials presented greater residual stress intensity in the polished groups, as demonstrated in a previous study [70]. On the other hand, the stresses are relieved by the glaze layer and heat treatment [71]. Even so, the residual stresses differences did not influence the wear potential, as both zirconias presented similar wear rates.

According to the literature, 1.25 × 106 cycles correspond to 5 years in function [72] and, as aforementioned, the glass/glaze layers are removed during fatigue wear after 1,000 cycles. Therefore, the smoothening of the zirconia surface prior to glaze/glass application is advised to minimize antagonist wear and avoid crack initiation and propagation. The average occlusal force peak in patients with temporomandibular disorders is 220 N, which can reach higher values during night tightening [73]. Thus, patient’s occlusion and habits must be considered for selecting the most suitable ceramic material for each rehabilitation case and predicting the treatment longevity. When it demands high support due to occlusal loads, a material with greater mechanical behavior associated with the treatment of parafunctional habits provide better prognosis. Even though our results demonstrate that both zirconia led to greater antagonist wear as compared to lithium disilicate, the obtained values are comparable with the wear rates between enamel versus enamel (0.36 mm3) and zirconia versus ceramic (0.33 mm3) presented in a clinical study after 2 years of follow up [74].

This study presents some limitations as the absence of simulating pH cycling and temperature. Hence, further clinical studies are needed to support the results of this in vitro study. Silica-infiltration was not the best surface treatment regarding survival probabilities, especially for 3Y, whereas it was demonstrated to be a good option regarding antagonist wear, generating the lower wear rate among the treatments. Despite the traditional finishing methods (glaze and polishing) have produced great survival results, potential wear of the antagonist dentition cannot be taken for granted. In this sense, silica-infiltration might be a promising treatment once the application technique is improved to ensure great bonding and stress distribution.

5. Conclusions

-Silica-infiltrated and polished-glazed zirconia resulted in less antagonist wear. However, silica infiltration reduced survival probabilities to lower than 85%.

-The zirconia type (3Y or 5Y) did not influence the antagonist volume loss, as the surface finishing was the determining factor for wear behavior in general. 3Y zirconia showed higher survival probabilities than 5Y zirconia and lithium disilicate.

-Lithium disilicate led to lower antagonist wear than both zirconias. LD table tops also presented survival probabilities lower than 85%.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Sao Paulo State Research Foundation - FAPESP (grants numbers: #2017/20633-9 and 2018/22627-9) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq (grant number: 408932/2016-3). YZ would like to thank the U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research for supporting our research activities (grant numbers R01DE026279 and R01DE026772).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Soares LM, Soares C, Miranda ME, Basting RT. Influence of Core-Veneer Thickness Ratio on the Fracture Load and Failure Mode of Zirconia Crowns. J Prosthodont. 2019;28:209–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Piconi C, Maccauro G. Zirconia as a ceramic biomaterial. Biomaterials. 1999;20:1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Benetti P, Della Bona A, Kelly JR. Evaluation of thermal compatibility between core and veneer dental ceramics using shear bond strength test and contact angle measurement. Dent Mater. 2010;26:743–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kim J, Dhital S, Zhivago P, Kaizer MR, Zhang Y. Viscoelastic finite element analysis of residual stresses in porcelain-veneered zirconia dental crowns. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2018;82:202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dhital S, Rodrigues C, Zhang Y, Kim J. Viscoelastic finite element evaluation of transient and residual stresses in dental crowns: Design parametric study. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;103:103545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rodrigues CS, Dhital S, Kim J, May LG, Wolff MS, Zhang Y. Residual stresses explaining clinical fractures of bilayer zirconia and lithium disilicate crowns: A VFEM study. Dent Mater. 2021;37:1655–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pang Z, Chughtai A, Sailer I, Zhang Y. A fractographic study of clinically retrieved zirconia-ceramic and metal-ceramic fixed dental prostheses. Dent Mater. 2015;31:1198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhang Y, Lawn BR. Novel Zirconia Materials in Dentistry. J Dent Res. 2018;97:140–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Harada K, Raigrodski AJ, Chung KH, Flinn BD, Dogan S, Mancl LA. A comparative evaluation of the translucency of zirconias and lithium disilicate for monolithic restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 2016;116:257–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gracis S, Thompson VP, Ferencz JL, Silva NR, Bonfante EA. A new classification system for all-ceramic and ceramic-like restorative materials. Int J Prosthodont. 2015;28:227–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Boulesteix R, Maître A, Baumard JF, Rabinovitch Y, Reynaud F. Light scattering by pores in transparent Nd:YAG ceramics for lasers: correlations between microstructure and optical properties. Opt Express. 2010;18:14992–5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yan J, Kaizer MR, Zhang Y. Load-bearing capacity of lithium disilicate and ultra-translucent zirconias. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2018;88:170–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang F, Inokoshi M, Batuk M, Hadermann J, Naert I, Van Meerbeek B, et al. Strength, toughness and aging stability of highly-translucent Y-TZP ceramics for dental restorations. Dent Mater. 2016;32:e327–e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Valentino TA, Borges GA, Borges LH, Platt JA, Correr-Sobrinho L. Influence of glazed zirconia on dual-cure luting agent bond strength. Oper Dent. 2012;37:181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Park JH, Park S, Lee K, Yun KD, Lim HP. Antagonist wear of three CAD/CAM anatomic contour zirconia ceramics. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;111:20–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Preis V, Grumser K, Schneider-Feyrer S, Behr M, Rosentritt M. Cycle-dependent in vitro wear performance of dental ceramics after clinical surface treatments. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2016;53:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sabrah AH, Cook NB, Luangruangrong P, Hara AT, Bottino MC. Full-contour Y-TZP ceramic surface roughness effect on synthetic hydroxyapatite wear. Dent Mater. 2013;29:666–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kaizer MR, Moraes RR, Cava SS, Zhang Y. The progressive wear and abrasiveness of novel graded glass/zirconia materials relative to their dental ceramic counterparts. Dent Mater. 2019;35:763–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Swain MV. Impact of oral fluids on dental ceramics: what is the clinical relevance? Dent Mater. 2014;30:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Oh WS, Delong R, Anusavice KJ. Factors affecting enamel and ceramic wear: a literature review. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:451–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang Y Making yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia translucent. Dent Mater. 2014;30:1195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang Y, Kim JW. Graded structures for damage resistant and aesthetic all-ceramic restorations. Dent Mater. 2009;25:781–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kim JW, Kim JH, Thompson VP, Zhang Y. Sliding contact fatigue damage in layered ceramic structures. J Dent Res. 2007;86:1046–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhang Y, Sun MJ, Zhang D. Designing functionally graded materials with superior load-bearing properties. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:1101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ren L, Janal MN, Zhang Y. Sliding contact fatigue of graded zirconia with external esthetic glass. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1116–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Oliveira-Ogliari A, Collares FM, Feitosa VP, Sauro S, Ogliari FA, Moraes RR. Methacrylate bonding to zirconia by in situ silica nanoparticle surface deposition. Dent Mater. 2015;31:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kim JW, Liu L, Zhang Y. Improving the resistance to sliding contact damage of zirconia using elastic gradients. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2010;94:347–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Villefort RF, Amaral M, Pereira GK, Campos TM, Zhang Y, Bottino MA, et al. Effects of two grading techniques of zirconia material on the fatigue limit of full-contour 3-unit fixed dental prostheses. Dent Mater. 2017;33:e155–e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Samodurova A, Kocjan A, Swain MV, Kosmač T. The combined effect of alumina and silica co-doping on the ageing resistance of 3Y-TZP bioceramics. Acta Biomater. 2015;11:477–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ramos NC, Kaizer MR, Campos TMB, Kim J, Zhang Y, Melo RM. Silica-Based Infiltrations for Enhanced Zirconia-Resin Interface Toughness. J Dent Res. 2019;98:423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chai H, Kaizer M, Chughtai A, Tong H, Tanaka C, Zhang Y. On the interfacial fracture resistance of resin-bonded zirconia and glass-infiltrated graded zirconia. Dent Mater. 2015;31:1304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kaizer MR, Zhang Y. Novel strong graded high-translucency zirconias for broader clinical applications. Dental Materials. 2018;34:e140–e1. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mao L, Kaizer MR, Zhao M, Guo B, Song YF, Zhang Y. Graded Ultra-Translucent Zirconia (5Y-PSZ) for Strength and Functionalities. J Dent Res. 2018;97:1222–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Campos TMB, Ramos NC, Machado JPB, Bottino MA, Souza ROA, Melo RM. A new silica-infiltrated Y-TZP obtained by the sol-gel method. Journal of Dentistry. 2016;48:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Toyama DY, Alves LMM, Ramos GF, Campos TMB, de Vasconcelos G, Borges ALS, et al. Bioinspired silica-infiltrated zirconia bilayers: Strength and interfacial bonding. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;89:143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Reis A, Ramos GF, Campos TMB, Prado P, Vasconcelos G, Borges ALS, et al. The performance of sol-gel silica coated Y-TZP for veneered and monolithic dental restorations. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;90:515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ramos GF, Ramos NC, Alves LMM, Kaizer MR, Borges ALS, Campos TMB, et al. Failure probability and stress distribution of milled porcelain-zirconia crowns with bioinspired/traditional design and graded interface. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;119:104438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chevalier J, Gremillard L, Virkar AV, Clarke DR. The Tetragonal-Monoclinic Transformation in Zirconia: Lessons Learned and Future Trends. Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 2009;92:1901–20. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ramos NC, Alves LMM, Ricco P, Santos GMAS, Bottino MA, Campos TMB, et al. Strength and bondability of a dental Y-TZP after silica sol-gel infiltrations. Ceramics International. 2020;46:17018–24. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Campos TMB, Ramos NC, Matos JDM, Thim GP, Souza ROA, Bottino MA, et al. Silica infiltration in partially stabilized zirconia: Effect of hydrothermal aging on mechanical properties. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;109:103774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Abu-Izze FO, Ramos GF, Borges ALS, Anami LC, Bottino MA. Fatigue behavior of ultrafine tabletop ceramic restorations. Dent Mater. 2018;34:1401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kelly JR, Rungruanganunt P, Hunter B, Vailati F. Development of a clinically validated bulk failure test for ceramic crowns. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2010;104:228–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhang Y, Chai H, Lawn BR. Graded structures for all-ceramic restorations. J Dent Res. 2010;89:417–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kaizer MR, Bano S, Borba M, Garg V, Dos Santos MBF, Zhang Y. Wear Behavior of Graded Glass/Zirconia Crowns and Their Antagonists. J Dent Res. 2019;98:437–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Preis V, Behr M, Kolbeck C, Hahnel S, Handel G, Rosentritt M. Wear performance of substructure ceramics and veneering porcelains. Dent Mater. 2011;27:796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Stappert CFJ, Baldassarri M, Zhang Y, Stappert D, Thompson VP. Contact fatigue response of porcelain-veneered alumina model systems. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 2012;100B:508–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Pezzotti G, Porporati AA. Raman spectroscopic analysis of phase-transformation and stress patterns in zirconia hip joints. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:372–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lawson NC, Janyavula S, Syklawer S, McLaren EA, Burgess JO. Wear of enamel opposing zirconia and lithium disilicate after adjustment, polishing and glazing. J Dent. 2014;42:1586–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Heintze SD, Cavalleri A, Forjanic M, Zellweger G, Rousson V. Wear of ceramic and antagonist--a systematic evaluation of influencing factors in vitro. Dent Mater. 2008;24:433–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Janyavula S, Lawson N, Cakir D, Beck P, Ramp LC, Burgess JO. The wear of polished and glazed zirconia against enamel. J Prosthet Dent. 2013;109:22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Alves LMM, Contreras LPC, Bueno MG, Campos TMB, Bresciani E, Valera MC, et al. The Wear Performance of Glazed and Polished Full Contour Zirconia. Braz Dent J. 2019;30:511–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Heintze SD, Zellweger G, Zappini G. The relationship between physical parameters and wear of dental composites. Wear. 2007;263:1138–46. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Phunthikaphadr T, Takahashi H, Arksornnukit M. Pressure transmission and distribution under impact load using artificial denture teeth made of different materials. J Prosthet Dent. 2009;102:319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tribst JPM, Alves LMM, Piva A, Melo RM, Borges ALS, Paes-Junior TJA, et al. Reinforced Glass-ceramics: Parametric Inspection of Three-Dimensional Wear and Volumetric Loss after Chewing Simulation. Braz Dent J. 2019;30:505–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Alves LMM, Contreras LPC, Campos TMB, Bottino MA, Valandro LF, Melo RM. In vitro wear of a zirconium-reinforced lithium silicate ceramic against different restorative materials. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;100:103403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Belli R, Wendler M, de Ligny D, Cicconi MR, Petschelt A, Peterlik H, et al. Chairside CAD/CAM materials. Part 1: Measurement of elastic constants and microstructural characterization. Dent Mater. 2017;33:84–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lim CH, Vardhaman S, Reddy N, Zhang Y. Composition, processing, and properties of biphasic zirconia bioceramics: Relationship to competing strength and optical properties. Ceramics International. 2022;48:17095–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].DeLong R, Douglas WH, Sakaguchi RL, Pintado MR. The wear of dental porcelain in an artificial mouth. Dent Mater. 1986;2:214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mecholsky JJ, Jr. Fracture mechanics principles. Dent Mater. 1995;11:111–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Zucuni CP, Venturini AB, Prochnow C, Rocha Pereira GK, Valandro LF. Load-bearing capacity under fatigue and survival rates of adhesively cemented yttrium-stabilized zirconia polycrystal monolithic simplified restorations. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;90:673–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Alves DM, Cadore-Rodrigues AC, Prochnow C, Burgo TAL, Spazzin AO, Bacchi A, et al. Fatigue performance of adhesively luted glass or polycrystalline CAD-CAM monolithic crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;126:119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Pereira GKR, Graunke P, Maroli A, Zucuni CP, Prochnow C, Valandro LF, et al. Lithium disilicate glass-ceramic vs translucent zirconia polycrystals bonded to distinct substrates: Fatigue failure load, number of cycles for failure, survival rates, and stress distribution. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;91:122–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Nishioka G, Prochnow C, Firmino A, Amaral M, Bottino MA, Valandro LF, et al. Fatigue strength of several dental ceramics indicated for CAD-CAM monolithic restorations. Braz Oral Res. 2018;32:e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zucuni CP, Dapieve KS, Rippe MP, Pereira GKR, Bottino MC, Valandro LF. Influence of finishing/polishing on the fatigue strength, surface topography, and roughness of an yttrium-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystals subjected to grinding. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019;93:222–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Zucuni CP, Pereira GKR, Valandro LF. Grinding, polishing and glazing of the occlusal surface do not affect the load-bearing capacity under fatigue and survival rates of bonded monolithic fully-stabilized zirconia simplified restorations. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;103:103528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Bergamo ETP, Bordin D, Ramalho IS, Lopes ACO, Gomes RS, Kaizer M, et al. Zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate crowns: Effect of thickness on survival and failure mode. Dent Mater. 2019;35:1007–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zhang Y, Sailer I, Lawn BR. Fatigue of dental ceramics. J Dent. 2013;41:1135–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Zhang F, Spies BC, Vleugels J, Reveron H, Wesemann C, Müller WD, et al. High-translucent yttria-stabilized zirconia ceramics are wear-resistant and antagonist-friendly. Dent Mater. 2019;35:1776–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Nogiwa-Valdez AA, Rainforth WM, Stewart TD. Wear and degradation on retrieved zirconia femoral heads. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2014;31:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Ho C-J, Liu H-C, Tuan W-H. Effect of abrasive grinding on the strength of Y-TZP. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2009;29:2665–9. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Zucuni CP, Guilardi LF, Rippe MP, Pereira GKR, Valandro LF. Fatigue strength of yttria-stabilized zirconia polycrystals: Effects of grinding, polishing, glazing, and heat treatment. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2017;75:512–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Sakaguchi RL, Douglas WH, DeLong R, Pintado MR. The wear of a posterior composite in an artificial mouth: a clinical correlation. Dent Mater. 1986;2:235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Nishigawa K, Bando E, Nakano M. Quantitative study of bite force during sleep associated bruxism. J Oral Rehabil. 2001;28:485–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Lohbauer U, Reich S. Antagonist wear of monolithic zirconia crowns after 2 years. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:1165–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]