Abstract

Monoallelic variants of CTCF cause an autosomal dominant neurodevelopmental disorder with a wide range of features, including impacts on the brain, growth, and craniofacial development. A growing number of subjects with CTCF-related disorder (CRD) have been identified due to the increased application of exome sequencing, and further delineation of the clinical spectrum of CRD is needed. Here, we examined the clinical features, including facial profiles, and genotypic spectrum of 107 subjects with identified CTCF variants, including 43 new and 64 previously described subjects. Among the 43 new subjects, 23 novel variants were reported. The cardinal clinical features in subjects with CRD included intellectual disability/developmental delay (91%) with speech delay (65%) and motor delay (53%), feeding difficulties/failure to thrive (66%), ocular abnormalities (56%), musculoskeletal anomalies (53%), and behavioral problems (52%). Other congenital anomalies were also reported, but none of them were common. Our findings expanded the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of CRD that will guide genetic counseling, management and surveillance care for CRD patients. Additionally, a newly built facial gestalt on the Face2Gene tool will facilitate prompt recognition of CRD by physicians and shorten a patient’s diagnostic odyssey.

Keywords: CTCF, gene, variant, phenotype, genotype, facial gestalt

Introduction

CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) is a DNA-binding transcription factor that regulates chromatin organization (Phillips & Corces, 2009). It is encoded by the CTCF gene located on chromosome 16q22.1. CTCF contains 727 amino acids and three functional domains: an N-terminal domain (residues 1–267), a central DNA-binding domain with 11 tandem Cys2-His2 (C2H2) zinc-fingers (ZFs) (residues 268–577), and a C-terminal domain (residues 578–727). In conventional C2H2 ZF proteins, each finger is comprised of two β strands and one helix, and generally interacts with three adjacent DNA base pairs. Two Cys from each strand and two His from the helix coordinate one Zn atom(Wolfe et al., 2000). The ZFs largely orchestrate the interaction between CTCF and DNA and play distinct roles in DNA sequence recognition, nonspecific protein-DNA interactions, and interactions with RNA (Hansen et al., 2019; Hashimoto et al., 2017; Kung et al., 2015; Nakahashi et al., 2013; Phillips & Corces, 2009; Rhee & Pugh, 2011; Saldana-Meyer et al., 2019). ZF3-7 play a critical role in recognizing the core DNA motif(Hashimoto et al., 2017). In contrast, ZF2 and ZF8-9 interact with the phosphate backbone in a sequence-independent manner and may affect the stability of CTCF-DNA interactions rather than the specificity of the interactions(Hashimoto et al., 2017). While the NMR solution structures of each ZF unit have been solved, details of protein-DNA interactions mediated by ZF1 and ZF10-11 have not been extensively characterized (Hashimoto et al., 2017). CTCF also interacts with RNA (Kung et al., 2015), and the interaction is mediated through ZF1, ZF10, ZF11, and 38 amino acids in the C-terminus adjacent to the ZF domain (Hansen et al., 2019; Saldana-Meyer et al., 2019).

Gregor et al (Gregor et al., 2013) first reported in 2013 that heterozygous, loss of function (LOF) pathogenic CTCF variants caused variable intellectual disability (ID), microcephaly, and growth retardation in four individuals. In 2019, a multicenter study (Konrad et al., 2019) reported 39 individuals with CTCF variants and neurodevelopmental disorders and expanded the genotype and phenotype of CRD. In 2021, a large-scale exome sequencing study that aimed to identify genes implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders (Wang et al., 2020) reported clinical information for 13 additional cases of CRD. In addition, a few case reports have described the clinical features of subjects with CRD (Bastaki et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019; Hiraide et al., 2021; Hori et al., 2017). Based on these publications, CRD is currently described as an autosomal dominant neurodevelopmental disorder associated with ID, feeding difficulties/failure to thrive (FTT), microcephaly, and behavioral abnormalities. Other features that are commonly described as being characteristic of this disorder include recurrent infections, cardiac defects, cleft palate, and hearing loss.

Exome sequencing has been extensively utilized in diagnosing patients with multisystemic symptoms, especially nonspecific neurodevelopmental disorders (Srivastava et al., 2019). This has led to a less biased ascertainment of a growing number of CTCF variants. The broad variability of CRD symptoms has made the surveillance and management for this condition unclear; as reported by patients and their physicians; and uncertainty related to disease characterization, pathogenicity and outcomes can bring distress and anxiety to patients and their families (Pollard et al., 2021). To address this, we performed an integrative analysis of previously reported cases plus 43 new subjects with CTCF variants. We provide a comprehensive review of CRD by examining clinical data, investigating the biochemical properties of mutant proteins present in CRD patients, classifying variants using the ACMG variant curation guidelines, and performing detailed facial analyses of individuals with CRD.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee of the Emory University (IRB approval #00000168). We recruited 46 subjects with reported CTCF variants from August 2020 to April 2022 through the CTCF Families Facebook© group, the laboratory GeneDx, Genematcher, and the Emory CRD Center website (www.ctcfemory.com). In the rest of the manuscript, we will refer to these 46 subjects as the “Emory cohort”.

Data collection

Subjects from the Emory cohort were asked to fill out a questionnaire using REDCap. The questionnaire included the following sections: demographics, CTCF variant, prenatal and birth history, medical history, developmental history, learning and therapies, and family history. (Appendix S1) For approximately half of recuited subjects, their physicians were asked to provide additional medical information or record for data accuracy and clarification, such as genetic report, imaging report or neurodevelopment evaluation, and so on. All published cases with detailed descriptions of the phenotypes and CTCF variants were also reviewed. The variants present in the Emory cohort and in published subjects were classified using ACMG variant curation guidelines (Richards et al., 2015). Only 102 subjects with pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants were used to create a clinical profile for CRD.

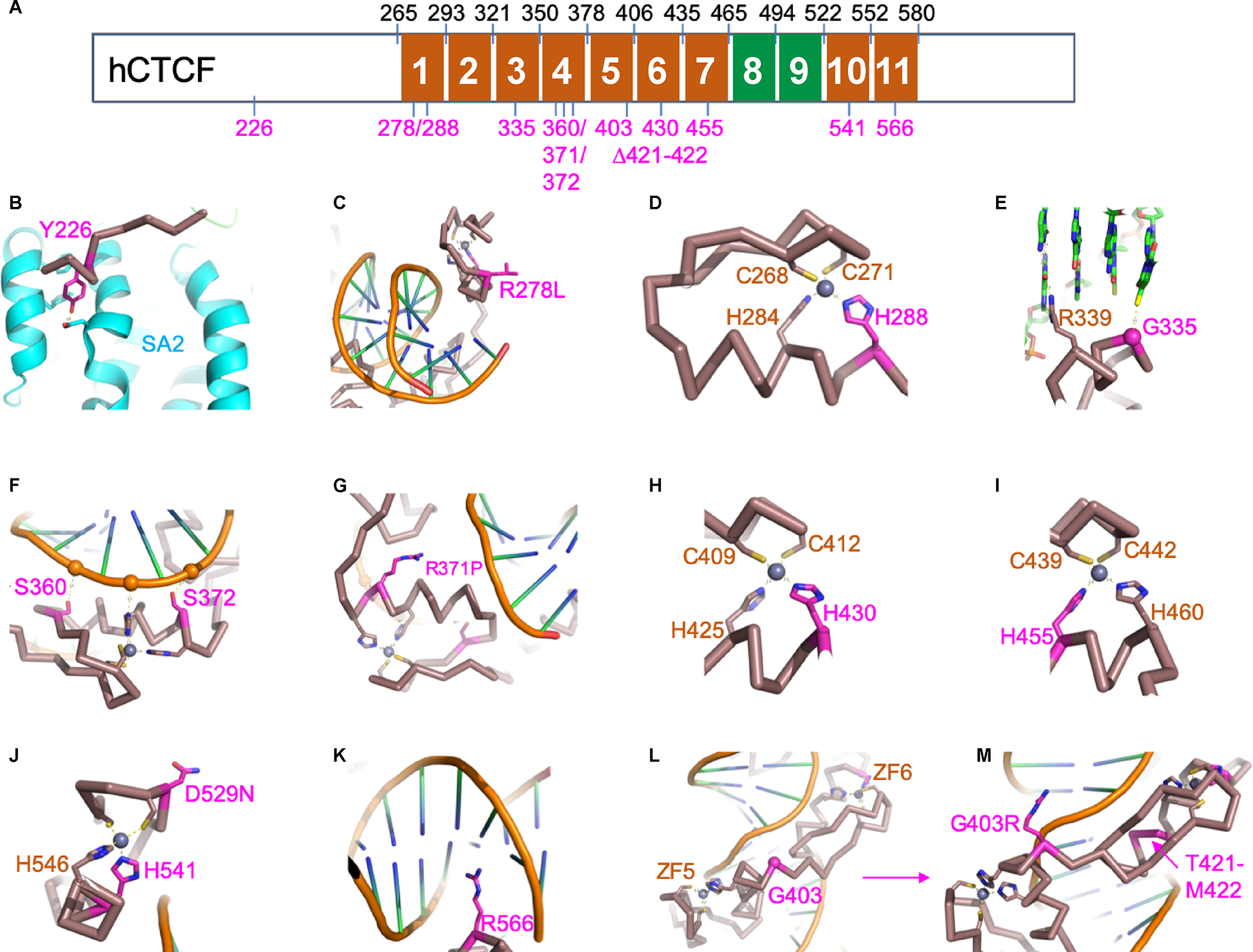

Computational modeling of CTCF protein to evaluate structural effects of CTCF variants

To assist with variant curation, the computational protein structure modeling of the CTCF protein was generated for 14 variants that were detected in singular cases. The potential effects of 10 novel missense variants, one novel in-frame deletion variant, and three previously reported VUS were examined in the context of available CTCF protein structures, including cohesin-CTCF peptide complex (PDB 6QNX) (Li et al., 2020) and the core DNA binding domain containing fragments of ZF2-7, ZF3-7, ZF4-7, ZF4-9, ZF5-8 and ZF6-8 in complex with DNA (Hashimoto et al., 2017). Substitutions and side chain adjustments were made in PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC), which was further utilized to produce the molecular graphics.

Facial gestalt

A facial profile for CRD was investigated via DeepGestalt using the Face2Gene tool (Latorre-Pellicer et al., 2020; Mak et al., 2021; Martinez-Monseny et al., 2019). DeepGestalt training was based on facial photographs from subjects of various ages. We used 18, 12, 9, 6, and 9 photographs for each of the age groups (0–3, 4–6, 7–11, 12–18, and >18 years old, respectively). Thirty-six photographs were uploaded to the Face2Gene platform to create a distinctive mathematical representation of a CRD facial gestalt. Then, the Face2Gene team provided photographs of age- and sex-matched healthy controls to conduct experiments on the Face2Gene RESEARCH feature. The area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated to determine how successfully the tool was able to differentiate subjects with CRD from healthy controls using the composite photo. Once the algorithm learned to identify subjects with CRD, previously unused pictures were uploaded by our clinical team to validate the tool. To keep the identities of subjects anonymous, only the CRD team had access to facial photos of the Emory cohort. Permission was obtained from parents separately for the photos published in this paper.

Results

Comprehensive clinical analysis of 107 CRD subjects

Forty-six subjects in the Emory cohort were consented and filled out the questionnaire. Forty three of them were new subjects and three were previously reported but were included as part of the Emory cohort due to significant clinical updates; two of these were reported by Konrad et al (Konrad et al., 2019) (subjects 5 and 13 listed in the Emory cohort) and one reported by Wang et al (Wang et al., 2020) (subject 2). Sixty-one additional subjects with available clinical information from the previous literature (Bastaki et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019; Gregor et al., 2013; Hiraide et al., 2021; Hori et al., 2017; Konrad et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020) were analyzed further (Supplemental Table S1). After reviewing a total of 107 subjects and their CTCF variants (46 from the Emory cohort and 61 from the published literature), 102 subjects with pathogenic or likely pathogenic classification (P/LP) CTCF variants were analyzed to create a CRD profile (Supplemental Figure S1). The remaining five subjects had three variants classified as variants of unknown significance (VUS) and are further discussed below.

The subjects from the Emory cohort were recruited from the United States, Canada, Denmark, England, France, Israel, Italy, Norway and Spain. The countries of origin of the combined subjects also include China, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates. Of these, 45 were female (44%), and the mean age was 10.5 years.

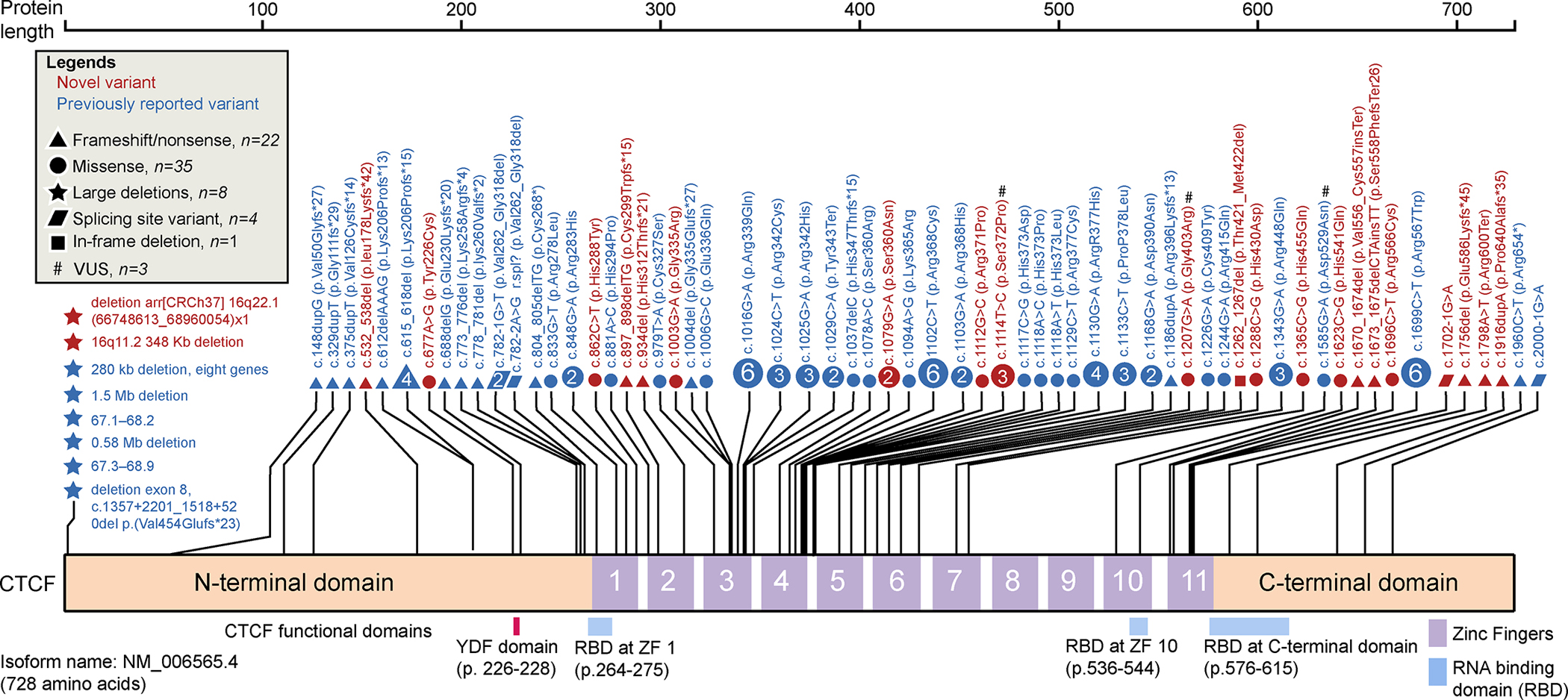

Genotypic spectrum: CTCF variants are largely de novo and encompass the entire CTCF gene

We detected 35 variants in the CTCF gene, 23 of which are novel, in the 43 new subjects of the Emory cohort. Seventy-six CTCF variants have been identified so far in CRD patients, 53 of which were identified in previous studies. (Figure 1; Supplemental Table S20). Six out of the 76 variants were not included in this study due to lack of clinical data. (Iossifov et al., 2014; Meng et al., 2017; Retterer et al., 2016; Squeo et al., 2020; Willsey et al., 2017). Eighty-six out of 107 subjects (80%) carried de novo CTCF variants, nine subjects inherited the variants from their parents with two parents were in a mosaic status. For the remaining 12 subjects, parental samples were unavailable for testing to determine inheritance. The variants included four nonsense, 35 missense, 18 frameshift, four splice site, one in-frame deletion, and eight large deletions. Figure 2 indicates the location and frequency of the ZF variants with respect to critical amino acids required for the folding or DNA binding of Zn fingers. The most common variants are c.1016G>A (p.Arg339Gln), c.1102C>T (p.Arg368Cys) and c.1699C>T (p.Arg567Trp), each found in six different subjects. These arginine residues are involved in DNA guanine interactions, and thus the substitutions would result in loss of specific DNA interactions.

Figure 1.

Schematic of CTCF functional domains and CTCF variant distribution and characteristics. All analyzed CTCF variants (107 subjects and 70 variants). Variants are plotted based on the CTCF isoform amino acid position (Uniprot identifier P49711, RefSeq mRNA ID: NM_006565.4) and colored based on whether they are novel (red) or previously reported (blue). A # indicates a variant of unknown clinical significance (VUS). The types of variants are marked using different shapes. Each shape represents a unique variant. If a variant was recurrent, the number within the shape indicates the number of cases in which that variant was found; a shape that does not contain a number indicates the variant was found in a single case. The nucleotide location and amino acid position relative to the long CTCF isoform are marked for each variant. Large deletion variants are plotted on the far left.

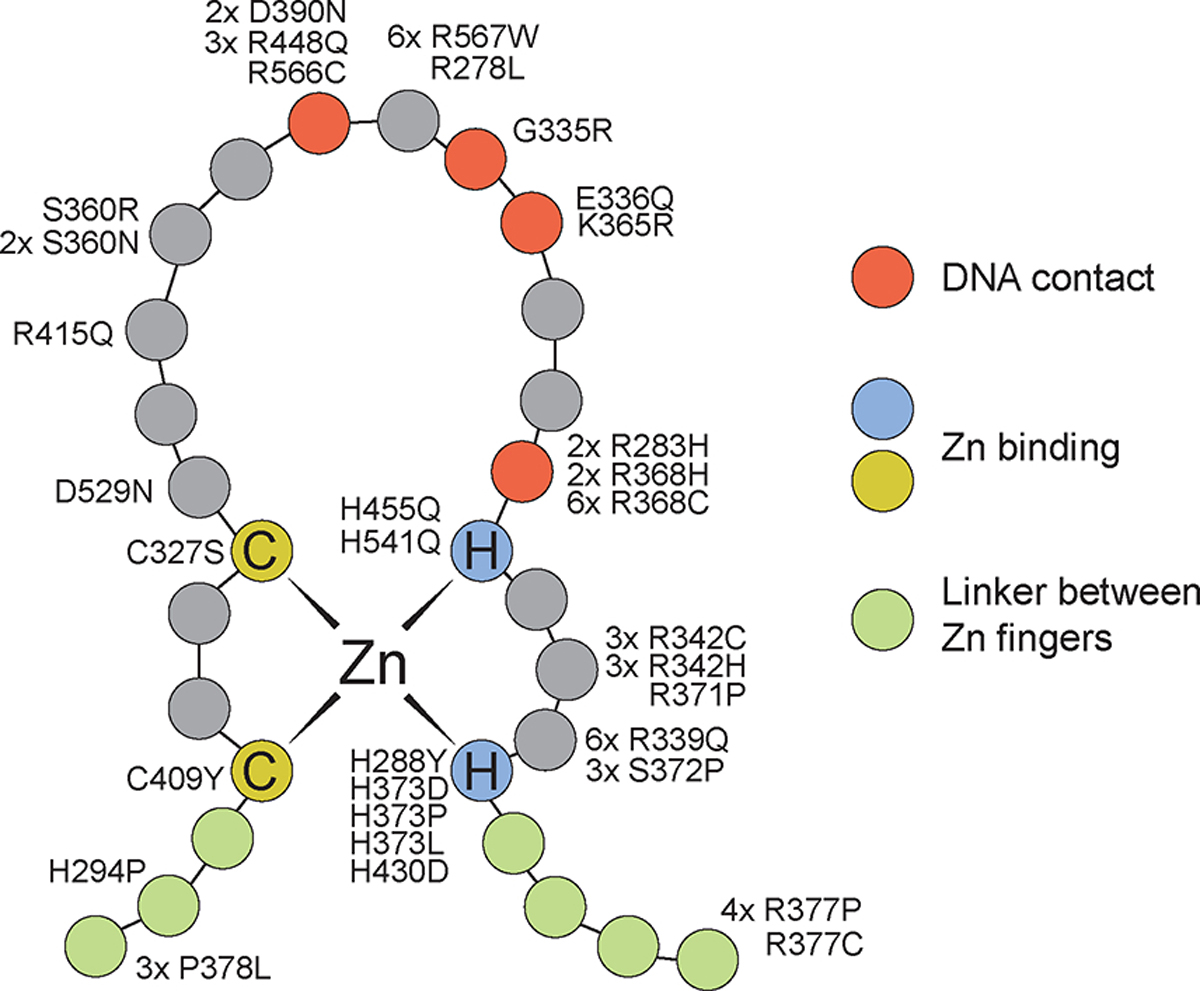

Figure 2.

Location of CTCF variants with respect to Zn finger functional features. CTCF contains 11 Zn fingers separated by short linker sequences. Each finger contains two Cys and two His residues that coordinate one Zn atom. Residues between the second Cys and the first His fold into an alpha helix structure that recognizes specific bases in the major groove of the DNA. The figure shows the location of the different CTCF variants found in CRD patients with respect to the combined structure of all CTCF 11 Zn fingers.

Sequence variants were classified according to the standard ACMG/AMP variant classification framework(Richards et al., 2015), while copy number variation was classified according to ACMG/ClinGen recommendations (Riggs et al., 2020) (Supplemental Table S2).To assist with variant curation, computational protein structure modeling of the CTCF protein was generated. The potential effects of 10 novel missense variants, one in-frame deletion variant, and three previously reported VUS were evaluated (Figure 3). Four variants, at residues His288, His430, His455, and His541, are located within the ZFs athistidine residues crucial for the coordination of Zn binding. Six variants substitute or delete residues that interact with DNA, including Gly335, Ser360, Arg371, Ser372, Thr421_Met422, and Arg566. Three variants involving Tyr226, Arg278, and Asp529 likely affect non-DNA binding interactions. Based on available clinical information and protein modeling data, 67 variants were classified as P/LP and three remain VUS (Supplemental Table S2). Two VUS in the Emory cohort are c.1207G>A (p.Gly403Arg), found in one patient and c.1114T>C (p.Ser372Pro), found in three members of one family. Konrad et al (Konrad et al., 2019) included three subjects with VUS in their analysis. However, through our variant curation, c.833G>T (p.Arg278Leu) and c.1078A>C (p.Ser360Arg) were upgraded to LP. The variant c.1585G>A p.(Asp529Asn) was still classified as VUS. Only those cases with a variant that we classified as P/LP were included in the analysis below.

Figure 3.

Structural information of CTCF variants derived from existing CTCF structures. (A) The schematic 11 tandem zinc fingers (ZF) of human CTCF protein (hCTCF). The amino acid numbers in black indicate each ZF’s starting and ending residue. The numbers in magenta indicate the 14 variants examined in this study. We note that there are no variants observed in ZF2 and ZF8-9 so far (colored in green). (B) Tyr226 is located in the interaction interface with SA2 subunit of human cohesin (colored in cyan). The replacement of Tyr226 with cysteine (Y226C) would disrupt the interaction. (C) The side chain of Arg278 of ZF1 points away from DNA and its substitution with leucine (R278L) creates a surface hydrophobic residue that might affect other (non-DNA binding) interactions. (D) His288 of ZF1 is one of the four Zn-coordination ligands, and H288Y would result in loss of Zn ion binding and affect the stability. (E) Gly335 of ZF3 lies in the interface with DNA, and G335R introduces a bulky residue that could be deleterious for DNA binding. (F) Ser360 and Ser372 of ZF4 are involved in interactions with DNA backbone phosphate groups. The changes of S360N and S372P might be disruptive for DNA binding. (G) The substitution of Arg371 of ZF4 with proline (R370P) would introduce a kink in the DNA binding helix and affect the overall structure of ZF4. (H) His430 of ZF6 is one of the four Zn-coordination ligands. (I) His455 of ZF7 is one of the four Zn-coordination ligands. (J) Asp529 of ZF10 points away from DNA binding and its substitution with asparagine (D529N) would not be predicted to affect DNA binding. His541 of ZF10 is one of the four Zn-coordination ligands. (K) Arg566 of ZF11 is located in the DNA major groove and might be important for sequence-specific interaction, and R566C would lost the ZF11-DNA interaction. (L) Gly403 is located in the linker between ZF5 and ZF6. (M) The substitution of Gly403 with arginine (G403R) could be accommodated and might gain an interaction with DNA. The deletion of residues Thr421-Met422 from the helix of ZF6 destroys the integrity of ZF6.

Phenotypic spectrum in subjects with pathogenic and likely pathogenic CTCF variants

The cardinal (more than 50%) clinical features of the 102 subjects with CRD that we analyzed include: intellectual disability/developmental delay (91%) with speech delay (65%) and motor delay (53%), feeding difficulties/failure to thrive (66%), ocular abnormalities (56%), musculoskeletal anomalies (53%), and behavioral problems (52%) (Table 1). Initial clinical concerns for most of the subjects in the Emory cohort arose during the first six months of life, and included failure to meet developmental milestones, feeding difficulty,or poor weight gain. Detailed clinical information can be found in Supplemental Table S1.

Table 1.

Frequency and percentages of clinical features.

| Systems | Phenotype Ɨ | Emory Cohort | Previously Published | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | n=42 | % | n=60 | % | N=102 | % | |

| Neurology and Developmental | ID/DD | 38 | 91 | 55 | 92 | 93 | 91 |

| Speech delay | 34 | 81 | 32 | 52 | 66 | 65 | |

| Motor delay | 32 | 76 | 22 | 36 | 54 | 53 | |

| Behavioral problems | 20 | 48 | 33 | 55 | 53 | 52 | |

| Hypotonia | 19 | 45 | 27 | 45 | 46 | 45 | |

| Sleeping difficulties | 23 | 55 | 12 | 20 | 35 | 34 | |

| Autism | 13 | 31 | 19 | 32 | 32 | 31 | |

| Seizures | 12 | 29 | 6 | 10 | 18 | 18 | |

| Growth and GI | FTT/feeding difficulties | 29 | 69 | 38 | 63 | 67 | 66 |

| Other GI problems | 15 | 36 | 20 | 33 | 35 | 34 | |

| Low Weight (>2SD) | 14 | 33 | 16 | 27 | 30 | 29 | |

| Short stature | 6 | 14 | 17 | 28 | 23 | 23 | |

| Microcephaly | 7 | 17 | 20 | 33 | 27 | 26 | |

| Physical | Cardiac defect | 6 | 14 | 16 | 27 | 22 | 22 |

| Urogenital anomalies | 12 | 29 | 13 | 22 | 25 | 25 | |

| Musculoskeletal anomalies | 22 | 52 | 32 | 53 | 54 | 53 | |

| Palatal anomalies | 11 | 26 | 15 | 25 | 26 | 25 | |

| Tooth anomalies | 26 | 62 | 14 | 23 | 40 | 39 | |

| Vision | Ocular abnormalities | 24 | 57 | 33 | 55 | 57 | 56 |

| Hearing | Hearing loss | 11 | 26 | 13 | 22 | 24 | 24 |

| Other | Recurrent infections | 7 | 17 | 20 | 33 | 27 | 26 |

| Prenatal | Prenatal findings | 20 | 48 | 16 | 27 | 36 | 35 |

| Premature | 11 | 26 | 12 | 20 | 23 | 23 | |

| Low birth weight | 14 | 33 | 12 | 20 | 26 | 25 | |

Abbreviations: ID=intellectual disability, DD=developmental delay, FTT=failure to thrive

Cardinal features >50% prevalence are in bold

Neurodevelopment and neurological abnormalities

Intellectual disability/developmental delay (DD/ID) was almost universally reported (93 of 102 subjects). In the Emory cohort, key developmental milestones were typically delayed for those old enough to have been assessed. Speech delay was frequently reported (34/42), and severity was variable, ranging from mild to nonverbal. The mean age of saying first word from the available data was 20 months (range 10 months - 5 years old). Motor delay was reported in 32/42; the mean age of sitting without support was 12 months (range 6–24 months) and of independent walking was 18 months (range 12–42 months). One subject was not able to walk independently at 17 years old. Hypotonia, often contributing to motor delay, was reported in 19/42. Balance issues or coordination deficits were found in 10/42 of subjects. There was no history of regression. Most subjects required early intervention therapies and Individualized Education Programs (IEP) in school.

Overall, neurobehavioral phenotypes included autism spectrum disorder and autistic features in 31% (32/102), and ADHD was reported in 16% (16/102) of subjects. Other less frequent behaviors included: aggression, anxiety, destructive behaviors, and difficulty regulating emotions. Eighteen subjects (18%) reported seizures. Of note, two subjects with seizures in the Emory cohort were previously published as having no seizures. There was no consistency in seizure type, with febrile, petit, tonic, and generalized tonic-clonic seizures having all been reported. Neurological imaging (MRI and EEG) reported nonspecific anomalies in some patients, but nothing was found that was generalizable to this population.

Sleep disturbances were reported in 34% (35/102). This was more commonly reported (23/42, 55%) in the Emory cohort. Of these23, 11 reported frequent waking at night, and the others reported difficulty falling asleep. Eight of these subjects needed to take medication to help with sleep, such as melatonin or clonidine.

Gastrointestinal manifestations and growth delay

Feeding difficulties and/or FTT have been reported in 66% (67/102) of all subjects, eight of whom required feeding tubes. Feeding difficulties have been attributed to a variety of reasons, including cleft palate, dysphagia, and hypotonia. Feeding difficulties occurred in the neonatal period and infancy in most cases and resolved as the subjects grew older. Other gastrointestinal manifestations were reported in 34% (35/102) of subjects. The most common was constipation occurring in 17% (17/102) of individuals.

Analysis of growth parameters showed that approximately one-third of subjects (30/102) demonstrated low weight (<−2SD), and about one-fourth demonstrated short stature (23/102) and/or microcephaly (27/102). As can be seen in Table 1, these were comparable to the Emory cohort findings. Of note, two patients reported marfanoid habitus.

Craniofacial Anomalies

Both palatal and dental complications have been reported in this population. Cleft palate was reported in 25% (26/102), and 39% (40/102) reported tooth anomalies. A large proportion of our cohort had dental anomalies 62% (26/42). The most common were impacted or crowded teeth and abnormal decay/cavities. Others included ectopic teeth, missing permanent teeth, wide spacing, midline misalignment, abnormal shape and discoloration.

Hearing and Ocular Anomalies

A similar fraction of cases in the total and Emory cohorts reported hearing problems [24% (24/102) vs 26% (11/42)] and vision anomalies [56% (56/102) vs 57% (24/42)]. In the Emory cohort, eight individuals presented bilateral hearing loss, either sensorineural or conductive, and two presented with unilateral hearing loss. The most common vision anomaly was strabismus, and other less frequently reported problems included hypermetropia, astigmatism, amblyopia, myopia, among others.

Other systemic anomalies

Congenital heart defects were reported in 22% of the CRD population (22/102). The most commonly reported finding was an atrial septal defect. In the Emory cohort the prevalence was lower (14%, 6/42). Of these, two cases had atrial septal defects, one was diagnosed with tetralogy of Fallot, and another with pulmonary valve stenosis and a dilated ascending aorta.

In all, 25% (25/102) of subjects reported urogenital anomalies. Renal anomalies, such as dysplastic kidneys and solitary kidneys, were reported in both males and females. In the Emory cohort, urogenital anomalies were detected in nine males and three females. Among males, the most common anomaly was cryptorchidism; other findings included spermatocele, chordee, and phimosis, among others.

Musculoskeletal anomalies have been reported in 53% (54/102) of subjects. The numbers were very similar in the Emory cohort 52% (22/42). Scoliosis was the most common finding, but kyphosis, tight tendons requiring tenotomies, hip dysplasia, pes valgus, genu valgum, calcaneus valgus and finger abnormalities, such as camptodactyly and clinodactyly, were also reported.

Recurrent Infections

Though not common, recurrent infections have been examined as a feature of CRD subjects in the past. In 102 subjects, 26% reported recurrent infections, whereas in the Emory cohort, only 7 (17%) had recurrent infections, including otitis in five and impetigo in two.

Perinatal history

Prematurity and low birth weight were reported in approximately one-fourth of the total cohort (23%, 23/102 and 25%, 26/102, respectively). Prenatal abnormalities were reported in 35% of all subjects. In the Emory cohort, 26% (11/42) reported prematurity, 33% (14/42) reported low birth weight and 48% (20/42) reported abnormal prenatal findings. The majority of subjects reported intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Exposures, advanced maternal age and advanced paternal age were also examined in our cohort but were seldom reported. Oligohydramnios, single umbilical artery, reduced fetal movement, and polyhydramnios were other reported prenatal findings, but none were generalizable across subjects.

Face2Gene tool

Thirty-six photos from 23 subjects in the Emory cohort and 18 from published cases were used to train the deep learning model using DeepGestalt by Face2Gene tool (Latorre-Pellicer et al., 2020; Mak et al., 2021; Martinez-Monseny et al., 2019). Once the algorithm created the composite photo for an individual with CRD (Figure 4A), it was tested to establish whether it could discriminate between healthy age- and sex-matched individuals and individuals with CRD. Afterwards, 34 photos, 26 from 15 subjects in our cohort and eight photos from published subjects were used to test the application. The algorithm correctly suggested CRD as a possible syndrome for all 34 images with low to medium matching probability.

Figure 4. Facial gestalt of CRD individuals modeled with deep learning algorithms.

(A) Composite facial gestalt photo of CRD trained with 26 subjects. Available in Face2Gene application. (B) Subjects with CRD from the Emory cohort. Some of the facial features seen here include hypertelorism, deeply set eyes, broad nasal bridge, broad nasal tip, low hanging columella, and thin upper lip.

Discussion

Expanding the CRD spectrum

By analyzing the largest cohort (102 subjects) with P/LP variants in CTCF to date, we have been able to better delineate the CRD phenotype. This provides information for genetic counseling, surveillance care and management. Through a collection of the information available to date, physicians can begin to understand the complexities of this highly variable condition. Furthermore, the data provided by this study may aid in classifying VUS in CTCF, and the facial gestalt may facilitate facial recognition by healthcare providers.

While most distinctive features of CRD were comparable between the Emory and published cohorts, a few features were significantly different. For example, sleeping difficulties and tooth anomalies were notably more common in the Emory cohort. It is possible that sleep problems were not specifically asked about, and therefore were not reported by parents or caretakers of the previously published subjects. Similarly, tooth anomalies may not have been analyzed in all previous studies.

More importantly, this compilation allows clarification of some misconceptions about CRD. Individuals with CRD have been previously considered to be smaller than average with short stature and microcephaly. However, our analysis suggests that the most consistently deficient growth parameter was low weight, seen in 29% of all subjects. Neither short stature or microcephaly was characteristic findings of CRD. Caretakers from our cohort report that to their understanding, cardiac and cleft palate anomalies, as well as hearing loss, are characteristic of this population. However, our data do not indicate that these are dominant features of CRD, suggesting that current descriptions of the phenotype of CTCF variants need to be updated. More so, the OMIM definition uses the outdated term “mental retardation” as a descriptor of CRD. It has led to the discouragement and misconception of the intellectual ability level of patients with CRD. It is important to emphasize that there is a broad spectrum of features, including intellectual ability. While some individuals may need more assistence, two subjects from the Emory cohort have been able to attend college with additional help.

Recommendations for surveillance and management of patients with CRD

An overview of recommendations for surveillance and management of this population based on our comprehensive description of CRD was presented in Table 2. We suggest that all these recommendations should be considered at the time of diagnosis and that growth and development should continue to be monitored from that time.

Table 2.

Recommendations for management and surveillance of patients with CRD

| Specialty | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental | Monitor development and provide early intervention (ST, OT, PT) if indicated Evaluation for autism spectrum disorder and other behavioral problems (ADHD, anxiety disorder) |

| Neurology | Refer to neurology if clinical concerns for seizure, brain imaging as indicated |

| Gastrointestinal & Nutrition | Evaluation for feeding and growth carefully at every visit Monitoring and treatment for constipation and/or GERD |

| Ophthalmology | Refer at diagnosis to screen for strabismus and ocular anomalies |

| ENT | Hearing screening at diagnosis Monitor for otitis Refer as needed for evaluation of cleft palate |

| Dental | Early evaluation due to possible delay in dentition, oligodontia, premature decay among others |

| Cardiology | Echocardiogram to rule out cardiac defects at diagnosis |

| Urogenital | Renal ultrasound to rule out renal anomalies at diagnosis |

| Musculoskeletal | Evaluation for anomalies in the extremities, hips and spine as clinical indicated |

| Sleep | Ask about sleep history. Manage sleep disturbance through a combined approach of targeted sleep hygiene and use of medications |

| Genetics | Ongoing evaluation by a clinical geneticist to provide new recommendations and information and connect caretakers and patients with support groups |

Monitoring speech development and providing appropriate therapy promptly was important for subjects with CRD. Of 33 subjects in the Emory cohort with speech delay, most subjects demonstrated good progress under speech therapy. However, a subset of these (8/33) displayed a limited vocabulary of fewer than ten words or absent speech at or after 5 years of age. As expected, some subjects with speech delay and hearing loss made improvement after acquiring hearing aids. In the same way, a few patients anecdotally reported that using augmentative and alternative communication devices improved their communication.

The age of onset for seizures can be variable. For subjects that provided details about their seizures, we found that the earliest onset was 10 weeks of age and the latest onset so far was 16 years of age. The majority of these subjects responded well to antiepileptic medication and did not have recurrent seizures to date. However, one of the subjects has had >15 seizures even after being prescribed numerous medications.

Although autism has not been highlighted as a feature of CRD previously, approximately one-third of subjects has been diagnosed with autistic features or autism spectrum disorder. It is important that clinicians include ASD screening in their evaluation, since this may significantly influence communication and quality of life, and early intervention is beneficial.

Location of CTCF variants and heterogeneity of symptoms

The majority of CTCF pathogenic missense variants (33 out of 35) are located in ZFs, particularly in the DNA-binding region (Figure 2). Many of these affect Cys and His residues that are involved in the coordination of Zn to allow proper folding of each ZF unit and subsequent interaction with the major groove of DNA. Interestingly, these variants are located in all Zn fingers with the exception of ZF8-9. ZF8-9 span the backbone of the DNA duplex, conferring no sequence specificity but adding to overall binding (Zhang et al., 2020). ZF1, ZF10, ZF11, and part of the C-terminal domain of CTCF, are also involved in interactions with RNA, perhaps explaining the presence of pathogenic variants in these regions of the CTCF protein. In addition, the YDF domain, where some variants are found, is involved in interactions with cohesin, explaining the importance of this region for CTCF function. Therefore, there is a good correlation between the location of variants in CTCF causing CRD and known functional aspects of this protein. We did not observe a correlation between the location of the variants and the overall severity of various phenotypes, including the level of intellectual function, presence of congenital anomalies, or poor growth.

Interfamilial variation was observed. Those subjects carrying the same variant, such as several hotspot missense variants, exhibit a broad range of phenotype severity. In addition, 35 of the 76 total variants are either nonsense, canonical splice site, frameshift or large deletion variants with the same expected LOF effect of CTCF, but they are also associated with heterogeneous clinical manifestations. This strongly indicates that the broad phenotypic spectrum was not due to the location of the variant alone, but rather due to either modifying alleles or environmental factors. We also noted several patients carry VUS in other genes (Table 1). At present, we are unable to determine whether VUSs in other genes contribute to the phenotypic variability in CRD. Future studies in subject-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) or tissue specific organoids may further elucidate the underlying mechanism of CTCF variants in CRD.

Our cohort includes one familial case including a son, mother, and grandmother. The son demonstrates dysmorphic features and autism, cryptorchidism and phimosis, valgus flat feet, myopia, and astigmatism. The information from his mother and maternal grandmother was limited: his mother had learning difficulties in school and had a solitary kidney; the grandmother had learning difficulties in school and hip dysplasia. Though they all carry the same variant, c.1114T>C (p.Ser372Pro), their clinical features were vastly different. The residue Ser372 of ZF4 is involved in interactions with DNA backbone phosphate groups. The change from serine to proline might be disruptive for DNA binding (Figure 3). Due to limited information, c.1114T>C is currently classified as a VUS. Functional studies are needed to better understand the impact of this variant on CTCF function. If this variant is reclassified as pathogenic as more data become available, it would highlight intrafamilial variation for CRD and further support the involvement of other factors or variable downstream gene regulation in the pathogenesis and clinical expression of CRD.

Even though the majority of the variants were confirmed as de novo variants (80%), the variants in nine subjects were confirmed to be inherited from one of parents, in two of these, mosaicism was detected. The parents were only tested because of their child’s phenotype, pointing to the importance of parental testing for precise counseling of recurrence risk, even though they appear to be phenotypically normal. In addition, the intrafamilial variation cannot rule out incomplete penetrance in CRD.

Wilms tumor

Wilms tumor (WT) is the most common pediatric renal tumor in the general population, with an .incidence of one in every 10,000 children (Leslie et al., 2022; Reid et al., 2005; Treger et al., 2019). Notably, three out of 107 subjects with CTCF variants developed WT, two of which had variants classified as P/LP and one as a VUS. This prompts us to consider whether germline pathogenic variants in CTCF predispose subjects to develop WT or whether the two entities co-occurred by chance.

Of three subjects with WT, one subject, described by Konrad et al (Konrad et al., 2019), was diagnosed at age four. He carries a de novo pathogenic missense variant c.1117C>G p.(His373Asp) that affects zinc coordination, thus affecting ZF4 stability. He had normal WT1 testing and chromosome 11p15 methylation study. Exome sequencing did not identify other variants of interest In the Emory Cohort, two subjects developed WT; one with a de novo pathogenic variant c.1756del, p.(Glu586Lysfs*45), predicted to be LOF, was diagnosed with stage IV high-risk WT at age five. He also had a maternally inherited LP frameshift variant in BRCA2 c.3879_3880del, p.(Leu1294Tfs*3). WT is not a commonly reported tumor in heterozygous BRCA2 carriers, and thus the effect of the BRCA2 variant on the development of WT in this subject was unclear. Since both CTCF and BRCA2 operate in the same pathway of enhancing homologous recombination-directed repair of double-stranded DNA breaks, a synergistic effect cannot be excluded(Hilmi et al., 2017). The other subject in our cohort was diagnosed with WT at one year old and carries a VUS c.1207G>A, p.(Gly403Arg) in CTCF. The patient had a normal methylation study for the chromosome 11p15 region and normal Array CGH. His genome study did not identify other variants of interest for the predisposition to WT. This variant is located in the linker region between ZF5 and ZF6. However, modeling of the Arg residue coded by the variant suggests that this amino acid substitution results in a possible alternative conformation that may increase DNA binding affinity and lead to gain-of-function.

CTCF somatic variants have been reported in multiple cancer types, such as endometrial cancer (18%), head and neck cancers (3%) and breast cancer (2%) (http://www.tumorportal.org/). To the best of our knowledge, only two somatic missense variants in CTCF, R339W and R448Q, were reported to be associated with WT (Filippova et al., 2002). However, finding somatic variants in a cancer, including WT, does not necessarily mean that germline mutation in the same gene will lead to a cancer predisposition. We suggest that the connection between germline pathogenic variants in CTCF and WT warrants further study to elucidate the risks of WT or other malignancies. To date, no other malignancy has been reported in subjects with CRD. However, considering the young age of most described subjects, additional cancer predispositions cannot be excluded entirely, and long-term follow-up is needed.

Facial gestalt of CRD subjects modeled with deep learning algorithm

The facial characteristics of CRD can be subtle and may not be immediately recognized by clinicians. The Face2Gene digital facial analysis tool can be used to assist in facial recognition and facilitate the diagnostic process (Latorre-Pellicer et al., 2020; Mak et al., 2021; Martinez-Monseny et al., 2019). Our analysis established hypertelorism, deeply set eyes, broad nasal bridge, broad nasal tip, and thin upper lips as the most common features in subjects with CRD (Figure 4B). Though the majority of the subjects were of Northern European ancestry, the tool was able to recognize photos of Asian, Hispanic and Black subjects with CRD. An advantage of Face2Gene is that the facial gestalt built by the machine learning algorithm continuously improves with each CRD photo that is added (Pode-Shakked et al., 2020). It is our hope that inclusion of CRD in this tool will facilitate the recognition of affected individuals However, ultimately, as indicated for any neurodevelopmental disorder by Srivastava et al., 2019, our recommendation for diagnosing CRD is still exome sequencing or large ID gene panel including CTCF at present.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study was the missing clinical details from previous studies. We were unable to ask details about each clinical manifestation for subjects that are not part of the Emory cohort. Even in our own cohort, some subjects did not fully complete the provided questionnaire. Furthermore, because we included previously published data, we did not know whether all patients underwent imaging to detect congenital anomalies and cannot be sure whether the definitions by other authors were the same as ours (for example, whether ‘recurrent infections’ meant more than three a year). Though we now have a better understanding of CRD, we were not able to obtain all the information we sought, limiting the completeness of our analysis.

We believe the percentages of some of the features we described were underestimated, since we used the total population of each cohort to estimate percentages. When clinical data were not provided for an individual, they were included in our calculations as not having the phenotype. However, it is possible that some subjects had not yet developed specific clinical features or that they were not asked about it directly at the time of their evaluation.

A second limitation was the lack of diversity in the photos uploaded to the Face2Gene platform. Though we were able to recruit subjects from all over the world, the majority were from North European descent. Although the tool was able to identify subjects with different ancestries, the lack of diversity in our training set may limit the ability of Face2Gene to recognize CRD in all groups. In addition, though CRD is now a possible suggestion in the Face2Gene application, the application must be trained further to allow it to better distinguish CRD from other conditions..

Conclusions

This study serves three purposes: aiding clinicians in recognition of CRD and guiding management, giving guidance for caretakers when they receive this diagnosis, and providing a starting point for further research. CRD can be difficult to diagnose due to its highly variable presentation and the lack of awareness of this relatively newly described condition. By outlining the variable clinical features of CRD, we provide clinicians with the information needed to add CRD to their differential diagnoses. Clinicians can also use the information as a resource for families, so that parents or caregivers can have a better understanding of what CRD may bring to their child in the future. Though it is hard to predict the exact combination of clinical features that a subject may exhibit, we hope this information gives caretakers a better idea of how to best help their child succeed. Lastly, though we compiled the most comprehensive clinical genotype and phenotype information for CRD so far, there is still a great deal of work to be done. While we have brought clarification to CTCF variants and their locations, there is much that is unknown about the downstream effects of this pathway that could contribute to individuals’ phenotypes. This study is simply the beginning of what we hope to learn about this condition, as further knowledge can help finetune diagnosis, management and surveillance.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1. Questionnaires for CRD

Supplemental Table S1. Clinical features of all analyzed subjects (n=107).

(A) Emory CRD cohort (n=46). (B) Previously subjected subjects (n=61)

Supplemental Table S2. Variants of all analyzed CRD subjects.

(A) Emory cohort. (B) Published cohort. (C) All variants included in this study. (D) Reported variants not included in this study.

Supplemental Figure S1. Schematic flow of clinical data collection from all subjects with CTCF variants.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all the participants and their families who made this study possible. Meeting them and hearing about their journeys has been the most enriching part of this study. We would like to acknowledge other individuals who contributed to making this research possible: Ami Rosen, Dr. Nadia Ali, Dr. Pawel Piwko, Janette diMonda, Dayra Raschid, and Steven Morales. We also thank the many physicians worldwide who contributed to our research process: Dr. Marjolaine Willems, Dr. Tianyun Wang, Dr. Helen Stewart, Dr. Neeti Ghali, Dr. Jonathan Lévy, Dr. Lyse Ruaud, Dr. Ana Cueto, Dr. Andrea Accogli, Dr. Zohta Shad, Dr. Vivian Chang, Dr. Florence Jobic, and many more. We would like to thank Quinn Eastman for editing this manuscript for English language. The work on CTCF graphic modeling was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Awards R35 GM139408 (VGC) and R35 GM134744 (XC) from the National Institutes of Health. H-LW was supported by NIH F32 ES031827. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare there are no conflicts of interest associated with this study and publication.

Ethics Declaration

Any aspect of the work that has involved human subjects in this manuscript has been conducted with the ethical approval of Emory IRB. This approval is acknowledged within the manuscript.

Ethics Attestation

We declare that this manuscript is original, has not been published before, and is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplemental materials.

References

- Bastaki F, Nair P, Mohamed M, Malik EM, Helmi M, Al-Ali MT, & Hamzeh AR (2017). Identification of a novel CTCF mutation responsible for syndromic intellectual disability - a case report. BMC Med Genet, 18(1), 68. 10.1186/s12881-017-0429-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Yuan H, Wu W, Chen S, Yang Q, Wang J, . . . Shen Y (2019). Three additional de novo CTCF mutations in Chinese patients help to define an emerging neurodevelopmental disorder. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 181(2), 218–225. 10.1002/ajmg.c.31698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippova GN, Qi CF, Ulmer JE, Moore JM, Ward MD, Hu YJ, . . . Lobanenkov VV (2002). Tumor-associated zinc finger mutations in the CTCF transcription factor selectively alter tts DNA-binding specificity. Cancer Res, 62(1), 48–52. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11782357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor A, Oti M, Kouwenhoven EN, Hoyer J, Sticht H, Ekici AB, . . . Zweier C (2013). De novo mutations in the genome organizer CTCF cause intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet, 93(1), 124–131. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AS, Hsieh TS, Cattoglio C, Pustova I, Saldana-Meyer R, Reinberg D, . . . Tjian R (2019). Distinct Classes of Chromatin Loops Revealed by Deletion of an RNA-Binding Region in CTCF. Mol Cell, 76(3), 395–411 e313. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Wang D, Horton JR, Zhang X, Corces VG, & Cheng X (2017). Structural Basis for the Versatile and Methylation-Dependent Binding of CTCF to DNA. Mol Cell, 66(5), 711–720 e713. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilmi K, Jangal M, Marques M, Zhao T, Saad A, Zhang C, . . . Witcher M (2017). CTCF facilitates DNA double-strand break repair by enhancing homologous recombination repair. Sci Adv, 3(5), e1601898. 10.1126/sciadv.1601898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraide T, Yamoto K, Masunaga Y, Asahina M, Endoh Y, Ohkubo Y, . . . Saitsu H (2021). Genetic and phenotypic analysis of 101 patients with developmental delay or intellectual disability using whole-exome sequencing. Clin Genet, 100(1), 40–50. 10.1111/cge.13951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori I, Kawamura R, Nakabayashi K, Watanabe H, Higashimoto K, Tomikawa J, . . . Saitoh S (2017). CTCF deletion syndrome: clinical features and epigenetic delineation. Journal of Medical Genetics, 54(12), 836–842. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iossifov I, O’Roak BJ, Sanders SJ, Ronemus M, Krumm N, Levy D, . . . Wigler M (2014). The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature, 515(7526), 216–221. 10.1038/nature13908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad EDH, Nardini N, Caliebe A, Nagel I, Young D, Horvath G, . . . Zweier C (2019). CTCF variants in 39 individuals with a variable neurodevelopmental disorder broaden the mutational and clinical spectrum. Genet Med, 21(12), 2723–2733. 10.1038/s41436-019-0585-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung JT, Kesner B, An JY, Ahn JY, Cifuentes-Rojas C, Colognori D, . . . Lee JT (2015). Locus-specific targeting to the X chromosome revealed by the RNA interactome of CTCF. Molecular Cell, 57(2), 361 375. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latorre-Pellicer A, Ascaso A, Trujillano L, Gil-Salvador M, Arnedo M, Lucia-Campos C, . . . Pie J (2020). Evaluating Face2Gene as a Tool to Identify Cornelia de Lange Syndrome by Facial Phenotypes. Int J Mol Sci, 21(3). 10.3390/ijms21031042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie SW, Sajjad H, & Murphy PB (2022). Wilms Tumor. In StatPearls https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28723033 [PubMed]

- Li Y, Haarhuis JHI, Sedeno Cacciatore A, Oldenkamp R, van Ruiten MS, Willems L, . . . Panne D (2020). The structural basis for cohesin-CTCF-anchored loops. Nature, 578(7795), 472–476. 10.1038/s41586-019-1910-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak BC, Sanchez Russo R, Gambello MJ, Fleischer N, Black ED, Leslie E, . . . Mulle JG (2021). Craniofacial features of 3q29 deletion syndrome: Application of next-generation phenotyping technology. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 185(7), 2094–2101. 10.1002/ajmg.a.62227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Monseny A, Cuadras D, Bolasell M, Muchart J, Arjona C, Borregan M, . . . Consortium, C. D. G. S. (2019). From gestalt to gene: early predictive dysmorphic features of PMM2-CDG. Journal of Medical Genetics, 56(4), 236–245. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Pammi M, Saronwala A, Magoulas P, Ghazi AR, Vetrini F, . . . Lalani SR (2017). Use of Exome Sequencing for Infants in Intensive Care Units: Ascertainment of Severe Single-Gene Disorders and Effect on Medical Management. JAMA Pediatr, 171(12), e173438. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahashi H, Kieffer Kwon KR, Resch W, Vian L, Dose M, Stavreva D, . . . Casellas R (2013). A genome-wide map of CTCF multivalency redefines the CTCF code. Cell Rep, 3(5), 1678–1689. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JE, & Corces VG (2009). CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell, 137(7), 1194 1211. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pode-Shakked B, Finezilber Y, Levi Y, Liber S, Fleischer N, Greenbaum L, & Raas-Rothschild A (2020). Shared facial phenotype of patients with mucolipidosis type IV: A clinical observation reaffirmed by next generation phenotyping. Eur J Med Genet, 63(7), 103927. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2020.103927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard S, Weymann D, Dunne J, Mayanloo F, Buckell J, Buchanan J, . . . Regier DA (2021). Toward the diagnosis of rare childhood genetic diseases: what do parents value most? Eur J Hum Genet, 29(10), 1491–1501. 10.1038/s41431-021-00882-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid S, Renwick A, Seal S, Baskcomb L, Barfoot R, Jayatilake H, . . . Familial Wilms Tumour, C. (2005). Biallelic BRCA2 mutations are associated with multiple malignancies in childhood including familial Wilms tumour. Journal of Medical Genetics, 42(2), 147–151. 10.1136/jmg.2004.022673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retterer K, Juusola J, Cho MT, Vitazka P, Millan F, Gibellini F, . . . Bale S (2016). Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing across clinical indications. Genet Med, 18(7), 696–704. 10.1038/gim.2015.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee HS, & Pugh BF (2011). Comprehensive genome-wide protein-DNA interactions detected at single-nucleotide resolution. Cell, 147(6), 1408–1419. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, . . . Committee, A. L. Q. A. (2015). Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med, 17(5), 405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs ER, Andersen EF, Cherry AM, Kantarci S, Kearney H, Patel A, . . . Martin CL (2020). Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen). Genet Med, 22(2), 245–257. 10.1038/s41436-019-0686-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana-Meyer R, Rodriguez-Hernaez J, Escobar T, Nishana M, Jacome-Lopez K, Nora EP, . . . Reinberg D (2019). RNA Interactions Are Essential for CTCF-Mediated Genome Organization. Mol Cell, 76(3), 412–422 e415. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squeo GM, Augello B, Massa V, Milani D, Colombo EA, Mazza T, . . . Merla G (2020). Customised next-generation sequencing multigene panel to screen a large cohort of individuals with chromatin-related disorder. Journal of Medical Genetics, 57(11), 760–768. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Love-Nichols JA, Dies KA, Ledbetter DH, Martin CL, Chung WK, . . . Group, N. D. D. E. S. R. W. (2019). Meta-analysis and multidisciplinary consensus statement: exome sequencing is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. Genet Med, 21(11), 2413–2421. 10.1038/s41436-019-0554-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treger TD, Chowdhury T, Pritchard-Jones K, & Behjati S (2019). The genetic changes of Wilms tumour. Nat Rev Nephrol, 15(4), 240–251. 10.1038/s41581-019-0112-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Hoekzema K, Vecchio D, Wu H, Sulovari A, Coe BP, . . . Eichler EE (2020). Large-scale targeted sequencing identifies risk genes for neurodevelopmental disorders. Nature communications, 11(1), 4932. 10.1038/s41467-020-18723-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willsey AJ, Fernandez TV, Yu D, King RA, Dietrich A, Xing J, . . . Heiman GA (2017). De Novo Coding Variants Are Strongly Associated with Tourette Disorder. Neuron, 94(3), 486–499 e489. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe SA, Nekludova L, & Pabo CO (2000). DNA recognition by Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct, 29, 183–212. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Velmeshev D, Hashimoto K, Huang Y-H, Hofmann JW, Shi X, . . . Huang EJ (2020). Neurotoxic microglia promote TDP-43 proteinopathy in progranulin deficiency. Nature, 1–5. 10.1038/s41586-020-2709-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Questionnaires for CRD

Supplemental Table S1. Clinical features of all analyzed subjects (n=107).

(A) Emory CRD cohort (n=46). (B) Previously subjected subjects (n=61)

Supplemental Table S2. Variants of all analyzed CRD subjects.

(A) Emory cohort. (B) Published cohort. (C) All variants included in this study. (D) Reported variants not included in this study.

Supplemental Figure S1. Schematic flow of clinical data collection from all subjects with CTCF variants.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplemental materials.