Abstract

Background

Thromboelastography (TEG) is a point-of-care venipuncture test that measures the elasticity and strength of a clot formed from a patient’s blood, providing a more comprehensive analysis of a patient’s coagulation status than conventional measures of coagulation. TEG includes four primary markers: R-time, which measures the time to clot initiation and is a proxy for platelet function; K-value, which measures the time for said clot to reach an amplitude of 20 mm and is a proxy for fibrin cross-linking; maximum amplitude (MA), which measures the clot’s maximum amplitude and is a proxy for platelet aggregation; and LY30, which measures the percentage of clot lysis 30 minutes after reaching the MA and is a proxy for fibrinolysis. Analysis of TEG-derived coagulation profiles may help surgeons identify patient-related and disease-related factors associated with hypercoagulability. TEG-derived coagulation profiles of patients with musculoskeletal oncology conditions have yet to be characterized.

Questions/purposes

(1) What TEG coagulation profile markers are most frequently aberrant in patients with musculoskeletal oncology conditions presenting for surgery? (2) Among patients with musculoskeletal oncology conditions presenting for surgery, what factors are more common in those with TEG-defined hypercoagulability? (3) Do patients with musculoskeletal oncology conditions with preoperative TEG-defined hypercoagulability have a higher postoperative incidence of clinically symptomatic venous thromboembolism (VTE) than those with a normal TEG profile?

Methods

In this retrospective, pilot study, we analyzed preoperatively drawn TEG assays on 52 patients with either primary bone sarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, or metastatic disease to bone who were scheduled to undergo either tumor resection or nail stabilization. Between January 2020 and December 2021, our orthopaedic oncology service treated 410 patients in total. Of these, 13% (53 of 410 patients) had preoperatively drawn TEG assays. TEG assays were collected preincision as part of a division initiative to integrate the assay into a clinical care protocol for patients with primary bone or soft tissue sarcoma or metastatic disease to bone. Unfortunately, failures to adequately communicate this to our anesthesia colleagues on a consistent basis resulted in a low overall rate of assay draws from eligible patients. One patient on therapeutic anticoagulation preoperatively for the treatment of active VTE was excluded, leaving 52 patients eligible for analysis. We did not exclude patients taking prophylactic antiplatelet therapy preoperatively. All patients were followed for a minimum of 6 weeks postoperatively. We analyzed factors (age, sex, tumor location, presence of metastases, and soft tissue versus bony disease) in reference to hypercoagulability, defined as a TEG result indicating supranormal clot formation (for example, reduced R-time, reduced K-value, or increased MA). Patients with clinical concern for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (typically painful swelling of the affected extremity) or pulmonary embolism (typically by dyspnea, tachycardia, and/or chest pain) underwent duplex ultrasonography or chest CT angiography, respectively, to confirm the diagnosis. Categorical variables were analyzed via a Pearson chi-square test and continuous variables were analyzed via t-test, with significance defined at α = 0.05.

Results

Overall, 60% (31 of 52) of patients had an abnormal preoperative TEG result. All abnormal TEG assay results demonstrated markers of hypercoagulability. The most frequent aberration was a reduced K-value (40% [21 of 52] of patients), followed by reduced R-time (35% [18 of 52] of patients) and increased MA (17% [9 of 52] of patients). The mean ± SD TEG markers were R-time: 4.3 ± 1.0, K-value: 1.2 ± 0.4, MA: 66.9 ± 7.7, and LY30: 1.0 ± 1.2. There was no association between hypercoagulability and tumor location or metastatic stage. The mean age of patients with TEG-defined hypercoagulability was higher than those with a normal TEG profile (44 ± 23 years versus 59 ± 17 years, mean difference 15 [95% confidence interval (CI) 4 to 26]; p = 0.01). In addition, female patients were more likely than male patients to demonstrate TEG-defined hypercoagulability (75% [18 of 24] of female patients versus 46% [13 of 28] of male patients, OR 3.5 [95% CI 1 to 11]; p = 0.04) as were those with soft tissue disease (as opposed to bony) (77% [20 of 26] of patients with soft tissue versus 42% [11 of 26] of patients with bony disease, OR 4.6 [95% CI 1 to 15]; p = 0.01). Postoperatively, symptomatic DVT developed in 10% (5 of 52; four proximal DVTs, one distal DVT) of patients, and no patients developed symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Patients with preoperative TEG-defined hypercoagulability were more likely to be diagnosed with symptomatic postoperative DVT than patients with normal TEG profiles (16% [5 of 31] of patients with TEG-defined hypercoagulability versus 0% [0 of 21] of patients with normal TEG profiles; p = 0.05). No patients with normal preoperative TEG profiles had clinically symptomatic VTE.

Conclusion

Patients with musculoskeletal tumors are at high risk of hypercoagulability as determined by TEG. Patients who were older, female, and had soft tissue disease (as opposed to bony) were more likely to demonstrate TEG-defined hypercoagulability in our cohort. The postoperative VTE incidence was higher among patients with preoperative TEG-defined hypercoagulability. The findings in this pilot study warrant further investigation, perhaps through multicenter collaboration that can provide a sufficient cohort to power a robust, multivariable analysis, better characterizing patient and disease risk factors for hypercoagulability. Patients with TEG-defined hypercoagulability may warrant a higher index of suspicion for VTE and careful thought regarding their chemoprophylaxis regimen. Future work may also evaluate the effectiveness of TEG-guided chemoprophylaxis, as results of the assay may inform selection of antiplatelet versus anticoagulant agent.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Thromboelastography (TEG) is a point-of-care venipuncture laboratory assay that measures the elasticity and strength of a clot formed from a patient’s blood. It provides a more comprehensive analysis of a patient’s coagulation status than conventional measures of coagulation, such as the international normalized ratio. TEG includes four primary markers: R-time, which measures the time to clot initiation and is a proxy for platelet function; K-value, which measures the time for said clot to reach an amplitude of 20 mm and is a proxy for fibrin cross-linking; maximum amplitude (MA), which measures the clot’s maximum amplitude and is a proxy for platelet aggregation; and LY30, which measures the percentage of clot lysis 30 minutes after reaching the MA and is a proxy for fibrinolysis [7]. Previous work has suggested that abnormal TEG results are more likely to be observed in patients with trauma and nonmusculoskeletal oncology conditions who later develop thromboembolic complications [2, 12, 23, 25].

Although venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a well-recognized problem in musculoskeletal oncology patients, consensus must be reached on which patients are at the highest risk of VTE [4, 9, 11, 15, 16, 18, 26]. If TEG-defined hypercoagulability can reasonably serve as a proxy measure for predisposition to VTE—which can be rare and thus preclude robust analyses among patients with musculoskeletal oncology conditions—and we can characterize differences in patients with and without TEG-defined hypercoagulability, we can make a small step toward better identifying those patients at risk for perioperative VTE. In addition, by characterizing the mechanisms of hypercoagulability among these patients—for example, distinguishing hypercoagulability driven by platelet hyperfunction versus hypercoagulability driven by enzymatic hyperactivity catalyzing fibrin crosslinking—information derived from TEG may inform future selection of chemoprophylaxis. This preliminary, pilot study was thus undertaken to take a step toward better understanding and characterizing hypercoagulability in patients with musculoskeletal oncology conditions.

We therefore set out to answer: (1) What TEG coagulation profile markers are most frequently aberrant in patients with musculoskeletal oncology conditions presenting for surgery? (2) Among patients with musculoskeletal oncology conditions presenting for surgery, what factors are more common in those with TEG-defined hypercoagulability? (3) Do patients with musculoskeletal oncology conditions with preoperative TEG-defined hypercoagulability have a higher postoperative incidence of clinically symptomatic VTE than those with a normal TEG profile?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a retrospective, pilot study conducted at a single, large, urban academic referral center.

Patients

Between January 2020 and December 2021, our orthopaedic oncology service operated on 410 patients with primary bone sarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, or metastatic disease to bone who were scheduled to undergo either tumor resection or nail stabilization. Of these, 13% (53 of 410) of patients had preoperatively drawn TEG assays. TEG assays were collected preincision as part of a division initiative to integrate the assay into a clinical care protocol for patients with primary bone or soft tissue sarcoma or metastatic disease to bone. Unfortunately, failures to adequately communicate this to our anesthesia colleagues on a consistent basis resulted in a low overall rate of assay draws from eligible patients. One patient on therapeutic anticoagulation preoperatively for the treatment of active VTE was excluded, leaving 52 patients eligible for analysis. We did not exclude patients who were taking antiplatelet therapy preoperatively, for example, those taking aspirin for coronary artery disease prevention. Although all patients were clinically examined preoperatively, we did not screen all patients with venous duplex studies preoperatively. All patients were followed for a minimum of 6 weeks postoperatively.

Baseline Data

We collected preoperative TEG assays on 52 patients meeting our criteria (Table 1). Forty-six percent (24 of 52) of patients were female. The mean age at the time of surgery was 53 ± 21 years. Thirty-five percent (18 of 52) of patients had metastatic disease. Fifty-percent (26 of 52) of patients had soft tissue sarcoma, 27% (14 of 52) had primary bone sarcoma, and 23% (12 of 52) had metastatic disease to bone. In terms of tumor location, 46% (24 of 52) of patients had axial disease, 38% (20 of 52) had lower extremity disease, and 15% (8 of 52) had upper extremity disease.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included patients

| Sex | Age in years | Pathologic finding | Presence of metastases | Location | Procedure |

| Male | 69 | Lung adenocarcinoma | Yes | Thigh | Nail stabilization |

| Male | 79 | Chondrosarcoma | Yes | Arm | Wide resection |

| Male | 65 | Parotid carcinoma | Yes | Pelvis | Intralesional resection |

| Male | 59 | Chordoma | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Female | 68 | Myxofibrosarcoma | Yes | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Female | 28 | Myxofibrosarcoma | No | Forearm | Wide resection |

| Male | 16 | Ewing sarcoma | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 55 | Osteosarcoma | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 86 | Epithelioid angiosarcoma | No | Pelvis | Intralesional resection |

| Female | 68 | Fibrosarcoma | No | Trapezius | Wide resection |

| Male | 75 | Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma | No | Chest | Wide resection |

| Male | 71 | Lung adenocarcinoma | Yes | Thigh | Nail stabilization |

| Male | 39 | Synovial sarcoma | Yes | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Female | 55 | Chondroblastoma | No | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Male | 68 | Osteosarcoma | Yes | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 72 | Poorly differentiated carcinoma | Yes | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 59 | Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma | Yes | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 70 | Spindle cell sarcoma | Yes | Chest | Wide resection |

| Male | 17 | Ewing sarcoma | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Female | 38 | Chondrosarcoma | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Female | 18 | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | Yes | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 49 | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 81 | Atypical lipomatous tumor | No | Thigh | Marginal resection |

| Male | 29 | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | No | Arm | Wide resection |

| Female | 58 | Lung adenocarcinoma | Yes | Thigh | Nail stabilization |

| Female | 59 | Multiple myeloma | No | Arm | Wide resection |

| Male | 14 | Ewing sarcoma | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 54 | Atypical lipomatous tumor | No | Leg | Marginal resection |

| Male | 41 | Osteosarcoma | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 39 | Osteosarcoma | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 71 | Chondrosarcoma | No | Leg | Wide resection |

| Female | 28 | Osteosarcoma | No | Leg | Wide resection |

| Male | 27 | Osteosarcoma | Yes | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 76 | Lung adenocarcinoma | Yes | Leg | Wide resection |

| Male | 60 | Myxoid liposarcoma | No | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 69 | Myxofibrosarcoma | Yes | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Female | 57 | Atypical lipomatous tumor | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 44 | Melanoma | No | Back | Wide resection |

| Female | 77 | Atypical lipomatous tumor | No | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 41 | Dedifferentiated liposarcoma | No | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 19 | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | No | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 41 | Dedifferentiated liposarcoma | No | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 77 | Atypical lipomatous tumor | No | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Male | 49 | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Female | 61 | Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma | No | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 45 | Squamous cell carcinoma | Yes | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 16 | Osteosarcoma | No | Arm | Wide resection |

| Male | 68 | Chondrosarcoma | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Male | 17 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | Yes | Arm | Wide resection |

| Female | 68 | Leiomyosarcoma | No | Thigh | Wide resection |

| Female | 72 | Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor | No | Pelvis | Wide resection |

| Female | 67 | Osteosarcoma | Yes | Chest | Wide resection |

Clinical Care

Postoperatively, all patients received deep vein thrombosis (DVT) chemoprophylaxis, namely weight-based subcutaneous enoxaparin, except for those with impaired renal function, who received subcutaneous heparin instead. Chemoprophylaxis was initiated on the first postoperative day and continued for a total duration of 4 weeks. All patients received mechanical prophylaxis by sequential compression device while an inpatient, and they were mobilized by our physical therapy team as their clinical status permitted. Patients with clinical concern for DVT (typically painful swelling of the affected extremity) or pulmonary embolism (typically by dyspnea, tachycardia, and/or chest pain) underwent duplex ultrasonography or chest CT angiography, respectively, to confirm the diagnosis. No patients underwent operative intervention for bleeding complications in association with prophylactic anticoagulation. One of our patients with DVT was taken back to the operating room because of a large hematoma after initiation of therapeutic anticoagulation dosing.

Study Evaluations

TEG assays were drawn by venipuncture in the operating room before incision, after the anesthesia induction. Analysis was performed with the commercially available Thrombelastograph Analyzer 5000 (Haemoscope Corp), per manufacturer’s instructions and as described in previously published literature [23].

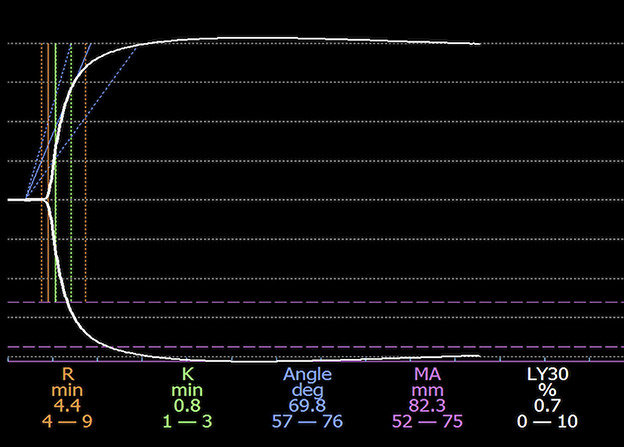

We defined hypercoagulability as a TEG result (Fig. 1) indicating supranormal clot formation (reduced R-time, reduced K-value, or increased MA), referencing the normal ranges set by our hospital laboratory: R-time, 4.0 to 9.0; K-value, 1.0 to 3.0; MA, 52.0 to 75.0; LY30, 0% to 10%. We analyzed patient-related and disease-related factors for association with hypercoagulability, including age, sex, tumor location, bony versus soft tissue disease, and presence of metastases. As noted, following the protocols of our usual clinical practice, patients with clinical concern for DVT (typically painful swelling of the affected extremity) or pulmonary embolism (typically by dyspnea, tachycardia, and/or chest pain) underwent duplex ultrasonography or chest CT angiography, respectively, to confirm the diagnosis. Due to resource constraints, we did not obtain duplex ultrasonography in every patient but instead we relied on clinical assessment—through consistent review of systems, monitoring of vital signs, and twice daily physical examinations by a physician while patients were hospitalized, and again at 1-, 3-, and 6-week postoperative clinical visits—to prompt confirmatory testing for either DVT or PE in clinically symptomatic patients.

Fig. 1.

This figure shows TEG tracing in one of our patients. The x-axis demonstrates time, and the y-axis demonstrates clot size (each line marks 20 mm). The dashed orange, green, and purple lines demarcate the normal range of R-time, K-value, and MA, respectively. The solid orange, green, and purple lines demonstrate the R-time, K-value, and MA measured in our patient. Relative to normal ranges, the K-value was decreased and the MA was increased in this patient, indicating hypercoagulability. Symptomatic VTE developed postoperatively in this patient.

Primary and Secondary Study Outcomes

Our primary study goal was to characterize the frequency and patterns of TEG-defined hypercoagulability. Our secondary goals were to characterize the differences between patients with and without TEG-defined hypercoagulability and determine whether postoperative VTE diagnosis was higher in patients with TEG-defined hypercoagulability than in patients with normal TEG profiles.

Ethical Approval

We obtained ethical review board approval to perform this study.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed via Pearson chi-squared tests. Continuous variables were analyzed via a t-test. Data analysis was conducted in SPSS version 27.0 (IBM), with significance defined as α = 0.05.

Results

Common Abnormalities in TEG Coagulation Profiles

Of the patients analyzed, 60% (31 of 52) of patients had an abnormal preoperative TEG result. All 31 patients demonstrated TEG markers of hypercoagulability. The most frequent aberration was a reduced K-value (40% [21 of 52] of patients), followed by reduced R-time (35% [18 of 52] of patients) and increased MA (17% [9 of 52] of patients). Across all patients, mean R-time was 4.3 ± 1.0, mean K-value was 1.2 ± 0.4, mean MA was 66.9 ± 7.7, and mean LY30 was 1.0 ± 1.2.

What Factors Are Associated With TEG-defined Hypercoagulability?

There was no association between hypercoagulability and tumor location or presence of metastases (Table 2). The mean age was of patients with TEG-defined hypercoagulability was higher than those with a normal TEG profile (44 ± 23 years versus 59 ± 17 years, mean difference 15 years [95% confidence interval (CI) 4 to 26]; p = 0.01). In addition, female patients were more likely than male patients to demonstrate TEG-defined hypercoagulability (75% [18 of 24] of female patients versus 46% [13 of 28] of male patients, OR 3.5 [95% CI 1 to 11]; p = 0.04) as were those with soft tissue disease (as opposed to bony) (77% [20 of 26] of patients with soft tissue versus 42% [11 of 26] of patients with bony disease, OR 4.6 [95% CI 1 to 15]; p = 0.01).

Table 2.

Results of univariate factor analysis (n = 52 patients)

| Variable | Normal TEG (n = 21) | Hypercoagulable TEG (n = 31) | p value |

| Age in years | 44 ± 23 | 59 ± 17 | 0.01 |

| Women | 25% (6 of 24) | 75% (18 of 24) | 0.04 |

| Location | |||

| Upper extremity | 25% (2 of 8) | 75% (6 of 8) | 0.4 |

| Lower extremity | 35% (7 of 20) | 65% (13 of 20) | |

| Axial | 50% (12 of 24) | 50% (12 of 24) | |

| Metastases present | 39% (7 of 18) | 61% (11 of 18) | 0.9 |

| Disease type | |||

| Soft tissue disease | 23% (6 of 26) | 77% (20 of 26) | 0.01 |

| Bony disease | 58% (15 of 26) | 42% (11 of 26) |

Data presented as mean ± SD or % (n).

TEG-defined Hypercoagulability and Clinically Symptomatic VTE

Postoperatively, 10% (5 of 52) of patients experienced clinically symptomatic DVT confirmed by duplex ultrasonography, all of whom had preoperative TEG-defined hypercoagulability. Of our five patients with DVTs, four had proximal DVTs (two femoropopliteal, one axillary, one internal jugular) and one had distal DVT (greater saphenous). No patients had clinically symptomatic pulmonary embolism postoperatively. Patients with TEG-defined hypercoagulability were more likely to be diagnosed with symptomatic DVT postoperatively than patients with normal TEG profiles (16% [5 of 31] of patients with TEG-defined hypercoagulability versus 0% (0 of 21) of patients with normal TEG profiles; p = 0.05). No patients with normal preoperative TEG markers had clinically symptomatic VTE.

Discussion

Patients with cancer have long been designated as a population at high risk for hypercoagulability of malignancy [3, 4, 9, 11, 15, 16, 18, 26]. Previous work has suggested the association of TEG-defined hypercoagulability with thromboembolic complications in patients with trauma and nonmusculoskeletal oncology conditions and in identifying risk factors for hypercoagulability in these populations [2, 12, 23, 25]. However, TEG has not been studied in patients with primary bone and soft tissue sarcoma or metastatic disease to bone. We performed this pilot study to characterize TEG-defined hypercoagulability and identify patient- and disease-related factors associated with TEG-defined hypercoagulability in patients with musculoskeletal tumors. Most patients in this small series with primary bone and soft tissue sarcoma and metastatic bone disease demonstrated TEG-defined hypercoagulability. Older patients, female patients, and patients with soft tissue (rather than bone) lesions were more likely to have TEG-defined hypercoagulability. Postoperatively, symptomatic DVT was diagnosed in more patients with preoperative TEG-defined hypercoagulability than those with normal TEG profiles.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Most importantly, we did not assess all included patients pre- and postoperatively with venous duplex studies, and thus we likely underdiagnosed DVT in our cohort. However, our cohort’s DVT incidence fell within the range of DVT incidence of patients with musculoskeletal tumors in studies that screened every patient with Duplex ultrasonography (4.6% to 22.3% [11]), suggesting that the degree of underdiagnosis may not be so significant as to undermine our results. Furthermore, we have no reason to believe that patients with normal TEG assays would have any greater incidence of subclinical DVT than those with TEG-defined hypercoagulability. This study was not blinded, and consequently a team member aware of a patient with TEG-defined hypercoagulability may have been more likely to suspect and order a confirmatory study for VTE. However, most postoperative patient care (including consistent review of systems, monitoring of vital signs, and twice daily physical examinations while patients were hospitalized) was executed by physicians not directly affiliated with this study, whom we believe were fulfilling their clinical duties regardless of TEG status. We did not obtain preoperative TEG assays in all patients treated by our orthopaedic oncology service during the study period, and bias may have affected which of those were selected. TEG assays were collected preincision as part of a division initiative to integrate the assay into our clinical care protocol for patients with primary bone or soft tissue sarcoma or metastatic disease to bone. Ideally, we would have collected the assay on all 410 patients treated in this timeframe. Unfortunately, failure to adequately communicate this to our anesthesia colleagues on a consistent basis resulted in a low overall rate (13%) of assay draws relative to the base of eligible patients. However, there was not an alternative reason—for example, clinical suspicion of hypercoagulability—that prompted these particular patients to be selected, and thus we believe these included patients should generally be representative of our eligible patient population as a whole. The surveillance period for our patients was only 6 weeks. Previous work has demonstrated median time to DVT or pulmonary embolism after major hip and knee surgery is within 3 to 4 weeks, suggesting that late VTE presentation would not substantially undermine our main findings [1]. In addition, our factor analysis was relatively limited in scope, and a number of potentially relevant variables were not included, such as disease load, functional status, presence or size of soft tissue mass associated with bony lesions, adjuvant chemoradiation, operative time, and medical comorbidities. Our study’s small sample size precluded a robust regression analysis of risk factors and may have underpowered certain univariate analyses. In addition, nearly all TEG assays were drawn during the coronavirus-19 pandemic. Multiple studies have demonstrated increased thromboembolic complications and TEG-defined hypercoagulability in patients with COVID-19 [8, 21, 24]. All our study patients treated during the pandemic were screened for SARS-CoV2 by nucleic acid amplification testing from nasopharyngeal specimens and had negative test results preoperatively, and none developed clinically symptomatic COVID-19 postoperatively within our surveillance period, suggesting that this should not significantly confound our results.

Common Abnormalities in TEG Coagulation Profiles

Although the mean values of R-time, K-value, MA, and LY30 for our study population were within their normal ranges, R-time and K-value were at the lower range of normal. These were the two most frequently aberrant TEG markers in our cohort, occurring in 35% (18 of 52) and 40% (21 of 52), respectively, of all patients included. Reduced R-time indicates more rapid initiation of clot formation, indicating platelet hyperfunction; a reduced K-value indicates more rapid clot growth, driven by overactive fibrinogen crosslinking [7]. TEG-defined hypercoagulability in patients with other cancers have also been characterized by reduced R-time and K-value [25]. In contrast, TEG-defined hypercoagulability in patients with COVID-19 or after trauma was most often characterized by increased MA [2, 8]. This distinction may reflect underlying mechanistic differences that may be of value to study. Future study of chemoprophylaxis informed by specific TEG abnormality—for example, prescribing an antiplatelet agent such as aspirin for patients with reduced R-time versus a heparin-family agent for patients with reduced K-value—may be worth investigating.

What Factors Are Associated With TEG-defined Hypercoagulability?

Older patients and females were more likely to demonstrate TEG-derived hypercoagulability in our cohort. These findings corroborate the findings of earlier studies. In a regression analysis of a large cohort of patients hospitalized for cancer, age 65 years or older and being female were associated with the occurrence of VTE [10]. Another study of healthy people similarly demonstrated TEG-defined hypercoagulability among females, which persisted after controlling for oral contraceptive use, and among older patients [19]. This suggests an underlying predisposition to pathologic hypercoagulability in these groups that may warrant a higher index of suspicion for VTE and careful thought to the chemoprophylaxis regimen. Interestingly, patients with soft tissue disease (as opposed to bony) were also more likely to demonstrate TEG-defined hypercoagulability. Prior evidence has established that there is an increased VTE prevalence among patients with soft tissue sarcoma compared with age-matched patients without cancer [22]. However, other studies have not found a difference in VTE rates between patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma [4, 15]. A difference in TEG-defined hypercoagulability may reflect underlying differences in the production of tissue factor or other inflammatory cytokines by the tumor, or it may reflect the collateral effects of adjuvant therapies such as radiation and immunotherapy that are typically used to a greater extent in soft tissue disease [6, 17, 20]. However, soft tissue sarcomas represent a heterogenous group, and detecting differences between specific pathologic findings will require a larger cohort. Metastatic disease and tumor location were not associated with TEG-defined hypocoagulability in our study. Patients with these risk factors for hypercoagulability may warrant a higher degree of VTE suspicion and more careful thought about chemoprophylaxis. Future studies may evaluate additional risk factors, such as those listed in our limitations, and, if sufficiently powered, allow for a regression factor analysis.

TEG-defined Hypercoagulability and Clinically Symptomatic VTE

Development of clinically symptomatic DVT was more common among patients with preoperative TEG-defined hypercoagulability. This resonates with earlier work in trauma and nonmusculoskeletal oncology [2, 12, 23]. A total of 10% (5 of 52) of our patients were diagnosed with clinically symptomatic DVT, which falls within the range reported by previous authors [4, 9, 11, 15, 16, 18, 26]. A recent systematic review reported that patients with musculoskeletal tumors studied prospectively demonstrated a DVT incidence of 4.6% (4 of 87 patients) to 22.3% (21 of 94 patients) when every included patient was screened before hospital discharge [11]. Although the fact that all patients in this study with symptomatic VTE had DVTs (no patients had symptomatic PE in this study) may reflect the standard use of chemoprophylaxis in our cohort or our study’s small sample size, we acknowledge the gross underdiagnosis of VTE that may have occurred in that only those patients who were clinically symptomatic had confirmatory imaging performed.

Future Directions

There is ample opportunity for a deeper study of TEG in musculoskeletal oncology patients. Factors associated with hypercoagulability, such as plasma D-dimer level, have demonstrated association with inferior cancer outcomes, independent of VTE; exploring TEG in this respect may be an interesting area for further investigation [5, 14]. The interplay of platelets and tumor cells has been implicated as a driver of hematogenous metastasis, and antiplatelet therapy may reduce metastatic progression [13]. Coupling this with the frequency of platelet-driven hypercoagulability in our cohort (indicated by the high prevalence of shortened R-time), incorporation of antiplatelet therapy such as aspirin in the treatment of musculoskeletal oncology patients should be explored. Finally, using TEG intraoperatively to guide resuscitation in patients with large-volume blood loss is another area worth investigating in the musculoskeletal oncology population. A multi-institutional collaboration would permit the use of a larger cohort, powering more robust investigations of these and other TEG-related questions.

Conclusion

Overall, most patients with primary bone or soft tissue sarcoma and metastatic disease to bone were shown in our pilot study to have a hypercoagulable TEG profile. Older patients, female patients, and patients with soft tissue (rather than bone) lesions were more likely to have TEG-defined hypercoagulability, but larger studies will be necessary to confirm our findings. Postoperatively, symptomatic DVT was diagnosed among more patients with preoperative TEG-defined hypercoagulability than those with normal TEG profiles. These findings warrant further investigation, perhaps through multicenter collaboration that can provide a sufficient cohort to power a robust, multivariable analysis that better characterizes patient and disease risk factors for hypercoagulability. Patients with TEG-defined hypercoagulability may warrant a higher index of suspicion for VTE and careful thought regarding their chemoprophylaxis regimen. Future work may also evaluate the effectiveness of TEG-guided chemoprophylaxis, as results of the assay could inform selection of antiplatelet versus heparin-family agent.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that there are no funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article related to the author or any immediate family members.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA (number IRB00311776).

Contributor Information

Hulai B. Jalloh, Email: hjalloh2@jhmi.edu.

Adam S. Levin, Email: alevin25@jhmi.edu.

Carol D. Morris, Email: cmorri61@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Bjørnarå BT, Gudmundsen TE, Dahl OE. Frequency and timing of clinical venous thromboembolism after major joint surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:386-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown W, Lunati M, Maceroli M, et al. Ability of thromboelastography to detect hypercoagulability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2020;34:278-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caine GJ, Stonelake PS, Lip GYH, Kehoe ST. The hypercoagulable state of malignancy: pathogenesis and current debate. Neoplasia. 2002;4:465-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damron TA, Wardak Z, Glodny B, Grant W. Risk of venous thromboembolism in bone and soft-tissue sarcoma patients undergoing surgical intervention: a report from prior to the initiation of SCIP measures. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:643-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diao D, Cheng Y, Song Y, Zhang H, Zhou Z, Dang C. D-dimer is an essential accompaniment of circulating tumor cells in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guy J-B, Bertoletti L, Magné N, et al. Venous thromboembolism in radiation therapy cancer patients: findings from the RIETE registry. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;113:83-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagedorn JC, Bardes JM, Paris CL, Lindsey RW. Thromboelastography for the orthopaedic surgeon. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27:503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmann J, Ergang A, Mason D, Dias JD. The role of TEG analysis in patients with COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: a systematic review. Diagnostics. 2021;11:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser CL, Freehan MK, Driscoll DA, Schwab JH, Bernstein KDA, Lozano-Calderon SA. Predictors of venous thromboembolism in patients with primary sarcoma of bone. Surg Oncol. 2017;26:506-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, Kuderer NM, Lyman GH. Frequency, risk factors, and trends for venous thromboembolism among hospitalized cancer patients. Cancer. 2007;110:2339-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lex JR, Evans S, Cool P, et al. Venous thromboembolism in orthopaedic oncology. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B:1743-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Wang N, Chen Y, Lu R, Ye X. Thrombelastography coagulation index may be a predictor of venous thromboembolism in gynecological oncology patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43:202-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucotti S, Muschel RJ. Platelets and metastasis: new implications of an old interplay. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma M, Cao R, Wang W, et al. The D-dimer level predicts the prognosis in patients with lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;16:243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell SY, Lingard EA, Kesteven P, McCaskie AW, Gerrand CH. Venous thromboembolism in patients with primary bone or soft-tissue sarcomas. JBJS. 2007;89:2433-2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morii T, Mochizuki K, Tajima T, Aoyagi T, Satomi K. Venous thromboembolism in the management of patients with musculoskeletal tumor. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15:810-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukai M, Oka T. Mechanism and management of cancer-associated thrombosis. J Cardiol. 2018;72:89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel AR, Crist MK, Nemitz J, Mayerson JL. Aspirin and compression devices versus low-molecular-weight heparin and PCD for VTE prophylaxis in orthopedic oncology patients. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:276-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roeloffzen WWH, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Mulder AB, Veeger NJGM, Bosman L, de Wolf JTM. In normal controls, both age and gender affect coagulability as measured by thrombelastography. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:987-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roopkumar J, Swaidani S, Kim AS, et al. Increased incidence of venous thromboembolism with cancer immunotherapy. Med (N Y). 2021;2:423-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salem N, Atallah B, El Nekidy WS, Sadik ZG, Park WM, Mallat J. Thromboelastography findings in critically ill COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021;51:961-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shantakumar S, Connelly-Frost A, Kobayashi MG, Allis R, Li L. Older soft tissue sarcoma patients experience increased rates of venous thromboembolic events: a retrospective cohort study of SEER-Medicare data. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2015;5:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toukh M, Siemens DR, Black A, et al. Thromboelastography identifies hypercoagulablilty and predicts thromboembolic complications in patients with prostate cancer. Thromb Res. 2014;133:88-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsantes AE, Tsantes AG, Kokoris SI, et al. COVID-19 infection-related coagulopathy and viscoelastic methods: a paradigm for their clinical utility in critical illness. Diagnostics. 2020;10:817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh M, Kwaan H, McCauley R, et al. Viscoelastic testing in oncology patients (including for the diagnosis of fibrinolysis): review of existing evidence, technology comparison, and clinical utility. Transfusion. 2020;60(suppl 6):S86-S100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi T, Matsumine A, Niimi R, et al. Deep-vein thrombosis after resection of musculoskeletal tumours of the lower limb. Bone Joint J. 2013;95:1280-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]