Abstract

BACKGROUND

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been found to be responsible for the recent global pandemic known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). SARS-CoV-2 infections not only result in significant respiratory symptoms but also cause several extrapulmonary manifestations, such as thrombotic complications, myocardial dysfunction and arrhythmia, thyroid dysfunction, acute kidney injury, gastrointestinal symptoms, neurological symptoms, ocular symptoms, and dermatological complications. We present the first documented case of thyroid storm in a pregnant woman precipitated by SARS-CoV-2.

CASE SUMMARY

A 42-year-old multiparous woman at 35 + 2 wk of gestation visited the emergency room (ER) with altered mentation, seizures, tachycardia, and high fever. The patient showed no remarkable events in the prenatal examination, and the nasopharyngeal COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was positive two days before the ER visit. The results of laboratory tests, such as liver function test, serum electrolytes, blood glucose, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine, were all within the normal ranges. However, the thyroid function test showed hyperthyroidism, and the nasopharyngeal COVID-19 PCR test was positive, as expected. No specific findings were observed on the brain computed tomography, and there were no signs of lateralization on neurological examination. Fetal heartbeat and movement were good, and there were no significant uterine contractions. The initial impression was atypical eclampsia. However, the patient's condition worsened, and a cesarean section was performed under general anesthesia; a healthy boy was delivered, and 12 h after delivery, the patient's seizures disappeared and consciousness was restored. The patient was referred to an endocrinologist for hyperthyroidism, and a thyroid storm with Graves' disease was diagnosed. Here, SARS-CoV-2 was believed to be the trigger for the thyroid storm, considering that the patient tested positive for COVID-19 two days before the seizures.

CONCLUSION

In pregnant women presenting with seizures or changes in consciousness, the possibility of a thyroid storm should be considered. There are various causes for a thyroid storm, but given the recent pandemic, it is necessary to bear in mind that the thyroid storm may be precipitated by COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Hyperthyroidism, Pregnancy, Thyroid storm, Thyrotoxicosis, Case report

Core Tip: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a pandemic disease. For pregnant women presenting with emergency symptoms, clinicians should consider the possibility of a thyroid storm caused by COVID-19.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy is about 0.2% and is mostly subclinical[1]. A thyroid storm (TS) is a rare but serious complication in patients with hyperthyroidism (1%-2% of cases of hyperthyroidism)[2-4]. The symptoms of a TS are similar to those of hyperthyroidism, but they are more sudden, severe, and extreme. We report a case in which a pregnant woman who visited the emergency room (ER) with altered mentation, seizures, and high fever was initially misdiagnosed as eclampsia and eventually diagnosed to have a TS because of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 42-year-old multiparous woman with a gestational age of 35 + 2 wk presented to the ER with altered mentation, seizures, and a high fever of 38.3 °C.

History of present illness

The patient tested positive for the nasopharyngeal COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test with symptoms of throat pain two days before her ER visit. Upon arrival at the ER, endotracheal intubation was performed immediately, and an emergency call was made to the obstetrics and gynecology department. According to the widely accepted severity scale of COVID-19 (Table 1), illness of severity was critical requiring mechanical ventilation[5].

Table 1.

Illness severity for coronavirus disease 2019

|

Severity

|

Signs and symptoms

|

| Asymptomatic/presymptomatic | Positive for SARS-CoV-2 using a test but no symptoms that are consistent with COVID-19 |

| Mild illness | Signs and symptoms of COVID-19 but no shortness of breath, dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging |

| Moderate illness | Signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease or abnormal imaging and SpO2 ≥ 94% on room air at sea level |

| Severe illness | SpO2 ≤ 94% on room air at sea level, PaO2/FiO2 < 300 mmHg, respiratory frequency > 30 breaths/min, or lung infiltrates > 50% |

| Critical illness | Respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction |

From the American college of emergency physicians field guide. COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2.

History of past illness

The patient had previously delivered a healthy baby by cesarean section two years ago. According to the statements of the guardians obtained in the ER, the patient did not have any specific underlying diseases, and there were no remarkable events during the prenatal examinations in the current pregnancy.

Personal and family history

The patient had no history of drug abuse, smoking, or drinking. Further, there was no family history of genetic, autoimmune, or thyroid diseases.

Physical examination

The seizure was a generalized tonic-clonic type, and the patient presented with drooling and continuous upper eyeball deviation. The pupillary reflex was prompt, symmetric, and consensual. Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 121/71 mmHg and heart rate of 115 beats per minute.

Laboratory examinations

The nasopharyngeal COVID-19 test performed in the ER was positive. Laboratory results at the emergency unit showed increased C-reactive protein of 15.7 mg/L [reference range (RR): 0-5 mg/L], erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 37 mm/h (RR: 0-20 mm/h), and D-dimer of 2.7 µg/mL (RR: 0.0-0.5 µg/mL). There was no proteinuria or other abnormality in the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, which could be considered a sign of eclampsia. The results of the laboratory tests, such as liver function test, serum electrolytes, blood glucose, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine, were all normal. The thyroid function test showed a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level of < 0.01 mIU/L [3rd trimester-specific reference range (3TRR): 0.38-4.04 mIU/L[6]], free T4 level of 1.95 ng/dL (3TRR: 0.5-0.8 ng/dL[6]), and total T3 level of 183.9 ng/dL (3TRR: 123-162 ng/dL[6]), which reflect overt hyperthyroidism. According to the Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale (BWPS)[2], the score was 65, which was highly suggestive of a TS.

Imaging examinations

Brain computed tomography revealed no acute intracranial hemorrhage, focal parenchymal lesions, or visible causes of seizure. In addition, there were no focal neurological signs, and the neurologist underestimated the likelihood of seizures owing to the central nervous system lesions.

Further diagnostic work-up

No noteworthy findings were obtained from the chest X-ray and electrocardiogram. On ultrasonography, the fetal growth was noted to be appropriate for the gestational age, and the fetal heartbeat and movements were normal. No significant uterine contractions were observed in the tocomonitor.

Initial diagnosis

The initial impression was eclampsia because of the seizures and altered consciousness. However, there were several points that were not suitable for a diagnosis of eclampsia. For example, the maternal blood pressure was normal, and there was no proteinuria, fetal growth restriction, thrombocytopenia, kidney failure, or hepatic dysfunction. Thus, we arrived at a diagnosis of atypical eclampsia.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis was status epilepticus (SE) due to a TS from a preexisting Graves’ disease. Given that the patient tested positive for COVID-19 two days before admission to the ER, the trigger for the TS is believed to be SARS-CoV-2.

TREATMENT

For the primary treatment of eclampsia, labetalol, magnesium sulfate, and midazolam were used to control the seizures. However, the seizures persisted, and consciousness was not restored. Thus, a cesarean section was performed under general anesthesia because it was judged that both the mother and fetus could be at risk if the seizures continued.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The seizures continued until general anesthesia was administered, and the cesarean section was performed without any special events. The newborn infant weighed 2680 g, with 1 min and 5 min Apgar scores of 8 and 8, respectively. After delivery by cesarean section, the intensity of the seizures decreased but persisted. Therefore, low-level sedation was maintained with midazolam for about 12 h in the intensive care unit. Over time, the intensity of the seizures decreased, and consciousness was restored. The newborn's nasopharyngeal COVID-19 PCR test was negative and thyroid function tests were within the normal ranges. Magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalogram were performed on the infant in consultation with the neurologist, and no specific findings were observed.

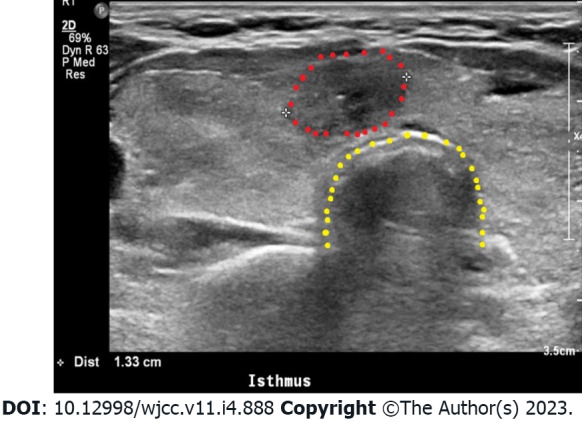

The patient was then referred to an endocrinologist for evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism. In the serological test, TSH (< 0.01 mIU/L) was suppressed, but the free T4 (1.86 ng/dL), total T3 (175.3 ng/dL), and TSH receptor antibody (2.44 IU/L; RR: 0.0-1.750 IU/L[6]) were all elevated with respect to the reference values. Thyroid ultrasonography showed a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland with round-shaped lobes as well as diffusely heterogeneous and coarse echotexture (Figure 1). The isthmus nodule was suspected to be malignant, and fine-needle aspiration was performed (Figure 1). The cytology result showed a papillary carcinoma, and a thyroidectomy was scheduled. The endocrinologist thus concluded that a TS may have been a complication of preexisting Graves' disease and prescribed methimazole, methylprednisolone, and propranolol. The patient was discharged in a healthy condition ten days after the cesarean section. After approximately one month of using methimazole, the thyroid function test results were close to normal values.

Figure 1.

Thyroid ultrasonography. Diffusely enlarged thyroid gland with rounded lobes showing the diffusely heterogeneous and coarse echotexture of the thyroid gland. The isthmus nodule was suspected to be malignant owing to its ill-defined margin. The red dots indicate the isthmus nodule; this nodule was identified as a papillary carcinoma by fine-needle aspiration cytology. The yellow dots indicate the trachea.

DISCUSSION

Hyperthyroidism can develop in about 0.2% of pregnant women, and Graves' disease is responsible for almost 95% of the cases of hyperthyroidism during pregnancy. A TS is a rare condition that affects about 1% of pregnant women with hyperthyroidism. A TS is a severe exacerbation of thyrotoxicosis, which is an emergency disease that causes tachycardia, hyperthermia, agitation, and altered mental status[2]. It is known that TS has a variety of causes. For example, a TS may occur with an acute disease, such as acute myocardial infarction, stroke, congestive heart failure, or trauma[7]. It is also known that infection or pregnancy itself can trigger a TS[2]. There are several case reports of TS caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection[2,3,8,9]. However, this is the first report of a TS in a pregnant woman with a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Etiology

How does SARS-CoV-2 trigger a TS? Recent studies have answered this question in two ways. First, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor and transmembrane protease serine 2, which are known to play important roles in SARS-CoV-2 invasion of the human host cells, are more highly expressed in thyroid cells than in the lungs, oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx, which may cause a TS[10-12]. Second, Lania et al[8] suggested that SARS-CoV-2 could affect the thyroid cells indirectly through a cytokine storm. This cytokine storm is characterized by hyperactivity of the Th1/Th17 immune response, with increased production of several proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor α[13,14]. Several proinflammatory cytokines can cause excessive and uncontrolled immune responses, eventually leading to a TS.

Pregnancy itself can cause hyperthyroidism, which can eventually lead to a TS. As the circulating estrogen increases during pregnancy, the thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) increases. TBG binds to the circulating T4, reducing the free T4 levels. To compensate for this, the size of the thyroid gland increases, and the production of T4 and T3 increases by 50%[15-17]. Owing to the homogeneity of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and TSH, elevated hCG levels can stimulate the thyroid gland, resulting in further elevation of free T4[17,18]. Millar et al[19] reported that patients with hyperthyroidism during pregnancy were 10 times more likely to develop a TS than during non-pregnancy.

Symptoms

A TS typically manifests clinically as a combination of the following signs and symptoms: Fever, tachycardia, cardiac dysrhythmia, and central nervous system dysfunction[20]. Our patient had a generalized tonic-clonic type of seizure, SE. Specifically, recurrent seizures occurred despite the use of appropriate doses of midazolam, and these were classified as refractory SE (RSE)[21]. According to reports, about 9%-43% of SE cases show a clinical course of RSE[21,22], and the in-hospital mortality of RSE has been reported to be about 15%-33%[23-25]. In the present case, the RSE was classified as new-onset RSE (NORSE) because there were no previous neurological diseases and no preexisting toxic and metabolic causes[26]. In the case of our patient, the fever may have been caused by not only COVID-19 but also by the TS induced by COVID-19. Thus, if SE is caused by the fever of COVID-19, it can also be classified as febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome, which is a subset of NORSE[26].

SARS-CoV-2 can also cause a wide variety of extrapulmonary symptoms owing to its inflammatory effects. For example, cardiac (myocarditis, pericardial effusion, shock), renal (glomerulonephritis), hematological (thrombocytopenic purpura, anemia), neurological (Guillain–Barré syndrome, meningoencephalitis, optic neuritis), and musculoskeletal (myositis, arthritis) complications have been reported[10,27-31].

Diagnosis

There are studies recommending routine thyroid function tests in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection[3,8,32]. In our opinion, if the abovementioned symptoms, namely fever, tachycardia, cardiac dysrhythmia, and central nervous system dysfunction, are observed in pregnant women, it is necessary to conduct routine thyroid function tests.

Additionally, the BWPS is the most widely used criterion for diagnosing a TS. The BWPS is a score that helps to assess the probability of a TS independent of the level of thyroid hormones; it is based solely on clinical and physical criteria[2,4]. The BWPS considers body temperature, central nervous effects, hepatogastrointestinal symptoms, and cardiovascular dysfunction, along with the patient's prior history[33].

There are several neurological diseases that must be differentiated from the perspective of accompanying SE with the help of neurologists. In consideration of the patient's condition, neurological examinations and brain imaging studies should be performed to differentiate intracranial diseases. Among these, the differential diagnoses for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, meningoencephalitis, and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome should be included.

Because the pregnant woman had seizures, eclampsia was suspected initially. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the symptoms and signs of eclampsia accurately. For example, it is important to identify pretibial pitting edema, visual disturbances, and epigastric pain. In our case, the patient showed no such signs. In addition, the patient was normotensive, and there was no proteinuria, fetal growth restriction, thrombocytopenia, kidney failure, hepatic dysfunction, or liver failure. In conclusion, the possibility of eclampsia was judged to be low.

Paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome (PNS) also needs to be differentially diagnosed as an additional disease. PNS is an autoimmune disease and may present with several clinical manifestations, such as encephalitis, autonomic dysfunction, peripheral neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia, and visual disturbances[34]. Clinicians should be hence alert to the possibility of PNS if the patient has a past or family history of cancer or an autoimmune disease[34].

Treatment

An appropriate treatment plan should be developed by evaluating the symptoms of thyrotoxicosis, gestational age, and fetal condition. Treatment of mild thyrotoxicosis in COVID-19 patients without an underlying thyroid disease does not necessitate thionamides, and most of these patients will recover spontaneously[6]. However, patients with a TS should receive prompt treatment with fluids, antithyroid drugs (ATD), steroids, and beta blockers in conjunction with consultation with an endocrinologist.

ATD is the most crucial treatment for TS; it inhibits the synthesis of thyroid hormone by blocking the organification of iodine within the thyroid gland and eventually reducing the amount of thyroid hormone released into circulation. Pregnant women with hyperthyroidism should also be treated with ATD. Either propylthiouracil or methimazole, which are both thionamides, can be used to treat pregnant women with hyperthyroidism. However, methimazole is typically avoided in the first trimester because it has been associated with rare embryopathy, such as esophageal or choanal atresia and aplasia cutis, a congenital skin defect[1]. After the first trimester, either methimazole or propylthiouracil can be used to treat hyperthyroidism. In rare cases, propylthiouracil has been reported to result in clinically significant hepatotoxicity[16]. Therefore, patients should be given information about the risks and benefits of ATD. Fortunately, several published articles suggest that antithyroid treatment carries minimal risk to the fetus during early pregnancy. This risk is lower than is commonly perceived and less than that of untreated thyrotoxicosis[17,18].

However, in our case, it was practically challenging to wait for the effects of ATD to manifest in a state where the change of consciousness was accompanied by continued seizures and the fetal well-being could not be guaranteed. In such cases, if the gestational age is close to term, a cesarean section to terminate the pregnancy may be a good solution. Beta blockers can be used as adjunctive therapy for symptomatic palpitations. Corticosteroids inhibit the peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 and have been shown to improve outcomes in patients with TS[1].

CONCLUSION

Clinicians should always bear in mind that SARS-CoV-2 infections can cause a TS and must routinely perform thyroid function tests in the infected patients. When a TS occurs in a pregnant woman infected with SARS-CoV-2, a treatment plan should be established in consideration of the symptoms of thyrotoxicosis, gestational age, and fetal condition. In the case of a TS occurring at an early gestational age, ATD can be used, and the progression can be monitored. However, if the woman is near the term of gestational age and has multi-organ failure or neurological symptoms, termination of pregnancy by cesarean section may be a good choice.

A TS in a pregnant woman is a very serious and life-threatening emergency. Thus, an urgent multidisciplinary approach involving collaboration among the emergency physician, endocrinologist, obstetrician, neurologist, neonatologist, and anesthesiologist is essential for successful management of the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the kind cooperation of the patient, the family members, and the staff for their assistance in conducting this study.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised accordingly.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: October 27, 2022

First decision: November 11, 2022

Article in press: January 5, 2023

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Freund O, Israel; Magalhães JE, Brazil S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

Contributor Information

Hyo-Eun Kim, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gyeongsang National University Changwon Hospital, Changwon 51472, South Korea.

Juseok Yang, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gyeongsang National University Changwon Hospital, Changwon 51472, South Korea.

Ji-Eun Park, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gyeongsang National University Changwon Hospital, Changwon 51472, South Korea.

Jong-Chul Baek, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gyeongsang National University Changwon Hospital, Changwon 51472, South Korea.

Hyen-Chul Jo, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gyeongsang National University Changwon Hospital, Changwon 51472, South Korea. cholida73@naver.com.

References

- 1.Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 223. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e261–e274. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao AN, Al-Ward RY, Gaba R. Thyroid Storm in a Patient With COVID-19. AACE Clin Case Rep . 2021;7:360–362. doi: 10.1016/j.aace.2021.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan K, Helgeson J, McGowan A. COVID-19 Associated Thyroid Storm: A Case Report. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med . 2021;5:412–414. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2021.5.52692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swee du S, Chng CL, Lim A. Clinical characteristics and outcome of thyroid storm: a case series and review of neuropsychiatric derangements in thyrotoxicosis. Endocr Pract . 2015;21:182–189. doi: 10.4158/EP14023.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ACEP American College of Emergency Physicians COVID-19 Field Guide. [cited 24 November 2022]. Available from: https://www.acep.org/corona/covid-19-field-guide/diagnosis/diagnosis-when-there-is-no-testing/

- 6.Cunningham F, Leveno K, Bloom S, Dashe J, Hoffman B, Casey B, Spong C. Williams Obstetrics. 25th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Education, 2018: 1258. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nai Q, Ansari M, Pak S, Tian Y, Amzad-Hossain M, Zhang Y, Lou Y, Sen S, Islam M. Cardiorespiratory Failure in Thyroid Storm: Case Report and Literature Review. J Clin Med Res . 2018;10:351–357. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3106w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lania A, Sandri MT, Cellini M, Mirani M, Lavezzi E, Mazziotti G. Thyrotoxicosis in patients with COVID-19: the THYRCOV study. Eur J Endocrinol . 2020;183:381–387. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pastor S, Molina Á Sr, De Celis E. Thyrotoxic Crisis and COVID-19 Infection: An Extraordinary Case and Literature Review. Cureus . 2020;12:e11305. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pranasakti ME, Talirasa N, Rasena HA, Purwanto RY, Anwar SL. Thyrotoxicosis occurrence in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond) . 2022;78:103700. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell . 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazartigues E, Qadir MMF, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Endocrine Significance of SARS-CoV-2's Reliance on ACE2. Endocrinology . 2020;161 doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: An emerging target of JAK2 inhibitor Fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect . 2020;53:368–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prompetchara E, Ketloy C, Palaga T. Immune responses in COVID-19 and potential vaccines: Lessons learned from SARS and MERS epidemic. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol . 2020;38:1–9. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moleti M, Di Mauro M, Sturniolo G, Russo M, Vermiglio F. Hyperthyroidism in the pregnant woman: Maternal and fetal aspects. J Clin Transl Endocrinol . 2019;16:100190. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2019.100190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar S, Bischoff LA. Management of Hyperthyroidism during the Preconception Phase, Pregnancy, and the Postpartum Period. Semin Reprod Med . 2016;34:317–322. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper DS, Laurberg P. Hyperthyroidism in pregnancy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol . 2013;1:238–249. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stagnaro-Green A, Dong A, Stephenson MD. Universal screening for thyroid disease during pregnancy should be performed. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;34:101320. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2019.101320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Millar LK, Wing DA, Leung AS, Koonings PP, Montoro MN, Mestman JH. Low birth weight and preeclampsia in pregnancies complicated by hyperthyroidism. Obstet Gynecol . 1994;84:946–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross DS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, Greenlee MC, Laurberg P, Maia AL, Rivkees SA, Samuels M, Sosa JA, Stan MN, Walter MA. 2016 American Thyroid Association Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hyperthyroidism and Other Causes of Thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid . 2016;26:1343–1421. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossetti AO, Lowenstein DH. Management of refractory status epilepticus in adults: still more questions than answers. Lancet Neurol . 2011;10:922–930. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayer SA, Claassen J, Lokin J, Mendelsohn F, Dennis LJ, Fitzsimmons BF. Refractory status epilepticus: frequency, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Arch Neurol . 2002;59:205–210. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strzelczyk A, Ansorge S, Hapfelmeier J, Bonthapally V, Erder MH, Rosenow F. Costs, length of stay, and mortality of super-refractory status epilepticus: A population-based study from Germany. Epilepsia . 2017;58:1533–1541. doi: 10.1111/epi.13837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delaj L, Novy J, Ryvlin P, Marchi NA, Rossetti AO. Refractory and super-refractory status epilepticus in adults: a 9-year cohort study. Acta Neurol Scand . 2017;135:92–99. doi: 10.1111/ane.12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferlisi M, Shorvon S. The outcome of therapies in refractory and super-refractory convulsive status epilepticus and recommendations for therapy. Brain . 2012;135:2314–2328. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch LJ, Gaspard N, van Baalen A, Nabbout R, Demeret S, Loddenkemper T, Navarro V, Specchio N, Lagae L, Rossetti AO, Hocker S, Gofton TE, Abend NS, Gilmore EJ, Hahn C, Khosravani H, Rosenow F, Trinka E. Proposed consensus definitions for new-onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE), febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), and related conditions. Epilepsia . 2018;59:739–744. doi: 10.1111/epi.14016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Mariette X. Systemic and organ-specific immune-related manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Rev Rheumatol . 2021;17:315–332. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00608-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, Nair N, Mahajan S, Sehrawat TS, Bikdeli B, Ahluwalia N, Ausiello JC, Wan EY, Freedberg DE, Kirtane AJ, Parikh SA, Maurer MS, Nordvig AS, Accili D, Bathon JM, Mohan S, Bauer KA, Leon MB, Krumholz HM, Uriel N, Mehra MR, Elkind MSV, Stone GW, Schwartz A, Ho DD, Bilezikian JP, Landry DW. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med . 2020;26:1017–1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maev IV, Shpektor AV, Vasilyeva EY, Manchurov VN, Andreev DN. [Novel coronavirus infection COVID-19: extrapulmonary manifestations] Ter Arkh . 2020;92:4–11. doi: 10.26442/00403660.2020.08.000767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laya BF, Cledera THC, Lim TRU, Baluyut JMP, Medina JMP, Pasia NV. Cross-sectional Imaging Manifestations of Extrapulmonary Involvement in COVID-19 Disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr . 2021;45:253–262. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000001120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freund O, Eviatar T, Bornstein G. Concurrent myopathy and inflammatory cardiac disease in COVID-19 patients: a case series and literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42:905–912. doi: 10.1007/s00296-022-05106-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller I, Cannavaro D, Dazzi D, Covelli D, Mantovani G, Muscatello A, Ferrante E, Orsi E, Resi V, Longari V, Cuzzocrea M, Bandera A, Lazzaroni E, Dolci A, Ceriotti F, Re TE, Gori A, Arosio M, Salvi M. SARS-CoV-2-related atypical thyroiditis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol . 2020;8:739–741. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30266-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burch HB, Wartofsky L. Life-threatening thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid storm. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am . 1993;22:263–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kannoth S. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome: A practical approach. Ann Indian Acad Neurol . 2012;15:6–12. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.93267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]