Abstract

Introduction:

The Alzheimer’s disease (AD) continuum begins with a long asymptomatic or preclinical stage, during which amyloid beta (Aβ) is accumulating for more than a decade prior to widespread cortical tauopathy, neurodegeneration, and manifestation of clinical symptoms. The AHEAD 3–45 Study (BAN2401-G000-303) is testing whether intervention with lecanemab (BAN2401), a humanized immunoglobulin 1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that preferentially targets soluble aggregated Aβ, initiated during this asymptomatic stage can slow biomarker changes and/or cognitive decline. The AHEAD 3–45 Study is conducted as a Public-Private Partnership of the Alzheimer’s Clinical Trial Consortium (ACTC), funded by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Eisai Inc.

Methods:

The AHEAD 3–45 Study was launched on July 14, 2020, and consists of two sister trials (A3 and A45) in cognitively unimpaired (CU) individuals ages 55 to 80 with specific dosing regimens tailored to baseline brain amyloid levels on screening positron emission tomography (PET) scans: intermediate amyloid (≈20 to 40 Centiloids) for A3 and elevated amyloid (>40 Centiloids) for A45. Both trials are being conducted under a single protocol, with a shared screening process and common schedule of assessments. A3 is a Phase 2 trial with PET-imaging end points, whereas A45 is a Phase 3 trial with a cognitive composite primary end point. The treatment period is 4 years. The study utilizes innovative approaches to enriching the sample with individuals who have elevated brain amyloid. These include recruiting from the Trial-Ready Cohort for Preclinical and Prodromal Alzheimer’s disease (TRC-PAD), the Australian Dementia Network (ADNeT) Registry, and the Japanese Trial Ready Cohort (J-TRC), as well as incorporation of plasma screening with the C2N mass spectrometry platform to quantitate the Aβ 42/40 ratio (Aβ 42/40), which has been shown previously to reliably identify cognitively normal participants not likely to have elevated brain amyloid levels. A blood sample collected at a brief first visit is utilized to “screen out” individuals who are less likely to have elevated brain amyloid, and to determine the participant’s eligibility to proceed to PET imaging. Eligibility to randomize into the A3 Trial or A45 Trial is based on the screening PET imaging results.

Result:

The focus of this article is on the innovative design of the study.

Discussion:

The AHEAD 3–45 Study will test whether with lecanemab (BAN2401) can slow the accumulation of tau and prevent the cognitive decline associated with AD during its preclinical stage. It is specifically targeting both the preclinical and the early preclinical (intermediate amyloid) stages of AD and is the first secondary prevention trial to employ plasma-based biomarkers to accelerate the screening process and potentially substantially reduce the number of screening PET scans.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid, immunotherapy, prevention

1 |. BACKGROUND

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive decline including memory loss. The neuropathological hallmarks of AD include extracellular accumulation of amyloid plaques composed of amyloid β peptide (Aβ) and subsequent intracellular aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau that forms neurofibrillary tangles. Convergent findings from neuroimaging, fluid biomarker, and neuropathologic research suggest that the AD pathophysiological process progresses on a continuum with underlying Aβ and tau pathologies beginning 10 to 20 years before the onset of clinical symptoms. It is anticipated that most effective disease modification may be during this early stage of disease.1 “Preclinical AD” is defined as the stage of AD where accumulation of amyloid is present in the cortex before manifestation of any clinical impairment.2,3 The symptoms of cognitive impairment develop when a threshold level of neurodegeneration is reached within the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, areas that are involved in memory. Further progression to dementia is associated with the spread of neurofibrillary tangle pathology, and progressive synaptic and neuronal loss in association cortices responsible for other higher cognitive functions.4–7

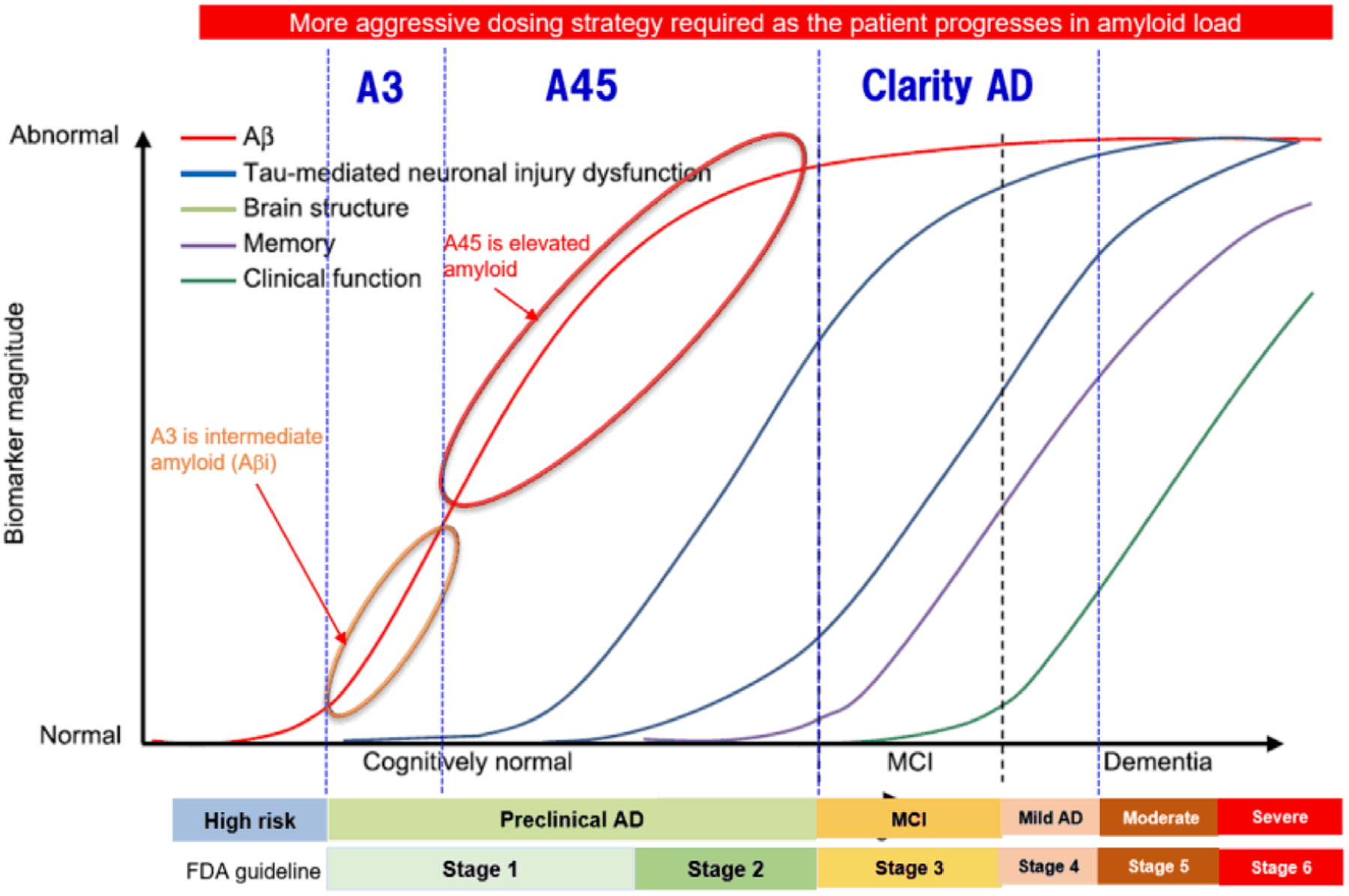

The AHEAD 3–45 Study (BAN2401-G000-303) was launched on July 14, 2020 and consists of two sister trials. The A3 Trial is enrolling participants with early preclinical AD with intermediate brain amyloid beta levels (Aβi, ≈20 to 40 Centiloids) (Figure 1). The A45 Trial is enrolling participants with preclinical AD with elevated brain amyloid levels (>40 Centiloids). Aβi levels are considered below the threshold for elevated amyloid but are in a range at risk for further amyloid accumulation.

FIGURE 1.

Model of progression of biomarkers over the course of AD. Aβ42, amyloid beta monomer from amino acid 1 to 42; Aβi, intermediate amyloid beta; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography

Cognitively normal individuals with abnormal amyloid biomarkers have more rapid progression of neurodegeneration (atrophy, hypometabolism), and clinical/cognitive decline than individuals without biomarker evidence of Aβ (Aβ deposition).7 Relative to individuals without brain amyloid, individuals with preclinical AD have an increased risk of cognitive decline over 3 to 5 years on sensitive composite outcome measures (Preclinical AD Cognitive Composite [PACC] scale) in longitudinal studies of aging.8–12 In addition, individuals who are subthreshold for amyloid positivity on amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) (also known as intermediate Aβ [or Aβi]), who are accumulating amyloid (“Early Preclinical AD,” and are in the “Alzheimer’s continuum” according to the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association [NIA-AA] Research Framework). They are also at risk for future progression. Not only the presence but also the rate of accumulation of amyloid is a risk factor for symptom onset and further neurodegeneration.13,14 Recent evidence suggests that in vivo measures of Aβ deposition below a threshold indicative of Aβ positivity (commonly used as a diagnostic for clinical study research) provide important risk information on future cognitive decline and accumulation of AD pathophysiology.15 Longitudinal data of florbetapir (FBP) PET imaging from the Harvard Aging Brain Study (HABS) demonstrate amyloid accumulation over time as expected in participants who are amyloid positive, but also among participants who were subthreshold for amyloid positivity at baseline.14 Thus early therapeutic intervention targeting the Aβ pathway before significant and irreversible neurodegeneration may provide an approach to prevent or delay cognitive decline and dementia.

The current clinical study will test this approach in two participant populations: early preclinical AD with Aβi (A3 Trial) and preclinical AD with elevated amyloid (A45 Trial). The eligibility for the A3 trial requires intermediate amyloid, defined as amyloid PET ≈20 to 40 Centiloids. The level of amyloid corresponds to the limits of detection of amyloid plaques on neuropathology, the range at which a reliable accumulation of amyloid into the elevated range over 2 to 4 years, and the range of overlap of the bimodal distribution of amyloid PET standard uptake value ratio (SUVr) in cognitively normal individuals.16,17 In addition, this is where there is a shift in the trajectory of the PACC slope (Ferrell et al.14 as well as the pathological change in Aβ from Thal stage 0 to 2 to Thal stage 3 to 5).18 Eligibility for the A45 trial requires elevated amyloid, defined as amyloid PET > 40 Centiloids. The level of amyloid is associated with risk for cognitive decline on Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite 5 (PACC5)19 over 4 years, risk for spread of tau beyond the medial temporal cortex on tau PET, and coincides with the visual amyloid read cutoff for amyloid positivity.20,17,21

The AHEAD 3–45 Study is a 216-week multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-treatment arm study in participants with preclinical AD and elevated amyloid (A45 Trial) and participants with early preclinical AD and Aβi (A3 Trial). Aβi levels are considered below the threshold for elevated amyloid but are in a range at risk for further amyloid accumulation. We selected 216 weeks based on the estimated changes seen on PACC and amyloid SUVR in Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) as well as the effect size of lecanemab. For the purpose of this study, these A3 Trial participants are defined as “early preclinical AD,” and the amyloid levels are termed “intermediate.” Amyloid pathology will be confirmed for all participants by quantitative amyloid PET. All study participants will be on the “Alzheimer’s continuum” according to the NIA-AA Research Framework.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Compound overview and clinical experience

Lecanemab (BAN2401) is a novel humanized immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that preferentially binds to Aβ protofibrils, a high-molecular-weight soluble species of aggregated Aβ. Protofibrils have been implicated in altering synaptic function and mediating neurotoxicity leading to cognitive decline and, ultimately, the dementia observed as AD progresses clinically.22 Binding of lecanemab to protofibrils and fibrils (the component of plaques) is thought to enhance their clearance, with a subsequent neutralization of toxicity to neurons resulting in less neurodegeneration and cognitive decline.23 Results from a phase 2 study in early AD demonstrated that the antibody reduced brain amyloid by up to 93% in the highest-dose group (10 mg/kg biweekly). This dose slowed cognitive decline by 47% on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale - Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog), and by 30% on the ADCOMS.23 The next-lower dose, 10 mg/kg monthly, showed a trend toward slower cognitive decline. In an analysis of CSF from a subgroup of patients, the treatment caused a dose-dependent rise in CSF Aβ42, reflecting target engagment. MRI scans detected Amyloid Related Imaging Abnormality - Edema (ARIA-E) with an incidence of <10% at the highest doses for the overall population and 14.3% for apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4-positive participants. Amyloid Related Imaging Abnormality - Hemorrhage (ARIA-H) (new cerebral microhemorrhages, cerebral macrohemorrhages, and superficial siderosis) regardless of the presence of ARIA-E were observed in 5.3% of participants in the placebo group compared to 10.7% of participants in the lecanemab groups. Most ARIA occurrences were asymptomatic.24 Lecanemab is being studied in Clarity AD, a phase 3 clinical trial in early AD, which completed enrollment in March 2021 with 1795 patients (NCT01767311).

2.2 |. Study design overview

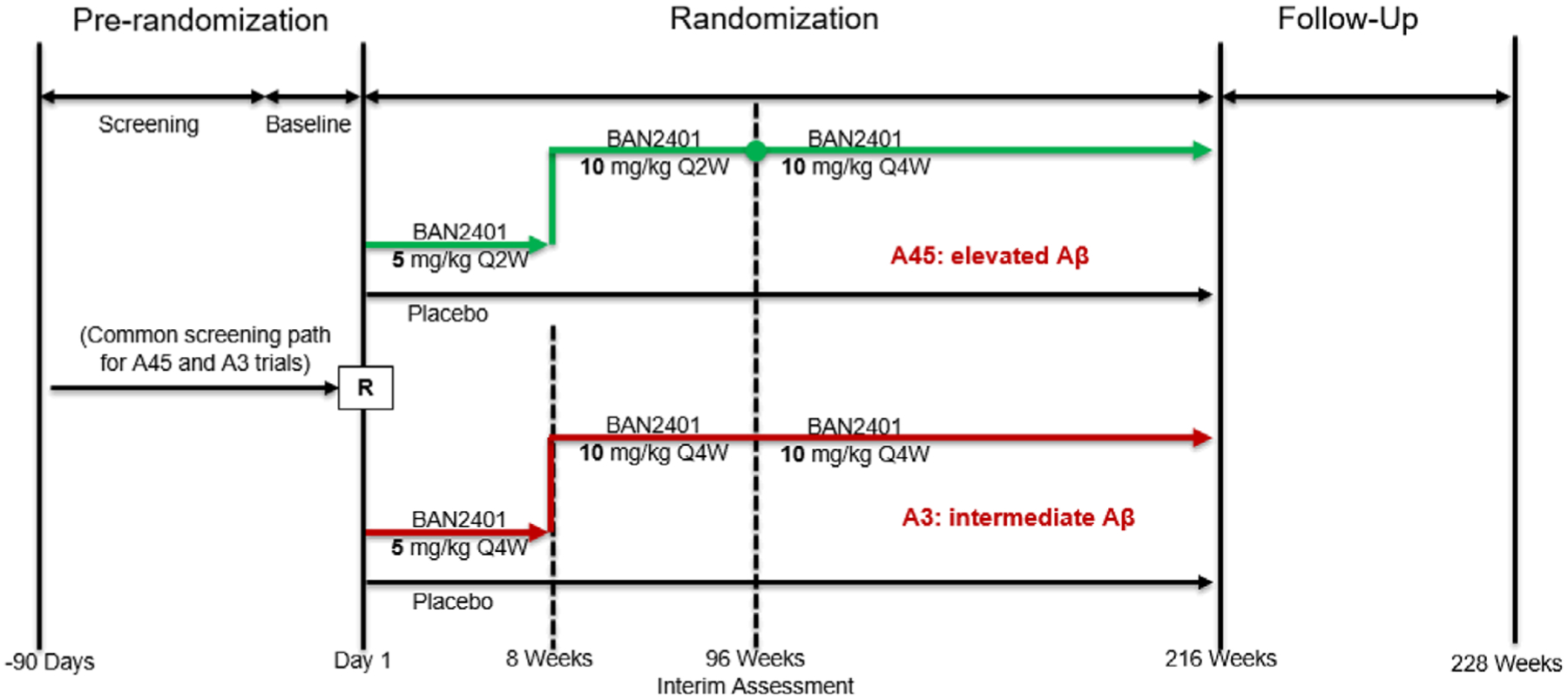

Randomization for both trials are stratified according to APOE ε4 status (ie, APOE ε4 carriers or non-carriers) and geographical region. Treatment duration for individual participants is 216 weeks and a follow-up visit will be performed 12 weeks following the last scheduled infusion. For all participants, longitudinal cognitive, clinical, safety, fluid biomarker, and imaging biomarker assessments will be collected. Amyloid and tau PET assessments will also be conducted for all participants. Participants may choose to participate in the optional longitudinal CSF sub-study. An overview of the study design is presented (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Study design for BAN2401-G000-303. Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; R, randomization. Green indicates the A45 Trial, Red indicates the A3 Trial

2.2.1 |. A45 Trial

Approximately 1000 participants with preclinical AD (elevated amyloid > ≈40 Centiloids) will be randomized according to a fixed 1:1 schedule to receive either (1) placebo intravenously every 2 weeks for 94 weeks, and then every 4 weeks for 120 weeks or (2) BAN2401 5 mg/kg every 2 weeks for 6 weeks (titration), then 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for 86 weeks (induction), and then 10 mg/kg every 4 weeks for 120 weeks (maintenance).

2.2.2 |. A3 Trial

Approximately 400 participants with early preclinical AD with Aβi (≈20–40 Centiloids) will be randomized according to a fixed 1:1 schedule to receive either (1) placebo or (2) lecanemab 5 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks for 4 weeks (titration), then 10 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks for 208 weeks.

2.2.3 |. Enrichment

The AHEAD study will utilize two innovative approaches to identify and recruit individuals in the preclinical stage of AD, that is, individuals who have elevated brain amyloid or have intermediate brain amyloid. The first approach includes direct recruitment from the existing Trial-Ready Cohort for Preclinical and Prodromal Alzheimer’s disease (TRC-PAD) program, which aims to accelerate enrollment into clinical trials for AD by building a cohort of biomarker-confirmed eligible (elevated brain amyloid) participants. The first stage of the program is remote recruitment of participants to the Alzheimer Prevention Trials (APT) Webstudy. Participants are followed with quarterly assessments, and through an algorithm identified as potentially at high risk and referred to clinical sites. Participants are screened for Trial-ready cohort (TRC) eligibility, involving cognitive testing, genotyping, and amyloid biomarker measures, and then if eligible, they are enrolled and followed longitudinally until an appropriate clinical trial becomes available.25,26 Similar approaches are being used globally including Australian Dementia Network (ADNeT) Registry and the Japanese Trial Ready Cohort (J-TRC).

The second approach is by use of the C2N mass spectrometry platform to quantitate the plasma amyloid beta 42/40 ratio (Aβ 42/40) to identify individuals likely to have elevated brain amyloid and to refer them for screening in the AHEAD 3–45 Study. Plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 is reported to have a high correspondence with amyloid PET status (receiver operating characteristic area under the curve [AUC] 0.88, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.82–0.93).27 This study will use study-specific plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 thresholds to rule out participants not likely to be eligible based on PET imaging, and eligibility rates will be monitored in real time, with cut-offs adjusted where needed to ensure accuracy across socio-economic groups.

2.2.4 |. Blinding

All participants and all personnel involved with the conduct and interpretation of the study, including investigators, site personnel, ACTC Coordinating Center, and sponsor staff will be masked to the treatment codes. An unblinded pharmacist will prepare blinded infusion material for administration to the subject. In addition, any study-specific and potentially unblinding data (such as ARIA and infusion reactions) will be designated as sensitive and access will be restricted. Only independent study team members have access to this restricted data, which includes medical-monitoring support. The remainder of the study team has access to only non-sensitive study data. To ensure rapid, real-time safety monitoring, two teams provide medical monitoring oversight and support, one that is blinded to potentially unblinding information and one that is not.

2.2.5 |. Efficacy measures

The primary outcome measure for the A45 Trial is the cognitive outcome measure PACC5, which includes assessments of episodic memory, timed executive function, semantic memory, and a global measure.19 Based on longitudinal cohort studies, the PACC5 is sensitive to cognitive decline in cognitively normal amyloid-positive individuals (relative to amyloid-negative individuals) over 3 to 4 years.8,12

The primary outcome measure for the A3 Trial is amyloid PET and the key secondary outcome measure is tau PET. Because robust cognitive changes are not anticipated in this early preclinical AD population over 4 years, cognitive outcome measures are exploratory.

To evaluate changes in amyloid and tau in these very early stages of the disease, the study will use the most sensitive PET tracers with the least off-target binding for measuring amyloid and tau. These will be exclusively [18F] NAV4694 for amyloid and [18F] MK6240 for tau.

2.2.6 |. Biomarker outcomes

Key secondary biomarker outcomes will be used to assess effects on the pathophysiology of AD: amyloid (amyloid PET) and tau (tau PET). Exploratory biomarkers include measures of amyloid (plasma Aβ42, Aβ40, Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and CSF Aβ42, Aβ0, Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio), measures of tau (tau PET, CSF p-tau-217,p-tau-181, and total tau), and measures of neurodegeneration (CSF NFL, neurogranin).

2.2.7 |. Safety measures

Safety will be assessed by monitoring and recording all adverse events (AEs), monitoring of hematology, blood chemistry, and urinalysis; measurement of vital signs; electrocardiography (ECG); and the performance of physical and neurological examinations, throughout the study. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies will be utilized to assess for eligibility. MRI studies will also be conducted after titration at weeks 8, 12, 24, and 36, to assess for the occurrence of any amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (or ARIAs) and will continue to be collected throughout the study.28 An independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) will convene at regular intervals to monitor the overall safety of the study and in each trial, and to make recommendations to the Study Leadership Team related to study safety and conduct.

2.3 |. Statistical methods

All statistical analyses will be performed following a pre-specified statistical analysis plan (SAP) and conducted after each trial is completed and the database for each trial is locked. A3 Trial data and A45 Trial data will be analyzed separately.

Randomization (with APOE ε4 and geographic region as stratification variables) will be used in this study to avoid bias in the assignment of participants to treatment, to increase the likelihood that known and unknown participant attributes (eg, demographics and baseline characteristics) are balanced across treatment arms in each trial, and to ensure the validity of statistical comparisons across treatment arms in each trial.

All statistical analyses will be performed following a pre-specified statistical analysis plan (SAP) that will be finalized before the database for each trial is locked. Modifications to the analysis plan may therefore be made until the SAP is finalized. The A3 Trial data and A45 Trial data will be analyzed separately.

2.3.1 |. Primary efficacy end point A45 Trial

The primary efficacy analysis will include all randomized participants with PACC5 observations at baseline and at least one follow-up. The primary analysis of the change from baseline in PACC5 at 216 weeks will be performed to compare lecanemab versus placebo using a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM). The MMRM will include baseline PACC5, baseline amyloid PET SUVr, age, treatment arm, APOE ε4 status (carrier, non-carrier), sex, education, geographical region, visit, baseline PACC5-by-visit interaction, and treatment arm-by-visit interaction as fixed effects. The treatment effect for lecanemab versus placebo will be compared at 216 weeks based on MMRM.

The null hypothesis is that there is no difference in the mean change from baseline in PACC5 at 216 weeks between lecanemab and placebo. The corresponding alternative hypothesis is that there is a difference in the mean change from baseline in PACC5 at 216 weeks between lecanemab and placebo.

2.3.2 |. Primary efficacy end point A3 Trial

The primary analysis will include all randomized participants with amyloid PET SUVr at baseline and at least one follow-up. The primary analysis of the change from baseline in amyloid PET SUVr t 216 weeks will be performed to compare lecanemab versus placebo using MMRM. The MMRM will include baseline amyloid PET SUVr, age, treatment arm, APOE ε4 status (positive, negative), sex, education, geographical region, visit, baseline-by-visit interaction, and treatment arm-by-visit interaction as fixed effects. The treatment effect for lecanemab versus placebo will be compared at 216 weeks based on MMRM. The least-squared (LS) means, difference in LS means, and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) will be presented. The null hypothesis is that there is no difference in the mean change from baseline in amyloid PET SUVr at 216 weeks between lecanemab and placebo. The corresponding alternative hypothesis is that there is a difference in the mean change from baseline in amyloid PET SUVr at 216 weeks between BAN2401 and placebo.

2.3.3 |. Safety analysis

Evaluations of safety will be performed on the safety analysis set of all randomized participants receiving study intervention, and will be conducted within each trial separately. The incidence of AEs (including changes from baseline in physical examination), out-of-normal-range laboratory safety test variables, abnormal ECG findings, and out-of-range vital signs, along with change from baseline in laboratory safety test variables, ECGs, and vital sign measurements will be summarized by treatment arm.

3 |. DISCUSSION

The AHEAD A3–45 Study is designed to investigate whether clearance of aggregated forms of Aβ in participants with preclinical AD (elevated brain amyloid) and in participants with early preclinical AD (intermediate brain amyloid), is efficacious in slowing the progression of the AD pathophysiological continuum and onset of cognitive decline. The study utilizes the existing TRC-PAD, ADNeT, and J-TC-PAD infrastructure to enrich the study population with amyloid-positive individuals in the preclinical and early preclinical stages of AD. It also uses plasma biomarkers to identify individuals to screen out individuals who are unlikely to have elevated brain amyloid on PET. Both strategies should help reduce screen failure rates and enrich the sample while increasing the trial’s efficiency.

There are several benefits of a platform study with “adjacent” populations recruited at the sites with parallel cognitive and biomarker assessments. The overlapping screening process provides efficiency in recruiting eligible participants into the appropriate study. In addition, the use of a single master protocol allows for efficient study modifications and operational adjustments to be done on a global basis. The A3 and A45 components each have different end points, which is necessitated by each study population’s stage of disease as well as our current ability to detect cognitive change in the asymptomatic, preclinical, and early preclinical populations. Moreover, current regulatory guidance for approval is different at these stages, where a single cognitive end point and surrogate biomarker end point can be used to obtain accelerated approval for the preclinical stage. The study is expected to face recruitment challenges, specifically identifying asymptomatic populations with age as young as 55 who have elevated or intermediately elevated brain amyloid experienced in the A4 study.29 The study team is prioritizing the recruitment of groups historically excluded and under-represented in clinical trials, including in the first preclinical study of AD, the A4 study.30 Recruitment challenges, experienced across clinical trials and in particular studies recruiting individuals older than 60 years of age, have already been experienced as a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Finally, incorporation of biofluid measures (eg, p-tau 217) as secondary/exploratory outcomes represent an exciting new path for understanding disease-modifying effects and providing supportive evidence for target engagement.

The primary objective of the A45 Trial is to determine whether treatment with lecanemab is superior to placebo on cognition, as measured by change from baseline of the PACC5 at 216 weeks of treatment. This is further advanced by the A3 Trial, which includes individuals with early preclinical AD who represent an intermediate stage between normal and elevated brain amyloid but are nonetheless at higher risk of developing AD. The hypothesis of the study is that a treatment regimen consisting of lecanemab for protofibril clearance “induction therapy” followed by “maintenance therapy” to prevent re-accumulation in participants with preclinical AD will delay both the tau-neurodegenerative process and onset of cognitive decline.

The study includes several innovations such as screening with plasma biomarkers, use of a 20 Centiloid threshold to identify individuals with intermediate brain amyloid for the A3 Trial, utilizing sister trials in a shared screening platform, and individualized dosing for level of amyloid at screening. The overarching rationale of the AHEAD 3–45 Study platform is that the benefits of amyloid removal may be optimized by the earliest feasible intervention, prior to extensive irreversible neurodegeneration and at the initial stages of disease pathogenesis.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic Review: In this article the authors used traditional sources such as PubMed. Previous clinical trials focused mainly on the impact of anti-amyloid immunotherapy on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progression in the later, more symptomatic stages. The appropriate articles have been cited in the article.

Interpretation: The article presents the design of a new study that will test an anti-amyloid immunotherapy in 1000 preclinical and 400 early preclinical participants and incorporated plasma biomarkers to select participants for eligibility.

Future directions: This study will test an anti-amyloid immunotherapy in the earliest stages of AD where it is believed that we have the greatest chance for disease modification and efficacy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the site principal investigators, staff, and participants and their families for their involvement in this study. We also thank the ACTC Participant Advisory Board for providing feedback on study design and conduct plans. No data from human subjects were required for this manuscript and, therefore, informed consent was not necessary.

DISCLOSURES

MSR, RSA, MCD, GS, RAR, SW, RR, KAJ, and PSA receive research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Eisai for this project. JZ, CR, MCI, SD, LDK, CJS, Dj, JL, and SK are employees of Eisai, Inc.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no interests to disclose. Author disclosures are available in the supporting information.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rafii MS, Aisen PS. The search for Alzheimer disease therapeutics—same targets, better trials?. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(11):597–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling R, Aisen P, Becket L, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzhemer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FDA. Early Alzheimer’s disease: developing drugs for treatment guidance for industry draft guidance, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Sperling RA, Mormino E, Johnson K. The evolution of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: implications for prevention trials. Neuron. 2014;84:608–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson K, Schultz A, Betensky R, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(1):110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He Z, Guo JL, McBride JD, et al. Amyloid-β plaques enhance Alzheimer’s brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat Med. 2018;24(1):29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, et al. The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(8):961–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weintraub S, Carrillo SC, Farias ST, et al. Measuring cognition and function in the preclinical stage Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;4:64–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanseeuw B, Betensky R, Jacobs H, et al. Association of amyloid and tau with cognition in preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(8):915–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donohue M, Sperling R, Petersen R, et al. Association between elevated brain amyloid and subsequent cognitive decline among cognitively normal persons. JAMA. 2017;317(22):2305–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mormino E, Papp K, Rentz D, et al. Early and late change on the preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite in clinically normal older individuals with elevated amyloid β. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonenko G, Shoai M, Bellou E, et al. Genetic risk for Alzheimer disease is distinct from genetic risk for amyloid deposition. Ann Neurol. 2019;86(3):427–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrell ME, Jiang S, Schultz AP, et al. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative and the Harvard aging brain study. Neurology. 2021;96(4):e619–e631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bischof GN, Jacobs H. Subthreshold amyloid and its biological and clinical meaning. Neurology. 2019;93(2):72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, et al. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(3):205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villeneuve S, Rabinovici GD, Cohn-Sheehy BI, et al. Existing Pittsburgh Compound-B positron emission tomography thresholds are too high: statistical and pathological evaluation. Brain. 2015;138:2020–2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joie RL, Ayakta N, Seeley WW, Borys E, et al. Multi-site study of the relationships between ante mortem [11C]PiB-PET Centiloid values and post mortem measures of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(2):205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papp KV, Rentz DM, Orlovsky I, Sperling RA, Mormino EC. Optimizing the preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite with semantic processing: the PACC5. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2017;3(4):668–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sperling RA, Morimino EC, Schultz AP, et al. The impact of amyloid—beta and tau on prospective cognitive decline in older individuals. Ann Neurol. 2019;85:181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villain N, Chételat G, Grassiot B, et al. Regional dynamics of amyloid-β deposition in healthy elderly, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a voxelwise PiB–PET longitudinal study. Brain. 2012;135:2126–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philipson O, Lord A, Lalowski M, et al. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(5):1010.e1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson CJ, Zhang Y, Dhadda S, et al. Clinical and biomarker updates from BAN2401 Study 201 in early AD. Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease Conference: 24–27 October 2018; Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swanson CJ, Zhang Y, Dhadda S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase 2b proof-of-concept clinical trial in early Alzheimer’s disease with lecanemab, an anti-Aβ protofibril antibody. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13(1):80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aisen PS, Sperling RA, Cummings J, et al. The trial-ready cohort for preclinical/prodromal Alzheimer’s disease (TRC-PAD) project: an overview. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2020;7(4):208–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langford O, Raman R, Sperling RA, et al. Predicting amyloid burden to accelerate recruitment of secondary prevention clinical trials. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2020;7(4):213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schindler SE, Bollinger JG, Ovod V, et al. High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology. 2019;93(17):e1647–e1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sperling RA, Jack CR Jr, Black SE, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(4):367–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sperling RA, Donohue MC, Raman R, et al. Association of factors with elevated amyloid burden in clinically normal older individuals. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):735–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raman R, Quiroz YT, Langford O, et al. Disparities by race and ethnicity among adults recruited for a preclinical Alzheimer disease trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2114364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]