Abstract

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) is the second largest grain crop worldwide, and one of the three major grain crops produced in China. Take-all disease, caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici (Ggt) infection, is a widespread and devastating soil-borne disease that harms wheat production. At present, the prevention and control of wheat take-all depend largely on the application of chemical pesticides. Chemical pesticides, however, not only lead to increased drug resistance of pathogens but also leave significant residues in the soil, causing serious environmental pollution. In this study, we investigated the application of Bacillus subtilis to achieve take-all disease control in wheat while reducing pesticide application. Antagonistic bacteria were screened by plate test, species identification of strains was performed by Gram staining and sequencing of 16s rDNA, secondary metabolite activity of strains was detected by clear circle method, strain compatibility and effect of compounding on Ggt were detected by plate, and the application prospects of specific strains were analyzed by greenhouse and field experiments. We found that five B. subtilis strains, JY122, JY214, ZY133, NW03, Z-14, had significant antagonistic effects against Ggt, and could secrete antimicrobial proteins including amylase, protease, and cellulase. Furthermore, Z-14 and JY214 cultures have also been shown to change the morphology of Ggt mycelium. These results also showed that Z-14, JY214, and their combination can control take-all disease in wheat at a reduced level of pesticide use. In summary, we screened two Bacillus spp. strains, Z-14 and JY214, that could act as antagonists that contribute to the biological control of wheat take-all disease. These findings provide resources and ideas for controlling crop diseases in an environmentally friendly manner.

Keywords: take-all disease, Bacillus subtilis, biological control, combination of strains, antimicrobial protein

Introduction

Wheat is one of the main food crops produced in China, and the most important crops worldwide (Shewry and Hey, 2015). Wheat take-all is a serious global wheat rhizosphere disease caused by the Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici (Ggt) infection. Ggt infests wheat throughout the growing period, with increased yellow leaves on affected plants at the seedling stage, delayed return of diseased seedlings in winter wheat, few tillers, weak growth and dwarfing, and the most pronounced symptom expression at maturity. The degree of soil moisture also affects the incidence of allograft. This disease can also produce disorders in dry areas, but the disease is aggravated under moist soil conditions. Severe cases of take-all disease have caused continuous wheat blight, resulting in loss of yield and quality (Freeman and Ward, 2004; Palma-Guerrero et al., 2021). Because of the extreme difficulty in preventing and controlling wheat take-all disease, it has been called the “cancer of wheat.” Even at the moment, due to the lack of effective disease-resistant cultivars, the control of wheat take-all relies largely on the prolonged use of pesticides that lead to environmental pollution and increased resistance of the pathogen. Considering the unsatisfactory effectiveness of existing biocontrol formulations against Ggt, combining the application of pesticides in reduced dosage with the use of biocontrol formulations with antagonistic effects is becoming a promising strategy (Yu, 2017). Microbial biocontrol agents are deemed to be environmentally friendly, and can replace chemical agents to a certain extent in disease control (Zhang et al., 2021a). Commonly used biocontrol microorganisms currently include bacterial Pseudomonas spp. and Bacillus spp., and fungal Trichoderma, Simplicillium, and Nigrospora (Kaur et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2011, 2018; Jiang and Ding, 2016). A large number of studies have been conducted in recent years on the application of biological control agents for the management of plant pathogens. Carola et al. showed that the combination of Pseudomonas protegens strains with the chemical agent fluoroquinazole has significant effect to control take-all disease (Vera Palma et al., 2019). Application of the biocontrol strain SC11 combined with strains 153 and Fo47 showed a high control efficiency (89.47%) on Fusarium wilt infection in watermelon (Lan et al., 2015). The results of Sun et al. showed that the inhibition efficiency of Bacillus amyloliticus SW-34 suspension on gray mold was 72.29% in ginseng, which was significantly higher than that of fungicide treatment (Sun et al., 2019). It has been found that Bacillus could suppress pathogenic microorganisms in multiple ways, such as by secreting secondary metabolites that damage the cell membranes of pathogenic organisms, by blocking energy metabolic pathways of pathogen cells, by competing with pathogens for ecological sites, by hindering pathogen infestation, and also by producing growth-promoting substances to accelerate plant growth or by inducing systemic resistance in plants (Tanaka et al., 2017; Fira et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2018; Yang, 2019). For instance, it was reported by Myo et al. (2019) that Bacillus velezensis strain NKG-2 inhibits the growth of various pathogenic fungi including Fusarium oxysporum through producing volatile substances. Bacillus cereus strain AR156 colonized the rhizosphere and occupied the loci, and effectively inhibited the infection of Ralstonia solanacearum (Wang et al., 2014a). Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain FS6 colonized in ginseng and exerted its role in enhancing disease resistance by inducing the activity of defense-related enzymes (Wang et al., 2019). However, there are only limited studies on the role of Bacillus subtilis in controlling take-all disease (Zhang et al., 2021b). In this study, we screened for microorganism with inhibitory effect to the growth of Ggt, and found that four B. subtilis strains and the B. amyloliquefaciens strain Z-14 could act as antagonists of Ggt growth. Among which, two strains could promote the growth of wheat seedlings. Our findings could be used in the biocontrol of take-all diseases in wheat, with the aim of reducing pesticide use and promoting wheat growth.

Materials and methods

Cultivation conditions for bacterial and fungal strains

Bacterial strains JY122, JY214, ZY133, NW03, NO36, and JY215 were isolated for both cellulose and lignin degradation availability, from soil near wheat roots in different rural areas in Tangshan, Cangzhou, Daming, Zhengding, and Xingtang in Hebei province, China (Xiong et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021c). Bacterial strains were cultivated in NB medium (10 g/L peptone, 5 g/L beef extract, and 10 g/L sodium chloride, pH 7.3) at 37°C, according to a published protocol (Tao et al., 2021), and Ggt was cultivated in PDA medium at a constant temperature of 26°C.

Screening of antagonists and observation of Ggt mycelium

The procedure for the analysis of the inhibitory effect of different Bacillus spp. on Ggt growth was carried out according to previous reports (Zhang et al., 2014a; Wang et al., 2021). The identical amount of Ggt mycelium were inoculated in the central area of the dishes with PDA medium and the bacterial cultures (which were pre-cultivated till OD600 = 1.0) were inoculated on the medium 2.5 cm apart from the Ggt inoculum and subsequently incubated at 26°C. The experiment was repeated three times, with each containing three technical replicates. Upon extension of mycelium to the edge of the dishes in the control group which was inoculated with Ggt alone, the radius of Ggt mycelium on the dishes inoculated with different Bacillus spp. were measured and the inhibition rate was calculated. Inhibition rate = (the radius of mycelial expansion area of the control group – the radius of mycelial expansion area of the test group) / the radius of mycelial expansion area of the control group × 100%.

Bacterial species identification

Gram staining was carried out according to the method mentioned in a previously reported protocol (Tian et al., 2008). The regions of 16S rDNA of the strains to be identified were amplified with general primers 27F: 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ and 1492R: 5′-TCGCAATATGATCACGGCTA-3′. Bacterial strains cultivated in NB medium to OD600 = 1.0 were used directly as templates for PCR analysis using 2 × rapid taq master mix (Vazyme, China). The thermocycling conditions were 95°C for 5 min (initial denaturation) followed by 35 cycles of 95°C 1 min (denaturation); 55°C 30 s (annealing); and 72°C 1 min 30 s (extension), 72°C 10 min (final extension). PCR products were purified and sequenced using primers that were used to amplify them. The sequencing results of the PCR products were analyzed by using BLAST program against the nucleotide collection (nr) database from NCBI, and the sequence homology was compared with that of the model strains. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by using MEGA7.0 software (Kumar et al., 2016). The similarity between nucleic was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and JTT matrix-based model. The phylogenetic tree was obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a JTT model.

Detection of protease, amylase, and cellulase activities in bacterial secondary metabolites

Bacterial cultures were inoculated into a seed medium (10 g/L peptone, 10 g/L glucose, 2 g/L sodium phosphate monobasic dihydrate, and magnesium sulfate heptahydrate) at a ratio of 1:100 (v:v), cultivated at 37°C for 48 h with shaking, centrifuged, and filtered with a 0.22 μm filter. The filtrate was dropped into the corresponding medium for enzymatic activity detection, and incubated at 37°C for 36–48 h.

Protease activity was detected on skim milk agar plates (Yang et al., 2008). Amylase activity was detected by starch medium, and compound iodine solution was used for color development (Liu et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014b). Cellulase activity was detected on carboxymethyl cellulose agar plates (Saritha et al., 2012; Tokpah et al., 2016).

Detection of compatibility and combination ratio between bacterial strains

The bacterial cultures were evenly coated on plates with NA medium, and the culture of the bacteria to be tested were dropped on it. The medium was incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The appearance of transparent ring around the bacterial inoculation site indicates the incompatibility of the two tested bacteria.

We employed two different mixing approaches to test the inhibitory effect of the combination of two different Bacillus spp. strains on Ggt, namely mix after-cultivation and co-cultivation. The mix after-cultivation refers to the mixing of two Bacillus spp. strains that were pre-cultured in NB medium until OD600 = 1.0, while co-cultivation refers to inoculating a mixture of two Bacillus spp. strains into 100 times the volume of NB medium.

Assessment of the control effect of bacterial strains against Ggt infection

The preventive and control effects of the Bacillus spp. strains against Ggt infection were tested in the greenhouse and in the field. The pesticide used in this study was Koras (27% Thiamethoxam-Cymoxanil-Phenoxymethoxazole, produced by Syngenta, Beijing). In the greenhouse experiments, 50 g of wheat seeds was treated with 1.8% pesticide diluted in dH2O, while in the field experiments, 150 g of wheat seeds was treated with 5% pesticide diluted in dH2O. The greenhouse test consists of ten treatments: treatment 1: Nutrient soil + sterile water, treatment 2: Nutrient soil + Ggt + sterile water, treatment 3: Nutrient soil + Ggt + 1.8% pesticide + sterile water, treatment 4: Nutrient soil + Ggt + Z-14 culture solution, treatment 5: Nutrient soil + Ggt + JY214 culture solution, treatment 6: Nutrient soil + Ggt + mixture of Z-14/JY214 culture solution, treatment 7: Nutrient soil + Ggt + 0.9% pesticide + sterile water, treatment 8: Nutrient soil + Ggt + 0.9% pesticide + Z-14 culture solution, treatment 9: Nutrient soil + Ggt + 0.9% pesticide + JY214 culture solution, treatment 10: Nutrient soil + Ggt + 0.9% pesticide + mixture of Z-14/JY214 culture solution. Plant pots with a diameter of 12.9 cm and a height of 12.4 cm were used in this study. Eight wheat seeds were sown in each pot, and the test was done in three replicates. The pathogen, Ggt, was inoculated by placing pre-cultivated hyphal sheets (7 mm in diameter) on the soil, one wheat seed was placed on each sheet, and irrigated with 30 mL of antagonistic solution containing the bacteria to be tested. Two weeks after germination, the seedlings were irrigated again with antagonistic solution. The stem width, plant height, and root length were measured at about 40 days after germination, and then the average values were calculated. The disease index was calculated depending on the severity of Ggt infestation in wheat seedlings. The disease index was set in five grades according to the proportion of wheat seedlings that were infected with Ggt, according to a previous report (Qiao et al., 2005). Grade 0 = 0%, grade 1 = 1–10%, grade 2 = 11–30%, grade 3 = 31–60%, and grade 4 = 61–100%.

The disease index and disease reduction were calculated according to a report by Chen et al. (2021).

Disease index = [∑ (number of infected plants at all levels × representative value)/total number of investigated plants × representative value of the heaviest disease level] × 100%.

Disease reduction rate = [(control group disease index – treatment group disease index)/control group disease index] × 100%.

The field test was conducted in the experimental field of the meteorological station in Hebei Agricultural University (West campus, Baoding, China). The land used for the experiment had been planted with winter wheat and summer corn for several years. A randomized group design was used for each experiment treatment. All plots were separated and protected with protection rows, compound fertilizer and urea were applied before sowing. The wheat was sowed in October, 2021, and harvested in June, 2022, and the agronomic parameters were recorded at the stage of maturity.

The field test was set up with eight treatments: treatment 1: Blank control, treatment 2: Ggt, treatment 3: Ggt + 5% pesticide, treatment 4: Ggt + 5% pesticide +Z-14 culture solution, treatment 5: Ggt + 5% pesticide + JY214 culture solution, treatment 6: Ggt + 5% pesticide + mixture of Z-14/JY214 culture solution, treatment 7: Ggt + 2.5% pesticide + Z-14 culture solution, treatment 8: Ggt + 2.5% pesticide + mixture of Z-14/JY214 culture solution. The pathogen was inoculated by grinding the Ggt-infested wheat into powder and spreading it evenly on the soil surface of the field. The bacteria were inoculated by centrifuging the culture solution and mixing the precipitate with wheat seeds, and the pesticide was applied similarly in a mixed manner, according to a previous report (Wang et al., 2021).

Results

Ggt was inhibited by certain Bacillus spp. strains

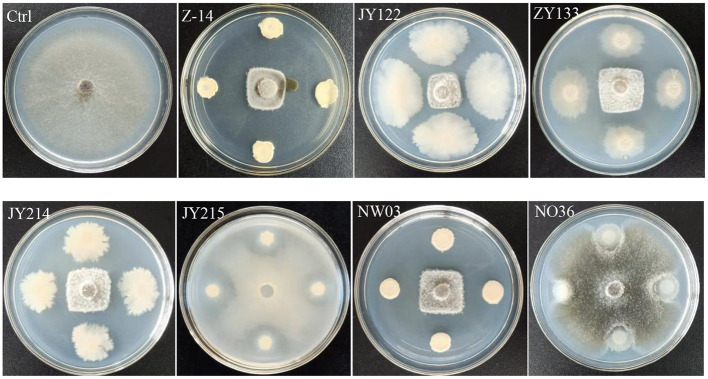

Antagonistic effects of the screened strains on the pathogen of wheat take-all disease, Ggt, were detected by plate antagonistic test. The results showed that strains Z-14, JY122, ZY133, JY214, and NW03 had significant antagonistic effects on the growth of Ggt, while JY215 and NO36 showed only slight inhibition on the growth of Ggt (Figure 1). The inhibition rate of Z-14 to Ggt was as high as 77.58%, and the inhibition rate of JY214 was 73.02% (Table 1). Five strains with good antagonistic effects against wheat take-all were obtained.

Figure 1.

Antagonistic effect of the selected bacteria strains against Ggt. The Ggt were inoculated in the center of PDA plate, and the strains to be tested were inoculated around the Ggt-inoculation sites.

Table 1.

Inhibition rates of seven bacterial strains against Ggt.

| Inoculum | Radius of the bacterial colony (cm) | Inhibition rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis Z-14 | 0.94 ± 0.01a | 77.58 ± 0.34c |

| Bacillus subtilis JY122 | 0.96 ± 0.06a | 77.18 ± 1.50c |

| Bacillus subtilis ZY133 | 1.17 ± 0.04b | 72.22 ± 0.91b |

| Bacillus subtilis JY214 | 1.13 ± 0.01b | 73.02 ± 0.34b |

| Bacillus subtilis JY215 | 2.39 ± 0.06a | 43.06 ± 1.37a |

| Bacillus subtilis NW03 | 0.98 ± 0.04c | 76.79 ± 1.03c |

| Bacillus subtilis NO36 | 2.33 ± 0.04c | 44.64 ± 1.03a |

| CK | - | - |

Values in the table are mean ± standard deviation. Different letters indicate the significant differences (P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple comparison).

Antagonistic bacterial strains JY214, JY122, ZY133, and NW03 were identified to be Bacillus subtilis

Gram staining and 16s rDNA fragment sequencing were performed on the broth to identify the species of the strains specifically. The strains were identified as Gram-positive as they showed a purplish color after Gram staining (Figure 2) and a short rod-shaped body was observed under the microscope. The 16s rDNA of the antagonistic bacteria was amplified, and the sequencing results of the PCR products were compared in the NCBI database for Blast comparison. The results of phylogenetic analysis showed that strains JY214, JY122, ZY133, and NW03 were clustered into a branch, which had a high similarity with B. subtilis strains (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Microscopic images of the selected bacterial strains. Gram stain was used to enhance the visibility of the bacteria. (A) Z-14, (B) JY122, (C) ZY133, (D) JY214, and (E) NW03.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of 16s rDNA sequencing results of antagonistic strains. Nucleic sequences from several stains were used for phylogenetic analysis using the maximum likelihood method and JTT matrix-based model. The scale bar indicates the number of nucleic acid substitutions per site.

Activities of protease, amylase and cellulase in secondary metabolites of the antagonistic strains

The activity of protease, amylase, and cellulase in the metabolites of antagonistic strains were detected. The results showed that clear rings of different sizes were present in the test plates, indicating that the secondary metabolites had the activities of protease, amylase, and cellulase (Figure 4). The average diameter of the clear rings produced by protease activity was more than 0.82 cm, and that of amylase was more than 2.28 cm. Among all the strains tested, ZY133 had the strongest ability to produce protease and protease, generating rings of 1.90 cm and 2.69 cm in diameter, respectively, and that of cellulase was more than 1.98 cm. Z-14 had the strongest cellulase production capability.

Figure 4.

Secondary metabolite detection. Medium containing milk, starch, and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose were used to detect protease, amylase, and cellulase activities, respectively. Secondary metabolites were dropped and cultured at 37°C for 48 h.

Bacillus subtilis strains Z-14 and JY214 are compatible

Having identified that both Z-14 and JY214 have antagonistic effects against Ggt, we wondered if the two strains could function together to provide better performance. No transparent ring of mutual inhibition between strains was observed when Z-14 was coated on NA medium and JY214 was subsequently inoculated (Figure 5A), and there was no appearance of growth inhibition of the two tested bacteria when Z-14 was inoculated on the medium coated with JY214 (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Determination of strain compatibility. (A) After coating Z-14 bacterial solution on NA medium, JY214 bacterial solution was added dropwise on top; (B) After coating JY214 bacterial solution, Z-14 bacterial solution was added dropwise on top.

We subsequently tested the feasible mixing method and the optimal mixing ratio between Z-14 and JY214 (Figure 6). The mixing after-cultivation method of the two strains had a disease reduction rate of over 82% against Ggt, which was not only better than that produced by the co-cultivation method, but also superior to the effect of the two strains alone. Because Z-14 and JY214 could produce a reduction rate of 85.71% against Ggt when mixed at 2:1, we used the mixing ratio of 1:2 in the subsequent study (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Inhibition test of different mixing method and ratios of Z-14 and JY214 against Ggt. Z-14 and JY214 were mixed in ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1 respectively to test the inhibition effect of the mixture on Ggt.

Table 2.

Inhibition rates of different mixing method and ratios of Z-14 and JY214 against Ggt.

| Mixing method and ratio (Z-14:JY214) | Radius of the bacterial colony (cm) | Inhibition rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mix after-cultivation | 1:1 | 0.74 ± 0.17a | 82.34 ± 4.05b |

| 1:2 | 0.60 ± 0.03a | 85.71 ± 0.60b | |

| 2:1 | 0.73 ± 0.23a | 82.74 ± 5.36b | |

| Co-cultivation | 1:1 | 1.13 ± 0.11b | 73.02 ± 2.68a |

| 1:2 | 1.07 ± 0.01b | 74.60 ± 0.34a | |

| 2:1 | 1.06 ± 0.10b | 74.80 ± 2.48a | |

| CK | - | - | |

The a and b different letters indicate the significant differences (P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple comparison).

Effects of Z-14 and JY214 on mycelial growth of Ggt

We next investigated the effect of Z-14 and JY214 on the growth of Ggt mycelium. The mycelium of Ggt without inoculation with antagonistic B. subtilis had smooth surface, uniform morphology, normal development, with more branches, and the angle of branches was acute. After Z-14 treatment, the mycelium of Ggt were miscellaneous, unsaturated and generally thin, the branches were reduced and the angles of branches were uneven; the mycelium of Ggt treated with JY214 basically did not produce branches and the morphology of the main mycelium was changed, indicating that the growth of Ggt mycelium was inhibited under the influence of both Z-14 and JY214 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of Ggt mycelial growth by Z-14 and JY214. The Ggt mycelia treated with Z-14 and JY214 were observed under a microscope. Bars = 20 μm.

Determination of the control effect of antagonistic bacteria Z-14, JY214, and their combination on wheat take-all disease

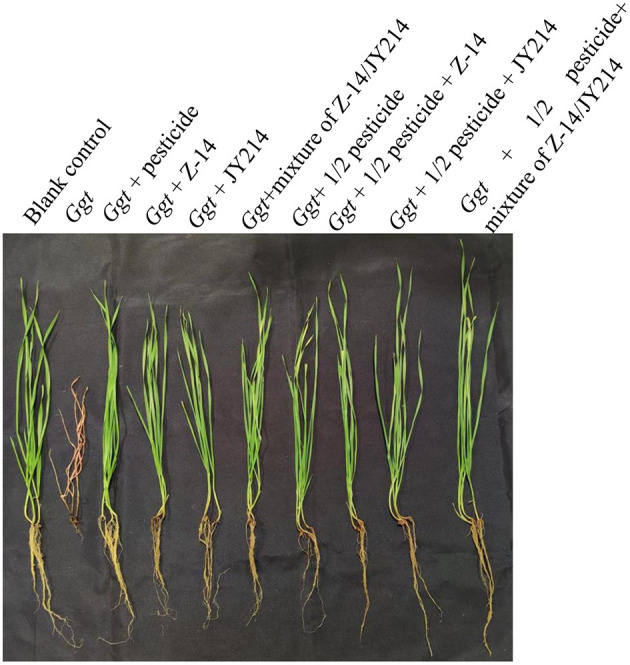

To test the practical effects of Z-14 and JY214 on take-all diseases in wheat, we examined the effects of the two separately and combined in the greenhouse and in the field, and tested whether these combinations could reduce pesticide use. In the greenhouse experiments, the roots were washed 40 d after sowing and the disease condition was checked. In the control group that was inoculated with Ggt only, all the wheat seedlings withered, the disease index of take-all disease reached 100%, while the seedlings treated with pesticide had lower disease-index, and the disease-index of all treatmental groups was reduced compared to the control group inoculated with Ggt only (Table 3). Application of Z-14 or JY214 reduced the disease index induced by Ggt infection to 34–40.63%, indicating that application of both Z-14 and JY214 exerted control on take-all disease, yielding a 59.37–65.62% disease reduction rate. Combined application of Z-14 and JY214 suppresses take-all disease better than their individual effects (Figure 8). As compared to the group with only reducing the pesticide application by 50%, the disease reduction rate reached 68.75%, 69.79%, and 73.96%, by adding Z-14 application, JY214 application, or the co-application of Z-14 and JY214, respectively. Therefore, the application of B. subtilis with a reduced dosage of pesticide by half can better control take-all disease. We further measured the effects of Z-14 and JY214 on three biomass characters, wheat plant height, stem width, and root length. Since all wheat seedlings treated with Ggt were withered, we recorded all their stem widths as 0 mm. Application of either Z-14 or JY214 (or a mixture of the two strains) on the basis of a 50% reduction in pesticide application reduced wheat growth by Ggt (Table 4), with the same results as in our assessment of disease reduction rate in a greenhouse environment.

Table 3.

Control effect of pesticide, Z-14, JY214, and their combinations on wheat take-all disease in the greenhouse experiments.

| Treatments | Disease index (%) | Reduction rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Blank control | 0 | - |

| Ggt | 100 | - |

| Ggt + pesticide | 30.21 | 69.79 |

| Ggt + Z-14 | 40.63 | 59.37 |

| Ggt + JY214 | 39.58 | 60.42 |

| Ggt + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 34.38 | 65.62 |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide | 36.46 | 63.54 |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + Z-14 | 31.25 | 68.75 |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + JY214 | 30.21 | 69.79 |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 26.04 | 73.96 |

Figure 8.

Control effect of pesticide, Z-14, JY214, and their combinations on wheat take-all disease. These treatments were conducted in the greenhouse.

Table 4.

Effects of pesticide, Z-14, JY214, and their combinations on root length, root fresh weight, and aboveground weight of Ggt-infected wheat in the greenhouse experiments.

| Treatments | Stem width (mm) | Plant height (cm) | Root length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank control | 1.40 ± 0.04e | 30.31 ± 0.76d | 14.54 ± 0.40c |

| Ggt | 0.00 ± 0.00a | 6.23 ± 0.57a | 1.94 ± 0.13a |

| Ggt + pesticide | 1.31 ± 0.01b | 28.46 ± 0.58c | 13.42 ± 0.42bc |

| Ggt + Z-14 | 1.34 ± 0.01c | 26.88 ± 0.33b | 13.52 ± 0.75bc |

| Ggt + JY214 | 1.37 ± 0.02cd | 26.54 ± 0.61b | 13.83 ± 0.18bc |

| Ggt + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 1.35 ± 0.02cd | 26.52 ± 0.13b | 13.04 ± 0.58b |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide | 1.35 ± 0.02cd | 28.44 ± 0.56c | 13.83 ± 0.94bc |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + Z-14 | 1.36 ± 0.02cd | 31.13 ± 0.22d | 13.25 ± 0.70b |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + JY214 | 1.37 ± 0.01cde | 32.06 ± 0.38e | 13.75 ± 0.45bc |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 1.39 ± 0.00de | 32.44 ± 0.82e | 13.67 ± 0.83bc |

The a–e different letters indicate the significant differences (P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple comparison).

To imitate a wheat production environment, we conducted experiments in the field to examine the effect of Z-14 and JY214 on the disease-index of Ggt-induced take-all disease and its disease-reduction rate, and measured the biomass characters (Table 5). After inoculation with Ggt, the disease index of take-all in wheat reached 34%. Application of Z-14 on the basis of a 50% reduced dosage of pesticide resulted in the lowest disease-index with a disease reduction rate of 72.12%, while application of a mixture of the two strains, Z-14 and JY214, on the basis of a 50% pesticide application resulted in a take-all disease-index of 16.96% and the disease-reduction rate was 50.12%. In the absence of pesticide application, Z-14, JY214, or their combination could also reduce the disease level of wheat effectively with a disease reduction rate between 51.82 and 54.76%, which was even slightly higher than the disease reduction rate when only pesticide was applied.

Table 5.

Control effect of pesticide, Z-14, JY214, and their combinations on wheat take-all disease in the field experiments.

| Treatments | Disease index (%) | Reduction rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Blank control | 0 | - |

| Ggt | 34.00 | - |

| Ggt + pesticide | 16.67 | 50.97 |

| Ggt + Z-14 | 16.00 | 52.94 |

| Ggt + JY214 | 16.38 | 51.82 |

| Ggt + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 15.38 | 54.76 |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + Z-14 | 9.48 | 72.12 |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 16.96 | 50.12 |

Furthermore, field applications of both the strains of B. subtilis in wheat helped to restore the biomass decline caused by Ggt. All the other groups tested showed higher plant height, root length, and stem width compared to the experiment in which only Ggt was inoculated (Table 6). We next measured wheat yields in each treatment and the yield of wheat after Ggt inoculation was 7,176.05 ton/ha, representing a 10.60% yield reduction relative to the untreated wheat. All the treatments in which B. subtilis or pesticides were applied restored the yield of Ggt-affected wheat to a certain extent, with a high yield of 8,475.60 ton/ha in the treatment in which Z-14 was applied on the basis of 50% pesticide application. The use of B. subtilis and halving treatment with pesticides not only provides better control of wheat total erosion disease, but also maintains and even increases wheat yield (Table 7).

Table 6.

Effects of pesticide, Z-14, JY214, and their combinations on root length, root fresh weight, and aboveground weight of Ggt-infected wheat in the field experiments.

| Treatments | Stem width (cm) | Plant height (cm) | Root length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank control | 0.40 ± 0.01cd | 74.43 ± 1.49c | 14.97 ± 1.82c |

| Ggt | 0.34 ± 0.02a | 65.13 ± 3.26a | 11.26 ± 0.49a |

| Ggt + pesticide | 0.39 ± 0.01bcd | 69.50 ± 1.25b | 14.06 ± 1.04bc |

| Ggt + Z-14 | 0.41 ± 0.02d | 68.10 ± 1.16b | 12.75 ± 0.65ab |

| Ggt + JY214 | 0.37 ± 0.02b | 65.10 ± 0.97a | 12.29 ± 1.72ab |

| Ggt + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 0.38 ± 0.02bc | 63.33 ± 2.21a | 11.15 ± 1.46a |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + Z-14 | 0.37 ± 0.02b | 65.25 ± 1.10a | 13.18 ± 1.10abc |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 0.40 ± 0.02cd | 68.92 ± 1.00b | 12.86 ± 1.36ab |

The a–d different letters indicate the significant differences (P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple comparison).

Table 7.

Effects of pesticide, Z-14, JY214, and their combinations on yield of Ggt-infected wheat in the field treatments.

| Treatments | Number of ears per m2 | Number of grains per ear | 1,000-grain weight /g | Yield*/ton·ha−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank control | 521.00 | 41.67 | 43.50 | 8,027.30 |

| Ggt | 485.00 | 40.90 | 42.56 | 7,176.05 |

| Ggt + pesticide | 503.00 | 42.33 | 43.50 | 7,872.71 |

| Ggt + Z-14 | 509.00 | 42.33 | 43.10 | 7,893.37 |

| Ggt + JY214 | 513.00 | 42.00 | 42.80 | 7,838.43 |

| Ggt + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 511.00 | 42.40 | 43.20 | 7,955.90 |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + Z-14 | 517.00 | 42.67 | 45.20 | 8,475.60 |

| Ggt + 1/2 pesticide + mixture of Z-14/JY214 | 509.00 | 42.33 | 43.00 | 7,875.05 |

*Yield = Number of ears per ha × number of grains per ear × 1,000-grain weight (kg) × 85% / 106.

Discussion

Biocontrol by bacteria treatment has the advantages of eco-friendly, high efficiency, safety and sustainability, which has become a research hotspot of plant disease control and has broad application prospects (Zhang et al., 2022). Bacillus spp. are extensively found in the environment and have been found to produce a multitude of secondary metabolites, some of which (including proteases, cellulases, amylases, etc.) act as fungicides to inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria (Sun et al., 2003; Romero et al., 2007; Brzezinska et al., 2020).

Wang et al. (2020) found that B. amyloliquefaciens HG01 attained control of anthracnose rot in tomato by inhibiting the growth of Colletotrichum acutatum. Tanaka et al. (2017) detected significant inhibition of cucumber powdery mildew by B. amyloliquefaciens SD-32. Chien and Huang (2020) showed that foliar sprays of B. amyloliquefaciens and Trichoderma asperellum significantly enhanced the biocontrol of bacterial spot disease in tomato. Suspension of Bacillus spp. strain DR-08, SC, was effective in controlling tomato brucellosis (Seong et al., 2020). Zheng et al. (2018) found that the inhibitory protein produced by B. subtilis Zl-2 could deform the mycelial morphology of Fusarium graminearum and inhibit its spore germination. In this study, all the five bacterial strains tested produce protease, cellulase and amylase, indicating that the strains could degrade fungal cell walls, destroy fungal cells and inhibit the growth of pathogenic mycelia so as to achieve the purpose of controlling pathogenetic infection. It was observed that strains Z-14 and JY214 changed the morphology of mycelia of Ggt, but whether they affected the internal organelles required to be further examined by transmission electron microscopy.

At present, the reports on biological control of diseases focus mainly on single biocontrol strain. Predictably, however, preparations made from single strains have solely antibacterial mechanisms and are susceptible to a variety of biotic and abiotic factors, which makes it difficult to give full play to its antibacterial effect and potential biocontrol function. Compound biocontrol agents can achieve the advantages of complementation among multiple strains, enhance the natural competitiveness and viability, improve the effect and stability of disease control, and inhibit better the growth of pathogenic bacteria through the synergistic effect of a variety of antibacterial mechanisms (Xu et al., 2010). The combination of B. subtilis EPCO16 and EPC5 with Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf1 was more effective in controlling disease caused by Fusarium solani than by themselves alone (Sundaramoorthy et al., 2012). Yu et al. (2015) compounded B. subtilis B41 and Pseudomonas putida B57 to control black shank disease in tobacco and achieved 75.72% control efficiency in greenhouse experiment and 67.99% control efficiency in the field experiment. The control efficiency was higher than that produced by using single strains. In the present study, application of Z-14 and JY214 alone and a combination of the two was effective in controlling take-all disease. The individual and combined use of Z-14 and JY214 did not produce differences in disease control effects, probably because of the high level of inhibition of Ggt produced by Z-14 and JY214 alone, and the advantage of the combination of the two strains was not uncovered under such experimental conditions.

Certain Bacillus spp. are capable of inducing resistance in plants and improving their resistance to diseases and stresses (Zhang et al., 2014b; Tang et al., 2016). Although not numerous, the use of bacterial strains with biocontrol effects in combination with pesticides (or resistance inducers) have been reported. The combination of Trichoderma with resistance inducers provided control of cotton root rot (Abo-Elyousr et al., 2009), and the combination of four strains of plant growth-promoting inter-rhizobacteria and hymexazol was more effective in plant growth promotion and control of Fusarium crown and root rot in tomato (Myresiotis et al., 2012). Our findings that the combined application of B. subtilis strains and pesticides can be more effective in controlling plant diseases are consistent with these reports.

Commercialization and large-scale application of some microorganisms with biocontrol effects are being achieved. For example, Bacillus strain QST-713 (SerenadeTM) promotes the growth of tomato plants and protects them from salt stress and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici attack (Medeiros and Bettiol, 2021). In greenhouse and field experiments, the application of the commercial biocontrol treatment Stargus (with the active ingredient B. amyloliquefaciens F727) was effective in controlling the severity of crown and root rot induced by Phytopythium vexans infesting ginkgo and red maple plants (Panth et al., 2021). It is foreseeable that the strains demonstrated in this study and their combinations with pesticides are promising for certain applications.

Conclusion

In this study, it was revealed that two B. subtilis strains, Z-14 and JY214, function to inhibit the growth of Ggt. Z-14 and JY214 not only produce secretions with protease, amylase and cellulase activities, but also promote wheat growth. The combination of Z-14 and JY214 allows for the control of wheat take-all disease in the field with a reduction in the use of the pesticide Koras. The reported solution mitigates the risk of potential environmental damage from the pesticide and reduces the adverse effect of the disease on wheat yield.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

DW and SH supervised the project. CH and DZ conceived and designed the experiments. GZ, ZZ, JZ, and YB performed the experiments and analyzed the data. GZ and TS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The take-all pathogen G. graminis var. tritici was kindly provided by Kejian Ding of College of Plant Protection, Agricultural University of Anhui, China. Bacillus subtilis strain Z-14 was a gift from DZ, College of Life Sciences, Hebei Agricultural University. We would like to thank our colleagues in the laboratory for their help with this study.

Funding Statement

The sources of funding for this study were provided by Hebei Provincial Department of Science and Technology through the projects: Local Science and Technology Development Fund Projects of Hebei Province Guided by the Central Government (206Z6502G), DW; Hebei Key R&D Program Project (21326509D), CH. The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abo-Elyousr K., Hashem M., Ali E. H. (2009). Integrated control of cotton root rot disease by mixing fungal biocontrol agents and resistance inducers. Crop Protect. 28, 295–301. 10.1016/j.cropro.2008.11.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinska M. S., Kalwasińska A., Witczak J., Ero K., Jankiewicz U. (2020). Exploring the properties of chitinolytic Bacillus isolates for the pathogens biological control. Microb. Pathog. 148, 104462. 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. H., Lee P. C., Huang T. P. (2021). Biological control of collar rot on passion fruits via induction of apoptosis in the collar rot pathogen by Bacillus subtilis. Phytopathology 111, 627–638. 10.1094/PHYTO-02-20-0044-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien Y. C., Huang C. H. (2020). Biocontrol of bacterial spot on tomato by foliar spray and growth medium application of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and Trichoderma asperellum. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 156, 995–1003. 10.1007/s10658-020-01947-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fira D., Dimkić I., Berić T., Lozo J., Stanković S. (2018). Biological control of plant pathogens by Bacillus species. J. Biotechnol. 285, 44–55. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J., Ward E. (2004). Gaeumannomyces graminis, the take-all fungus and its relatives. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5, 235–252. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H. N., Ding T. (2016). Biocontrol effect of endophytic fungus HPFJ3 from Magnolia officinalis on wheat take-all disease. Jiangsu J. Agri. Sci. 32, 285–292. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-4440.2016.02.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R., Macleod J., Foley W., Nayudu M. (2006). Gluconic acid: an antifungal agent produced by Pseudomonas species in biological control of take-all. Phytochemistry 67, 595–604. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X. J., Gan L., Liu J. H., Ji Y. Y., Wang Y., Zong Z. F. (2015). Effects of SC11 combined with other biocontrol agents on disease control and growth promotion in watermelon and eggplant. Acta Agri. Boreali-occidentalis Sin. 24, 117–124. 10.7606/j.issn.1004-1389.2015.12.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C., Tsai C. H., Chen P. Y., Wu C. Y., Chang Y. L., Yang Y. L., et al. (2018). Biological control of potato common scab by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Ba01. PLoS ONE 13, e0196520. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Q., Chen H. K., Kong L. Q. (2010). Separation and mutagenesis of alpha-amylase producing Bacillus. Anim. Husband. Feed Sci. 31, 1–4. 10.16003/j.cnki.issn1672-5190.2010.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros C., Bettiol W. (2021). Multifaceted intervention of Bacillus spp. against salinity stress and Fusarium wilt in tomato. J. Appl. Microbiol. 131, 2387–2401. 10.1111/jam.15095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myo M. E., Liu B., Ma J., Shi L., Jiang M., Zhang K., et al. (2019). Evaluation of Bacillus velezensis NKG-2 for bio-control activities against fungal diseases and potential plant growth. Biol. Control 134, 23–31. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.03.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myresiotis C. K., Karaoglanidis G. S., Vryzas Z., Papadopoulou-Mourkidou E. (2012). Evaluation of plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria, acibenzolar-S-methyl and hymexazol for integrated control of Fusarium crown and root rot on tomato. Pest Manag. 68, 404–411. 10.1002/ps.2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma-Guerrero J., Chancellor T., Spong J., Canning G., Hammond J., McMillan V. E., et al. (2021). Take-all disease: New insights into an important wheat root pathogen. Trends Plant Sci. 26, 836–848. 10.1016/j.tplants.2021.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panth M., Gurel F. B., Avin F. A., Simmons T. (2021). Identification, chemical and biological management of Phytopythium vexans, the causal agent of phytopythium root and crown rot of woody ornamentals. Plant Dis. 105, 1091–1100. 10.1094/PDIS-05-20-0987-RE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H. P., Huang L. L., Wang W. W., Gao X. N., Kang Z. S. (2005). Isolation and screening actinomycetes against take-all disease of wheat. J. Northw. A F Univ. 33, 1–4. 10.13207/j.cnki.jnwafu.2005.s1.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero D., Vicente A., de Olmos J. L., Dávila J. C., Pérez-García A. (2007). Effect of lipopeptides of antagonistic strains of Bacillus subtilis on the morphology and ultrastructure of the cucurbit fungal pathogen Podosphaera fusca. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103, 969–976. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03323.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saritha M., Arora A., Nain L. (2012). Pretreatment of paddy straw with Trametes hirsuta for improved enzymatic saccharifification. Bioresour. Technol. 104, 459–465. 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong M. I., Nan H. Y., Hee W. J., Soon O. K., Hae W. P., Ae R. P., et al. (2020). Biological control of tomato bacterial wilt by oxydifficidin and difficidin-producing Bacillus methylotrophicus DR-08. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 163, 130–137. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shewry P. R., Hey S. J. (2015). The contribution of wheat to human diet and health. Food Energy Secur. 4, 178–202. 10.1002/fes3.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. Z., Zeng H. M., Li G. Q. (2003). Effects of antibiotics on pathogenic microbe. J. Microbiol. 23, 44–47. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-7021.2003.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Yang L. M., Han M., Han Z. M., Yang L., Cheng L., et al. (2019). Biological control ginseng grey mold and plant colonization by antagonistic bacteria isolated from rhizospheric soil of Panax ginseng Meyer. Biol. Control 138, 104048. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaramoorthy S., Raguchander T., Ragupathi N., Samiyappan R. (2012). Combinatorial effect of endophytic and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria against wilt disease of Capsicum annum L. caused by Fusarium solani. Biol. Control 60, 59–67. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2011.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Fukuda M., Amaki Y., Sakaguchi T., Inai K., Ishihara A., et al. (2017). Importance of prumycin produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SD-32 in biocontrol against cucumber powdery mildew disease. Pest. Manag. Sci. 73, 2419–2428. 10.1002/ps.4630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Liang Y. Q., Xu P. D., Zhang C. C., Wu W. H., Zheng X. L., et al. (2016). Induction of resistance-related defensive enzymes in Heve a brasiliensis by Bacillus subtilis Czk1. J. Southern Agri. 47, 576–582. 10.3969/j:issn.2095-1191.2016.04.576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao T., Sun B. B., Shi H. W., Gao T. T., He Y. H., Li Y., et al. (2021). Sucrose triggers a novel signaling cascade promoting Bacillus subtilis rhizosphere colonization. ISME J. 15, 2723–2737. 10.1038/s41396-021-00966-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G. W., Chen D. Y., Yang X. (2008). Application of Gram stain three-stepmethod to Microbiology experiment teaching. Anhui Agri. Sci. Bullet. 14, 58–66. 10.16377/j.cnki.issn1007-7731.2008.15.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tokpah P. D., Li H. W., Wang L. Y., Liu X. Y., Mulbah S. Q., Liu H. X. (2016). An assessment system for screening effective bacteria as biological control agents against Magnaporthe grisea on rice. Biol. Control 103, 21–29. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vera Palma C. A., Madariaga Burrows B. P., González M. G., Gamboa B. R., Moya-Elizondo E. A. (2019). Integration between Pseudomonas protegens strains and fluquinconazole for the control of take-all in wheat. Crop Protect. 121, 163–172. 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.03.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Shen C. M., Zheng L., Xue Q. Y., Guo J. H. (2014b). Isolation and screening of antagonistic bacterial strains and their biocontrol efficiency against bacterial wilt. Plant Protect. 40, 43–69. 10.3969/j.issn.0529-1542.2014.02.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Wang C. W., Zuo B., Liang X. Y., Zhang D. N., Liu R. X., et al. (2021). A novel biocontrol strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FS6 for excellent control of gray mold and seedling diseases of ginseng. Plant Dis. 105, 1926–1935. 10.1094/PDIS-07-20-1593-RE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Yuan Z., Shi Y., Wang Y. (2020). Bacillus amyloliquefaciens HG01 induces resistance in loquats against anthracnose rot caused by Colletotrichum acutatum. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 160, 111034. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2019.111034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhang D. N., Wang C. W., Chen X., Yang L. N., Lu B. H., et al. (2019). Colonization and induced resistance of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FS6 in ginseng. J. Northw. A F Univ. 47, 125–138. 10.13207/j.cnki.jnwafu.2019.07.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhou D. M., Guo J. H. (2014a). Disease preventing and growth promoting mechanisms of Bacillus cereus strain AR156 on pepper. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 44, 195–203. 10.13926/j.cnki.apps.2014.02.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Zhao Y. R., Ni K. K., Shi Y., Xu Q. F. (2020). Characterization of ligninolytic bacteria and analysis of alkali-lignin biodegradation products. Pol. J. Microbiol. 69, 339–347. 10.33073/pjm-2020-037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. M., Robinson J., Jeger M., Jeffries P. (2010). Using combinations of biocontrol agents to control Botrytis cinerea on strawberry leaves under fluctuating temperatures. Biocontr. Sci. Technol. 20, 359–373. 10.1080/09583150903528114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. H., Liu H. X., Zhu G. M., Pan Y. L., Xu L. P., Guo J. H. (2008). Diversity analysis of antagonists from rice-associated bacteria and their application in biocontrol of rice diseases. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104, 91–104. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03534.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Han X., Zhang F., Goodwin P. H., Yang Y., Li J., et al. (2018). Screening Bacillus species as biological control agents of Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici on wheat. Biol. Contr. 118, 1–9. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2017.11.00428977681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M. M., Mavrodi D. V., Mavrodi O. V., Bonsall R. F., Parejko J. A., Paulitz T. C., et al. (2011). Biological control of take-all by fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. from Chinese wheat fields. Phytopathology 101, 1481–1491. 10.1094/PHYTO-04-11-0096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. J. (2019). Components of rhizospheric bacterial communities of barley and their potential for plant growth promotion and biocontrol of Fusarium wilt of watermelon. Braz. J. Microbiol. 50, 749–757. 10.1007/s42770-019-00089-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. J. (2017). Discussion on symptoms and prevention methods of wheat take-all. J. Agri. Catastrophol. 7, 1–3. 10.19383/j.cnki.nyzhyj.2017.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. P., Luo D. Q., Dai Y. F., Xu C. T., Chen X. (2015). Effects of compound biocontrol strains against tobacco black shank disease. Chin. Agri. Sci. Bullet. 31, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. Y., Wang W. W., Xue M., Liu Z., Zhang Q. M., Hou J. M., et al. (2021a). The combination of a biocontrol agent Trichoderma asperellum SC012 and hymexazol reduces the effective fungicide dose to control Fusarium wilt in cowpea. J. Fungi 7, 685. 10.3390/jof7090685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Yang L. R., Xue B. G., Quan X., Wu K. (2014a). Screening and identification of antagonistic strain FY1 against Gaeumannomyces graminis. J. Henan Agri. Sci. 43, 88–92. 10.15933/j.cnki.1004-3268.2014.05.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. M., Jiang W., Meng L. Q., Li J., Cao X., Chen J. Y., et al. (2014b). Induced resistance of tomato to grey mould by antifungai endophytic bacterium TF28. J. Anhui Agri. Sci. 42, 3253–3256. 10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2014.11.044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. J., Xie T. Z., Chen M. D., Wang Y. R., Shen H. S., He M. H., et al. (2022). Biocontrol effect of rhizosphere bacteria LK2-3 against Fusarium wilt of cucumber. China Cucurbit. Vegetabl. 35, 25–30. 10.16861/j.cnki.zggc.2022.017723878960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. C., Chen X. M., Qiao X. L., Fan X. R., Huo X. Y., Zhang D. D. (2021b). Isolation and yield optimization of lipopeptides from Bacillus subtilis Z-14 active against wheat take-all caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici. J. Sep. Sci. 44, 931–940. 10.1002/jssc.201901274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. C., Shah A. M., Mohamed H., Tsiklauri N., Song Y. D. (2021c). Isolation and screening of microorganisms for the effective pretreatment of lignocellulosic agricultural wastes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 5514745. 10.1155/2021/5514745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X. L., Dong C., Niu R. Y., Qi X. Y., Sun C., Wang X. X., et al. (2018). Characterization and inhibition effects of antifungal protein from Bacillus subtilis Zl-2. J. Nat. Sci. Heilongjiang Univ. 35, 206–211. 10.13482/j.issn1001-7011.2018.04.110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.