Abstract

Peritoneal metastasis is the leading cause of death for gastrointestinal cancers. The native and therapy-induced ascites ecosystems are not fully understood. Here, we characterize single-cell transcriptomes of 191,987 ascites cancer/immune cells from 35 patients with/without gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis (GCPM). During GCPM progression, an increase is seen of monocyte-like dendritic cells (DCs) that are pro-angiogenic with reduced antigen-presenting capacity and correlate with poor gastric cancer (GC) prognosis. We also describe the evolution of monocyte-like DCs and regulatory and proliferative T cells following therapy. Moreover, we track GC evolution, identifying high-plasticity GC clusters that exhibit a propensity to shift to a high-proliferative phenotype. Transitions occur via the recently described, autophagy-dependent plasticity program, paligenosis. Two autophagy-related genes (MARCKS and TXNIP) mark high-plasticity GC with poorer prognosis, and autophagy inhibitors induce apoptosis in patient-derived organoids. Our findings provide insights into the developmental trajectories of cancer/immune cells underlying GCPM progression and therapy resistance.

Subject terms: Gastric cancer, Cancer microenvironment, Cancer microenvironment

Peritoneal metastasis is one of the most common forms of death for gastrointestinal cancers, however, its cell composition is incompletely understood. Here, the authors use single cell RNA-seq of peritoneal metastases from 35 patients and show diversity in immune cells, and plasticity in cancer cell phenotypes and autophagy related genes as biomarkers of prognosis.

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most-diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide1. Gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis (GCPM) is common after curative surgical resection and portends a poor prognosis of <6 months overall survival2–4. GC patients diagnosed with GCPM during the perioperative stage experience only limited benefits from anti-tumor therapy strategies5–8. The molecular mechanisms of GCPM occurrence and development remain poorly understood. Therefore, an in-depth and dynamic exploration of GCPM occurrence and development can help us elucidate mechanisms involved in GCPM molecular pathology and find more effective therapeutic targets for GCPM.

GCPM occurs when GC cells selectively find a suitable ecosystem for growth in the peritoneum9–11. The peritoneal ecosystem is highly complex, including distinct heterogeneous immune cell populations12,13. Both peritoneal exfoliated tumor cells (PETCs) and immune cells in the abdominal cavity undergo diverse changes during GCPM development, and anti-tumor therapy might lead to a therapy-induced evolution of GCPM cells, in turn affecting their sensitivity to therapy14–16. Comprehensive dissection of the characteristics of peritoneal infiltrating immune cells and PETCs with single-cell resolution is necessary to better understand the underlying molecular mechanisms of GCPM and provide insights into future therapy strategies. Several recent studies dissected intratumoral heterogeneity and lineage diversity in primary GC and peritoneal metastatic foci17,18. However, the dynamic heterogeneity of the peritoneal ecosystem in early GCPM, the most promising clinical intervention stage, and the therapy-induced evolution of cells within this ecosystem, especially immune checkpoint evolution, remain enigmatic.

In this study, we characterized a total of 191,987 high-quality cells from 35 patients across five groups relative to GCPM development and treatment status. We assessed the diversity and heterogeneity of cells in the peritoneal ecosystem and observed proportionally reduced dendritic cells (DCs) and increased regulatory CD4 T cells (Treg) and naïve T cells during GCPM evolution. Notably, monocyte-like DCs exhibited high diversity and pro-angiogenic phenotypes, with reduced antigen-presenting capacity and increased pro-angiogenic capacity. We describe a proliferative cycling T cell cluster in the peritoneal ecosystem which represents an exhausted and dysfunctional stage of T cells comprising three heterogeneous sub-clusters. Peritoneal infiltrating monocyte-like DCs and cycling T cells exhibited marked evolution of heterogeneity after therapy, involving cell fate transition, immune phenotype changes, and metabolic reprograming. For GC cells, high-plasticity GC cells were marked by a propensity to evolve after therapy into high-proliferative GC cells. The plasticity transition from quiescent to proliferative states resembled the recently described plasticity process called paligenosis. Paligenosis was originally defined as the program by which differentiated (mitotically quiescent) cells use autophagy and dynamic mTORC1 regulation to reprogram into dividing cells in precancerous lesions like metaplasia19. This process has been proposed that if GC arises from metaplasia that arose via paligenosis, then perhaps GC cells may use paligenosis to survive20. Accordingly, we show here that two autophagy-related genes (MARCKS and TXNIP) were identified as biomarkers of high-plasticity GC. Furthermore, autophagy and mTORC1 inhibitors (known to block paligenosis) significantly induced apoptosis in patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from ascites samples. Our large-scale single-cell dataset provides a direction for future research on the molecular mechanisms of GCPM and will help design effective therapy strategies for GCPM in the future.

Results

Dynamic changes in the cellular ecosystem in ascites or peritoneal lavage fluid from GC patients

We obtained scRNA-seq transcriptomic profiles of cells from the peritoneal ecosystem from 35 patients across four medical centers, including normal peritoneal lavage fluid from four benign hysteromyoma patients (normal negative controls, G0 Group), peritoneal lavage fluid from four early GC patients (G1 Group); peritoneal lavage fluid from 10 advanced GC patients (G2 Group); ascites from 12 untreated advanced GC patients with diagnosed GCPM (G3 Group); and ascites from five advanced GC patients with diagnosed GCPM following systemic therapy (G4 Group) (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). We additionally collected four ascites samples from untreated advanced GC patients with diagnosed GCPM to culture ascites PDOs for experimental validation based on inhibitor drug intervention experiments and immunofluorescence assays (Fig. 1b and Methods).

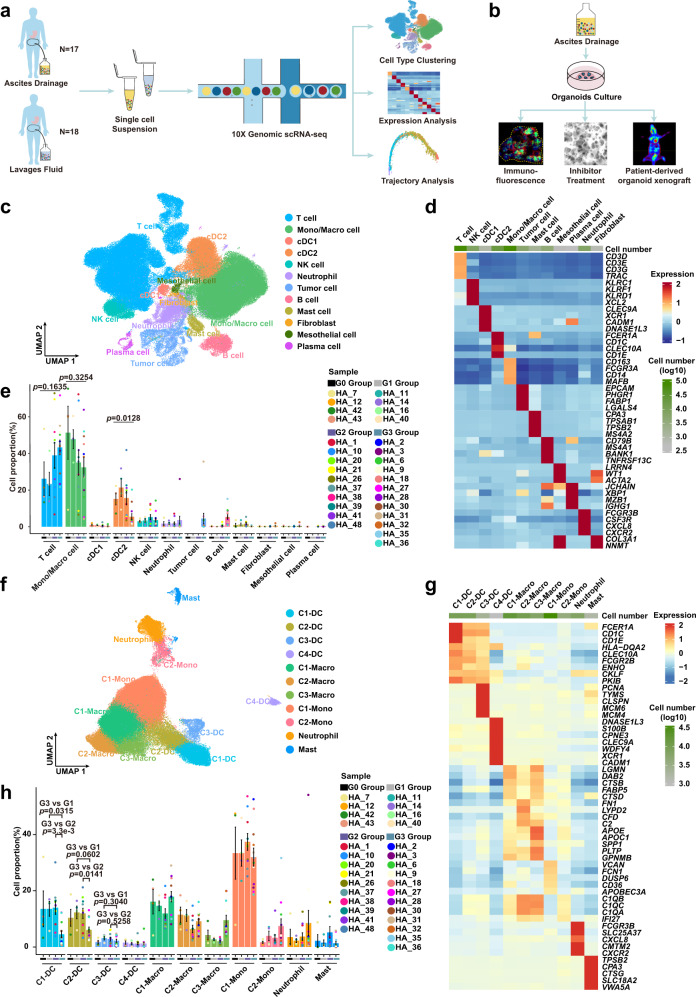

Fig. 1. scRNA-seq profiles of dynamic changes in the peritoneal ecosystem.

a Scheme of the experimental design and analytical workflow of this study for scRNA-seq. b Validation experiment based on patient-derived organoids from ascites. c Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot showing the main cell types from all samples. Each cluster is colored and annotated according to cell type. Mono/Macro, monocyte/macrophage; cDC1, type 1 conventional dendritic cells; cDC2, type 2 conventional dendritic cells. d Heatmap showing z-score normalized mean expression of selected marker genes in each cell type. e The proportion of each cell type in different groups from G0 (n = 4 samples), G1 (n = 4 samples), G2 (n = 10 samples) and G3 (n = 12 samples) Group. Histogram colors correspond to cell type colors in c; point colors correspond to samples. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars); the p-values are calculated by one-way ANOVA test. f UMAP plot representing myeloid cell clusters colored by cluster. DC dendritic cell, Macro macrophage, Mono monocyte. g Heatmap showing z-score normalized mean expression of selected genes in each cluster of myeloid cells. h The proportion of each cluster of myeloid cells from G0 (n = 4 samples), G1 (n = 4 samples), G2 (n = 10 samples) and G3 (n = 12 samples) Groups. Histogram colors correspond to cell type colors in f; point colors correspond to samples. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars); the p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To ensure that the filtered scRNA-seq data for further downstream analysis were from single live cells, we used the harmony algorithm to integrate scRNA-seq data from samples from the five groups and applied strict quality control and cell filtering (Supplementary Table 2). A total of 191,987 high-quality cells including myeloid cells, lymphocytes, fibroblast cells, mesothelial cells, and tumor cells were ultimately obtained (Fig. 1c), with an average of 2,744 genes, 11,177 unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), and only about 6% mitochondrial genes per cell detected (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Table 2). We identified 12 major cell clusters including immune and non-immune cells using the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) method (Fig. 1c). All cells had high expression levels of housekeeping genes such as GAPDH, ACTB, B2M, and RPL11 (Supplementary Fig. 1c), verifying the quality and accuracy of single cells. Immune and non-immune cells were divided based on PTPRC expression (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Immune cells accounted for the majority of our analyzed cells from the peritoneal ecosystem, consistent with previous findings from peritoneal dialysis fluid13. We identified multiple immune cell types using the following markers: T cells (CD3D and CD3E), NK cells (KLRC1 and KLRF1), type 1 conventional DCs (cDC1, CLEC9A and XCR1), type 2 conventional DCs (cDC2, CLEC10A and CD1C), macrophages/monocytes (CD163, FCGR3A and CD14), mast cells (CPA3 and TPSB2), B cells (CD79B and MS4A1), plasma cells (XBP1 and MZB1), and neutrophils (FCGR3B and CSF3R) (Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Fig. 1c). For non-immune cell populations, we identified tumor cells (EPCAM and CLDN4), fibroblasts (COL3A1 and NNMT), and mesothelial cells (LRRN4 and WT1) (Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Fig. 1c). Inferring chromosomal copy number variations (inferCNV) including gain and loss of chromosomes based on transcriptome has been widely used to identify whether epithelial cells are malignant tumor cells across scRNA-seq studies21–24. Our results showed that all identified epithelial cells were confirmed as malignant tumor cells by inferCNV analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1e, f). Over twelve cell clusters exhibited distinct distributions during the GCPM progression, with macrophages/monocytes and T cells, which were the main cell composition in the peritoneal cavity, exhibiting decreasing and increasing trends, respectively (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1d). We next conducted ELISA assays to measure the concentrations of chemokines in the peritoneal cavity to explore their effects on recruitment of immune cells into the peritoneal cavity during GCPM progression. CXCL16, a chemokine which recruits T cells, was elevated during GCPM (p = 5.9e-5), consistent with the change in the proportion of T cells, while the concentrations of chemokines that recruit macrophages/monocytes displayed complex changes (Supplementary Fig. 1g)25–27. The concentration of CCL5 (p = 0.0004) was reduced, but CCL2 (p = 1.6e-5), CCL3 (p = 0.0125) and CCL4 (p = 0.0051) were increased during GCPM progression (Supplementary Fig. 1g). The inconsistent changes of the macrophages/monocytes proportions and monocyte-recruitment chemokines may be due to the fact that monocyte-recruitment chemokines can also simultaneously recruit other cells, such as T cells, NK cells, neutrophils, DCs and MDSCs, making the recruitment of monocytes simultaneously influenced by multiple cytokines25–27. The concentrations of chemokines found via ELISA were consistent with the changes of their transcripts in our scRNA-seq data (Supplementary Fig. 1h).

Monocyte-like dendritic cells exhibit high diversity and a pro-angiogenic phenotype during GCPM

We first analyzed the G0-G3 Group to explore the immune cell landscape and the dynamic changes in immune cells during GCPM. Myeloid cells dominate the immune cell population. The cDC2 cluster displayed obvious variation among different groups, and the proportion of these cells infiltrating into the peritoneal cavity decreased as GC progressed, specifically in patients with GCPM (p = 0.0128) (Fig. 1e). Macrophages/monocytes showed a decreasing trend without statistical significance (p = 0.3254) (Fig. 1e). To explore potential distinct functional roles of cell clusters, we performed further myeloid cell clustering. In total, 11 cell clusters were identified among myeloid lineages: four DC clusters, three macrophage clusters, two monocyte clusters, one neutrophil cluster, and one mast cell cluster (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1i).

DCs are the main regulators for initiating antigen-specific immune responses in tumor immunity. We observed distinct CLEC9A+/XCR1+ cDC1 and CLEC10A+/CD1C+ cDC2 clusters (Fig. 1g)28–30. Our C4-DC cluster, featuring high expression of CLEC9A and XCR1, was identified as cDC1, with a relatively low proportion (Fig. 1f,g,h). cDC2 cells were divided into three clusters (C1-DC, C2-DC and C3-DC) (Fig. 1f,g and Supplementary Fig. 2a), characterized by comparable expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-II and lower expression of MHC-I, consistent with previous reports of cDC1s and cDC2s mainly initiating CD8 and CD4 T cells responses, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2a)28,31,32. C2-DC and C3-DC clusters highly expressed CD14, CD163, FCN1, MAFB, S100A9, and FCGR1A, while CD1C and MHC-II levels were relatively lower; this gene expression profile classified those clusters as more monocytic (monocyte-like DCs)33,34 (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). C3-DC is a cDC2 cluster characterized by high MCM4, MCM6, and PCNA expression, with lower antigen-presenting capacity and higher pro-angiogenic capacity (characterized by SPP1, STAB1, and TYMP expression); thus, it seems to largely represent proliferating DCs35–38 (Figs. 1g, 2a and 2b). We next examined the dynamic change of myeloid cells during GCPM. C1-DC and C2-DC proportions decreased in the G3 Group compared to the G1-G2 Groups (C1-DC, G3 vs G1: p = 0.0315, G3 vs G2: p = 3.3e-3; C2-DC, G3 vs G1: p = 0.0602, G3 vs G2: p = 0.0141), whereas C3-DC proportions (G3 vs G1: p = 0.3040, G3 vs G2: p = 0.5258) did not obviously change (Fig. 1h), indicating that the proportion of cDC2 cells that are proliferating is not related to GC stage. The proportion of monocyte-like DCs in the cDC2 population was significantly higher in the G3 Group than in the G1-G2 Group (G3 vs G1: p = 0.0038, G3 vs G2: p = 0.0021, Supplementary Fig. 2c). We performed FACS on ascites and peritoneal lavage fluids, and the results validated the existence of both cDC2 and monocyte-like DCs in the peritoneal cavity (Supplementary Fig. 2d). FACS also showed that the proportion of cDC2 cells decreased in ascites (p = 0.0355) and the proportion of monocyte-like DCs in cDC2 was higher in ascites than in peritoneal lavage fluids (p = 0.0195) (Supplementary Fig. 2e), consistent with our scRNA-seq data. Interestingly, monocyte-like DCs sorted by FACS from ascites showed significant upregulation of transcripts encoding cytokines that can recruit monocytes, including CCL2, CCL3, CCL4 and IL1B (CCL2: p = 0.0022; CCL3: p = 0.0205; CCL4: p = 0.0487; IL1B: p = 0.0466) (Supplementary Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2. Monocyte-like dendritic cells exhibit high diversity and a pro-angiogenic phenotype during GCPM.

a Dotplot showing antigen-presenting, pro-angiogenic, phagocytotic, pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and proliferative function scores of myeloid-derived cell clusters in G0-G3 Groups. Dot size represents percent of expressing cells in each cluster, color represents z-score of normalized mean expression level of selected gene signatures. DC dendritic cell, Macro macrophage, Mono monocyte. b Violin plot showing expression levels of selected antigen-presenting and pro-angiogenic genes in dendritic cell (DC) clusters among G0 (n = 4 samples), G1 (n = 4 samples), G2 (n = 10 samples) and G3 (n = 12 samples) Group, color-coded by cell type. Horizontal dotted line represents mean value, and colored dotted curve line indicates changes in expression level of selected genes. Box represents median ± interquartile range; whiskers represent 1.5x interquartile range; p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test. c Developmental trajectory plot of dendritic cell (DC) clusters, color-coded by cluster (left) and pseudotime (right). Each dot represents a single cell. d Curve plots showing metabolism score changes related to glycolysis, fatty acid metabolism, and oxidative phosphorylation in dendritic cells (DCs) along pseudotime. Point colors correspond to cell type colors in c. e The cell distribution of each dendritic cell (DC) cluster along with the pseudotime (upper panel), color-coded by DC clusters. Heatmap showing dynamic expression changes of genes in DC clusters (lower panel). f Curve plots showing expression level changes of function-related genes related to antigen-presentation, pro-angiogenesis, proliferation, plasticity, and immune checkpoint along pseudotime in dendritic cells (DCs). Point colors correspond to cell type colors in c. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Function scores were applied to explore functional changes in each DC type during GCPM. C1-DC and C4-DC clusters exhibited the highest antigen-presenting capacity among DCs, with no obvious antigen-presenting capacity change in G3 Group, whereas the C2-DC and C3-DC clusters (monocyte-like DCs) exhibited obviously reduced antigen-presenting function score and functional molecule expression in the G3 Group compared to the other stages (Fig. 2a, b and Source Data). The C2-DC and C3-DC cluster showed an increased pro-angiogenic function score and functional molecule expression in the G3 Group during GCPM (Fig. 2a, b). We next explored the dynamic developmental of DCs using Monocle trajectory analysis (Methods). Cell lineage trajectory of DCs showed that the C1-DC and C4-DC clusters were at the origin of the pseudotime trajectory, with the C2-DC cluster at the middle and the C3-DC cluster, characterized by a monocyte-like phenotype, lower antigen-presenting capacity, and higher pro-angiogenic capacity, at the end of the pseudotime trajectory (Fig. 2c). The tumor ecosystem can affect metabolic activity and lead to immune cell dysfunction through metabolic reprogramming, ultimately driving an immunosuppressive, pro-angiogenic, and pro-tumoral phenotype39–41. Therefore, we examined metabolic reprogramming in DCs, observing that glycolysis and fatty acid metabolism gradually increased along the differentiation trajectory toward the monocyte-like phenotype, whereas oxidative phosphorylation increased in early and intermediate stages then slightly decreased upon late differentiation (Fig. 2d). We constructed a heatmap to explore dynamic expression changes of genes associated with cellular transitions. C3-DC upregulated mTORC1 activation and E2F signaling pathway-related genes, accompanied by enhanced glycolysis, fatty acid metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and cholesterol metabolism (Fig. 2e, f). Immune checkpoint signaling can promote tumor escape from immunosurveillance and regulate cellular metabolism41,42. Several immune checkpoint genes (HAVCR2, CD47, LGALS9, and CD276) were gradually upregulated along the DC differentiation trajectory, especially at the late stage, revealing that C3-DC might suppress tumor immunity (Fig. 2e, f). We performed survival analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas Stomach Adenocarcinoma Cohort (TCGA STAD) using the GEPIA2 tool (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index)43, and confirmed that the C3-DC cluster gene signature significantly associated with worse prognosis (p = 0.0066), making it a potentially useful indicator of adverse clinical outcomes in GCPM (Supplementary Fig. 2g).

We identified three macrophage clusters in the peritoneal ecosystem (Fig. 1f,g). We observed co-existence of M1 and M2 functional phenotypes, indicating their complex function, consistent with previous studies21,44,45 (Supplementary Fig. 2h). The C2-Macro cluster preferentially expressed myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) signature genes including FCN1 and S100A8. The C3-Macro cluster preferentially expressed APOE, and TREM2, resembling an immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophage phenotype (TAM-like macrophages)23,44,46 (Supplementary Fig. 2i,j). We used the TCGA STAD cohort to evaluate the association between the C3-Macro gene signature and prognosis, finding that patients with high C3-Macro gene signature tended to have poor prognosis although there was no statistical significance (median survival time: 24 months vs 60 months; p = 0.098, Supplementary Fig. 2k).

T cell inhibitory states are differentially remodeled in GCPM progression

NK cells and especially T cells are key cytotoxic immune cells involved in tumorigenesis and cancer metastasis47,48. We conducted unsupervised clustering of all T cells and NK cells, identifying 14 clusters: three CD4+ T cell clusters, six CD8+ T cell clusters, one proliferative T cell cluster, two NKT cell clusters, and two NK cell clusters (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 3a). We identified the C1-CD4 cluster as effector memory CD4 T cells (IL7R-positive and CCR7-negative) and the C2-CD4 cluster as naïve CD4 T cells (CCR7, SELL, and LEF1 positive). The C3-CD4 cluster, identified as regulatory CD4 T cells, highly expressed FOXP3, IL2RA, and IKZF2; co-stimulatory markers CD28, ICOS, and TNFRSF9; and inhibitory checkpoint genes CTLA4 and TIGIT (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3b-d). For CD8 T cells, the C1-CD8 cluster contained effector memory CD8 T cells (GZMK and DUSP2 positive); the C2-CD8 and C5-CD8 clusters were identified as terminally differentiated effector memory/effector CD8 T cells (GZMA, GZMH, GZMK, CCL4 and CCL5 positive); the C3-CD8 cluster was identified as mucosal-associated invariant T cells (SLC4A10 positive); the C4-CD8 cluster co-expressed tissue-resident gene markers (ITGA1, CD69, CXCR6, and CAPG) and was identified as tissue-resident memory T cells; and the cycling T cluster showed high-proliferative genes (MKI67, MCM2, PCNA, and STMN1) and tissue-resident marker genes (ITGAE, CD69, CXCR6, and CAPG) (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3d, e).

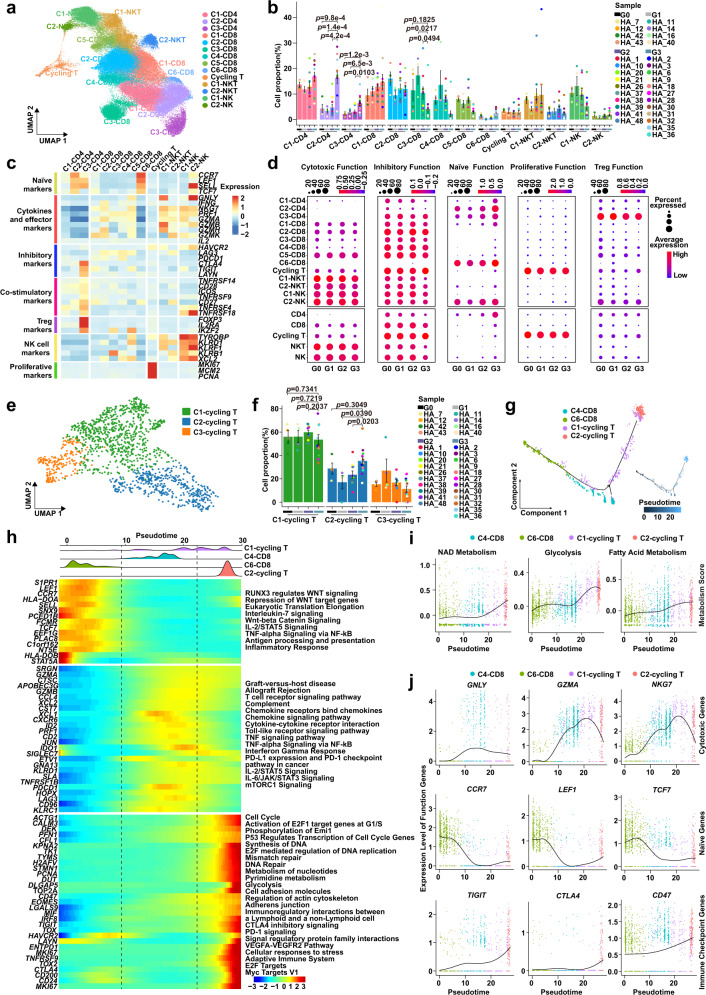

Fig. 3. T cell inhibitory states are differentially remodeled in GCPM progression.

a Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot representing clusters of T/NK cells, colored by cluster. b The proportion of T/NK cells clusters in different groups from G0 (n = 4 samples), G1 (n = 4 samples), G2 (n = 10 samples) and G3 (n = 12 samples) Groups. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars); p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. c Heatmap showing expression levels of selected genes of naïve, cytokines and effectors, inhibitory, co-stimulatory, Treg, NK cells, and proliferative markers in each T/NK cell cluster. d Dotplot showing the cytotoxic, inhibitory, naïve, proliferative, and Treg function scores of T/NK cells clusters in G0-G3 Groups. Dot size represents percent of expressing cells in each cluster and color represents z-score of normalized mean expression level of selected gene signatures. e Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot of three clusters of cycling T cells, colored by cell cluster. f Histogram plot indicating the cell proportions of cycling T clusters in G0 (n = 4 samples), G1 (n = 4 samples), G2 (n = 10 samples), and G3 (n = 12 samples) Groups. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars); the p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. g Developmental trajectory of cycling T cells inferred by Monocle 2 analysis, color-coded by cluster (left) and pseudotime (right). Each dot represents a single cell. h The distribution of cycling T cells is shown along pseudotime (upper panel), color-coded by T cell clusters. Heatmap showing dynamic expression changes of selected genes and related pathways along pseudotime (lower panel). i Curve plots showing dynamic changes of metabolism scores in cycling T cells along pseudotime. Point colors correspond to cell type colors in g. j Curve plots showing expression changes of function genes related to cytotoxic, naïve, and immune checkpoint genes in cycling T cells along pseudotime. Point colors correspond to cell type colors in g. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The proportion of C2-CD4 naïve and C3-CD4 Treg clusters increased dramatically and significantly in the G3 Group (C2-CD4, G3 vs G1: p = 1.4e-4, G3 vs G2: p = 4.2e-4; C3-CD4, G3 vs G1: p = 6.5e-3, G3 vs G2: p = 0.0103, Fig. 3b). Several well recognized inhibitory immune checkpoint genes such as HAVCR2, LAG3, PDCD1 and BTLA had no expression in most CD4 T cell clusters, whereas CTLA4 and TIGIT had moderate expression in C3-CD4 Treg cells (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3c, f). The C3-CD8 mucosal-associated invariant T cells are prevalent in several peripheral tissues and blood and are reported to kill tumor cells49,50. The C3-CD8 mucosal-associated invariant T cells cluster proportion decreased in the G3 Group compared to the G1 (p = 0.0217) and G2 Groups (p = 0.0494), and the cytotoxic function category was inhibited in early-stage disease (G1-G3 Group), demonstrating a rapid response to change in the peritoneal ecosystem51,52 (Fig. 3b-d).

We observed a proliferative cycling T cluster characterized by high MKI67, MCM2 and PCNA expression in the peritoneal ecosystem (Fig. 3a, c and Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). These cells exhibited low expression of cytotoxic (GNLY, IFNG, and PRF1) and naïve (CCR7 and SELL) genes and high expression of inhibitory markers (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3e). The cytotoxic function score and corresponding marker genes GZMA and GZMH were reduced in the G3 Group compared to the G0-G2 Groups (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3g). Therefore, the proliferative cycling T cluster may exhibit a dysfunctional status and resemble a naïve phenotype, consistent with previous reports21,53. Gene Set Enrichment Analyses (GSEA) indicated the cycling T cluster was enriched in genes involved in cell cycle, glycolysis, and DNA replication, likely preparing the materials and energy required for proliferation, and negatively enriched in cytotoxicity genes (Supplementary Fig. 3h).

We investigated the composition of the proliferative cycling T cell cluster and found that it comprised of heterogeneous cell clusters containing two CD8 cell clusters (C1-cycling T and C2-cycling T) and one NKT cell cluster (C3-cycling T) (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 3i). The C2-cycling T cell cluster proportion was increased in the G3 Group compared to the G1 (p = 0.0390) and G2 Groups (p = 0.0203) (Fig. 3f). Using Monocle trajectory analysis to explore the developmental trajectory of peritoneal cycling T cells, we found that the developmental trajectory started with the C6-CD8 naïve cluster, passed through the C4-CD8 and C1-cycling T cell clusters, then culminated in the C2-cycling T cell cluster (Fig. 3g,h). Metabolic transitions are essential for CD8 T cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and activation in anti-tumor immunity41,54. We observed that glycolysis, fatty acid metabolism, and NAD metabolism were obviously up-regulated alongside developmental trajectory, consistent with previous reports39,41,55 (Fig. 3g,i). Proliferative C2-cycling T cells highly expressed proliferative genes (MKI67, STMN1, and PCNA) and gained partial naïve function (CCR7, LEF1, TCF7 and CCR7), leading to reduced cytotoxic function (GNLY, GZMA, and NKG7) and increased inhibitory function (TIGIT, CD47, and CTLA4) (Fig. 3h,j). Therefore, the C2-cycling T cluster may represent an exhausted and dysfunctional stage, consistent with recent single-cell studies44,53,56.

Therapy-induced evolution of monocyte-like DC and cycling T cell immune phenotype

Cells of the tumor ecosystem can exhibit therapy-induced evolution of biological heterogeneity involving cell state transitions and cellular plasticity23,57,58. We observed that the C2-DC cluster decreased (p = 0.0161) following therapy (G4 Group; Fig. 4a). We next explored functional changes during therapy-induced evolution. Therapy caused C3-DC cells (shown earlier to be a late-stage population in GC) to gain proliferative and pro-angiogenic capacity, and their antigen-presenting capacity significantly decreased (Fig. 4b). Analysis with the “SCENIC” R package suggested that the C3-DC cluster had distinctive transcriptional factor (TF) activity between the G3 and G4 Groups, characterized by PPARG, MLX and CEBPA activation (Supplementary Fig. 4a). By comparing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of the C3-DC cluster between the G3 and G4 Groups, we confirmed that the C3-DC cluster in the G4 Group was characterized by high expression of genes involved in immunosuppression (APOE and GPNMB) and pro-angiogenesis (SPP1) (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Furthermore, C3-DC cells significantly upregulated inflammatory factors CCL2, CCL3 and CCL4 in the G4 Group, which may recruit inflammatory monocytes, monocyte-like DCs, neutrophils and TAM-like macrophages into the peritoneum through their corresponding receptors CCR1, CCR2, and CCR5, leading to a pro-angiogenic and immunosuppressive ecosystem59–61 (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c). GSEA analysis found that C3-DC cells in the G4 Group highly expressed genes involved in inflammatory response, NF-kappa B signaling, chemokine signaling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and Notch signaling (Fig. 4c). Conversely, C3-DC cells in the G3 Group highly expressed genes involved in antigen processing and presentation, MHC-II receptor activity, and T helper cell differentiation (Fig. 4c).

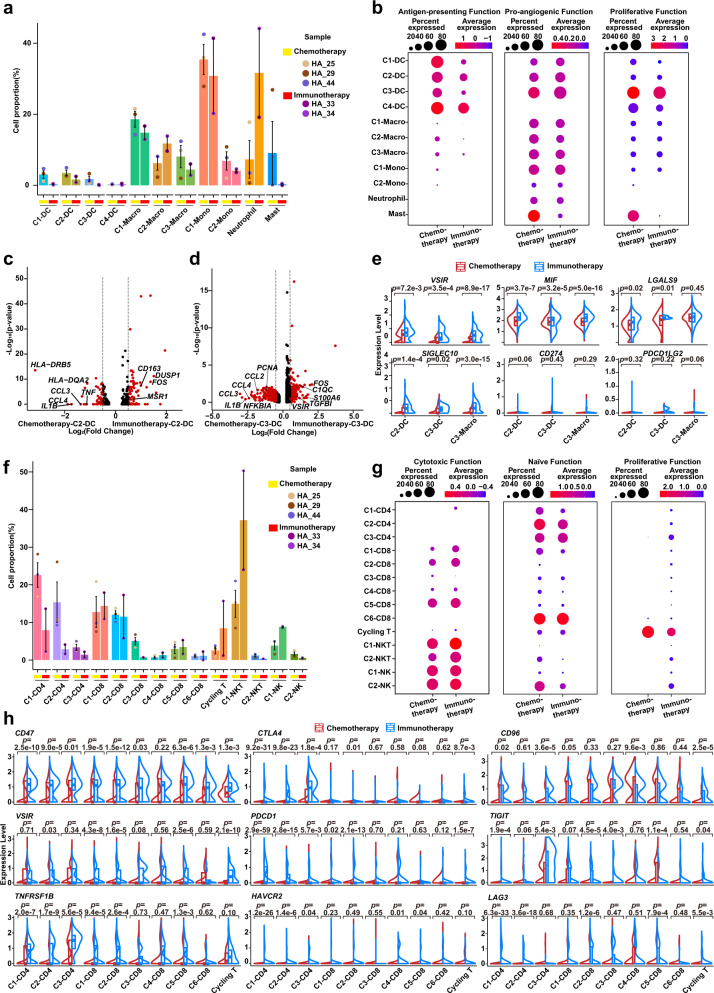

Fig. 4. Therapy-induced evolution of monocyte-like DC and cycling T cell immune phenotype.

a Histogram plot showing cell proportions of myeloid cell clusters in the G3 (n = 12 samples) and G4 Groups (n = 5 samples) colored by cell type. DC, dendritic cell; Macro, macrophage; Mono, monocyte. Point colors correspond to samples. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars); p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. b Split violin plots showing the antigen-presenting, pro-angiogenic, and proliferative function scores of myeloid cells in the G3 (n = 12 samples, red) and G4 Groups (n = 5 samples, blue) groups. Box represents median ± interquartile range; p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test. c Gene Set Enrichment Analyses (GSEA) analysis showing distinct enrichment pathways of C3-DC in the G3 (red) and G4 Groups (blue). Bar chart showing normalized enrichment scores (NES) of specific pathways. d Heatmap plot representing the activity of metabolism pathways of C2/C3-DCs in the G3 and G4 Groups. Color indicates the activity score of each metabolism pathway calculated by Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) analysis. e Histogram plot representing the cell proportion of T/NK clusters in the G3 (n = 12 samples) and G4 Groups (n = 5 samples), colored by cell type. Point colors correspond to samples. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars); p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test. f Split violin plots showing the cytotoxic, inhibitory, naïve, and proliferative function scores of T cells in the G3 (n = 12 samples, red) and G4 Groups (n = 5 samples, blue). Box represents median ± interquartile range; p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test. g Similar to d, the metabolism pathway activity score of C3-CD4 and cycling T cells in the G3 and G4 Groups shown in a heatmap plot. Pathway activity scores were calculated by Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) analysis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Cell state and function transitions are often accompanied by heterogenic metabolic patterns62–64. We used Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) to assess metabolic activity in monocyte-like DC clusters between the G3 and G4 Groups. The C3-DC cluster upregulated oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis after therapy, accompanied by hyaluronan metabolism and purine metabolism in the G4 Group (Fig. 4d). In contrast, the C2-DC cluster exhibited decreased mitochondrial function, characterized by downregulated oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid mitochondria oxidation and increased glycolysis and pyruvate metabolism (Fig. 4d). Systemic therapy significantly decreased the proportion of C3-CD4 Treg cells (p = 0.0060) that had increased during GCPM with a reduced inhibitory and naïve function, suggesting an improving immunosuppressive status (Fig. 4e, f). The cycling T cell cluster exhibited distinct TF activity in the G3 and G4 Groups, characterized by PPARG, ZBTB14, MLX, BATF, and CEBPA activation (Supplementary Fig. 4d). The cycling T cell cluster in the G4 Group had impaired adaptive immune function compared to the G3 Group, including a low expression of cytotoxic genes (NKG7, GZMA, GZMH, and PRF1) and MHC molecules (HLA-DRA, HLA-DPA1, and HLA-C) (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Notably, cycling T cells acquired higher plasticity (ALDH1A1, SOX9, and SOX4) and lower proliferation (STMN1) in the G4 Group (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Furthermore, function score analysis indicated that cycling T cells exhibited a reduced cytotoxic/proliferative function and an increased naïve function under anti-tumor therapy (G4 Group), suggesting that cycling T cell function may be silenced in response to the stress of therapy and that this transition may be a self-protection mechanism against antitumor drugs (Fig. 4f). The cycling T cell cluster also expressed genes associated with drug metabolism (MGST1, GSTP1, NME1 and NME2)65–67 (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Metabolism analysis indicated that cycling T cells undergo obvious metabolic reprogramming during therapy, with upregulated oxidative phosphorylation, citric acid cycle, and glutathione metabolism possibly associating with drug metabolism (Fig. 4g).

Immune checkpoint evolution of monocyte-like DCs and cycling T cells

Cancer immunotherapy can remodel the phenotype of immune cells infiltrating into solid tumors68, but its impact in the peritoneal ecosystem remains unclear. Therefore, we explored immune checkpoint evolution in immune cells by comparing ascites samples from immunotherapy (two patients) and chemotherapy (three patients) (Supplementary Table 1). We found inhibited overall antigen-presenting capacity for all myeloid cells but largely comparable pro-angiogenic capacity (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Specifically, C2-DC and C3-DC proportions decreased in immunotherapy compared to chemotherapy (Fig. 5a). In cell function analysis, the C2-DC cluster downregulated antigen-presenting capacity without significant changes to pro-angiogenic capacity, whereas the C3-DC cluster downregulated both antigen-presenting and pro-angiogenic capacities in immunotherapy (Fig. 5b). By comparing C2-DC DEGs between the immunotherapy and chemotherapy groups, we found C2-DC cells in the immunotherapy group had lower-expressed genes associated with MHC molecules (HLA-DRB5, HLA-DQA2) (Fig. 5c). Notably, C2-DC cells following immunotherapy were negatively enriched for pro-inflammatory phenotype (CCL4, IL1B, CCL3 and TNF), with high expression of anti-inflammatory associated genes (CD163 and MSR1) (Fig. 5c). Similarly, C3-DC and C3-Macro clusters exhibited an anti-inflammatory phenotype under immunotherapy, negatively enriching for the NF-kappa B pathway and pro-inflammatory phenotype, suggesting a widespread shift to an anti-inflammatory phenotype for monocyte-like DCs and TAM-like macrophages with lower CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, IL1B, TNF, and NFKBIA (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 5b,c). To better understand the role of these monocyte-like DCs in immunotherapy, we examined immune checkpoint expression patterns. CD274 (PD-L1) and PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2), the two ligands for the PD-1-related immune checkpoint, were rarely expressed in monocyte-like DCs and TAM-like macrophages. Other immune checkpoint genes such as VSIR, MIF, LGALS9, and SIGLEC10, which can induce T/NK cell immune checkpoints and subsequently inhibit their cytotoxicity69–72, were expressed in C2-DC and C3-DC clusters and increased in immunotherapy compared with chemotherapy (Fig. 5e).

Fig. 5. Immune checkpoint evolution of monocyte-like DC and cycling T cells.

a Cell proportions of myeloid cell clusters after Chemotherapy (n = 3 samples) and Immunotherapy (n = 2 samples) shown in histogram plot. DC, dendritic cell; Macro, macrophage; Mono, monocyte. Histogram colors correspond to cell clusters; point colors correspond to samples. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars). b Dotplot showing the antigen-presenting, pro-angiogenic, and proliferative function scores of myeloid cell clusters in Chemotherapy (n = 3 samples) and Immunotherapy (n = 2 samples) Groups. Dot size represents percent of expressing cells in each cluster, and color represents mean expression level of selected gene signatures. c, d Volcano plots showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of C2-DC (c) and C3-DC (d) between Chemotherapy (three patients) and Immunotherapy (two patients) Groups. e Split violin plots showing expression levels of immune checkpoints of C2/C3-DC and C3-Macro in Chemotherapy (n = 3 samples, red) and Immunotherapy (n = 2 samples, blue) Groups. The comparisons and statistical analyses are conducted between cell clusters (three cell clusters: C2-DC, C3-DC, and C3-Macro) of Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy groups, and the total cells number of all clusters are >3. Box represents median ± interquartile range; p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test. f The same histogram plot as in a for T/NK clusters in Chemotherapy (n = 3 samples) and Immunotherapy (n = 2 samples) Groups. Histogram colors correspond to cell clusters; point colors correspond to samples. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars). g Dotplot showing the cytotoxic, naïve, and proliferative function scores of T/NK cell types in Chemotherapy (three patients) and Immunotherapy (two patients) Groups. Dot size represents percent of expressing cells in each cluster, and color represents z-score of normalized mean expression level of selected gene signatures. h The same split violin plots as in (e) for T/NK cell types in Chemotherapy (n = 3 samples, red) and Immunotherapy (n = 2 samples, blue) Groups. The comparisons and statistical analyses are conducted between T cell clusters (10 cell clusters: C1-3 CD4, C1-6 CD8, and Cycling T) of Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy groups, and the total cells number of all clusters are >3. Box represents median ± interquartile range; p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next explored immune phenotype changes in peritoneal-infiltrating T cells during immunotherapy. C2-CD4 naïve and C3-CD4 Treg cluster proportions decreased in immunotherapy compared to chemotherapy (Fig. 5f), indicating that immunotherapy may reduce immunosuppressive T cell clusters. In addition, immunotherapy caused increased expression of co-stimulatory marker genes CD27, CD69, and TNFRSF14 (Supplementary Fig. 5d), consistent with a previous report73. Cell function analysis indicated that the percent of CD8 T cells with high cytotoxic function slightly increased, although the overall cytotoxic function score of CD8 T cells in immunotherapy was comparable to the chemotherapy group, and the naïve function score of CD4 T cells in the immunotherapy group decreased compared to the chemotherapy group (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Further function score analysis showed that immunotherapy did not obviously enhance T cell cytotoxicity, but could increase the percent of CD8 T cells with high cytotoxic function (Fig. 5g). However, immunotherapy significantly induced upregulation of several immune checkpoints. The C3-CD4 Treg cluster in the immunotherapy group preferentially expressed immune checkpoint genes CTLA4, TIGIT, CD47, CD96, and TNFRSF1B after immunotherapy, and VSIR, CD47, CD96, and TNFRSF1B were upregulated in the cycling T cluster after immunotherapy (Fig. 5h).

High-plasticity GC evolves to high-proliferative GC through a conserved cellular program

All epithelial cells were divided into 7 clusters. We observed that C1-3 tumor clusters were shared by almost all GC cases, while C4-7 tumor clusters were present only in a single case (Fig. 6a). We analyzed tumor characteristics such as proliferation, differentiation, and plasticity in clusters C1-3 and found that the C1-tumor cluster was highly differentiated, the C2-tumor cluster was highly plastic, and the C3-tumor cluster was highly proliferative (Fig. 6b). Recently a conserved program for cellular plasticity in epithelial cells was defined, termed paligenosis. Paligenosis occurs via 3 stages: Stage1, massive activation of autophagy and lysosomal activity as mTORC1 is extinguished; Stage2, re-expression of progenitor or embryonic markers without mTORC1 expression; Stage3, induction of high mTORC1 with cell cycle entry19,20,74–77, consistent with a previous study78. Previously, paligenosis has been shown as the process differentiated cells use to return to the progenitor state in precancerous states like gastric metaplasia. We reasoned that GC, which largely arises from metaplastic lesions, might maintain plasticity in response to therapy by continuing to use paligenosis. The C2-tumor cluster had high autophagy (ATG5, MAP1LC3B), high plasticity (SOX4, CD164) and low mTORC1 activity (RPS6, MLST8) (Supplementary Fig. 6a), characteristics of early paligenosis (stages 1-2). The early paligenosis markers DDIT4 and ATF3 were also upregulated (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The C3-tumor cluster had high mTORC1 activity (MLST8, RPS6) and high proliferation (MKI67, MCM2), characteristics of late paligenosis when cells re-enter the cell cycle (stage 3)74,76,77 (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 6a). We applied pseudotime trajectory analysis to the C1-3 tumor clusters and found a continuous developmental trajectory between the C2-tumor and C3-tumor clusters, while the C1-tumor had strong heterogeneity and hence seemed to follow a separate developmental mechanism, as they were evenly distributed along the trajectory (Supplementary Fig. 6b). C1-tumor cells may be akin to differentiated cells in a tissue prior to paligenosis, as C1-tumor cells have increased “Differentiation” and decreased “Proliferation” and “Plasticity” phenotypes.

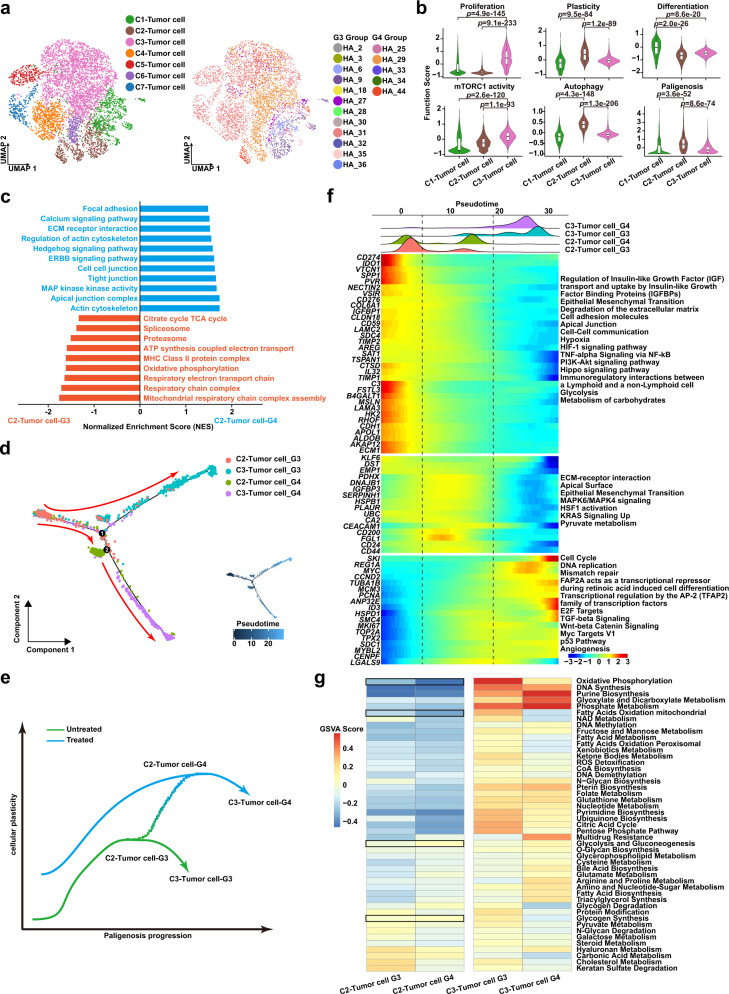

Fig. 6. High-plasticity GC evolves to high-proliferative GC through a conserved cellular program.

a Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) visualization of tumor cells by cell types (Left, colors correspond to cell clusters) and samples (Right, colors correspond to samples). b Violin plot showing function scores of proliferation, plasticity, differentiation, mTORC1, autophagy, and paligenosis in tumor cells (C1-Tumor cell: n = 713 cells; C2-Tumor cell: n = 549 cells; C3-Tumor cell: n = 2545 cells). Box represents median ± interquartile range; whiskers represent 1.5x interquartile range; p-values are calculated by two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test. c Gene Set Enrichment Analyses (GSEA) analysis showing distinct enrichment pathways of C2-Tumor cells in the G3 (red) and G4 Groups (blue). Bar chart showing the normalized enrichment score (NES) of specific pathways in specific tumor cells. d The trajectory plot of C2/C3-tumor cells in the G3 and G4 Groups (left), and the transition trajectories along pseudotime (right) in a two-dimensional state-space inferred by Monocle 2 analysis. e Two-dimensional schematic diagram showing cellular plasticity changes in C2/C3-tumor cells in the G3 and G4 Groups along paligenosis progression. f The 3-phase distribution of C2/C3-tumor cells along pseudotime color-coded by cell cluster (upper panel). Heatmap showing dynamic expression changes of genes and related pathways of C2/C3-tumor cells in the G3 and G4 Groups along pseudotime (lower panel). g Heatmap plot indicating the activity of metabolism pathways in C2/C3-tumor cells between the G3 and G4 Groups. Color represents the activity score of metabolism pathways calculated by Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) analysis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next analyzed therapy-induced evolution of GC cells during GCPM. In normal tissue, paligenosis of differentiated cell is induced by injury or inflammation that causes mature, mitotically quiescent cells to reprogram and reenter the cell cycle75,79. Thus, if paligenosis was the mechanism tumor cells were using to increase proliferation, we would expect therapy to induce reprogramming of tumor cell clusters. All clusters changed significantly following therapy, especially plasticity and paligenosis characteristics of the C2-tumor cluster (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). GSEA analysis confirmed that C2-tumor cluster plasticity was further enhanced after therapy (G4 Group) as characterized by Hedgehog, ERBB pathway activation, and cell polarization remodeling (Fig. 6c). In further trajectory analysis, we discovered that part of the C2-tumor cluster in the G3 Group develops into the C3-tumor cluster in the G3 Group, with the other part developing into the highly-plastic C2-tumor cluster in the G4 Group. At the terminal end of the cell trajectory, C2-tumor cells from the G4 Group lose some plasticity and gain proliferative ability and develop into the C3-tumor cluster from the G4 Group. The whole development trajectory is a continuous evolution of cell plasticity leading to proliferation (Fig. 6d–f). We analyzed expression changes of genes associated with cell transitions. In the middle of the trajectory where the C2-tumor-G4-Group cluster is enriched, cells were characterized by epithelial-mesenchymal transition, a program often seen in cells gaining plasticity and therapy resistance80–83 (Fig. 6f). At the end of cell trajectory, where the C3-tumor-G4-Group cluster is enriched, cells were characterized by cell cycle entry and Wnt pathway activation, demonstrating that C3-tumor cells in the G4 Group maintain considerable pluripotency while gaining proliferative ability (Fig. 6f). Both C2-tumor and C3-tumor clusters in the G4 Group showed metabolic reprograming and increased multi-drug resistance. C2-tumor cells in the G4 Group were further characterized by decreased mitochondrial function (oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid oxidation) and increased glycolysis and glycogen metabolism (Fig. 6g).

Autophagy inhibition blocks paligenosis and induces apoptosis in GC PDOs

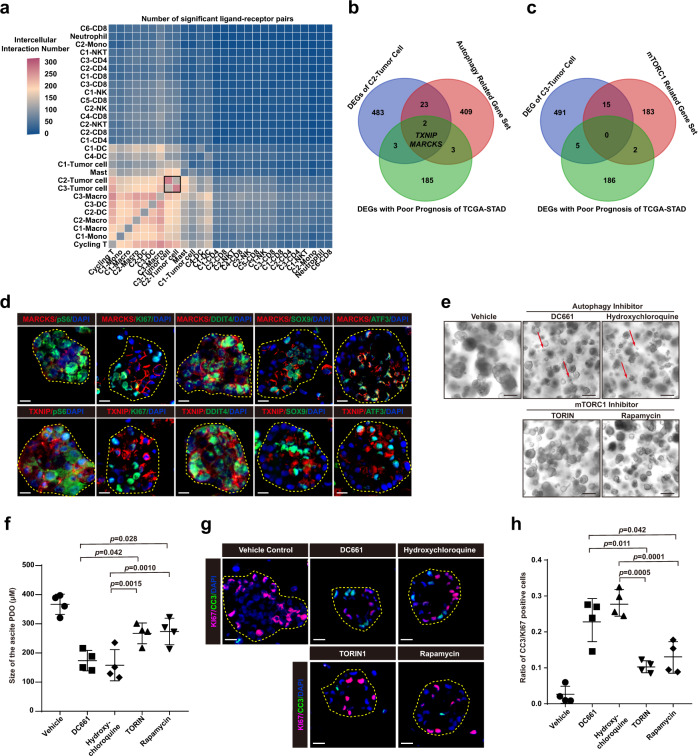

To further clarify cellular regulation during GCPM, we analyzed cell communication among all cell clusters in the peritoneal ecosystem. We found complex communication among GC and immune cells. Surprisingly, the strongest cell communication was between C2 and C3 tumor cells (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). To decode the molecular network regulating C2 and C3 tumor cells, we looked for intersections between DEGs of C2 tumor cells, autophagy-related genes, and genes related to GC patient prognosis in the TCGA STAD database. Only two transcripts, MARCKS (Myristoylated Alanine Rich Protein Kinase C Substrate) and TXNIP (Thioredoxin Interacting Protein) were present in all three gene sets in the C2 tumor cell cluster (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). No intersecting genes were discovered among C3 tumor cell DEGs, a published set of mTORC1-related genes, and genes related with GC patient prognosis in TCGA (Fig. 7c). PDOs comprise effective tools for genetic evolution studies, biomarker identification, and drug screening for cancer patients84–86. We cultured PDOs from ascites samples from four advanced GC patients with GCPM (Supplementary Table 3). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7e, GC PDOs maintained the growth patterns and differentiation of the primary GC. MARCKS and TXNIP protein expression did not correlate with expression of late (Stage 3) paligenosis markers pS6 and KI6719,77; however, they were co-expressed with early paligenosis markers DDIT4 and ATF3 as well as SOX9 (which is induced by Stage 2), indicating that MARCKS and TXNIP are enriched in early paligenosis74,76 (Fig. 7d). We treated ascites PDOs with autophagy or mTORC1 inhibitors, as autophagy induction and mTORC1 activation are hallmarks of early and late paligenosis, respectively, and both are required for cells undergoing paligenosis to eventually re-enter the cell cycle19,77. Both autophagy and mTORC1 inhibitors significantly decreased the growth of ascites PDOs as measured by organoid size (Fig. 7e, f). The autophagy inhibitors DC661 and hydroxychloroquine were more effective at inhibiting the growth of ascites PDOs compared with mTORC1 inhibitors TORIN1 and rapamycin (Fig. 7e, f). We discovered that only DC661 or hydroxychloroquine induced organoid death, indicating that autophagy and mTORC1 inhibitors hinder PDOs growth via different mechanisms (red arrow in Fig. 7e). This result was consistent with our previous studies that autophagy blockage causes cell death in paligenosis stages 1-2, whereas mTORC1 blockage simply inhibits cell cycle entry in paligenosis stage 319,77. To further analyze the features of organoid death upon treatment with autophagy and mTORC1 inhibitors, we stained PDOs treated with autophagy or mTORC1 inhibitors for CC3 (cleaved caspase3) and KI67. DC661 and hydroxychloroquine significantly induced the apoptosis of ascites PDOs, increasing the ratio of CC3/KI67 positive cells compared with untreated control and mTORC1 inhibitors treated PDOs, confirming that autophagy inhibition caused failed paligenosis and subsequently induce apoptosis (Fig. 7g,h).

Fig. 7. Autophagy inhibition blocks paligenosis and induces apoptosis in GC PDOs.

a Heatmap showing the intercellular interaction by CellPhoneDB analysis. Color represents the number of significant ligand-receptor pairs among different cell subtypes. DC, dendritic cell; Macro, macrophage; Mono, monocyte. b, c Venn diagram showing the number of overlapping signature genes between differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of C2-tumor cell, poor prognostic DEGs of The Cancer Genome Atlas Stomach Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-STAD) database, and autophagy-related gene sets (b) and mTORC1-related gene sets (c). d Immunofluorescence staining for MARCKS (red, upper panel) and TXNIP (red, lower panel), early paligenosis markers DDIT4 (green) and ATF3 (green), late paligenosis markers KI67 (green) and pS6 (green), progenitor-related marker SOX9 (green), and nuclei marker DAPI (blue) in 15th generation patients-derived organoids from ascites. Scale bar, 100 μm. The experiment was repeated with 4 independent experiments, with similar results. e Fifteenth generation organoids generated as clones from single cells dissociated from 14th generation organoids after addition of inhibitors or vehicle when single cell suspensions were replated. Red arrows indicate application of autophagy and mTORC1 inhibitors promoting organoids death. Scale bar, 400 μm. The experiment was repeated with four independent experiments, with similar results. f Quantification of the size of 15th generation organoids as in (e) after 7-day treatment with autophagy or mTORC1 inhibitors (n = 4 independent experiments). Each datapoint represents the mean of mean values of organoids in all wells. Every well included the means of 25+ counts. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars); p-values are calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. g Immunofluorescence staining for apoptosis marker CC3 (green), proliferation marker KI67 (pink), and nuclei marker DAPI (blue) in 15th generation organoids as in (e) after 7-days treatment with autophagy or mTORC1 inhibitors. Scale bar, 100 μm. h The ratio of CC3/KI67 positive cells as in (g) (n = 4 independent experiments). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM (error bars); p-values are calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test.

To examine the influence of autophagy and mTORC1 inhibitors on peritoneal metastasis in vivo, three groups of mice were all intraperitoneally injected with PDOs and then treated with PBS, hydroxychloroquine, or rapamycin. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) displayed that both hydroxychloroquine and rapamycin clearly inhibited peritoneal metastasis, and hydroxychloroquine was more effective (Supplementary Fig. 7f,g), consistent with the PDO results in vitro.

Discussion

GCPM has poor prognosis and high mortality with poor therapeutic outcomes2–4. The study of GPCM is complicated since the complexity of the peritoneal ecosystem and the mechanisms of GCPM remain to be deciphered. Here, we used single-cell RNA sequencing to comprehensively characterize the peritoneal ecosystem. Our analysis reveals distinct and dynamic changes within the ascites ecosystem during GCPM and illustrates the evolution of peritoneal cells induced by chemotherapy and immunotherapy at single-cell resolution.

Antigen presentation is the main function of DCs87–89, and we found that DC clusters exhibited slightly increased antigen-presenting capacity in the G1 Group compared to the G0 Group and then decreased antigen-presenting capacity in the G2 Group compared to the G1 Group, consistent with their higher cell proportions among the G0-G2 Groups, suggesting that early-stage disease may have an effect on DC proportion and function. This supports the current viewpoint that primary tumors can modify distant ecosystems to form pre-metastatic niches before tumor metastasis90,91. The DC cluster variations across different disease stages, particularly in cDC2, indicate the complexity of the DC-mediated tumor immune response caused by GCPM. Monocyte-derived DCs can impede differentiation and IFN production in CD4 T cells92. The proliferative C3-DC cluster expressed lower MHC-I and MHC-II levels, indicative of a monocyte-like phenotype with reduced antigen-presenting capacity and increased pro-angiogenic functions and cell proportion during GCPM. Developmental trajectory analysis confirmed that the C3-DC cluster featured immunosuppressive, pro-angiogenic and proliferative capacity. Altogether, based on their dynamic changes in cell proportion and function, monocyte-like DCs contribute to a unique peritoneal immune ecosystem, aiding in formation of an immunosuppressive and pro-angiogenic ecosystem favorable for GCPM.

T cells represent key cytotoxic immune cells during tumorigenesis and cancer metastasis48. Both C2-CD4 naïve and C3-CD4 Treg clusters showed increased cell proportion and naïve function score during GCPD, whereas the C1-CD4 T cell cluster was more prone to a naïve phenotype in GCPM than in non-GCPM without obvious changes in cell proportion. Notably, expression of genes involved in naïve function such as SELL and CCR7 increased along with disease state, but genes involved in inhibitory checkpoints (i.e., CTLA4 and TIGIT) were not obviously affected. Therefore, these CD4 clusters either increased their naïve function or their immunosuppressive cell proportion, implying that both non-functional and immunosuppressive cells become enhanced in the peritoneal ecosystem during GCPM. Moreover, CD8 cluster cytotoxic function was attenuated in peritoneal tumor immunity in GCPM. Notably, the C2-CD8 cluster was characterized by low expression of cytokines/chemokines (CCL3, CCL4L2, XCL1, and XCL2), which might hinder infiltration of effector CD8 T/NK cells and DCs into the peritoneum for their anti-tumor functions93–95. Thus, T cell immune function already begins to deplete prior to GCPM, with significant depletion in GCPM and an obviously increased naïve/immunosuppressive phenotype, eventually promoting GCPM by inhibiting peritoneal immunity.

Paligenosis is a conserved cellular program for cells to undergo plastic changes respond to damage and maintain homeostasis19. It has previously been characterized in multiple normal tissues and cells. For successful paligenosis, cells require stress response proteins such as DDIT4, ATF3 and IFRD1, whose actions modulate critical cell energy and survival networks centered on mTORC1 and P5377. During gastric tumorigenesis, there is evidence that pre-cancerous metaplasia is a normal, wound-healing, regenerative response that is proceeded by paligenosis. However, when paligenosis is abnormal, paligenotic cells with DNA damage are not eliminated or stalled until DNA repair is complete. Such cells can then accumulate DNA damage and undergo malignant transformation, ultimately leading to diffuse GC initiation75,76. Once GC is established via aberrant paligenosis, GC cells may maintain this abnormal paligenosis propensity, which they induce in response to stress of various kinds: either endogenous due to hypoxia/starvation from tumor overgrowth of blood supply or exogenous due to chemotherapy or immunotherapy. We presume that GC cells can use a modified paligenosis program (and its associated metabolic/mTORC1 modulating processes) to evade immune cells and therapy and promoting invasion and metastasis as cancer progresses.

In the current study, we noticed GC cells shifted from a high-plasticity state (early paligenosis with autophagy) to a high-proliferative state (late paligenosis with strong mTORC1 activation) in untreated GCPM patient ascites, with a cell trajectory consistent with the paligenosis program. Previous studies reported that mTORC1 controls the adaptive transition of quiescent cells in G0 to re-enter the cell cycle in response to injury-induced signals78. Accordingly, we observed that the highly plastic GC cells in the G3 Group evolved to gain even higher plasticity upon systemic therapy in the G4 Group. The simultaneous appearance of these different high-plasticity clusters is consistent with the highly heterogenous nature of GC17,96,97. Therapy-resistance is usually achieved by acquiring high-plasticity states through increased expression of stemness-related genes98,99. Within the plasticity response, such stemness-related genes (like SOX9) might be induced via paligenosis, the first stage of which is a large upregulation of autophagy and lysosomes.

Tumors are composed of heterogeneous cell populations that exhibit varying degrees of functional and genetic heterogeneity100,101. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) were proposed four decades ago, and are defined as rare cell populations with unlimited self-renewal potential, driving tumorigenesis, clonogenicity, metastasis and drug resistance, and maintaining tumor microenvironment101–103. Interestingly, in this study, we found two different populations in the peritoneal cavity microenvironment of GCPM (C2-Tumor cell and C3-Tumor cell clusters) that could functionally serve as CSCs. One cluster (C2 Tumor cells) expressed stem-related genes (SOX4 and CD164); the other (C3-Tumor cells) expressed proliferative genes (MKI67 and MCM2). Cell trajectory analysis showed that the two clusters could transition from C2-Tumor cell to C3-Tumor cell clusters, undergoing inactivation of stem-related signal pathways and activation of proliferative signal pathways. Thus, CSC potential may be maintained by plasticity via a paligenosis-like program. Importantly, paligenosis is a stepwise, specific program with multiple cellular pathways involved. Considering tumor plasticity from a paligenosis perspective thus may open many avenues to design antitumor therapies and/or augment existing therapy. Promisingly, we found that targeting paligenosis using autophagy and mTORC1 inhibitors reduced proliferation of PDOs from ascites by inducing apoptosis.

Tumor infiltrating immune cells feature immunosuppressive and pro-tumorigenic functions and play distinct and complex roles in tumor ecosystems104,105. Tumor cells with pluripotent and plastic characteristics can self-renew to propagate tumorigenesis and metastasis106–108. Immune cells support tumor growth and metastasis and also remodel the tumor ecosystem to maintain a suitable niche109. For example, TAM-like macrophages have been reported to promote cancer stem cell-like characteristics via cytokine pathways110,111. Our cell–cell interaction analysis highlighted intercellular interactions between monocyte-like DCs and cycling T clusters and between C2 tumor cells and C3 tumor cells in the peritoneal ecosystem. Therefore, we speculate that proliferative monocyte-like DCs and cycling T cells maintain tumor cell plasticity in the peritoneal cavity via ligand-receptor communication pathways. In our study, SPP1 and HGF were indicated to mediate crosstalk between proliferative C3-DC and tumor cells to maintain stem cell ability in tumor cells via SPP1-CD44 and HGF-CD44 ligand-receptors112–114. Proliferative cycling T cells may also play critical roles in maintaining tumor cell plasticity in GCPM via SPP1-CD44112. Thus, to effectively prevent and treat GCPM, immunotherapy strategies must consider the unique immunological characteristics and stemness of peritoneal infiltrating tumor cells and their intercellular interactions with immune cells.

Studying the ecosystems of ascites caused by other ascites-producing conditions will be helpful to provide a crucial direction for the further study of ascites of gastric cancer. A published study indicates that the myeloid cells and lymphocytes in hepatocellular-carcinoma-related ascites have distinct origins and are predominantly linked to primary tumor and peripheral blood origins, respectively44. Ascites caused by high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) is known to be associated with drug resistance and a poor prognosis115, and the ascites ecosystem harbors several distinct cell clusters including immune cells, epithelial cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts116. Interestingly, the molecular subtypes of HGSOC mainly reflect the tumor ecosystem composition (the abundance of immune infiltrates and fibroblasts) rather than distinct subsets of malignant cells, and inflammatory reprogramming of tumor cells depends on an intact ascites microenvironment, reflecting an endogenous property of the tumor cells116. Since the immune characteristics of peripheral blood are quite different from those of tumors, and sampling ascites via paracentesis is far easier and safer than tissue biopsy, these results provide a direction for the detection of tumor status by sampling ascites instead of peripheral blood or biopsy tissue. Further study should explore the specific ecosystem characteristics of ascites of gastric cancer by comparing the ascites caused by other different ascites-producing conditions.

In conclusion, our study describes different cell developmental lineage trajectories in the peritoneal ecosystem and provides evidence to better understand the mechanism of GCPM, aiding exploration of effective target strategies for GCPM therapy.

Methods

Patient samples and ethics statement

Seventeen samples of malignant ascites fluid were collected from patients pathologically diagnosed with GC and 18 peritoneal lavage fluid samples were collected from GC patients without GCPM or from benign hysteromyoma patients from four medical centers: the First Hospital of China Medical University, the Sheng Jing Hospital of China Medical University, the Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute, and the People’s Hospital of Liaoning Province. Early gastric cancer is limited to the mucosa or submucosa (pT1), with a very low risk of distant metastasis and is amenable to endoscopic resection, while advanced gastric cancer refers to tumors that invade the muscularis propria and beyond (pT2 or higher) recommended radical gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy117–122. Of these collected samples, four control peritoneal lavage fluid samples were taken from four benign hysteromyoma patients (negative controls, G0 Group); peritoneal lavage fluid from four early GC patients (G1 Group); peritoneal lavage fluid from 10 advanced GC patients (G2 Group); ascites from 12 untreated GC patients with diagnosed GCPM (G3 Group) and ascites from five GC patients with diagnosed GCPM following systemic therapy (G4 Group). Of the G4 group, three and two patients were treated with chemotherapy and anti-PD-1/PD-L1immunotherapy, respectively. Some ascites samples were obtained under laparoscopic exploration due to GCPM. Detailed clinical, pathological, and therapeutic history information are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. This study was performed following the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and these hospitals (Shenyang, China). Informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients before collection of samples and clinical information.

Sample collection and single-cell suspension processing

Ascites fluids and peritoneal lavage fluids were immediately transported to our laboratory on ice following drainage. Liquid samples were aliquoted into 50-ml centrifuged tubes through 70-um cell strainers (Cat# 352350, BD FALCON) and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min at 4 °C. After supernatant removal, the remaining cell pellet was resuspended in red blood cell lysis buffer (Cat# R1010, Solarbio) and incubated on ice for 5 min to remove red blood cell contamination. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Cat# SH30256.01, HyClone) was used to quench the red blood cell lysis buffer and then the cell suspension was centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min at 4 °C to pellet the cells. The above process of red blood cell lysis was repeated until no red blood cells were visible. The resulting cell pellet was washed twice with PBS then resuspended in sorting buffer (PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum [FBS; Cat# DT-100-S, DearyTech]). Cell concentration and viability were analyzed using Countstar Automated Cell Counter (Model# Rigel S2, ALIT Life Sciences) with acridine orange/propidium iodide (AO/PI) double staining assay (Cat# CS2-0106-5ML, Nexcelom Bioscience). Single-cell suspensions with over 85% viability were used for scRNA-seq assay. Generally, the entire process from sample collection to single-cell suspension loaded on the 10x Chromium Controller microfluidic device (10x Genomics) was completed within 2-4 h.

Single-cell RNA library preparation and sequencing

Nanoliter-scale Gel Beads-in-emulsion (GEM) generation & barcoding, reverse transcription, complementary DNA (cDNA) amplification, and 3' gene expression dual index library construction steps were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions of the 10x Genomics Chromium single cell 3' platform (10x Genomics). Briefly, single-cell GEM generation was performed on a 10x Chromium Controller (Mode l# GCG-SR-1, 10x Genomics) using Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3ʹ Reagent Kit v3.1 (Cat# PN-1000268, 10x Genomics) and Chromium Next GEM Chip G Single Cell Kit (Cat# PN-1000120, 10x Genomics). Concentrations of single cell suspensions were adjusted to 800-1200 cells/μL (measured by CountStar), and then about 10000 cells per sample were loaded on each channel of the 10x Genomics Chromium system (GEM generation & barcoding) per sample. The cells were partitioned into GEM to achieve single cell resolution. Captured single cells were lysed and the released RNAs were barcoded through reverse transcription in individual GEMs. Reverse transcription of GEMs was performed using a Thermal Cycler (Model# 9902, Applied Biosystems) at 53 °C for 45 min, 85 °C for 5 min, then held at 4 °C. cDNA was PCR amplified to generate sufficient mass for library construction and cDNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 4200 TapeStation system (Agilent Technologies). Finally, barcoded cDNA libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq6000 sequencer using a pair-end 150 bp (PE150) reading strategy (CapitalBio Technology, China). To reduce batch effects among samples, all cDNA libraries were constructed using the same reagent kit and protocol.

Ascites PDOs culture and treatment

PDOs were derived from ascites drainage samples from four patients with GCPM. Ascites drainage was filtered with a 70-um cell strainer then centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min. Pellets were resuspended into single-cell suspensions with PBS and incubated with red blood cell lysis buffer for 5 min on ice, then centrifuged again at 300 g for 5 min. Finally, the cells were embedded in Matrigel, seeded onto pre-warmed 24-well culture plates, and cultured in Advanced DMEM/F12 medium (GIBICO) with 50% L-WRN conditioned medium supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (GIBICO), 10 mM Nicotinamide (Sigma), 1X N2 (GIBICO), 1X B27 (GIBICO), 1X Glutamax (GIBICO), 1.25 mM N-Acetylcysteine (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 ng/mL EGF (Peprotech), 200 ng/mL FGF10 (Peprotech), 10 nM gastrin (R&D Systems), and 1X Primocin (Invivogen). 10 uM ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632, R&D Systems) was provided for the first generation of PDOs to prevent anoikis. PDOs were overlaid with culture medium and incubated at 37 °C in humidified air containing 5% CO2. Culture medium was changed every 3 days. For passaging, PDOs were collected by mechanically dissociating the Matrigel, centrifuged at 150 g for 5 min, incubated with pre-warmed TrypLE express for 7 min, then pipetted about 100 times. All PDOs were trypsinized to single cells under a light microscope then transferred into new matrigel with culture medium and plated in pre-warmed 24 well-plates, incubated at 37 °C in humidified air containing 5% CO2. PDOs were passaged every 7 days until at least the 15th generation. PDOs were treated with culture media and inhibitors including Hydroxychloroquine Sulfate (1uM), DC661 (4uM), TORIN1 (2uM), or Rapamycin (400 nM) for 7 days before analysis. Culture medium and drugs were changed every 3 days. To embed PDOs, culture media was removed, PDOs were washed in DPBS on ice for 15 mins, then PDOs were fixed in 10% formalin on ice for 2 h. Finally, PDOs were moved to 75% ethanol at 4 °C overnight, mounted in 3% agar, and embedded in paraffin.

Patient-derived organoid xenograft (PDOX) animal experiments

NOD/SCID mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology (Beijing, China). Ascites organoids were digested into single cells using TrypLE. An amount of 1 × 106 cells in 0.2 mL Advanced DMEM/F12 medium with 2% FBS were intraperitoneal injected to the 6-week-old female NOD/SCID mice. Two weeks after the cells were injected, mice were treated with rapamycin and hydroxychloroquine every 3 days for 3 weeks. For rapamycin group, mice were treated with 3 μg/g rapamycin (LC Laboratories) in 0.25% Tween-20, 0.25% polyethylene glycol in PBS every 3 days. For hydroxychloroquine sulfate group, mice were treated with 30 μg/g hydroxychloroquine sulfate (Selleck) in PBS every 3 days. After 5 weeks of cell injection, tumor-bearing mice were injected intravenously with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) (8.32 ± 0.92MBq) via the tail-vein. For best contrast, PET imaging performed after 30 min metabolism. Commercial software MadicPet was used to reconstruct PET images. The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was measured for semi-quantitative analysis. After the 18F-FDG PET scan, mice were sacrificed and peritoneal tumors were isolated and embedded in paraffin. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the ARRIVE guidelines, and the institutional ethical guidelines (China Medical University Animal Studies Committees). Mice were sacrificed by euthanasia when the tumor size reached the limitation (maximal tumor diameter ≥ 10 mm).

Immunofluorescence staining

Organoid microtome sections underwent a standard deparaffinization protocol with xylene and rehydration then were antigen retrieved in sodium citrate buffer (2.94 g sodium citrate, 500 uL Tween 20, pH 6.0) using a pressure cooker. Sections were blocked in 1%BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 60 min. Primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4 °C, see Supplementary Table 4. For immunofluorescence staining, organoid slides were washed in PBS and incubated with Alexa-fluor (Invitrogen) secondary antibodies at room temperature for 60 min, then 4',6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to detect nuclei. Slides were washed in PBS and mounted using ProLong Gold antifade mountant with DAPI (Molecular Probes) and stored at 4 °C. All immunofluorescence images of organoids were captured with citation3 (BioTek instruments, Inc.). All experiments were performed at least three times by the same scientific researcher. Detailed information of antibody application and dilution is shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The concentrations of cytokines of ascites and peritoneal lavage fluids were measured by ELISA (R&D Systems®). Briefly, samples were centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min at 4 °C to remove the cell pellet. The detailed experiment processes were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions of the ELISA kits. Finally, the concentrations of cytokines were measured via microplate reader (Infinite M200 Pro, TECAN) capable of measuring absorbance at 450 nm, with the correction wavelength set at 540 nm. ELISA data were collected using Tecan i-control Software (version 1.11, TECAN).

Flow cytometry (fluorescence-activated cell sorting, FACS) of monocyte-like dendritic cells

Single-cell suspension was obtained after filtration and centrifugation. The cells for FACS were stained with Fluorophore-conjugated antibodies containing CD45-eFluor (Cat# 69-0459-42, eBioscience™), CD3-FITC (Cat# 11-0037-42, eBioscience™), CD56-FITC (Cat# 11-0566-42, eBioscience™), CD19-FITC (Cat# 11-0199-42, eBioscience™), CD1c-APC (Cat# 331524, BioLegend), CD163-PE (Cat# 12-1639-42, eBioscience™), CD14-BV421(Cat# 563743, DB Biosciences) on ice for 30 min. After washing twice with FACS buffer, the cells were stained using 7-AAD Viability Staining Solution (Cat# 00-6993-50, eBioscience™) on ice 5 min. FACSAriaIII (BD Biosciences) was used for FACS. FACS data were collected using BD FACS Diva Software (version 8.0.2, BD), and data were analyzed with FlowJo software. Detailed information of antibody application and dilution is shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Single-cell RNA-seq data processing

Raw scRNA-seq data were processed using Cell Ranger Software (version 4.0.0, 10x Genomics) obtained from the 10x Genomics official website (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/overview/welcome) for demultiplexing, barcode processing, read alignment to GRCh38 human reference genome, single-cell 3' gene counting, and generation of feature (gene)-barcode expression matrix. The preliminary filtered data generated by Cell Ranger were used for downstream analysis. Quality of cells was assessed based total UMI counts per cell, total detected genes per cell, and proportion of mitochondrial genes per cell. Low-quality cells were filtered following these criteria: (1) cells with <200 genes; (2) cells with <800 UMI counts or ranked in the top 1% of UMI counts; (3) cells with >20% mitochondrial gene count. Genes detected in less than three cells were also excluded from downstream analyses. Subsequently, the “DoubletFinder” R package was used to predict and remove potential doublets123. Library size normalization was performed to obtain a normalized barcode-count matrix using the “NormalizeData” function in “Seurat” R package based on the gene counts of each cell124. Briefly, size factors of each cell were computed by dividing the total gene UMI counts in that cell by a scale factor of 10000 (Size Factor = total gene UMI counts/10000), and then normalized gene UMI counts (GUCnormalized) for each cell were computed by dividing the gene UMI counts by the size factor for that cell (GUCnormalized = Gene UMI Counts/Size Factor), which was a TPM-like values. Finally, normalized gene expression values were quantified as log2(GUCnormalized + 1) for subsequent downstream analyses.

Multiple scRNA-seq dataset integration and batch correction

This study included different samples of ascites fluid and peritoneal lavage fluid from benign hysteromyoma patients and different stages of GC to explore the landscape and dynamic change of the peritoneal ecosystem during GCPM. Samples were from different donors (G0-G4 Groups), and the whole experiment of single-cell sequencing was performed several times due to sample collection. Thus, batch effects were an important factor that could not be ignored. To integrate multiple scRNA-seq datasets into a shared space from different groups for unsupervised clustering and reduce batch effects, the harmony integration algorithm was used on the PCA space, which has been reported to reduce experimental and technical batch effects while preserving biological variation and the continuous state of developmental cells rather than erroneously clustering cells into discrete groups125. The Harmony algorithm has been widely used to integrate multiple single-cell RNA-seq datasets44,126–128.

Dimensionality reduction, unsupervised cell clustering, and visualization

The Seurat v3 R package was used for data scaling, highly variable gene selection, dimensionality reduction, unsupervised clustering, and visualization by using the normalized filtered feature-barcode expression matrix124. In brief, the matrix was scaled using the “ScaleData” function in the Seurat R package, and highly variable genes, which could preserve major biology variation, were identified for subsequent principal component analysis (PCA) using the “FindVariableGenes” and “RunPCA” functions in “Seurat” R package. An appropriate number of principal components were used based on the PCA results, and specific resolution parameters were selected for further unsupervised graph-based clustering to determine an optimal number of cell clusters using the “FindNeighbors” and “FindClusters” functions. For visualization of graph-based cell clustering, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) was applied with the “RunUMAP” function.

Differential expressed gene analysis, cell annotation, and cell re-clustering

To identify cluster-specific markers genes, differential expressed gene (DEG) analysis between the corresponding cluster compared with all other clusters was performed using the Seurat “FindMarkers” function with default parameters of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Significant DEGs were defined as |log2(Fold Change)| > 0.50 and False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.01. Cell clusters were annotated following the following steps: (1) Cell type was automatically annotated using the “singleR” R package (https://github.com/dviraran/SingleR)129, with unbiased cell type recognition by leveraging reference transcriptomic datasets of pure cell types to infer the cell of origin for each single cell independently; (2) We summarized sets of well-known marker genes for each cell types; (3) Cell annotation by the “singleR” function was manually verified or corrected based on expression of known marker genes and based on the top 50 most upregulated genes in each cluster; (4) Cells simultaneously expressing two or more sets of marker genes of cell types were labeled as doublets or multiplets and excluded from the downstream analysis.