Abstract

The present paper deals with the modeling of the COVID-19 via fractal interpolation function (FIF) and the estimation of the dimension of constructed FIF. Further, we determine the adjoint of the fractal operator defined on space associated with the FIF.

Introduction

Several outbreaks have occurred in India over the last century, but none have been as deadly as the COVID-19 outbreaks. The first indication that the COVID-19 outbreak has spread to India is on January 27, 2020, when the first case of infection in Kerala, India, was reported. Since then, the entire country has been in a state of chaos and turbulence as a result of the virus’s increasing casualties. Coronavirus disease caused by the coronavirus strain, viz., Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), mainly affects the respiratory system of the human body. The disease is highly contagious, which explains the high death toll. In the battle with this infectious disease, mankind has had to discover a strategy to survive. Active surveillance of the increase in the number of infected cases and deaths due to COVID-19 through a fractal interpolation polynomial provides a way to better understand the dynamical nature of the virus. In this attempt, several authors studied the dynamic nature of the COVID-19 virus via the fractal-based models [11, 14, 19, 28].

There are numerous real-world applications for functional interpolation from a given data set. In the classical approach, the interpolation has been accomplished by smooth functions, sometimes infinitely differentiable, but natural phenomena may occur with sudden changes. In 1986, Barnsley [6, 7] used the concept of an iterated function system (IFS) to introduce continuous interpolation functions called fractal interpolation functions (FIFs). For more details about these IFS and related concept, we refer the interested reader to, for instance, [12, 16, 22].

In advance of the classical approach, these FIFs possess a self-similar nature on small scales and are not essentially smooth. Due to advancements in its properties, this theory gained remarkable attention in mathematical modeling. Following that Navascués [25] introduced -fractal functions on a real compact interval. Motivated by Navascués work, bivariate [9, 21–23], multivariate [1, 29, 30], vector-valued [39], complex-valued [40], set-valued [31] -fractal functions as well as fractal functions on the fractal domains [2, 3, 32, 34] are constructed and studied recently. We also encourage to see some recent works [5, 10, 17, 18, 35, 36] on non-stationary fractal functions which are generalizations of fractal functions and fractal dimension of fractal functions. The fractal interpolation function has numerous applications in real life and medical science [13, 15, 28, 41].

Computation of the fractal dimension of a given set, the graph of a function and measure is an integral part of fractal analysis. Fractal dimension has a nice connection with some topological properties of a metric space. For example, if box dimension of a set is strictly less than 1, then the set will be totally disconnected, for more details, see [12]. Liang [20] proved that for a continuous function of bounded variation on the unit interval [0, 1], its graph has box dimension 1. We can also note (see, for instance, [12]) that if a real-valued function is Hölder continuous with Hölder exponent then the upper box dimension of its graph is less than . Some works related to the estimation and computation of fractal dimension of fractal sets and functions can be seen in [1, 2, 8, 10, 12, 18, 22, 29, 38].

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we provide background related to the article where we discussed in detail the construction of the fractal interpolation function and the basic of fractal dimensions. In Sect. 3, we modeled COVID-19 using the data collected from the second wave in India and estimate the fractal dimension of the constructed FIFs. Further, we define the fractal operator on space and determine the adjoint of the fractal operator using series expansions. In Sect. 4, we close the discussion of this paper by writing some concluding remarks and some possible future works.

Fractal functions

Let the interpolation data set be given as such that Consider the intervals and for Define a function such that it is a contractive homeomorphism and satisfies

Define a continuous function such that it is a contraction in second co-ordinate and satisfies the join-up condition, that is,

where and

Define a function as

Thus, is an iterated function system (IFS). Using Theorem 1 of [7], the IFS defined above has a unique attractor which is the graph of the continuous function satisfying the self-referential equation given as

The functions and mentioned above can be chosen as

where such that and is a continuous function given as

where the continuous function is called a base function satisfying and is the original interpolating function satisfying the interpolation points, called the germ function. Since the function also satisfies the join-up conditions, we obtain,

Consequently, the IFS has a unique attractor given by the graph of the continuous function f, denoted by and satisfies the self-referential equation given as

Therefore, for any partition of the interval , scaling vector and base function b, we get a fractal interpolation function , called -fractal interpolation function. For box dimensions, we refer the reader to [12].

Definition 2.1

Let A be a non-empty bounded subset of the metric space (X, d). The box dimension of A is defined as

provided the limit exists, where denotes the smallest number of sets of diameter at most that can cover A. If this limit does not exist, then the upper and the lower box dimension, respectively, are defined as

The following result is a special case of Theorem 3 in [8] applied to Lipschitz functions.

Theorem 2.2

Let be a partition of satisfying and let . Assume that f and b are Lipschitz functions defined on I with and . If the data points are not collinear, then

where denotes the graph of and D is the unique positive solution of the equation given as

COVID-19

Our objective is to understand the epidemic from a fractal point of view which will be a better method to analyze the growth of the virus. In that facet, we collected the data from India and constructed the -fractal interpolation function following the procedure mentioned before. The number of positive cases at a difference of forty days starting from 15th Nov 2021 is taken as shown in Table 1. All the data that is shown in Table 1 is gathered from ourworldindata.org [42].

Table 1.

Cases of Covid-19

| S.No. | Date | (Number of positive cases) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15 Nov, 2021 | 0 | 8865 |

| 1 | 25 Dec, 2021 | 0.1 | 6987 |

| 2 | 3 Feb, 2022 | 0.2 | 149394 |

| 3 | 15 March, 2022 | 0.3 | 2876 |

| 4 | 24 April, 2022 | 0.4 | 2541 |

| 5 | 3 June, 2022 | 0.5 | 3962 |

| 6 | 13 July, 2022 | 0.6 | 20139 |

| 7 | 22 Aug, 2022 | 0.7 | 8586 |

| 8 | 1 Oct, 2022 | 0.8 | 3375 |

| 9 | 10 Nov, 2022 | 0.9 | 4517 |

| 10 | 20 Dec, 2022 | 1 | 132 |

Thus, the set of interpolation points is given by . In the first case base function b is taken to be line passing through and , that is, and germ function f is taken as

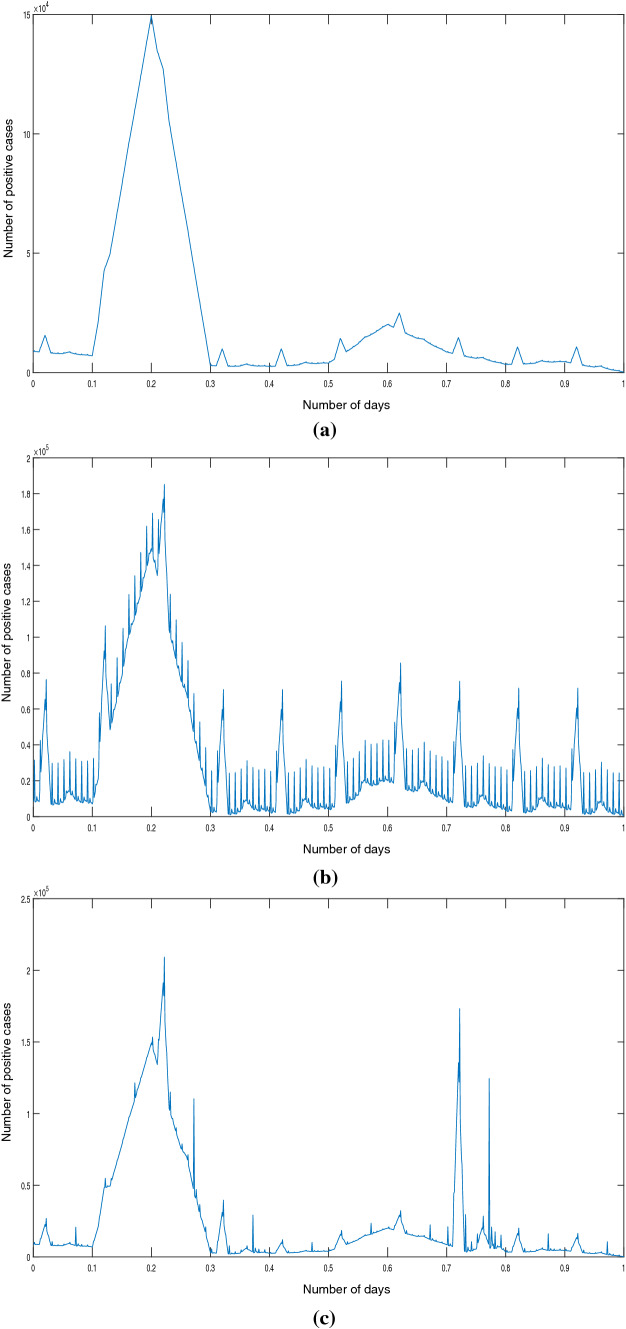

For , the function . Now by varying the vector scale function, we get different fractal function represented in a graph. For its fractal function is represented in Fig. 1a. Again for its fractal function is represented in Fig. 1b. Now for we get Fig. 1c.

Fig. 1.

a when and . b when and . c when and

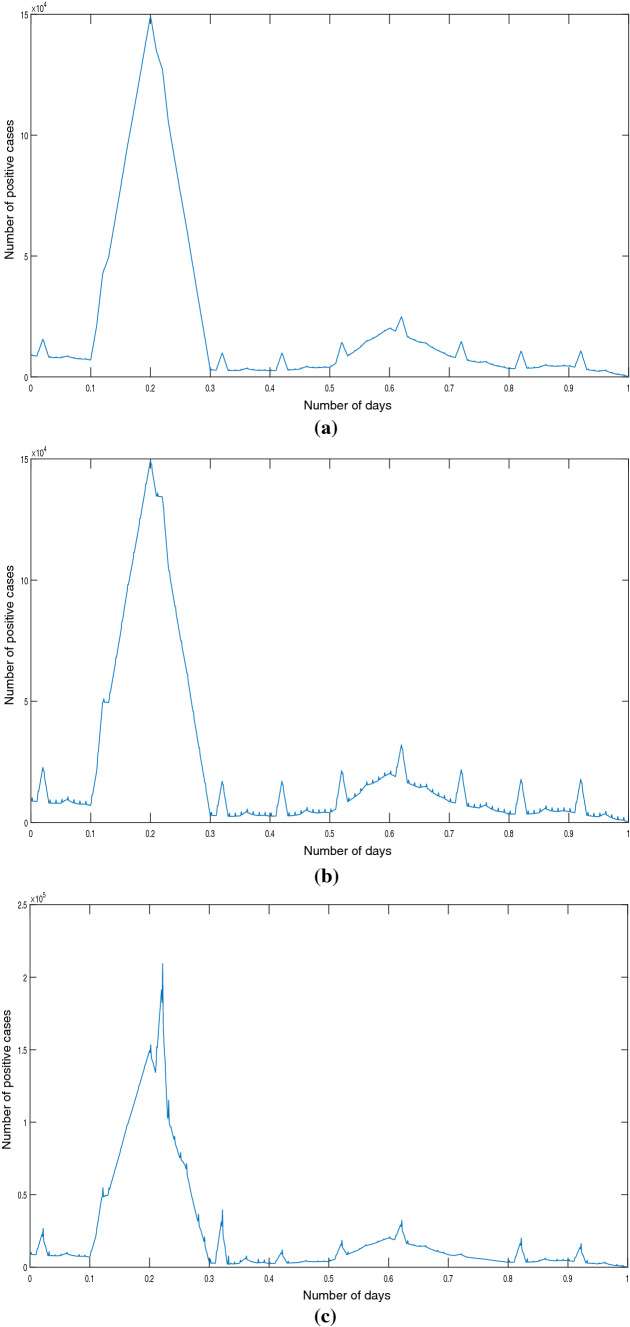

Consider the germ function f given before and take base function b as a Bernstein polynomial of order 2 written as

that is,

Now by varying we get different fractal interpolations represented in a graph. As for we get Fig. 2a, and for we get Fig. 2b. Again for the fractal function obtained is represented in Fig. 2c. Let us note the following:

All functions and are Lipschitz functions for each

The data set are not collinear.

In view of the above, we can apply Theorem 2.2 to compute the fractal dimension of the graphs of the -fractal functions associated with these data set and considered functions to analyze fluctuation in the number of positive cases.

Fig. 2.

a when and . b when and . c when and

A fractal operator

Let be the germ function and let the base function , where be a bounded linear map such that , , and . We shall denote the corresponding -fractal function by . Let us fix the elements in the corresponding IFS, namely, the partition , scale vector , and operator L. Let us note the following definition due to Navascués [24].

Definition 3.1

We refer to the transformation which assigns to f, as a -fractal operator or simply fractal operator with respect to and L.

Navascués [25, Theorem 3.3] proved the next theorem.

Theorem 3.2

Let , and let Id be the identity operator on .

- For any , the perturbation error satisfies

- The fractal operator is a bounded linear map. Further, the operator norm satisfies

For , is bounded below. In particular, is an injective map.

, then is a topological isomorphism (that is, bijective bounded map with bounded inverse). Moreover,

For , the fractal operator is not a compact operator.

Remark 3.3

According to item (1) of the previous theorem, the collection of maps constitutes continuous functions containing f as a particular case (for ). Furthermore, the inequality therein reveals that by appropriate choice of the scale vector or operator L, the fractal perturbation can be made close to the original function f. Thus, is a simultaneously interpolating and approximating fractal function to f.

Let The Bernstein polynomial of order n is defined as

Note 1 Let us note the following:

Choosing we have

This implies that and Now, for every we get

Since the Bernstein operator is a linear positive operator, the previous inequality gives

which produces Therefore, we have for all We know that for a bounded linear operator T and the operator norm , the spectral radius of T is given by

Since we have

Adjoint of on

We now consider the Banach space of functions with finite energy:

where the norm is defined by

Note that the space is in fact a Hilbert space with respect to the inner product

It is worth to note that the construction of fractal functions in was initiated by Prof. Navascués in her work [25], wherein she also showed that every complex-valued square integrable function defined in a real bounded interval can be well approximated by a complex fractal function. Let . To construct the fractal function in corresponding to f, there are two approaches in the literature. One is to apply the density of in to obtain a fractal analog of using -fractal functions corresponding to continuous functions; see, for instance, [25]. Though this approach is natural and elementary, the self-referentiality of the fractal analog of is not evident in this case. Using another approach due to Massopust ([23, Theorem 2]), one may easily deduce the next theorem.

Theorem 3.4

Let be chosen arbitrarily and held fixed. Suppose that is a partition of I satisfying , for and . Let be affine maps satisfying and for . Further suppose that is an affinity satisfying and . Let the affinities be given by for . Fix for all and . Define by

If the scaling factors , satisfy , then the operator T is a contraction on . Furthermore, the corresponding unique fixed point (denoted for notational convenience by ) in satisfies the self-referential equation:

Note 2 Let be a bounded linear operator . Taking , in the previous theorem, one obtains fractal function corresponding to the germ function . Further, a bounded linear operator , arise.

Let be the aforementioned fractal operator. The adjoint of the fractal operator is defined by

In what follows we attempt to obtain an expression for

With the change of variable for the second term on the right-hand side, we have

From the previous equations

Expanding the terms to infinite times and writing as the adjoint operator of L we get

That is

Consequently, we have

Further simplification provides the following expression for

Since , we get the following expression for

Remark 3.5

Let us assume that the scaling vector is constant and the partition is equidistant. In this case, with the help of the above expression for the adjoint operator, we could deduce that the fractal operator turns out to be a topological isomorphism for a slightly wider range of values of the scaling factors than that prescribed in [25, Theorem 4.10]. It should also be noted that we may get better results for a fractal operator associated with non-stationary fractal functions [17, 27, 35] via the adjoint operator. To keep the article at a reasonable length we avoid the details.

Remark 3.6

Since fractal functions in can be discontinuous, we can use this space to model more natural phenomena with the help of fractal interpolation theory.

Concluding remarks and future directions

In this article, we computed the exact value of the box dimension of the graphs of the constructed fractal functions generated by the COVID-19 data over some specific time period. We also provided an expression for the adjoint operator of the associated fractal operator in terms of an infinite series. Calculating the fractal dimension of the epidemic curve is a new approach for observing the epidemic and retrieving the missing information via fractal functions. The higher the dimension of the graph of the epidemic curve, the higher the complexity of the distribution of the COVID-19 virus and it is affected by the parameter in the surrounding. In the future, we will try to estimate other fractal dimensions such as the Hausdorff dimension and Assouad dimension of the -fractal functions. As the Assouad dimension gives more local information, estimating this dimension for fractal functions generated by COVID-19 data may help us to understand the spread of the virus in a better way. We believe that our method of using fractal dimension and -fractal functions can be used to study fluctuations or randomness in the stock market and heart rate.

Author contribution statement

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Funding

The first author is financially supported by MHRD Fellowship at the Indian Institute of Information Technology (IIIT), Allahabad.

Data Availability

This manuscript has associated data in a data repository. [Author’s comment: We have taken COVID-19 data from https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases.]

Declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that we do not have any conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Ekta Agrawal, Email: ekta.agrawal5346@gmail.com.

Saurabh Verma, Email: saurabhverma@iiita.ac.in.

References

- 1.V. Agrawal, M. Pandey, T. Som, Box Dimension and Fractional Integrals of Multivariate Fractal Interpolation Functions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.13186 (2022)

- 2.Agrawal V, Som T. Fractal dimension of -fractal function on the Sierpiński Gasket. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2021;230(21):3781–3787. doi: 10.1140/epjs/s11734-021-00304-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrawal V, Som T. approximation using fractal functions on the Sierpiński gasket. Results Math. 2022;77(2):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00025-021-01565-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.V. Agrawal, T. Som, S. Verma, On bivariate fractal approximation, The Journal of Analysis (2022) 1-19

- 5.Amit, V. Basotia, and A. Prajapati, Non-stationary -contractions and associated fractals, J Anal (2022) 1-17

- 6.Barnsley MF. Fractals everywhere. Orlando, Florida: Academic Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnsley MF. Fractal functions and interpolation. Constr. Approx. 1986;2:303–332. doi: 10.1007/BF01893434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnsley MF, Elton J, Hardin DP, Massopust PR. Hidden variable fractal interpolation functions. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1989;20(5):1218–1248. doi: 10.1137/0520080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra S, Abbas S. The calculus of bivariate fractal interpolation surfaces. Fractals. 2021;29(3):2150066. doi: 10.1142/S0218348X21500663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.S. Chandra, S. Abbas, On fractal dimensions of fractal functions using functions spaces, Bull. Aust. Math. Soc. (2022) 1-11

- 11.Easwaramoorthy D, Gowrisankar A, Manimaran A, Nandhini S, Rondoni L, Banerjee S. An exploration of a fractal-based prognostic model and comparative analysis for the second wave of COVID-19 diffusion. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021;106(2):1375–1395. doi: 10.1007/s11071-021-06865-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.K. Falconer, Fractal geometry: mathematical foundations and applications, John Wiley and Sons, 2004

- 13.Fisher Y. Fractal Image Compression: Theory and Application. New York: Springer; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gowrisankar A, Priyanka TMC, Banerjee S. Omicron: a mysterious variant of concern. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 2022;137(1):1–8. doi: 10.1140/epjp/s13360-021-02321-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.A. L. Goldberger, L. A. Amaral, J. M. Hausdorff, P. C. Ivanov, C. K. Peng, and H. E. Stanley, Fractal dynamics in physiology: alterations with disease and aging, Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 99(suppl) (2002) 2466-2472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Hutchinson JE. Fractals and self-similarity. Indiana Univ. Math. J. 1981;30(5):713–747. doi: 10.1512/iumj.1981.30.30055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha S, Verma S, Chand AKB. Non-stationary zipper -fractal functions and associated fractal operator. Fractional Calculus and Applied Analysis. 2022;25(4):1527–1552. doi: 10.1007/s13540-022-00067-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jha S, Verma S. Dimensional analysis of -fractal functions. RM. 2021;76(4):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kavitha C, Gowrisankar A, Banerjee S. The second and third waves in India: when will the pandemic be culminated? Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 2021;136(5):1–12. doi: 10.1140/epjp/s13360-021-01586-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang YS. Box dimensions of Riemann-Liouville fractional integrals of continuous functions of bounded variation. Nonlinear Analysis: Theory, Methods & Applications. 2010;72(11):4304–4306. doi: 10.1016/j.na.2010.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massopust PR. Fractal functions and their applications. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals. 1997;8(2):171–190. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0779(96)00047-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Massopust PR. Fractal Functions, Fractal Surfaces, and Wavelets. 2. New York: Academic Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massopust PR. Local Fractal Functions in Besov and Triebel-Lizorkin Spaces. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2016;436(1):393–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jmaa.2015.12.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navascués MA. Fractal polynomial interpolation. Z. Anal. Anwend. 2005;25(2):401–418. doi: 10.4171/ZAA/1248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navascués MA. Fractal approximation. Complex Anal. Oper. Theory. 2010;4(4):953–974. doi: 10.1007/s11785-009-0033-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navascués MA. New equilibria of non-autonomous discrete dynamical systems. Chaos Solitons & Fractals. 2021;152:111413. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navascués MA, Verma S. Non-stationary -fractal surfaces. Mediterr. J. Math. 2023;20(1):1–18. doi: 10.1007/s00009-022-02242-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.C. M. Pǎcurar, B. R. Necula, An analysis of COVID-19 spread based on fractal interpolation and fractal dimension, Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 139 (2020) 110073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Pandey M, Agrawal V, Som T. Fractal dimension of multivariate -fractal functions and approximation aspects. Fractals. 2022;30(7):1–17. doi: 10.1142/S0218348X22501493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandey M, Agrawal V, Som T. Some Remarks on Multivariate Fractal Approximation. In Frontiers of Fractal Analysis Recent Advances and Challenges: CRC Press; 2022. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 31.M. Pandey, T. Som, S. Verma, Set-valued -fractal functions, arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.02635 (2022)

- 32.Prasad SA, Verma S. Fractal interpolation functions on products of the Sierpinski gaskets. Chaos, Solitons Fractals. 2023;166:112988. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ri S. A new idea to construct the fractal interpolation function. Indag. Math. 2018;29(3):962–971. doi: 10.1016/j.indag.2018.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahu A, Priyadarshi A. On the box-counting dimension of Graphs of harmonic functions on the Sierpiński gasket. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2020;487(2):124036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmaa.2020.124036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verma S, Jha S. A study on fractal operator corresponding to non-stationary fractal interpolation functions. In Frontiers of Fractal Analysis Recent Advances and Challenges: CRC Press; 2022. pp. 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verma S, Massopust PR. Dimension preserving approximation. Aequationes Math. 2022;96(6):1233–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00010-022-00893-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verma S, Sahu A. Bounded variation on the Sierpiński Gasket. Fractals. 2022;30(07):2250147. doi: 10.1142/S0218348X2250147X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.M. Verma, A. Priyadarshi, S. Verma, Fractal dimensions of fractal transformations and Quantization dimensions for bi-Lipschitz mappings. arXiv:2212.09669 (2022)

- 39.M. Verma, A. Priyadarshi, S. Verma, Vector-valued fractal functions: fractal dimension and fractional calculus. arXiv:2205.00892 (2022)

- 40.M. Verma, A. Priyadarshi, S. Verma, Fractal dimension for a class of complex-valued fractal interpolation functions. arXiv:2204.03622 (2022)

- 41.West BJ, Goldberger AL. Physiology in fractal dimensions. Am. Sci. 1987;75(4):354–365. [Google Scholar]

- 42.https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has associated data in a data repository. [Author’s comment: We have taken COVID-19 data from https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases.]