Abstract

This study examines the relationship between birth memory and recall and the perception of traumatic birth in women who were a postpartum one-year period and the affecting factors. This descriptive and correlational study was conducted with 285 participants in the pediatric department of a state university medical school. Data were collected using a participant information form, Birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire, and Perception of Traumatic Childbirth Scale. In the study, it was determined that the women had a moderate level of birth memories and recall, and the rate of those with a “high” and “very high” perception of traumatic childbirth was 45.9%. According to path analysis, Birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire score and educational status (primary secondary school) have a positive and significant effect on the perception of traumatic birth. The perception of traumatic birth was a predictor that explained 17.3% of birth memories and recall. Nearly half of the study participants perceived the experience of giving birth as traumatic, and birth memories and recall were at a moderate level. Improving women’s perception of education and traumatic birth will contribute to positive birth memories and to create positive emotions when they remember their birth.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12144-023-04336-3

Keywords: Birth memories, Postpartum, Recall, Traumatic birth

Introduction

Memory allows bringing past memories to the present, reliving events and revisiting places, and re-imagining the outcomes (Kensinger & Ford, 2020). Concurrently, memory is a mental capacity that involves processes such as acquiring, maintaining, and remembering knowledge, skills, and experiences (Naim et al., 2020). Recall is defined as the mental re-experiencing of an event from the past (Roediger & Tekin, 2020). In addition, memories containing intense emotions are relatively easier to remember (Kensinger & Ford, 2020). The longer one ponders over a new event, the longer it stays in short-term memory and the higher the probability that it will be transferred to long-term memory (Simkin, 1991). For this reason, many of the life events disappear completely after they remain in the short-term memory; however, parturition is one of the several situations that are transferred to the long-term memory.

A birth memory is an experience of giving birth that is present in the long-term memory of a woman and that can be remembered when necessary (Topkara & Çağan, 2020). In Simkin’s study on birth memories with 20 primiparous women shortly after birth and 20 years later, it was found that women generally remember their memories correctly. Women who experience negative emotions intensify and increase their emotions over time, whereas women with positive emotions remain the same (Simkin, 1991). Another study conducted in Japan with 1168 women a few days after giving birth and 5 years later reported that women clearly recall memories of their birth experiences 5 years after giving birth (Takehara et al., 2014). In order to maintain a woman’s mental health in the postpartum period, she is expected to have positive memories of the birth in her mind and she feels positive emotions when she remembers the birth (Ford & Ayers, 2009). For this reason, it is stated that birth memories and recall are important and these memories should be discovered (Hatamleh et al., 2013). Age, education level, history of miscarriage, planned pregnancy, and having trouble at birth are known to affect birth memory and recall (Thiel et al., 2021; Karakoç et al., 2022). Women’s memories of childbirth may affect the relationship between memory characteristics and emotion, perceived trauma, and psychological symptoms (Foley et al., 2014). Although childbirth is a positive experience for the majority of women, it is physically and psychologically traumatic for some women (Bastos et al., 2015).

Despite the person-to-person differences in the details of childbirth, the basic characteristics of the experience of giving birth are the same for all women (Crawley et al., 2018). Although happiness is experienced with the birth of a baby, the process of giving birth can become a traumatic experience for some women owing to pain and loss of control and possible medical interventions (Hoffmann & Banse, 2021). Approximately one third of women consider their birth as a traumatic experience (Ayers, 2004; Beck & Watson, 2008; Garthus-Niegel et al., 2013). Birth trauma is defined as “an event involving or posing a threat for serious injury or death of the mother or her baby during childbirth” (Beck & Watson, 2008). Socio-demographic characteristics (young age of the mother and low level of education and income), whether pregnancy was intended, delivery method, lack of support during delivery, intervention during labor, postpartum complications in the baby are among the factors affecting the perception of traumatic delivery (Aydın et al., 2022; Bay & Sayiner, 2021). Meanwhile, the perception of traumatic birth may be influenced by the woman’s personality traits and the meaning attributed by society and culture to birth (Ford & Ayers, 2009; İşbir & İnci, 2014). A traumatic birth experience can have a significant impact on the physical and emotional health of a woman, her baby, and her family (Elmir et al., 2010). Evidence suggests that a mother who experiences a traumatic birth can have a significant impact on her physical and psychological health, including postpartum depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and a negative experience of early motherhood (Bay & Sayiner, 2021; Elmir et al., 2010; Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019). If a woman experiences a traumatic birth and retain negative memories for a long time, this can affect her future birth experience, mother-baby bonding and breastfeeding problems, and her relationship with other family members (Bastos et al., 2015; Molloy et al., 2021; Priddis et al., 2018). Women who have experienced a traumatic birth are reportedly five times more likely to report fear of childbirth and prefer epidural anesthesia or cesarean delivery in their next pregnancy (Størksen et al., 2015). Perception of traumatic birth can be reduced by continuous care and support provided by nurses during delivery (Karaçam & Akyüz, 2011; Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019; Yalnız Dilcen et al., 2021). It also positively affects women’s long-term memories of birth experience (Bell & Andersson, 2016; Stadlmayr et al., 2006). The aim of the present study was to determine the relationship between women’s birth memory and recall and the perception of traumatic birth and the factors affecting it. In addition, we aimed to explore the network of relations between above mentioned variables.

Method

Research design and settings

This descriptive and correlational study was conducted in the pediatric department of a state university medical school.

Sampling and participants

The study population consisted of mothers who applied to the pediatric department for examination and control of their babies between March and May 2022. Women aged ≥ 18 years, had a baby aged 0–1, and had a cesarean section with vaginal, epidural/spinal anesthesia were included in the study. Women who gave birth under general anesthesia, had a psychiatric diagnosis (with self-report), and had vision and hearing problems were excluded from the study. Based on an effect size of 0.205 (Topkara & Çağan, 2020), a statistical power of 90%, and a significance level of 0.05, the minimum sample size was calculated to be 264. The study was completed with 285 women who met the inclusion criteria. This sample size also meets the recommended minimum of 200 samples for structural equation modeling (Kline, 2011) .

Instruments

Data were collected using a participant information form, Birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire (BirthMARQ), and Perception of Traumatic Childbirth Scale (PTCS).

Participant information form

The participant information form included questions about sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics.

Birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire (BirthMARQ)

BirthMARQ is a scale developed to measure the characteristics of memories of childbirth (9). The Turkish adaptation of the scale was prepared by Topkara and Çağan (2020). The scale consists of 6 sub-dimensions (emotional memory, ambivalent emotional memory, centrality of memory, coherence and reliving, sensory memory, and involuntary recall). Each sub-dimension is evaluated within itself and the Turkish version has a summability feature (F = 0.258 and p = 0.612). The scale is scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) out of a total of 21 items. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of the scale is 0.794 (Topkara & Çağan, 2020). The Cronbach alpha value of this study was 0.74.

Perception of traumatic childbirth scale (PTCS)

The PTCS scale was developed by Yalnız et al. (2016) in order to determine the perception of traumatic birth in women consists of a total of 13 questions and a single sub-dimension. The Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale was 0.89. The answer to each question is scored from 0 to 10, from nothing to the most severe. A minimum of 0 and a maximum of 130 points are obtained from the scale. Increase in the score obtained from the scale indicates an increase in the level of traumatic perception of birth. The total scale score of 0–26 points indicate very low, 27–52 points low, 53–78 points medium, 79–104 points high, and 105–130 points very high perception of traumatic birth (Yalnız et al., 2016). The Cronbach alpha value of this study was 0.85.

Statistical analysis

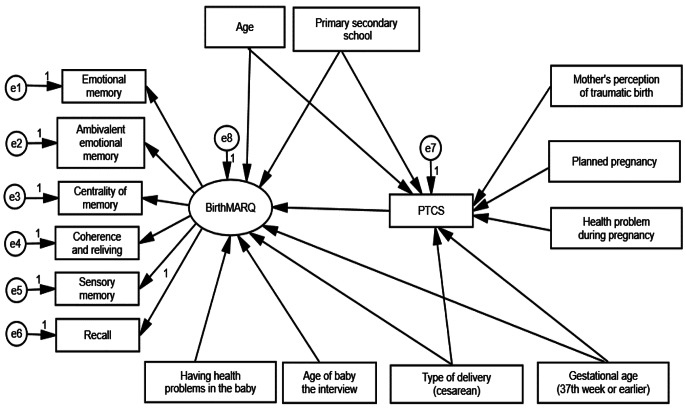

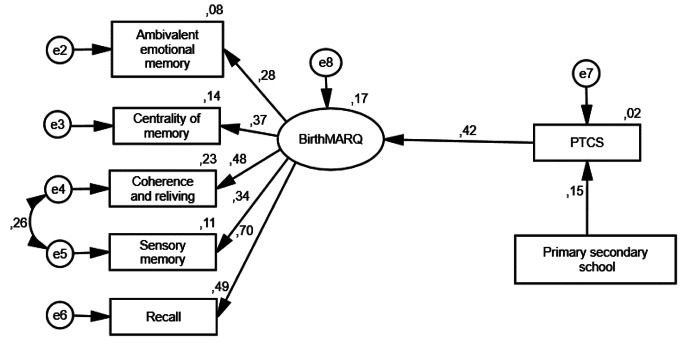

The data analysis was performed with IBM SPSS V20 (Chicago, USA) and AMOS 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analyses were presented as numbers, percentages, mean, standard deviation, median, and minimum and maximum values. One way ANOVA, İndependent samples T test, Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used in the analysis of the relationship of BirthMARQ and PTCS with some variables. Path analysis was performed to identify factors affecting BirthMARQ. BirthMARQ were considered as outcome variables. Perception of traumatic birth, age, education level, planned pregnancy, health problems during pregnancy and their mother’s perception of traumatic birth, time of birth, mode of delivery, health problems in the baby, and age of the baby were considered as independent variables. Categorical independent variables were transformed into dummy variables. Age, perception of traumatic birth, and baby’s age were considered as constant variables, and educational status (Primary secondary school (8 years): 1, High school and above: 0), planned pregnancy (No: 0, Yes: 1), health problems during pregnancy (No: 0, Yes: 1), mother’s perception of traumatic birth (No: 0, Yes: 1), time of birth (37 weeks and before: 1, 38 weeks and above: 0), type of delivery (normal birth: 0, cesarean section: 1), health problems in the baby (No: 0, Yes:1) were recorded. First, the baseline model that consisted of variables affecting BirthMARQ was tested (Fig. 1). Owing to the normal distribution of the data, a covariance matrix was created using the Maximum Likelihood calculation method. As a result of the analysis, the fit indices were not at acceptable levels. The insignificant variables were removed from the model and the analysis was repeated (Fig. 2). χ²/standard deviation, goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index, comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root means square residual, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)) fit indices were used. Statistical significance level was considered as p < 0.05.

Fig. 1.

Baseline Model

Fig. 2.

Standardized path coefficients in the revised model

Ethics approval

The ethics committee permission (Number: 2022/20–174) and institutional permission (Number: E-14567952-900-159822) of the study were obtained. Before the study, the purpose of the study was explained to the participants and their verbal consent was obtained.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

The study involved 285 women who were in a postpartum one-year period. The sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of the participants

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean, SD) | 28.7 | 5.39 |

| Education | ||

| Primary secondary school | 132 | 46.3 |

| High school | 64 | 22.5 |

| University and above | 89 | 31.2 |

| Working status | ||

| Working | 35 | 12.3 |

| Not working | 250 | 87.7 |

| Perceveid economic status | ||

| Poor | 41 | 14.4 |

| Medium | 193 | 67.7 |

| Good | 51 | 17.9 |

| Number of children | ||

| One | 108 | 37.9 |

| Two | 88 | 30.9 |

| Three and above | 89 | 31.2 |

| Planned pregnancy | ||

| No | 57 | 20 |

| Yes | 228 | 80 |

| Health problem during pregnancy | ||

| No | 201 | 70.5 |

| Yes | 84 | 29.5 |

| Health problems during pregnancy (n = 84)* | ||

| Risk of preterm labor | 16 | 5.6 |

| Covid 19 | 16 | 5.5 |

| Multiple pregnancy | 13 | 4.6 |

| Diabetes | 12 | 4.2 |

| Preeclampsia | 12 | 4.2 |

| Thyroid | 9 | 3.2 |

| Other (Hypertension, placenta previa, hyperemesis gravidarum, polyhydramnios, FMF, Toxoplasma) | 13 | 4.6 |

* More than one option has been ticked

A total of 71.2% of the participants gave birth at > 38 weeks of gestation, 37.2% delivered in a university hospital, and 47% delivered by planned cesarean Sect. 26.7% of the babies born had health problems (Table 2). 98.6% of the participants knew their mother’s birth story, 44.8% of the mothers of the participants gave birth at home, 95.4% had a normal delivery and 32.6% stated to their daughter, that the birth was difficult.

Table 2.

Postpartum characteristics of the participants

| Measures | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age of baby the interview (in weeks) | ||

| < 4 weeks | 65 | 22.8 |

| 5–12 | 55 | 19.3 |

| 13–24 | 52 | 18.2 |

| 25–36 | 40 | 14.0 |

| 37–48 | 73 | 25.6 |

| Postpartum care education | ||

| No | 192 | 67.4 |

| Yes | 93 | 32.6 |

| Type of delivery | ||

| Normal delivery without episiotomy | 13 | 4.5 |

| Normal delivery with episiotomy | 72 | 25.3 |

| Planned cesarean | 134 | 47.0 |

| Emergency cesarean | 66 | 23.2 |

| Person giving birth | ||

| Midwife | 50 | 17.5 |

| Doctor | 235 | 82.5 |

| Place of birth | ||

| Public hospital | 97 | 34 |

| Private hospital | 82 | 28.8 |

| University hospital | 106 | 37.2 |

| Weeks pregnant at delivery | ||

| 37th week or earlier | 82 | 28.8 |

| 38th or above | 203 | 71.2 |

| Gender of baby | ||

| Girls | 134 | 47 |

| Boys | 151 | 53 |

| Having health problems in the baby | ||

| No | 209 | 73.3 |

| Yes | 76 | 26.7 |

| Health problems in the baby* | ||

| Premature | 53 | 18.6 |

| Thyroid | 7 | 2.5 |

| Kidney problem | 5 | 1.8 |

| Heart problem | 3 | 1.1 |

|

Other (Hypoglycemia, intestinal knotting, ears closed, cyst on the head, hydrocephalus, Covid 19) |

9 | 3.4 |

| Persons receiving postpartum support* | ||

| Husband | 225 | 78.9 |

| Mother | 192 | 67.4 |

| Mother-in-law | 134 | 47.0 |

| Other (sister-in-law, neighbor, daughter) | 22 | 7.8 |

*More than one option has been ticked

The mean scores of the participants were 4.0 ± 0.8 for the BirthMARQ and 74.3 ± 27.7 for the PTCS, and a positive correlation was found between the scales (r = 0.306, p < 0.01). Among the BirthMARQ sub-dimensions, centrality of memory had the highest score and emotional memory had the lowest score (Table 3). In the study, it was determined that the rate of women with “high” and “very high” perception of traumatic birth was 45.9%.

Table 3.

Correlations between Birth Memory and Recall Scale score and Traumatic Birth Perception Scale score

| x̄ ± SD | M (Min-Max) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Total score of PTCS | 74.3 ± 27.7 | 76 (0- 130) | 1.000 | |||||||

| 2.Total score of BirthMARQ | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 4 (2- 6.3) | 0.306** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 3.Emotional memory | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 2.3 (1–7) | 0.171** | 0.245** | 1.000 | |||||

| 4.Ambivalent emotional memory | 4.2 ± 1.8 | 4 (1–7) | 0.206** | 0.413** | 0.308** | 1.000 | ||||

| 5.Centrality of memory | 4.8 ± 1.5 | 5 (1–7) | 0.123* | 0.518** | − 0.078 | 0.204** | 1.000 | |||

| 6.Coherence and reliving | 4.2 ± 1.3 | 4 (1–7) | 0.219** | 0.729** | − 0.013 | 0.078 | 0.159** | 1.000 | ||

| 7.Sensory memory | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 4 (1–7) | 0.056 | 0.575** | − 0.101 | 0.019 | 0.189** | 0.346** | 1.000 | |

| 8.Recall | 3.3 ± 2.0 | 3 (1–7) | 0.283** | 0.579** | 0.026 | 0.159** | 0.232** | 0.364** | 0.241** | 1.000 |

PTCS:Perception of Travmatic Childbirth Scale. BirthMARQ: The Birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire. x̄: Mean. SD: Standard deviation. M: Median. Min: Minimum value. Max: Maximum value

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Path analysis

The baseline model is presented in Fig. 1. When the fit values were examined in structural equation modeling, CMIN = 296.546, DF = 100, CMIN/DF = 2.965, RMSEA = 0.083, CFI = 0.412, and GFI = 0.869 were obtained. Since the GFI, CFI, RMSEA, and CMIN/DF values were not within the required limits, the correction indices were examined. In the model, since their path to PTCS was statistically nonsignificant, age, education level (primary secondary school), health problems in the baby, baby’s age, type of delivery (cesarean section), gestational age to BirthMARQ, age, education level (primary secondary school), planned pregnancy, health problems in pregnancy and their mother’s perception of traumatic birth were removed from the model and the structural equation model was re-established (Fig. 2). When the fit values were examined after exclusion, they were CMIN = 18.265, DF = 13, CMIN/DF = 1.405, RMSEA = 0.038, CFI = 0.965, and GFI = 0.982, respectively. All of the compliance criteria were obtained within the desired limits.

The path coefficients of emotional memory, ambivalent emotional memory, centrality of memory, coherence and reliving, sensory memory, and recall sub-dimensions under BirthMARQ were found to be statistically significant, and standardized values of these path coefficients were 0.279–0.698 (p < 0.001) (Table 4). Examinations of the determinants explaining BirthMARQ according to the model revealed that being a primary school graduate led to an increase of 0.148 units in the traumatic birth perception score (β = 0.148; p = 0.011). This indicates that primary school graduates have a higher perception of traumatic birth than those with higher education levels. An increase in the traumatic birth perception score leads to an increase of 0.416 units in the BirthMARQ score. Higher traumatic birth perception score in women leads to more negative birth memory and recall (β = 0.416; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2; Table 4). Perception of traumatic birth explained 17.3% of the variance in BirthMARQ score. Therefore, the model showed the effect of traumatic birth perception on birth memory and recall.

Table 4.

Path analysis results

| Measurement Model | β0 | β1 | SE | Test value | p | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambivalent emotional memory | <--- | BirthMARQ | 0.279 | 0.363 | 0.107 | 3.384 | < 0.001 | 0.078 |

| Centrality of memory | <--- | BirthMARQ | 0.368 | 0.387 | 0.093 | 4.145 | < 0.001 | 0.136 |

| Coherence and reliving | <--- | BirthMARQ | 0.475 | 0.448 | 0.096 | 4.667 | < 0.001 | 0.226 |

| Sensory memory | <--- | BirthMARQ | 0.335 | 0.352 | 0.095 | 3.703 | < 0.001 | 0.112 |

| Recall | <--- | BirthMARQ | 0.698 | 1 | 0.487 | |||

| Structural Model | ||||||||

| PTCS | <--- | Primary secondary school | 0.148 | 8.238 | 3.257 | 2.53 | 0.011 | 0.022 |

| BirthMARQ | <--- | PTCS | 0.416 | 0.021 | 0.004 | 5.355 | < 0.001 | 0.173 |

PTCS:Perception of Travmatic Childbirth Scale. BirthMARQ: The Birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire

The relationship between BirthMARQ and PTCS with some variables is presented in supplementary material 1 as a secondary analysis. The BirthMARQ score was associated with the presence of health problems during pregnancy, place of birth, gestational week at birth, and health problems in the baby (p = 0.034, p < 0.048, p < 0.037, and p < 0.018, respectively). The PTCS score was associated with educational status (p = 0.023) and place of birth (p = 0.032).

Discussion

This study was conducted to examine the relationship between women’s birth memories and recall and perception of traumatic birth in the postpartum one-year period and to determine the factors affecting them. In the study, it was determined that the women had a moderate level of birth memories and recall, and the rate of those with a “high” and “very high” perception of traumatic childbirth was 45.9%. The perception of traumatic birth was a predictor that explained 17.3% of birth memories and recall.

When the characteristics of women’s birth memories were examined, it was found that women experience more ambivalent feelings, their birth memories are more consistent and unfragmented, and their birth memories are at the center of their lives. Sensory memory, which includes sound, smell, taste, and touch, is at a moderate level. The results for ambivalent emotional memory, centrality of memory, and coherence and reliving are consistent with previous research findings (Kobya Yılmaz & Kılıç, 2022; Topkara & Çağan, 2020). In the study of Crawley et al. (2018), it was stated that women have moderate sensory memory, and their birth memories are quite consistent and central to their lives. Birth experience is a central event in most women, but it is emphasized that if it is experienced negatively, it can threaten self-perception in the role of motherhood (Thiel et al., 2021).

Birth experience has a significant impact on the health of mothers and babies, which can be experienced both positively and negatively (Elmir et al., 2010). For this reason, the factors that affect the positive memories of birth in the mind and the formation of positive emotions when she remembers her birth experience should be determined. In the present study, birth memory and recall scores were not affected by sociodemographic characteristics. Karakoç et al. (2022) also found that the total score of birth memory and recall was not related to educational status. However, the increase in age of mothers was reported to decrease the frequency of recalling birth memories (Karakoç et al., 2022). Another study found that women younger than 25 years had higher birth memory and recall scores (Altun & Kaplan, 2021). In their study, Thiel et al. (2021) found a negative correlation between education level and sensory memory and recall, and a negative correlation between age and centrality of memory. The affecting factors may arguably not be considered conclusive owing to reasons associated with the study design and the methodology used.

According to the results of this study, it was determined that as the PTCS score increased, birth memories and recall score increased, and the only predictor among the variables explaining BirthMARQ was PTCS. This finding is consistent with the results in the Crawley, Wilkie’s 2018. study with women who experienced traumatic births with more negative or mixed emotions, involuntary recall and reliving.

The perception of traumatic childbirth indicates that the woman evaluates the birth process and outcome subjectively and that her birth expectations are not met (Sorenson & Tschetter, 2010). In our study, 45.9% of the women had a “high” and “very high” perception of traumatic birth. According to the literature, women’s perception of traumatic childbirth was 33.8% in the study by Bay and Sayiner (2021), and 34% by Kobya Yılmaz and Kılıç (2022). To understand the perception of birth, it is important to know the factors affecting the perception of traumatic childbirth (Simpson & Catling, 2016). In our study, a higher level of perception of traumatic childbirth was found in those with low education level. The effect of education on the perception of traumatic childbirth is unclear in the literature; however, low education level increases the perception of traumatic childbirth (Anderson, 2017; Aydın et al., 2022; Yalniz Dilcen et al., 2022), Aktaş (2018) found that education had no effect. The place of delivery is another factor affecting the perception of traumatic childbirth. In this study, a higher perception of traumatic childbirth was determined in those who gave birth in a state hospital. Interactions with health professionals during birth can reportedly affect the birth experience (Harris & Ayers, 2012). In the study, the high number of applications to state hospitals and insufficient communication with health workers are thought to be affected.

According to the secondary analyses of this study, birth memories and recall scores of women who had health problems during pregnancy, those who gave birth at 37th gestational week and before, those who gave birth in a university hospital and those who had health problems in their babies were higher. Complications in the mother, the baby or both are factors that cause negative birth experience (Henriksen et al., 2017). It has been reported that the threat of death or serious injury during the coding of the birth experience affects memory characteristics (Crawley et al., 2018). It is expected that deviations from normal during pregnancy and childbirth negatively affect the mother and affect the general birth memory.

Limitations

This research has some limitations. First, mothers in the postpartum 1-year period were interviewed, and the data on birth memories and recall were questioned in the study. For this reason, the mother may have had difficulty remembering all the retrospective information and may have affected the research results. Second, in this study, BirthMARQ and PTCS were collected by self-report method. Since the Cronbach’s Alpha values of the scales were 0.74 and 0.85, respectively, it was assumed that this limitation was controlled. Third, although this study is of a descriptive and correlational type, the inclusion of the results of the path analysis will guide the control of factors influencing negative birth memories. Finally, the data obtained from the research can only represent the sample group, cannot be generalized.

Conclusion

Nearly half of the study participants perceived the experience of giving birth as traumatic, and birth memories and recall were at a moderate level. During labor, nurses and midwives should be aware of risk factors for traumatic birth. Since women with low education level may constitute a risk group in terms of traumatic birth, more support and care should be provided by nurses and midwives. Furthermore, perception of traumatic childbirth and negative retention in memory may affect mental health in the postpartum period. For this reason, emotional health of women should be supported during and after childbirth in addition to physical care so that birth memories are positive and they have positive emotions when they remember birth. In the study, we were able to explain 17% of birth memories and recall with the perception of traumatic childbirth. It is recommended to work with other variables to explain the rest of birth memories and recall. Since the experiences of women during the first postpartum year were questioned, it may have been difficult for the subjects to remember their experiences. Longitudinal studies are, therefore, recommended.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the women who participated in the study.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the 7th ?nternational 18th National Nursing Congress, 2022, Konya/TURKEY.

Data availability

The dataset is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committee permission (Number: 2022/20–174) and institutional permission (Number: E-14567952-900-159822) of the study were obtained. Before the study, the purpose of the study was explained to the participants and their verbal consent was obtained.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kamile Altuntuğ, Email: kaltuntug@yahoo.com.

Sibel Kiyak, Email: sibel_kiyak15@hotmail.com.

Emel Ege, Email: emelege@hotmail.com.

References

- Aktaş S. Multigravidas’ perceptions of traumatic childbirth: its relation to some factors, the effect of previous type of birth and experience. Medicine Sience. 2018;7(1):203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Altun, E., & Kaplan, S. (2021). Doğum Hafızasının ve Postpartum Posttravmatik Stres Bozukluğunun Anne-Bebekve Baba-Bebek Bağlanma Üzerine Etkisinin Değerlendirilmesi. Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt Üniversitesi Sağlık BilimleriEnstitüsü. Ankara.

- Anderson CA. The trauma of birth. Health Care for Women International. 2017;38(10):999–1010. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2017.1363208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydın R, Aktaş S, Binic DK. Vajinal Doğum Yapan Annelerin Doğuma İlişkin Travma Algısı İle maternal Bağlanma Düzeyi Arasındaki İlişkinin İncelenmesi: Bir Kesitsel Çalışma. Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi. 2022;11(1):158–169. doi: 10.37989/gumussagbil.1051454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers S. Delivery as a traumatic event: prevalence, risk factors, and treatment for postnatal posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Obstetrics And Gynecology. 2004;47(3):552–567. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000129919.00756.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos MH, Furuta M, Small R, McKenzie-Mcharg K, Bick D. Debriefing interventions for the prevention of psychological trauma in women following childbirth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd007194.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay F, Sayiner FD. Perception of traumatic childbirth of women and its relationship with postpartum depression. Women And Health. 2021;61(5):479–489. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2021.1927287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT, Watson S. Impact of birth trauma on breast-feeding: a tale of two pathways. Nursing Research. 2008;57(4):228–236. doi: 10.1097/01.Nnr.0000313494.87282.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AF, Andersson E. The birth experience and women’s postnatal depression: a systematic review. Midwifery. 2016;39:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley, R., Wilkie, S., Gamble, J., Creedy, D. K., Fenwick, J., Cockburn, N., & Ayers, S. (2018). Characteristics of memories for traumatic and nontraumatic birth. 32(5),584–591. 10.1002/acp.3438

- Elmir R, Schmied V, Wilkes L, Jackson D. Women’s perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth: a meta-ethnography. Journal Of Advanced Nursing. 2010;66(10):2142–2153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley S, Crawley R, Wilkie S, Ayers S. The birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire (BirthMARQ): development and evaluation. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14(1):211. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford E, Ayers S. Stressful events and support during birth: the effect on anxiety, mood and perceived control. Journal Of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23(2):260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthus-Niegel S, von Soest T, Vollrath ME, Eberhard-Gran M. The impact of subjective birth experiences on post-traumatic stress symptoms: a longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R., & Ayers, S. (2012). What makes labour and birth traumatic? A survey of intrapartum ‘hotspots’. Psychology & Health,27(10), 1166–1177. 10.1080/08870446.2011.649755 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hatamleh R, Sinclair M, Kernohan W, Bunting B. Birth memories of jordanian women: findings from qualitative data. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2013;18:235–244. doi: 10.1177/1744987112441911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Grimsrud E, Schei B, Lukasse M. Factors related to a negative birth experience – A mixed methods study. Midwifery. 2017;51:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann L, Banse R. Psychological aspects of childbirth: evidence for a birth-related mindset. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2021;51(1):124–151. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- İşbir GG, İnci F. Travmatik doğum ve hemşirelik yaklaşımları. Kadın Sağlığı Hemşireliği Dergisi. 2014;1(1):29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Karaçam Z, Akyüz E. Doğum eyleminde verilen destekleyici bakım ve ebe/hemşirenin rolü. Florence Nightingale Journal of Nursing. 2011;19(1):45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Karakoç H, Bekmezci E, Meram HE. The relationship between mothers’ birth memories and attachment styles. J Psy Nurs. 2022;13(4):306–315. doi: 10.14744/phd.2022.65982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Ford JH. Retrieval of emotional events from memory. Annu Rev Psychol. 2020;71:251–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-051123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3. Baskı). New York, NY: Guilford, 14, 1497–1513.

- Kobya Yılmaz, N., & Kılıç, M. (2022). Kadınların travmatik doğum algısının doğum hafızası ve hatırlama ile ilişkisi [yüksek lisans. Atatürk Üniversitesi]. Erzurum.

- Molloy E, Biggerstaff DL, Sidebotham P. A phenomenological exploration of parenting after birth trauma: mothers perceptions of the first year. Women And Birth. 2021;34(3):278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naim M, Katkov M, Romani S, Tsodyks M. Fundamental Law of Memory Recall. Physical Review Letters. 2020;124(1):018101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.018101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priddis HS, Keedle H, Dahlen H. The Perfect Storm of Trauma: the experiences of women who have experienced birth trauma and subsequently accessed residential parenting services in Australia. Women And Birth. 2018;31(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Almagro J, Hernández-Martínez A, Rodríguez-Almagro D, Quirós-García JM, Martínez-Galiano JM, Gómez-Salgado J. Women’s perceptions of living a traumatic childbirth experience and factors related to a birth experience. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health. 2019;16(9):1654. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16091654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL, Tekin E. Recognition memory: Tulving’s contributions and some new findings. Neuropsychologia. 2020;139:107350. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin P. Just another day in a woman’s life? Women’s long-term perceptions of their first birth experience. Part I Birth. 1991;18(4):203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1991.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson M, Catling C. Understanding psychological traumatic birth experiences: a literature review. Women and Birth. 2016;29(3):203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson DS, Tschetter L. Prevalence of negative birth perception, disaffirmation, perinatal trauma symptoms, and Depression among Postpartum Women. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2010;46(1):14–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2009.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadlmayr W, Amsler F, Lemola S, Stein S, Alt M, Bürgin D, Surbek D, Bitzer J. Memory of childbirth in the second year: the long-term effect of a negative birth experience and its modulation by the perceived intranatal relationship with caregivers. Journal Of Psychosomatic Obstetrics And Gynaecology. 2006;27(4):211–224. doi: 10.1080/01674820600804276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Størksen, H. T., Garthus-Niegel, S., Adams, S. S., Vangen, S., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2015). Fear of childbirth and elective caesarean section: a population-based study [Article]. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 10.1186/s12884-015-0655-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Takehara K, Noguchi M, Shimane T, Misago C. A longitudinal study of women’s memories of their childbirth experiences at five years postpartum. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14(1):221. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel F, Berman Z, Dishy GA, Chan SJ, Seth H, Tokala M, Pitman RK, Dekel S. Traumatic memories of childbirth relate to maternal postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal Of Anxiety Disorders. 2021;77:102342. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topkara, F. N., & Çağan, Ö. (2020). Examining Psychometric Properties of the Turkish Version of the Birth Memories and Recall Questionnaire. 0(0),0–0. 10.14744/phd.2020.60234

- Yalnız Dilcen H, Aslantekin F, Aktaş N. The relationship of psychosocial well-being and social support with pregnant women’s perceptions of traumatic childbirth. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2021;35(2):650–658. doi: 10.1111/scs.12887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalnız H, Canan F, Ekti Genç R, Kuloğlu MM, Geçici Ö. Travmatik doğum algısı ölçeğinin geliştirilmesi. Türk Tıp Dergisi. 2016;8(3):81–88. doi: 10.5505/ttd.2016.40427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.