Abstract

Myocardial infarction (MI) causes massive cell death due to restricted blood flow and oxygen deficiency. Rapid and sustained oxygen delivery following MI rescues cardiac cells and restores cardiac function. However, current oxygen-generating materials cannot be administered during acute MI stage without direct injection or suturing methods, both of which risk rupturing weakened heart tissue. Here, we present infarcted heart-targeting, oxygen-releasing nanoparticles capable of being delivered by intravenous injection at acute MI stage, and specifically accumulating in the infarcted heart. The nanoparticles can also be delivered before MI, then gather at the injured area after MI. We demonstrate that the nanoparticles, delivered either pre-MI or post-MI, enhance cardiac cell survival, stimulate angiogenesis, and suppress fibrosis without inducing substantial inflammation and reactive oxygen species overproduction. Our findings demonstrate that oxygen-delivering nanoparticles can provide a nonpharmacological solution to rescue the infarcted heart during acute MI and preserve heart function.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, controlled release of oxygen, nanoparticles, targeted delivery, myocardial repair

Graphical Abstract

Myocardial infarction (MI) is one of the most prevalent life-threatening diseases worldwide.1 In the US alone, approximately 800,000 people develop acute MI every year.2 Acute MI causes injuries to cardiac cells such as cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, due to disrupted blood supply and deficient oxygen and nutrient supplementation.3 Prolonged cardiac ischemia leads to irreversible cell death. Therefore, rescuing cardiac cells at an early stage of MI is necessary to preserve the myocardium and restore heart function.

Oxygen therapy has been widely studied to increase cell survival in the ischemic myocardium because it can raise the oxygen content in infarcted tissues and blood.4 Exogenous oxygen supports the survival and metabolism of cardiac cells during acute ischemia, and has the potential to limit the infarct size and reduce the risk of lethal arrhythmias. However, current oxygen therapies show inconsistent outcomes in preclinical and clinical studies. Inhalation of pure oxygen, a common clinical practice when treating acute MI, has been shown to improve oxygenation and reduce ischemic pain,5,6 but the clinical efficacy and safety of this treatment continues to be controversial and is limited by lack of effective alternatives.6,7 For example, hyperbaric oxygenation, which uses pure oxygen at >1 atm to increase oxygen tension to a normal or hyperoxic level,8 has demonstrated little or only modest impact on left ventricular ejection fraction following ischemia.9,10 Similarly, although artificial oxygen carriers based on microbubbles, hemoglobin or perfluorocarbons have shown some preclinical benefits,11–13 these systems cannot achieve sustained oxygen release, which is necessary for cell survival before establishment of angiogenesis. Moreover, there is currently no clinical evidence supporting these approaches to improve cardiac cell survival and heart function following acute MI. There is a critical need for oxygen delivery systems that can continuously supply oxygen to infarcted cardiac tissue after MI.

To address the current limitations of oxygen delivery in treating MI, we previously developed oxygen-generating microspheres that gradually release oxygen.14 The microspheres were encapsulated in a hydrogel to facilitate delivery via intramyocardial injection into the infarcted cardiac tissue. While these microspheres improved cardiac cell survival and heart function, the delivery approach had low potential for clinical translation as the intramyocardial injection at acute MI stage has serious concern for rupturing the already weakened cardiac tissue.15–17 Since the time window immediately after acute MI represents a critical time for supplying oxygen for myocardial rescue,18,19 a more ideal oxygen supply strategy would not only support extended release of oxygen but also be noninvasively administered into infarcted cardiac tissue.

Here we describe intravenously injectable nanoparticles that specifically accumulate in an infarcted heart and release oxygen during the acute MI stage. These nanoparticles can also be delivered intravenously before MI, and then specifically accumulate in the infarcted heart after MI. This pre-MI approach allows cardiac cells to more quickly acquire oxygen for survival than the post-MI delivery approach. Thus, it has greater potential for clinical translation. We observed that the nanoparticles, whether injected pre- or post-acute MI, facilitated rapid oxygen delivery, improved cardiac cell survival, and preserved cardiac function. Our findings provide a clinically feasible technology that has the potential for rapid translation for patients who suffer from acute MI.

RESULTS

Infarcted-Heart-Targeting, Oxygen-Releasing Nanoparticles Directly and Sustainably Released Molecular Oxygen, And Predominately Accumulated in Infarcted Cardiac Tissue Following Acute MI.

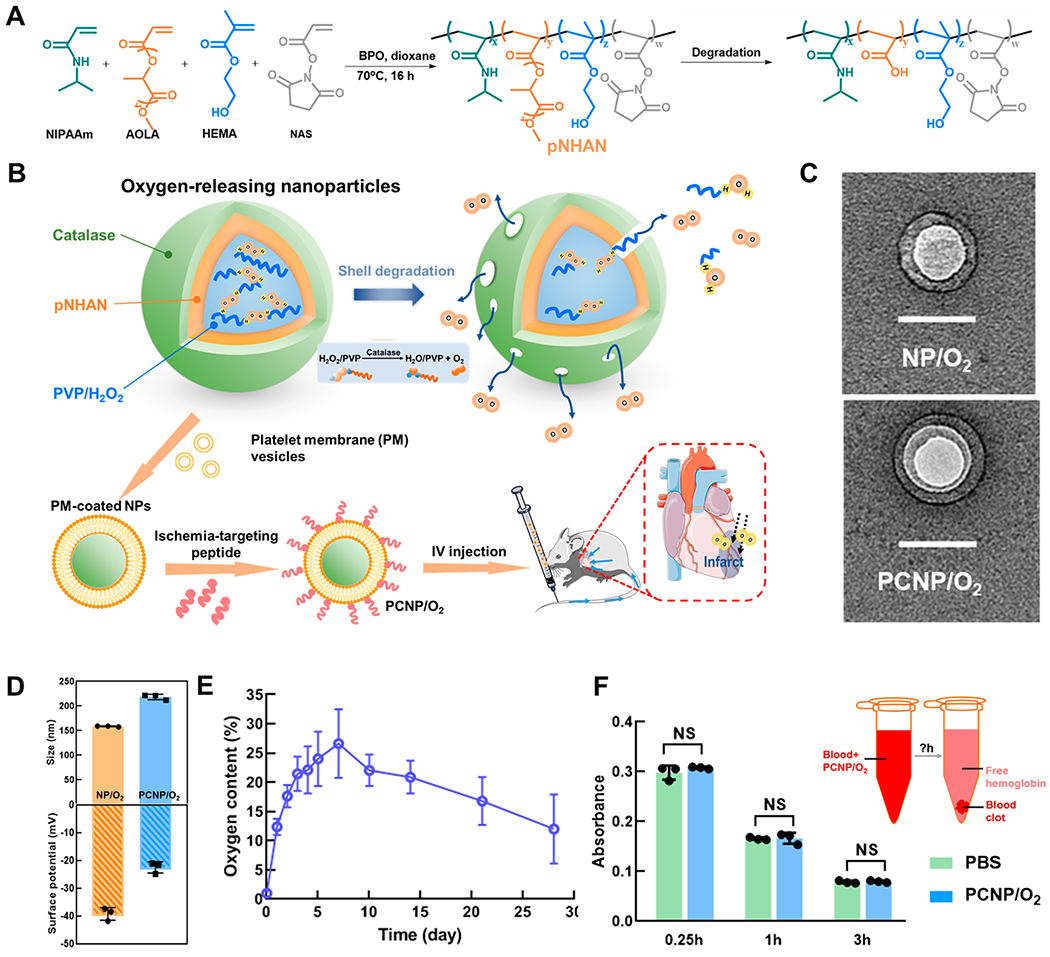

The oxygen-releasing nanoparticles were designed with a degradable polymer as the shell, and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)/hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) complex as the core (Figure 1A,B). The shell polymer was poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-acrylate-oligolactide-co-N-acryloxysuccinimide) (pNHAN) (Figure 1A). The chemical structure of the polymer was confirmed by 1H NMR (Figure S1A). The polymer was degradable with a weight loss of 26% after 4 weeks of incubation in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Figure S1B). The final degradation product exhibited a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) greater than 37 °C (Figure S1C), thus it can dissolve in the body fluid. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image confirmed the core–shell structure of the nanoparticle (NP/O2) (Figure 1C). The nanoparticles had a hydrodynamic diameter of 159 nm (Figure 1D). A layer of catalase was immobilized on the shell to timely and completely convert the H2O2, which was gradually released from the shell during shell degradation, into molecular oxygen at nanoparticle surface (Figure 1B). Successful catalase immobilization was confirmed by confocal images of the nanoparticles before and after conjugation with FITC-labeled catalase (Figure S2). The density of immobilized catalase was 0.27 mgCatalase/mgNanoparticles. The nanoparticles can continuously release oxygen for 4 weeks under 1% O2 condition, which mimics the infarcted cardiac tissue. The oxygen content reached ~12% after 24 h (Figure 1E). The release peaked at day 7 with an oxygen content of ~27%. The release rate decreased after 7 days but maintained an oxygen level above 10% for 4 weeks. The concentration of H2O2 in the release medium was less than 10 μM. Such concentration is much lower than the required dosage to trigger the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes20 and endothelial cells.21

Figure 1.

Design and characterization of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles. (A) Synthesis and degradation of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-acrylate-oligolactide-co-N-acryloxysuccinimide) (pNHAN). (B) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles and the release mechanism. (C) TEM images of the nanoparticles (NP/O2) and the platelet membrane coated, CST conjugated nanoparticles (PCNP/O2). Scale bar = 100 nm. (D) Hydrodynamic diameter and surface ζ potential of NP/O2 and PCNP/O2 (n = 3). (E) Oxygen release kinetics of the nanoparticles for 28 days (n = 5). (F) Thromboresistance test of PCNP/O2. After the blood was incubated with PCNP/O2 or DPBS, the absorbance of hemoglobin (540 nm) released from free red blood cells that were not in the blood clot was measured at 0.25, 1, and 3 h (n = 3). NS = not significant (P > 0.05).

To decrease the systemic clearance after intravenous (IV) injection, the nanoparticles were cloaked with platelet membrane (nonpro-thrombotic22,23) to “disguise” them. Platelet membrane can also prevent catalase from directly contacting with body fluid, thus keeping it bioactive. In addition, platelet membrane can separate catalase from H2O2 in the tissue so as to avert the effect of tissue H2O2 on the oxygen release from nanoparticles. To enable the nanoparticles to specifically target infarcted heart, the platelet membrane-cloaked nanoparticles were conjugated with peptide CSTSMLKAC (CST) that targets ischemia as confirmed previously.24–29 TEM images confirmed the successful coating of platelet membrane (Figure 1C). CST was conjugated on the nanoparticles at a density of 0.26 mgCST/mgNanoparticles. The platelet membrane coated, CST conjugated nanoparticles (PCNP/O2) had a hydrodynamic diameter of 218 nm (Figure 1D). The surface ζ potential of the PCNP/O2 was close to that of the platelet.30 The slightly negative surface charge makes the nanoparticles less likely to be taken up by cells via endocytosis, thus prolonging their half-life in circulation.31,32

Since the PCNP/O2 nanoparticles were designed to be delivered by IV injection, their blood compatibility was evaluated in terms of thromboresistance. We measured the absorbance of hemoglobin (540 nm) released from free red blood cells that were not in the blood clot after the blood was incubated with nanoparticles. Decreased hemoglobin absorbance is an indicator of blood clot formation.33 The blood incubated with nanoparticles exhibited similar hemoglobin absorbance as that incubated with DPBS after 0.25, 1, and 3 h (Figure 1F), proving that the nanoparticles had good blood compatibility.

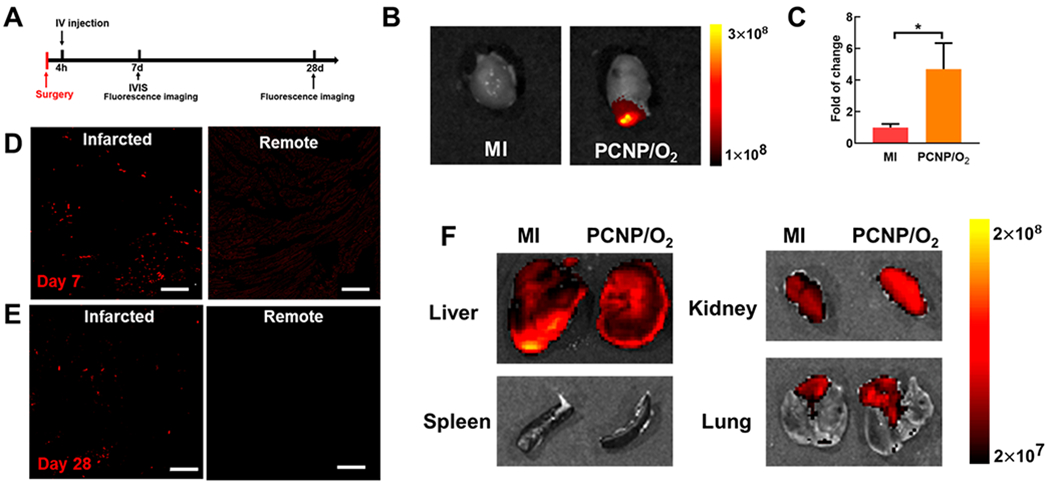

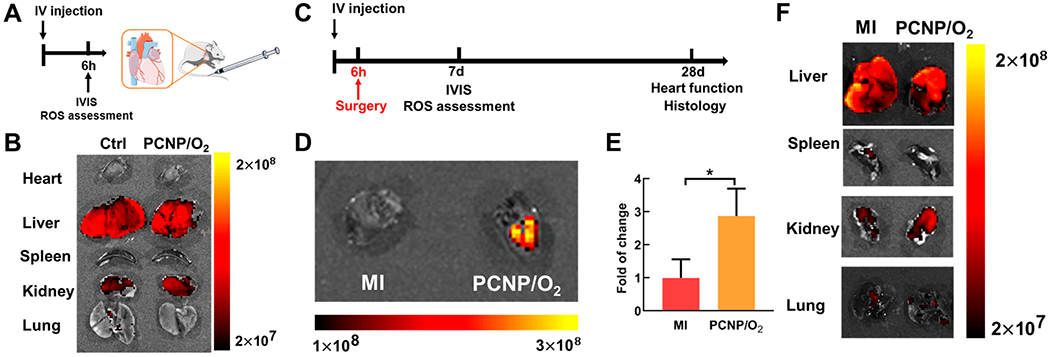

To test whether PCNP/O2 can target the infarcted hearts, the nanoparticles in which CST was labeled with rhodamine were injected intravenously into mice 4 h following MI (Figure 2A). After 7 days, IVIS imaging was used to determine the biodistribution of nanoparticles in the infarcted heart and major organs. Compared with the MI group without injection, a large number of nanoparticles accumulated in the infarcted heart apex region (Figure 2B), with >4 fold of increase in total flux than that of MI group (Figure 2C, P < 0.05). Confocal images of the cryosections showed that most of the nanoparticles were in the infarcted region rather than the uninjured remote region (Figure 2D). The PCNP/O2 nanoparticles were retained in the infarcted heart even after 28 days (Figure 2E), demonstrating that they had long-term retention time in the ischemic heart tissue. To determine the biodistribution of PCNP/O2 nanoparticles in major organs after 7 days of IV injection, IVIS images of liver, spleen, kidney, and lung were taken (Figure 2F). The group with nanoparticle injection showed similar signal intensity as the group without nanoparticle injection. Fluorescent images of these organ sections also confirmed that nanoparticles did not accumulate in liver, spleen, kidney, and lung 28 days after IV injection (Figure S3). The above results demonstrate that the PCNP/O2 nanoparticles specifically and efficiently targeted the infarcted heart with minimal off-target distribution in other organs. It is likely that the nanoparticles accumulated in the infarcted hearts through leaky vasculature.15,34

Figure 2.

Infarcted heart-targeting capability of PCNP/O2 delivered after MI. (A) Timeline for the animal study to examine the infarcted heart-targeting capability of the PCNP/O2. (B, C) IVIS images and quantification of the hearts harvested 7 days after MI surgery (n = 3). *P < 0.05. (D, E) Fluorescent images of the infarcted and remote regions of the myocardium 7 days (D) and 28 days (E) after surgery. Scale bar = 50 μm. (F) IVIS images of liver, spleen, kidney, and lung harvested 7 days after MI. Bronchi connected to the lung were not removed. It showed autofluorescence.

Sustained Oxygen Release from Nanoparticles Increased Cardiac Cell Survival, Promoted Endothelial Cell Morphogenesis, And Decreased Fibroblast Differentiation into Myofibroblast under Hypoxia Mimicking That of Infarcted Hearts.

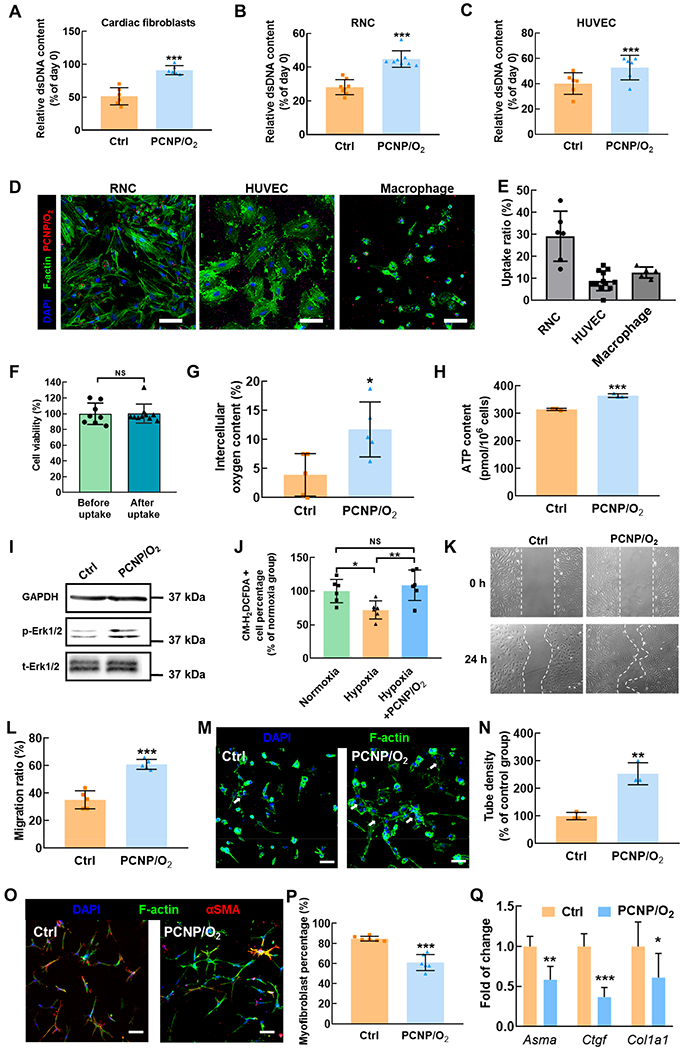

The hypoxic environment in the infarcted hearts causes extensive cardiac cell death. To determine whether the oxygen-releasing PCNP/O2 nanoparticles can augment cell survival under such conditions, we incubated rat cardiac fibroblasts, rat neonatal cardiomyocytes (RNCs), and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) with PCNP/O2 under 1% oxygen in serum-free media. Cardiac fibroblasts, cardiomyocytes, and endothelial cells represent major types of cells responsible for cardiac repair. The nanoparticles without oxygen release due to lack of PVP/H2O2 were used as control. Double stranded DNA (dsDNA) content was measured to quantify the number of live cells. After 5 days of culture, all three types of cells underwent massive cell death in the presence of nanoparticles without oxygen release (Figure 3A–C). Strikingly, PCNP/O2 significantly increased the survival of these cells (P < 0.001). Nanoparticles with or without being internalized by cells can release oxygen to increase cell survival. To determine how cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and macrophages internalized PCNP/O2 nanoparticles, we incubated PCNP/O2 with RNCs, HUVECs, and macrophages. After 2 h of incubation, 29% of RNCs, 9% of HUVECs, and 13% of macrophages internalized nanoparticles (Figure 3D,E). The uptake of nanoparticles did not impact mitochondrial viability of RNCs (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Effect of released oxygen on cardiac cell survival, endothelial cell morphogenesis, and fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblast under hypoxia. (A,B,C) Relative dsDNA content of cardiac fibroblasts (A), rat neonatal cardiomyocytes (RNC) (B) and HUVEC (C) after 5-day culture under 1% O2 with PCNP/O2 (n ≥ 6). The nanoparticles without oxygen release were used as control. (D) Fluorescent images of RNCs, HUVECs, and macrophages after taking up PCNP/O2. Scale bar = 50 μm. (E) Quantification of the uptake ratio. (F) RNC viability before and after taking up the nanoparticles without oxygen release (n ≥ 8). (G) Intracellular oxygen content in cardiac fibroblasts after 24-h culture under 1% O2 with and without PCNP/O2 (n = 5). (H) Intracellular ATP content in HUVEC after 24-h culture under 1% O2 with and without PCNP/O2 (n = 3). (I) Immunoblotting of phosphorylated and total Erk1/2 in cardiac fibroblasts cultured under 1% O2 for 24 h. GAPDH serves as a loading control. (J) ROS content in cardiac fibroblasts cultured under normoxia, hypoxia (1% O2), and hypoxia with PCNP/O2 for 5 days (n = 3). (K) Migration of HUVECs cultured under 1% O2 with and without PCNP/O2 (n = 4). (L) Quantification of migration ratio. (M) Endothelial cells tube formation. HUVECs were cultured under 1% O2 with and without PCNP/O2 for 24 h (n = 3). Nuclei and cytoplasm were stained with DAPI and F-actin, respectively. Scale bar = 50 μm. (N) Quantification of tube density. (O) Immunofluorescence staining of alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA, red) on cardiac fibroblasts cultured on collagen gel under 1% O2 for 24 h (n = 3). TGFβ1 was supplemented at a concentration of 5 ng/mL. Scale bar = 50 μm. (P) Quantification of αSMA positive myofibroblast density. (Q) Gene expression of Asma, Ctgf, and Col1a1 in cardiac fibroblasts cultured on collagen gel under 1% O2 for 24 h (n ≥ 5). Actb was used as a housekeeping gene. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We hypothesized that oxygen-augmented cell survival under hypoxia was likely due to increased cellular oxygen content. To evaluate this, we performed intracellular oxygen content measurements using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). After 24-h of incubation under 1% O2, cardiac fibroblasts in the medium without PCNP/O2 nanoparticles had a cellular oxygen level of 3.8%. The addition of PCNP/O2 nanoparticles significantly increased the cellular oxygen level to 11.8% (Figure 3G, P < 0.05). Oxygen is needed to produce energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for cell survival under hypoxic conditions. We performed an ATP assay to measure the cellular ATP content in HUVECs under hypoxia. The results demonstrated that the released oxygen significantly increased ATP levels in HUVECs (Figure 3H, P < 0.001).

Furthermore, we performed Western blot analysis of cardiac fibroblasts to evaluate the underlying signaling pathways associated with PCNP/O2-increased cell survival in the setting of hypoxia. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk1/2) is one of the major cascades of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathway, and is critical to regulate cell survival.35 We observed that Erk1/2 phosphorylation was more pronounced in the group with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles than the group with nanoparticles incapable of releasing oxygen (Figure 3I). These findings suggest that released oxygen activates Erk1/2 to augment cell survival under hypoxia.

One of the concerns of delivering oxygen to improve cell survival is the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can lead to cell apoptosis. To determine whether the released oxygen can cause ROS overproduction, we quantified cellular ROS content after treating cardiac fibroblasts with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles in the setting of hypoxia for 5 days (Figure S4 and Figure 3J). We observed that cellular ROS content increased after the cells were incubated with PCNP/O2, compared with the hypoxia only group (P < 0.01), but did not significantly increase compared to the cells cultured under normoxia (P > 0.05), indicating that the released oxygen did not substantially induce ROS overproduction.

Vascularization is critical for cardiac tissue repair after MI.36 To evaluate the potential of released oxygen in promoting vasculogenesis in the setting of hypoxia, we conducted an endothelial cell migration assay and an endothelial tube formation assay using HUVECs. The migration of HUVECs was significantly increased with the addition of PCNP/O2 nanoparticles (Figure 3K), with ~2-fold increase in migration ratio over the group without oxygen releasing nanoparticles after 24 h of culture under 1% O2 condition (Figure 3L, P < 0.001). Similarly, we observed significantly more endothelial lumens formed in the group treated with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles (Figure 3M, white arrows), with ~2.5 fold of increase compared to the control group (Figure 3N, P < 0.01). The oxygen release-enhanced endothelial tube formation under the extremely low oxygen and nutrient conditions mimicking that of the infarcted hearts possibly resulted from improved cell survival and migration. These results demonstrated that the released oxygen had the potential to stimulate vasculogenesis under ischemic conditions.

After MI, the upregulated transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) drives cardiac fibroblasts to differentiate into myofibroblasts under hypoxic conditions, leading to scar formation.37 To determine whether the released oxygen can attenuate myofibroblast formation, we seeded cardiac fibroblasts in a 3D collagen gel and cultured under 1% O2 condition in the medium supplemented with TGFβ1, and nanoparticles with or without oxygen release. We found that a significantly lower number of cardiac fibroblasts differentiated into myofibroblasts in the group with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles (Figure 3O,P, P < 0.001). At the mRNA level, the expression of myofibroblast markers such as Asma, Ctgf, and Col1a1 was significantly downregulated in the group with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles (Figure 3Q, P < 0.01 for Asma, P < 0.001 for Ctgf, P < 0.05 for Col1a1). These results demonstrated that the oxygen-releasing nanoparticles suppressed myofibroblast formation under hypoxia.

Oxygen-Releasing Nanoparticles Delivered at the Acute MI Stage Promoted Cardiac Repair.

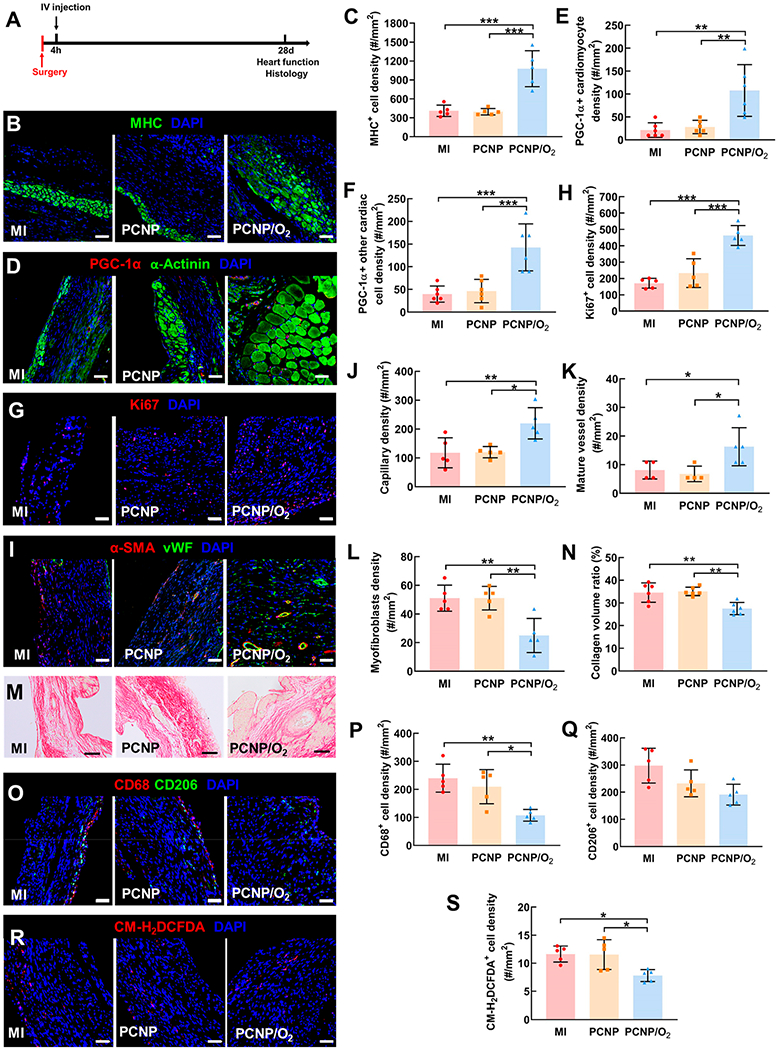

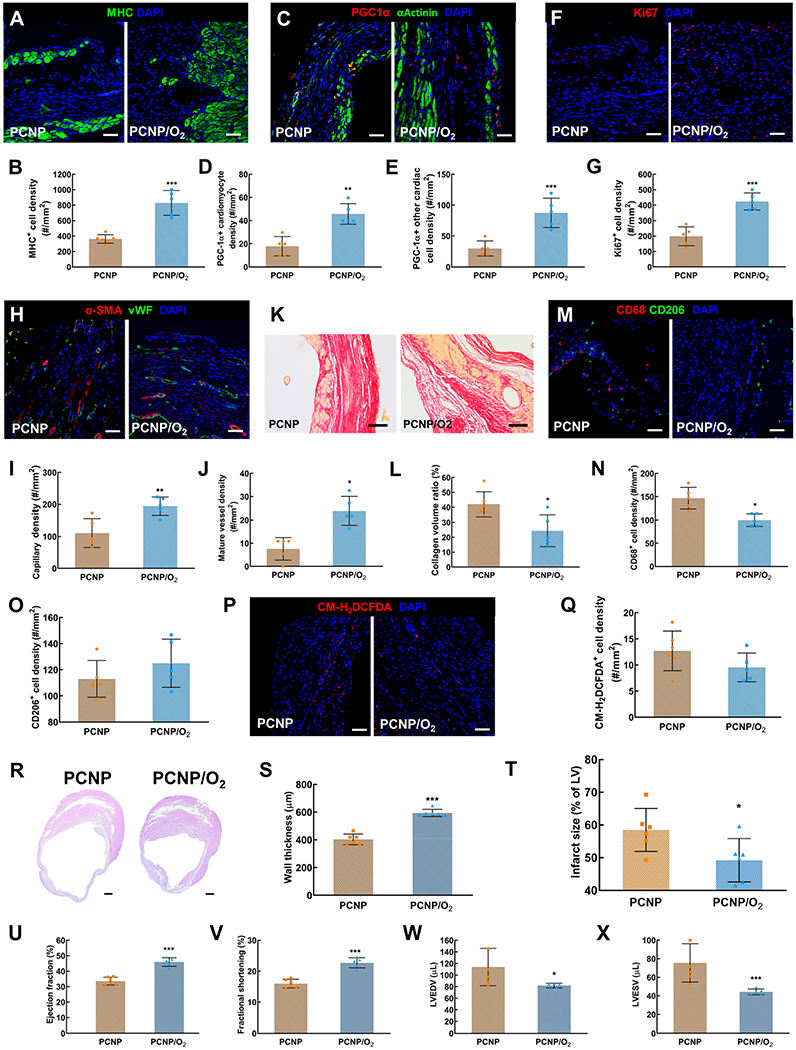

To determine whether targeted delivery of infarcted heart-targeting, oxygen-releasing nanoparticles during the acute MI stage can increase cardiac cell survival and tissue angiogenesis, and decrease cardiac fibrosis, leading to improvement of cardiac function, we injected PCNP/O2 nanoparticles intravenously into mice 4 h after acute MI induction (PCNP/O2 group) (Figure 4A). Control groups included a group injected with nanoparticles without oxygen release (PCNP group), and a group that underwent induction of acute MI only without nanoparticle injection (MI group). We observed that the oxygen released from the nanoparticles significantly improved cardiomyocyte survival in the infarcted region (Figure 4B). The density of myosin heavy chain (MHC) positive cardiomyocytes was 2.5-fold increased than the MI only and PCNP groups (Figure 4C, P < 0.001). The released oxygen also elevated mitochondrial biogenesis of the cardiomyocytes as the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) positive cardiomyocyte density was significantly increased (Figure 4D,E). In addition, the released oxygen augmented the proliferation and mitochondrial biogenesis of other cardiac cells in the infarcted region. The group injected with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles exhibited the highest density of PGC-1α positive cells (Figure 4F) and Ki67 positive cells (Figure 4G,H). These findings demonstrated that intravenous delivery of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles that target infarcted cardiac tissue can provide an augmented oxygen supply to boost the survival and proliferation of cardiac cells and largely rescue cardiomyocyte viability.

Figure 4.

Effect of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles on cell survival and metabolism, angiogenesis, cardiac fibrosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress after MI. (A) Timeline for the animal study. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of myosin heavy chain (MHC, green). Images were taken in the infarcted region of the heart 28 days after MI (same below). Scale bar = 50 μm (same below, unless otherwise specified). (C) Quantification of MHC positive cell density. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of PGC-1α (red) and α-Actinin (green). (E) Quantification of PGC-1α positive cardiomyocyte density. (F) Quantification of PGC1α positive cardiac cells (excluding cardiomyocytes) density. (G) Immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 (red). (H) Quantification of Ki67 positive cell density. (I) Immunofluorescence staining of αSMA (red) and vWF (green). (J) Quantification of capillary density. (K) Quantification of mature vessel density. (L) Quantification of myofibroblast density. (M) Picrosirius staining of the infarcted heart. Scale bar = 100 μm. (N) Quantification of the collagen volume ratio. (O) Immunofluorescence staining of CD68 (red) and CD206 (green). (P) Quantification of CD68 positive cell density. (Q) Quantification of CD206 positive cell density. (R) ROS staining using CM-H2DCFDA. (S) Quantification of CM-H2DCFDA positive cell density. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We also observed that improved cell survival and proliferation increased the density of capillaries and mature vessels in the infarcted region (Figure 4I). Mature vessels are characterized by an inner layer of endothelium (von Willebrand factor (vWF)+) and an outer layer of smooth muscle (alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA)+),38 while capillaries contain only vWF+ endothelium. In the group injected with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles, both capillary density and mature vessel density were significantly higher than that in the MI (P < 0.05) and PCNP (P < 0.05) groups (Figure 4J,K). It is possible that the surviving endothelial cells in the existing vasculature, and the endothelial cells migrating to the infarcted area participated in capillary and mature vessel formation. We also noted that the released oxygen impacted the extent of cardiac fibrosis (myofibroblast density and collagen content) in the infarcted cardiac region. The density of spindle-shaped αSMA positive myofibroblasts, that did not colocalized with endothelial cells, was significantly reduced following treatment with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles (Figure 4L). Suppressed myofibroblast formation was also associated with reduced collagen deposition in infarcted cardiac tissue (Figure 4M) as quantified from picrosirius red staining (Figure 4N, P < 0.01). These findings confirm that sustainable release of oxygen via our nanoparticles can reduce infarcted cardiac tissue fibrosis.

We investigated whether the injection of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles also impacted the inflammatory response in the infarcted cardiac tissue. CD68 and CD206 staining was performed to determine the densities of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophages, respectively (Figure 4O). The density of CD68 positive pro-inflammatory macrophages was reduced significantly after the treatment with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles (Figure 4P), demonstrating that the injected oxygen-releasing nanoparticles alleviated tissue inflammation in the infarcted heart. On the other hand, the treatment with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles did not promote the polarization of macrophages into anti-inflammatory phenotype as the density of CD206 positive macrophages was observed to be similar to MI and PCNP groups (P > 0.05, Figure 4Q). It is likely that the decrease of pro-inflammatory macrophage density is due to the mitigation of hypoxia by the released oxygen. Hypoxia is recognized to amplify the pro-inflammatory state of macrophages.39

A concern of delivering oxygen is the overproduction of ROS in infarcted hearts and other organs. Surprisingly, we observed a decrease of ROS content in the infarcted cardiac tissue following treatment with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles (Figure 4R) (P < 0.05, Figure 4S), indicating that the released oxygen reduced oxidative stress at the site of infarction. Superoxide is a common ROS that causes damage to cells. We measured superoxide content quantitatively in the infarcted heart 28 days after surgery. The superoxide concentration did not change significantly after injection of PCNP/O2 (Figure S5A). Reactive nitrogen species (RNS), especially peroxynitrite, can be generated from ROS to further increase oxidative stress. We found that the peroxynitrite content was similar in the MI group and PCNP/O2 group, demonstrating that the released oxygen did not lead to excessive RNS production (Figure S5B). Apart from heart, we also did not observe any evidence of gross tissue damage in the liver, spleen, kidney, or lung following intravenous administration of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles. ROS content in these organ tissues did not substantially increase (Figure S6), and the density of apoptotic cells also did not substantially increase (Figure S7).

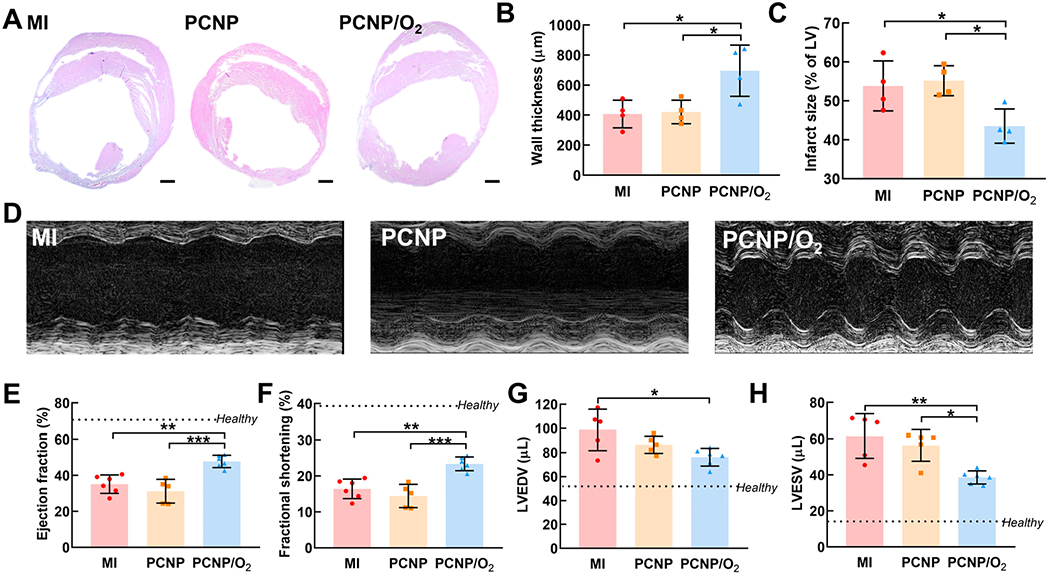

We also evaluated whether improved cell survival and proliferation, and enhanced tissue angiogenesis can impact cardiac wall thickness in the infarcted region following acute MI. After 4 weeks of treatment with PCNP/O2 nanoparticles, left ventricle (LV) wall thickness was significantly greater than that in the MI and PCNP groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 5A,B) and the infarct size was also reduced compared with MI and PCNP groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 5C). Consistent with wall thickness increase and infarct size decrease, cardiac function was also augmented after 4 weeks of treatment (Figure 5D). The PCNP/O2 group showed significantly higher left ventricular ejection fraction (EF, Figure 5E) and fractional shortening (FS, Figure 5F) compared with the MI and PCNP groups. In addition, the PCNP/O2 group had the lowest end-systolic volume (LVESV) and end-diastolic LV volume (LVEDV) (Figure 5G,H), which were closer to those of the healthy mouse without surgery. These results demonstrated that the continuous oxygen release from the nanoparticles delivered at the acute MI stage effectively alleviated LV dilatation and improved cardiac function.

Figure 5.

Oxygen-releasing nanoparticles delivered at acute MI stage increased wall thickness and augmented heart function. (A) H&E staining of the heart harvested 28 days after MI. Scale bar = 500 μm. (B) Quantification of left ventricle wall thickness. (C) Quantification of infarct size. (D to H) Echocardiographic analysis to assess heart function 28 days after MI. (D) Representative M-mode images and cardiac functional measurement including (E) ejection fraction (EF), (F) fractional shortening (FS), (G) left ventricle end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), and (H) left ventricle end-systolic volume (LVESV). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Oxygen-Releasing Nanoparticles Delivered Preacute MI Promoted Cardiac Repair Post-MI.

Since the oxygen-releasing nanoparticles delivered to the infarcted hearts at the acute MI stage showed promising outcomes, we further studied whether prophylactic administration of the nanoparticles preacute MI can promote cardiac repair. The rationale was that the nanoparticles injected into the circulation would accumulate in the infarcted heart following MI, thus providing oxygen earlier than injection of nanoparticles after MI. The nanoparticles were injected intravenously 6 h prior to MI after considering the time that symptoms appear before a heart attack,40 and the typical half-life of nanoparticles in the bloodstream.41,42 The nanoparticles in the circulation did not accumulate in the major organs including heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and lung after 6 h postadministration, and before induction of MI (Figure 6A,B). In addition, ROS content in these organs did not increase (Figure S8). Acute MI was induced 6 h after the injection (Figure 6C). After MI, the nanoparticles predominately accumulated in the infarcted cardiac tissue (Figure 6D,E), but not in the liver, spleen, kidney, and lung (Figure 6F). Notably, the ROS content in liver, spleen, kidney, and lung also did not increase (Figure S9). Also, since the oxygen release amount of PCNP/O2 peaked at day 7 (Figure 1E), we investigated if this amount would cause excessive oxidative stress in organs even when MI did not happen. We measured the ROS content in heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and lung in healthy mice and found similar ROS positive cell density between the control group and PCNP/O2 group (Figure S10).

Figure 6.

Infarcted heart-targeting capability of the oxygen-releasing nanoparticles delivered before MI. (A) Timeline for the animal study of PCNP/O2 biodistribution after intravenous injection. (B) IVIS images of major organs harvested 6 h after intravenous injection. No injection group was used as the control (Ctrl). (C) Timeline for the animal study of PCNP/O2 delivered before MI. (D,E) IVIS images and quantification of the heart harvested 7 days after MI (n = 3). P < 0.05. (F) IVIS images of major organs harvested 7 days after MI. Bronchi connected to the lung were removed.

The oxygen release from PCNP/O2 nanoparticles accumulated in the infarcted hearts correlated with cardiomyocyte survival (Figure 7A,B) and mitochondrial biogenesis (Figure 7C–E) following MI. It also promoted cell proliferation (Figure 7F,G), and stimulated the formation of blood vessels (Figure 7H–J). Moreover, it reduced collagen deposition in the infarcted region (Figure 7K,L), and decreased pro-inflammatory macrophage density (Figure 7M–O). The released oxygen did not raise oxidative stress in the infarcted myocardium (Figure 7P,Q).

Figure 7.

Effect of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles delivered before MI on cardiac repair following MI. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of myosin heavy chain (MHC, green). Images were taken in the infarcted region of the heart 28 days after MI (same below). (B) Quantification of MHC positive cell density. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of PGC1α (red) and α-Actinin (green). (D) Quantification of PGC1α positive cell density. (E) Quantification of PGC1α positive cardiac cells (excluding cardiomyocytes) density. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 (red). (G) Quantification of Ki67 positive cell density. (H) Immunofluorescence staining of αSMA (red) and vWF (green). (I) Quantification of capillary density. (J) Quantification of mature vessel density. (K) Picrosirius staining of the infarcted heart. (L) Quantification of the collagen volume ratio. (M) Immunofluorescence staining of CD68 (red) and CD206 (green). (N) Quantification of CD68 positive cell density. (O) Quantification of CD206 positive cell density. (P) ROS staining using CM-H2DCFDA. (Q) Quantification of CM-H2DCFDA positive cell density. (R) H&E staining of the heart harvested 28 days after MI. Scale bar = 500 μm. (S) Quantification of left ventricle wall thickness. (T) Quantification of infarct size. (U) to (X) Echocardiographic analysis to assess heart function 28 days after MI, including (U) ejection fraction (EF), (V) fractional shortening (FS), (W) left ventricle end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), and (X) left ventricle end-systolic volume (LVESV). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The prophylactic pre-MI delivery of PCNP/O2 nanoparticles significantly increased wall thickness of the infarct and decreased the infarct size (Figure 7R,S,T). Compared to the PCNP group, the heart function on the echocardiogram was largely improved, with a significant increase in left ventricular EF (Figure 7U) and FS (Figure 7V), and a significant decrease in LVEDV (Figure 7W) and LVESV (Figure 7X).

DISCUSSION

After MI, oxygen is urgently needed to rescue cardiac cells in the infarcted cardiac tissue where blood perfusion is poor and oxygen is locally deficient. Yet it remains challenging to continuously deliver sufficient oxygen to the infarcted hearts following MI. Clinical hyperbaric oxygen therapy is not effective in supplying enough oxygen to the impacted tissue over time. Approaches focusing on vascularizing infarcted heart tissue also cannot effectively rescue cardiac cells until revascularization is established. The acute MI stage represents a critical window for supplying oxygen to rescue cardiac cells,18,19 and an oxygen supply system that not only sustainably releases oxygen but also can be noninvasively administered would be highly feasible and have potential for clinical translation. Current widely adopted implantation approaches such as cardiac injection and suturing are not clinically appealing as they risk rupturing the already weakened infarct.15–17

In this work, we created infarcted heart-targeting, oxygen-releasing nanoparticles capable of being delivered by IV injection and specifically accumulating in the infarcted heart (Figure 1B, Figure 2B,C). The nanoparticles had PVP/H2O2 complex as core, and pNHAN as shell. PVP has a high molecular weight and can substantially decrease the diffusion rate of H2O2 when forming a stable complex with H2O2, thus allowing for controlled release. The shell was conjugated with catalase so as to convert the gradually released PVP/H2O2 complex at the nanoparticle surface to directly release molecular oxygen. It ensures that no free H2O2 escapes and damages the surrounding cells. The nanoparticles injected into the bloodstream diffused to the infarcted myocardium likely through vasculature bordering the infarcted area, and leaky vasculature in the infarct.43,44 The targeting capability of the nanoparticles can be attributed to the following: (1) the CST peptide targets the ischemic myocardium after MI45,46 and (2) the platelet membrane coated on the surface of the nanoparticles targets the injured endothelium.47 The nanoparticles show good biocompatibility and blood compatibility, low uptake ratio by macrophages, and minimal off-target accumulation in major organs. It is noteworthy that the fluorescence intensity of livers and kidneys in the IVIS images is higher than that of other organs (Figure 2F, 6B, and 6F). Given that there is no substantial difference between the fluorescence signal in the MI group and that in the PCNP/O2 group, this phenomenon is attributed to strong dsRed autofluorescence in tissues. In the future, using near-infrared fluorophores which have minimal tissue autofluorescence can resolve this issue.48

The oxygen-releasing nanoparticles developed in this work are better than those oxygen-releasing systems based on fluorinated compounds,49–51 H2O2 (without forming complex),52,53 CaO2,54–57 MgO2,58 and O2 microbubbles.59,60 First, our nanoparticles achieved 4-week continuous oxygen release, longer than most of the oxygen-releasing systems that typically release oxygen for less than 2 weeks. Second, our nanoparticle-based oxygen-releasing system is safer because no free and toxic H2O2 is released. Third, our system is more suitable for treating MI than the MgO2 and CaO2-based systems since it does not generate Mg2+ or Ca2+, which may lead to abnormal ion transients in the cardiomyocytes.61–63

We tested the therapeutic efficacy of delivering oxygen-releasing nanoparticles at the acute MI stage. Studies have confirmed that large amount of cell death occurs over the first 6–24 h after MI,3 and mortality rate within the first 24 h is 2.8%.64 Therefore, oxygen is in greatest demand shortly after MI. Thus, it is crucial to test the efficacy of the oxygen-releasing system administered in the early time window. Our animal studies demonstrated that one injection of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles 4 h after MI effectively enhanced cell survival and proliferation, stimulated angiogenesis, and restored heart function (Figures 4and 5). Notably, the oxygen-releasing nanoparticles neither substantially accumulated in major organs such as liver, spleen, kidney, and lung (Figure 2F), nor elevated ROS content in these organs (Figure S6).

The majority of individuals who are prone to MI exhibit symptoms of angina, chest pains, and/or shortness of breath.65 In these patients, prophylactic administration of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles may help circumvent ischemic complications of acute MI and rescue cardiac function. Because pre-MI delivery can more quickly provide oxygen for cardiac cell survival than post-MI delivery, this approach may also have greater potential for clinical translation. We studied the injection of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles 6 h before MI. Due to the platelet membrane coating that “disguises” the nanoparticles, PCNP/O2 did not substantially accumulate in the heart or other major organs, such as the liver, spleen, kidney, and lung (Figure 6B), and they did not increase the ROS content in these organs (Figure S8). After MI, the nanoparticles predominately accumulated in the infarcted hearts, but not in the liver, spleen, kidney, or lung (Figure 6D–F). Therefore, the nanoparticles delivered pre-MI and post-MI had similar targeting mechanism. The pre-MI delivery of nanoparticles with one injection also significantly promoted cardiac cell survival and proliferation, stimulated angiogenesis, and restored heart function (Figure 7). It is noteworthy that fewer nanoparticles had accumulated in the infarcted hearts after pre-MI injection, largely because some nanoparticles had been taken up by cells via endocytosis during circulation. Therefore, the therapeutic efficacy of pre-MI injection is lower than that of post-MI injection. Moreover, as the interval between pre-MI injection and MI occurrence increases, more nanoparticles may be cleared during the circulation. Hence the efficacy will decrease. Nevertheless, pre-MI treatment with oxygen-releasing nanoparticles presents an effective way to administer oxygen at the onset of symptoms. It takes effect immediately after the infarction begins to occur, and it has great translational potential.

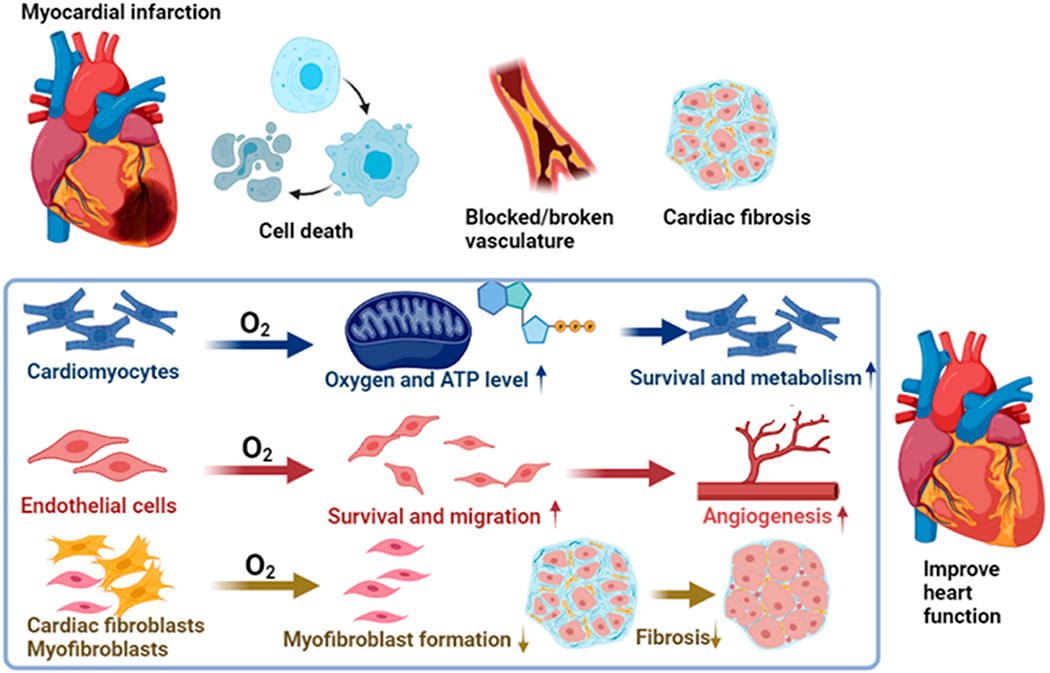

In this work, we also investigated the mechanism of the oxygen-releasing system to restore heart function (Figure 8): (1) The exogenous oxygen enhances the survival of cardiac cells under hypoxia by elevating cellular oxygen content and promoting ATP synthesis. The increased cell survival is associated with the activation of the Erk1/2 pathway. (2) The released oxygen stimulates endothelial tube formation to promote angiogenesis. (3) The released oxygen inhibits myofibroblast formation and suppresses cardiac fibrosis. (4) The released oxygen attenuated tissue inflammation by decreasing pro-inflammatory macrophage density and oxidative stress.

Figure 8.

Mechanism of oxygen-mediated cardiac repair and heart function restoration.

We acknowledge there are some limitations in this study. First, the work is limited to murine studies, which may not be completely representative of human pathophysiology. Future studies will use large animals to help develop the translation potential of this technology. Second, the nanoparticle concentration and injection volume need to be optimized for different animal models. Future advances in noninvasive oxygen content measurement in deep tissues may allow us to determine the actual oxygen content in the infarcted heart, and tailor the nanoparticle concentration and injection volume accordingly. Third, vascularization is required for long-term oxygen supply. While we demonstrate that delivery of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles at either the acute MI stage or pre-MI stage can rescue endothelial cells to re-establish microvascular angiogenesis, a higher level of revascularization would still be needed to facilitate longer-term cardiac health and function. In future studies, we plan to deliver oxygen-releasing nanoparticles and angiogenic growth factors at the acute MI stage. Despite these limitations, the current study presents an effective approach to promote cardiac repair after acute MI without pharmacological intervention. We anticipate that the minimally invasive delivery method can also be applied to release other biomolecules (growth factors, antibodies, and/or drugs) spatiotemporally pre- or postischemic myocardial insult to help facilitate rapid recovery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis and Characterization of the Polymeric Shell.

The polymer shell poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-acrylate-oligolactide-co-N-acryloxysuccinimide) (pNHAN) was synthesized as previously reported.66–68 Briefly, the monomers were dissolved in dioxane with a molar ratio of 50/5/25/20, and benzoyl peroxide was added as an initiator. The polymerization was conducted under nitrogen protection at 70 °C overnight. The polymer was precipitated in hexane and purified three times by dissolving in tetrahydrofuran and precipitating in ethyl ether. The obtained polymer was vacuum-dried and lyophilized before use. The chemical structure was confirmed by 1H NMR. The degradation of pNHAN was conducted in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) for 4 weeks. Briefly, the polymer was dissolved in dichloromethane and added into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube. After solvent evaporation, 200 μL of DPBS was added. The tube was placed in a 37 °C water bath. At each time point, the samples (n = 4) were taken out, washed with deionized (DI) water, and lyophilized. The sample weight was then measured. The percentage of weight remaining was calculated as weight at each time point normalized to the weight before degradation. The final degradation product of pNHAN was synthesized using the same method, with acrylic acid substituting acrylate oligolactide. The lower critical solution temperature of the final degradation product was measured by differential scanning calorimetry.

Fabrication of Nanoparticles.

The oxygen-releasing nanoparticles were fabricated by double emulsion. Briefly, the inner water phase was prepared by dissolving 0.24 g of PVP (40 kDa, Fisher Scientific) in 1 mL of 30% H2O2 (Fisher Scientific). The intermediate oil phase was prepared by dissolving pNHAN in dichloromethane at 4% w/v. Next, the water phase and the oil phase were mixed together with a volume ratio of 1:10, followed by sonication using an ultrasonicator (Cole Parmer) for 20 s. The water-in-oil emulsion was poured into 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) in water and emulsified again to yield water-in-oil-in-water double emulsion. Dichloromethane was allowed to evaporate by continuous stirring. The nanoparticles were collected by centrifugation at 12000g and washed 5 times with DI water to remove BSA. Finally, 10 mg/mL nanoparticles were mixed with 5 mg/mL bovine liver catalase (Sigma) in DI water and stirred at 4 °C for 4 h, followed by centrifugation and rinsing with DI water. To confirm catalase conjugation on the nanoparticles, catalase was prelabeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). The fluorescent images of the nanoparticles after catalase conjugation were taken by a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1200). Catalase conjugation density was calculated by a standard curve of fluorescent intensity versus catalase-FITC concentration.

Platelet Membrane Derivation and Cloaking.

Bovine blood (Quad Five) was centrifuged at 200g for 25 min. The platelet rich plasma was extracted and centrifuged at 250g for 25 min. The blood cells were pelleted and removed, while the plasma was purified by adding DPBS containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and prostaglandin E1 (Sigma) to prevent platelet activation. Then, the platelets were pelleted by centrifugation at 800g for 25 min and suspended in DPBS containing EDTA and protease inhibitors (Thermo Fisher). Platelet membrane vesicles were derived by performing 3–4 freeze–thaw cycles on the platelet suspension and collected by centrifugation at 4500g for 5 min. The membrane vesicles were washed with DPBS containing protease inhibitors and sonicated using an ultrasonic bath (130W, Fisher Scientific) for 5 min. To cloak platelet membrane onto the nanoparticles, 10 mg of oxygen-releasing nanoparticles were mixed with the membrane vesicles derived from 2 × 1010 platelets and sonicated for 5 min. The size and surface zeta potential of the nanoparticles before and after cloaking were measured by dynamic light scattering (Malvern ZEN3600) where the nanoparticles were suspended in water. The morphology was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit) where the dry nanoparticles were used.

Conjugation of Infarcted Heart-Targeting Peptide CST.

CST conjugation was conducted as previously reported.69 Briefly, the platelet-membrane cloaked nanoparticles were mixed with 2.5 mM suberic acid bis(N-hydroxysuccinimide ester) in 25 mM NaH2PO4 aqueous solution. CST peptide was added (mCST/mNP = 1:1), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. Then, the reaction was terminated by glycine, and the mixture was dialyzed against DI water overnight. The nanoparticles were lyophilized and stored at −20 °C.

Oxygen Release Kinetics.

The oxygen release kinetics was measured by a previously reported method.66,67 Briefly, the nanoparticles were dispersed in DPBS at a concentration of 10 mg/mL (n = 5) and added to a 96-well plate coated with oxygen-permeable polydimethylsiloxane membrane. The membrane was loaded with an oxygen-sensitive dye (Ru(Ph2phen3)2Cl2) and an oxygen-insensitive dye rhodamine B. The fluorescence intensity of both dyes was measured at each time point using a plate reader (SpectraMax iD3). The fluorescence intensity of Ru(Ph2phen3)2Cl2 was normalized to that of rhodamine B. The oxygen level was calculated from a calibration curve. The free H2O2 concentration in the release medium was measured by a quantitative peroxide assay kit (Thermo Fisher).

Blood Compatibility Assay.

The blood compatibility of the nanoparticles was examined in terms of thromboresistance according to a published method.33,69 Briefly, 200 μL of bovine blood was mixed with 125 μL of DPBS or DPBS containing 10 mg/mL PCNP/O2 (n = 3 for each group) at 37 °C. CaCl2 (0.1 M) was added to initialize blood clotting. At 0.25, 1, and 3 h, the mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was dispersed in DI water to release hemoglobin. The hemoglobin was released from the free red blood cells that were not trapped in the blood clot. The absorbance of hemoglobin was measured at 540 nm by a plate reader (SpectraMax iD3).

Cell Culture.

Rat neonatal cardiomyocytes (RNC, Lonza) were cultured using the medium suggested by the vendor supplemented with 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine. Rat cardiac fibroblasts (Cell Applications) were cultured using Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC, Lonza) were cultured using the medium suggested by the vendor. Macrophages were differentiated from monocytes. THP-1 monocytic cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS (ATCC). For M1 phenotype macrophage differentiation, THP-1 cells were incubated with 100 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 days followed by a replacement of full culture medium. After 24 h, the cells were treated with 20 ng/mL IFN-gamma (R&D Systems) and 10 pg/mL LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) for another 48 h. Cells were cultured in normoxic incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C).

Cell Survival Assay.

RNCs, cardiac fibroblasts, and HUVECs were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 104/well. Nanoparticles with and without oxygen release were added to the wells. To mimic the ischemic environment, the cells were cultured in a hypoxic incubator (1% O2, 5% CO2, 37 °C) with no serum supplemented in the culture media. After 5 days, the medium was removed, and the cells were incubated with papain (Fisher Scientific) at 60 °C overnight. The dsDNA content was measured by Picogreen dsDNA assay kit (Invitrogen) and normalized to that on day 0 (n ≥ 6 for each group).

Cellular Uptake Assay.

For the cellular uptake assay, 10 mg/mL PCNP/O2 were incubated with cells seeded in collagen-coated 96-well plates for 2 h. Then, the cells were washed, fixed, blocked, and stained with F-actin (Abcam) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma). Images were taken by a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1200). The uptake ratio was calculated as the percentage of cells with nanoparticle uptake. The cell viability after uptake was also examined. RNCs were incubated with PCNP without oxygen release for 2 h, and the viability was measured by MTT assay (n ≥ 8).

Cellular Oxygen Content Measurement.

To determine the intracellular oxygen content, rat cardiac fibroblasts were incubated with lithium phthalocyanine (LiPc) nanoparticles for 2 h to allow cellular uptake. The residual LiPc nanoparticles were washed with DPBS for 3 times. After trypsinization, the cells were seeded in collagen-coated EPR tubes (Wilmad-LabGlass, n = 5 for each group) with or without PCNP/O2 (10 mg/mL). The EPR tubes were placed in a hypoxic incubator (1% O2, 37 °C) for 4 h for gas balance. After that, the tubes were sealed and incubated for 24 h under 1% O2. The EPR spectrum was recorded using an X-band EPR instrument (Bruker). The parameters used in this experiment were 0.1 mW for microwave power, 1.0 db for attenuation, and 9.8 GHz for frequency, following our reported method.70 Oxygen content (%) was calculated from the line width of the spectrum using a calibration curve.

Cellular ATP Level Measurement.

To determine the intracellular ATP level, HUVECs were cultured in a 6-well plate to reach 85–95% confluence. The culture media was then replaced with serum-free media with or without PCNP/O2 (10 mg/mL). After 24-h incubation under 1% O2, the cells were lysed (n = 3 for each group) and the ATP content was measured by an ATP assay kit per manufacturer’s instruction (Millipore Sigma).

Western Blots.

Protein lysates were collected from cardiac fibroblasts after incubation under 1% O2 for 24 h and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Low-fluorescence polyvinylidene fluoride (LF-PVDF) membranes (Biorad) were used to transfer the proteins at 4 °C overnight, followed by blocking and incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C. The blots were washed with DPBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and incubated with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoblots were detected by a detection kit from Advansta and imaged using ChemiDoc XRS+ System (Biorad). The primary antibodies used were anti-GAPDH (1:4000, Abcam), antiphospho-Erk1/2 (1:500, Cell Signaling), and anti-Erk1/2 (1:1000, Cell Signaling).

Cellular ROS Content Measurement.

To measure intracellular ROS content, rat cardiac fibroblasts were prestained with ROS sensitive dye CM-H2DCFDA and cultured with serum-free medium with or without 10 mg/mL PCNP/O2 (n = 3 for each group). After 5 days of culture, the cells were fixed and stained with DAPI. Fluorescent images were taken using a confocal microscope. The CM-H2DCFDA positive cell density was quantified, and then normalized to the CM-H2DCFDA positive cell density cultured under normoxia.

Endothelial Cell Migration Assay.

HUVECs were cultured in a 6-well plate to reach 85–95% confluence (n = 4 for each group). The monolayer was then scraped with a 200 μL pipet tip, washed, and supplemented with serum-free medium with or without 10 mg/mL PCNP/O2. After 24 h, images were taken by an optical microscope (Olympus IX70). The distances between two sides of the scratch were measured by ImageJ. The migration ratio was calculated as migration ratio % = {[(interval at 0 h) − (interval at 24 h)]/(interval at 0 h)} × 100.

Endothelial Tube Formation Assay.

HUVECs were seeded into a 3D collagen gel at a density of 8 × 105 cells/mL. The cells were cultured in serum-free medium with or without supplement of PCNP/O2 (10 mg/mL) under 1% O2 condition (n = 3 for each group). After 24 h, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 50 min and stained with phalloidin-488 and DAPI. Fluorescence images were taken using a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1200). Based on the phalloidin staining, the density of lumens was counted for each group and normalized to that in the control group without supplement of PCNP/O2.

Immunofluorescence Analysis and Gene Expression of Cardiac Fibroblasts.

Rat cardiac fibroblasts were seeded into a 3D collagen gel at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL. The cells were cultured in serum-free medium with or without supplement of PCNP/O2 (10 mg/mL) under 1% O2 condition (n = 3 for each group). After 24 h, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with anti-α-SMA, phalloidin-488 and DAPI. Fluorescence images were taken in Z-stack mode using a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1200). To determine gene expression, RNA was isolated from the rat cardiac fibroblasts by TRIzol following manufacturer’s instruction. cDNA was synthesized using high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Thermo Fisher). Gene expression was performed by real-time RT-PCR using SYBR green (Invitrogen) and selected primer pairs for Asma, Ctgf, and Col1a1 (Table S1). Actb was used as a housekeeping gene. Data analysis was performed using the ΔΔCt method (n ≥ 5 for each group).

Animal Model.

All animal care and experiment procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines. The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University in St. Louis. Female 8-week-old C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories) were used in this study. Myocardial infarction was induced by the operative placement of a permanent occlusion around the left anterior descending artery. For post-MI treatment study, animals were randomized into three groups: (1) MI surgery only; (2) mice with MI surgery and injected with nanoparticles that cannot release oxygen (PCNP group); (3) mice with MI surgery and injected with oxygen-releasing nanoparticles (PCNP/O2 group). For groups injected with nanoparticles, the nanoparticles were first dispersed in DPBS at a concentration of 10 mg/mL, and then intravenously injected into mice (100 μL per mouse) 4 h after the MI surgery (n ≥ 5 for each group). For pre-MI treatment study, the nanoparticles were intravenously injected into mice (100 μL per mouse) 6 h before the MI surgery (n ≥ 5 for each group).

Ex Vivo Fluorescence Imaging.

For post-MI treatment studies, animals were euthanized 7 days after the surgery, and their heart, lung, liver, spleen, and kidney were collected to examine the targeting effect of the nanoparticles. For pre-MI treatment studies, the heart, lung, liver, spleen, and kidney were collected after 6 h of injection (before MI surgery), and 7 days after MI surgery, respectively. Images were taken using IVIS spectrumCT imaging system (PerkinElmer) with dsRed emission filter.

Cardiac Function Assessment.

Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of isoflurane and oxygen. An echocardiogram was performed using Vevo 2100 ultrasound system (Fujifilm). M-mode measurements in long axis view of the left ventricle (LV) was used to calculate the LV end-systolic volume (LVESV) and LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) using the Teichholz formula: LV volume = 7.0 × D3/(2.4 + D), where D is the diameter at end-systolic or end-diastolic cardiac phase. Fractional shortening (FS) is calculated by measuring the percentage change in diameter during systole and diastole. Ejection fraction (EF) % = (LVEDV − LVESV)/LVEDV × 100.

Tissue Superoxide and Peroxynitrite Content Measurement.

For post-MI injection experiments, the hearts were harvested 28 days after surgery. Within each group, 50 mg of tissues was homogenized, and the concentrations of superoxide anions and peroxynitrite were measured by Superoxide Anion Microplate Assay Kit (MyBioSource) and Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) ELISA Kit (MyBioSource), respectively, following instructions from the manufacturer.

Histology and Immunofluorescence Staining.

Heart sections were deparaffinized, permeabilized, blocked, and incubated with rabbit antialpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, Abcam, 1:300), mouse anti-Von Willebrand factor (vWF, Abcam, 1:300), rabbit anti-CD31 (Abcam, 1:100), mouse anti-α-SMA (Abcam, 1:200), mouse antimyosin heavy chain (MHC, R&D, 1:50), rat anti-Ki67 (Thermo Fisher, 1:250), mouse anti-α-actinin (Sigma, 1:200), rabbit anti-PGC1α (Abcam, 1:300), rabbit anti-CD68 (Abcam, 1:500), mouse anti-CD206 (Abcam, 1:500) or CM-H2DCFDA (Thermo Fisher, 1:150) overnight at 4 °C. Corresponding secondary antibodies were stained for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Fluorescent images were taken by a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1200). Hematoxylin and eosin staining, picrosirius red staining, and TUNEL staining were also performed.

Statistical Analysis.

All results were presented as mean ± standard deviation. One-way ANOVA test with Tukey’s posthoc correction was used for statistical analysis. A p-value (P) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Confocal imaging was performed in part through the use of Washington University Center for Cellular Imaging (WUCCI) supported by Washington University School of Medicine, The Children’s Discovery Institute of Washington University, St. Louis Children’s Hospital (CDI-CORE-2015-505 and CDI-CORE-2019-813), and the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital (3770 and 4642). We thank the Mouse Cardiovascular Phenotyping Core in Washington University School of Medicine for the mouse myocardial infarction surgery. We thank the Musculoskeletal Research Center in Washington University School of Medicine for help with histological sections. We thank the Molecular Imaging Center in Washington University School of Medicine for help with IVIS imaging. We thank M. Singh from the Department of Chemistry in Washington University for help with EPR test. Schematics in ToC graphic and Figure 8 were created with BioRender.com. We thank InPrint and J. Ballard from the Engineering Communication Center in Washington University for editing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health (R01HL138175, R01HL138353, R01EB022018, R01AG056919, R01HL153262, R01HL164062, and R01DK133949).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.2c10043.

Primer sequence used in real-time RT-PCR, polymer synthesis and characterization, validation of catalase conjugation, nanoparticles distribution in major organs, ROS staining of cardiac fibroblasts, in vivo superoxide anion and peroxynitrite content measurement, in vivo ROS content in different organs at different time points, in vivo TUNEL staining (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsnano.2c10043

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Ya Guan, Institute of Materials Science and Engineering, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, United States.

Hong Niu, Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, United States.

Jiaxing Wen, Institute of Materials Science and Engineering, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, United States.

Yu Dang, Institute of Materials Science and Engineering, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, United States.

Mohamed Zayed, Department of Surgery, Section of Vascular Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, United States; Department of Radiology and Division of Molecular Cell Biology, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, United States; Department of Biomedical Engineering, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, United States; St. Louis Veterans Affairs, St. Louis, Missouri 63106, United States.

Jianjun Guan, Institute of Materials Science and Engineering, Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, and Department of Biomedical Engineering, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392 (10159), 1736–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Fryar CD; Chen T-C; Li X Prevalence of uncontrolled risk factors for cardiovascular disease: United States, 1999–2010. NCHS Data Br. 2012, 103, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Konstantinidis K; Whelan RS; Kitsis RN Mechanisms of cell death in heart disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 2012, 32 (7), 1552–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shuvy M; Atar D; Gabriel Steg P; Halvorsen S; Jolly S; Yusuf S; Lotan C Oxygen therapy in acute coronary syndrome: are the benefits worth the risk? Eur. Heart J 2013, 34 (22), 1630–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Raut MS; Maheshwari A Oxygen supplementation in acute myocardial infarction: To be or not to be? Ann. Card. Anaesth 2016, 19 (2), 342–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Burls A; Emparanza JI; Quinn T; Cabello JB Oxygen use in acute myocardial infarction: an online survey of health professionals’ practice and beliefs. Emerg. Med. J 2010, 27 (4), 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kones R Oxygen therapy for acute myocardial infarction—then and now. A century of uncertainty. Am. J. Med 2011, 124 (11), 1000–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Stavitsky Y; Shandling AH; Ellestad MH; Hart GB; van Natta B; Messenger JC; Strauss M; Dekleva MN; Alexander JM; Mattice M; Clarke D Hyperbaric oxygen and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction: the ‘HOT MI’randomized multicenter study. Cardiology 1998, 90 (2), 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Dekleva M; Neskovic A; Vlahovic A; Putnikovic B; Beleslin B; Ostojic M Adjunctive effect of hyperbaric oxygen treatment after thrombolysis on left ventricular function in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J 2004, 148 (4), e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Vlahović A; Nešković AN; Dekleva M; Putniković B; Popović ZB; Otašević P; Ostojić M Hyperbaric oxygen treatment does not affect left ventricular chamber stiffness after myocardial infarction treated with thrombolysis. Am. Heart J 2004, 148 (1), e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Natanson C; Kern SJ; Lurie P; Banks SM; Wolfe SM Cell-free hemoglobin-based blood substitutes and risk of myocardial infarction and death: a meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. JAMA 2008, 299 (19), 2304–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Spahn DR Artificial oxygen carriers: a new future? Crit. Care 2018, 22, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kheir JN; Scharp LA; Borden MA; Swanson EJ; Loxley A; Reese JH; Black KJ; Velazquez LA; Thomson LM; Walsh BK; Mullen KE; Graham DA; Lawlor MW; Brugnara C; Bell DC; McGowan FX Oxygen gas–filled microparticles provide intravenous oxygen delivery. Sci. Transl. Med 2012, 4 (140), 140ra88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Fan Z; Xu Z; Niu H; Gao N; Guan Y; Li C; Dang Y; Cui X; Liu XL; Duan Y; Li H; Zhou X; Lin P-H; Ma J; Guan J An injectable oxygen release system to augment cell survival and promote cardiac repair following myocardial infarction. Sci. Rep 2018, 8 (1), 1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Nguyen MM; Carlini AS; Chien MP; Sonnenberg S; Luo C; Braden RL; Osborn KG; Li Y; Gianneschi NC; Christman KL Enzyme-Responsive Nanoparticles for Targeted Accumulation and Prolonged Retention in Heart Tissue after Myocardial Infarction. Adv. Mater 2015, 27 (37), 5547–5552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Johnson TD; Christman KL Injectable hydrogel therapies and their delivery strategies for treating myocardial infarction. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2013, 10 (1), 59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ungerleider JL; Christman KL Concise review: injectable biomaterials for the treatment of myocardial infarction and peripheral artery disease: translational challenges and progress. Stem Cells Transl. Med 2014, 3 (9), 1090–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kenmure A; Murdoch W; Beattie A; Marshall J; Cameron A Circulatory and metabolic effects of oxygen in myocardial infarction. Br. Med. J 1968, 4 (5627), 360–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Prabhat AM; Kuppusamy ML; Naidu SK; Meduru S; Reddy PT; Dominic A; Khan M; Rivera BK; Kuppusamy P Supplemental oxygen protects heart against acute myocardial infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med 2018, 5, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Piao H; Takahashi K; Yamaguchi Y; Wang C; Liu K; Naruse K Transient receptor potential melastatin-4 is involved in hypoxia-reoxygenation injury in the cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 2015, 10 (4), No. e0121703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Cossu A; Posadino AM; Giordo R; Emanueli C; Sanguinetti AM; Piscopo A; Poiana M; Capobianco G; Piga A; Pintus G Apricot melanoidins prevent oxidative endothelial cell death by counteracting mitochondrial oxidation and membrane depolarization. PLoS One 2012, 7 (11), No. e48817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tang J; Su T; Huang K; Dinh PU; Wang Z; Vandergriff A; Hensley MT; Cores J; Allen T; Li T; et al. Targeted repair of heart injury by stem cells fused with platelet nanovesicles. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2018, 2, 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wang Y; Lin T; Zhang W; Jiang Y; Jin H; He H; Yang VC; Chen Y; Huang Y A Prodrug-type, MMP-2-targeting Nanoprobe for Tumor Detection and Imaging. Theranostics 2015, 5 (8), 787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kanki S; Jaalouk DE; Lee S; Yu AY; Gannon J; Lee RT Identification of targeting peptides for ischemic myocardium by in vivo phage display. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 2011, 50 (5), 841–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wang X; Chen Y; Zhao Z; Meng Q; Yu Y; Sun J; Yang Z; Chen Y; Li J; Ma T; et al. Engineered Exosomes With Ischemic Myocardium-Targeting Peptide for Targeted Therapy in Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc 2018, 7 (15), No. e008737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Won YW; McGinn AN; Lee M; Bull DA; Kim SW Targeted gene delivery to ischemic myocardium by homing peptide-guided polymeric carrier. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 10 (1), 378–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zhu LP; Tian T; Wang JY; He JN; Chen T; Pan M; Xu L; Zhang HX; Qiu XT; Li CC; et al. Hypoxia-elicited mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes facilitates cardiac repair through miR-125b-mediated prevention of cell death in myocardial infarction. Theranostics 2018, 8 (22), 6163–6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Vandergriff A; Huang K; Shen D; Hu S; Hensley MT; Caranasos TG; Qian L; Cheng K Targeting regenerative exosomes to myocardial infarction using cardiac homing peptide. Theranostics 2018, 8 (7), 1869–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Dang Y; Gao N; Niu H; Guan Y; Fan Z; Guan J Targeted Delivery of a Matrix Metalloproteinases-2 Specific Inhibitor Using Multifunctional Nanogels to Attenuate Ischemic Skeletal Muscle Degeneration and Promote Revascularization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13 (5), 5907–5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hu C-MJ; Fang RH; Wang K-C; Luk BT; Thamphiwatana S; Dehaini D; Nguyen P; Angsantikul P; Wen CH; Kroll AV; et al. Nanoparticle biointerfacing by platelet membrane cloaking. Nature 2015, 526 (7571), 118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Blanco E; Shen H; Ferrari M Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol 2015, 33 (9), 941–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Tatur S; Maccarini M; Barker R; Nelson A; Fragneto G Effect of functionalized gold nanoparticles on floating lipid bilayers. Langmuir 2013, 29 (22), 6606–6614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Duan Y; Nie Y; Gong T; Wang Q; Zhang Z Evaluation of blood compatibility of MeO-PEG-poly (d, l-lactic-co-glycolic acid)-PEG-OMe triblock copolymer. J. Appl. Polym. Sci 2006, 100 (2), 1019–1023. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Nguyen MM; Gianneschi NC; Christman KL Developing injectable nanomaterials to repair the heart. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2015, 34, 225–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Sharma G-D; He J; Bazan HE p38 and ERK1/2 coordinate cellular migration and proliferation in epithelial wound healing evidence of cross-talk activation between map kinase cascades. J. Biol. Chem 2003, 278 (24), 21989–21997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Wu X; Reboll MR; Korf-Klingebiel M; Wollert KC Angiogenesis after acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res 2021, 117 (5), 1257–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Hanna A; Frangogiannis NG The role of the TGF-β superfamily in myocardial infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med 2019, 6, 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Méndez-Barbero N; Gutiérrez-Muñoz C; Blanco-Colio LM Cellular crosstalk between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vascular wall remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2021, 22 (14), 7284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Varesio L; Raggi F; Pelassa S; Pierobon D; Cangelosi D; Giovarelli M; Bosco MC Hypoxia reprograms human macrophages towards a proinflammatory direction. J. Immunol 2016, 196, 201.2. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Goff DC; Sellers DE; McGovern PG; Meischke H; Goldberg RJ; Bittner V; Hedges JR; Allender PS; Nichaman MZ; Group RS Knowledge of heart attack symptoms in a population survey in the United States: the REACT trial. Arch. Int. Med 1998, 158 (21), 2329–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Hoshyar N; Gray S; Han H; Bao G The effect of nanoparticle size on in vivo pharmacokinetics and cellular interaction. Nanomedicine 2016, 11 (6), 673–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Alexis F; Pridgen E; Molnar LK; Farokhzad OC Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2008, 5 (4), 505–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Nguyen MM; Carlini AS; Chien MP; Sonnenberg S; Luo C; Braden RL; Osborn KG; Li Y; Gianneschi NC; Christman KL Enzyme-Responsive Nanoparticles for Targeted Accumulation and Prolonged Retention in Heart Tissue after Myocardial Infarction. Adv. Mater 2015, 27 (37), 5547–5552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Sullivan HL; Gianneschi NC; Christman KL Targeted nanoscale therapeutics for myocardial infarction. Biomater. Sci 2021, 9 (4), 1204–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Kanki S; Jaalouk DE; Lee S; Yu AYC; Gannon J; Lee RT Identification of targeting peptides for ischemic myocardium by in vivo phage display. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 2011, 50 (5), 841–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Wang X; Chen Y; Zhao Z; Meng Q; Yu Y; Sun J; Yang Z; Chen Y; Li J; Ma T; Liu H; Li Z; Yang J; Shen Z Engineered exosomes with ischemic myocardium-targeting peptide for targeted therapy in myocardial infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc 2018, 7 (15), No. e008737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Tang J; Su T; Huang K; Dinh P-U; Wang Z; Vandergriff A; Hensley MT; Cores J; Allen T; Li T; et al. Targeted repair of heart injury by stem cells fused with platelet nanovesicles. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2018, 2 (1), 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Owens EA; Henary M; El Fakhri G; Choi HS Tissue-specific near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Acc. Chem. Res 2016, 49 (9), 1731–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Chin K; Khattak SF; Bhatia SR; Roberts SC Hydrogel-perfluorocarbon composite scaffold promotes oxygen transport to immobilized cells. Biotechnol. Prog 2008, 24 (2), 358–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).White JC; Stoppel WL; Roberts SC; Bhatia SR Addition of perfluorocarbons to alginate hydrogels significantly impacts molecular transport and fracture stress. J. Biomed. Mater. Res, Part A 2013, 101 (2), 438–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Seifu DG; Isimjan TT; Mequanint K Tissue engineering scaffolds containing embedded fluorinated-zeolite oxygen vectors. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7 (10), 3670–3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Ng SM; Choi JY; Han HS; Huh JS; Lim JO Novel microencapsulation of potential drugs with low molecular weight and high hydrophilicity: hydrogen peroxide as a candidate compound. Int. J. Pharm 2010, 384 (1–2), 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Bae SE; Son JS; Park K; Han DK Fabrication of covered porous PLGA microspheres using hydrogen peroxide for controlled drug delivery and regenerative medicine. J. Controlled Release 2009, 133 (l), 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Oh SH; Ward CL; Atala A; Yoo JJ; Harrison BS Oxygen generating scaffolds for enhancing engineered tissue survival. Biomaterials 2009, 30 (5), 757–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Pedraza E; Coronel MM; Fraker CA; Ricordi C; Stabler CL Preventing hypoxia-induced cell death in beta cells and islets via hydrolytically activated, oxygen-generating biomaterials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2012, 109 (ll), 4245–4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Erdem A; Darabi MA; Nasiri R; Sangabathuni S; Ertas YN; Alem H; Hosseini V; Shamloo A; Nasr AS; Ahadian S; Dokmeci MR; Khademhosseini A; Ashammakhi N; et al. 3D Bioprinting of Oxygenated Cell-Laden Gelatin Methacryloyl Constructs. Adv. Healthc. Mater 2020, 9 (15), No. e1901794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Ahmad Shiekh P; Anwar Mohammed S; Gupta S; Das A; Meghwani H; Kumar Maulik S; Kumar Banerjee S; Kumar A Oxygen releasing and antioxidant breathing cardiac patch delivering exosomes promotes heart repair after myocardial infarction. Chem. Eng. J 2022, 428, No. 132490. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Harrison BS; Eberli D; Lee SJ; Atala A; Yoo JJ Oxygen producing biomaterials for tissue regeneration. Biomaterials 2007, 28 (31), 4628–4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Peng Y; Seekell RP; Cole AR; Lamothe JR; Lock AT; van den Bosch S; Tang X; Kheir JN; Polizzotti BD Interfacial Nanoprecipitation toward Stable and Responsive Microbubbles and Their Use as a Resuscitative Fluid. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 2018, 57 (5), 1271–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Kheir JN; Scharp LA; Borden MA; Swanson EJ; Loxley A; Reese JH; Black KJ; Velazquez LA; Thomson LM; Walsh BK; et al. Oxygen gas-filled microparticles provide intravenous oxygen delivery. Sci. Transl. Med 2012, 4 (140), 140ra88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Piacentino V III; Weber CR; Chen X; Weisser-Thomas J; Margulies KB; Bers DM; Houser SR Cellular basis of abnormal calcium transients of failing human ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res 2003, 92 (6), 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Tashiro M; Inoue H; Konishi M Magnesium homeostasis in cardiac myocytes of Mg-deficient rats. PLoS One 2013, 8 (9), No. e73171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Ai X; Curran JW; Shannon TR; Bers DM; Pogwizd SM Ca2+/calmodulin–dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ. Res 2005, 97 (12), 1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Kleiman NS; White HD; Ohman EM; Ross AM; Woodlief LH; Califf RM; Holmes DR Jr; Bates E; Pfisterer M; Vahanian A Mortality within 24 h of thrombolysis for myocardial infarction. The importance of early reperfusion. The GUSTO Investigators, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries. Circulation 1994, 90 (6), 2658–2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Løvlien M; Johansson I; Hole T; Schei B Early warning signs of an acute myocardial infarction and their influence on symptoms during the acute phase, with comparisons by gender. Gend. Med 2009, 6 (3), 444–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Guan Y; Gao N; Niu H; Dang Y; Guan J Oxygen-release microspheres capable of releasing oxygen in response to environmental oxygen level to improve stem cell survival and tissue regeneration in ischemic Hindlimbs. J. Controlled Release 2021, 331, 376–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Guan Y; Niu H; Dang Y; Gao N; Guan J Photoluminescent oxygen-release microspheres to image the oxygen release process in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2020, 115, 333–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Guan Y; Niu H; Liu Z; Dang Y; Shen J; Zayed M; Ma L; Guan J Sustained oxygenation accelerates diabetic wound healing by promoting epithelialization and angiogenesis and decreasing inflammation. Sci. Adv 2021, 7 (35), No. eabj0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]