Abstract

It has been shown that mammalian retinal glial (Müller) cells act as living optical fibers that guide the light through the retinal tissue to the photoreceptor cells (Agte et al., 2011; Franze et al., 2007). However, for nonmammalian species it is unclear whether Müller cells also improve the transretinal light transmission. Furthermore, for nonmammalian species there is a lack of ultrastructural data of the retinal cells, which, in general, delivers fundamental information of the retinal function, i.e. the vision of the species. A detailed study of the cellular ultrastructure provides a basic approach of the research. Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate the retina of the spectacled caimans at electron and light microscopical levels to describe the structural features. For electron microscopy, we used a superfast microwave fixation procedure in order to achieve more precise ultrastructural information than common fixation techniques.

As result, our detailed ultrastructural study of all retinal parts shows structural features which strongly indicate that the caiman retina is adapted to dim light and night vision. Various structural characteristics of Müller cells suppose that the Müller cell may increase the light intensity along the path of light through the neuroretina and, thus, increase the sensitivity of the scotopic vision of spectacled caimans. Müller cells traverse the whole thickness of the neuroretina and thus may guide the light from the inner retinal surface to the photoreceptor cell perikarya and the Müller cell microvilli between the photoreceptor segments. Thick Müller cell trunks/processes traverse the layers which contain light-scattering structures, i.e., nerve fibers and synapses. Large Müller cell somata run through the inner nuclear layer and contain flattened, elongated Müller cell nuclei which are arranged along the light path and, thus, may reduce the loss of the light intensity along the retinal light path. The oblique arrangement of many Müller cell trunks/processes in the inner plexiform layer and the large Müller cell somata in the inner nuclear layer may suggest that light guidance through Müller cells increases the visual sensitivity.

Furthermore, an adaptation of the caiman retina to low light levels is strongly supported by detailed ultrastructural data of other retinal parts, e.g. by (i) the presence of a guanine-based retinal tapetum, (ii) the rod dominance of the retina, (iii) the presence of photoreceptor cell nuclei, which penetrate the outer limiting membrane, (iv) the relatively low densities of photoreceptor and neuronal cells which is compensated by (v) the presence of rods with long and thick outer segments, that may increase the probability of photon absorption. According to a cell number analysis, the central and temporal areas of the dorsal tapetal retina, which supports downward prey detection in darker water, are the sites of the highest diurnal contrast/color vision, i.e. cone vision and of the highest retinal light sensitivity, i.e. rod vision.

Keywords: Caiman, Retina, Tapetum lucidum, Photoreceptor, Müller cell, Glia

1. Introduction

Vertebrate species possess an inverted retina which allows an efficient trophic and structural support of photoreceptors by the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). However, the inversion of the retina has the disadvantage that light traverses the entire neural retina before it arrives at photoreceptors. Cellular structures which have dimensions compatible with the wavelengths of light like cell processes and organelles are phase objects which reflect and scatter light (Zernike, 1955; Land, 1972). The inherent light reflection by the retinal tissue allows the visualization of retinal layers with optical coherence tomography (OCT). In OCT images of human and avian retinas, nerve fiber (NFL) and plexiform layers show the highest reflectivities (Rauscher et al., 2013; Scheibe et al., 2014). This suggests that a considerable proportion of incident light is reflected at neuronal axons and synapses. Further hyperreflective structures are the outer limiting membrane (OLM) and the transition zones between the inner and outer photoreceptor segments which were previously described as “refractive discs” (Detwiler, 1943). Photon scattering reduces the intensity and the signal-to-noise ratio of the light transmitted through the retina (Agte et al., 2011). The resulting decreases in the visual acuity and sensitivity will deteriorate vision particularly under dim light and scotopic conditions under which each absorbed photon is important. It has been shown that, in the mammalian retina, Müller glial cells guide the light with minimal intensity loss through the neuroretina towards the photoreceptor cells; this ensures that the light bypasses the scattering elements of the retina (Franze et al., 2007; Agte et al., 2011; Labin et al., 2014). In the retina of nocturnal mammals, which contains a thick, multilayered outer nuclear layer (ONL), the outer Müller cell processes are very thin. Here, the light is transported by the nuclei of rod photoreceptor cells which are arranged in linear vertical columns (Solovei et al., 2009). These nuclei form a chain of lenses which transmit the light delivered by Müller cells and direct it to the receptor segments (Solovei et al., 2009). However, it is unclear whether Müller cells of nonmammalian species also improve the light transmission through the neuroretina.

Crocodilians are characterized by a semi-aquatic lifestyle. They hunt and feed from the muddy and gloomy bottom of the water, but also make their pickings from the water’s edge with bright ambient light conditions. Although crocodilians are arrhythmic (cathemeral) animals, which are active during both day (bright) and night (dark), their eyes are rather structurally adapted for vision under dim light and scotopic conditions. This adaptation is recognizable, for example, in the presence of tapeta lucida and the rod dominance of the retina (Heinemann, 1877; Chievitz, 1889; Abelsdorff, 1898; Garten, 1907; Laurens and Detwiler, 1921; Detwiler, 1943; Duke-Elder, 1958). Tapeta lucida of crocodilians are formed by light-reflecting guanine crystals in the RPE (Chievitz, 1889; Laurens and Detwiler, 1921; Franz, 1934; Braekevelt, 1977; Dieterich and Dieterich, 1978; Ollivier et al., 2004). Generally, the ocular fundus of crocodilians is separated into two regions: a thick streak in the dorsal fundus has a bright appearance because it contains the tapetum lucidum while the ventral fundus is dark and contains a tapetum nigrum (Chievitz, 1889; Abelsdorff, 1898; Garten, 1907; Laurens and Detwiler, 1921; Dieterich and Dieterich, 1978; Ollivier et al., 2004). The presence of a dorsal lucido-tapetal and a ventral nigro-tapetal retina is suggested to represent an adaptation to the hunting behavior of crocodilians (Duke-Elder, 1958). The higher light sensitivity provided by the tapetum lucidum in the dorsal retina allows the animals to hunt and feed from the dim-lighted bottom of the waters (Abelsdorff, 1898; Dieterich and Dieterich, 1978). To prevent dazzle in bright light, crocodilians reduce the amount of light that reaches the retina by the closure of the slit pupils (Laurens and Detwiler, 1921; Walls, 1942; Banks et al., 2015). The retina of caimans contains rods with large diameter inner and outer segments and three types of cones: long single cones sensitive to red light, short single cones sensitive to blue-violet light, and double cones sensitive to red-green and red-red light, respectively (Govardovskii et al., 1988). The spectral sensitivities of cones suggest that caimans have trichromatic vision (Govardovskii et al., 1988).

The tapetum lucidum and the rod dominance of the retina contribute to the high sensitivity of the crocodilian vision in dim ambient light. However, it is unclear whether there are further structural adaptations of the crocodilian retina which improve the light transmission through the neuroretina and thus the visual sensitivity. For example, it is unclear whether Müller cells have a phenotype which allow them to guide the light through the neuroretina. Therefore, we investigated the ultrastructure of the retina of the brown caiman, Caiman crocodilus fuscus (COPE, 1868) which is one of four recognized subspecies of the spectacled caiman (Velasco and Ayarzagüena, 2010). We describe various ultrastructural specializations of the caiman retina which may improve the visual sensitivity in dim light environments. In addition to the guanine-based tapetum lucidum, these specializations include the peculiar morphology of photoreceptor cells and the spatial arrangements of neuronal perikarya and Müller cell processes in the inner retina.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and anesthesia

Experiments were carried out with IACUC approval and in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the institutional animal care and use guidelines. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. A total of three juvenile brown caimans (length, ~70 cm; age, 5–6 years; both sexes), obtained from a local naturally breeding colony (Laguna Tortuguero, Vega Baja, Puerto Rico), were used. After immobilization on ice, the animals were deeply anesthetized with tiletamine/zolazepam (5 mg/kg; i.p.), and the eyeballs were removed.

2.2. Eye fixation

In order to mark the positions of the different retinal areas, two incisions were placed in the dorsal and nasal sclera of the eyeballs. Two eyes were fixed for electron microscopy using two different methods: (i) one eye was fixed overnight at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde and 5% glutaraldehyde in calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) that consisted of (in mM) 136.9 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 10.1 Na2HPO4, and 1.8 KH2PO4 (pH 7.4 adjusted with Trisbase). Thereafter, the eye was washed with PBS and then stored in PBS with sodium azide (0.01%) at 4 °C until further use. (ii) The anterior part including the lens was cut from the other eye. The remaining eyeball was processed by a fixation procedure modified after Schikorski (2014a,b, 2016) with microwave-assisted aldehyde fixation of oxygenated tissue (Kok and Boon, 1992). The fixation solution was prepared with 1.6% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in low-calcium bicarbonate buffer that consisted of (in mM) 136 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.3 Na2HPO4, 10 NaHCO3, and 2.6 MgCl2. After bubbling of the solution with carbogen (95% O2 and 5% CO2) for 20 min, 0.5 mM CaCl2 was added, and the pH was adjusted to 7.4. The eyeball was transferred into 50 mL of this oxygenated fixative and placed in a microwave for less than 5 s under temperature control, in order to prevent a rise of the tissue temperature above 42 °C. Then, the eye was stored overnight in the oxygenated fixative at room temperature. Thereafter, the eye was stored in PBS with sodium azide (0.01%) at 4 °C until use.

Two further eyes were used for immunohistology. The fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS, pH 7.2 adjusted with Tris-base) was injected through the ora serrata into the vitreous chambers of the eyes. The fixative was injected until the cornea became firm as in eyes in situ. This procedure was carried out immediately and 30 min after enucleation. Thereafter, the eyes were stored for 24 h at 4 °C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, washed with PBS and stored with PBS and sodium azide (0.01%), at 4 °C until use.

2.3. Light and electron microscopy

Tissue pieces (5 × 5 mm) which included the retina, choroid, and sclera were cut from different parts of the eyes. The pieces were rinsed in phosphate buffer (0.1 M; Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) and treated with either one of the two following protocols. (i) The pieces were contrasted with 1% OsO4 for 2 h and subsequently dehydrated using acetone (30, 50, 70, 90, 100%; 15–45 min each). For postcontrasting, the 70% acetone solution contained 1% uranyl acetate (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). (ii) The tissue pieces were contrasted with 1% OsO4 and 1% phosphotungstic acid (Fluka, Munich, Germany) for 60 min and subsequently dehydrated using acetone (50% for 2 × 20 min; 70% for 60 min; 90% for 2 × 20 min; and 100% for 2 × 60 min). Postcontrasting was done as described above. Thereafter, the tissues were gradually embedded in nonhardening epoxide resin (Durcupan ACM Fluka; Sigma)-acetone mixtures (1:3, 1:1, 3:1; 60 min each), incubated overnight in pure Durcupan, and successively replaced by hardening Durcupan. Thereafter, each tissue piece was transferred to a chamber (13 × 6 × 3 mm) filled with hardening Durcupan. After incubation at 80 °C for 3 days (i) or 60 °C for 2 days (ii), semithin (500 nm) and ultrathin (60–65 nm) sections were cut from dried tissue-containing blocks with a microtome employing a diamond knife.

Semithin sections were stained with 0.1% toluidine blue or Richardson solution at 70 °C, and embedded in Canada balsam. The sections were examined with an Axioskop 20 light microscope and a C-Apochromat 40 × /1.2 objective (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Göttingen, Germany), a ColorView II camera (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany), and the Analysis software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solution, Münster, Germany). For electron microscopy, 2–3 ultrathin sections were transferred onto formvar resin-laminated slot grids (diameter, 3.05 mm; slot 2 × 1 mm; Plano, Wetzlar, Germany). The sections were postcontrasted on the grids with 3% uranyl acetate and 3% lead citrate (Serva), and examined with a Sigma-0231 scanning electron microscope (27 kV; Zeiss) employing a STEM detector using the inverted dark field image mode and ATLAS software (Zeiss).

2.4. Immunohistology

In order to prepare vibratome sections, pieces of the neuroretina were embedded in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS containing 3% agarose (w/v), and 50 μm thick sections were cut with a vibratome (HM 650 V; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Erlangen, Germany). Non-specific binding sites were blocked with calcium- and magnesium-free PBS containing 5% normal donkey serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 1% dimethyl sulfoxide for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies (diluted in the blocking solution) overnight at 4 °C. After washing in PBS plus 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% dimethyl sulfoxide, secondary antibodies were applied for 2 h at room temperature. z-Stacks with a depth of 20 μm were recorded with a laser scanning microscope (LSM 510 Meta; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; 1:200; Dako, Hamburg, Germany), mouse anti-myelin oligodendrocyte-specific protein (MOSP; 1:200; Merck Millipore, MA), rabbit anti-oligodendrocyte transcription factor (OLIG2; 1:200; Merck Millipore, MA), Cy2-coupled donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), Cy3-coupled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), and Cy2-coupled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany).

2.5. Data analysis

Histological parameters were obtained in semi- and ultrathin retinal sections. Neuronal, photoreceptor, and Müller cell somata, as well as melanosomes, were counted in sections of various retinal areas within a sectional width of 200 μm; the densities were extrapolated to a retinal width of 1 mm. To obtain the numbers of photoreceptors and neurons, cross-sections through cell nucleus-containing somata were counted. To obtain Müller cell densities, their cell nuclei were counted. (Double) cone cells were discriminated from rod cells on the basis of their tapered outer segments and the difference in the staining level and electron density of photoreceptor cell perikarya; cone cell perikarya are less stained in semithin sections and are less electron dense in ultrathin sections than rod cell perikarya. One double cone was counted as two cones. Data are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical analysis was made with Prism (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA). Significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test and Mann-Whitney U test, respectively, and was accepted at P < 0.05.

3. Results

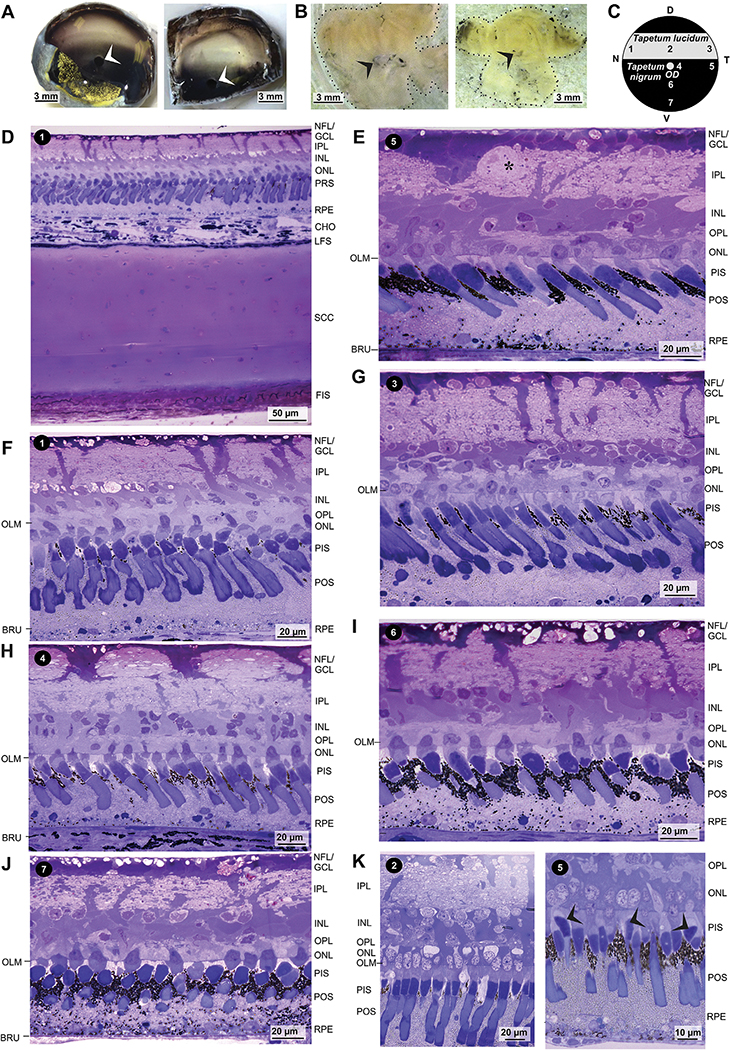

As previously described (Dieterich and Dieterich, 1978), the ocular fundus of caimans is separated into two main areas: a thick streak in the dorsal fundus that has a glistening silvery appearance because it contains the tapetum lucidum, and the ventral fundus and the dorsal periphery of the dorsal fundus which have a dark coloration and contain the tapetum nigrum (Fig. 1A). The ~1 mm horizontal transition zone between the dorsal tapetum lucidum and the ventral tapetum nigrum is located approximately 1.5 mm dorsal to the optic disc (Fig. 1A). The reflectance of the tapetum lucidum is similar across the whole naso-temporal axis of the dorsal fundus. When the neuroretinas were isolated under dim red light conditions after dark adaptation of the animals for 1–2 h, the dorsal tissue had a sulphur-yellow color (Fig. 1B). The color rapidly disappeared in bright light, and the whole isolated neuroretinas became uncolored.

Fig. 1.

Histological structure of the caiman retina in dependence on the retinal topography. A,B Opened eyecups (A) and isolated neuroretinas (B) of two animals. Note the bright lucido-tapetal streak in the dorsal fundus and the dark color of the ventral fundus in the opened eyes. The lower horizontal boundary between both regions is located dorsal to the optic disc (arrowheads). Under dark-adapted conditions, the dorsal neuroretina had a sulphur yellow color while the remaining neuroretina was bright yellow. The contour of the retina is marked with a dashed line (B). C Scheme of the caimain fundus with the retinal areas investigated. 1, nasal lucido-tapetal retina; 2, center of the lucido-tapetal retina; 3, temporal lucido-tapetal retina; 4, dorsal center of the nigro-tapetal retina, near the optic disc (OD); 5, temporal nigro-tapetal retina; 6, mid-periphery of the ventral nigro-tapetal retina; 7, ventral nigro-tapetal retina. D, dorsal; N, nasal; T, temporal; V, ventral. D-K Semithin sections through the posterior pole of the caiman eye (D) and the neuroretina (E-K) of different areas. The sections were stained with toluidine blue (D-J) and Richardson solution (K), respectively. Note the melanosome-containing choroidea (CHO; D). Note also the large, strongly stained Müller cell endfeet in the nerve fiber layer (NFL)/ganglion cell layer (GCL), the thick Müller cell processes that run through the inner plexiform layer (IPL), and the large Müller cell somata in the inner nuclear layer (INL). Some putative displaced amacrine cell somata are present in the GCL (* in E). Note further that many photoreceptor cell nuclei penetrate the outer limiting membrane (OLM). The arrowheads in K indicate ellipsoids of double cone accessory cells that contain spherical ellipsosomes which are stained with higher intensity. BRU, Bruch’s membrane; FIS, fibrous sclera; LFS, lamina fusca sclerae; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; PIS, photoreceptor inner segments; POS, photoreceptor outer segments; PRS, photoreceptor segments; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; SCC, scleral cartilage.

3.1. Ultrastructure of the retinal tapetum and RPE

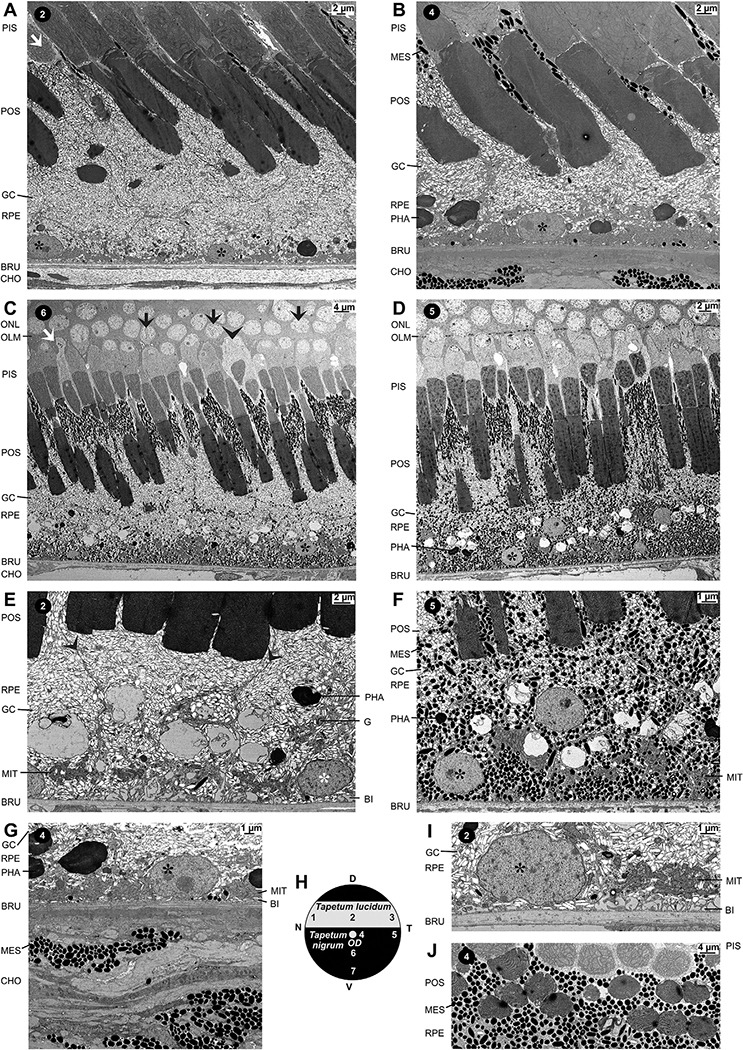

As previously described (Franz, 1934; Braekevelt, 1977; Dieterich and Dieterich, 1978), the retinal tapetum of spectacled caimans is constituted by light-reflecting guanine crystals in RPE cells (Figs. 1E–K and 2A–G,I). The crystals are densely scattered throughout the RPE cells with the exception of the distal tips of the apical (inner) processes which surround the photoreceptor segments and solely contain melanosomes (Figs. 1E–K, 2A–D,I, and 3A–E,G). The density of guanine crystals is decreased in the basal part of the RPE cells (Fig. 2E–G,I). As previously described (Braekevelt, 1977), the elongated guanine crystals are not surrounded by a membrane (Fig. 2I). Most of them are diffusely scattered within the (basal part of the) RPE cell (Fig. 2F,I). Yet, there are also some piles of crystals which are arranged parallel to the surface of the receptor segments (Figs. 2E and 3D).

Fig. 2.

Ultrastructure of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). A-D Electron microscopical images of ultrathin sections through the center of the lucido-tapetal fundus (A), the dorsal center of the nigro-tapetal fundus near the optic disc (B), the ventral mid-peripheral nigro-tapetal fundus (C), and the ventral nigro-tapetal fundus (D). The retina contains predominantly photoreceptors with rod morphology; some putative single cones (white arrows), as well as double cones (black arrowhead), are scattered between the rods. Note that (double) cones have a more electron lucent cytoplasm than rods. In the central lucido-tapetal (A) and nigro-tapetal retinal areas (B), melanosomes (MES) are predominantly located in the distal tips of the apical processes of RPE cells, between the inner (PIS) and the outer photoreceptor segments (POS); some melanosomes are also present in the perikarya of RPE cells near the Bruch’s membrane (BRU) and in the choroidea (CHO). In the mid-peripheral nigro-tapetal retina (C), melanosomes are also arranged along the plasma membranes of RPE cells, while in the peripheral nigro-tapetal retina (D), melanosomes are distributed throughout the RPE cells. Note that small groups of rods are tightly joined together at inner segments and, occasionally, at the outer segments. Note that some photoreceptor cell nuclei possess a large invagination (black arrows). E RPE cells in the central lucido-tapetal retina at higher magnification. The somata of RPE cells contain cell nuclei (*), mitochondria (MIT), Golgi apparatus (G), and phagosomes (PHA). Note that the inner process of one RPE cell surrounds several rod outer segments. Arrowheads, plasma membrane of RPE cells. BI, basal infoldings of RPE cells. F RPE cells in the peripheral nigro-tapetal retina at higher magnification. Note that melanosomes and guanine crystals (GC) are present in the whole RPE cell cytoplasm. G Cross-section through the RPE and choroidea in the central nigro-tapetal retina. Note the presence of melanosomes in cells of the choroidea. H Scheme of the caimain fundus with the retinal areas investigated. I Soma of a RPE cell in the central lucido-tapetal retina. Basal infoldings with thin processes cover the inner surface of the Bruch’s membrane. Mitochondria are predominantly arranged near the RPE nucleus and the Bruch’s membrane. J Horizontal section through the inner (above) and outer segments (below) of rods at the level of the distal tips of RPE cell processes which contain melanosomes, but not guanine crystals, in the nigro-tapetal retina. Note that several inner and outer segments of theses cells are tightly joined together. In this section plane, the ellipsoid-shaped melanosomes have a circular cross section, indicating that they are arranged in parallel to the light path. ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer.

Fig. 3.

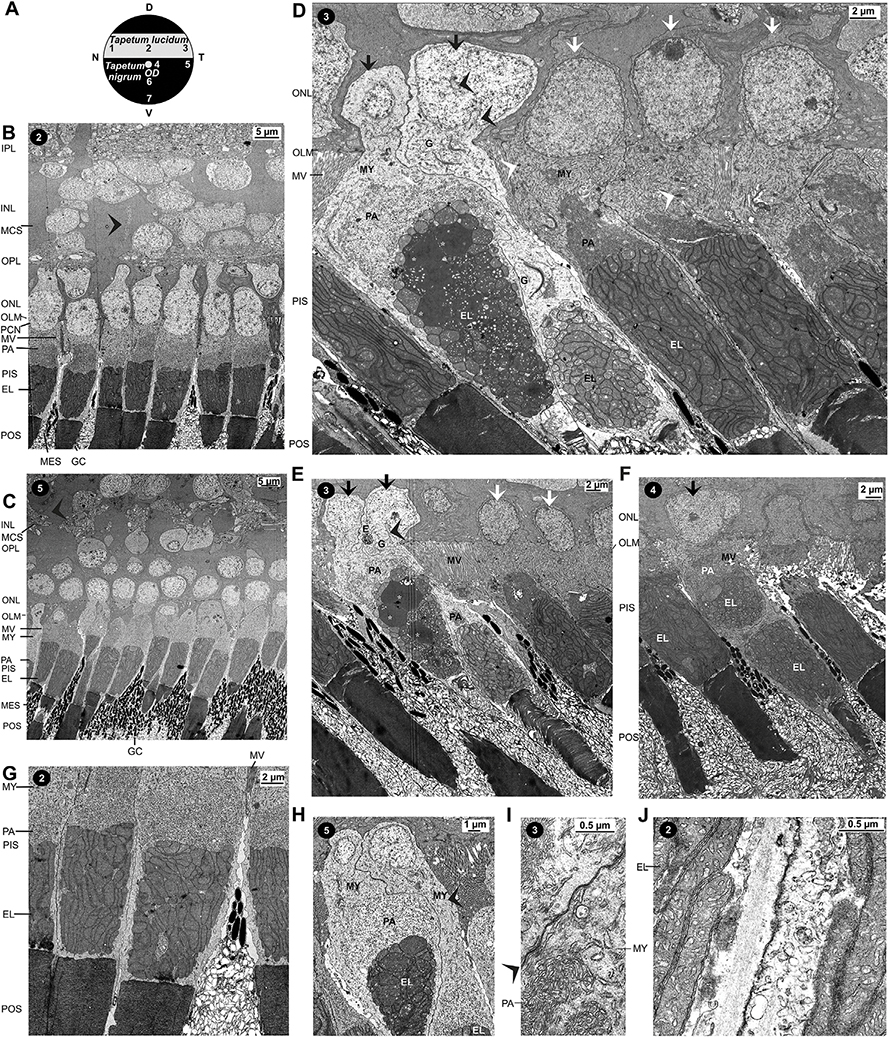

Ultrastructure of photoreceptors. A Scheme of the caimain fundus with the retinal areas investigated. B,C Sections though the central lucido-tapetal retina (B) and the temporal nigro-tapetal retina (C). The retina mainly contains rods. The outer part of many photoreceptor cell nuclei (PCN) penetrates the outer limiting membrane (OLM). Photoreceptor inner segments (PIS) are composed of three parts: myoid (MY), paraboloid (PA), and ellipsoid (EL). Ellipsoids are composed of densely packed mitochondria. Photoreceptor segments are enclosed by processes of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells which contain melanosomes (MES) and guanine crystals (GC). Note the different numbers of melanosomes in the processes of RPE cells in the lucido-tapetal (B) and nigro-tapetal retina (C). Bundles of Müller cell microvilli (MV) extent from the OLM into the subretinal space. The large polygonal cell bodies with electron-dense (dark) cytoplasm in the inner nuclear layer (INL) are cross-sections through Müller cell somata (MCS). Arrowheads indicate flattened, elongated Müller cell nuclei. D,E Cross sections through the outer retina of the temporal lucido-tapetal retina containing double cones (black arrows) and rods (white arrows). The images are derived from consecutive ultrathin sections. Double cones are composed of an accessory cell (left cell) and a principal cell (right cell). The myoids of the double cone inner segments contain smooth and rough endoplasmic reticuli, and Golgi apparatus (G), occasionally endosomes (E). The paraboloids contain only smooth endoplasmic reticuli and very electron-dense (black) glycogen granules and Golgi apparatus. The ellipsoids of accessory (left) cells are composed of mitochondria of different electron-densities, and contain several ellipsosomes (*). The ellipsoids of principal (right) cells are composed of mitochondria of different electron-densities, but do not contain ellipsosomes. The ellipsoidal mitochondria of accessory (left) cells are of the saccular type, while the mitochondria of principal (right) cells are of the intermediate (tubular-saccular) type. Note that in both double cone cells, the electron density of mitochondria which lie near the cell membrane is less than the electron density of mitochondria which are positioned in the core of the ellipsoid. The nuclei of principal (right) cells display a large invagination (black arrowheads) which is not found in the nuclei of accessory cells. Note also that the cyto- and nucleoplasms of double cone cells are less electron-dense than that of the surrounding rods. The myoids of the inner segments from rods contain rough endoplasmic reticuli while the paraboloids of rods is composed of aggregates of smooth endoplasmic reticuli. The paraboloids of rods form cone-shaped caps which cover the entire inner surface of the ellipsoids. Frequently, the myoids and paraboloids of all photoreceptor cell types contain lysosomes (white arrowheads in D). F Section through the accessory cell (upper part) and principal cell (lower part) of a double cone, surrounded by rods, in the dorsal center of the nigro-tapetal retina near the optic disc. The arrow indicates the nucleus of the principal cell. G Rods with glycogen-rich paraboloids in the central lucido-tapetal retina at higher magnification. The inner and outer segments of several cells are tightly joined together. Note that Müller cell microvilli extend up to the paraboloids while the apical processes of pigment epithelial cells extend up to the ellipsoids. The distal tips of the RPE cell processes contain melanosomes, but not guanine crystals. H Paraboloids and ellipsoids of a double cone (arrowhead) at higher magnification. Note that the endoplasmatic reticulum in the paraboloid surround the inner surface of the mitochondria-containing ellipsoid. I Boundary between the myoids and paraboloids of two inner rod segments. While the myoids contain smooth and rough endoplasmic reticuli, the paraboloids contain aggregates of densely packed smooth endoplasmic reticuli. Note the very thin extracellular space between both segments (arrowhead). J Ellipsoids of two rods in the central lucido-tapetal retina. The ellipsoids are composed of densely packed mitochondria of the intermediate (tubular-saccular) type. IPL, inner plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; PHA, Phagosomes; POS, photoreceptor outer segments.

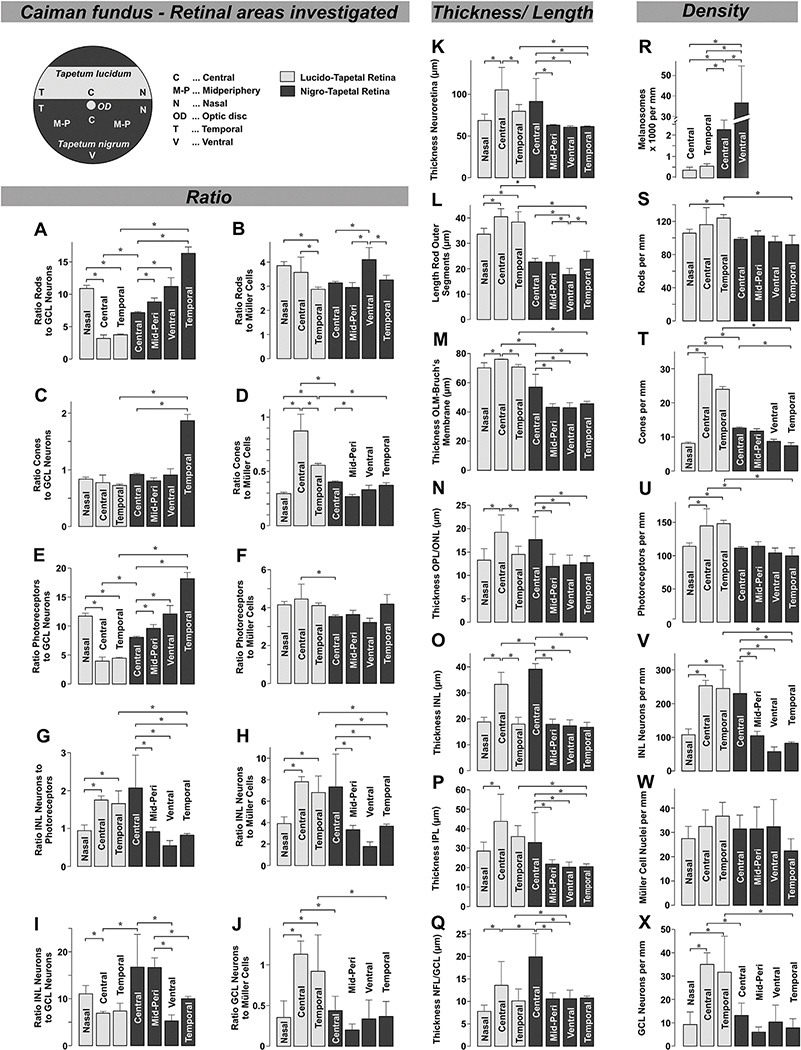

There are differences between RPE cells in the dorsal lucido-tapetal (Fig. 2A,E) and the ventral nigro-tapetal retina (Fig. 2B–D): the thickness of the layer composed of guanine crystal-containing RPE cell processes is significantly (P < 0.05) greater in the lucido-tapeta retina compared to the nigro-tapetal retina (Figs. 2A–D and 4M), and the ratio between the numbers of melanosomes and guanine crystals in RPE cell processes is greater in cells of the nigro-tapetal retina compared to cells of the lucido-tapetal retina. The longer RPE cell processes in the dorsal lucido-tapetal retina (Fig. 4M) enclose longer photoreceptor segments than the shorter RPE cell processes in the ventral nigro-tapetal retina (Fig. 4L).

Fig. 4.

Histometric evaluation of the caiman retina in dependence on the retinal topography. The parameters were obtained in semi- and ultrathin cross sections through the following retinal areas: nasal lucido-tapetal retina, center of the lucido-tapetal retina, temporal lucido-tapetal retina, center of the nigro-tapetal retina near the optic disc, ventral mid-periphery (Mid-Peri) of the nigro-tapetal retina, ventral periphery of the nigro-tapetal retina, and temporal nigro-tapetal retina. The following parameters were evaluated: ratio of rods to GCL neurons (A); ratio of rods to Müller cells (B); ratio of (double) cones to GCL neurons (C); ratio of (double) cones to Müller cells (D); ratio of photoreceptors to GCL neurons (E); ratio of photoreceptors to Müller cells (F); ratio of INL neurons to photoreceptors (G); ratio of INL neurons to Müller cells (H); ratio of INL neurons to GCL neurons (I); and ratio of GCL neurons to Müller cells (J); thickness of the neuroretina, measured between the inner and outer limiting membranes (K); length of rod outer segments (L); thickness between the outer limiting membrane (OLM) and Bruch’s membrane (M); thickness of the outer plexiform (OPL) and outer nuclear layers (ONL) (N); thickness of the inner nuclear layer (INL) (O); thickness of the inner plexiform layer (IPL) (P); thickness of the nerve fiber (NFL) and ganglion cell layers (GCL) (Q); number of melanosomes per mm width of retinal section (R); number of rods per mm width of retinal section (S); number of (double) cones per mm width of retinal section (T); number of photoreceptors per mm width of retinal section (U); number of INL neurons per mm width of retinal section (V); number of Müller cell nuclei per mm width of retinal section (W) and number of GCL neurons per mm width of retinal section (X). Each bar represents mean ± SD obtained in 3–32 measurements. Significant differences: *P < 0.05.

In the lucido-tapetal retina, melanosomes are almost absent from RPE cells. Some melanosomes are present in the distal tips of the apical cell processes located between the inner receptor segments (Fig. 1F,G,K, 2A, and 3B). Few melanosomes are present in the basal part of the cells near the Bruch’s membrane (Fig. 2A,E,I). In the ventral nigro-tapetal retina, melanosomes are present at high numbers in the distal tips of the apical RPE cell processes and at lower numbers in the basal part of RPE cells (Fig. 1I,J, 2B–D,F,G, and 3C,F). In addition, melanosomes are present in cells of the choriocapillaris and, arranged in long horizontal rows, within the lamina fusca sclerae (Fig. 2B,G). There is a significant (P < 0.05) difference in the melanosome content of RPE cells between the dorsal lucido-tapetal and ventral nigro-tapetal retina (Fig. 4R). In the central nigro-tapetal retina, many melanosomes are present in the distal tips of the apical RPE cell processes while the remaining RPE cell is largely devoid of melanosomes (Figs. 1H, 2B and 3F). The melanosome content of RPE cells in the ventral nigro-tapetal retina increases from the central to the peripheral tissue; in the mid-peripheral nigro-tapetal retina, melanosomes are also arranged along the plasma membranes of RPE cells and scattered at low density throughout the RPE cell bodies (Fig. 2C). In the peripheral nigro-tapetal retina, melanosomes are distributed throughout the RPE cells (Fig. 2D,F). In the ventral nigro-tapetal retina, the RPE of the central area (near the optic disc) contains significantly (P < 0.05) less melanosomes (2253 ± 442 per mm width of retinal section) than the RPE of the peripheral area (36,715 ± 18,045 per mm; Fig. 4R). The melanosomes in the distal tips of the apical RPE cell processes are elongated and lie predominantly parallel to the long axis of the photoreceptor segments (Figs. 2A–D and 3B–F). The circular cross-sections of most melanosomes in the middle and basal parts of RPE cells (Fig. 2A–D,F,J) suggest that these organelles are orientated perpendicular to the light path.

3.2. Density of photoreceptors

The retina of caimans contains predominantly rod cells with long and thick cylindrical outer segments (Figs. 1D–K, 2A–D, and 3B–C). In most retinal areas, (double) cones are relatively sparsely scattered between rods (Fig. 2A,C). Double cones are pairs of outer segments attached to a principal and an accessory cell which are closely joined together at the inner segments (Fig. 3D,E). The density of photoreceptors is equal across the whole retina with the exceptions of the center and the temporal periphery of the lucido-tapetal retina which contain higher densities than the remaining tissue (Fig. 4U). These areas also contain significantly (P < 0.05) more (double) cones than the remaining retinal tissue (Fig. 4T). The percentage of (double) cones among all photoreceptors is highest in the central (19.6 ± 2.1%) and temporal areas of the lucido-tapetal retina (16.2 ± 2.3%), falls to 11.4 ± 5.1% in the central nigro-tapetal area, and to 8.5 ± 3.6% in the remaining tissue.

3.3. Ultrastructure of photoreceptor cells

The inner segments of all photoreceptors are divided into three parts: the inner part contains the myoid, the middle part contains the paraboloid, and the outer part contains the ellipsoid (Fig. 3D–G). In rods, the ellipsoids occupy approximately two thirds of the volume of the inner segments. None of the photoreceptor types possess oil droplets in the inner segments. The inner segments of double cones and putative single cones are separated from the surrounding rods by relatively broad groups of Müller cell microvilli and thin RPE cell processes (Figs. 2A and 3D–F).

In rods, the thickness of inner segments is similar to that of the outer segments (Fig. 2B,D and 3E,F). Some inner and, frequently, outer segments of neighboring rods are not separated (Fig. 3B,D,G,I,J); small groups of rod segments are enclosed by the inner processes of one RPE cell (Fig. 2E). The myoids of rod inner segments contain smooth and rough endoplasmic reticuli, and the paraboloids of rods are composed of aggregates of smooth endoplasmic reticuli (Fig. 3I). The large paraboloids of rods cover the entire inner surface of the barrel-shaped ellipsoids (Fig. 3D,G). The ellipsoids of rods are composed of densely packed mitochondria with uniform appearance which are of the intermediate (tubular-saccular) type (Fig. 3D,G).

The outer segments of (double) cones are shorter than the long cylindrical rod outer segments (Fig. 1K right, 2A, and 3E–F). The principal and accessory cells of double cones display various ultrastructural differences. The accessory cell has a thick sclerally tapering inner segment of greater cross-sectional diameter than the outer segment; the paraboloid is localized near the OLM (Fig. 3D). The principal cell has a thinner inner segment which is connected to the soma by a long tubular process which contains the myoid (Fig. 3D). The paraboloids and ellipsoids of principal cells are localized more distant from the OLM than that of accessory cells (Fig. 3D). The nuclei of principal cells display a large invagination which is not observed in the nuclei of accessory cells (Fig. 3D,E). The myoids of double cones may contain large Golgi apparatus and endosomes (Fig. 3D,E). The paraboloids of double cones contain densely packed smooth endoplasmic reticuli and glycogen granules (Fig. 3H). The ellipsoids of accessory cells consist of three different elements which are densely packed: the middle and outer parts are composed of electron-dense mitochondria with numerous bright sacculi, while the inner and lateral margins of the ellipsoids are composed of mitochondria with lower electron density; in addition, the ellipsoids of accessory cells contain several great very electron-dense (dark-grey) ellipsosomes with some electron-lucent (bright) cavities (Fig. 3D; ellipsosomes are marked with *). In semithin sections stained with Richardson solution, the ellipsosomes displayed a higher staining intensity (Fig. 1K right). The ellipsoids of principal cells are composed of relatively electron-lucent mitochondria and (at the inner and lateral margins) very electron-lucent mitochondria (Fig. 3D). The ellipsoidal mitochondria of accessory cells had saccular cavities, and the ellipsoidal mitochondria of the principal cells were of the intermediate (tubular-saccular) type (Fig. 3D).

In the ONL, the perikarya of photoreceptor cells are arranged in one row (Figs. 1E–K and 5A,F). The perikarya contain cell nuclei which are laterally surrounded by thin margins of cytoplasm (Fig. 5A–F). The outer part of the nucleus of many photoreceptor cells penetrates the OLM (Figs. 3B–F and 5A,C). The nucleo- and cytoplasms of cone cells are more electron-lucent than that of rod cells (Figs. 2C, 3D and 5F). Most photoreceptor cells have short and thick axons with large presynaptic terminals. These contain few synaptic ribbons and synaptic densities, and are filled with synaptic vesicles. Cone terminals are polysynaptic whereas rod terminals tend to be oligosynaptic (Fig. 5A,C,F,G). Many photoreceptor cells may lack an axon (Fig. 5F); in these cells, the soma directly passes to the presynaptic terminal, and synaptic vesicles are present in the whole cytoplasm apical to the cell nucleus.

Fig. 5.

Ultrastructure of the outer neuroretina. A Perikarya, short axons, and presynaptic terminals of rods in the outer nuclear (ONL) and outer plexiform layers (OPL) of the central lucido-tapetal retina. The photoreceptor cell nuclei (PCN) penetrate the outer limiting membrane (OLM). The photoreceptor perikarya, axons, and intercellular terminals are enclosed by glial structures which are formed by lamelliform Müller cell processes. The arrow indicates a Müller cell nucleus in the inner nuclear layer (INL). Microvilli (MV) of Müller cells extend from the OLM into the subretinal space. The arrowhead points to a terminal with a synaptic ribbon of a rod. B The section through the temporal lucido-tapetal retina at the level of the OLM shows intercellular junctions between both cells of a double cone (black arrowhead), between a Müller cell and a double cone cell (arrow), between a rod cell and a Müller cell process (white arrow) and between Müller cell processes (white arrowhead). C Relatively small synaptic terminals of rods (arrowheads) surround the broad terminals of cones (black arrows). The photoreceptor cell perikarya are composed of nuclei which are laterally enclosed by thin margins of cytoplasm. The outer parts of the perikarya, which extend into the subretinal space, proceed to the myoids (MY) of the thick inner segments. Thick Müller cell processes draw through the OPL (white arrow). In the ONL, thin lamelliform Müller cell processes sourround the photoreceptor cell perikarya. D Müller cell structures in the ONL and at the OLM. Müller cells form multiple interwoven processes which contain very electron-dense (black) glycogen granules and particulary near the OLM mitochondria (MIT). The Müller cell processes are connected at the OLM and extend microvilli into the subretinal space. E Perikaryon and presynaptic terminal of a cone cell in the ventral nigro-tapetal retina. Note that many thin interwoven Müller cell processes sourround the cone cell perikaryon and terminal. Note also the large invagination in the cone cell nucleus (arrowhead). F Presynaptic terminals of a putative single cone cell (white arrowhead) and a rod cell (black arrowhead). Note the different shapes of the terminals and the different electron-densities of the cytoplasms of both cells. Note also that the Müller cell structures which surround the terminals are composed of many thin interwoven processes. G Presynaptic terminals of rod cells in the OPL. The terminals are filled with synaptic vesicles; dark structures are synaptic densities. Neuronal fibers in the OPL contain neurofilaments (arrow). Note that the presynaptic terminals are partly enclosed by thin Müller cell processes which form multiple laminae (arrowheads).

3.4. Ultrastructure of Müller cells

Müller cells traverse the whole thickness of the neuroretina. At the OLM, Müller cell processes are tightly connected by intercellular junctions which are recognizable at the concentrations of filaments (Fig. 5D). Intercellular junctions are also present between Müller cell processes and photoreceptor cells, and between both cells of double cones (Fig. 5B). Groups of Müller cell microvilli extend from the OLM into the subretinal space up to the level of the paraboloids while the apical processes of RPE cells extend up to the level of the ellipsoids (Fig. 3B–G).

The somata, axons, and presynaptic terminals of photoreceptor cells are surrounded by the outer processes of Müller cells which form multiple interwoven thin lamellae (Figs. 3B–C, 5C,G, and 6F–I). The outer Müller cell processes contain – as the entire Müller cells (with the exception of the microvilli) – filaments and glycogen granules. Mitochondria are mainly localized near the OLM (Fig. 5C–D,G). The OPL is traversed by thick Müller cell processes which proceed into the Müller cell somata in the inner nuclear layer (INL) (Figs. 3B–C, 5C, and 6F–I).

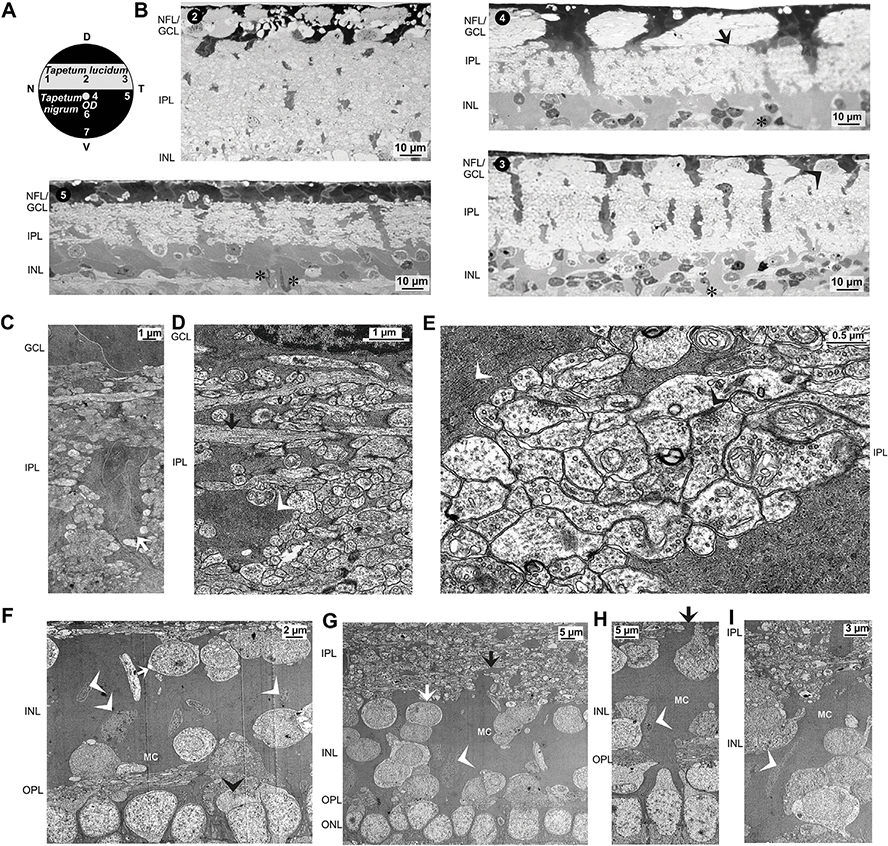

Fig. 6.

(Ultra)structure of the nerve fiber (NFL)/ganglion cell layers (GCL), inner plexiform (IPL), and inner nuclear layers (INL) of the caiman retina. A Scheme of the caimain fundus with the retinal areas investigated. B Toluidine blue-stained semithin sections of various retinal areas. In the central (2) and temporal lucido-tapetal retina (3), the NFL/GCL contains numerous nerve fiber bundles with medium thickness. Note the large somata of ganglion cells in the GCL (black arrowhead). In the central nigro-tapetal retina (4), the NFL/GCL contains very thick nerve fiber bundles while the NFL/GCL of the temporal nigro-tapetal retina (5) contains only few thin nerve fiber bundles. The thickness of the IPL decreases from central to peripheral areas, and the IPL in the lucido-tapetal retina is thicker than that in the nigro-tapetal retina. Usually, thick Müller cell trunks run radially or obliquely through the IPL, but there are also smaller Müller cell side processes (arrow) which are arranged perpendicularly or obliquely to the main processes. Asterisks mark Müller cell nuclei. C Section through the peripheral nigro-tapetal retina. Note that the thick Müller cell trunk which traverses the IPL is composed of several processes (white arrow). D,E IPL of the ventral temporal nigro-tapetal retina. Thick Müller cell processes (white arrowheads) traverses the IPL. Most axons are non-myelinated and not separated by glial processes. Note that the axons contain neurotubuli (arrow in D) and that Müller cells contain very electron-dense (dark grey) filaments (white arrowhead in E) and glycogen granules (black); the filaments follow the geometry of the trunks. Note also that perisynaptic Müller cell processes are located close to the synaptic active zones (black arrowhead in E). F-G Sections through the INL and outer neuroretina of the central nigro-tapetal retina. In the central retina, which contains more neurons than the peripheral retina, the perikarya of second-order neurons are located at the inner and outer margins of the INL. The perikarya are often stacked into columns which traverse the whole thickness of the INL (white arrows). These columns are surrounded by the cytoplasm of large Müller cell somata which fill the majority of the volume of the INL. The nuclei of Müller cells (arrowheads) have a similar electron density as the cytoplasm of Müller cell somata. They appear flattened and elongated; sometimes, the nuclei of the Müller cells are notched. Frequently, the flattened, elongated Müller cell nuclei run in parallel to the columns of the neuronal perikarya. The Müller cell nuclei are mainly located in the mid and outer part of the INL, between the perikarya of horizontal and bipolar cells. Note the presynaptic terminals of a double cone in the OPL (black arrowhead in F) beneath the horizontal cell in the INL. H-I Sections through the INL of the central lucido-tapetal retina. Thick Müller cell trunks in the IPL (arrow) proceed into the large Müller cell somata. The Müller cell somata traverse the whole thickness of the INL and proceed into the outer Müller cell processes. The outer processes traverse the OPL, surround the photoreceptor cell somata in the outer nuclear layer (ONL), and proceed into the Müller cell microvilli (MV). Elongated Müller cell nuclei (arrowheads) are often arranged along the lateral margin of the Müller cell somata.

The major part of INL volumes consist of the cytoplasm of large Müller cell somata interpersed by relatively few somata of interneurons (Fig. 1E,G,J). As indicated by the different intensities of toluidine blue staining of semithin sections, Müller cell somata are very large and nonregularly formed (Fig. 1E–I). The large Müller cell somata form multiple lobular processes which are interwoven (Fig. 6B). The nuclei of Müller cells have a similar electron density as the cytoplasm of the Müller cell somata (Fig. 3B). Most Müller cell nuclei are flat and elongated or sickle-shaped while neighboured neuronal cell nuclei have a more or less round shape (Figs. 3B, 5A, and 6F–I). Müller cell nuclei are located in the mid of the INL or between the perikarya of horizontal and bipolar cells in the outer part of the INL (Figs. 5B and 6B,F–I). In the central retina, many Müller cell nuclei are located close to the columnar rows of superimposed neuronal perikarya which run through the INL (Figs. 3B and 6G). The flattened, elongated Müller cell nuclei are often arranged along the suspected light path (Figs. 3B and 6G–I).

The inner plexiform layer (IPL) is traversed by thick Müller cell trunks and thinner Müller cell processes (Figs. 1D–K and 6B–E). The Müller cell trunks are arranged perpendicular or obliquely to the retinal surface; some Müller cell trunks may split into different processes and may cross the IPL with different directions (Figs. 1D–K and 6B). Thin side processes, which run more or less horizontally through the IPL, originate from the Müller cell trunks and may enclose synapses and axons (Fig. 6E). However, most axon terminals in the IPL are not separated by glial processes (Fig. 6E).

The inner surface of the Müller cell endfeet contact the basal lamina of the inner limiting membrane which lies between the cortex of the vitreous body and the neuroretina (Fig. 7A–C). The endfeet are composed of densely packed lobular processes. These processes are tightly joined together and may display different electron densities (Fig. 7C). In toluidine blue-stained semithin sections, the margins of these lobular processes are recognizable as bright lines (Fig. 1E).

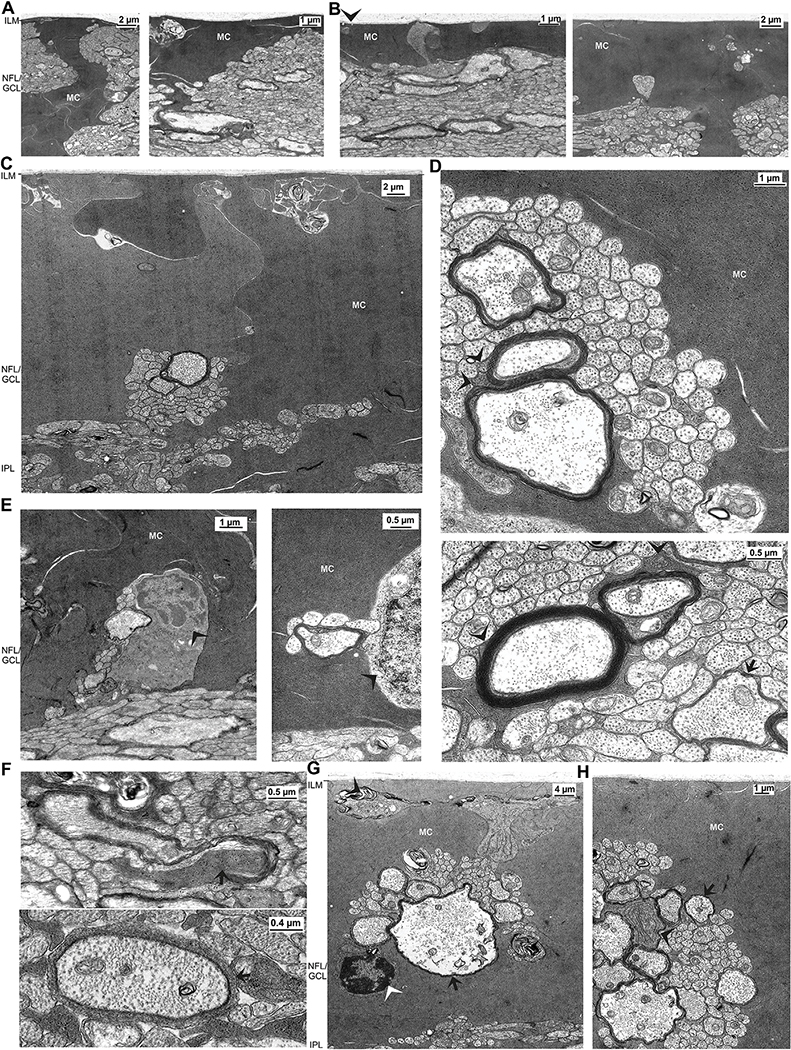

Fig. 7.

Ultrastructure of the nerve fiber (NFL) and ganglion cell layers (GCL). A-C Sections through the NFL/GCL of the central (A) and mid-peripheral retina (B,C). The vitreal cavity contains remnants of vitreous collagen fibers adhered to the basal lamina of the inner limiting membrane (ILM). The inner (vitreal) surface of Müller cell endfeet is smooth, with the exception of rare small membrane infoldings (arrowhead). The NFL/GCL of the central and mid-peripheral retina retina contains bundles of nerve fibers which are separated by thick electron-dense Müller cell trunks which ends up in the Müller cell endfeet (C). The NFL/GCL of the more peripheral nigro-tapetal retina is largely filled by densely packed lobes formed by Müller cell endfeet. Note the different electron densities of these lobes. The Müller glia encloses thin unmyelinated nerve fiber bundles and thicker myelinated nerve fiber bundles which are located at the outer margin of the GCL, near the inner plexiform layer (IPL). D Nerve fiber bundles of the mid-peripheral nigro-tapetal retina. Some thicker myelinated axons are in contact with the electron-dense Müller cell processes (arrowhead) while many thin unmyelinated axons are not separated by Müller cell processes. Nerve fibers contain neurotubuli and mitochondria. The arrow in the bottom image points to a thicker axon which is surrounded by one myelin sheet. The Müller cell cytoplasm contains filaments, which are arranged nearly parallel, and very electron-dense glycogen granules. E Neuronal and oligodendrocytic perikarya in the NFL/GCL of the central lucido-tapetal and temporal nigro-tapetal retina, respectively. Left: the arrowhead points to the electrondense cytoplasm of the oligodendrocytic soma. Right: the arrowhead points to the thin cytoplasmic margin around the neuronal cell nucleus. Thin unmyelinated axons and one thicker myelinated axon are in close contact to the perikarya. F The multilamellar “myelin” sheaths around thick axons may originate from Müller cell processes (arrows), as indicated by the glycogen granula and the electron-dense cytoplasm which are characteristics of Müller cells. G Sections through the NFL/GCL of the ventral temporal nigro-tapetal retina. The nerve fiber bundles contain single giant myelinated axons (arrows), several thick myelinated axons, and numerous thin unmyelinated axons. The soma of the oligodendrocyte (white arrowhead) consists of a nucleus with a thick margin of heterochromatin, surrounded by a thin cytoplasmic margin. There are disordered membranous structures (putative lamellar bodies) sourrounded by Müller cells (black arrowheads). H Multilamellar myelin sheaths in the NFL/GCL are in close contact to Müller cell processes (arrow). Myeliniation may partly also originate from putative oligodenrocytes with slightly electron brigther cytoplasm than that of Müller cells (arrowhead).

3.5. Myelinization of nerve fibers

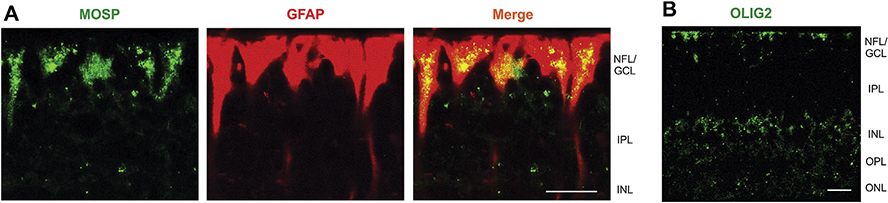

Müller cells may contribute to the myelinization of nerve fibers in the caiman retina. This is indicated by the transition of electron-dense and glycogen granules-containing Müller cell processes originating near the Müller cell endfeet and continuing to axon-surrounding myelin sheets (Fig. 7D,H). In order to support the assumption that Müller cells contribute to the myelinization of ganglion cell axons, we immunostained retinal sections with antibodies against markers of oligodendrocytes. As shown in Fig. 8A, especially the endfeet of Müller cells in the nerve fiber and ganglion cell layers were labeled with an antibody against MOSP, a membrane protein selectively expressed in myelin and oligodendrocytes (Dyer et al., 1991). Müller cells were also labeled with an antibody against OLIG2 (Fig. 8B), a transcription factor which is implicated in the regulation of motor neuron and oligodendrocyte differentiation in the brain and spinal cord (Wegner, 2001). OLIG2 immunoreactivity was predominantly localized to the somata in the INL and the endfeet of Müller cells in the NFL/GCL (Fig. 8B). There were also disordered membranous structures in the NFL (Fig. 7G) which may represent misfolded myelin-like sheets or lamellar bodies.

Fig. 8.

Müller cell expression of oligodendrocyte proteins in the caiman retina. A Double labeling of a section of the central retina with antibodies against the oligodendrocyte marker MOSP (green) and the Müller cell marker GFAP (red). Colabeling yielded a yellow-orange merge signal. B Immunolocalization of OLIG2 in a section of the peripheral retina. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; NFL, nerve fiber layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer. Bars, 20 μm.

3.6. Ultrastructure of the inner retina

The neuroretina of caimans is poorly cellular. The NFL/GCL contain neuronal and oligodendrocytic somata which are scattered between nerve fiber bundles and the electron-dense Müller cell endfeet (Fig. 1E,G, 6B, and 7A–C,E). The neuronal and oligodendrocytic somata consist of a nucleus surrounded by a thin cytoplasmic margin (Fig. 7E). Usually, oligodendrocytic somata display an electron-dense cytoplasm with irregular cell borders and a nucleus with a thick irregular ring of heterochromatin beneath the nuclear membrane. Ganglion cells have more round perikarya and their cytoplasm appear more electron-lucent than that of oligodendrocytes (Fig. 1E,G and 7E).

The thickness of the nerve fiber bundles in the NFL/GCL differs in dependence on the retinal topography. The NFL/GCL of the central and temporal lucido-tapetal retina contain numerous nerve fiber bundles with medium thickness (Fig. 6B). The nerve fiber bundles in the central nigro-tapetal retina are very thick while the NFL/GCL of the temporal nigro-tapetal retina contain few thin nerve fiber bundles (Figs. 6B and 7A). The central nigro-tapetal area has the thickest nerve fiber bundles (Fig. 1H) and the thickest NFL/GCL (Fig. 4Q). The nerve fiber bundles of the central retina fill nearly the whole thickness of the NFL/GCL; the bundles are separated by thick electron-dense Müller cell endfeet (Figs. 6B, 7A and 9). In the peripheral retina, nearly the whole volume of the NFL/GCL is uniformly filled by the cytoplasm of Müller cell endfeet in which thin nerve fiber bundles are integrated (Fig. 1F,G, 6B, and 7C,G).

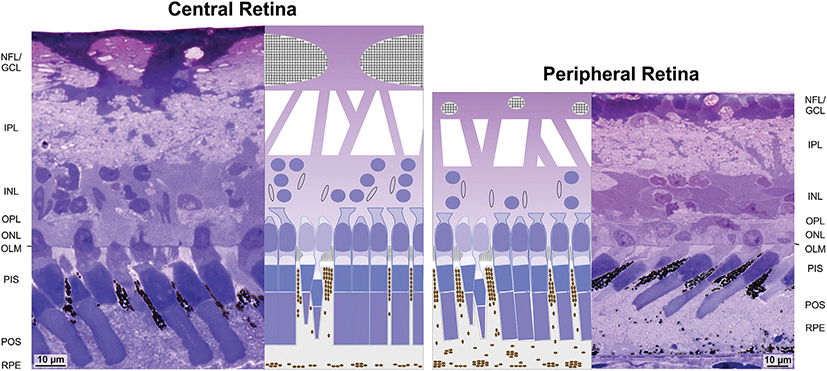

Fig. 9.

The morphology of Müller cells suggests that they contribute to the high sensitivity of caiman’s dim light vision by improving light transmission through the neuroretina. The ultrastructure of Müller cells is similar throughout the caiman retina; differences in the morphology between Müller cell structures of the central (left) and peripheral retina (right) are mainly adaptations to the different density of neuronal cells in the inner nuclear layer (INL) and the different thickness and abundance of nerve fiber bundles in the nerve fiber (NFL) and ganglion cell layers (GCL). Müller cells traverse the whole thickness of the neuroretina and thus may guide the light nearly directly to photoreceptors, i.e., to the photoreceptor cell perikarya in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and the Müller cell microvilli in the subretinal space. Thick Müller cell endfeet in the NFL/GCL, and Müller cell trunks and processes, respectively, which traverse the inner (IPL) and outer plexiform layers (OPL), may direct the light through the layers which contain numerous light-scattering structures, i.e., nerve fibers and synapses. The whole thickness of the INL is traversed by large Müller cell somata. The INL of the central retina, which contains more neurons than the peripheral retina, possesses columns of stacked neuronal perikarya which run through the whole thickness of the layer; between these columns, there are relatively broad regions free of neuronal structures which are filled by Müller cell somata. In the NFL/GCL and INL of the peripheral retina, Müller cell endfeet and somata uniformly fill these layers; in the INL, neuronal perikarya are located at the inner and outer margins of the layer. Light reflection at the outer limiting membrane (OLM) may be reduced by the penetration of photoreceptor cell nuclei and Müller cell microvilli through the OLM. Flattened, elongated Müller cell nuclei in the INL are often arranged along the light path. The oblique arrangement of many Müller cell trunks in the IPL and of the columns of stacked neuronal perikarya in the INL suggests that light guidance through Müller cells may increase visual sensitivity. PIS, photoreceptor inner segments; POS, photoreceptor outer segments; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

The nerve fiber bundles are composed of many thin unmyelinated axons and few thick myelinated axons (Fig. 7B,D,G,H). In addition, some nerve fiber bundles contain single giant myelinated axons (Fig. 7G). The axons comprise neurofilaments and mitochondria (Fig. 7D,F). The myelin sheaths of some thicker axons may be formed by Müller cell processes. Thin unmyelinated axons are not separated by Müller cell processes (Fig. 7D).

In the central retina, neuronal perikarya in the INL are located at the inner and outer margins of the layer, and frequently stacked into columns which are vertically or obliquely arranged (Figs. 1H, 3B and 6G). The columns traverse the whole thickness of the INL and are surrounded by relatively broad regions in which the cytoplasm of large Müller cell somata fills the whole thickness of the INL (Figs. 1H, 3B, and 6F–I). In the INL of the peripheral retina, which contains fewer neuronal perikarya than the central retina (Fig. 4V), neuronal perikarya are located at the inner and outer margins of the layer.

3.7. Quantitative parameters of the neuroretina

We measured the retinal thickness and cell numbers in semi- and ultrathin sections of various retinal areas. The neuroretina of juvenile caimans is thin (Fig. 4K), likely because it is poorly cellular. The neuroretina of the central areas of the dorsal lucido-tapetal and ventral nigro-tapetal retina is significantly (P < 0.05) thicker than the neuroretina in the more peripheral tissue (Fig. 4K). The overall retinal thickness is greater in central than in peripheral areas (Fig. 4N–Q). The temporal area of the lucido-tapetal retina has similar densities of photoreceptors and neurons in the INL and GCL as the central area of the lucido-tapetal retina (Fig. 4S–V,X). The densities of photoreceptors and GCL neurons are highest in the central and temporal areas of the lucido-tapetal retina (Fig. 4U,X). The densities of INL neurons are similar in the central and temporal areas of the dorsal lucido-tapetal retina and the central area of the ventral nigro-tapetal retina (Fig. 4V). The ratio between the numbers of photoreceptors and INL neurons is approximately 1:2 in the central areas of the lucido-tapetal and nigro-tapetal retina, and in the temporal lucido-tapetal area, and approximately 1:1 in the remaining tissue (Fig. 4G). The convergence ratio between INL and GCL neurons is lower (7:1) in the central and temporal lucido-tapetal retina, and higher (17:1) in the central nigro-tapetal retina (Fig. 4I). The ratio between the numbers of photoreceptors and GCL neurons is lowest (4:1) in the central and temporal lucido-tapetal retina (Fig. 4E). This ratio mainly reflects the ratio between the numbers of rods and GCL neurons (Fig. 4A). The ratio of (double) cones to GCL neurons is similar (~0.8:1) across the whole retina with the exception of the temporal nigro-tapetal area (Fig. 4C). The density of Müller cells is similar across the whole retina (Fig. 4W). The ratio of photoreceptors to Müller cells is slightly greater in the dorsal lucido-tapetal than in the ventral nigro-tapetal central retina (Fig. 4F). While the ratio of rods to Müller cells displays only slight variations across the different areas of the retina (Fig. 4B), the ratio of (double) cones to Müller cells is greatest (0.85:1) in the central lucido-tapetal retina. It decreases to 0.55:1 in the temporal lucido-tapetal retina, and is similarly low (0.3–0.4:1) in the remaining tissue (Fig. 4D). The ratio of INL neurons to Müller cells is highest in the central areas and the temporal lucido-tapetal area (Fig. 4H), while the ratio of GCL neurons to Müller cells is highest in the central and temporal areas of the lucido-tapetal retina (Fig. 4J).

4. Discussion

4.1. Retinal tapetum

As suggested by the presence and spatial arrangement of the tapetum lucidum, the retina of spectacled caimans is structurally adapted to vision under dim light and scotopic conditions as well as to the semi-aquatic lifestyle and the ambush hunting behavior of the animals (Detwiler, 1943; Duke-Elder, 1958). The tapetum lucidum is formed by light-reflecting guanine crystals in the apical RPE processes which enclose the photoreceptors (Figs. 1K and 2A). As previously described (Dieterich and Dieterich, 1978), the dorsal retina of caimans contains the tapetum lucidum (Fig. 2A) which extends as a broad streak across the whole naso-temporal axis (Fig. 1A,C). The thickness of the guanine crystal-containing RPE cell processes is greatest in the central dorsal retina and decreases slightly in the nasal and temporal areas of the dorsal retina (Fig. 4M). However, as previously described (Franz, 1934; Dieterich and Dieterich, 1978), the RPE of the whole retina of caimans contains guanine crystals (Figs. 1E–K and 2A–F); therefore, the silvery appearance in the dorsal ocular fundus (Fig. 1A) results from the low density of melanosomes in the distal tips of the apical RPE cell processes (Figs. 1E–K, 2A, and 4R). The low density of melanosomes in the lucido-tapetal retina suggests that the dorsal retina has a nonocclusible tapetum, i.e., the RPE cells do not contain a sufficient number of melanosomes in their processes to occlude the mirror effect of guanine crystals (Kopsch, 1892; Laurens and Detwiler, 1921; Braekevelt, 1977). The dark coloration of the ventral fundus (Fig. 1A) is caused by the densely packed melanosomes which are present at high numbers in the distal tips of the RPE cell processes; here, melanosomes obscure the reflecting guanine crystals (Figs. 1E–K and 2B–D). Dieterich and Dieterich (1978) suggested that Caiman crocodilus has an occlusible tapetum. A slight melanosome migration in RPE cells, characteristic of an occlusible retinal tapetum, was demonstrated in the retina of American alligators (Laurens and Detwiler, 1921). However, Abelsdorff (1898) and Garten (1907) did not find light-dependent changes in the position of melanosomes in the RPE of crocodilians. In addition to the regulation of the retinal sensitivity, occlusible tapeta may control the intensity of eyeshine (Ollivier et al., 2004).

The light-reflecting guanine crystals in RPE cell processes behind and between the receptor outer segments increase the light available to the receptors. Various structural features of the retina, e.g., the thickness of the guanine crystal-containing RPE cell processes (Fig. 4M), the distribution of melanosomes in RPE cells (Fig. 4R), and the length of rod outer segments (Fig. 4L), suggest that the dorsal lucido-tapetal retina (in particular, the central and temporal areas) provides the highest visual sensitivity in caimans. The hunting behavior of crocodilians involves waiting for the right time to ambush a prey in a posture with only the eyes and nostrils protruding above the water’s surface. The presence of the tapetum lucidum in the dorsal retina and the absence of a tapetum lucidum in the ventral retina may compensate the difference in the light intensity between the muddy and gloomy water and the sky, and thus may adjust the amounts of light reaching the photoreceptors in the dorsal and ventral retina. Crocodilians are unable to focus underwater (Beer, 1898; Fleishman et al., 1988); the highly sensitive, downwardly directed lucido-tapetal vision may improve the tracking of underwater prey items with eyes above the water.

As previously described (Braekevelt, 1977), most guanine crystals are of nonuniform size and are arranged without any orientation in the basal part of RPE cells (Figs. 2F and 3G). This suggests that the tapetum lucidum of caimans provides mainly a diffuse backscattering of light onto photoreceptors which increases the retinal sensitivity but lowers the acuity. A low spatial resolution of rod vision is also suggested by the relatively high convergence ratio between rods and GCL neurons (Fig. 4A) and the fact that small groups of tightly joined rod outer segments (Fig. 3B,G) are enclosed by the apical processes of one RPE cell (Fig. 2E). Each group of joined rods may function as a macroreceptor. While RPE cell processes in the peripheral nigro-tapetal retina contain guanine crystals which are rather irregulary arranged (Fig. 2F), RPE cell processes in the central lucido-tapetal retina contain guanine crystals which are organized more regularly and which surround the photoreceptor outer segment membranes in a quite parallel fashion (Fig. 2A,E). A more regular arrangement of guanine crystals in RPE cells may provide direct reflection of light onto photoreceptors, as described for some teleostean fishes (Francke et al., 2014). Cones are present at a lower density than rods (Fig. 4T,S), and cone outer segments are optically isolated by the melanosome- and crystal-containing RPE cell processes (Figs. 1K right, 2A, and 3E,F). The optical isolation of cones increases the sensitivity of color vision without a loss of acuity and prevents a blurring of the image resulting from the interference of the reflected light, a common disadvantage of choroidal tapeta (Ollivier et al., 2004).

Under dark-adapted conditions, the dorsal, but not the ventral, neuroretina had a sulphur-yellow color (Fig. 1B) (Dieterich and Dieterich, 1978). The color of the dorsal neuroretina rapidly disappeared on exposure to light because of rhodopsin bleaching (Abelsdorff, 1898; Walls, 1932). A similar phenomenon was reported in the rod-dominated retina of American alligators (Tafani, 1883). The different colors of the dorsal and ventral neuroretina under dark-adapted conditions may suggest a difference in the rate of regeneration of 11-cis retinal between the dorsal lucido-tapetal and ventral nigro-tapetal retina. Because in higher vertebrates, the sensitivity of cones recovers faster than in rods, the different colors of the dorsal and ventral neuroretina may in part reflect the different incidence of cones and rods in both regions (Fig. 4T,S). However, it has been shown that rhodopsin of alligators is much more rapidly synthesized in solution than mammalian and bird rhodopsins, at rates similar to cone pigments of higher vertebrates (Wald et al., 1957). It is also possible that the high amount of melanosomes in RPE cells (Fig. 4R) and the smaller thickness of RPE cell processes (Fig. 4M) are associated with a lower abundance of 11-cis retinal-regenerating enzymes in the ventral nigro-tapetal retina.

4.2. Photoreceptor cells

The retina of crocodilians contains rods, single cones, and double cones (Heinemann, 1877; Krause, 1893; Laurens and Detwiler, 1921; Rochon-Duvigneaud, 1943; Govardovskii et al., 1988; Sillman et al., 1991). Similar to the retinas of other nocturnal reptiles, the majority of photoreceptors in the caiman retina are rods (Fig. 4T,S). Rod cells have a more electron-dense cytoplasm than (double) cone cells. The rod-to-cone ratio in the peripheral retina of American alligators is 10–12:1 (Verrier, 1933; Kalberer and Pedler, 1963; Laurens and Detwiler, 1921). These values are very similar to those found in the peripheral caiman retina. Nocturnal species that depend on vision for foraging increase light absorption by having long and thick cylindrical rod-shaped photoreceptor outer segments (Figs. 1E–K and 2A–D). Rod cells in the dorsal lucido-tapetal caiman retina have longer outer segments than rod cells in the ventral nigro-tapetal retina (Fig. 4L).

The inner cone segments of many reptiles, birds, and nonplacental mammals contain an oil droplet (Franz, 1913; Rodieck, 1973). As previously described (Govardovskii et al., 1988), none of the photoreceptor types of the caiman retina possesses oil droplets (Figs. 2A–D and 3C). An absence of oil droplets was also described in other crocodilians like Australian and Mexican crocodiles, and American alligators (Heinemann, 1877; Laurens and Detwiler, 1921; Walls, 1942; Rochon-Duvigneaud, 1943; Kalberer and Pedler, 1963; Nagloo et al., 2016).

We found various ultrastructural differences between the principal and accessory cells of double cones and putative single cones, respectively. Among others, the ellipsoids of double cone accessory cells, but not the ellipsoids of double cone principal cells, single cones, and rods, contain ellipsosomes (Fig. 1K right and 3D). To the best of our knowledge, the presence of ellipsosomes was described, hitherto, only for cone ellipsoids of certain teleosts (MacNichol et al., 1978; Nag and Bhattacharjee, 1995) and for some photoreceptors of lampreys (Collin and Pottert, 2000). Ellipsosomes are thought to determine the spectral sensitivity of photoreceptors (Collin et al., 2009). They are ultrastructurally similar to oil droplets. Ontogenetically, ellipsosomes develop from ellipsoidal mitochondria (Berger, 1966; Anctil and Ali, 1976; MacNichol et al., 1978). The electron-lucent cavities, which are found at low quantities in ellipsosomes (Fig. 3D) and which represent remnants of mitochondrial sacculi (MacNichol et al., 1978; Nag and Bhattacharjee, 1995), reflect the mitochondrial origin of these spherical bodies. Ellipsosomes of teleosts contain a heme pigment that is suggested to serve as a filter for blue and ultraviolet light (MacNichol et al., 1978). It has been proposed that ellipsosomes in green and red cones of teleosts increase the contrast in the blue-violet region of the spectrum (MacNichol et al., 1978; Nag and Bhattacharjee, 1995). A similar functional role of ellipsosomes in caimans will improve the visual resolution in watery habitats and under twilight conditions. As the diameter of the inner segments of accessory double cone cells is considerably larger than the small tapered outer segments, these organelles may contribute to focusing the light onto the outer segments, a function which is comparable to the focusing action of oil droplets (Young and Martin, 1984). Further beneficial effects of ellipsosomes may include the protection of accessory cell outer segments (which are located near the OLM) from the damaging effects of ultraviolet light and the reduction of chromatic aberration (Walls and Judd, 1933). In birds and turtles, double cones are thought to be used for achromatic vision (Richter and Simon, 1974; Vorobyev et al., 1998). Double cones of caimans are sensitive to red-green and red-red light (Govardovskii et al., 1988). The presence of ellipsosomes likely alters the spectral sensitivity of accessory cells; therefore, spectacled caimans may have (at least) tetrachromatic instead of trichromatic vision.

Photoreceptor segments are light-guiding structures (Enoch and Tobey, 1981, and references therein). In double cones, the ellipsoids contain mitochondria with different electron densities; mitochondria with the highest density are located in the center of the ellipsoids. This composition of ellipsoids may support the function of these organelles, i.e., to be collecting lenses that focus the light onto the outer photoreceptor segments. In the retina of nocturnal mammals, a similar lens function has been proposed for the rod nuclei which contain heterochromatin in their center (Solovei et al., 2009). Arey (1928) suggested that the paraboloids and ellipsoids of rod inner segments serve to concentrate the light upon the outer segments because they have geometrical forms like those of component lenses in achromatic objectives, and because both are more refractive than the surrounding medium. Virchow termed paraboloids “inner lenses” and ellipsoids “outer lenses” (Franz, 1913).

In the caiman retina, the outer part of the nuclei of many rod and cone cells penetrates the OLM (Fig. 1K right, 2C,D, 3B,D, and 5A–C,E). OLM-penetrating photoreceptor cell nuclei were described in many lower vertebrates like fishes, frogs, and lizards (Arey, 1916; Walls, 1942). In the retina of American alligators, rods, but not cones, have nuclei which penetrate the OLM (Walls, 1942; Kalberer and Pedler, 1963). In the retina of many teleosts, cone, but not rod, nuclei penetrate the OLM (Franz, 1913). OLM-penetrating cell nuclei may improve the light transmission through this membrane. In OCT images of human and avian retinas, the OLM represents a hyperreflective layer (Rauscher et al., 2013; Scheibe et al., 2014). Light reflection at the OLM will reduce the visual sensitivity which is particularly important under dim light and scotopic conditions. It has been suggested that in the peripheral mammalian retina, which is specialized to scotopic vision, columns of photoreceptor cell nuclei provide a chain of lenses that direct the light to the photoreceptor segments (Solovei et al., 2009). A dioptric role of photoreceptor cell nuclei in reptiles and birds may be suggested by the findings that cone nuclei in the lizard retina become longer and narrower in light (Chiarini, 1906) and that light induces alterations in the volume and position of cone nuclei in the pigeon retina (Birch-Hirschfeld, 1906). OLM-penetrating cell nuclei may create low-reflective light pathways through this membrane (Fig. 1K right) and thus may increase the amount of photons which reach the receptor segments. However, whether the nuclei of photoreceptor cells reduce the light reflection at the OLM remains to be determined with OCT imaging. In addition to the nuclei and the thick receptor segments, further structural features of photoreceptor cells may improve the light transmission to the receptor segments and thus the retinal light sensitivity. Photoreceptor cells of the caiman retina have large presynaptic terminals and short and thick axons (Fig. 5A,C,E,F); many cells have no axon. Photoreceptor cells without an axon were also described for the retina of American alligators (Kalberer and Pedler, 1963). The absence of an axon could be explained with the thickness of the receptor segments and photoreceptor cell somata which lie in one row in the OPL (Figs. 1E–K and 5A,F); this cytoarchitecture merely requires short or no axons. The large presynaptic terminals and the short and thick axons of photoreceptor cells may serve for photon capture and guidance through the ONL, and thus may increase visual sensitivity.

4.3. Cellular composition of the caiman retina

The retinas of Australian crocodiles and American alligators possess a horizontal streak throughout the dorsal retina which contains the tapetum lucidum and the highest density of ganglion cells (Chievitz, 1891; Nagloo et al., 2016). The elongated shape of the horizontal streak, which spans the naso-temporal axis of the dorsal retina, may allow tracking of prey items over an extended area of the visual field without the requirement of head movements (Nagloo et al., 2016). We found that the retina of juvenile spectacled caimans has the highest density of GCL neurons in the central and temporal areas of the lucido-tapetal retina (Fig. 4X). The distribution of the GCL neuron density coincides with the distribution of (double) cone density (Fig. 4T), suggesting that the central and temporal areas of the lucido-tapetal retina provide the highest acuity of color vision in caimans. The low convergence ratio between rods and GCL neurons (Fig. 4A) suggests that these areas also provide the highest acuity of rod vision. The high acuity supplied by the temporal lucido-tapetal retina may support binocular vision towards the ventral visual field and thus may improve movement sensitivity and prey detection in muddy and gloomy waters.

Visual acuity mainly depends on the eye size and the density of retinal ganglion cells (Peichl et al., 2005). It is possible to obtain a crude estimate of the spatial resolving power of the central and temporal areas of the lucido-tapetal retina of spectacled caimans. By using the method of Pettigrew et al. (1988), and assuming a peak density of ganglion cells of 1100 per mm2 (Fig. 4X) and an axial length of the eye ball of 17 mm (Fig. 1A), the peak spatial resolving power of the juvenile spectacled caimans used in the present study is approximately 5.3 cycles/degree. This value is slightly lower than that described for juvenile Australian crocodiles (~8 cycles/degree; Nagloo et al., 2016), lower than that of diurnal geckos and the Carolina anole (13.2 and 16.9 cycles/degree, respectively), but similar to that described for nocturnal geckos (3.2 cycles/degree) (Makaretz and Levine, 1980; Röll, 2001; Hall, 2008). However, as the eyes of crocodilians growth throughout life (Ngwenya et al., 2013), the visual acuity of caimans will increase with growing eyes.

Caimans are arrhythmic animals. In comparison to mammalian species, the number of rods per Müller cell in the caiman retina (3–4:1; Fig. 4B) is higher than in the retinas of photopic species (~0.1:1), but lower than in the retinas of mesopic (~10:1) and scotopic species (~25:1) (Reichenbach and Bringmann, 2010). The peak number of cones per Müller cell in the caiman retina (~0.8:1; Fig. 4D) is similar to that of scotopic mammalian species (~0.8:1) (Reichenbach and Bringmann, 2010). (However, the density of Müller cells in the mammalian retina changes with the retinal location, with high density in the central retina and low density in the peripheral retina [Reichenbach and Bringmann, 2010]. The density of Müller cells in the caiman retina is similar in the various retinal areas (Fig. 4W)). Other retinal characteristics, e.g., the presence of a tapetum, may suggest that caimans possess a retina similar to other crepuscular and nocturnal vertebrate species. The morphology of photoreceptors and the cellular composition of the caiman retina are similar to that of nocturnal geckos. Like caimans, nocturnal geckos have rod-dominated retinas (but lack guanine-based tapeta), relatively few photoreceptors, and rods with long and thick outer segments; and the ONL of the gecko retina contains a single row of thick photoreceptor cell perikarya (Abelsdorff, 1898; Detwiler, 1943; Röll, 2001). It has been described that there is little convergence in the gecko retina; the ratio between photoreceptor and ganglion cells is approximately unity (Duke-Elder, 1958). In the juvenile caiman retina, the ratio between photoreceptors and GCL neurons is approximately 4:1 in the central and temporal lucido-tapetal retina, and increases in the nigro-tapetal and peripheral retina (Fig. 4E). A convergence ratio between photoreceptors and ganglion cells of approximately 4:1 (ranging between 2:1 and 7:1 in the central and peripheral retina, respectively) has been reported for the retina of juvenile American alligators (Rochon-Duvigneaud, 1943; Kalberer and Pedler, 1963). We found that the ratio between the numbers of cones and GCL neurons is approximately 1:1 in nearly all retinal areas (Fig. 4C) while the rod-to-GCL neuron ratio differs largely in dependence on the retinal topography (Fig. 4A).

Abelsdorff (1898) stated that crocodiles are not only capable of seeing in very weak light, but can also find their way in pitch darkness. It has been shown that nocturnal geckos have a very high sensitivity of color vision which is 350 times higher than that of humans; geckos discriminate colors in dim moonlight when humans are color blind (Roth and Kelber, 2004). It is possible, but remains to be proven, that the cones in the retina of caimans also serve color vision under dim light and nocturnal conditions. Light reflection at the guanine crystals in the RPE cell processes which surround the (double) cone segments (Fig. 1K right, 2A, and 3E,F) increases the sensitivity of color vision under dim light conditions.

4.4. Müller cells may contribute to light transmission through the neuroretina