Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Selection bias is a well-known concern in research on older adults. We discuss two common forms of selection bias in aging research: (1) survivor bias and (2) bias due to loss to follow-up. Our objective was to review these two forms of selection bias in geriatrics research. In clinical aging research, selection bias is a particular concern because all participants must have survived to old age, and be healthy enough, to take part in a research study in geriatrics.

DESIGN:

We demonstrate the key issues related to selection bias using three case studies focused on obesity, a common clinical risk factor in older adults. We also created a Selection Bias Toolkit that includes strategies to prevent selection bias when designing a research study in older adults and analytic techniques that can be used to examine, and correct for, the influence of selection bias in geriatrics research.

RESULTS:

Survivor bias and bias due to loss to follow-up can distort study results in geriatric populations. Key steps to avoid selection bias at the study design stage include creating causal diagrams, minimizing barriers to participation, and measuring variables that predict loss to follow-up. The Selection Bias Toolkit details several analytic strategies available to geriatrics researchers to examine and correct for selection bias (eg, regression modeling and sensitivity analysis).

CONCLUSION:

The toolkit is designed to provide a broad overview of methods available to examine and correct for selection bias. It is specifically intended for use in the context of aging research.

Keywords: selection bias, loss to follow-up, survivor bias, obesity

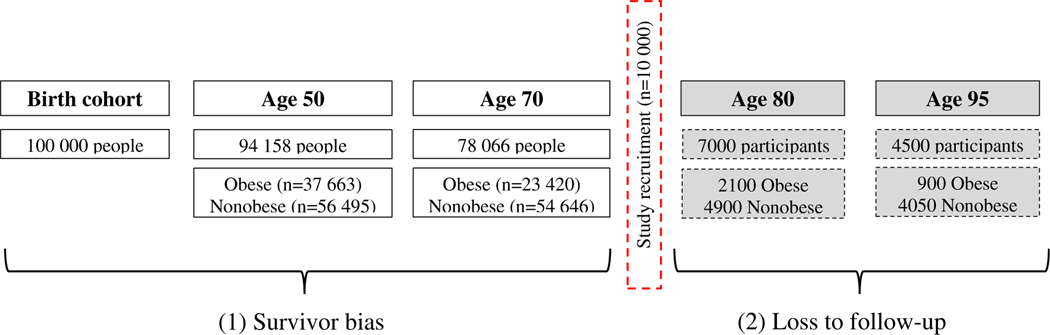

Selection bias is a well-known problem in research on older adults.1–3 In clinical aging research, selection bias is a particular challenge because all participants must have survived to old age to be part of a research study in geriatrics, and, owing to the significant increase in morbidity and mortality that occur with aging, it is highly likely that older individuals will drop out of a study for health-related reasons. Two types of selection bias are depicted in Figure 1: survivor bias and bias due to loss to follow-up.

Figure 1.

Two types of selection bias in in aging research, due to (1) survivor bias and (2) loss to follow-up. Of 100 000 people in a US birth cohort, 94 158 individuals survive to age 50. At age 50, 40% (n = 37 663) are obese; 60% are not obese (n = 56 495). By age 70, only 78 066 individuals are alive, of whom 30% (n = 23 420) are obese and 70% are nonobese (n = 54 646). Between the ages of 50 and 70, 16 092 people died, and a greater proportion of those who died were obese (89%; n = 14 243) compared with nonobese (11%; n = 1849). This represents selective survival because those who are obese in middle age are less likely to survive to old age. Of those who are alive at age 70, 10 000 are recruited by a team of geriatrics researchers interested in establishing a prospective cohort to study the relationship between obesity and clinical outcomes in older adults. By age 80, 7000 participants were still actively involved in the study, 30% of whom are obese (n = 2100). By age 95, 4500 participants were still part of the study, 20% of whom are obese (n = 900). Over the course of study follow-up, obese participants were more likely to drop out, either because they chose not to continue with the study or died. Of those who dropped out between age 80 and 95, 48% were obese and 34% were nonobese. Note: Birth cohort statistics adapted from the 2015 US National Vital Statistics Report (www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr67/nvsr67_07-508.pdf).

Selection bias occurs when the measure of effect (eg, odds ratio, risk ratio [RR]) calculated in the study sample does not accurately represent the true causal relationship between exposure and outcome in the general population.4–6 It can produce a bias toward the null (masking a true association), away from the null (exaggerating a true association), or even reverse the expected direction of an effect, making a harmful exposure appear protective or a protective exposure appear harmful.1,6,7 The term “exposure” is used here to refer to the independent, or explanatory, variable of interest. For instance, in a randomized controlled trial of a new weight loss medication, the drug treatment is referred to as the exposure; in a case-control study of the relationship between obesity and myocardial infarction, obesity is the exposure. Appendix S1 lists a glossary of key terms used throughout this article.

The primary goal of this article is to describe selection bias in the context of aging research. Selection bias is an important issue to consider in any research study in geriatrics, regardless of study design. We additionally aim to focus on the methods that can be used to identify and correct for selection bias using examples that are relevant for a clinical geriatrics researcher. We created a Selection Bias Toolkit for researchers to use when designing a research study in geriatrics or when analyzing data from a clinical sample of older adults. Throughout this article, we demonstrate concepts related to selection bias using applied case studies with obesity as the exposure variable, given the clinical relevance of obesity in geriatric settings.

SURVIVOR BIAS

Survivor bias, also commonly called selection bias due to differential survival or left truncation, refers to the concept that only certain individuals survive to reach old age.8 In studies of older adults, this kind of selection bias may arise when survival up to cohort entry (the beginning of study follow-up) is influenced by the exposure of interest or variables closely related to the exposure of interest. For instance, obesity is known to lead to premature mortality.9 Researchers must consider this fact when studying the impact of obesity in older adults because those who survived to old age may represent the healthiest group of obese individuals (ie, those who are obese without hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, or a high amount of visceral fat). Those who are obese but died at younger ages are, in effect, missing from clinical studies on older adults.10

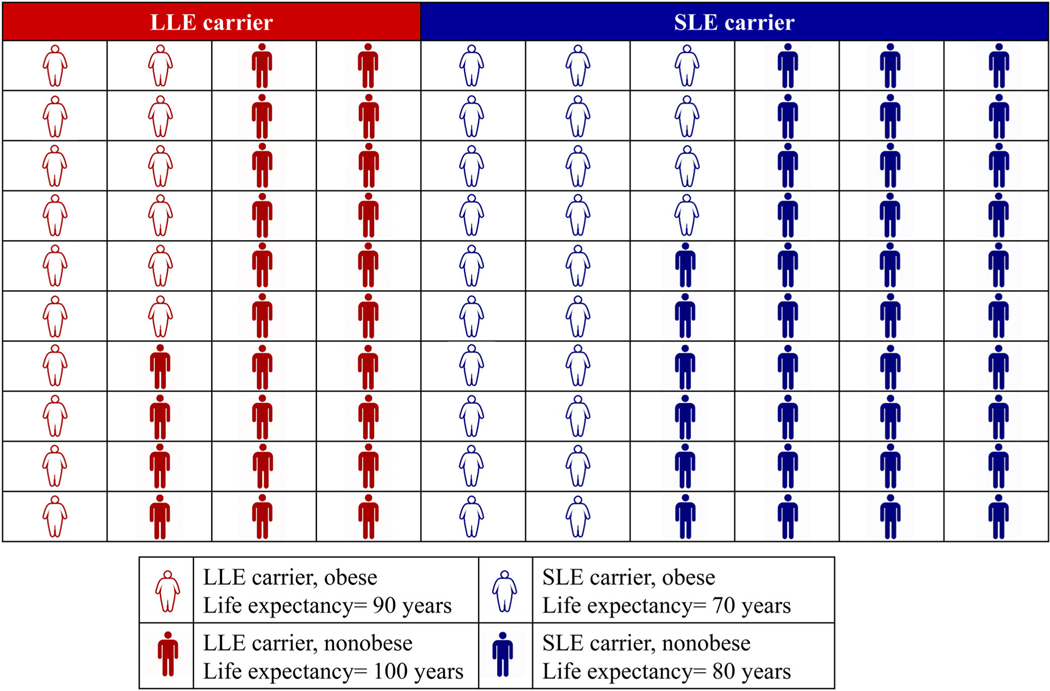

Case study 1: A physician specializing in the care of older adults decides to study the relationship between obesity and mortality in 100 patients from a large tertiary care center. Unbeknownst to the physician, her patients older than 65 years are composed of individuals with genetic variation, such that 40% of her patients have an allele called LLE, or long life expectancy, and 60% have an allele called SLE, or short life expectancy (Figure 2). In this tertiary care center, 40% of patients are obese. Obesity is independent of the longevity alleles in the population: 40% of those with LLE allele are obese, and 40% of those with SLE allele are obese. For simplicity, consider adult obesity status a fixed characteristic (ie, it does not change over time). Consistent with our understanding of the effect of obesity on life expectancy, the life expectancy of obese individuals is 10 years less than nonobese individuals.11

As shown in Figure 2, in a sample of 100 individuals from this clinical population, there are 16 individuals [= (100 × .4) × .4)] with the LLE allele who are obese, and they have a life expectancy of 90 years. There are 24 individuals [= (100 × .4) × .6)] with the LLE allele who are not obese; they have a life expectancy of 100 years. Among those with the SLE allele, 24 individuals are obese [= (100 × .6) × .4)] and have a life expectancy of 70 years; 36 individuals are not obese [= (100 × .6) × .6)] and have a life expectancy of 80 years. If we were to conduct a prospective study of the patients in the tertiary care center and recruit 100 participants at age 65, a simple calculation of the relationship between obesity and mortality would demonstrate that, as expected, obesity appears harmful: the mean life span with obesity would equal 78 years [= ((24 × 70) + (16 × 90))/40], whereas the mean life span without obesity would equal 88 years [= ((36 × 80) + (24 × 100))/60]. This demonstrates that, on average, people who are nonobese live longer than those who are obese.

However, if we were to study the effect of obesity only among patients who survived past 75 years, the mean life span among those who are obese is 90 years [= (16 × 90)/16]; the mean life span among those who are not obese is 88 years [= ((36 × 80) + (24 × 100))/60]. Those who have the SLE allele and are obese (n = 24) are not accounted for in this analysis because they died before age 75. In an analysis that only considers participants who lived past 75 years, those who are obese appear to live longer than those who are nonobese, which is the opposite of the effect seen when studying the entire population of the tertiary care center.

Figure 2.

Schematic of a cohort (n = 100) consisting of individuals who are obese and nonobese with the long life expectancy (LLE) and short life expectancy (SLE) genes. LLE carriers who are obese (n = 16) have a life expectancy of 90 years, LLE carriers who are not obese (n = 24) have a life expectancy of 100 years, SLE carriers who are obese (n = 24) have a life expectancy of 70 years, and SLE carriers who are nonobese (n = 36) have a life expectancy of 80 years. If you were to study the entire cohort, the average life expectancy in obese individuals [(16 people × 90 y LE) + (24 people × 70 years LE)]/40 = 78 y] is lower than in nonobese individuals [(24 people × 100 y LE) + (36 people × 80 y LE)]/60 = 88 y]. However, if you study only those who survive past age 75, the average life expectancy in obese individuals is higher [(16 people × 90 y LE)]/16 = 90 y] than in nonobese individuals [(24 people × 100 y LE) + (36 people × 80 y LE)]/60 = 88 y].

This hypothetical case study demonstrates how selection bias can distort the relationship between exposure and outcome. In our simplified example, the only two causes of dying young are obesity and the SLE allele. Although unrealistic in this sense, and also in the magnitude of the single allele effects, the example was designed to highlight the challenge of studying older adults in clinical settings. Age 75 was chosen as a cut point in this analysis to demonstrate how selection bias operates, not to indicate that all research studies of individuals older than 75 years are biased. Any sample selected from a geriatric medicine clinic has the potential to be affected by selection bias. Geriatrics researchers must ask themselves this key question: “Did the exposure I am interested in studying influence the likelihood of surviving to old age and being included in the study sample?”

In clinical research, selection bias is particularly challenging because it is a physician’s job to treat patients who show up for clinic visits, and, by extension, ask questions and study the effect of exposures or interventions among these individuals. It is a common misconception that a study conducted in a selected group of participants is valid if the study results are only going to be generalized to individuals within that group. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. The effect estimate (eg, risk ratio) calculated in a highly selected group of survivors may not be a valid estimate of the effect even within that group because of selection bias.

Consider this empirical example that uses data from the 1999 to 2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES):

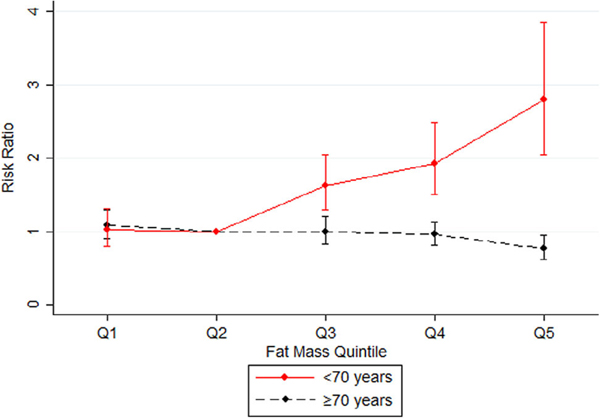

Case Study 2: A team of researchers is interested in examining whether the body fat and mortality relationship differs between individuals younger than 70 years and those older than 70 years. Body fat was measured from a whole-body dual energy x-ray absorptiometry scan. The team estimated the RR of mortality comparing individuals in quintiles 1, 3, 4, and 5 of body fat with individuals in quintile 2, the reference group. Appendix S2 provides additional details about the methods for this analysis (see Tables S1 and S2)

In participants younger than 70 years, as expected, higher body fat percentage was associated with increased mortality risk (Figure 3). Compared with individuals in quintile 2, there was a monotonic increase in mortality risk for individuals in quintile 3 (RR = 1.63; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.29–2.05), quintile 4 (RR = 1.93; 95% CI = 1.50–2.48), and quintile 5 (RR = 2.81; 95% CI = 2.04–3.85) of body fat. However, in participants above age 70, having high body fat was associated with a lower mortality risk. In older adults, as body fat increased, the mortality RR decreased: compared with individuals in quintile 2, the RRs were 1.00 (95% CI = .83–1.20) for quintile 3, .96 (95% CI = .82–1.14) for quintile 4, and .76 (95% CI = .62-.94) for quintile 5. Individuals over age 70 in the highest body fat quintile had a 24% lower mortality risk than the reference group.

Figure 3.

Graphic comparison of the mortality risk ratios for quintiles (Qs) of body fat among individuals younger than 70 years of age and 70 years of age or older.

In this case study using real-world data from NHANES, we demonstrate that high body fat, a harmful exposure that decreases the chance of surviving to old age, may appear protective when studying only old-age survivors. It is important to note that although selection bias is one possible explanation for the unexpected relationship between body fat and mortality in older adults, it does not preclude alternative explanations.12

SELECTION BIAS DUE TO LOSS TO FOLLOW-UP

In longitudinal studies of older adults, losses to follow-up are inevitable.2,13 Loss to follow-up occurs when participants drop out of a study. There are several common reasons for participants to be deemed lost to follow-up, such as those who choose not to take part in additional study visits, those who stop responding to study questionnaires, or individuals who are unwell and no longer able to participate. Losses to follow-up can produce selection bias. The numerous terms for this concept include “selection bias due to differential attrition,” “selective attrition,” “informative censoring,” or “right censoring.”10,13–15 The following case study describes an example in which obesity is associated with dropout, and dropping out is also associated with the outcome, recurrent myocardial infarction, producing selection bias:

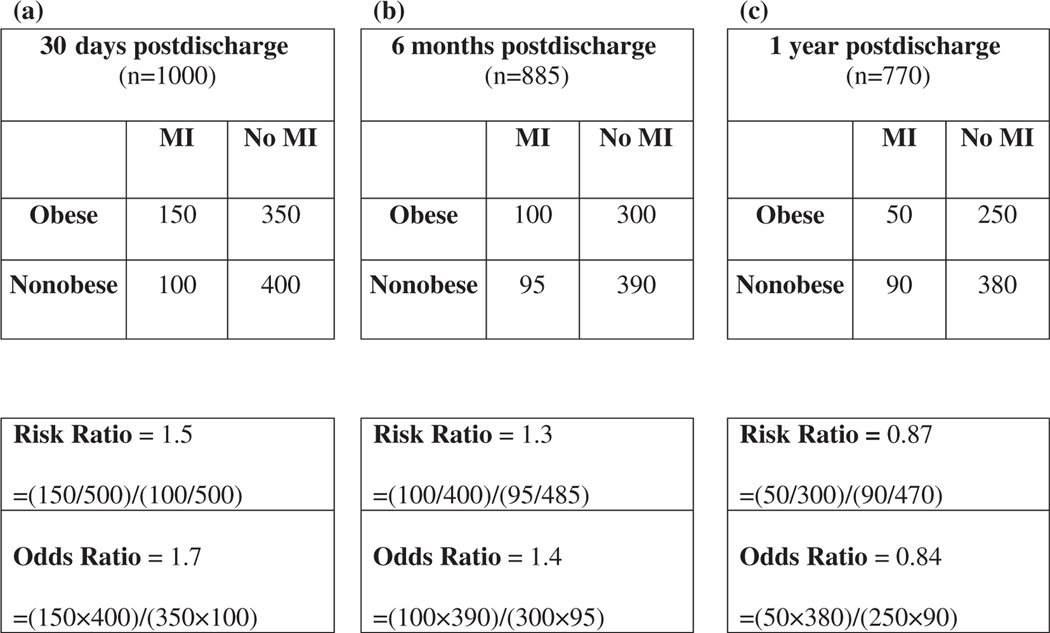

Case study 3: A team of researchers is interested in following a cohort of older adults discharged from the hospital following an acute cardiac event. Their aim is to investigate whether patients who have a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m2 at the time of discharge are at a higher risk of having a second acute cardiac event in the first year following their discharge compared with nonobese patients (BMI <30 kg/m2).They recruited 1000 patients, 500 obese patients and 500 nonobese patients. At 30 days postdischarge (Figure 4A), all 1000 participants remained in the study cohort, 150 of the obese patients had been readmitted to the hospital for a second acute cardiac event, and 100 nonobese patients had been readmitted. The RR of a recurrent event is (150/500)/(100/500) = 1.5, meaning obese individuals are 50% more likely to have had a recurrent event in the first 30 days than nonobese individuals. By 6 months (Figure 4B), 885 individuals remained in the study cohort; 115 had been lost to follow-up. The RR of a recurrent event was (100/400)/ (95/485) = 1.3; obese individuals were 30% more likely to have a recurrent event than nonobese individuals by 6 months. At 1 year, only 770 individuals remained in the cohort; 230 individuals had been lost to follow-up (Figure 4C). The RR for a recurrent event at 1 year was (50/300)/(90/470) = .87, meaning obese individuals were 13% less likely to have a recurrent event than nonobese individuals by 1 year.

Figure 4.

The 2 × 2 tables from a fictitious cohort study of the relationship between obesity and recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) in older adults at 30 days, 6 months, and 1 year following discharge for an acute cardiac event.

After seeing these results, one possible conclusion is that obesity protects against recurrent cardiac events in the first year following discharge. However, before reaching that conclusion, it is important to consider the reasons why patients dropped out of the study. Note that over the course of the 1-year follow-up, 200 patients who were obese dropped out of the study while only 30 patients who were nonobese dropped out. In other words, loss to follow-up was differential by obesity status. This produces selection bias because it is likely that the reasons why an individual dropped out of the study are associated with having a recurrent event. For instance, those who had a more severe initial event might be more likely to drop out and also more likely to have a recurrent event, and those with uncontrolled cardiovascular risk factors also might be more likely to drop out and have a recurrent event.6,16–18 In this fictitious example, it is clear that loss to follow-up is producing a form of selection bias that must be remedied before examining estimates of the relationship between obesity and recurrent cardiac events in the first year postdischarge.

SELECTION BIAS TOOLKIT

Having reviewed selection bias and why it is an important concern in the context of aging research, the remainder of this article focuses on practical strategies for investigating and remediating selection bias. We created a Selection Bias Toolkit (Table 1) for clinical investigators to use when designing a research study and/or analyzing study data. This toolkit is intended to provide an overview of the methods available to geriatrics researchers, but not every method will be applicable for every researcher or situation. It is also important to take note that although some geriatrics researchers may not be familiar with the technical details or statistical assumptions of each of these methods, it may still be helpful to know the tools that are available for discussion with a collaborating epidemiologist or biostatistician.

Table 1.

Selection Bias Toolkit

| Study stage | Method | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Design | Causal diagrams | Graphic representation of causal effects between variables. Useful for identifying sources of selection bias and describing assumptions about relationships between variables of interest. |

| Data collection | Minimizing barriers to completing data collection in geriatric setting. Collecting as much information as possible on potential predictors of censoring. | |

| Analysis | Descriptive statistics | Examine distribution of important variables among individuals who remained in the study compared with those who were lost to follow-up or died during the follow-up period. |

| Model determinants of selection | Use a regression model (ie, logistic regression) to determine which variables are predictors of censoring. In certain situations it is possible to include predictors of censoring in the main analytic models. | |

| Sensitivity analysis | Supplementary analyses that involve hypothesizing about a range of different selection mechanisms and estimating the effect of specific selection scenarios on study results. | |

| Bias analysis | Similar to sensitivity analyses, bias analysis includes hypothesizing about the magnitude of specific selection mechanisms (sampling fractions) and adjusting effect estimates by dividing the biased effect estimate by the selection bias factor. | |

| Inverse probability weighting | Used to correct for selection bias by up-weighting individuals who remain in the study cohort to account for themselves as well as those with similar characteristics who have been lost to follow-up. | |

| Principal stratification | The effect of exposure on outcome in the subset of individuals who would have survived to old age, regardless of exposure status. | |

| Multiple imputation | Replacing missing values (for individuals lost to follow-up) with a set of plausible variables to create a complete simulated data set. | |

| Instrumental variables | Method to control for effect of unmeasured selection factors in observational studies; includes selecting an instrument that mimics the random group allocation of a randomized study. Dependent on having an appropriate and valid instrument. | |

Tools to Use When Designing a Research Study in Older Adults

When designing a research study, a causal diagram, also known as a directed acyclic graph (DAG), is a helpful tool to illustrate relationships between variables of interest. A DAG is a diagram consisting of variables connected by arrows, representing the causal effect of one variable on another.19–23 A sample DAG for selection bias is included in Appendix S3. Detailed guides and tutorials for creating DAGs were published by Hernán and others.7,19,21 Software programs can assist with creating and analyzing causal diagrams, such as DAGitty (www.dagitty.net).24

In geriatrics research, it is important to consider barriers to participation that are unique to older adults and specifically design studies to minimize such barriers.18,25 As an example, for a clinical geriatrics study being conducted in a northern climate, it would be best to collect data during the spring and summer months, rather than the winter months. This choice would help minimize concerns about the frailest study participants missing clinic visits because they are afraid of falling on an icy sidewalk. Another option would be to conduct home visits for data collection. In addition to minimizing barriers to participation, at the study design stage, it is imperative to carefully identify and measure variables that may predict losses to follow-up or study dropout. For instance, variables such as frailty, number of comorbidities, self-rated health, and social support are known to be associated with loss to follow-up in geriatrics research and can all be measured via questionnaire. It is important to measure these variables during data collection because they can then be used during data analysis to explore whether individuals who dropped out differ than those who remained in the study. In the following section we discuss additional analytic tools that can be used to account for selection bias.

Tools to Use When Analyzing a Research Study in Older Adults

Once data have been collected, a number of analytic strategies in the toolkit can be used to investigate selection bias. Calculating descriptive statistics comparing those who dropped out and those who remained in the study is an initial step toward examining potential bias. This will highlight whether there are important differences between those who remained and those who did not, for example, if those who dropped out were more likely to be cigarette smokers or have uncontrolled cardiovascular risk factors. It would be most concerning to find differences in variables strongly associated with the exposure of interest, such as if a study of obesity and mortality found that individuals who dropped out were more likely to have hypertension.

Regression modeling can be used to examine loss to follow-up. Variables associated with loss to follow-up (eg, frailty, self-rated health) would be entered into a regression model, such as a logistic regression model, to determine which variables are important predictors of dropout.7 Sensitivity analysis or bias analysis are analytic tools that can be used to understand whether study results are affected by selection bias.26–30 These are supplementary analyses that involve empirically examining the influence of selection factors on study results. For example, in case study 1, bias analysis could be used to understand the magnitude of selection bias in an analysis that is missing 24% of the study sample because they did not survive to age 75. Another tool that has been well described in the epidemiological literature is inverse probability of censoring weights.2,13 In this approach, an analytic weight is assigned to each individual who remains in the study so that in the analysis they account for themselves, as well as those with similar characteristics who were loss to follow-up.31,32 This effectively up-weights individuals who remain in the study cohort to account for people who have been lost to follow-up.

The Selection Bias Toolkit also contains more advanced techniques to account for selection bias in specific scenarios including principal stratification,33,34 multiple imputation,10,35 and instrumental variables.36–40 Appendix S3 offers additional technical details about each of the analytic methods in the toolkit. The objective of presenting these analytic strategies is to highlight the tools that exist to correct for selection bias in aging research. However, much like epidemiologists rely on geriatricians for their substantive expertise in clinical medicine, our recommendation is that geriatrics researchers collaborate with experts in methods to prevent and treat selection bias to implement the methods described in the toolkit.

In conclusion, selection bias presents an important challenge to the validity of research findings in clinical geriatrics research. Selection bias is a common concern in aging research by virtue of the fact that participants must have survived to old age to be part of a geriatric cohort, and many factors strongly predictive of loss to follow-up are closely linked with aging (eg, frailty, comorbidities).

In this article we described survivor bias and bias due to loss to follow-up using three case studies. As described in the Selection Bias Toolkit, several strategies can be used to investigate and account for selection bias in geriatrics research. Choosing one strategy over another depends on the data available and the scientific question of interest.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1. Glossary of key terms.

Appendix S2. Additional details on methodology for case study 2 using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Appendix S3. Technical details of methods presented in the Selection Bias Toolkit.

Tables S1. Demographic characteristics of participants in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Tables S2. Mortality risk ratios (RR) and risk differences (RD) for quintiles of percent body fat stratified by age (<70 years and ≥ 70 years).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosure:

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship Program.

Sponsor’s Role:

The sponsor did not have any direct role in the design, methods, analysis, or preparation of the article.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weuve J, Proust-Lima C, Power MC, et al. Guidelines for reporting methodological challenges and evaluating potential bias in dementia research. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(9):1098–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weuve J, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, et al. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stovitz SD, Banack HR, Kaufman JS. ‘Depletion of the susceptibles’ taught through a story, a table and basic arithmetic. BMJ Evidence-Based Med. 2018;23(5):199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glymour MM, Mayeda ER, Selby VN. Selection bias in clinical epidemiology causal thinking to guide patient-centered research. Epidemiology. 2016; 27(4):466–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luque-Fernandez MA, Schomaker M, Redondo-Sanchez D, Jose Sanchez Perez M, Vaidya A, Schnitzer ME. Educational note: paradoxical collider effect in the analysis of non-communicable disease epidemiological data: a reproducible illustration and web application. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;48:640–653. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flanders WD, Klein M. Properties of 2 counterfactual effect definitions of a point exposure. Epidemiology. 2007;18(4):453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayeda ER, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Power MC, et al. A simulation platform for quantifying survival bias: an application to research on determinants of cognitive decline. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(5):378–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, et al. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2005;352 (11):1138–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy SE, Allore H, Studenski SA. Missing data: a special challenge in aging research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(4):722–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prospective Studies Collaboration. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1083–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowman K, Delgado J, Henley WE, et al. Obesity in older people with and without conditions associated with weight loss: follow-up of 955,000 primary care patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(2):203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howe CJ, Cole SR, Lau B, Napravnik S, Eron JJJ. Selection bias due to loss to follow up in cohort studies. Epidemiology. 2016;27(1):91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Binder N, Blümle A, Balmford J, Motschall E, Oeller P, Schumacher M. Cohort studies were found to be frequently biased by missing disease information due to death. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;105:68–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitcomb BW, McArdle PF. Collider-stratification bias due to censoring in prospective cohort studies. Epidemiology. 2016;27(2):e4–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaix B, Evans D, Merlo J, Suzuki E. Weighing up the dead and missing: reflections on inverse-probability weighting and principal stratification to address truncation by death. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):129–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacey RJ, Wilkie R, Wynne-Jones G, Jordan JL, Wersocki E, McBeth J. Evidence for strategies that improve recruitment and retention of adults aged 65 years and over in randomised trials and observational studies: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2017;46(6):895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mody L, Miller DK, McGloin JM, et al. Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2340–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staplin N, Herrington WG, Judge PK, et al. Use of causal diagrams to inform the design and interpretation of observational studies: an example from the Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(3):546–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenland S, Pearl J. Causal diagrams. In: Balakrishnan N, Colton T, Everitt B, Piegorsch W, Ruggeri F, Teugels JL, eds. Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Causal Inference. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman &Hall/CRC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole SR, Platt RW, Schisterman EF, et al. Illustrating bias due to conditioning on a collider. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):417–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Textor J, Hardt J, Knüppel S. DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology. 2011;22(5):745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcantonio ER, Aneja J, Jones RN, et al. Maximizing clinical research participation in vulnerable older persons: identification of barriers and motivators. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(8):1522–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maldonado G, McCandless LC, Fox MP, MacLehose RF, Greenland S, Lash TL. Good practices for quantitative bias analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(6):1969–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.VanderWeele TJ. Bias formulas for sensitivity analysis for direct and indirecteffects. Epidemiology. 2010;21(4):540–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiolero A, Paradis G, Kaufman JS. Assessing the possible direct effect of birth weight on childhood blood pressure: a sensitivity analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(1):4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lash T, Fox M, Fink A. Applying Quantitative Bias Analysis to Epidemiologic Data. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orsini N, Bellocco R, Bottai M, Wolk A, Greenland S. A tool for deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analysis of epidemiologic studies. Stata J. 2008;8(1):29–48. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banack HR, Harper S, Kaufman JS. Accounting for selection bias in studies of acute cardiac events. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(6):709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Phiri K, Shapiro R. A simple regression-based approach to account for survival bias in birth outcomes research. Epidemiology. 2015;26(4):473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, Shpitser I, Weuve J. To weight or not to weight?: on the relation between inverse-probability weighting and principal stratification for truncation by death. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1): 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Wetterslev J, Winkel P. When and how should multiple imputation be used for handling missing data in randomised clinical trials—a practical guide with flowcharts. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marden JR, Wang L, Tchetgen EJT, Walter S, Glymour MM, Wirth KE. Implementation of instrumental variable bounds for data missing not at random. Epidemiology. 2018;29(3):364–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Walter S, Vansteelandt S, Martinussen T, Glymour M. Instrumental variable estimation in a survival context. Epidemiology. 2015;26(3):402–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stukel TA, Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Alter DA, Gottlieb DJ, Vermeulen MJ. Analysis of observational studies in the presence of treatment selection bias: effects of invasive cardiac management on AMI survival using propensity score and instrumental variable methods. JAMA. 2007;297(3):278–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gozalo P, Leland NE, Christian TJ, Mor V, Teno JM. Volume matters: returning home after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(10):2043–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rassen JA, Brookhart MA, Glynn RJ, Mittleman MA, Schneeweiss S. Instrumental variables I: instrumental variables exploit natural variation in nonexperimental data to estimate causal relationships. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009; 62(12):1226–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Glossary of key terms.

Appendix S2. Additional details on methodology for case study 2 using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Appendix S3. Technical details of methods presented in the Selection Bias Toolkit.

Tables S1. Demographic characteristics of participants in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Tables S2. Mortality risk ratios (RR) and risk differences (RD) for quintiles of percent body fat stratified by age (<70 years and ≥ 70 years).