Background:

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-12 is highly expressed in abdominal aortic aneurysms and its elastolytic function has been implicated in the pathogenesis. This concept is challenged, however, by conflicting data. Here, we sought to revisit the role of MMP-12 in abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Methods:

Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice were infused with Ang II (angiotensin). Expression of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) markers and complement component 3 (C3) levels were evaluated by immunostaining in aortas of surviving animals. Plasma complement components were analyzed by immunoassay. The effects of a complement inhibitor, IgG-FH1-5 (factor H-immunoglobulin G), and macrophage-specific MMP-12 deficiency on adverse aortic remodeling and death from rupture in Ang II–infused mice were determined.

Results:

Unexpectedly, death from aortic rupture was significantly higher in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice. This associated with more neutrophils, citrullinated histone H3 and neutrophil elastase, markers of NETs, and C3 levels in Mmp12-/- aortas. These findings were recapitulated in additional models of abdominal aortic aneurysm. MMP-12 deficiency also led to more pronounced elastic laminae degradation and reduced collagen integrity. Higher plasma C5a in Mmp12-/- mice pointed to complement overactivation. Treatment with IgG-FH1-5 decreased aortic wall NETosis and reduced adverse aortic remodeling and death from rupture in Ang II–infused Mmp12-/- mice. Finally, macrophage-specific MMP-12 deficiency recapitulated the effects of global MMP-12 deficiency on complement deposition and NETosis, as well as adverse aortic remodeling and death from rupture in Ang II–infused mice.

Conclusions:

An MMP-12 deficiency/complement activation/NETosis pathway compromises aortic integrity, which predisposes to adverse vascular remodeling and abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture. Considering these new findings, the role of macrophage MMP-12 in vascular homeostasis demands re-evaluation of MMP-12 function in diverse settings.

Keywords: angiotensin II, gene deletion, inflammation, macrophages, neutrophils

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Extracellular matrix and matricellular components of the vascular wall play important roles in maintaining integrity and normal function of the arterial wall.

Matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12 or macrophage elastase) is highly upregulated in abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) in humans and multiple mouse models.

Degradation of elastic fibers is a key component of AAA pathogenesis, and MMP-12 is generally considered to play a major role in this process.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

MMP-12 deficiency leads to the activation of the complement system and neutrophil extracellular trap formation and predisposes the aorta to AAA development and rupture.

Macrophage MMP-12 is essential for aortic homeostasis and integrity.

There is conflicting information on the role MMP-12, a highly upregulated elastase, in AAA development. Here, we demonstrate that MMP-12 is crucial for maintaining vascular homeostasis, and MMP-12 deficiency results in complement activation and elevated levels of neutrophil extracellular traps along the aorta, increasing the susceptibility to AAA and its rupture. These findings suggest caution in the use of selective MMP-12 inhibitors as therapeutic agents in AAA and mandate a re-evaluation of previous work on the roles of MMP-12 in various settings.

Editorial, see p 449

Blood vessels experience pathogens intermittently. Activation of the complement system, a mainstay of immune surveillance, is critical to eliminating these pathogens.1 If left unchecked, however, complement activation can also perturb the structural integrity and functionality of the arterial wall, which are normally regulated via homeostatic processes. Control of vascular integrity starts with the endothelial barrier and its interactions with platelets and leukocytes.2,3 Extracellular matrix (ECM) and matricellular components of the vascular wall similarly play important roles in maintaining integrity and normal function.4,5 Matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) mediate proinflammatory signaling, recruitment of inflammatory cells, and degradation of ECM. Accordingly, possible involvement of MMPs in disturbing vascular integrity is often considered in pathologies such as aneurysm, dissection, and rupture.6 This concept has prompted efforts to develop therapeutics to attenuate MMP activity to prevent adverse vascular remodeling and maintain integrity of the wall.6

MMP-12 (also known as macrophage elastase) is a protease best known for its elastolytic function. Degradation of elastic fibers is a key component of aneurysm pathogenesis, and MMP-12 is highly upregulated in abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) in humans and multiple mouse models.7,8 Nevertheless, a widely held concept regarding the role of MMP-12 in aneurysmal pathogenesis and progression is challenged by studies wherein Mmp12 gene deletion in mice (Mmp12-/-) has no effect on elastase-induced aneurysm formation,9 despite reducing CaCl2-induced aneurysm development10 and diminishing aneurysmal rupture in Ang II (angiotensin)–infused mice in the presence of transforming growth factor β neutralization.11 Emerging data indicate further that, in addition to its elastolytic function, MMP-12 modulates inflammation and immunity through regulation of macrophage and neutrophil function, which depending on the context can be anti or proinflammatory.12–17 During our studies aimed at developing specific MMP-12 inhibitors and imaging agents,18 we unexpectedly observed that Mmp12 deletion promotes rather than prevents Ang II–induced AAA development and rupture. Introducing a novel paradigm, we demonstrate that MMP-12 contributes to aortic homeostasis and thus maintaining wall integrity. This finding is linked to the attenuating effect of macrophage MMP-12 on complement overactivation, aortic wall neutrophil infiltration, neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, and elastin degradation.

Methods

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Mouse Models of AAA

Apolipoprotein E-null (Apoe-/-), Mmp12-/- (B6.129X-Mmp12tm1Sds/J), and C57BL/6J mice were all purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice were generated in our laboratory by crossing Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/- mice. B6.129X-Mmp12tm1Sds/J mice were backcrossed into C57BL/6J by Jackson and 32 SNP panel analysis covering all chromosomes has demonstrated that all markers were C57BL/6. The male sex is a risk factor for AAA development and like humans, male mice are more susceptible to Ang II–induced AAA. Therefore, only male mice were used in the study. For the first model of AAA, 12- to 14-week-old male Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice were implanted with an osmotic minipump (model 2004 and 2001, Alzet, respectively) delivering recombinant human Ang II at 1000 ng/kg per minute for up to 4 weeks to induce aneurysm, most often presenting in the suprarenal abdominal aorta (SAA).19 To enhance aneurysm formation in Mmp12-/- and C57BL/6J mice, 12- to 14-week-old male mice were administered a single intraperitoneal injection containing 1.0×1011 genome copies of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) encoding PCSK9 (AAV8.ApoEHCR-hAAT.D377Y-mPCK9.bGH) obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Vector Core to induce hyperlipidemia accompanied by feeding the mice with a high-fat diet (HFD) containing 1.25% cholesterol (D12108, Research Diets).20 Two weeks later, AAA was induced by following the above procedure. For the second model of AAA, 12- to 14-week-old male Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice were used to generate infrarenal AAA as described previously.21 Briefly, animals were treated with β-aminopropionitrile (Sigma) 0.2% in drinking water. Two days after the start of β-aminopropionitrile administration, the animals underwent surgery. The infrarenal abdominal aorta was exposed, and porcine pancreatic elastase (6.67 mg/mL, 10 U/mg, MP Biomedical) was applied topically for 5 minutes. At 4-weeks after surgery, the surviving animals were euthanized for tissue collection.

Generation of Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- and Conditional Macrophage-Specific Mmp12-/ Mice

To generate Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice, B6.129X-Mmp12tm1Sds/J mice from Jackson Laboratory (Stock No: 004855)22 were crossed with B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J mice (ApoE KO, Jackson Lab, Stock No: 002052). Genome scanning of Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice by Jackson laboratories showed 95% of the single-nucleotide polymorphism panel was of C57BL/6J background. To generate macrophage-specific Mmp12 deficient mice, C57BL/6N Mmp12tm1a(EUCOMM)Hmgu/H mice from Infrafrontier GmbH (Munich, Germany, European Mouse Mutant Archive ID:05321) that contain FRT and loxP sites were then crossed with B6.Cg-Tg(Pgk1-flpo)10Sykr/J (FLPo-10, Jackson Lab, Stock No: 011065) to generate Mmp12flox/flox Mice. Next, the FVB macrophage-specific (Csf1r promoter), tamoxifen-inducible Cre-expressing Tg(Csf1r-Mer-iCre-Mer)1Jwp transgenic mice from Jackson Laboratory (Stock No: 019098)23 were crossed with Mmp12flox/flox mice. Mmp12 deletion in macrophages was induced by daily intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen (Sigma‐Aldrich, T5648-1G, dissolved in corn oil) at 75 mg/kg of mouse body weight, every 24 hours for a total of 5 consecutive days with a 7-day waiting period after the final injection for recombination.

Blood Pressure Measurements

Arterial blood pressure was measured continuously in a subgroup of Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice using radiotelemetry for 3 days prior to and up to 9 days after the implantation of Ang II infusing minipump. The blood pressure transducer (TA11PA-C10; Data Sciences International)24 was introduced via a catheter implanted in the left common carotid artery.

Tissue Processing, Histology, Morphometry, and Immunostaining

Animals euthanized at the desired time point were perfused with heparinized saline solution. The aorta was carefully harvested and used for aortic cell isolation and flow cytometry experiments or placed in Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (Tissue Tek), snap frozen, and processed using a cryostat (CM1850, Leica). Serial sections were collected at regular intervals and used for morphometry and immunofluorescence staining.

For morphometric analysis, serial tissue sections of the abdominal aorta were collected and imaged using a microscope (Eclipse E400, Nikon). For tissues with aneurysm, the maximal external diameter was selected for staining and measured using ImageJ/Fiji software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). For immunofluorescence staining, sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature followed by blocking with either 10% normal goat serum or 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 hour. The tissue sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: anti-Ly6G clone 1A8: 1:100, BP0075-1, Bio X Cell; anti-Histone H3 (citrulline R2+R8+R17): 1:100, ab5103, Abcam; antineutrophil elastase: 1:100, ab68672, Abcam; anti-mouse complement component 3 (C3), 55463, MP Biomedicals; anti-tropoelastin antibody: 1:100, ab21600, Abcam; anti-C3d biotinylated: 1:200, BAF2655, R&D Systems; anti-CD68, 1:100, ab53444, Abcam; anti-CD31/PECAM-1, 1:100, MAB1398Z, Millipore Sigma; anti-α-smooth muscle actin, 1:100, A2547,Sigma-Aldrich. Isotype-matched immunoglobulin preparations were used as control to establish staining specificity. The sections were then incubated for 1 hour in a 1:200 dilution of appropriate Alexa Fluor 555 (A-48270, S32355, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (S32356, A-11007 or A-11012, Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mouse Mmp12 RNA transcripts were detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (HuluFish Plus kit, Atto647-MMP-12, Q2022016) following the manufacturer’s protocol. After washing, the slides were mounted using Prolong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (DMi8, Leica) and quantified using ImageJ software. Verhoeff-Van Gieson staining was performed on tissue sections according to the standard protocols by Yale Pathology Tissue Services. R-CHP (collagen hybridizing peptide, Cy3 conjugate, 3Helix) was used to stain for single-stranded collagens. Briefly, a solution of the peptide with a concentration of 20 µM was heated to 80 °C for 5 minute in a water bath in a sealed microtube followed by quenching in an ice-water bath for 15 to 90 seconds and subsequently applied to the tissues and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Finally, images that best represented the overall results were selected and presented as figures.

Quantitation of C3 and Complement Component 5a (C5a) in Mouse Plasma

Mouse plasma C3 or C5a was quantified using a Gyrolab xPlore automated immunoassay system (Gyros Protein Technologies). For plasma C3 assay, the biotin-labeled complement C3-specific monoclonal capture antibody (11H9, Novus NB200-540B) was formulated at 100 µg/mL and Alexa Fluor 647-labeled anti-C3 antibody (MP Biomedicals, 55463) was formulated at the working concentration of 5 µg/mL in Rexxip F buffer (Gyros Protein Technologies, P0004825) for detection of C3. The standard curve for C3 was prepared using purified mouse C3 (CompTech, M113), which was serially diluted and spiked into Rexxip A buffer. The capture and detection antibodies, standards, and unknown plasma samples were placed in the predetermined locations in a PCR plate (Gyros Protein Technologies, P0004861) per manufacturer’s recommendation. Biotin-labeled anti-C3 capture antibody was immobilized on the surface of streptavidin-coated Gyrolab Bioaffy CD200 (Gyros Protein Technologies, P0004180) and plasma samples were loaded. Captured C3 was detected by Alexa Fluor 647-labeled anti-C3 antibody. For C5a quantification, the biotin-labeled monoclonal capture antibody (R&D, MAB21501) was formulated at 100 µg/m and Alexa Fluor 647-labeled anti-C5a antibody (R&D, AF2150) was formulated at 5 µg/mL in Rexxip F buffer (Gyros Protein Technologies, P0004825). The standard curve was prepared by spiking recombinant mouse C5a (R&D, 2150-C5-025) at 150 ng/mL and serially diluting 3-fold in C5-deficient NOD-SCID mouse plasma (BIOIVT, MSE61PLKZYNN). The immune assay then run as described in C3 assay. Concentrations of samples were calculated using Gyrolab software.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was isolated from normal suprarenal abdominal aorta (SAA) as well as bone marrow-derived macrophages (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen) and reverse transcribed (QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit, Qiagen). Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction was performed on a Real-Time PCR System 7500 (Applied Biosystems) using the following TaqMan primers and probe sets (β-actin: Mn00607939_s1, Elastin: Mm00514670_m1, Eln: Mm00500554_m1, Mmp12, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reactions were run in triplicates on the 7500 real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and experimental gene expression was normalized to that of β-actin.

Flow Cytometry

Carefully harvested whole aortas were cut in <1 mm pieces and incubated in a mixture of enzymes (400 U/mL collagenase type I, 120 U/mL collagenase type XI, 60 U/mL hyaluronidase, 60 U/mL DNase1 in PBS-HEPES 20 mM) at 37 °C for 1 hour. The tissue was filtered using a 70-µm cell strainer and aortic cells were resuspended in PBS-FBS 2%. After Fc receptor blocking (Mouse BD Fc Block, BD Biosciences) for 20 minutes at room temperature, cells were labeled with PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD45 (BioLegned, Cat. No. 103105), APC-conjugated anti-mouse Ly6G (BD Biosciences, Cat. No. 560599), and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse CD11b (BD Biosciences, Cat. No. 557672) antibodies for 20 minutes on ice, and used for flow cytometry (LSR II, BD Bioscience) with 7-AAD (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. A1310) to verify cell viability. Data were processed using FlowJo Software. Forward and side scatter density plots were used to exclude debris and to identify single cells. Following selection of 7-AAD- live cells and gating on CD45+ cells, the CD11b and Ly6G signals were further analyzed to identify macrophage and neutrophil populations. An outline of the gating strategy is shown in Figure S1.

Isolation of Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages

Mmp12-/- bone marrow-derived macrophages derived from Csf1r-Mer-iCre-Mer:Mmp12flox/flox mice were isolated using a previously established method.25 Briefly, bone marrow cells were harvested and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/F12 (DMEM/F12; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 11320033) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone), 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin (DMEM/F12-10), and 10 ng/mL macrophage colony–stimulating factor (M-CSF; Enzo Life Sciences, ENZ-PRT144-0010). The harvested cells were counted in a hemacytometer and adjusted to a concentration of ~4×106/mL in the medium. Then, a total of 4×105 cells were added to each sterile plastic petri dish in 10 mL medium and incubated in an incubator at 37 °C, and 5% CO2. On day 3, another 5 mL of macrophage complete medium was added to each dish. After 7 days in culture, nonadherent cells are discarded and adherent cells were harvested for RNA isolation.

Anticomplement Treatment Protocol

Mice (12–18 weeks old) were injected intraperitoneally with a fusion protein consisting of factor H regulatory domains linked to a nontargeting mouse IgG-FH1-5 (factor H-immunoglobulin G, 56 mg/kg), anti-C5 antibody (BB5.1, 40 mg/kg), or control IgG1 MOPC (40 mg/kg), provided by Alexion Pharmaceuticals (New Haven, CT), every 3 days for 9 days prior to AAA induction and the treatment with IgG-FH1-5 or MOPC continued for up to 28 days until completion of the study.

Burst Pressure Tests

The descending thoracic aorta (from the first to fifth pair of intercostal arteries) and the SAA (from the diaphragm to right renal artery) were excised and cleaned of perivascular tissue, then their branches were ligated to allow ex vivo pressurization. The vessels were cannulated and ligated on glass pipettes and placed within a custom computer-controlled extension-inflation mechanical testing device.26 Following both a 15-minute acclimation of the specimen within a Hank’s buffered salt solution at room temperature (to negate smooth muscle contractility, thus focusing on ECM strength) and 90 mm Hg pressure and 4 preconditioning cycles consisting of pressurization from 10 through 140 mm Hg at a fixed value of axial stretch, the in vivo value of axial stretch was estimated for each sample as the value at which the transducer-measured axial force does not change appreciably during cyclic pressurization.27 Once done, the samples were recannulated on a custom blunt-ended double-needle assembly, stretched to the estimated in vivo axial length, and pressurized to failure, as described previously.28

Statistics

All values are expressed as median and interquartile range (Q1–Q3). Data were compared using 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons post hoc test as appropriate. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were compared using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. We did not apply any experiment-wide or across-test multiple testing correction and a P-value <0.05 was considered significant. No animal was excluded over the course of this study. Randomization and blinding were not applied as these measures were not applicable for the comparisons carried out throughout the study.

Study Approval

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the protocols approved by the Yale University and Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Results

MMP-12 Deficiency Promotes AAA Development and Rupture

To examine the role of MMP-12 in AAA, Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice were infused with Ang II at 1000 ng/kg per minute. Consistent with previous reports,19,29,30 this led to death due to aortic rupture in a subset of Apoe-/- mice by 4 weeks after initiating the Ang II infusion. Unexpectedly, death from rupture was significantly greater in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice, with a cumulative probability of survival to 7 days of only 14% for Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- compared to 71% for Apoe-/- mice (Figure 1A). To investigate whether a change in blood pressure response to Ang II infusion influenced this difference in survival, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured in Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- before and after Ang II initiation. As shown in Figure S2, there was no significant difference in either blood pressure or heart rate between the 2 groups of animals. In addition, evaluation of total cholesterol levels showed no difference between the 2 groups of animals (Figure S3).

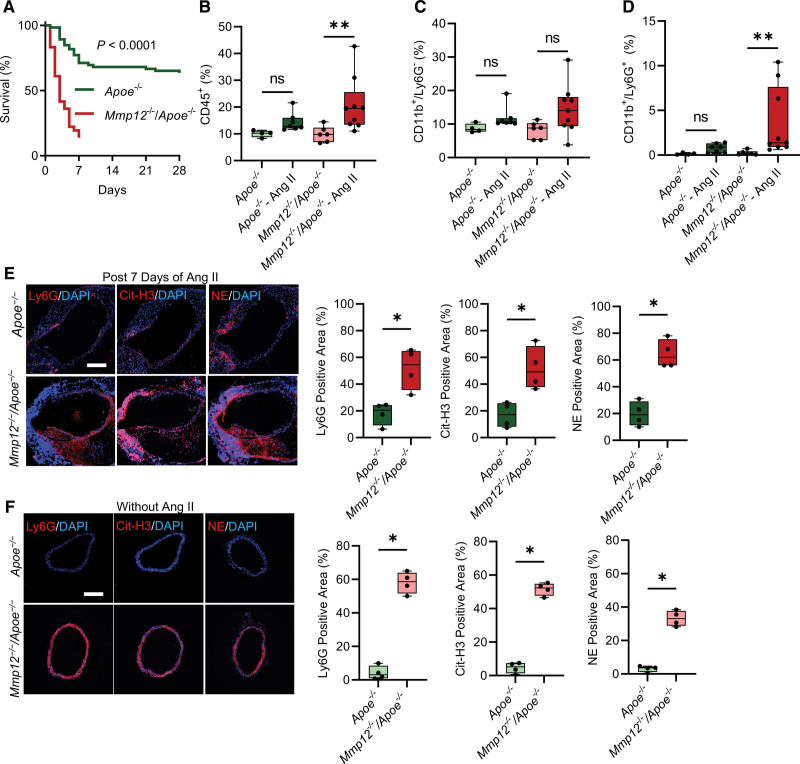

Figure 1.

Effect of Mmp12 deletion on Ang II–induced abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) development and progression in Apoe-/- mice. A, Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Ang II–induced AAA in Apoe-/- (n=66) and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- (n=36) mice. The curves were compared using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test; P<1x10-4. B through D, Flow cytometric evaluation of CD45+ cells (B), CD11b+/Ly6G- mononuclear myeloid cells, primarily macrophages (C), and CD11b+/Ly6G+ neutrophils (D) as % among live cells in aortas of Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice after 18 to 24 hours of Ang II or saline (control) infusion. Values are expressed as means±SD; n=4 to 9 per group; ns, not significant. E and F, Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantification of neutrophils (Ly6G, red), neutrophil extracellular traps (Cit-H3, red), and NE (red) in surviving Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice after 7 days of Ang II infusion (E) and control animals (F). Nuclei are stained blue with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). n=4 per group. Scale bar: 500 µm. *P<0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn multiple comparisons post hoc test (B–D) or by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (E and F). Ang II indicates angiotensin II; Cit-H3, citrullinated histone 3; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; MMP, matrix metalloprotease; and NE, neutrophil elastase.

As inflammatory cell recruitment can play a key role in early stages of aneurysm development,31 we evaluated the effect of Mmp12 deletion on aortic macrophage and neutrophil concentrations before and after Ang II infusion. Due to early loss of Ang II–infused Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice, cell infiltration was measured at 18 to 24 hours post Ang II infusion. Flow cytometry revealed a significant increase in CD45+ cells in both Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice (Figure 1B). Evaluation of the percentage of CD11b+/Ly6G- mononuclear myeloid cells, primarily macrophages, among live cells showed no significant difference at this time post Ang II infusion compared to baseline in either Apoe-/- or Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice and no difference between the 2 groups of animals (Figure 1C). Importantly, however, Ang II infusion significantly increased aortic CD11b+/Ly6G+ neutrophils in both Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice with a significantly higher percentage of neutrophils detected post Ang II infusion in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice compared to Apoe-/- animals, suggesting that MMP-12 may regulate neutrophil recruitment to the vessel wall (Figure 1D).

This significant difference in aortic wall neutrophil infiltration was also detected by Ly6G immunostaining in animals surviving to day 7 post Ang II infusion, with significantly higher neutrophil staining in remodeled SAA in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice compared to Apoe-/- animals (Figure 1E). This led us to assess the effect of Mmp12 deletion on aortic wall NETosis. Immunostaining for citrullinated histone H3 (Cit-H3) and neutrophil elastase (NE), as markers of NET, was also significantly greater in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice compared to Apoe-/- animals (Figure 1E). Strikingly, while neutrophil, Cit-H3, and NE levels were barely detectable in the SAA of Apoe-/-mice at baseline without Ang II infusion, significantly higher neutrophil, Cit-H3, and NE levels were present in the SAA of Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice even at baseline (Figure 1F).

The effect of MMP-12 deficiency on aneurysm development was confirmed in a second murine model, where infrarenal AAA is induced by a combination of oral β-aminopropionitrile administration and perivascular elastase application in Apoe-/- mice. While no significant difference was observed in animal survival to 28 days between Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice (Figure S4A), the maximal external diameter of infrarenal abdominal aorta was significantly larger in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice (2.90 [2.44–3.19] mm) than in Apoe-/- mice (1.50 [1.17–2.25] mm, P<0.01; Figure S4B and S4C) that survived 28 days following surgery. In line with the observations in the first model of AAA, MMP-12 deficiency associated with significantly higher infrarenal abdominal aorta Ly6G-positive neutrophil infiltration and NET deposition in these animals, as evidenced by Cit-H3 and NE immunostaining (Figure S4D).

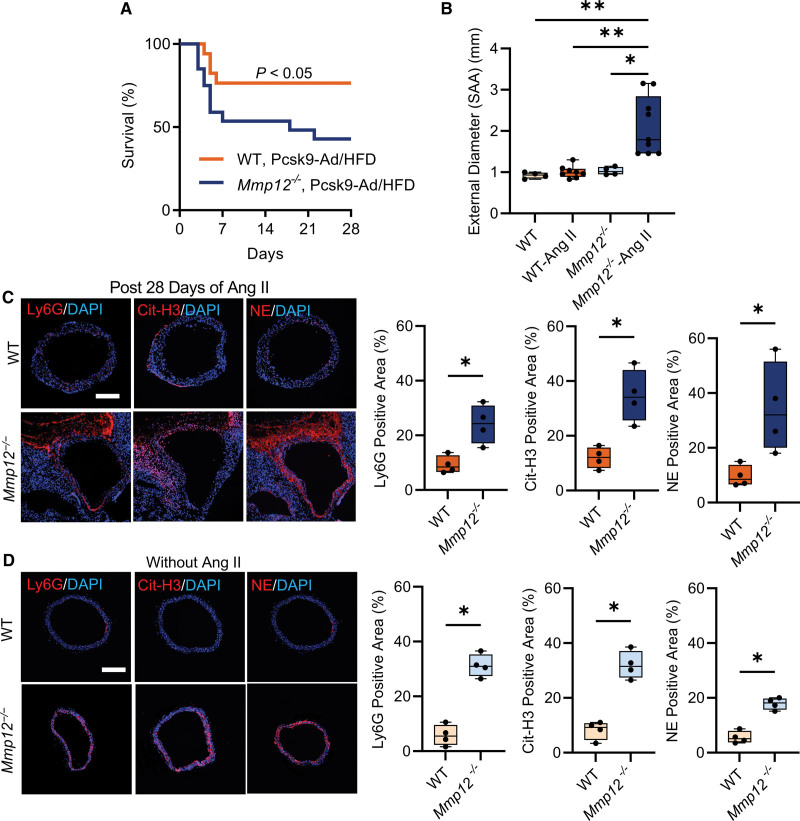

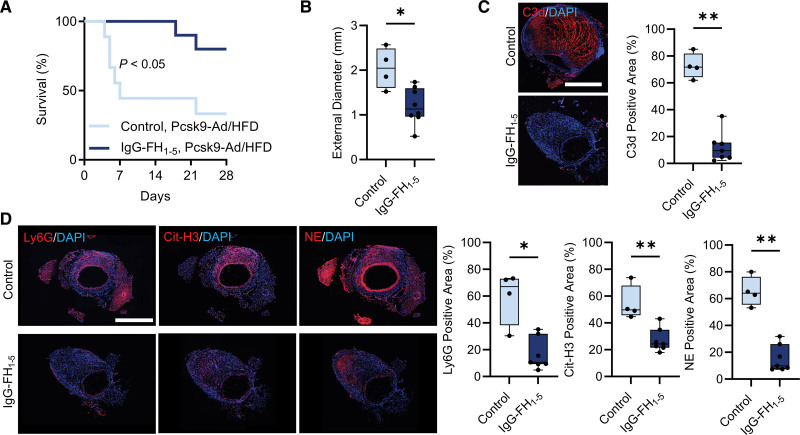

Unlike its effect in Apoe-/- mice, Ang II infusion has a modest effect on AAA induction and animal survival in normolipidemic wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice.19 Therefore, to examine whether the effect of Mmp12 deletion on aneurysm development extends to WT animals, we induced hyperlipidemia in Mmp12-/- and WT mice using a combination of adenovirus expressing gain-of-function proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (AAV8-PCSK9) and a HFD.32 Measurement of total blood cholesterol demonstrated increases in both WT and Mmp12-/- mice upon AAV8-PCSK9/HFD administration, and no significant differences between these 2 groups before or after this intervention (Figure S5). Ang II infusion in these hyperlipidemic animals resulted in significantly lower survival probability at 4 weeks for Mmp12-/- (45%) than WT (77%) mice (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the maximal external diameter of SAA in hyperlipidemic Mmp12-/- mice that survived to 28 days of Ang II infusion (1.79 [1.46–2.84] mm) was significantly larger than the corresponding aortic diameter in hyperlipidemic WT animals (0.93 [0.85–0.99] mm, P<0.01; Figure 2B). This difference associated with higher SAA neutrophil and NET levels, as detected by immunostaining, in these Mmp12-/- mice compared to WT animals (Figure 2C). Like Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice, significantly higher neutrophil infiltration and NET deposition was detectable at baseline, without Ang II infusion, in hyperlipidemic Mmp12-/- mice compared to hyperlipidemic WT animals (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Effect of Mmp12 deletion on Ang II–induced AAA development and progression in hyperlipidemic WT mice. A. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Ang II–induced AAA in hyperlipidemic WT (n=17) and Mmp12-/- (n=20) mice. The curves were compared using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test; P<0.05. B, Quantification of maximal suprarenal abdominal aorta external diameter at baseline (no Ang II) and in animals surviving 4 weeks of Ang II infusion; n=4 to 9. C and D, Representative immunofluorescence staining images and quantification of neutrophils (Ly6G, red), neutrophil extracellular traps (Cit-H3, red), and NE (red) in surviving hyperlipidemic WT and Mmp12-/- mice after 28 days of Ang II infusion (C) and saline-infused control animals (D). Nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. n=4 per group. Scale bar: 500 µm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparisons post hoc test (B), or *P<0.05, by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (C and D). Ang II indicates angiotensin II; Cit-H3, citrullinated histone 3; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; HFD, high-fat diet; MMP, matrix metalloprotease; NE, neutrophil elastase; SAA, suprarenal abdominal aorta; and WT, hyperlipidemic wild type.

Aortic Wall Integrity is Compromised in the Absence of MMP-12

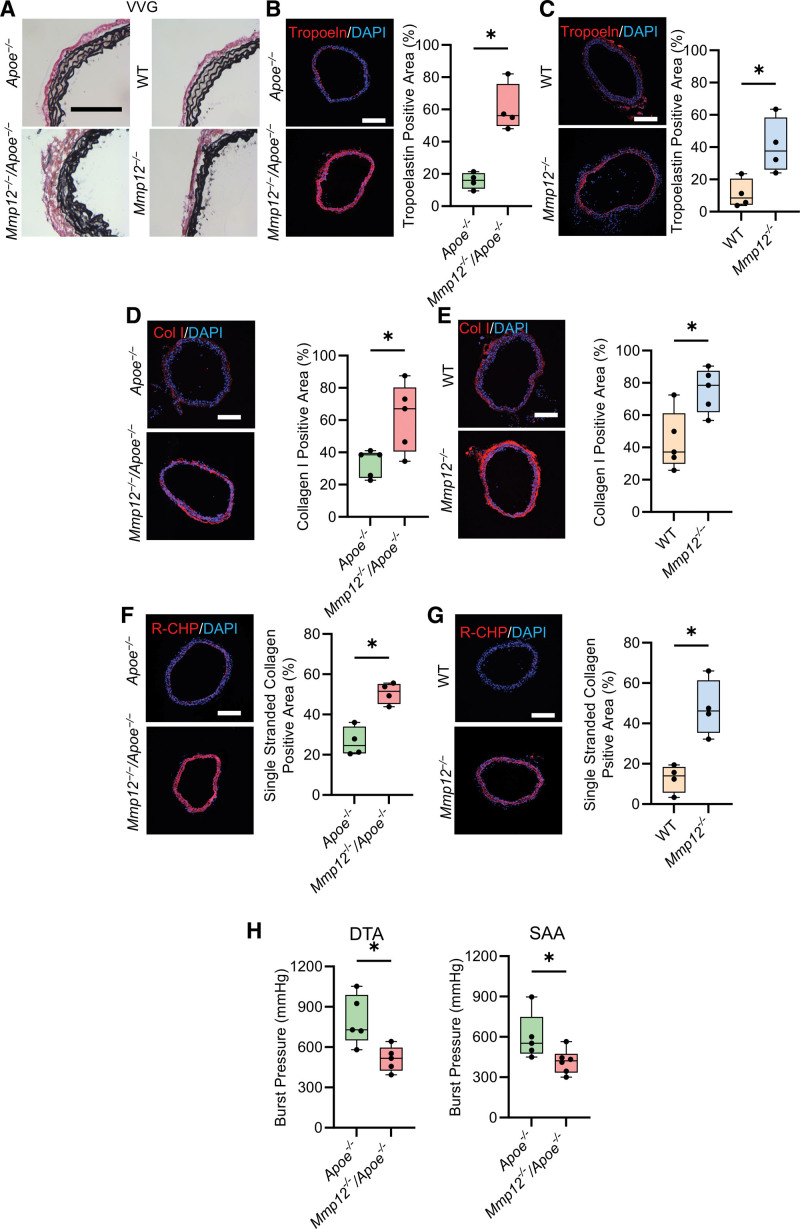

ECM proteins play key roles in maintaining aortic wall integrity, with mechanical properties of the aorta determined largely by elastic fibers and fibrillar collagen.33 Verhoeff-Van Gieson staining revealed disrupted elastic laminae with dense and irregular fibers in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/- mice (Figure 3A). This was associated with significantly higher tropoelastin expression in these animals, as detected by immunostaining (Figure 3B and 3C) and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (Figure S6), than in Apoe-/- and WT mice. MMP-12 deficiency also associated with increased collagen remodeling, with higher collagen I (Figure 3D and 3E) and single-stranded collagen α-chains (Figure 3F and 3G) detected by immunostaining in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/- mice than in Apoe-/- and WT mice. Together, these results point to extensive aortic wall ECM remodeling in the absence of MMP-12, although without insight into the structural competence of the synthesized fibers. Comparison of the burst pressure, an indicator of the biomechanical strength of the aorta, showed significantly lower values in both the descending thoracic aorta and SAA of Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice compared to Apoe-/- animals (respectively, 516 [425–597] versus 729 [651–989] mm Hg, P<0.05 and 422 [334–474] versus 553 [476–749] mm Hg, P<0.05; Figure 3H).

Figure 3.

Effect of Mmp12 deficiency on aortic wall extracellular matrix composition. A, Representative examples of Verhoeff–van Gieson (VVG) staining of SAA in Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- (left column) and WT and Mmp12-/- (right column) mice. Scale bar: 250 µm. B through G, Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantification of tropoelastin (red, B and C), collagen type I (red, D and E) and single-stranded collagen using R-CHP (red, F and G) in Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- (B, D, and F) and WT and Mmp12-/- (C, E, and G) mice. Nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. n=4 per group. Scale bar: 500 µm. H, Burst pressure, as a functional readout of wall strength, of DTA and SAA in Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice. n=5 to 6 per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (B through H). DAPI indicates 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DTA, descending thoracic aorta; MMP, matrix metalloprotease; R-CHP, collagen hybridizing peptide, Cy3 conjugate; SAA, suprarenal abdominal aorta; and WT, wild-type.

Complement Overactivation Mediates the Effect of MMP-12 Deficiency on Aortic Wall NETosis

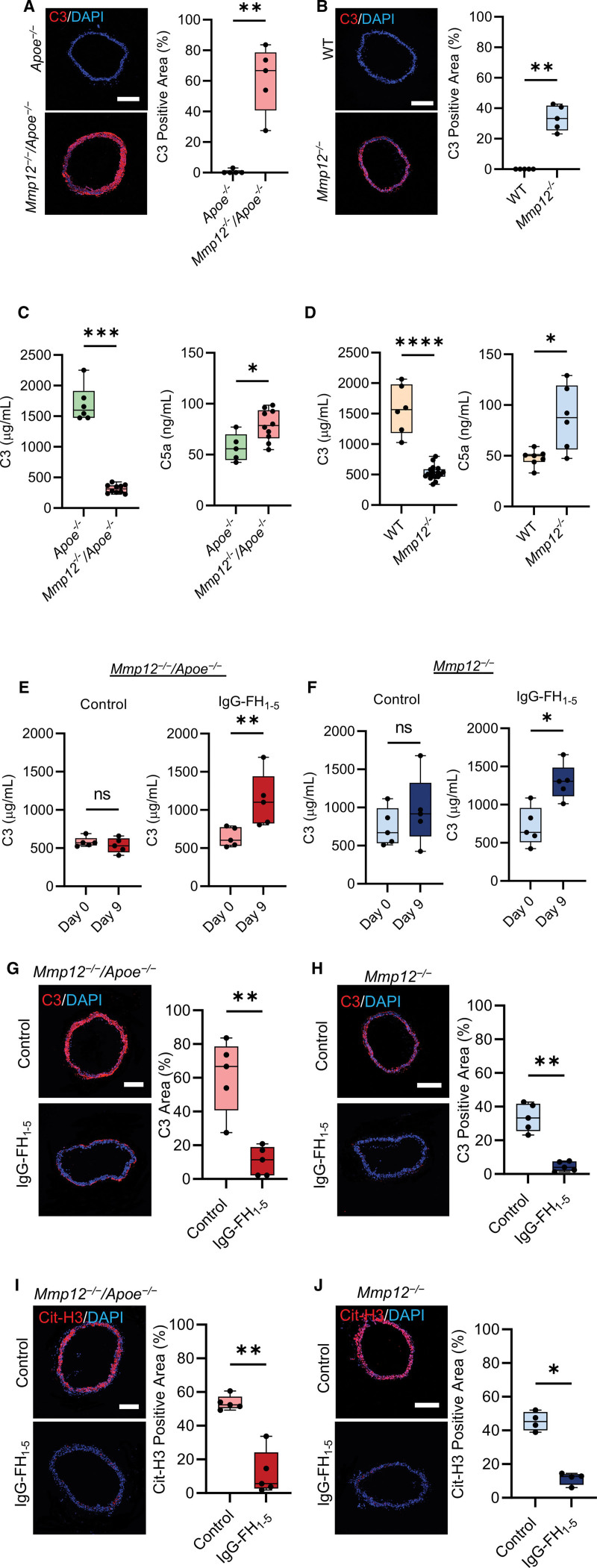

Aortic wall neutrophil infiltration and NETosis in the absence of MMP-12, in conjunction with the interplay between complement overactivation and NETosis,34 led us to investigate the roles of the complement system in the aforementioned observations. Immunofluorescence staining showed significantly higher C3 deposition in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/- aortas compared to Apoe-/- and WT vessels, respectively, potentially pointing to aberrant complement activation in MMP-12-deficient mice (Figure 4A and 4B). Analysis of plasma complement components showed significantly lower C3 levels in both Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- vs Apoe-/- (313 [253–371] versus 1600 [1473–1912] µg/mL, P<0.01) and Mmp12-/- versus WT (528 [465–800] versus 1565 [1182–1979] µg/mL, P<0.05) mice, indicating a dysregulation of complement system with higher C3 consumption. This was associated with higher levels of C5a, a potent chemoattractant anaphylatoxin for neutrophils, in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- versus Apoe-/- (79 [66–94] versus 56 [45–70] ng/mL, P<0.05) and Mmp12-/- versus WT (88 [56–119] versus 48 [44–52] ng/mL, P<0.05) mice (Figure 4C and 4D).

Figure 4.

Effect of Mmp12 deletion on aortic wall complement deposition. A and B, Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantification of C3 deposits (red) in suprarenal abdominal aorta of Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- (A), and WT and Mmp12-/- (B) mice. Nuclei are stained with DAPI in blue. n=5 per group. Scale bar: 500 µm. C and D, Plasma C3 and C5a levels of Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- (C), and WT and Mmp12-/- (D) mice. n=5 to 10 per group. E and F, Plasma C3 levels in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- (E) and Mmp12-/- (F) mice at baseline and 9 days of treatment with IgG-FH1-5 (factor H-immunoglobulin G) or MOPC antibody (control). n=5 per group. G and H, Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantification of C3 (red) in suprarenal abdominal aorta of Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- (G) and Mmp12-/- (H) mice after 9 days of treatment with IgG-FH1-5 or MOPC antibody (control). n=5 per group; Scale bar: 500 µm. I and J, Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantification of Cit-H3 (red) in suprarenal abdominal aorta of Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- (I) and Mmp12-/- (J) mice after 9 days of treatment with IgG-FH1-5 or MOPC antibody (control). n=4 to 5 per group. Scale bar: 500 µm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ****P<1x10-4 by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (A through J). Cit-H3 indicates citrullinated histone H3; C3, complement component 3; C5a, complement component 5a; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; IgG-FH1-5, factor H-immunoglobulin G; MMP, matrix metalloprotease; and WT, wild-type.

Next, we assessed the efficacy of different strategies in blocking complement activation and potentially clearing NET deposits in MMP-12 deficient animals. Administration of an anti-C5 antibody (BB5.1), which inhibits C5 activation, for 9 days at doses typically used for in vivo blocking studies35 did not have any significant effect on C3 plasma levels but modestly reduced NET deposits in the vessel wall in Mmp12-/- mice (Figure S7). Therefore, we assessed the efficacy of an upstream inhibitor of complement alterative pathway (AP) activation, IgG-FH1-5, a fusion protein consisting of factor H regulatory domains (FH1-5) linked to a nontargeting mouse immunoglobulin.36 Plasma analysis confirmed the consistent presence of FH1-5 in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice injected with the inhibitor (56 mg/kg, IP) every 3 days (Figure S8). Inhibition of AP activity by IgG-FH1-5 treatment resulted in significantly increased plasma C3 levels in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- (603 [529.5–776] µg/mL at day 0 versus 1100 [824–1440] µg/mL at day 9, P<0.01) and Mmp12-/- (637 [507–957] µg/mL at day 0 versus 1305 [1110–1486] µg/mL at day 9, P<0.05) mice (Figure 4E and 4F). The increase in plasma C3 level associated with a significant decrease in aortic C3 deposition in MMP-12 deficient mice (Figure 4G and 4H). More importantly, IgG-FH1-5 treatment markedly cleared the aortic wall NETosis, as detected by Cit-H3 immunostaining, in both Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/- mice (Figure 4I and 4J).

Complement Inhibition Ameliorates Aneurysm Development and Rupture in Mmp12-/-Mice

Given the effect of complement inhibition in clearing NET deposits in MMP-12 deficient mice, and the role of NETosis in aneurysm development,37 we sought to determine whether IgG-FH1-5 can reverse the effect of MMP-12 deficiency on AAA development and rupture. MMP-12-deficient mice pretreated with IgG-FH1-5 for 9 days were infused with Ang II for 28 days while the treatment continued. Compared to the control IgG1 (MOPC-31C) antibody, IgG-FH1-5 treatment had no significant effect on survival in the more aggressive phenotype, Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice (Figure S9). However, in the less severe, Mmp12-/--AAV8-PCSK9/HFD model, IgG-FH1-5 treatment significantly improved survival probability compared to control IgG1 (80% versus 40%, P<0.05; Figure 5A). Furthermore, the maximal SAA external diameter in IgG-FH1-5-treated mice that survived to 28 days (1.20 [0.96–1.60] mm) was significantly lower than the corresponding aortic diameter in Mmp12-/- animals treated with control IgG1 (2.04 [1.61–2.50] mm, P<0.05; Figure 5B). Moreover, in surviving IgG-FH1-5-treated mice, aortic wall C3d deposition was significantly lower compared to the control group (Figure 5C), and IgG-FH1-5 significantly decreased neutrophil infiltration and NET deposits in the remodeled aortic wall of Ang II-infused Mmp12-/- mice compared to the control antibody (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Effect of IgG-FH1-5 on (factor H-immunoglobulin G) survival during Ang II (angiotensin II) infusion in Mmp12-/- mice. A. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Ang II–infused Mmp12-/- mice following Pcsk9-Ad injection and HFD, treated with either IgG-FH1-5 or MOPC antibody as control (n=10 per group). The curves were compared using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, P<0.05. B, Quantification of maximal suprarenal abdominal aorta external diameter after 4 weeks of Ang II infusion in surviving Mmp12-/- mice treated with either IgG-FH1-5 or MOPC antibody, n=4 to 8 per group. C, Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantification of complement component 3d (C3d, red) deposition in suprarenal abdominal aorta of surviving IgG-FH1-5- or MOPC-treated Mmp12-/- mice after 28 days of Ang II infusion. Nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. n=4 to 7 per group; Scale bar: 500 µm. D, Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantification of neutrophils (Ly6G, red), NETs (Cit-H3, red), and NE (red) in suprarenal abdominal aorta of surviving IgG-FH1-5- or MOPC-treated Mmp12-/- mice after 28 days of Ang II infusion. Nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. n=4 to 7 per group; Scale bar: 500 µm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (B through D). Cit-H3 indicates citrullinated histone 3; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; HFD, high-fat diet; IgG-FH1-5, factor H-immunoglobulin G; NE, neutrophil elastase; and NET, neutrophil extracellular trap.

Macrophage MMP-12 Deficiency Recapitulates the Effect of Global MMP-12 Deficiency on Aortic Wall Complement Deposition and NETosis

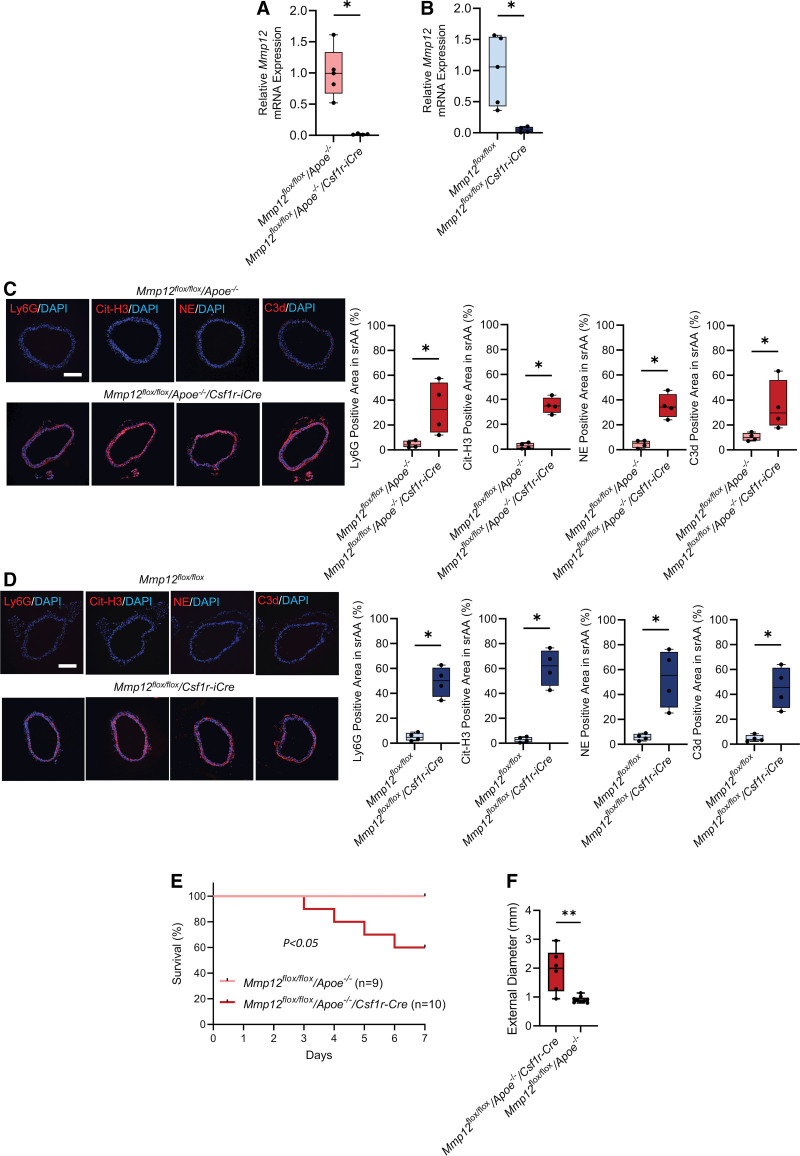

Macrophages are a major source of MMP-12. Therefore, to determine whether the MMP-12 involved in regulating vascular integrity originates in macrophages, Mmp12flox/flox/Csf1r-iCre and Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/-/Csf1r-iCre mice were generated. Inducible ablation of Mmp12 was confirmed in cultured bone marrow-derived macrophages from Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/-/Csf1r-iCre and Mmp12flox/flox/Csf1r-iCre mice treated with tamoxifen for 5 consecutive days (Figure 6A and 6B). Mmp12 fluorescence in situ hybridization in conjunction with immunostaining of aortic sections from tamoxifen-treated mice confirmed Mmp12 deletion in macrophages with no detectable effect in endothelial cells or vascular smooth muscle cells (Figures S10 and S11). This was associated with significantly higher neutrophil, NET, NE, and C3d staining in tamoxifen-treated Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/-/Csf1r-iCre and Mmp12flox/flox/Csf1r-iCre mice compared to control, Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/- and Mmp12flox/flox mice (Figure 6C and 6D). Furthermore, higher collagen and tropoelastin levels were observed in both Mmp12flox/floxCsf1r-iCre and Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/-/Csf1r-iCre mice compared to control (Figure S11). Ang II infusion resulted in significantly lower 7-day survival in Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/-/Csf1r-iCre compared to Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/- (Figure 6E). In addition, the maximal SAA external diameter of surviving mice was significantly higher in Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/-/Csf1r-iCre (1.99 [1.20–2.54] mm) compared to Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/- mice (0.90 [0.83–0.98] mm, P<0.01; Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Effect of macrophage Mmp12 deficiency on aortic composition and Ang II (angiotensin II)–induced abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) development and survival. A and B, Relative β-actin-normalized Mmp12 gene expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages from Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/- and Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/-/Csf1r-iCre (A), and Mmp12flox/flox and Mmp12flox/flox/Csf1r-iCre (B) mice at 5 to 6 weeks post-tamoxifen administration. n=4 to 5 per group; *P<0.05. C and D, Representative images of immunofluorescence staining and quantification of Neutrophils (Ly6G, red), NETs (Cit-H3, red), and complement component 3d (C3d, red) in suprarenal abdominal aorta of Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/- and Mmp12flox/flox/Apoe-/-/Csf1r-iCre (C) and Mmp12flox/flox and Mmp12flox/flox/Csf1r-iCre (D) mice at 5 to 6 weeks post-tamoxifen administration. Nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. n=4 per group. Scale bar: 500 µm. *P<0.05, 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (A through D). E, Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Ang II–infused Mmp12 flox/flox/Apoe-/- (n=9) and Mmp12 flox/flox/Apoe-/-/Csf1r-iCre (n=10) mice post-tamoxifen administration. The curves were compared using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. P<0.05. F, Quantification of maximal suprarenal abdominal aorta external diameter of the surviving mice. **P<0.01 by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. Cit-H3 indicates citrullinated histone 3; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; MMP, matrix metalloprotease; NE, neutrophil elastase; and NET, neutrophil extracellular trap.

Discussion

This study provides new insight into MMP-12 as a key contributor to aortic homeostasis. In the absence of MMP-12, activation of the complement system leads to NETosis and adverse ECM remodeling, including degradation of elastic laminae and compromised collagen integrity. Combined, these changes reduce aortic wall strength and can predispose the aorta to dilatation and rupture in the presence of aneurysmal stimuli.

Elevated MMP-12 expression in human AAA specimens, in conjunction with elastase activity and association with residual elastic fiber fragments, contributed to the prevailing paradigm that MMP-12 has a direct role in promoting AAA pathogenesis, progression, and rupture.7 This presumed role of MMP-12 in the natural history of AAA is challenged, however, by a finding in Mmp12-/- mice that MMP-12 deficiency has no effect on elastase-induced aneurysm formation,9 despite its deficiency reducing CaCl2-induced aneurysm development10 and diminishing aneurysm rupture in Ang II–infused mice in the presence of transforming growth factor β neutralization.11 Our data show that macrophage MMP-12 contributes to the maintenance of aortic integrity and its deficiency promotes aneurysm development and rupture triggered by Ang II or elastase/β-aminopropionitrile in 3 murine models of AAA in the presence or absence of apolipoprotein E deficiency. Although differences across these studies depend, in part, on the specific mouse model studied, including differences in genetic background (129 in9 and10 versus C57BL6 in11 and the present study),38 the experimental trigger for aneurysm (elastase9 versus CaCl210 or Ang II11), and the biological context (transforming growth factor β neutralization11 versus absence of apo E vs no such intervention), our data support a challenge to the prevailing paradigm. A similar discrepancy exists regarding MMP-2 and MMP-9 deficiency. Ang II infusion (1500 µg/kg per day) leads to more severe aortic dilatation in Mmp2-/- mice compared to WT controls39 and MMP-9 deficiency promotes Ang II (1 µg/kg per minute)-induced aortic rupture in Apoe-/- mice.40 Conversely, MMP-2 and MMP-9 deficiency protects mice from CaCl2-induced aortic aneurysm.39,41 Notably, collagenase resistance in ColR/R/Apoe−/− mice, which leads to accumulation of fibrillar collagen promotes the disruption of elastic laminae and accelerates Ang II–induced AAA development.42 Similarly, we show that the effect of MMP-12 deficiency on aortic integrity extends beyond the response to Ang II infusion, and there are major biological and structural changes in the aorta in the absence of any other manipulation.

The detrimental effect of MMP-12 deficiency (which was not associated with any significant difference in aortic Mmp2, Mmp3, Mmp9 and Mmp13, or Timp2 and Timp3 mRNA expression between Apoe-/- and Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice [not shown]) does not necessarily indicate that higher levels of MMP-12 is beneficial in AAA. MMPs are multifunctional proteases, and their proteolytic actions can result in the release of additional biologically active molecules. In the absence of MMP-12, there is neutrophil infiltration and high levels of NE in the vessel wall, which may contribute to elastin degradation and vessel wall weakening. In this regard, some studies have reported biphasic actions of MMPs, for instance, in the context of stroke, where MMPs initially have a deleterious effect but subsequently aid in remodeling and recovery.43 Considering the multifaceted functions of MMPs, it would not be surprising if MMP-12 is found to have different effects at different levels and in different stages of aneurysm development.

While Mmp12-/- mice have been studied for >2 decades, they are not known to exhibit overt cardiovascular abnormalities. Our finding that MMP-12 deficiency has profound effects on vessel wall structural integrity raises the possibility that missing this baseline abnormality may have affected the interpretation of some, if not most of the previous studies in this area. Indeed, while many of the earlier studies focused on the role of MMP-12 as an elastase, more recent studies indicate that MMP-12 also plays protective roles by resolving inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis,44,45 attenuating lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation,12 limiting myocardial infarction,16 and defending against bacterial13 and viral14 infections. In this context, our findings introduce a new paradigm regarding the role of MMP-12 in vascular biology that may have major implications regarding the role of this metalloproteinase in other pathologies.

The complement system consists of a complex array of proteins arranged in a proteolytic cascade that, once activated, produces potent effector molecules impacting innate and adaptive immunity. The 3 complement pathways that initiate the cascade (classical, lectin, and alternative) all culminate in the generation of C3 convertases, which cleave C3 into C3a (a chemotactic mediator of inflammation) and C3b (an opsonin), and subsequently C5 convertases cleaving C5 into C5a (another chemotactic mediator of inflammation) and C5b, which mediates the assembly of membrane attack complex.46,47 A low-level constitutive activation of the AP, the so-called tick-over phenomenon, is an integral part of immune surveillance to monitor the presence of pathogens.46 Activation and amplification of the AP is tightly regulated by soluble and membrane-associated regulators. Several studies have demonstrated the presence of activated complement components in human and experimental vascular pathologies, including AAA,48 and blocking the activity of properdin, a positive regulator of AP, has prevented elastase-induced murine AAA.49 Similarly, we observed considerable complement activation, as manifested by aortic wall C3 deposits and a reduction in plasma C3 levels in our murine models of AAA, and IgG-FH1-5 treatment reduced vascular remodeling and aneurysm rupture.

Complement activation in the absence of MMP-12 and its inhibition by IgG-FH1-5 in our study point to the activation of the AP and suggests that MMP-12 serves as a negative regulator of complement activation. This is in line with a recent proteomic analysis of MMP-12 substrates that identified several members of the complement system, including C3, C3a, and C5a, as MMP-12 substrates.44 The functional significance of this MMP-12 effect has been shown in a model of collagen-induced arthritis, where higher levels of inflammation and tissue damage occurred in Mmp12-/- mice (on a 129Sv/Ev background). Interestingly, no difference was observed at baseline between these animals and wild-type controls. This is in contrast with our observation in Mmp12-/- mice (on a C57BL/6J background), which exhibited considerable systemic complement activation and complement deposition that could be resolved with administration of IgG-FH1-5, suggesting that MMP-12 deficiency may potentiate the low-level tick-over complement activation and render the aorta more prone to adverse effects. As such, MMP-12 is a key component of homeostatic mechanisms that maintain vessel wall integrity. There is, however, a need to consider further the possible role of modifier genes given the different results in mice having different backgrounds.

Complement activation can trigger NET formation and NETs can serve as a platform for complement activation.34 NETs, extracellular meshes of chromatin and granule proteins, are released by neutrophils primarily through a cell death process, NETosis.50 This process and non-lytic NET release are major players in the immune defense against pathogens. If left unchecked, however, this process can lead to excessive tissue damage by promoting complement activation, inflammation, and thrombosis. Several vascular pathologies, including atherosclerosis and AAA, associate with NETosis. Indeed, NETs contain large quantities of NE, a key protease in AAA formation51 and treatment with the NETosis inhibitor, Cl-amidine, attenuates adverse vascular remodeling in AAA.52 Similarly, our study associated AAA formation with complement activation and NETosis in 3 distinct murine models. Moreover, these processes were amplified in the absence of MMP-12, which exacerbated vascular remodeling and aneurysm rupture in Mmp12-/- mice. Importantly, MMP-12 deficiency also led to vessel wall neutrophil infiltration and NETosis in the absence of AAA induction, which cleared upon IgG-FH1-5 treatment. This NETosis associated with elastic laminae degradation and frustrated collagen remodeling, which manifested functionally as a weakened aortic wall with lower burst pressure. Burst pressure studies of aortas from MMP-12 deficient mice revealed lower values in both the descending thoracic and suprarenal abdominal aorta (SAA). Regardless of the presence or absence of MMP-12, and as reported by others,39,53,54 Ang II infusion led to the development of aneurysm (and dissection) in the SAA and occasionally, thoracic aorta. Combined, these data link MMP-12 deficiency to complement activation and NETosis of the aorta, which promotes vessel wall inflammation, weakens the vessel wall, and predisposes the aorta to adverse remodeling and rupture in response to aneurysmal stimuli.

To establish the role of complement activation, we leveraged the differences in the AAA severity between Apoe-/- and AAV8-PCSK9/HFD models. We observed higher incidence of AAA dilatation, rupture, and death with Ang II infusion in Mmp12-/-/Apoe-/- mice compared to Mmp12-/- mice on a high-fat diet when injected with AAV8-PCSK9. Apo E is a glycoprotein component of several lipoprotein particles, which through binding to LDL receptors enables their hepatic clearance. Accordingly, Apo E deficiency leads to hyperlipidemia.55 This mechanism of action is distinct from PCSK9, a serine protease that binds to hepatic LDL receptors and promotes their lysosomal degradation. Thus, similar to Apo E deficiency, adenovirus-mediated PCSK9 overexpression elevates plasma cholesterol levels in mice, a process that is enhanced with a high-fat diet.55 In addition to its effect on lipid metabolism, however, Apo E also impacts lipid peroxidation, inflammation, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and platelet aggregation.56–58 As a result, Apoe-/- mice display a proinflammatory milieu,55 which may have contributed to the more severe phenotypes detected in these animals.

Normal arteries express low levels of MMP-12. To study the effect of macrophage MMP-12 in vascular remodeling, we relied on an inducible Csf1r-Cre system, which is classically used to target macrophages. The effect of the Csf1r-iCre system can also be detected in dendritic cells, granulocytes, and lymphocytes,59 yet, macrophages are classically considered the primary source of MMP-12 and MMP-12 expression is not detectable in normal blood cells.60–62 Demonstration that macrophage MMP-12 is necessary for maintaining aortic wall integrity points to a new role for macrophages in regulating vascular homeostasis.63–65 Future studies should establish whether activation of the complement system is systemic or local, and if so, which tissues are more susceptible to complement-mediated damage in the absence of MMP-12. The observation that a relatively short period of MMP-12-deficiency alters aortic integrity also raises the possibility that genetic and nongenetic factors that modulate MMP-12 expression may predispose to AAA and other vascular pathologies. In this regard, it is noteworthy that polymorphisms in MMP-12 gene that reduce its level associate with higher predisposition to coronary artery disease and large artery atherosclerotic stroke.66

In conclusion, this study suggests a novel role for macrophage MMP-12 in maintaining aortic integrity based on identification of an MMP-12 deficiency/complement activation/NETosis pathway that leads to adverse aortic remodeling and AAA rupture in multiple mouse models. These findings also suggest caution in the use of selective MMP-12 inhibitors as therapeutic agents in AAA and other pathologies such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.67,68 Finally, considering these new findings, the role of MMP-12 in vascular homeostasis may mandate a re-evaluation of previous work on the roles of MMP-12 in various settings.

Article Information

Author Contributions

M. Salarian participated in conducting experiments, acquiring data, analyzing data, writing the manuscript, and approving the final article. M. Ghim and J. Toczek participated in conducting experiments, acquiring data, analyzing data, editing the manuscript, and approving the final article. J. Han, D. Weiss, B. Spronck, A. Ramachandra, G. Kukreja, J. Zhang, and D. Lakheram participated in conducting experiments, acquiring data, analyzing data, and approving the final article. J. Jung participated in conducting experiments, acquiring data, analyzing data, editing the manuscript, and approving the final article. S. Kim and J. Humphrey participated in designing research studies, analyzing data, editing the manuscript, and approving the final article. M. Sadeghi participated in designing research studies, analyzing data, providing reagents, writing the manuscript, editing the manuscript, and approving the final article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Yale West Campus Imaging Core for the support and assistance in this work. We also thank Medical Research Council Harwell Institute, Mary Lyon Centre (UK) and INFRAFRONTIER/EMMA (www.infrafrontier.eu) for providing the mutant mouse line Mmp12tm1a(EUCOMM)Hmgu/H.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants from NIH (R01 HL138567, R01 AG065917, U01 HL142518, and U54DK106857), Department of Veterans Affairs (I0-BX004038), and NIH T32 training grant (5T32HL007950). B. Spronck was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (No. 793805) and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (Rubicon 452172006). We acknowledge the assistance of the George M O’Brien Kidney Center at Yale (NIH grant P30 DK079310) for blood pressure measurements.

Disclosures

J. Jung has ownership and income, Arvinas, Inc. J. Toczek has Yale patent application regarding the New tracers for MMP imaging. D. Lakheram is an employee of Alexion Pharmaceuticals. S. Kim is an employee of Alexion Pharmaceuticals. M. Sadeghi is a spouse employee of Boehringer Ingelheim; has Yale patent application regarding the New tracers for MMP imaging. The other authors report no conflicts.

Supplemental Material

Figures S1–S12

Supplemental Statistical Analysis Data

Major Resources Table

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AAA

- abdominal aortic aneurysms

- AAV8-PCSK9

- adeno-associated viral vector serotype 8 expressing gain-of-function proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

- Ang II

- angiotensin II

- C3

- complement component 3

- C5a

- complement component 5a

- Cit-H3

- citrullinated histone H3

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- HFD

- high-fat diet

- IgG-FH1-5

- factor H-immunoglobulin G

- MMP

- matrix metalloprotease

- NE

- neutrophil elastase

- NET

- neutrophil extracellular trap

- R-CHP

- collagen hybridizing peptide, Cy3 conjugate

- SAA

- suprarenal abdominal aorta

- WT

- wild-type

ORCID iD for Mehran M. Sadeghi: 0000-0002-5074-3510

M. Salarian and M. Ghim contributed equally.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 446.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.322096.

References

- 1.Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:785–797. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosentino F, Lüscher TF. Maintenance of vascular integrity: role of nitric oxide and other bradykinin mediators. Eur Heart J. 1995;16:4–12.. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/16.suppl_k.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho-Tin-Noé B, Boulaftali Y, Camerer E. Platelets and vascular integrity: how platelets prevent bleeding in inflammation. Blood. 2018;131:277–288. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-742676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halabi CM, Broekelmann TJ, Lin M, Lee VS, Chu ML, Mecham RP. Fibulin-4 is essential for maintaining arterial wall integrity in conduit but not muscular arteries. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1602532. Doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Döring Y, Noels H, van der Vorst EPC, Neideck C, Egea V, Drechsler M, Mandl M, Pawig L, Jansen Y, Schröder K, et al. Vascular cxcr4 limits atherosclerosis by maintaining arterial integrity: evidence from mouse and human studies. Circulation. 2017;136:388–403. Doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slack MA, Gordon SM. Protease activity in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:e210–e218. Doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curci JA, Liao S, Huffman MD, Shapiro SD, Thompson RW. Expression and localization of macrophage elastase (matrix metalloproteinase-12) in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1900–1910. doi: 10.1172/jci2182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellenthal FA, Buurman WA, Wodzig WK, Schurink GW. Biomarkers of aaa progression. Part 1: extracellular matrix degeneration. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:464–474. Doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyo R, Lee JK, Shipley JM, Curci JA, Mao D, Ziporin SJ, Ennis TL, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Thompson RW. Targeted gene disruption of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase b) suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1641–1649. doi: 10.1172/jci8931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longo GM, Buda SJ, Fiotta N, Xiong W, Griener T, Shapiro S, Baxter BT. Mmp-12 has a role in abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. Surgery. 2005;137:457–462. Doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Ait-Oufella H, Herbin O, Bonnin P, Ramkhelawon B, Taleb S, Huang J, Offenstadt G, Combadiere C, Renia L, et al. Tgf-beta activity protects against inflammatory aortic aneurysm progression and complications in angiotensin ii-infused mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:422–432. doi: 10.1172/jci38136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean RA, Cox JH, Bellac CL, Doucet A, Starr AE, Overall CM. Macrophage-specific metalloelastase (mmp-12) truncates and inactivates elr+ cxc chemokines and generates ccl2, -7, -8, and -13 antagonists: potential role of the macrophage in terminating polymorphonuclear leukocyte influx. Blood. 2008;112:3455–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houghton AM, Hartzell WO, Robbins CS, Gomis-Ruth FX, Shapiro SD. Macrophage elastase kills bacteria within murine macrophages. Nature. 2009;460:637–641. doi: 10.1038/nature08181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchant DJ, Bellac CL, Moraes TJ, Wadsworth SJ, Dufour A, Butler GS, Bilawchuk LM, Hendry RG, Robertson AG, Cheung CT, et al. A new transcriptional role for matrix metalloproteinase-12 in antiviral immunity. Nat Med. 2014;20:493–502. doi: 10.1038/nm.3508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Zhang M, Hao W, Mihaljevic I, Liu X, Xie K, Walter S, Fassbender K. Matrix metalloproteinase-12 contributes to neuroinflammation in the aged brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyer RP, Patterson NL, Zouein FA, Ma Y, Dive V, de Castro Bras LE, Lindsey ML. Early matrix metalloproteinase-12 inhibition worsens post-myocardial infarction cardiac dysfunction by delaying inflammation resolution. Int J Cardiol. 2015;185:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JL, Devel L, Czarny B, George SJ, Jackson CL, Rogakos V, Beau F, Yiotakis A, Newby AC, Dive V. A selective matrix metalloproteinase-12 inhibitor retards atherosclerotic plaque development in apolipoprotein e-knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:528–535. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.110.219147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Razavian M, Bordenave T, Georgiadis D, Beau F, Zhang J, Golestani R, Toczek J, Jung JJ, Ye Y, Kim HY, et al. Optical imaging of mmp-12 active form in inflammation and aneurysm. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38345. Doi: 10.1038/srep38345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daugherty A, Manning MW, Cassis LA. Angiotensin ii promotes atherosclerotic lesions and aneurysms in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1605–1612. doi: 10.1172/jci7818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aryal B, Singh AK, Zhang X, Varela L, Rotllan N, Goedeke L, Chaube B, Camporez JP, Vatner DF, Horvath TL, et al. Absence of angptl4 in adipose tissue improves glucose tolerance and attenuates atherogenesis. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e97918. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.97918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu G, Su G, Davis JP, Schaheen B, Downs E, Roy RJ, Ailawadi G, Upchurch GR, Jr. A novel chronic advanced stage abdominal aortic aneurysm murine model. J Vasc Surg. 2017;66:232–242.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.07.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shipley JM, Wesselschmidt RL, Kobayashi DK, Ley TJ, Shapiro SD. Metalloelastase is required for macrophage-mediated proteolysis and matrix invasion in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3942–3946. Doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, Kitamura T, Zhang J, Campion LR, Kaiser EA, Snyder LA, Pollard JW. Ccl2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricard N, Scott RP, Booth CJ, Velazquez H, Cilfone NA, Baylon JL, Gulcher JR, Quaggin SE, Chittenden TW, Simons M. Endothelial erk1/2 signaling maintains integrity of the quiescent endothelium. J Exp Med. 2019;216:1874–1890. doi: 10.1084/jem.20182151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Goncalves R, Mosser DM. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2008;Chapter 14:Unit 14 11. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1401s83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gleason RL, Gray SP, Wilson E, Humphrey JD. A multiaxial computer-controlled organ culture and biomechanical device for mouse carotid arteries. J Biomech Eng. 2004;126:787–795. doi: 10.1115/1.1824130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferruzzi J, Bersi MR, Humphrey JD. Biomechanical phenotyping of central arteries in health and disease: advantages of and methods for murine models. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41:1311–1330. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0799-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawamura Y, Murtada SI, Gao F, Liu X, Tellides G, Humphrey JD. Adventitial remodeling protects against aortic rupture following late smooth muscle-specific disruption of tgfbeta signaling. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;116:104264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.104264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toczek J, Boodagh P, Sanzida N, Ghim M, Salarian M, Gona K, Kukreja G, Rajendran S, Wei L, Han J, et al. Computed tomography imaging of macrophage phagocytic activity in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Theranostics. 2021;11:5876–5888. doi: 10.7150/thno.55106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao RY, Amand T, Ford MD, Piomelli U, Funk CD. The murine angiotensin ii-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm model: rupture risk and inflammatory progression patterns. Front Pharmacol. 2010;1:9. Doi: 10.3389/fphar.2010.00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golledge J. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: update on pathogenesis and medical treatments. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16:225–242. Doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0114-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjorklund MM, Hollensen AK, Hagensen MK, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Christoffersen C, Mikkelsen JG, Bentzon JF. Induction of atherosclerosis in mice and hamsters without germline genetic engineering. Circ Res. 2014;114:1684–1689. Doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jana S, Hu M, Shen M, Kassiri Z. Extracellular matrix, regional heterogeneity of the aorta, and aortic aneurysm. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0286-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Bont CM, Boelens WC, Pruijn GJM. Netosis, complement, and coagulation: a triangular relationship. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16:19–27. doi: 10.1038/s41423-018-0024-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zelek WM, Morgan BP. Monoclonal antibodies capable of inhibiting complement downstream of c5 in multiple species. Front Immunol. 2020;11:612402. Doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.612402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilmore AC, Zhang Y, Cook HT, Lavin DP, Katti S, Wang Y, Johnson KK, Kim S, Pickering MC. Complement activity is regulated in c3 glomerulopathy by igg-factor h fusion proteins with and without properdin targeting domains. Kidney Int. 2021;99:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quintana RA, Taylor WR. Cellular mechanisms of aortic aneurysm formation. Circ Res. 2019;124:607–618. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.118.313187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spronck B, Latorre M, Wang M, Mehta S, Caulk AW, Ren P, Ramachandra AB, Murtada SI, Rojas A, He CS, et al. Excessive adventitial stress drives inflammation-mediated fibrosis in hypertensive aortic remodelling in mice. J R Soc Interface. 2021;18:20210336. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2021.0336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen M, Lee J, Basu R, Sakamuri SS, Wang X, Fan D, Kassiri Z. Divergent roles of matrix metalloproteinase 2 in pathogenesis of thoracic aortic aneurysm. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:888–898. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.114.305115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howatt DA, Dajee M, Xie X, Moorleghen J, Rateri DL, Balakrishnan A, Da Cunha V, Johns DG, Gutstein DE, Daugherty A, et al. Relaxin and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in angiotensin ii-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circ J. 2017;81:888–890. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-17-0229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longo GM, Xiong W, Greiner TC, Zhao Y, Fiotti N, Baxter BT. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 work in concert to produce aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:625–632. doi: 10.1172/jci0215334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deguchi JO, Huang H, Libby P, Aikawa E, Whittaker P, Sylvan J, Lee RT, Aikawa M. Genetically engineered resistance for mmp collagenases promotes abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in mice infused with angiotensin ii. Lab Invest. 2009;89:315–326. Doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosell A, Lo EH. Multiphasic roles for matrix metalloproteinases after stroke. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bellac CL, Dufour A, Krisinger MJ, Loonchanta A, Starr AE, Auf dem Keller U, Lange PF, Goebeler V, Kappelhoff R, Butler GS, et al. Macrophage matrix metalloproteinase-12 dampens inflammation and neutrophil influx in arthritis. Cell Rep. 2014;9:618–632. Doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dufour A, Bellac CL, Eckhard U, Solis N, Klein T, Kappelhoff R, Fortelny N, Jobin P, Rozmus J, Mark J, et al. C-terminal truncation of ifn-gamma inhibits proinflammatory macrophage responses and is deficient in autoimmune disease. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2416. Doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04717-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merle NS, Church SE, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Roumenina LT. Complement system part i - molecular mechanisms of activation and regulation. Front Immunol. 2015;6:262. Doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie CB, Jane-Wit D, Pober JS. Complement membrane attack complex: new roles, mechanisms of action, and therapeutic targets. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:1138–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin-Ventura JL, Martinez-Lopez D, Roldan-Montero R, Gomez-Guerrero C, Blanco-Colio LM. Role of complement system in pathological remodeling of the vascular wall. Mol Immunol. 2019;114:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou HF, Yan H, Stover CM, Fernandez TM, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Song WC, Wu X, Thompson RW, Schwaeble WJ, Atkinson JP, et al. Antibody directs properdin-dependent activation of the complement alternative pathway in a mouse model of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E415–E422. Doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119000109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:134–147. Doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan H, Zhou HF, Akk A, Hu Y, Springer LE, Ennis TL, Pham CTN. Neutrophil proteases promote experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm via extracellular trap release and plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1660–1669. Doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meher AK, Spinosa M, Davis JP, Pope N, Laubach VE, Su G, Serbulea V, Leitinger N, Ailawadi G, Upchurch GR, Jr. Novel role of il (interleukin)-1beta in neutrophil extracellular trap formation and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:843–853. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.117.309897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rateri DL, Davis FM, Balakrishnan A, Howatt DA, Moorleghen JJ, O’Connor WN, Charnigo R, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Angiotensin ii induces region-specific medial disruption during evolution of ascending aortic aneurysms. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:2586–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luo W, Wang Y, Zhang L, Ren P, Zhang C, Li Y, Azares AR, Zhang M, Guo J, Ghaghada KB, et al. Critical role of cytosolic DNA and its sensing adaptor sting in aortic degeneration, dissection, and rupture. Circulation. 2020;141:42–66. Doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emini Veseli B, Perrotta P, De Meyer GRA, Roth L, Van der Donckt C, Martinet W, De Meyer GRY. Animal models of atherosclerosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;816:3–13. Doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayek T, Oiknine J, Brook JG, Aviram M. Increased plasma and lipoprotein lipid peroxidation in apo e-deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:1567–1574. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hui DY, Basford JE. Distinct signaling mechanisms for apoe inhibition of cell migration and proliferation. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riddell DR, Graham A, Owen JS. Apolipoprotein e inhibits platelet aggregation through the l-arginine: nitric oxide pathway. Implications for vascular disease. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:89–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCubbrey AL, Allison KC, Lee-Sherick AB, Jakubzick CV, Janssen WJ. Promoter specificity and efficacy in conditional and inducible transgenic targeting of lung macrophages. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1618. Doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thul PJ, Akesson L, Wiking M, Mahdessian D, Geladaki A, Ait Blal H, Alm T, Asplund A, Bjork L, Breckels LM, et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science. 2017;356:eaal3321. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson A, Kampf C, Sjostedt E, Asplund A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. Doi: 10.1126/science.1260419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andersen HR, Maeng M, Thorwest M, Falk E. Remodeling rather than neointimal formation explains luminal narrowing after deep vessel wall injury: insights from a porcine coronary (re)stenosis model. Circulation. 1996;93:1716–1724. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.9.1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue biology perspective on macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:9–17. Doi: 10.1038/ni.3320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Watanabe S, Alexander M, Misharin AV, Budinger GRS. The role of macrophages in the resolution of inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:2619–2628. Doi: 10.1172/JCI124615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, Stacey D, Staley JR, Blackshaw J, Burgess S, Jiang T, Paige E, Surendran P, et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature. 2018;558:73–79. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0175-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Devel L, Rogakos V, David A, Makaritis A, Beau F, Cuniasse P, Yiotakis A, Dive V. Development of selective inhibitors and substrate of matrix metalloproteinase-12. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11152–11160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m600222200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Toczek J, Bordenave T, Gona K, Kim HY, Beau F, Georgiadis D, Correia I, Ye Y, Razavian M, Jung JJ, et al. Novel matrix metalloproteinase 12 selective radiotracers for vascular molecular imaging. J Med Chem. 2019;62:9743–9752. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.