Abstract

Background:

Dyadic stress theories and research suggest that couples’ negative communication patterns threaten immune and emotional health, leaving partners vulnerable to illness. Spouses’ relationship perceptions can also color how they see and react to marital discussions. To identify pathways linking distressed marriages to poor health, this study examined how self-reported typical communication patterns augmented discussion-based behavioral effects on spouses’ blister wound healing, emotions, and discussion evaluations.

Methods:

Married couples completed two 24-hour in-person visits where they had their blood drawn to measure baseline interleukin-6 (IL-6), received suction blister wounds, reported their typical communication patterns (demand/withdraw strategies, mutual discussion avoidance, mutual constructive communication), and engaged in marital discussions. Discussions were recorded and coded for positive and negative behaviors using the Rapid Marital Interaction Coding System (RMICS). Immediately after the discussions, spouses rated their emotions and evaluated the discussion tone and outcome. Wound healing was measured for 12 days.

Results:

Couples who reported typically using more demand/withdraw or mutual avoidance patterns had higher baseline IL-6, slower wound healing, greater negative emotion, lower positive emotion, and poorer discussion evaluations. In contrast, couples reporting more mutual constructive patterns reported more favorable discussion evaluations. Additionally, couples’ more negative and less positive patterns exacerbated behavioral effects: Spouses’ wounds healed more slowly, reported lower positive emotion, and evaluated the discussions less positively if their typical patterns and discussion-based behaviors were more negative and less positive.

Conclusions:

Couples’ typical communication patterns—including how often they use demand/withdraw, mutual avoidance, and mutual constructive patterns—may color spouses’ reactions to marital discussions, amplifying the biological, emotional, and relational impact. These findings help explain how distressed marriages take a toll on spouses’ health.

Keywords: Stress, romantic relationships, conflict, wound healing, inflammation

Introduction

Couples’ relationships have substantial health effects. Indeed, married spouses’ morbidity and mortality are reliability lower than those who are unmarried (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2017; Robles et al., 2014). Yet, marriage itself is not necessarily protective: Distressed spouses are often no better off or fare worse than those who are not married (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008; Shrout et al., 2021). Distressed marriages—characterized by chronic negativity—pose significant relationship and health risks. Dyadic stress theories and research highlight how couples’ negative communication patterns carry immune consequences (Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017; Shrout, 2021). These immune risks leave partners vulnerable to both acute and chronic illness (Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017).

Notably, laboratory studies have shown that couples’ using hostile behaviors during marital discussions had slower wound healing and heightened proinflammatory cytokine production relative to their less hostile peers (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005). In addition, spouses’ self-reported negative communication patterns have been associated with greater negative emotions and lower conflict resolution (Papp et al., 2009). Though related, research has shown that couples’ self-reported communication patterns are distinct from the specific behaviors they use during discussions (Caughlin & Huston, 2002; Papp et al., 2009); this finding has encouraged researchers to measure typical self-reported patterns and discussion-based behaviors as separate constructs. Likewise, partners see specific marital events through their more global relationship perceptions (Bradbury & Fincham, 1990; Karney, 2015). Couples’ typical patterns may therefore color how partners see and react to specific marital discussions. Assessing both self-reported patterns and discussion-based behaviors may provide unique perspectives that interact to predict marriage’s health impact. In a sample of married couples who received blister wounds and engaged in marital discussions, the current study extends prior work by addressing how typical self-reported communication patterns augment the effects of discussion-based behaviors on spouses’ wound healing, emotions, and discussion evaluations.

Self-Reported Typical Communication Patterns and Health

Many couples report using demand/withdraw communication, a common yet destructive pattern (Baucom et al., 2011). This pattern occurs when one partner criticizes, nags, or makes demands to change, discuss, or resolve an issue. In turn, the other partner responds by avoiding the discussion, becoming defensive, or withdawing during the discussion (Eldridge & Christensen, 2002). Compared to less demanding and withdrawing couples, those reporting more frequent demand/withdraw patterns experienced heightened cortisol reactivity to marital discussions (Heffner et al., 2006). Some work has shown that wives and husbands reported both demanding and withdrawing at similar rates (Papp et al., 2009); in contrast, others have found that couples report wife demand/husband withdraw patterns more often than husband demand/wife withdraw patterns (Christensen et al., 2006; Eldridge & Christensen, 2002). In addition, although husband demand/wife withdraw patterns were not associated with spouses’ physiological responses to marital discussions, cortisol and norepinephrine levels were higher in couples using more wife demand/husband withdraw patterns (Heffner et al., 2006; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1996). These findings illustrate not only the adverse relational and health effects of self-reported demand/withdraw patterns but also the importance of the examining each spouse’s role.

Couples’ also report mutual avoidance and mutual constructive patterns in their typical communication. As with demand/withdraw strategies, mutual avoidance is a relationship-compromising communication pattern associated with increased relationship and health risks. For example, when reporting mutual avoidance patterns, spouses had greater distress and lower intimacy. Conversely, when reporting mutual constructive communication—a relationship-enhancing pattern—each spouse reported lower distress, higher intimacy, and greater satisfaction (Manne et al., 2010; Manne et al., 2006). Moreover, compared to their less constructive peers, couples using more constructive patterns during conflict had smaller interleukin-6 (IL-6) increases over 24 hours (Graham et al., 2009).

Coded Discussion Behaviors and Health

In addition to typical communication patterns, couples’ discussion-based behaviors are associated with adverse immune and relational changes. As shown in laboratory studies, couples’ negative behaviors during conflict or social support discussions were linked not only to higher IL-6 the next morning but also slower wound healing two weeks later (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005). In contrast, couples’ positive behaviors have been related to faster wound healing and lower cortisol responses to marital discussions (Gouin et al., 2010; Shrout et al., 2020). As for couples’ emotional and relational well-being, spouses felt more negatively and less close when using more negative and fewer positive behaviors during conflict (Wilson et al., 2018). Couples’ behaviors also have lasting relational effects: Compared to their less negative peers, couples using negative behaviors during lab discussions were more dissatisfied 10 years later (Kiecolt-Glaser, Bane, et al., 2003).

Gendered Effects in the Marriage—Health Link

Importantly, marital stress takes a stronger toll on women than men (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Wanic & Kulik, 2011). The interpersonal orientation hypothesis highlights how women’s identities are more interdependent and relationship focused (Cross & Madson, 1997; Orbuch et al., 2013). In contrast, men’s self-perceptions are more independent and less relationship oriented. Often due to gendered socialization and power inequalities, women monitor and think about their relationships more than men; women also carry more of the burden of resolving marital conflict (Silverstein et al., 2006). Couples’ frequent use of negative communication and behavioral patterns may signal to women that their relationships are in trouble. Women may therefore experience greater adverse responses to these negative patterns and behaviors.

The Current Study

To understand the immune, emotional, and relational effects of self-reported and behavioral communication, we examined how both typical self-reported patterns and discussion-based behaviors predicted post-discussion blister wound healing, emotions, and evaluations; we also addressed how typical self-reported patterns predicted baseline IL-6 levels. Couples completed two in-person visits where they reported their typical communication patterns and engaged in marital discussions. Prior to the discussions, spouses’ baseline IL-6 was assessed, and they received suction blister wounds on their forearms. Immediately after the discussions, spouses rated their emotions and evaluated the discussion.

We hypothesized that spouses’ greater use of more self-reported negative communication patterns (demand/withdraw strategies, mutual discussion avoidance) would be associated with higher baseline IL-6 levels, slower wound healing, and more negative post-discussion emotions and evaluations; in contrast, greater self-reported positive communication patterns (mutual constructive communication) would be linked to lower baseline IL-6, faster wound healing, and more positive post-discussion emotions and evaluations. In addition, building on the parent study’s finding that hostile discussion behaviors disrupted wound healing (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005), we expected that couples’ typical communication patterns would influence how spouses viewed and responded to the marital discussions. Thus, we hypothesized that self-reported negative patterns would exacerbate behavioral effects on post-discussion wound healing, emotions, and evaluations. In contrast, we expected that self-reported positive patterns would lessen behavioral effects on these outcomes. Last, given the stronger impact of marital stress on women, we hypothesized that these effects would be stronger for women relative to men (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Shrout et al., 2019).

Methods

Participants

Married couples (n=42 couples, 84 participants) were recruited for a parent study on marital stress and wound healing (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005). Couples were recruited through community, campus, newspaper, and radio ads. Exclusion criteria included health problems and medications that involved immunological or endocrinological dysfunction, or otherwise had consequences for wound healing (e.g., cancer, recent surgeries, strokes, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, conditions such as asthma or arthritis that required regular use of anti-inflammatories). Couples were excluded if either spouse took blood pressure medication, smoked, or used excessive alcohol or caffeine, or if they were married fewer than 2 years. A total of 224 couples were excluded because at least one spouse did not meet the stringent health criteria. Participants’ average age was 37 years (SD=13, range=22-77), and most participants were white (88%). All couples were married with an average duration of 12.2 years (SD=10.8, range=2-52). Most participants were college educated (67%) and employed (85%).

Procedure

Participants completed two 24-hr admissions to the Clinical Research Center (CRC), a hospital research unit, about two months apart. The procedures and timetable were similar across these two admissions. Participants remained with their spouse in the same room for the entire 24-hr visit to assure consistent physical activity across couples and admissions. We asked couples not to drink or eat after midnight before the admissions; all couples were served the same meals, controlling for dietary factors. At both visits, couples were admitted to the CRC at 7 a.m., had a baseline blood draw for inflammation, ate a standard breakfast, and completed questionnaires, which included a general communication pattern measure (see below).

At 9:15 a.m., nurses performed the suction blistering procedure where blister wounds were raised on each partner’s forearm (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005). The suction blister protocol followed the methods described previously and used the same suction blister device (NeuroProbe, Cabin John, MD) (Glaser et al., 1999). A plastic template was taped to the volar surface of the nondominant forearm; a 350-mmHg vacuum was applied through a pump attached to a regulator until blisters formed (1-1.5 hours). This gentle suction produced eight small eight-millimeter blisters. Couples then completed one of two 20-minute discussions: a social support discussion during the first CRC admission, and a conflict discussion during the second CRC admission. The research team remained out of sight while videotaping the discussions.

During the social support discussion at visit 1, each partner either solicited or offered social support (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005; Pasch & Bradbury, 1998). Prior to these social support discussions, both partners identified an important personal characteristic, problem, or issue they wished to change; the issue could not be a source of marital dissension. The other partner was instructed to be involved and respond as they normality would as if they were at home. Partner order was randomized, and they reversed roles after 10 minutes.

During the marital problem discussion at visit 2, couples tried to resolve one or more of their marital issues. To initiate the discussions, an experimenter first conducted a 10- to 20-minute interview to identify the most contentious topics within the marriage for both spouses (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). These topics were selected from an inventory each spouse completed about their relationship problems. Couples were then asked to discuss and try to resolve one or more marital issues that the experimenter judged to be the most conflict-producing (e.g., money, communication, or in-laws).

Each partner then completed post-discussion measures. Fluid was removed from blister chambers 4, 7, and 22 hours after raising the blisters; participants were discharged after removal of the blister chamber at 7 a.m. Following each CRC visit, participants’ blister wound healing was measured daily for eight days and then again on day 12. Study procedures were approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board; participants provided written informed consent before participating.

Measures and Materials

Baseline inflammation.

Plasma IL-6 levels were assayed using Quantikine High Sensitivity Immunoassay kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), per kit instructions, as described elsewhere (Kiecolt-Glaser, Preacher, et al., 2003). Samples were run undiluted in duplicate, and all samples for a couple were run at the same time. IL-6 measurements were log transformed prior to analyses to better approximate normality of residuals.

Typical communication patterns.

The Communication Patterns Questionnaire – Short Form (CPQ-SF) assessed spouses’ perceptions of their typical communication patterns when an issue or problem arises and during discussions (Christensen & Heavey, 1990); spouses completed the CPQ-SF at the first visit. The CPQ-SF assesses six subscales: (1) mutual constructive communication, or symmetrical positive communication, (2) mutual problem discussion avoidance, (3) husband demand/wife withdraw communication, (4) wife demand/husband withdraw communication, (5) roles in demand/withdraw communication, and (6) total demand/withdraw communication. Responses for each item ranged from 1 (very unlikely) to 9 (very likely). Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .64 to .78 in the current study, consistent with previous research demonstrating acceptable reliability and validity of the CPQ-SF (Heavey et al., 1993).

Behavioral coding.

Couples’ behavior during both discussions were coded using the Rapid Marital Interaction Coding System (RMICS) which discriminates well between distressed and nondistressed couples (Heyman, 2004). RMICS is designed to code dyadic behavior and interaction patterns, and thus both partners’ behaviors are coded simultaneously to create individual- and couple-level ratings. Consistent with prior research (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2015, 2018; Shrout et al., 2020), this study focused on couple-level ratings and how couples’ behaviors related to each partner’s outcomes.

Distressed marriages are characterized by negative affect, conflictual communication, and poor listening skills. Consistent with past approaches (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005) and to capture these dimensions in composite indexes, we used an index summarizing negative behaviors across three categories: psychological abuse (e.g., disgust, contempt, belligerence, as well as nonverbal behaviors like glowering or talking in a threatening or menacing manner), distress-maintaining attributions(e.g., “You’re only being nice so I’ll have sex with you tonight” or “You were being mean on purpose”), and hostility (e.g., criticism, hostile voice tone, or rolling the eyes dramatically). Interrater reliability was acceptable (κ= 0.63).

As with previous research (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005), we used an index summarizing positive behaviors across three categories: acceptance (e.g., verbal and nonverbal attempts at active listening and expressing concern, “I could imagine that you would be sad now”); relationship-enhancing attributions (e.g., negative behaviors explained by circumstances or to involuntary or unintentional causes, “You’re short with me because you’ve had a hard day”); and constructive problem discussion (e.g., constructive approaches to discussing or solving problems, “Let’s stop eating out so often” or “I think you’re right about that”). Interrater reliability was acceptable (κ= 0.80).

Post-discussion evaluation.

After the discussions, participants rated several items assessing their evaluation of the discussion. Using a scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree), participants rated six items regarding their satisfaction with the discussion, emotional tone of the discussion, partner support during the discussion, partner understanding during the discussion, feelings of control, and feelings of working productively during the discussion. The items were averaged with higher scores reflecting more positive discussion evaluations (αs=0.90-0.92).

Post-discussion emotion.

Positive and negative emotion after the discussions were assessed using the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS, Watson et al., 1988). Separate subscales are computed to assess both positive and negative emotions.

Blister wound healing.

Blister wound healing was assessed according to established protocols (Glaser et al., 1999; Gouin & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2011). Measurement of the rate of transepidermal water loss (TEWL) through human skin provided a noninvasive method to monitor changes in the stratum corneum barrier function of the skin, providing an excellent objective method for evaluation of wound healing. A computerized evaporimetry instrument, the DermaLab (CyberDERM, Media, PA), measured vapor pressure gradient in the air layers close to the skin surface, following established procedural guidelines. The 8 blister sites were assessed daily for 8 days and then again on day 12 in our lab by well-trained lab personnel; participants scheduled their ideal time initially, and then used that schedule across the 8 days and then again on day 12. Raw TEWL values were adjusted for daily variations in temperature and humidity. Daily control values from adjacent nonwounded skin were collected to provide information on normal fluctuations in TEWL. Daily control values were subtracted from the temperature adjusted TEWL value. Healing was defined as the standard criterion of reaching 90% of the day 1 pre-blistering TEWL temperature- and control-adjusted baseline value. After subtracting the average control values from the average daily measurement, AUC was calculated across all points to provide an overall measure of healing (Hirsch et al., 2008) that maximized available data. Those who healed faster would return to baseline more quickly and, therefore, have lower AUC values compared to those who healed more slowly.

Covariates.

Primary analyses controlled for age and gender, and models predicting wound healing and IL-6 controlled for body mass index (BMI).

Analytical Plan

Preliminary analyses examined correlations, means, and standard deviations of study variables. Dyadic multilevel modeling (MLM) was used to test the study hypotheses (MLM; Kenny et al., 2006). This analytical approach allowed for explicit modeling of the non-independence in married couples’ data. To account for the two visits, we specified that individuals were nested within couples and that visit was a repeated factor across couples (i.e., that we had observations for both partners on each sample time; Kenny et al., 2006). We accounted for the similarity in the spouses’ average outcomes by including a random intercept using a variance components covariance structure. We also accounted for the similarity in the residuals of the spouses’ outcomes across the specific time points using an unstructured covariance matrix. An additional strength of using MLM is that it accounts for missing data by maximizing the use of existing data. MLM analyses were performed using the MIXED MODELS procedure with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. Before the primary analyses, the independent variables (communication patterns, discussion behaviors) and continuous covariates (age, BMI) were grand mean-centered to improve the interpretability of the intercepts. Dichotomous variables were effects coded (gender: men=−1, women=1, visit: visit 1=−1, visit 2=1).

First, we tested hypotheses that spouses who reported greater negative communication patterns and fewer positive communication patterns would have higher baseline IL-6 levels, greater post-discussion negative emotion, lower post-discussion positive emotion, less positive discussion evaluations, and slower bister wound healing. Separate models were used to test the six communication patterns (total demand/withdraw, husband demand/wife withdraw, wife withdraw/husband demand, relative role in demand/withdraw, mutual discussion avoidance, and mutual constructive communication). We also included both positive and negative coded discussion behaviors in the models to account for and test their effects on the post-discussion outcomes (i.e., all outcomes except baseline IL-6).

Then, to test hypotheses that self-reported communication patterns and coded positive/negative behaviors would interact to predict the post-discussion outcomes, we added two-way interactions between each communication pattern and positive/negative behavior.

Last, to address hypotheses that self-reported communication patterns and coded positive/negative behaviors would be stronger for women than men, we added two- and three-way interactions between gender, the communication patterns, and coded behaviors. Nonsignificant interactions were removed in constructing the final models and when probing significant lower-order interactions. We used the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate method to account for multiple comparisons (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995); this method controls the error rate of false positives by considering the number of significant results in a family of tests. As discussed by McDonald (2014), a false discovery rate of 0.05 is likely too low for the Benjamini–Hochberg correction, and a rate of 0.10-0.20 is suggested. All associations reported below held after FDR adjustments and fell below an FDR of .15. Tests also held after a more stringent .10 FDR correction, unless otherwise noted in the text and tables. Continuous interactions were computed as the product of the mean-centered variables (Aiken & West, 1991). Significant interacting effects were probed at one standard deviation above and below the means for each continuous interacting variable. Models corrected for multiple comparisons, and all analyses were done using SPSS version 26.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 for correlations among study variables. Correlations showed significant relations among self-reported and coded discussion-based behavior. Coded negative behaviors were correlated with greater self-reported total demand/withdraw and wife demand/husband withdraw patterns (ps<0.01), as well as lower self-reported mutual constructive communication (p=0.03). Coded discussion-based positive behaviors were related to lower self-reported husband demand/wife withdraw (p=0.04). Coded negative and positive behavior were not correlated (p=0.50). There were significant positive correlations among the self-reported negative communication patterns, which included total demand/withdraw, husband demand/wife withdraw, wife demand/husband withdraw, and roles in demand/withdraw (ps<0.01). Mutual constructive communication was negatively correlated with each negative self-reported pattern (ps<0.01) except husband demand/wife withdraw (p=0.41).

Table 1.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| Total D/W | Husband demand/wife withdraw | Wife demand/husband withdraw | Roles in D/W | MDA | MCC | Coded positive behavior | Coded negative behavior | Base. IL-6 | Wound healing (TEWL AUC) | NE | PE | DE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total demand/withdraw (D/W) | - | ||||||||||||

| Husband demand/wife withdraw | 0.73*** | - | |||||||||||

| Wife demand/husband withdraw | 0.83*** | 0.22*** | - | ||||||||||

| Roles in demand/withdraw | 0.19*** | −0.53*** | 0.71*** | - | |||||||||

| Mutual discussion avoidance (MDA) | 0.30*** | 0.16** | 0.29*** | 0.14** | - | ||||||||

| Mutual constructive communication (MCC) | −0.35*** | −0.04 | −0.47** | −0.38*** | −0.34*** | - | |||||||

| Coded positive behavior | −0.11 | −0.13* | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.05 | - | ||||||

| Coded negative behavior | 0.17** | 0.10 | 0.16** | 0.07 | −0.03 | −0.13* | 0.04 | - | |||||

| Baseline IL-6 | 0.17* | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.08 | −0.23** | 0.15* | - | ||||

| Wound healing (TEWL AUC) | −0.13 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.02 | 0.19** | −0.08 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | - | |||

| Negative emotion (NE) | 0.19** | 0.13* | 0.17** | 0.06 | 0.09 | −0.16** | −0.02 | 0.21** | −0.01 | −0.004 | - | ||

| Positive emotion (PE) | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.12 | 0.07 | 0.21** | −0.20** | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.09 | - | |

| Discussion evaluation (DE) | −0.28*** | −0.15* | −0.28*** | −0.13* | −0.05 | 0.29*** | 0.13* | −0.50*** | −0.17* | 0.000 | −0.39*** | 0.32*** | - |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

For outcomes, baseline IL-6 was correlated with greater self-reported total demand/withdraw patterns (p=0.02), greater discussion-based negative behavior (p=0.05), and lower discussion-based positive behavior (p=0.002). Slower wound healing was correlated with greater self-reported mutual avoidance (p=0.007). Greater negative emotion was related to lower self-reported mutual constructive communication, as well as greater self-reported total demand/withdraw, husband demand/wife withdraw, wife demand/husband withdraw, and discussion-based negative behavior (ps<0.01). Higher positive emotion was related to lower self-reported mutual avoidance (p=0.049) and lower discussion-based negative behavior (p<0.001). More favorable discussion evaluations were correlated with lower self-reported total demand/withdraw, husband demand/wife withdraw, wife demand/husband and roles in demand/withdraw patterns (ps<0.01); more constructive communication patterns (p<0.001); and more positive (p=0.04) and less negative (p<0.001) discussion-coded behaviors. For study outcomes, higher baseline IL-6 was correlated with more negative discussion evaluations (p=0.03). More negative discussion evaluations were also correlated with lower negative emotion and greater positive emotion after the discussions (ps<0.001).

Typical Communication Patterns and Baseline Inflammation

Table 2 shows significant effects for each communication pattern and coded behavior across outcomes; Table 3 shows significant interactions between communication patterns, behavior, and gender across outcomes.

Table 2.

Multilevel Model Coefficients for Significant Communication Patterns and Coded Behaviors Across Immune, Emotional, and Relational Outcomes

| Outcome | b (SE) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline IL-6 | ||

| Total demand/withdraw | 0.003 (0.001) | 0.04a |

| Husband demand/wife withdraw | 0.01 (0.003) | 0.01 |

| Post-Discussion Negative Emotion | ||

| Total demand/withdraw | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.001 |

| Wife demand/husband withdraw | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.019 |

| Coded negative behavior | 0.08 to 0.09 (0.02) | <0.002 |

| Post-Discussion Positive Emotion | ||

| Mutual discussion avoidance | −0.68 (0.27) | 0.01 |

| Post-Discussion Evaluation | ||

| Total demand/withdraw | −0.03 (0.01) | 0.003 |

| Wife demand/husband withdraw | −0.04 (0.01) | <0.001 |

| Roles in demand/withdraw | −0.03 (0.01) | 0.016 |

| Mutual constructive communication | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.003 |

| Coded negative behavior | −0.06 to −0.07 (0.01) | <0.001 |

| Wound healing (TEWL AUC) | ||

| Mutual discussion avoidance | 4.12 (1.96) | 0.037a |

Notes. Only significant effects are shown; all effects are reported in text. Negative behavior coefficent ranges reflect effects across models with each self-reported communication pattern.

This effect remained significant after a Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate correction of .15 but not .10.

Table 3.

Multilevel Model Coefficients for Significant Interactions Between Communication Patterns, Coded Behaviors, and Gender Across Immune, Emotional, and Relational Outcomes

| Outcome | b (SE) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline IL-6 | ||

| Husband demand/wife withdraw*Gender | 0.01 (0.002) | <0.001 |

| Roles in demand/withdraw*Gender | −0.005 (0.002) | 0.004 |

| Post-Discussion Negative Emotion | ||

| Negative behavior*Gender | 0.04 to 0.05 (0.02) | <0.008 |

| Post-Discussion Positive Emotion | ||

| Mutual discussion avoidance*Gender | −0.56 (0.27) | 0.037a |

| Mutual constructive communication*Negative behavior*Gender | −0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 |

| Husband demand/wife withdraw*Positive behavior*Gender | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.045a |

| Post-Discussion Evaluation | ||

| Husband demand/wife withdraw*Negative behavior | 0.003 (0.001) | 0.047a |

| Wound healing (TEWL AUC) | ||

| Mutual discussion avoidance*Positive behavior | 0.35 (0.11) | 0.002 |

Note. Only significant interactions are shown; all interaction effects are reported in text. Negative behavior coefficent ranges reflect effects across models with each self-reported communication pattern.

This effect remained significant after a Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate correction of .15 but not .10.

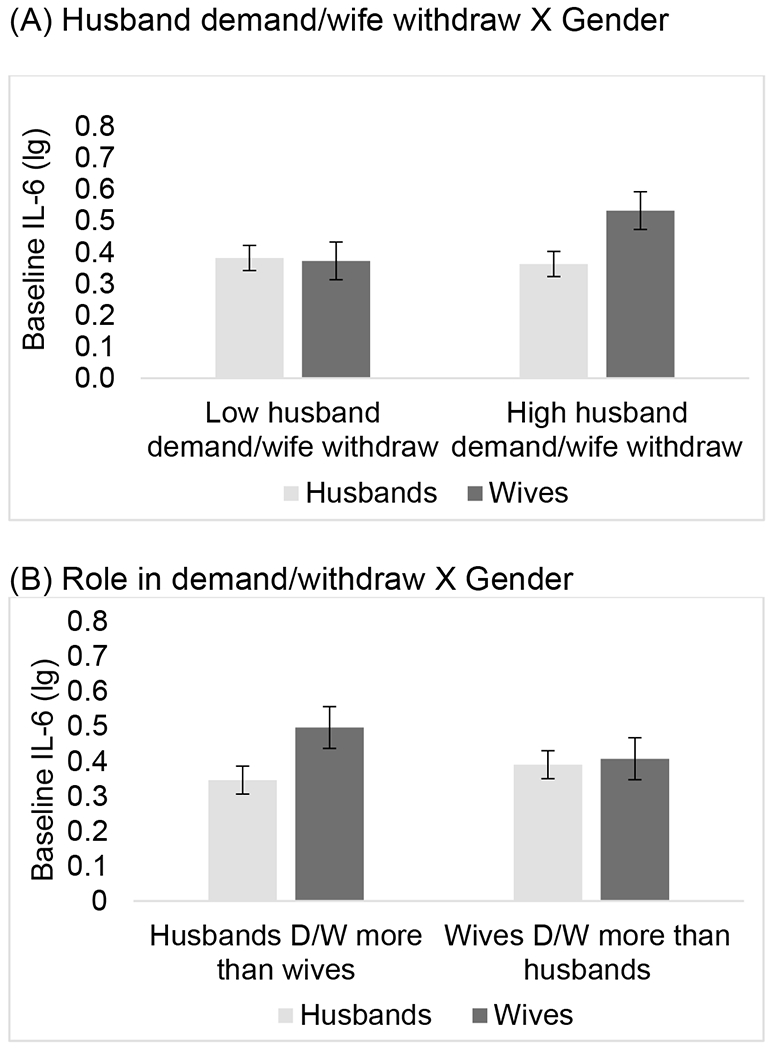

For inflammation, spouses who reported greater demand/withdraw and husband demand/wife withdraw communication also had higher baseline IL-6 levels; this effect survived an FDR of .15 but not .10. In addition, the effects of husband demand/wife withdraw and the relative use of demand/withdraw patterns differed by gender. As shown in Figure 1, wives, but not husbands, had higher baseline IL-6 if they reported greater husband demand/wife withdraw patterns (Figure 1A; wives: b=0.02, SE=0.004, p<0.001; husbands: b=−0.002, SE=0.003, p=0.56) and if they reported husbands demand/withdraw more than wives (Figure 1B; wives: b=−0.006, SE=0.003, p=0.02; husbands: b=0.003, SE=0.002, p=0.13). Husbands and wives had similar baseline IL-6 levels at lower husband demand/wife withdraw communication patterns (b=−0.005, SE=0.02, p=0.77) and when wives used more demand/withdraw communication than husbands (b=0.01, SE=0.01, p=0.55). However, wives’ IL-6 was higher than husbands’ at high levels of husband demand/wife withdraw communication (b=−0.08, SE=0.02, p<0.001) and if husbands demand and withdraw more than wives do (b=0.08, SE=0.02, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Visual depictions of interactions predicting interleukin-6 (IL-6). Wives, but not husbands, had higher baseline IL-6 if they reported higher husband demand/wife withdraw patterns (Figure 1A; wives p<0.001; husbands p=0.56) and if they reported husbands demand/withdraw more than wives (Figure 1B; wives p=0.02; husbands p=0.13). Wives’ IL-6 was higher than husbands’ at high levels of husband demand/wife withdraw communication (p<0.001) and if husbands demand and withdraw more than wives (p<0.001). Error bars are ±1 standard error.

Mutual constructive communication (p=0.97), wife demand/husband withdraw communication (p=0.55), and mutual discussion avoidance (p=0.73), and their interactions with gender (ps>0.20), were not related to IL-6. Covariates showed IL-6 was higher in spouses who were older (ps<0.05), had greater BMIs (ps<0.03), and were women (ps<0.001).

Typical Communication Patterns, Coded Laboratory Discussion Behaviors, and Post-Discussion Negative Emotion

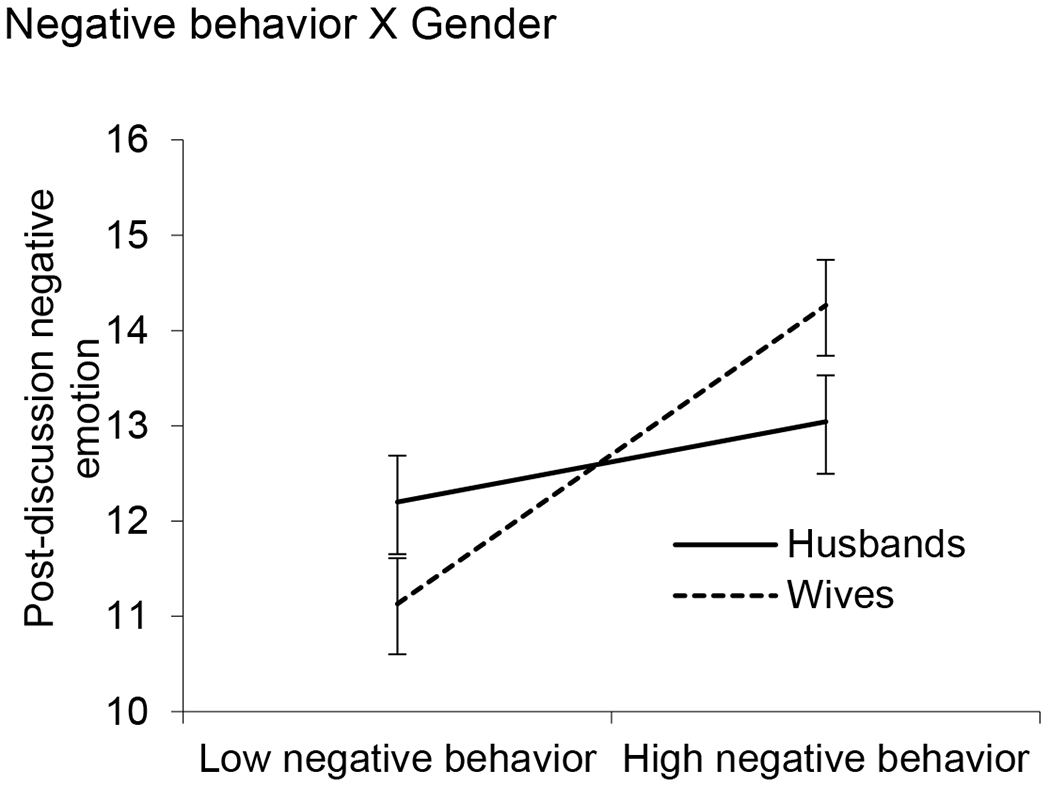

Spouses’ negative emotion was higher in those reporting more frequent total demand/withdraw and wife demand/husband withdraw patterns, as well as in those who used more negative behaviors during the discussions. Additionally, as shown in Figure 2, interactions with gender showed couples’ negative behaviors predicted greater negative emotion after the discussion for women but not men (women: b=0.13, SE=0.03, p<0.001; men: b=0.03, SE=0.03, p=0.26). Husbands’ and wives’ negative emotion was similar in couples using fewer negative behaviors during lab discussions (b=−0.53, SE=0.29, p=0.07), but wives’ negative emotion was greater than husbands’ in couples using more negative behaviors (b=0.61, SE=0.30, p=0.04).

Figure 2.

Visual depiction of interactions predicting post-discussion negative emotion. Wives (p<0.001) but not husbands (p=0.26) had greater negative emotion after the discussions if couples used more negative behaviors compared to fewer negative behaviors. Wves’ negative emotion was also greater than husbands’ in couples using more negative behaviors (p=0.04). Error bars are ±1 standard error.

Self-reported mutual constructive communication (p=0.07), mutual discussion avoidance (p=0.07), husband demand/wife withdraw patterns (p=0.09), and the role in demand/withdraw communication (p=0.40) did not predict post-discussion negative emotion; their interactions with coded positive behavior (ps>0.05), negative behavior (ps>0.85), and gender (ps>0.30) were not significant. Covariates showed post-discussion negative emotion was higher in spouses who were older (ps<0.05).

Typical Communication Patterns, Coded Laboratory Discussion Behaviors, and Post-Discussion Positive Emotion

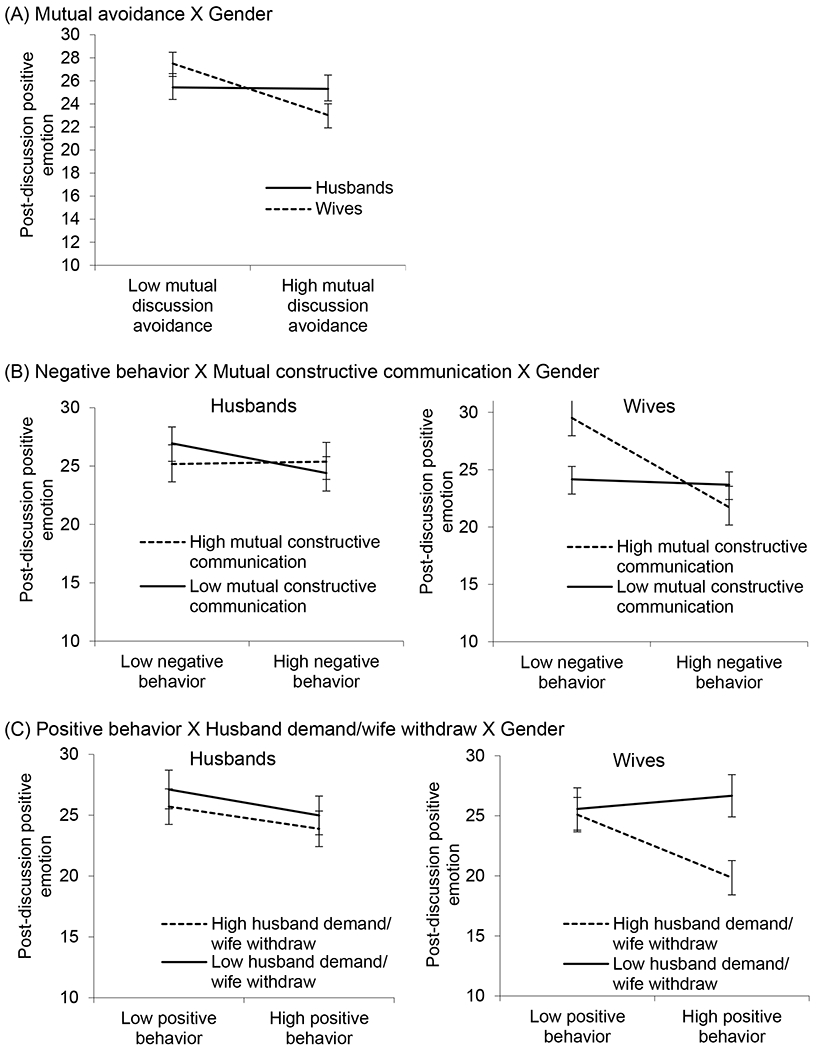

Spouses’ post-discussion positive emotion was lower if they reported greater mutual discussion avoidance. As shown in Figure 3A, a two-way gender interaction revealed wives, but not husbands, had lower positive emotion after the lab discussions if they reported greater mutual discussion avoidance (women: b=−1.16, SE=0.35, p=0.001; b=−0.03, SE=0.41, p=0.94); this effect survived an FDR of .15 but not .10. Interactions between mutual discussion avoidance and positive or negative behavior were not significant (ps>0.40).

Figure 3.

Visual depictions of interactions predicting post-discussion positive emotion. Error bars are ±1 standard error. Figure 3A: Wives (p=0.001), but not husbands (p=0.94), had lower positive emotion after the lab discussions if they reported greater mutual discussion avoidance. Figure 3B: Wives, but not husbands, had higher positive emotion after the lab discussions if they reported greater mutual constructive communication and used fewer negative discussion behaviors compared to more negative behaviors (p=0.003) or less mutual constructive communication (p=0.005). Figure 3C: Wives’, but not husbands’, positive emotion was lower in those reporting greater husband demand/wife withdraw patterns and using more positive discussion behaviors during lab discussions compared to less frequent husband demand/wife withdraw patterns (p=0.003) or fewer positive discussion behaviors (p=0.001).

As shown in Figure 3B, a three-way interaction between mutual constructive communication, gender, and negative behavior revealed wives, but not husbands, had higher positive emotion after the lab discussions if they reported greater mutual constructive communication and used fewer negative discussion behaviors. Thus, wives who reported greater mutual constructive communication had higher positive emotion if they also used fewer negative behaviors relative to more negative behaviors (b=−0.31, SE=0.10, p=0.003). Likewise, wives who used fewer negative behaviors had higher positive emotion if they also reported more mutual constructive communication relative to less mutual constructive communication (b=0.51, SE=0.18, p=0.005). Wives who reported low mutual constructive communication had lower positive emotion regardless of couples’ negative behaviors during lab discussions (b=−0.01, SE=0.06, p=0.73). Husbands’ positive emotion was similar regardless of their mutual constructive communication and negative behaviors (ps>0.12).

As shown in Figure 3C, a three-way interaction between husband demand/wife withdraw communication, gender, and positive behavior showed wives’, but not husbands’, positive emotion was lowest in those reporting greater husband demand/wife withdraw patterns and using more positive discussion behaviors during lab discussions. In couples using more positive behaviors, wives who reported lower husband demand/wife withdraw patterns felt more positive than those reporting greater husband demand/wife withdraw patterns (b=−0.70, SE=0.23, p=0.003). Among wives who reported greater husband demand/wife withdraw patterns, wives’ felt less positive when couples used more positive behaviors relative to less positive behaviors (b=−0.23, SE=0.07, p=0.001). Wives who reported lower husband demand/wife withdraw patterns had similar positive emotion regardless of couples’ negative behaviors (b=0.02, SE=0.06, p=0.78). This three-way interaction effect held after an FDR of .15 but not a more stringent FDR of .10. Husbands’ positive emotion was similar regardless of their demand/wife withdraw communication patterns and positive behaviors (ps>0.16).

Total demand/withdraw communication (p=0.63), wife demand/husband withdraw patterns (p=0.63), and the role in demand/withdraw communication (p=0.14) did not predict post-discussion positive emotion; their interactions with positive behavior (ps>0.27), negative behavior (ps>0.25), and gender (ps>0.29) also were not significant. Covariates showed post-discussion positive emotion was higher in spouses who were older (ps<0.05) and lower at visit 2 (ps<0.05).

Typical Communication Patterns, Coded Laboratory Discussion Behaviors, and Post-Discussion Evaluations

Spouses’ discussion evaluations were more positive in those reporting less frequent demand/withdraw, wife demand/husband withdraw, and men demanding and withdrawing more than women patterns, as well as greater mutual constructive communication. Additionally, their evaluations were more positive in couples using fewer negative behaviors during the lab discussions.

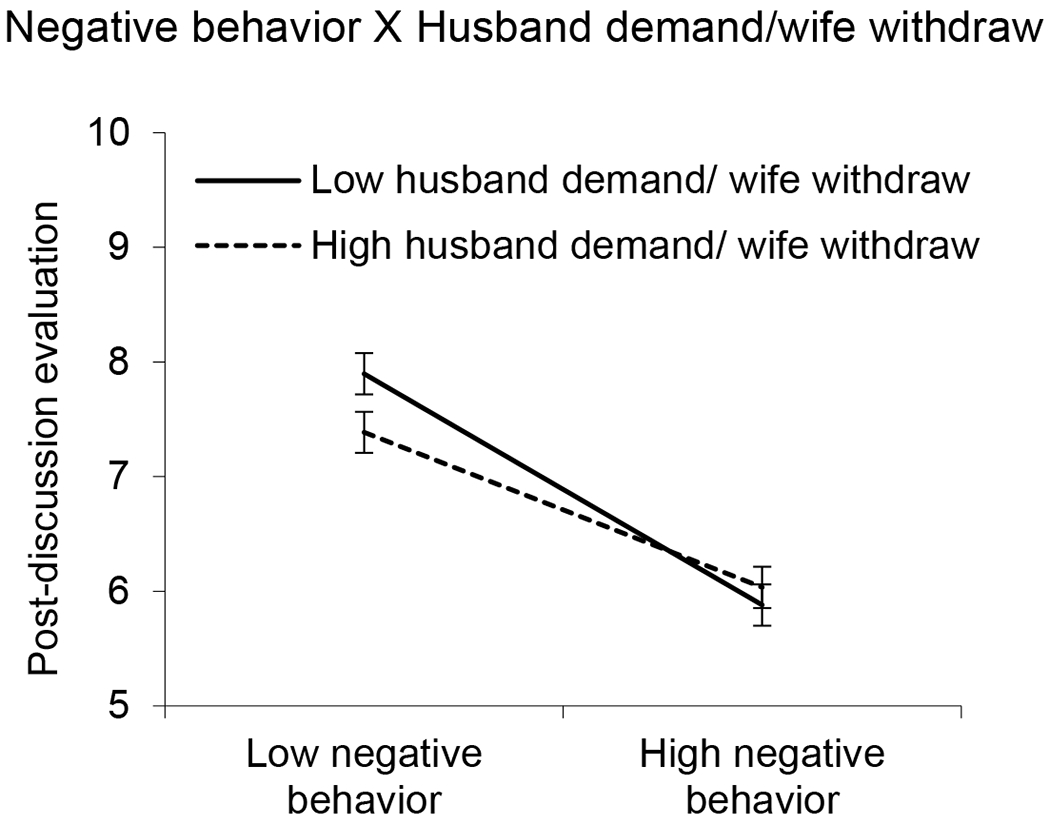

As shown in Figure 4, the two-way interaction between husband demand/wife withdraw patterns and negative behavior showed spouses rated the discussions the most positive if they reported low husband demand/wife withdraw patterns and also used fewer negative behaviors during discussions; evaluations were least positive in those using husband demand/wife withdraw patterns and more frequent negative behavior. Specifically, simple slopes showed spouses’ evaluations were more positive in couples who used fewer negative discussion behaviors and also reported lower husband demand/wife withdraw relative to higher husband demand/wife withdraw patterns (b=−0.05, SE=0.02, p=0.03). Spouses’ evaluations were less positive if they used more negative discussion behaviors at both high (b=−0.05, SE=0.01, p<0.001) and low (b=−0.08, SE=0.01, p<0.001) levels of husband demand/wife withdraw patterns. This two-way interaction effect held after an FDR of .15 but not .10.

Figure 4.

Visual depictions of interactions predicting post-discussion evaluation (higher scores indicate more positive evaluations; lower scores indicate more negative evaluations). Spouses rated the discussions more positively if they reported low husband demand/wife withdraw patterns and also used fewer negative behaviors during discussions relative to more negative behaviors (ps<0.001) or more husband demand/wife withdraw patterns (p=0.03). Error bars are ±1 standard error.

Mutual communication avoidance (p=0.98), husband demand/wife withdraw (p=0.32), and positive discussion behavior (ps>0.41) were not related to spouses’ discussion evaluations. No other interactions between communication patterns and behaviors (ps>0.15) and or gender (ps>0.06) predicted discussion evaluations.

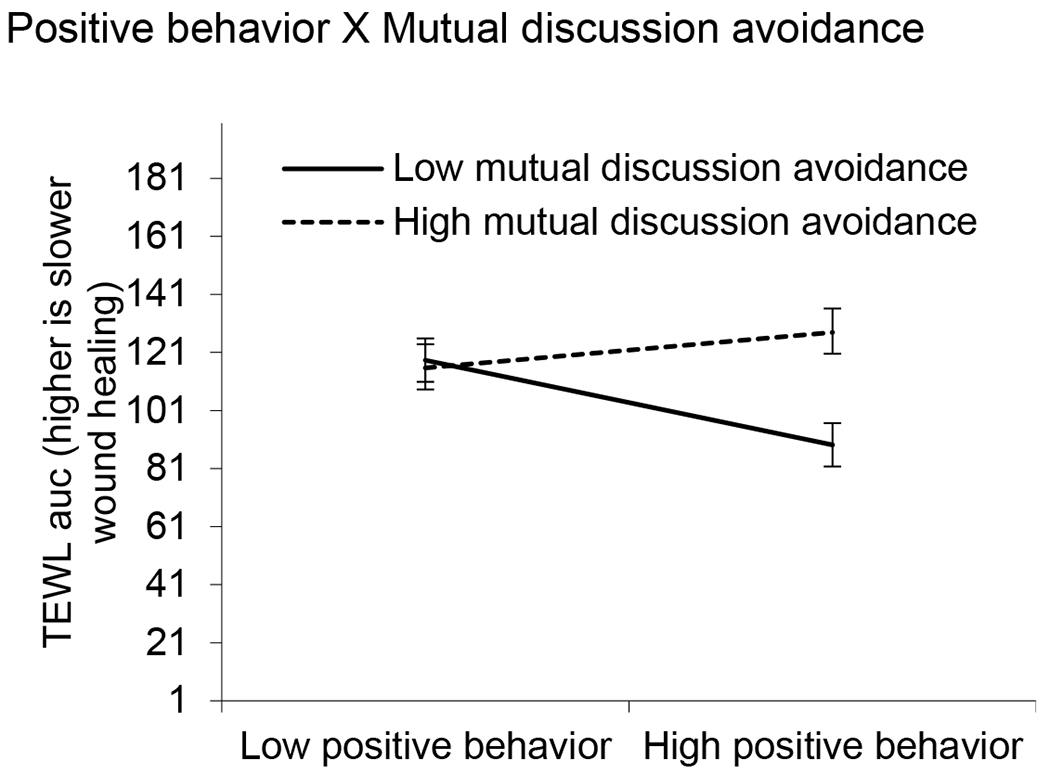

Typical Communication Patterns, Coded Laboratory Discussion Behaviors, and Wound Healing

Spouses’ greater mutual discussion avoidance predicted slower wound healing. Also, the two-way interaction depicted in Figure 5 showed that spouses’ wounds healed the fastest if they were typically less avoidant to discussions and used positive behaviors during lab discussions. That is, among spouses reporting low mutual avoidance, wounds healed faster if spouses used more positive behaviors relative to fewer positive behaviors during the discussions (b=−0.96, SE=0.35, p=0.007). Likewise, when spouses used more positive behaviors during the lab discussions, less mutually avoidant spouses’ wounds healed faster than more mutually avoidant spouses (b=10.05, SE=2.68, p<0.001). Mutually avoidant spouses’ wounds healed at similar rates regardless of their positive behaviors during discussions (b=0.40, SE=0.37, p=0.29). There were also no wound healing differences in more versus less mutually avoidant spouses when they used fewer positive behaviors (b=−0.69, SE=2.43, p=0.78).

Figure 5.

Visual depiction of interaction predicting wound healing. Spouses’ wounds healed faster if they reported low mutual discussion avoidance and used more positive behaviors during lab discussions compared to those using fewer positive behaviors (p=0.007) or greater mutual discussion avoidance (p<0.001). Error bars are ±1 standard error.

Blister wound healing was not related to mutual constructive communication (p=0.24), total demand-withdraw communication (p=0.06), wife demand/husband withdraw (p=0.19), husband demand/wife withdraw (p=0.10), and role in demand/withdraw communication (p=0.99). Other interactions between the communication patterns, positive or negative behavior, and gender did not predict wound healing (ps>0.07). Covariates showed blister wound healing was slower in spouses who were older (ps<0.05) and after the second visit (ps<0.05).

Discussion

In couples’ marital discussions across two visits, we examined both the unique and synergistic effects of typical self-reported communication patterns and discussion-based behaviors on spouses’ immune, emotional, and relational outcomes. Couples who reported using more demand/withdraw or mutual avoidance patterns had higher baseline inflammation, slower wound healing, greater negative emotion, lower positive emotion, and poorer discussion evaluations. In contrast, couples reporting mutual constructive patterns rated the discussions more favorably. Additionally, couples’ more negative and less positive patterns exacerbated behavioral effects: Spouses had wounds that healed more slowly, reported lower positive emotion, and evaluated the discussions less positively among those whose typical patterns and discussion-based behaviors were more negative and less positive. These findings are consistent with prior work demonstrating delayed wound healing in hostile spouses (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005); moreover, they extend this literature by demonstrating how typically negative communication patterns may color spouses’ reactions to marital events, intensifying their biological, emotional, and relational impact. Notably, these effects were particularly strong for women, illustrating chronic and acute marital negativity’s relational and health risks. These findings help explain how distressed marriages take such a strong toll on spouses’ health.

Self-Reported Typical Patterns and Pre-Discussion Baseline Inflammation

When examining typical communication patterns and pre-discussion inflammation, results showed spouses who reported greater demand/withdraw, husband demand/wife withdraw, and husband demand/withdraw more than wives also had higher baseline IL-6 levels. These effects differed by gender: Men’s IL-6 was similar regardless of their demand/wife withdraw patterns, whereas women’s IL-6 was higher in those with more frequent husband demand/wife withdraw communication. Moreover, men’s and women’s IL-6 was similar if couples used demand/withdraw patterns less often, but women had higher IL-6 than men if couples used husband demand/wife withdraw patterns more often. Accordingly, husband demand/wife withdraw patterns may have harsher effects on women’s inflammation relative to men’s. As shown in prior work, wife demand/husband withdraw patterns were associated with greater cortisol and norepinephrine reactivity to marital discussions (Heffner et al., 2006; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1996). The current findings suggest that heightened inflammation might also accompany husband demand/wife withdraw patterns, most notably for women.

Self-Reported Typical Patterns and Post-Discussion Wound Healing, Emotions, Evaluations

Findings between typical communication patterns and post-discussion outcomes revealed that spouses who reported greater mutual discussion avoidance had delayed wound healing. Couples who avoid discussions may not typically engage in stressful marital conversations. Engaging in such discussions as part of the study visits may have been even more stressful, contributing to slower healing. Thus, spouses’ wounds may have healed more slowly after engaging in these marital discussions because they would have otherwise avoided such conversations. Discussing relationship matters and concerns are key to maintaining relationships. Yet, couples who avoid marital discussions may not only face relationship risks but also immune challenges, leaving them vulnerable to acute and chronic illness (Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017). In addition, couples’ wife demand/husband withdraw patterns, husband demand/wife withdraw patterns, and mutual avoidance were associated with more negative and less positive post-discussion emotions and evaluations; in contrast, constructive patterns were related to more favorable discussion evaluations. Together, these findings are consistent with research linking relationship-compromising and -enhancing communication patterns to relational and health outcomes, including intimacy and distress (Manne et al., 2010; Manne et al., 2006). Moreover, this study demonstrates how couples’ chronically destructive communication patterns might negatively color how spouses feel about, evaluate, and react to common yet important marital conversations. These findings illustrate the value of addressing how various patterns—including demand/withdraw, mutual avoidance, and mutual constructive communication—contribute to couples’ relationships and health.

Synergistic Effects of Self-Reported Typical Patterns and Coded Behaviors on Post-Discussion Wound Healing, Emotions, and Evaluations

Couples’ typical patterns also interacted with discussion behaviors to predict spouses’ outcomes. First, among spouses reporting low mutual avoidance, wounds healed faster if they used more positive behaviors relative to fewer positive behaviors during the discussions. Thus, spouses’ wounds healed more quickly if they reported low mutual avoidance and more positive behaviors. However, even when couples used more positive discussion behaviors, their wound healing was slower if they typically mutually avoided important conversations. These findings are consistent with attribution theories suggesting that partners see marital events through their global relationship perceptions (Bradbury & Fincham, 1990; Karney, 2015). Couples’ typical patterns may have served as a filter through they responded to discussion behaviors. Accordingly, couples’ typically avoidant patterns may have reduced their positive behavior’s salutary effects. These findings are of particular importance because slowed wound healing is linked to increased acute and chronic illness risks (Kiecolt-Glaser, 2018). Previous research has shown that couples’ positive behaviors were related to faster wound healing and lower cortisol after marital discussions (Gouin et al., 2010; Shrout et al., 2020). Our findings support this work and also suggest that lower mutual avoidance may help facilitate wound healing, ultimately enhancing recovery and reducing health risks.

Furthermore, spouses rated the discussion tone and outcome more negatively if they used husband demand/wife withdraw patterns more often and used more negative discussion behaviors. Even if spouses used fewer negative discussions behaviors, evaluations were more negative if they reported using husband demand/wife withdraw patterns more often. However, the discussion was rated more positively if they used husband demand/wife withdraw patterns less often and used fewer negative behaviors during the discussion. As shown in previous research, compared to their less negative peers, couples using negative behaviors during discussions felt more negatively and less close (Wilson et al., 2018). The present findings suggest that even if spouses behave less negatively during discussions, they may view those discussions poorly if their typical communication involves demand/withdraw patterns.

Key Gender Differences in Post-Discussion Outcomes: Women’s Heightened Relational and Health Risks

Last, as expected, couples’ typical patterns and discussion behaviors had notable effects on women. Although there were no gender differences in couples using fewer negative behaviors across discussions, women’s post-discussion emotions and evaluations were more negative than men’s if couples used more negative behaviors. Interestingly and unexpectedly, in women reporting more frequent husband demand/wife withdraw patterns, positive emotion was lower if couples also used more positive discussion behaviors. Otherwise, if wives reported less frequent husband demand/wife withdraw patterns, wives’ positive emotion was higher regardless of couples’ positive behaviors. As suggested by attribution theory, women may have expected more negative behaviors during the discussions given their typical husband demand/wife withdraw patterns (Bradbury & Fincham, 1990; Karney, 2015). Experiencing less frequent husband demand/wife withdraw patterns in daily life may have helped promote more positive feelings even if their spouses were less positive during the lab discussions. However, the discrepancy between more negative typical patterns at home yet positive patterns in the lab might have contributed to more negative feelings. Though additional research is needed to test these possibilities, women may have interpreted their partners’ more positive behaviors as disingenuous or insincere.

Women also benefitted from positive communication patterns: Women’s post-discussion positive emotion was higher in those reporting mutual constructive communication patterns and using fewer negative behaviors during discussions. Thus, couples’ positive patterns helped offset the emotional toll of negative behaviors. These findings contribute to dyadic stress theories and research examining gender differences in the marriage—health link (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Shrout, 2021; Shrout et al., 2019). Negative communication patterns may cause concern and wear on women’s relationship and health perceptions, particularly given gendered socialization that increases time spent thinking about and monitoring their relationships (Cross & Madson, 1997; Orbuch et al., 2013). Likewise, women might experience more negative emotions and evaluations because they feel pressure to resolve marital issues (Silverstein et al., 2006). However, couples’ mutual constructive communication and feeling like their husbands contribute to resolutions may promote more positive perceptions. These findings help uncover pathways linking marital interaction to women’s health.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This study has multiple strengths and informs both research and theory on marriage’s health impact. Including both spouses allowed us to reveal key gender differences in biological, emotional, and relational responses to couples’ communication patterns and discussions. Likewise, capturing communication patterns and discussion behaviors across two study visits provided a window into couples’ everyday interactions and how they resolve issues in daily life. Including both self-reported patterns and coded discussion behaviors also allowed us to examine their associations: Compared to coded positive behaviors, negative behaviors had stronger associations with self-reported typical communication patterns. Interestingly, positive and negative discussion behaviors were not significantly correlated. This finding, however, is consistent with previous research (Shrout et al., 2020). It is possible couples who use more positive behaviors are not necessarily less negative, and more negative couples are not inevitably less positive. Couples, therefore, may use a combination of positive and negative behaviors. Additionally, most self-reported typical patterns and coded discussion behaviors were associated with the discussion evaluations, and the combination of self-reported patterns and coded behaviors predicted spouses’ outcomes. Previous work showed the effects of coded demand/withdraw behaviors on cortisol responses to conflict were no longer significant once self-reported demand/withdraw patterns were included in the model (Heffner et al., 2006). Our results extend these findings and suggest that both typical patterns and discussion-specific behaviors matter, and that couples’ typical patterns may color how they see and react to marital discussions. Accordingly, couples’ typical patterns and discussion-specific behaviors are important for understanding marriage’s health impact.

We also assessed health outcomes spanning immunological and emotional health across multiple timeframes; thus, we demonstrated how couples’ communication was linked to baseline inflammation levels, positive and negative emotion after laboratory marital discussions, and wound healing over two weeks. These findings are important because slowed wound healing, chronic inflammation, and emotional reactivity increase multiple disease risks (Kiecolt-Glaser, 2018). Likewise, distressed spouses are more likely to develop chronic disease than satisfied spouses (Liu & Waite, 2014; Troxel et al., 2005). This study suggests that both negative communication patterns and discussion behaviors pose far-reaching health effects and are pathways from distressed marriages to poor health.

One limitation of the study is that couples were primarily white, educated, and in different-gender relationships. Communication patterns and behaviors, along with their relational and health effects, should be examined in more diverse couples, particularly same-gender couples given the multiple gender differences. We examined women’s and men’s marital discussions to help understand and explain why marital stress negatively affects women more than men. However, it is worthwhile to move beyond the gender binary when examining responses to relationship discussions. Including and focusing on individual across diverse genders and sexualities would expand our theoretical and empirical understanding of a relationship’s wide-ranging health impact.

We also examined couples’ marital discussion behaviors in a laboratory setting. Although laboratory studies provide more conservative estimates (Heyman, 2001), researchers might consider using daily designs to examine couples’ immune and emotional responses to marital discussions. In addition, we were interested in how spouses felt about and evaluated their marital discussions, but couples did not report on their specific lab discussion behaviors. It would be interesting to examine how accurately spouses reported their own and their spouses’ discussion behaviors. Given that our findings suggested spouses’ typical patterns altered how they reacted to the marital discussions, self-reported discussion behaviors may influence how accurately they see their own and their partners’ discussion behaviors. Recent research demonstrated that stressed individuals perceived their partners’ behaviors as more negative than positive (Neff & Buck, 2022). It is possible that spouses may experience heightened responses to marital interactions if they overreport negative behaviors underreport positive behaviors. Additional research is needed to test these possibilities and address how both perceived and coded communication patterns jointly affect couples’ relationships and health. Additionally, counterbalancing the marital discussions between the two visits would have been ideal but were concerned that a conflict interaction on top of the blister wound procedure at the first session would increase participant apprehension and concern, as well as lead to greater dropout. Future work might consider using counterbalanced designs and including follow-up assessments over longer periods to address the long-term health impact of couples’ communication.

Conclusion

In this study of couples’ communication and health, we found that couples who reported greater use of more demand/withdraw and mutual avoidance patterns had higher baseline inflammation, slower wound healing, greater negative emotion, lower positive emotion, and poorer discussion evaluations. Their more mutually constructive peers had better immune, emotional, and relational outcomes. The combination of negative communication patterns and behaviors predicted slower wound healing, lower positive emotions, and more negative discussion evaluations. Compared to men, women’s immune and emotional health were more affected by couples’ negative communication patterns and behaviors. These findings help identify how distressed marriages pose long-term relational and health risks, most notably in women.

Highlights.

Married couples had blood draws, received blister wounds, and engaged in discussions

Negative communication patterns augmented behavioral effects on wound healing

Negative patterns and behaviors predicted more negative discussion emotions and evaluations

Effects were stronger in women than men

The findings highlight how distressed marriages take a toll on spouses’ health

Funding:

Work on this project was supported by an Ohio State University Presidential Postdoctoral Scholars Fellowship, and NIH grants KL2TR002530, UL1TR002529, P01 AG16321, P50 DE13749, T32 CA229114, and TL1TR002735.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG, (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. In Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom BR, Atkins DC, Eldridge K, Mcfarland P, Sevier M, & Christensen A (2011). The Language of Demand / Withdraw: Verbal and Vocal Expression in Dyadic Interactions. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(4), 570–580. 10.1037/a0024064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. In Source: Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) (Vol. 57, Issue 1). [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, & Fincham FD, (1990). Attributions in Marriage: Review and Critique. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 3–33. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughlin JP, & Huston TL, (2002). A contextual analysis of the association between demand/withdraw and marital satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 9(1), 95–119. 10.1111/1475-6811.00007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Eldridge K, Catta-Preta AB, Lim VR, & Santagata R, (2006). Cross-cultural consistency of the demand/withdraw interaction pattern in couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(4), 1029–1044. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00311.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, & Heavey CL, (1990). Gender and social structure in the demand/withdraw pattern of marital conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(1), 73–81. 10.1037//0022-3514.59.1.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, & Madson L, (1997). Models of the Self: Self-Construals and Gender. Psychological Bulletin, 122(1), 5–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge KA, & Christensen A, (2002). Demand-Withdraw Communication during Couple Conflict: A Review and Analysis. Understanding Marriage, 289–322. 10.1017/cbo9780511500077.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Marucha PT, Maccallum RC, Laskowski BF, & Malarkey WB (1999). Stress-Related Changes in Proinflammatory Cytokine Production in Wounds. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin JP, Carter CS, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Loving TJ, Stowell J, & Kiecolt-Glaser JK, (2010). Marital behavior, oxytocin, vasopressin, and wound healing. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(7), 1082–1090. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin JP, & Kiecolt-Glaser JK, (2011). The Impact of Psychological Stress on Wound Healing: Methods and Mechanisms. In Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America (Vol. 31, Issue 1, pp. 81–93). 10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JE, Glaser R, Loving TJ, Malarkey WB, Stowell JR, & Kiecolt-Glaser JK, (2009). Cognitive Word Use During Marital Conflict and Increases in Proinflammatory Cytokines. Health Psychology, 28(5), 621–630. 10.1037/a0015208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heavey CL, Layne C, & Christensen A (1993). Gender and Conflict Structure in Marital Interaction: A Replication and Extension. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(1), 16–27. 10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner KL, Loving TJ, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Himawan LK, Glaser R, & Malarkey WB (2006). Older spouses’ cortisol responses to marital conflict: Associations with demand/withdraw communication patterns. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 317–325. 10.1007/s10865-006-9058-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, (2001). Observation of couple conflicts: Clinical assessment applications, stubborn truths, and shaky foundations. Psychological Assessment, 13(1), 5–35. 10.1037//1040-3590.13.1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, (2004). Rapid Marital Interaction Coding System (RMICS). In Kerig PK & Baucom DH (Eds.), Rapid Marital Interaction Coding System (RMICS). (pp. 67–93). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Birmingham W, & Jones BQ, (2008). Is there something unique about marriage? The relative impact of marital status, relationship quality, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 35(2), 239–244. 10.1007/s12160-008-9018-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Robles TF, & Sbarra DA, (2017). Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American Psychologist, 72(6), 517–530. 10.1037/amp0000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, (2015). Why marriages change over time. In APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Volume 3: Interpersonal relations. (pp. 557–579). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14344-020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL, (2006). Dyadic data analysis. In Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, (2018). Marriage, divorce, and the immune system. American Psychologist, 73(9), 1098–1108. 10.1037/amp0000388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Bane C, Glaser R, & Malarkey WB, (2003). Love, marriage, and divorce: Newlyweds’ stress hormones foreshadow relationship changes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 176–188. 10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Jaremka L, Andridge R, Peng J, Habash D, Fagundes CP, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, & Belury MA, (2015). Marital discord, past depression, and metabolic responses to high-fat meals: Interpersonal pathways to obesity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 52(1), 239–250. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Loving TJ, Stowell JR, Malarkey WB, Lemeshow S, Dickinson SL, & Glaser R, (2005). Hostile marital interactions, proinflammatory cytokine production, and wound healing. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(12), 1377–1384. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton T, Cacioppo JT, MacCallum RC, Glaser R, & Malarkey WB (1996). Marital conflict and endocrine function: Are men really more physiologically affected than women? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 324–332. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Newton TL (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127(4), 472–503. 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, & Glaser R, (2003). Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(15), 9090–9095. 10.1073/pnas.1531903100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Wilson S, (2017). Lovesick: How couples’ relationships influence health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(13), 421–443. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Wilson SJ, Bailey ML, Andridge R, Peng J, Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Malarkey WB, Laskowski B, & Belury MA, (2018). Marital distress, depression, and a leaky gut: Translocation of bacterial endotoxin as a pathway to inflammation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 98(April), 52–60. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, & Waite L, (2014). Bad marriage, broken heart? Age and gender differences in the link between marital quality and cardiovascular risks among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(4), 403–423. 10.1177/0022146514556893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Badr H, Zaider T, Nelson C, & Kissane D, (2010). Cancer-related communication, relationship intimacy, and psychological distress among couples coping with localized prostate cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 4(1), 74–85. 10.1007/s11764-009-0109-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Ostroff JS, Norton TR, Fox K, Goldstein L, & Grana G (2006). Cancer-related relationship communication in couples coping with early stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 15(3), 234–247. 10.1002/pon.941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH, (2014). Handbook of Biological Statistics. (3rd ed.). Sparky House Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, & Buck AA, (2022). When Rose-Colored Glasses Turn Cloudy: Stressful Life Circumstances and Perceptions of Partner Behavior in Newlywed Marriage. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 194855062211254. 10.1177/19485506221125411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orbuch TL, Bauermeister JA, Brown E, & Mckinley BD, (2013). Early Family Ties and Marital Stability Over 16 Years: The Context of Race and Gender. Family Relations, 62(2), 255–268. 10.1111/fare.12005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp LM, Kouros CD, & Cummings EM, (2009). Demand-withdraw patterns in marital conflict in the home. Personal Relationships, 16(2), 285–300. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01223.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch LA, & Bradbury TN, (1998). Social support, conflict, and the development of marital dysfunction. In Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (Vol. 66, Issue 2, pp. 219–230). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/0022-006X.66.2.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, & McGinn MM, (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 140–187. 10.1037/a0031859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout MR, (2021). The Health Consequences of Stress in Couples: A Review and New Integrated Dyadic Biobehavioral Stress Model. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health, 16. 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout MR, Brown RD, Orbuch TL, & Weigel DJ, (2019). A multidimensional examination of marital conflict and subjective health over 16 years. Personal Relationships, 26(3), 490–506. 10.1111/pere.12292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout MR, Renna ME, Madison AA, Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Malarkey WB, & Kiecolt-glaser JK, (2020). Cortisol slopes and conflict: A spouse’s perceived stress matters. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 121, 104839. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout MR, Renna M, Madison AA, Alfano CM, Povoski SP, Lipari AM, Agnese DM, Farrar WB, Carson WE, & Kiecolt-Glaser JK, (2021). Breast cancer survivors’ satisfying marriages predict better psychological and physical health: A longitudinal comparison of satisfied, dissatisfied, and unmarried women. Psycho-Oncology, 30(5), 699–707. 10.1002/pon.5615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein R, Buxbaum Bass L, Tuttle A, Knudson-Martin C, & Huenergardt D, (2006). What Does It Mean to Be Relational? A Framework for Assessment and Practice. Family Process, 45(4), 391–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel WM, Matthews KA, Gallo LC, Lewis, ;, & Kuller H (2005). Marital Quality and Occurrence of the Metabolic Syndrome in Women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165, 1022–1027. https://jamanetwork.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanic R, & Kulik J, (2011). Toward an Understanding of Gender Differences in the Impact of Marital Conflict on Health. Sex Roles, 65(5), 297–312. 10.1007/s11199-011-9968-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SJ, Bailey BE, Jaremka LM, Fagundes CP, Andridge R, Malarkey WB, Gates KM, & Kiecolt-Glaser JK, (2018). When couples’ hearts beat together: Synchrony in heart rate variability during conflict predicts heightened inflammation throughout the day. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 93(September 2017), 107–116. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]