Abstract

Objective:

This systematic literature review presents an overview of studies that assess the experiences of Hispanics adults with 1) activation of emergency medical services (EMS); 2) on-scene care provided by EMS personnel; 3) mode of transport (EMS versus non-EMS) to an emergency department (ED); and 4) experiences with EMS before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

A bibliographic database search was conducted to identify relevant studies on Ovid MEDLINE (PubMed), Web of Science, EMBASE, and CINAHL. Quantitative, mixed-methods, and qualitative studies published in English or Spanish were included if they discussed Hispanic adults’ experiences with EMS in the U.S. between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2021. The Hawker et al. quality assessment instrument was used to evaluate the quality of studies.

Results:

Of the 43 included studies, 13 examined EMS activation, 13 assessed on-scene care, 22 discussed mode of transport to an ED, and 4 described Hispanic adults’ experiences with EMS during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hispanics were less likely to activate EMS (N=7), less likely to receive certain types of on-scene care (N=6), and less likely to use EMS as the mode of transport to an ED (N=13), compared to non-Hispanic Whites. During the early COVID-19 pandemic period (March to May 2020), EMS use decreased by 26.5% compared to the same months during the previous four years.

Conclusions:

The contribution of this study is its attention to Hispanic adults’ experiences with the different phases of the U.S. EMS system.

Keywords: emergency medical services, prehospital care, Hispanic health, health disparities

BACKGROUND:

Emergency medical services (EMS) in the United States (U.S.) are activated with a call to 9–1–1, an action that initiates a series of events, including dispatch of emergency services, on-scene care, and transport to an emergency department (ED). EMS provides critical and time-sensitive care that impacts patients’ trajectories through other sectors of the U.S. healthcare system. For example, the use of EMS, compared to transport by private vehicle, is associated with more rapid ED arrival, earlier medical assessment, and fewer treatment delays in the ED.1,2

EMS serves as an entry point into the U.S. healthcare system, especially for underserved populations, including Hispanics who often have challenges accessing preventive and diagnostic care.3 Hispanics are the second largest racial and ethnic population in the U.S after non-Hispanic Whites,4 with a projected population increase from 62.1 million in 2020 to 111 million by 2060.4 Mexicans, Central Americans, and Puerto Ricans comprise the three largest Hispanic subpopulations at 61.6%, 9.3% and 9.6%, respectively.4 Over 50% of Hispanics reside in California, Texas and Florida.4 Among Hispanics, 71.1% speak a language other than English at home.4

Existing literature shows that lower socioeconomic status,5 patient-provider language discordance,5 limited English proficiency,5 provider bias,5 and discrimination5 are all associated with Hispanics’ receiving lower-quality medical care across many areas in health care, including emergency medicine,5 oncology3 and EMS.6,7 Hispanics also have the lowest rates of health insurance due to employment that does not provide employer-based health insurance, eligibility restrictions associated with immigration status, and fear of being considered a public charge if they apply to government-sponsored health insurance.8

Over the past two decades, policy changes have impacted Hispanics’ access to health care.8 In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) substantially increased rates of health insurance for all racial and ethnic groups, including Hispanics, although this population continued to experience higher uninsured rates, compared to non-Hispanic Whites.8 The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to make Medicaid expansion optional at the state-level and the elimination of the ACA’s individual mandate also disproportionately impacted Hispanics, contributed to increases in the uninsurance rate in this population, limited access to preventive and diagnostic care, and increased the likelihood of EMS use.7,8

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic literature review to provide an overview of Hispanics’ experiences with the different phases of the EMS system in the U.S. and to identify existing research gaps. Our objective is to present a comprehensive review that assesses Hispanic adults’ experiences with 1) initial activation of EMS; 2) on-scene care provided by EMS personnel; 3) mode of transport (EMS versus non-EMS) to an ED; and 4) experiences with EMS before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS:

Data Sources and Search Strategy:

This review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P). The principal investigator developed the search strategy with the assistance of a librarian specialist; the search was conducted on December 27, 2021. Relevant studies were identified on Ovid MEDLINE (PubMed), Web of Science, EMBASE, and CINAHL for January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2021. The search terms included: “emergency medical services” OR “pre-hospital care” OR “prehospital care” AND “Hispanic” OR “Latino” OR “Latina” OR “Latinx.” The protocol for this review was submitted and approved by PROSPERO (CRD42022292926).

Article Selection:

Studies were included in this review if they examined Hispanic adults aged 18 years and olders’ experiences with EMS in the U.S. EMS was defined as emergency services provided by emergency personnel, including emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and/or paramedics, in the prehospital care setting. Prehospital care setting was defined as emergency services provided prior to ED arrival. Quantitative, mixed methods and qualitative studies were included if published in English or Spanish between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2021.

We excluded studies that did not have a Hispanic category. Further disaggregation by patient ethnicity was not possible in most EMS datasets. Studies were also excluded if they focused on pediatric patients or those under the age of 18, examined medical care exclusively provided in a non-prehospital care setting, or examined health care provided in the prehospital care setting by non-EMS providers, such as general practitioners or civilian bystanders. We also excluded studies that examined air medical services, since these transports are requested by healthcare providers, not patients. We also excluded clinical trials, literature reviews, letters to the editor, editorials, and study protocols.

Data Extraction:

Two researchers independently reviewed titles and abstracts of identified studies using Covidence systematic review software, hereinafter referred to as Covidence. Abstracts that met inclusion criteria were selected for full-text review by two researchers. A third researcher resolved discrepancies that arose from abstract review to study inclusion. The following study characteristics were extracted from included studies: title, author names, publication year, geographic location of study, study design, total sample size, total sample size of Hispanics and key findings (See Supplemental Table 1). The studies were then categorized to align with the review’s objective and four main foci.

Assessment of Study Quality:

The Hawker et al.9 quality assessment instrument was used to assess the quality of studies. This instrument was developed to appraise quantitative, mixed methods and qualitative studies.9 Two researchers used this quality assessment instrument to examine nine components of each study: title and abstract, introduction and aims, methods and data, sampling, data analysis, ethics and bias, results, transferability or generalizability, and implications and usefulness.9 Each of the nine components was independently scored for each study by two researchers using a four-point scale: a. very poor (1-point), b. poor (2-points), c. fair (3-points), and d. good (4-points). After the two researchers individually scored each study, they met and discussed discrepancies in each score. The scores from the nine components were summed to obtain an overall score for each study. The overall possible scores ranged from very poor (a score of 9) to very good (a score of 36). Articles were excluded if the overall score was 18 or less, which is considered very poor to poor quality.9 None of the studies scored 18 or less.

RESULTS:

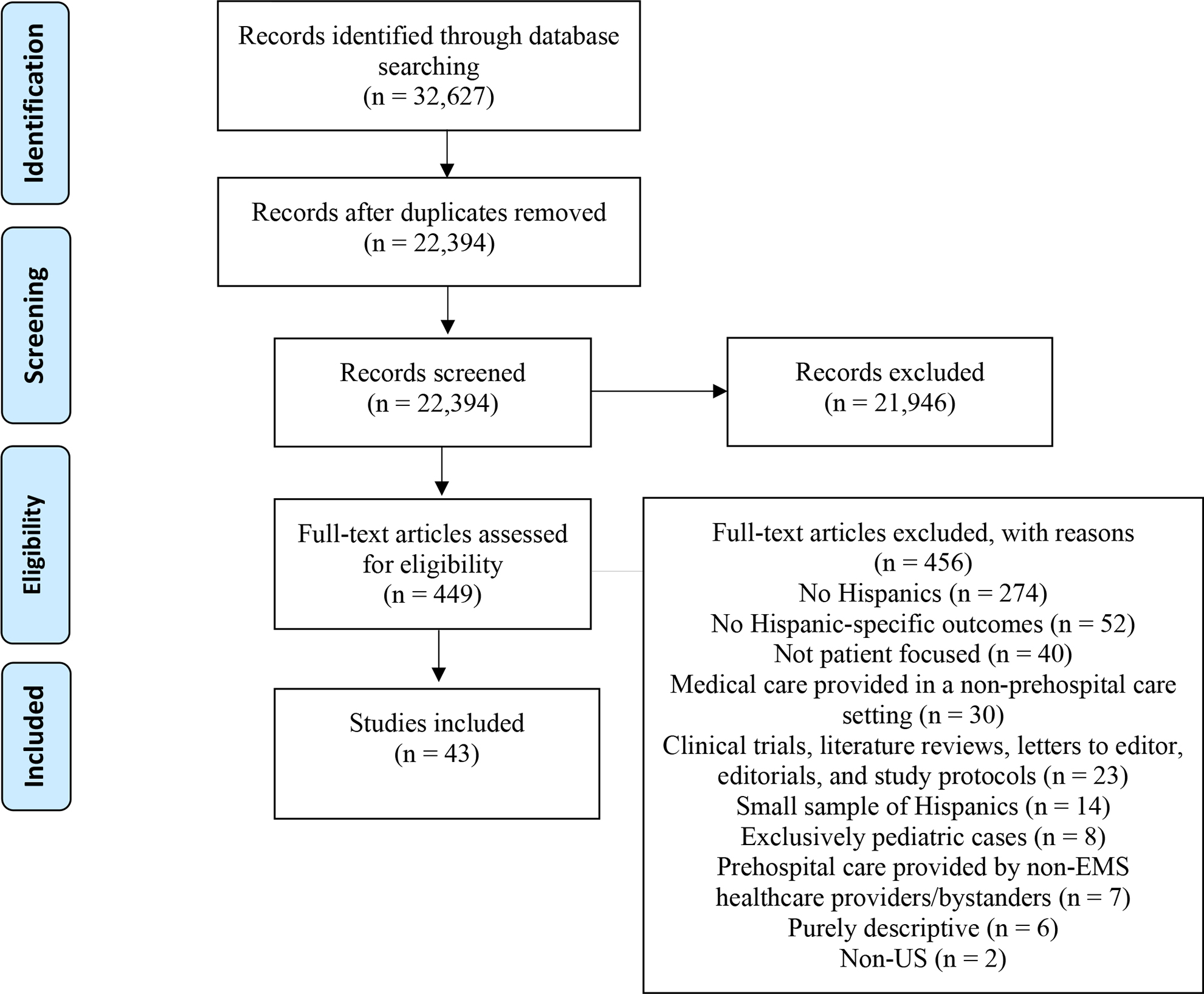

The database search identified 32,627 studies, of which 10,233 were duplicates. The duplicate studies were removed using Covidence. The remaining 22,394 study titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion criteria by two researchers. Of the 22,394 studies, 21,946 were excluded and 449 continued to full-text review. The 449 studies were independently read by two researchers to determine compliance with the inclusion criteria. Of the 449 studies, 43 studies were included in this review (See Figure 1).

Figure 1:

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Of the 43 included studies, 403,6,7,10–46 were quantitative, 3 were mixed methods47–49 and none were qualitative (See Table 1). All of the studies assessed Hispanics’ experiences with the EMS system in the U.S, although some studies focused on the national (n=15),2,7,10,11,13,16,21–22,24,28,31,35–36,40–41 state (n=11),6,14–15,17–18,20,25,39,42,44,46 or local level (n=17). 12,19,23,26–27,29–30,32–34,37,38,45,47–49 Hispanic sample size ranged from 1 to 99 (n=4), 14,32,40,42,47 100 to 999 (n= 17),12,18–19,27,29–30,33–34,37–39,43–45,47–49 1000 to 9999 (n=12),6,11,15–16,22–24,26,28,31,35,41 and 10,000+ (n=9).2,7,10,13,20,21,25,36,46 The majority of the studies assessed Hispanic and non-Hispanic White differences in EMS experiences, except for one study47 that described differences among different ethnic subgroups of Hispanics. Of the studies that assessed Hispanic and non-Hispanic White differences, three explicitly focused on differences between Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites.26, 37, 49

Table 1:

Overview of included studies that assess Hispanic adults’ experiences with the emergency medical services (EMS) system in the United States between 2000 and 2021

| Study characteristic | Number of studies | Percent |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Initial EMS activation (N=13) | ||

| Hispanics and non-Hispanic White differences in EMS activation | 9 | 69.2 |

| Hispanic (Mexican Americans specifically) and non-Hispanic White differences in EMS activation | 3 | 23.1 |

| Hispanic and Haitian, West Indian and African American differences in EMS activation | 1 | 7.7 |

| On-scene care (N=13) | ||

| Prehospital symptom recognition | 1 | 7.7 |

| EMS response time | 3 | 23.1 |

| Out-of-hospital intervention | 3 | 23.1 |

| Time spent on scene | 1 | 7.7 |

| Pain medication administration and assessment | 5 | 38.4 |

| Modes of transportation (N=22) | ||

| EMS vs non-EMS transport to the ED | 20 | 90.9 |

| ED bypassing, transportation to a reference ED and transportation to a safety-net ED | 2 | 9.1 |

| Use of EMS during COVID-19 (N=4) | ||

| Respiratory distress | 1 | 25.0 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 | 25.0 |

| Overdose-associated cardiac arrests | 1 | 25.0 |

| Non-transports | 1 | 25.0 |

| Publication year | ||

| 2000–2009 | 6 | 14.0 |

| 2010–2019 | 24 | 55.8 |

| 2020–2021 | 13 | 30.2 |

| Geographic Granularity | ||

| National | 15 | 34.9 |

| State | 11 | 25.6 |

| Local | 17 | 39.5 |

| Methods | ||

| Quantitative | 40 | 93.0 |

| Mixed methods | 3 | 7.0 |

| Qualitative | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sample size used in the study | ||

| 1–99 | 4 | 9.3 |

| 100–999 | 17 | 39.5 |

| 1000–9,999 | 12 | 27.9 |

| 10,000+ | 9 | 20.9 |

| No sample size reported | 1 | 2.3 |

| Number of Studies Published Before and After the Implementation of the ACA | ||

| Before the year ACA was signed into law (2000–2009) | 6 | 14.0 |

| ACA signed into law and implemented (2010–2021) | 37 | 86.0 |

| Final score for bias assessment 1 | ||

| Very Poor (1–9) | 0 | |

| Poor (10–18) | 0 | |

| Fair (19–27) | 2 | 4.7 |

| Good (28–36) | 41 | 95.3 |

The final score for bias assessment is given to each study using the Hawker et al. quality assessment instrument.

Six studies were published between 2000 and 2009,11,12,27,36,42,49 24 studies were published between 2010 and 20192,6,7,13,15,17–19,21–22.24,26,29–30,35,37–41,43,45–47 (a four-fold increase from the previous decade), and 13 studies were published during the COVID-19 pandemic, between 2020 and 2021.10,14,16,20,23,25,28,31–34,44,48 Six studies were published before the ACA was signed into law (2000–2009),11–12,27,36,42,49, while 37 studies were published the year the ACA was signed into law or later (2010–2021).2,6–7,10,13–26,28–35,37–41,43–48 Of the 43 studies included in this review, 13 examined EMS activation,11,12,17,18,26,28,30,35,38,44,47–49 13 assessed types of on-scene care,2,6,12,18,19,22,27,31,33,39,41,43,45 22 discussed modes of transport to an ED,2,7,10–15,18,20–21,24,26,29,32,36–38,40,42,46–47 and 4 described Hispanic adults’ experiences with EMS before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.16,23,25,34 The quality assessment scores ranged from 24 to 36, with a mean of 32.6, across the 43 studies.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Activation of EMS

Thirteen studies examined activation of EMS via a 9–1–1 call.11,12,17,18,26,28,30,35,38,44,47,48,49 Most studies (n=7) 11,17,26,28,35,47,49 found that Hispanics were less likely to activate EMS, especially for time-sensitive health conditions, such as stroke 17,26,28,35,49 and heart attack.11,47 Hispanics were less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to recognize stroke symptoms,28 acknowledge the time-sensitive window for stroke treatment,49 intend to call 9–1–1 for stroke symptoms,17,35,49 and call 9–1–1 for stroke or heart attack.11,26.28 Among Hispanics experiencing a heart attack, women were more likely than men to call 9–1–1.30

Hispanics were more likely to adopt a passive response (drinking tea, laying down, or praying) rather than an active response (calling 9–1–1), compared to Haitians, West Indians, and African Americans.47 Hispanics in this study were mostly Mexican and Puerto Rican.47 From cardiac symptom onset to ED arrival, Hispanics had the shortest time to arrival of 6.00 hours, compared to 6.62 hours for African Americans, 7.83 hours for West Indians, and 8.24 hours for Haitians.47 The emergency care sought by all four groups, however, extended beyond the recommended time period of 3 hours from cardiac symptom onset to ED arrival.47

Of the 13 studies that examined EMS activation, the remaining six studies found statistically non-significant differences or reported that Hispanics were more likely to use EMS compared to non-Hispanic Whites.12,18,30,38,44,48 One study found statistically non-significant differences in cardiac symptom onset to hospital arrival between non-English preferring and English-preferring patients, where most of the non-English preferring patients were Hispanic.44 Another study reported that EMS activation among undocumented Hispanic immigrants was the least difficult sector to access in the U.S. healthcare system, although the overall percentage who reported challenges with EMS was high at 50.8%.48 Another study found that Hispanics were more likely to call 9–1–1 if they experienced chest pain or a heart attack, compared to non-Hispanic Whites, although the overall percentage of 9–1–1 calls in both groups was low.30

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Types of On-Scene Care Provided

Thirteen studies assessed types of on-scene care.2,6,12,18,19,22,27,31,33,39,41,43,46 Among these, eight examined EMS response time,2,12,18,33 time spent on scene,39 prehospital recognition of symptoms19 and administration of out-of-hospital interventions 22,33,46 between Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites. EMS response time and return of spontaneous circulation following resuscitation were comparable between Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites experiencing sudden cardiac arrests.12,33 EMS personnel spent less time on scene with Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic Whites experiencing chest pain.39 Among Hispanics, EMS personnel spent less time on scene when a language incongruence was noted compared to no language incongruence.39 Less time on scene may be an appropriate action since chest pain is a time-sensitive symptom. On the contrary, less time on scene may also be indicative of suboptimal prehospital care. In another study, Hispanic patients were less likely to have a correct prehospital recognition of stroke, another time-sensitive health condition, compared to non-Hispanic Whites.19 Hispanics were also less likely to receive an electrocardiogram and more likely to receive mechanical cardiopulmonary resuscitation, compared to non-Hispanic Whites.22,46

Among the 13 studies, five studies focused on pain assessment6 and pain medication administration.6,27,31,41,43 Hispanics were less likely to receive a pain assessment compared to non-Hispanic Whites.6 Among patients who received a pain assessment, Hispanics reported a higher average pain score compared to non-Hispanic Whites.6 The findings for pain medication administration were mixed. Two studies found that Hispanics were less likely to receive pain medication,6,43 two studies reported statistically non-significant differences in morphine27 or nitroglycerin31 administration, and one study found that Hispanics were more likely to receive aspirin,41 compared to non-Hispanic Whites.

Mode of Transportation to an ED

Twenty-two studies assessed mode of transportation to the ED among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites.2,7,10–15,18,20,21,24,26,29,32,36–38,40,42,45,47 Of the 22 studies, 13 studies found that Hispanics, including those with time-sensitive health conditions, such as stroke 2,7,10,14,26,29,37,38 and heart attack,11,24,45 were less likely to use EMS versus non-EMS forms of transport to the ED, compared to non-Hispanic Whites.2,7,10,11,14,15,24,26,29,36–38,45 Hispanic males and females were less likely to use EMS for transport to an ED compared to non-Hispanic Whites of the same gender.7 Among Hispanics experiencing a stroke, males were less likely than females to use EMS as the mode of transport to an ED.7 EMS use as the mode of transport was associated with earlier ED arrival,24 faster triage,2,14 and more rapid treatment.2,14

Among the 22 studies, two studies assessed Hispanics’ experiences with ED bypassing, transportation to a reference ED, and transportation to a safety-net ED.20,21 Hispanics were more likely to experience ED bypassing (i.e. be transported to an ED other than the one most proximate to them).20 Hispanics were less likely to be transported to the reference ED (i.e. most frequent ED destination) compared to non-Hispanic Whites from the same ZIP code.21 Hispanics were more likely to be transported to a safety-net ED (i.e. ED that is legally obligated to provide health care regardless of a patient’s insurance status) compared to non-Hispanic Whites from the same ZIP code.21

Of the 22 studies, six studies found statistically non-significant findings between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites for EMS and non-EMS modes of transport to the ED.12,13,40,42,47 One study found statistically significant differences in EMS time intervals (e.g. time from 9–1–1 call to EMS arrival on scene, time on scene, and time of on scene departure to hospital arrival) between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites, although these differences were small and not clinically significant.18

Hispanic Adults’ Experiences with EMS During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Four studies examined Hispanic adults’ experiences with EMS during the early COVID-19 pandemic period.16,23,25,34 EMS calls decreased by 26.5% during the early pandemic period (March to May 2020), compared to the same months in the previous four years (2016–2019).34 Non-transports (e.g. EMS calls that do not result in an ambulance transport) increased by 46.6% during the early pandemic period.34 The increase in non-transports may be explained by EMS recommended non-transports, caller-generated refusals due to fear of COVID-19 infection, and individuals not wanting to burden the healthcare system.34 The early pandemic period was also characterized by an increase in the proportion of EMS calls attributed to respiratory distress,25 cardiac arrest23 and overdose-associated cardiac arrests,16 especially among Hispanics. The higher likelihood of these health conditions may be partially explained by the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Hispanics.16,23,25,34

DISCUSSION

This systematic review found disparities in EMS activation, on-scene care and EMS transports among Hispanic adults, compared to non-Hispanic Whites. These disparities in EMS may be attributed to multiple factors, including delayed symptom recognition, underestimation of symptom severity, and lack of knowledge regarding time-sensitive windows, particularly for cardiovascular health outcomes (i.e. heart attack and stroke) among Hispanic adults. The underrepresentation of Hispanics in EMS professions may increase fear of discrimination among Hispanic adults experiencing an emergency. Lack of racial, ethnic and linguistic representation in the EMS workforce may also increase patient-provider language discordance, which contributes to language barriers that impact access and provision of EMS. Lack or inadequate health insurance coverage may deter Hispanic adults’ from using EMS due to perceived costs.

The findings from this review are consistent with disparities identified in the ED between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites.5 Hispanics are less likely to receive electrocardiograms and chest x-rays in the ED, compared to non-Hispanic Whites.5 In this review, the findings for pain medication administration were mixed when comparing Hispanics to non-Hispanic Whites. The ED literature, however, has found that Hispanics are less likely to receive pain medication for long-bone fractures, headaches and back pain, compared to non-Hispanic Whites.5 A study also found that Hispanics require more ED visits for asthma, compared to non-Hispanic Whites, which may be indicative of a lack of or limited access to preventive and diagnostic services.5

Future EMS research should consider the heterogeneity within the Hispanic population by considering other socio-demographic characteristics including, national heritage, country of origin, primary language, immigration status, and place of residence. Future EMS studies should aim to use representative samples that result in generalizable findings. Most of the current EMS datasets use convenience samples that are not representative of the populations served. To achieve representative samples, EMS agencies need to reassess how prehospital data is recorded and reported at the local, state and national levels. Qualitative and mixed methods studies are needed to study Hispanics’ use of EMS as these methods provide breadth and depth to expand on findings from quantitative studies. In this review, we did not find any qualitative study that met all of our inclusion criteria. Some challenges that may arise when conducting qualitative studies in the EMS context, especially when trying to understand past EMS experiences, include severely ill or deceased patients, privacy concerns that make it difficult for researchers to contact patients, incomplete patient information, and trying to locate hard-to-reach populations. Future research on Hispanics’ experiences with EMS should also consider the changing policy environments. In this review, we focused on understanding changes in EMS use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, although other potential avenues for in-depth research may assess EMS use before and after the ACA, state Medicaid expansions, before and after Medicare eligibility, different types of Medicare enrollment (Traditional vs. Medicare Advantage) or before and after different presidential administrations.

Limitations:

This review highlights important limitations in EMS research. First, most of the studies rely on non-probability samples,6,16,18,22,24–25,27,29–31–34,38–39,41–49 which hinder the generalizability of the findings. Even the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS), the only national EMS database in the U.S., uses a large convenience sample, not a representative sample.50 Second, most of the studies use cross-sectional study designs,7,11,13,17,19,22–23,28,35–36–37,39,41–42,45,47–49, which make it difficult to infer causality and assess changes over time. Third, a few studies use small sample sizes of Hispanics,14,32,40,42 which may contribute to statistically non-significant results in those studies. Fourth, local, state, and national EMS datasets often represent activations, not patients.50 This limitation, however, is consistent over time and should not impact analyses of EMS activations.

CONCLUSION

Health equity cannot be achieved in the U.S. healthcare system without identifying and addressing health care disparities in the prehospital setting. The contribution of this review is its attention to Hispanic adults’ experiences with the different phases of the EMS system in the U.S. This review suggests Hispanic versus non-Hispanic White disparities in EMS activation,17 types of on-scene care provided,6 and EMS versus non-EMS modes of transport to the ED.32 EMS use patterns among Hispanic adults also changed during the early COVID-19 pandemic period, compared to the pre-pandemic period.16,23,25

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1: Specific characteristics of the included individual studies that assess Hispanic adults’ experiences with the emergency medical services (EMS) system in the United States between 2000 and 2021

Acknowledgments:

We thank the following individuals for comments on earlier drafts of this paper: Melina Melgoza, Maksim Gusarov, Jennifer Archuleta, Josefina Flores Morales, Gabino Abarca, Julian Ponce, and Hector Grajeda. We also thank Wynn Tranfield for her assistance with the database searches.

Esmeralda Melgoza is funded by the Eugene Cota Robles Fellowship. Valeria Cardenas is funded by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32AG000037. Hiram Beltran-Sanchez is supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2C-HD041022) to the California Center for Population Research at UCLA.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Loh JP, Satler LF, Pendyala LK, et al. Use of emergency medical services expedites in-hospital care processes in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2014;15(4):219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ekundayo OJ, Saver JL, Fonarow GC, et al. Patterns of emergency medical services use and its association with timely stroke treatment: findings from Get With the Guidelines-Stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(3):262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Profile: Hispanic/Latino Americans U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. Updated 09/26/2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=64 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zavala VA, Bracci PM, Carethers JM, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(2):315–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heron SL, Stettner E, Haley LL Jr. Racial and ethnic disparities in the emergency department: a public health perspective. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006;24(4):905–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennel J, Withers E, Parsons N, Woo H. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pain Treatment: Evidence From Oregon Emergency Medical Services Agencies. Med Care. 2019;57(12):924–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mochari-Greenberger H, Xian Y, Hellkamp AS, et al. Racial/Ethnic and Sex Differences in Emergency Medical Services Transport Among Hospitalized US Stroke Patients: Analysis of the National Get With The Guidelines-Stroke Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(8):e002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortega AN, Rodriguez HP, Vargas Bustamante A. Policy dilemmas in Latino health care and implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:525–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(9):1284–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asaithambi G, Tong X, Lakshminarayan K, et al. Emergency medical services utilization for acute stroke care: Analysis of the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Program, 2014–2019. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022; 26:326–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canto JG, Zalenski RJ, Ornato JP, Rogers WJ, Kiefe CI, Magid D, Shlipak MG, Frederick PD, Lambrew CG, Littrell KA, Barron HV, & National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Investigators (2002). Use of emergency medical services in acute myocardial infarction and subsequent quality of care: observations from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2. Circulation, 106(24), 3018–3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Concannon TW, Griffith JL, Kent DM, et al. Elapsed time in emergency medical services for patients with cardiac complaints: are some patients at greater risk for delay? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(1):9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durant E, Fahimi J. Factors associated with ambulance use among patients with low-acuity conditions. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(3):329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrlich ME, Han B, Lutz M, et al. Socioeconomic Influence on Emergency Medical Services Utilization for Acute Stroke: Think Nationally, Act Locally. Neurohospitalist. 2021;11(4):317–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans CS, Platts-Mills TF, Fernandez AR, et al. Repeated Emergency Medical Services Use by Older Adults: Analysis of a Comprehensive Statewide Database. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(4):506–515.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman J, Mann NC, Hansen H, et al. Racial/Ethnic, Social, and Geographic Trends in Overdose-Associated Cardiac Arrests Observed by US Emergency Medical Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(8):886–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fussman C, Rafferty AP, Lyon-Callo S, Morgenstern LB, & Reeves MJ (2010). Lack of association between stroke symptom knowledge and intent to call 911: a population-based survey. Stroke, 41(7), 1501–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardener H, Pepe PE, Rundek T, et al. Need to Prioritize Education of the Public Regarding Stroke Symptoms and Faster Activation of the 9–1–1 System: Findings from the Florida-Puerto Rico CReSD Stroke Registry. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(4):439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Govindarajan P, Friedman BT, Delgadillo JQ, et al. Race and sex disparities in prehospital recognition of acute stroke. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(3):264–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanchate AD, Qi D, Stopyra JP, Paasche-Orlow MK, Baker WE, Feldman J. Potential bypassing of nearest emergency department by EMS transports. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(2):300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanchate AD, Paasche-Orlow MK, Baker WE, Lin MY, Banerjee S, Feldman J. Association of Race/Ethnicity With Emergency Department Destination of Emergency Medical Services Transport. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9): e1910816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahn PA, Dhruva SS, Rhee TG, Ross JS. Use of Mechanical Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Devices for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest, 2010–2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10): e1913298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai PH, Lancet EA, Weiden MD, et al. Characteristics Associated With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrests and Resuscitations During the Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic in New York City. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(10):1154–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathews R, Peterson ED, Li S, et al. Use of emergency medical service transport among patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Acute Coronary Treatment Intervention Outcomes Network Registry-Get With The Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124(2):154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melgoza E, Beltrán-Sánchez H, Bustamante AV. Emergency Medical Service Use Among Latinos Aged 50 and Older in California Counties, Except Los Angeles, During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic Period. Front Public Health. 2021; 9:660289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meurer WJ, Levine DA, Kerber KA, et al. Neighborhood Influences on Emergency Medical Services Use for Acute Stroke: A Population-Based Cross-sectional Study. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(3):341–348.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michael GE, Sporer KA, Youngblood GM. Women are less likely than men to receive prehospital analgesia for isolated extremity injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(8):901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mszar R, Mahajan S, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. Association Between Sociodemographic Determinants and Disparities in Stroke Symptom Awareness Among US Young Adults. Stroke. 2020;51(12):3552–3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neil WP, Raman R, Hemmen TM, et al. Association of Hispanic ethnicity with acute ischemic stroke care processes and outcomes. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(1):19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman JD, Davidson KW, Ye S, Shaffer JA, Shimbo D, Muntner P. Gender differences in calls to 9–1–1 during an acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(1):58–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popp LM, Lowell LM, Ashburn NP, Stopyra JP. Adverse events after prehospital nitroglycerin administration in a nationwide registry analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2021; 50:196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pressler SJ, Jung M, Lee CS, et al. Predictors of emergency medical services use by adults with heart failure; 2009–2017. Heart Lung. 2020;49(5):475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reinier K, Sargsyan A, Chugh HS, et al. Evaluation of Sudden Cardiac Arrest by Race/Ethnicity Among Residents of Ventura County, California, 2015–2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7): e2118537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satty T, Ramgopal S, Elmer J, Mosesso VN, Martin-Gill C. EMS responses and non-transports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2021; 42:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seo M, Begley C, Langabeer JR, & DelliFraine JL (2014). Barriers and disparities in emergency medical services 911 calls for stroke symptoms in the United States adult population: 2009 BRFSS Survey. The western journal of emergency medicine, 15(2), 251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah MN, Bazarian JJ, Lerner EB, et al. The epidemiology of emergency medical services use by older adults: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(5):441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith MA, Lisabeth LD, Bonikowski F, Morgenstern LB. The role of ethnicity, sex, and language on delay to hospital arrival for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(5):905–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Springer MV, Labovitz DL, Hochheiser EC. Race-Ethnic Disparities in Hospital Arrival Time after Ischemic Stroke. Ethn Dis. 2017;27(2):125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sterling MR, Echeverria SE, Merlin MA The Effect of Language Congruency on the Out-of-Hospital Management of Chest Pain. World Medical & Health Policy. 2013; 5(2): 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tataris K, Kivlehan S, Govindarajan P. National trends in the utilization of emergency medical services for acute myocardial infarction and stroke. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(7):744–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tataris KL, Mercer MP, Govindarajan P. Prehospital aspirin administration for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the USA: an EMS quality assessment using the NEMSIS 2011 database. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(11):876–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yarris LM, Moreno R, Schmidt TA, Adams AL, Brooks HS. Reasons why patients choose an ambulance and willingness to consider alternatives. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(4):401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young MF, Hern HG, Alter HJ, Barger J, Vahidnia F. Racial differences in receiving morphine among prehospital patients with blunt trauma. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(1):46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zachrison KS, Natsui S, Luan Erfe BM, Mejia NI, Schwamm LH. Language preference does not influence stroke patients’ symptom recognition or emergency care time metrics. Am J Emerg Med. 2021; 40:177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zègre-Hemsey JK, Pickham D, Pelter MM. Electrocardiographic indicators of acute coronary syndrome are more common in patients with ambulance transport compared to those who self-transport to the emergency department journal of electrocardiology. J Electrocardiol. 2016;49(6):944–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zègre-Hemsey JK, Asafu-Adjei J, Fernandez A, Brice J. Characteristics of Prehospital Electrocardiogram Use in North Carolina Using a Novel Linkage of Emergency Medical Services and Emergency Department Data. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(6):772–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deshmukh M, Joseph MA, Verdecias N, Malka ES, LaRosa JH. Acute coronary syndrome: factors affecting time to arrival in a diverse urban setting. J Community Health. 2011;36(6):895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galvan T, Lill S, Garcini LM. Another Brick in the Wall: Healthcare Access Difficulties and Their Implications for Undocumented Latino/a Immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2021;23(5):885–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgenstern LB, Steffen-Batey L, Smith MA, Moyé LA. Barriers to acute stroke therapy and stroke prevention in Mexican Americans. Stroke. 2001;32(6):1360–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Emergency Medical Services Information System 2020 User Manual. 2021. https://nemsis.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/2020-NEMSIS-RDS-340-User-Manual_v3-FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1: Specific characteristics of the included individual studies that assess Hispanic adults’ experiences with the emergency medical services (EMS) system in the United States between 2000 and 2021