SUMMARY

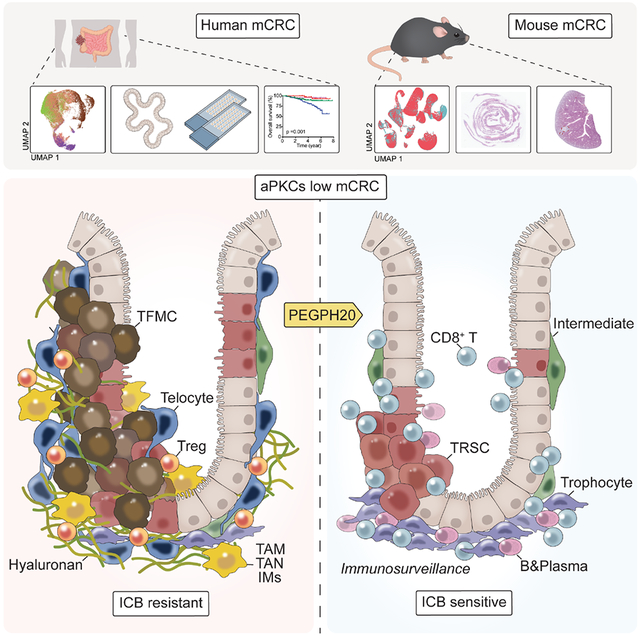

Mesenchymal colorectal cancer (mCRC) is microsatellite stable (MSS), highly desmoplastic, with CD8+ T cells excluded to the stromal periphery, resistant to immunotherapy, and is driven by low levels of the atypical PKCs (aPKCs) in the intestinal epithelium. We show here that a salient feature of these tumors is the accumulation of hyaluronan (HA), which along with reduced aPKC levels, predict poor survival. HA promotes epithelial heterogeneity and the emergence of a tumor fetal metaplastic cell population (TFMC) endowed with invasive cancer features through a network of interactions with activated fibroblasts. TFMCs are sensitive to HA deposition, and their metaplastic markers have prognostic value. We demonstrate that in vivo HA degradation with a clinical dose of hyaluronidase impairs mCRC tumorigenesis and liver metastasis and enables immune checkpoint blockade therapy by promoting the recruitment of B and CD8+ T cells, including a proportion with resident memory features, and blocking immunosuppression.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC

Mesenchymal colorectal cancer (mCRC) is a poor prognosis, highly desmoplastic, and immune-excluded tumor. Martinez-Ordoñez et al. demonstrate that the synthesis of hyaluronan driven by a deficiency in the atypical PKCs in epithelial cells is a critical event in mCRC by promoting stroma crosstalks with invasive fetal metaplastic cells and immunosuppression.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major cause of cancer mortality worldwide.1 Despite improvements in systemic treatment, the metastatic disease shows a dismal 5-year survival rate of only 12%-14%.2 CRCs can develop from any region of the colon or the rectum. However, it has become increasingly clear that primary tumor locations show distinct pathophysiological and clinical characteristics.3,4 Thus, in the distal (left-sided) colon, tumors typically initiate from tubular adenomas, whereas in the proximal (right-sided) colon, tumors initiate from sessile serrated lesions (SSL). These SSL-derived proximal CRCs can evolve through a transcriptional pathway termed consensus molecular subtype (CMS) 1, are often associated with BRAF mutations, are characterized by microsatellite instability (MSI-H) with a CpG island methylator phenotype, are immune active, present with a good prognosis, and are relatively sensitive to immune checkpoint blockade therapy (ICB).5,6 In contrast, distal CRCs are microsatellite stable (MSS), often chromosomal instable, belonging to the CMS2/3 transcriptional category, are initiated by mutations in APC, TP53, KRAS, and the TGFβ pathway, have an intermediate prognosis, and account for about 50% of all CRCs.7,8 The transcriptional classification of CRC tumors also revealed a CMS4-enriched subtype, which accounts for about 35% of all CRCs and displays the highest risk of distant relapse and the worst prognosis.9,10 CMS4 tumors could evolve from SSL or tubular adenomas, are MSS, and resistant to ICB therapy.11 In contrast to CMS2/3 tumors, which are immunologically deserted, CMS4 tumors are immune excluded with CD8+ T cells accumulating in the stromal periphery and absent in the cancer epithelial core.12-14

Other distinctive features of the CMS4-enriched tumors are their high content in activated cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and the acquisition of a mesenchymal phenotype that predicts adverse outcomes in CRC patients better than the presence of prevalent mutations.7,9,11 This agrees with the increasingly accepted notion that an activated desmoplastic stroma drives the resistance of CRC cells to conventional and targeted therapies.15 However, the molecular and cellular mechanisms that drive mesenchymal tumorigenesis are still far from clear. Given the relatively scarce information on the fundamental players controlling the development of this type of intestinal tumor, it is critical to find upstream regulators of these pathways beyond the known mutated tumor suppressors and oncogenes already identified in cancers from CMS2/3 distal tubular lesions or CMS1 proximal SSL. In this regard, we have recently reported that low levels of the atypical PKCs (aPKCs; PKCζ and PKCλ/ι) are drivers for the initiation and progression of mesenchymal CRC (mCRC), as well as for their resistance to ICB.13,16 Thus, the simultaneous inactivation of both aPKCs in the mouse intestinal epithelium results in the spontaneous generation of aggressive MSS mesenchymal intestinal tumors with serrated and signet ring carcinoma features and a reactive desmoplastic and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME).13,15 aPKC-deficient tumors excluded CD8+ T cells to the stromal periphery but were infiltrated with myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) expressing PD-L1 but were resistant to anti-PD-L1 treatment.13

Because mCRC tumors are populated by CAFs and enriched in a TGFβ signaling gene expression signature, several studies explored the possibility of treating these tumors by inhibiting TGFβ function. Surprisingly, this approach is not sufficient to reduce the tumor load or to reactivate the immune system, although it decreases the desmoplastic reaction and enables response to anti-PD-L1 therapy.13,17,18 Therefore, it could be argued that targeting CAFs, while inefficient as monotherapy, at least at the TGFβ level, might be a potential venue to promote immunotherapy in mCRC. However, the design of therapeutics aimed at selectively de-reprograming CAFs is extremely challenging due to the heterogeneity of the stromal fibroblasts in several cancers, including CRC, and a limited understanding of the master regulators of the different CAF subtypes.

The difficulty of targeting CAFs impelled the search for alternative ways to modulate the tumor stroma. Thus, several laboratories have focused their interest on targeting not the cellular components but different molecules of the TME extracellular matrix, like collagens and the glycosaminoglycan hyaluronan (HA).19-22 The rationale behind this approach is that reducing the extracellular matrix barrier purportedly protecting the tumor would result in better access to chemotherapeutics and ICB treatments. However, genetically targeting collagen I, the major fibrillar collagen type, in αSMA+ pancreatic and intestinal CAFs does not reduce but enhances tumor growth by either decreasing the barrier effect, which allows the tumor to expand free of its stromal boundaries, or by promoting the recruitment of MDSCs, which stimulates a TME conducive to immunosuppression and enhanced tumorigenesis.23,24 Therefore, a better understanding of the mesenchymal TME ecosystem will unveil the mechanistic cross-talks that define their malignancy and resistance to immunotherapy, leading to the identification of vulnerabilities to be exploited therapeutically.

Here we report a detailed characterization of the epithelial compartment and microenvironment of mCRC and its response to HA-depleting treatment.

RESULTS

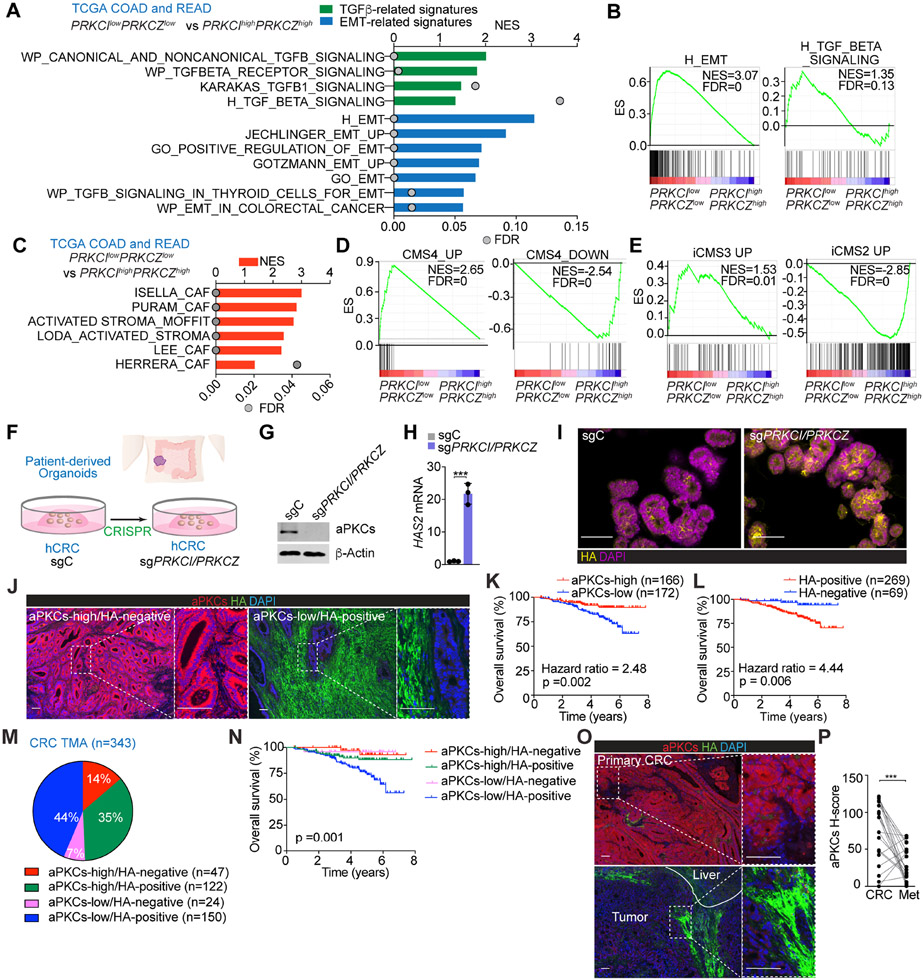

Reduced expression of both aPKCs in human CRC correlates with a mesenchymal phenotype

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of the CRC dataset in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) demonstrated that the transcriptome of patients with low aPKC levels (PRKCIlowPRKCZlow) was enriched in transcripts corresponding to the mesenchymal phenotype, including an activated stroma and CAF signatures, as compared to patients with high aPKC levels (PRKCIhighPRKCZhigh) (Figures 1A-1C). Stratification of TCGA patients by CMS subtypes using the CMScaller algorithm revealed that the CMS4 transcriptomic phenotype was predominant in the PRKCIlowPRKCZlow group (Figures 1D and S1A). Likewise, analysis by the recently proposed iCMS classification, based on intrinsic epithelial gene expression, demonstrated significant enrichment of PRKCIlowPRKCZlow patients in the iCMS3 subtype (Figures 1E and S1B). The PRKCIlowPRKCZlow group had a higher monocytic-myeloid abundance and an augmented expression of endothelial and activated fibroblastic signatures as compared to that of the PRKCIhighPRKCZhigh cohort, as determined by the Microenvironment Cell Populations (MCP)-counter algorithm (Figure S1C). These results demonstrated that CRC patients with low aPKC levels have a tumor microenvironment that is inflamed, highly vascularized, and rich in activated CAFs, all characteristics of the mCRC type.

Figure 1. aPKC-low levels correlate with HA-deposition and poor prognosis in human CRC.

(A) GSEA of transcriptomic data from TCGA CRC patients according to PRKCI/PRKCZ expression.

(B) GSEA plots of the indicated gene signatures from TCGA CRC patients according to PRKCI/PRKCZ expression.

(C) GSEA of transcriptomic data from TCGA CRC patients according to PRKCI/PRKCZ expression using stroma-related signatures.

(D and E) GSEA plots of the indicated gene signatures in TCGA CRC patients according to PRKCI/PRKCZ expression.

(F) Experimental design of PRKCI and PRKCZ editing in patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from CRC.

(G) Immunoblot of indicated proteins in sgPRKCI/PRKCZ and sgC PDOs (n=3 biological replicates).

(H) qPCR of HAS2 in sgPRKCI/PRKCZ and sgC PDOs. Unpaired t-test. Data shown as mean ± SEM (n=3 biological replicates). ***p < 0.001.

(I) Immunofluorescence (IF) for HA (yellow) in sgPRKCI/PRKCZ and sgC PDOs. Scale bars, 50 μm

(J) IF for aPKCs (red) and HA (green) in a human cohort of CRC samples (n=390). Scale bars, 100 μm.

(K and L) Kaplan-Meier curve for overall survival of CRC patients according to aPKCs (K) and HA (L) expression. Log-rank tests.

(M and N) Pie chart of relative distribution of CRC patients according to aPKCs/HA expression (M) and Kaplan-Meier curve for overall survival. Log-rank test (N).

(O and P) IF for aPKCs (red) and HA (green) (O) and quantification (P) in primary CRC samples and metastatic counterparts (n=21, paired). Paired t-test. ***p < 0.001. Scale bars, 100 μm.

See also Figure S1.

Low aPKC levels in CRC patients are associated with increased expression of markers of hyaluronan synthesis

The analysis of the differentially expressed genes in PRKCIlowPRKCZlow vs. PRKCIhighPRKCZhigh groups in several large datasets identified hyaluronan synthase 1 (HAS1) and 2 (HAS2) as two upregulated genes in PRKCIlowPRKCZlow patients (Figures S1D and S1E), suggesting that aPKC-deficient tumors would potentially be enriched in HA. Deletion of both aPKC genes in a human CRC patient-derived organoid showed higher levels of HAS2 and increased accumulation of HA (Figures 1F-1I), demonstrating that aPKC deficiency is sufficient to trigger the HA biosynthetic pathway in a cell-autonomous manner. Consistently, the classification of CRC patients based on a HAS score according to their HAS1, HAS2, and HAS3 levels showed a negative correlation with aPKC levels and a positive enrichment in TGFβ signaling and EMT signatures in CRC patients with a high HAS score, as compared to those with a low HAS score (Figures S1F and S1G). These findings support the notion that increased HA levels are a feature of human mCRC tumors.

Next, we analyzed the expression levels of aPKC in the tumor epithelium and HA deposition in the stroma by double immunofluorescence of a large cohort of surgically resected CRC specimens (Figure 1J). Among the 390 CRC patients in the tissue microarray (TMA), 343 with available clinical information were stratified according to aPKC/HA expression status, including 21 Stage IV patients with matched liver metastasis (Figure S1H). Kaplan-Meier curves revealed that patients with aPKC-low expression showed significantly worse overall survival than those with aPKC-high levels (Figure 1K). HA-positive patients also showed a worse prognosis than HA-negative patients (Figure 1L). Multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that low aPKC expression was correlated with HA stromal deposition independent of other pathological features (Figures S1I and S1J). Survival analyses of these patients categorized into four groups based on their aPKC and HA content indicated that those who were aPKC-low and HA-positive had the worst prognosis (Figures 1M and 1N). Consistently, multivariate COX proportional hazards regression analysis demonstrated that aPKC-low/HA-positive expression was significantly associated with worse prognosis compared to aPKC high/HA-positive patients (Hazard ratio: 2.40), whereas there was no significant difference between aPKC high/HA positive patients and aPKC high/HA negative or aPKC low/HA negative patients (Figure S1K). These findings highlight HA deposition as one of the main contributors to the aggressive phenotype of aPKC-deficient tumors. All stage IV CRC patients and their matched liver metastasis studied were HA-positive, and liver metastases showed reduced expression of aPKC compared to their matched primary tumors (Figures 1O and 1P), suggesting that the loss of both aPKCs is an important event for the systemic spread of late-stage CRC.

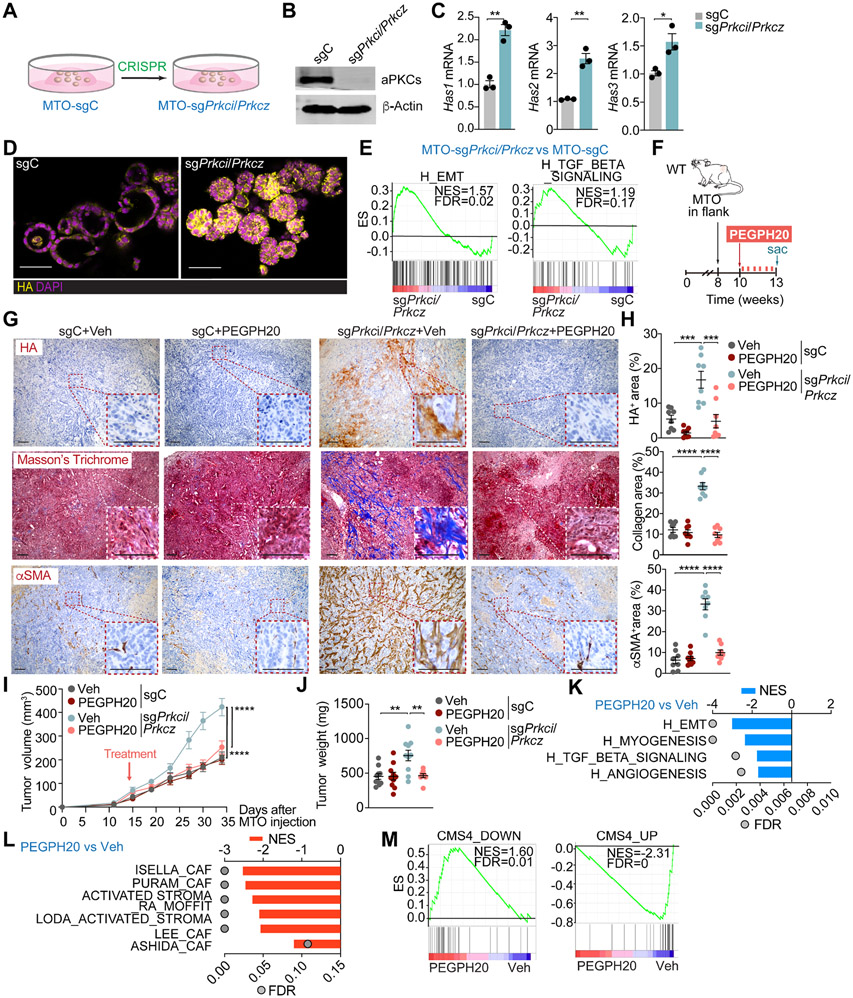

aPKC deletion makes CRC tumors dependent on HA for enhanced malignancy

To address the potential role of HA stromal accumulation in the tumorigenesis of intestinal mesenchymal tumors in vivo, we first characterized mouse tumor organoids (MTO) with mutations in Ape, Trp53, Kras, and Tgfbr217 and with deletion of Prkci and Prkcz by CRISPR-Cas9. MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz recapitulated the observed phenotype in human organoids showing in vitro upregulation of Has1, Has2, and Has3 transcripts, increased expression of HA, enrichment in EMT and TGFβ signaling signatures, and the iCMS3 patients’ epithelial signature together with a decreased expression of the iCMS2 patients' signature (Figures 2A-2E and S2A). The injection of MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz into the colon submucosa of C57BL/6J mice generated larger tumors and displayed increased HA accumulation than MTO controls (Figures S2B-S2F). Next, we tested the impact of depleting HA on tumorigenesis. MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz or MTO-sgC (control) were subcutaneously transplanted into syngeneic C57BL/6J mice and treated with a low dose of clinical-grade pegylated hyaluronidase (PEGPH20; 0.0375 mg/Kg), equivalent to a human dose evaluated in clinical trials, or with vehicle (Figure 2F). Tumors from MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz had a more desmoplastic phenotype characterized by enhanced expression of HA, collagen, and αSMA+, which was reverted by PEGPH20 treatment (Figures 2G and 2H). MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz tumors showed higher volume and weight than those from MTO-sgC but were sensitive to PEGPH20 treatment, which did not affect the growth properties of MTO-sgC tumors (Figures 2I and 2J). Consistently, transcriptomic interrogation of MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz tumors treated with PEGPH20 revealed a decrease in signatures related to invasion, tumor progression, and desmoplasia, such as EMT, myogenesis, angiogenesis, TGFβ signaling, stromal activation and the CMS4 subtype (Figures 2K-2M). These data demonstrate that aPKC-deficiency switches CRC tumors to a highly mesenchymal phenotype yet confers vulnerability to HA depletion in the context of WNT-driven tumorigenesis.

Figure 2. Targeting HA disrupts the desmoplastic response and impairs mesenchymal tumorigenesis.

(A) Experimental design of Prkci and Prkcz editing in mouse tumor organoids (MTO).

(B) Immunoblot analysis of indicated proteins in MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz and MTO-sgC (n=3 biological replicates).

(C) qPCR of indicated genes in MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz and MTO-sgC (n=3 biological replicates). Unpaired t-test. Data shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p< 0.01.

(D) IF for HA (yellow) in MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz and MTO-sgC. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(E) GSEA plots of the indicated gene set signatures for MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz versus MTO-sgC (n=3 biological replicates).

(F-J) Subcutaneous injection of MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz and MTO-sgC in WT mice. Mice were treated twice a week with Veh or PEGPH20 0.0375 mg/kg for 3 weeks (MTO: sgC Veh n=10, sgC PEGPH20-treated n=10, sgPrkci/Prkcz Veh n=10, and sgPrkci/Prkcz PEGPH20-treated n=8). Experimental design (F); Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for HA, Masson’s trichrome, and αSMA staining (G); quantification, one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, (n=8), ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (H); tumor volume, two-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, ****p < 0.0001 (I) and tumor weight, one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, **p< 0.01 (J). Scale bars, 100 μm. Sac: sacrificed.

(K and L) GSEA from Quant-seq on MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz PEGPH20-treated tumors (n=4) versus Veh (n=3) using compilation H (MSigDB) (K) and stroma-related signatures (L).

(M) GSEA plots of the indicated gene signatures for MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz PEGPH20-treated tumors (n=4) versus Veh (n=3).

See also Figure S2.

HA accumulation is a critical feature of serrated mesenchymal tumors

To test whether HA is also important in serrated-originating CRC, we used an endogenous model of mesenchymal serrated MSS tumors driven by aPKC deficiency.13 Upon the inducible and simultaneous ablation of both aPKCs, organoids from inducible Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-CreER mice showed increased expression of Has1, Has2, and Has3, concomitant with enhanced HA accumulation (Figures 3A-3C). Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre intestinal tissues showed a substantial deposition of HA compared to control samples (Figure 3D). The accumulation of stromal HA was detected even in the non-tumor area of the Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre intestine and further increased in adenomas as they progressed from benign SSL to malignant carcinomas (Figure 3D). The stromal HA accumulation in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors was eliminated by PEGPH20 treatment, accompanied by a profound remodeling of the tumor stroma, as evidenced by reduced collagen deposition and αSMA expression (Figures 3E-3G). PEGH20 treatment resulted in a significant reduction in tumor number, average size, and tumor load and lower cancer incidence in the small intestine, concomitant with fewer SSL and reduced invasive carcinomas (Figures 3H-3K, S3A, and S3B). As reported previously, this mouse model also gives rise to aggressive desmoplastic tumors in the proximal colon.13 PEGPH20 treatment reduced colon tumorigenesis in this mouse model together with stroma remodeling (Figures S3C-S3G). In keeping with these histological observations, GSEA of transcriptomic profiling of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors revealed that PEGPH20 treatment resulted in a decrease in signatures related to invasion and tumor progression as well as those corresponding to stromal activation, serrated tumorigenesis and the CMS4 subtype (Figures 3L-3O).

Figure 3. Targeting HA represses mesenchymal intestinal CRC.

(A) Experimental design for tamoxifen treatment in organoids from Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-CreER mice.

(B) qPCR of indicated genes in tamoxifen- or Veh-treated organoids (n= 3 biological replicates). Unpaired t-test. Data shown as mean ± SEM. **p< 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

(C) IF for HA (yellow) of Veh****- or tamoxifen-treated organoids. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(D) IHC for HA of small intestinal sections from Prkcif/fPrkczf/f and Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre mice. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(E-K) Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre mice (male and female, 11-week-old) treated with Veh (n=10) or PEGPH20 (n=12), 0.0375 mg/kg for 3 weeks. Experimental design (E); IHC HA, Masson’s trichrome, and αSMA (F); staining quantification, unpaired t-test, data shown as mean ± SEM (n=5), **p< 0.01 (G); macroscopic images of small intestinal tumors (H); total tumor number, tumor size, and tumor load in small intestine, unpaired t-test and Mann-Whitney test, data shown as mean ± SEM, **p< 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (I); quantification of cancer incidence, chi-square, *p < 0.05 (J); and sessile serrated lesions (SSL) and carcinoma quantification of tumors, Mann-Whitney test, data shown as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p< 0.01 (K). Scale bars, 50 μm (F), 10 mm (H). The red arrow denotes tumors >5mm (H). Sac: sacrificed.

(L-N) GSEA of transcriptomic data from Quant-seq on PEGPH20-treated tumors versus Veh (n=3) using compilation H (MSigDB) (L), stroma-related signatures (M) and serrated-related signatures (N).

(O) GSEA plots of the indicated gene signatures for PEGPH20-treated tumors versus Veh (n=3).

See also Figure S3.

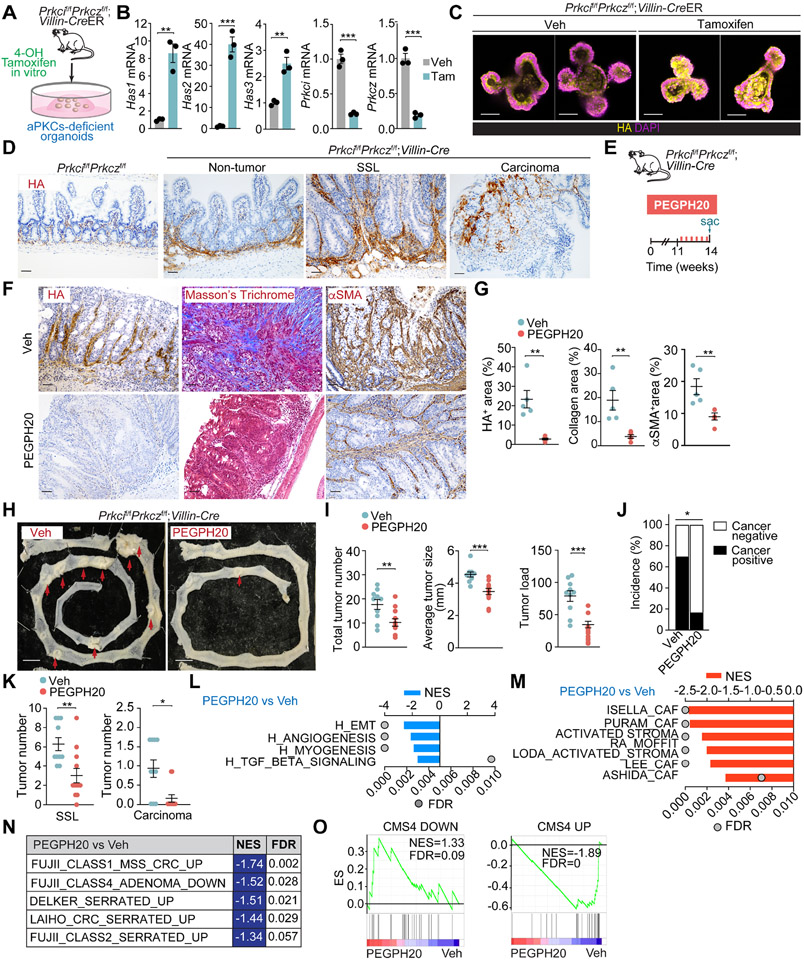

Anti-angiogenic effect of PEGPH20 on the vasculature of mCRC tumors

To define the mesenchymal phenotype at a cellular level and to understand how the extracellular accumulation of HA promotes tumorigenesis and informs the microenvironment in this type of neoplasia, we carried out a scRNA-seq analysis of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors from mice treated or not with PEGPH20 (Figures 4A and 4B). Unsupervised clustering with selective markers for each population identified epithelial, stromal, and immune cells (Figures 4C and S4A-S4I). Stromal cell re-clustering and mapping of marker gene expression identified six major stromal cell types, including endothelium (Pecam1), lymphatic-endothelial cells (Lyve1), smooth muscle cells (Myh11), fibroblasts (Dcn), glial cells (Plp1), and pericytes (Rgs5) (Figures 4D, 4E, S4J and S4K). Endothelial cells were the most abundant cell population in the stroma of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors (Figures 4E-4F). Analysis of the endothelial cell compartment of Pecam1+ (CD31) and Lyve1+ cells identified nine cell types (Figures 4G, 4H, S4L, and S4M), which were ascribed to the following categories: capillary (Cd36), artery (Gja4), vein (Ackr1), tip (Apln), immature (Aplnr), postcapillary (Selp), lymphatic-endothelial (Lyve1), shear-stress artery (Pi16) and proliferative (Birc5) (Figures S4L and S4M). Previous scRNAseq efforts identified tip and proliferative endothelial cells as specially enriched in the tumor endothelial cell (TEC) population, which have been proposed to be involved in tumor neo-angiogenesis.25,26 To rigorously distinguish the clusters corresponding to normal endothelial cells (NEC) from the TEC in the Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors, we created a TEC-specific signature by comparing tumor vs. normal endothelium from a human CRC scRNAseq dataset (GSE132465). This signature labeled Tip, Postcapillary, and Proliferating cells as TEC (Figures S4N and S4O). Also, gene signatures from lung endothelial cells supported that capillary and immature cells belong to the TEC category (Figures S4N and S4O). PEGPH20 reduced the proportion of tip cells and postcapillary and immature cells in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors (Figures 4H and 4I).

Figure 4. Remodeling of the mesenchymal intestinal tumor stroma by PEGPH20 treatment.

(A) Experimental design and workflow of scRNAseq. Small intestinal tumors from Veh (n=5) and PEGPH20-treated mice (n=3) were dissected and digested into single-cell suspensions for sequencing.

(B and C) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of tumor cells colored by treatment (B) and by the major cellular compartments (C).

(D and E) UMAP of stromal cells colored by treatment (D) and by the major stromal cell type (E).

(F) Stromal-cell-type percentage relative to the total stromal cells count per treatment.

(G and H) UMAP of endothelial cells colored by treatment (G) and by endothelial cell type (H).

(I) Endothelial-cell-type percentage relative to the total stromal cells count per treatment.

(J and K) UMAP of fibroblast colored by treatment (J) and by fibroblast cell type (K).

(L) Violin plots for the indicated gene signatures in the fibroblast cell types. The top and bottom of the violin plots represent the minimal and maximal values, and the width is based on the kernel density estimate of the data, scaled to have the same width for all clusters. Horizontal lines represent median values. Unpaired t-test, **p< 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

(M and N) UMAP of fibroblast colored by fibroblast cell type (M) and fibroblast-cell-type percentage relative to the total fibroblast count per treatment (N).

(O) Significantly enriched extracellular matrix (ECM)-related signatures in intermediate fibroblast treated with PEGPH20 versus Veh.

(P and Q) PDGFRα staining (red) with NRG1 (green) and panCK (white), CD34 staining (green) with PDFGRα (red) and CD31 (white) (P), and quantification, unpaired t-test, data shown as mean ± SEM, **p< 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 (Q) in Veh- and PEGPH20-treated small intestine tumors (n=5).

(R and S) PDGFRα staining (red) with NRG1 (green) and panCK (white), CD34 staining (green) with PDFGRα (red) and CD31 (white) (R), and quantification, unpaired t-test and Mann-Whitney test, data shown as mean ± SEM, **p< 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 (S) in Veh- and PEGPH20-treated colon tumors (n=3). Scale bars, 100 μm.

See also Figures S4 and S5.

Next, we applied two gene signatures reflecting the transcriptional programs of tumor vessel disorganization and normalization, respectively.25 The whole endothelial compartment of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors were enriched in the vessel disorganization signature, which was reversed upon PEGPH20 treatment, indicating that high HA deposition in mesenchymal tumors promotes endothelial remodeling (Figure S4P). PEGPH20 also increased the normalization signature (Figure S4P), demonstrating that HA depletion not only pruned the TECs but also normalized the endothelial landscape of the Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors. Further pathway analysis of the endothelium compartment of these tumors showed that PEGPH20 reduced angiogenesis, glycolysis, and hypoxia signatures (Figure S4P). In contrast, it increased the expression of signatures related to interferon (IFN) activation (Figure S4P), suggesting enhanced immunosurveillance mechanisms driven by reprogramming endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature. No changes were observed in pericyte coverage (Figures S4Q and S4R). These results demonstrate that the remodeling of the tumor endothelial vasculature is a hallmark of the high efficacy of PEGPH20 in reducing tumorigenesis.

Fibroblast heterogeneity in endogenous mesenchymal tumors

The analysis of the fibroblast compartment by re-clustering the Dcn-expressing cells identified three cell categories (Figures 4J and 4K). Previous studies classified normal intestinal fibroblasts into three cell lineages according to the expression of Pdgfra, Cd81, and Cd34. This determines a dual and compartmentalized fibroblast positioning along the crypt axis and their biological function in intestinal homeostasis.27 Thus, Pdgfrahigh fibroblasts (telocytes) are abundant in the villus region, expressing high levels of BMP ligands necessary for terminal epithelial cell differentiation.28 Conversely, PdgfralowCd81high fibroblasts (trophocytes) are CD34+, are exclusively located beneath the crypts, and express WNT pathway factors, including RSPO1 and RSPO3, all critical for adult stem cell maintenance.29,30 In line with this classification, we identified telocytes and trophocytes as components of the fibroblast compartment of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors (Figures 4K, S5A-S5H). We also found that these tumors were enriched in a third fibroblast population (“intermediate”) that shares some trophocyte features, such as the expression of WNT modulators and BMP inhibitors, but also resembles telocytes in that are negative for CD81 and CD34, yet express PDGFRα, albeit at a lower level than telocytes (Figures 4K, S5A-S5H). Telocytes and intermediate fibroblasts showed enrichment of carcinoma-associated fibroblast (CAF) signatures (Figure 4L). CAFs have been previously described as inflammatory (iCAFs) or myofibroblastic (myCAFs), which are strongly activated by TGFβ.31-33 Telocytes showed higher myCAF signature expression and TGFβ response than intermediate or trophocytes (Figure 4L and S5H). Conversely, trophocytes showed a higher expression of an iCAF signature than the intermediate or the telocytes (Figure 4L and S5I-S5K). Telocytes from Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors express high levels of Sfrp2 and Sfrp4 (Figure S5F), critical targets of SOX2 expression in CAFs, to promote the CRC mesenchymal phenotype.12 Consistently, telocytes in these tumors displayed high expression of SOX2 targets (Figure 4L), suggesting that telocytes/myCAFs are activated and expanded through the TGFβ/SOX2 axis to drive the progression of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors.

HA degradation remodels the mCRC CAF compartment

HA degradation in vivo virtually eliminated the telocyte population, the main CAF in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors, and promoted the concomitant accumulation of trophocytes (Figures 4M and 4N). In contrast, the proportion of intermediate fibroblast was not affected by PEGPH20 treatment (Figures 4M and 4N). However, differential gene expression analysis showed a substantial reduction in collagens, matrix metalloproteinases, and signatures related to matrix remodeling in the intermediate fibroblasts from PEGPH20-treated mice (Figures 4O, S5K, and S5L), suggesting that the HA-rich environment is fundamental for the selective maintenance of telocytes and myCAF features. These findings were further validated by multiplex immunofluorescence. Staining of NRG1 (activated telocytes), PDGFRα (telocytes), Pan-CK (epithelial cells), and DAPI (nuclear marker) showed a strong presence of PDGFRα+/NRG1+ fibroblasts at the luminal border of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors, consistent with the zonation pattern of telocytes in the normal small intestinal and colonic epithelium, that was significantly reduced by PEGPH20 treatment (Figures 4P-4S). Trophocytes identified as a PDGRα−/CD31−/CD34+ population and normally located beneath the crypts in the normal intestinal epithelium showed a broader distribution in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors (Figures 4P-4S). PEGPH20 strongly increased trophocyte levels mainly at the crypt-bottom positions (Figures 4P-4S), which suggests a complete remodeling of the trophocyte population upon HA depletion.

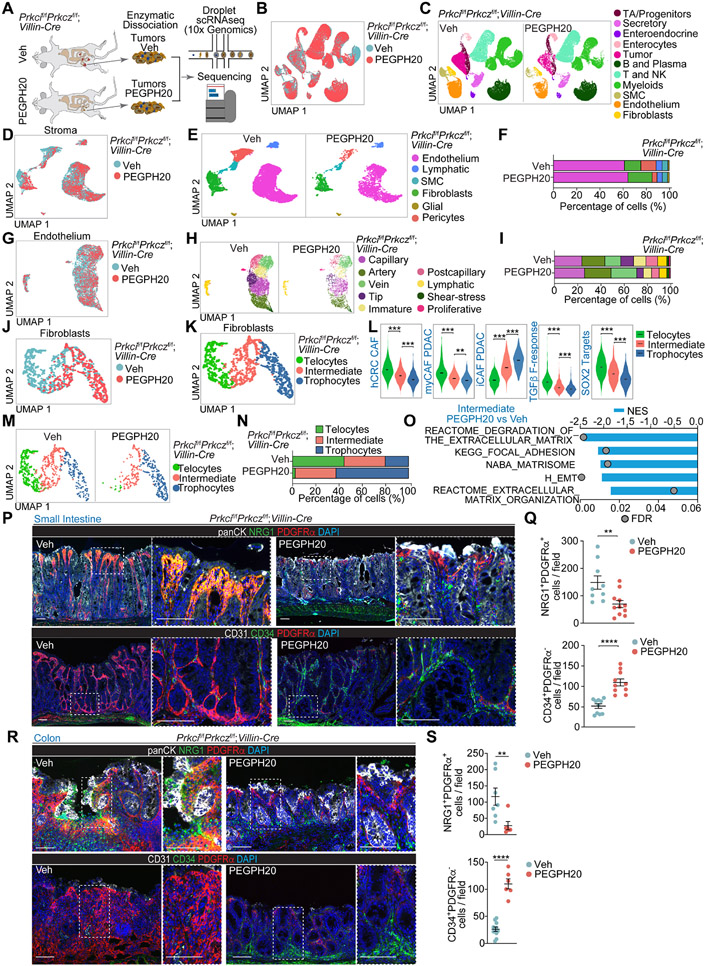

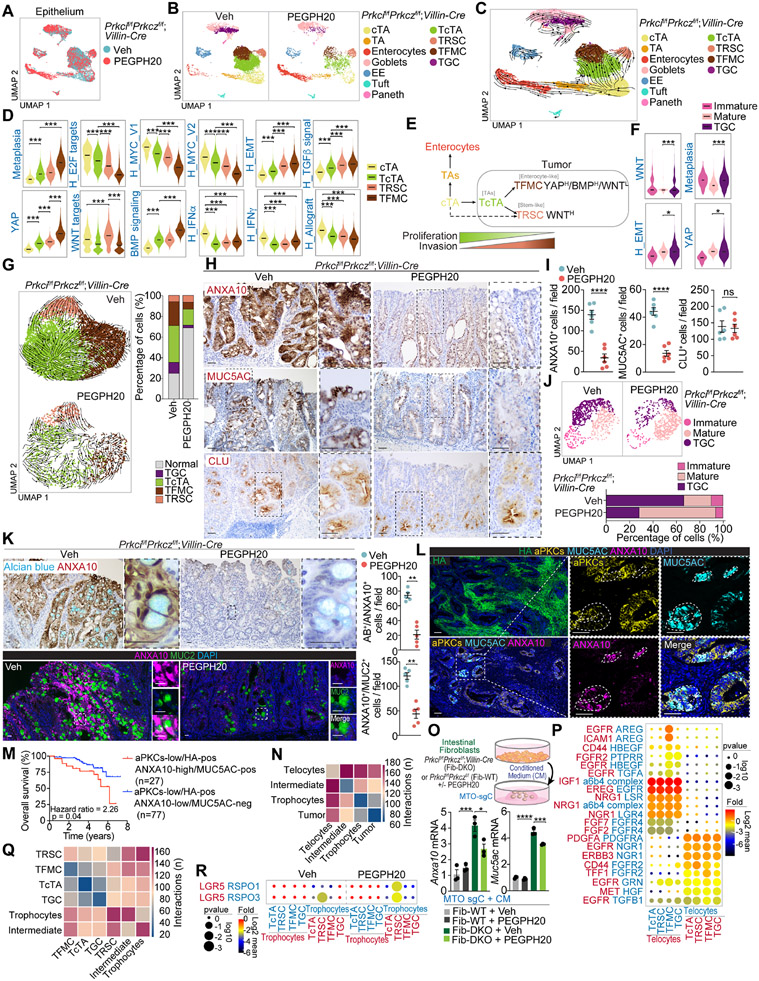

Epithelial cancer cell hierarchical heterogeneity and dependency on HA in mCRC tumors

We next investigated whether HA depletion modulates the epithelial features of mesenchymal intestinal tumors. Epithelial cell re-clustering and mapping of the scRNAseq data from Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors using marker gene expression classified the non-tumor epithelial cell population of these samples as non-cycling transient amplifying (TA), cycling transient amplifying (cTA), enterocytes, goblet, Paneth, tuft, and enteroendocrine (Figures 5A, 5B, and S6A-S6C). Based on sample origin and genome-wide copy-number alteration (CNA) analysis, we classified epithelial cells as malignant or non-malignant (Figures S6D-S6F). We identified four tumor epithelial populations (Figure S6G). One of the clusters corresponds to the tumor counterpart of the cycling TA population (TcTA) (Figures 5B, S6G-S6K), which shares similarities with a recently identified cancer cell population seemingly essential for LGR5-independent tumor growth.34 Another cluster was enriched in Ly6a and Anxa10, markers of a previously reported fetal metaplastic cell (tumor fetal metaplastic cells; TFMC) (Figures 5B, S6G-S6K).35,36 A third tumor cell population was characterized by high expression of clusterin and is reminiscent of the “revival stem cell” (tumor revival stem cells; TRSC) that emerges in response to intestinal tissue damage associated with the loss of LGR5+ stem cells and activation of regenerative processes in non-tumor intestinal tissues (Figures 5B, S6G-S6K).37 A fourth cancer cell type corresponded to transformed goblet cells (TGC) and displayed some features of immature goblet cells with high levels of Ly6a, and Anxa10, a transcriptional profile characteristic of the TFMCs found in the non-goblet epithelial tumor cell compartment (Figures 5B, S6L-S6N).

Figure 5. scRNA-seq reveals a complex heterogeneity and hierarchy maintained by HA in tumor epithelial cells.

(A and B) UMAP of epithelial cells colored by treatment (A) and by epithelial cell type (B).

(C) RNA velocities visualized on the UMAP projection in (B).

(D) Violin plots for the indicated gene signatures in cycling transient amplifying (cTAs), tumor cTAs (TcTAs), tumor revival stem cells (TRSCs), and tumor fetal metaplastic cells (TFMCs). The top and bottom of the violin plots represent the minimal and maximal values, and the width is based on the kernel density estimate of the data, scaled to have the same width for all clusters. Horizontal lines represent median values. Unpaired t-test. ***p < 0.001.

(E) Scheme showing that cTAs can differentiate to TcTA and conserve epithelial cancer cell hierarchical heterogeneity.

(F) Violin plots for the indicated gene signatures in immature goblet cells, mature goblet cells, and tumor goblet cells (TGC). The top and bottom of the violin plots represent the minimal and maximal values, and the width is based on the kernel density estimate of the data, scaled to have the same width for all clusters. Horizontal lines represent median values. Unpaired t-test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

(G) RNA velocities in tumor epithelial cells for each treatment and tumor-cell-type percentage relative to the total tumoral cells count per treatment.

(H and I) IHC for ANXA10, MUC5AC and CLU (H), and quantification, unpaired t-test, data shown as mean ± SEM, ****p < 0.0001 (I) in PEGPH20-treated tumors (n=5). Scale bars, 50 μm. ns: not significant.

(J) UMAP of goblet cells colored by goblet cell type and goblet-cell-type percentage relative to the total goblet cells count per treatment.

(K) IHC for ANXA10 with alcian blue, IF for ANXA10 (magenta) and MUC2 (green), and quantification in Veh- and PEGPH20-treated tumors (n=5). Mann-Whitney test, data shown as mean ± SEM, **p < 0.01. Scale bars, 25 μm.

(L) IF for HA (green), aPKCs (yellow), MUC5AC (cyan), and ANXA10 (magenta) in Veh- and PEGPH20-treated tumors (n=5). Scale bars, 100 μm.

(M) Kaplan-Meier curve for 8-year overall survival of TCGA CRC patients according to aPKCs/HA/ANXA10/MUC5AC expression. Log-rank test.

(N) CellphoneDB analysis of the number of ligand-receptor interactions between tumor epithelial cells and fibroblast.

(O) Anxa10 and Muc5ac mRNA levels of MTO-sgC stimulated by conditioned medium (CM) of indicated intestinal fibroblasts with or without PEGPH20 (2.5 μg/ml) for 3 days (n=3). Schematic representation and qPCR. One-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(P) Dot plot for ligand-receptor pairs of growth factors between telocytes and tumor epithelial in Veh-treated tumors.

(Q and R) CellphoneDB analysis of the number of ligand-receptor interactions between tumor epithelial cells and fibroblast cell types (Q) and dot plot for ligand-receptor pairs of Lgr5 and Rspo co-factors between trophocyte and tumor epithelial in Veh- and PEGPH20-treated tumors (R).

See also Figures S6 and S7.

Trajectory analysis by RNA velocity established a flow from cTAs to TcTAs, which gives rise to TFMCs and TRSCs albeit some of the latter might originate directly from cTAs (Figure 5C). Transcriptomic comparison of tumor and normal intestinal epithelial cells shows that TcTAs are related to non-tumor cTAs, whereas TFMCs are more differentiated and related to enterocytes (Figures S6J). Although there is an increased expression of a BMP signaling signature in the three epithelial cell transformed populations, as compared to cTA, TFMC showed the highest BMP signaling activation while displaying reduced WNT signaling, which was maintained/enhanced in the TRSC population (Figure 5D). These data demonstrate that TFMCs are the most differentiated transformed cell populations and have features compatible with enterocyte markers (Figure S6J). The TFMC compartment is enriched in a “metaplasia” gene expression signature (Figure 5D). This is consistent with recent observations that human serrated tumors are associated with a metaplastic response whereby enterocytes acquire a fetal-gastric lineage as a cell protection mechanism against a chronic cytotoxic response.35 In our model, toxicity is most likely triggered by constitutive inflammation driven by increased epithelial apoptosis and dysfunctional Paneth cells that promote tumor initiation,13,14,38 which explains why there is a TRSC compartment in these tumors. This scenario accounts for the SSL histology characteristic of the Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre adenomas, which are the precursors of the serrated carcinomas.35

Selective signaling phenotypes of mesenchymal tumor cells are maintained by stromal HA accumulation

From the signaling point of view, TcTAs are less enriched in proliferative signatures, such as “E2F_TARGETS” or “MYC_TARGETS,” than cTAs, yet these signatures were more enriched in TcTAs than in TFMC or TRSC (Figure 5D). This indicates that tumor cells are less proliferative than non-tumor cTA cells and become even less proliferative as they differentiate towards the TFMC and TRSC compartments. There is also a progressive upregulation of the EMT and TGFβ gene expression signatures going from cTAs to TcTAs, and from these to TFMC, consistent with aPKC-deficient tumor epithelial cells being more invasive yet less proliferative, with TFMC displaying the highest degree of mesenchymal activation (Figure 5D). There was also a general increase in YAP in all these transformed cells, which was highest in the TFMC population (Figure 5D). YAP has been shown to control the production of EGF family growth factors 39, suggesting that the strong ERK and EGFR activation responses previously described in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors can be accounted for by the presence of this more invasive TFMC cell population.13 Tumor TRSCs were enriched in WNT signaling, suggesting that a relatively small but significant proportion of the cancer epithelial cells in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors rely on WNT activation likely to function as a reserve cell type (Figure 5D). Therefore, cTAs are the most probable origin of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumor epithelial cells, which are hierarchically structured reflecting the non-transformed intestinal cell lineage organization but with critical alterations in tumorigenic pathways that equip the serrated tumor cells with differential signaling characteristics (Figure 5E). In the secretory compartment, TGCs showed enrichment in EMT, YAP, WNT, and metaplasia signatures, as compared to the non-tumor mature goblet population (Figures 5F and S6O), indicating that the fetal lineage transition was observed in both enterocytic and goblet populations of serrated tumors.

PEGPH20 treatment differentially affected the three non-secretory tumor cell populations (Figure 5G). Thus, while there was a limited proportional reduction of TcTAs, we found a clear reduction in the proportion of TFMCs but with a relative enrichment in the proportion of TRSCs in the persistent tumor cell population (Figure 5G). Trajectory analysis of the PEGPH20-treated condition showed a total disruption in the flow from TcTA to TFMC, while TFMC gained the ability to differentiate into TRSCs (Figure 5G). Next, we determined the localization of TFMCs (ANXA10+ and MUC5AC+) and TRSCs (CLU+) in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors. Consistent with their enterocytic features and metaplastic phenotype, TFMCs were more exposed to the cancer luminal surface, whereas TRSCs were distributed at the crypt-bottom areas (Figures 5H and 5I). PEGPH20 strongly reduced the presence of TFMCs (ANXA10+ and MUC5AC+ staining), whereas that of TRSCs (CLU+ staining) was not reduced, in agreement with our scRNAseq findings (Figures 5H and 5I). MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz recapitulated the observed phenotype in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors showing in vitro upregulation of Anxa10, Muc5ac and Clu as compared with MTO-sgC (Figure S6P). PEGPH20 treatment reduced Anxa10 and Muc5ac expression without changes in Clu levels in MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz (Figure S6P). These results support a model whereby HA depletion in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors induced a lineage switch from TFMC to TRSC, suggesting that the WNT-independent TFMC population, which is likely maintained by YAP, can acquire a TRSC phenotype most probably supported by a WNT-dependent state. Regarding the goblet cell compartment, PEGPH20 treatment strongly reduced the proportion of TGCs in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors, as also demonstrated by ANXA10+/Alcian Blue and ANXA10+/MUC2+ staining (Figures 5J and 5K), demonstrating that stromal HA accumulation is a crucial event for the maintenance of TGCs. Similar results in cell population changes upon PEGPH20 treatment were observed when colon tumors were analyzed (Figures S6Q and S6R).

To establish the human relevance of these findings, we have analyzed scRNA-seq data from three previously published and available human CRC datasets: GSE132465,26 GSE166555,40 and GSE17834141 for a total of 97 CRC patients. By fractionating epithelial cells from primary colorectal tumors, we found that the four representative gene signatures derived from our mouse model, namely, TcTA, TRSC, TFMC, and TGC, were highly expressed in human CRC tumors (Figures S7A-S7L). TcTA and TRSC signatures were mainly present in the iCMS2 subtype, left-side tumors, and T2-T3 stages, while TFMC and TGC were associated with the poor prognosis subtype iCMS3, right-side tumors, and the T4 stage concordant with their aggressive features found in the mouse intestine (Figure S7M). The analysis of the tumor epithelium of the CRC TMA by multiplex-Opal staining for HA, aPKC, ANXA10, and MUC5AC demonstrated that both ANXA10-high and MUC5AC-positive staining are predictors of poor prognosis, consistent with previous data showing that iCMS3 tumors have a worse prognosis and are the ones enriched in metaplasia genes 42, and with our results demonstrating that the TFMC population is enriched in iCMS3 tumors. The acquisition of metaplasia markers such as ANXA10 or MUC5AC in aPKC-low/HA-positive tumors predicted poor survival as compared to those that have not acquired these markers (Figures 5L, 5M, and S7N). Multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that both ANXA10 and MUC5AC expression were significantly associated with aPKC-low and HA-positive expression independent of other pathological features (Figures S7O-S7R). These results further support the link between the fetal/metaplastic state (TFMC) and malignancy in human mCRC.

HA depletion reformats the CAF-epithelial tumor interactions

Since TFMCs colocalize with telocytes at the luminal surface of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors and both populations were sensitive to PEGPH20, we posited that their interaction might be critical for the maintenance of tumor growth. Therefore, we investigated the crosstalk between fibroblasts and tumor epithelial populations by CellphoneDB analysis.43 Telocytes showed the highest interactions with tumor cells compared to those of the intermediate or trophocyte populations (Figure 5N). Consistently, conditioned media of fibroblasts isolated from Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre mice (telocytes) induced the upregulation of metaplastic markers (Anxa10 and Muc5ac) in in vitro MTO cultures, which was rescued by PEGPH20 (Figure 5O). Telocytes were enriched in growth factors such as Igf1, Ereg, Fgf2/7, Nrg1, and Hgf, while their cognate receptors were broadly expressed by tumor cells (Figure 5P), which could account for the regulation of TFMCs by telocytes. We also identified Areg as a specific growth factor expressed in TFMC, interacting with Egfr and Icam1 in telocytes. Tff1, previously identified as a biomarker for SSL 44, was expressed by TFMCs and could support telocytes expressing Fgfr2 (Figure 5P). This set of interactions highlights the bi-directional telocyte-TFMC crosstalk that determines mesenchymal tumor malignancy. PEGPH20 induced a high number of communications between TRSC and trophocytes while switching off the interactions between TFMCs and telocytes (Figure 5Q). PEGPH20 treatment also enriched trophocytes in Rspo1/3, which interacted with their cognate receptor Lgr5 in the TRSC compartment (Figure 5R), in keeping with recent evidence on the maintenance by trophocytes of adult stem cell homeostasis through WNT signaling.27,45

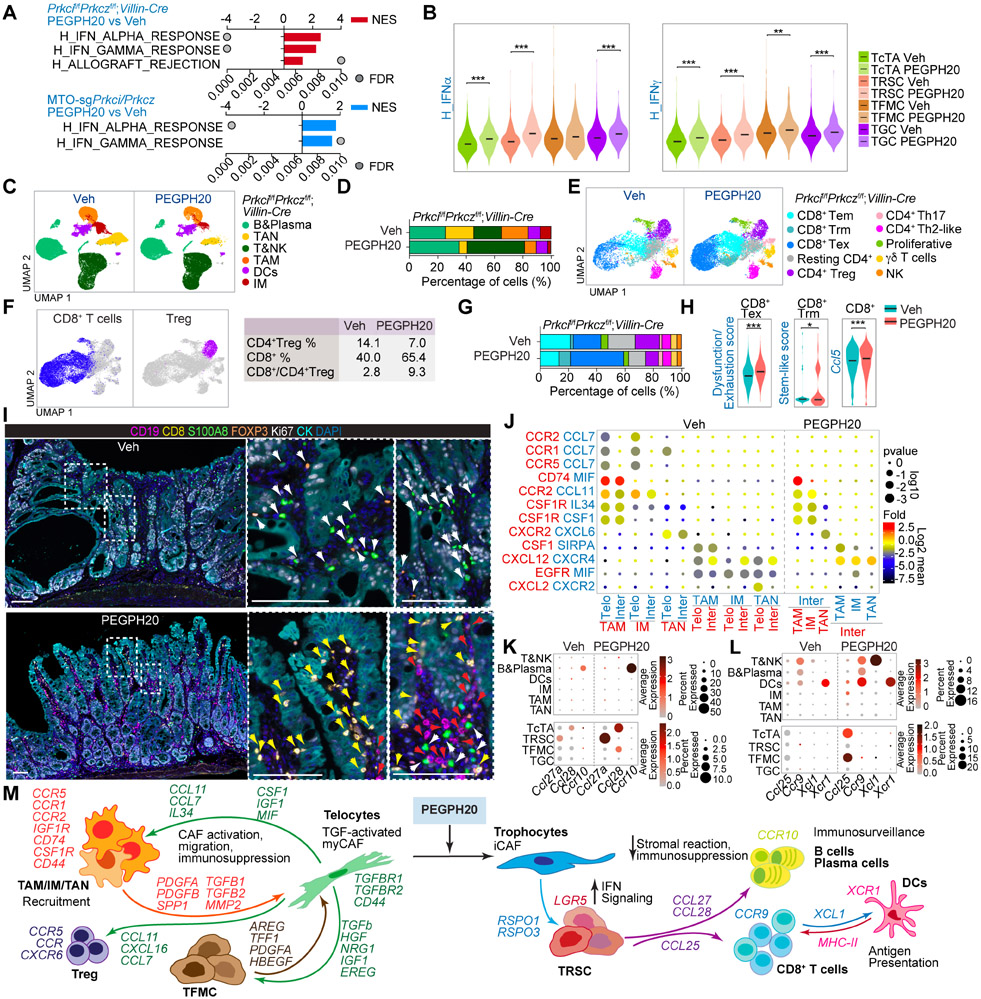

Microenvironmental HA is critical for cancer immunosuppression in mesenchymal tumors

Our previously published data demonstrated that reduced IFN signaling, which in turn impeded CD8+ T cell-mediated immunosurveillance, was a central event for the initiation of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors.13,46 PEGPH20 treatment rescued the IFN inhibition in these tumors as demonstrated by enrichment in IFN and allograft rejection signatures by GSEA of RNAseq of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre endogenous tumors and allografts from MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz (Figure 6A). This enrichment in IFN upon HA depletion was more evident in the TRSCs, which was the epithelial tumor sub-population more resistant to PEGPH20 treatment (Figure 6B). These results suggest that PEGPH20 could enable ICB therapy through upregulating the IFN pathways in the “persister” epithelial cancer cells by switching them from immunoevasion to immunosurveillance mode. To explore this possibility, we determined how PEGPH20 reprogrammed the immune system of intestinal mesenchymal tumors. Unsupervised clustering of the immune component of the scRNAseq data from Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors identified six major cell types: tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), dendritic cells (DCs), inflammatory monocytes (IMs), B and plasma cells, T cells, and natural killer (NK) cells (Figures 6C, S8A and S8B). Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors were rich in TAN, TAM, and IM, and PEGPH20 treatment reduced the levels of these myeloid cell types and increased the proportion of T and B cells (Figures 6C and 6D). Further unsupervised T and NK cell clustering identified three different CD8+ T cells and four CD4+ T cell populations, along with proliferative T cells, γδ T cells, and NK cells (Figures 6E, S8C and S8D). PEGPH20 reduced CD4+ Treg cells, which, together with the relative enrichment in CD8+ T cells, resulted in an increased CD8+:Treg ratio in their TME, a critical anti-tumorigenic state (Figure 6F). Within the CD8+ T cells, we found three functional states: CD8+ T effector memory (Tem), CD8+ T resident memory (Trm), and CD8+ T exhausted (Tex) (Figures 6E and S8D). CD8+ Tex cells showed the highest degree of dysfunctionality and exhaustion, whereas CD8+ Trm were enriched in stemness (Figure S8E). The lower levels of exhaustion markers and the expression of Gzmk suggested a pre-dysfunctional phenotype as the main characteristic of the CD8+ Tem population (Figure S8D). PEGPH20 treatment increased the proportion of CD8+ Trm and CD8+ Tex cells and resulted in the enrichment in the signatures corresponding to CD8+ T cells exhaustion, stem-like, and expansion, as indicated by the increased expression of Ccl5 (Figures 6G and 6H), suggesting strong CD8+ T cells activity in response to PEGPH20. VECTRA multiplex imaging showed a substantial accumulation of myeloid cells and CD4+ Tregs, a minimal presence of B cells, and the exclusion of CD8+ T cells from the tumoral areas in Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors (Figures 6I and S8F), which is consistent with the immunosuppressive environment of mCRC. PEGPH20 treatment produced a concomitant reduction of myeloid cells and CD4+ Tregs with strong recruitment of B, plasma, and CD8+ T cells to infiltrate the tumors from the endogenous and subcutaneous aPKC-deficient mouse models (Figures 6I and S8F-S8H). These results demonstrate that the immune landscape of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors resembles the immunosuppressive features and immune cell composition of mCRC, which can be reprogrammed by PEGPH20 treatment.

Figure 6. HA induces immunosuppression and impairs immunosurveillance in mesenchymal intestinal tumors.

(A) GSEA of transcriptomic data from Quant-seq on Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre PEGPH20-treated tumors versus Veh (n=3) (top), and MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz PEGPH20-treated tumors (n=4) versus Veh (n=3) (bottom) using compilation H (MSigDB).

(B) Violin plots for the indicated gene signatures in TcTAs, TRSCs, TFMCs, and TGCs treated with Veh or PEGPH20. The top and bottom of the violin plots represent the minimal and maximal values, and the width is based on the kernel density estimate of the data, scaled to have the same width for all clusters. Horizontal lines represent median values. Unpaired t-test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

(C and D) UMAP of all immune cells colored by the major immune cell type (C) and immune-cell-type percentage relative to the total immune cells count per treatment (D).

(E and F) UMAP of all T cells colored by the T cell type (E) and canonical lineage marker expression for CD8+T cell and CD4+Treg (left) showing the percentage of CD4+Treg, CD8+T, and CD8+T:CD4+Treg ratio per treatment (right) (F).

(G) T-cell-type percentage relative to the total T cells count per treatment.

(H) Violin plots for the indicated gene signatures in CD8+T cells treated with Veh or PEGPH20. The top and bottom of the violin plots represent the minimal and maximal values, and the width is based on the kernel density estimate of the data, scaled to have the same width for all clusters. Horizontal lines represent median values. Unpaired t-test, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

(I) Seven-color overlay image for the indicated protein staining in Veh- and PEGPH20-treated tumors (n=3). Scale bars, 100 μm. The white arrows denote CD4+Treg and myeloid cells; the yellow arrows mark CD8+T cells and the red arrows point to B cells.

(J) CellphoneDB analysis of ligand-receptor pairs of cytokines between telocytes, intermediate and myeloid cells in Veh- or PEGPH20-treated tumors.

(K and L) Dot plot of ligand-receptor pairs of Ccl27a/Ccl28-Ccr10 (K) and Ccl25-Ccr9 and Xcl1-Xcr1 (L) between tumor epithelial cells and immune cells in Veh- or PEGPH20-treated tumors.

(M) Predicted regulatory crosstalk between tumor epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and the immune system in Veh- or PEGPH20-treated tumors.

See also Figure S8.

The permissive immune environment of mesenchymal tumors is orchestrated by cross-compartment interactions and maintained by HA

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the tumor response to PEGPH20, we determined cell-specific receptor and ligand expression patterns between the three main compartments of the TME. Based on CellphoneDB analysis, the predicted cell-cell communication networks highlighted the central role of telocytes in the recruitment of TAMs, IM, and TANs to the TME driven by mesenchymal aPKC-deficient epithelial cancer cells (Figure S8I). Analysis of HA receptors showed a higher expression of Cd44 in telocytes and myeloid cells, consistent with the high sensitivity of these two populations to HA-depletion (Figure S8J). Focusing on the cytokines and their receptors that mediate myeloid cell recruitment to Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors, we identified stromal-immune interactions between Ccl7- and Ccl11-expressing telocytes with myeloid cells positive for their cognate receptors Ccr2/Ccr1/Ccr5, and Ccr2, respectively. Cxcl2-expressing telocytes specifically recruit neutrophils positive for Cxcr2 (Figure 6J), which can also account for the accumulation and recruitment of CD4+ Tregs that express Ccr5/Ccr2 (Figure S8K). Therefore, eliminating telocytes by HA-depletion might explain the reduction of myeloid and CD4+Tregs in mesenchymal intestinal tumors upon PEGPH20 treatment. Consistently, conditioned media from fibroblasts isolated from to Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre intestinal tissue (telocytes) promoted macrophage chemotaxis, which was abolished by PEGPH20 (Figure S8L). PEGPH20 reduced the TGFβ signals provided by myeloid cells and CD4+Tregs, contributing to the low amount of activated telocytes, EMT, and invasive characteristics of TFMCs (Figure S8M and S8N). PEGPH20 also repressed the secretion of growth signals from telocytes to myeloid cells and CD4+ Tregs (Figures S8O and S8P). Spp1, previously identified as a critical marker of myeloid cells in CMS4 CRC,26 was expressed by TAMs and might also account for the maintenance of telocytes expressing its receptors, Ptger4 and Cd44, in the mesenchymal stroma of Prkcif/fPrkczf/f;Villin-Cre tumors (Figures S8O and S8P). PEGPH20 treatment eliminates the interaction between Spp1-Ptger4/Cd44 in fibroblasts and the Spp1 interactions found between telocytes and CD4+ Tregs (Figure S8P). PEGPH20 also increased the secretion of Ccl27a in TRSCs and Ccl28 in TcTAs and in the residual TFMCs to recruit B cells and that of Ccl25 in TcTAs and TFMCs to attract Ccr9-expressing T cells to the tumor epithelial compartment (Figures 6K and 6L). There was also a PEGPH20-driven interaction between Xcl1 expressed in T cells and Xcr1-expressing DCs (Figure 6L), shown to be critical for antigen presentation and a cytotoxic immune response.47,48 These results support a model whereby the elimination of telocytes by PEGPH20 alleviates the immunosuppression triggered by myeloid cells and CD4+ Tregs, which cooperates with the induction of immunosurveillance through IFN activation in the tumor epithelial cell compartment, and the release of cytokines involved in B and CD8+ T cell infiltration (Figure 6M).

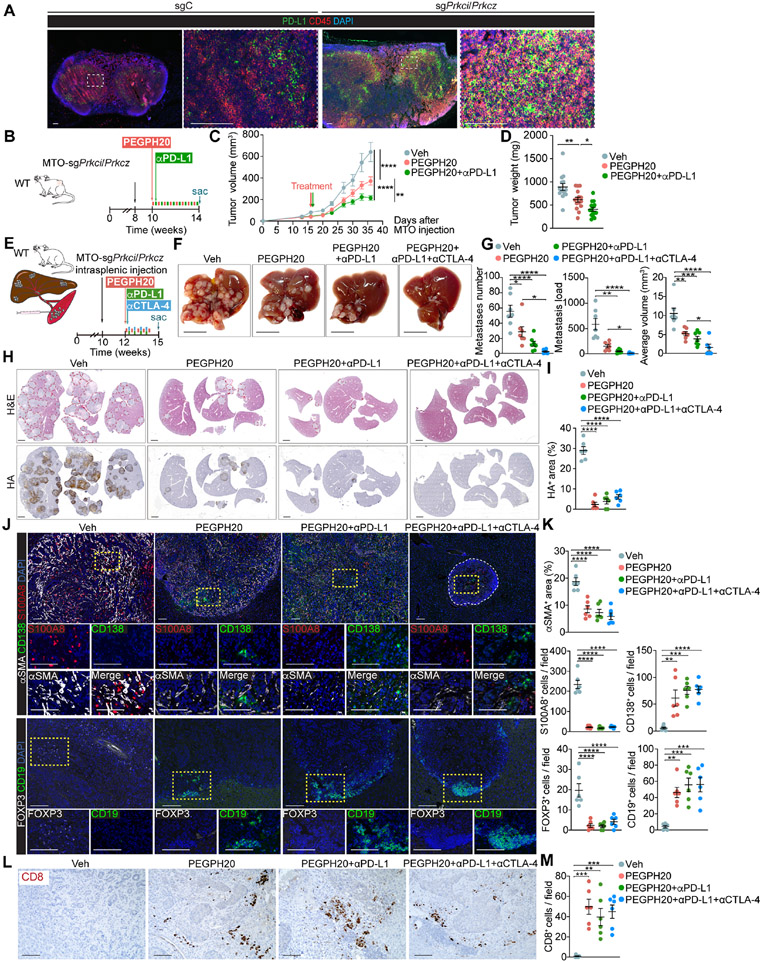

HA depletion renders aPKC-deficient tumors sensitive to ICB therapy

The remodeling of the immune microenvironment by PEGPH20 suggested that it might increase responses to ICB therapy. Since draining lymph nodes of MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz tumors showed a significantly increased proportion of immune cells expressing PD-L1 (Figure 7A), we tested the therapeutic potential of PEGPH20 in combination with anti-PDL1. The administration of anti-PD-L1 with PEGPH20 significantly enhanced the anti-tumor activity of PEGPH20 as determined by the reduced volume and weight of MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz tumors, while anti-PD-L1 alone showed no effect (Figures 7B-7D and S9A-S9C). PEGPH20 treatment also reduced the HA content and intensity of αSMA+ stromal staining and was sufficient to bring CD8+ T and B cells to the tumor and to reduce the amount of immunosuppressive myeloid and Tregs (Figures S9D and S9E). Since the liver is the most common site for CRC metastasis, we carried out an orthotopic liver metastasis model in which MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz organoids were transplanted via intrasplenic injection into syngeneic WT C57BL/6 hosts (Figure 7E). Different treatment groups were initiated two weeks after injection to allow the establishment of liver metastasis. Treatment with PEGPH20 as monotherapy was effective in reducing liver metastasis number, load, and size, as compared to vehicle, as well as that combination with anti-PD-L1 alone or plus anti-CTLA-4 further enhanced its effectiveness (Figures 7F and 7G). Liver metastases driven by MTO-sgPrkci/sgPrkcz induced a highly desmoplastic response as determined by HA and αSMA staining, which was effectively reduced by PEGPH20 treatment (Figures 7H-7K). The immunosuppressive microenvironment of these liver metastases was characterized, like in the primary tumor, by high numbers of infiltrating myeloid cells and Tregs, and the absence of B and T cells, which were all reverted by PEGPH20 with a significant decrease in myeloid and T regs and a robust infiltration inside the remaining metastasis of B and plasma cells along with infiltrating CD8+ T cells (Figures 7J-7M). These results demonstrate that PEGPH20 treatment makes aPKC-deficient tumors and their liver metastasis sensitive to anti-PD-L1 therapy.

Figure 7. The combination therapy of PEGPH20 with anti-PDL1 improves the response of mesenchymal CRC tumors.

(A) IF for PD-L1 (green) and CD45 (red) of tumor-draining lymph nodes in MTO-sgC and MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(B-D) Subcutaneous injection of MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz in WT mice treated twice a week with PEGPH20 (0.0375 mg/kg) and αPD-L1 (5 mg/kg) for 4 weeks (n:Veh= 14, PEGPH20-treated=15 and PEGPH20-treated with αPD-L1=15). Experimental design (B); tumor volume, two-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 (C); tumor weight, one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (D). Sac: sacrificed.

(E-M) Intrasplenic injection of MTO-sgPrkci/Prkcz in WT mice. Mice were treated twice a week with Veh or PEGPH20 0.0375 mg/kg and/or αPD-L1 (5 mg/kg) and/or αCTLA-4 (100 μg/dose) for 2.5 weeks (n: Veh-treated =7, PEGPH20-treated=7, PEGPH20 and αPD-L1-treated =7, and PEGPH20 and αCTLA-4-treated=6). Experimental design (E); macroscopic images of liver metastasis tumors (F); total metastases number, tumor load, and average tumor volume, one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (G); H&E staining and IHC for HA (H) and quantification, one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, (n=4), ****p < 0.0001 (I); IF for αSMA (white), CD138 (green) and S100A8 (red), IF for FOXP3 (white) and CD19 (green) (J), and staining quantification, one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 (K); CD8 staining (L) and quantification, one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s test, data shown as mean ± SEM, (n=3), **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (M); in liver metastases (n=5). Scale bars, 10 mm (F), 2 mm (H), 100 μm (J, L). The red line denotates liver metastases (H). Sac: sacrificed.

See also Figure S9.

DISCUSSION

The cellular and molecular interactions that define the TME of mesenchymal tumors and its potential therapeutics are poorly understood. We have recently demonstrated that reduced levels of the two aPKC isoforms correlated with features of mesenchymal tumorigenesis in human CRC, as well as that their simultaneous genetic inactivation in the intestinal epithelium is sufficient to induce this type of tumor in mice in the context of a morphologically serrated pathway driven by YAP-ERK and without mutations in BRAF or the APC/WNT cascade.13,14 Here we show that mesenchymal tumorigenesis, which is characterized in CRC by an EMT epithelium together with a desmoplastic and inflamed immune landscape with the exclusion of the CD8+ T cells to the tumor-stromal periphery, can also be induced in the context of tubular adenocarcinomas by the simultaneous inactivation of both aPKCs in organoids driven by mutations in the APC/KRAS/p53/TGFβ cassette. These observations are consistent with a large proportion of tumors harboring APC mutations that also express low aPKC levels and that show a mesenchymal phenotype. Our data reveal that a common critical feature shared by mCRCs is the accumulation of HA in their stroma. We also show that HA deposition not only contributes to higher levels of malignancy in both serrated and conventional settings but also makes these tumors vulnerable to the action of PEGPH20. The initial generation of HA can be accounted for by the cell-autonomous activation of HAS expression upon the acute simultaneous genetic inactivation of both aPKCs in the intestinal epithelium.

Treating mesenchymal tumors in mice with PEGPH20 not only results in the cell-autonomous reduction of the epithelial cell population with the most aggressive invasive features (TFMCs) but also promotes the recruitment of CD8+ T and B cells with the concomitant reduction in the infiltrating Tregs and immunosuppressive myeloid cells, which underly the reduction in tumor load. This is in contrast with the effects of inactivating the TGFβ stromal cascade, which is insufficient to reactivate the immune system or to reduce the tumor burden.13,17,18 Since other strategies to target the ECM, like the genetic inactivation of type I collagen, gave inconsistent results,23,24 PEGPH20 emerges as a potential treatment of mCRC tumors as a stroma-targeting monotherapy. The fact that PEGPH20 treatment of mCRC tumors results in the accumulation of CD8+ Trm cells explains why these PEGPH20-treated tumors further respond to anti-PD-L1 treatment, establishing HA degradation as an obligated step in the conversion of residual mCRC, PEGPH20-resistant tumor cells, from an ICB refractory state to a sensitive one.

These results should be considered in the context of previous clinical trials using PEGPH20 for the treatment of pancreatic cancer (PDAC), another type of desmoplastic neoplasia. The initial rationale was based on the assumption that this treatment would result in improved drug delivery to solid tumors and prolonged survival, as shown in preclinical models.20,21,49 Unfortunately, these clinical studies gave mixed results, and although patients showed a higher response rate in the experimental arm, there was no improvement in the duration of response or progression-free or overall survival.50-53 However, what we show here is that PEGPH20 triggers a complete remodeling of the mCRC TME, impacting not only the levels of HA but also the CAF populations and the immune compartment. A similar degree of remodeling was reportedly achieved only when PEGPH20 was used in combination with GVAX immunotherapy in PDAC preclinical models.54 A potential explanation for the discrepant findings of the lack of effect of monotherapy with PEGPH20 in PDAC as compared to the positive effects in mCRC may rely on the differences between the TME of these two types of tumors. Thus, PDAC tumors are known to be immune-deserted, characterized by a paucity of T cells in either the parenchyma or the stroma of the tumor. To make these tumors responsive to immunotherapy would require a T cell priming agent in combination with stroma-targeting. In contrast, aPKC CRC tumors are immune-excluded and, therefore, characterized by the presence of abundant immune cells that do not penetrate the parenchyma of these tumors but instead are retained in the stroma that surrounds the tumor epithelium. The recruitment of pre-existing T cells is, therefore, the rate-limiting step that is targeted by PEGPH20 to allow the cancer-immunity response in mCRC. Therefore, PEGPH20 should be considered a valid strategy to treat mCRC as monotherapy and/or as an enabler of ICB. In this regard, it is important to emphasize that the dose of PEGPH20 utilized in the PDAC clinical trials was approximately 400-fold lower than the one used in PDAC preclinical models, indicating that to achieve clinical response in PDAC patients, much higher hyaluronidase doses would be required, which will be unfeasible due to toxicity. In marked contrast, we show here that mCRC is fully sensitive to the clinical doses of PEGPH20 (0.0375 mg/Kg), which strongly suggests that perhaps PDAC was not the right type of neoplasia to be treated with PEGPH20, whereas a better response would be obtained in patients with mCRC.

Another critical question to ensure the success of PEGPH20 in the clinic is the identification of better biomarkers for patient selection. In this regard, our data show that HA expression does not predict survival in CRC patients but that low aPKC levels combined with high HA levels define the cohort of CRC patients with the worst prognosis. Evidence presented here in two mCRC mouse models establishes that low aPKC/HA-positive mCRC patients will benefit from PEGPH20-based treatment. Our analysis demonstrates that the epithelial compartment of mCRC tumors is organized, echoing the hierarchy and cell types of the normal intestine. This includes the existence of tumor progenitor-like and differentiated-like populations.55-57 Thus, according to our data, aPKC-deficient serrated tumors originate from a highly proliferative cTA population, which evolves into a tumor cycling cell type expressing a signature previously identified in Lgr5− negative CRC tumor cells.34 Therefore, our data strongly support the notion that differentiated cells retaining progenitor features can be transformed to generate a serrated mCRC. In this regard, a recent scRNAseq study in human patients established that whereas conventional adenomas originated from the expansion of adult stem cells at the bottom of the intestinal crypt, serrated adenomas emerge from a more differentiated cell state through a metaplastic process whereby intestinal cells trans-differentiate to a gastric-fetal phenotype.35 The TFMC subpopulation identified in mCRC is what accounts for the most invasive and aggressive phenotype of this type of tumor and has symbiotic crosstalk with telocytes, which is the tumor fibroblast population with the most CAF features. The fact that PEGPH20 treatment completely ablated the telocyte subpopulation contributes to the eradication of the TFMC compartment and the reformatting of the mCRC TME towards a TRSC-trophocyte-dominated condition.

TRSCs originated from the TcTA population but, in contrast to the TFMCs, retain features of adult stemness such as a heightened WNT pathway, which is reduced in the TFMC population that is instead characterized by a YAP-driven signature. TRSCs are reminiscent of the Clu+ “revival stem cells” that emerge during non-tumor intestinal injury-regeneration processes.37 This cell type is in a cooperative connection with the trophocyte fibroblasts at the bottom of the crypt through a WNT-dependent network, resembling the requirements of adult intestinal stem cells.58,59 Since the non-tumor Clu+ “revival stem cells” hold the ability to repopulate the whole normal epithelium, we posited that the TRSCs would be able to recreate the entire mCRC upon the cessation of PEGPH20 treatment. In this regard, we show here that these cells are resistant to PEGPH20 treatment in vitro and that they account for a large proportion of the whole “persister” population that is not eradicated by PEGPH20 treatment. The fact that PEGPH20 promotes the accumulation of trophocytes in the mCRC TME further helps to feed TRSCs as a possible source of therapy resistance. Our findings indicate that persistent cancer cells in PEGPH20-treated tumors are enriched in IFN signatures, which contributes to the sensitivity of these PEGPH20-treated tumors to anti-PD-L1 therapy and suggests that, although PEGPH20 treatment profoundly represses mCRC tumorigenesis, combination with ICB will help prevent cancer rebound. Therefore, PEGPH20 reformats the mCRC TME from a TFMC-telocyte-driven scenario of aggressive tumorigenesis to a TRSC-trophocyte “persister” paradigm that can be, nonetheless, ablated by ICB treatment through the upregulation of immunosurveillance IFN-driven pathways by PEGPH20.

STAR★ METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Jorge Moscat (jom4010@med.cornell.edu).

Materials Availability

Cell and mouse lines generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact upon request with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code Availability

The Quantseq, and scRNA-seq datasets generated during this study have been deposited to the GEO repository on the NCBI website (GEO: GSE207780, GSE207778, GSE207776, and GSE207779) and are publicly available as of the date of publication.

This paper reports data derived from published and publicly available datasets GEO: GSE132465, GSE166555, GSE178341, GSE14333, and GSE39582. These datasets are located on the key resources table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse anti-β-actin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A1978, RRID: AB_476692 |

| Rabbit anti-aPKCs | Abcam | Cat# ab59364; RRID: AB_944858 |

| Rabbit anti-CD8 | Abcam | Cat# ab209775; RRID: AB_2860566 |

| Rat anti-CD8 | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 557654, RRID: AB_396769 |

| Rabbit anti-CD19 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 90176S, RRID:AB_2800152 |

| Rabbit anti-MRP8 | Abcam | Cat# ab92331, RRID: AB_2050283 |

| Rabbit anti-CD138 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# PA5-16918, RRID: AB_10979011 |

| Rabbit anti-FOXP3 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#12653, RRID: AB_2797979 |

| Rabbit anti-PDL1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 64988, RRID: AB_2799672 |

| Rat anti-CD45 | BD Parmingen | Cat# 550539, RRID: AB_2174426 |

| Mouse anti-panCK | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# MA5-13156, RRID: AB_2174426 |

| Rabbit anti-panCK | Abcam | Cat# ab9377, RRID: AB_307222 |

| Rabbit anti-Ki67 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#12202, RRID: AB_2620142 |

| Rabbit anti-MUC2 | Abcam | Cat# ab272692, RRID: AB_2888616 |

| Rabbit anti-MUC5AC | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#61193, RRID: RRID:AB_2799603 |

| Rabbit anti-ANXA10 | Abcam | Cat# ab213656, RRID: RRID:AB_2921231 |

| Rabbit anti-CLU | Abcam | Cat# ab184100, RRID: AB_2892532 |

| Goat anti-CLU | R&D systems | Cat# AF2747, RRID: AB_2083314 |

| Rabbit anti-PDGFRa | Abcam | Cat# ab203491, RRID: AB_2892065 |

| Mouse anti-PDGFRb | Abcam | Cat#ab69506, RRID:AB_1269704 |

| Rabbit anti-CD34 | Abcam | Cat# ab81289, RRID: AB_1640331 |

| Mouse anti-CD31 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# RB10333P1, RRID: AB_720501 |

| Rat anti-CD31 | Dianova | Cat#DIA-310, RRID:AB_2631039 |

| Rabbit anti-NRG1 | Abcam | Cat# ab191139, RRID: RRID:AB_2921232 |

| Mouse anti-Smooth muscle actin | Dako | Cat# M0851, RRID: AB_2223500 |

| Biotinylated recombinant HA-binding protein (HTI-601) | Halozyme | Provided by Halozyme Therapeutics |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG1, secondary, HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# PA1-74421, RRID: AB_10988195 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG, secondary, HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 31430, RRID:AB_228307 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG, secondary, HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 31461, RRID: AB_228347 |

| Goat anti-Rat IgG, secondary, HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 62-9520, RRID: AB_87993 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG, secondary, Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A10042, RRID: AB_2534017 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG, secondary, IRDye 800 | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 926-32211, RRID: AB_621843 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG1, secondary, IRDye 800 | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 926-32350, RRID: AB_2782997 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG, secondary, IRDye 800 | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 926-32210, RRID: AB_621842 |

| InVivoMAb rat IgG2b isotype control | BioXCell | BE0090, RRID:AB_1107780 |

| InVivoMAb anti-mouse PD-L1 (B7-H1) | BioXCell | BE0101, RRID:AB_10949073 |

| InVivoPlus anti-mouse CTLA-4 (CD152) | BioXCell | BP0164, RRID:AB_10949609 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human Colorectal cancers (CRC) | Osaka City University Hospital, Osaka, JAPAN | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| HBSS (no calcium, no magnesium) | GIBCO | Cat# 14175095 |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide | Fisher BioReagents | Cat# BP2311 |

| Chloroform | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 288306 |

| Methanol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 1424109 |

| Tryple Express | Life Technologies | Cat# 12605-010 |

| HEPES | Gibco | Cat# 15630080 |

| PBS (no calcium, no magnesium) | Gibco | Cat# 10010-023 |

| Quick-RNA Miniprep Kit | Zymo Research | Cat# R1054 |

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Invitrogen | Cat# AM7021 |

| TRIzol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15596018 |

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 12634010 |

| RPMI | Corning | Cat#15-040-CV |

| GlutaMAX Supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 35050061 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin solution | Corning | Cat# 30-002-CI |

| Y-27632 | Tocris | Cat# 1254 |

| B27 Supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 17504001 |

| B27 Supplement minus vitamin A | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 12587001 |

| N2 Supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 17502048 |

| Murine EGF | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# PMG8045 |

| Human EGF | Peprotech | Cat#AF-100-15 |

| Human FGF-2 | Peprotech | Cat#100-18B |

| Human IGF-1 | Biolegend | Cat#590906 |

| Recombinant human Wnt-3a | R&D systems | Cat#5036-WN/CF |

| A83-01 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#SML078 |

| Human [Leu15]-Gastrin I | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# G9145 |

| Recombinant murine R-Spondin 1 | R&D systems | Cat# 3474-RS-050 |

| Recombinant murine Noggin | Peprotech | Cat# 250-38 |

| Recombinant murine M-CSF | Peprotech | Cat# 315-02 |

| Matrigel® Growth Factor Reduced (GFR) Basement Membrane Matrix | Corning | Cat# 356230 |

| Liberase™ TM Research Grade | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 5401119001 |

| Collagenase A | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 10103586001 |

| Dispase II | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# #D4693 |

| DNase I | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 04716728001 |

| 4-OH-tamoxifen | Millipore-Sigma | Cat# H7904 |

| TrueCut Cas9 Protein v2 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A36498 |

| DAPI | Life Technologies | Cat# D1306 |

| Streptavidin, secondary, Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# S11226 |

| Streptavidin, secondary, Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# S11223 |

| Trypan Blue Solution, 0.4% | Gibco | Cat# 15250061 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Neon™ 10μl Electroporation Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# MPK1096 |

| Chromium Single Cell 3′ Gene Expression Solution v2 | 10X Genomics | Cat#PN-120237 |

| EasySep™ Dead Cell Removal (Annexin V) Kit | STEMCELL Technologies | Cat# 17899 |

| VECTASTAIN® Elite® ABC-HRP Kit | Vector | Cat# PK-6100 |

| Automated Opal 7-Color IHC Kit | AKOYA BIOSCIENCES | Cat# NEL821001KT |

| Manual Opal 4-Color IHC Kit | AKOYA BIOSCIENCES | Cat# NEL810001KT |

| Trichrome Stain (Masson) Kit | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# HT15 |

| Corning Biocoat Control Inserts | Corning | Cat# 354578 |

| Alexa Fluor™ 488 Tyramide Superboost™ Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# B40932 |

| Deposited data | ||

| sc-RNA-seq | This study | GEO: GSE207780 |

| 3’ RNA-seq (Prkcifl/fl Prkczfl/fl Villin-Cre-Veh or -PEGPH20 treated) | This study | GEO: GSE207778 |

| 3’ RNA-seq (sgPrkci/Prkcz and sgC MTOs) | This study | GEO: GSE207776 |

| 3’ RNA-seq (sgPrkci/Prkcz MTOs-Veh or -PEGPH20 treated) | This study | GEO: GSE207779 |

| Raw Data | This study; Mendeley Data | https://doi.org/10.17632/vbzbzhrw98.1 |

| Single cell 3′ RNA sequencing from patients with CRC | Lee et al.26 | GEO: GSE132465 |

| Single cell 3′ RNA sequencing from patients with CRC | Uhlitz et al.40 | GEO: GSE166555 |

| Single cell 3′ RNA sequencing from patients with CRC | Pelka et al.41 | GEO: GSE178341 |

| Microarray from primary CRC tumors | Jorissen et al.73 | GEO: GSE14333 |

| Microarray from primary CRC tumors | Marisa et al.74 | GEO: GSE39582 |

| TCGA-COREAD | cBioportal | http://www.cbioportal.org/index.do |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human CRC (sgPRKCI/PRKCZ) | This study | N/A |

| Mouse tumor organoid (MTO) | Tauriello et al.17 | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: Prkcifl/fl Prkczfl/fl | Nakanishi et al.13 | N/A |

| C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No: 000664 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Real-time PCR primers | This manuscript | Table S1 |

| CRISPR guides | This manuscript | Table S2 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Graphpad Prism 8 | Graphpad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientificsoftware/ |

| QuPath v.0.1.3 | Queen’s University, Belfast, Northern Ireland | https://qupath.github.io |

| ImageJ | NIH | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Zen blue | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/us/products/microscope-software/zen.html |

| RStudio (1.1.456) | R Core Team | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| R | R Core Team | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| GSVA; version 1.26.0 | Bioconductor | https://github.com/rcastelo/GSVA |

| GSEA (v4.1.0) | Broad Institute | http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp |

| BaseSpace | Illumina | https://basespace.illumina.com/ |

| Morpheus | Broad Institute | https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/ |

| CMScaller v0.99.1 | Eide et al.72 | https://github.com/peterawe/CMScaller |

| CellPhoneDB v.2.0.0 | Efremova et al.43 | https://www.cellphonedb.org |

| GenePattern | Broad Institute | https://cloud.genepattern.org/gp/pages/login.jsf |

| Lexogen QuantSeq DE 1.3.0 | BlueBee Cloud | https://www.bluebee.com |

| Cell Ranger (v3.0) | Langmead et al.75 10X genomics | http://software.10xgenomics.com/single-cell/overview/welcome |

| Seurat 3.0 | Stuart et al.76 | https://github.com/Satijalab/seurat |

| kb_python | Bray et al.69;Melsted et al.70 | https://github.com/pachterlab/kb_python |

| scVelo package | Bergen et al.71 | https://scvelo.readthedocs.io/VelocityBasics/ |

| Harmony | Korsunsky et al.67 | https://portals.broadinstitute.org/harmony/articles/quickstart.html |

| PhenoChart Whole Slide Viewer | AKOYA BIOSCIENCES | https://www.akoyabio.com/support/software/phenochart-whole-slide-viewer/ |

| CaseViewer | 3DHistech, Budapest, Hungary | https://www.3dhistech.com/solutions/caseviewer/ |

| Other | ||

| EVOS FL Auto Imaging System | Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| EVOS M5000 Imaging System | Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| TissueLyser II | QIAGEN | Cat# 85300 |

| NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer | Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| Zeiss LSM 710 NLO Confocal Microscope | Zeiss | N/A |

| Neon™ Transfection System | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# MPK5000 |

| Pannoramic Scanner | 3DHistech, Budapest, Hungary | N/A |

| Vectra Polaris Automated Quantitative Pathology Multispectral Imaging System | AKOYA BIOSCIENCES | N/A |

Original raw data have been deposited in Mendeley Data (https://doi.org/10.17632/vbzbzhrw98.1).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Mice