Abstract

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) caused by physical impact to the brain can adversely impact the welfare and well-being of the affected individuals. One of the leading causes of mortality and dysfunction in the world, TBI is a major public health problem facing the human community. Drugs that target GABAergic neurotransmission are commonly used for sedation in clinical TBI yet their potential to cause neuroprotection is unclear. In this paper, I have performed a rigorous literature review of the neuroprotective effects of drugs that increase GABAergic currents based on the results reported in preclinical literature. The drugs covered in this review include the following: propofol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, isoflurane, and other drugs that are agonists of GABAA receptors. A careful review of numerous preclinical studies reveals that these drugs fail to produce any neuroprotection after a primary impact to the brain. In numerous circumstances, they could be detrimental to neuroprotection by increasing the size of the contusional brain tissue and by severely interfering with behavioral and functional recovery. Therefore, anesthetic agents that work by enhancing the effect of neurotransmitter GABA should be administered with caution of TBI patients until a clear and concrete picture of their neuroprotective efficacy emerges in the clinical literature.

Keywords: GABA, traumatic brain injuries (TBI), propofol, isoflurane, neuroprotection

Introduction

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are a major public health problem both in India (1) and the United States (2). Physical injury to the brain in numerous forms can cause TBI and this may lead to the death of neurons and other cells in the affected region ultimately resulting in loss of function (3). TBI can potentially lead to the development of long-term neurological, and psychiatric problems in the affected individuals (4–6). Therefore, TBI and associated co-morbidities could severely disrupt the quality of life of the affected individuals hindering their ability to function independently (5).

Being one of the major causes of death and dysfunction in the United States, the number of individuals living with TBI-related ailments is 5.3 million and it is estimated that the number of people who die from TBI-related complications is around 50,000 annually in the United States (2). Due to the medical complications that one could face post head injury, TBI could potentially stress the healthcare systems and impose a hefty financial burden. The average cost of treating individuals affected by TBI is estimated to be around $50 billion annually in the United States (2). In India, the incidence of TBI is 1.6 million annually based on epidemiological data (1). Additionally, death due to head injury accounts for 200,000/year, and about 1 million will need access to rehabilitation services (1). Therefore, TBI and associated complications create a huge socioeconomic burden.

Neuronal damage after TBI can be attributed to primary and secondary injuries each employing a distinct set of pathophysiological mechanisms (7, 8). Primary injury is due to the death of neurons, non-neurons, and blood vessels at the site of physical impact leading to energy deficiency (7). On the other hand, secondary injury could happen over days, months, or even years after a primary traumatic impact. Secondary brain injury is due to a complex set of signaling cascades and mechanisms that ultimately result in membrane depolarization, excitotoxicity, and activation of pathways leading to programmed cell death (7). While the loss of tissue due to primary brain injury is generally irreversible, secondary brain injuries can be prevented by administering the right therapeutic interventions immediately after the primary injury. Termed “golden hours,” the first (9, 10) few hours post TBI when the post-traumatic excitotoxicity reaches the peak, is crucial for causing neuroprotection, reducing secondary brain injuries, and aiding long-term functional recovery. Therefore, therapeutic interventions for TBI might need to target this crucial time frame in order to achieve maximal efficacy. Unfortunately, numerous clinical trials in quest for an effective neuroprotective agent in TBI have failed and there is no cure (11) till date which can be partly attributed to the heterogeneity of injury types in TBI (12, 13). However, robust clinical care and patient management post TBI could reduce the damage inflicted by secondary brain injuries and offer valuable neuroprotection to the affected individuals.

TBI patients need to go through anesthesia for various reasons such as prevention of seizures, pharmacological sedation, and surgery (14, 15). In clinical TBI, sedation through drugs still remains the first line of treatment to prevent further complications, normalize intracranial pressure (ICP), and reduce metabolic demand (14, 16). Generally, the choice of anesthetic agents is decided by the treating physician based on the drug's hemodynamic factors, its ability to reduce ICP, cerebral metabolic rate, and the drug's potential to cause short-term and long-term side effects (15, 17, 18). Unfortunately, one factor that is often under-emphasized while selecting an anesthetic agent in clinical TBI is the ability of the drug to prevent cell death and reduce histological damage. This could be due to the lack of drug efficacy data in the clinical literature and ethical concerns about experimentation on humans. There are several pre-clinical animal research studies that state that the choice of anesthetic agents could affect the extent of secondary injuries post TBI (19–23). Such animal studies could come to the rescue and offer valuable data on the ability of various drugs used as anesthetic agents in clinical TBI to cause neuroprotection.

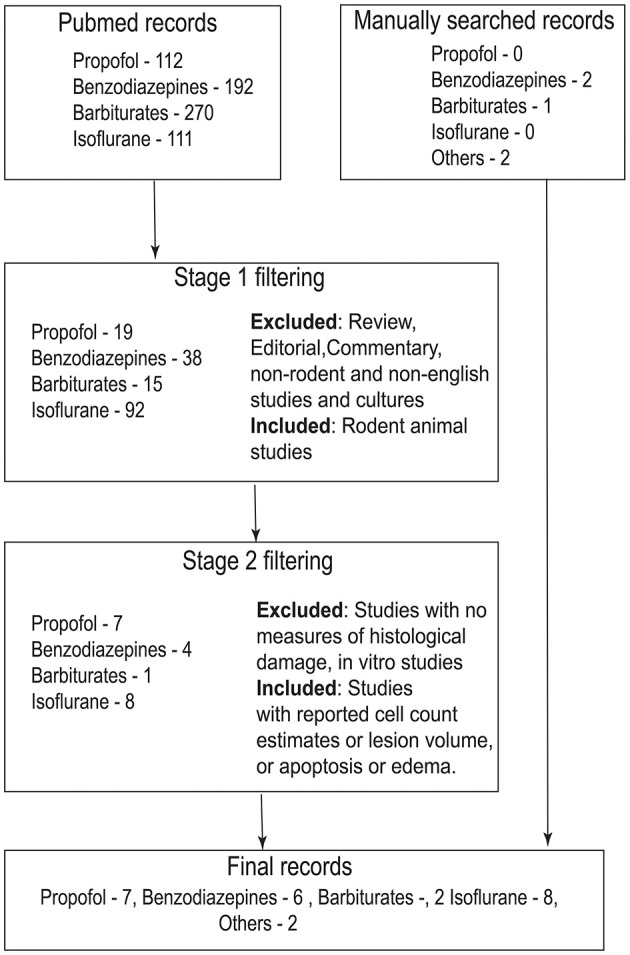

Here, in this study, I have reviewed the neuroprotective efficacy of a specific class of drugs that augment GABAergic neurotransmission (GABAA receptor agonists) from preclinical animal research studies. GABAAR agonists are commonly employed as anesthetic agents in clinical TBI owing to their safety profile and anti-epileptic efficacy (3, 16, 18, 24). After performing an exhaustive literature search, only studies that reported direct metrics on histopathological damage or edema were included in the review (Figure 1). TBI studies that measure the effect of GABAergic drugs on neuroinflammation were excluded from this review because inflammation may not always be neurotoxic and may even be useful especially in the acute stages following TBI (25–29).

Figure 1.

Flowchart that describes search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study. Records were searched in PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using the search term “traumatic brain injury” + drug name (For example, the search term for propofol would be traumatic brain injury propofol). In stage 1, abstract of the records were screened. Only rodent animal studies were included in this stage. Non-rodent studies, reviews, commentaries, editorials and non-English articles were excluded. In stage 2, full text of the articles were screened according to the inclusion criteria mentioned in the figure. Records that have passed through stage 2 filtering along with manually cross-referenced records were included in the manuscript.

Based on the data available in the pre-clinical studies, I find that GABAAR agonists not only fail to offer neuroprotection but also can impede functional recovery post TBI. Clinical trials need to be conducted to study the potentially deleterious effects of GABAAR agonists, especially in severe TBI cases. Until a clear picture emerges about the neuroprotective properties of GABAAR agonists in clinical TBI, one might need to avail caution and consult the efficacy data available in the scientific literature of pre-clinical animal studies.

Propofol

Propofol is one of the widely used anesthetic agents in clinical TBI owing to its relatively well-documented safety profile, quick time scale of action and well-established neurophysiological mechanisms (14). Propofol exerts its action by augmenting the activity of chloride currents through GABAARs and also blocks voltage-gated sodium channels (14, 30). However, several preclinical TBI studies (19, 31–34) have highlighted the inefficacy of propofol in causing neuroprotection and promoting functional recovery.

In a study that quantified the neuroprotective efficacy of different drugs commonly used as anesthetics in clinical TBI, the authors report that the application of propofol post controlled cortical impact (CCI) in rats did not have any effect on the lesion volume and the number of remaining CA1 neurons in the hippocampus of the injured brain (19). Also, propofol administration impaired the recovery of motor function measured by beam balance test during the first few days after TBI. Further, propofol did not have any effect on cognitive function outcome measured using the Morris water maze (MWM) test at 14–18 days post injury. In another study, propofol treatment at 24-h post CCI in rats increased the injury size and impaired motor function outcome at 30 days post injury (32). Thal et al. (31) employing the same method (CCI) for inducing TBI have shown that propofol not only had a null effect on the lesion size post TBI but also impaired the extent of functional recovery and reduced neurogenesis. A similar result was also reported in another study (33) where propofol infusion didn't have any effect on lesion volume and eosinophilic cell count in the hippocampus both at low or high doses post CCI in rats.

Even though the above studies have established the potentially detrimental effect of propofol on neuroprotection through animal experiments, there are a few reports in the literature that state that propofol could cause neuroprotection especially when applied prior to TBI. In a study (35) that involved fluid percussion injury (FPI) in rats, propofol treatment prior to TBI significantly reduced the lesion volume and promoted functional recovery. Similar effects of propofol could be seen in a study (36) where the drug was administered soon after (10 min) inflicting TBI to animals through CCI. Additionally, propofol administered at various time points post TBI reduced cell death in the surrounding regions that received primary impact (37).

Therefore, one may be of the opinion that purely from a neuroprotection perspective in reducing lesion size and inducing functional recovery, propofol might not be helpful and could potentially be detrimental especially when applied post TBI in experimental animals (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of preclinical studies involving drugs that target GABAergic neurotransmission in TBI.

| Drug | Injury model and animal groups | Drug administration timeline | Effect on histological outcome and functional recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propofol (19) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 9 for each experimental drug group (diazepam, fentanyl, morphine, isoflurane, ketamine, pentobarbital, ketamine, no anesthesia and sham) |

Drug administration for 1-h post TBI. | No effect on histological outcome (lesion volume and surviving hippocampal neurons measured at 21 days post TBI). Propofol administration affected motor function recovery (first 5 days post TBI) but had no effect on cognitive recovery (14–20 days post TBI). |

| Propofol (32) | CCI C57BL/6 mice n = 10 for each group (propofol at 6 or 24-h and vehicle or saline) |

Single bolus of propofol administration post TBI (6–24-h). | Increased lesion volume observed at 72-h post CCI in the propofol treated cohort. Propofol administration impaired recovery of locomotor function (gait analysis at 30 days post TBI). |

| Propofol (31) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 10–17 for each group. Groups tested were sham (low and high dose) and CCI (low and high dose) |

Drug administration during (for 2-h, 30 min before and 90 min after) or post TBI (for 3-h at 2-h post injury). | Propofol had no effect on the lesion size (28 days post insult). Propofol impaired recovery of neurological function at 28 days post insult in a dose-dependent manner. |

| Propofol (33) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 9–10 for each group. Groups tested were CCI (propofol high and low dose), CCI (halothane) and sham |

Drug administered post TBI for 6-h. | Propofol (at both doses) did not exert any effect on the lesion volume and eosinophilic cell count in the hippocampus (at 6-h post insult). |

| Propofol (35) | FPI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 6–8 for each group. Groups tested were FPI (propofol and isoflurane) and sham |

Continuous propofol infusion before TBI induction. | Propofol decreased the lesion volume (at 28 days post TBI induction) compared to isoflurane anesthesia. Propofol aided the recovery of cognitive function in novel object recognition task at 21 days post TBI. |

| Propofol (36) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats TBI + drug (n = 10) TBI + no drug (n = 10) Sham + saline (n = 8) No TBI + drug (n = 10) |

Intra-peritoneal injection given at 10 min post TBI. | Propofol reduced formation of cerebral edema (estimated at 12-h post TBI). |

| Propofol (37) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 9 for each of the seven experimental groups as mentioned in the paper |

Propofol delivered at 1, 2, and 4-h post TBI through intra-peritoneal injection and followed by 2-h infusion. | Propofol reduced cell death in the peri-contusional cortex at 24-h post CCI. |

| Diazepam (19) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 9 for each experimental drug group (diazepam, fentanyl, morphine, isoflurane, ketamine, pentobarbital, ketamine, no anesthesia and sham) |

Drug administration for 1-h post TBI. | No effect on histological outcome by diazepam (lesion volume and surviving hippocampal neurons) at 21 days post TBI. Diazepam administration affected cognitive recovery assessed through MWM test at 14–20 days post TBI. |

| Diazepam (38) | CCI C57BL/6J mice TBI + drug (n = 13) TBI + vehicle (n = 13) Sham + drug (n = 14) Sham + vehicle (n = 12) |

Continuous drug infusion for 1-week post TBI through an osmotic pump. | Diazepam did not have any effect on tissue loss or number of degenerating cells at 3 days post injury. |

| Midazolam (39) | CCI C57BL/6 mice n = 9–11 for each group (TBI + saline, TBI + low dose midazolam, TBI + high dose midazolam and TBI + high dose midazolam + flumazenil) |

Single point drug administration at 24-h post TBI. | Midazolam did not have any effect on the lesion volume measured at 72-h post TBI. Midazolam impaired neurological recovery assessed through NSS score (40) at 72-h post injury. |

| Diazepam (22) | Electrolytic lesion. Long Evans hooded rats n = 16 for TBI group and n =8 for sham group. In each group half of the animals were undrugged. |

Drug administration at 10–12-h post TBI and continued till 22 days (intra-peritoneal injection). | Diazepam had no effect on the lesion size. Diazepam impaired recovery from sensory asymmetry as long as 22 days post injury. |

| Diazepam (41) | Electrolytic lesion. Long Evans hooded rats n = 9 and 7 for TBI (anterior-medial neocortex) groups receiving diazepam and vehicle, respectively. n = 9 and 9 for TBI (sensorimotor neocortex) groups receiving diazepam and vehicle, respectively. N =14 for sham operated animals |

Drug administration at 10–12-h post TBI and continued till 21 days (intra-peritoneal injection). | Increased atrophy of the striatum and cell death in the substantia nigra pars reticulata was observed in diazepam treated injured (anterior-medial cortex) animals. Diazepam treatment impaired recovery from sensorimotor asymmetry as long as 91 days post injury following anterior-medial cortical lesion. |

| Diazepam (42) | Central FPI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 8 each for TBI + diazepam, TBI + saline and sham operated controls (pretreatment). For post-treatment, n = 6 for TBI + diazepam and n = 5 for TBI + saline. |

Drug administration at 15 min prior or post TBI induction (intra-peritoneal injection) | Rats that were subjected to diazepam pretreatment had reduced mortality rates. Both pre and post treatment with diazepam assisted in cognitive recovery assessed through MWM test at 10–15 days post TBI. |

| Pentobarbital (19) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 9 for each experimental drug group (diazepam, fentanyl, morphine, isoflurane, ketamine, pentobarbital, ketamine, no anesthesia and sham) |

Drug administration for 1-h post TBI. | No effect on histological outcome after pentobarbital administration at 21 days post TBI. Pentobarbital did not help in recovery of motor or cognitive function assessed at various time points post TBI. |

| Phenobarbital (23) | Electrolytic lesion. Long Evans hooded rats for three groups: TBI + low dose (n = 3), TBI + high dose (n = 4) and TBI + NaCl (n = 6) |

Drug administration (2 times a day) at 48-h for up to 7 days post TBI (intra-peritoneal injection). | Phenobarbital treatment did not have any effect on the lesion volume. Phenobarbital treatment impaired recovery from sensorimotor asymmetry as long as 45 days post injury (no dose-dependency noticed). |

| Isoflurane (19) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 9 for each experimental drug group (diazepam, fentanyl, morphine, isoflurane, ketamine, pentobarbital, ketamine, no anesthesia and sham) |

Drug administration for 1-h post TBI. | Isoflurane administration led to better hippocampal neuronal survival rates at 21 days post TBI. Isoflurane resulted in recovery of cognitive function assessed by MWM test at 14–20 days post TBI. |

| Isoflurane (21) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 9 for each experimental drug group (isoflurane and fentanyl) and (n = 6) for each sham anesthetic group |

Continuous drug administration before TBI and continued till 3.5–4-h post TBI. | Isoflurane resulted in better hippocampal neuronal survival rates (estimated at 21 days post TBI) compared to fentanyl although edema and ICP were similar. Isoflurane resulted in superior motor (1–5 days) and cognitive function recovery (14–20 days) compared to fentanyl. |

| Isoflurane (43) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats n = 9 for each group tested (isoflurane, fentanyl and recovery with no anesthesia) |

Continuous drug administration before TBI and continued till 1-h post TBI. | Compared to fentanyl, isoflurane resulted in better hippocampal neuronal survival rates (21 days post injury). Isoflurane resulted in better functional recovery compared to fentanyl (1–20 days post injury). |

| Isoflurane (20) | CCI C57BL/6N mice n = 6 for each group tested [isoflurane, sevoflurane and combo (midazolam, fentanyl, medetomidine)]. Two such cohorts were utilized for histology at 15 min and 24-h post TBI |

Continuous anesthesia initiated before TBI and stopped right after injury induction. | Isoflurane resulted in reduced contusional volume measured at 24-h post injury. Isoflurane also resulted in better recovery of neurological function measured by NSS test (40) at 24-h post TBI. |

| Isoflurane (44) | CCI C57BL/6J mice receiving avertin (n = 78) and isoflurane (n = 57) anesthesia |

Animals received a single impact or 2–3 repeated impacts with 48-h gap. Anesthesia applied prior to surgery. | Isoflurane resulted in reduced axonal injury compared to avertin anesthesia at 24-h post TBI. |

| Isoflurane (45) | CCI Rats TBI + short anesthesia (n = 20) TBI + long anesthesia (n = 30) |

Short anesthesia for 30 min (at 7.5-h post TBI) and longer anesthesia for 4 (at 4-h post TBI) hours was administered. | Prolonged anesthesia resulted in higher edema formation immediately after injury. |

| Isoflurane (46) | CCI C57BL/6J mice n = 7 for each group mentioned below: CCI + isoflurane CCI + sevoflurane Sham + isoflurane Sham + sevoflurane |

Anesthesia was started prior to CCI and continued for 15–20 min during injury induction. | Edema formation was higher in isoflurane treated animals compared to sevoflurane at 24-h post TBI. |

| Isoflurane (47) | CCI Sprague-Dawley rats CCI + isoflurane (normal sedation, n = 12) CCI + isoflurane (deep sedation, n = 12) |

Anesthesia was maintained for 2-h prior to CCI. | Deep anesthesia resulted in increased neurodegeneration and poor functional performance estimated at 48-h post TBI. |

| Topiramate (48) | Lateral FPI Sprague-Dawley rats TBI + drug (n = 35) TBI + saline (n = 25) Sham + drug (n = 21) Sham + saline (n = 26) |

Drug given at 30 min, 8, 20 and 32-h post TBI (intra-peritoneal injection). | Topiramate did not have any effect on the volume of the contusional tissue (1-month post TBI) and edema formation (48-h post TBI). Topiramate resulted in better recovery of motor function (4 weeks post TBI) but affected cognitive learning (4 weeks post TBI). |

| Vigabatrin (49) | Electrolytic lesion. Long–Evans hooded rats. n = 7, 9, 8, 11, respectively for brain injured animals receiving low, medium, high drug dose and saline. n = 9, 9, 9, 10, respectively for sham animals receiving low, medium, high drug dose and saline |

Drug given at 48-h post TBI and continued for 7 days (intra-peritoneal injection). | Vigabatrin treatment did not have any effect on the lesion volume. Vigabatrin did not have any effect on recovery of sensory function post TBI (assessed up to 60 days post injury). |

The table includes the model of TBI induction, drug administration timeline, and experimental groups along with the reported histopathological outcomes and effect on functional recovery.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are a group of drugs that potentiate GABAergic neurotransmission (14, 50). They do so by acting on GABAARs and thereby mediate sedative effects and anti-epileptic action (50). Benzodiazepines are commonly used as anesthetic/sedative agents in clinical TBI and also in the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, and seizures (14, 18, 50). By binding to the benzodiazepine receptor on the GABAARs, these drugs potentiate the effect of GABA by inducing a conformational change on the receptor (50). Though known to reduce ICP and metabolic demand (14), benzodiazepines have been documented to be deleterious for neuroprotection and known to impede the extent of functional recovery in experimental TBI (19, 22, 39, 41).

Statler et al. (19) have reported that the application of diazepam post CCI in rats did not have any impact on the contusional size and number of the surviving neurons in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Also, animals treated with diazepam exhibited poor cognitive functioning in the MWM test. In another study (39), midazolam application at 24-h post injury in rats interfered with functional recovery and did not have any effect on the lesion size both measured at 72-h post injury. Diazepam application following a lesion to the neocortex (22) impaired recovery of sensory asymmetry as long as 22 days post injury and this delay to behavioral recovery was prevented by the application of benzodiazepine antagonist Ro 15-1788 (51). In a similar experiment (41), the application of diazepam following anteromedial cortical lesions resulted in impaired functional recovery, increased atrophy of the striatum, and cell death in the substantia nigra pars reticulata. Further, systematic application of flumazenil (at 24-h post injury), a benzodiazepine antagonist improved cognitive performance in MWM task in CCI-injured immature animals (52). Finally, diazepam did not have any effect on cortical tissue loss and the number of degenerating cells (determined by Fluoro-Jade C staining) at 3 days post TBI (38).

Similar to propofol, benzodiazepines application prior to TBI could produce beneficial effects with respect to neuroprotection. In a study (42) that involved injuring rats by the FPI method, animals that received diazepam 15 min prior to the injury were characterized by reduced mortality rate and improvement in functional recovery. However, rats treated with the drug 15 min post FPI, did not exhibit any significant difference in the mortality rate compared to saline-treated animals. For this reason, the timing of diazepam application could play a vital role in neuroprotection and functional recovery post TBI at least in experimental animals (Table 1).

Barbiturates

Barbiturates are a class of drugs that potentiate post-synaptic GABAergic currents and are hence regarded as GABAAR agonists (53). This results in increased hyperpolarization of neurons due to an enhanced influx of chloride ions. Also, barbiturates result in the inhibition or blocking of AMPA receptors (14). Barbiturates include drugs such as phenobarbital, thiopental, pentobarbital, methohexital, etc. (53). In experimental TBI, the use of barbiturates post injury has been reported to worsen the injury and impede the pace of behavioral and functional recovery (19, 23). For example, the application of pentobarbital post TBI in rats resulted in no change to lesion volume similar to the effect of some of the other commonly used drugs for anesthesia (19). Additionally, the use of phenobarbital, a barbiturate, post anteromedial lesion to the cortex resulted in delayed behavioral recovery of up to 4 weeks compared to saline-treated animals (23). Therefore, the use of barbiturates could result in impaired functional recovery and may fail to confer neuroprotection benefits similar to the effect of other GABAAR agonists.

Isoflurane

In contrast to the above-mentioned anesthetic agents, isoflurane finds a rare usage in clinical TBI while used extensively in animal research experiments (19). Isoflurane is a volatile anesthetic (54) and several reports from preclinical TBI experiments indicate that isoflurane could be neuroprotective (19–21, 43). In an experiment (19) involving the CCI method of brain injury, isoflurane resulted in better cognitive recovery of rats in the MWM task and also caused better survival rates of CA1 hippocampal neurons. Similarly, in another study (21), rats treated with isoflurane exhibited better performance in motor and cognitive tasks and had significantly reduced secondary damage in the hippocampus. The authors postulated that the neuroprotective effect of isoflurane could be mediated as a result of increased cerebral blood flow and reduced excitotoxicity caused by the anesthetic but the drug had little effect on reducing ICP. In another experiment (43) which compares the anesthesia induced neuroprotective effects of isoflurane and fentanyl, animals treated with isoflurane exhibited significant neuroprotection in terms of the surviving CA3 hippocampal neurons and scored better in functional recovery. Luh et al. compared the effect of 15-min anesthesia in CCI-injured rats and reported that animals treated with isoflurane were characterized by reduced contusional volume and better functional recovery as measured by neurological severity score (20). In a study that involved mild TBI induction by CCI, isoflurane anesthesia resulted in reduced axonal injury (44). Although the above studies indicate a beneficial effect of isoflurane, prolonged isoflurane exposure or deep sedation (47) is reported to cause increased edema (water content) formation post TBI (45, 46).

One of the proposed reasons for isoflurane's neuroprotection could be the drug's multifaceted mechanism of action. Isoflurane counters excitotoxicity by inhibiting glutamate release (54), blocking voltage-gated sodium channels (55) and glutamate receptors (56), prevents calcium (56) entry by blocking NMDA receptors, and maintains perfusion by increasing the cerebral blood flow (21, 57) in addition to its known mechanism of augmenting GABAergic currents. Therefore, based on the results from above-mentioned scientific studies (Table 1), isoflurane could act as a better neuroprotective agent compared to other drugs that act on GABAA receptors although its efficacy in humans remains to be determined.

Other drugs

Two other drugs that augment chloride currents through GABAARs are topiramate (58) and vigabatrin (49). Though not used as an anesthetic agent in clinical TBI, both these drugs are well-known for their anti-epileptic efficacy and used widely for controlling seizures (49, 58). Topiramate is a relatively new anti-epileptic drug and acts by potentiating GABAergic neurotransmission, blocking voltage-gated sodium channels, and also acts as an antagonist of AMPA receptors (58). Topiramate applied at various time points post TBI was not effective in reducing edema and did not have any effect on histopathological damage and CA3 cell counts (48). Vigabatrin, a drug that potentiates GABAergic neurotransmission by inhibiting GABA-T (GABA-Transaminase) did not have any effect on the recovery of sensory function post TBI in rats (49).

Bolstering the above-mentioned studies, the application of GABA itself to the injured brain tissue delayed recovery to function in an animal model of hemiplegia (59). Additionally, the application of muscimol, a GABAAR agonist, to the brain region (sensorimotor cortex) adjacent to lesion in the anteromedial cortex impacted the long-term recovery of behavioral function (60). Also, the application of pentylenetetrazol (61) a GABAAR antagonist following unilateral lesions to the sensorimotor cortex of rats promoted recovery of the functional deficits created by the injury. Therefore, drugs that potentiate GABAergic neurotransmission might not exert neuroprotective benefits and may impair functional recovery post TBI in animal studies.

Discussion

Even though numerous animal studies have recorded the deleterious effect of GABAergic drugs on neuroprotection, it should be noted that these agents are some of the commonly utilized drugs for sedation in clinical TBI (14, 62). Propofol is widely used for sedation in TBI patients owing to its well-established safety profile and effect on reducing ICP (14, 62). Next to propofol, benzodiazepines find their application extensively in clinical TBI (prior to the advent of propofol) owing to their ability to increase the seizure threshold and reduce ICP (14). Although benzodiazepines are associated with delirium, refractoriness, and withdrawal effects, it is no different (midazolam) from propofol with respect to its effect on hemodynamic variables (14, 63). Propofol is known for faster wake-up times and better quality of sedation (14, 63).

Barbiturates, once used for pharmacological sedation in clinical TBI cases are now replaced by other drugs like propofol (64, 65) owing to their adverse side effects. However, the Brain Trauma Foundation (BTF) (66) recommends the use of barbiturates for the management of refractory increased ICP in clinical TBI even though there have been reports of uncontrolled ICP (67, 68) and hypotension (67) by this class of drugs. In a retrospective study of trauma patients (69), the use of barbiturates within 24-h of hospital admission is associated with increased mortality. Hence, these drugs require very cautious application especially in severe cases of clinical TBI.

Isoflurane, though widely employed in preclinical TBI experiments, is rarely used in clinical TBI compared to other anesthetics (70). As mentioned in this review, isoflurane is found to be neuroprotective in a number of animal studies (19–21, 43). One of the reasons for sparse usage in clinical TBI is that isoflurane being a vasodilator may result in elevated ICP through its effect on cerebral blood flow (70, 71). In addition to that, the long-term effects of isoflurane treatment in the clinical TBI population is not well-documented in the literature (70). Concerns range from short-lived effects on cerebral injury (72) to little or no impact on functional recovery (73). Large, multi-center clinical trials on brain injury patients can help answer isoflurane's effect on neurological function over a longer time period. Other reasons could be specific to the use of volatile anesthetics such as issues with air pollution and the need for a specialized ventilating device (70, 71).

The reason for the poor efficacy of the drugs discussed in this study could be linked to changes in GABAergic neurotransmission in the posttraumatic brain. Almost all the drugs discussed in the study exert their action by interfering with neuronal GABAergic currents. The inhibitory action of the neurotransmitter GABA is mediated by chloride ions and is developmentally regulated (74–77). GABA is excitatory in immature neurons but its inhibitory action is restored during the course of development (75, 77). The inhibitory efficacy of GABA which depends on the concentration of intracellular chloride ions is controlled by the opposing action of two cation chloride transporters: NKCC1 and KCC2 (78). The expression levels of both these transporters vary across the development with NKCC1 transporters abundantly present in immature animals but their expression levels are greatly decreased in an adult brain (76). On the other hand, the expression of KCC2 is reduced at birth but increases during the post-natal developmental stages (76, 79).

Post TBI, changes in the expression levels of NKCC1 and KCC2 transporters have been reported in a number of preclinical studies (80–83). According to a study involving TBI in mice, the expression levels of NKCC1 co-transporters were upregulated until 24 hours post injury (80). Similar results depicting the upregulation of NKCC1 co-transporters were reported in a study that employed a closed head injury model (81) and weight drop method (82) to induce TBI in animals. Similarly, downregulation in the expression levels of KCC2 transporters has also been reported in the TBI literature (81, 83).

An immediate outcome of upregulation of NKCC1 and/or downregulation of KCC2 co-transporters post TBI is increased intracellular chloride levels leading to depolarized values of GABA (chloride) reversal potential. Confirming this theoretical observation, depolarized values of chloride reversal potential have been reported in numerous preclinical TBI studies (81, 83, 84). Therefore, GABA might cause paradoxical excitation (instead of inhibition) post TBI which might explain the inefficacy and possible detrimental effects of GABAAR agonists post TBI. A number of experimental studies (80–82, 85–88) and a recent computational study (89) have supported this hypothesis for the relative inefficacy of GABA post TBI. In these studies, blocking NKCC1 co-transporters by a drug called Bumetanide, a diuretic, caused neuroprotection and reduced edema formation in the brain. Also, pairing GABAAR agonists with Bumetanide might restore the inhibitory efficacy of GABA in post-traumatic brain states (89, 90). In addition to TBI, Bumetanide has been shown to reinstate the inhibitory action of GABA in other pathological brain conditions (91–93).

Another potential mechanism that could explain the adverse effects of GABA and GABAergic drugs post brain trauma is the depolarizing gradients exerted by bicarbonate ions (89, 94, 95). GABAA receptors conduct not only chloride ions but also bicarbonate ions with the latter contributing to about 20% relative permeability (96). Regeneration of bicarbonate gradients is firmly controlled by pH buffers (97). However, when bicarbonate resting gradients were allowed to break down either experimentally (94) or in a computational model (89), the GABA mediated depolarization was reduced significantly suggesting a potential role for bicarbonate signaling in this process.

Changes in the subunit composition of GABAA receptors post TBI could also contribute toward the neuroprotective inefficacy of GABAergic drugs (98, 99). In experimental TBI, changes in the expression pattern of GABAA receptor subunits have been reported at various time points following injury (98, 99). Furthermore, calcium-dependent enhancement of GABAergic currents following trauma (100) in conjunction with depolarizing chloride gradients discussed above could partly explain the deleterious effect of GABAergic drugs post TBI. Lastly, decreased binding capacity of GABAA receptors (101), extensive dendritic damage and spines leading to loss of receptors (102) could potentially reduce the therapeutic efficacy of GABAergic drugs following brain trauma.

In contrast to the reported neuroprotective inefficacy of GABAergic drugs in TBI, dexmedetomidine (Dex), a novel drug that works as an agonist of α2–adrenoreceptor (103) has shown to be neuroprotective in numerous animal studies (40, 104–109). For example, Dex has been shown to reduce neurodegeneration following CCI in mice (104, 107). Similar effects of Dex on brain edema were reported in other preclinical animal studies (40, 105, 106, 108, 109). This could be because of the fact that Dex hyperpolarizes neurons not by targeting GABAergic neurotransmission but through other means (acting on inwardly rectifying potassium channels) (103).

It's worthwhile to bring to the attention of the readers that results from TBI animal experiments may not always produce the same effect in humans (110). Even though preclinical studies have documented the therapeutic efficacy of numerous drugs for neuroprotection, disappointing results have been observed in Phase III clinical trials (110). For example, progesterone was shown to exhibit therapeutic and functional benefits in animal studies (111), but clinical trials of the drug on humans have failed to yield any significant effect (112). Therefore, the application of the results of this review in clinical TBI might have its own limitations given the poor success rate of replication of TBI animal studies on humans. Nevertheless, this study could be used as a motivation factor for more research to gain an increased understanding of the effects of GABAergic drugs in clinical TBI.

Conclusion

A careful review of preclinical TBI literature has highlighted the inefficacy and possible anti-neuroprotective action of some of the anesthetic agents that augment GABAergic currents and are commonly used in clinical TBI. With the exception of isoflurane, all other anesthetic agents that augment GABAergic neurotransmission might not cause neuroprotection and, in many cases, could be detrimental to it and may impede functional recovery. Changes in the expression patterns of chloride transporters post TBI could be a possible reason behind the unexpected action of such drugs. Until a better understanding emerges about their neuroprotective efficacy in humans, adequate care should be exercised for their application in clinical TBI.

Author contributions

SKS conceptualized the research topic, performed literature search and analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Satvika Char, Shreya Sridhar, and Kathan Pandya for careful reading and comments on the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by faculty grant from Krea University.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Gururaj G. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries: Indian scenario. Neurol Res. (2002) 24:24–8. 10.1179/016164102101199503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. (2006) 21:375–8. 10.1097/00001199-200609000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. (2008) 7:728–41. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shoumitro D, Lyons I, Koutzoukis C, Ali I, Mccarthy G. After traumatic brain injury. AM J Psychiatry. (1999) 156:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks N, Campsie L, Symington C, Beattie A, McKinlay W. The five year outcome of severe blunt head injury: a relative's view. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1986) 49:764–70. 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hibbard MR, Bogdany J, Uysal S, Kepler K, Silver JM, Gordon W, et al. Axis II psychopathology in individuals with traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. (2000) 13:45–61. 10.1080/0269905001209161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth. (2007) 99:4–9. 10.1093/bja/aem131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Algattas H, Huang JH. Traumatic brain injury pathophysiology and treatments: early, intermediate, and late phases post-injury. Int J Mol Sci. (2013) 15:309–41. 10.3390/ijms15010309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinh MM, Bein K, Roncal S, Byrne CM, Petchell J, Brennan J. Redefining the golden hour for severe head injury in an urban setting: the effect of prehospital arrival times on patient outcomes. Injury. (2013) 44:606–10. 10.1016/j.injury.2012.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampalis JS, Lavoie A, Williams JI, Mulder DS, Kalina M. Impact of on-site care, prehospital time, and level of in-hospital care on survival in severely injured patients. J Trauma. (1993) 34:252–61. 10.1097/00005373-199302000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Emerging treatments for traumatic brain injury. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. (2009) 14:67–84. 10.1517/14728210902769601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saatman KE, Duhaime A-C, Bullock R, Maas AIR, Valadka A, Manley GT. Classification of traumatic brain injury for targeted therapies. J Neurotrauma. (2008) 25:719–38. 10.1089/neu.2008.0586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maas A. Traumatic brain injury: changing concepts and approaches. Chin J Traumatol. (2016) 19:3–6. 10.1016/j.cjtee.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flower O, Hellings S. Sedation in traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med Int. (2012) 2012:1–11. 10.1155/2012/637171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armitage-Chan EA, Wetmore LA, Chan DL. Anesthetic management of the head trauma patient. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. (2007) 17:5–14. 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2006.00194.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peluso L, Lopez BM, Badenes R. Sedation in TBI patients. In:Zhou Y, editor. Traumatic Brain Injury. Rijeka: IntechOpen; (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, Riker RR, Fontaine D, Wittbrodt ET, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. (2002) 30:119–41. 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ripley DL, Driver S, Stork R, Maneyapanda M. Pharmacologic management of the patient with traumatic brain injury. In: Rehabilitation After Traumatic Brain Injury. Elsevier: (2019). p. 133–63. 10.1016/b978-0-323-54456-6.00011-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statler KD, Alexander H, Vagni V, Dixon CE, Clark RSB, Jenkins L, et al. Comparison of seven anesthetic agents on outcome after experimental traumatic brain injury in adult, male rats. J Neurotrauma. (2006) 23:97–108. 10.1089/neu.2006.23.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luh C, Gierth K, Timaru-Kast R, Engelhard K, Werner C, Thal SC. Influence of a brief episode of anesthesia during the induction of experimental brain trauma on secondary brain damage and inflammation. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e19948. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statler KD, Kochanek PM, Dixon CE, Alexander HL, Warner DS, Clark RSB, et al. Isoflurane improves long-term neurologic outcome versus fentanyl after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. (2000) 17:1179–89. 10.1089/neu.2000.17.1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schallert T, Hernandez TD, Barth T. Recovery of function after brain damage : severe and chronic disruption by diazepam. Brain Res. (1986) 379:104–11. 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90261-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez TD, Holling LC. Disruption of behavioral recovery by the anti-convulsant phenobarbital. Brain Res. (1994) 635:300–6. 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91451-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein LB. Prescribing of potentially harmful drugs to patients admitted to hospital after head injury. J NeurolNeurosurgPsychiatry. (1995) 58:753–5. 10.1136/jnnp.58.6.753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ransohoff RM. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science. (2016) 353:777–83. 10.1126/science.aag2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izabela Figiel. Pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α as a neuroprotective agent in the brain. Acta Neurobiol Exp. (2008) 68:526–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson NG, Wieggel WA, Chen J, Bacchi A, Rogers SW, Gahring LC. Inflammatory Cytokines IL-1, IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-impart neuroprotection to an excitotoxin through distinct pathways 1. J Immunol. (1999) 163:3963–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.163.7.3963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morganti-Kossmann MC, Rancan M, Stahel PF, Kossmann T. Inflammatory response in acute traumatic brain injury: a double-edged sword. Curr Opin Crit Care. (2002) 8:101–5. 10.1097/00075198-200204000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon DW, McGeachy MJ, Baylr H, Clark RSB, Loane DJ, Kochanek PM. The far-reaching scope of neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. (2017) 13:171–91. 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouyang W, Wang G, Hemmings HC. Isoflurane and propofol inhibit voltage-gated sodium channels in isolated rat neurohypophysial nerve terminals. Mol Pharmacol. (2003) 64:373–81. 10.1124/mol.64.2.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thal SC, Timaru-Kast R, Wilde F, Merk P, Johnson F, Frauenknecht K, et al. Propofol impairs neurogenesis and neurologic recovery and increases mortality rate in adult rats after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. (2014) 42:129–41. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a639fd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sebastiani A, Granold M, Ditter A, Sebastiani P, Gölz C, Pöttker B, et al. Posttraumatic propofol neurotoxicity is mediated via the pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor-p75 neurotrophin receptor pathway in adult mice. Crit Care Med. (2016) 44:e70–82. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eberspächer E, Heimann K, Hollweck R, Werner C, Schneider G, Engelhard K. The effect of electroencephalogram-targeted high- and low-dose propofol infusion on histopathological damage after traumatic brain injury in the rat. Anesth Analg. (2006) 103:1527–33. 10.1213/01.ane.0000247803.30582.2d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Firdaus R, Theresia S, Austin R, Tiara R. Propofol effects in rodent models of traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Asian Biomed. (2021) 15:253–65. 10.2478/abm-2021-0032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo T, Wu J, Kabadi SV, Sabirzhanov B, Guanciale K, Hanscom M, et al. Propofol limits microglial activation after experimental brain trauma through inhibition of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase. Anesthesiology. (2013) 119:1370–88. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding Z, Zhang J, Xu J, Sheng G, Huang G. Propofol administration modulates AQP-4 expression and brain edema after traumatic brain injury. Cell Biochem Biophys. (2013) 67:615–22. 10.1007/s12013-013-9549-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Y, Jian MY, Wang YZ, Han RQ. Propofol ameliorates calpain-induced collapsin response mediator protein-2 proteolysis in traumatic brain injury in rats. Chin Med J. (2015) 128:919–27. 10.4103/0366-6999.154298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villasana LE, Peters A, McCallum R, Liu C, Schnell E. Diazepam inhibits post-traumatic neurogenesis and blocks aberrant dendritic development. J Neurotrauma. (2019) 36:2454–67. 10.1089/neu.2018.6162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sebastiani A, Bender S, Schäfer MKE, Thal SC. Posttraumatic midazolam administration does not influence brain damage after experimental traumatic brain injury. BMC Anesthesiol. (2022) 22:1–10. 10.1186/s12871-022-01592-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang MH, Zhou XM, Cui JZ, Wang KJ, Feng Y, Zhang HA. Neuroprotective effects of dexmedetomidine on traumatic brain injury: involvement of neuronal apoptosis and HSP70 expression. Mol Med Rep. (2018) 17:8079–86. 10.3892/mmr.2018.8898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones TA, Schallert T. Subcortical deterioration after cortical damage: effects of diazepam and relation to recovery of function. Behav Brain Res. (1992) 51:1–13. 10.1016/S0166-4328(05)80306-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Dell DM, Gibson CJ, Wilson MS, DeFord SM, Hamm RJ. Positive and negative modulation of the GABA(A) receptor and outcome after traumatic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. (2000) 861:325–32. 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02055-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Statler KD, Alexander H, Vagni V, Holubkov R, Dixon CE, Clark RS, et al. Isoflurane exerts neuroprotective actions at or near the time of severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. (2006) 1076:216–24. 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Semple BD, Sadjadi R, Carlson J, Chen Y, Xu D, Ferriero DM, et al. Long-term anesthetic-dependent hypoactivity after repetitive mild traumatic brain injuries in adolescent mice. Dev Neurosci. (2016) 38:220–38. 10.1159/000448089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stover JF, Sakowitz OW, Kroppenstedt SN, Thomale UW, Kempski OS, Flügge G, et al. Differential effects of prolonged isoflurane anesthesia on plasma, extracellular, and CSF glutamate, neuronal activity, 125I-Mk801 NMDA receptor binding, and brain edema in traumatic brain-injured rats. Acta Neurochir. (2004) 146:819–29. 10.1007/s00701-004-0281-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thal SC, Luh C, Schaible EV, Timaru-Kast R, Hedrich J, Luhmann HJ, et al. Volatile anesthetics influence blood-brain barrier integrity by modulation of tight junction protein expression in traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e50752. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hertle D, Beynon C, Zweckberger K, Vienenkötter B, Jung CS, Kiening K, et al. Influence of isoflurane on neuronal death and outcome in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl. (2012) 114:383–6. 10.1007/978-3-7091-0956-4_74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoover RC, Motta M, Davis J, Saatman KE, Fujimoto ST, Thompson HJ, et al. Differential effects of the anticonvulsant topiramate on neurobehavioral and histological outcomes following traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. (2004) 21:501–12. 10.1089/089771504774129847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wallace AE, Kline AE, Montanez S, Hernandez TD. Impact of the novel anti-convulsant vigabatrin on functional recovery following brain lesion. Restor Neurol Neurosci. (1999) 14:35–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffin CE, Kaye AM, Rivera Bueno F, Kaye AD. Benzodiazepine pharmacology and central nervous system-mediated effects. Ochsner J. (2013) 13:214–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hernandez TD, Jones GH, Schallert T. Co-administration of Ro 15-1788 prevents diazepam-induced retardation of recovery of function. Brain Res. (1989) 487:89–95. 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90943-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ochalski PG, Fellows-Mayle W, Hsieh LB, Srinivas R, Okonkwo DO, Dixon CE, et al. Flumazenil administration attenuates cognitive impairment in immature rats after controlled cortical impact. J Neurotrauma. (2010) 27:647–51. 10.1089/neu.2009.1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skibiski J, Abdijadid S. Barbiturates. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel PM, Drummond JC, Cole DJ, Goskowicz RL. Isoflurane reduces ischemia-induced glutamate release in rats subjected to forebrain ischemia. Anesthesiology. (1995) 82:996–1003. 10.1097/00000542-199504000-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ouyang W, Hemmings HC. Depression by isoflurane of the action potential and underlying voltage-gated ion currents in isolated rat neurohypophysial nerve terminals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2005) 312:801–8. 10.1124/jpet.104.074609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bickler PE, Buck LT, Hansen BM. Effects of lsoflurane and hypothermia on glutamate receptor-mediated calcium influx in brain slices. Anesthesiology. (1994) 81:1461–9. 10.1097/00000542-199412000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lenz C, Rebel A, van Ackern K, Kuschinsky W, Waschke KF. Local cerebral blood flow, local cerebral glucose utilization, and flow-metabolism coupling during sevoflurane versus isoflurane anesthesia in rats. Anesthesiology. (1998) 89:1480–8. 10.1097/00000542-199812000-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perucca E. A pharmacological and clinical review on topiramate, a new antiepileptic drug. Pharmacol Res. (1997) 35:241–56. 10.1006/phrs.1997.0124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brailowsky S, Knight RT, Blood K, Scabini D. γ-Aminobutyric acid-induced potentiation of cortical hemiplegia. Brain Res. (1986) 362:322–30. 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90457-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hernandez TD, Schallert T. Long-term impairment of behavioral recovery from cortical damage can be produced by short-term GABA-agonist infusion into adjacent cortex. Restor Neurol Neurosci. (1990) 1:323–30. 10.3233/RNN-1990-1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hernandez TD, Schallert T. Seizures and recovery from experimental brain damage. Exp Neurol. (1988) 102:318–24. 10.1016/0014-4886(88)90226-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Urwin SC, Menon DK. Comparative tolerability of sedative agents in head-injured adults. Drug Saf. (2004) 27:107–33. 10.2165/00002018-200427020-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ronan KP, Gallagher TJ, George B, Hamby B. Comparison of propofol and midazolam for sedation in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. (1995) 23:286–93. 10.1097/00003246-199502000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sneyd JR. Thiopental to desflurane-an anaesthetic journey. Where are we going next? Br J Anaesth. (2017) 119:i44–52. 10.1093/bja/aex328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brown TCK. Thiopentone and its challengers. Paediatr Anaesth. (2013) 23:957–8. 10.1111/pan.12083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bratton SL, Chestnut RM, Ghajar J, McConnell Hammond FF, Harris OA, Hartl R, et al. XI. Anesthetics, analgesics, and sedatives. J Neurotrauma. (2007) 24: S71–6. 10.1089/neu.2007.9985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roberts I, Sydenham E. Barbiturates for acute traumatic brain injury. In:Roberts I, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pérez-Bárcena J, Llompart-Pou JA, Homar J, Abadal JM, Raurich JM, Frontera G, et al. Pentobarbital versus thiopental in the treatment of refractory intracranial hypertension in patients with traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. (2008) 12:1–10. 10.1186/cc6999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Léger M, Frasca D, Roquilly A, Seguin P, Cinotti R, Dahyot-Fizelier C, et al. Early use of barbiturates is associated with increased mortality in traumatic brain injury patients from a propensity score-based analysis of a prospective cohort. PLoS ONE. (2022) 17:e0268013. 10.1371/journal.pone.0268013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deng J, Lei C, Chen Y, Fang Z, Yang Q, Zhang H, et al. Neuroprotective gases - fantasy or reality for clinical use? Prog Neurobiol. (2014) 115:210–45. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Villa F, Iacca C, Molinari AF, Giussani C, Aletti G, Pesenti A, et al. Inhalation versus endovenous sedation in subarachnoid hemorrhage patients: effects on regional cerebral blood flow. Crit Care Med. (2012) 40:2797–804. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825b8bc6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kanbak M, Saricaoglu F, Avci A, Ocal T, Koray Z, Aypar U. Propofol offers no advantage over isoflurane anes-thesia for cerebral protection during cardiopul-monary bypass: a preliminary study of S-100ßprotein levels. Can J Anaesth. (2004) 51:712–7. 10.1007/BF03018431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Michenfelder JD, Sundt TM, Fode N, Sharbrough FW. Frank isoflurane when compared to enflurane and halothane decreases the frequency of cerebral ischemia during carotid endarterectomy. Anesthesiology. (1987) 67:336–40. 10.1097/00000542-198709000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ben-Ari Y, Cherubini E, Corradetti R, Gaiarsa JL. Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. (1989) 416:303–25. 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ben-Ari Y, Khalilov I, Kahle KT, Cherubini E. The GABA excitatory/inhibitory shift in brain maturation and neurological disorders. Neuroscientist. (2012) 18:467–86. 10.1177/1073858412438697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Plotkin MD, Snyder EY, Hebert SC, Delpire E. Expression of the Na – K – 2Cl cotransporter is developmentally regulated in postnatal rat brains : a possible mechanism underlying GABA's excitatory role in immature brain. J Neurobiol. (1997) 33:781–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kirmse K, Kummer M, Kovalchuk Y, Witte OW, Garaschuk O, Holthoff K, et al. depolarizes immature neurons and inhibits network activity in the neonatal neocortex in vivo. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:1–13. 10.1038/ncomms8750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Payne JA, Rivera C, Voipio J, Kaila K. Cation-chloride co-transporters in neuronal communication, development and trauma. Trends Neurosci. (2003) 26:199–206. 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00068-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lu J, Karadsheh M, Delpire E. Developmental regulation of the neuronal-specific isoform of K-Cl cotransporter KCC2 in postnatal rat brains. J Neurobiol. (1999) 39:558–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hui H, Rao W, Zhang L, Xie Z, Peng C, Su N, et al. Inhibition of Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransporter-1 attenuates traumatic brain injury-induced neuronal apoptosis via regulation of erk signaling. Neurochem Int. (2016) 94:23–31. 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang F, Wang X, Shapiro LA, Cotrina ML, Liu W, Wang EW, et al. NKCC1 up-regulation contributes to early post-traumatic seizures and increased post-traumatic seizure susceptibility. Brain Struct Funct. (2017) 222:1543–56. 10.1007/s00429-016-1292-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu KT, Cheng NC, Wu CY, Yang YL. NKCC1-mediated traumatic brain injury-induced brain edema and neuron death via raf/mek/mapk cascade. Crit Care Med. (2008) 36:917–22. 10.1097/CCM.0B013E31816590C4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bonislawski DP, Schwarzbach EP, Cohen AS. Brain injury impairs dentate gyrus inhibitory efficacy. Neurobiol Dis. (2007) 25:163–9. 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pol van den AN, Obrietan K, Chen G. Excitatory actions of GABA after neuronal trauma. J Neurosci. (1996) 16:4283–92. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04283.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lu KT, Wu CY, Cheng NC, Wo YYP, Yang JT, Yen HH, et al. Inhibition of the Na+-K+-2Cl–cotransporter in choroid plexus attenuates traumatic brain injury-induced brain edema and neuronal damage. Eur J Pharmacol. (2006) 548:99–105. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.07.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ben-Ari Y. NKCC1 chloride importer antagonists attenuate many neurological and psychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci. (2017) 40:536–54. 10.1016/j.tins.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lu K-T, Wu C-Y, Yen H-H, Peng J-HF, Wang C-L, Yang Y-L. Bumetanide administration attenuated traumatic brain injury through IL-1 overexpression. Neurol Res. (2007) 29:404–9. 10.1179/016164107X204738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kahle KT, Gerzanich V, Simard MJ. Molecular mechanisms of microvascular failure in CNS injury - synergistic roles of NKCC1 and SUR1/TRPM4. J Neurosurg. (2010) 113:611–29. 10.3171/2009.11.JNS081052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sudhakar SK, Choi TJ, Ahmed OJ. Biophysical modeling suggests optimal drug combinations for improving the efficacy of GABA agonists after traumatic brain injuries. J Neurotrauma. (2019) 36:1–14. 10.1089/neu.2018.6065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sudhakar SK, Choi TJ, Hetrick V, Ahmed OJ. Biophysical modeling reveals efficacious drug combinations for improved neuroprotection immediately after traumatic brain injury. Soc Neurosci Abstracts. (2018). Available online at: https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/4649/presentation/29308

- 91.Huberfeld G, Wittner L, Clemenceau S, Baulac M, Kaila K, Miles R, et al. Perturbed chloride homeostasis and GABAergic signaling in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. (2007) 27:9866–73. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2761-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dargaei Z, Bang JY, Mahadevan V, Khademullah CS, Bedard S, Parfitt GM, et al. Restoring GABAergic inhibition rescues memory deficits in a Huntington's disease mouse model. Proc Nat Acad Sci. (2018) 115:E1618–26. 10.1073/pnas.1716871115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Palma E, Amici M, Sobrero F, Spinelli G, Di Angelantonio S, Ragozzino D, et al. Anomalous levels of Cl- transporters in the hippocampal subiculum from temporal lobe epilepsy patients make GABA excitatory. Proc Nat Acad Sci. (2006) 103:8465–8. 10.1073/pnas.0602979103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Staley KJ, Soldo BL, Proctor WR. Ionic mechanisms of neuronal excitation by inhibitory GABA(A) receptors. Science. (1995) 269:977–81. 10.1126/science.7638623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim DY, Fenoglio KA, Kerrigan JF, Rho JM. Bicarbonate contributes to GABAA receptor-mediated neuronal excitation in surgically resected human hypothalamic hamartomas. Epilepsy Res. (2009) 83:89–93. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kaila K, Voipio J, Paalasmaa P, Pasternack M, Deisz RA. The role of bicarbonate in GABAA receptor-mediated IPSPs of rat neocortical neurones. J Physiol. (1993) 464:273–89. 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Staley KJ, Proctor WR. Modulation of mammalian dendritic GABA(A) receptor function by the kinetics of Cl-and HCO3-transport. J Physiol. (1999) 519:693–712. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0693n.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gibson CJ, Meyer RC, Hamm RJ. Traumatic brain injury and the effects of diazepam, diltiazem, and MK-801 on GABA-A receptor subunit expression in rat hippocampus. J Biomed Sci. (2010) 17:38 10.1186/1423-0127-17-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Raible DJ, Frey LC, Cruz Del Angel Y, Russek SJ, Brooks-Kayal AR. GABAA receptor regulation after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. (2012) 29:2548–54. 10.1089/neu.2012.2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kao C-Q, Goforth PB, Ellis EF, Satin LS. Potentiation of GABA(A) currents after mechanical injury of cortical neurons. J Neurotrauma. (2004) 21:259–70. 10.1089/089771504322972059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sihver S, Marklund N, Hillered L, Långström B, Watanabe Y, Bergström M. Changes in mACh, NMDA and GABAA receptor binding after lateral fluid-percussion injury: In vitro autoradiography of rat brain frozen sections. J Neurochem. (2001) 78:417–23. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Remodeling dendritic spines for treatment of traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen Res. (2019) 14:1477–80. 10.4103/1673-5374.255957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gertler R, Brown HC, Mitchell DH, Silvius EN. Dexmedetomidine: a novel sedative-analgesic agent. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). (2001) 14:13–21. 10.1080/08998280.2001.11927725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhao Z, Ren Y, Jiang H, Huang Y. Dexmedetomidine inhibits the PSD95-NMDA receptor interaction to promote functional recovery following traumatic brain injury. Exp Ther Med. (2020) 20:1–1. 10.3892/etm.2020.9436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shen M, Wang S, Wen X, Han XR, Wang YJ, Zhou XM, et al. Dexmedetomidine exerts neuroprotective effect via the activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in rats with traumatic brain injury. Biomed Pharmacother. (2017) 95:885–93. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang D, Xu X, Wu YG Lyu L, Zhou ZW, Zhang JN. Dexmedetomidine attenuates traumatic brain injury: action pathway and mechanisms. Neural Regen Res. (2018) 13:819–26. 10.4103/1673-5374.232529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wu J, Vogel T, Gao X, Lin B, Kulwin C, Chen J. Neuroprotective effect of dexmedetomidine in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:4935. 10.1038/s41598-018-23003-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sun D, Wang J, Liu X, Fan Y, Yang M, Zhang J. Dexmedetomidine attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and improves neuronal function after traumatic brain injury in mice. Brain Res. (2020) 1732:46682. 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.146682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Feng X, Ma W, Zhu J, Jiao W, Wang Y. Dexmedetomidine alleviates early brain injury following traumatic brain injury by inhibiting autophagy and neuroinflammation through the ROS/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. (2021) 24:661. 10.3892/mmr.2021.12300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bullock MR, Lyeth BG, Muizelaar JP. Current status of neuroprotection trials for traumatic brain injury: lessons from animal models and clinical studies. Neurosurgery. (1999) 45:207–17. 10.1097/00006123-199908000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sayeed I, Stein DG. Progesterone as a neuroprotective factor in traumatic and ischemic brain injury. Prog Brain Res. (2009) 175:219–37. 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17515-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stein DG. Embracing failure: What the phase III progesterone studies can teach about TBI clinical trials. Brain Inj. (2015) 29:1259–72. 10.3109/02699052.2015.1065344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]