Abstract

Introduction

This exploratory analysis of FINCH 1 (NCT02889796) examined filgotinib (FIL) efficacy and safety in a subgroup of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inadequate response to methotrexate (MTX; MTX-IR) who had four poor prognostic factors (PPFs).

Methods

Patients with MTX-IR received placebo up to week (W)24 or FIL200 mg, FIL100 mg, or adalimumab up to W52; all received MTX. Efficacy and safety data were stratified by four PPFs versus fewer than four PPFs: seropositivity, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 6 mg/L, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints with CRP > 5.1, and erosions on X-rays.

Results

At baseline, 687/1755 patients had four PPFs. At W12, whether with four PPFs or fewer than four PPFs, response rates on all American College of Rheumatology (ACR) measures were significantly greater with FIL200 and FIL100 versus placebo. At W52, FIL200 ACR20/50/70 response rates remained at least numerically higher versus adalimumab in both subgroups. At W52, FIL200 reduced modified total Sharp score (mTSS) change versus adalimumab in patients with four or fewer than four PPFs.

Conclusions

In high-risk (four PPFs) patients with MTX-IR RA, FIL200 and FIL100 showed similar reductions in disease activity versus placebo at W12 as in patients with fewer than four PPFs. mTSS in patients receiving FIL200 changed little from W24 to W52, while that in patients receiving FIL100 progressed comparably to patients who received adalimumab. Tolerability was comparable across treatment arms and subgroups.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-022-00498-x.

Keywords: Filgotinib, Poor prognostic factors, Adalimumab, Methotrexate

Key Summary Points

| What is already known about this subject? |

| The 2019 EULAR management guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) recommend early treatment escalation for patients with predefined poor prognostic factors (PPFs). |

| Filgotinib 200 mg plus background methotrexate (MTX) provided rapid and clinically meaningful improvement in RA symptoms and physical function along with significant suppression of radiographic progression compared with MTX in patients who had inadequate response (IR) to MTX. |

| A post hoc analysis of MTX-naïve patients showed that the presence of four PPFs did not impair the efficacy of filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX. |

| What does this study add? |

| In patients with MTX-IR with four or fewer than four PPFs, filgotinib plus MTX provided benefits at week 12 in disease activity and functional measures and, at week 24, in radiographic progression versus MTX alone. |

| At week 52, filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX sustained the inhibition of modified total Sharp score (mTSS) change observed at week 24 even in patients with four PPFs; filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX progressed more; however, it was still comparable to adalimumab. |

| How might this impact clinical practice or future developments? |

| Patients with established MTX-IR RA and all four PPFs have a higher risk of joint destruction progression than those with fewer than four PPFs if not treated adequately. |

| Filgotinib 200 mg can be efficaciously added on to MTX monotherapy regardless of PPF status. |

Introduction

Despite the widespread availability of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), many patients are not able to achieve and sustain remission of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [1, 2]. Failed or inadequate response (IR) to DMARDs is associated with poor prognosis; additionally, several disease characteristics have been identified as poor prognostic factors (PPFs) in early RA, including seropositivity defined by rheumatoid factor (RF) or cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) positive, high baseline high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), high baseline disease activity, and extant bone erosion at disease onset [3–5].

The 2019 EULAR guidelines for management of RA recommend early treatment escalation for patients who do not achieve 50% improvement within 3 months [3]. On the basis of the presence of any of these four PPFs, addition of a biologic DMARD (bDMARD) or a targeted synthetic DMARD is recommended.

As reviewed by Tanaka et al. [6], the efficacy of filgotinib in combination with conventional synthetic DMARDs has been demonstrated in patients with moderately to severely active RA with IRs to methotrexate (MTX) or prior bDMARD treatments and in patients who were MTX naïve. Filgotinib has consistently shown acceptable safety and tolerability profiles, including those concerning known adverse events associated with Janus kinase inhibitors, such as opportunistic infections, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), venous thromboembolism (VTE), and hematologic changes [6, 7].

Aletaha et al. [8] showed that efficacy of filgotinib 200 mg (FIL200) plus MTX was not compromised in an MTX-naïve population despite the presence of four PPFs by comparing the subgroup of patients with four PPFs with the overall study population. The impact of the multiple PPFs, and of the greater number of PPFs, on treatment with filgotinib in an MTX-IR population has not been evaluated. As inadequate response to DMARD therapy is itself predictive of poor response, it is of value to assess the efficacy of filgotinib treatment in patients with MTX-IR who have four PPFs.

The population of the FINCH 1 (NCT02889796) [7] trial of filgotinib included patients who had MTX-IR and at least one of these four PPFs. In the trial, FIL200 plus MTX was shown to have superior clinical efficacy and a comparable safety profile versus MTX alone and showed comparable efficacy and safety to the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (ADA) plus MTX. This post hoc analysis was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of FIL200 and FIL100 compared with placebo and ADA, all with background MTX, in patients with MTX-IR RA in subgroups of those with all four PPFs versus those with fewer than four PPFs.

Methods

The global, phase 3, double-blind, active-controlled FINCH 1 study, performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Advarra Central Institutional Review Board, has been described in detail [9]. Patients with MTX-IR who have moderately to severely active RA were randomized 3:3:2:3 to FIL200 or FIL100, subcutaneous ADA 40 mg biweekly, or placebo, all with stable weekly background MTX. All patients were required to have one of the following: one or more documented joint erosion on radiographs of the hands, wrists, or feet by central reading and positive result for anti-CCP antibodies or RF (based on central laboratory); three or more documented erosions on radiographs of the hands, wrists, or feet by central reading if both antibodies were negative (based on central laboratory) or serum hsCRP ≥ 6 mg/L (based on central laboratory). The study design is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. At week (W)24, patients in the placebo group were re-randomized to FIL200 or FIL100 while continuing background MTX. Per protocol, patients without adequate treatment response (< 20% improvement from baseline in either swollen joint count 66 or tender joint count 68) at W14 or two consecutive visits after W30 were switched to standard of care but continued study visits. All patients provided written informed consent.

We conducted a post hoc analysis of FINCH 1 with focus on the clinical benefit of filgotinib among the subgroup of patients who met all four PPFs at baseline—seropositivity for RF or anti-CCP, hsCRP ≥ 6 mg/L, Disease Activity Score for rheumatoid arthritis in 28 joints with C-reactive protein (DAS28[CRP]) > 5.1, and erosions—as well as in the subgroup of all other patients, i.e., those who had fewer than all four of these PPFs. The PPFs correspond to the criteria used in our recent examination of filgotinib in MTX-naïve patients, except that the hsCRP criterion among MTX-naïve patients was ≥ 4 mg/L, in keeping with the entry criteria of that trial [8, 10]. The following efficacy outcomes were examined at W12 and W52: American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response rates (20/50/70); DAS28(CRP) < 2.6; remission (Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) ≤ 2.8, Simple Disease Activity Index (SDAI) ≤ 3.3, Boolean); low disease activity (LDA; DAS28(CRP) ≤ 3.2, CDAI ≤ 10, SDAI ≤ 11); and physical function (Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI)). Joint destruction [modified total Sharp score (mTSS)) was assessed at W24 and W52, corresponding to study imaging timepoints. Safety assessments included treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), TEAEs leading to study drug discontinuation, deaths, laboratory values, and TEAEs of interest: serious infections, opportunistic infections, active tuberculosis, herpes zoster, MACE, VTE, malignancy, and gastrointestinal perforation.

Efficacy analyses were based on the full analysis set, including patients who were randomized and received at least one dose of study drug. For binary endpoints, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for response rate and difference in response rates were based on normal approximation method with a continuity correction. The Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons between treatment groups; all P-values should be considered nominal. Patients with missing outcomes were set as nonresponders for binary response measurements. Binary endpoints were also presented using number needed to treat (NNT; the number of patients who would need to receive FIL200 or FIL100 for one additional patient to achieve the endpoint at W12). Changes from baseline in HAQ-DI and mTSS were based on the mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM), including treatment, visit (as categorical), treatment by visit, and baseline value as fixed effects and patients being the random effect. Least-squares mean, 95% CI, and P-values were provided from MMRM; all P-values should be considered nominal. Missing change scores were not imputed using the MMRM approach, assuming an unstructured variance–covariance matrix for the repeated measures.

Results

At baseline, 687/1755 patients (39%) had all four PPFs, while 582 (33%), 404 (23%), 75 (4%), and 7 (< 1%) had three, two, one, and zero PPFs, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the number of patients with each combination of PPFs. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics among patients with four PPFs and fewer than four PPFs, including age and gender, were similar across subgroups; RA duration was 8.3 years versus 7.4 years in patients with four versus fewer than four PPFs (Table 1). In addition to the higher hsCRP and DAS28(CRP) values implicit in the PPF criteria, patients with four PPFs had higher CDAI, SDAI, and HAQ-DI scores than did those with fewer than four PPFs. Though the proportion of seropositive patients was higher in the four-PPF subgroup, even the fewer-than-four-PPF subgroup included 642/1068 (60.1%) patients who were seropositive for both RF and anti-CCP. mTSS was higher in patients with four PPFs, although the difference was small in patients treated with placebo. Details of baseline DAS28(CRP), SDAI, and CDAI by number of PPFs present (0–4) are presented in Supplementary Table 2, and corresponding baseline mTSS and disease duration are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Each of these parameters indicated greater disease activity at baseline as the number of PPFs present increased.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Patients with 4 PPFs | Patients with < 4 PPFs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIL200 (n = 191) | FIL100 (n = 189) | ADA (n = 126) | PBO (n = 181) | Total (n = 687) | FIL200 (n = 284) | FIL100 (n = 291) | ADA (n = 199) | PBO (n = 294) | Total (n = 1068) | |

| Age, years | 53 (13.1) | 54 (11.9) | 53 (11.9) | 54 (13.0) | 53 (12.5) | 51 (12.5) | 52 (13.0) | 54 (13.5) | 53 (12.7) | 52 (12.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 155 (81.2) | 155 (82.0) | 99 (78.6) | 147 (81.2) | 556 (80.9) | 224 (78.9) | 244 (83.8) | 167 (83.9) | 244 (83.0) | 879 (82.3) |

| RA duration, years | 7.5 (7.31) | 9.5 (8.47) | 8.7 (7.76) | 7.5 (6.58) | 8.3 (7.59) | 7.1 (7.44) | 7.9 (8.00) | 7.5 (7.15) | 7.2 (7.62) | 7.4 (7.59) |

| Concurrent oral glucocorticoid use, n (%) | 94 (49.2) | 92 (48.7) | 63 (50.0) | 87 (48.1) | 336 (48.9) | 135 (47.5) | 137 (47.1) | 77 (38.7) | 130 (44.2) | 479 (44.9) |

| Glucocorticoid dose, mg/day | 6.1 (2.38) | 6.7 (2.49) | 6.3 (2.30) | 6.2 (2.46) | 6.4 (2.42) | 6.2 (4.00) | 5.6 (2.41) | 5.6 (2.10) | 5.6 (2.53) | 5.8 (2.93) |

| Concurrent antimalarial use, n (%) | 25 (13.1) | 22 (11.6) | 15 (11.9) | 17 (9.4) | 79 (11.5) | 39 (13.7) | 37 (12.7) | 24 (12.1) | 46 (15.6) | 146 (13.7) |

| Seropositivity, n (%) | ||||||||||

| RF | 171 (89.5) | 170 (89.9) | 114 (90.5) | 170 (93.9) | 625 (91.0) | 181 (63.7) | 192 (66.0) | 127 (63.8) | 195 (66.3) | 695 (65.1) |

| Anti-CCP | 178 (93.2) | 171 (90.5) | 118 (93.7) | 168 (92.8) | 635 (92.4) | 202 (71.1) | 210 (72.2) | 135 (67.8) | 210 (71.4) | 757 (70.9) |

| RF and anti-CCP | 158 (82.7) | 152 (80.4) | 106 (84.1) | 157 (86.7) | 573 (83.4) | 173 (60.9) | 180 (61.9) | 113 (56.8) | 176 (59.9) | 642 (60.1) |

| hsCRP, mg/L | 25.7 (23.21) | 26.3 (26.89) | 25.0 (21.98) | 29.0 (31.21) | 26.6 (26.33) | 9.7 (16.52) | 10.5 (17.47) | 8.0 (10.60) | 8.4 (13.28) | 9.2 (15.02) |

| hsCRP ≥ 6 mg/L, n (%) | 191 (100) | 189 (100) | 126 (100) | 181 (100) | 687 (100) | 107 (37.7) | 106 (36.4) | 71 (35.7) | 93 (31.6) | 377 (35.3) |

| mTSS | 37.8 (49.07) | 49.8 (63.02) | 46.5 (60.45) | 33.6 (50.65) | 41.6 (56.02) | 28.8 (46.88) | 27.9 (43.13) | 27.2 (49.85) | 30.3 (54.84) | 28.7 (48.75) |

| mTSS, median | 19.50 | 21.00 | 23.50 | 12.00 | 17.00 | 10.00 | 8.75 | 8.00 | 11.00 | 9.50 |

| mTSS erosion score | 15.8 (23.98) | 23.8 (33.16) | 21.3 (32.10) | 14.2 (24.12) | 18.6 (28.58) | 12.6 (24.26) | 12.1 (21.39) | 11.2 (25.50) | 13.9 (30.38) | 12.6 (25.60) |

| Erosion score > 0, n (%) | 191 (100) | 189 (100) | 126 (100) | 181 (100) | 687 (100) | 208 (73.2) | 222 (76.3) | 151 (75.9) | 223 (75.9) | 804 (75.3) |

| SJC66 | 18 (9.3) | 17 (8.1) | 17 (8.7) | 18 (9.3) | 17 (8.9) | 14 (7.6) | 15 (8.7) | 15 (8.2) | 14 (7.4) | 14 (8.0) |

| TJC68 | 27 (13.4) | 27 (13.2) | 25 (13.3) | 28 (13.4) | 27 (13.3) | 23 (13.3) | 23 (13.4) | 23 (13.1) | 23 (13.3) | 23 (13.3) |

| HAQ-DI | 1.7 (0.58) | 1.7 (0.54) | 1.7 (0.50) | 1.8 (0.55) | 1.7 (0.55) | 1.5 (0.62) | 1.4 (0.66) | 1.5 (0.64) | 1.5 (0.63) | 1.5 (0.64) |

| DAS28(CRP) | 6.2 (0.70) | 6.2 (0.69) | 6.2 (0.64) | 6.3 (0.69) | 6.3 (0.68) | 5.4 (0.84) | 5.3 (0.92) | 5.4 (0.88) | 5.4 (0.84) | 5.4 (0.87) |

| CDAI | 42.9 (11.77) | 42.6 (10.70) | 41.9 (9.52) | 44.3 (10.42) | 43.0 (10.74) | 37.3 (11.39) | 36.0 (12.47) | 37.4 (12.32) | 36.7 (11.45) | 36.8 (11.88) |

| SDAI | 45.4 (12.05) | 45.2 (11.49) | 44.4 (9.97) | 47.2 (11.28) | 45.6 (11.35) | 38.3 (11.55) | 37.0 (12.59) | 38.2 (12.38) | 37.5 (11.56) | 37.7 (12.00) |

Numbers indicate mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. All treatment groups also received methotrexate

ADA adalimumab, CCP cyclic citrullinated peptide, CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, DAS28(CRP) Disease Activity Score for rheumatoid arthritis in 28 joints with C-reactive protein, FIL100 filgotinib 100 mg, FIL200 filgotinib 200 mg, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, hsCRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, mTSS modified total Sharp/van der Heijde score, PBO placebo, PPF poor prognostic factor, RA rheumatoid arthritis, RF rheumatoid factor, SD standard deviation, SDAI Simple Disease Activity Index, SJC66 swollen joint count in 66 joints, TJC68 tender joint count in 68 joints

ACR response rates (20/50/70) over time are shown in Fig. 1. In the placebo (+ MTX) arm, the ACR20 response rate was numerically greater among patients with four PPFs than among those with fewer than four PPFs. Among patients with four PPFs, FIL200 and FIL100 showed greater response rates than placebo for ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 (P < 0.05 for all), which was consistent with findings for the study’s overall population [7]; proportions achieving ACR20 were 77.5%, 75.7%, 70.6%, and 55.2% at W12 in the FIL200, FIL100, ADA, and placebo groups, respectively. At W52, the only significant difference in ACR response between either filgotinib dosage and ADA was for ACR20 among patients with four PPFs treated with FIL200. Compared with those with four PPFs, patients with fewer than four PPFs had similar ACR response rates across treatment arms, although no formal analysis was performed between the four-PPF and fewer-than-four-PPF groups. FIL200 and FIL100 also were associated with increased rates of ACR improvement versus placebo at W12 among patients with fewer than four PPFs (P < 0.05); proportions of FIL200, FIL100, ADA, and placebo groups who reached ACR20 at W12 were 76.1% (95% CI 70.9–81.2%), 66.0% (95% CI 60.4–71.6%), 70.4% (95% CI 63.8–76.9%), and 46.6% (95% CI 40.7–52.5%).

Fig. 1.

Proportions (%) of patients with four and fewer than four PPFs achieving ACR20/50/70 response over time for A ACR20 B ACR50 C ACR70. All treatment groups also received methotrexate. For ACR20, response rates with FIL200 and FIL100 were significantly different (P < 0.05) versus PBO at weeks 2–24, except for FIL100 at week 14, in the four-PPF subgroup and at every timepoint in the fewer-than-four-PPF subgroup. Response rates with FIL200 were significantly different (P < 0.05) versus ADA at weeks 30, 44, and 52 among patients with four PPFs, while FIL100 was not significantly different from ADA at any timepoint. Among patients with fewer than four PPFs, response rates among both filgotinib groups were similar to those of ADA. For ACR50, response rates with FIL200 and FIL100 were significantly different (P < 0.05) versus PBO at every timepoint in the four-PPF subgroup and in the fewer-than-four-PPF subgroup. For ACR70, response rates with FIL200 were significantly different (P < 0.05) versus PBO at every timepoint in both subgroups except at week 2 among patients with four PPFs. FIL100 was significantly different from PBO at every timepoint except weeks 2 and 4 in both subgroups. Response rates with FIL were not significantly different versus ADA at weeks 26–52 in either subgroup. ACR20/50/70 American College of Rheumatology 20%, 50%, and 70% improvement; ADA adalimumab; BL baseline; FIL100 filgotinib 100 mg; FIL200 filgotinib 200 mg; PBO placebo; PPF poor prognostic factor

Proportions achieving DAS28(CRP) < 2.6, CDAI ≤ 2.8, SDAI ≤ 3.3, and Boolean remission at W12 and W52 are presented in Table 2. At W12, the proportion of patients achieving each endpoint was significantly greater in both filgotinib groups versus placebo, except for Boolean remission in patients with four PPFs receiving FIL100. Proportions of filgotinib-treated patients achieving DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 or clinical remission were lower among patients with four PPFs versus patients with fewer than four PPFs at W12. At W52, FIL200 showed greater improvement compared with the ADA-treated group for DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 and Boolean remission among patients with four PPFs. At W52, similar proportions of patients who were treated with FIL200 achieved DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 among those with four PPFs or with fewer than four PPFs (53.4% and 54.2% respectively); likewise, proportions achieving Boolean remission were 23.6% with four PPFs and 21.8% with fewer than four PPFs.

Table 2.

Proportions of patients achieving efficacy endpoints

| FIL200 | FIL100 | ADA | PBO | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 PPFs (n = 191) |

< 4 PPFs (n = 284) | 4 PPFs (n = 189) | < 4 PPFs (n = 291) | 4 PPFs (n = 126) |

< 4 PPFs (n = 199) | 4 PPFs (n = 181) |

< 4 PPFs (n = 294) | |||

| DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 at W12 | 59 (30.9) | 103 (36.3) | 37 (19.6) | 77 (26.5) | 20 (15.9) | 57 (28.6) | 11 (6.1) | 33 (11.2) | ||

| 95% CI, % | 24.1, 37.7 | 30.5, 42.0 | 13.7, 25.5 | 21.2, 31.7 | 9.1, 22.7 | 22.1, 35.2 | 2.3, 9.8 | 7.4, 15.0 | ||

| P-value versus PBO | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| P-value versus ADA | 0.002 | 0.095 | 0.46 | 0.61 | ||||||

| DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 at W52 | 102 (53.4) | 154 (54.2) | 71 (37.6) | 135 (46.4) | 50 (39.7) | 100 (50.3) | ||||

| 95% CI, % | 46.1, 60.7 | 48.3, 60.2 | 30.4, 44.7 | 40.5, 52.3 | 30.7, 48.6 | 43.1, 57.4 | ||||

| P-value versus ADA | 0.021 | 0.41 | 0.72 | 0.41 | ||||||

| CDAI ≤ 2.8 at W12 | 18 (9.4) | 41 (14.4) | 18 (9.5) | 35 (12.0) | 6 (4.8) | 13 (6.5) | 4 (2.2) | 9 (3.1) | ||

| 95% CI, % | 5.0, 13.8 | 10.2, 18.7 | 5.1, 14.0 | 8.1, 15.9 | 0.6, 8.9 | 2.8, 10.2 | 0.0, 4.6 | 0.9, 5.2 | ||

| P-value versus PBO | 0.004 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| P-value versus ADA | 0.14 | 0.008 | 0.13 | 0.046 | ||||||

| CDAI ≤ 2.8 at W52 | 58 (30.4) | 82 (28.9) | 42 (22.2) | 74 (25.4) | 27 (21.4) | 47 (23.6) | ||||

| 95% CI, % | 23.6, 37.1 | 23.4, 34.3 | 16.0, 28.4 | 20.3, 30.6 | 13.9, 29.0 | 17.5, 29.8 | ||||

| P-value versus ADA | 0.092 | 0.21 | 0.89 | 0.67 | ||||||

| SDAI ≤ 3.3 at W12 | 19 (9.9) | 42 (14.8) | 14 (7.4) | 31 (10.7) | 6 (4.8) | 16 (8.0) | 4 (2.2) | 10 (3.4) | ||

| 95% CI, % | 5.4, 14.5 | 10.5, 19.1 | 3.4, 11.4 | 6.9, 14.4 | 0.6, 8.9 | 4.0, 12.1 | 0.0, 4.6 | 1.2, 5.6 | ||

| P-value versus PBO | 0.002 | < 0.001 | 0.028 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| P-value versus ADA | 0.13 | 0.032 | 0.48 | 0.35 | ||||||

| SDAI ≤ 3.3 at W52 | 55 (28.8) | 86 (30.3) | 43 (22.8) | 75 (25.8) | 28 (22.2) | 50 (25.1) | ||||

| 95% CI, % | 22.1, 35.5 | 24.8, 35.8 | 16.5, 29.0 | 20.6, 31.0 | 14.6, 29.9 | 18.8, 31.4 | ||||

| P-value versus ADA | 0.24 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 0.92 | ||||||

| Boolean remission at W12 | 13 (6.8) | 32 (11.3) | 10 (5.3) | 21 (7.2) | 4 (3.2) | 13 (6.5) | 3 (1.7) | 6 (2.0) | ||

| 95% CI, % | 3.0, 10.6 | 7.4, 15.1 | 1.8, 8.7 | 4.1, 10.4 | 0.0, 6.6 | 2.8, 10.2 | 0.0, 3.8 | 0.3, 3.8 | ||

| P-value versus PBO | 0.019 | < 0.001 | 0.088 | 0.003 | ||||||

| P-value versus ADA | 0.21 | 0.082 | 0.42 | 0.86 | ||||||

| Boolean remission at W52 | 45 (23.6) | 62 (21.8) | 34 (18.0) | 58 (19.9) | 18 (14.3) | 37 (18.6) | ||||

| 95% CI, % | 17.3, 29.8 | 16.9, 26.8 | 12.2, 23.7 | 15.2, 24.7 | 7.8, 20.8 | 12.9, 24.2 | ||||

| P-value versus ADA | 0.045 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.73 | ||||||

Proportions are reported as n (%). All treatment groups also received methotrexate

ADA adalimumab, CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, CI confidence interval, DAS28(CRP) Disease Activity Score for rheumatoid arthritis in 28 joints with C-reactive protein, FIL100 filgotinib 100 mg, FIL200 filgotinib 200 mg, PBO placebo, PPF poor prognostic factor, SDAI Simple Disease Activity Index, W week

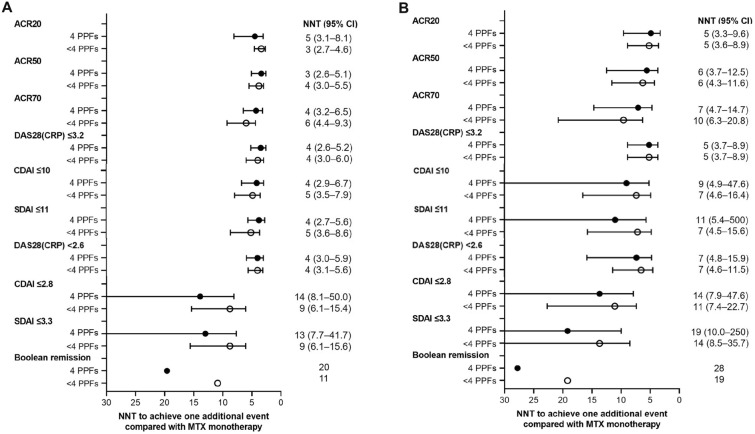

To further describe the clinical benefit of filgotinib in patients with four PPFs, the NNT for FIL200 and FIL100 versus placebo was calculated for ACR response rates, DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 and ≤ 3.2, CDAI ≤ 2.8 and ≤ 10, SDAI ≤ 3.3 and ≤ 11, and Boolean remission (Fig. 2). For ACR response rates, DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 and ≤ 3.2, and LDA by CDAI and SDAI, NNTs among patients with four PPFs were comparable to those among patients with fewer than four PPFs for both FIL200 and FIL100. Regarding remission criteria, NNTs for patients with four PPFs were numerically greater than for those with fewer than four PPFs; NNTs for FIL200 for CDAI ≤ 2.8, SDAI ≤ 3.3, and Boolean remission were 14, 13, and 20 among patients with four PPFs versus 9, 9, and 11 for those with fewer than four PPFs, respectively. NNTs for FIL100 were consistently larger than NNTs for FIL200.

Fig. 2.

Number needed to treat for one additional patient to achieve each efficacy endpoint A FIL200 B FIL100. All treatment groups also received methotrexate. Error bars are not shown when the values span zero. ACR20/50/70 American College of Rheumatology 20%, 50%, and 70% improvement, CDAI Clinical Disease Activity Index, CI confidence interval, DAS28(CRP) Disease Activity Score for rheumatoid arthritis in 28 joints with C-reactive protein, FIL100 filgotinib 100 mg, FIL200 filgotinib 200 mg, MTX methotrexate, PPF poor prognostic factor, NNT number needed to treat, SDAI Simple Disease Activity Index

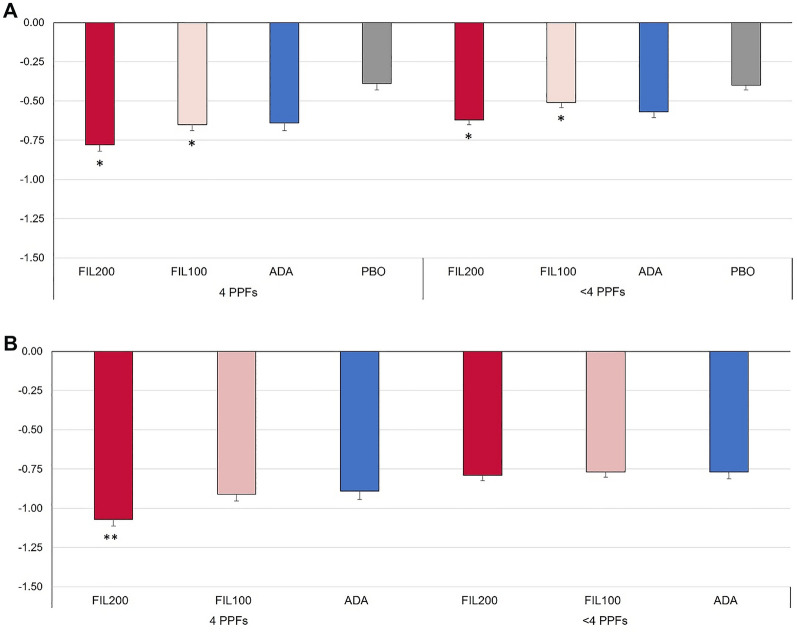

Filgotinib treatment was associated with benefits in physical function versus placebo at W12: Both filgotinib dose groups showed greater change from baseline (CFB) in HAQ-DI score versus placebo at W12 among patients with or without four PPFs, as shown in Fig. 3. Among patients with four PPFs, FIL200 showed significant improvement compared with ADA at W52, and reductions from baseline in HAQ-DI with FIL200 were numerically larger among patients with four PPFs versus those with fewer than four PPFs (−1.07 versus −0.79).

Fig. 3.

CFB in HAQ-DI among patients with four PPFs or others at A W12 and B W52. *P < 0 .05 versus PBO at W12; **P < 0.05 versus ADA at W52. Comparison to ADA at W12 is out of scope for statistical calculation. All treatment groups also received methotrexate. ADA adalimumab, CFB change from baseline, FIL100 filgotinib 100 mg, FIL200 filgotinib 200 mg, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, PBO placebo, PPF poor prognostic factor, W week

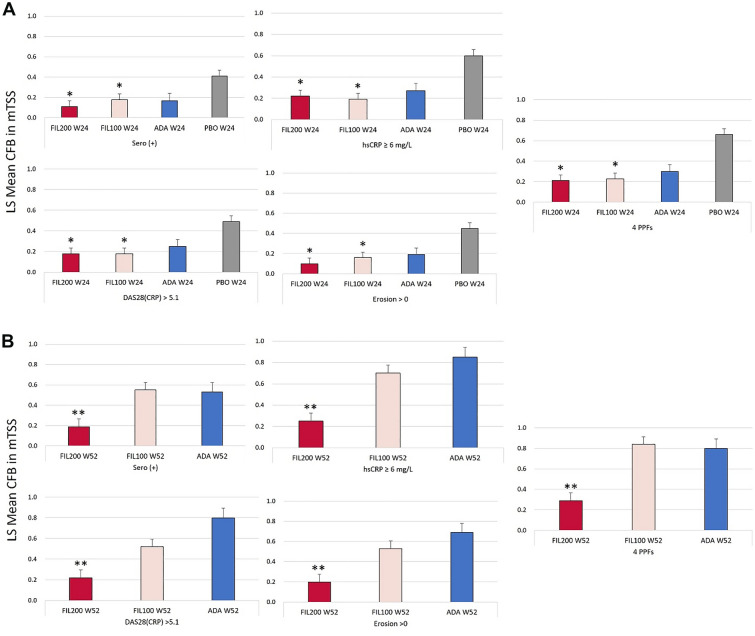

Figure 4 displays CFB in mTSS among patients with four PPFs and fewer than four PPFs at W24 and W52. At W24, FIL200 and FIL100 showed significantly reduced CFB versus placebo in patients with four PPFs and numerically smaller CFB versus placebo in patients with fewer than four PPFs. The change in mTSS at W24 was significantly higher for patients with four PPFs than for those with fewer than four PPFs in the placebo group (P = 0.007) and numerically higher among other treatment groups (Supplementary Table 4); proportions of patients with no radiographic progression were numerically lower in the four-PPF subgroup than in the fewer-than-four-PPF subgroup across treatment arms (Supplementary Fig. 3). FIL200 was associated with consistently higher proportions of patients with no radiographic progression than was placebo. At W52, only FIL200 reduced CFB versus ADA in patients with four PPFs (0.29 versus 0.80), while both FIL200 and FIL100 reduced CFB versus ADA in patients with fewer than four PPFs (0.14 and 0.25 versus 0.53). Supplementary Fig. 3 shows proportions without radiographic progression at W24 (based on ≤ 0.5-point change). FIL200 was associated with higher proportions free from progression in patients with four PPFs and those with fewer than four PPFs. Supplementary Fig. 4 shows CFB in mTSS score by treatment and number of PPFs, and Supplementary Fig. 5 shows cumulative percentile of mTSS CFB at W24 and W52.

Fig. 4.

CFB in mTSS among patients with four PPFs or fewer than four PPFs. *P < 0.05 versus PBO at W24 or versus ADA at W52. **P < 0.01 versus PBO at W24 or versus ADA at W52. All treatment groups also received methotrexate. ADA adalimumab, CFB change from baseline, FIL100 filgotinib 100 mg, FIL200 filgotinib 200 mg, mTSS modified total Sharp score, PBO placebo, PPF poor prognostic factor, W week

Illustrating the effects of any of the four PPFs on joint destruction, Fig. 5 shows that both FIL200 and FIL100 reduced CFB in mTSS at W24 compared with placebo in patients with any of the four PPFs as well as in patients with all four PPFs. At W24, the lowest CFB seen in the FIL200 treatment group was 0.1 in patients with erosions > 0, with the highest (0.22) being in patients with hsCRP ≥ 6 mg/L. At W52, FIL200 showed reduced CFB in mTSS versus ADA in patients with any of the four PPFs or all four PPFs, while reduction of CFB in mTSS with FIL100 was comparable to that with ADA.

Fig. 5.

LS mean CFB in mTSS among patients with any of the PPFs or four PPFs at A W24 or B W52. Each of the PPF subgroups [sero (+), hsCRP ≥ 6, DAS28(CRP) > 5.1, and erosion > 0] could include patients who also had other PPFs. *P < 0.05 versus PBO at W24; **P < 0.05 versus ADA at W52. Comparison to ADA at W24 is out of scope for statistical calculation. All treatment groups also received methotrexate. ADA adalimumab, CFB change from baseline, DAS28(CRP) disease activity score for rheumatoid arthritis in 28 joints with C-reactive protein, FIL100 filgotinib 100 mg, FIL200 filgotinib 200 mg, hsCRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, LS least squares, mTSS modified total Sharp score, PBO placebo, PPF poor prognostic factor, Sero (+) seropositivity for rheumatoid factor or anti-yclic citrullinated peptide, W week

Safety data (Table 3) showed no sign that having four PPFs was associated with any particular TEAE. Overall, approximately 70% of patients with four PPFs or with fewer than four PPFs in FIL200, FIL100, and ADA groups had TEAEs. Incidences of laboratory abnormalities, serious infections, herpes zoster, MACE, VTE, malignancy, and gastrointestinal perforation were low in patients with four PPFs or with fewer than four PPFs. Among patients with four PPFs originally randomized to placebo, serious TEAEs occurred in 7.2% during the 24-week placebo administration and in 3.6% and 4.5% of patients after switching to FIL200 and FIL100, respectively. Latent tuberculosis was found in one patient receiving FIL100 in the fewer-than-four-PPF subgroup.

Table 3.

Safety in patients with or four or fewer than four PPFs

| Patients with 4 PPFs | Patients with < 4 PPFs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIL200 (n = 191) | FIL100 (n = 189) | ADA (n = 126) | PBO after switch to FIL200 (n = 83) | PBO after switch to FIL100 (n = 66) | PBO before switch (n = 181) | FIL200 (n = 284) | FIL100 (n = 291) | ADA (n = 199) | PBO after switch to FIL200 (n = 107) | PBO after switch to FIL100 (n = 125) | PBO before switch (n = 294) | |

| All TEAEs | 146 (76.4) | 136 (72.0) | 85 (67.5) | 44 (53.0) | 35 (53.0) | 90 (49.7) | 206 (72.5) | 214 (73.5) | 154 (77.4) | 48 (44.9) | 62 (49.6) | 164 (55.8) |

| TEAE leading to premature discontinuation of study drug | 10 (5.2) | 7 (3.7) | 10 (7.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 7 (3.9) | 16 (5.6) | 8 (2.7) | 8 (4.0) | 5 (4.7) | 2 (1.6) | 8 (2.7) |

| Serious TEAE | 10 (5.2) | 12 (6.3) | 10 (7.9) | 3 (3.6) | 3 (4.5) | 13 (7.2) | 25 (8.8) | 28 (9.6) | 12 (6.0) | 4 (3.7) | 5 (4.0) | 8 (2.7) |

| Deaths | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 7 (2.5) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

| Lipids increased | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liver function test increased | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infections | ||||||||||||

| Serious infectious TEAE | 5 (2.6) | 4 (2.1) | 6 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.1) | 8 (2.8) | 9 (3.1) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (0.7) |

| Opportunistic infections | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Active tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Herpes zoster | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 5 (1.8) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 2 (0.7) |

| MACE | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| VTE | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| DVT | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| PE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignancy (non-NMSC) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.7) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GI perforation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

All treatment groups also received methotrexate. Malignancies included one incidence each of breast cancer stage I, malignant glioma, and prostate cancer in PBO before switch among the four-PPF group; one incidence each of intraductal proliferative breast lesion, metastases to liver, and pancreatic carcinoma in FIL200 in the fewer-than-four-PPF group; one incidence each of cervix carcinoma stage III and leiomyosarcoma metastatic in FIL100 in the fewer-than-four-PPF group; and one incidence each of breast cancer and lymphocyte morphology abnormal in ADA in the four-PPF group. One patient in the fewer-than-four-PPF subgroup who was treated with FIL100 had latent tuberculosis that was first identified at week 12

ADA adalimumab, DVT deep vein thrombosis, FIL100 filgotinib 100 mg, FIL200 filgotinib 200 mg, GI gastrointestinal, MACE major adverse cardiac event, NMSC nonmelanoma skin cancer, PBO placebo, PE pulmonary embolism, PPF poor prognostic factor, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event, VTE venous thromboembolism

Discussion

Previous post hoc analysis of the FINCH 3 trial found treatment with FIL200 (plus background MTX) to provide substantial benefits in disease control, including higher rates of remission, improved physical function, and reduced radiographic progression, compared with MTX alone in MTX-naïve patients with four PPFs [8]. The present analysis extends these findings to an MTX-IR population with notably longer duration of disease. Among this MTX-IR population, the subgroup with four PPFs was likely to be at higher risk of radiographic progression compared with those with fewer than four PPFs as observed in the placebo arm at W24, although several clinical responses were comparable between four-PPF and fewer-than-four-PPF subgroups. Results of this subgroup analysis showed that efficacy of FIL200 and FIL100 (with background MTX) in patients with four PPFs was comparable to the efficacy in the overall population of patients with MTX-IR shown in the primary report [9]. This analysis also showed that FIL200 had numerically greater efficacy in this population than did FIL100, regardless of the presence of four PPFs or fewer than four PPFs.

By W12, multiple endpoints showed advantages for filgotinib versus placebo in both subgroups of patients. Patients with four and fewer than four PPFs had higher rates of ACR20/50/70 response at W12 with FIL200 and FIL100 versus placebo. Patients in the FIL200 and FIL100 treatment groups had significantly higher proportions achieving DAS28(CRP) < 2.6, CDAI ≤ 2.8, and SDAI ≤ 3.3 among both four-PPF and fewer-than-four-PPF subgroups, and CFB in HAQ-DI was greater among both dose groups of filgotinib versus placebo. By W24, improvements in radiographic assessment could be seen with either filgotinib dose versus placebo. At W52, FIL200 showed benefits in DAS28(CRP) < 2.6, Boolean remission status, and change in HAQ-DI versus ADA while maintaining a comparable safety profile.

The introduction of bDMARDs helped address the unmet need to slow radiographic progression in patients who were MTX-IR [11]. Of note, FIL200 was associated with smaller CFB in mTSS versus ADA among patients with four PPFs and those with fewer than four PPFs. The sustained efficacy of FIL200 for reducing CFB mTSS among the four-PPF subgroup may be related to the lower mean baseline mTSS for FIL200 (37.8) compared with FIL100 (49.8) or ADA (46.5). Baseline mTSS could affect subsequent radiographic progression, as suggested by increased mTSS progression according to higher baseline mTSS associated with the number of PPFs present under treatment with placebo plus MTX (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, Supplementary Fig. 4D). Baseline mean and median mTSS among patients treated with FIL100 or ADA who had fewer than four PPFs were comparable with scores among patients treated with FIL200; nonetheless, patients treated with ADA progressed more compared with those receiving FIL200 or FIL100 at W52. The cause of the difference observed at W52 is not clear, but it is unlikely to be a mere product of potential outliers in the ADA arm.

As hsCRP ≥ 6 mg/L is among the four PPFs included in this analysis, with a notably higher baseline hsCRP level among patients in the four-PPF subgroup, it might be expected that rates of disease-activity measures that incorporate hsCRP, such as DAS28(CRP) < 2.6, CDAI ≤ 2.8, and Boolean remission, might be lower among patients with four PPFs. However, the treatment effects of filgotinib, as well as those of ADA and of MTX, in such patients did not appear to be substantially reduced compared with their effects in patients with fewer than four PPFs.

There was no sign of increased safety risk among patients with four PPFs, and despite greater efficacy associated with FIL200 compared with FIL100, there was no safety penalty. Serious infections occurred in 2.6% and 2.8% of patients taking FIL200 in the four-PPF and fewer-than-four-PPF subgroups, respectively, and herpes zoster respectively occurred in 0.5% and 1.8% of patients, a lower-than-expected incidence rate. Rates of serious TEAEs did not increase after patients originally randomized to placebo switched to filgotinib.

Attempts to refine models to predict RA clinical course are ongoing and may incorporate a wide variety of clinical variables [12–14]; these efforts are complicated by a lack of consensus on the ideal definition of clinical remission to use as the target of therapy. While the PPFs included in this analysis are recognized as useful in assessing patients’ risk of rapid progression [3, 15, 16], these factors may not be the most useful for predicting response in all patient populations [17], and evidence-based risk scoring may not perform satisfactorily when applied in clinical practice [18]. The present study shows, however, that presence of the four PPFs confers greater risk of radiographic progression under standard of care (MTX). Adding FIL200 resulted in consistent efficacy regardless of the presence of these four PPFs, and safety was acceptable.

As in MTX-naïve patients with PPFs, patients with MTX-IR who have these characteristics may benefit from additional therapy besides MTX monotherapy to achieve desired treatment responses. Furthermore, while there is still debate about whether the number of PPFs matters [19, 20], the present analysis, coupled with the previous analysis of filgotinib in an MTX-naïve population [6], suggests that greater numbers of PPFs may be associated with greater risk of radiographic progression. Combination of PPFs might be considered in the future, although the present study is limited in its ability to detect such combinations owing to its sample size.

Limitations of this analysis include its post hoc nature. Numbers of patients with and without four PPFs were unbalanced, and populations had additional, possibly relevant, baseline factors in addition to PPF status that may have contributed to their outcomes. Additional factors or combinations of factors likely exist that may have affected treatment outcomes but that were neither identified nor evaluated in this analysis.

Conclusions

FIL200 plus MTX treatment in patients with RA provided disease control observed by W12 across numerous disease assessments, including among patients with four PPFs, who may be considered at risk for severe progressive disease. Whether all four PPFs or fewer than four PPFs were present, FIL200 provided consistent symptom relief, physical function improvement, and suppression of radiographic progression, while the other treatment groups offered mixed results, with more robust effects among patients with fewer than four PPFs. Patients with four PPFs did not show higher safety risks with filgotinib treatment versus those with fewer than four PPFs. Filgotinib may thus represent a beneficial treatment option for patients with RA who have had inadequate response to MTX and have high risk of disease progression and poor prognosis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Foster City, CA. Funding for this analysis and for the Rapid Service Fee was provided by Eisai Co., Ltd., and Gilead Sciences K.K. The sponsors participated in the planning, execution, and interpretation of the research.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Rob Coover, MPH, and Gregory Bezkorovainy, MA, of AlphaScientia, LLC, San Francisco, CA and was funded by Eisai Co., Ltd., and Gilead Sciences K.K.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. We thank Ling Han of Gilead Sciences, Inc., for helpful suggestions on biostatistical analyses; and Chen Chi and her team at Gilead Sciences, Inc., for programming support of biostatistical analyses.

Author Contributions

B.G.C., Y.T., K.E., S.K., R.B.M.L., B.B., A.P., T.K.H., and D.A. were involved in the conception and design of the study/analyses. K.X. performed the data and statistical analyses. B.G.C., Y.T., M.H.B., P.N., G.R.B., A.J.K., K.E., S.K., R.B.M.L., and D.A. contributed to the interpretation of the data. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and provided final approval for publication.

Prior Presentation

This work was presented as a poster at the EULAR European Congress of Rheumatology 1–4 June 2022. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(suppl 1):632. POS0704.

Disclosures

Bernard G. Combe receives grant/research support from Pfizer and Roche-Chugai; and has received consulting and/or speaker fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Gilead-Galapagos, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche-Chugai. Yoshiya Tanaka has received speaking fees and/or honoraria from Gilead, AbbVie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Chugai, Amgen, YL Biologics, Eisai, Astellas, Bristol-Myers, and AstraZeneca; research grants from Asahi-Kasei, AbbVie, Chugai, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Eisai, Takeda, Daiichi-Sankyo, Kowa, and Boehringer-Ingelheim; and consultant fee from Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo, Taisho, Ayumi, Sanofi, GSK, and AbbVie. Maya H. Buch reports research support, consulting, speaker fees, or personal fees from AbbVie; Eli Lilly; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; Merck-Serono; Pfizer; Roche; Sanofi; and UCB. Peter Nash has received honoraria or consulting fees, grants, or research support, or been a member of a speakers’ bureau for AbbVie; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Celgene; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; Janssen; Eli Lilly; MSD; Novartis; Pfizer; Roche; Sanofi; and UCB. Gerd R. Burmester reports serving as a consultant and on a speakers’ bureau for AbbVie; Eli Lilly; Pfizer; and Gilead Sciences, Inc. Alan J. Kivitz is a shareholder of Amgen; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Pfizer; and Sanofi; served as a consultant for AbbVie; Boehringer Ingelheim; Flexion; Genzyme; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; Janssen; Novartis; Pfizer; Regeneron; Sanofi; Sun Pharmaceuticals; and SUN Pharma Advanced Research; is serving as a paid instructor for Celgene, Genzyme, Horizon, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi; and served on a speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Celgene, Flexion, Genzyme, Horizon, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi. Beatrix Bartok, Alena Pechonkina, and Katrina Xia are employees and shareholders of Gilead Sciences, Inc. Kahaku Emoto is a former employee of Gilead Sciences K.K. and shareholder of Gilead Sciences, Inc. Shungo Kano is an employee of Gilead Sciences K.K. and shareholder of Gilead Sciences, Inc. Thijs K. Hendrikx is an employee of Galapagos BV. Robert B. M. Landewé has received honoraria or consulting fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galapagos NV, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. Daniel Aletaha reports grants or research support from AbbVie, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, and Roche; serving as a consultant for Janssen; serving on a speaker’s bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme and UCB; and serving as a consultant and on a speaker’s bureau for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Medac, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, and Sanofi/Genzyme.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All participants provided written informed consent on enrollment. FINCH 1 was approved by the Advarra Central Institutional Review Board (reference # 00,000,971).

Data Availability

Anonymized individual patient data will be shared upon request for research purposes, dependent upon the nature of the request, the merit of the proposed research, the availability of the data, and its intended use. The full data sharing policy for Gilead Sciences, Inc., can be found at https://www.gilead.com/science-and-medicine/research/clinical-trials-transparency-and-data-sharing-policy.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: To correct the legend of the figure 5.

Change history

1/4/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s40744-022-00530-0

References

- 1.Sun X, Li R, Cai Y, Al-Herz A, Lahiri M, Choudhury MR, et al. Clinical remission of rheumatoid arthritis in a multicenter real-world study in Asia-Pacific region. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;15:100240. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray K, Turk M, Alammari Y, Young F, Gallagher P, Saber T, et al. Long-term remission and biologic persistence rates: 12-year real-world data. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02380-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolen JS, Landewe RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, Burmester GR, Dougados M, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):685–699. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird P, Nicholls D, Barrett R, de Jager J, Griffiths H, Roberts L, et al. Longitudinal study of clinical prognostic factors in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: the PREDICT study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20(4):460–468. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindqvist E, Eberhardt K, Bendtzen K, Heinegard D, Saxne T. Prognostic laboratory markers of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(2):196–201. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.019992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka Y, Kavanaugh A, Wicklund J, McInnes IB. Filgotinib, a novel JAK1-preferential inhibitor for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: an overview from clinical trials. Mod Rheumatol. 2022;32(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2021.1902617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winthrop KL, Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Kivitz A, Matzkies F, Genovese MC, et al. Integrated safety analysis of filgotinib in patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis receiving treatment over a median of 1.6 years. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(2):184–192. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aletaha D, Westhovens R, Gaujoux-Viala C, Adami G, Matsumoto A, Bird P, et al. Efficacy and safety of filgotinib in methotrexate-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis with poor prognostic factors: post hoc analysis of FINCH 3. RMD Open. 2021;7(2):e001621. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Combe B, Kivitz A, Tanaka Y, van der Heijde D, Simon JA, Baraf HSB, et al. Filgotinib versus placebo or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate: a phase III randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(7):848–858. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westhovens R, Rigby WFC, van der Heijde D, Ching DWT, Stohl W, Kay J, et al. Filgotinib in combination with methotrexate or as monotherapy versus methotrexate monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and limited or no prior exposure to methotrexate: the phase 3, randomised controlled FINCH 3 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Combe B, Lula S, Boone C, Durez P. Effects of biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs on the radiographic progression of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36(4):658–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins JE, Johansson FD, Gale S, Kim S, Shrestha S, Sontag D, et al. Predicting remission among patients with rheumatoid arthritis starting tocilizumab monotherapy: model derivation and remission score development. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(2):65–73. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalweit M, Walker UA, Finckh A, Muller R, Kalweit G, Scherer A, et al. Personalized prediction of disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis using an adaptive deep neural network. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0252289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma MHY, Defranoux N, Li W, Sasso EH, Ibrahim F, Scott DL, et al. A multi-biomarker disease activity score can predict sustained remission in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):158. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02240-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visser K, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Ronday HK, Seys PE, Kerstens PJ, et al. A matrix risk model for the prediction of rapid radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving different dynamic treatment strategies: post hoc analyses from the BeSt study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(7):1333–1337. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.121160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keystone EC, Ahmad HA, Yazici Y, Bergman MJ. Disease activity measures at baseline predict structural damage progression: data from the randomized, controlled AMPLE and AVERT trials. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59(8):2090–2098. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards CJ, Kiely P, Arthanari S, Kiri S, Mount J, Barry J, et al. Predicting disease progression and poor outcomes in patients with moderately active rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2019;3(1):rkz0002. doi: 10.1093/rap/rkz002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Cock D, Vanderschueren G, Meyfroidt S, Joly J, Van der Elst K, Westhovens R, et al. The performance of matrices in daily clinical practice to predict rapid radiologic progression in patients with early RA. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43(5):627–631. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landewe RB, Connell CA, Bradley JD, Wilkinson B, Gruben D, Strengholt S, et al. Is radiographic progression in modern rheumatoid arthritis trials still a robust outcome? Experience from tofacitinib clinical trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18(1):212. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-1106-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luurssen-Masurel N, Weel A, Koc GH, Hazes JMW, de Jong PHP. The number of risk factors for persistent disease determines the clinical course of early arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60(8):3617–3627. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized individual patient data will be shared upon request for research purposes, dependent upon the nature of the request, the merit of the proposed research, the availability of the data, and its intended use. The full data sharing policy for Gilead Sciences, Inc., can be found at https://www.gilead.com/science-and-medicine/research/clinical-trials-transparency-and-data-sharing-policy.