Abstract

The poor stability of Ru-based acidic oxygen evolution (OER) electrocatalysts has greatly hampered their application in polymer electrolyte membrane electrolyzers (PEMWEs). Traditional understanding of performance degradation centered on influence of bias fails in describing the stability trend, calling for deep dive into the essential origin of inactivation. Here we uncover the decisive role of reaction route (including catalytic mechanism and intermediates binding strength) on operational stability of Ru-based catalysts. Using MRuOx (M = Ce4+, Sn4+, Ru4+, Cr4+) solid solution as structure model, we find the reaction route, thereby stability, can be customized by controlling the Ru charge. The screened SnRuOx thus exhibits orders of magnitude lifespan extension. A scalable PEMWE single cell using SnRuOx anode conveys an ever-smallest degradation rate of 53 μV h−1 during a 1300 h operation at 1 A cm−2.

Subject terms: Electrocatalysis, Electrocatalysis

The poor stability of ruthenium-based catalysts has greatly hampered their application in polymer electrolyte membrane water electrolysis. Here, the authors uncover the decisive role of reaction route on catalytic performance, which enables the screening of efficient ruthenium-based water oxidation catalysts.

Introduction

Water electrolysis using a polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) is deemed most suitable to propel a carbon-neutral future by converting the intermittent renewable energy resources into high purity H21–5, due to its innate advantages over alkaline water electrolyzer in terms of current density and instant current response6–8. In practice, however, large-scale deployment of PEM water splitting is greatly constrained by the water oxidation catalysis half-reaction, which provides protons and electrons for hydrogen production9,10, with two essential limitations: (i) the high capital cost of scarce and expensive Ir (US$60,670 kg−1) catalysts currently used11,12; (ii) the high overpotentials and thereby low energy efficiency of Ir in catalyzing the oxygen evolution reaction (OER)13. These two limitations in combination make Ir-based catalysts difficult to meet the 2025 goal of the US Department of Energy (DOE) (H2 production cost <US $2 kgH2−1)14,15. Given this, Ru has attracted research interests worldwide with lower prices (US$9,523 kg−1), higher earth abundance, and higher intrinsic OER activity16–18. However, the inferior dissolution resistance of Ru oxides in harsh anodic and acidic conditions remains long-unsolved, making it unrealistic for practical utilization due to the limited lifespan of only dozens of hours19–22. Thus, improving the operational stability of Ru-based catalysts is highly desired23.

The lack of pertinent descriptors that could successfully capture the essential origin of the Ru inactivation in operation conditions has led to slow progress in stability improvement24. Since 1966, the over-oxidation of Ru to volatile RuO4 or soluble RuO52− at a high potential (>1.4 V) has been claimed responsible for its poor stability according to the Pourbaix diagram25–27. Thereafter, two main strategies, i.e., either introducing electron-donating elements to lower the Ru oxidation state at fixed anodic potential28–31 or enhancing the intrinsic activity to reduce the working potential of the catalysts, were adopted to extend operating life21,32. Such efforts, however, have led to only limited progress despite decades of study, and these ideas centered on the influence of bias have been challenged by a few observations in recent years. First, despite that some electron-donating elements (Sr, La, Mn, Ce, etc.) can increase the proportion of low-valent Ru species (i.e., Ru3+) and effectively suppress the Ru over-oxidation, inferior operating stabilities were still achieved on these catalysts that bind oxygen too weakly33–36. Second, it was only recently, with technological advances allowing for precise reaction mechanism probing, that the involvement of lattice oxygen in OER37 has been identified as one major cause for the extremely poor stability according to the previous work from Wohlfahrt-Mehrens and Heitbaum, in spite of boosted activity18,38–41. These demonstrations highlight the importance of the long-ignored role of the OER routes (including the reaction mechanism and binding strength of intermediates) in determining catalyst durability. However, delineating the path to constructing a well-stabilized catalyst is still highly challenging and obstructed, as it would require the development of a universal descriptor that could embody both the reaction path and binding energies in a sole structural parameter, which is currently unavailable42,43.

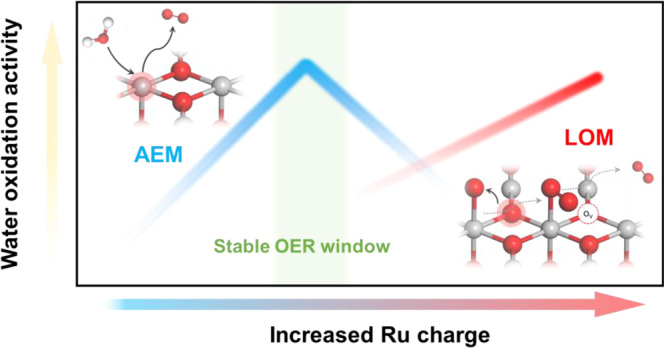

Herein, we present an intuitive descriptor, i.e., the Ru charge, to describe the overall activity and stability of the catalysts. We reveal that, despite the complexity, catalyst destabilization is in close association with Ru charge and level of difficulty in Ru-O bond breaking, i.e., the balance of formation energy between oxygen vacancy (ΔGVO) and the Ru vacancy (ΔGVRu). By varying the chelating elements surrounding the RuO6 motif via controlling the M-O-Ru structure, we succeeded not only in regulating the reaction mechanism, i.e., choosing either or not to involve the lattice oxygen into the reaction (LOM, supplementary Fig. 1a)44,45, but also in tailoring the activity and stability under adsorbate evolution reaction (AEM, supplementary Fig. 1b)46. Guided by this understanding, we screened out SnRuOx solid solution with Sn-O-Ru local structure that follows the AEM with appropriate Ru-O binding strength. The SnRuOx catalysts exhibit the high intrinsic activity of 2360 A gRu−1 at 1.48 V vs. RHE, with TOF representing the highest value reported for the catalysts following the AEM mechanism, i.e., 0.63 s−1. Moreover, the catalyst exhibits the best operational stability to date, with only a 26.8 mV increase in overpotential during the 250 h test under 100 mA cm−2 at a low catalyst loading of 41.65 μgcat cm−2. In a scalable PEM electrolyzer, an ever-smallest degradation rate of 53 μV h−1 is demonstrated during a 1300 h durability test at 1 A cm−2, which successfully extends the lifespan of Ru-based catalysts by orders of magnitude, thus unambiguously validating our idea to improve the stability. We put forward a feasible idea to construct a stable and highly-efficient Ru-based OER catalyst, which laid the foundation for the application of Ru-based materials in PEMWE.

Results

Rational design of the intuitive descriptor

We initiate by recognizing the lack of pertinent physical parameters to describe the overall performance of the Ru-based catalysts, irrespective of the reaction mechanism. Previously, reactivity descriptors, including the eg filling47,48, d band center28, p band center11, and the adsorption energy difference between catalytic sites and dopants proposed by ref. 49. were found feasible in describing the activity trend of the catalysts following either the AEM or LOM mechanism. However, a unified scale, which comprises information on activity and stability in combined reaction mechanisms (both AEM and LOM), is lacking, thereby obscuring the advancing direction of the catalysts.

We reasoned that, despite the complexity, the catalytic activity and stability are interrelated and bridged by the Ru-O bonding nature, i.e. bond covalency and level of difficulty in Ru-O bond breaking50, as follows. Weakening the Ru-O bond covalency implies the burying of the O 2p orbital under the Fermi level as well as the Ru 3d front orbital, thereby prohibiting lattice oxygen from participating in OER and the formation of oxygen vacancy (ΔGVO)45,51. In thus formed catalysts dominated by AEM, too low degree of Ru-O hybridization indicates too weak oxygen binding strength, which causes decreased Ru vacancy formation energy (ΔGVRu) and eases Ru loss52, resulting in a simultaneous decrease in activity and stability. Strengthening the Ru-O bonding will firstly lead to a moderate intermediate binding energy as well as an increased ΔGVRu under AEM, thereby improving both the activity and stability53,54. However, further increasing the bonding strength leads to arise of lattice oxygen redox, where O 2p becomes the front orbital and thereby causes lowered ΔGVO value18. Such a condition, though greatly boosts the intrinsic activity, causes the formation of oxygen defects and easy detachment of Ru-Ox moieties from defects' neck, leading to rapid catalyst degradation28,37. To this end, an appropriate performance indicator might be a physical parameter that could precisely describe the local Ru-O bonding nature.

We postulate that the Ru charge might be able to serve as such an intuitive descriptor, because it could not only perfectly reflect the local Ru-O bonding structure, i.e., the ionic or covalent bonding, but also the bonding strength. Therefore, it is possible to customize both the reaction activity and stability, using Ru charge as a regulator (Fig. 1). We, therefore, begin our study by looking for a suitable model catalyst system to verify this idea, and found that the MRuOx solid solution (M in +4 valence to avoid additional structure influence) with a clear Ru-O-M structure motif might be suitable for such a proposal. Specifically, the Ru charge can be regulated by adjusting the ionic electronegativity of M, where M4+ in higher ionic electronegativity than Ru4+ leads to reduced electron density on Ru, and vice versa. Consequently, we selected M = Ce4+, Sn4+, Ru4+, and Cr4+ with an ionic electronegativity of 1.608, 1.706, 1.848, and 1.861 to carry out our further study55,56.

Fig. 1. Relation between catalytic performance and Ru charge.

Schematic illustration of OER activity and stability of Ru-based catalysts within different reaction routes on the scale of Ru charge.

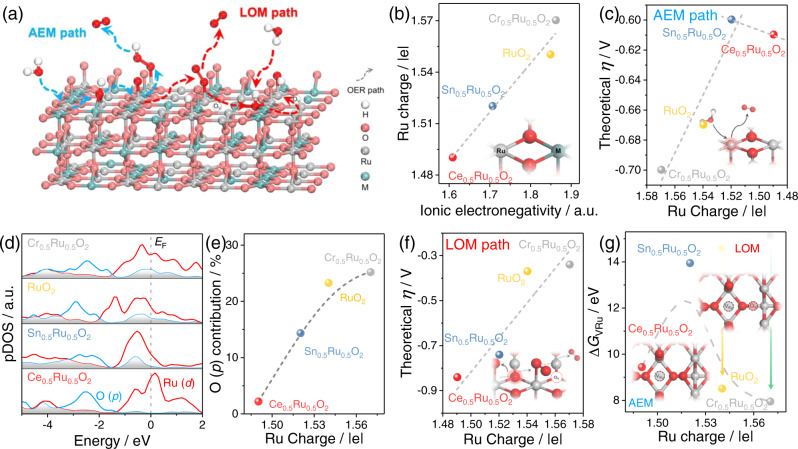

DFT calculational predictions

We firstly carried out DFT calculations with the simulation model of M0.5Ru0.5O2 with Ru-O-M motifs constructed (Fig. 2a) based on the stable rutile RuO2 (110)18,57 (Supplementary Figs. 2–6 and Supplementary Note 1). The charge of Ru in Ru-O-M was first calculated. As the electronegativity of M4+ increases from 1.608 (Ce4+) to 1.861 (Cr4+), the charge of Ru increased from 1.49 (Ce0.5Ru0.5O2) to 1.57 (Cr0.5Ru0.5O2) (Fig. 2b). We then evaluated the dependence of theoretical OER activity on the Ru charge, in both AEM and LOM reaction pathways on Ru sites, as the M sites were calculated to possess extremely poor activities under both reaction pathways (M = Ce, Sn, Cr) (Supplementary Figs. 7–13 and Supplementary Note 2).

Fig. 2. Prediction of the OER performance based on DFT calculation.

a Schematics of two OER pathway (AEM and LOM) on the surface of M0.5Ru0.5O2 (110). b The variation of Ru charge in M0.5Ru0.5O2 with an ionic electronegativity of different M. c Theoretical overpotential volcano plot under AEM pathway as a function of the Ru charge. d Projected DOS plots of Ru (d) and O (p) near the Fermi level for M0.5Ru0.5O2. The light gray filling shows the overlap between Ru (d) and O (p). e Variation of O (p) contribution near Fermi level with Ru charge. f Theoretical overpotential plot under LOM pathway as a function of the Ru charge. g The Ru vacancy formation energy (ΔGVRu) of M0.5Ru0.5O2 is characterized by Ru charge. For RuO2 and Cr0.5Ru0.5O2, ΔGVRu were calculated without (transparent dots in yellow and green) and with (opaque dots in yellow and green) the consideration of lattice oxygen vacancies. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The AEM pathway activities of the materials are revealed to follow a volcanic-like trend as a function of Ru charge. The theoretical OER overpotentials of M0.5Ru0.5O2 were calculated first, with the Sn0.5Ru0.5O2 sample exhibiting moderate Ru charge (1.52) representing the lowest theoretical OER overpotential. For the samples with both lower (Ce0.5Ru0.5O2) and higher (RuO2 and Cr0.5Ru0.5O2) Ru charge, increases in OER overpotentials are observed (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Figs. 14–17). While this phenomenon implies that an optimum Ru charge that is neither too high nor too low is beneficial for OER, the underlying reason is that Ru charge can be successfully used to reflect the Ru-O bonding interaction. Specifically, we calculated the overlap band center of Ru d orbital and O p orbital in the partial density of states (pDOS, Supplementary Fig. 18)58 and found that the overlap band center (ε-Rud-Op) takes the same trending with the change in Ru charge, i.e., increases from −4.19 to −2.95 eV with an increase in Ru charge (1.49–1.57). To this end, the Ru charge can truly be utilized as the intuitive descriptor because it reflects the status of both Ru itself and the Ru-O orbital interaction. Indeed, as the Ru charge increases, the M0.5Ru0.5O2 undergoes alteration in the potential determine step (PDS) from OH*/O* to O*/OOH* (Supplementary Figs. 13, 14), due to strengthening in Ru-O* binding, in line with bond shrinkage from 1.749 to 1.732 Å (Supplementary Fig. 19). Therefore, Ru sites charge can be successfully used to indicate the AEM reaction activity.

We then move to calculate the reactivity of lattice oxygen in different M0.5Ru0.5O2 structures and the feasibility of the LOM route. First, upshifting in O 2p band center (Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Fig. 20) and strengthening in Ru-O bond covalency are observed with increases in Ru charge, as indicated by increases in both ε-Op-Rud, O 2p band contribution near the EF (from 2.2 to 25.2%)40,59,60 and downshifted ICOHP between Ru and O (from −1.280 to −1.733 eV, Supplementary Figs. 21, 22). Second, we calculated the formation energies of oxygen vacancy(ΔGVO) in different samples, to analyze the occurrence possibility of LOM18. The significantly downshifted ΔGVO from 7.20 eV (Ce0.5Ru0.5O2) and 8.25 eV (Sn0.5Ru0.5O2) to 5.68 eV (RuO2) and 5.29 eV (Cr0.5Ru0.5O2) suggests the higher possibility of LOM involvement in RuO2 and Cr0.5Ru0.5O2 with high Ru charge (Supplementary Fig. 23). The lower ΔGVO of Ce0.5Ru0.5O2 compared to that of Sn0.5Ru0.5O2 may originate from the distortion of the crystal structure61 (Supplementary Figs. 24–27 and Supplementary Note 3). Third, we turned to calculate the LOM energy variation for M0.5Ru0.5O2 (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Figs. 28–31). Clearly, the theoretical overpotential of OER under the LOM path gradually decreases from 0.84 V for Ce0.5Ru0.5O2 to 0.34 V for Cr0.5Ru0.5O2. Therefore, the direct O-O coupling on the O p band above the EF is more thermodynamically favored with a higher Ru charge (i.e., in RuO2 and Cr0.5Ru0.5O2). Based on the above calculations, the correlation between a charge of the Ru site and the reaction path (AEM and LOM) as well as reaction energy on M0.5Ru0.5O2 (Fig. 1) is unveiled. While low charge (Ce0.5Ru0.5O2 and Sn0.5Ru0.5O2) at Ru sites leads to the domination of the AEM path, the LOM route is energetically more favored at elevated Ru charge. Moreover, by changing the Ru charge, the OER catalytic activity of catalysts following AEM can also be adjusted due to the regulation of Ru-O interaction in M0.5Ru0.5O2.

We then move to our next step, i.e., probing the applicability of the Ru charge in describing the stability of the catalysts. Two indicators, i.e., the formation energies of Ru (ΔGVRu) and O (ΔGVO) vacancies, are used jointly to describe the stability of the catalysts. On one hand, it is expected that increasing the Ru charge results in strengthened Ru-O bonding and thereby increased ΔGVRu in perfectly crystallized M0.5Ru0.5O2 samples, with ΔGVRu increasing gradually from 9.44 eV in Ce0.5Ru0.5O2 to13.92, 14.60, and 15.13 eV for Sn0.5Ru0.5O2, RuO2, and Cr0.5Ru0.5O2, respectively (Fig. 2g). On the other hand, however, increase in Ru charge causes ease formation of OV (Supplementary Fig. 23) and thereby decreases in ΔGVRu (Supplementary Fig. 32) due to lower overall Ru-O chelation number. Specifically, with the formation of one neighboring OV, the ΔGVRu value for RuO2 and Cr0.5Ru0.5O2 decreases from 14.60 and 15.13 eV to 8.51 and 7.95 eV, respectively, resulting in poor stability (Fig. 2g). To this end, the Sn0.5Ru0.5O2 near the apex of the volcano curve under the AEM path demonstrates the best stability. The rationale behind this is that the low Ru charge (Ce0.5Ru0.5O2) makes the Ru species prone to dissolution in acid, too high Ru charge leads to the readily generation of OV defects and smaller ΔGVRu, thus resulting in the overall destabilization. Since metal dissolution may occur during acidic OER, defective structures with Ru and M vacancies were also constructed for calculations (Supplementary Figs. 33–43 and Supplementary Note 4). Although the inclusion of metal center vacancies leads to the trend of crossover between AEM and LOM pathways (Supplementary Fig. 44), in line with recent work from Alexandrov et al.62,63, Ru charge is still valid in describing the reaction path and energy as the vacancies influence the Ru charge and OER reaction in the same way. Specifically, the inclusion of vacancies leads to the evolution of the Ru-O bonding feature and thereby Ru charge (Supplementary Fig. 45 and Supplementary Note 5), which thus determines the theoretical activity under different paths. As a result, the theoretical performance of defective M0.5Ru0.5O2 on the scale of Ru charge perfectly matches that of the non-defective structure. To here, it is clear that the Ru charge can be used to describe not only the major reaction path and OER activity, but also the structural stability, due to its successful reflection in both electronic features of Ru and overall Ru-O bonding interactions (Fig. 1).

Synthesis and characterization

To experimentally validate the DFT prediction, MRuOx oxide solid solution with a M/Ru ratio close to 1 was synthesized according to the previous reports (see Methods for details)16,35. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns show that all prepared MRuOx samples possess a rutile-type structure without any distinct diffraction peaks corresponding to MOx and RuO2 (Supplementary Fig. 46), indicating the formation of MRuOx oxide solid solution, in line with the uniform elements distribution revealed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) (Supplementary Figs. 47–50). Rietveld refinement analysis (Supplementary Fig. 51 and Supplementary Table 1) suggests the random displacement of Ru by M in MRuOx solid solution, giving the formation of Ru-O-M structure motif (Supplementary Fig. 52). The atomic ratios of M and Ru were close to 1, as analyzed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) and EDX (Supplementary Fig. 53 and Supplementary Table 2).

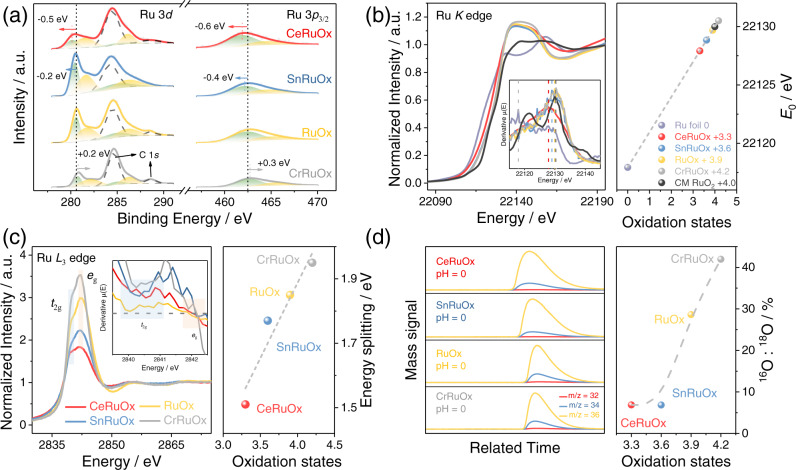

We then move on to probe the local structure and chemical states of Ru and O in MRuOx. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) show that both Ru 3d and Ru 3p3/2 (Fig. 3a) signals could be deconvoluted into two doublets, representing Ru4+ (fill in green) and the satellite peaks (fill in yellow)54,64. Notably, the Ru 3d and Ru 3p binding energies for CeRuOx (280.1 and 461.9 eV), SnRuOx (280.4 and 462.1 eV), RuOx (280.6 and 462.5 eV), and CrRuOx (280.8 and 462.8 eV) consecutively shifted to more positive values, implying a successive increase in Ru valence states, in line with the DFT calculation results. We further collected the Ru K edge spectra through X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy (XANES) to quantitatively describe the oxidation state of Ru. As presented in Fig. 3b, taking Ru foil and commercial RuO2 as references, the oxidation states of Ru in MRuOx were estimated to be +3.3, +3.6, +3.9, and +4.2 for CeRuOx, SnRuOx, RuOx, and CrRuOx, respectively. The variation in Ru valence and its consistency with DFT calculation results verifies the feasibility of tailoring the Ru electron density via controlling the element M in the Ru-O-M motif, making it promising for reaction path and O* adsorption energy regulation.

Fig. 3. Structure properties of MRuOx oxide solid solution experimentally obtained.

a High-resolution Ru 3d and Ru 3p3/2 XPS pattern of MRuOx, demonstrating the variation of Ru chemical states. b Ru K edge XANES spectra and corresponding first derivative (insert in the left part of b) of MRuOx, Ru foil, and oxidized commercial RuO2. The right part of b show the relation between the Ru K-edge absorption energy (E0) and oxidation states for MRuOx and reference samples. c Ru L3-edge XAS spectra and the corresponding second derivative (insert in the left part of c) of MRuOx. The right part of c illustrated the relation between the energy splitting ΔE and Ru oxidation states of MRuOx. d DEMS signals of 32O2 (16O16O), 34O2 (16O18O), and 36O2 (18O18O) from the reaction products for MRu16Ox in H18O aqueous sulfuric acid electrolyte. The right part of d presented the variation of the 16O: 18O ratio with Ru oxidation states of MRuOx. The dashed lines in c and d are used to guide the eyes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next turned to validate experimentally if the OER path of MRuOx truly follows the DFT calculation results as a function of Ru charge, initiated by monitoring the Ru-O bond covalency via Ru XANES spectrum at L3 edge (Fig. 3c)65. As reported previously, the Ru XANES spectrum at the L3 edge can be fitted by two peaks ascribable to eg and t2g, and the energy splitting ΔE (ΔE = Eeg - Et2g) is positively correlated with the Ru-O bond covalency. Notably, we find that ΔE increases from 1.51 to 1.95 eV (Fig. 3c, right) with the increase in valence state (+3.3 to +4.2), thus testifying to the greatly enhanced Ru-O bond covalency with increased Ru charge, in line with the increase in Rud–Op overlap in the calculation (Fig. 2d, e). O 1 s XPS spectra (Supplementary Fig. 54 and Supplementary Table 3) further suggest significant increases in OV contents in RuOx (36%) and CrRuOx (41%) compared with that of CeRuOx (25%) and SnRuOx (15%), in good compliance with the increase in bond covalency11. The occurrence of LOM is further verified by in situ 18O isotope-related DEMS measurements on all MRuOx samples (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Figs. 55–63, and Supplementary Note 6) according to the previous reports66–68. By extrapolating the integration of the mass spectra signal (16O/18O) per second to the OER onset, the content of the LOM path during OER is determined (Supplementary Figs. 55–63e). Specifically, the AEM path is revealed to be dominant on CeRuOx and SnRuOx, as the 16O/18O ratio of O2 catalyzed by CeRu16Ox and SnRu16Ox in 18O-labeled 0.5 M H2SO4 is 6.88 and 6.85% (Supplementary Figs. 56, 57e), respectively, which is consistent with that of the commercial IrO2 (6.56%, Supplementary Fig. 55), attributable to the isotopic abundance of 16O in H218O. On Ru18Ox and CrRu18Ox, however, the 16O/18O ratio in products significantly increased to 28.63 and 41.96%, leading to an increment in the LOM ratio of RuOx and CrRuOx to 12.6 and 36.7%, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 58–59). Besides, the DEMS measurements in 18O-labeled 0.1 M PBS (pH = 6) also demonstrate similar results (Supplementary Figs. 60–63). It is noted that the LOM ratio differs significantly in literature as reported by refs. 67–69, etc., mainly owing to the difference in structural properties of the catalysts, while our result is in high accordance with that reported by ref. 38, due to the similar solid solution structure (Supplementary Note 7). To here, it is clear that the Ru charge is a useful parameter to customize the OER path on MRuOx.

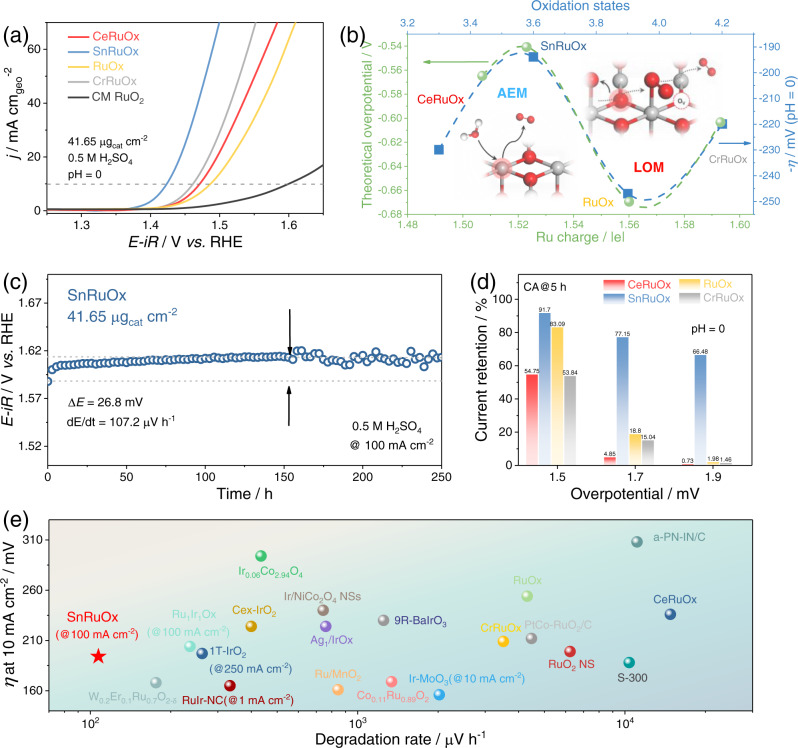

OER catalytic performance in a three-electrode configuration

The OER performance of the prepared MRuOx was firstly evaluated in a conventional three-electrode setup at a catalyst loading of 41.65 μgcat cm−2 (Supplementary Figs. 64, 65 and Supplementary Note 8) with 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte according to the guideline recently set70,71. The linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves normalized by the geometric area (Fig. 4a), electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) (Supplementary Fig. 66a, b), Ru mass loading on the electrode (Supplementary Fig. 66c) and corresponding Tafel slopes (Supplementary Fig. 66d–f) revealed the variation in OER catalytic activity of MRuOx. As summarized in Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 67, the activity trend of MRuOx is in good agreement with DFT prediction. Specifically, on samples dominated by AEM path (CeRuOx and SnRuOx), the OER activity is significantly enhanced with an increase in Ru charge (strengthened O* adsorption), accompanied by the variation in reaction determine step as indicated by the difference in Tafel slope (60.2 and 38.2 mV dec−1) (Supplementary Fig. 66d and Supplementary Note 9). Further increase in the Ru charge leads to a performance decline in AEM but the occurrence of LOM. Therefore, an activity drop in RuOx and a slight lift in CrRuOx are observed, in line with the DFT calculation. Notably, the SnRuOx customized near the apex of AEM exhibited remarkable OER catalytic activity. Satisfactorily, a small catalytic overpotential (η) of 194 mV is needed for SnRuOx to deliver a current density of 10 mA cm−2, which is 176 mV lower than that of commercial RuO2 (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, the mass activity and turnover frequency (TOF) of SnRuOx at 1.48 V vs. RHE is 36.4 times that of commercial RuO2, reaching 2360 A gRu−1 and 0.63 s−1 (Supplementary Fig. 68). These results unambiguously suggest SnRuOx as one of the most active Ru-based catalysts towards acidic OER (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 4).

Fig. 4. Electrocatalytic performance of MRuOx in three-electrode setup.

a Geometric area normalized LSV curves of MRuOx. b The variation of apparent overpotential at 10 mA cm−2 with Ru oxidation states. The theoretical overpotential of MRuOx is the weighted value of the theoretical activity of different reaction mechanisms to its proportions (from Supplementary Fig. 56-59). The apparent overpotential experimentally obtained is given as the blue dots scaled with the right Y-axis. The theoretical overpotential is given as the green dots scaled with the left Y-axis. c Chronopotentiometry curve of SnRuOx nanocatalyst operated at 100 mA cm−2 during the 250 h test. d Current retention of MRuOx after chronoamperometry test at various potentials (1.5 V, 1.7 V, and 1.9 V) for 5 h. e Comparison of OER performance (η at 10 mA cm−2 and activity degradation rate) for variously reported electrocatalysts. SnRuOx is presented by a red star. The electrocatalytic performance is collected with a catalyst loading of 41.65 μgcat cm−2. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We then tested the stability of MRuOx during operation to probe into the effectiveness of Ru charge in describing the stability. To start with, chronoamperometry (CA) tests (5 h) suggest SnRuOx as the most stable catalyst, with high current retention of 91.7, 77.15, and 66.48% after operating at 1.5, 1.7, and 1.9 V vs. RHE, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 69). By contrast, the CeRuOx, CrRuOx, and RuOx only demonstrate current retention of 54.75, 83.09, and 53.84% at 1.5 V vs. RHE, respectively, implying their poor stability. Furthermore, to eliminate the interference of other factors beyond the catalyst, i.e., thin film quality72,73, active sites blockage74, and back electrode passivation75,76, the stability of MRuOx was evaluated by monitoring the dissolution behavior of M and Ru during CA tests. By calculating the Ru stability number (S-number)77 during CA tests, the stability of MRuOx is found to be in line with the ΔGVRu from the DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. 70). Given the perfect match in catalytic stability between experiments and theoretical computations, we further run a CP test at 100 mA cm−2 for the SnRuOx sample to verify its stability (Fig. 4c). Excitingly, during a 250 h test, the overpotential only increased by 26.8 mV, giving a degradation rate of merely 107.2 μV h−1, three orders of magnitude smaller than that of commercial RuO2 (Supplementary Fig. 71) and comparable to that of the advanced Ir-based catalysts (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Tables 5, 6)12,14,18,19,38,52–54,78–90. Besides, by carrying out CA tests in a weak acidic environment (0.1 M PBS, pH = 6), the contribution of M (M = Ce, Sn, and Cr) dissolution on the performance degradation of MRuOx is eliminated (Supplementary Figs. 72, 73 and Supplementary Note 10), further demonstrating the stability of MRuOx is dependent on the Ru stability. These results corroborate the effectiveness of the Ru charge not only in describing the trend in catalytical activity, but more importantly, in screening out the most durable catalysts ever reported.

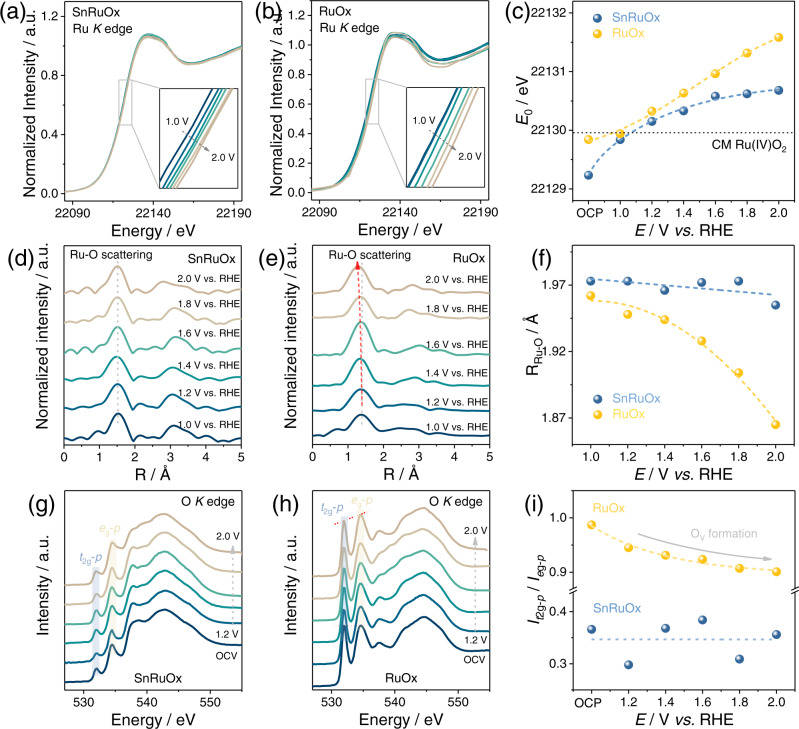

The origin of the high stability

To further probe into the stabilization mechanism of SnRuOx during OER operation, we adopted in situ XAS and in situ Raman spectroscopy to investigate the dynamic variation in local Ru structure and chemical environment. RuOx was also tested as the counterpart catalyst for comparison. According to the literature, the over-oxidation of Ru originating from the structure damage under high oxidation potential is one of the main culprits leading to severe Ru dissolution91. Thus, Ru K edge XANES spectra were collected to monitor the change in Ru oxidation states of SnRuOx and RuOx during operation. As presented in Fig. 5a, b and summarized in Fig. 5c, SnRuOx and RuOx show big differences in Ru valence states during operation (Supplementary Fig. 74), especially at higher applied potentials. Specifically, switching on the electrode potential from open circuit potential (OCP) to 1.4 V vs. RHE leads to a rapid rise in Ru valence from +3.6 to +4.2 in SnRuOx, followed by a gentle and steady change from +4.2 to +4.4 with potential further lifted to 2.0 V vs. RHE. On the contrary, the Ru oxidation states in RuOx increase at a constant rate from +3.9 to +4.9 with the applied potential ranging from OCP to 2.0 V vs. RHE, showing no sign of stabilization. This result indicates that even at high oxidation potentials, the stable structure of SnRuOx can be maintained under the customized AEM path, whereas RuOx undergoes significant structural evolution, probably ascribable to the involvement of LOM.

Fig. 5. Investigating the stability mechanism of SnRuOx during OER with RuOx as control.

a, b In situ Ru K edge XANES spectra of SnRuOx (a) and RuOx (b) with applied bias rise from 1.0 V to 2.0 V vs. RHE. c The variation trend of Ru K-edge absorption energy (E0) of SnRuOx and RuOx under different potentials. d, e Fourier transforms of k2-weighted EXAFS signals of SnRuOx (d) and RuOx (e) with applied bias rise from 1.0 to 2.0 V vs. RHE. f Summary of the Ru-O bond length of SnRuOx and RuOx under various potentials according to the quantitative fitting results (Supplementary Table 7). g, h Quasi in situ O K edge XAS TEY spectra of SnRuOx (g) and RuOx (h) with an applied potential increase from 1.2 to 2.0 V vs. RHE. i The variation of It2g-p/Ieg-p with applied potential for SnRuOx and RuOx. The dashed lines in c, f, i are used to guide the eyes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We then carried out in situ Raman spectroscopy to clarify the structure evolution during OER. For both SnRuOx and RuOx, two major peaks at ~435 and 595 cm−1 assignable to Eg and A1g vibration modes were observed (Supplementary Fig. 75)92,93. With the potential increases from OCP to 1.8 V vs. RHE, the SnRuOx sample maintains a constant Raman shift, suggesting the consistency in Ru-O bonding structure during OER. However, a ca. 9 cm−1 positive shift in RuOx is noticed, implying the shrinkage in Ru-O bonding length during OER. To intuitively uncover the local structure evolution of SnRuOx and RuOx during OER, Fourier transforms (FTs) analysis of extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra was carried out to provide R-space information. A prominent peak of ~1.45 Å (phase uncorrected) corresponds to the first Ru-O coordination shell can be observed (Fig. 5d, e and Supplementary Figs. 76, 77) for both samples. Interestingly, while only small fluctuations in Ru-O bond length (rRu-O) are observed for SnRuOx (from 1.97 to 1.96 Å) with potential increases from 1.0 to 2.0 V vs. RHE, a significant rRu-O shrinkage from 1.96 to 1.86 Å is observed in RuOx (Fig. 5f), in well accordance with the Raman results. Meanwhile, while quantitative Ru K edge fitting results (Supplementary Table 7) show no significant change in Ru-O coordination number (CN) for SnRuOx, a significant decrease in CN from 6.4 to 4.7 is evidenced in RuOx, ascribable to the generation of OV due to the occurrence of LOM.

We further performed quasi in situ soft-XAS measurements to collect the O K edge information, to directly evidence the formation of OV by recording the total electron yield (TEY) intensity before and after operating under different potentials. Two pre-edge peaks at ~532 and 534.5 eV assignable to the unoccupied orbital of O 2p hybridized with Ru 4d t2g and eg orbitals are observed for both SnRuOx and RuOx (Fig. 5g–i)45. According to previous reports, the reduction in t2g-p/eg-p peak intensity (It2g-p/Ieg-p) implies the formation of the OV due to the electron occupation of the lowest energy state (t2g) of octahedral symmetry94,95. For RuOx, the ratio of It2g-p/Ieg-p decreases monotonously with potential increases from 1.2 to 2.0 V vs. RHE, implying the generation of a high amount of OV during OER. On the contrary, no obvious variation in It2g-p/Ieg-p is observed for SnRuOx, suggesting that there is no increase in OV content and thus ruling out the occurrence of LOM, which endows it with excellent operational stability. These results are in good agreement with the catalyst design idea as SnRuOx was customized to follow the AEM path and exhibited high stability during OER due to moderate Ru charge.

Performance of PEMWE devices

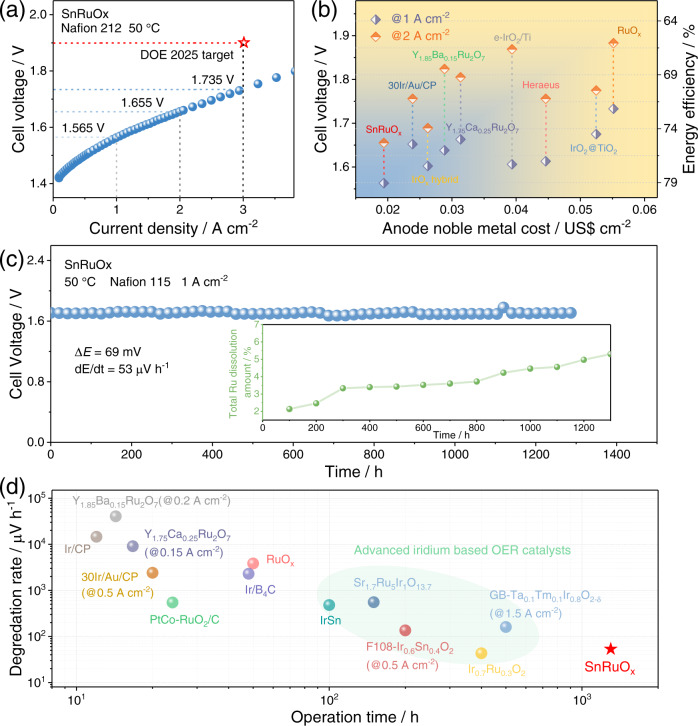

Encouraged by the overall high activity and stability of SnRuOx towards OER, we finally assembled a single cell using the catalyst as the anode to evaluate its performance in a real PEMWE device (Supplementary Fig. 78, see Methods for details). The steady-state polarization curve of membrane electrode assemblies (MEAs) operated at 50 °C (Fig. 6a) shows that the performance of PEMWE can be greatly improved with the utilization of SnRuOx. Specifically, cell voltages of only 1.565, 1.655, and 1.735 V are needed to reach current densities of 1, 2, and 3 A cm−2, respectively, far superior to that obtained with commercial RuO2 (1.733 V@1 A cm−2 and 1.883 V@2 A cm−2) (Supplementary Fig. 79) and also well surpassing the DOE 2025 target (3 A cm−2@1.9 V)96. Taking noble metal cost and cell performance into account, the overall advantages of SnRuOx are self-evident (Fig. 6b). With anode noble metal cost of US$ 0.0194 cm−2, high energy efficiencies at 78.7 and 74.3% were achieved at 1 and 2 A cm−2, respectively, corresponding to energy consumptions at 41.9 and 44.4 kWh kg−1H2, outperforming the prior reported most cost-efficient OER catalysts (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Table 8, and Supplementary Note 11)20,97–102. According to the calculation from US DOE, only US$ 0.838 is required for this PEMWE device to produce 1 kg H2, which is much lower than the DOE target (<US$2 kgH2−1), further proving the efficiency of the SnRuOx at the anode.

Fig. 6. Performance of PEM electrolyzer using SnRuOx as anode electrocatalyst.

a Polarization curve of the PEM electrolyzer obtained at 50 °C with Nafion 212 membrane. b Comparison of the efficiency of previously reported anode electrocatalysts. The X-axis represents the anode noble metal cost (Supplementary Table 8). The left and right Y-axis represent the cell voltage and energy efficiency at 1 and 2 A cm−2 respectively. c Chronopotentiometry curve of the PEM electrolyzer using SnRuOx catalyst operated at 1 A cm−2 at 50 °C with Nafion 115 membrane. Insert in c show the total dissolution amount of Ru during the 1300 h test. d Comparison of the operational stability (operation time and performance degradation rate) of SnRuOx with reported anode catalysts. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The long-term operational stability is even more exciting, as shown in Fig. 6c, the SnRuOx-based cell demonstrates well-maintained PEMWE performance after running under 1 A cm−2 for 1300 h, with apparent degradation rate only at 53 μV h−1. Such stability not only represents a record for Ru-based catalysts, but even superior to that of the advanced Ir-based OER catalysts recently reported (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Table 9)14,20,38,52,97,99,103–107. To more accurately determine the lifetime of SnRuOx in PEMWE, a modified MEA setup without metallic parts in the anode and cathode water cycle was employed according to the previous reports (Supplementary Fig. 80–84, Supplementary Table 10, and Supplementary Note 12)108. With all the Ru dissolved in the anode/cathode water and membrane monitored during 10 h operation at 1 A cm−2, the S-number of SnRuOx is calculated to be 1.04 × 106 (Supplementary Note 13)77. These results reveal the inherently robust nature of SnRuOx as an OER catalyst with highlighted practical application prospects.

Discussion

In summary, we presented a practical and feasible idea, namely customizing the reaction route, to design a highly active and stable Ru-based OER catalyst that can afford long-term operation in PEMWE devices. Based on the widely recognized OER mechanism, we found that Ru charge can be used as a scale for the reaction path of the catalyst, only those located close to the apex of the volcano plot in AEM can exhibit optimal stability. Subsequently, we verified the feasibility of this idea in an MRuOx model catalyst. By screening M4+ with different ionic electronegativity, the Ru charge can be effectively regulated attributed to the charge redistribution effect in a Ru-O-M structure motif. As a result, the SnRuOx customized exhibited unparallel OER catalytic activity and stability. A PEMWE device assembled with SnRuOx as an OER catalyst can afford a cell voltage of only 1.565 V at 1 A cm−2 as well as long-term stability over 1300 h with a degradation rate of only 53 μV h−1. This work provides a rational catalyst design concept at the level of reaction path customization, and provides a feasible solution for the practical application of Ir-free Ru-based catalysts in commercial PEMWE systems.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals were obtained from commercial suppliers at analytical grade and used as received without further purification. The commercial RuO2 and Water−18O (H218O) were purchased from Aladdin. Carbon paper was obtained from Engineered Fibers Technology, LLC. Commercial Pt/C (40 wt% Pt) catalyst was purchased from Johnson Matthey Company. Titanium felt were purchased from Bekaert New Materials. 5 wt% Nafion® ionomer, Nafion 115 membrane, and Nafion 212 membrane were purchased from DuPont Co. The L shape gold electrode with an area of 0.07065 cm2 is obtained from Tianjin Aida Hengsheng Technology Development Co., Ltd.

Preparation of CeRuOx solid solution

The CeRuOx solid solution was fabricated via a pyrolysis-thermal annealing strategy. Typically, glucose, RuCl3, and CeCl3·7H2O were mixed and dried to obtain a xerogel with Ru and Ce uniformly distributed. Then the precursor was heated in air at 350 °C for 5 h with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. After cooling to room temperature, the collected samples were carefully ground and ultrasonically washed in 1 M HCl for at least 6 h to remove acid-labile components.

Preparation of SnRuOx solid solution

The SnRuOx solid solution was prepared following the procedure of ion exchange and thermal annealing. Firstly, an Sn-based metal-organic framework (MOF) was fabricated according to the previous reports. The ethanol solution of SnCl4 and HMTA (Hexamethylenetetramine) is uniformly mixed and stirred at room temperature for 1 h, washed, and dried to obtain Sn-HMTA. Then Sn-HMTA were dispersed in the THF (Tetrahydrofuran) solution of RuCl3. After stirring for 24 h, the mixture is centrifuged and washed with THF to obtain an Sn/Ru-HMTA precursor. The dried products are conducted to heat treatment in air at 350 °C for 5 h with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. After cooling to room temperature, the collected samples were carefully ground and ultrasonically washed in 1 M HCl for at least 6 h to remove acid-labile components.

Preparation of RuOx

The preparation process of RuOx is similar to that of SnRuOx. The THF solution of RuCl3 and HMTA was ultrasonically mixed and stirred at room temperature for 24 h, followed by centrifugation and washing. After drying in the oven, the Ru-HMTA precursor were annealed at 350 °C for 5 h with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1 in air. After cooling to room temperature, the collected samples were carefully ground and ultrasonically washed in 1 M HCl for at least 6 h to remove acid-labile components.

Preparation of CrRuOx solid solution

The CrRuOx solid solution were prepared according to the previous reports. The Cr, Ru containing precursors were obtained by mixing RuCl3 and MIL-101(Cr) in THF and stirring for 24 h. The result RuCl3-MIL-101(Cr) were then heated to 450 °C and held for 5 h in air with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. After cooling to room temperature, the collected samples were carefully ground and ultrasonically washed in 1 M HCl for at least 6 h to remove acid-labile components.

Structural characterizations

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected using a Rigaku Smartlab diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) in the scan range of 10° to 90° at a step of 0.01°. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) measurements were performed on an XL 30 ESEMFEG field emission scanning electron microscopy. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), and elemental mapping analysis were performed on a Philips TECNAI G2 electron microscope operating at 200 kV. High-annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images were performed on a Titan 80-300 scanning/transmission electron microscopy operated at 300 kV. The surface electronic states were determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) using a Thermo Fisher Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi unit with Al-Kα (1486.6 eV) as the X-ray source. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES; X Series 2, Thermo Scientific USA) was used to determine the ratio of M/Ru in the as-prepared samples and the dissolution of M and Ru after the stability tests.

XAFS data collection and analysis

The ex situ and in situ Ru K-edge XAFS measurements were performed at BL14W1 station in Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF, 3.5 GeV, 220 mA maximum, Si(111) double crystals). The Ru K-edge spectra of the samples were collected in transmission mode using a Lytle detector. The XAFS raw data were background-subtracted and normalized by the ATHENA program. Least-squares curve-fitting analysis of the EXAFS χ(k) data (including different coordination shells, in the R-space (1.0−3.0 Å)) and Fourier transforms (in the k-space 3.1−11.0 Å−1) were carried out using the ARTEMIS program. The theoretical scattering amplitudes, phase shifts, and the photoelectron mean free path for all paths were calculated by using a Hanning window (dk = 1.0 Å−1) in the IFEFFIT package. The data were fitted in R-space with theoretical models constructed on the basis of the crystal structure derived from XRD. The ex situ Ru L3 edge measurements were carried out at the soft X-ray microcharacterizaiton beamline (SXRMB) in Canadian Light Source (CLS). The O K edge XAFS was measured at the BL08U1A beamline, SSRF.

Electrochemical measurements in a three-electrode cell

The electrochemical performance of the as-prepared catalysts were measured in a standard three-electrode cell on PARSTAT MC (AMETEK®). The electrocatalysts (1 mg) were dispersed in a mixture of 0.890 mL ethanol, 100 μL ethylene glycol, and 10 μL Nafion® solution (5 wt%). The ethylene glycol is introduced to improve the quality of the catalyst thin film and suppress the coffee-ring effect according to the previous work from ref. 6. After ultrasonication for 1 h, the desired amount of homogeneous ink was dropped on a polished L shape gold electrode (area 0.07065 cm−2) and dried in an oven (60 °C) for 30 min and then serve as a working electrode. After loading optimization, the mass loading of the sample catalyst and controls are determined to be 41.65 μgcat cm−2. The Ru loading on the electrode is estimated to be 13.44, 15.21, 25.50, and 19.02 μg cm−2 for CeRuOx, SnRuOx, RuOx, and CrRuOx, respectively. The electrochemical testing is carried out in a conventional three-electrode set-up with a carbon rod and a mercurous sulfate electrode (Hg/Hg2SO4) used as the counter electrode and reference electrode respectively. O2-saturated 0.5 M H2SO4 was used as an electrolyte to mimic the environment of the anode in PEMWE. When conducting LSV, CA, and CP tests, the electrolyte is convected by external magnetic stirring with a speed of 300 rpm, which is sufficient to remove the visible oxygen bubble formed on the surface of the Au electrode. When collecting the CV for ECSA calculation, no magnetic stirring is applied. To conduct the CP at 100 mA cm−2, the working electrode is prepared by air spraying the homogeneous catalyst ink on a piece of carbon paper (area 1 × 1 cm−2) with optimized catalyst loading (41.65 μgcat cm−2). All the electrochemical testing in a three-electrode set-up is conducted at 30 °C. To investigate the dissolution of M during OER, O2-saturated 0.1 M PBS (pH = 6) was also used as an electrolyte. For the measurement with iR-correction, R was referred to as the ohmic resistance arising from the electrolyte/contact resistance of the setup. The iR compensation was performed manually after the measurement for 100% of the R.

Determine the ECSA of MRuOx

The ECSAs were obtained from the electrochemical double-layer capacitance of the catalytic surface. The electrical double-layer capacitor (CDL) were measured from double-layer charging curves using cyclic voltammograms in a non-Faradaic region with a scan rate from 5 to 25 mV s−1. The CDL was measured by the following equation:

| 1 |

where j is the no-Faradaic capacitive current obtained from the CV curve, ν is the scan rate. The slope of j-ν curve is regarded as CDL. The ECSA is calculated from the double-layer capacitance according to:

| 2 |

Where CS is the specific capacitance of the sample (set as 0.035 mF cm−2 according to the previous reports).

Mass activity calculation

The mass activity (jmass) of MRuOx were determined using the following equation:

| 3 |

where igeo is the geometric current (A) obtained from LSV, mcat is the loading of catalysts on the electrode and Ru wt% is the mass ratio of Ru in MRuOx, which is calculated from the results of ICP-OES.

Calculation of the TOF

The TOF of MRuOx and commercial RuO2 were calculated based on the following equation:

| 4 |

where is the number of oxygen per second, is the number of Ru participating in the OER. Here in this work, all Ru on the electrode are assumed to be the active center during OER. Thus, the can be calculated as:

| 5 |

in which is the molar mass of Ru (101.07 g mol−1). and are same as those in Eq. 3.

The in Eq. (4) were calculated from the LSV curve by the following equation:

| 6 |

where is the geometric current (A), z is the number of electrons required per oxygen molecule, F is the Faraday constant (96,484 C mol−1).

In situ DEMS with isotope labeling

In situ DEMS experiments was performed on an in situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometer provided by Linglu Instruments (Shanghai) Co. Ltd with a delay time of 1 s. A porous PTFE membrane is employed for gas-liquid separation. A typical test was carried out in a three-electrode cell with 18O-labeled 0.5 M H2SO4 or 18O-labeled 0.1 M PBS as electrolyte and MRu16Ox as a catalyst. Before the DEMS measurement, cyclic voltammetry was performed in the range of 0.6 − 1.2 V at 50 mV s−1 to further purge the adsorbed 16O species on the electrode. After these processes, the in situ DEMS measurement was carried out with five consecutive LSV test on MRuOx. To exclude the influence of the abundance of 16O in H218O, control experiments on commercial IrO2 were carried out. The total signal intensity of O2 is calculated to determine the OER onset potential.

Electrochemical measurements in PEM electrolyzer

To construct the membrane electrode assembly (MEA), SnRuOx or commercial RuO2 were used as the anode catalysts, and commercial Pt/C (40 wt%) was used as the cathode catalyst. To prepare the anode and cathode ink, catalysts were dispersed to a mixture of isopropanol and distilled water with a ratio of 1:1. Then, Nafion® solution (5 wt%) was added in to obtain an ionomer amount of 30 wt% for an anode and 40 wt% for a cathode. After ultrasonicated for at least 1 h in a low-temperature water bath, a uniform catalyst ink can be obtained.

To prepare the MEA with Nafion 212 membrane as an electrolyte, the anode and cathode catalysts were directly air sprayed on the two sides of the as-received Nafion 212 membrane in the ultrasonic spray coating system. The anode and cathode catalysts loading are controlled to be 4 mgcat cm−2 (1.46 mgRu cm−2) and 1 mg cm−2 (0.4 mgPt cm−2) after loading optimization. To prepare the MEA with Nafion 115 membrane as an electrolyte, the anode and cathode catalysts are first sprayed onto sheets of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). After that, the PTFE-supported Pt/C, Nafion 115, and PTFE-supported anode catalysts are hot pressed together at 135 °C for 3 min under a pressure of 2 T. After cooling, the PTFE on the surface were carefully peeled off to get the catalyst-coated membrane (CCM). The anode and cathode catalysts loading are controlled to be 2 mgRu cm−2 and 1 mg cm−2 after loading optimization. The CCM prepared was preserved in distilled water for further measurements.

To construct the PEM electrolyzers for performance evaluation, the titanium felt with a thickness of 1 mm were used as the porous transport layers (PTL) in both the anode and cathode. The assembly pressure of the fixture is set to 5 N m. The active area of the electrode is measured to be 4 cm2.

The PEM electrolyzers were operated at 80 °C with distilled water as reactant under a flow rate of 40 mL min−1. The polarization curves were collected from 0.1 to 4.4 A cm−2. The stability of the PEM electrolyzers were evaluated by measuring chronopotentiometry at 1 A cm−2 for 1300 h. The anode dissolution amount were monitored every 100 h by ICP-OES.

DFT calculation

The geometries and energies were performed by density functional theory (DFT) with Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)109–116. The interactions between ion cores and valence electrons were described by the projector augmented wave (PAW) method. The generalized gradient approximation with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof was adopted as the exchange-correlation functional. The wave functions at each k-point were expanded with a plane wave basis set. The kinetic cutoff energy was set to 400 eV. The integration of the Brillouin zone is conducted using a 1 × 1 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack grid. The geometries were optimized using a force-based conjugate-gradient method until the energy was converged to 1.0 × 10−4 eV/atom and the force to 0.05 eV/Å. Spin polarization was considered in our current study and the U parameter used for M atoms was 4.0 eV.

The structure of M0.5Ru0.5O2 were based on the results from XRD refinement. M0.5Ru0.5O2 (110) was constructed by cutting the bulk M0.5Ru0.5O2 alone in 110 direction and four layers were selected. For defective structures, Ru and M vacancies are considered (see Supplementary Note 4). During the optimization, the up-layer atoms were allowed to relax and the atoms in the last layer were fixed to keep the bulk structure. A vacuum layer of 15 Å was used along the c direction normal to the surface to avoid periodic interactions.

To illustrate the activity of AEM (adsorbate evolution mechanism) and LOM (a lattice-oxygen-mediate mechanism), the free energy diagrams was estimated as follows:

where ΔE is the total energy change based on the DFT calculations, ZPE and S is the zero-point energy and entropy, respectively, T is the temperature (here, 298.15 K is selected). The free energy of (H+ + e-) at standard conditions is assumed as the energy of 1/2 H2.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Thank the National Key R&D Program of China (No 2021YFB4000200, W.X.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21875243, J.G., U1601211, J.G., and 21733004, J.G.), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA21090400, W.X.), the Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Program (20190201300JC, 20170520150JH, and 20200201001JC) for financial support. Thank the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for conducting the X-ray absorption spectroscopy experiments at BL08U1A and BL14W1 station. Part of the computational time is supported by Jilin University, the High-Performance Computing Center of Jilin Province, Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, and the supercomputing system in the Supercomputing Center of the University of Science and Technology of China.

Source data

Author contributions

Z.S. and J.G. conceived the experimental ideals. Z.S. synthesized the catalysts. Z.S., J.L., Yib.W., J.Z., Z.J., L.Z., and J.G. performed the physical characterization and results discussion. Z.S. and Yin.W. conducted the theoretical calculations. S.L., J.Y., X.W., J.N., and C.L. helped analyze the results. Z.S., W.X., and J.G. wrote the manuscript. All the authors commented on the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiaoming Cao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. All other relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ying Wang, Email: ywang_2012@ciac.ac.cn.

Wei Xing, Email: xingwei@ciac.ac.cn.

Junjie Ge, Email: gejj@ciac.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-36380-9.

References

- 1.Lagadec MF, Grimaud A. Water electrolysers with closed and open electrochemical systems. Nat. Mater. 2020;19:1140–1150. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-0788-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seitz LC, et al. A highly active and stable IrOx/SrIrO3 catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Science. 2016;353:1011–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li A, et al. Enhancing the stability of cobalt spinel oxide towards sustainable oxygen evolution in acid. Nat. Catal. 2022;5:109–118. doi: 10.1038/s41929-021-00732-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin C, et al. In-situ reconstructed Ru atom array on α-MnO2 with enhanced performance for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Catal. 2021;4:1012–1023. doi: 10.1038/s41929-021-00703-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei Ju-Cai SLWX. Simultaneous hydrogen and (NH4)2SO4 productions from desulfurization wastewater electrolysis using MEA electrolyser. J. Electrochem. 2022;28:2112211. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao F, et al. Increasing iridium oxide activity for the oxygen evolution reaction with hafnium modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:15616–15623. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c03473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmo M, et al. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 2013;38:4901–4934. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.01.151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie Wen-Fu SM-F. Alkaline water electrolysis for efficient hydrogen production. J. Electrochem. 2022;28:22014008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nong HN, et al. Key role of chemistry versus bias in electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Nature. 2020;587:408–413. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2908-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nong HN, et al. A unique oxygen ligand environment facilitates water oxidation in hole-doped IrNiOx core–shell electrocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:841–851. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0153-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuznetsov DA, et al. Tailoring lattice oxygen binding in ruthenium pyrochlores to enhance oxygen evolution activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:7883–7888. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li N, et al. Identification of the active-layer structures for acidic oxygen evolution from 9R-BaIrO3 electrocatalyst with enhanced iridium mass activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:18001–18009. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c04087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, et al. Significantly enhanced overall water splitting performance by partial oxidation of Ir through Au modification in core-shell alloy structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:4639–4645. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c12740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hao S, et al. Torsion strained iridium oxide for efficient acidic water oxidation in proton exchange membrane electrolyzers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021;16:1371–1377. doi: 10.1038/s41565-021-00986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guido, B. & Dinh, H. N. HydroGEN: Low-temperature Electrolysis (LTE) and LTE/Hybrid Supernode. Report No. NREL/PR-5900-76549 (National Renewable Energy Lab, 2020)

- 16.Lin Y, et al. Chromium-ruthenium oxide solid solution electrocatalyst for highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:162. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08144-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao L, et al. Dynamic oxygen adsorption on single-atomic Ruthenium catalyst with high performance for acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4849. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12886-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hao S, et al. Dopants fixation of Ruthenium for boosting acidic oxygen evolution stability and activity. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5368. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19212-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao ZL, et al. Boosting oxygen evolution reaction using defect-rich ultra-thin ruthenium oxide nanosheets in acidic media. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020;13:5143–5151. doi: 10.1039/D0EE01960G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng Q, et al. Influence of surface oxygen vacancies and ruthenium valence state on the catalysis of pyrochlore oxides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:4520–4530. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b19352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodnik N, et al. New insights into corrosion of ruthenium and ruthenium oxide nanoparticles in acidic media. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015;119:10140–10147. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b01832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cherevko S, et al. Dissolution of noble metals during oxygen evolution in acidic media. ChemCatChem. 2014;6:2219–2223. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201402194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy C, et al. Trends in activity and dissolution on RuO2 under oxygen evolution conditions: particles versus well-defined extended surfaces. ACS Energy Lett. 2018;3:2045–2051. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasian O, et al. On the origin of the improved ruthenium stability in RuO2–IrO2 mixed oxides. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016;163:F3099. doi: 10.1149/2.0131611jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spori C, et al. The stability challenges of oxygen evolving catalysts: towards a common fundamental understanding and mitigation of catalyst degradation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:5994–6021. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z, et al. Predicting aqueous stability of solid with computed Pourbaix diagram using SCAN functional. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2020;6:160. doi: 10.1038/s41524-020-00430-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cherevko S, et al. Oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions on Ru, RuO2, Ir, and IrO2 thin film electrodes in acidic and alkaline electrolytes: a comparative study on activity and stability. Catal. Today. 2016;262:170–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2015.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao Y, et al. Engineering the electronic structure of single atom Ru sites via compressive strain boosts acidic water oxidation electrocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 2019;2:304–313. doi: 10.1038/s41929-019-0246-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen S, et al. Mn-doped RuO2 nanocrystals as highly active electrocatalysts for enhanced oxygen evolution in acidic media. ACS Catal. 2019;10:1152–1160. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b04922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Z, et al. Mg-Doping improves the performance of Ru-based electrocatalysts for the acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Commun. 2020;56:1749–1752. doi: 10.1039/C9CC09613B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, J. et al. Exceptionally active and stable RuO2 with interstitial carbon for water oxidation in acid. Chem10.1016/j.chempr.2022.02.003 (2022).

- 32.Laha S, et al. Ruthenium oxide nanosheets for enhanced oxygen evolution catalysis in acidic medium. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019;9:1803795. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201803795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim B-J, et al. Unraveling thermodynamics, stability, and oxygen evolution activity of strontium ruthenium perovskite oxide. ACS Catal. 2017;7:3245–3256. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.6b03171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arčon I, et al. X-ray absorption spectroscopy analysis of Ru in La2RuO5. X-Ray Spectrom. 2007;36:301–304. doi: 10.1002/xrs.946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He J, et al. Tuning electron correlations of RuO2 by co-doping of Mo and Ce for boosting electrocatalytic water oxidation in acidic media. Appl. Catal. B. 2021;298:120528. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.120528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Q, et al. Identifying the activation mechanism and boosting electrocatalytic activity of layered perovskite ruthenate. Small. 2020;16:1906380. doi: 10.1002/smll.201906380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wohlfahrt-Mehrens M, Heitbaum J. Oxygen evolution on Ru and RuO2 electrodes studied using isotope labelling and on-line mass spectrometry. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1987;237:251–260. doi: 10.1016/0022-0728(87)85237-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wen Y, et al. Stabilizing highly active Ru sites by suppressing lattice oxygen participation in acidic water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:6482–6490. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c00384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grimaud A, et al. Activation of surface oxygen sites on an iridium-based model catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Energy. 2016;2:16189. doi: 10.1038/nenergy.2016.189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grimaud A, et al. Activating lattice oxygen redox reactions in metal oxides to catalyse oxygen evolution. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:457–465. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang Z-F, et al. Chemical and structural origin of lattice oxygen oxidation in Co–Zn oxyhydroxide oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Nat. Energy. 2019;4:329–338. doi: 10.1038/s41560-019-0355-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song J, et al. A review on fundamentals for designing oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020;49:2196–2214. doi: 10.1039/C9CS00607A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi Z, et al. Fundamental understanding of the acidic oxygen evolution reaction: mechanism study and state-of-the-art catalysts. Nanoscale. 2020;12:13249–13275. doi: 10.1039/D0NR02410D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan Y, et al. Direct evidence of boosted oxygen evolution over perovskite by enhanced lattice oxygen participation. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2002. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15873-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miao X, et al. Quadruple perovskite ruthenate as a highly efficient catalyst for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3809. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11789-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Man IC, et al. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem. 2011;3:1159–1165. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201000397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hwang J, et al. Perovskites in catalysis and electrocatalysis. Science. 2017;358:751. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen G, et al. Regulating the spin state of Fe(III) by atomically anchoring on ultrathin titanium dioxide for efficient oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:2313–2317. doi: 10.1002/anie.201913080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buvat G, et al. OER performances of cationic substituted (100)-oriented IrO2 thin films: a joint experimental and theoretical study. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020;3:5229–5237. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.0c00069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yagi S, et al. Covalency-reinforced oxygen evolution reaction catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8249. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J, et al. Single-site Pt-doped RuO2 hollow nanospheres with interstitial C for high-performance acidic overall water splitting. Sci. Adv. 2022;8:9271. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abl9271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin H, et al. Safeguarding RuO2 phase against lattice oxygen oxidation during acidic water electrooxidation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021;15:1119–1130. doi: 10.1039/D1EE02636D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tian Y, et al. A Co-doped nanorod-like RuO2 electrocatalyst with abundant oxygen vacancies for acidic water oxidation. iScience. 2019;23:100756. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.100756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su J, et al. Assembling ultrasmall copper-doped ruthenium oxide nanocrystals into hollow porous polyhedra: highly robust electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution in acidic media. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1801351. doi: 10.1002/adma.201801351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li K, Xue D. Estimation of electronegativity values of elements in different valence states. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2006;110:11332–11337. doi: 10.1021/jp062886k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shannon RD. Revised effective ionic-radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalogenids. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1976;32:751–767. doi: 10.1107/S0567739476001551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rao RR, et al. Towards identifying the active sites on RuO2(110) in catalyzing oxygen evolution. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017;10:2626–2637. doi: 10.1039/C7EE02307C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shi Z, et al. Confined Ir single sites with triggered lattice oxygen redox: toward boosted and sustained water oxidation catalysis. Joule. 2021;5:2164–2176. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2021.05.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mefford JT, et al. Water electrolysis on La1-xSrxCoO3-d perovskite electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11053. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim J, et al. High-performance pyrochlore-type yttrium ruthenate electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:12076–12083. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b06808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lou Y, et al. Ultralow-temperature CO oxidation on an In2O3–Co3O4 catalyst: a strategy to tune CO adsorption strength and oxygen activation simultaneously. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:6835–6838. doi: 10.1039/C4CC00036F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zagalskaya A, Alexandrov V. Role of defects in the interplay between adsorbate evolving and lattice oxygen mechanisms of the oxygen evolution reaction in RuO2 and IrO2. ACS Catal. 2020;10:3650–3657. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b05544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klyukin K, et al. Role of dissolution intermediates in promoting oxygen evolution reaction at RuO2(110) surface. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:22151–22157. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b03418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Su, J. et al. Assembling ultrasmall copper-doped ruthenium oxide nanocrystals into hollow porous polyhedra: highly robust electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution in acidic media. Adv. Mater. 10.1002/adma.201801351 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Kim J-Y, et al. 4d Electronic structure analysis of ruthenium in the perovskite oxides by Ru K- and L-edge XAS. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2001;8:722–724. doi: 10.1107/S0909049500017787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stoerzinger KA, et al. Orientation-dependent oxygen evolution on RuO2 without lattice exchange. ACS Energy Lett. 2017;2:876–881. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harzandi AM, et al. Ruthenium core–shell engineering with nickel single atoms for selective oxygen evolution via nondestructive mechanism. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021;11:2003448. doi: 10.1002/aenm.202003448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scott SB, et al. The low overpotential regime of acidic water oxidation part II: trends in metal and oxygen stability numbers. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022;15:1988–2001. doi: 10.1039/D1EE03915F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu, Z. Y. et al. Non-iridium-based electrocatalyst for durable acidic oxygen evolution reaction in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Nat. Mater. 10.1038/s41563-022-01380-5 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Lazaridis T, et al. Capabilities and limitations of rotating disk electrodes versus membrane electrode assemblies in the investigation of electrocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 2022;5:363–373. doi: 10.1038/s41929-022-00776-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ehelebe K, et al. Limitations of aqueous model systems in the stability assessment of electrocatalysts for oxygen reactions in fuel cell and electrolyzers. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2021;29:100832. doi: 10.1016/j.coelec.2021.100832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Inaba M, et al. pH matters: the influence of the catalyst ink on the oxygen reduction activity determined in thin film rotating disk electrode measurements. J. Power Sources. 2017;353:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.03.140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Browne MP, et al. A mechanical, high surface area and solvent-free ‘powder-to-electrode’ fabrication method for screening OER catalysts. Electrochem. Commun. 2017;85:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2017.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.El-Sayed HA, et al. OER catalyst stability investigation using RDE technique: a stability measure or an artifact? J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019;8:F458–F464. doi: 10.1149/2.0301908jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Browne MP, Mills A. Determining the importance of the electrode support and fabrication method during the initial screening process of an active catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018;6:14162–14169. doi: 10.1039/C8TA02908C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Geiger S, et al. Catalyst stability benchmarking for the oxygen evolution reaction: the importance of backing electrode material and dissolution in accelerated aging studies. ChemSusChem. 2017;10:4140–4143. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201701523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geiger S, et al. The stability number as a metric for electrocatalyst stability benchmarking. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:508–515. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0085-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Choi S, et al. Pt dopant: controlling the Ir oxidation states toward efficient and durable oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020;30:2003935. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202003935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhu H, et al. High-entropy alloy stabilized active Ir for highly efficient acidic oxygen evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;431:133251. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.133251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu X, et al. Restructuring highly electron-deficient metal-metal oxides for boosting stability in acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:5676. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26025-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang F-F, et al. Iridium oxide modified with silver single atom for boosting oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. ACS Energy Lett. 2021;6:1588–1595. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.1c00283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shan J, et al. Short-range ordered iridium single atoms integrated into cobalt oxide spinel structure for highly efficient electrocatalytic water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:5201–5211. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c01525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.He J, et al. Regulating electron redistribution of intermetallic iridium oxide by incorporating Ru for efficient acidic water oxidation. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021;11:2102883. doi: 10.1002/aenm.202102883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu D, et al. Efficient overall water splitting in acid with anisotropic metal nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1145. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20956-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Su H, et al. In-situ spectroscopic observation of dynamic-coupling oxygen on atomically dispersed iridium electrocatalyst for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6118. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26416-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang Y, et al. Ce-doped IrO2 electrocatalysts with enhanced performance for water oxidation in acidic media. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:37006–37012. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c00389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dang Q, et al. Iridium metallene oxide for acidic oxygen evolution catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6007. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26336-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yin J, et al. Iridium single atoms coupling with oxygen vacancies boosts oxygen evolution reaction in acid media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:18378–18386. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c05050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li R, et al. IrW nanochannel support enabling ultrastable electrocatalytic oxygen evolution at 2 A cm-2 in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3540. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23907-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fan Z, et al. Extraordinary acidic oxygen evolution on new phase 3R-iridium oxide. Joule. 2021;5:3221–3234. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2021.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kötz R, et al. In-situ identification of RuO4 as the corrosion product during oxygen evolution on ruthenium in acid media. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1984;172:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0022-0728(84)80187-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fang W-C, et al. Effect of temperature annealing on capacitive and structural properties of hydrous ruthenium oxides. J. Power Sources. 2006;160:1506–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iliev, M. N. et al. Raman spectroscopy of Ca3Ru2O7: phonon line assignment and electron scattering. Phys. Rev. B71, 214305 (2005).

- 94.Kumar V, et al. Origin of intense blue-green emission in SrTiO3 thin films with implanted nitrogen ions: an investigation by synchrotron-based experimental techniques. Phys. Rev. B. 2021;103:024104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.103.024104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ye Y, et al. X-ray spectroscopies studies of the 3d transition metal oxides and applications of photocatalysis. MRS Commun. 2017;7:53–66. doi: 10.1557/mrc.2017.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pivovar, B. H2NEW: Hydrogen (H2) from Next-generation Electrolyzers of Water Overview. (US Department of Energy, 2021)

- 97.Kim H, et al. Dendritic gold-supported iridium/iridium oxide ultra-low loading electrodes for high-performance proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer. Appl. Catal. B. 2021;283:119596. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hegge F, et al. Efficient and stable low iridium loaded anodes for PEM water electrolysis made possible by nanofiber interlayers. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020;3:8276–8284. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.0c00735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Feng Q, et al. Oxygen vacancy engineering of yttrium ruthenate pyrochlores as an efficient oxygen catalyst for both proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers and rechargeable zinc-air batteries. Appl. Catal. B. 2020;260:118176. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Choe S, et al. Electrodeposited IrO2/Ti electrodes as durable and cost-effective anodes in high-temperature polymer-membrane-electrolyte water electrolyzers. Appl. Catal. B. 2018;226:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.12.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Böhm D, et al. Highly conductive titania supported iridium oxide nanoparticles with low overall iridium density as OER catalyst for large-scale PEM electrolysis. Appl. Mater. Today. 2021;24:101134. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2021.101134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pham CV, et al. IrO2 coated TiO2 core-shell microparticles advance performance of low loading proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers. Appl. Catal. B. 2020;269:118762. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.118762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Oh JH, et al. Activity and stability of Ir-based gas diffusion electrode for proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;420:127696. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.127696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Islam J, et al. Enhancing the activity and durability of iridium electrocatalyst supported on boron carbide by tuning the chemical state of iridium for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Power Sources. 2021;512:230506. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.230506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li G, et al. Iridium-Tin oxide solid-solution nanocatalysts with enhanced activity and stability for oxygen evolution. J. Power Sources. 2016;325:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jiang G, et al. An effective oxygen electrode based on Ir0.6Sn0.4O2 for PEM water electrolyzers. J. Energy Chem. 2019;39:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jechem.2019.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang L, et al. Highly active anode electrocatalysts derived from electrochemical leaching of Ru from metallic Ir0.7Ru0.3 for proton exchange membrane electrolyzers. Nano Energy. 2017;34:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.02.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Knoppel J, et al. On the limitations in assessing stability of oxygen evolution catalysts using aqueous model electrochemical cells. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2231. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22296-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996;6:15–50. doi: 10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]