Summary

The precise sequence control of polymer chain is an important research topic of polymer chemistry. Although some methods such as iterative synthesis and supramolecular polymerization have been developed to fabricate sequence-controllable polymer, it is still a great challenge to consecutively prepare multiple supramolecular polymers with different sequence structures. In this work, through the reasonable utilization of assembly motifs, we integrated multiple host-guest recognitions and metal coordination interactions to prepare different sequence-controlled supramolecular polymers by a multistep assembly strategy. This research provides inspiration for the design and preparation of supramolecular polymers with different sequence structures.

Subject areas: Polymer chemistry, Supramolecular chemistry, Molecular self-assembly

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Multiple supramolecular polymers were prepared by a multistep assembly strategy

-

•

Supramolecular polymers with different structures show different stimuli responsiveness

-

•

Different supramolecular polymer materials show different fluorescence emission

Polymer chemistry; Supramolecular chemistry; Molecular self-assembly

Introduction

The precise sequence control of polymer chain is a great challenge in polymer synthesis, which gives rise to structural and functional diversity.1,2,3,4,5 The sequence-controlled polymers are generally prepared by using iterative chemistry technology or sequential monomer addition method,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 such as the stepwise iterative synthesis for peptide on a solid-polymer support. However, iterative synthesis generally needs very high reaction yield and undergo an annoying purification process to remove error structures. Supramolecular polymerization opens up another way to develop sequence-controlled polymers.14,15,16 Various supramolecular polymerization methods have been developed to fabricate well-defined supramolecular polymers.17,18,19,20,21 Among these polymerization methodologies, self-assembly with single noncovalent interaction has been widely utilized to prepare supramolecular polymers. Compared to the self-assembly with one type of noncovalent interaction, orthogonal self-assembly incorporating two or multiple noncovalent interactions can endow the resulting supramolecular polymers with structural diversity and more specific properties.18 In a process of orthogonal self-assembly, each noncovalent interaction does not affect each other. Compared to the noninterference features of noncovalent interactions in the process of orthogonal self-assembly, competitive self-sorting assembly describes the fact that the existence of competitive noncovalent interactions and the process of self-sorting assembly.21 By means of the competitive self-sorting assembly, supramolecular polymers can easily achieve the sequence reorganization and architecture transformation, such as the structural conversion from hyperbranched supramolecular homopolymer to the hyperbranched supramolecular copolymer.21

Although various supramolecular polymers with different sequences and topological structures have been constructed under the direction of these assembly methods,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 consecutively preparing multiple sequence-controlled supramolecular polymers is still a great challenge. Alternatively, combining the merits of different polymerization methods and using a multistep assembly strategy may effectively solve the problem. Multistep assembly strategy can avoid the tedious synthesis and purification to some degree, and also endows the resulting polymers with the architecture and function diversities. To construct supramolecular polymers with different sequence structures by the multistep assembly, multiple different supramolecular forces with high specificities are required. Crown ethers and pillararenes-based host-guest recognition pairs have been applied to construct supramolecular assemblies.19 On the other hand, terpyridine (tpy) and its complementary ligand pairs have been also reported to form metal coordination structures with metal ions.27 Herein, we combine different polymerization methods and apply multiple host-guest recognitions and metal coordination interactions to develop different sequence-controlled supramolecular polymers by a multistep assembly strategy. These different supramolecular forces with high specificities include crown ethers and pillararenes-based host-guest pairs, terpyridine and its complementary ligand pairs.

We designed and synthesized three heterotopic monomers as follows (Scheme 1). The heterotritopic AB2, which contained two pillar[5]arene groups (P5) and an alkylammonium salt group (DAS); the heteroditopic CD consisted of a terpyridine (tpy) moiety and an alkyl chain guest (TAPN) moiety, and the heteroditopic EF beared a 6,6″-anthracyl-substituted tpy (tay) group and a crown ether (B21C) group. The AB2 could self-organize to form supramolecular hyperbranched homopolymer (SP1) by the host-guest interaction of P5-DAS. When adding the monomer CD to the solution of SP1, the SP1 could disassemble into pseudorotaxane PR1 by competitive host-guest interaction because of the stronger binding of P5-TAPN. After Zn(OTf)2 was added to the solution of pseudorotaxane PR1, the PR1 transformed into a new supramolecular hyperbranched copolymer SP2 based on the orthogonal noncovalent interaction of P5-TAPN and tpy-Zn2+-tpy. Moreover, as the tpy and tay formed complementary ligands pair that could undergo spontaneous heteroleptic complexation with zinc ion, when monomer EF was further added into the solution of SP2, the SP2 could further transform into a new supramolecular hyperbranched copolymer SP3 with new sequence structure through the P5-TAPN, B21C-DAS, and tpy-Zn2+-tay binding events based on the competitive self-sorting assembly.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of multistep self-assembly

The construction of the supramolecular homopolymer SP1, the disassembly of SP1, the construction of supramolecular copolymer SP2 based on orthogonal self-assembly, and the architecture transformation from supramolecular copolymer SP2 to SP3 based on competitive self-sorting assembly.

Results and discussion

NMR spectra and UV-Vis study

To study the multistep assembly process, we synthesized six model compounds 1–6 (Scheme 2). Firstly, a series of 1H NMR spectra containing two model compounds were recorded (Figures S1–S6, ESI†). When equimolar 1 and 6 were mixed in CDCl3 solution, the signals of protons C10, C11, C12, C13, C14 on 6 were shifted upfield (Figure S1, ESI†), suggesting that the alkylammonium salt of M6 entered into the cavity of pillararene in CDCl3 solution and formed the complex of P5-DAS.39 It’s worth noting that the proton peak shifts of 1 + 6 were not observed in CDCl3-CD3COCD3 (Figure S2, ESI†), indicating that the P5 could not bind the DAS or had extremely weak binding in the mixed solvent of CDCl3-CD3COCD3. Cation–π interaction was dependent on the type of solvent,40 the cation–π interaction should be severely weakened in the polar mixed solvent. The host–guest complexation of 1 and 2 was then studied. The 1H NMR spectrum showed that P5 could bind strongly TAPN in solution (Figure S3, ESI†).28 The host-guest recognition between 5 and 6 was also studied, the complex 1H NMR verified that the exchanging interaction between B21C and DAS was slow (Figure S4, ESI†).41 The metal coordination of tpy-Zn2+-tpy was clearly observed when compound 3 and Zn(OTf)2 were mixed in solution (Figure S5E and Figure S6, ESI†). In comparison with the metal coordination of tpy-Zn2+-tpy, the formation ratio for tay-Zn2+-tay was much slower, and an incomplete conversion (41%) was observed for 4 days (Figure S5A),27 presumably because of the increased bulkiness of the substituents at terpyridyl 6,6″-positions. However, when equimolar 3 + 4+Zn(OTf)2 was mixed in solution, the coordination protons of tpy-Zn2+-tpy rapidly disappeared and new chemical shifts of coordination protons were observed on the 1H NMR timescale, implying that the homoleptic coordination of tpy-Zn2+-tpy was disrupted and complementary tpy and tay ligands spontaneously self-assembled into heteroleptic tpy-Zn2+-tay structure with zinc ion (Figure S5C, ESI†).27 Furthermore, the heteroleptic complexation of tpy-Zn2+-tay was further verified by the ESI-MS peak at m/z = 547.1676 originated from [Zn34]2+ (Figure S7, ESI†), which provided direct evidence of the heteroleptic tpy-Zn2+-tay structure. These experimental results supported that the tpy-Zn2+-tay structure was more stable than that of tpy-Zn2+-tpy in CDCl3-CD3COCD3 (3:1, v/v).

Scheme 2.

The structures of the model molecules 1–6

The self-sorting binding among different model compounds were then investigated, a series of samples containing different noncovalent interactions were prepared and their 1H NMR spectra verified the self-sorting binding between P5-TAPN and tpy-Zn2+-tay (Figure S8, ESI†), between P5-TAPN and B21C-DAS (Figure S9, ESI†), between B21C-DAS and tpy-Zn2+-tay (Figure S10, ESI†). Finally, the 1H NMR spectrum of 1 + 2+3 + 4+5 + 6+Zn(OTf)2 revealed that the self-sorting binding indeed occurred in CDCl3-CD3COCD3 (Figure S11, ESI†). That is, P5 combined with TAPN, tpy bound tay in the presence of Zn2+, and B21C bound DAS in CDCl3–CD3COCD3 solution, respectively.

We then studied the multistep self-assembly of monomers. The self-assembly of AB2 in chloroform-d solution was first studied by 1H NMR. As shown in Figure 1C, the alkyl protons H1-5 of AB2 exhibited significant upfield shifts (−2.08, −1.54, −0.68, −0.39, 1.70 ppm) in CDCl3 solution, suggesting that the alkyl wheel of the DAS group on AB2 fully inserted into the hole of the P5 group on AB2. By means of the COSY NMR analysis (Figures S12–S14, ESI†), the 1H NMR of AB2 was identified. The 1H NMR of AB2 also revealed that the P5-DAS binding interaction was a fast-exchange interaction in solution. The 1H NMR spectra gradually broadened as the concentration of AB2 increased (Figure S15, ESI†), implying that the AB2 self-assembled into supramolecular homopolymer SP1 at high concentrations. Considering that the pillar[5]arene can encapsulate neutral guest molecule,42,43 adding monomer CD to the solution of AB2 may induce the disassembly of SP1. As showed in Figure 1D, when CD was added to the solution of AB2, the original complexed protons on AB2 disappeared (H1c-5c) and new complexed protons B1c-4c (2.55, −0.66, −0.79, −1.71 ppm) on CD were observed simultaneously on the NMR timescale, indicating that the supramolecular homopolymer SP1 was disassembled into [3]pseudorotaxane PR1. Considering terpyridyl can coordinate with metal ion, the PR1 may further transform into supramolecular hyperbranched copolymer SP2 by adding Zn(OTf)2. Owing to the poor solubility of Zn(OTf)2 in CDCl3, the Zn(OTf)2 was firstly dissolved in deuterated acetone and was then added into the solution of PR1. The protons B8-10 on CD shifted downfield and the proton B13 on CD shifted upfield, implying the occurrence of metal coordination between terpyridyl and zinc ion (Figure 1E).44,45 Meanwhile, the 1H NMR also revealed that the coordination of tpy-Zn2+-tpy did not interfere with the binding of P5-TAPN. The orthogonal noncovalent interactions between tpy-Zn2+-tpy and P5-TAPN and the broadened 1H NMR spectra at high concentrations (Figure S16, ESI†) supported that the PR1 transformed into a new supramolecular hyperbranched copolymer SP2. According to the previous report,27 in the presence of metal ion, tay can spontaneously form heteroleptic complex with tpy in organic solvent. Thus, the SP2 was expected to further transform into a new supramolecular copolymer SP3 when adding EF into the solution of SP2 through the competitive self-sorting assembly. As shown in Figure 1F, the original complexed protons (B9c, B10c) on CD disappeared, and new complexed protons (B9c, B10c, E16c) shifted upfield, verifying the dissociation of the tpy-Zn2+-tpy and the formation of new tpy-Zn2+-tay coordination structure.27 Meanwhile, the complexation of B21C-DAS was also observed (H1c, H2c, H3c, EOc), which manifested the occurrence of host-guest recognition between B21C and DAS.46,47 In addition, the 1H NMR also revealed that the metal coordination tpy-Zn2+-tay did not affect the host-guest interaction of P5-TAPN. Moreover, the 1H NMR obviously broadened at high concentration (Figure S17, ESI†). The above 1H NMR analysis and the concentration-dependent 1H NMR spectra supported that the SP2 transformed into another sequence-controlled SP3 when adding EF into the solution of SP2.

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, CDCl3, 15 mM, 298 K)

(A) EF, (B) CD, (C) AB2, (D) AB2+CD; 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, CDCl3-CD3COCD3 = 3:1, v/v, 15 mM, 298 K) of (E) AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, and (F) AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2. Proton signals of complexed monomers are designated as c.

2D NOESY NMR was also conducted to investigate the multistep assembly of monomers. For the AB2 system, the strong correlations among H1-5 and H17-19 on AB2 verified that the DAS group of AB2 entered the P5 cavity of AB2 (Figure 2A, ESI†). After adding the monomer CD and Zn(OTf)2 into the solution of AB2, the correlations among H1-5 and H17-19 disappeared and new correlations among B1-4 on CD and H17-19 on AB2 were observed (Figure 2B, ESI†), indicating that the DAS moiety of AB2 was squeezed out the cavity of P5 by TAPN of CD due to the stronger binding between P5 and TAPN. After further adding EF to the solution of AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, the correlations among B1-4 and H17-19 were still observed, and new correlations among H5, H7, H8 of AB2 and EO of EF were also found in the 2D NOESY spectrum (Figure 2C, ESI†), verifying the coexist of host-guest interactions P5-TAPN and B21C-DAS in solution.

Figure 2.

2D NOESY NMR spectra

(A) AB2 in CDCl3, (B) AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2 in CDCl3-CD3COCD3 (3/1, v/v), (C) AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 in CDCl3-CD3COCD3 (3/1, v/v, 400 MHz, 60 mM, 298K).

UV-Vis titrations were also performed to investigate the multistep assembly of monomers. The titrations were firstly performed through titrating Zn(OTf)2 into the solution of CD (Figure 3A), the UV-Vis titration curves exhibited an isosbestic point at 308 nm, implying that the free tpy gradually transformed into the coordination structure.44 The titration curve has a maximum absorbance at 343 nm when the molar ratio of Zn(OTf)2 versus CD was 1 : 2. The variation of the absorbance versus the concentration of Zn(OTf)2 was plotted (inset), which verified the formation of the tpy-Zn2+-tpy coordination structure in the solution. The titration curve of AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2 was similar to that of CD + Zn(OTf)2 (Figure 3B), indicating that the host-guest interaction P5-TAPN did not interfere with the metal coordination of tpy-Zn2+-tpy. Similarly, the titrations of CD + EF and AB2+CD + EF were also performed by adding Zn(OTf)2. As shown in Figure 3C, the titration curves of CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 revealed an isosbestic point at 313 nm and a maximum absorbance at 346 nm when the molar ratio of Zn(OTf)2: CD: EF is 1:1:1. The variation of the absorbance versus the concentration of Zn(OTf)2 was plotted (inset), which verified the generation of heteroleptic complex tpy-Zn2+-tay. As shown in Figure 3D, the titration plots of AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 were similar to those of CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2, and a titration endpoint was achieved when the molar ratio was 1:2:2:2 (AB2:CD: EF: Zn(OTf)2), indicating that the B21C-DAS and P5-TAPN host-guest recognitions didn’t affect the coordination of tpy-Zn2+-tay. The binding constants of tpy-Zn2+-tpy and tpy-Zn2+-tay were then calculated by job plot method of UV-Vis (Figures S18–S21, ESI†), and the data verified that the binding constant of tpy-Zn2+-tay was higher than that of tpy-Zn2+-tpy, in accordance with the mass spectra and 1H NMR analysis (Figures S5–S7, ESI†). The binding constants of host-guest interactions P5-DAS, P5-TAPN, B21C-DAS were also measured by reference methods (Figures S22–S25, ESI†).

Figure 3.

Changes in the UV-Vis absorption spectra

Stepwise adding Zn(OTf)2 (2 mM) to the solutions of (A) 0.015 mM CD, (B) 0.015 mM AB2+CD, (C) 0.015 mM CD + EF, and (D) 0.020 mM AB2+CD + EF (chloroform versus acetone=3:1, v/v, 298K).

DOSY NMR were then performed to further investigate the supramolecular polymerization of multistep assembly. For the AB2 system, when the concentration of AB2 gradually increased (2–110 mM), the measured weight average diffusion coefficient (D) ranged from 3.75 × 10−10 to 4.88 × 10−11 m2 s−1 (Figures 4 and S26), verified the concentration-dependent characteristic of supramolecular polymerization and the formation of supramolecular homopolymer SP1 at high concentration.48 When CD was added into the SP1 constructed by self-assembly of AB2 (AB2 = 110 mM), the D value increased dramatically from 4.88× 10−11 to 3.05× 10−10 m2 s−1 (Figures 4 and S27), implying that SP1 disassembled into low molecular weight PR1. When Zn(OTf)2 was subsequently added into the PR1, the D value reduced considerably from 3.05× 10−10 to 1.08× 10−11 m2 s−1, suggesting the formation of a new supramolecular copolymer SP2 (Figures 4 and S28). After EF was further added to the solution of SP2, the D value changed from 1.08× 10−11 to 1.65× 10−11 m2 s−1, supporting that the SP2 transformed into another supramolecular copolymer SP3. Both the D values gradually increased as the concentrations diluted (Figures 4 and S29), which further verified the reversibility of noncovalent interactions and concentration-dependence feature of supramolecular polymerization.49 It is worth noting that the D value for SP2 was slightly larger than that of SP3 at the same concentration of AB2 (110 mM). It can be reasonably explained as follows: The molecular weight and polymerization degree of supramolecular polymers depend on the binding constants of noncovalent bonding and monomers concentrations. The SP3 was constructed based on three types of noncovalent interactions, the minimum binding constant among P5-TAPN, tpy-Zn2+-tay, and B21C-DAS mainly determined the polymerization degree and molecular weight of SP3. Although the binding constant of tpy-Zn2+-tay on SP3 was larger than that of tpy-Zn2+-tpy on SP2, the binding constant of B21C-DAS on SP3 was smaller than those of P5-TAPN and tpy-Zn2+-tpy on SP2. Thus, it is reasonable that the molecular weight of SP3 was smaller than that of SP2, which corresponds to the experimental D values of SP2 and SP3.

Figure 4.

Average weight diffusion coefficients of AB2, AB2+CD, AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, and AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 versus the concentrations of AB2 at 298K

Study of viscosity, DLS, and SEM

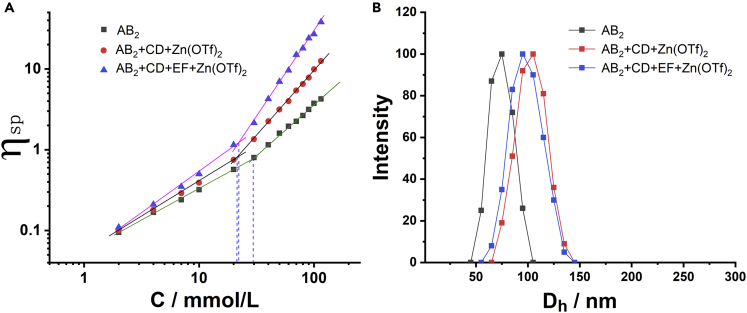

Viscosity measurements were also conducted to investigate the multistep supramolecular polymerization. The specific viscosity of the AB2, AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, and AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 against the concentration of AB2 (bilogarithmic plot) was plotted in Figure 5A. At the same concentrations, both the AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2 and AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 had higher specific viscosities than that of AB2 system, which could ascribe to the higher molecular weight of SP2 and SP3. In addition, both the critical polymerization concentrations of SP2 and SP3 (the intersection of two lines) had lower values than that of AB2, this result may derive from the lower binding constant of P5-DAS on AB2. At low concentrations, supramolecular oligomers were main species,50,51 and supramolecular oligomers gradually transformed into supramolecular polymers when the concentrations were above the critical polymerization concentrations in the AB2, AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, and AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 systems.

Figure 5.

Specific viscosities and hydrodynamic diameter distributions

(A) Specific viscosities of AB2, AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, and AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 against the concentrations of AB2 at 298K;

(B) the hydrodynamic diameter distributions of AB2, AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, and AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 in solutions (AB2 = 120 mM, 298 K).

The sizes of supramolecular polymers in solutions were then investigated by dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments (Figure 5B). The SP1 constructed by self-assembly of AB2 had a hydrodynamic diameter (Dh) of 73 nm in solution (120 mM). A higher Dh value of 105 nm was observed for the SP2 solution of AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2. The higher Dh of AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2 was reasonable because the binding constants of P5-TAPN and tpy-Zn2+-tpy were both larger than that of P5-DAS, the higher binding constants generally resulted in the larger sizes of supramolecular aggregates at same concentration. When EF was added to the solution of AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, the Dh value became 96 nm, the relatively smaller Dh value for AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 was speculated to derive from the smaller binding constant of B21C-DAS compared to those of P5-TAPN and tpy-Zn2+-tpy. The morphologies of SP1-SP3 were observed by SEM. As shown in Figures 6A, 6B, and 6C, widespread branched structures with ranging from tens of nanometers to hundreds of nanometers were observed in all representative SEM images of the SP1, SP2, and SP3 samples. To eliminate the possibility of samples crystallization, XRD experiments were performed. The XRD analysis indicated that the samples of SP1-SP3 are amorphous and eliminate the possibility of samples crystallization (Figure S30). Compared with the SEM image of SP1, the SEM images of SP2 and SP3 look more regular. The binding constant of noncovalent interactions may have an influence on the morphology of supramolecular polymers. The binding constant of P5-DAS on SP1 was smaller than those of SP2 and SP3, which may induce the smaller sizes of SP1 as observed in the SEM image. Moreover, a close inspection of the branched structures in SEM images showed that the larger branched structures contained the stacking of smaller branched structures. It was reasonable that smaller branches may superimpose on each other to form macro-sized branched aggregates when the samples changed from solutions to dry solids during the preparation of SEM samples, the cartoon representation of the formation of branched morphology was depicted in Figure 6D.

Figure 6.

Representative SEM images of the supramolecular polymers (The samples were prepared from 35 mM solutions)

(A–C)SP1, (b)SP2, (c)SP3.

(D) The graphical illustration of the formation of macro-sized branched structures.

Stimuli-responsiveness of supramolecular polymers

Finally, we investigated the stimuli-responsiveness of supramolecular polymers. The SP1 exhibited competitive guest responsiveness due to the stronger binding between TAPN and P5 (Figure 1D). Similarly, the SP2 also exhibited competitive guest responsiveness, when butanedinitrile was added into the solution of SP2, the SP2 disassembled into low molecular weight oligomers (Figure S31, ESI†) due to the stronger binding of P5-butanedinitrile. Besides the P5-TAPN binding could be manipulated, the metal coordination could also be adjusted, when compound 4 was added into the solution of SP2 (Figure S32, ESI†), the 1H NMR revealed the disassembly of SP2 as the tpy-Zn2+-tay binding was tighter than that of tpy-Zn2+-tpy. Compared to the SP2 system, the SP3 contained three types of noncovalent interactions, which may exhibit more stimuli-responsiveness. First, the butanedinitrile could also induce the disassembly of SP3 (Figure S33, ESI†). Second, it was found that the SP3 exhibited K+ responsiveness. When KPF6 was added to the SP3 solution, the 1H NMR obviously became sharper (Figure S34, ESI†), implying the disassembly of SP3.47 After another crown ether (B18C6) of smaller ring was added to the solution, the 1H NMR became complicated again as the B18C6 could capture K+ and the host-guest binding of B21C-DAS was recovered, which induced the reformation of SP3.

Besides the P5-TAPN, B21C-DAS host-guest interactions could be adjusted, the metal coordination tpy-Zn2+-tay may also be manipulated by adding OH− anion. As shown in Figure 7A, the solution of AB2+CD + EF emitted strong blue fluorescence because of the anthracene chromophore on free tay group of EF. However, when Zn(OTf)2 was added to the above solution, the SP3 constructed by AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 only gave off weak fluorescence owing to the formation of tpy-Zn2+-tay on the skeleton of SP3. When an organic base tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (TBAOH) was added into the solution of SP3, the fluorescence intensity of the solution almost recovered. The recovery of fluorescence emission could be explained as follows: When TBAOH was added into the solution, hydroxyl ion could form zinc hydroxide with zinc ion, which caused the destruction of tpy-Zn2+-tay coordination and the disassembly of SP3. The destruction of tpy-Zn2+-tay drove the coordinative tay into free tay, and the free tay group could emit strong blue fluorescence under the UV irradiation. The fluorescent spectra supported the inference (Figure 7C). Interesting, an opposite experimental phenomenon was observed in the SP2 system (Figure 7B), the solution of AB2+CD showed weak fluorescence emission. When Zn2+ ion was added to the AB2+CD solution, the AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2 self-assembled into SP2 and a significant fluorescence enhancement was observed because of the formation of tpy-Zn2+-tpy coordination structure on the SP2 skeleton. However, When TBAOH was subsequently added into the solution of AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, the fluorescence emission significantly decreased owing to the dissociation of tpy-Zn2+-tpy coordination on the SP2 skeleton and the formation of zinc hydroxide. Furthermore, The SP2 and SP3-based films were prepared through spreading several drops of SP2 and SP3-containing solutions on glasses and then drying them in air. Similar fluorescence enhancement or quenching phenomena were observed after TBAOH were added to the above films (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

Photographs and Fluorescence emission spectra

(A and B) Photographs of AB2+CD + EF, AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2, AB2+CD + EF + Zn(OTf)2 + TBAOH, AB2+CD, AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2, and AB2+CD + Zn(OTf)2 + TBAOH in CDCl3−CD3COCD3 taken under 365 nm UV lamp irradiation.

(C) Fluorescence emission spectra of the above solutions at 0.04 mM concentrations.

(D) Photographs of the SP2 and SP3-based films and the TBAOH responsiveness of the films.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we designed and synthesized three different monomers AB2, CD, and EF. The AB2 could self-assemble into supramolecular homopolymer SP1 based on P5-DAS host-guest interaction. When monomer CD and Zn(OTf)2 were added into the solution of SP1 solution, the SP1 was disassembled by competitive noncovalent interaction and simultaneously transformed into a new supramolecular copolymer SP2 based on the orthogonal noncovalent interaction of P5-TAPN and tpy-Zn2+-tpy. When monomer EF was further added into the solution of SP2, the SP2 further transformed into a new supramolecular copolymer SP3 with new sequence structure based on competitive self-sorting assembly. The multistep supramolecular assemblies were studied and verified by various techniques. The resulting three supramolecular polymers SP1, SP2, and SP3 showed different stimuli-responsiveness according to the types of noncovalent bonds. Various host–guest motifs and metal ligand pairs have been previously synthesized and offer choices to construct controllable supramolecular structures. Therefore, our assembly strategy may be adopted to construct tailored polymer sequences with structural variations and greater complexity by the combination of different noncovalent interactions. This research provides inspiration and possibilities for the design of supramolecular polymer with different advanced functions and sequence structures such as stimuli-responsiveness and self-repairing.

Limitations of the study

This research provides inspiration for the design and preparation of supramolecular polymers with different sequence structures. However, the mechanical strength of supramolecular polymer materials is limited because of the dynamic reversibility of noncovalent reactions. Moreover, the synthesis of multiple monomers makes the supramolecular materials costly. Hence, functional supramolecular materials prepared by easier and cheaper methods should be exploited in future research.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| 2-Acetyl-6-bromopyridine | Innochem | CAS:49669-13-8 |

| NaOH | Innochem | CAS:1310-73-2 |

| P-Anisaldehyde | Innochem | CAS:123-11-5 |

| NH3·H2O | Greagent | CAS:1336-21-6 |

| DCM | Greagent | CAS:75-09-2 |

| Ethanol | Adamas | CAS:64-17-5 |

| 9-Anthraceneboronic acid | Innochem | CAS:100622-34-2 |

| Tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0) | Innochem | CAS:14221-01-3 |

| Toluene | Greagent | CAS:108-88-3 |

| Tert- butyl alcohol | Innochem | CAS:75-65-0 |

| Na2CO3 | Accela | CAS:497-19-8 |

| CH3OH | Adamas | CAS:67-56-1 |

| Hydrogen Bromide | Greagent | CAS:10035-10-6 |

| Acetic Acid | Innochem | CAS:64-19-7 |

| Na2SO4 | Greagent | CAS:7757-82-6 |

| Hexaethylene glycol | Innochem | CAS:2615-15-8 |

| p-Toluenesulfonyl chloride | Innochem | CAS:98-59-9 |

| Acetonitrile | Greagent | CAS:75-05-8 |

| Triethylamine | Innochem | CAS:121-44-8 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | Greagent | CAS:109-99-9 |

| Petroleum Ether | Greagent | CAS:8032-32-4 |

| Ethyl Acetate | Greagent | CAS:141-78-6 |

| Methyl 3,4-dihydroxybenzoate | Local | CAS:2150-43-8 |

| K2CO3 | Greagent | CAS:584-08-7 |

| Potassium fluoroborate | Innochem | CAS:14075-53-7 |

| Tetrabutylammonium fluoride solution | Innochem | CAS:429-41-4 |

| 1,6-Dibromohexane | Innochem | CAS:629-03-8 |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide | Greagent | CAS:68-12-2 |

| Cesium Carbonate | Greagent | CAS:534-17-8 |

| Paraformaldehyde | Innochem | CAS:30525-89-4 |

| 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene | Innochem | CAS:150-78-7 |

| Boron trifluoride diethyl etherate | Innochem | CAS:109-63-7 |

| Boron tribromide | Innochem | CAS:10294-33-4 |

| Propargyl bromide | Innochem | CAS:106-96-7 |

| Phloroglucinol | Innochem | CAS:108-73-6 |

| 1,2-Dibromoethane | Innochem | CAS:106-93-4 |

| CuSO4·5H2O | Innochem | CAS:7758-99-8 |

| Sodium ascorbate | Innochem | CAS:134-03-2 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | Innochem | CAS:123-08-0 |

| Amylamine | Innochem | CAS:110-58-7 |

| Hydrochloric Acid | Adamas | CAS:7647-01-0 |

| Sodium borohydride | Innochem | CAS:16940-66-2 |

| Silica gel | Greagent | CAS:63231-67-4 |

| CDCl3 | Innochem | CAS:865-49-6 |

| Acetone-d6 | Innochem | CAS:666-52-4 |

| Zinc trifluoromethanesulfonate | Innochem | CAS:54010-75-2 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Origin 8 | Origin Lab | https://www.originlab.com/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Hui Li (lh@jxust.edu.cn).

Material availability

Materials are available up on request.

Experimental model and subject details

This study did not use experimental models typical in life sciences.

Method details

General information

All starting materials were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. Compounds M1,21 M4,52 and monomer CD45 were synthesized using reported methodologies as described ahead. 200-300 mesh silica gel was adopted as column chromatography. 1H NMR, 13C NMR, 2D COSY, 2D NOESY and DOSY experiments were performed on a Bruker 400 MHz device or a Bruker 600 MHz device. Viscosity experiments were carried out using a ubbelohde viscometer (0.5 mm inner diameter) at 293 K. High-resolution MALDI-TOF mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker autoflex III mass spectrometer. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments were performed on a Brookhaven BI-9000AT system (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, USA), using a 200-mW polarized laser source (λ = 630 nm) and the solutions of the samples were filtered with a PTFE syringe filter before measurement. The UV−Vis experiments were performed on a Cary 60 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The fluorescence spectra were performed on a Hitachi F-7000 spectrofluorometer. The XRD experiments were carried out on an Empyream instrument. The SEM samples were prepared at 35mM concentrations by casting droplet solutions of the samples on glass plates and the samples were dried for 12 hours. Gold coating were sputtered onto the samples and the samples were then observed on a JEOL 6390LV scanning electron microscopy instrument.

Synthesis of monomer AB2

A mixture of M1 (2.0g, 1.11mmol) and M2 (0.43g, 1.11mmol) in a solution of tetrahydrofuran and water (5:1, 100 mL) in the presence of CuSO4⋅5H2O (55.0mg, 0.22 mmol) with sodium ascorbate (105.0 mg, 0.54 mmol) was stirred at 60 °C for 12h. After the reaction mixture was cooled to ambient temperature, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the resulting residue was subjected to column chromatography (CH2Cl2/CH3OH= 40:1), to give AB2 (0.91g, 46%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3COCD3, 298 K): ppm = 0.36 (m, 6H), 1.34(m, 2H), 3.08 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 3.43 (s, 6H), 3.74 (m, 68H), 4.44 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 5.02 (s, 4H), 5.23 (s, 2H), 5.68(s, 2H), 5.72 (s, 4H), 6.72(s, 2H), 6.93(m, 16H), 7.00(s, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.37(s, 2H), 7.50(s, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 8.03 (s, 1H), 8.22(s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 159.33, 150.90, 150.58, 150.51, 149.26, 137.57, 131.71, 128.60, 128.34, 128.26, 128.18, 123.38, 115.47, 113.83, 113.75, 113.62, 113.45, 113.40, 113.34, 62.09, 61.50, 55.01, 54.97, 52.99, 52.84, 51.11, 47.92, 27.51, 25.44, 21.01, 13.14. MALDI-TOF-MS (C118H131F6N10O21P): m/z calcd for [M – PF6-]+= 2024.9518, found =2024.9567, error 2.4 ppm. See Scheme S1, Figures S35–S37.

Synthesis of monomer AE

A solution of M3 (2.00 g, 1.48 mmol), M4 (0.83 g, 1.48 mmol), Cs2CO3 (1.45 g, 4.5mmol) in DMF (50 mL) was stirred for 14 hat 82 °C. After the reaction mixture was cooled to ambient temperature, the organic solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was partitioned between dichloromethane (50 mL) and water (50 mL). The aqueous layer was further washed with dichloromethane (2 × 50 mL). The organic phases were combined and dried by anhydrous Na2SO4. After the solvent was removed, the resulting residue was subjected to column chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol=70:1), to give AE (1.28g, 74%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) 8.97 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.69 (s, 2H), 8.61 (s, 2H), 8.19 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 8.10 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H), 7.56–7.65 (m, 5H), 7.49–7.53 (m, 5H), 7.35–7.42 (m, 4H), 6.84 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.27 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 4.16–4.21 (m, 4H), 3.89–3.98(m, 4H), 3.87(t, J = 4.0 Hz, 2H), 3.77–3.83(m, 4H), 3.71–3.76(m, 4H), 3.63–3.70(m, 8H), 1.72–1.79 (m, 4H), 1.43–1.47(m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 166.4, 159.8, 157.6, 156.8, 155.9, 152.8, 148.3, 137.1, 135.6, 131.5, 130.2, 128.5, 127.5, 127.0, 126.4, 125.9, 125.2, 123.9, 120.0, 118.9, 114.6, 112.3, 71.3, 71.2, 71.1, 70.9, 70.7, 69.7, 69.5, 69.0, 67.7, 64.8, 29.0, 28,7, 25.8, 25.7. MALDI-TOF-MS (C74H69N3O10): m/z calcd for [M+H]+ =1160.5056, found =1160.5066, error 1.0 ppm. See Scheme S2, Figures S38–S40.

The study of binding constants

Tpy-Zn2+-tay binding constant

Method A: Job plot of UV-Vis titration

To determine the association constant of tpy-Zn2+-tay, the UV-Vis experiment (Job plot method) was conducted according to the literature method.53 Model compounds 3 and 4 were chosen as the ligands. A series of samples were prepared and the total molar concentration of ligands () and zinc ion was maintained at 2×10-5M in each sample and only the ratios of zinc ion to ligands were altered. The job plot was conducted by varying the mole fractions of the ligands () and zinc ion. The concentration: + [Zn(OTf)2] = 2×10-5M. The absorbance intensity at 412 nm was plotted (Figure S18) against the mole fraction of Zn(OTf)2. The Job plot (Figure S18) indicates a 1:1:1 binding among Zn2+, 3 and 4.

Furthermore, the data of job plot were divided into two groups around Xm= 0.5. When Xm ≤ 0.5, the fitting equation is A = 0.1766Xm + 0.01223. When Xm≥ 0.5, the fitting equation is A = -0.2015Xm + 0.20071. The intersection point of the two fitting curves is taken (Xm=0.5075, A=0.1031), and the experimental value is Xm=0.5000, A'= 0.0991. The dissociation degree of complex [Zn34](OTf)2 was calculated from Equation 1. According to the formula, the dissociation degree(α) of complex [Zn34](OTf)2 was calculated to be 0.038.

| (Equation 1) |

The binding constant K was then calculated to be 6.68×107 M−1 based on Equation 2.

| (Equation 2) |

Where C is the total concentration of the complex [Zn34](OTf)2 and α is the degree of dissociation of complex [Zn34](OTf)2 when Xm value is 0.5, with the hypothesis that the ligands and zinc ion only form the complex [Zn34](OTf)2. The C is 1×10-5 M and the α is 0.038 when Xm is 0.5.

Method B:Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

The binding constant tpy-Zn2+-tay was also determined in CDCl3-CD3COCD3 (3:1, v/v) by using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). A representative calorimetric titration curve was shown in Figure S19. Based on the obtained ITC data, the association constant (K) of tpy-Zn2+-tay was estimated to be (5.85±3.03)×107 M−1.

The binding constant of tpy-Zn2+-tay measured by job plot method is consistent with the measured value of isothermal titration calorimetry.

Tpy-Zn2+-tpy binding constant

Method A: Job plot of UV-vis titration

To determine the association constant of tpy-Zn2+-tpy, the UV-Vis experiment (Job plot method) was conducted according to the literature method.53 Model compounds 3 was chosen as the ligand. A series of samples were prepared and the total molar concentration of ligand 3 and zinc ion was maintained at 2×10-5M in each sample and only the ratios of zinc ion to ligand were altered. The job plot was conducted by varying the mole fractions of the ligand 3 and zinc ion. The concentration: 3+ [Zn(OTf)2] = 2×10-5M. The absorbance intensity at 348 nm was plotted (Figure S20) against the mole fraction of Zn(OTf)2. The Job plot indicates a 1:2 binding ratio between Zn2+ and 3.

Furthermore, the data of job plot were divided into two groups around Xm= 0.5. When Xm ≤ 0.5, the fitting equation is A = 1.57516Xm + 0.02735. When Xm≥ 0.5, the fitting equation is A = -0.81109Xm + 0.819. The intersection point of the two fitting curves is taken (Xm=0.331, A=0.587), and the experimental value is Xm=0.333, A'=0.524. The dissociation degree of complex [Zn32](OTf)2 was calculated from Equation 3. According to the formula, the dissociation degree(α) of complex [Zn32](OTf)2 was calculated to be 0.107.

| (Equation 3) |

The binding constant K was calculated to be 7.76×106 M−1 based on Equation 4.

| (Equation 4) |

Method B: Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

The binding constant tpy-Zn2+-tpy was also determined in CDCl3-CD3COCD3 (3:1, v/v) by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) method. A representative calorimetric titration curve was shown in Figure S21. Based on the obtained ITC data, the association constant (K) of tpy-Zn2+-tpy was estimated to be (1.00±0.32)×107 M−1.

P5-DAS binding constant

To investigate the association constant of pillar[5]arene/dialkylammonium salt (P5-DAS) between pillar[5]arene moiety of AB2 and dialkylammonium salt moiety of AB2 in CDCl3, 1H NMR titrations were performed with a constant concentration of model compound 6 (2.00 mM) and varying the concentrations of model compound 1 in the range of 0.25–6.0 mM. By a non-linear curve-fitting method,39 the association constant (Ka) of P5-DAS was estimated to be (432 ±7) M−1 (Figures S22 and S23).

The non-linear curve-fittings were based on the equation:

| (Equation 5) |

Where Δδ is the chemical shift change of C14 on model compound 6 at [H]0, Δδ∞ is the chemical shift change of C14 when the compound 6 is completely complexed, [G]0 is the fixed initial concentration of the guest molecule 6, and [H]0 is the varying concentrations of host molecule 1.

P5-TAPN binding constant

We used model compound 1 and 2 to determine the binding constant Ka of the P5-TAPN in CDCl3-CD3COCD3 (3:1, v/v, 298K) according to the reported method.42 Because P5-TAPN was a slow exchange interaction, the Ka could be calculated from integrations of complexed and uncomplexed peaks in 1H NMR spectrum. The experiment was performed at 2.00 mM CDCl3-CD3COCD3 solution. Using the reference method, Ka value was calculated as below:[(3.78/4.78) × 2 × 10−3]/[(1–3.78/4.78) × 2 × 10−3]2 = 9.03×103 M−1 (Figure S24).

B21C-DAS binding constant

The B21C-DAS host-guest interaction is a slow exchanging interaction. We use model compound 5 and 6 to determine the binding constant Ka of the B21C-DAS in CDCl3-CD3COCD3 according to the reported method.52 Because B21C-DAS is a slow exchange interaction, the Ka could be calculated from integrations of complexed and uncomplexed peaks in 1H NMR spectrum. The experiment was performed at 5.00 mM CDCl3-CD3COCD3 solution. Using the reference method, Ka value was calculated as below:[(1.48/2.48) × 5 × 10−3]/[(1–1.48/2.48) × 5 × 10−3]2 = 733 M−1 (Figure S25).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22161020, 22022107, 21801100), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20212BAB203014), the Program of Qingjiang Excellent Young Talents, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, and Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (2020JC-20).

Author contributions

H.L.: Writing – Review and editing, Funding acquisition. S.R.: Synthesis of monomers. Y.Y.: Assembly. F.X.: Data curation. Z.H.: Formal analysis. X.H.: Investigation. Z.Z.: Data analysis. S.L.: Methodology. Z.Z.: Data analysis. W.T.: Writing – Review and editing.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 23, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106023.

Contributor Information

Hui Li, Email: lh@jxust.edu.cn.

Wei Tian, Email: happytw_3000@nwpu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

Data reported in this article will be shared by the lead contact on request.

-

•

There is no dataset or code associated with this work.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyse the data reported in this study is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Barnes J.C., Ehrlich D.J.C., Gao A.X., Leibfarth F.A., Jiang Y., Zhou E., Jamison T.F., Johnson J.A. Iterative exponential growth of stereo-and sequence-controlled polymers. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:810–815. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.620017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svec F., Fréchet J.M. New designs of macroporous polymers and supports: from separation to biocatalysis. Science. 1996;273:205–211. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouchi M., Badi N., Lutz J.F., Sawamoto M. Single-chain technology using discrete synthetic macromolecules. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:917–924. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lutz J.F., Ouchi M., Liu D.R., Sawamoto M. Sequence-controlled polymers. Science. 2013;341 doi: 10.1126/science.1238149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong R., Liu R., Gaffney P.R.J., Schaepertoens M., Marchetti P., Williams C.M., Chen R., Livingston A.G. Sequence-defined multifunctional polyethers via liquid-phase synthesis with molecular sieving. Nat. Chem. 2019;11:136–145. doi: 10.1038/s41557-019-0212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelis N.G., Anastasaki A., Nurumbetov G., Truong N.P., Nikolaou V., Shegiwal A., Whittaker M.R., Davis T.P., Haddleton D.M. Sequence-controlled methacrylic multiblock copolymers via sulfur-free RAFT emulsion polymerization. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porel M., Alabi C.A. Sequence-defined polymers via orthogonal allyl acrylamide building blocks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13162–13165. doi: 10.1021/ja507262t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merrifield B. Solid phase synthesis. Science. 1986;232:341–347. doi: 10.1126/science.3961484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plante O.J., Palmacci E.R., Seeberger P.H. Automated solid-phase synthesis of oligosaccharides. Science. 2001;291:1523–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.1057324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C., Wunderlich K., Mukherji D., Koynov K., Heck A.J., Raabe M., Barz M., Fytas G., Kremer K., Ng D.Y.W., Weil T. Precision anisotropic brush polymers by sequence controlled chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:1332–1340. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b10491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martens S., Van den Begin J., Madder A., Du Prez F.E., Espeel P. Automated synthesis of monodisperse oligomers, featuring sequence control and tailored functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:14182–14185. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy R.K., Meszynska A., Laure C., Charles L., Verchin C., Lutz J.F. Design and synthesis of digitally encoded polymers that can be decoded and erased. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7237. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badi N., Lutz J.F. Sequence control in polymer synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3383–3390. doi: 10.1039/b806413j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirao T., Kudo H., Amimoto T., Haino T. Sequence-controlled supramolecular terpolymerization directed by specific molecular recognitions. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:634. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00683-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi X., Zhang X., Ni X.L., Zhang H., Wei P., Liu J., Xing H., Peng H.Q., Lam J.W.Y., Zhang P., et al. Supramolecular polymerization with dynamic self-sorting sequence control. Macromolecules. 2019;52:8814–8825. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar A., Sasmal R., Empereur-Mot C., Bochicchio D., Kompella S.V.K., Sharma K., Dhiman S., Sundaram B., Agasti S.S., Pavan G.M., George S.J. Self-sorted, random, and block supramolecular copolymers via sequence controlled, multicomponent self-assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:7606–7617. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c01822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aida T., Meijer E.W., Stupp S.I. Functional supramolecular polymers. Science. 2012;335:813–817. doi: 10.1126/science.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li S.L., Xiao T., Lin C., Wang L. Advanced supramolecular polymers constructed by orthogonal self-assembly. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:5950–5968. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35099h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei P., Yan X., Huang F. Supramolecular polymers constructed by orthogonal self-assembly based on host–guest and metal–ligand interactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:815–832. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00327f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbero H., Thompson N.A., Masson E. "Dual layer" self-sorting with cucurbiturils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:867–873. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b09751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H., Fan X., Min X., Qian Y., Tian W. Controlled supramolecular architecture transformation from homopolymer to copolymer through competitive self-sorting method. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2017;38 doi: 10.1002/marc.201600631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirao T., Iwabe Y., Fujii N., Haino T. Helically organized fullerene array in a supramolecular polymer main chain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:4339–4345. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c13326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L., Cheng L., Li G., Liu K., Zhang Z., Li P., Dong S., Yu W., Huang F., Yan X. A self-cross-linking supramolecular polymer network enabled by crown-ether-based molecular recognition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:2051–2058. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu C., Zhang M., Tang D., Yan X., Zhang Z., Zhou Z., Song B., Wang H., Li X., Yin S., et al. A fluorescent metallacage-core supramolecular polymer gel formed by orthogonal metal coordination and host–guest interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:7674–7680. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b03781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X.H., Song N., Hou W., Wang C.Y., Wang Y., Tang J., Yang Y.W. Supramolecular polymer systems: efficient aggregation-induced emission manipulated by polymer host materials. Adv. Mater. 2019;31 doi: 10.1002/adma.201903962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang S., Wang Y., Chen Z., Lin Y., Weng L., Han K., Li J., Jia X., Li C. The marriage of endo-cavity and exo-wall complexation provides a facile strategy for supramolecular polymerization. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:3434–3437. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08820d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Y.J., Tu T.H., Su M.K., Yang C.W., Kong K.V., Chan Y.T. Facile construction of metallo-supramolecular poly(3-hexylthiophene)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) diblock copolymers via complementary coordination and their self-assembled nanostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:4218–4224. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H., Duan Z., Yang Y., Xu F., Chen M., Liang T., Bai Y., Li R. Regulable aggregation-induced emission supramolecular polymer and gel based on self-sorting assembly. Macromolecules. 2020;53:4255–4263. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.0c00519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu L., Shen X., Zhou Z., He T., Zhang J., Qiu H., Saha M.L., Yin S., Stang P.J., Stang P.J. Metallacycle-cored supramolecular polymers: fluorescence tuning by variation of substituents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:16920–16924. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b10842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin B., Zhang S., Huang Z., Xu J.F., Zhang X. Supramolecular interfacial polymerization of miscible monomers: fabricating supramolecular polymers with tailor-made structures. Macromolecules. 2018;51:1620–1625. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b00289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z.Y., Zhang Y., Zhang C.W., Chen L.J., Wang C., Tan H., Yu Y., Li X., Yang H.B. Cross-linked supramolecular polymer gels constructed from discrete multi-pillar[5]arene metallacycles and their multiple stimuli-responsive behavior. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:8577–8589. doi: 10.1021/ja413047r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng Y., Philp D. A molecular replication process drives supramolecular polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:17029–17039. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c06404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin B., Zhang S., Song Q., Huang Z., Xu J.F., Zhang X. Supramolecular interfacial polymerization: a controllable method of fabricating supramolecular polymeric materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56:7639–7643. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y., Zhang H.Y., Zhang Z.Y., Liu Y. Tunable luminescent lanthanide supramolecular assembly based on photoreaction of anthracene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:7168–7171. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groombridge A.S., Palma A., Parker R.M., Abell C., Scherman O.A. Aqueous interfacial gels assembled from small molecule supramolecular polymers. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:1350–1355. doi: 10.1039/c6sc04103e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu R., Yao J., Fu X., Zhou W., Qu D.H. A hyperbranched supramolecular polymer constructed by orthogonal triple hydrogen bonding and host–guest interactions. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:5429–5431. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08533g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mou Q., Ma Y., Jin X., Yan D., Zhu X. Host–guest binding motifs based on hyperbranched polymers. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:11728–11743. doi: 10.1039/c6cc03643k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia W., Ni M., Yao C., Wang X., Chen D., Lin C., Hu X.Y., Wang L. Responsive gel-like supramolecular network based on pillar[6]arene–ferrocenium recognition motifs in polymeric matrix. Macromolecules. 2015;48:4403–4409. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han C., Yu G., Zheng B., Huang F. Complexation between pillar[5]arenes and a secondary ammonium salt. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1712–1715. doi: 10.1021/ol300284c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogoshi T., Demachi K., Kitajima K., Yamagishi T.A. Monofunctionalized pillar[5]arenes: synthesis and supramolecular structure. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:7164–7166. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12333e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang C., Li S., Zhang J., Zhu K., Li N., Huang F. Benzo-21-Crown-7/Secondary dialkylammonium salt [2]Pseudorotaxane- and [2]Rotaxane-Type threaded structures. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5553–5556. doi: 10.1021/ol702510c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C., Han K., Li J., Zhang Y., Chen W., Yu Y., et al. Supramolecular polymers based on efficient pillar[5]arene-neutral guest motifs. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:11892–11897. doi: 10.1002/chem.201301022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Z., Luo Y., Chen J., Dong S., Yu Y., Ma Z., Huang F. formation of linear supramolecular polymers that is driven by C-H⋅⋅⋅π interactions in solution and in the solid state. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50:1397–1401. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding Y., Wang P., Tian Y.K., Tian Y.J., Wang F. Formation of stimuli-responsive supramolecular polymeric assemblies via orthogonal metal–ligand and host–guest interactions. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:5951–5953. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42511h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li H., Chen W., Xu F., Fan X., Liang T., Qi X., Tian W. A color-tunable fluorescent supramolecular hyperbranched polymer constructed by pillar[5]arene-based host–guest recognition and metal ion coordination interaction. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018;39 doi: 10.1002/marc.201800053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang C., Li S., Zhang J., Zhu K., Li N., Huang F. Benzo-21-Crown-7/Secondary dialkylammonium salt [2]Pseudorotaxane- and [2]Rotaxane-Type threaded structures. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5553–5556. doi: 10.1021/ol702510c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng B., Zhang M., Dong S., Liu J., Huang F. A benzo-21-crown-7/secondary ammonium salt [c2]Daisy chain. Org. Lett. 2012;14:306–309. doi: 10.1021/ol203062w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong S., Luo Y., Yan X., Zheng B., Ding X., Yu Y., Ma Z., Zhao Q., Huang F. A dual-responsive supramolecular polymer gel formed by crown ether based molecular recognition. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;123:1945–1949. doi: 10.1002/ange.201006999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan X., Wang F., Zheng B., Huang F. Stimuli-responsive supramolecular polymeric materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:6042–6065. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35091b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao T., Feng X., Wang Q., Lin C., Wang L., Pan Y. Switchable supramolecular polymers from the orthogonal self-assembly of quadruple hydrogen bonding and benzo-21-crown-7–secondary ammonium salt recognition. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:8329–8331. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44525a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang F., Han C., He C., Zhou Q., Zhang J., Wang C., Li N., Huang F. Self-sorting organization of two heteroditopic monomers to supramolecular alternating copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11254–11255. doi: 10.1021/ja8035465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang Y., Li H., Chen J., Xu F., Duan Z., Liang T., Liu Y., Tian W. Controllable supramolecular assembly and architecture transformation by the combination of orthogonal self-assembly and competitive self-sorting assembly. Polym. Chem. 2019;10:6535–6539. doi: 10.1039/c9py01495k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Likussar W., Boltz D.F. Theory of continuous variations plots and a new method for spectrophotometric determination of extraction and formation constants. Anal. Chem. 1971;43:1265–1272. doi: 10.1021/ac60304a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

Data reported in this article will be shared by the lead contact on request.

-

•

There is no dataset or code associated with this work.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyse the data reported in this study is available from the lead contact upon request.