Abstract

Mosquitoes are a formidable reservoir of viruses and important vectors of zoonotic pathogens. Blood-fed mosquitoes have been utilized to determine host infection status, overcoming the difficulties associated with sampling from human and animal populations. Comprehensive surveillance of potential pathogens at the interface of humans, animals, and the environment is currently an accredited method to provide an early warning of emerging or re-emerging infectious diseases and to proactively respond to them. Herein we performed comprehensive sampling of mosquitoes from seven habitats (residential areas, hospital, airplane, harbor, zoo, domestic sheds, and forest park) across five cities in Guangdong Province, China. Our aim was to characterize the viral communities and blood feeding patterns at the human-animal-environment interface and analyze the potential risk of cross-species transmission using meta-transcriptomic sequencing. 1898 female adult mosquitoes were collected, including 1062 Aedes and 836 Culex mosquitoes, of which approximately 12% (n = 226) were satiated with blood. Consequently, 101 putative viruses were identified, which included DNA and RNA viruses, and positive-stranded RNA viruses (+ssRNA) were the most abundant. According to viral diversity analysis, the composition of the viral structure was highly dependent on host species, and Culex mosquitoes showed richer viral diversity than Aedes mosquitoes. Although the virome of mosquitoes from different sampling habitats showed an overlap of 39.6%, multiple viruses were specific to certain habitats, particularly at the human-animal interface. Blood meal analysis found four mammals and one bird bloodmeal source, including humans, dogs, cats, poultry, and rats. Further, the blood feeding patterns of mosquitoes were found to be habitat dependent, and mosquitoes at the human-animal interface and from forests had a wider choice of hosts, including humans, domesticated animals, and wildlife, which in turn considerably increases the risk of spillover of potential zoonotic pathogens. To summarize, we are the first to investigate the virome of mosquitoes from multiple interfaces based on the One Health concept. The characteristics of viral community and blood feeding patterns of mosquitoes at the human-animal-environment interface were determined. Our findings should support surveillance activities to identify known and potential pathogens that are pathogenic to vertebrates.

Keywords: Meta-transcriptomic, Mosquito, Virome, Blood feeding, One health, Human-animal-environment interface

1. Introduction

According to WHO, vector-borne diseases account for >17% of all infectious diseases and cause over 700,000 deaths each year [1]. Mosquitoes are the primary virus vector, responsible for transmitting more than one-third of all arbovirus species [2]. Over the last few decades, several major outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases have been reported. While dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever viruses are transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, West Nile, epidemic B encephalitis, Japanese encephalitis, and Sindbis viruses are transmitted by Culex mosquitoes [3]. Further, parasites that cause malaria are transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes. As a result of global warming, the population of mosquitoes is growing and their geographical distribution is expanding, consequently increasing the risk of transmission of mosquito-borne diseases.

It is notable that 60%–75% of emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) are zoonotic and up to one-third of them are caused by vector-borne pathogens [1]. With a better understanding of the origin of EIDs, the One Health strategy recommends that zoonosis should be addressed at the human-animal-environment interface by establishing interdisciplinary, cross-sectoral, and cross-regional collaboration, which has gradually become a global consensus on the prevention and control EIDs [4]. Despite challenging, comprehensive surveillance of pathogens at the human, animal, and environmental levels is important for the early indication and proactive detection of zoonoses. Mosquitoes, which are blood-sucking arthropods with a variety of hosts, transmit zoonosis among vertebrates by biting them [5,6]. Mosquito blood meals, to some extent, reflect the virus-carrying status of hosts; in addition, mosquitoes are “flying syringes” for virus surveillance, and they overcome the difficulties associated with collecting samples from humans and animals [7,8]. Routine surveillance of mosquito virome at the human-animal-environment interface is pivotal for effective control and management of infectious diseases.

With the rapid development of next-generation sequencing technologies, meta-transcriptomic studies have been widely conducted for non-targeted, high-throughput detection and identification of known as well as new viruses. Moreover, the result of such studies can suggest the transcriptional activity of viruses in the host and their actual origin, reducing bias in the process of sample data analysis [9]. To date, meta-transcriptomics has been used in diverse surveillance projects, including detection of viruses in human sewage, monitoring of viruses in invertebrate (e.g., ticks) and vertebrate (e.g., pangolins) intermediate hosts, and tracing virus strains during outbreaks [10,11], demonstrating the potential of meta-transcriptomics to enhance the current arbovirus surveillance system.

To the best of our knowledge, the current mosquito surveillance system mainly focuses on vector diversity and abundance; a few studies have aimed to detect specific known pathogens [[12], [13], [14]]. In recent years, macrogenomic approaches have been used by a few studies to investigate viral abundance and diversity in mosquitoes [15,16]. However, a large-scale latitudinal and systematic survey of mosquito virome at the human-animal-environment interface remains unreported. Herein we aimed to comprehensively characterize the viral communities and blood feeding patterns of mosquitoes at the human-animal-environment interface and analyze the potential risk of cross-species transmission using meta-transcriptomic sequencing.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study sites and sample collection

Female adult mosquitoes were collected in the fall of 2021 (from September 1 to November 30, 2021) from five cities in Guangdong Province, China, where mosquito-borne infectious diseases are highly prevalent and there is a high incidence of dengue fever owing to its unique geographical location, high population density, and subtropical climate. Seven sampling habitats (residential areas, hospital, airplane, harbor, zoo, domestic sheds, and forest park) were selected, based on geographical and community characteristics, as well as distribution of people and animals. Mosquito & Fly Traps (Kungfu Dude Mosquito & Fly Trap, Wuhan Ji Xing Medical Technology Co., Wuhan, China), UV light traps for mosquito vector monitoring by the Chinese Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC), were used to collect mosquitoes at each site for approximately 12 h [17]. Electric mosquito extractors, along with the human entrapment method [18], were used outside from 7 am to 9 am and from 4 pm to 6 pm to catch more Aedes mosquitoes. On trap collection, mosquitoes were euthanized and preserved in dry ice. They were placed in labeled tubes containing dry ice, and sampling habitat, species, and satiation status were recorded. Subsequently, the samples were transported to a laboratory and stored at −80 °C for further processing. Mosquito species were initially identified by experienced field biologists based on morphological characteristics and further verified by analyzing the gene encoding cytochrome C oxidase subunit I (cox1) from sequencing data. In this study, considering biological hazards as well for cost-effectiveness, only female Aedes and Culex mosquitoes were subjected to further analyses.

2.2. Sample processing and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from 20 mosquito pools using HiPure Universal RNA Mini Kit (Magen, China) according to manufacturer instructions. RNA quality was evaluated using the Agilent 4200 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies), and all extractions had a qualified RNA integrity score. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was removed from purified total RNA using the ALFA-SEQ rRNA Depletion Kit (mCHIP, China) and Ribo-Zero™ Magnetic Gold Kit (Epicentre, USA) according to manufacturer instructions before library construction. Subsequently, double-stranded cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using REPLI-g Cell WGA & WTA Kit (150,052; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Sequencing libraries were then generated using NEB Next® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), based on manufacturer recommendations, and 150 bp paired-end sequencing of each library was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). All library preparation and sequencing procedures were performed by Magigene Company (Guangzhou, China).

2.3. Virus discovery and annotation

Sequencing reads were quality trimmed with Trimmomatic (v0.38) [19] using default settings for paired-end sequencing data to remove low-quality reads. They were then, aligned to Cx. quinquefasciatus (NC_014574.1) and Ae. albopictus (NC_006817.1) genomes, as well as ribosomal database(Silva 132, https://www.arb-silva.de/), to generate clean reads by BWA (v0.7.12-r1039) with default parameters [20]. Clean reads were de novo assembled using MEGAHIT (v1.0) with the following parameters: –k-min 21, −-k-max 191, −-min-contig-len 500 [21]. CD-HIT (v4.8.1) was used to cluster assembled contigs into unique contigs. The effect of assembly was evaluated by mapping clean reads to assembled contigs to calculate the utilization ratio of the reads. Next, non-redundant contigs were first compared against viral protein databases downloaded from GenBank using Diamond (v2.0.4) [22]; E value cutoff was set at 1E-5 to maintain high sensitivity and low false-positive rate. To further eliminate false-positive results, potential viral contigs were compared to the entire NCBI non-redundant protein databases. Besides, to obtain more virus-related information, unassembled reads were subjected to the same process as contigs. Finally, virus annotation was completed based on the taxonomic lineage information of the best alignment hit for each contig/read.

2.4. Characterization of viral abundance and diversity

To determine viral abundance, we mapped clean reads without host sequences and rRNA to viral contigs and reads using BWA. The abundance of each virus species was subsequently estimated as Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads (RPKM) using the ‘pileup.sh’ script from BBMap To prevent false positives, we removed data with RPKM less than or equal to 10. Alpha-diversity, reflecting observed richness or evenness for virus species within-group, was estimated using the vegan package, and overall significant levels for each factor (species, habitat, and satiation status) were evaluated by non-parametric tests. To explore and present variations in viral composition and expression of abundance between different groups, principal co-ordinate analysis with Bray-Curtis algorithm was applied to visualize similarities or differences among all samples. Linear discriminant analysis effect size was used to further identify species showing significant differences in abundance. Statistical analyses were performed using R v4.2.0 implemented in RStudio, and graphs were plotted using the R packages pheatmap and ggplot2. A map of species composition (circle diagram) was created using GraPhlAn (v1.1.3.1), and the relevant code was provided by Liu et al. (2019) [23]. (https://github.com/YongxinLiu/Note/tree/master/R/format2graphlan). Datasets and R code for the statistical tests in this study are available on GitHub (https://github.com/wuqin95/Mosquito-macrotranscriptomics).

2.5. Analysis of blood meals of mosquitoes

Satiated mosquitoes were individually split; due to the low number of mosquitoes satiated with blood, we merged mosquitoes collected from the aforementioned seven sampling habitats into three habitats based on the characteristics of the human-animal-environment interface. In other words, mosquitoes collected from the zoo and domestic sheds were classified into the animal group, while those collected from forest parks were classified into the environment group. All mosquitoes collected from the remaining four sampling habitats (i.e., residential areas, hospitals, airplanes, and harbor), which are dominated by human activity and represent important and regular sites monitored by CDC, were classified into the human group. All samples and sequencing data were processed as previously described to obtain unique contigs, which were first compared with the vertebrate protein database using Diamond, and then BLAST searches were performed against the non-redundant protein and nucleotide databases to remove false-positive results. The abundance of blood-fed hosts was assessed as stated above in Section 2.4.

2.6. Accession numbers

Raw sequence reads generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database (BioProject accession no. PRJNA859401).

3. Results

3.1. Mosquito sampling and identification

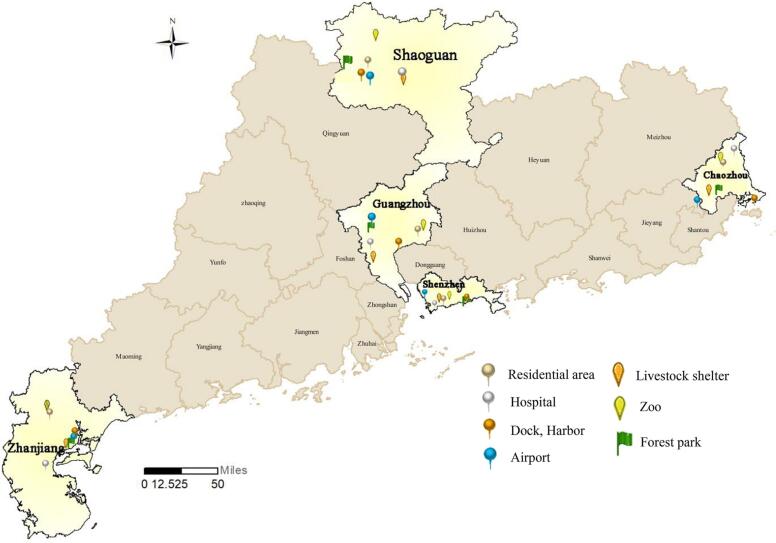

In the fall of 2021, based on the characteristics of the human-animal-environment interface, mosquito sampling was performed across multiple representative habitats in Guangdong, Shenzhen, Shaoguan, Chaozhou, and Zhanjiang cities in Guangdong Province, China (Fig. 1). Overall, 1898 female adult mosquitoes were collected, including 1062 Aedes and 836 Culex mosquitoes, of which approximately 12% (226) were satiated with blood (Table 1). Morphological identification indicated Ae. albopictus and Cx. quinquefasciatus to be the dominant species. The evolutionary tree constructed using cox1 identified five distinct species: Ae. albopictus, Cx. quinquefasciatus, and three new species, namely Culex spp., Ae. galloisioides, and Aedes spp. Ae. galloisioides appeared on the same evolutionary branch as Ae. galloisi, with 92% similarity, while the other new species were both distantly related to known mosquito species (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Map of mosquito sampling sites in Guangdong Province.

Table 1.

Mosquito samples and group division used for Meta-transcriptomic analysis and generated data.

| Pool names | Sampling habitat | Group |

Numbers | Raw reads | Clean reads | Contigs (unique) |

Viral contigs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat | Genus | Blood-engorged | |||||||

| AA | Animal habitat | Animal | Aedes | Yes | 34 | 48,055,802 | 5,603,665 | 5153 | 1106 |

| AC | Animal habitat | Animal | Culex | Yes | 46 | 49,644,596 | 282,142 | 2749 | 381 |

| CA | Livestock shelter | Animal | Aedes | No | 137 | 67,298,632 | 3,445,915 | 26,062 | 2526 |

| CC | Livestock shelter | Animal | Culex | No | 115 | 58,070,379 | 1,298,229 | 22,754 | 1062 |

| DA | Zoo | Animal | Aedes | No | 135 | 59,967,722 | 4,474,025 | 11,008 | 1435 |

| DC | Zoo | Animal | Culex | No | 100 | 55,020,875 | 915,138 | 7877 | 706 |

| EA | Forest habitat | Environment | Aedes | Yes | 20 | 52,773,995 | 2,572,067 | 7296 | 573 |

| EC | Forest habitat | Environment | Culex | Yes | 28 | 46,329,323 | 1,346,191 | 23,903 | 2218 |

| HA | Human habitat | Human | Aedes | Yes | 42 | 54,004,660 | 2,579,514 | 11,432 | 1318 |

| HC | Human habitat | Human | Culex | Yes | 56 | 46,405,017 | 274,559 | 1936 | 285 |

| JA | Airport | Human | Aedes | No | 140 | 62,197,081 | 4,012,645 | 8553 | 1048 |

| JC | Airport | Human | Culex | No | 105 | 49,663,659 | 779,858 | 4801 | 463 |

| MA | Dock, Harbor | Human | Aedes | No | 133 | 59,305,596 | 1,340,611 | 2309 | 327 |

| MC | Dock, Harbor | Human | Culex | No | 90 | 58,171,968 | 707,394 | 6177 | 832 |

| SA | Forest park | Environment | Aedes | No | 143 | 67,000,906 | 5,424,225 | 18,263 | 2232 |

| SC | Forest park | Environment | Culex | No | 88 | 60,731,558 | 1,440,013 | 4453 | 610 |

| YA | Hospital | Human | Aedes | No | 152 | 62,022,201 | 7,715,424 | 9366 | 1357 |

| YC | Hospital | Human | Culex | No | 110 | 52,379,710 | 1,361,917 | 25,591 | 2461 |

| ZA | Residential area | Human | Aedes | No | 126 | 56,108,150 | 4,758,768 | 11,742 | 1162 |

| ZC | Residential area | Human | Culex | No | 98 | 55,378,604 | 445,698 | 4820 | 585 |

| Total | 1898 | 1,120,530,434 | 50,777,998 | 216,245 | 22,687 | ||||

3.2. Overview of mosquito virome

On average, 56,026,522 (46,329,323-67,298,632) raw reads per pool were generated by meta-transcriptomic sequencing, with 4% (1%–12%) on average remaining after quality control and removal of host sequences and rRNA. Further, 1936–26,062 unique contigs were assembled (overall assembly efficiency, 88%), and they along with unassembled reads were used for virus discovery and characterization. A total of 101 putative viruses were identified from all samples, which included DNA and RNA viruses, positive-stranded RNA viruses (+ssRNA) accounted for the majority of virus species (Fig. 2A). Nineteen virus species belonged to unassigned phyla and the remaining belonged to 10 known phyla and 31 viral families. In this study, Tombusviridae, Reoviridae, Alphatetraviridae, Solemoviridae, Phasmaviridae, and Mesoniviridae were generally found in mosquito pools. Tombusviridae, Reoviridae, and Alphatetraviridae were the most abundant among Aedes mosquitoes, while Orthomyxoviridae was more common among Culex mosquitoes (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, unclassified viruses occupied a non-negligible place in mosquito virome, a phenomenon that was particularly evident in case of Culex. The abundance of different virus species markedly varied, ranging from a few hundred to several hundred thousand. Although total RPKM for each species was mostly concentrated within 5000, the value for some viruses (e.g., Zhejiang mosquito virus 3, Fako virus, Culex pipiens orthomyxo-like virus, Culex pipiens-associated Tunisia virus, Guangzhou sobemo-like virus, Shuangao chryso-like virus 1, and Wuhan mosquito virus 6) was ≥100,000. Fig. 2C shows standardized abundance profiles of all viruses identified in this study and corresponding species clade.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the mosquito virome identified in this study. (A) Virus categories and corresponding number of species. (B) Viral composition of each pool at the family level. (C) Cladogram of viruses determined in this study. A total 101 virus species are displayed, and the circle graph colored by virus phylum. ‘Unassigned’ represents biological classification annotation for corresponding virus is unknown so far. Bars on the periphery of the circle represents the normalized relative abundance of each virus. The top 25% of viruses in relative abundance are identified in blue boxes and others are marked by purple triangle. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3. Viral diversity analysis and evolution by host species, sampling habitats and host satiation status

We compared viral abundance and species number distribution across host species, sampling habitats, and host satiation status using operational taxonomic units (OTUs), RPKM, and alpha-diversity index (Fig. 3). For mosquito species, the observed OTUs in all pools was range 21 from 42, and there were no significant differences between Aedes and Culex. Although total viral abundance did not significantly differ for mosquito species, the distribution of total viral abundance in Culex pools appeared to be more scattered and unsymmetrical. Interestingly, the Shannon-Wiener index, reflective of viral diversity, for Culex was higher than that for Aedes, with a statistically significant difference (p<0.001). However, no significant differences were found in observed OTUs, abundance, or alpha-diversity on comparing the virome of mosquitoes from different sampling habitats (OTU: p = 0.6; abundance: p = 0.34; Shannon: p = 0.74) or at different satiation statuses (OTU: p = 0.91; abundance: p = 0.74; Shannon: p = 0.84).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of observed richness (OTU), abundance (RPKM), and alpha-diversity (Shannon wiener index). Statistical tests and P values are shown at the top of each graph. In the boxplots, horizontal lines show the median, and the upper and lower ends of the box represent inter-quartiles range, and the maximum and minimum values are at each end of the vertical line.

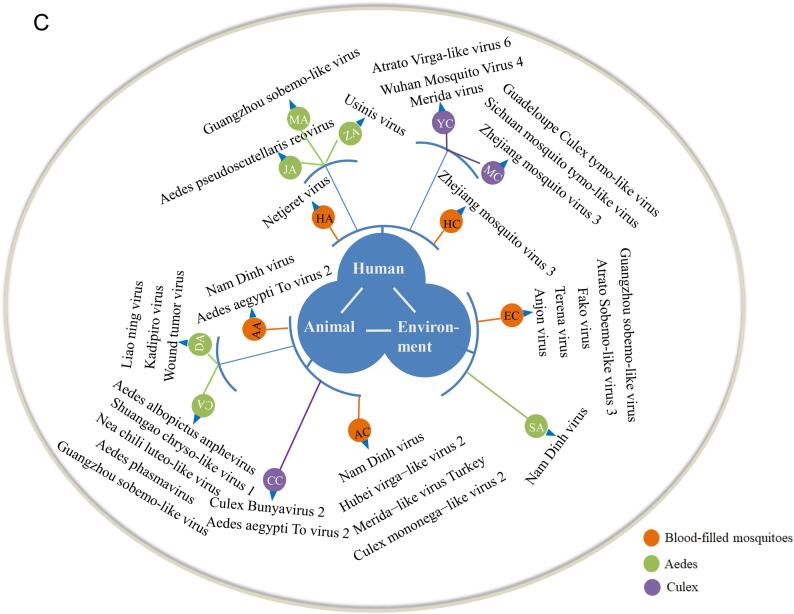

Herein >50% identified virus species (51/101) were common between Culex and Aedes, with Culex showing more distinctive virus species. Moreover, the virome of mosquitoes from different sampling habitats showed an overlap of 39.6%, and the virome of mosquitoes in the human group shared the most viral diversitywith that of those in the animal group (Fig. 4A). We next performed a principal co-ordinate analysis to assess the effects of species, sampling habitats and satiation status on mosquito virome composition. Our results indicated that viral communities were primarily structured by host species rather than by sampling habitats or satiation status of the host (Fig. 4B). Heatmaps based on normalized abundance of virus species revealed a similar viral community composition in the same mosquito species, while some viruses just appeared or showed obviously higher abundance in certain sampling habitats (Fig. S2). To show the distribution of distinctive viruses more clearly under different habitats, we have listed them in Fig. 4C according to heatmaps. We found that the number of those virus species specific to a habitat in mosquitoes in the animal group was higher than that in those in the human and environment groups. Although we found no arborviruses that are known to impact human or animal health, Nam Dinh virus (NDiV), a potential vector-borne virus, showed relatively high expression levels in blood-filled mosquitoes collected from animal and forest habitats.

Fig. 4.

(A) Venn diagrams showing virus species shared between different host species, sampling habitats and host satiation status. The size of the oval has no real significance, and the colors represent the different groupings. (B) A Principal Co-ordinates Analysis (applying Bray-Curtis algorithm) for viral composition by host species, host habitats, and satiation status. Circles show 95% normal probability ellipse for each species group (left panel). (C) The virus with highest abundance in each sample after normalized by virus species. Circles refer to different pools with name marked in and its colour in orange, green, and purple represent blood-filled mosquitoes, Aedes and Culex, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Finally, linear discriminant analysis effect size was applied to discover virus species with significant differences between host species. In total, 24 virus species, all of which were insect-specific viruses, were found to be significantly different. For virome carried by Culex, Zhejiang mosquito virus 3, Wuhan mosquito virus 6, Hubei virga_like virus 2 were the dominant virus species. However, in comparison to Culex, Sarawak virus, Tiger mosquito bi_segmented tombus_like virus, Fako virus and some flaviviruses were more likely to influence viral communities carried by Aedes (Fig. S3). Further, we compared changes in abundance in all pools subjected to sequencing for each individual virus species identified by linear discriminant analysis (Fig. 5). Several viruses were, in general, found in all habitats, such as Aedes pseudoscutellaris reovirus, Fako virus, Sarawak virus, and Tiger mosquito bi-segmented tombus-like virus, which were much more abundant than most other virus species, indicating that viruses with high abundance levels are more likely to be prevalent in wide-ranging ecology or geography. On the country, some viruses with low abundance may be found only at the site of epidemic. Interestingly, some viruses with high abundance were also prevalent in certain habitats; for example, Wuhan mosquito virus 4 showed high abundance levels in hospital habitat, while Culex pipiens orthomyxo-like virus was not found in this habitat. This indicated, that assessing multiple sampling habitats is highly desirable to identify more and diverse viruses.

Fig. 5.

The abundance levels for selected individual virus species in different sampling habitats. The viruses were selected based on LDA result, and histograms are colored by host species and host satiation status. The three columns on the left are Aedes pools and the three columns on the right are Culex pools. The pools information is shown at the bottom of each bar and were explanted in Table 1.

3.4. Blood feeding patterns of mosquitoes at the human-animal-environment interface

We analyzed the vertebrate hosts of mosquito blood meals and visualized them at corresponding human, animal, and environment habitats (Fig. 6). Five principal vertebrates, including four mammals and one bird, were found. In the same habitat, Culex mosquitoes were found to feed on more animal species than Aedes mosquitoes, which are anthropophilic. In places with high human activity, such as hospital, airplane, harbor, and residential areas, humans were the main target of mosquitoes, in addition to pets (e.g., dogs and cats) in some cases. On poultry farms, mosquitoes mainly targeted poultry and watchdogs. Besides, we found Rattus norvegicus and Mus musculus in blood meals of mosquitoes collected from zoo, domestic sheds, and forest park, where are more likely to be discovery rats during the day. In general, our results showed that at the human-animal-environment interface, humans, pets, domestic animals or poultry, and rats were the most common and important source of blood meals for mosquitoes, implying that mosquitoes can increase the risk of transmission of potential or known zoonotic diseases between humans and animals.

Fig. 6.

The characteristic of blood meal of mosquito at the human-animal-environment interface. The green image on the grey circle shows the surroundings of the sampling sites and potential vertebrates at those sites. Those sampling sites were divided into three groups: human, animal and environment. The black image inside the grey circle refer to the consist of blood meals of mosquitoes, and the bar in green point out their relative abundance. The different groups are separated by a thick purple line and the different mosquito species are separated by a thin grey line. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

Animal-derived viruses play an important role in the occurrence of potential EIDs. For example, the West Nile virus is maintained in enzootic cycles primarily involving Culex mosquitoes and avian hosts, with epizootic spread to mammals, including humans [24]. The complex combination of human activities, ecological damage, and socioeconomic factors have led to an increase in direct interactions among humans, domestic animals, and wildlife, making it challenging to separate animal health from human health [25]. In addition, following the rapid development of the economy and society, the natural world, teeming with diverse wildlife, has witnessed constant changes and transformed to an anthropogenic landscape, increasing the risk of spillover of sylvatic pathogens to humans and domestic animals [26,27]. As a result, routinely monitoring anthropophilic mosquitoes around residential areas and focusing on specific pathogens are no longer sufficient to prevent and control modern infectious diseases, particularly emerging ones [28]. Herein guided by the One Health strategy, we for the first time investigated the virome carried by mosquitoes sampled from different habitats, potentially comprising pathogens from the general population (residential area), medical origin (hospital), foreign origin (airplane, harbor), animal origin (zoo and domestic sheds), and forest origin (forest park).

In this study, Ae. albopictus and Cx. quinquefasciatus were the most common species of mosquitoes collected, which is consistent with routine mosquito vector surveillance data from Guangdong Province [29,30]. Although mosquitoes were broadly divided into two genera, a significant difference in terms of viral communities was found between Aedes and Culex mosquitoes, with the latter harboring more viruses, indicating that host genetic background substantially influences viral diversity, which is similar to the results of most previous studies [31,32]. Further, we realized that some viruses were specific to mosquito species; for example, some flaviviruses were specific to Aedes, implying that targeted measures need to be implemented against certain mosquito-borne diseases. To explain further, it is well established that dengue fever can be prevented and controlled by specifically monitoring and reducing the population of Aedes mosquitoes. Although mosquitoes in different habitats share some virus species, quite a few viruses are unique to a specific habitat, which suggests that it is pivotal to comprehensively evaluate mosquito virome at the human-animal-environment interface to discover more virus species and to avoid overlooking potential emerging pathogens.

The carriage rate of mosquito-borne viruses in mosquitoes is strongly associated with corresponding mosquito-borne disease outbreaks or epidemics in animals or humans. Numerous studies have demonstrated an overwhelming reduction in the onset of various infectious diseases, which can be attributed to a series of nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as international/internal movement restrictions that discouraged the introduce of travel-associated pathogen, implemented by most countries during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic to suppress its transmission [33,34]. As per official statistics, the incidence of dengue fever in Guangdong, China in 2021 decreased by 99% compared to the previous 5 years, and other mosquito-borne diseases, such as encephalitis B, also witnessed a reduction in the number of cases [35]. Therefore, herein we did not detect any known medical pathogens, which validates the positive implications of nonpharmaceutical interventions on arboviral diseases from the perspective of mosquito molecular epidemiology.

We analyzed the blood feeding patterns of mosquitoes at the human-animal-environment interface, which is important to assess the potential risk of cross-species transmission of pathogens. We found that mosquitoes mostly targeted humans and dogs, which is attributable to the high populations of these hosts and their extensive range of activities, while domestic animals and wildlife were usually targeted only in certain habitats where these hosts are more prevalent, indicating blood feeding patterns of mosquitoes are highly habitat dependent. Meanwhile, relative to Aedes mosquitoes, Culex mosquitoes undoubtedly are zoophilic and feed on various vertebrates, including domestic animals, pets, and wildlife, in the same habitat, thus they show the higher potential of transmitting emerging arboviruses from wildlife to domestic animals and humans. Mosquito blood meals also can be applied to easily survey the epidemic characteristics of viruses of known pathogenicity over space and time. For instance, Barbazan et al. detected H5N1 virus sequences in blood-engorged mosquito pools collected from a poultry farm during an outbreak of avian influenza in Thailand [36]. We did not detect any pathogens in this study; nevertheless, future disease surveillance efforts should focus on this aspect. Interestingly, we found a relative higher abundance of NDiV, a novel insect nidovirus first found in Culex spp., in blood-engorged mosquitoes collected from the human-animal interface, with rats being the host. This indicates that NDiV may be endemic in rats, although further studies on rats in the same region are warranted to validate this hypothesis. NDiV was once of interest because of its similar biological structure to coronavirus; however, some controversy surrounds its pathogenicity [37,38]. Few in vitro experiments have shown that NDiV can only infect mosquito cells, not vertebrate cells, but Wang et al. confirmed that NDiV showed a certain level of pathogenicity in mice on inoculating the mouse brain with NDiV [39]. Moreover, Hao first identified NDiV in Rattus norvegicus, a common rodent, collected from Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province [40]. Further studies are needed to verify the potential pathogenicity of NDiV in humans and animals.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the impact of COVID-19 on other infectious diseases and limited sampling regions, we did not detect any medically relevant pathogens, making it difficult to assess the risk of disease transmission at different interfaces directly. In the future, similar studies should be conducted at different temporospatial levels to determine the significance of mosquito virome surveillance at the human-animal-environment interface. Second, mosquito sampling was limited to fall; we missed the peak season of mosquito-borne diseases, limiting our capability to study the implication of seasons on virome composition. Finally, some important data, such as those pertaining to animal quantity, type, and population size, were not collected, limiting an in-depth understanding of the blood feeding patterns of mosquitoes.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate mosquito virome based on the One Health concept. We explored the characteristics of viral community structure and blood feeding patterns at the human-animal-environment interface. We found that compared to Aedes mosquitoes, Culex mosquitoes are critical vectors of cross-species transmission of pathogens as they carry a more extensive range of virus species and feed on a wide variety of hosts. Further, our results indicated that the blood feeding patterns of mosquitoes are habitat dependent, and mosquitoes at the human-animal interface and from forests have a wider choice of hosts, including humans, domesticated animals, and wildlife, which increases the risk of spillover of potential zoonotic pathogens. In the future, we should aim to strengthen mosquito virome surveillance at the human-animal-environment interface to discover more known as well as new viruses that are pathogenic to vertebrates.

Author statement

QW, and CG conceived the project. QW, ZG and JL contributed to the writing of the paper. QW, XL, BY, and QL performed laboratory experiments for viral metagenomics. QW and CG performed bioinformatics analysis. QW, CG, XL, BY and QL performed sample collection. All of the authors have read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We claim that there is no conflict of interest associated with the paper entitled “A Meta-transcriptomic Study of Mosquito Virome and Blood Feeding Patterns at the Human-Animal-Environment Interface in Guangdong Province, China”.

Acknowlegement

This work was funded by the the National Key Research and Development Project (2018YFE0208000), funder is Jiahai Lu.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100493.

Contributor Information

Cheng Guo, Email: cg2984@cumc.columbia.edu.

Xiao-kang Li, Email: lixk35@mail2.sysu.edu.cn.

Zhong-Min Guo, Email: guozhm@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Jia-Hai Lu, Email: lujiahai@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material: Fig. S1. Identification of mosquito species based on phylogenetic analysis of cox1 revealed by meta-transcriptomic sequencing. Mosquitoes identified in this study are marked in blue.

Fig. S2. Heatmap showing the normalized abundance of each virus species at different host species, host habitats and host satiation status.

Fig. S3. Species with significantly different abundance in Aedes and Culex mosquitoes. The histogram shows species with differences in LDA scores >2, and the length of the bar chart represents the effect size of significantly different species.

Data availability

I have shared the link to my data and code in my manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO WHO Vector-Borne Diseases. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs387/en/

- 2.de Almeida J.P., Aguiar E.R., Armache J.N., Olmo R.P., Marques J.T. The virome of vector mosquitoes. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021;49:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pettersson J.H., Shi M., Eden J.S., Holmes E.C., Hesson J.C. Meta-transcriptomic comparison of the RNA viromes of the mosquito vectors culex pipiens and culex torrentium in Northern Europe. Viruses. 2019;11(11) doi: 10.3390/v11111033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.G.F.G.J.C.G.Z.J.X.J. Lu The 697th Xiangshan Science Conference consensus report on One Health and human health. One Heath Bull. 2021;1(1):3–9. (2021) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apperson C.S., Harrison B.A., Unnasch T.R., Hassan H.K., Irby W.S., Savage H.M., Aspen S.E., Watson D.W., Rueda L.M., Engber B.R., Nasci R.S. Host-feeding habits of Culex and other mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in the borough of Queens in new York City, with characters and techniques for identification of Culex mosquitoes. J. Med. Entomol. 2002;39(5):777–785. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-39.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molaei G., Andreadis T.G., Armstrong P.M., Anderson J.F., Vossbrinck C.R. Host feeding patterns of Culex mosquitoes and West Nile virus transmission, northeastern United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12(3):468–474. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.051004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkmann A., Nitsche A., Kohl C. Viral metagenomics on blood-feeding arthropods as a tool for human disease surveillance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17(10) doi: 10.3390/ijms17101743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temmam S., Davoust B., Berenger J.M., Raoult D., Desnues C. Viral metagenomics on animals as a tool for the detection of zoonoses prior to human infection? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15(6):10377–10397. doi: 10.3390/ijms150610377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y.Z., Shi M., Holmes E.C. Using metagenomics to characterize an expanding Virosphere. Cell. 2018;172(6):1168–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao W.H., Lin X.D., Chen Y.M., Xie C.G., Tan Z.Z., Zhou J.J., Chen S., Holmes E.C., Zhang Y.Z. Newly identified viral genomes in pangolins with fatal disease. Virus Evol. 2020;6(1) doi: 10.1093/ve/veaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey E., Rose K., Eden J.S., Lo N., Abeyasuriya T., Shi M., Doggett S.L., Holmes E.C. Extensive diversity of RNA viruses in Australian ticks. J. Virol. 2019;93(3) doi: 10.1128/JVI.01358-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakran-Lebl K., Camp J.V., Kolodziejek J., Weidinger P., Hufnagl P., Cabal Rosel A., Zwickelstorfer A., Allerberger F., Nowotny N. Diversity of West Nile and Usutu virus strains in mosquitoes at an international airport in Austria. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022;69(4):2096–2109. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang Y., Li X.S., Zhang W., Xue J.B., Wang J.Z., Yin S.Q., Li S.G., Li X.H., Zhang Y. Molecular epidemiology of mosquito-borne viruses at the China-Myanmar border: discovery of a potential epidemic focus of Japanese encephalitis. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2021;10(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s40249-021-00838-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson T., Braack L., Guarido M., Venter M., Gouveia Almeida A.P. Mosquito community composition and abundance at contrasting sites in northern South Africa, 2014-2017. J. Vector Ecol. 2020;45(1):104–117. doi: 10.1111/jvec.12378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He X., Yin Q., Zhou L., Meng L., Hu W., Li F., Li Y., Han K., Zhang S., Fu S., Zhang X., Wang J., Xu S., Zhang Y., He Y., Dong M., Shen X., Zhang Z., Nie K., Liang G., Ma X., Wang H. Metagenomic sequencing reveals viral abundance and diversity in mosquitoes from the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia region, China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiuya T., Masiga D.K., Falzon L.C., Bastos A.D.S., Fèvre E.M., Villinger J. A survey of mosquito-borne and insect-specific viruses in hospitals and livestock markets in western Kenya. PLoS One. 2021;16(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang Y., Zhang W., Xue J.B., Zhang Y. Monitoring mosquito-borne arbovirus in various insect regions in China in 2018. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.640993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong-Ming H.K. Yan, Chun-chun Zhao, Xiu-ping Song, Qin-feng Zhang, Jun Wang, Qi-yong Liu. Research advances in common methods and techniques for mosquito surveillance. Chin. J. Vector Biol. Control. 2020;31:108–112. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2010;26(5):589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li D., Luo R., Liu C.M., Leung C.M., Ting H.F., Sadakane K., Yamashita H., Lam T.W. MEGAHIT v1.0: A fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods (San Diego, Calif.) 2016;102:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchfink B., Xie C., Huson D.H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 2015;12(1):59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J., Liu Y.X., Zhang N., Hu B., Jin T., Xu H., Qin Y., Yan P., Zhang X., Guo X., Hui J., Cao S., Wang X., Wang C., Wang H., Qu B., Fan G., Yuan L., Garrido-Oter R., Chu C., Bai Y. NRT1.1B is associated with root microbiota composition and nitrogen use in field-grown rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37(6):676–684. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray T.J., Webb C.E. A review of the epidemiological and clinical aspects of West Nile virus. Int. J. General Med. 2014;7:193–203. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S59902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones K.E., Patel N.G., Levy M.A., Storeygard A., Balk D., Gittleman J.L., Daszak P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451(7181):990–993. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrientos-Roldán M.J., Abella-Medrano C.A., Ibáñez-Bernal S., Sandoval-Ruiz C.A. Landscape anthropization affects mosquito diversity in a deciduous forest in southeastern Mexico. J. Med. Entomol. 2022;59(1):248–256. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjab154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendy A., Hernandez-Acosta E., Valério D., Mendonça C., Costa E.R., Júnior J.T.A., Assunção F.P., Scarpassa V.M., Gordo M., Fé N.F., Buenemann M., de Lacerda M.V.G., Hanley K.A., Vasilakis N. The vertical stratification of potential bridge vectors of mosquito-borne viruses in a central Amazonian forest bordering Manaus, Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):18254. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75178-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musa A.A., Muturi M.W., Musyoki A.M., Ouso D.O., Oundo J.W., Makhulu E.E., Wambua L., Villinger J., Jeneby M.M. Arboviruses and Blood Meal Sources in Zoophilic Mosquitoes at Human-Wildlife Interfaces in Kenya, Vector borne and zoonotic diseases (Larchmont, N.Y.) 2020;20(6):444–453. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2019.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ning G.Y.-H. Zhao, Hai-xia Wu, Xiao-bo Liu, Yu-juan Yue, Dong-sheng Ren, Gui-chang Li, Xiu-ping Song, Liang Lu, Qi-yong Liu. National vector surveillance report on mosquitoes in China, 2019. Chin. J. Vector Biol. Control. 2020;31:395–400. [Google Scholar]

- 30.L.J.J.Y.-m.Z.J.-y.Z.Z.-y.L. Xiao-ning, L.X.-y.W.H.-y.L.Y.Y.Z.-c.L. Lei Investigation on species and distribution of mosquitoes in Guangzhou. Chin. J. Hyg. Insect. Equip. 2019;25:244–246. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi M., Neville P., Nicholson J., Eden J.S., Imrie A., Holmes E.C. High-resolution Metatranscriptomics reveals the ecological dynamics of mosquito-associated RNA viruses in Western Australia. J. Virol. 2017;91(17) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00680-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thongsripong P., Chandler J.A., Kittayapong P., Wilcox B.A., Kapan D.D., Bennett S.N. Metagenomic shotgun sequencing reveals host species as an important driver of virome composition in mosquitoes. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):8448. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87122-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Q., Dong S., Li X., Yi B., Hu H., Guo Z., Lu J. Effects of COVID-19 non-pharmacological interventions on dengue infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.892508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang L., Liu Y., Su W., Liu W., Yang Z. Decreased dengue cases attributable to the effect of COVID-19 in Guangzhou in 2020. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.G.H.C. Commission Statutory Reported Infectious Disease Epidemic in Guangdong Province in 2021. 2022. http://wsjkw.gd.gov.cn/gkmlpt/content/3/3823/mpost_3823980.html#2571

- 36.Barbazan P., Thitithanyanont A., Missé D., Dubot A., Bosc P., Luangsri N., Gonzalez J.P., Kittayapong P. Detection of H5N1 avian influenza virus from mosquitoes collected in an infected poultry farm in Thailand, Vector borne and zoonotic diseases (Larchmont, N.Y.) 2008;8(1):105–109. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nga P.T., Parquet Mdel C., Lauber C., Parida M., Nabeshima T., Yu F., Thuy N.T., Inoue S., Ito T., Okamoto K., Ichinose A., Snijder E.J., Morita K., Gorbalenya A.E. Discovery of the first insect nidovirus, a missing evolutionary link in the emergence of the largest RNA virus genomes. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vasilakis N., Guzman H., Firth C., Forrester N.L., Widen S.G., Wood T.G., Rossi S.L., Ghedin E., Popov V., Blasdell K.R., Walker P.J., Tesh R.B. Mesoniviruses are mosquito-specific viruses with extensive geographic distribution and host range. Virol. J. 2014;11:97. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.W.D.q.L.Q.L.K.f.Z.J.m.Z.J.l.L. Xiao⁃na Study on the biological characteristics of a new arbovirus: Nam Dinh virus. Chin. J. Vector Biol. Control. 2016;27:443–446. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hao W. Sun Yat-sen University; Guangdong: 2020. Diversity and Molecular Epidemiology of Viruses in Wild Small Mammals. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material: Fig. S1. Identification of mosquito species based on phylogenetic analysis of cox1 revealed by meta-transcriptomic sequencing. Mosquitoes identified in this study are marked in blue.

Fig. S2. Heatmap showing the normalized abundance of each virus species at different host species, host habitats and host satiation status.

Fig. S3. Species with significantly different abundance in Aedes and Culex mosquitoes. The histogram shows species with differences in LDA scores >2, and the length of the bar chart represents the effect size of significantly different species.

Data Availability Statement

I have shared the link to my data and code in my manuscript.