Abstract

Although previous online learning studies have looked at how student outcomes are influenced in different settings, this study is unique in that it looks at the role of COVID-19 as a particular stressor. This study discussed how students’ perceptions of health risks of COVID-19 (PHRC) influenced their academic performance through emotional exhaustion. This study also looked at how mindfulness and online interaction quality (OIQ) affected PHRC’s direct effects on exhaustion, as well as PHRC’s indirect effects on academic performance via exhaustion. The data for the current study were collected from 336 students in three waves who were studying online during COVID-19. The results through structural equation modeling (SEM) revealed that PHRC influenced academic performance. The results further revealed that mindfulness and OIQ attenuated the direct effects of PHRC on emotional exhaustion as well as indirect effects on academic performance through emotional exhaustion. This study provides some novel implications for practice and research.

Keywords: Health risks of COVID-19, Emotional exhaustion, Mindfulness, Online interaction quality, Academic performance, COR theory

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the education sector at all levels. All around the globe, academic institutions have either temporarily shut down or deployed localized closures, affecting nearly 1.7 billion students (Mahdy, 2020). Several universities and colleges have rescheduled or canceled all college and university activities in order to reduce crowding and thus virus transmission. These actions, on the other hand, have greater economic, psychological, performance-based, and social consequences for students. COVID-19 is asymptomatic and has a high death rate, unlike past epidemics (Jeftić et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2022). People become more supportive of life and more pro-social towards humanity when faced with a disaster that causes many deaths (Curșeu et al., 2021; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020). COVID-19 is also a more severe episode with long-term consequences for students’ mental health and academic performance (Atlam et al., 2022).

Health risk perceptions are critical element of protective behavior because they assert how people interpret risks (Smith et al., 2020). Awareness of a virus such as COVID-19 can affect an individual’s mindset and behavior (Finsterwalder et al., 2020). It has been stated that individuals at risk usually are more inclined to suicidal behavior and generally come close to suicide through searching information and news regarding self-harm and suicidal behaviors on internet (Solano et al., 2016). Since past research has primarily concentrated on the effects of online learning, artificial intelligence, and teacher quality on student attitude during COVID-19 (Atlam et al., 2022; Clark et al., 2021; Iglesias-Pradas et al., 2021) and the power (e.g., severity, interruption, and uniqueness) of COVID-19 on student career and consequences (Khalafallah et al., 2021; Safi’i et al., 2021), this study focuses on the impact of health risks perceived by students during this universal health crisis, which represents a black box that needs to be investigated.

As per the conservation of resources (COR) theory, individuals can burnout if they assume their resources, like as their health, performance, or environment, are threatened or at risk (Hobfoll, 1989). Students who are more worried about resources loss risks than study-related work may experience exhaustion or burnout during COVID-19 (Khalafallah et al., 2021). It has been stated that high occupational psychological and emotional efforts can cause exhaustion (Abram & Jacobowitz, 2021; Naseer Abbas Khan et al., 2021). As per COR theory the perceived health risks of COVID-19 (PHRC), a kind of threat in the external environment can lead towards exhaustion, resulting in lower study performance. Investigations on how epidemic health threats (such as COVID-19) affect student exhaustion and academic performance are severe, furthermore this study try to investigate that how students can utilize their internal or external resources to lessen these adverse effects?

Mindfulness is the fundamental human ability/resource to be fully present without becoming overly reactive or exhausted by what is going on around us (Langer, 1989; Mackenzie et al., 2006). During COVID-19, mindfulness has been critical in guarding individuals from psychological well-being issues (Van Vu et al., 2022) and in improving engagement and performance (Reb et al., 2018). According to COR theory, mindfulness, which is regarded as an individual resource, may be able to offset the effects of PHRC on student exhaustion and performance. Additionally, recent findings link mindfulness to a variety of outcomes as well as cognitive and emotional disorders (Grossman et al., 2004; Gu et al., 2015). Furthermore, it has been stated that online interaction quality (OIQ) helps learners who are learning online to develop more social relationships to overcome the issues of COVID-19 risk and enhance their social capital (Zheng et al., 2020). In this study, the OIQ refers to students’ willingness to interact with others virtually in an online learning environment to gain external environmental resources for reducing the health-related risks of COVID-19. Even though OIQ can provide an opportunity to students to interact with peers and discuss any physical or psychological loss and gain support from the peers for resources conservation during this health emergency (Bano et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2022a). Nevertheless, there has been little research into the role of mindfulness and OIQ in moderating the effect of PHRC linked with a global health emergency on exhaustion and student performance.

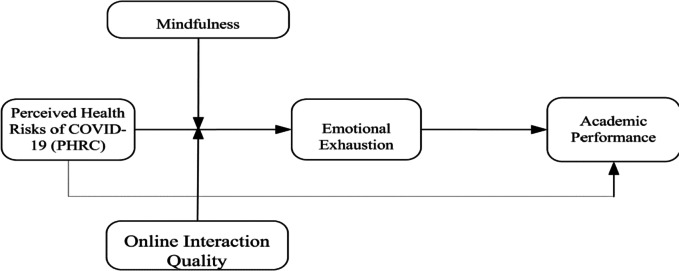

This research will make several valuable contributions. First, it contributes to a better awareness of how students’ perspectives of health risks influence their performance in the perspective of COVID-19. Because more investigation on context cue compassion is required (i.e., COVID-19 as a precise situation), this scholarship will address the latest calls for more investigation (Atlam et al., 2022; Khan, 2021b; Van Vu et al., 2022) on the mindfulness and psychological health impacts of current pandemic. Second, this study lends support to the COR theory by elucidating the effects of perceived health risks on students as well as the role of their resources such as mindfulness and social resources such as OIQ during a crisis. Since COR theory has been used in the “normal” context (Khan et al., 2020; Ouweneel et al., 2011), the boundaries of this theory are extended in the current study to the highly unpredictable context of a worldwide pandemic (e.g., COVID-19). Finally, this research contributes to our understanding of mindfulness’s and OIQ’s moderation effects in the direct and indirect relationship among constructs during an emergency. It explores how mindfulness, as an individual resource, and OIQ as a social resource moderates PHRC’s direct effects on exhaustion and its indirect effects on academic performance via exhaustion, using the COR theory (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Research model

Theoretical foundation and hypotheses development

PHRC, emotional exhaustion and academic performance

Individuals’ perceptions of risk are their beliefs regarding any risk that could precisely influence them or other peoples (Claassen et al., 2009; Youn & Shin, 2019). According to (Day et al., 2009), risk perceptions have two aspects: cognitive, or the perception of the likelihood of being wounded, and emotional, or the expressive response to the danger, which manifests as nervousness. Severity and frequency are evaluations of the environment’s capacity for instigating harm and contributing to students’ sense of insecurity in the risk evaluation model, whilst control is an expression of students’ ability to cope with these susceptible emotional states. COVID-19 is a hidden threat to the global population’s health and well-being, with a high inherent danger and widespread distribution (Khan, 2021a; Smith et al., 2020). As a result, students who feel exposed are afraid, and can suffer from psychological health problems and exhaustion (Co et al., 2021; Khalafallah et al., 2021; Li & Khan, 2022).

COVID-19 is unique among common health threats in that it poses not only physiological but also psychological health risks (Bettinsoli et al., 2020; Khan, 2021b). It is a source of stress for many students, not just for a few selected groups of students (Co et al., 2021). Because COVID-19 is a mainly unexpected and uncertain worldwide catastrophe with ongoing variations and causes swings in persons’ profound beliefs, students become worried and down when they do not know which potential dangers they may face (Lohani et al., 2022; Zhao & Zhou, 2020). Prior research has also demonstrated the significance of testing the impact of a pandemic’s perceived health risks on organizational employees (Van Vu et al., 2022). As a result, more research into how PHRC affects students’ mental health and performance is needed.

Emotional exhaustion is the emotional state that someone’s emotional resources have been depleted by the things they’ve done, as well as the psychological inability to deal (Akbar & Akhtar, 2017; Halbesleben & Buckley, 2004; Khan, 2022). To put it another way, emotional exhaustion is the emotional state of a person’s lack of resources and emotional fatigue (Hochwarter et al., 2007; Prosser et al., 1997; Yu et al., 2019). Exhaustion and burnout are mental health concerns, with serious implications such as depression (Roche et al., 2014), anxiety (McCarthy et al., 2021), as well as reduced performance (Wincent & Örtqvist, 2009). For testing the impacts of exhaustion during COVID-19, COR theory has been applied in recent research (Van Vu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021). According to COR theory, demands reduce resources (Ali et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2022b), and the processes related to resource depletion result in emotional exhaustion (Ito & Brotheridge, 2003). Resources are the “things that people value, with an emphasis on objects, states, conditions, and other things,” (Carlson et al., 2012; Toker et al., 2015). As per COR theory, resource losses are more visible than resource gains, and people must spend resources to increase resources, safeguard themselves from losing resources, and recover from resource losses (Hobfoll, 1989).

A few theoretical underpinnings follow from these core rules: First, people with more resources can easily acquire more resources, whereas people with fewer resources are more likely to encounter resource losses. Second, initial resource losses result in future resource losses, while initial gains result in future resource gains (Hobfoll, 2001). Stress and burnout, according to the COR model; result from risk to resources (risk of PHRC), current resource loss, or inadequate resource gains after investing or losing resources. In summary, COR theory views resource risks (perceived health risks of COVID-19), resource losses, and inadequate resource gains as the primary causes of stress, burnout, and exhaustion (Turner et al., 2014; Valle et al., 2020; Zivnuska et al., 2019), which can leads towards reduced academic performance (resource loss) of the students during COVID-19. Thus, based on the above discussion and COR theory this study proposes that PHRC will affect the emotional exhaustion and academic performance of the students directly as well it affects students’ academic performance through emotional exhaustion. Therefore, propose the following hypotheses:

H1: PHRC will impact emotional exhaustion (H1a) of the students positively as well as students’ academic performance negatively (H1b).

H2: Emotional exhaustion will mediate the relationship between PHRC and students’ academic performance.

The moderating effects of mindfulness and online interaction quality

For nearly a quarter-century, the idea of mindfulness has intrigued academics. According to one popular definition of mindfulness is defined as paying attention to the present moment with a nonjudgmental attitude (Reb et al., 2018; Shireen et al., 2022). Mindfulness is one method in evolving field of mind-body or alternative therapy, which describes an individual’s physical, psychological, and spiritual safety resources (John Lothes et al., 2019; Thimm & Johnsen, 2020). The comprehensive training of mindfulness meditation can help to cultivate and channel these personal resources (Ding et al., 2019; Miyahara et al., 2020). Researchers believe mindfulness to deal with different physical and mental issues is a prevalent alternative health care practice within modern medicalization developments (Emerson et al., 2020). As per COR theory, mindfulness, which is viewed as an individual resource, can have a direct influence on different consequences, change students’ perspectives of study loads, reduce the influence of external health risks on exhaustion, and moderate the association between these risks and outcomes (Kenwright et al., 2021; Van Vu et al., 2022). Many students have had to juggle study with health risks, housework, social connections, and family obligations as a result of COVID-19 (Braun et al., 2019; Colaianne et al., 2020); hence, PHRC is regarded as a type of external risk. To counter the psychological effects of COVID-19 and maintain academic performance, students should focus on their mindfulness. It has been stated in an organizational context that mindfulness can moderate the relationship between a mental and psychological problem with performance outcomes (Van Vu et al., 2022), however, in the context of online learning students and educational settings these effects have been overlooked by the past researchers. Therefore, on the basis of COR theory and evidence from organizational settings this study assumes that mindfulness as an individual resource will moderate the direct impact of PHRC on exhaustion as well as indirect effects on academic performance. Thus, the following hypotheses have been proposed:

H3: The positive relationship between PHRC and emotional exhaustion will be moderated by mindfulness in a way that this link will become weaker at the high level of mindfulness.

H4: Mindfulness will moderate the indirect effects of PHRC on students’ academic performance through emotional exhaustion in a way these indirect effects will become weaker at the high level of mindfulness.

The online interaction quality has been defined as an assessment of how learners perceive that how interactions with other learners allow them to build up their course knowledge and help knowledge sharing (Diep et al., 2019). Recent studies have investigated the role of OIQ in online learning as an online resource support. For example, (Chang & Chuang, 2011) discovered a link between individual participation in online discussions and the OIQ. The authors hypothesized that the more individuals who participated in the online interaction, the better they could encourage and expedite information exchange and collaboration. In this light, it is reasonable to assume that the more students participate in online activities, the higher the quality of online interaction, which may lead to increased feelings of social connectivity and social support. When the OIQ is high, it is more likely to lead to increased social connectivity (Diep et al., 2019) in the form of social support from interaction with other students during COVID-19 (Zheng et al., 2020). The role of OIQ and its impacts on students’ psychological health and academic performance in the context of COVID-19 risk has been overlooked by past researchers. Therefore, by applying COR theory, this study proposes that OIQ as a form of social resource in an online environment can help students to safeguard their psychological resources and academic performance. This study expects that OIQ will reduce the impacts of PHRC on the emotional exhaustion of the students and also its indirect effects on students’ academic performance. Therefore:

H5: The positive relationship between PHRC and emotional exhaustion will be moderated by the OIQ in a way that this link will become weaker at the high level of OIQ.

H6: OIQ will moderate the indirect effects of PHRC on students’ academic performance through emotional exhaustion in a way these indirect effects will become weaker at the high level of OIQ.

Research methodology

Participants and procedure

Graduate and postgraduate students from various universities in Pakistan’s megacities make up the study’s sample. Pakistan was chosen as the study location for the COVID-19 pandemic because it is located in an under-investigated terrestrial region. The research was administered from April to August 2021, during the apex of the COVID-19 pandemic. Because it was hard to make physical interaction with students during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study gathered information from the sample population online by utilizing a simple random sampling technique. The language of the questionnaires was English, and students were assured of the secrecy of their responses before taking informed consent from participants. Those participants who were under 18 years old were asked to take permission from their guardian before taking part into the survey. The participation of this study was voluntary and respondents were told that they can dropout at any stage of the study. The survey was distributed through different social media sites (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn) and students were asked to share the survey link to their classmates as well to increase their participation in the study.

Three-time lag research was conducted, with two months of temporal separation between each lag. Time lag design has been utilized by several recently published studies (for readings see; Khan, 2021a; Lavelle et al., 2019; Lebel et al., 2022; Mehmood et al., 2022) This was decided based on Podsakoff et al.’s (2003) suggestions using a temporally separated study design to avoid social desirability and common method bias (CMB), which can take place when all research measurements are made at the same time using the same criterion. At time one (T-1, in April), respondents were asked about their demographics, PHRC, OIQ, and mindfulness; at time two (T-2, in June), they were asked about their emotional exhaustion; and at time three (T-3, in August), they were asked about their academic performance. Students’ email IDs were retrieved each time they returned the survey in order to match T-1, T-2, and T-3 answers, and only responses from those who took part in all three times were retained.

At T1–1, 650 participants were approached and asked to respond to the questionnaires that included demographic characteristics, a predictor variable, and moderating variables; 514 students responded. Participants who responded at T-1 were approached again two months later to respond to the mediating variable. T-2 responses came from 436 students out of 514 T-1 survey participants. Respondents who engaged in T-2 were contacted and asked about their performance after another two-month gap, and 356 participants responded. With a response rate of 51.70%, 336 responses were used to validate the hypotheses after careful data screening and deletion of incomplete data. As respondents were dropout in the different waves of the data collection this could be problematic. Therefore, the non-response bias test was carried out in accordance with the given criteria by Armstrong and Overton (1977). The first and last wave participants’ responses were analyzed for the chi-square test and independent t-test. There was no discernible difference in the outcomes. This demonstrates that non-response bias was not a big issue in this research. The study included 161 males and 175 females, according to demographic data. Rendering to the survey participants 154 students were enrolled in an undergraduate degree program, and 182 students were registered in a graduate/post-graduate degree program. The age range of the participating students was 16–22 years old with an average age of 19.57 (SD = 1.76) years (for details see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

| Constructs | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gendera T1 | 0.48 | 0.50 | – | |||||||

| 2. Education Levelb T1 | 1.54 | .50 | .12* | |||||||

| 3. Agec T1 | 19.57 | 1.76 | .05 | .15* | ||||||

| 4. PHRC T1 | 2.62 | 1.21 | .15* | −.01 | .02 | |||||

| 5. Mindfulness T1 | 3.34 | 0.96 | −.01 | −.10 | .01 | −.56*** | ||||

| 6. Online interaction quality T1 | 3.23 | 1.10 | −.06 | −.08 | −.04 | −.31** | .58*** | |||

| 7. Emotional exhaustion T2 | 2.54 | 1.15 | .03 | .01 | .15* | −.51*** | −.47*** | −.44*** | ||

| 8. GPA T3 | 3.17 | 0.79 | −.01 | −.02 | −.15* | −.47*** | .60*** | .54*** | −.53*** | – |

(a) gender was coded as female = 0, male = 1; (b) education level was coded as undergraduate students = 1, graduate/post-graduate students = 2; (c) age was in years; (1) T = time; (2) PHRC = Perceived health risks of COVID-19; (3)*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Measurement

All variables were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1-strongly disagreed to 5-strongly agreed, unless otherwise indicated.

Perceived health risks of COVID-19

To measure PHRC this study used a six items scale adapted from past studies (Lau et al., 2007; Van Vu et al., 2022). This scale showed acceptable reliability (α = 0.87). One sample item was “In general, I know that COVID-19 is highly dangerous.”

Mindfulness

This study used a unidimensional scale over a multidimensional one because this study isn’t distinguishing between different dimensions of mindfulness. This study used the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), a psychometrically sound instrument (Brown & Ryan, 2003) because it is the most well-known and widely used of the scales (α = 0.95). On a 6-point scale, 1 = almost always, 6 = almost never, the fifteen items were evaluated. A sample item was “I get so focused on the goal I want to achieve that I lose touch with what I’m doing right now to get there.”

Online interaction quality

This study used (Arbaugh et al., 2008) 12-item Cognitive Presence Scale to assess the quality of online interactions. This study made small modifications to the scale item in light of the COVID-19 pandemic which showed adequate reliability (α = 0.93). “During the COVID-19 pandemic, online interaction with other classmates is valuable in helping me appreciate different perspectives” was an example item.

Emotional exhaustion

The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey’s emotional exhaustion subscale was used to assess the students’ emotional exhaustion (Schaufeli et al., 2002). This subscale has five items (for example, “During the COVID-19 pandemic I feel exhausted at the end of an online class”). This scale had good internal consistency in the current samples (α = 0.85).

Academic performance

The students were required to report their last semester’s grade point average (GPA). They reported their GPAs ranging from 1 (minimum) to 4 (maximum), a higher GPA means good academic performance in the previous semester. It’s possible that the GPA reflected recent academic performance. Examining student PHRC and exhaustion scores in relation to GPAs could reveal whether there is a link between PHRC and exhaustion and student performance, comparable to the well-established link between work exhaustion and work performance.

Analysis and results

Measurement model

The data were analyzed with the help of the SPSS 24, Amos 24, and Process Macro packages were used, and the structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was applied. Table 1 showed the demographic details, means, standard deviation, and correlation among study constructs. The directions of the hypothesized relationships were accordingly to their expected directions. Because the data was gathered through a self-reported survey, artifacts covariance between measurements could have resulted in misunderstanding and factually incorrect findings (Wu et al., 2022). This study utilized Harman’s single-factor technique to check the constructs in this research and discovered that the first common factor explained 38.68% of the variance, which was less than 50%, suggesting that the CMB was unlikely to have a significant impact on the findings (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Furthermore, this study examined construct correlation coefficients, and all of the correlations were less than 0.90, indicating that the study results were unlikely to be affected by CMB (Wu et al., 2022).

This study checked measurements for convergent and discriminant validity. The average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) of each construct were both above the acceptable value (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), and factor loading for each item was greater than 0.60 suggesting acceptable convergent validity (see Table 2). The Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio was also used to evaluate discriminant validity; all of the values were under 0.85, suggesting adequate discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015). This study also looked at the variance inflation factor (VIF) to see if it could help with multicollinearity issues. The VIF varied from 1.05 to 1.47, which was lower than the maximum of 5 (Xiongfei et al., 2020), suggesting that the model was reliable. The model was then put to the test using data obtained by the validated instruments. The overall fit indices for the proposed model were evaluated utilizing AMOS 24. The results were within acceptable limits. The SRMR and RMSEA were both 0.042 and 0.046, respectively, which were lower than the recognized value of 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). If the chi-squared per degree of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF) is between 2 and 3, the model fits well (Carmines & McIver, 1981). The CMIN/DF ratio was 1.705, which was within acceptable limits. In addition, the IFI was 0.940, the TLI was 0.935, and the CFI was 0.939, all of which were higher than the agreed limit of 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Table 2.

Factors loadings, composite reliability, and AVE

| Constructs | Items | Loading | CR | AVE | Constructs | Items | Loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived health risks of COVID-19 (PHRC) | PHRC1 | 0.793 | 0.869 | 0.527 | Emotional exhaustion (EE) | EE1 | 0.710 | 0.855 | 0.544 |

| PHRC2 | 0.637 | EE2 | 0.815 | ||||||

| PHRC3 | 0.671 | EE3 | 0.641 | ||||||

| PHRC4 | 0.791 | EE4 | 0.791 | ||||||

| PHRC5 | 0.732 | EE5 | 0.716 | ||||||

| PHRC6 | 0.720 | Mindfulness (MF) | MF1 | 0.777 | 0.946 | 0.541 | |||

| Online interaction quality (OIQ) | OIQ1 | 0.743 | 0.935 | 0.546 | MF2 | 0.721 | |||

| OIQ2 | 0.682 | MF3 | 0.764 | ||||||

| OIQ3 | 0.697 | MF4 | 0.769 | ||||||

| OIQ4 | 0.708 | MF5 | 0.837 | ||||||

| OIQ5 | 0.736 | MF6 | 0.705 | ||||||

| OIQ6 | 0.745 | MF7 | 0.698 | ||||||

| OIQ7 | 0.683 | MF8 | 0.669 | ||||||

| OIQ8 | 0.715 | MF9 | 0.778 | ||||||

| OIQ9 | 0.661 | MF10 | 0.712 | ||||||

| OIQ10 | 0.854 | MF11 | 0.690 | ||||||

| OIQ11 | 0.792 | MF12 | 0.722 | ||||||

| OIQ12 | 0.828 | MF13 | 0.722 | ||||||

| MF14 | 0.698 | ||||||||

| MF15 | 0.752 |

CR Composite reliability, AVE Average variance extracted. All factor loadings are significant at the p < 0.001 level

Structural model and testing of hypotheses

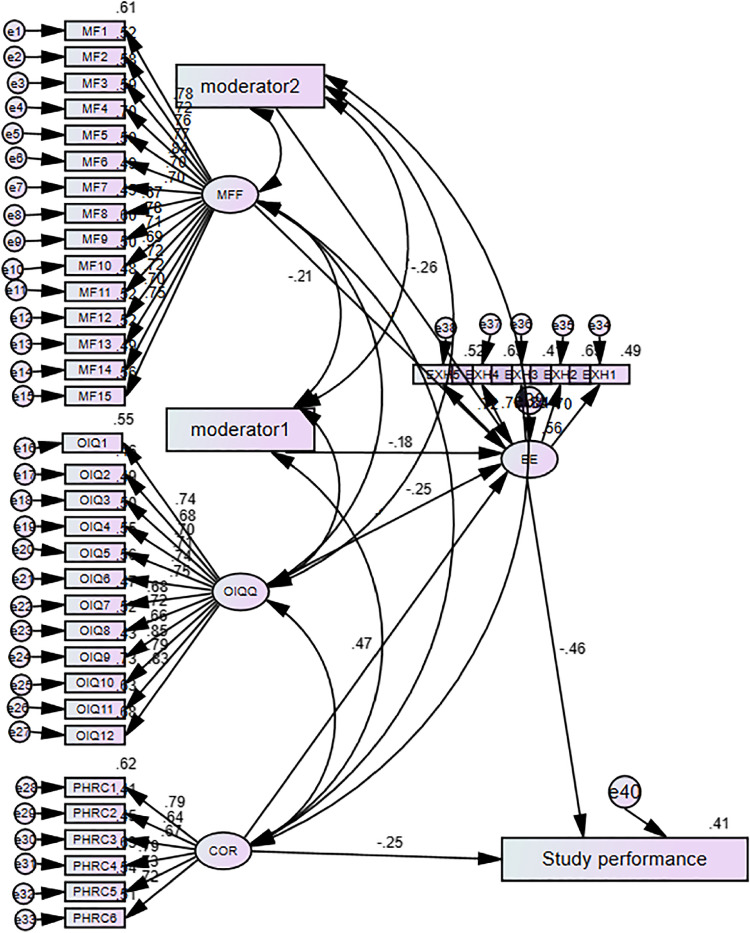

The structural model’s overall fit indices were acceptable because the results were broadly within the accepted range. The value of CMIN/DF was 1.813, RMSEA was 0.049, IFI was 0.925, TLI was 0.919, and CFI was 0.925. This study calculated the path analysis because the results of the study showed an acceptable model fit.

Table 3 summarizes the findings of the hypotheses. The majority of the hypotheses were statistically significant at p < 0.001, indicating that the constructs were strongly linked. The PHRC-related hypotheses were confirmed and supported, with PHRC having a significant effect on emotional exhaustion (β = 0.47, p < 0.001) and academic performance (β = −0.25, p < 0.01), results supporting H1a and H1b. Moreover, in order to examine indirect effects in mediation models, this study utilized bootstrapping with 5000 bootstrap replicates. A significant indirect effect is indicated by confidence intervals (CIs) that do not consist of zero. The results revealed that indirect effects of the PHRC on student academic performance via emotional exhaustion were significant (indirect effects = −0.20; low level of CIs = −0.265, high level of CIs = −0.141). As CIs doesn’t include zero, therefore, H2 was also supported (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Hypotheses testing results

| β | Supported | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived health risks of COVID-19 (PHRC) → Emotional exhaustion (H1a) | .47*** | Yes | ||

| PHRC → Academic performance (H1b) | −.25** | Yes | ||

| Emotional exhaustion → Academic performance | −.46*** | |||

| Moderating effects | ||||

| Mindfulness → Emotional exhaustion | −.21** | |||

| PHRCxMindfulness → Emotional exhaustion (H3) | −.18* | Yes | ||

| Online interaction quality (OIQ) → Emotional exhaustion | −.25** | |||

| PHRCxOIQ→ Emotional exhaustion (H5) | −.26** | Yes | ||

| Mediating effects | ||||

| Indirect effects | β | LLCI | ULCI | Yes |

| PHRC→ Emotional exhaustion→ Academic performance (H2) | −.20 | −0.265 | −0.141 | |

N = 336; LLCI lower level of the 95% confidence interval, ULCI upper level of the 95% confidence interval; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

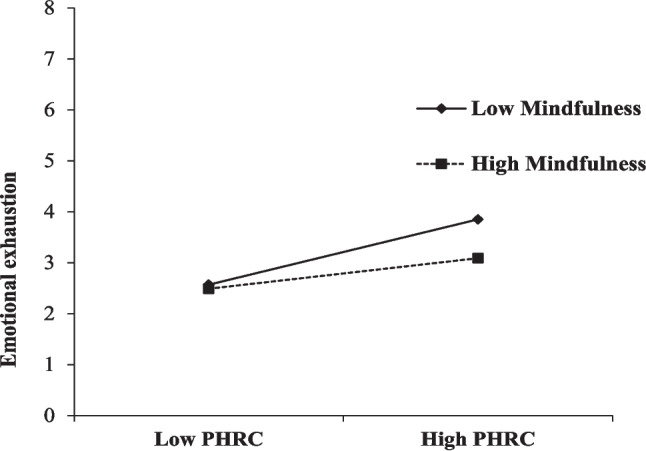

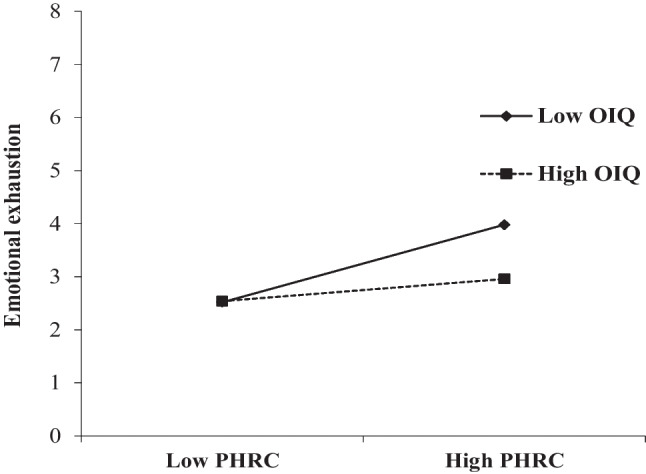

This study tested moderating effects of mindfulness and OIQ in the positive association between PHRC and emotional exhaustion. To avoid multicollinearity issues between the interaction term and its components, the main effect variables were centered and standardized before the creation of interaction terms. The results in Table 3 (also presented in appendix section) showed that the interaction term between PHRC and mindfulness on emotional exhaustion was significant (β = −0.18, p < 0.05). This study further explained moderating effects in Fig. 2, as shown in Fig. 2 the positive relationship between PHRC and emotional exhaustion was weaker when mindfulness was higher (β = 0.30, p < 0.05) as compared to when mindfulness was low (β = 0.64, p < 0.001), supporting H3 as well. Similarly, H5 states that the positive relationship between PHRC and emotional exhaustion will be weaker at the high level of OIQ. Results in Table 3 supported this claim as interaction term was significant (β = −0.26, p < 0.01), thus supporting H5. This study further explains this in Fig. 3 where results showed that at the high level of OIQ the positive relationship between PHRC and emotional exhaustion was weaker and become non-significant (β = 0.21, p > 0.05) as compared to when OIQ was low (β = 0.73, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Interaction effects of PHRC and mindfulness on emotional exhaustion

Fig. 3.

Interaction effects of PHRC and online interaction quality on emotional exhaustion

This study used (Hayes, 2017) PROCESS Model 7 to test moderated-mediation hypotheses. The bootstrap approximation of the index of moderated-mediation was significant for H4 as well as for H6, as the 95% CIs for the index did not comprised zero (Index = −0.057, S.E. =0.015; low level of CIs = −0.030, high level of CIs = −0.090) for mindfulness and (Index = −0.059, S.E. =0.014; low level of CIs = −0.034, high level of CIs = −0.091) for OIQ. The detailed results at the different levels of moderators are shown in Table 4. These results stated that both, H4 and H6 were supported.

Table 4.

Bootstrap results for conditional indirect effects of perceived health risks of COVID−19 through emotional exhaustion on academic performance at the levels of two moderating variables

| Mindfulness | Boot indirect effects | Boot SE | Boot Lower limit 95% CI | Boot Upper limit 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | ||||

| -1 SD | −0.146 | 0.027 | −0.206 | −0.100 |

| Mean | −0.092 | 0.020 | −0.136 | −0.059 |

| +1 SD | −0.038 | 0.022 | −0.083 | 0.002 |

| Index of Moderated Mediation | ||||

| (H4) | −0.057 | 0.015 | −0.030 | −0.090 |

| Online interaction quality | ||||

| Emotional Exhaustion | ||||

| −1 SD | −0.161 | 0.027 | −0.220 | −0.113 |

| Mean | −0.096 | 0.019 | −0.140 | −0.064 |

| +1 SD | −0.032 | 0.022 | −0.078 | 0.007 |

| Index of Moderated Mediation | ||||

| (H6) | −0.059 | 0.014 | −0.034 | −0.091 |

CI Confidence Interval; Bootstrap sample size = 5000

Discussion

The overall model was supported by the data and all hypotheses were validated. In educational settings, the effects of health-related risk of COVID-19 and its effects on students’ emotional exhaustion and academic performance have been overlooked by academic researchers. This study also examined the moderating effects of mindfulness and OIQ as students’ internal and external resources to safeguard them from these health-related risks of COVID-19. By examining these relationships this study contributed to literature and also provided some recommendations to policy-makers, educational institutions, and students.

Theoretical implications

The findings of the current study have several theoretical ramifications. First, in the context of COVID-19, the current article adds to our understanding of the impact of students’ insights of health threats on their mental health and performance. COVID-19 is a unique stressor with a wide range of implications that impacts people as a whole; it is not merely a medical problem. COVID-19 is unpredictably unexpected, leaving students with a sense of terror and anxiety (Co et al., 2021; Lohani et al., 2022). This study adds to the existing works by focusing on COVID-19 as an explicit stressor in a complex setting, which sets it apart from other high-risk studies (Gever et al., 2021; Van Vu et al., 2022). From an educational standpoint, the current study’s theoretical findings can thus be applied to future crises of a similar nature. Second, while earlier researches have used the COR theory in more typical settings (Carlson et al., 2012; Khan & Khan, 2021; Toker et al., 2015), this article utilizes it to examine the impact of an environmental stressor (i.e., PHRC) and personal and external resources (i.e., mindfulness and OIQ) on students mental health and academic performance during COVID-19’s global health adversity. This study shows that, unlike “normal” high-risk contexts, the COVID-19 epidemic is a unique setting that triggers not only stressors but also the danger of the virus for one-self, classmates, and family, as well as community concerns, as outlined in COR’s theoretical lenses. As a result, the current study adds to the educational literature by demonstrating the COR theory’s potential application in times of health emergency, not during normal circumstances.

Third, this scholarship provides a better knowledge of the effect of students’ perceptions of health risks linked with a virus on their mental and academic consequences. The findings revealed that students’ PHRC has a positive impact on exhaustion, which has a negative impact on academic performance. Exhaustion, in other words, acts as a mediating factor between PHRC and academic performance. The indirect effect of PHRC on academic performance via exhaustion is negative because when students are exposed to extreme stress as an outcome of PHRC, they lose their strength and become overtired, lowering their academic performance. This is clarified by the COR theory, which states that when people perceive COVID-19’s risks and threats, their resources are depleted, resulting in exhaustion (Van Vu et al., 2022) and lower performance.

Finally, this research adds to our understanding of how mindfulness and OIQ play a role in the direct and indirect associations between students’ PHRC, exhaustion, and academic performance. According to the findings, the direct positive effect of PHRC on student exhaustion and the indirect effect of PHRC on academic performance through exhaustion are both moderated by mindfulness and OIQ. These findings add to the evidence that mindfulness and OIQ play a role in reducing the significant influence of students’ perceived health risks on exhaustion. It also contributes to a better understanding of how mindfulness and OIQ, as personal and external resources, moderate the influence of students’ PHRC on their academic performance via exhaustion when using the COR theory. This study contributed to extenuating the influence of COVID-19 and other international crises on students’ exhaustion and academic performance from a theoretical standpoint.

Practical implications

Students’ PHRC has a positive impact on exhaustion, but it has a negative effect on academic performance due to exhaustion. Exhaustion, in other words, acts as a deleterious mediator between PHRC and academic performance. Furthermore, mindfulness and OIQ can improve student performance by decreasing exhaustion. Teachers and parents must assist students in curbing exhaustion during COVID-19. To decrease exhaustion and maintain academic performance, educational institutions can motivate students to practice mindfulness. They can teach students about the importance of mindfulness and teach them how to practice mindfulness meditation like body scan, mindful movement, walking mindfulness, and sitting mindfulness (Vinci et al., 2014). As students experience adverse situations and widespread global death during the pandemic, being mindful allows students to adjust to stressful conditions and minimizes the positive impact of PHRC on exhaustion. Academic institutions should emphasize prioritization to help students focus on important tasks. Universities can teach students about the challenges they will face in order to prevent the pandemic from expanding. During a crisis, academic institutions should assist students in accepting the “new normal” without judging or critiquing them. Universities could, for example, host online training on resilience and meditation, promote healthy lifestyles, or create online contests to help students avoid exhaustion.

When physical contact is constrained due to the COVID-19 pandemic, students’ only option is to use internet services to improve their academic social interactions (Zheng et al., 2020). According to the findings of this study, the quality of virtual interactions can help students improve their academic performance and reduce exhaustion. It is worth remembering that, while both mindfulness and OIQ can help with exhaustion and student performance, mindfulness, in comparison to OIQ, is particularly important and should be given preferential treatment in the COVID-19 setting. Although OIQ would reduce the effect of PHRC on exhaustion, if it is implemented incorrectly, it can lead to information overload, which can lead to psychological health issues (Swar et al., 2017).

Limitations and future research

Despite its benefits, this research has some limitations. First, using a cross-sectional design precludes establishing causal associations between variables. Longitudinal and experimental investigations are strongly advised in order to uncover the causal mechanism by which PHRC and emotional exhaustion influence academic performance. Second, the data from this study were collected from Pakistani universities; therefore, due to cultural differences, the findings of the current study may have limited applicability in other cultures. Thus, it is suggested to future researchers conduct a similar study by undertaking cultural variables in other countries. Third, this study investigated only one mental health-related consequence (emotional exhaustion) of PHRC. Several studies have investigated different mental issues of COVID-19 (Keyserlingk et al., 2021; Khan, 2021b; Pang, 2021), therefore, future research on other mechanisms affecting students’ mental health and performance is needed. Furthermore, as depression, anxiety, and psychological distress are the outcome of COVID-19 and these are the inhibitors of suicidal intentions (Serafini et al., 2014), therefore, future studies can also consider suicidal intentions as an outcome variable of PHRC. Finally, this study applied COR theory to test the hypothesized relationships, future studies are recommended to test similar relationships through the lenses of other theories.

Conclusion

This study investigated how students’ perceptions of health risks of COVID-19 affect their mental health and academic performance. Furthermore, moderating effects of OIQ and mindfulness were also tested. Findings revealed that PHRC enhances exhaustion and affects severely academic performance. However, OIQ and mindfulness not only attenuated the direct effects of PHRC on exhaustion but also indirect impacts on students’ academic performance. The findings of the study assisted educational institutions, parents, and policymakers to work on improving the quality of online interactions while students are studying online and also organized sessions for the students to improve their mental strengths in the form of mindfulness.

Appendix

Data availability

Data for this study can be attained on the request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was taken from the ethical committee of participating organizations.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

No material was taken from other sources which need permission to publish.

Competing interests

All authors of this study declare that they have no conflict of interest. None of the authors is financially or non-financially involve with the organizations being studied in this article.

Clinical trial registration

N/A

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abram MD, Jacobowitz W. Resilience and burnout in healthcare students and inpatient psychiatric nurses: A between-groups study of two populations. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2021;35(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar F, Akhtar S. Erratum to: Relationship of LMX and agreeableness with emotional exhaustion: A mediated moderated model. Current Psychology. 2017;38(1):228–228. doi: 10.1007/S12144-017-9606-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Khan AN, Khan MM, Butt AS, Shah SHH. Mindfulness and study engagement: Mediating role of psychological capital and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Professional Capital and Community. 2021;7(2):144–158. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-02-2021-0013/FULL/XML. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arbaugh JB, Cleveland-Innes M, Diaz SR, Garrison DR, Ice P, Richardson JC, Swan KP. Developing a community of inquiry instrument: Testing a measure of the community of inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. The Internet and Higher Education. 2008;11(3–4):133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JS, Overton TS. Estimating nonresponse Bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research. 1977;14(3):396. doi: 10.2307/3150783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atlam ES, Ewis A, El-Raouf MMA, Ghoneim O, Gad I. A new approach in identifying the psychological impact of COVID-19 on university student’s academic performance. Alexandria Engineering Journal. 2022;61(7):5223–5233. doi: 10.1016/J.AEJ.2021.10.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bano S, Cisheng W, Khan AN, Khan NA. WhatsApp use and student’s psychological well-being: Role of social capital and social integration. Children and Youth Services Review. 2019;103(8):200–208. doi: 10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2019.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinsoli ML, di Riso D, Napier JL, Moretti L, Bettinsoli P, Delmedico M, Piazzolla A, Moretti B. Mental health conditions of Italian healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 disease outbreak. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2020;12(4):1054–1073. doi: 10.1111/APHW.12239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun SS, Roeser RW, Mashburn AJ, Skinner E. Middle school teachers’ mindfulness, occupational health and well-being, and the quality of teacher-student interactions. Mindfulness. 2019;10(2):245–255. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-0968-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(4):822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson D, Ferguson M, Hunter E, Whitten D. Abusive supervision and work-family conflict: The path through emotional labor and burnout. Leadership Quarterly. 2012;23(5):849–859. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmines, E. G., & McIver, J. P. (1981). Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In G. W. Bohrnstedt & E. F. Borgatta (Eds.), Social measurement: Current issues (pp. 65–115). Sage Publications Inc.

- Chang HH, Chuang SS. Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Information & Management. 2011;48(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/J.IM.2010.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claassen L, Henneman L, de Vet R, Knol D, Marteau T, Timmermans D. Fatalistic responses to different types of genetic risk information: Exploring the role of self-malleability. Psychology & Health. 2009;25(2):183–196. doi: 10.1080/08870440802460434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AE, Nong H, Zhu H, Zhu R. Compensating for academic loss: Online learning and student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Economic Review. 2021;68:101629. doi: 10.1016/J.CHIECO.2021.101629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Co M, Ho MK, Bharwani AA, Yan Chan VH, Yi Chan EH, Poon KS. Cross-sectional case-control study on medical students’ psychosocial stress during COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong. Heliyon. 2021;7(11):e08486. doi: 10.1016/J.HELIYON.2021.E08486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaianne BA, Galla BM, Roeser RW. Perceptions of mindful teaching are associated with longitudinal change in adolescents’ mindfulness and compassion. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2020;44(1):41–50. doi: 10.1177/0165025419870864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curșeu, P. L., Coman, A. D., Panchenko, A., Fodor, O. C., & Rațiu, L. (2021). Death anxiety, death reflection and interpersonal communication as predictors of social distance towards people infected with COVID 19. Current Psychology, 1–14. 10.1007/S12144-020-01171-8/TABLES/8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Day AL, Sibley A, Scott N, Tallon JM, Ackroyd-Stolarz S. Workplace risks and stressors as predictors of burnout: The moderating impact of job control and team efficacy. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de l’Administration. 2009;26(1):7–22. doi: 10.1002/CJAS.91. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diep AN, Zhu C, Cocquyt C, De Greef M, Vanwing T. Adult learners’ social connectedness and online participation: The importance of online interaction quality. Studies in Continuing Education. 2019;41(3):326–346. doi: 10.1080/0158037X.2018.1518899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Du J, Zhou Y, An Y, Xu W, Zhang N. State mindfulness, rumination, and emotions in daily life: An ambulatory assessment study. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2019;22(4):369–377. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson L-M, de Diaz NN, Sherwood A, Waters A, Farrell L. Mindfulness interventions in schools: Integrity and feasibility of implementation. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2020;44(1):62–75. doi: 10.1177/0165025419866906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterwalder J, Kabadayi S, Fisk RP, Boenigk S. Creating hospitable service systems for refugees during a pandemic: Leveraging resources for service inclusion. Journal of Service Theory and Practice. 2020;31(2):247–263. doi: 10.1108/JSTP-07-2020-0175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(3):382–388. doi: 10.2307/3150980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gever VC, Talabi FO, Adelabu O, Sanusi BO, Talabi JM. Modeling predictors of COVID-19 health behaviour adoption, sustenance and discontinuation among social media users in Nigeria. Telematics and Informatics. 2021;60:101584. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2021.101584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K. How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;37:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben JRB, Buckley MR. Burnout in organizational life. Journal of Management. 2004;30(6):859–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (Methodology in the Social Sciences) (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2015;43(1):115–135. doi: 10.1007/S11747-014-0403-8/FIGURES/8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44(3):513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology. 2001;50(3):337–421. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hochwarter WA, Ferris GR, Zinko R, Arnell B, James M. Reputation as a moderator of political behavior-work outcomes relationships: A two-study investigation with convergent results. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92(2):567–576. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Pradas S, Hernández-García Á, Chaparro-Peláez J, Prieto JL. Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Computers in Human Behavior. 2021;119:106713. doi: 10.1016/J.CHB.2021.106713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito JK, Brotheridge CM. Resources, coping strategies, and emotional exhaustion: A conservation of resources perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2003;63(3):490–509. doi: 10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00033-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeftić A, Ikizer G, Tuominen J, Chrona S, Kumaga R. Correction to: Connection between the COVID-19 pandemic, war trauma reminders, perceived stress, loneliness, and PTSD in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Current Psychology. 2022;2022(1):1–1. doi: 10.1007/S12144-022-02876-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John Lothes I, Mochrie K, Wilson M, Hakan R. The effect of dbt-informed mindfulness skills (what and how skills) and mindfulness-based stress reduction practices on test anxiety in college students: A mixed design study. Current Psychology. 2019;40(6):2764–2777. doi: 10.1007/S12144-019-00207-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenwright, D., McLaughlin, T., & Hansen, S. (2021). Teachers’ perspectives about mindfulness programmes in primary schools to support wellbeing and positive behaviour. International Journal of Inclusive Education.10.1080/13603116.2020.1867382

- Keyserlingk, L., Yamaguchi-Pedroza, K., Arum, R., & Eccles, J. S. (2021). Stress of university students before and after campus closure in response to COVID-19. Journal of Community Psychology, jcop.22561. 10.1002/jcop.22561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Khalafallah AM, Jimenez AE, Lam S, Gami A, Dornbos DL, Sivakumar W, Johnson JN, Mukherjee D. Burnout among medical students interested in neurosurgery during the COVID-19 era. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2021;210:106958. doi: 10.1016/J.CLINEURO.2021.106958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. N. (2021a). Misinformation and work - related outcomes of healthcare community : Sequential mediation role of COVID - 19 threat and psychological distress. Journal of Community Psychology. 10.1002/jcop.22693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Khan AN. A diary study of psychological effects of misinformation and COVID-19 threat on work engagement of working from home employees. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2021;171:120968. doi: 10.1016/J.TECHFORE.2021.120968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. N. (2022). Is green leadership associated with employees’ green behavior? Role of green human resource management. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 1–21. 10.1080/09640568.2022.2049595

- Khan, A. N., Khan, N. A., & Mehmood, K. (2022a). Exploring the relationship between learner proactivity and social capital via online learner interaction: Role of perceived peer support. Behaviour & Information Technology.10.1080/0144929X.2022.2099974

- Khan AN, Moin MF, Khan NA, Zhang C. A multistudy analysis of abusive supervision and social network service addiction on employee’s job engagement and innovative work behaviour. Creativity and Innovation Management. 2022;31(1):77–92. doi: 10.1111/CAIM.12481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N. A., Hui, Z., Khan, A. N., & Soomro, M. A. (2021). Impact of women authentic leadership on their own mental wellbeing through ego depletion: Moderating role of leader’s sense of belongingness. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management.10.1108/ECAM-02-2021-0143/FULL/XML

- Khan NA, Khan AN. Exploring the impact of abusive supervision on employee'voice behavior in Chinese construction industry: a moderated mediation analysis. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. 2022;29(8):3051–3071. doi: 10.1108/ECAM-10-2020-0829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N. A., Khan, A. N., Moin, M. F., & Pitafi, A. H. (2020). A trail of chaos: How psychopathic leadership influence employee satisfaction and turnover intention via self-efficacy in tourism enterprises. Journal of Leisure Research, 1–23. 10.1080/00222216.2020.1785359.

- Langer, E. J. (1989). Mindfulness. In Mindfulness. Addison-Wesley/Addison Wesley Longman.

- Lau JTF, Kim JH, Tsui H, Griffiths S. Anticipated and current preventive behaviors in response to an anticipated human-to-human H5N1 epidemic in the Hong Kong Chinese general population. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2007;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-18/TABLES/5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle, J. J., Rupp, D. E., Herda, D. N., Pandey, A., & Lauck, J. R. (2019). Customer injustice and employee performance: Roles of emotional exhaustion, surface acting, and emotional demands–abilities fit. Journal of Management, XX(X), 1–29. 10.1177/0149206319869426

- Lebel, R. D., Yang, X., Parker, S. K., & Kamran-Morley, D. (2022). What makes you proactive can burn you out: The downside of proactive skill building motivated by financial precarity and fear. Journal of Applied Psychology.10.1037/APL0001063 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li, W., & Khan, A. N. (2022). Investigating the impacts of information overload on psychological well-being of healthcare professionals: Role of COVID-19 stressor. Inquiry : A Journal of Medical Care Organization, Provision and Financing, 59. 10.1177/00469580221109677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lin C-Y, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH, Se AP. Psychometric properties of the fear of COVID-19 scale: A response to de Medeiros et al. “psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S)”. Current Psychology. 2022;2022(1):1–2. doi: 10.1007/S12144-021-02686-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohani, M., Dutton, S., & Elsey, J. S. (2022). A day in the life of a college student during the COVID-19 pandemic: An experience sampling approach to emotion regulation. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being.10.1111/APHW.12337 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie CS, Poulin PA, Seidman-Carlson R. A brief mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention for nurses and nurse aides. Applied Nursing Research. 2006;19(2):105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdy, M. A. A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the academic performance of veterinary medical students. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 0, 732. 10.3389/FVETS.2020.594261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCarthy JM, Truxillo DM, Bauer TN, Erdogan B, Shao Y, Wang M, Liff J, Gardner C. Distressed and distracted by COVID-19 during high-stakes virtual interviews: The role of job interview anxiety on performance and reactions. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2021;106(8):1103. doi: 10.1037/APL0000943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, K., Jabeen, F., Iftikhar, Y., Yan, M., Khan, A. N., AlNahyan, M. T., Alkindi, H. A., & Alhammadi, B. A. (2022). Elucidating the effects of organisational practices on innovative work behavior in UAE public sector organisations: The mediating role of employees’ wellbeing. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 10.1111/APHW.12343 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miyahara, M., Wilson, R., Pocock, T., Kano, T., & Fukuhara, H. (2020). How does brief guided mindfulness meditation enhance empathic concern in novice meditators?: A pilot test of the suggestion hypothesis vs. the mindfulness hypothesis. Current Psychology, 1–12. 10.1007/S12144-020-00881-3/TABLES/4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ouweneel E, Le Blanc PM, Schaufeli WB. Flourishing students: A longitudinal study on positive emotions, personal resources, and study engagement. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2011;6(2):142–153. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2011.558847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. How compulsive WeChat use and information overload affect social media fatigue and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic? A stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Telematics and Informatics. 2021;64:101690. doi: 10.1016/J.TELE.2021.101690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser D, Johnson S, Kuipers E, Szmukler G, Bebbington P, Thornicroft G. Perceived sources of work stress and satisfaction among hospital and community mental health staff, and their relation to mental health, burnout and job satisfaction. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1997;43(2):51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reb, J., Chaturvedi, S., Narayanan, J., & Kudesia, R. S. (2018). Leader mindfulness and employee performance: A sequential mediation model of LMX quality, interpersonal justice, and employee stress. Journal of Business Ethics, 0(0), 1–19. 10.1007/s10551-018-3927-x

- Roche M, Haar JM, Luthans F. The role of mindfulness and psychological capital on the well-being of leaders. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2014;19(4):476–489. doi: 10.1037/a0037183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safi’i A, Muttaqin I, Sukino, Hamzah N, Chotimah C, Junaris I, Rifa’i MK. The effect of the adversity quotient on student performance, student learning autonomy and student achievement in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Evidence from Indonesia. Heliyon. 2021;7(12):e08510. doi: 10.1016/J.HELIYON.2021.E08510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli WB, Martínez IM, Pinto AM, Salanova M, Bakker AB. Burnout and engagement in university students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2002;33(5):464–481. doi: 10.1177/0022022102033005003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini G, Pompili M, Borgwardt S, Houenou J, Geoffroy PA, Jardri R, Girardi P, Amore M. Brain changes in early-onset bipolar and unipolar depressive disorders: A systematic review in children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;23(11):1023–1041. doi: 10.1007/S00787-014-0614-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shireen H, Siemers N, Dor-Ziderman Y, Knäuper B, Moodley R. Treating others as we treat ourselves: A qualitative study of the influence of psychotherapists’ mindfulness meditation practice on their psychotherapeutic work. Current Psychology. 2022;2021:1–15. doi: 10.1007/S12144-021-02565-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GD, Ng F, Li WHC. COVID-19: Emerging compassion, courage and resilience in the face of misinformation and adversity. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(9–10):1425–1428. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano P, Ustulin M, Pizzorno E, Vichi M, Pompili M, Serafini G, Amore M. A Google-based approach for monitoring suicide risk. Psychiatry Research. 2016;246:581–586. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2016.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swar B, Hameed T, Reychav I. Information overload, psychological ill-being, and behavioral intention to continue online healthcare information search. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;70:416–425. doi: 10.1016/J.CHB.2016.12.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thimm JC, Johnsen TJ. Time trends in the effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2020;61(4):582–591. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toker S, Laurence GA, Fried Y. Fear of terror and increased job burnout over time: Examining the mediating role of insomnia and the moderating role of work support. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2015;36(2):272–291. doi: 10.1002/job.1980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner N, Hershcovis MS, Reich TC, Totterdell P. Work-family interference, psychological distress, and workplace injuries. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2014;87(4):715–732. doi: 10.1111/joop.12071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valle, M., Carlson, D. S., Carlson, J. R., Zivnuska, S., Harris, K. J., & Harris, R. B. (2020). Technology-enacted abusive supervision and its effect on work and family. Journal of Social Psychology.10.1080/00224545.2020.1816885 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vinci C, Peltier MR, Shah S, Kinsaul J, Waldo K, McVay MA, Copeland AL. Effects of a brief mindfulness intervention on negative affect and urge to drink among college student drinkers. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;59:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard N, Benros ME. Brain, behavior, and immunity. Academic Press Inc.; 2020. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence; pp. 531–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vu, T., Vo-Thanh, T., Chi, H., Nguyen, N. P., Van Nguyen, D., & Zaman, M. (2022). The role of perceived workplace safety practices and mindfulness in maintaining calm in employees during times of crisis. Human Resource Management.10.1002/HRM.22101

- Wincent J, Örtqvist D. A comprehensive model of entrepreneur role stress antecedents and consequences. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2009;24(2):225–243. doi: 10.1007/s10869-009-9102-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Zhou Y, Wang R, Huang S, Yuan Q. Understanding the mechanism between IT identity, IT mindfulness and Mobile health technology continuance intention: An extended expectation confirmation model. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2022;176:121449. doi: 10.1016/J.TECHFORE.2021.121449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiongfei C, Khan AN, Ali A, Khan NA. Consequences of cyberbullying and social overload while using SNSs: A study of users’ discontinuous usage behavior in SNSs. Information Systems Frontiers. 2020;22(6):1343–1356. doi: 10.1007/s10796-019-09936-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Youn S, Shin W. Teens’ responses to Facebook newsfeed advertising: The effects of cognitive appraisal and social influence on privacy concerns and coping strategies. Telematics and Informatics. 2019;38:30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2019.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Yang F, Wang T, Sun J, Hu W. How perceived overqualification relates to work alienation and emotional exhaustion: The moderating role of LMX. Current Psychology 2019 40:12. 2019;40(12):6067–6075. doi: 10.1007/S12144-019-00538-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Ramsey JR, Lorenz MP. A conservation of resources schema for exploring the influential forces for air-travel stress. Tourism Management. 2021;83:104240. doi: 10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2020.104240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N, Zhou G. Social media use and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Moderator role of disaster stressor and mediator role of negative affect. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2020;12(4):1019–1038. doi: 10.1111/APHW.12226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng F, Khan NA, Hussain S. The COVID 19 pandemic and digital higher education: Exploring the impact of proactive personality on social capital through internet self-efficacy and online interaction quality. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;19:105694. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zivnuska S, Carlson JR, Carlson DS, Harris RB, Harris KJ. Social media addiction and social media reactions: The implications for job performance. Journal of Social Psychology. 2019;159(6):746–760. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2019.1578725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study can be attained on the request from the corresponding author.