Abstract

We sought to explore the trust and influence community-based organizations have within the communities they serve to inform public health strategies in tailoring vaccine and other health messages.

A qualitative study was conducted between March 15 – April 12, 2021 of key informants in community-based organizations serving communities in and around Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. These organizations serve communities with high Social Vulnerability Index scores. We explored four key questions including: (1) What was and continues to be the impact of COVID-19 on communities; (2) How have trust and influence been cultivated in the community; (3) Who are trusted sources of information and health messengers; and (4) What are the community’s perceptions about vaccines, vaccinations, and intent to vaccinate in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fifteen key informants from nine community-based organizations who serve vulnerable populations (e.g., mental health, homeless, substance use, medically complex, food insecurity) were interviewed. Five key findings include: (1) The pandemic has exacerbated disparities in existing social determinants of health for individuals and families and have created new concerns for these communities; (2) components of how to build the trust and influence (e.g., demonstrate empathy, create a safe space, deliver on results)resonated with key informants; (3) regardless of the source, presenting health information in a respectful and understandable manner is key to effective delivery; (4) trust and influence can be transferred by association to a secondary messenger connected to or introduced by the primary trusted source; and (5) increased awareness about vaccines and vaccinations offers opportunities to think differently, changing previously held beliefs or attitudes, as many individuals are now more cognizant of risks associated with vaccine-preventable diseases and the importance of vaccines.

Community-based organizations offer unique opportunities to address population-level health disparities as trusted vaccine messengers to deliver public health messages.

Keywords: Trusted Messaging, COVID-19 Vaccine, Vaccine Confidence, Immunization, Community-based organizations

1. Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate toll on racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States (U.S.), resulting in increased rates of unemployment, infections, hospitalizations and deaths [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. Persons of color (POC), who are more likely to be employed as essential workers, have had higher rates of morbidity and mortality as a result of elevated occupational risk of exposure to COVID-19 [6], [7], [8]. Despite the widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines, vaccination coverage rates show continued disparities. More whites than minorities have been vaccinated throughout the U.S., and Black and Hispanic Americans consistently received fewer vaccinations compared to their proportionate number of COVID-19 cases, COVID-19 deaths, and share of the total population [9], [10], [11], [12]. These trends are also reflected in data from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where more vulnerable neighborhoods have consistently had higher rates of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, as well as lower rates of COVID-19 testing and vaccination [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Vaccination rates in Philadelphia are widely variable, with the percentage of residents having received one dose ranging from as low as only 34% in some zip codes, to 85% of residents in more affluent zip codes, despite citywide efforts to reach zip codes with populations at highest risk [13], [19]. The areas with lower vaccination coverage tend to be less affluent and have a higher proportion of POC [13], [19].

A key strategy to begin to address barriers to vaccination and the adverse social factors that contribute to these barriers (e.g., lack of childcare or inability to leave work to receive vaccination services) is engagement of public health and emergency response officials with Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) [20]. Partnerships with CBOs are unique opportunities to influence vaccine decision-making. Individual vaccine decisions are anchored in a cognitive hierarchy where an individual’s deeply held beliefs – which are informed by culture, faith, and education across moral, spiritual, economic, and political domains –affect individual attitudes (i.e., how one reacts); as beliefs and attitudes are solidified, they become values, all of which are influenced by social norms and a confluence of other factors [21], [22], [23], [24]. These other factors – empirical and theoretical – include complacency (not perceiving diseases as high risk), constraints (structural and psychological barriers), calculation (engagement in information searching) and perceptions of collective responsibility (willingness to protect others) [25].

As a CBO engages with individuals within the community, we posit that the CBOs can influence vaccine decision-making. CBOs work at the community level and seek to support the physical, behavioral, public health and social needs of the communities they serve; they have often included social service agencies, nonprofit organizations and formal or informal community groups (e.g., neighborhood groups) [26]. Moreover, CBOs have earned the trust of the communities they serve, and trust is central to influencing and delivering health messaging. For vaccine decision-making, trust in the vaccine and trust in the system that developed and delivers vaccines is particularly important to minority populations who have experienced historical injustices by medical professionals and the government, lower access to healthcare, lower participation in clinical trials, and high costs of care [8], [27], [28], [29]. As messages about vaccines are delivered, the messenger and the medium are important to be contextualized within a cultural identity, particularly within vulnerable communities [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]. As such, CBOs can serve as a critical link between communities and public health programs to deliver salient messages through an appropriate, well-placed medium that resonates with the community [35].

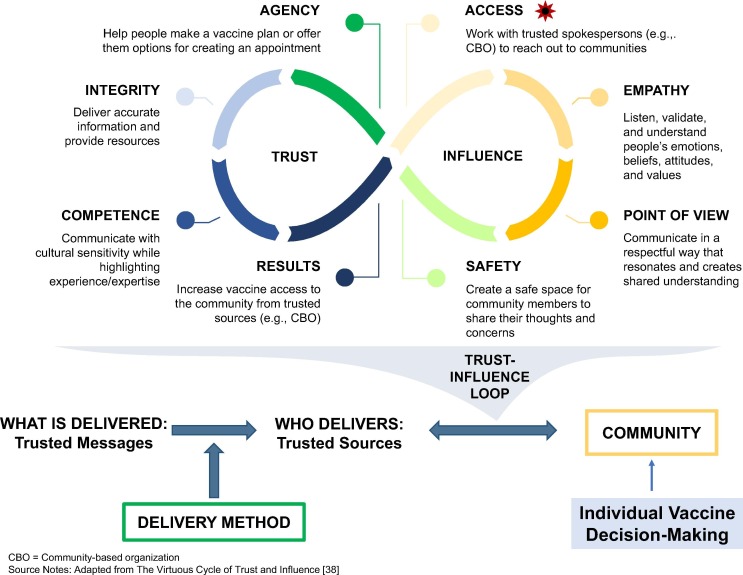

Given the importance of both trusted messages and trusted messengers to vaccine decision-making outlined above, we adapted a Trust and Influence Loop model, developed by a business marketing firm named Leading Agile, and applied it to community-based organizations in the context of vaccine messaging [36]. At the core of this model is the idea that building trust, and trustworthiness, is the first key step to eventually having permission to influence behavior (vaccine decision-making, in our context), and given the unique position of CBOs in communities, we believe they are a critical medium. At the top of Fig. 1 , “Access” is the entry point onto the Loop. CBOs have access to communities as embedded organizations serving communities. Organizations that build trust in the community relate with “Empathy” and listen to those individuals they serve and their “Points of View” creating a shared understanding and “Safe” space for community members to engage within. This creates “Agency,” or permission for CBOs to operate to fulfill their missions (e.g., enrich and strengthen families) with the community on behalf of community. Delivering on their respective missions builds the “Integrity” of CBOs. When a CBO consistently delivers on their mission (e.g., housing the homeless, securing jobs for the jobless, feeding the hungry) in a transparent and “Competent” way, these “Results” broaden the trust and influence to enhance greater access and adoption of given goals within the community. These components, as adapted from the virtuous cycle of a Trust and Influence Loop model by LeadingAgile [36], are useful to understand because of growing interest in supporting innovative ways to identify and address health-related social needs, particularly of the most vulnerable communities [37]. While the core concepts of building relationships of trust in vulnerable communities to eventually transform health is well-documented in the health literature [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [33], [34], [35], [38], [39], [40], [41], our use of these specific steps from this business marketing Trust and Influence Loop model is a novel application to the vaccine decision-making literature. Using these concepts, partnerships with CBOs provide unique opportunities to address population health disparities.

Fig. 1.

Application of Trust-Influence Marketing Model Applied to Public Health Vaccine Messaging.

At the bottom of Fig. 1, the Trust and Influence of CBOs can be a resource in collaboration with public health to deliver trusted messages through delivery methods that resonate with communities. This can have an impact on individual vaccine-decision making, particularly among communities hesitant to vaccinate, with COVID-19 or routine vaccines, because of questions and concerns about the vaccines or the system responsible for development and administration immunizations. As public health seeks to develop tailored messages in a hyperlocal context, a greater understanding of how to develop, manage and sustain partnerships with community and social services organizations is needed [37]. This study explores how: 1) CBOs develop trust and build influence in the communities they serve and 2) how might collaboration with CBOs be useful to informing public health strategies in tailoring vaccine and other health messages.

2. Methods

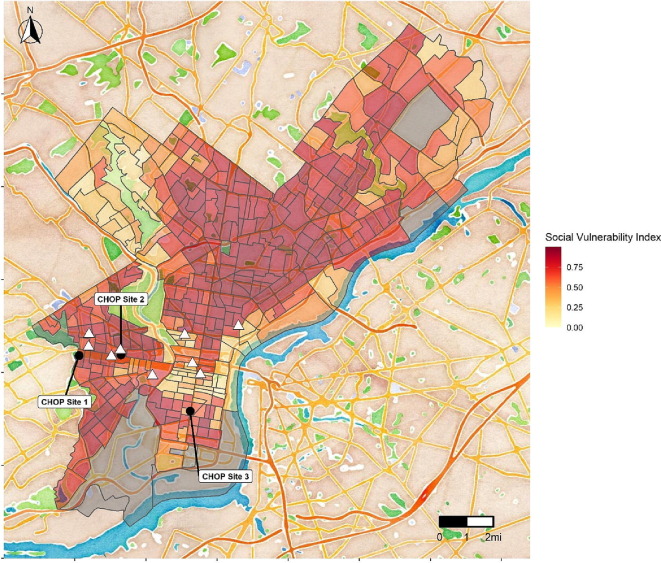

Study Sample: We identified CBOs that serve vulnerable communities as per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) [35], [42]. Through the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Office of External Relations and other community contacts, we identified fifteen CBOs within five miles of the three CHOP urban primary care sites located in Philadelphia, serving communities with high SVI. In Fig. 2 CHOP urban clinics sites and CBO locations are shown overlaid with the SVI map. Darker red areas indicate higher vulnerability or socioeconomic disadvantage.

Fig. 2.

Community Based Organizations Locations with Social Vulnerability Index Overlay, Source Notes: All community-based organizations included in this study were within four miles of one of three Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia primary care site.

From March 15 – April 12, 2021, we contacted fifteen CBOs; nine of them responded. We interviewed key informants from nine of the fifteen CBOs, defined as individuals with expert knowledge of the agency and its role in their communities [43]. Interviews were sixty minutes and included four key questions:

(1) What was and continues to be the impact of COVID-19 on communities?

(2) How have components of trust and influence been cultivated in your community?

(3) Who do you think are trusted sources of information and health messengers? and

(4) What do you think are the community’s perceptions about vaccines, vaccinations, and intent to vaccinate in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Questions on key informants’ perceptions of the community’s barriers to immunization, perceptions of risk and acceptance of routine immunizations, receptivity for vaccinations, and myths and misconceptions were also included. A doctoral-level health services researcher conducted each interview, and a research assistant took notes at each session. Interviews were recorded and notes were anonymized prior to analysis to protect interviewees’ identities. Content analysis was performed on the interview notes. Recordings were used as reference sources to aid in analysis. Deductive thematic analysis used around the four key interview questions and the elements in the Trust and Influence Loop [36] (Fig. 1 ) to identify major emergent themes and representative quotes across informants [44], [45], [46], [47], [48].

The CHOP Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study. Participants were consented prior to the initiation of interviews.

3. Results

We interviewed fifteen key informants representing employees (including executive, management and frontline providers) from nine CBOs that serve clients across the catchment area served by three CHOP urban sites, primarily Philadelphia and neighboring zip codes in New Jersey. These CBOs were well-established in their respective communities, averaging 53 years of community presence (range: 11–151 years). Three of the organizations provide health-related services, and all were actively engaged in their respective missions in three ways: 1) Offering programs or providing health services, 2) advocating for community participants, and 3) engaging in partnerships to serve life needs (e.g., job placement). Communities served by the organizations interviewed included predominantly Black and Latinx populations, vulnerable individuals (e.g., homeless), families who face structural challenges in access to healthcare (e.g., lack of transportation, limited internet access), and individuals and families that receive Medicaid or were uninsured including special populations (e.g., immigrant populations). The target population included mental health, homeless, substance use, medically complex, education, and maternity.

Interview themes:

Question 1: Impact of COVID-19 on communities.

Key informants described common concerns about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their communities as having exacerbated existing social determinants of health for individuals and families in four major ways (Table 1 ). The first theme included how problems existing before the pandemic are still prevalent, such as substance abuse and language barriers to access to services. The second theme described how existing socioeconomic problems before the pandemic are now magnified and exacerbated. For example, lack of insurance or childcare, difficulty getting medical appointments, and loss of job or unemployment. The third category of concerns were new problems that have emerged since the pandemic. As a result of social distancing requirements, for example, fewer clients can be seen at CBO facilities, limiting the impact and ability to reach target populations. Linkages to services like meals and healthcare at school-based clinics have also been reduced or canceled. The last theme involved emotional issues that have been spurred by the pandemic (e.g., fear of death, feelings of fear and instability, concerns that children are falling behind in education).

Table 1.

Key Informant Views on the Impact of Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Communities.

| Themes and indicative quotes | Examples and indicative quotes |

|---|---|

|

THEME 1: Existing problems before the pandemic are still prevalent “People who didn’t have before, still don’t have now” |

Living in food desserts. “In a city like Camden, they haven’t had a full-service grocery store in 50 years.” Barriers to access to services.“Do I go to the emergency room or wellness center or urgent care or my own doctor?” Work schedules hinder the ability to access services.“If I don’t work, I don’t get paid” Mistreatment from the medical establishment.“People just want to be treated with respect and patience” |

|

THEME 2: Existing problems before the pandemic are now magnified and exacerbated |

The “Peloton” affect where there are more options in general in the suburbs.“Higher income means more living space which means more options in managing quarantine life in the pandemic” Limited transportation. “Fear of getting on SEPTA if they didn’t drive” NB: SEPTA = Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority |

|

THEME 3: New problems have emerged |

Housing instability (e.g., eviction).“What will happen when extensions for housing stop” Digital divide when making appointments or schedule vaccinations.“Technology is tough enough but then to add the hunger games aspect or lottery game” Unemployment and implications of unemployment (e.g., inability to pay school loans, loss of health insurance). “In addition, unemployment being the highest it’s been possibly not in history but close, so even having money to get on the bus or money for that co-pay it’s more limited.” |

|

THEME 4: Emotional challenges have been caused by the pandemic |

Grief from loss of family members.“I think there is a lot of grief and loss. We had a lot of families that have had really serious COVID in their home or their families, a lot of people have lost family members.” Feelings of isolation due to shut down of society, including closure of in-person schooling.“The isolation of shutting everything down, especially schools, has been really impactful and most importantly kids are just going to fall more behind” |

Question 2: How trust and influence are cultivated in communities.

Key informants echoed the sentiment that CBOs are deeply rooted in the communities they serve and that having a daily presence that communities can rely on consistently was central to their ability to build trust with and impact their community. Table 2 characterizes key informants’ views on each of the components of the Trust and Influence Loop (Fig. 1). Informants affirmed that cultivating the trust individuals have with the CBO broadens “Agency” influence and trust in the CBOs as source of information to inform vaccine decision-making. Fig. 1 shows the application of this trust and influence CBOs hold that can be applied to CBOs as a trusted source of health and vaccine information.

Table 2.

Validation of the Components of the Trust Influence Loop in Building Trust and Application to Vaccine Messaging.

| Trust Influence Loop Component | Why communities trust Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) |

|---|---|

|

Gaining Access |

Having access to the community allows CBOs to work within the community on relevant issues important to the community such as providing information about COVID-19 vaccines. Key informants perceived that the communities CBOs serve view their organizations as what one informant stated as “partners”, expounding on how trust is earned over years of engagement. “In the community we have partnered with civic groups, with some faith-based groups and just other community agencies like the YMCA and the city and again we build long term trusted relationships with other groups, health promotion council, other nutrition groups and then again bring them in and they become trusted messengers as well and they establish their own relationships.” |

| Demonstrating Empathy, Sharing Points of View, and Creating a Safe Space |

Key informants stated they listen to their community members thus creating a shared understanding and a safe space to engage. Informants spoke extensively about developing a comfortable rapport and establishing a relationship with the individuals they serve. “Within the community, we have a very active relationship with participants…. Everybody is trained as a coach, including the guards, including the cooks, including the security desk. The idea is that coaching, which is the classic meet people where they are, understand their needs and then coach them to problem solve those needs versus the old fashion let me tell you what you need.” |

| Enabling Agency |

As trust broadens among CBOs and community members, CBOs can increasingly act on behalf of community members to connect individuals to resources they may need, for example, to make a vaccine plan and offer them options for creating a vaccination appointment. Informants felt there was a “role” for them in supporting he community around vaccine decision-making. Through relationships, built over time, respondents felt they were able to affect positive change in the lives of the people they serve. “There is a small leadership team of HHI that has established long term trusted relationships with the shelter over these last 20 years…and based on that foundation, we can bring in other trusted messengers. So we will, for example, in our health education, I’ll be there every week but bring a guest speaker and because I have an ongoing relationship, that secondary speaker tends to be able to come in, in a more privileged window and so I will facilitate that. So that platform of this long-term, consistent relationships from our leadership team is kind of critical to allowing that secondary messenger to be influential.” |

| Building Integrity |

Informants were proud of the work they provide to the community and felt they have earned the trust of community members. “We have a good rapport with the community, they trust us, we have been here for many years and a lot of our staff have also been here for many years and they have developed a great rapport with the members and the members talk to us and they let us know how they feel about the current vaccine for COVID and other vaccines as well.” |

| Striving for Competence |

Key informants emphasized that “authenticity” is the root of, and basis for, trust between their organization and the community. “You need to look like them or have lived in the neighborhood like them. You have to have experience in the community. This is how you build trust.” |

| Delivering Results |

Informants emphasized the impact of their missions in the communities they serve. “I think our organization is very influential in these communities. The longer that we have been in a school, the more parents see us as an integrative part of the school community. The original school we have been there for 10 years and I think we are very well entrenched and families really see us as an important part of the school community. When we are new in a school, it takes time to build that.” |

Question 3: Trusted sources of information and health messengers.

When asked about the main information sources most likely to be used by community members to learn about health, vaccines, and vaccinations, informants cited: friends and family, CBOs and sources shared by CBOs, internet sources, as well as primary care providers and the healthcare system (Table 3 ). Notably, many in the community live in multigenerational households, and beliefs held to be true by older generations were reported as playing a large role in the beliefs and attitudes of subsequent generations. Preference on how information is received (face-to-face, text message, internet) varied across sub-populations (e.g., by age group, immigrants). Informants underscored the importance of tailoring messages and having a “personal touch” for effective message penetration.

Table 3.

Sources of Health Information: Reasons and Preferred Medium of Information Receipt.

| Source | Reasons for Using This Source | Preferred Medium to Communicate |

|---|---|---|

| Friends and Family | Many in the community live in multigenerational households and beliefs held true by older generations affect the beliefs of subsequent generations. |

In PersonConversations happen in an informal way (e.g., people talk to each other when they collect their mail) Electronic sources Text messages |

| Community Based Organizations (CBO) and Sources Shared by CBOs | CBO itself and additionally secondary sources shared and promoted by the CBO are considered a credible source of information because they are trusted. CBOs also, because they are local, provide community specific information including where to access vaccination services. |

Media Flyers, posters, emails, social media In person events Woman’s groups, health fairs, parenting workshops, support groups Routine Touchpoints Interaction with front desk staff |

| Internet Sources | Internet searches and online information provide a convenient and private way to search for information | Google Local website for community-oriented resources |

| Primary Care Provider and Health Care System | Respectful two-way mutual conversations to discuss specific patient-provider context for vaccination was cited as highly valued as perceived by key informants. | Face-to-face consultation was preferred in contrast to telehealth visits, text messages, patient health portal messages, and robo-calls from health systems and provider offices |

Key informants also stated that individuals need to hear information in different ways and multiple times with cultural fluency and competency. They noted opportunities to deliver messages at well-established and attended CBO events (e.g., lunchtime seminars, interactive workshops) and at CBO facilities as community members have a familiarity with these surroundings and “feel safe”, a key component of the trust and influence loop (Fig. 1). Informants also discussed other components of the trust and influence loop including the importance of respect for individuals, stating that trust is deeply interwoven with respect. Several emphasized the importance of providing information in a respectful and understandable way outside of a traditional power dynamic, such as a healthcare provider speaking to a patient in a condescending, paternal tone or manner. Lastly, some respondents stated that influence and credibility as a source of information can be transferred by association to a secondary messenger connected to or introduced by the primary source, a key finding in these discussions.

Question 4: Perceptions about vaccines, vaccinations, and intent in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: beliefs, attitudes, values of community members.

Overall key informants noted that due to the pandemic, community members are more cognizant of the risks of being affected by vaccine-preventable diseases and the importance of vaccines. This increased awareness of risk may offer opportunities for community members to think differently, challenging previously held beliefs or attitudes. As one participant stated, “People are now listening. This can help individuals come to a different conclusion.”.

A summary of key informant’s perceptions of the beliefs, attitudes, and values of community members’ trust in COVID-19 and routine vaccines and the vaccine development and immunization delivery system is in Table 4 . Key themes included mistrust of institutions, conspiracy-related ideologies, feelings of invincibility, feelings of vulnerability, and support of science. For example, informants felt their community members mistrust pharmaceutical companies, politics, and politicians. Likewise, they heard from some sub-populations that COVID-19 vaccines are part of some sort of conspiracy against a particular population group (i.e., residents in communities of color). And, while some community members indicated feeling invincible (i.e., young adults), others felt vulnerable (i.e., older adults). Lastly, some informants felt there was a fundamental support of science in the community (i.e., “vaccines are miracles”).

Table 4.

Perceptions about the Beliefs, Attitudes, and Values of the Communities Served by Community Based Organizations Interviewed.

| Belief or Attitude | Respondents Perception of Community Beliefs or Attitudes |

|---|---|

| Mistrust of Institutions | “I don’t trust institutions administering vaccinations, pharmaceutical companies, politics, politicians.” “I am not waiting with bated breath for city hall or the health commissioner to make an announcement.” “I am skeptical of the vaccine.” |

| Conspiracy | “You only want me to get this vaccine because I’m black.” “I don’t believe I need to wear a mask and I don’t need to get vaccinated.” |

| Invincibility | “I am young and I will not get sick because I am strong.” |

| Vulnerability | “I am older and more vulnerable to getting sick, I want to get vaccinated.” “Not enough people are vaccinated to go back to normal.” |

| Support of Science | “I believe in science and that vaccines are miracle drugs.” |

| Values | Respondent’s Perceptions of Values Important to Communities Served They Serve |

| Family | People want their children to be safe and vaccination may be a way to do this. |

| Social and Community Connection | The community trusts in the partnership they have with the community-based organizations where they live. |

| Religion | Individuals trust those who represent the core religious values they hold to be important. |

| Respect for the Rule of Law | If people need to do something that requires vaccination like travel or go to school, they will more likely get vaccinated. |

| Freedom | Some people will get vaccinated because they want to go out again, safely. |

Key value-related themes that respondents cited included family, social and community connection, religion, respect for the rule of law, and freedom (Table 4). These beliefs, values and attitudes inform individual decision-making. For example, in valuing family, individuals and communities want children to be safe and this value informs parental decision-making to vaccinate children. Social and community connections were also viewed as important; having roots within the community are important to the residents. Respect for religious institutions (e.g., church) and their leaders and respect for the rule of law (i.e., school mandates) were also noted. Lastly, informants felt that freedom resonated with the community, particularly given the restrictive nature of lockdowns and quarantines experienced during the past year. However, this freedom may come in conflict with the rule of law for mandatory vaccination. This tension between the values of freedom and the rule of law (e.g., mandatory vaccination) may be important to explore in future research (e.g., how this might be reconciled).

Intent to vaccinate.

Informants suggested that individuals in their communities would be receptive to COVID-19 vaccination for either themselves or their children based on certain factors, some of which were common across routine and COVID-19 immunizations. These factors listed in Table 5 include compliance to other medical interventions, past experiences, passage of time, freedom, and social norms. For example, some key informants thought that individuals with past experience of severe illness and disease would most likely get vaccinated.

Table 5.

Informants’ Perceptions of Reasons to Vaccinate or Not Vaccinate with COVID-19 and Routine Vaccines.

| Intent to vaccinate | Intent not to vaccinate |

|---|---|

| Co-Morbid Conditions. Individuals with past experience of severe illness and disease or comorbid conditions will more likely get vaccinated with COVID-19 or routine vaccines. For example, the experiences of those with HIV, such as stigma and limited access to services and medications, may make this population receptive to COVID-19 vaccines as this population was challenged in accessing HIV therapies. | Past Behavior. Non-compliance to other medical interventions may mean non-compliance to routine or COVID-19 vaccination. “Clients who do not take their diabetes medicine are not going to get vaccinated. It’s not specific to vaccines.” |

| “Wait and See.” Many individuals may be in a “wait and see” mode, wanting to be vaccinated, just not “first in line”. |

Structural Barriers. Structural barriers to accessing routine or COVID-19 vaccination services, include challenges securing childcare, limited transportation options, and the ability to get time off from work. These real-world challenges existed prior to the pandemic. The feeling that “real life gets in the way” was a common sentiment of the clients served by these interviewees. |

| Freedom. Respondents stated that some in their communities “see the light at the end of the tunnel” and are “ready to move on from the pandemic,” so if vaccines were required to get to where clients wanted to be (e.g., requirement for travel), they would get vaccinated. | |

| Peer Examples. Informants felt that seeing more of the public and more people they know get vaccinated would encourage vaccination. |

Source Notes: Specific to childhood vaccination, informants felt that individuals in communities would want to protect their children against routine vaccine preventable diseases and COVID 19 and that requirements such as school mandates would encourage compliance to vaccination recommendations. One respondent also stated that “vaccines are miracles.”.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the need for strong community dialogue and trust. While only a small number of local CBOs were included in this study, the themes of authenticity, trust, and reliability were central characteristics of CBOs that make them salient collaborators with public health. Understanding the development of these trusted relationships and the informed perspectives of those who have built them provides a framework for establishing effective strategies with public health in partnering around vaccine messaging for not only COVID-19 but routine vaccinations and other public health messages.

Key informants emphasized the importance of authenticity in their interactions with the communities they serve. In doing so, CBOs establish a level of influence and agency to help people navigate the pandemic, make a vaccine plan, or locate appointment options. As trusted messengers, many CBOs can enhance pro-vaccine messages, particularly those who have a long-standing reputation related to improving health and wellness in their local communities (e.g., YMCA). However, it is critical to support these trusted messengers to ensure the accuracy of messages, which are often amplified by friends, family, and social media.

Our interviews echoed the findings of others that COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on underserved groups, such as those from lower socioeconomic demographics and racial and ethnic minority groups. Likewise, our results echoed existing descriptions of structural barriers to access, which are a challenge beyond access to immunization services, particularly for vulnerable communities. Building vaccine confidence and trust in science includes addressing these long-term structural barriers [49], [50]. Future research can corroborate these results with interviews of community members to characterize their beliefs as well as evaluation of interventions conducted in partnership with CBOs.

This study had a few limitations. First, the sample size consisted of 15 individuals representing nine CBOs. While small, the results from these interviews reached thematic saturation; therefore, we did not recruit additional participants. Second, we had a limited scope to our study, exploring the ways in which CBOs built trust and influence in the community broadly. While many key informants stated they were not experts in health communication, the crux of this study was to validate components of the trust-influence loop model and to encourage collaboration with CBOS to inform public health strategies in tailoring vaccine and other health messages. Lastly, we reported on perceptions, experiences, and beliefs of the key informants about individuals who live in the communities they serve; we did not interview individuals directly served by the CBOs.

5. Conclusion

Understanding how CBOs develop and build influence in communities can help public health and medical care providers not only leverage partnerships with these entities during a public health crisis, but also build their own authentic relationships with both CBOs and the residents of their local communities under non-emergency conditions. The relationship between public health and the community, modulated by trusted CBOs can be powerful in improving the lives and experiences of residents while strengthening the trust between public health and communities that may have suffered because of the fragmented and challenging response to the pandemic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Charlotte Moser, Danielle Clark, and Brandi Hight for their thoughtful review of this manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge the efforts of Falguni Patel and her group at the Office of Community Relations at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in helping connect us with community-based organizations.

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- 1.Price-Haywood E.G., Burton J., Fort D., Seoane L. Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2534–2543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa2011686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stokes E.K., Zambrano L.D., Anderson K.N., Marder E.P., Raz K.M., el Burai F.S., et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance — United States, January 22–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:759–765. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6924e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The COVID Racial Data Tracker | The COVID Tracking Project. The Atlantic Monthly Group n.d. https://covidtracking.com/race (accessed October 11, 2020).

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html (accessed November 30, 2020).

- 5.Oppel R.A., Jr., Gebeloff R., Lai K.K.R., Wright W., Smith M. The New York Times. The New York Times; 2020. The Fullest Look Yet at the Racial Inequity of Coronavirus - [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups | CDC 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html (accessed November 29, 2020).

- 7.Hawkins D. Differential occupational risk for COVID-19 and other infection exposure according to race and ethnicity. Am J Ind Med. 2020;63:817–820. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkowitz R.L., Gao X., Michaels E.K., Mujahid M.S. Structurally vulnerable neighbourhood environments and racial/ethnic COVID-19 inequities. Cities Health. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1080/23748834.2020.1792069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. COVID-19 Vaccines | FDA. US Food and Drug Administration 2022. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines (accessed May 8, 2022).

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Demographic Characteristics of People Receiving COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States | CDC COVID Data Tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-demographic (accessed June 21, 2021).

- 11.Hamel L., Lopes L., Sparks G., Stokes M., Brodie M. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2021. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor – April 2021 | KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-april-2021/ (accessed June 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.COVID-19 Health Equity Interactive Dashboard. Emory University 2021. https://covid19.emory.edu/ (accessed June 21, 2021).

- 13.Department of Public Health. Data | Vaccines | Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). City of Philadelphia 2021. https://www.phila.gov/programs/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/vaccines/data/ (accessed January 28, 2021).

- 14.Department of Public Health. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). City of Philadelphia 2021. https://www.phila.gov/programs/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/ (accessed January 13, 2021).

- 15.Bilal U., Tabb L.P., Barber S., Diez Roux A., v. Spatial Inequities in COVID-19 Testing, Positivity, Confirmed Cases, and Mortality in 3 U.S. Cities Ann Intern Med. 2021 doi: 10.7326/m20-3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Board of Health, Managing Director’s Office, Department of Public Health, Office of the Mayor, Office of Emergency Management. City Provides Update on COVID-19 for Wednesday, May 19, 2021 | Department of Public Health | City of Philadelphia. City of Philadelphia 2021. https://www.phila.gov/2021-05-19-city-provides-update-on-covid-19-for-wednesday-may-19-2021/ (accessed June 21, 2021).

- 17.Philadelphia Department of Public Health. Philadelphia COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution Plan. City of Philadelphia 2021. https://www.phila.gov/media/20210119110802/HP_VaccineRPRTr2.pdf (accessed January 22, 2021).

- 18.Brandt J, NBC10 Staff. Why So Many More White People Than Black People Have Been Vaccinated in Philadelphia – NBC10 Philadelphia. NBC 2021. https://www.nbcphiladelphia.com/news/coronavirus/why-so-many-more-white-people-than-black-people-have-been-vaccinated/2668848/ (accessed February 8, 2021).

- 19.Laughlin J, Purcell D. COVID-19 cases have plummeted in Philly, but vaccinating the holdouts remains a struggle. The Philadelphia Inquirer 2021. https://www.inquirer.com/health/coronavirus/vaccine-philadelphia-zip-code-rates-covid-20210621.html (accessed June 22, 2021).

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services. Engaging Community-Based Organizations | Promising Practices for Reaching At-Risk Individuals for COVID-19 Vaccination and Information. Public Health Emergency 2021. https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Pages/engaging-CBO.aspx (accessed January 21, 2022).

- 21.MacDonald N.E., Eskola J., Liang X., Chaudhuri M., Dube E., Gellin B., et al. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33:4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahan D. Fixing the communications failure. Nature. 2010;463:296–297. doi: 10.1038/463296a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornsey M.J., Harris E.A., Fielding K.S. The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: A 24-nation investigation. Health Psychol. 2018;37:307–315. doi: 10.1037/hea0000586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amin A.B., Bednarczyk R.A., Ray C.E., Melchiori K.J., Graham J., Huntsinger J.R., et al. Association of moral values with vaccine hesitancy. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1:873–880. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Betsch C., Schmid P., Heinemeier D., Korn L., Holtmann C., Böhm R. Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0208601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fichtenberg C, Delva J, Minyard K, Gottlieb LM. Health And Human Services Integration: Generating Sustained Health And Equity Improvements. 2020;39:567–73. https://doi.org/10.1377/HLTHAFF.2019.01594. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Khubchandani J., Sharma S., Price J.H., Wiblishauser M.J., Sharma M., Webb F.J. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Rapid National Assessment. J Community Health. 2021;1 doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen L.S., Sadeghi N.B. Addressing Racial Health Disparities In The COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate And Long-Term Policy Solutions | Health Affairs. Health Aff. 2020 https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200716.620294/full/ accessed November 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noonan A.S., Velasco-Mondragon H.E., Wagner F.A. Improving the health of African Americans in the USA: An overdue opportunity for social justice. Public Health Rev. 2016;37 doi: 10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X. Health communication campaigns: A brief introduction and call for dialogue. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7:S11–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Airhihenbuwa C.O., Iwelunmor J., Munodawafa D., Ford C.L., Oni T., Agyemang C., et al. Culture matters in communicating the global response to COVID-19. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020:17. doi: 10.5888/PCD17.200245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witte K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Commun Monogr. 1992;59:329–349. doi: 10.1080/03637759209376276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas T.M., Pollard A.J. Vaccine communication in a digital society. Nat Mater. 2020;19:476. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-0626-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chou W.Y.S., Budenz A. Considering Emotion in COVID-19 Vaccine Communication: Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy and Fostering Vaccine Confidence. Health Commun. 2020;35:1718–1722. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1838096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Considerations for Community-Based Organizations | COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/organizations/community-based.html (accessed January 19, 2022).

- 36.LeadingAgile. The Virtuous Cycle of Trust and Influence. Medium 2021. https://leadingagile.medium.com/the-virtuous-cycle-of-trust-and-influence-2b8c5a50381b (accessed June 21, 2021).

- 37.Agonafer E.P., Carson S.L., Nunez V., Poole K., Hong C.S., Morales M., et al. Community-based organizations’ perspectives on improving health and social service integration. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–12. doi: 10.1186/S12889-021-10449-W/TABLES/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Make J., Lauver A. Increasing trust and vaccine uptake: Offering invitational rhetoric as an alternative to persuasion in pediatric visits with vaccine-hesitant parents (VHPs) Vaccine X. 2022:10. doi: 10.1016/J.JVACX.2021.100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marie Reinhart A., Tian Y., Lilly A.E. The role of trust in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance among Black and White Americans. Vaccine. 2022;40:7247. doi: 10.1016/J.VACCINE.2022.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen A.K., Tan A.S.L. Trust, influence, and community: Why pharmacists and pharmacies are central for addressing vaccine hesitancy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2022;62:305. doi: 10.1016/J.JAPH.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawlor E.R., Cupples M.E., Donnelly M., Tully M.A. Implementing community-based health promotion in socio-economically disadvantaged areas: a qualitative study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2020;42:839. doi: 10.1093/PUBMED/FDZ167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry | Geospatial Research A and SP. CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) 2018 Database. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention n.d. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html (accessed November 15, 2020).

- 43.Marshall M.N. The key informant technique. Fam Pract. 1996;13:92–97. doi: 10.1093/FAMPRA/13.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamilton A. Qualitative Methods in Rapid Turn-Around Health Services Research. Health Services Research & Development | US Department of Veterans Affairs 2013.

- 45.Hamilton A.B., Finley E.P. Qualitative Methods in Implementation Research: An Introduction. Psychiatry Res. 2019;280 doi: 10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2019.112516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirk M.A., Kelley C., Yankey N., Birken S.A., Abadie B., Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2016;11:1–13. doi: 10.1186/S13012-016-0437-Z/TABLES/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Averill J.B. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:855–866. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative Data Analysis : A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publishing; 2014.

- 49.Shen AK, Sobcyzk E, Browne S, Moser C. Reaching Herd Immunity for COVID-19 Vaccine Means Long-Term Investments | LDI. Penn LDI | HEALTH Policy$ense 2021.

- 50.Webb Hooper M., Nápoles A.M., Pérez-Stable E.J. No Populations Left Behind: Vaccine Hesitancy and Equitable Diffusion of Effective COVID-19 Vaccines. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2130–2133. doi: 10.1007/S11606-021-06698-5/METRICS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.