Abstract

Background

Changes to drug markets can affect drug use and related harms. We aimed to describe market trends of heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and ecstasy in Australia following the introduction of COVID-19 pandemic-associated restrictions.

Methods

Australians residing in capital cities who regularly inject drugs (n ∼= 900 each year) or regularly use ecstasy and/or other illicit stimulants (n ∼= 800 each year) participated in annual interviews 2014-2022. We used self-reported market indicators (price, availability, and purity) for heroin, crystal methamphetamine, cocaine, and ecstasy crystal to estimate generalised additive models. Observations from the 2014-2019 surveys were used to establish the pre-pandemic trend; 2020, 2021 and 2022 observations were considered immediate, short-term and longer-term changes since the introduction of pandemic restrictions.

Results

Immediate impacts on market indicators were observed for heroin and methamphetamine in 2020 relative to the 2014-2019 trend; price per cap/point increased (β: A$9.69, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.25-17.1 and β: A$40.3, 95% CI: 33.1-47.5, respectively), while perceived availability (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] for ‘easy’/’very easy’ to obtain: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.24-0.59 and aOR: 0.08, 95% CI: 0.03-0.25, respectively) and perceived purity (aOR for ‘high’ purity: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.23-0.54 and aOR: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.20-0.54, respectively) decreased. There was no longer evidence for change in 2021 or 2022 relative to the 2014-2019 trend. Changes to ecstasy and cocaine markets were most evident in 2022 relative to the pre-pandemic trend: price per gram increased (β: A$92.8, 95% CI: 61.6-124 and β: A$24.3, 95% CI: 7.93-40.6, respectively) and perceived purity decreased (aOR for ‘high purity’: 0.18, 95% CI: 0.09-0.35 and 0.57, 95% CI: 0.36-0.90, respectively), while ecstasy was also perceived as less easy to obtain (aOR: 0.18, 95% CI: 0.09-0.35).

Conclusion

There were distinct disruptions to illicit drug markets in Australia after the COVID-19 pandemic began; the timing and magnitude varied by drug.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Illicit drug, Drug markets, Big events

Introduction

Drug markets are a known determinant of drug use and harms (Hughes et al., 2020). For example, an abrupt change in heroin availability in Australia in the early 2000s was marked by decreased frequency of heroin injection and rates of opioid-related fatal and non-fatal overdose but also increased use of other drugs and higher-risk injecting practices among some people (Degenhardt et al., 2006; Dietze et al., 2004; Weatherburn et al., 2003). Likewise, a global ecstasy shortage in the early 2010s was accompanied by proliferation of new psychoactive substances, some of which have been associated with elevated risk of acute harm (Peacock et al., 2019). Monitoring changes in drug markets is thus critical to pre-empt and understand potential shifts in drug use and harms.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated border closures and restrictions on movement in early 2020, disruption to illicit drug markets was predicted based on historical periods of economic, political and environmental upheaval (Zolopa et al., 2021), albeit with noted uncertainty (Giommoni, 2020). Closure of international borders was expected to limit supply chains globally, while physical distancing measures and associated policing were anticipated to disrupt supply and acquisition at a local level (Dietze & Peacock, 2020).

To date, several studies using data collected in interviews with people who use drugs have described increased price, reduced availability and lower purity of illicit drugs in the initial months of the pandemic. Specifically, increases in price of cannabis and tranquilizers were reported in Norway (Welle-Strand et al., 2020), increased price and decreased perceived purity of drugs were reported in India (Arya et al., 2022), a general decline in perceived quality of drugs was reported in Canada (McAdam et al., 2022), and impacts to price and perceived availability of multiple drugs were noted in Georgia (Otiashvili et al., 2022), Australia (Price et al., 2022), and across Europe (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2022). In contrast, other studies reported limited impact to drug markets in Germany (Namli, 2021) and Switzerland (Gaume et al., 2021). These studies typically relied on participants reporting perceived changes in drug markets early in the pandemic. More rigorous inquiry would require comparison with indicators collected prior to the pandemic.

Given the known resilience of drug markets (Bouchard, 2007), it is important to monitor responses to market disruptions over extended periods. However, studies of the market situation beyond the first year of the pandemic are limited in number and scope. Drug seizure data have been interpreted as a recovery for some drug markets, including methamphetamine in the US and Europe, in late 2020 and 2021 after initial supply disruptions (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2022; Palamar et al., 2021; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022), although reduced law enforcement operational capacity is noted.

With no land borders and a reliance on international importation for most drugs (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, 2021), Australia's illicit drug supply was thought to be particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 associated border restrictions. Using annual cross-sectional data collected from people who regularly use illicit drugs in Australia from 2014-2022, the aim of this study was to investigate the immediate (2020), short-term (2021) and longer-term (2022) changes in price, perceived purity, and perceived availability of heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and ecstasy since COVID-19 restrictions were introduced relative to the preceding trend (2014-2019).

Methods

Study design and procedure

Annual interviews with cross-sectional samples of people who regularly inject drugs and people who regularly use ecstasy and/or other illicit stimulants were conducted in all Australian capital cities from 2014-2022. These data were collected as part of the Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS; (Sutherland, Uporova, et al., 2022a)) and the Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS; (Sutherland, Karlsson, et al., 2022a and 2022b)). IDRS participants were recruited through needle-syringe programs and treatment agencies and via word-of-mouth; EDRS participants were recruited via social media and word-of-mouth. Convenience sampling is used, so participants are not considered to be representative of the broader populations of people who inject drugs or people who use ecstasy and/or other illicit stimulants. To be eligible for IDRS, people had to be ≥18 years of age (17 years in surveys conducted prior to 2020); report injecting illicit/non-prescribed drugs ≥monthly in the past six months; and have resided in the capital city of interview for ≥10 of the previous 12 months. The same criteria applied for EDRS except that people had to have used ecstasy and/or other illicit stimulants on a ≥monthly basis. Prior to 2020, interviewer-administered structured surveys were conducted face-to-face; subsequently, interviews in some jurisdictions were conducted via telephone/videoconference due to pandemic restrictions. Informed consent was obtained and participants were reimbursed A$40.

IDRS data are typically collected from May to July; EDRS from April to June (see Appendix A for details of data collection timing). For brief context, Australia adopted an ‘elimination’ approach to COVID-19 until late 2021, characterised by strict lockdowns and social distancing protocols which varied by jurisdiction. From November 2021, after Australia reach high vaccination coverage, international borders were opened and there were no further lockdowns.

Ethical approval for IDRS was granted by the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and jurisdictional HRECs; approval for EDRS was granted by the University of New South Wales HREC and jurisdictional HRECs.

Findings are reported according to the STROBE checklist (Appendix B); full methodological details can be found elsewhere (Sutherland, Karlsson, et al., 2022; Sutherland, Uporova, et al., 2022b).

Measures

We analysed drug market data for the two illicit drugs most commonly injected among the IDRS sample (heroin and crystal methamphetamine) and used among the EDRS sample (ecstasy and cocaine). Although questions regarding these drugs are asked in both surveys, small numbers report using or injecting the drugs chosen for analysis in the alternate survey. Furthermore, survey timing and recruitment methods differ between studies, so to maintain internal validity, we did not pool data between studies.

Sociodemographic and drug use characteristics

Participants reported age, gender, current accommodation, current paid employment, current drug treatment, drug injected (IDRS) or used (EDRS) most in the past month, and days of use in the past six months of heroin and crystal methamphetamine (IDRS) or cocaine and ecstasy (EDRS). We focused on ecstasy crystal in the main analysis as market indicator data for pills and capsules were combined from 2014-2016.

Illicit drug market indicators

We used three indicators (price, perceived availability, and perceived purity), which are often used in surveillance research to understand drug markets (Dwyer & Moore, 2010). Use of all three indicators provides a better insight than one in isolation. For example, an increase in drug cost may manifest as a price increase, or a decrease in drug purity while the price is held constant (Caulkins & Reuter, 2006).

To analyse drug price, we chose the most common quantity measure reported for each drug: heroin (cap/point; equivalent to 0.1g), crystal methamphetamine (point; 0.1g), cocaine (gram), ecstasy (per pill, capsule, and gram of crystal). In 2020, participants reported which month this purchase occurred, which enabled exclusion of pre-pandemic restriction observations in 2020 (we assumed that the timing of perceived availability and purity corresponded with last purchase). To ascertain perceived current availability and purity, participants were asked ‘how easy is it to obtain the drug at the moment?’ (response options: ‘very easy’, ‘easy’, ‘difficult’ and ‘very difficult’) and ‘how strong would you say the drug is at the moment?’ (‘low’, ‘medium’, ‘high’, ‘fluctuates’).

Data analysis

Our analysis plan was pre-registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/vy83j?view_only=a155bacd5b1a4c4c968c0cb6fddd-5830). Analysis was undertaken in R version 4.0.2.

Illicit drug market analyses

The availability of only eight annual time points precluded use of traditional time series analysis. Instead, generalised additive models (GAM) were estimated using the mgcv package (Wood, 2012) to model trends in market indicators, with thin plate spline functions for year of interview, allowing for non-linear relationships between predictor(s) and outcome. Six years of data pre-pandemic (2014-2019) were included to elucidate trends prior to pandemic-related restrictions (2014 was the earliest year ecstasy crystal market indicator data were collected). Previous analyses suggest that market indicator data for heroin, crystal methamphetamine and cocaine were generally consistent in the years preceding 2014 (Man et al., 2021; Man et al., 2022; Sutherland, Uporova, et al., 2022a).

To allow for known differences in illicit drug markets by Australian jurisdiction, we considered three models: Model 1 where spline functions for year were fitted by jurisdiction (i.e., an interaction term between year and jurisdiction), allowing trends over time (i.e., the slope at each knot) to vary by jurisdiction, with jurisdiction also included as a fixed effect; Model 2 where jurisdiction was incorporated as a fixed effect only; and Model 3 where jurisdiction was excluded. Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were used to determine which model was the best fit. The number of knots was chosen using the generalised cross validation criterion, whereby parsimony is balanced with explanatory power. To evaluate the suitability of GAMs, we also compared the fit of a generalised linear model (with year as a linear covariate) to assess linearity and potential overfitting.

Seasonality was controlled for by incorporating month of interview in the model. As market indicator data were self-reported and may be subject to individual variability, models were adjusted for individual characteristics that may influence illicit drug access: age, gender, and drug use frequency (Dave, 2008; Maher, 1996; McAdam et al., 2022; Munksgaard et al., 2022). Age was fitted using spline functions (due to changes in eligibility criteria in 2020, those aged <18 years were excluded, IDRS n=2; EDRS n=197); gender was included as a binary variable (male/female, those who identified as non-binary or gender-fluid were excluded due to small numbers which resulted in zero cell counts for some combinations of covariates and outcome levels (Greenland et al., 2016); IDRS n=37, EDRS n=93); and frequency of use of the substance analysed was included as a binary variable (<weekly/≥weekly during the six months preceding interview; those who had not used the substance but responded were included as <weekly use).

To assess changes in market indicators since the introduction of COVID-19 restrictions (in 2020-2022), three dummy variables corresponding to those years were included in the model. This is a common technique used in time series analyses to measure the effect of an event on an outcome (e.g., Narayan et al., 2021).

Price data were converted to 2022 Australian dollars (A$) using consumer price index rates published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022). For heroin and crystal methamphetamine, prices per cap/point <$10 or higher than the median price of a gram in the relevant jurisdiction and year were considered outliers and excluded (Scott et al., 2015). For cocaine and ecstasy crystal, prices per gram <$50 were excluded. For availability, responses were converted into a binary variable: easy (‘very easy’ and ‘easy’) and difficult (‘very difficult’ and ‘difficult’). For purity, responses were converted into a binary variable clustering ‘low’, ‘medium’ and ‘fluctuates’ (versus ‘high’).

The coefficient and 95% confidence interval (95% CI; calculated using standard errors obtained from the adjusted variance-covariance matrix) are presented for COVID-19 event variables. For the purposes of visualisation, we fit a simple GAM with year of interview the only predictor. Results for perceived purity and availability of ecstasy pills and capsules are presented descriptively as there were insufficient data points pre-COVID to generate a trend line.

Sensitivity analyses

Although repeat participation in annual cross-sectional studies is unlikely to affect population-level inferences (Agius et al., 2018), models were re-estimated with non-first-time participants removed. In a second sensitivity analysis, we re-estimated price models without inflation adjustment.

Missing data

The nature of these analyses meant the model for each market indicator was limited to non-missing outcome observations. Then, for each market indicator, we assessed the nature of missingness for the covariates. Little's test suggested data were missing completely at random across all indicators (Little, 1988). Therefore, we utilised a complete case approach.

Results

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics remained mostly consistent across the 2014-2022 samples. The majority of IDRS participants were male (range 59-69%; Appendix C), unemployed (83-88%) and residing in stable housing (e.g., own/rented home, public housing; 82-90%). Fewer than half the sample reported current drug treatment (range 37-48%). Mean age increased over time (41 years in 2014 to 46 in 2022), as did the percent citing methamphetamine as the drug injected most frequently in the month prior to interview (30% in 2014 to 54% in 2022).

For EDRS, the majority of participants were male (range 56-66%; Appendix D) and resided in stable housing (98-99%), while mean age fluctuated (21.5-26.7 years). Unemployment generally remained less than one-third of the samples (12-27%), except in 2020 (35%). Few reported current drug treatment (2-5%). From 2014-2020, approximately one-quarter of the sample reported weekly or more frequent use of ecstasy in the past six months, which decreased in 2021 (12%) and 2022 (13%). Weekly or more frequent use of cocaine was generally reported infrequently (1-9%).

Changes in drug market indicators

Detailed data regarding annual number of observations per market indicator, model selection, and model results are available in Appendices E, F, and G, respectively.

Heroin

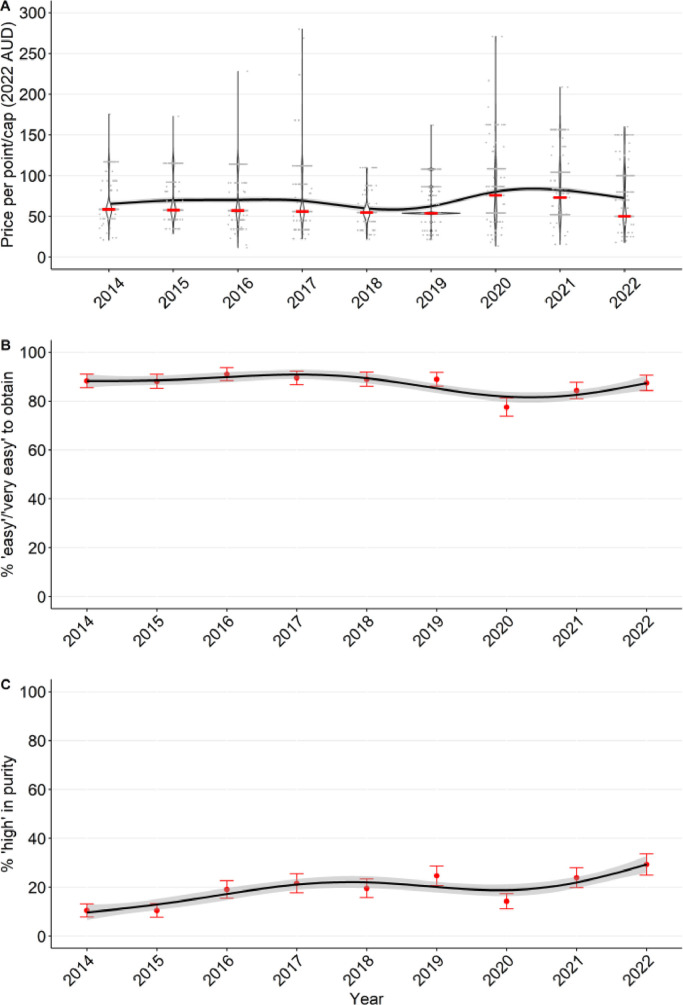

Model 1 was selected for price (inclusion of an interaction term between year and jurisdiction); Model 2 was selected for availability and purity (jurisdiction included as fixed effect only). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the inflation-adjusted median price per heroin cap/point reported by IDRS participants had decreased from A$58.5 in 2014 to A$54.0 in 2019 (Fig. 1 A). The model fitted suggested the price increased in 2020 relative to the pre-pandemic trend (β: A$9.69, 95% CI: A$2.25, 17.1; Fig. 5). Although median reported price remained higher in 2021 (A$73.0), there was no evidence for change in 2021 relative to the pre-pandemic trend (β: A$10.5; 95% CI: A$-0.37, 21.3). In 2022, the median price returned to pre-pandemic levels (A$50.0) and accordingly, the model indicated no evidence for change compared to the existing trend (β: A$4.99; 95% CI: A$-9.68, 19.7).

Fig. 1.

Heroin market trends, IDRS samples 2014-2022. A) Last reported price per point/cap. B) Percent reporting perceived availability as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’. C) Percent reporting perceived purity as ‘high’.

Notes. In each figure the relationship between year and outcome is modelled using a generalised additive model. A) The distribution of individual price observations is summarised as a smoothed density plot; the grey dots represent individual observations; the red line indicates the median price. B & C) The dots represent the mean percent and bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

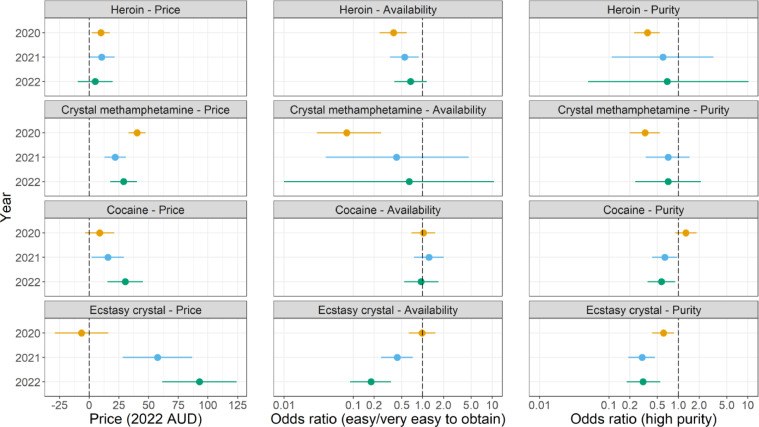

Fig. 5.

Results of generalised additive models for illicit drug price, perceived availability, and perceived purity.

Notes. Estimates represent the coefficient for each level of the ‘COVID-19’ variable (i.e., years 2020-2022), compared to the underlying pre-COVID trend 2014-2019. Coefficients were estimated using generalized additive models. For availability and purity, coefficients are plotted on the log scale. Exact values for coefficients and corresponding confidence intervals are provided in Appendix G.

Heroin was consistently described as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to obtain by at least 80% of the IDRS sample each year since 2014 (Fig. 1B). However, we observed a decrease in perceived availability in 2020 and 2021 compared to 2014-2019. The effect size of these changes decreased over time: the aOR of perceiving availability as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ in 2020 was 0.38 (95% CI: 0.24, 0.59; Fig. 3) and in 2021 it was 0.55 (95% CI: 0.34, 0.78). In 2022 there was no longer evidence for change compared to the pre-pandemic trend (aOR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.39, 1.14).

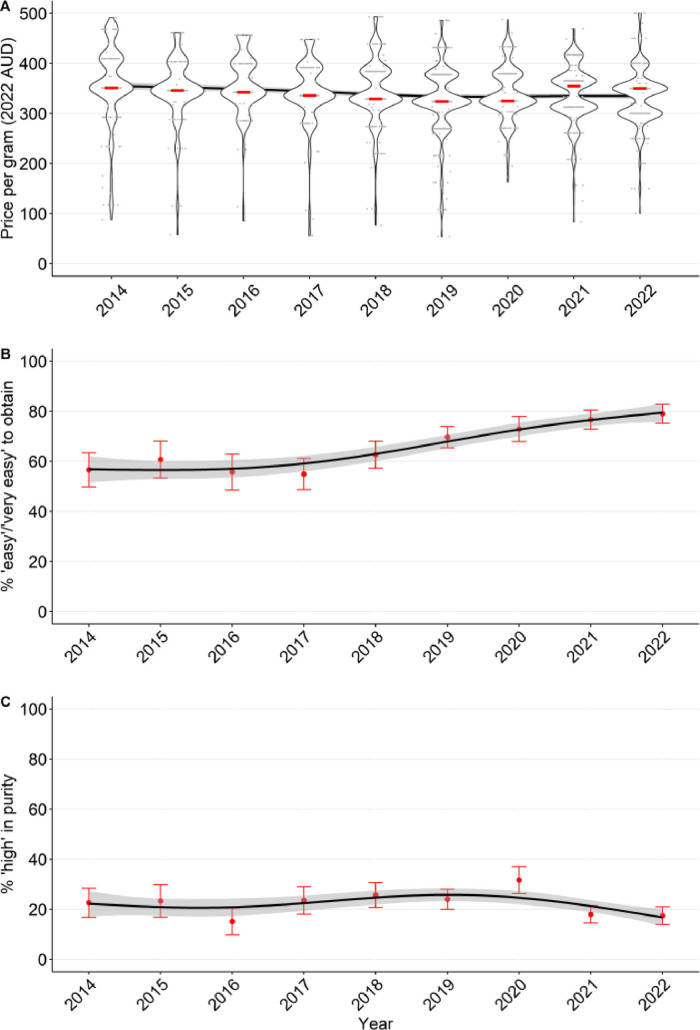

Fig. 3.

Cocaine market trends, EDRS samples 2014-2022. A) Last reported price per gram. B) Percent reporting perceived availability as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’. C) Percent reporting perceived purity as ‘high’.

Notes. In each figure the relationship between year and outcome is modelled using a generalised additive model. A) The distribution of individual price observations is summarised as a smoothed density plot; the grey dots represent individual observations; the red line indicates the median price. B & C) The dots represent the mean percent and bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

The number of IDRS participants reporting heroin as high in purity increased from 2014, albeit with some fluctuation (Fig. 1C). There was a decrease in 2020, which was reflected in the model (aOR of perceiving heroin as ‘high’ in purity: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.23, 0.54). However, there was no evidence for any change in purity in 2021 (aOR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.11-3.21) or 2022 (aOR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.05, 10.3), compared to the pre-pandemic trend.

Crystal methamphetamine

Model 1 was selected for price and Model 2 was selected for availability and purity. The inflation-adjusted median reported price per point of crystal methamphetamine decreased each year from 2014 (A$117) to 2019 (A$54), and then sharply increased in 2020 (A$108), which was reflected when comparing the price per point in 2020 compared to the 2014-2019 trend (β: A$40.3; 95% CI: A$33.1, 47.5). While the median price was lower in 2021 (A$52.1) and 2022 (A$50.0), the effects were still significant compared to the 2014-2019 trend (2021 β: A$21.9; 95% CI: A$12.8, 30.9, and 2022 β: A$28.9; 95% CI: A$17.7, 40.2).

Crystal methamphetamine has been consistently reported as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to obtain by at least 90% of IDRS participants each year since 2014 (Fig. 2 B). There was a significant decrease in perceived availability observed in 2020 compared to the pre-pandemic trend (aOR: 0.08; 95% CI: 0.03, 0.25), but there was no longer any evidence for change in 2021 (aOR: 0.42: 95% CI: 0.04, 4.63) or 2022 (aOR: 0.64: 95% CI: 0.01, 10.7).

Fig. 2.

Crystal methamphetamine market trends, IDRS samples 2014-2022. A) Last reported price per point. B) Percent reporting perceived availability as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’. C) Percent reporting perceived purity as ‘high’.

Notes. In each figure the relationship between year and outcome is modelled using a generalised additive model. A) The distribution of individual price observations is summarised as a smoothed density plot; the grey dots represent individual observations; the red line indicates the median price. B & C) The dots represent the mean percent and bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Approximately 30-40% of IDRS participants reported that the purity of crystal methamphetamine was ‘high’ from 2014 to 2019 (Fig. 2C). The model suggested that perceived purity significantly decreased in 2020 compared to the pre-pandemic trend (aOR: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.20, 0.54), while there was no evidence for any difference in 2021 (aOR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.34, 1.46) or 2022 (aOR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.24, 2.12).

Cocaine

Model 2 was selected for price and purity and Model 1 was selected for availability. The inflation-adjusted median price per gram of cocaine decreased from 2014 to 2019 (A$351 to A$324; Fig. 3 A). There was no evidence for any change to this trend in 2020 (β: A$16.7; 95% CI: A-$3.28, 30.1). The median price was higher in 2021 (A$365) and 2022 (A$350). This observation was consistent when compared to the pre-pandemic trend (2021 β: A$17.2; 95% CI: A$2.39, 32.1 and 2022 β: A$24.3; 95% CI: A$7.93, 40.6).

Perceived availability of cocaine remained stable from 2014 to 2017 before increasing steadily until 2022 (Fig. 3B). There was no evidence for any changes in perceived availability in 2020, 2021 or 2022 relative to the existing trend (Fig. 5).

The percentage of EDRS participants reporting cocaine as ‘high’ in purity has been low with some fluctuation since 2014 (Fig. 3C). There was no evidence for change in perceived purity of cocaine in 2020 compared to the existing trend (Fig. 5), but it decreased in 2021 (aOR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.42, 0.96) and 2022 (aOR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.36, 0.90).

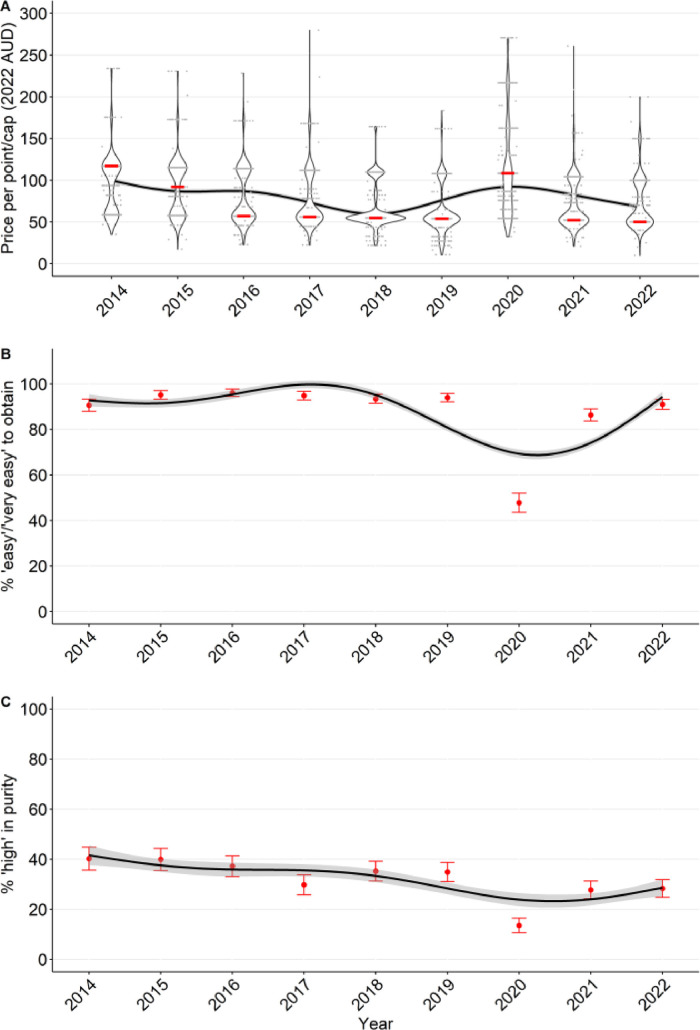

Ecstasy

Model 1 was selected for all three market indicators. The inflation-adjusted median reported price per gram of ecstasy crystal steadily decreased from 2014 (A$328) to 2019 (A$194; Fig. 4 A). There was no evidence for any change to this trend in 2020 (β: -A$6.42; 95% CI: -A$28.9, 16.1). However, in 2021 and 2022 the median price increased to A$209 and A$250, respectively, which was reflected in the model (2021 β: A$57.5; 95% CI: A$28.3, 86.6 and 2022 β: A$92.8; 95% CI: A$61.6, 124.1).

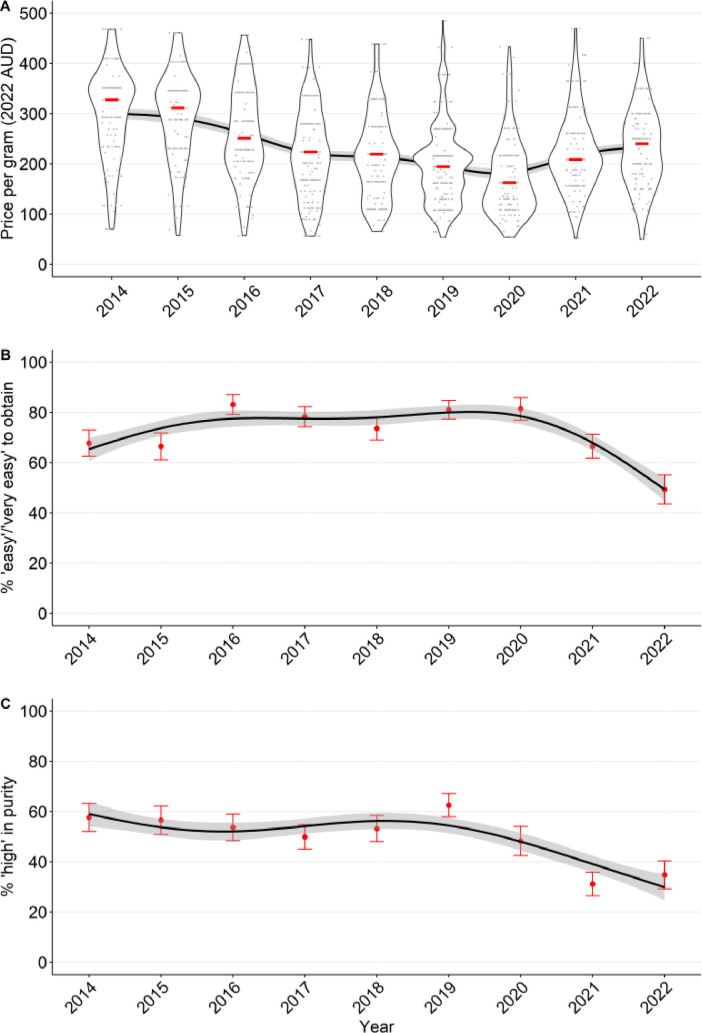

Fig. 4.

Ecstasy crystal market trends, EDRS samples 2014-2022. A) Last reported price per gram. B) Percent reporting perceived availability as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’. C) Percent reporting perceived purity as ‘high’.

Notes. In each figure the relationship between year and outcome is modelled using a generalised additive model. A) The distribution of individual price observations is summarised as a smoothed density plot; the grey dots represent individual observations; the red line indicates the median price. B & C) The dots represent the mean percent and bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

The perceived availability of ecstasy crystal increased with some fluctuation from 2014 to 2019 (Fig. 4B). In 2020, it increased again with no evidence for change compared to the existing trend (aOR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.63, 1.53). However, in 2021 and 2022 the percentage of EDRS participants reporting it as ‘easy’ or ‘very easy’ to obtain successively decreased, which was reflected in the model (2021 aOR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.25, 0.72 and 2022 aOR: 0.18; 95% CI: 0.09, 0.35).

We observed decreases in perceived purity after 2019; the adjusted odds ratios for perceiving ecstasy crystal as ‘high’ in purity relative to the existing 2014-2019 trend were 0.61 (95% CI: 0.42, 0.86), 0.30 (95% CI: 0.19, 0.46) and 0.31 (95% CI: 0.18, 0.55) for 2020, 2021 and 2022, respectively.

Similar trends were visually observed for ecstasy capsule and pill forms (Appendices H and I).

Sensitivity analyses

All results observed in the main models were similar when repeat participants were excluded (Appendix J), except the change in heroin price observed in 2020 was no longer statistically significant. All results were replicated when prices were not adjusted for inflation (Appendix K).

Discussion

Using nine years (2014-2022) of annual survey data with cross-sectional samples of people who regularly inject drugs and people who regularly use illicit stimulants, we assessed changes to illicit drug markets after the introduction of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in Australia. We observed immediate disruptions to heroin and methamphetamine markets and delayed disruptions to cocaine and ecstasy markets. By 2022, there was no longer evidence for any substantial disruption to heroin and methamphetamine market indicators compared to the pre-pandemic trend. Overall, the effect sizes observed were modest, which may be a result of small numbers of observations per jurisdiction.

Given Australia's geographic isolation and reliance on importation of drugs, the initial shifts we observed in heroin and methamphetamine market indicators were not unexpected. The immediate changes to methamphetamine markets we observed were consistent with two jurisdictional surveys that took place in Perth and Melbourne in 2020, which reported an increase in methamphetamine price (Kasun, 2022; Voce et al., 2021) and perceived decrease in quality and availability of crystal methamphetamine (Voce et al., 2021). Previous drug shortages have been accompanied by increased reports of diluted or adulterated drugs (e.g., Harris et al., 2015, Degenhardt et al., 2006), which aligns with the lower perceived purity of both heroin and methamphetamine among our sample in 2020.

Drug markets are known to be resilient to external forces (Bouchard, 2007), and we observed a return toward pre-pandemic price, perceived availability and purity for heroin and methamphetamine in 2021. This is an interesting finding given Australia did not open its international borders until late 2021, although ports remained open and there was an increase in drug seizures in the 2019/20 financial year compared to 2018/19 (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, 2021). Data from European drug markets suggested that while there was some reduction in drug trafficking between countries, localised decreases in drug availability were linked to areas with more stringent COVID-19-related restrictions (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction and Europol, 2020). In Australia, wastewater analyses of methamphetamine support this notion: there were significant impacts between April and August 2020 (when Australia's only nationwide lockdown occurred) and between April and August 2021 (when the two most populous states, New South Wales and Victoria, experienced extensive lockdowns) (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, 2022a). Between these periods and since October 2021 when restrictions subsided, methamphetamine markets showed signs of recovery. Wastewater analyses of heroin consumption displayed similar, yet less pronounced, fluctuation. Our data were largely consistent with these findings for both heroin and methamphetamine, but as our 2021 survey period mostly occurred prior to the 2021 lockdowns, we did not observe the same impacts on market indicators in 2021.

In contrast, disruptions to cocaine and ecstasy market indicators only became apparent in 2021. While it is possible that this is a result of 2020 EDRS interviews occurring immediately after the introduction of restrictions in 2020 (and earlier than 2020 IDRS interviews), there are other plausible explanations. Compared to heroin and methamphetamine use in the IDRS sample, use of cocaine and ecstasy among the EDRS sample is less frequent and more likely to be used in nightlife or festival settings (Uporova et al., 2017), with a substantial proportion of the 2020 EDRS sample reporting using ecstasy, and to a lesser extent cocaine, at a reduced frequency due to decreased opportunities for socialising (Price et al., 2022). It is possible that decreased demand for these drugs in 2020 delayed effects upon price, availability, and purity. Indeed, the World Drug Report described ecstasy as the drug most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic due to stay-at-home orders and closure of recreational venues (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022). Wastewater data displayed ‘record lows’ of ecstasy consumption between December 2021 and April 2022, although analyses suggest ecstasy consumption in Australian capital cities has been steadily decreasing since late 2019, with conjecture that some producers of ecstasy in Europe had transitioned to production of methamphetamine, impacting the supply of ecstasy to Australia prior to the pandemic (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, 2022b).

The effects we observed on cocaine markets were less pronounced than those on the ecstasy markets. Wastewater data suggest consumption of cocaine has fluctuated since the onset of the pandemic and is yet to return to pre-pandemic levels (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, 2022b). However, unlike ecstasy, global production of cocaine is at a record high (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022). With international borders open and COVID-19 public health restrictions now lifted in Australia, it is possible that demand and supply for these drugs will increase, necessitating continued monitoring of use and harms.

We are not aware of other studies that have directly compared the magnitude of immediate and longer-term effects of the pandemic on drug markets using panel data as we have done. Therefore, while international organisations have generally reported that pandemic impacts to illicit drug markets were short-lived (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2022; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2022), we cannot directly compare our findings to those of other countries. Given the variation in length and stringency of pandemic-associated border closures and restrictions globally, future comparisons will further elucidate the responsiveness of illicit drug markets to disruption.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is the long data series, which enabled testing of COVID-19 pandemic effects while taking prior trends into account, rather than reliance on year-on-year comparisons. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on illicit drug markets will be a function of the duration and stringency of ‘lockdowns’ (Giommoni, 2020) and we were able to measure immediate and longer term changes using three years of data after introduction of pandemic-related restrictions.

This study also has some limitations. Most importantly, we relied on subjective market indicator data, which may partly reflect how embedded participants are within a drug network (Dwyer & Moore, 2010). Perceived purity in particular is considered less reliable and may be affected by drug tolerance (Dwyer & Moore, 2010) or price paid (Evrard et al., 2010). However, research comparing toxicological analysis and subjective perceptions of cocaine purity found that after controlling for price paid, duration of use, and frequency of use, samples with higher cocaine content were more likely to be described as ‘good’, and those with lower content were more likely to be described as ‘average’ or ‘poor’ (Evrard et al., 2010). The data used in this study were collected from sentinel samples, so should not be considered representative of the drug market experiences of all people who use or inject drugs in Australia. However, given the consistent recruitment methodology, we can be more confident in trends observed within the samples.

The use of annual datapoints may have masked more granular fluctuations as illicit drug markets respond quickly to external forces (Bouchard, 2007). We were unable to adjust for purity in our price models and given the perceived decrease in purity of drugs, we may have underestimated the change in purity-adjusted price (Scott et al., 2015). While beyond the scope of this study, we were unable to investigate the impact of market disruptions to drug use behaviours (e.g., substance substitution) and harms (e.g., overdose); further work is required in this area once data are available. Finally, our data are subject to recall bias, although self-report of drug related indicators among people who use drugs has been shown to be sufficiently reliable and valid (Darke, 1998).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented in its potential to affect global illicit drug supply chains and local markets. We observed an immediate impact on Australian heroin and crystal methamphetamine markets in 2020, followed by a rebound towards pre-pandemic levels in 2021 and 2022. For ecstasy and cocaine, effects on market indicators were slower to be seen, potentially due to reduced demand for these drugs during lockdown, but persisted in 2022.

Ethics

Ethical approval for IDRS was granted by the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and jurisdictional HRECs; approval for EDRS was granted by the University of New South Wales HREC and jurisdictional HRECs.

Funding sources

Drug Trends and the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre are funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care under the Drug and Alcohol Program. OP receives PhD scholarships from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre. RS and AP have NHMRC Investigator Fellowships (#1197241, #1174630). PD and LD have NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowships (#1136908, #1135991). LD is also supported by a National Institute of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse grant (R01DA1104470).

Declarations of Interest

AP has received untied educational grant from Seqirus and Mundipharma for study of opioid medications. RB has received untied educational grant from Mundipharma and Indivior for study of opioid medications. LD has received untied educational grant from Seqirus, Indivior, and Mundipharma for study of opioid medications. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Chief Investigators and the broader Drug Trends team, past and present, for their contribution to the Illicit Drug Reporting System and Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System. We also thank the thousands of participants who have shared their experiences and expertise with us over the years. Finally, we thank the Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League, Students for Sensible Drug Policy, and the University of New South Wales Sydney Community Reference Panel for their review of questionnaires and input on important items.

Footnotes

Pre-registered analysis plan: https://osf.io/vy83j?view_only=a155bacd5b1a4c4c968c0cb6fddd5830

Data Availability Statement: Data were collected during interviews with consenting participants. The data are not publicly available due to ethical constraints.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.103976.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Agius P.A., Aitken C.K., Breen C., Dietze P.M. Repeat participation in annual cross-sectional surveys of drug users and its implications for analysis. BMC Research Notes. 2018;11(1):349. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3454-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya S., Ghosh A., Mishra S., Swami M.K., Prasad S., Somani A., Basu A., Sharma K., Padhy S.K., Nebhinani N., Singh L.K., Choudhury S., Basu D., Gupta R. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on substance availability, accessibility, pricing, and quality: A multicenter study from India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2022;64(5):466–472. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_864_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . ABS; Canberra: 2022. Consumer price index, Australia.https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/price-indexes-and-inflation/consumer-price-index-australia/sep-quarter-2022 Sep-quaurter-200. Retrieved October 26 2022 from. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission. (2021). Illicit drug data report 2019-2020.

- Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission National wastewater drug monitoring program - Report 16. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission National wastewater drug monitoring program - Report 17. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard M. On the resilience of illegal drug markets. Global Crime. 2007;8(4):325–344. [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins J.P., Reuter P. Illicit drug markets and economic irregularities. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. 2006;40(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: A review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;51(3):253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00028-3. discussion 267-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave D. Illicit drug use among arrestees, prices and policy. Journal of Urban Economics. 2008;63(2):694–714. [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L., Day C., Gilmour S., Hall W. The "lessons" of the Australian "heroin shortage. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2006;1:11. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietze, P., Miller, P., Matthews, S. C. S., Gilmour, S., & Collins, L. (2004). The course and consequences of the heroin shortage in Victoria. National Drug Law Enforcement Research Fund Monograph Series No. 6.

- Dietze P.M., Peacock A. Illicit drug use and harms in Australia in the context of COVID-19 and associated restrictions: Anticipated consequences and initial responses. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2020;39(4):297–300. doi: 10.1111/dar.13079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer R., Moore D. Understanding illicit drug markets in Australia: Notes towards a critical reconceptualization. The British Journal of Criminology. 2010;50(1):82–101. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction . Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2022. European drug report: Trends and developments. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction and Europol . Publications Office of the European Union; Luxembourg: 2020. EU drug markets: Impact of COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- Evrard I., Legleye S., Cadet-Tairou A. Composition, purity and perceived quality of street cocaine in France. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2010;21(5):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J., Schmutz E., Daeppen J.B., Zobel F. Evolution of the illegal substances market and substance users' social situation and health during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(9) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giommoni L. Why we should all be more careful in drawing conclusions about how COVID-19 is changing drug markets. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2020;83 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S., Mansournia M.A., Altman D.G. Sparse data bias: A problem hiding in plain sight. British Medical Journal. 2016;352:i1981. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M., Forseth K., Rhodes T. It's Russian roulette": Adulteration, adverse effects and drug use transitions during the 2010/2011 United Kingdom heroin shortage. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2015;26(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C., Hulme, S., & Ritter, A. (2020). The relationship between drug price and purity and population level harm. Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice(598), 1-26.

- Kasun R. Lisbon Addictions; Lisbon, Portugal: 2022. The impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on drug purchasing behaviours of people who use methamphetamine in Victoria, Melbourne. [Google Scholar]

- Little R.J. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83(404):1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, L. (1996). Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) trial: Ethnographic monitoring component.

- Man N., Chrzanowska A., Price O., Bruno R., Dietze P.M., Sisson S.A., Degenhardt L., Salom C., Morris L., Farrell M., Peacock A. Trends in cocaine use, markets and harms in Australia, 2003-2019. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2021;40(6):946–956. doi: 10.1111/dar.13252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man N., Sisson S.A., McKetin R., Chrzanowska A., Bruno R., Dietze P.M., Price O., Degenhardt L., Gibbs D., Salom C., Peacock A. Trends in methamphetamine use, markets and harms in Australia, 2003-2019. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2022;41(5):1041–1052. doi: 10.1111/dar.13468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdam E., Hayashi K., Dong H., Cui Z., Sedgemore K.O., Dietze P., Phillips P., Wilson D., Milloy M.J., DeBeck K. Factors associated with perceived decline in the quality of drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from community-recruited cohorts of people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2022;236 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munksgaard R., Winstock A.R., Barratt M.J., Puljevic C., Davies E., Ferris J.A. From the jungle to the street: Country-level variation and demographic correlates of cocaine prices APSAD 2022 Conference; Darwin, Australia; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Namli U. Behavioral changes among street level drug trafficking organizations and the fluctuation in drug prices before and during the covid-19 pandemic. American Journal of Qualitative Research. 2021;5(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan P.K., Phan D.H.B., Liu G. COVID-19 lockdowns, stimulus packages, travel bans, and stock returns. Finance Research Letters. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otiashvili D., Mgebrishvili T., Beselia A., Vardanashvili I., Dumchev K., Kiriazova T., Kirtadze I. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on illicit drug supply, drug-related behaviour of people who use drugs and provision of drug related services in Georgia: Results of a mixed methods prospective cohort study. Harm Reduction Journal. 2022;19(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s12954-022-00601-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar J.J., Le A., Carr T.H., Cottler L.B. Shifts in drug seizures in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2021;221 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock A., Bruno R., Gisev N., Degenhardt L., Hall W., Sedefov R., White J., Thomas K.V., Farrell M., Griffiths P. New psychoactive substances: Challenges for drug surveillance, control, and public health responses. Lancet. 2019;394(10209):1668–1684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price O., Man N., Bruno R., Dietze P., Salom C., Lenton S., Grigg J., Gibbs D., Wilson T., Degenhardt L., Chan R., Thomas N., Peacock A. Changes in illicit drug use and markets with the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions: Findings from the Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System, 2016-20. Addiction. 2022;117(1):182–194. doi: 10.1111/add.15620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott N., Caulkins J.P., Ritter A., Quinn C., Dietze P. High-frequency drug purity and price series as tools for explaining drug trends and harms in Victoria, Australia. Addiction. 2015;110(1):120–128. doi: 10.1111/add.12740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, R., Karlsson, A., King, C., Jones, F., Uporova, J., Price, O., Gibbs, D., Bruno, R., Dietze, P., Lenton, S., Salom, C., Grigg, J., Wilson, Y., Wilson, J., Daly, C., Thomas, N., Juckel, J., Degenhardt, L., Farrell, M., & Peacock, A. (2022). Australian drug trends 2022a: Key findings from the National Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) interviews. Sydney, NSW Australia: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney.

- Sutherland R., Karlsson A., King C., Jones F., Uporova J., Price O., Gibbs D., Bruno R., Dietze P., Lenton S., Salom C., Grigg J., Wilson Y., Wilson J., Daly C., Thomas N., Juckel J., Degenhardt L., Farrell M., Peacock A. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre UNSW Sydney; Sydney, NSW Australia: 2022. Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) interviews 2022: Background and methods. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland R., Uporova J., King C., Jones F., Karlsson A., Gibbs D., Price O., Bruno R., Dietze P., Lenton S., Salom C., Daly C., Thomas N., Juckel J., Agramunt S., Wilson Y., Que Noy W., Wilson J., Degenhardt L.…Peacock A. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney; Sydney, NSW Australia: 2022. Australian drug trends 2022: Key findings from the Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) interviews. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland R., Uporova J., King C., Jones F., Karlsson A., Gibbs D., Price O., Bruno R., Dietze P., Lenton S., Salom C., Daly C., Thomas N., Juckel J., Agramunt S., Wilson Y., Que Noy W., Wilson J., Degenhardt L.…Peacock A. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW Sydney; Sydney, NSW Australia: 2022. Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) interviews 2022: Background and methods. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime . United Nations Publication; 2022. World drug report 2022.http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2022.html [Google Scholar]

- Uporova J., Karlsson A., Sutherland R., Peacock A. Australian drug trends 2017: Key findings from the Ecstasy and Related Drug Reporting System (EDRS) interviews. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Voce, A., Sullivan, T., & Doherty, L. (2021). Declines in methamphetamine supply and demand in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic (Australian Institute of Criminology: Statistical Bulletin 32), Issue.

- Weatherburn D., Jones C., Freeman K., Makkai T. Supply control and harm reduction: Lessons from the Australian heroin 'drought'. Addiction. 2003;98(1):83–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welle-Strand G.K., Skurtveit S., Clausen T., Sundal C., Gjersing L. COVID-19 survey among people who use drugs in three cities in Norway. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S. (2012). mgcv: Mixed GAM computation vehicle with GCV/AIC/REML smoothness estimation.

- Zolopa C., Hoj S., Bruneau J., Meeson J.S., Minoyan N., Raynault M.F., Makarenko I., Larney S. A rapid review of the impacts of "Big Events " on risks, harms, and service delivery among people who use drugs: Implications for responding to COVID-19. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2021;92 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.