Key Points

Question

Is better cardiovascular health associated with lower risk of depressive symptoms?

Findings

In this cohort study including 6980 participants, better baseline cardiovascular health and improvement in cardiovascular health over 7 years based on a composite metric were each associated with a lower risk of incident depressive symptoms and lower risk of unfavorable depressive symptoms trajectories.

Meaning

In this study, cardiovascular health metrics were indicators of potential risk of clinically relevant depressive symptoms.

This cohort study evaluates whether better baseline cardiovascular health and improvement of cardiovascular health over time are associated with a lower risk of both incident depressive symptoms and unfavorable trajectories of depressive symptoms.

Abstract

Importance

Cardiovascular health may be used for prevention of depressive symptoms. However, data on the association of cardiovascular health across midlife with depressive symptoms are lacking.

Objective

To evaluate whether better baseline cardiovascular health and improvement of cardiovascular health over time are associated with a lower risk of both incident depressive symptoms and unfavorable trajectories of depressive symptoms.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Participants without depressive symptoms were included from a prospective community-based cohort in France (GAZEL cohort). Cardiovascular health examinations occurred in 1990 and 1997 and assessment of depressive symptoms in 1997 and every 3 years thereafter until 2015. Data were analyzed from January to October 2022.

Exposures

Number of cardiovascular health metrics (smoking, body mass index, physical activity, diet, blood pressure, glucose, and cholesterol) at an intermediate or ideal level in 1997 (range, 0-7) and 7-year change in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome was incident depressive symptoms (20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale [CES-D] score of 17 or greater in men or 23 or greater in women); secondary outcome was trajectories of depressive symptoms scores. Trajectories included consistently low scores, moderately elevated scores, low starting then increasing scores, moderately high starting, increasing, then remitting scores, and moderately high starting then increasing scores.

Results

Of 6980 included patients, 1671 (23.9%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 53.3 (3.5) years. During a follow-up spanning 19 years after 1997, 1858 individuals (26.5%) had incident depressive symptoms. Higher baseline cardiovascular health in 1997 and improvement in cardiovascular health over 7 years were each associated with lower risk of depressive symptoms (odds ratio [OR] per additional metric at intermediate or ideal level at baseline, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.84-0.91; OR per 1 higher metric at intermediate or ideal level over 7 years, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86-0.96). Also, better cardiovascular health was associated with lower risk of unfavorable depressive symptoms trajectories. Compared with the consistently low score trajectory, the lowest risks were observed for the low starting then increasing score trajectory (OR per additional metric at intermediate or ideal level at baseline, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.64-0.76; OR per 1 higher metric at intermediate or ideal level over 7 years, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.68-0.79) and the moderately high starting then increasing score trajectory (OR per additional metric at intermediate or ideal level at baseline, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.64-0.79; OR per 1 higher metric at intermediate or ideal level over 7 years, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.64-0.77).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this prospective community-based cohort study of adults, higher cardiovascular health was associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms over time. Elucidating which set of cardiovascular factors may affect depression risk could be important for prevention.

Introduction

Major depression and clinically relevant depressive symptoms are common among older individuals, with an estimated prevalence of 2% and 10% to 15%, respectively,1 and are associated with lower quality of life2 and 1.5- to 2-fold higher mortality.3,4 However, current antidepressant medications are not sufficiently effective in older patients.5,6,7 A focus on prevention is, therefore, key to reduce the burden of late-life depression. Vascular risk factors are increasingly recognized as potential contributors to the development of late-life depression and, thus, as potential targets for early preventive therapies.8

The American Heart Association developed a simple 7-item tool consisting of 4 behavioral metrics (nonsmoking and ideal levels of body mass index [BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared], physical activity, and dietary habits) and 3 biological metrics (ideal levels of blood pressure, blood glucose, and total cholesterol) for promoting ideal cardiovascular health.9 This construct has also been suggested as a tool for the promotion of brain health.10 Better cardiovascular health has been associated with lower prevalence of magnetic resonance imaging markers of cerebral vascular disease, higher brain volumes, slower cognitive decline, and lower risk of dementia.10 However, data on the association between cardiovascular health and risk of depressive symptoms is limited. Most studies were cross-sectional in design,11 precluding any conclusions about the directions of the association. To our knowledge, 3 prospective studies to date12,13,14 have evaluated the association between baseline cardiovascular health and presence of depressive symptoms at follow-up, but these studies did not evaluate change in cardiovascular health and had a relatively short follow-up duration (4 years or less). Furthermore, these studies assessed depressive symptoms at only 112,13 or 214 follow-up examinations and did not investigate trajectories of depressive symptoms. Yet there is a large intraindividual variability in the longitudinal course of depressive symptoms in individuals, including trajectories with more unfavorable outcomes, eg, a trajectory with continuously increasing depressive symptoms over time.15,16

Using serial examinations from a large community-based cohort study with examinations of depressive symptoms spanning 19 years, we sought to evaluate whether better baseline cardiovascular health and improvement of cardiovascular health in 7 years before baseline were each associated with lower risk of incident clinically relevant depressive symptoms and lower risk of unfavorable trajectories of depressive symptoms.

Methods

The GAZEL cohort is a prospective cohort study aiming to address the determinants of several chronic noncommunicable diseases in adults, with an emphasis on occupational factors.17 A total of 20 625 adults (15 011 men and 5614 women aged 35 to 50 years) originally employed by Electricité de Gaz France, the French national gas and electric company, were enrolled in 1989. Race and ethnicity were determined by investigators. Participants were mainly White and lived throughout France in various settings, ranging from rural areas to urban centers. Self-administrated questionnaires at enrollment and every year thereafter were used to obtain information about medical history, drug treatment, socioeconomic data, and lifestyle and cardiovascular factors. In addition, a comprehensive update included data from the Électricité de France Human Resources Department, the company’s medical insurance program, and the Department of Occupational Medicine. The attrition rate in the study was low; approximately 75% of participants responded to the study questionnaire every year. Cardiovascular health metrics were determined at enrollment and in 1997. Depressive symptoms were assessed by self-administrated questionnaires starting in 1997 and approximately every 3 years thereafter up to 2015 (Figure 1). We did a complete-case analysis in people with all cardiovascular health metrics measured in both 1990 and 1997, free of clinically relevant depressive symptoms and coronary heart disease in 1997, and with data on depressive symptoms on at least 1 follow-up examination (Figure 1). Coronary heart disease events were identified with linkage to patient records and yearly self-administrated questionnaires and were validated by 2 trained independent investigators, as described previously.18 The study was approved by the Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté and by the Ethics Evaluation Committee of the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale. All participants provided written informed consent. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

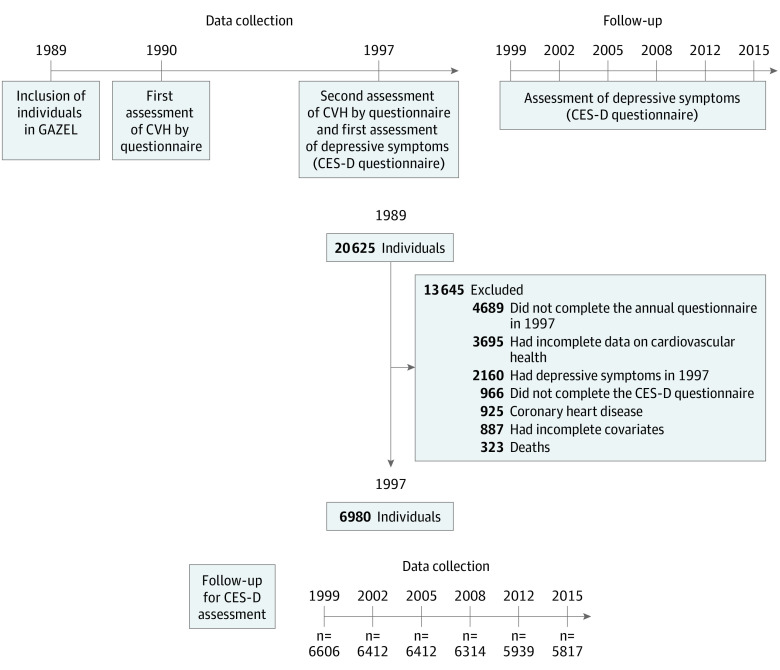

Figure 1. Study Design and Flowchart of Selection Process.

The total study sample included 6980 individuals with data on clinically relevant depressive symptoms on at least 1 follow-up examination. Data on clinically relevant depressive symptoms were available in at least 5 follow-up examination rounds after 1997 in 6343 individuals (90.9%). A total of 3695 individuals had missing data on 1 or more cardiovascular health (CVH) metrics in 1990 and/or 1997. Among these individuals, data were missing in 1990 in 2264 individuals on smoking (n = 1153), body mass index (n = 1174), physical activity (n = 1441), healthy diet (n = 1153), and any of the biological metrics (high blood pressure, hyperglycemia, or dyslipidemia; n = 863). In addition, data were missing in 1997 in 3139 individuals on smoking (n = 229), body mass index (n = 127), physical activity (n = 1601), healthy diet (n = 2087), and any of the biological metrics (high blood pressure, hyperglycemia, or dyslipidemia; n = 321). A total of 2658 individuals had missing data on all CVH metrics in 1990 or 1997. CES-D indicates 20-Item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale.

Cardiovascular Health Metrics

The 7 cardiovascular health metrics (Life’s Simple 7) were assessed in 1990 and 1997 and defined according to the American Heart Association criteria using self-reported data, as detailed in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. Intermediate and ideal levels for the behavioral metrics corresponds to never smoking or being an ex-smoker, a BMI less than 30, engagement in sports activity for more than 1 hour weekly, and 2 or more portions of fish per week and/or 1 portion of vegetables and fruits every day (data on fibers, salt consumption and sweetened beverages are unavailable). Intermediate and ideal levels for the biological metrics corresponds to the absence of any medication or diagnosis for hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

Outcome

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the French validated version of the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D).18,19 Depressive symptoms were assessed in total 7 times, starting from 1997 and every 3 years thereafter up to 2015. Clinically relevant depressive symptoms were defined as a CES-D score of 17 or more in men and 23 or more in women, as used previously.18 Data on use of antidepressant medications were only available from 2007 onwards via the French National claims data.20 Therefore, inclusion of use of antidepressant medication in the outcome definition was done in an additional analysis only.

Covariates

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, occupational level (low, manual and clerical or unskilled work; medium, technical or skilled work; high, managers) and education (primary school, lower secondary school [up to age 16 years], and university or higher university degree). Occupational level and education were obtained from the employer’s human resources files at baseline. No data on incident stroke were available. We also used cardiovascular health status in 1990 (number of metrics at an intermediate or ideal level) as a covariate in the analyses on 7-year change in cardiovascular health.

Statistical Analysis

To calculate trajectories of depressive symptoms, we used a group-based trajectory modeling approach, which is based on a nonparametric mixed model.21 We estimated the best-fitting number of trajectories based on a minimum bayesian information criterion while maintaining at least 50 participants in each trajectory. Of the initially 8 trajectories obtained, we grouped them into 5 groups for clinical interpretation. The original 8 trajectories and the grouping strategy are detailed in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

We used mixed-model logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for the association between cardiovascular health in 1997 and 7-year change in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997 and presence of depressive symptoms at any of the follow-up examinations after 1997 (primary outcome). Mixed modeling is a method for longitudinal data analysis that takes into account the correlation of repeated measurements within individuals over time.20 In addition, we used multinomial logistic regression to evaluate the association between cardiovascular health in 1997 or change in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997 and trajectories of depressive symptoms (secondary outcome).

Cardiovascular health in 1997 was evaluated per additional metric at intermediate or ideal level (continuous score) and as the absolute number of metrics at intermediate or ideal level (categorical score), with 0 to 1 metrics at intermediate or ideal level as the reference. Seven-year change in cardiovascular health was examined per increase of 1 additional metric at intermediate or ideal level (continuous change). The log-linearity assumption was verified by comparing the likelihood ratio of models with the number of ideal cardiovascular health metrics alone and models additionally including a quadratic term on the number of ideal cardiovascular health metrics. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, and occupation. Analyses on 7-year change in cardiovascular health were also adjusted for cardiovascular health status in 1990.

We examined interactions with age and sex, but none were statistically significant (all P values for interaction >.10). Results are therefore reported without stratification for these factors.

We did several additional analyses to test the robustness of our findings. We repeated the analyses with incident depressive symptoms as the outcome with the following changes: (1) after excluding individuals with incident coronary heart disease to address residual confounding; (2) among individuals with complete data on depressive symptoms at all follow-up examinations to evaluate the effect of bias due to missing follow-up data; (3) after multiple imputation of missing data on covariates and cardiovascular health metrics (fully conditional specification method under SAS MI procedure; 10 imputations) to evaluate the effect of missing data; (4) to evaluate whether the results depended on the definition of the primary outcome using alternative cutoff values to define incident depressive symptoms, ie, a CES-D score of 17 or more or of 23 or more in both men and women, and with the outcome defined with the same CES-D cutoff as in the main analysis or the use of antidepressant medication; (5) with exclusion of individuals with depressive symptoms within the first 3 years of follow-up to address reverse causality; (6) with additional adjustments for adverse childhood life events (assessed with adverse childhood life events questionnaire22), psychosocial work environment (assessed with effort-reward imbalance questionnaire23), and psychosocial factors at work (Karasek Job Content Questionnaire24) to evaluate confounding due to these factors; (7) using the individual cardiovascular health metrics in 1997 and 7-year change in each cardiovascular health metric between 1990 and 1997 as the main determinants, with poor level or consistently poor level over time, respectively, of each metric as the reference; and (8) with continuous CES-D scores as the outcome to evaluate the association with change in any depressive symptoms after baseline.

Analysis of variance, t tests, and χ2 tests were used, as appropriate, to calculate P values. Significance was set at P < .05, and all P values were 2-tailed. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

The study population included 6980 participants without depressive symptoms or coronary heart disease in 1997 (Figure 1). Individuals excluded for the analysis due to missing data (n = 10 239) compared with those included were more often women and more often had a lower education and occupation (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The characteristics of the total study population measured in 1997 and according to presence of depressive symptoms at follow-up is shown in Table 1. Of 6980 included patients, 1671 (23.9%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 53.3 (3.5) years. Data on depressive symptoms were available in at least 5 follow-up examination rounds after 1997 in 6343 individuals (90.9%).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Total Study Population in 1997 in Participants With and Without Incident Depressive Symptoms During Follow-up.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value for difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total study population (N = 6980) | Individuals without incident depressive symptoms (n = 5122)a | Individuals with ≥1 episode of depressive symptoms at follow-up (n = 1858)a | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 53.3 (3.5) | 53.4 (3.5) | 53.1 (3.6) | .01 |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 5309 (76.1) | 3941 (76.9) | 1368 (73.6) | .004 |

| Women | 1671 (23.9) | 1181 (23.1) | 490 (26.4) | |

| Education levelb | ||||

| Low | 301 (4.3) | 220 (4.3) | 81 (4.4) | .64 |

| Intermediate | 4711 (67.5) | 3473 (67.8) | 1238 (66.6) | |

| High | 1968 (28.2) | 1429 (27.9) | 539 (29.0) | |

| Occupationc | ||||

| Low | 373 (5.3) | 271 (5.3) | 102 (5.5) | .20 |

| Medium | 4509 (64.6) | 3281 (64.1) | 1228 (66.1) | |

| High | 2098 (30.1) | 1570 (30.7) | 528 (28.4) | |

| Cardiovascular health metrics at intermediate or ideal leveld | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.2) | .002 |

| 0-1 | 30 (0.4) | 16 (0.3) | 14 (0.8) | .01 |

| 2 | 177 (2.5) | 123 (2.4) | 54 (2.9) | |

| 3 | 616 (8.8) | 447 (8.7) | 169 (9.1) | |

| 4 | 1540 (22.1) | 1105 (21.6) | 435 (23.4) | |

| 5 | 2481 (35.5) | 1816 (35.5) | 665 (35.8) | |

| 6-7 | 2136 (30.6) | 1615 (31.5) | 521 (28.0) | |

Depressive symptoms were defined as a 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale score of 17 or more in men and 23 or more in women.

Education level defined as low (primary school), intermediate (lower secondary school [up to age 16 years]), and high (university or higher university degree).

Occupational level defined as low (manual and clerical or unskilled work), medium (technical or skilled work), and high (managers).

The cardiovascular health metrics included nonsmoking and intermediate or ideal levels of body weight, physical activity, diet, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, and total cholesterol.

Cardiovascular Health and Incident Depressive Symptoms

During follow-up after 1997, 1858 individuals (26.5%) had depressive symptoms at 1 or more examination rounds. Better cardiovascular health in 1997 was associated with a 13% reduced risk of depressive symptoms per additional metric at an intermediate or ideal level (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.84-0.91). The risk of depressive symptoms was progressively smaller in individuals who had a higher number of metrics at an intermediate or ideal level compared with individuals with 0 or 1 metrics at an intermediate or ideal level. Among individuals with 6 to 7 metrics at an intermediate or ideal level, the odds of depressive symptoms was 0.36 (95% CI, 0.20-0.66). In addition, 7-year improvement in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997 was associated with a 9% reduced risk of depressive symptoms per 1 increase in the number of metrics at an intermediate or ideal level (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.86-0.96) (Table 2).

Table 2. Associations of Cardiovascular Health and 7-Year Change in Cardiovascular Health With Incident Depressive Symptomsa,b.

| Measure | Participants, No. | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular health in 1997 | ||

| Per 1 additional intermediate or ideal metric | NA | 0.87 (0.84-0.91) |

| Intermediate or ideal metrics, No. | ||

| 0-1 | 30 | 1 [Reference] |

| 2 | 177 | 0.62 (0.32-1.19) |

| 3 | 616 | 0.54 (0.29-1.00) |

| 4 | 1540 | 0.50 (0.27-0.91) |

| 5 | 2481 | 0.41 (0.22-0.74) |

| 6-7 | 2136 | 0.36 (0.20-0.66) |

| Change in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997b | ||

| Per 1 higher intermediate or ideal metric over time | NA | 0.91 (0.86-0.96) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Odds ratios were adjusted for age, sex, education, and occupation.

Analyses on 7-year change in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997 were additionally adjusted for number of metrics at intermediate or ideal level in 1990.

Cardiovascular Health and Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms

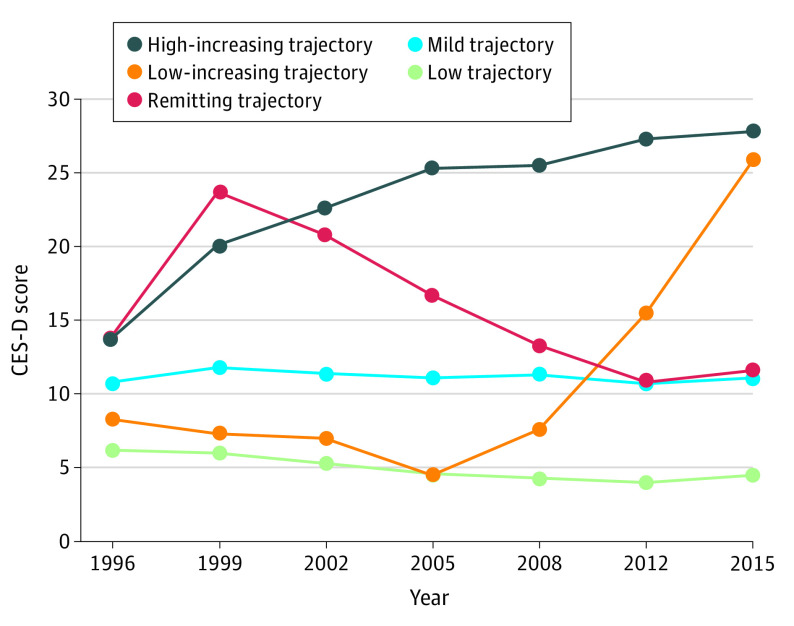

The 5 trajectories of depressive symptoms considered were characterized by (1) maintaining a low CES-D score throughout the follow-up (low; 2868 [41.1%]), (2) maintaining a moderately elevated CES-D score throughout follow-up (mild; 3379 [48.4%]), (3) having low starting CES-D scores that then increased (low-increasing; 57 [0.8%]), (4) having moderately high starting CES-D scores that increased and then remitted (remitting; 585 [8.4%]), and (5) having moderately high starting CES-D scores that increased (high-increasing; 91 [1.3%]) (Figure 2). The baseline characteristics according to the trajectory of depressive symptoms are shown in eTable 3 in Supplement 1. Using the low trajectory group as the reference, we found that higher cardiovascular health in 1997 and 7-year increase in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997 were each associated with a lower risk of all 4 other trajectories, except that 7-year change in cardiovascular health was not associated with a lower risk of the remitting trajectory (Table 3). The lowest risks were observed for the low-increasing trajectory (OR per additional metric at intermediate or ideal level at baseline, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.64-0.76; OR per 1 higher metric at intermediate or ideal level over 7 years, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.68-0.79) and high-increasing trajectory (OR per additional metric at intermediate or ideal level at baseline, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.64-0.79; OR per 1 higher metric at intermediate or ideal level over 7 years, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.64-0.77) (Table 3).

Figure 2. Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms From 1997 to 2015.

The figure shows trajectories of mean 20-Item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D) scores over 19 years from 6980 individuals, with up to 7 measures of depressive symptoms. The 5 trajectories of depressive symptoms considered were characterized by (1) maintaining a low CES-D score throughout the follow-up (low; 2868 [41.1%]), (2) maintaining a moderately elevated CES-D score throughout follow-up (mild; 3379 [48.4%]), (3) having low starting CES-D scores that then increased (low-increasing; 57 [0.8%]), (4) having moderately high starting CES-D scores that increased and then remitted (remitting; 585 [8.4%]), and (5) having moderately high starting CES-D scores that increased (high-increasing; 91 [1.3%]).

Table 3. Associations of Cardiovascular Health and 7-Year Change in Cardiovascular Health With Trajectories of Depressive Symptomsa,b.

| Trajectory | Participants, No. | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular health in 1997 (per additional intermediate or ideal metric) | Change in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997 (per 1 higher intermediate or ideal metric) | ||

| Low | 2868 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Mild | 3379 | 0.89 (0.88-0.91) | 0.93 (0.91-0.95) |

| Low-increasing | 57 | 0.70 (0.64-0.76) | 0.71 (0.64-0.79) |

| Remitting | 585 | 0.91 (0.88-0.94) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) |

| High-increasing | 91 | 0.73 (0.68-0.79) | 0.71 (0.64-0.77) |

The 5 trajectories of depressive symptoms considered were characterized by (1) maintaining a low 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D) score throughout the follow-up (low), (2) maintaining a moderately elevated CES-D score throughout follow-up (mild), (3) having low starting CES-D scores that then increased (low-increasing), (4) having moderately high starting CES-D scores that increased and then remitted (remitting), and (5) having moderately high starting CES-D scores that increased (high-increasing).

Analyses on 7-year change in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997 were additionally adjusted for number of metrics at intermediate or ideal level in 1990.

Odds ratios were adjusted for age, sex, education, and occupation.

Additional Analyses

The results of the main analysis on incident depressive symptoms were similar when we repeated the analyses after excluding individuals with incident coronary heart disease, among individuals with complete data on depressive symptoms at all follow-up examinations, after multiple imputation, with incident depressive symptoms (defined as a CES-D score of 17 or more or 23 or more in both men and women, or a CES-D score of 17 or more in men and 23 or more in women or the use of antidepressant medications); with exclusion of individuals with depressive symptoms within the first 3 years of follow-up; and after additional adjustment for adverse childhood life events, psychosocial work environment, or psychosocial factors at work (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). The analyses with the individual cardiovascular health metrics showed that an intermediate or ideal level in 1997 was associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms for the metrics smoking, physical activity, high blood pressure, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). In addition, a lower risk of incident depressive symptoms was observed for categories of change for smoking (for poor to intermediate or ideal level and consistently intermediate or ideal level), BMI (intermediate or ideal to poor level and consistently intermediate or ideal level), physical activity (consistently intermediate or ideal level), high blood pressure (consistently intermediate or ideal level), and dyslipidemia (consistently intermediate or ideal level) (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Better cardiovascular health in 1997 (β per additional metric at intermediate or ideal level, −0.35; 95% CI, −0.44 to −0.26) and higher 7-year change in cardiovascular health between 1990 and 1997 (β per 1 increase in the number of metrics at intermediate or ideal level over time, −0.27; [95% CI, −0.38 to −0.16) were associated with lower continuous CES-D scores over time.

Discussion

In this analysis using data from a large community-based study, a higher cardiovascular health score in midlife and a 7-year increase in a cardiovascular health score were each associated with a lower risk of both incident clinically relevant depressive symptoms and unfavorable trajectories of depressive symptoms. Three previous studies, the Framingham Heart Study (N = 2023),12 the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study (N = 5110),14 and the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil; N = 9214),13 evaluated the association between baseline cardiovascular health based on objectively measured risk factor data and presence of depressive symptoms at follow-up. Consistent with our findings, these studies found that a higher cardiovascular health score was associated with lower odds of depressive symptoms at follow-up. The present study extends these studies as it evaluated depressive symptoms with greater precision, ie, 6 follow-up examinations spanning 19 years compared with 112,13 or 214 follow-up examinations spanning 4 years or less. Furthermore, previous studies did not examine trajectories of depressive symptoms and evaluated only baseline cardiovascular health but not change in cardiovascular health before baseline.

Our results suggest that cardiovascular health metrics are indicators of potential risk of depressive symptoms. Individuals who improved their cardiovascular health before baseline had lower risk of incident depressive symptoms and less often had an unfavorable trajectory of depressive symptoms. The results of the additional analyses suggest that the study findings are less likely to be explained by residual confounding due to coronary heart disease or bias due to missing data or reverse causality and do not depend on the definition of the primary outcome. This enhances the robustness of the results.

Thereby, this study suggests that improving cardiovascular health throughout life may be related to a lower risk of depressive symptoms. Elucidating which set of cardiovascular risk factors may influence depression risk could be important for prevention.

Our findings are biologically plausible. The pathophysiology of late-life depressive symptoms is likely determined by a combination of psychosocial risk factors and multiple other etiologies, including (micro)vascular pathology, hypoxia, inflammation, and oxidative stress.25,26 Given the multifactorial nature of late-life depression, it has been suggested that interventions targeting several risk factors and mechanisms simultaneously may be required for optimal preventive effects.27 The 7 selected cardiovascular health metrics (nonsmoking and intermediate or ideal levels of BMI, physical activity, dietary habits, blood pressure, blood glucose, and total cholesterol) have each been associated with 1 or more of these etiologies.25,26

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the observational design does not allow us to draw causal conclusions. Second, depressive symptoms were assessed by questionnaire only, and no data were available on a diagnosis of major depression. Also, use of antidepressant medication was only available from 2007 onwards. Nevertheless, questionnaire measures of depressive symptoms strongly correlate with a diagnosis of major depression.19,20 Additionally, presence of clinically relevant depressive symptoms, even in the absence of a diagnosis of major depression, is associated with higher mortality.3,4 Third, presence of depressive symptoms was known approximately every 3 years on average at examinations waves, but no information on depressive symptoms was available in the intervals between the examinations (ie, the time to event is interval-censored). This may have led to an underestimation of the association between higher cardiovascular health and lower risk of depressive symptoms. Fourth, cardiovascular health was determined by self-reported data. Although a recent study showed that self-reported cardiovascular health may represent a reliable and valid alternative to measured cardiovascular health,28 this may increase the risk of measurement bias. Incorrect assessment of cardiovascular health might lead to an underestimation of the reported associations. Fifth, no data were available on stroke and a lifetime history of depression. We therefore cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding due to these factors. This may have led to an overestimation of the reported associations. Sixth, the sample was comprised of middle-aged and older individuals without coronary heart disease, who were mostly White and consisted of public sector employees. Furthermore, individuals excluded from the analysis had a lower education and occupation grade (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). This limits the generalizability of our findings to other racial, ethnic, or age groups or groups with lower socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

In conclusion, higher cardiovascular health and 7-year improvement in cardiovascular health were each associated with a lower risk of clinically relevant depressive symptoms and a lower risk of unfavorable depressive symptoms trajectories.

eMethods. Calculation of Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms

eTable 1. Definition of Cardiovascular Health Metrics

eTable 2. Characteristics Measured in 1997 of Included and Excluded Individuals

eTable 3. Characteristics of the Total Study Population in 1997 According to the Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms

eTable 4. Associations of Cardiovascular Health (in 1997) and 7-Year Change in Cardiovascular Health (Between 1990 and 1997) With Incident Depressive Symptoms—Results of Additional Analysis

eTable 5. Associations of Individual Cardiovascular Health Metrics (Measured in 1997) With Incident Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms

eTable 6. Associations of 7-Year Change in Each Cardiovascular Health Metric (Between 1990 and 1997) With Incident Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Kok RM, Reynolds CF III. Management of depression in older adults: a review. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2114-2122. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chachamovich E, Fleck M, Laidlaw K, Power M. Impact of major depression and subsyndromal symptoms on quality of life and attitudes toward aging in an international sample of older adults. Gerontologist. 2008;48(5):593-602. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.5.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barefoot JC, Schroll M. Symptoms of depression, acute myocardial infarction, and total mortality in a community sample. Circulation. 1996;93(11):1976-1980. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.11.1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penninx BW, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJ, van Eijk JT, van Tilburg W, Beekman AT. Minor and major depression and the risk of death in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(10):889-895. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tedeschini E, Levkovitz Y, Iovieno N, Ameral VE, Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Efficacy of antidepressants for late-life depression: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1660-1668. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calati R, Salvina Signorelli M, Balestri M, et al. Antidepressants in elderly: metaregression of double-blind, randomized clinical trials. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1-3):1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas A, O’Brien JT. Management of late-life depression: a major leap forward. Lancet. 2015;386(10011):2374-2375. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00304-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jellinger KA. Pathomechanisms of vascular depression in older adults. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;23(1):308. doi: 10.3390/ijms23010308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. ; American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task Force and Statistics Committee . Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorelick PB, Furie KL, Iadecola C, et al. ; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association . Defining optimal brain health in adults: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2017;48(10):e284-e303. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogunmoroti O, Osibogun O, Spatz ES, et al. A systematic review of the bidirectional relationship between depressive symptoms and cardiovascular health. Prev Med. 2022;154:106891. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams S, Conner S, Himali JJ, et al. Vascular risk factor burden and new-onset depression in the community. Prev Med. 2018;111:348-350. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunoni AR, Szlejf C, Suemoto CK, et al. Association between ideal cardiovascular health and depression incidence: a longitudinal analysis of ELSA-Brasil. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(6):552-562. doi: 10.1111/acps.13109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.España-Romero V, Artero EG, Lee DC, et al. A prospective study of ideal cardiovascular health and depressive symptoms. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(6):525-535. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2013.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agustini B, Lotfaliany M, Mohebbi M, et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms in older adults and associated health outcomes. Nat Aging. 2022;2(4):295-302. doi: 10.1038/s43587-022-00203-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musliner KL, Munk-Olsen T, Eaton WW, Zandi PP. Heterogeneity in long-term trajectories of depressive symptoms: patterns, predictors and outcomes. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:199-211. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg M, Leclerc A, Bonenfant S, et al. Cohort profile: the GAZEL cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(1):32-39. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamieh N, Meneton P, Zins M, et al. Hostility, depression and incident cardiac events in the GAZEL cohort. J Affect Disord. 2020;266:381-386. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morin AJ, Moullec G, Maïano C, Layet L, Just JL, Ninot G. Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in French clinical and nonclinical adults. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2011;59(5):327-340. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2011.03.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bezin J, Duong M, Lassalle R, et al. The national healthcare system claims databases in France, SNIIRAM and EGB: powerful tools for pharmacoepidemiology. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(8):954-962. doi: 10.1002/pds.4233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones BL, Nagin DS. Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociol Methods Res. 2007;35(4):542-571. doi: 10.1177/0049124106292364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Airagnes G, Lemogne C, Hoertel N, Goldberg M, Limosin F, Zins M. Childhood adversity and depressive symptoms following retirement in the GAZEL cohort. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;82:80-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegrist J, Starke D, Chandola T, et al. The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(8):1483-1499. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00351-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niedhammer I. Psychometric properties of the French version of the Karasek Job Content Questionnaire: a study of the scales of decision latitude, psychological demands, social support, and physical demands in the GAZEL cohort. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2002;75(3):129-144. doi: 10.1007/s004200100270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexopoulos GS. Mechanisms and treatment of late-life depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):188. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0514-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Empana JP, Boutouyrie P, Lemogne C, Jouven X, van Sloten TT. Microvascular contribution to late-onset depression: mechanisms, current evidence, association with other brain diseases, and therapeutic perspectives. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;90(4):214-225. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almeida OP. Prevention of depression in older age. Maturitas. 2014;79(2):136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreira AD, Gomes CS, Machado IE, Malta DC, Felisbino-Mendes MS. Cardiovascular health and validation of the self-reported score in Brazil: analysis of the National Health Survey. Cien Saude Colet. 2020;25(11):4259-4268. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320202511.31442020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Calculation of Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms

eTable 1. Definition of Cardiovascular Health Metrics

eTable 2. Characteristics Measured in 1997 of Included and Excluded Individuals

eTable 3. Characteristics of the Total Study Population in 1997 According to the Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms

eTable 4. Associations of Cardiovascular Health (in 1997) and 7-Year Change in Cardiovascular Health (Between 1990 and 1997) With Incident Depressive Symptoms—Results of Additional Analysis

eTable 5. Associations of Individual Cardiovascular Health Metrics (Measured in 1997) With Incident Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms

eTable 6. Associations of 7-Year Change in Each Cardiovascular Health Metric (Between 1990 and 1997) With Incident Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptoms

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement