Abstract

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a novel heterogenous group of immunosuppressive cells derived from myeloid progenitors. Their role is well known in tumors and autoimmune diseases. In recent years, the role and function of MDSCs during reproduction have attracted increasing attention. Improving the understanding of their strong association with recurrent implantation failure, pathological pregnancy, and neonatal health has become a focus area in research. In this review, we focus on the interaction between MDSCs and other cell types (immune and non-immune cells) from embryo implantation to postpartum. Furthermore, we discuss the molecular mechanisms that could facilitate the therapeutic targeting of MDSCs. Therefore, this review intends to encourage further research in the field of maternal–fetal interface immunity in order to identify probable pathways driving the accumulation of MDSCs and to effectively target their ability to promote embryo implantation, reduce pathological pregnancy, and increase neonatal health.

Keywords: myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), maternal–fetal immune tolerance, embryo implantation, pregnancy complications, newborn

1. Introduction

Recently, a population of immature cells derived from myeloid progenitors, i.e., myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), has entered the research spotlight (1). The molecular phenotypes of MDSCs are CD11b and Gr1 in mice, whereas it is HLA-DRlow/−CD33+ in humans. These can be subdivided into the monocytic and granulocytic subtypes (M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs, respectively). Traditionally, they are defined as CD11b+Ly6ChighLy6G− and CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Clow in mice and CD11b+CD33+CD14+HLA-DR−/low and CD11b+CD33+CD15+/CD66+HLA-DR− in humans, respectively (2). Recently, a number of novel markers and subsites of MDSCs have emerged, as shown in Table 1 . MDSCs exhibit significant heterogeneity because M-MDSCs and G-MDSCs can further differentiate into myeloid cells. Furthermore, it is difficult to distinguish them from mature monocytes and granulocytes based on immune molecular markers (30). In addition, a great deal of attention has been focused on the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs in tumors, autoimmune diseases, organ transplantation, and infectious diseases (31–34). In tumors, MDSCs inhibit the antitumor functions of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells and promote tumor progression by accelerating angiogenesis and cell invasion (2, 35, 36). Moreover, the proportion of MDSCs is closely associated with the clinical outcomes and therapeutic effects in patients with cancer (37). Although MDSCs are short-lived cells, they play crucial roles in many diseases.

Table 1.

Phenotypes of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in mice and humans.

| G-MDSCs | M-MDSCs | Other types of MDSCs | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | Human | Mice | Human | Mice | Human | ||

| Traditional markers | CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Clow | CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6Chigh | (2–4) | ||||

| CD11b+CD33+CD14−CD15+CD66+HLA-DRlow/− | CD11b+CD33+CD14+CD15−CD66−HLA-DRlow/− | (2, 4–6) | |||||

| Novel markers | Side scatter (SSC) | (7, 8) | |||||

| CD244 | (9) | ||||||

| CD84 | (10) | ||||||

| CD36 | (11) | ||||||

| FATP2 | (12) | ||||||

| CD13 | (13, 14) | ||||||

| CD16 | (15) | ||||||

| LOX1 | (16) | ||||||

| CD49d (VLA4) | (17) | ||||||

| CD115 | (18) | ||||||

| CCR2 | (19) | ||||||

| CD11c | (20, 21) | ||||||

| IL-4Rα (CD124) | (22) | ||||||

| CD68+CD163+ | (23) | ||||||

|

Early-stage MDSCs (e-MDSCs)

CD11b+Gr-1−F4/80−MHCII− |

(24) | ||||||

| e-MDSCs Lin−CD3−CD14−CD15−CD19−CD56−CD33+HLA-DR− | (25) | ||||||

|

MDSC-like fibrocytes

Collagen type-1+CD15+CD45dimCD34−CD14−/CD11chiCD123−CD14− |

(26, 27) | ||||||

|

Fibrocytic-MDSCs (f-MDSCs)

CD11b+Gr-1+FAP+ |

(28) | ||||||

|

f-MDSCs

CD33+IL-4Rα+ |

(28, 29) | ||||||

G-MDSCs, granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells; M-MDSCs, monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

The function of MDSCs during reproduction remains controversial. Embryo implantation, including the balance of immune cells at the maternal–fetal interface, reconstruction of the endometrial spiral arteries, and moderate invasion of trophoblasts, is a prerequisite for a successful pregnancy. Several studies have described how maternal–fetal tolerance is enhanced by accumulating MDSCs to suppress T-cell responses (38–40). Furthermore, the proportion of MDSCs was decreased in spontaneously aborting mice compared with controls, whereas their depletion resulted in the increased cytotoxicity of decidual NK cells (41). Even in infertile couples, the ratio of MDSCs in the peripheral blood of women who undergo in vitro fertilization (IVF) is considered an essential factor in predicting the outcomes of pregnancy (42, 43). These findings might provide new insights into immune-related miscarriage and IVF failure. In addition, several studies have further demonstrated the accumulation and augmentation of MDSCs in newborn humans and mice (44–46). There is growing acceptance that MDSCs manipulate the maternal–fetal immune microenvironment to promote and sustain embryo implantation, protect the fetus during gestation, and keep the newborn healthy.

In this review, we discuss the evidence concerning the association of MDSCs with embryo implantation, pregnancy complications, and newborn health and explore the potential relationship between MDSCs and the maternal–fetal immune microenvironment.

2. MDSCs in embryo implantation

The first steps to a successful pregnancy are embryo localization, adhesion, and invasion of the endometrium. As a type of semi-allogeneic transplantation, the fetal trophoblasts in the maternal–fetal interface interact with the maternal decidual stromal cells, decidual glandular epithelial cells, and numerous immune cells (47, 48). The maternal–fetal immune microenvironment plays a decisive role during these events. A balance between the pro- and anti-inflammatory cells (T cells, NK cells, and MDSCs) is crucial for successful implantation and placentation (40, 49–53). In addition to protecting the fetus from maternal immune attacks, immune cells play critical roles in the migration and invasion of trophoblasts and in forming decidual blood vessels (54). The maternal corpus luteum and fetal placenta can signal the production of high levels of estrogen and progesterone (55), and interactions involving hormones and immune cells cannot be ignored.

2.1. Immunosuppressive function of MDSCs

Immunotolerance is vital in the maternal immune system in order to accept the embryo. As a population of novel immunoregulatory cells, MDSCs have received increasing attention during early pregnancy rather than in cancer and autoimmune diseases. Besides investigations into the frequency and induction of MDSCs in pregnant human and mouse models, studies have also focused on understanding their immunosuppressive effects during pregnancy. G-MDSCs and M-MDSCs exert immunosuppressive functions via different molecular mechanisms (56). M-MDSCs function primarily through the secretion of nitric oxide and arginase-1 (Arg-1) (57), whereas G-MDSCs produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and hydrogen peroxide (58). Cytokines, growth factors, and microorganisms enhance the immunosuppressive functions of MDSCs in tumors or the inflammatory microenvironment through mediators and subsequently activate nuclear factor kappa B, signal transducer and activator of transcriptions (STATs), and other signaling pathways (59–61).

An earlier study reported that G-MDSCs comprise the dominant MDSC subset in the peripheral blood of pregnant women, producing immunosuppressive enzymes such as Arg-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (62). In an MDSC depletion pregnancy mouse model, T cells showed higher proliferation capacity without Arg-1 and ROS (63). In our preliminary research, the T cells in the peripheral blood of infertile patients exhibited higher immunosuppressive function than those in the MDSC-depleted group (43). Furthermore, it has been suggested that MDSCs reduce the T-cell responses in a cell–cell contact manner (40). In humans, a subpopulation of decidual MDSCs was first recognized by Bartmann et al. in 2015. These cells secrete high levels of immunosuppressive products, including Arg-1, iNOS, and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and produce anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), with the ability to inhibit T-cell proliferation (64). Although the relationship between endometriosis and embryo implantation has received increasing attention, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Elevated G-MDSC counts positively regulate the immunosuppressive activity (increased Arg-1 and ROS levels and suppressed T-cell proliferation) and the increased number of endometrial lesions. However, MDSCs depleted with the anti-Gr-1 antibody in mice exhibited dramatically fewer lesions (65). This indicates that MDSCs could possibly reduce endometrial receptivity so as to affect embryo implantation through immune attack.

As a form of semi-allogeneic transplantation, the embryo is considered as a foreign antigen by the maternal immune system; therefore, appropriate immunosuppressive products are essential in inducing immune tolerance.

2.2. MDSCs shift T-cell differentiation

The maternal immune system is a complex immune paradox. The mother is sensitized by foreign embryos in early pregnancy under estrogen and progesterone stimulation. Subsequently, immune tolerance is induced to protect the fetus from maternal immune attack. In recent years, the research on maternal–fetal immunity has focused on the balance between T helper (Th) 1/Th2 cells and Th17/regulatory T cells (Tregs) (66–68). The hyperfunction of pro-inflammatory T cells, such as Th1 and Th17, has been confirmed to be associated with recurrent implantation failure (69, 70).

It is well documented that MDSCs in the decidua isolated from pregnant women can induce the expression of forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) in CD4+ T cells (Tregs) through the TGF-β/β-catenin signaling pathway. Furthermore, CD4+Foxp3+ T cells are associated with increased MDSC number and recruitment, resulting in a positive feedback loop (71). In addition, MDSCs have been reported to induce a shift toward the anti-inflammatory subtype of Th2 cells via cell–cell interactions (72). Exosomes released by G-MDSCs in pregnant women have the ability to suppress T-cell proliferation, polarize Th cells to Th2 and Tregs, and inhibit lymphocyte cytotoxicity (73). Although the exact reason remains unclear, the reduction of L-selectin expression in naive T cells has been considered to inhibit their trafficking toward lymph nodes (38). Reducing the frequency of MDSCs leads to T-cell responses that enhance and elevate the ratio of Th1 to total T cells in pregnant women (74). In addition to T cells, multiple types of effector immune cells, including macrophages, uterine natural killer (uNK) cells, and immature dendritic cells (iDCs), play substantial roles in the induction of maternal–fetal immunotolerance (39, 75, 76).

2.3. MDSCs affect NK cell cytotoxicity

NK cells represent one of the dominant innate lymphoid cell types that exert cytotoxic effects and primarily contribute to the killing of pathogen-infected cells and tumor cells (77). These cells can primarily be categorized into two subtypes: peripheral blood NK (pbNK) cells and tissue-resident NK (trNK) cells. pbNK cells are identified as CD3−CD56+ in humans, whereas trNK cells exhibit various phenotypes and signatures (78, 79). Therefore, the CD45+CD56+Lin− cells in humans or the CD45+Lin−NK1.1+NKp46+ cells in mice are defined as uNK cells. Owing to the unique structure of the uterus, uNK cells are mostly distributed in the endometrium. uNK cells are also known as decidual NK cells (80). In contrast to the cytotoxicity in pbNK cells, uNK cells facilitate decidualization and placenta formation by remodeling the extracellular matrix and endometrial stroma vessels (81).

NK cells can trigger targeted cell death by releasing cytotoxic granules, such as granzymes and perforin. Furthermore, NK cells are also employed to recognize and eliminate target cells through the NK group protein 2D-activating NK receptor (NKG2C). A study on mouse models identified that MDSC depletion results in the upregulation of the embryo resorption rates and a decrease in the uNK cell counts. Furthermore, MDSC depletion increased the cytotoxicity of uNK cells by upregulating perforin and granzyme B in the cytoplasm and NKG2C on the cell surface (38, 41, 63). It cannot be ignored that MDSCs also represent something of a double-edged sword during pregnancy because of the immunosuppressive function of pbNK cells. In a pregnant mouse model with breast cancer, MDSC accumulation led to the inhibition of NK cell activity and the subsequent promotion of tumor metastasis and disease progression (82).

2.4. MDSCs promote angiogenesis

Epidemiological and experimental research confirmed that an imbalance in circulating angiogenic factors directly leads to embryo implantation failure and maternal pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia (83, 84). Although several potential cellular immunities associated with MDSCs at the maternal–fetal interface have been identified, MDSCs are related to vascular remodeling during embryo implantation and placentation. For instance, it is well documented that MDSCs support angiogenesis in tumor environments (36, 85, 86). Adequate invasion of extravillous trophoblasts into the endometrium with dilated and reconstructed spiral arteries in the myometrium so as to maintain an adequate blood supply is a prerequisite for a successful pregnancy. It has been shown that MDSCs play crucial roles during placental formation, similar to that during tumorigenesis (87). However, there is no direct evidence suggesting that MDSCs promote angiogenesis during human placentation. In rats, the MDSC-derived vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been confirmed to promote the development of maternal uterine spiral arteries and placenta to elevate the reception of implantation (88). In patients undergoing IVF, elevated serum VEGF levels were positively related to the MDSC ratio. Furthermore, the VEGF level and MDSC ratio positively correlated with the pregnancy rates (43). In addition to VEGF, MDSCs have also been discovered to secrete various bioactive factors, including CXC chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2), CXCR4, IL-6, TGF-β, and metalloproteinases, that could facilitate tumor migration and metastasis and promote angiogenesis (36). G-MDSCs in the decidua with a high expression of CXCR2 have also been found at the maternal–fetal interface and supposedly induced angiogenesis (89, 90). In patients with spontaneous miscarriage, VEGF activated the VEGF or MEK/ERK signaling pathways in the villi to govern uterine angiogenesis and vascular remodeling during pregnancy (91, 92). In general, promoting angiogenesis may be another role of MDSCs in promoting embryo implantation.

2.5. Mutual promotion of MDSCs and trophoblasts

The embryo must experience the cleavage stage and the blastocyst stage and finally implant into the endometrium. MDSCs are more abundant in the peripheral blood and decidua of pregnant women and mice than in those of non-pregnant individuals (74, 81). In one of our preliminary experiments to investigate the relationship between MDSCs and trophoblasts, we showed that the proportion of MDSCs in the peripheral blood of IVF patients was positively correlated with pregnancy outcomes (43, 62). These findings suggest that MDSCs enhance trophoblast cell activity. Trophoblasts are also effective players in the expansion of MDSCs. An in vitro study using a trophoblast cell line (HTR8/SVneo) reported the successful triggering of peripheral CD14+ myelomonocytic cell differentiation into MDSCs with high expression of IDO1 and Arg-1. Notably, these cells also expressed higher levels of STAT3, indicating the potential mechanisms underlying trophoblast-induced MDSC differentiation (93). Together, these findings reveal the positive feedback loop of trophoblast implantation and MDSC recruitment at the maternal–fetal interface.

2.6. Expansion and differentiation of MDSCs under conditions of hormone stimulation

During gestation, the maternal corpus luteum and fetal placenta can relay to produce high levels of estrogen and progesterone (55), and the interactions between hormones and MDSCs cannot be ignored. The MDSC count and frequency steadily increase during pregnancy and peak in the second trimester, showing parallel changes with the circulating estradiol and progesterone levels. Exosomes isolated from the peripheral blood MDSCs of pregnant women exhibited various abilities involving differentiation and suppressive functions according to the stage of gestation (73). Growing evidence has shown that the recruitment and the accumulation of MDSCs depend on estradiol signaling in cancer patients (94). During human gestation, high estradiol and progesterone levels considerably facilitate the ratio and suppressive functions in both G-MDSCs and M-MDSCs via the STAT3 signaling pathway (40, 95). Estradiol alone may induce an increased VEGF expression in MDSCs to promote maternal uterine spiral arteries and placental development in rats (88, 96). Similar to the above-mentioned hormones, human leukocyte antigen G (HLA-G), a molecule secreted and expressed by several cells in the maternal–fetal interface, is also a crucial player in MDSC accumulation in the decidua (97). It usually binds to immunoglobulin-like transcript 4 and induces the expansion and differentiation of MDSCs in peripheral blood mononuclear cells through STAT3 signaling (98, 99). A recent study has shown that the estradiol receptor negatively modulated the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) (100). HIF-1α deficiency at the maternal–fetal interface leads to a decrease in the MDSC counts. Furthermore, silencing the expression of HIF-1α in MDSCs results in an impaired immunosuppressive function and renders them susceptible to apoptosis (101). Therefore, hormones protect and ensure embryo implantation and regulate the function of MDSCs through multiple pathways.

2.7. Lipid metabolism of MDSCs

Cellular energy metabolism is currently a critical area of focus in scientific research. Understanding the role of energy metabolism could help in better comprehending the fate of MDSCs during gestation or in pathological processes. An association between MDSCs and lipid metabolism was first recognized in 2011 by Xia et al. (102). The authors identified that MDSCs accumulated in the fat tissue, the liver, and peripheral blood, with pro-inflammation and reestablishment of metabolic homeostatic functions, even increasing insulin resistance. In contrast, the adoptive transfer of MDSCs reduced obesity-associated inflammation and improved insulin sensitivity (103). In humans, the M-MDSC counts were higher in the peripheral blood of obese men compared to those in the control group (104). Mechanistically, excessive adipocytes secreted pro-inflammatory mediators, including prostaglandin E2, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and IL-1β (105), and MDSCs were recruited to the adipose tissue, subsequently resulting in a substantially worse immune response cascade (106–108). Dyslipidemia may also lead to the accumulation and immunosuppressive capacity enhancement of MDSCs, indicating that exogenous lipids may be taken up by MDSCs (11). In patients experiencing unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss, G-MDSC differentiation was associated with the pSTAT3/FABP5/PGE2 pathway (109). These findings are instrumental in understanding the physiological mechanisms of immune tolerance in pregnancy.

3. MDSCs during pregnancy

Recently, the numbers of studies investigating the role of MDSCs during pregnancy have increased. MDSCs are accumulated in a time-dependent manner during gestation (62, 74). Abnormal pregnancies and pregnancy complications, including spontaneous miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and preeclampsia (PE), are also closely related to an imbalance in the maternal–fetal immunological tolerance (51, 110, 111). As reviewed and discussed previously, MDSC deficiency may participate in such adverse events.

3.1. MDSC deficiency leads to spontaneous miscarriage

Spontaneous miscarriage is the loss of a pregnancy before viability with no manual intervention. This condition occurs in up to 20% of recognized pregnancies (109). As listed above, there is a reciprocal causation between MDSC deficiency and spontaneous miscarriage in the first or the second trimester. A reduction in the MDSC ratio, accompanied by a decrease in the levels of Arg-1, iNOS, IL-10, and TGF-β, has been observed in a spontaneous abortion mouse model compared to controls (41). The proportion of MDSCs was significantly increased in the decidua of early pregnant women compared to non-pregnant women (71, 112). Decidual G-MDSC apoptosis is mediated by TNF-related apoptosis-induced ligand (TRAIL) in a caspase 3-dependent manner. Notably, downregulated expression of the TRAIL receptor DcR2 leads to increased G-MDSC apoptosis, and this is responsible for spontaneous miscarriage (113). Generally, high levels of estradiol and progesterone lead to the recruitment of MDSCs, and an increase in their counts, during gestation. MDSCs manipulate the outcomes of pregnancy by producing immunosuppressive molecules (62, 74), regulating immune tolerance (96, 114), promoting angiogenesis (95), and inducing trophoblast implantation (40, 63).

3.2. MDSC deficiency results in pregnancy complications

IUGR represents an abnormal pregnancy and is the second leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality, affecting 5% of pregnancies (114). IUGR is one of the major causes of spontaneous miscarriage, prematurity, stillbirth, and even infant mortality (115). On the other hand, PE is characterized by new-onset hypertension, usually occurring after 20 weeks of gestation and affecting 3%–8% of pregnancies (116). The causes of IUGR and PE are multifactorial, including maternal age and nutrition, thrombophilia, placental dysfunction, and fetal factors (117). Placental dysfunction includes uteroplacental insufficiency, vessel thrombosis, placenta or spiral artery arteritis, chronic villitis, and umbilical cord abnormalities (118, 119). There is still a lack of IUGR and PE animal models; therefore, investigations have been primarily conducted in humans. As mentioned previously, G-MDSCs are observed in all stages of pregnancy and are accompanied by high cellular levels of Arg-1 and ROS activity; however, patients with IUGR exhibit a significantly lower suppressive activity. Moreover, the frequency of G-MDSCs is negatively correlated with adverse outcomes in newborns from pregnancies with IUGR (120). The MDSC ratio and serum Arg-1 levels in patients with PE are much lower than those in healthy pregnant women (111). Furthermore, the frequency of T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM3)+ MDSCs is also more elevated in patients with PE than in healthy controls, and the Tim-3/galectin-9 pathway is considered to modulate the function of MDSCs so as to affect the pathogenesis of PE (121). We speculate that adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with IUGR and PE may be related to immune imbalance, angiogenesis disorders, and shallow placental implantation caused by MDSC deficiency during early pregnancy.

4. MDSCs in postpartum and newborns

MDSCs play an immunosuppressive role in tumors (122, 123) and a pro-inflammatory role in autoimmune diseases (124, 125). Similarly, there is a shift from the early anti-inflammatory profiles that contribute to embryo implantation to a late pro-inflammatory cytokine profile that promotes fetal delivery (126). Notably, the MDSC counts decline rapidly in the peripheral blood of women after parturition (62). A transcriptome study that compared pregnancy-induced MDSCs to tumor-induced MDSCs revealed similar transcriptomes in both conditions. However, the antimicrobial-associated protein levels were higher in pregnancy-induced MDSCs (127). Furthermore, the MDSCs in neonates exhibited antimicrobial activity by secreting higher levels of cathepsin G, neutrophil cytosolic factor 1, S100 calcium-binding protein A8/A9, myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, neutrophil elastase, and lipocalin 2 (127). Similarly, the MDSCs in breast milk have also been found to protect infants from necrotizing enterocolitis and nosocomial bacterial infections (128). It appears that the MDSCs transferred from the mother to the fetus during delivery via the umbilical cord and breast milk harbor antimicrobial effects in infants.

In addition to this protective function, MDSCs may also play a negative role in postnatal immune development, increasing susceptibility to infections in neonates. Estradiol levels are high in newborns, and there is estradiol-dominant MDSC recruitment and augmentation. Among infants, preterm babies show elevated estradiol levels in serum compared to full-term babies, while the MDSCs in umbilical cord blood also exhibit an abnormal increase (129). Premature infants are more susceptible to necrotizing enterocolitis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and sepsis (44, 127, 128). The underlying mechanisms may be associated with immune regulation activity and the immunosuppressive characteristics of MDSCs.

During the neonatal period, a balance between immune attack and tolerance is extremely important (130). Generally, the immunosuppressive functions of umbilical cord blood MDSCs are to inhibit the differentiation and proliferation of Th1 and Th17 cells by producing Arg-1 and ROS and inducing cell–cell contact and to enhance the accumulation of immune regulatory Th2 cells and Tregs (131–134). Furthermore, MDSCs also suppress the cytotoxic NK cells through cell–cell interactions (131). When an anti-inflammatory immune reaction is activated (represented by Th2 and Treg hyperfunction), the newborn will not exhibit excessive immune attack when exposed to various antigens, bacteria, and viruses. However, in preterm infants, the high frequency of MDSCs enhances immune tolerance, leading to insufficient immune responses and neonatal diseases (46, 134–136).

5. Conclusion

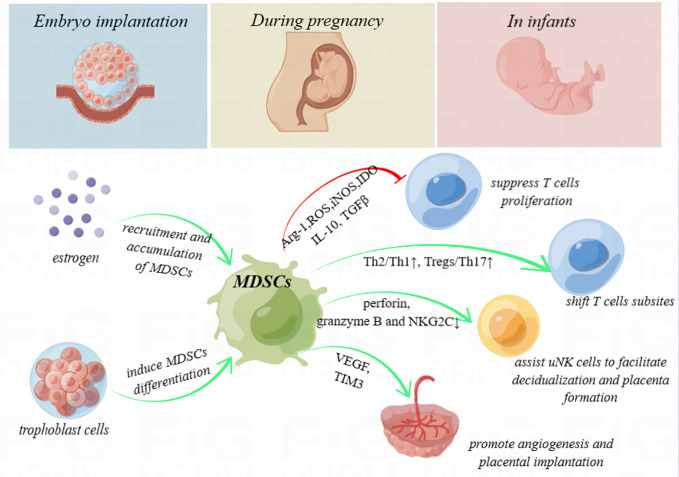

The immune environment at the maternal–fetal interface is complex and mysterious. MDSCs, as immunoregulatory cells with both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions, are well documented to act as an escort throughout pregnancy (schematic diagram shown in Figure 1 ). Identifying the molecular mechanisms underlying the angiogenesis promotion and trophoblast implantation-inducing functions of these cells will enable precision therapy. During the window of implantation, intra-uterus transfusion of induced MDSCs or augment MDSCs in the decidua using multiple cytokines may provide tangible clinical benefits, such as elevate the live birth rate in recurrent embryo implantation failure, decrease pregnancy complications, and promote neonatal health. However, whether immunosuppression during pregnancy promotes the occurrence and progression of tumors remains uncertain. Further studies focusing on this aspect still need to be conducted.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) secrete high levels of immunosuppressive products, including arginase-1 (Arg-1), reactive oxygen species (ROS), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and produce anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), with the ability to inhibit T-cell proliferation. In addition, MDSCs shift the T helper (Th) 1/Th2 cell and Th17/regulatory T cell (Treg) subsets to exert immunoregulation function. They also enhance uterine natural killer (uNK) cells to facilitate decidualization and placenta formation by downregulating perforin and granzyme B in the cytoplasm and NK group protein 2 D‐activating NK receptor (NKG2C) on the cell surface and promote angiogenesis and placental implantation through the VEGF and TIM3 pathway. During pregnancy, high levels of estrogen and trophoblasts may recruit, accumulate, or even induce the differentiation of MDSCs. MDSCs deficiency is considered to be associated with embryo implantation failure, spontaneous miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia. Furthermore, MDSCs even play crucial roles to enhance immune tolerance in neonates.

Author contributions

BP, CH, HL, XN, and KW wrote the manuscript. CZ and HY revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province (YDZJ202201ZYTS085, 20220204020YY, and YDZJ202201ZYTS027) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82201847).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Parker KH, Beury DW, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: Critical cells driving immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Adv Cancer Res (2015) 128:95–139. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hu C, Pang B, Lin G, Zhen Y, Yi H. Energy metabolism manipulates the fate and function of tumour myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Br J Cancer (2020) 122(1):23–9. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0644-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li Q, Pan PY, Gu P, Xu D, Chen SH. Role of immature myeloid gr-1+ cells in the development of antitumor immunity. Cancer Res (2004) 64(3):1130–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol (2009) 9(3):162–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, van Beynen J, English NR, Knight SC, et al. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: A mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. J Immunol (2001) 166(1):678–89. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmielau J, Finn OJ. Activated granulocytes and granulocyte-derived hydrogen peroxide are the underlying mechanism of suppression of t-cell function in advanced cancer patients. Cancer Res (2001) 61(12):4756–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Damuzzo V, Pinton L, Desantis G, Solito S, Marigo I, Bronte V, et al. Complexity and challenges in defining myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cytometry B Clin Cytom (2015) 88(2):77–91. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol (2012) 12(4):253–68. doi: 10.1038/nri3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Youn JI, Collazo M, Shalova IN, Biswas SK, Gabrilovich DI. Characterization of the nature of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Leukoc Biol (2012) 91(1):167–81. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0311177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alshetaiwi H, Pervolarakis N, McIntyre LL, Ma D, Nguyen Q, Rath JA, et al. Defining the emergence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer using single-cell transcriptomics. Sci Immunol (2020) 5(44):eaay6017. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay6017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al-Khami AA, Zheng L, Del Valle L, Hossain F, Wyczechowska D, Zabaleta J, et al. Exogenous lipid uptake induces metabolic and functional reprogramming of tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology (2017) 6(10):e1344804. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1344804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Veglia F, Tyurin VA, Blasi M, De Leo A, Kossenkov AV, Donthireddy L, et al. Fatty acid transport protein 2 reprograms neutrophils in cancer. Nature (2019) 569(7754):73–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1118-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang J, Xu X, Shi M, Chen Y, Yu D, Zhao C, et al. CD13(hi) neutrophil-like myeloid-derived suppressor cells exert immune suppression through arginase 1 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncoimmunology (2017) 6(2):e1258504. doi: 10.1080/2162402x.2016.1258504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Resheq YJ, Menzner AK, Bosch J, Tickle J, Li KK, Wilhelm A, et al. Impaired transmigration of myeloid-derived suppressor cells across human sinusoidal endothelium is associated with decreased expression of CD13. J Immunol (2017) 199(5):1672–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lang S, Bruderek K, Kaspar C, Höing B, Kanaan O, Dominas N, et al. Clinical relevance and suppressive capacity of human myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets. Clin Cancer Res (2018) 24(19):4834–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-3726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Condamine T, Dominguez GA, Youn JI, Kossenkov AV, Mony S, Alicea-Torres K, et al. Lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor-1 distinguishes population of human polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients. Sci Immunol (2016) 1(2):aaf8943. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaf8943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haile LA, Gamrekelashvili J, Manns MP, Korangy F, Greten TF. CD49d is a new marker for distinct myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations in mice. J Immunol (2010) 185(1):203–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Geissmann F, Auffray C, Palframan R, Wirrig C, Ciocca A, Campisi L, et al. Blood monocytes: distinct subsets, how they relate to dendritic cells, and their possible roles in the regulation of T-cell responses. Immunol Cell Biol (2008) 86(5):398–408. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lesokhin AM, Hohl TM, Kitano S, Cortez C, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Avogadri F, et al. Monocytic CCR2(+) myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote immune escape by limiting activated CD8 T-cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res (2012) 72(4):876–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-11-1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roussel M, Ferrell PB, Jr., Greenplate AR, Lhomme F, Le Gallou S, Diggins KE, et al. Mass cytometry deep phenotyping of human mononuclear phagocytes and myeloid-derived suppressor cells from human blood and bone marrow. J Leukoc Biol (2017) 102(2):437–47. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5MA1116-457R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao T, Liu S, Ding X, Johnson EM, Hanna NH, Singh K, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase, CSF1R, and PD-L1 determine functions of CD11c+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells. JCI Insight (2022) 7(17):e156623. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.156623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mandruzzato S, Solito S, Falisi E, Francescato S, Chiarion-Sileni V, Mocellin S, et al. IL4Ralpha+ myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion in cancer patients. J Immunol (2009) 182(10):6562–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shao X, Wu B, Cheng L, Li F, Zhan Y, Liu C, et al. Distinct alterations of CD68(+)CD163(+) M2-like macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in newly diagnosed primary immune thrombocytopenia with or without CR after high-dose dexamethasone treatment. J Transl Med (2018) 16(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1424-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang W, Jiang M, Chen J, Zhang R, Ye Y, Liu P, et al. SOCS3 suppression promoted the recruitment of CD11b(+)Gr-1(-)F4/80(-)MHCII(-) early-stage myeloid-derived suppressor cells and accelerated interleukin-6-Related tumor invasion via affecting myeloid differentiation in breast cancer. Front Immunol (2018) 9:1699. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khan ANH, Emmons TR, Wong JT, Alqassim E, Singel KL, Mark J, et al. Quantification of early-stage myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer requires excluding basophils. Cancer Immunol Res (2020) 8(6):819–28. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-19-0556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wright AK, Newby C, Hartley RA, Mistry V, Gupta S, Berair R, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell-like fibrocytes are increased and associated with preserved lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Allergy (2017) 72(4):645–55. doi: 10.1111/all.13061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang H, Maric I, DiPrima MJ, Khan J, Orentas RJ, Kaplan RN, et al. Fibrocytes represent a novel MDSC subset circulating in patients with metastatic cancer. Blood (2013) 122(7):1105–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-449413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mu X, Wu K, Zhu Y, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Xiao L, et al. Intra-arterial infusion chemotherapy utilizing cisplatin inhibits bladder cancer by decreasing the fibrocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in an m6A-dependent manner. Mol Immunol (2021) 137:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2021.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zoso A, Mazza EM, Bicciato S, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V, Serafini P, et al. Human fibrocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells express IDO and promote tolerance via treg-cell expansion. Eur J Immunol (2014) 44(11):3307–19. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hegde S, Leader AM, Merad M. MDSC: Markers, development, states, and unaddressed complexity. Immunity (2021) 54(5):875–84. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol Res (2017) 5(1):3–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-16-0297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pang B, Zhen Y, Hu C, Ma Z, Lin S, Yi H. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells shift Th17/Treg ratio and promote systemic lupus erythematosus progression through arginase-1/miR-322-5p/TGF-β pathway. Clin Sci (London Engl 1979) (2020) 134(16):2209–22. doi: 10.1042/cs20200799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu H, Ling CC, Yeung WHO, Pang L, Liu J, Zhou J, et al. Monocytic MDSC mobilization promotes tumor recurrence after liver transplantation via CXCL10/TLR4/MMP14 signaling. Cell Death Dis (2021) 12(5):489. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03788-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schneider KM, Mohs A, Gui W, Galvez EJC, Candels LS, Hoenicke L, et al. Imbalanced gut microbiota fuels hepatocellular carcinoma development by shaping the hepatic inflammatory microenvironment. Nat Commun (2022) 13(1):3964. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31312-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang S, Ma X, Zhu C, Liu L, Wang G, Yuan X. The role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with solid tumors: A meta-analysis. PloS One (2016) 11(10):e0164514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rahma OE, Hodi FS. The intersection between tumor angiogenesis and immune suppression. Clin Cancer Res (2019) 25(18):5449–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hinshaw DC, Shevde LA. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res (2019) 79(18):4557–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-18-3962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P, Figley C, Long R, Park D, Carter D, et al. Frontline science: Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) facilitate maternal-fetal tolerance in mice. J Leukoc Biol (2017) 101(5):1091–101. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1HI1016-306RR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ghaebi M, Nouri M, Ghasemzadeh A, Farzadi L, Jadidi-Niaragh F, Ahmadi M, et al. Immune regulatory network in successful pregnancy and reproductive failures. BioMed Pharmacother (2017) 88:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pan T, Liu Y, Zhong LM, Shi MH, Duan XB, Wu K, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells are essential for maintaining feto-maternal immunotolerance via STAT3 signaling in mice. J Leukocyte Biol (2016) 100(3):499–511. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1A1015-481RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ren J, Zeng W, Tian F, Zhang S, Wu F, Qin X, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells depletion may cause pregnancy loss via upregulating the cytotoxicity of decidual natural killer cells. Am J Reprod Immunol (2019) 81(4):e13099. doi: 10.1111/aji.13099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu M, Huang X, Yi S, Sun H, Zhou J. High granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell levels in the peripheral blood predict a better IVF treatment outcome. J Matern Fetal Neona (2019) 32(7):1092–7. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1400002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hu C, Zhen Y, Pang B, Lin X, Yi H. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells are regulated by estradiol and are a predictive marker for IVF outcome. Front Endocrinol (2019) 10:521. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu Y, Perego M, Xiao Q, He Y, Fu S, He J, et al. Lactoferrin-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell therapy attenuates pathologic inflammatory conditions in newborn mice. J Clin Invest (2019) 129(10):4261–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI128164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leiber A, Schwarz J, Köstlin N, Spring B, Fehrenbach B, Katava N, et al. Neonatal myeloid derived suppressor cells show reduced apoptosis and immunosuppressive activity upon infection with escherichia coli. Eur J Immunol (2017) 47(6):1009–21. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schwarz J, Scheckenbach V, Kugel H, Spring B, Pagel J, Härtel C, et al. Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (GR-MDSC) accumulate in cord blood of preterm infants and remain elevated during the neonatal period. Clin Exp Immunol (2018) 191(3):328–37. doi: 10.1111/cei.13059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang F, Zheng Q, Jin L. Dynamic function and composition changes of immune cells during normal and pathological pregnancy at the maternal-fetal interface. Front Immunol (2019) 10:2317. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vento-Tormo R, Efremova M, Botting RA, Turco MY, Vento-Tormo M, Meyer KB, et al. Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal-fetal interface in humans. Nature (2018) 563(7731):347–53. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0698-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cai D, Tang Y, Yao X. Changes of γδT cell subtypes during pregnancy and their influences in spontaneous abortion. J Reprod Immunol (2019) 131:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2019.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miller D, Gershater M, Slutsky R, Romero R, Gomez-Lopez N. Maternal and fetal T cells in term pregnancy and preterm labor. Cell Mol Immunol (2020) 17(7):693–704. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0471-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lu H, Yang H-L, Zhou W-J, Lai Z-Z, Qiu X-M, Fu Q, et al. Rapamycin prevents spontaneous abortion by triggering decidual stromal cell autophagy-mediated NK cell residence. Autophagy (2021) 17(9):2511–27. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1833515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fu B, Tian Z, Wei H. TH17 cells in human recurrent pregnancy loss and pre-eclampsia. Cell Mol Immunol (2014) 11(6):564–70. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang Y, Wang X, Zhang R, Wang X, Fu H, Yang W. MDSCs interactions with other immune cells and their role in maternal-fetal tolerance. Int Rev Immunol (2022) 41(5):534–51. doi: 10.1080/08830185.2021.1938566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Aplin JD, Myers JE, Timms K, Westwood M. Tracking placental development in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2020) 16(9):479–94. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0372-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu B, Guo F, Yang Y, Long W, Zhou J. Steroidomics of pregnant women at advanced age. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2022) 13:796909. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.796909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Veglia F, Perego M, Gabrilovich D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat Immunol (2018) 19(2):108–19. doi: 10.1038/s41590-017-0022-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cassetta L, Bruderek K, Skrzeczynska-Moncznik J, Osiecka O, Hu X, Rundgren IM, et al. Differential expansion of circulating human MDSC subsets in patients with cancer, infection and inflammation. J Immunother Cancer (2020) 8(2):e001223. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Perez C, Botta C, Zabaleta A, Puig N, Cedena MT, Goicoechea I, et al. Immunogenomic identification and characterization of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in multiple myeloma. Blood (2020) 136(2):199–209. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Deng LJ, Qi M, Li N, Lei YH, Zhang DM, Chen JX. Natural products and their derivatives: Promising modulators of tumor immunotherapy. J Leukoc Biol (2020) 108(2):493–508. doi: 10.1002/jlb.3mr0320-444r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Salminen A, Kauppinen A, Kaarniranta K. AMPK activation inhibits the functions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC): impact on cancer and aging. J Mol Med (Berl) (2019) 97(8):1049–64. doi: 10.1007/s00109-019-01795-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Taki M, Abiko K, Baba T, Hamanishi J, Yamaguchi K, Murakami R, et al. Snail promotes ovarian cancer progression by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells via CXCR2 ligand upregulation. Nat Commun (2018) 9(1):1685. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03966-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Köstlin N, Kugel H, Spring B, Leiber A, Marmé A, Henes M, et al. Granulocytic myeloid derived suppressor cells expand in human pregnancy and modulate T-cell responses. Eur J Immunol (2014) 44(9):2582–91. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhao H, Kalish F, Schulz S, Yang Y, Wong RJ, Stevenson DK. Unique roles of infiltrating myeloid cells in the murine uterus during early to midpregnancy. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2015) 194(8):3713–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bartmann C, Junker M, Segerer SE, Häusler SF, Krockenberger M, Kämmerer U. CD33(+) /HLA-DR(neg) and CD33(+) /HLA-DR(+/-) cells: Rare populations in the human decidua with characteristics of MDSC. Am J Reprod Immunol (2016) 75(5):539–56. doi: 10.1111/aji.12492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhang T, Zhou J, Man GCW, Leung KT, Liang B, Xiao B, et al. MDSCs drive the process of endometriosis by enhancing angiogenesis and are a new potential therapeutic target. Eur J Immunol (2018) 48(6):1059–73. doi: 10.1002/eji.201747417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Suah AN, Tran D-KV, Khiew SH, Andrade MS, Pollard JM, Jain D, et al. Pregnancy-induced humoral sensitization overrides T cell tolerance to fetus-matched allografts in mice. J Clin Invest (2021) 131(1):e140715. doi: 10.1172/JCI140715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kinder JM, Stelzer IA, Arck PC, Way SS. Immunological implications of pregnancy-induced microchimerism. Nat Rev Immunol (2017) 17(8):483–94. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pollard JM, Chong AS. Semiallogeneic pregnancy: A paradigm change for T-cell transplantation tolerance. Transplantation (2022) 106(6):1098–100. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Piccinni MP, Raghupathy R, Saito S, Szekeres-Bartho J. Cytokines, hormones and cellular regulatory mechanisms favoring successful reproduction. Front Immunol (2021) 12:717808. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.717808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. AbdulHussain G, Azizieh F, Makhseed M, Raghupathy R. Effects of progesterone, dydrogesterone and estrogen on the production of Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokines by lymphocytes from women with recurrent spontaneous miscarriage. J Reprod Immunol (2020) 140:103132. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2020.103132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kang X, Zhang X, Liu Z, Xu H, Wang T, He L, et al. Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells maintain feto-maternal tolerance by inducing Foxp3 expression in CD4+CD25-T cells by activation of the TGF-β/β-catenin pathway. Mol Hum Reprod (2016) 22(7):499–511. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaw026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Köstlin N, Hofstädter K, Ostermeir A-L, Spring B, Leiber A, Haen S, et al. Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells accumulate in human placenta and polarize toward a Th2 phenotype. J Immunol (Baltimore Md 1950) (2016) 196(3):1132–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dietz S, Schwarz J, Ruhle J, Schaller M, Fehrenbacher B, Marme A, et al. Extracellular vesicles released by myeloid-derived suppressor cells from pregnant women modulate adaptive immune responses. Cell Immunol (2021) 361:104276. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Nair RR, Sinha P, Khanna A, Singh K. Reduced myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the blood and endometrium is associated with early miscarriage. Am J Reprod Immunol (2015) 73(6):479–86. doi: 10.1111/aji.12351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. PrabhuDas M, Bonney E, Caron K, Dey S, Erlebacher A, Fazleabas A, et al. Immune mechanisms at the maternal-fetal interface: perspectives and challenges. Nat Immunol (2015) 16(4):328–34. doi: 10.1038/ni.3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nasri F, Doroudchi M, Namavar Jahromi B, Gharesi-Fard B. T Helper cells profile and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+Regulatory T cells in polycystic ovary syndrome. Iran J Immunol (2018) 15(3):175–85. doi: 10.22034/IJI.2018.39387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Jabrane-Ferrat N. Features of human decidual NK cells in healthy pregnancy and during viral infection. Front In Immunol (2019) 10:1397. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Huhn O, Zhao X, Esposito L, Moffett A, Colucci F, Sharkey AM. How do uterine natural killer and innate lymphoid cells contribute to successful pregnancy? Front Immunol (2021) 12:607669. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.607669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Björkström NK, Ljunggren HG, Michaëlsson J. Emerging insights into natural killer cells in human peripheral tissues. Nat Rev Immunol (2016) 16(5):310–20. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhang X, Wei H. Role of decidual natural killer cells in human pregnancy and related pregnancy complications. Front In Immunol (2021) 12:728291. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.728291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wang F, Qualls AE, Marques-Fernandez L, Colucci F. Biology and pathology of the uterine microenvironment and its natural killer cells. Cell Mol Immunol (2021) 18(9):2101–13. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00739-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Mauti LA, Le Bitoux M-A, Baumer K, Stehle J-C, Golshayan D, Provero P, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells are implicated in regulating permissiveness for tumor metastasis during mouse gestation. J Clin Invest (2011) 121(7):2794–807. doi: 10.1172/JCI41936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Phipps EA, Thadhani R, Benzing T, Karumanchi SA. Pre-eclampsia: pathogenesis, novel diagnostics and therapies. Nat Rev Nephrol (2019) 15(5):275–89. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0119-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Huang Z, Huang S, Song T, Yin Y, Tan C. Placental angiogenesis in mammals: A review of the regulatory effects of signaling pathways and functional nutrients. Adv Nutr (2021) 12(6):2415–34. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Weber R, Fleming V, Hu X, Nagibin V, Groth C, Altevogt P, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells hinder the anti-cancer activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front In Immunol (2018) 9:1310. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wang SC, Li YH, Piao HL, Hong XW, Zhang D, Xu YY, et al. PD-1 and Tim-3 pathways are associated with regulatory CD8+ T-cell function in decidua and maintenance of normal pregnancy. Cell Death Dis (2015) 6:e1738. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Costanzo V, Bardelli A, Siena S, Abrignani S. Exploring the links between cancer and placenta development. Open Biol (2018) 8(6):180081. doi: 10.1098/rsob.180081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Rabbani ML, Rogers PA. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in endometrial vascular events before implantation in rats. Reproduction (2001) 122(1):85–90. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kang X, Zhang X, Liu Z, Xu H, Wang T, He L, et al. CXCR2-mediated granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells' functional characterization and their role in maternal fetal interface. DNA Cell Biol (2016) 35(7):358–65. doi: 10.1089/dna.2015.2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ahmadi M, Mohammadi M, Ali-Hassanzadeh M, Zare M, Gharesi-Fard B. MDSCs in pregnancy: Critical players for a balanced immune system at the feto-maternal interface. Cell Immunol (2019) 346:103990. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2019.103990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Jing G, Yao J, Dang Y, Liang W, Xie L, Chen J, et al. The role of β-HCG and VEGF-MEK/ERK signaling pathway in villi angiogenesis in patients with missed abortion. Placenta (2021) 103:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2020.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lai ZZ, Yang HL, Shi JW, Shen HH, Wang Y, Chang KK, et al. Protopanaxadiol improves endometriosis associated infertility and miscarriage in sex hormones receptors-dependent and independent manners. Int J Biol Sci (2021) 17(8):1878–94. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.58657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zhang Y, Qu D, Sun J, Zhao L, Wang Q, Shao Q, et al. Human trophoblast cells induced MDSCs from peripheral blood CD14(+) myelomonocytic cells via elevated levels of CCL2. Cell Mol Immunol (2016) 13(5):615–27. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Svoronos N, Perales-Puchalt A, Allegrezza MJ, Rutkowski MR, Payne KK, Tesone AJ, et al. Tumor cell-independent estrogen signaling drives disease progression through mobilization of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Discov (2017) 7(1):72–85. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pan T, Zhong L, Wu S, Cao Y, Yang Q, Cai Z, et al. 17β-oestradiol enhances the expansion and activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells via signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3 signalling in human pregnancy. Clin Exp Immunol (2016) 185(1):86–97. doi: 10.1111/cei.12790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Verma P, Verma R, Nair RR, Budhwar S, Khanna A, Agrawal NR, et al. Altered crosstalk of estradiol and progesterone with myeloid-derived suppressor cells and Th1/Th2 cytokines in early miscarriage is associated with early breakdown of maternal-fetal tolerance. Am J Reprod Immunol (2019) 81(2):e13081. doi: 10.1111/aji.13081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Dietz S, Schwarz J, Velic A, Gonzalez-Menendez I, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Casadei N, et al. Human leucocyte antigen G and murine qa-2 are critical for myeloid derived suppressor cell expansion and activation and for successful pregnancy outcome. Front Immunol (2021) 12:787468. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.787468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Köstlin N, Ostermeir A-L, Spring B, Schwarz J, Marmé A, Walter CB, et al. HLA-G promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation and suppressive activity during human pregnancy through engagement of the receptor ILT4. Eur J Immunol (2017) 47(2):374–84. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Zare M, Namavar Jahromi B, Gharesi-Fard B. Analysis of the frequencies and functions of CD4CD25CD127, CD4HLA-G, and CD8HLA-G regulatory T cells in pre-eclampsia. J Reprod Immunol (2019) 133:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Morita M, Sato Y, Iwasaki R, Kobayashi T, Watanabe R, Oike T, et al. Selective estrogen receptor modulators suppress Hif1α protein accumulation in mouse osteoclasts. PloS One (2016) 11(11):e0165922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Köstlin-Gille N, Dietz S, Schwarz J, Spring B, Pauluschke-Fröhlich J, Poets CF, et al. HIF-1α-Deficiency in myeloid cells leads to a disturbed accumulation of myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC) during pregnancy and to an increased abortion rate in mice. Front In Immunol (2019) 10:161. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Xia S, Sha H, Yang L, Ji Y, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Qi L. Gr-1+ CD11b+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells suppress inflammation and promote insulin sensitivity in obesity. J Biol Chem (2011) 286(26):23591–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.237123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Clements VK, Long T, Long R, Figley C, Smith DMC, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Frontline science: High fat diet and leptin promote tumor progression by inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Leukocyte Biol (2018) 103(3):395–407. doi: 10.1002/JLB.4HI0517-210R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bao Y, Mo J, Ruan L, Li G. Increased monocytic CD14+HLADRlow/- myeloid-derived suppressor cells in obesity. Mol Med Rep (2015) 11(3):2322–8. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Chan P-C, Liao M-T, Hsieh P-S. The dualistic effect of COX-2-Mediated signaling in obesity and insulin resistance. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20(13):3115. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Bunt SK, Yang L, Sinha P, Clements VK, Leips J, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduced inflammation in the tumor microenvironment delays the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and limits tumor progression. Cancer Res (2007) 67(20):10019–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Sade-Feldman M, Kanterman J, Ish-Shalom E, Elnekave M, Horwitz E, Baniyash M. Tumor necrosis factor-α blocks differentiation and enhances suppressive activity of immature myeloid cells during chronic inflammation. Immunity (2013) 38(3):541–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Tomić S, Joksimović B, Bekić M, Vasiljević M, Milanović M, Čolić M, et al. Prostaglanin-E2 potentiates the suppressive functions of human mononuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells and increases their capacity to expand IL-10-Producing regulatory T cell subsets. Front In Immunol (2019) 10:475. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Wang Q, Zhang X, Li C, Xiong M, Bai W, Sun S, et al. Intracellular lipid accumulation drives the differentiation of decidual polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells via arachidonic acid metabolism. Front In Immunol (2022) 13:868669. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.868669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Li YH, Zhou WH, Tao Y, Wang SC, Jiang YL, Zhang D, et al. The galectin-9/Tim-3 pathway is involved in the regulation of NK cell function at the maternal-fetal interface in early pregnancy. Cell Mol Immunol (2016) 13(1):73–81. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Wang Y, Liu Y, Shu C, Wan J, Shan Y, Zhi X, et al. Inhibition of pregnancy-associated granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and arginase-1 production in preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol (2018) 127:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Li C, Chen C, Kang X, Zhang X, Sun S, Guo F, et al. Decidua-derived granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells from circulating CD15+ neutrophils. Hum Reprod (2020) 35(12):2677–91. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Li C, Zhang X, Kang X, Chen C, Guo F, Wang Q, et al. Upregulated TRAIL and reduced DcR2 mediate apoptosis of decidual PMN-MDSC in unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. Front In Immunol (2020) 11:1345. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Mandruzzato G, Antsaklis A, Botet F, Chervenak FA, Figueras F, Grunebaum A, et al. Intrauterine restriction (IUGR). J Perinat Med (2008) 36(4):277–81. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Pilliod RA, Cheng YW, Snowden JM, Doss AE, Caughey AB. The risk of intrauterine fetal death in the small-for-gestational-age fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol (2012) 207(4):318.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ma'ayeh M, Costantine MM. Prevention of preeclampsia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med (2020) 25(5):101123. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2020.101123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Marsál K. Intrauterine growth restriction. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol (2002) 14(2):127–35. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200204000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Veerbeek JHW, Nikkels PGJ, Torrance HL, Gravesteijn J, Post Uiterweer ED, Derks JB, et al. Placental pathology in early intrauterine growth restriction associated with maternal hypertension. Placenta (2014) 35(9):696–701. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.06.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. John RM. Imprinted genes and the regulation of placental endocrine function: Pregnancy and beyond. Placenta (2017) 56:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.01.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Shi M, Chen Z, Chen M, Liu J, Li J, Xing Z, et al. Continuous activation of polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells during pregnancy is critical for fetal development. Cell Mol Immunol (2021) 18(7):1692–707. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00704-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Dong S, Shah NK, He J, Han S, Xie M, Wang Y, et al. The abnormal expression of Tim-3 is involved in the regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and its correlation with preeclampsia. Placenta (2021) 114:108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.08.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Guha P, Heatherton KR, O'Connell KP, Alexander IS, Katz SC. Assessing the future of solid tumor immunotherapy. Biomedicines (2022) 10(3):655. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10030655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Dong S, Guo X, Han F, He Z, Wang Y. Emerging role of natural products in cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B (2022) 12(3):1163–85. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Schroeter A, Roesel MJ, Matsunaga T, Xiao Y, Zhou H, Tullius SG. Aging affects the role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in alloimmunity. Front Immunol (2022) 13:917972. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.917972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Park Y, Kwok SK. Recent advances in cell therapeutics for systemic autoimmune diseases. Immune Netw (2022) 22(1):e10. doi: 10.4110/in.2022.22.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Zhao A-M, Xu H-J, Kang X-M, Zhao A-M, Lu L-M. New insights into myeloid-derived suppressor cells and their roles in feto-maternal immune cross-talk. J Reprod Immunol (2016) 113:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. He Y-M, Li X, Perego M, Nefedova Y, Kossenkov AV, Jensen EA, et al. Transitory presence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in neonates is critical for control of inflammation. Nat Med (2018) 24(2):224–31. doi: 10.1038/nm.4467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Köstlin N, Schoetensack C, Schwarz J, Spring B, Marmé A, Goelz R, et al. Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (GR-MDSC) in breast milk (BM); GR-MDSC accumulate in human BM and modulate T-cell and monocyte function. Front In Immunol (2018) 9:1098. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Budhwar S, Verma R, Verma P, Bala R, Rai S, Singh K. Estradiol correlates with the accumulation of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in pre-term birth: A possible explanation of immune suppression in pre-term babies. J Reprod Immunol (2021) 147:103350. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2021.103350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Levy O. Innate immunity of the newborn: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nat Rev Immunol (2007) 7(5):379–90. doi: 10.1038/nri2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Rieber N, Gille C, Köstlin N, Schäfer I, Spring B, Ost M, et al. Neutrophilic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cord blood modulate innate and adaptive immune responses. Clin Exp Immunol (2013) 174(1):45–52. doi: 10.1111/cei.12143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Dabagh-Gorjani F, Anvari F, Zolghadri J, Kamali-Sarvestani E, Gharesi-Fard B. Differences in the expression of TLRs and inflammatory cytokines in pre-eclamptic compared with healthy pregnant women. Iran J Immunol (2014) 11(4):233–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Gervassi A, Lejarcegui N, Dross S, Jacobson A, Itaya G, Kidzeru E, et al. Myeloid derived suppressor cells are present at high frequency in neonates and suppress in vitro T cell responses. PloS One (2014) 9(9):e107816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Köstlin N, Vogelmann M, Spring B, Schwarz J, Feucht J, Härtel C, et al. Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells from human cord blood modulate T-helper cell response towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype. Immunology (2017) 152(1):89–101. doi: 10.1111/imm.12751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Budhwar S, Verma P, Verma R, Rai S, Singh K. The yin and yang of myeloid derived suppressor cells. Front Immunol (2018) 9:2776. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Leaphart CL, Cavallo J, Gribar SC, Cetin S, Li J, Branca MF, et al. A critical role for TLR4 in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis by modulating intestinal injury and repair. J Immunol (2007) 179(7):4808–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]