Abstract

Background:

Efforts to better support primary care include the addition of primary care–focused billing codes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS).

Objective:

To examine potential and actual use by primary care physicians (PCPs) of the prevention and coordination codes that have been added to the MPFS.

Design:

Cross-sectional and modeling study.

Setting:

Nationally representative claims and survey data.

Participants:

Medicare patients.

Measurements:

Frequency of use and estimated Medicare revenue involving 34 billing codes representing prevention and coordination services for which PCPs could but do not necessarily bill.

Results:

Eligibility among Medicare patients for each service ranged from 8.8% to 100%. Among eligible patients, the median use of billing codes was 2.3%, even though PCPs provided code-appropriate services to more patients, for example, to 5.0% to 60.6% of patients eligible for prevention services. If a PCP provided and billed all prevention and coordination services to half of all eligible patients, the PCP could add to the practice’s annual revenue $124 435 (interquartile range [IQR], $30 654 to $226 813) for prevention services and $86 082 (IQR, $18 011 to $154 152) for coordination services.

Limitation:

Service provision based on survey questions may not reflect all billing requirements; revenues do not incorporate the compliance, billing, and opportunity costs that may be incurred when using these codes.

Conclusion:

Primary care physicians forego considerable amounts of revenue because they infrequently use billing codes for prevention and coordination services despite having eligible patients and providing code-appropriate services to some of those patients. Therefore, creating additional billing codes for distinct activities in the MPFS may not be an effective strategy for supporting primary care.

Keywords: Cancer screening, Elderly, Health care, Medicare, Primary care, Primary care physicians

TOC blurb

One of the ways Medicare has supported U.S. primary care practice is by introducing new codes for prevention and coordination services into the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. The study reported in this article measured how often physicians use the new codes and estimated how much revenue they forgo when they do not use the codes. The authors conclude that adding more codes may not be an effective policy.

Despite the proliferation of alternative payment models, the physician fee schedule continues to play a dominant role in how primary care and other physicians are paid. Core features of primary care—first-contact care that is continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated—are poorly matched with visit-based payments (1); hence, during the past 2 decades, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has incrementally added billing codes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) that provide reimbursement for other primary care activities (2). For instance, there are now billing codes for preventive services, such as providing counseling for smoking cessation or weight loss, and for coordination services, such as providing transitional or chronic care management (3, 4). The CMS also has recently begun to pay for remote physiologic monitoring, brief check-ins, and online digital care (5).

The availability of numerous reimbursable primary care codes stands in stark contrast to the common assertion that a substantial amount of work done by primary care physicians (PCPs) is unrecognized by payors such as Medicare (6–8). The codes attempt to both recognize various types of services that PCPs frequently provide without payment while also encouraging PCPs to deliver services believed to be beneficial to patients. Moreover, these additional codes are potentially important sources of revenue and could increase overall primary care spending in line with policy goals adopted by several states to improve patient outcomes and lower costs (9, 10). Most of these codes, however, have been characterized by very poor adoption. For instance, only 0.2% of Medicare beneficiaries had a claim for obesity counseling in 2015 (11), and only 2.3% of eligible Medicare beneficiaries had a claim for chronic care management in 2016 (12). The low adoption to date suggests that the codes are not being adequately used to perform their function of financing primary care activities.

In this study, we sought to examine the full range of prevention and coordination codes that have been added to the MPFS, summarize their use, and estimate how much revenue PCPs potentially forego by not using them. Understanding the gap between services provided and use of billable codes could help inform Medicare’s evolving strategy for optimizing payment of primary care services.

Methods

Overview

After identifying preventive and coordination services for which Medicare provides payment via billable codes, we used national survey data to estimate the rate at which PCPs provided each service (whether billed or not) to their Medicare patients and claims data to estimate their billing rate. To quantify foregone revenue from services PCPs and their practices provided to their Medicare patients over a year, we used a validated microsimulation model of PCP practices (13, 14). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Harvard Medical School. Informed consent was waived.

Identification of Prevention and Coordination Codes

We identified Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System and/or (CPT) Current Procedural Terminology codes related to prevention or coordination in primary care, beyond usual evaluation and management services, and the year they were added to the MPFS. Although private payers sometimes have distinct codes for similar services, these were not included in our analysis.

Prevention codes were identified from Medicare’s suite of preventive services with zero patient cost sharing (Supplement Table 1, available at Annals.org) (15)—for example, services that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends with a grade A or B. We limited the list to screening and counseling codes by excluding codes related to immunizations; care provided by non-PCP providers; procedures such as mammography, which do not directly bring revenue into primary care; in-office cancer screenings for cervical cancer screening and pelvic, breast, and digital rectal examinations because guidelines typically recommend against these services for most Medicare beneficiaries; and counseling for sexually transmitted infections, given their low incidence in the Medicare beneficiary population. Thus, our analysis included 19 prevention codes in 9 categories of prevention.

We then identified all codes that CMS added to the MPFS to promote coordination of care (Supplement Table 2, available at Annals.org) (5). The coordination codes typically reimburse primary care practices for developing a written, comprehensive care plan and/or providing care outside of traditional face-to-face office visits. To produce conservative estimates, we excluded codes for which there were no national estimates in the literature of the frequency with which the service already occurred in primary care or no clear eligibility criteria, such as interprofessional consultations or remote physiologic monitoring. Thus, our analysis included 15 coordination codes in 4 categories of coordination.

Estimation of Service Eligibility, Provision, Billing, and Payment

For each specified service, we estimated several key parameters: service eligibility is the proportion of Medicare patients who are eligible for a particular service (for example, only Medicare patients with obesity are eligible for the obesity counseling code); service provision is the proportion of eligible patients that reported having received the service regardless of whether the PCP billed for having provided the service; billing rate is the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries eligible for a particular service who have a billing claim for that service; and payment amount is the 2020 dollar amount that CMS paid a practice, before geographic adjustments, for furnishing the service, including payment for the following 3 components: physician work, practice expense, and malpractice.

We used national survey data—mainly from published estimates, but when unavailable, we used our analysis of the 2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System for alcohol and cardiovascular disease counseling—to estimate the service eligibility rate and the rate at which PCPs provided each of the services to their older adult patients (Supplement Methods and Supplement Table 4, available at Annals.org). Although the services actually delivered may not fulfill CMS requirements for billing each service, the patient-reported service provision rate provides a useful benchmark against which to compare the use of the billing codes. We also used Medicare claims data, either from published estimates or, when these data were unavailable, from our analyses using 2020 Medicare claims data for a random 20% sample of fee-for-service beneficiaries continuously enrolled in Part A and B to estimate the rate at which the billable codes are used among eligible Medicare beneficiaries. To determine aggregate payments to primary care for each code, we used the 2019 Medicare Physician/Supplier Procedure Summary file representing all Medicare Part B carrier (professional) fee-for-service claims. These estimates do not include payments made by Medicare Advantage plans. From CMS’ Physician Fee Schedule Look-Up Tool, we extracted the 2020 Medicare payment rate for each billing code.

Estimation of Foregone Revenues

We used a validated microsimulation model to estimate the range of revenue that a full-time physician could earn per year within each service category depending on their practice type and patient mix (13, 14). Two types of revenue estimates were calculated: a “lower bound” for services already done by PCPs but not billed and a conservative and likely more feasible “upper bound” for providing and billing the services to half of all eligible patients.

Using data from national practice databases (16, 17) to estimate the number and characteristics of Medicare patients in each practice, the model simulated national Medicare primary care practice delivery nationwide. Simulation results were expressed on a full-time equivalent physician basis but also on a Medicare patient visit basis (13, 14) to characterize the potential investment of time and resources needed to implement a specific code relative to the reimbursement for an average Medicare patient visit. The 2 estimates together provide a useful reference for considering fixed costs and the potential incremental revenue of expanding billing for a preventive service versus costs to implement. The model simulated individual practices, physicians, and their panels of patients and incorporated the rate of utilization of primary care and costs and revenues over the course of a year. Analyses were done in R, version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). We used repeated Monte Carlo sampling with replacement from the distributions of utilization, cost, and revenue per physician to compute the median revenue and interquartile range (IQR) for each service in 10 000 simulated practices (Supplement, available at Annals.org).

In addition to panel size, insurer composition, and number of visits made to primary care, key parameters in the model included service eligibility, service provision, and billing rates plus payment amount. For most preventive services, each eligible patient receives the service only once a year. For services like smoking cessation, obesity, and alcohol counseling, we assumed service provision each primary care visit or about twice yearly (18). For services that may displace an existing office visit (that is, transitional care management and cognitive assessment with care planning services), we estimated the incremental revenue from billing the more remunerative service in lieu of a traditional office visit of moderate complexity. For chronic care management and behavioral health integration, which require substantial work by non-PCP personnel, we incorporated these additional costs to estimate profit as revenue minus these non-PCP costs (19, 20). Finally, because survey data may not adequately capture all of the individual components (Supplement Tables 7 and 8, available at Annals.org) required to bill some codes (that is, wellness visits, chronic care management, behavioral health integration, and cognitive assessment with care planning services), we confined our microsimulation estimates to the upper bound in sensitivity analyses.

Role of the Funding Source

The funding source had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study.

Results

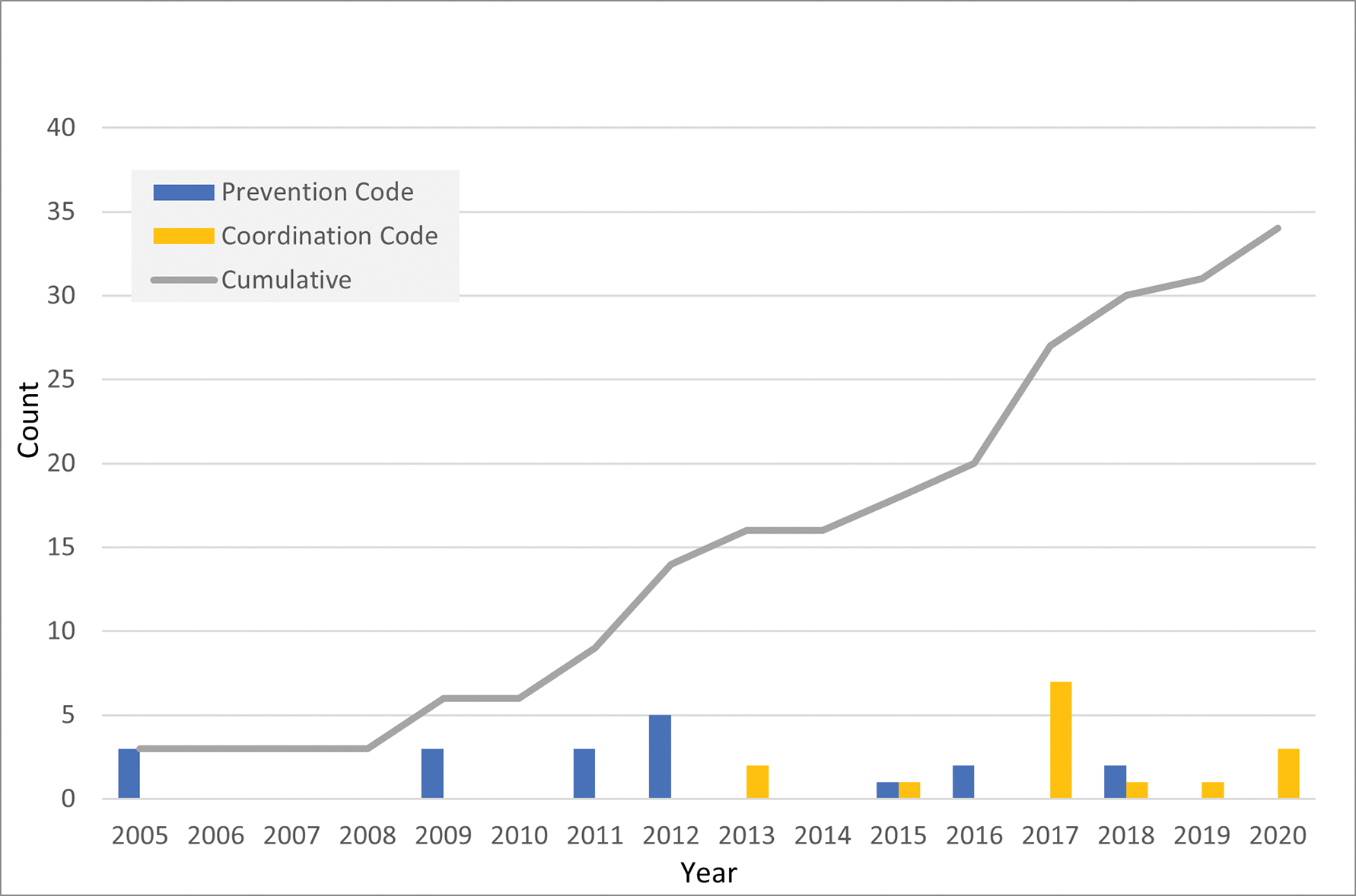

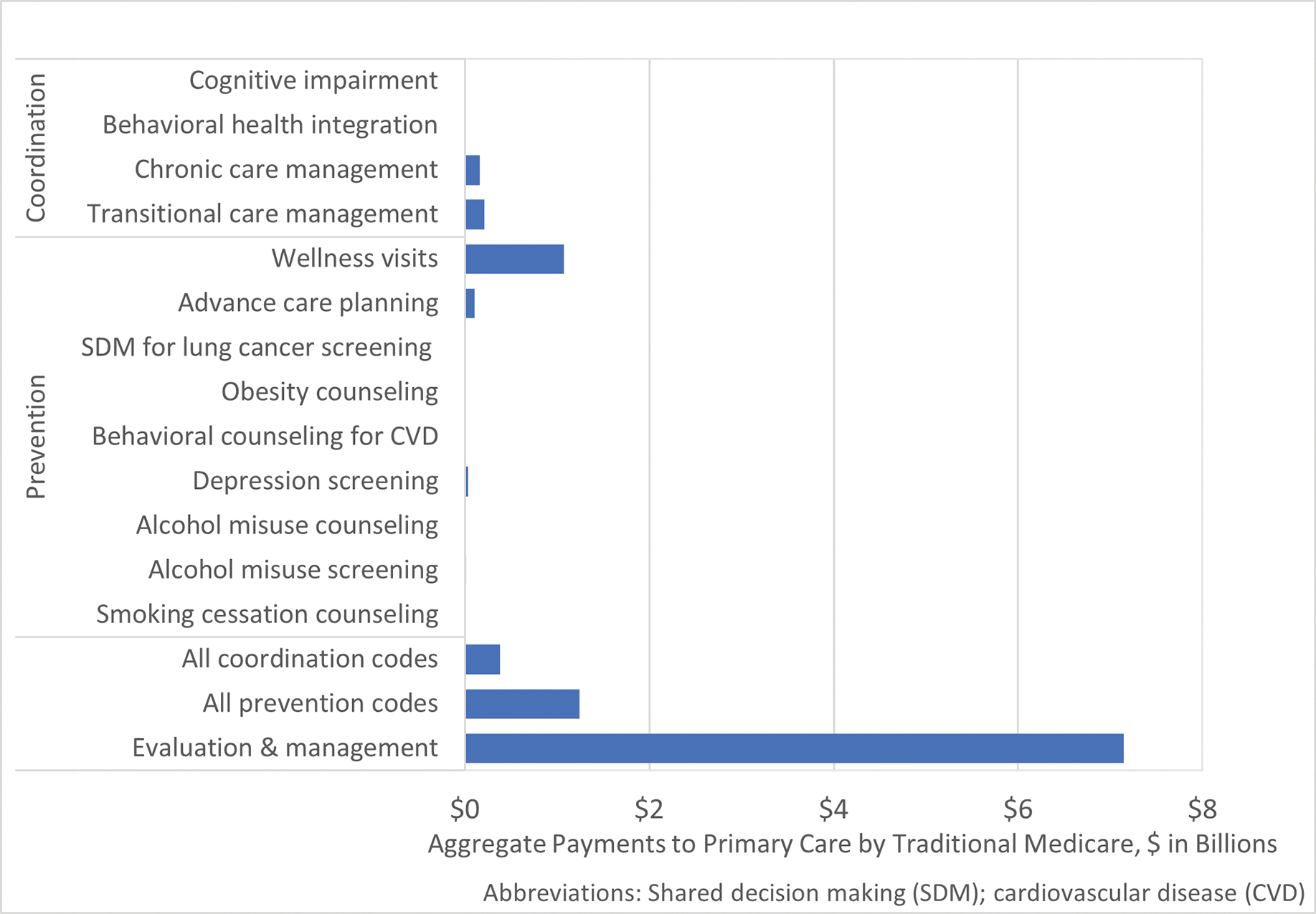

We identified and analyzed 34 distinct prevention and coordination codes, representing 13 distinct categories of services that have been added to the MPFS since 2005 (Figure 1). In 2019, among all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, Medicare paid PCPs about $7.1 billion for evaluation and management services and an additional $1.2 billion for prevention services and $383 million for coordination services (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Number of prevention and coordination codes added to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, 2005 to 2020.

Figure 2.

Aggregate traditional Medicare payments to primary care, 2019. CVD = cardiovascular disease; SDM = shared decision making.

Prevention Codes

Depending on the code, 8.8% to 100% of older adults, or approximately 67 to 762 patients per individual PCP panel, were eligible for specific preventive services, and physicians already provided services represented by those codes to 5.0% to 60.6% of eligible patients annually. However, a much smaller fraction of eligible patients was billed for having received the service, ranging from less than 1% for alcohol misuse counseling or obesity counseling to 35.8% for wellness visits, with most below 10% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Payment Amounts, Eligibility, Current Use of Code, and Receipt of Service as Input Data Used for Revenue Estimates*

| Code | Medicare Payment in 2020 for Code, $ † | Service Eligibility (Eligible for Code, Percentage of Medicare Beneficiaries), % | Among Medicare Beneficiaries Eligible for Service/Code |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billing Rate (Current Use of Billing Code, Percentage of Eligible), % | Service Provision (Received Service Regardless of Billing for Service, Percentage of Eligible), %‡ | |||

|

| ||||

| Prevention codes | ||||

| Smoking cessation counseling | 15.52–29.59 | 8.8 | 10.1 | 60.6 |

| Alcohol misuse screening | 18.41 | 100 | 2.9 | 57.4 |

| Alcohol misuse counseling | 26.71 | 16.0 | <1 | 25.9 |

| Depression screening | 18.41 | 100 | 7.9 | 27.1 |

| Behavioral counseling for cardiovascular disease | 26.71 | 74.0 | 1.4 | 46.7 |

| Obesity counseling | 26.71 | 34.6 | <1 | 51.9 |

| Shared decision making for lung cancer screening | 29.95 | 9.3 | 1.5 | 5.0 |

| Advance care planning | 76.15–86.98 | 100 | 3.7 | 22 |

| Wellness visit | 117.29–172.87 | 100 | 35.8 | – |

| Coordination codes | ||||

| Transitional care management | 187.67–247.94 | 22.5 | 9.3 | 43.3 |

| Chronic care management | 37.89–92.39 | 65.8 | 2.3 | – |

| Behavioral health integration | 48.00–156.99 | 30.2 | <1 | – |

| Cognitive assessment with care planning services | 265.26 | 10.5 | 1.5 | – |

See Supplement Methods and Supplement Table 4 (available at Annals.org) for further details and sources.

For some categories of prevention and coordination services, the full range of payment amounts are shown if there are multiple codes representing initial versus subsequent service delivery, different time requirements, or complexity. See Supplement Table 4 for an itemized list of payment codes.

There is no estimate available for receipt of some services. In particular, the codes for wellness visits, chronic care management, behavioral health integration, and cognitive assessment with care planning services require a suite of services that are not routinely provided.

For instance, the prevalence of smoking among older adults was 8.8%. Among these smokers, 60.6% reported receiving advice to quit from a health care provider, but only 10.1% of the 8.8% had a claim for smoking cessation counseling. Given the number of Medicare patients on a PCP’s panel who are eligible smokers (8.8%) and who received smoking cessation counseling (60.6% of the 8.8%, or 5.3% of all Medicare patients on a PCP’s panel) but accounting for those who were billed (10.1% of the 8.8%, or 0.9%), along with a payment level of $15.52 for brief counseling, PCPs on average did not collect $638 (IQR, $134 to $1143) in annual revenue, or $0.38 when spread across all of a PCP’s Medicare patient visits in a year (that is, per Medicare patient visit) (Table 2). For other preventive services already being provided but not billed, PCPs did not collect between $90 (IQR, $19 to $162) to $14 726 (IQR, $3081 to $26 370) in annual revenue, or $0.05 (IQR, $0.01 to $0.10) to $8.48 (IQR, $1.84 to $15.73) per Medicare patient visit. In total, PCPs were providing preventive services that amount to $40 187 (IQR, $12 474 to $42 903) in uncollected revenue among 8 types of preventive services, or $25 461 (IQR, $9393 to $16 533) without advance care planning.

Table 2.

Potential Revenue per PCP FTE and per Medicare Patient Visit

| Code | Median Annual Revenue for Services for Already Provided but Not Billed (Lower Bound), $ (25th–75th Percentile) | Median Annual Revenue for Services If Provided to Half of All Eligible Patients (Upper Bound), $ (25th–75th Percentile) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Per PCP FTE | Per Medicare Patient Visit | Per PCP FTE | Per Medicare Patient Visit | |

|

| ||||

| Prevention codes | ||||

| Smoking cessation counseling | 638 (134–1143) | 0.38 (0.08–0.68) | 1699 (119–3280) | 1.01 (0.07–1.96) |

| Alcohol misuse screening | 9282 (1942–16 622) | 5.54 (1.16–9.91) | 8269 (1730–14 808) | 4.93 (1.03–8.83) |

| Alcohol misuse counseling | 891 (484–1834) | 0.69 (0.29–1.09) | 4190 (1572–10 620) | 3.64 (0.94–6.33) |

| Depression screening | 3270 (684–5856) | 1.95 (0.41–3.49) | 7843 (1641–14 045) | 4.68 (0.98–8.38) |

| Behavioral counseling for cardiovascular disease | 7429 (4034–15 292) | 5.76 (2.41–9.12) | 7954 (4319–16 373) | 6.17 (2.58–9.76) |

| Obesity counseling | 3860 (2096–5625) | 2.30 (1.25–3.35) | 9060 (3400–14 720) | 5.40 (2.03–8.78) |

| Shared decision making for lung cancer screening | 90 (19–162) | 0.05 (0.01–0.10) | 1269 (266–2273) | 0.76 (0.16–1.36) |

| Advance care planning | 14 726 (3081–26 370) | 8.48 (1.84–15.73) | 38 745 (8107–69 384) | 23.11 (4.83–41.38) |

| Wellness visit* | – | – | 45 406 (9501–81 312) | 27.08 (5.67–48.49) |

| Total | 40 187 (12 474–42 903) | 25.46 (7.44–43.48) | 124 435 (30 654–226 813) | 76.78 (18.28–135.27) |

| Excluding wellness visits | 40 187 (12 474–42 903) | 25.46 (7.44–43.48) | 79 029 (21 153–145 502) | 49.70 (12.62–86.78) |

| Coordination codes | ||||

| Transitional care management† | 9293 (1944–16 642) | 5.54 (1.16–9.92) | 12 395 (2594–22 197) | 7.39 (1.55–13.24) |

| Chronic care management*‡ | – | – | 45 556 (9532–81 579) | 27.17 (5.68–48.65) |

| Behavioral health integration*‡ | – | – | 15 239 (3189–27 290) | 9.09 (1.90–16.28) |

| Cognitive assessment with care planning services*† | – | – | 12 891 (2697–23 085) | 7.69 (1.61–13.77) |

| Total | 9293 (1944–16 642) | 5.54 (1.16–9.92) | 86 082 (18 011–154 152) | 51.34 (10.74–91.94) |

| All codes | ||||

| Total for prevention and coordination codes | 49 480 (14 418–89 544) | 31.00 (8.60–53.40) | 210 517 (48 665–380 965) | 128.11 (29.02–227.21) |

FTE = full-time equivalent; PCP = primary care physician.

Estimate for the indicated codes are confined to the upper bound (50% of the eligible) because the codes for wellness visits, chronic care management, behavioral health integration, and cognitive assessment with care planning services require a suite of services that are not routinely provided.

Because these codes may displace an existing office visit, estimates are incremental—i.e., additional revenue on top of an evaluation and management visit of moderate complexity.

For chronic care management and behavioral health integration, which require substantial work by non-PCP personnel, these represent profit as revenue minus the costs of the non-PCP personnel.

As an upper bound, if a PCP provided the preventive services to half of all eligible patients, a physician could increase revenues of $1269 to $45 406 per code, or $0.76 (IQR, $0.16 to $1.36) to $27.08 (IQR, $5.67 to $48.49) per Medicare patient visit. For example, if half of the 76% of Medicare beneficiaries with 1 or more cardiovascular risk factors received behavioral counseling, a PCP could bring in an additional $7954 (IQR, $4319 to $16 373) in revenue, or $6.17 (IQR, $2.58 to $9.76) per Medicare patient visit. If a PCP provided all preventive services to half of all eligible patients, the PCP could collect $79 029 (IQR, $21 153 to $145 502) exclusive of the annual wellness visits, or $124 435 (IQR, $30 654 to $226 813) inclusive of wellness visits.

Coordination Codes

About 22.5% of Medicare beneficiaries had a hospitalization eligible for transitional care management services. Among these beneficiaries, 43.3% were seen in primary care after discharge, and only 9.3% had a claim for transitional care management (Table 1). If the postdischarge visits that were already provided to patients had also included a postdischarge telephone call and been billed as a transitional care management visit instead of an office visit of moderate complexity, a PCP could earn $9293 (IQR, $1944 to $16 642) more in revenue, or $5.54 (IQR, $1.16 to $9.92) per Medicare patient visit (Table 2). If half of all eligible patients were seen after discharge, a typical PCP could earn an additional $12 395 (IQR, $2594 to $22 197) more in revenue, or $7.39 (IQR, $1.55 to $13.24) per Medicare patient visit.

Two thirds of Medicare beneficiaries were eligible for chronic care management services, about one third of Medicare beneficiaries were eligible for behavioral health integration services, and 10.5% of Medicare beneficiaries were eligible for cognitive assessment with care planning services (Table 1). Less than 3% of eligible patients had a claim for any of these services. Because each requires a suite of services that were not routinely provided to patients, we confined our estimates to the upper bound. If half of all eligible patients were enrolled and billed monthly for chronic care management, a practice could, as an upper bound, receive $45 556 (IQR, $9532 to $81 579) in the annual revenue per full-time physician after accounting for the costs of delivering these services using a registered nurse, or $27.17 (IQR, $5.68 to $48.65) per Medicare patient visit. Similarly, if half of all eligible patients were enrolled and billed monthly for behavioral health integration using the collaborative care model, a practice could, as an upper bound, receive $15 239 (IQR, $3189 to $27 290) in annual revenue per full-time physician after accounting for the costs of the integrated behaviorist to deliver this care, or $9.09 (IQR, $1.90 to $16.28) per Medicare patient visit. Finally, if cognitive assessment with care planning services were provided and billed among half of all eligible patients with cognitive impairment, in lieu of an office visit of moderate complexity, a PCP could receive up to an additional $12 891 (IQR, $2697 to $23 085) in revenue per year, or $7.69 (IQR, $1.61 to $13.77) per Medicare patient visit.

If a PCP provided and billed for all coordination services in half of all eligible patients, the PCP could receive, as an upper bound, $86 082 (IQR, $18 011 to $154 152) in additional revenue per year.

Discussion

In our analysis of prevention and coordination codes that have been added to the MPFS, we found large gaps between how often PCPs could bill for the services among eligible patients and how often PCPs actually billed the corresponding codes. Counseling for obesity, smoking, and cardiovascular disease, for example, seemed to occur much more frequently per survey data than billing claims would suggest. In total, each PCP provided preventive services worth up to $40 187 in additional revenue, which is approximately 16% of an average PCP’s annual salary (21). If a PCP provided and billed either the preventive or coordination services to half of all of their eligible patients, he or she could receive about $80 000 more in revenue. However, depending on the code and when expressed at the individual patient visit level, that would involve $0.76 (IQR, $0.16 to $1.36) to $27.17 (IQR $5.68 to $48.65) of additional revenue per Medicare patient visit.

We relied on national surveys to determine the rate at which patients received certain services, and there are strengths and limitations to our approach. Surveys, for example, do not capture the amount of time physicians spent providing a particular service, nor do they ask about each specific billing requirement. The mapping from a billing code to survey question is thus inexact. However, our results suggest that having to navigate the eligibility, documentation, time, and component requirements of numerous separate codes may be too high of a hurdle to warrant the effort from PCPs to use those codes (22–24). The billing requirements can be detailed and require review of 500 or more page updates to the Medicare payment rules published annually in the Federal Register. The codes for smoking cessation counseling, for example, must be attached to specific International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision diagnoses to qualify for payment or they are otherwise denied. In fact, more than a third of claims for smoking cessation counseling were denied in 2019 (data not shown). The issue of complexity is particularly relevant for most of the codes we analyzed whose payment is only a fraction of that from evaluation and management codes, the workhorse of primary care.

There may be other reasons that physicians forego a substantial amount of revenue for services they could or may already be providing. Even if knowledge and understanding of the codes were perfect, physicians and practice managers may be reluctant or unable to make the upfront financial investment required to operationalize some of the codes, find certain requirements overly prescriptive and potentially unnecessary or inappropriate, be averse to nickel-and-diming patients or find patients unreceptive to the additional bill because several of these codes are subject to the usual 20% Part B coinsurance, and/or be concerned that they are not spending the specific time suggestions for these codes (25). Adhering to the time requirements could in fact displace the delivery of other necessary services, with one study estimating that it would take more than 8 hours of a physician’s time per day to provide all of the services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (26). Although uncollected revenue was potentially large in aggregate, the revenue gains from each of the individual prevention and coordination codes considered on its own would likely be too low or insufficient to cover the additional compliance, billing, and opportunity costs of using them for each individual patient (27).

Importantly, all of these prevention and coordination codes involve decomposing the comprehensive care of a patient into component parts, each with multiple steps and checklists, which may be inconsistent with how PCPs practice and document care (28). The physician–patient interaction is multidimensional, and an office visit is likely more fluid and nuanced than these codes may imply. Furthermore, an office visit is a relatively small unit of care compared with a hospitalization or procedure, so deconstructing an office visit or charging a la carte for the intermittent work between visits is unlikely to be seen as a productive use of time, and in fact may be counterproductive to the provision of whole-person care. Unlike hospitals, primary care practices are typically unable to use departments of trained coders to maximize billing and assure that documentation matches the requirements specified in billing rules (29).

Several studies have described the increased quantity of work within primary care visits as well as the increasing quantity of “unrecognized” and “uncompensated” work between visits (6–8). Primary care providers are providing more preventive services and addressing more diagnoses and medications per visit (18, 30, 31). Unreimbursed work between visits—calling patients or caregivers, returning patient messages, writing letters, reviewing test results or consult reports, interfacing with specialists, refilling prescriptions, coordinating staff, and filling out forms—constitutes a substantial and growing part of primary care (32–39). As a result, there are frequent calls for payment reform. Our study highlights that, in fact, the MPFS has undergone many changes during the past 2 decades, with the addition of numerous codes to better remunerate PCPs for prevention services provided during visits and coordination services provided between visits. The use of the codes by PCPs, however, remains exceedingly low. Only 1 code (for wellness visits) was used for more than 20% of eligible beneficiaries. Although some studies have examined the use of single codes, ours is the first, to our knowledge, to examine a broader collection of prevention and coordination codes and quantify in dollars foregone revenue.

Primary care spending is only 2.1% to 8.0% of total health care spending across states and payors (10, 40, 41) and is declining—even though a substantial body of evidence suggests that systems oriented toward primary care have higher quality, lower costs, and more equity (42). In hopes of investing additional resources in primary care, CMS has had the following 3 general approaches: increasing evaluation and management fees, introducing new codes that provide additional compensation for specific services that occur either within the context of a visit or outside of a visit, and paying a monthly non–visit-based care management fee. Our results suggest that the second strategy—introducing new codes to capture more aspects of primary care—has not been successful. Ultimately, the breadth and depth of primary care may be more than what one-off codes can capture, and the requirements to bill for these myriad codes may discourage their use. Alternative strategies that could better and more flexibly cover all of the varied activities in primary care include time-based billing and partial or global capitation (43–45).

There are limitations to our study. First, we focused our analysis on the Medicare segment of PCPs’ panels, and therefore to the extent that other payers also reimburse for similar preventive or coordination services, our estimates are conservative. Similarly, because some service codes (for example, remote monitoring) were recently introduced, we could not include these in our estimates. Second, national surveys are an imperfect measure of service receipt, especially if measured against the detailed billing requirements of the codes, and there may be some response bias. Nonetheless, for each code, the differences between claims-based use of the codes and survey-based service provision (the final 2 columns in Table 1) are large. Cutting service provision by half or more maintains a persistent and important gap between services provided in primary care and billing for those services. Finally, some codes (for example, wellness visits and chronic care management) require a detailed collection of services to be eligible for billing. To the extent that PCPs deliver parts but not all components of the code, for example discussing cancer screenings but not assessing cognition or fall risk within the same visit, our totals from services rendered may be underestimates.

In conclusion, the use of billing codes remains low across nearly all prevention and coordination codes. The discrepancies between service eligibility, provision of services regardless of billing, and actual billing suggest that attempting to codify each distinct activity done by a PCP in the MPFS may not be an effective strategy for supporting primary care.

Supplementary Material

Grant Support:

By the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (grant P01 AG032952 to Dr. Landon).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging.

Disclosures: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M21–4770.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol: Not applicable. Computer code: Microsimulation code not available (proprietary); for calculating aggregate payments to primary care, available on request by contacting Dr. Agarwal (sagarwal14@bwh.harvard.edu). Data set: Medicare Physician/Supplier Procedure Summary file is publicly available from the CMS.gov website. Medicare claims data are not available due to restrictions on data sharing from CMS.

Contributor Information

Sumit D. Agarwal, Division of General Internal Medicine and Primary Care, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Sanjay Basu, Waymark, San Francisco, California.

Bruce E. Landon, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, and Division of General Medicine and Primary Care, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- 1.Starfield B Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994;344:1129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton R, Berenson RA, Zuckerman S. Medicare’s evolving approach to paying for primary care. Urban Institute. December 2017. Accessed at www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/95196/2001631_medicares_evolving_approach_to_paying_for_primary_care_0.pdf on 1 June 2021.

- 3.Bindman AB, Blum JD, Kronick R. Medicare’s transitional care payment—a step toward the medical home. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:692–4. [PMID: 23425161] doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1214122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards ST, Landon BE. Medicare’s chronic care management payment—payment reform for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2049–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1410790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao JM, Navathe AS, Press MJ. Medicare’s approach to paying for services that promote coordinated care. JAMA. 2019;321:147–148. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodenheimer T Coordinating care: a major (unreimbursed) task of primary care [Editorial]. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:730–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Burriss TC, et al. Providing primary care in the United States: the work no one sees. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1420–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agarwal SD, Pabo E, Rozenblum R, et al. Professional dissonance and burnout in primary care: a qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:395–401. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koller CF, Khullar D. Primary care spending rate—a lever for encouraging investment in primary care. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1709–1711. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1709538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabbarpour Y, Greiner A, Jetty A, et al. Investing in primary care: a state-level analysis. Accessed at www.pcpcc.org/resource/investing-primary-care-state-level-analysis on 1 June 2021.

- 11.Dewar S, Bynum J, Batsis JA. Uptake of obesity intensive behavioral treatment codes in Medicare beneficiaries, 2012–2015 [Letter]. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:368–370. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05437-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal SD, Barnett ML, Souza J, et al. Adoption of Medicare’s transitional care management and chronic care management codes in primary care. JAMA. 2018;320:2596–2597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.16116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basu S, Landon BE, Song Z, et al. Implications of workforce and financing changes for primary care practice utilization, revenue, and cost: a generalizable mathematical model for practice management. Med Care. 2015;53:125–32. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basu S, Phillips RS, Phillips R, et al. Primary care practice finances in the United States amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:1605–1614. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medicare Learning Network. Medicare preventive services (MLN006559). Accessed at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prevention/PrevntionGenInfo/medicare-preventive-services/MPS-QuickReferenceChart-1.html on 8 July 2021.

- 16.Medical Group Management Association. MGMA DataDive overview. Accessed at www.mgma.com/data/landing-pages/mgma-datadive-overview on 20 August 2021.

- 17.Kenexa IBM. CompAnalyst Market Data. IBM; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao A, Shi Z, Ray KN, et al. National trends in primary care visit use and practice capabilities, 2008–2015. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17:538–544. doi: 10.1370/afm.2474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basu S, Landon BE, Williams JW Jr, et al. Behavioral health integration into primary care: a microsimulation of financial implications for practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:1330–1341. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4177-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basu S, Phillips RS, Bitton A, et al. Medicare chronic care management payments and financial returns to primary care practices: a modeling study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:580–8. doi: 10.7326/M14-2677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsiang WR, Gross CP, Maroongroge S, et al. Trends in compensation for primary care and specialist physicians after implementation of the affordable care act. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011981. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn A, Gottlieb JD, Shapiro A, et al. A denial a day keeps the doctor away. National Bureau of Economic Research (Working Paper Series Report No. 29010). July 2021. Accessed at www.nber.org/papers/w29010 on 5 August 2021.

- 23.Landon BE. Tipping the scale - the norms hypothesis and primary care physician behavior. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:810–811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1510923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo Z, Gritz M, Connelly L, et al. A survey of primary care practices on their use of the intensive behavioral therapy for obese Medicare patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2700–2708. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06596-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladin K, Bronzi OC, Gazarian PK, et al. Understanding the use of Medicare procedure codes for advance care planning: a national qualitative study. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41:112–119. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Privett N, Guerrier S. Estimation of the time needed to deliver the 2020 USPSTF preventive care recommendations in primary care. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:145–149. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tseng P, Kaplan RS, Richman BD, et al. Administrative costs associated with physician billing and insurance-related activities at an academic health care system. JAMA. 2018;319:691–697. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stange KC, Ferrer RL. The paradox of primary care [Editorial]. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:293–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmgren AJ, Cutler D, Mehrotra A. The increasing role of physician practices as bill collectors: destined for failure. JAMA. 2021;326:695–696. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flocke SA, Frank SH, Wenger DA. Addressing multiple problems in the family practice office visit. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbo ED, Zhang Q, Zelder M, et al. The increasing number of clinical items addressed during the time of adult primary care visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:2058–65. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0805-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginsburg PB. Payment and the future of primary care [Editorial]. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:233–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murden RA. Payment and the future of primary care [Letter]. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baron RJ. What’s keeping us so busy in primary care? A snapshot from one practice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1632–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMon0910793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen MA, Hollenberg JP, Michelen W, et al. Patient care outside of office visits: a primary care physician time study. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:58–63. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1494-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottschalk A, Flocke SA. Time spent in face-to-face patient care and work outside the examination room. Ann Fam Med. 2005. Nov-Dec;3:488–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farber J, Siu A, Bloom P. How much time do physicians spend providing care outside of office visits? Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:693–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doerr E, Galpin K, Jones-Taylor C, et al. Between-visit workload in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1289–92. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1470-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnett ML, Bitton A, Souza J, et al. Trends in outpatient care for Medicare beneficiaries and implications for primary care, 2000 to 2019. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1658–1665. doi: 10.7326/M21-1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reid R, Damberg C, Friedberg MW. Primary care spending in the fee-for-service Medicare population. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:977–980. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin S, Phillips RL Jr, Petterson S, et al. Primary care spending in the United States, 2002–2016. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1019–1020. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care. National Academies Pr; 2021. Accessed at www.nap.edu/catalog/25983/implementing-high-quality-primary-care-rebuilding-the-foundation-of-health on 26 August 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berenson RA, Rich EC. US approaches to physician payment: the deconstruction of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:613–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1295-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Basu S, Song Z, Phillips RS, et al. Implications of changes in Medicare payment and documentation for primary care spending and time use. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:836–839. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05857-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selby K, Edwards S. Time-based billing: what primary care in the United States can learn from Switzerland. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:881–2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.